Abstract

In imitation learning between humans and robots, the embodiment gap is a key challenge. By focusing on a specific body part and compensating for the rest according to the robot’s size, the embodiment gap can be overcome. In this paper, we analyze dynamic attention to body parts in imitation learning between humans and robots based on a Transformer model. To adapt human imitation movements to a robot, we solved forward and inverse kinematics using the Levenberg–Marquardt method and performed feature extraction using the k-means method to make the data suitable for Transformer input. The imitation learning process is carried out using the Transformer. UMAP is employed to visualize the attention layer within the Transformer. As a result, this system enabled imitation of movements while focusing on multiple body parts between humans and robots with an embodiment gap, revealing the transitions of body parts receiving attention and their relationships in the robot’s acquired imitation movements.

1. Introduction

Based on the analysis [1], Japan’s working-age population has decreased by approximately , from a peak of about 87 million in 1995 to about 74 million by 2024. Across OECD countries, the working-age population is projected to decline by about between 2023 and 2060. These demographic shifts lead to chronic labor shortages, driving the demand for automation technologies, including robotics, as a means to alleviate labor shortages.

However, this process requires detailed, task-specific control, which is labor-intensive. Imitation learning offers a promising solution, allowing robots to learn tasks by observing and replicating demonstrated actions. However, the embodiment gap [2] between humans and robots complicates this process. Embodiment refers to physical characteristics such as link configuration, sensor placement, and center of gravity. To imitate humans, robots must understand human actions and intentions, then translate them into actions within the robot’s embodiment constraints.

Imitation learning can be classified into three levels:

- 1.

- Movement-level imitation: This involves directly imitating movements, such as replicating the motions of hands or feet.

- 2.

- Result-level imitation: This focuses on replicating the outcomes of actions, such as moving an object or opening a door.

- 3.

- Intention-level imitation: This involves understanding and imitating the goal behind an action, for example, understanding the goal of cleaning to achieve the result of picking up trash and then using a broom to sweep.

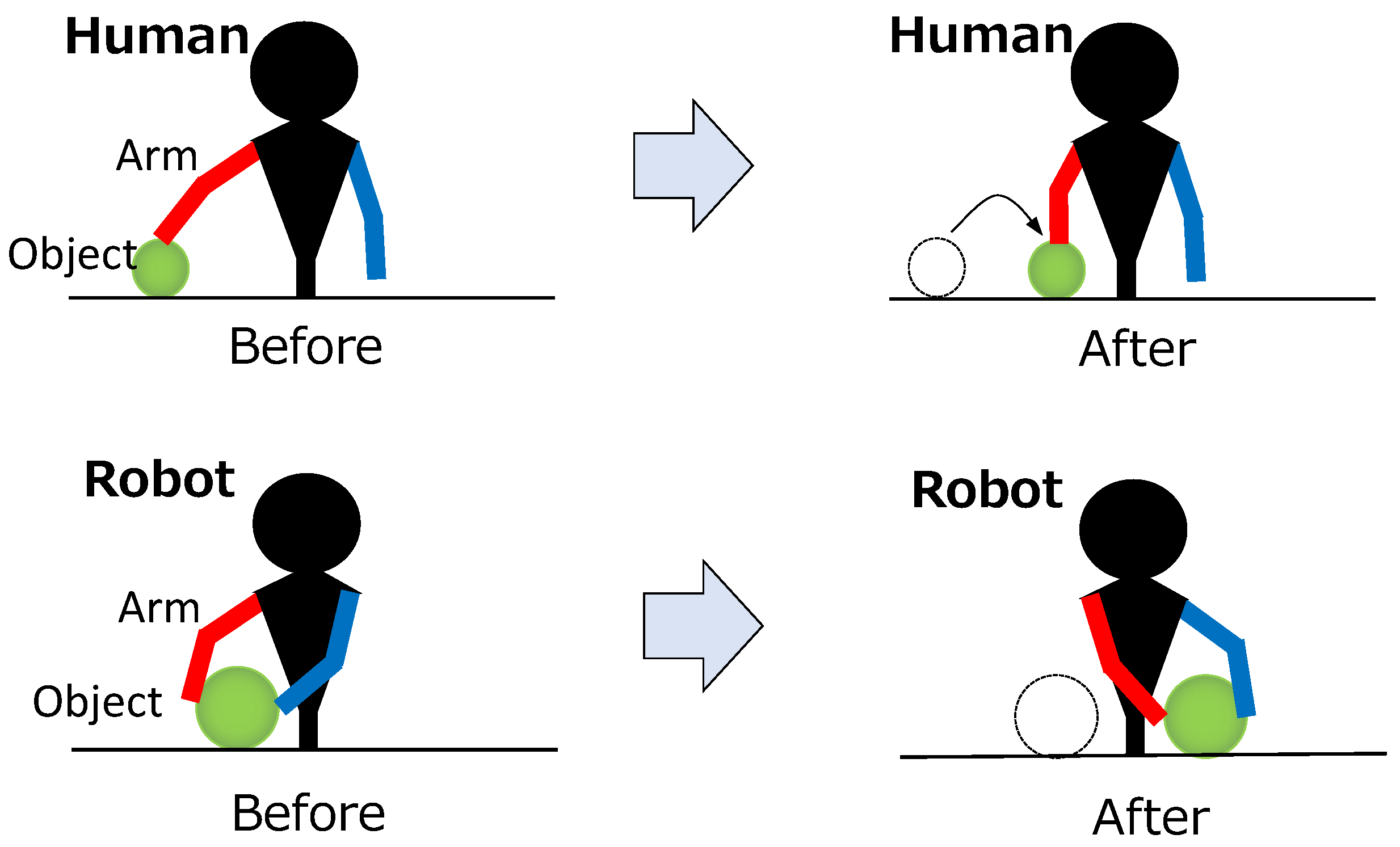

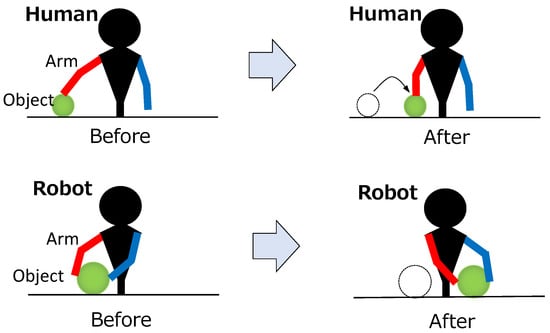

To show an image of the embodiment gap, Figure 1 (top) shows an image of a human task and Figure 1 (bottom) shows an image of a robot imitating the task according to the embodiment. When the robot performs pick and place of an object with one hand, as in Figure 1 (top), if the robot’s embodiment is similar to that of a human, it is sufficient to reproduce it by movement-level imitation. However, if it has the embodiment gap, it is necessary to switch to result-level imitation, as in Figure 1 (bottom), where pick and place is performed with both hands. Furthermore, if the intention to move the object is understood, it is ideal to switch to intention-level imitation.

Figure 1.

Image of embodiment gap. This figure is divided into two parts: (Top) Example of human work demonstration. (Bottom) Example of robot imitation of work.

In this work, we focus specifically on movement-level imitation learning. While task-level success such as accurate end-effector positioning is essential, focusing solely on the final task outcome often overlooks embodiment differences between humans and robots. Since robots typically have different kinematic structures from humans, they cannot directly reproduce human joint configurations or motion trajectories. Therefore, learning motion patterns rather than only task outcomes is crucial for imitation learning with embodiment gaps. Movement-level imitation enables robots to reconstruct human actions in a manner adapted to their own embodiment, thereby serving as a fundamental prerequisite for task execution. In this sense, reliable result-level performance can only be achieved once movement-level behavior that respects embodiment differences is properly acquired.

The embodiment gap causes challenges in both the creation of teaching data and the learning and inference processes for robots. Mapping human states to robots is difficult due to this gap. Previous research addressed it using kinematics teaching [3,4] or teleoperation [5,6], but these methods require expert skills and become harder as the robot’s degrees of freedom increase. To tackle this, our previous work [7] focused on either the end-effector position or joint angles, allowing the robot to interpolate the rest, reducing the embodiment gap.

Differences in dynamics and control also pose challenges during learning and inference. It is essential to learn a policy compatible with the robot’s embodiment. Previous studies employed deep reinforcement learning [8] and inverse reinforcement learning [9] to adapt imitation techniques. In our previous research [7], we used an Energy-Based Model (EBM) [10] for Implicit Behavior Cloning (IBC) [11], enabling evaluation of the embodiment gap between humans and robots while learning separated imitation action policies. These policies focus on either the end-effector position or joint angles. However, to achieve more natural movements, it is necessary to focus on and transition between multiple body parts rather than just a single part.

In this paper, we analyze how the Transformer dynamically allocates attention across body parts in imitation learning between humans and robots. By visualizing and quantifying attention transitions, we clarify how attention mechanisms relate to motion generation and embodiment adaptation. Although previous studies have applied Transformers to imitation learning, none have deeply analyzed the internal attention dynamics contributing to motion generation with embodiment gaps.

First, the system captures human movements using two cameras and creates a simplified human skeleton model using the BODY 25 format of OpenPose [12]. The transitions of joint angles, as well as the position and orientation of the end effectors during human movements, are calculated from this skeleton model. Next, imitation movements are generated, prioritizing the movements of the body parts the human focuses on while compensating for the movements of robot parts with different physical characteristics. This is achieved by solving the inverse and forward kinematics numerically, considering the robot’s link lengths, degrees of freedom, and joint axis configuration. Finally, the policy for realizing the imitation movements is learned using a Transformer model [13].

The Transformer model can dynamically shift attention across different parts of the input data, making it well-suited for imitation learning between humans and robots with different embodiments. During a movement, the focus naturally transitions between body parts. By analyzing attention shifts and joint angle variations, we evaluate the relationship between attention and motion. This approach enables imitation without kinematic teaching or teleoperation, allowing generalization across various robots. However, it currently supports only movement-level imitation and must be extended for tasks requiring result-level imitation. This paper evaluates the effectiveness of Transformer-based imitation learning through attention–motion analysis.

2. Related Works

2.1. Learning from Demonstration Under Embodiment Differences

Several physical and teleoperation-based methods have been proposed to mitigate the embodiment gap during data collection. Kinematic teaching [3,4] directly manipulates robot joints along a desired trajectory, while teleoperation [5,6,14] allows a human to remotely control a robot through visual or immersive feedback.

M. Tykal et al. [4] proposed incrementally assisted kinesthetic teaching, leveraging Virtual Tool Dynamics (VTD) and incremental interaction assistance to improve physical teaching; the method modulates the robot’s assistive dynamics via VTD rather than relying on explicit impedance control. In teleoperation, imitation is achieved by mapping human limb vectors (e.g., shoulder to wrist, hip to toe) to the robot using motion capture [5]. However, due to embodiment differences, direct mapping is rarely feasible, and the human must adjust actions by observing the robot via camera or VR/MR systems [6,14].

Alternative setups employ a teaching robot with a morphology similar to the target robot, allowing the human to demonstrate motions indirectly. Recent interface-based approaches such as LEGATO [15] and Tool-as-Interface [16] learn policies in tool- or object-centric task spaces and then retarget them to the robot via inverse kinematics, effectively decoupling the policy from morphology and enabling cross-embodiment transfer. Unlike teleoperation or morphology-matched teaching robots, LEGATO shares a handheld tool across different robots (thus avoiding robot-specific teaching hardware), and Tool-as-Interface learns from human videos without dedicated teaching devices; however, both typically assume a rigid tool attachment and reliable tool pose estimation at deployment, which can still constrain scalability in practice.

2.2. Transformer-Based Imitation Learning

Transformer-based models are increasingly used in imitation and reinforcement learning for their strength in handling sequential data and long-term dependencies, making them promising for addressing the embodiment gap in human–robot imitation.

Recent approaches include ACT [17], which segments demonstrations into action chunks, and Behavior Transformer [18], which discretizes actions to learn multi-modal behavior. Decision Transformer [19] models reinforcement learning as sequence prediction based on return-to-go, while Q-Transformer [20] tokenizes action dimensions for TD learning. Robotics Transformers 1 and 2 [21,22] integrate large-scale vision–language data for generalization across tasks and robots.

Although Transformer-based imitation learning has been explored, to the best of our knowledge there has been little to no systematic, quantitative analysis of how attention weights relate to the primary driving joints during imitation.

2.3. Cross-Embodiment Imitation Learning

Cross-embodiment imitation learning aims to enable motion transfer between agents with different morphologies and joint configurations. Conventional Behavior Cloning (BC) [23] assumes identical state–action spaces between the demonstrator and the learner, making it unsuitable for heterogeneous embodiments. Recent studies have thus focused on learning embodiment-invariant policies and representations that bridge physical discrepancies between human and robot kinematics.

2.3.1. Inverse Reinforcement Learning and Goal Inference

Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) provides a framework for learning embodiment-invariant goals and rewards from demonstration trajectories. While traditional IRL methods assume identical morphologies, recent works relax this assumption by embedding both agents into shared goal or task spaces. As in the Restraining Bolt [24] and XIRL [25], reward inference occurs in either a logical or visual latent space that abstracts away morphological details. Human2Sim2Robot [26] similarly leverages object- and goal-centric rewards, enabling reinforcement learning without the need for manual correspondence between joints. These IRL-based methods are effective at transferring intent and task-level knowledge between humans and robots with distinct embodiments.

2.3.2. Adversarial and Embedding-Based Methods

Adversarial imitation learning and embedding alignment techniques have also been extended to cross-embodiment imitation. Franzmeyer et al. [9] introduced an adversarial framework that jointly learns a domain-invariant embedding between expert and learner states, reinforced by mutual-information regularization to retain task-relevant information. Liu et al. [27] proposed a decomposed adversarial imitation learning approach for humanoid skills, where digital–human demonstrations are first learned as low-level primitives and later retargeted to robots via partial inverse kinematics and fine-tuning. These methods bridge morphological gaps by aligning feature distributions and learning transferable latent representations that capture functional rather than structural equivalence.

2.3.3. Transformers and Diffusion-Based Models for Generalization

Recent research has leveraged sequence modeling and generative learning frameworks to achieve robust generalization across embodiments. Xu et al. [28] proposed XSkill, which discovers shared skill prototypes from unlabeled human and robot video data and learns conditional diffusion policies for cross-agent imitation. Niu et al. [29] introduced the Modularized Cross-Embodiment Transformer (MXT), a shared Transformer backbone with embodiment-specific tokenizers, enabling skill transfer between humans and robots of different morphologies. Other works employ generative augmentation: EmbodiSwap [30] synthesizes robot-hand overlays in human demonstration videos for zero-shot imitation, while DemoDiffusion [31] uses diffusion models to refine retargeted human trajectories to robot constraints. DexMV [32] reconstructs 3D hand–object poses from human videos and maps them to robot hands via inverse kinematics. By utilizing generative priors and Transformer attention mechanisms, these studies achieve scalable policy transfer and motion generalization across diverse embodiments.

2.3.4. Imitation from Observation (IfO)

Imitation from Observation (IfO) enables agents to imitate behaviors purely from perceptual data, typically visual inputs, without requiring explicit action labels. Conventional IfO methods generally assume identical or similar embodiments between the demonstrator and the learner, where BC-based frameworks [33] can directly estimate actions from visual states. To overcome the limitations of high-dimensional action spaces, methods such as GAIL [34] and its variants have been employed, while estimating joint angles from visual demonstrations improves imitation efficiency [35,36]. Reinforcement learning extensions have further achieved one-shot imitation from a single demonstration [37,38,39].

However, when the embodiments of the demonstrator and the learner differ significantly, direct mapping becomes infeasible. In such cases, additional representation alignment is required, leading to the development of cross-embodiment IfO approaches. For instance, Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) [40] have been used to learn temporal correspondences between human and robot sequences, while Skeletal Feature Compensation [41] learns an affine transformation over skeletal features to compensate for morphology differences, thereby improving imitation under embodiment mismatch. Attention-based imitation using human gaze estimation [42] further demonstrates how perceptual attention can inform embodiment adaptation.

In our previous work [7], we addressed imitation across different embodiments using a humanoid target and a robot with different joint and link configurations. The embodiment gap was estimated using the Levenberg–Marquardt method [43], enabling separation of movements into end-effector and joint-angle-prioritized types, which were then imitated using Implicit Behavioral Cloning [11].

Previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of motion-level imitation across different embodiments; however, they often focused on fixed or limited body parts. In contrast, the present work aims to address how attention mechanisms in a Transformer model can dynamically shift focus among body parts during imitation and how such attention allocation reflects underlying joint motion patterns.

3. Dynamic Attention Mechanisms in Transformer Models for Human–Robot Imitation

3.1. Posture Estimation

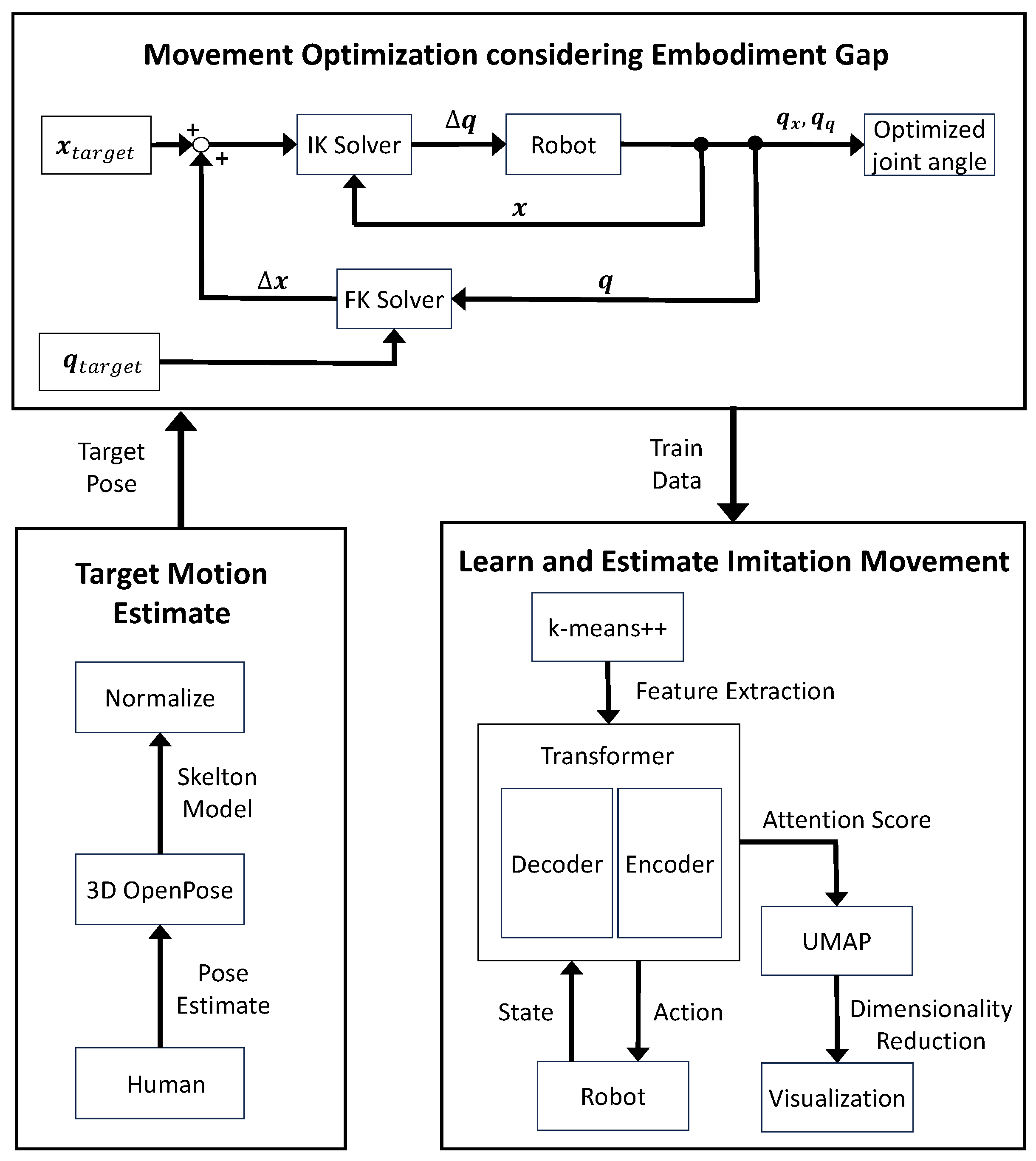

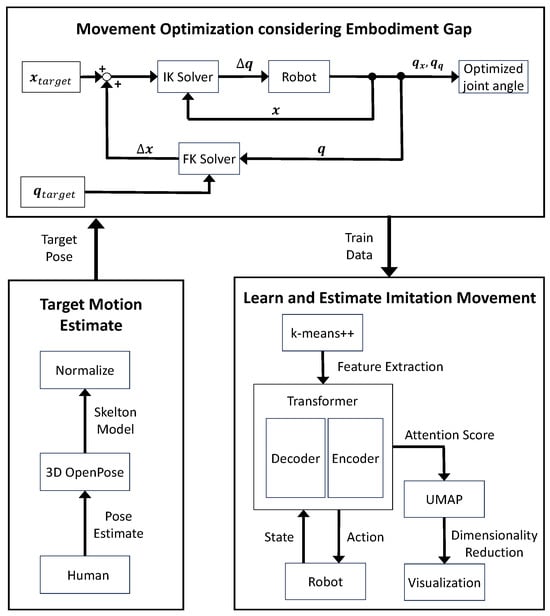

The proposed imitation learning method is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The proposed imitation learning system.

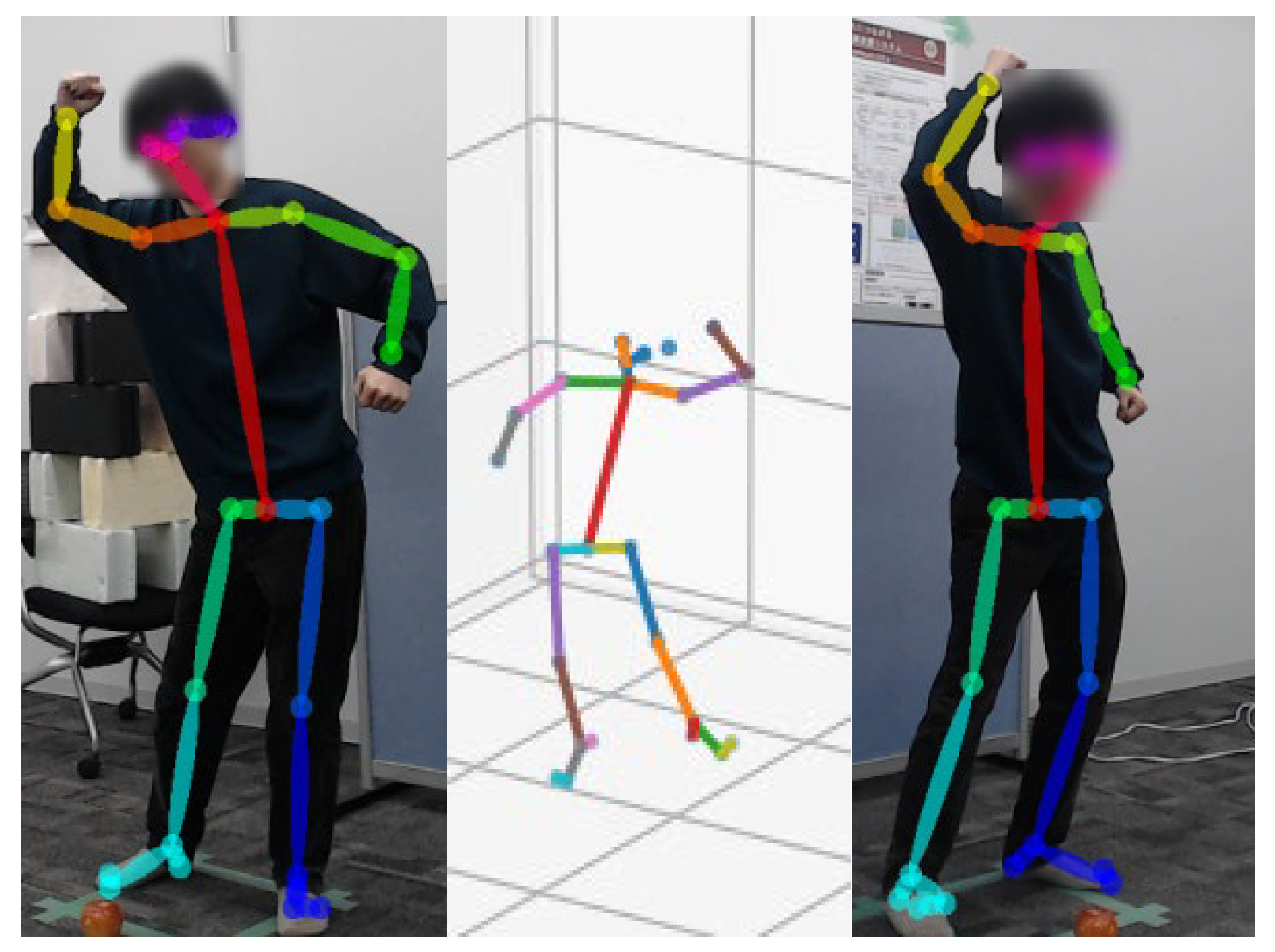

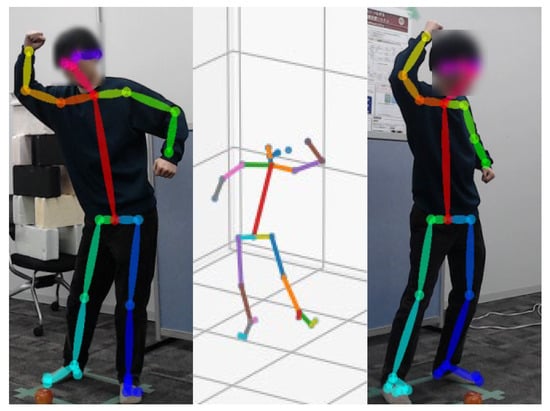

In this study, human motion was captured using two RGB cameras. Human joint positions are represented as a keypoint skeleton, in which joints are connected by straight line segments. The skeleton format adopted in this study is OpenPose BODY25 [12], a standard representation consisting of 25 anatomically meaningful keypoints estimated by OpenPose. OpenPose performs bottom-up pose estimation by predicting joint heatmaps and part affinity fields (PAFs) from RGB images through a convolutional neural network. PAFs represent the spatial associations between detected joints, enabling robust pose estimation even in cases involving multiple persons or partial occlusion. When multiple cameras are employed, the 3D coordinates of each joint can be reconstructed by triangulating the corresponding 2D keypoints obtained from different viewpoints. Figure 3 shows an example of human pose estimation obtained using OpenPose.

Figure 3.

Human skeleton model for 3D OpenPose.

3.2. Estimate Embodiment Gap

In this paper, we classify a robot’s embodiment into two types: predefined elements, such as link and joint configurations, and emergent elements identified through interaction with the environment. The former can be described using formats like URDF, while the latter includes dynamic factors learned from data. To bridge the embodiment gap in imitation learning, initial imitation movements are generated based on predefined features and later refined through execution feedback. Since humans and robots differ in joint structures and degrees of freedom, reproducing both end-effector trajectories and joint angles simultaneously is often infeasible.

Therefore, effective imitation should prioritize the body parts humans emphasize during tasks. For instance, in object grasping, end-effector position is more important than specific joint angles. Adapting joint configurations based on the robot’s embodiment while preserving key task-relevant features enhances imitation success. When robots with an embodiment gap imitate human movements, the body parts they focus on may differ from those of humans. As the robot learns, it optimizes its focus based on its embodiment. Visualizing these focused body parts helps evaluate the impact of embodiment on the movement.

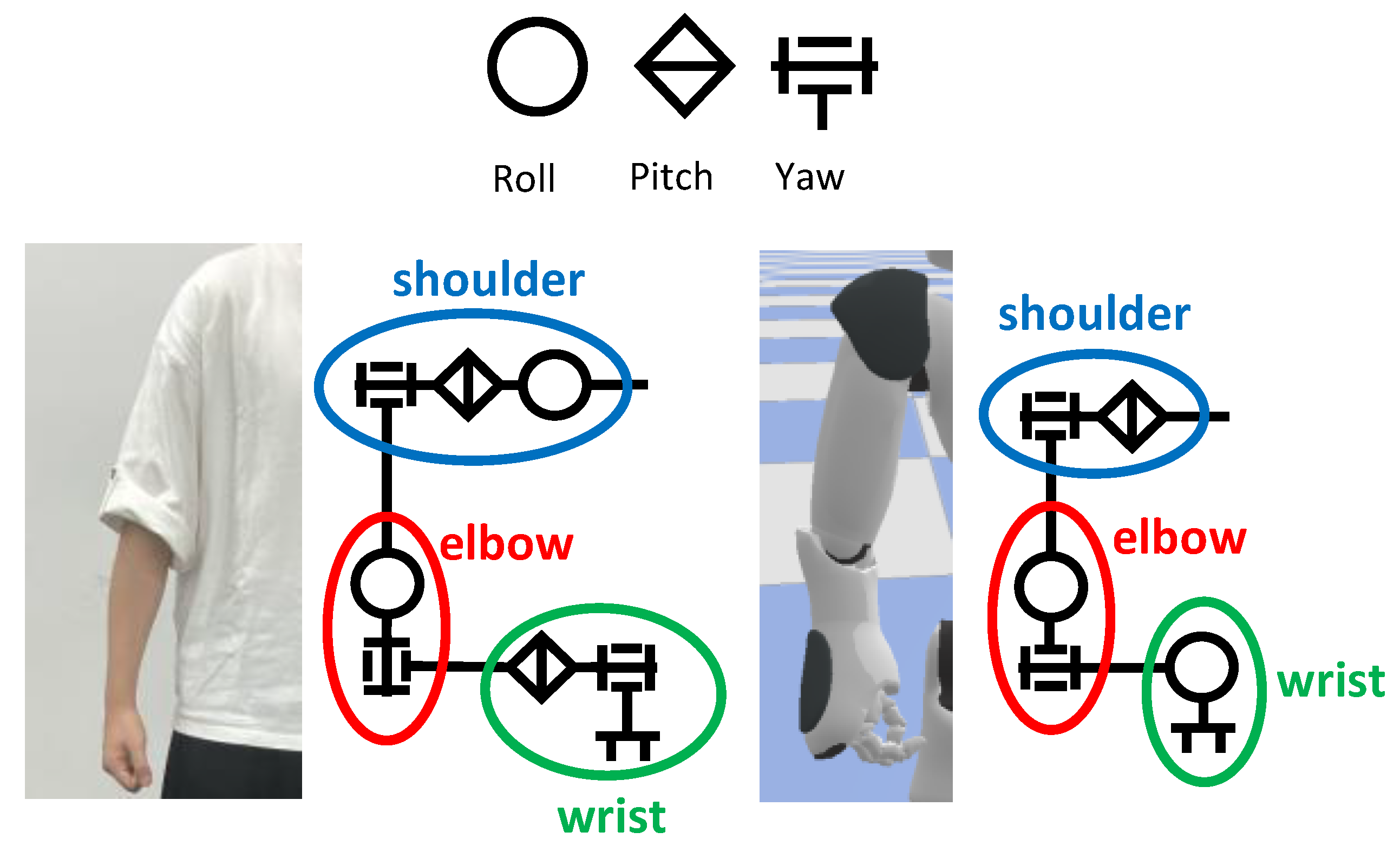

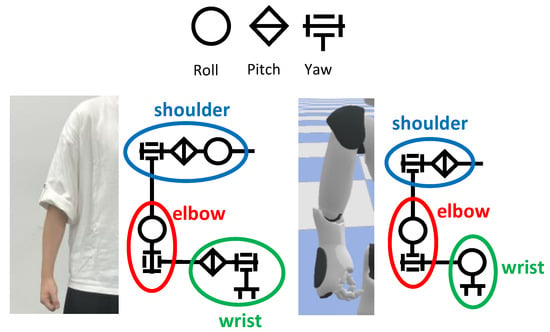

Figure 4 illustrates the differences in kinematic structure between humans and the NAO robot. Furthermore, Table 1 summarizes the approximate differences in joint range of motion [44,45,46], which represent another aspect of the embodiment gap.

Figure 4.

Differences between human and robot body structure.

Table 1.

Comparison of the right arm joint range of motion between humans and NAO.

These embodiment gaps arise not only from joint mobility limitations but also from differences in body segment lengths. To address the scale difference between the target and the robot, the target’s movements are normalized. Unifying the action space is necessary due to the scale differences between humans and robots, requiring length information for each part of both the imitation target and the robot. For humans, the length of each part can be obtained from the skeleton model estimated by OpenPose. For robots, this information can be acquired from the URDF description. The scale constant d is defined by

represents the number of links in the moving body part, and denotes the length of each link. The human scale constant is denoted as , and the robot scale constant is denoted as . Additionally, if the position of the human’s body part endpoint calculated from the estimated skeleton model is denoted as , it is converted into the robot’s action space as follows:

Equation (2) computes , the robot’s target body-part endpoint, by scaling the human endpoint according to the embodiment differences between the human and the robot. This scaled point serves as a reasonable reference position for imitation. Furthermore, is utilized as the target end-effector position in the inverse kinematics optimization, which is solved using the Levenberg–Marquardt method.

The kinematics problem is solved using the Levenberg–Marquardt method, a standard nonlinear least-squares algorithm that has been successfully applied to robot inverse kinematics [43]. We adopt LM because its damping mechanism improves robustness compared to the pure Gauss–Newton method while remaining simpler to implement than more elaborate trust-region approaches.

To account for anthropometric differences between the human demonstrator and the robot, we normalize human motion with respect to link lengths for each kinematic chain. Specifically, we compute a scale constant from the human skeleton model and from the robot URDF and use their ratio in Equation (2) to map the human endpoint position to the corresponding robot point . By applying this scaling, the imitation input becomes largely independent of the demonstrator’s absolute body scale so that residual performance differences mainly reflect embodiment factors such as joint configuration and range of motion rather than arm length.

Next, the joint angles are determined using inverse kinematics, and the end-effector position and orientation are computed using forward kinematics. This process is alternated to achieve imitation of both the end-effector position and orientation as well as the joint angles [7]. Both inverse and forward kinematics are solved by minimizing the objective functions defined using the Levenberg–Marquardt method as follows:

where is the Jacobian matrix, represents the end-effector velocity, represents the joint angular velocity, denotes the difference between the target end-effector position and the current one, and represents the difference between the target joint angles and the current joint angles. The regularization terms with coefficients and are used to minimize displacements in the end-effector position and joint angles, respectively. These terms also help to prevent abrupt motion changes and numerical instability caused by constraints or infeasible configurations resulting from the robot’s embodiment. The update quantities that minimize and are defined by

Following Algorithm 1, the joint angles , which prioritize the reproduction of the target end-effector position , and the joint angles , which prioritize the reproduction of the target joint angles , are obtained.

Here, and represent differential updates, whereas and indicate target errors in task and joint spaces, respectively. and are the update rates for and , respectively, and must be set appropriately for stability. The algorithm first solves inverse kinematics, then uses forward kinematics to update the target end-effector position. By using the Levenberg–Marquardt method for inverse kinematics, discrepancies in target joint angles that may not match the robot’s configuration are adjusted. If there are fewer target joint angles than the robot’s joints, the extra joints are used in the optimization to minimize changes in the end-effector position.

Algorithm 1 based on the Levenberg–Marquardt method was implemented in Python 3.8.

| Algorithm 1 Estimate ,. |

|

3.3. Feature Extraction of Imitation Movement

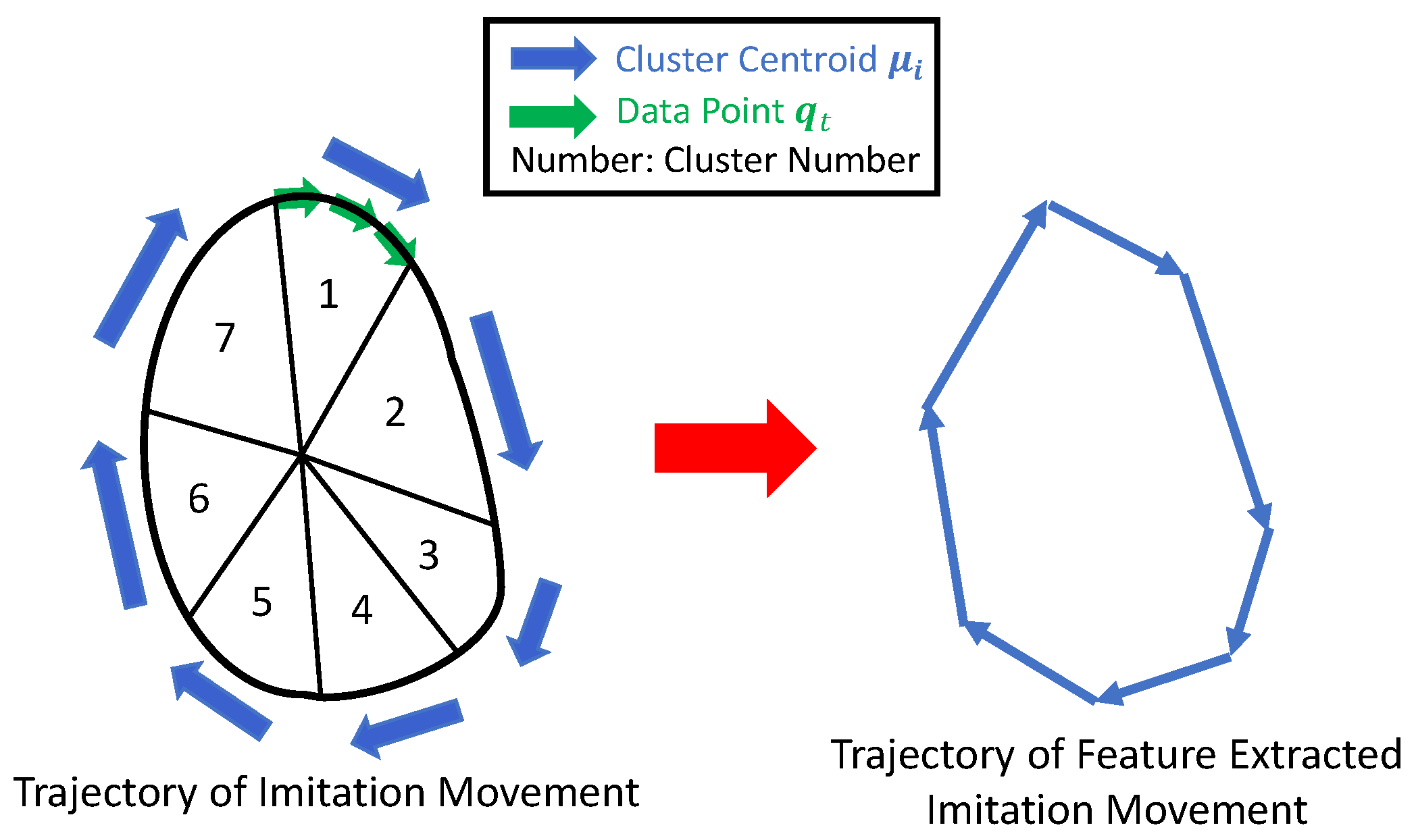

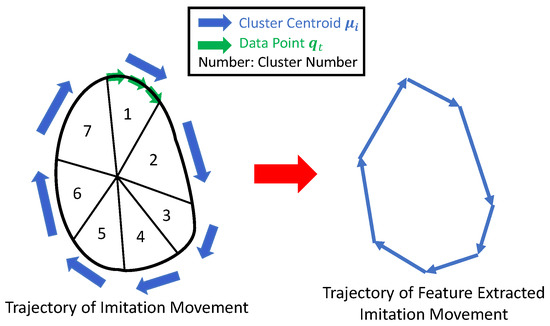

When inputting data into the Transformer, it is challenging to capture unstable continuous data with large variations. Therefore, the features of the unstable data are extracted to make it easier for the Transformer model to recognize the patterns of the movements. Figure 5 illustrates the concept of feature extraction for imitation movements. The imitation movements, estimated based on the embodiment gap, are divided using a clustering method, with each cluster’s center vector used as the representative to extract features. In this study, feature extraction for the imitation movement data is performed using the k-means method [47]. By applying k-means clustering, the structural relationships within the data can be emphasized. It should be noted that the trajectory of the end-effector position is slightly different because of the joint angle input. In this study, we cluster the optimal robot joint angles obtained through imitation kinematics.

Figure 5.

The concept of feature extraction for imitation movements.

The k-means method aims to minimize objective function as follows:

Here, T represents the time step, and N represents the number of clusters. Clustering is performed based on Equation (7), classifying similar vectors into the same cluster. To minimize the objective function in Equation (7), initial values must be selected. If selected randomly, however, the method may become dependent on the initial values. To overcome this, we use the k-means++ method [48]. In k-means++, one center point is randomly selected from the dataset at the beginning. For the remaining center points, the minimal distance from each data point to the previously selected center points is calculated. The probability of each data point being selected as the center point is shown by

After selecting the initial values (center points) and fixing , we minimize with respect to . The closest cluster is selected based on the data point nearest to the t-th data. is determined as shown by

Next, while keeping fixed, we minimize with respect to . Here, is partially differentiated with respect to the l-th center point .

From Equation (10), the updated center point is obtained. This method has the characteristic of classifying similar vectors into the same cluster, making feature extraction, as shown in Figure 5, possible. However, since the input vectors are joint angle vectors, the trajectory of the end effector may be slightly shrunk. The algorithm for the k-means++ method is presented Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 k-means++ method. |

|

This algorithm segments unstable joint angle information and converts it into a form that makes it easier for the Transformer model to capture movement patterns.

Although the impact of k-means++ is difficult to explain theoretically, it helped stabilize Transformer training by reducing redundancy in continuous joint data. Since clustering is a preprocessing step and not a core contribution, we consider experiments unnecessary.

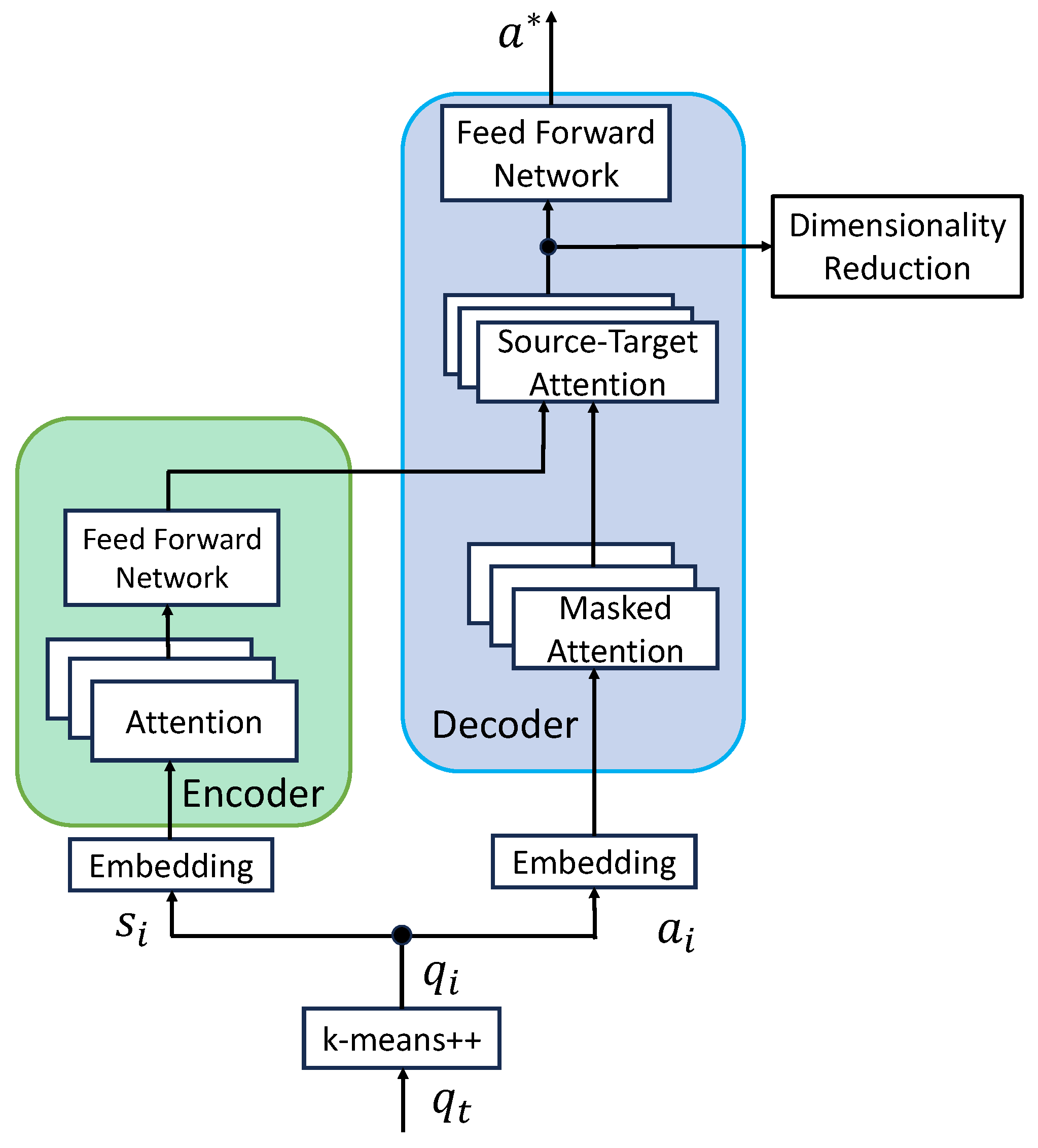

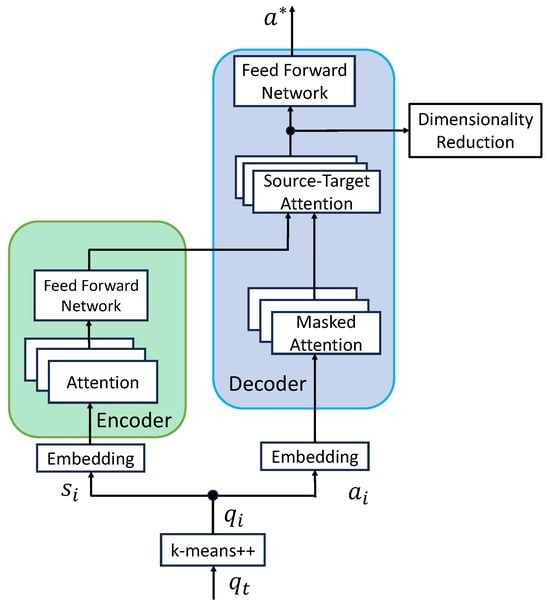

3.4. Learning Imitation Policy and Estimation Action

A key issue with Behavior Cloning, which serves as a baseline in imitation learning, is the averaging of imitation patterns, leading to the loss of diverse movement patterns. In this study, we address this issue by using a Transformer. The Transformer learns each movement sequence individually and captures the overall pattern, enabling the preservation of diverse movement patterns while maintaining consistency within the movement sequences. Figure 6 below shows the Transformer model used for imitation learning.

Figure 6.

Transformer model for imitation learning.

In the Transformer, actions are output based on states . In the Encoder, the structure of the state is captured, and in the Decoder, the next action is predicted using Masked Multi-Head Attention. The Decoder’s Source-Target Attention learns the actions corresponding to the state at each time step. Multi-Head Attention is a function that maps the outputs of query (Q), key (K), and value (V). The output is represented as a weighted sum of the values. Here, in the Encoder, , , and are state vectors, while in the Decoder, they are action vectors. Attention within the Encoder and Decoder is represented as follows:

Here, is the dimensionality of the key in Equation (11). In Equation (12), attention is the process of assigning weights to the values based on the similarity between the Q and K vectors. This allows the structure of the time-series state and action vectors to be captured. Additionally, multiple attention layers exist in parallel.

In Equation (13), is the learnable output projection matrix that maps the concatenated attention outputs from all heads into the final feature space. In Equation (14), the projected parameter matrix is ,, .

The attention score refers to the output of the Multi-Head Attention mechanism calculated using Equation (13).

In Equation (13), Multi-Head Attention shifts focus to different positions from various representation spaces, enabling attention transitions over time-series data. By visualizing attention values, it becomes clear which body parts are prioritized during specific actions over time. This allows for the identification of key body parts in the movements acquired by the robot during human–robot imitation learning, making it possible to evaluate movements affected by the embodiment gap.

Since the action predicted by the Transformer is continuous, the loss function used is the mean squared error function (MSE). This loss function is shown by

In action estimation, the next action is estimated by selecting the one with the highest probability output by the Decoder, as follows:

Although the Transformer outputs a sequence of continuous action vectors, we select the most confident one using a topk(1) operation along the temporal dimension. This enables us to interpret Equation (16) as selecting the highest-scoring action from the sequence rather than computing a maximizer over a continuous probability distribution. The selected vector is treated as the final action .

The predicted action provides the joint angles for each time step, allowing the robot to execute the corresponding motion. This process enables the generation of imitation behaviors.

3.5. Dimensionality Reduction

In this study, we aim to visualize which body parts receive attention in the Transformer model [20]. Since the attention data lies in a high-dimensional space, dimensionality reduction is applied to the output of Source-Target Attention.

Common methods include PCA [49], KPCA [50], t-SNE [51], and UMAP [52]. For interpreting attention, preserving local proximity is essential. PCA and KPCA focus on maximizing variance and preserving global structure, but they may distort local relationships. t-SNE and UMAP better preserve local structures. UMAP, based on Riemannian geometry and algebraic topology, also retains global features like distance and cluster layout [52], making it the preferred method in this study.

UMAP represents high-dimensional data as a graph based on local relationships. For each data point in the output of Source-Target Attention, neighboring points are identified using a local distance function. The proximity between each point and is modeled as the following probability.

Furthermore, since this equation is asymmetric, it is symmetrized.

In Equation (17), the expression represents the degree to which belongs to the neighborhood of . Here, is a scale parameter centered at , and denotes the minimum distance between and any other point . The scale parameter is adaptively determined based on the local data density.

Next, the data is mapped to a lower-dimensional space. The proximity between data points and in the lower-dimensional space is modeled based on the following probability:

In Equation (19), a and b are hyperparameters adjusted based on the shape of the data distribution. This equation represents the strength with which belongs to the neighborhood of . Equation (19) takes a t-distribution-like form to avoid the crowding problem that arises when using the same distribution as in Equation (17), which would hinder proper low-dimensional embedding.

UMAP learns low-dimensional embeddings so that the probability distribution in high-dimensional space and in low-dimensional space match. It does this by minimizing using a cost function C based on cross-entropy.

The cost function in Equation (20) minimizes the difference in proximity of points in high-dimensional and low-dimensional spaces, thus yielding point placement in low dimensions.

UMAP is not used as part of the training or control process but rather as a post hoc visualization tool to interpret the model’s internal representations. By projecting high-dimensional embedding features into a low-dimensional space, UMAP allows us to observe whether similar motions are grouped together and whether attention patterns correspond to meaningful motion structures. This interpretability is particularly valuable for understanding how the model encodes motion in the context of embodiment differences.

4. Experimental Results of Dynamic Attention Mechanism in Transformer Models

4.1. Experiments Setting

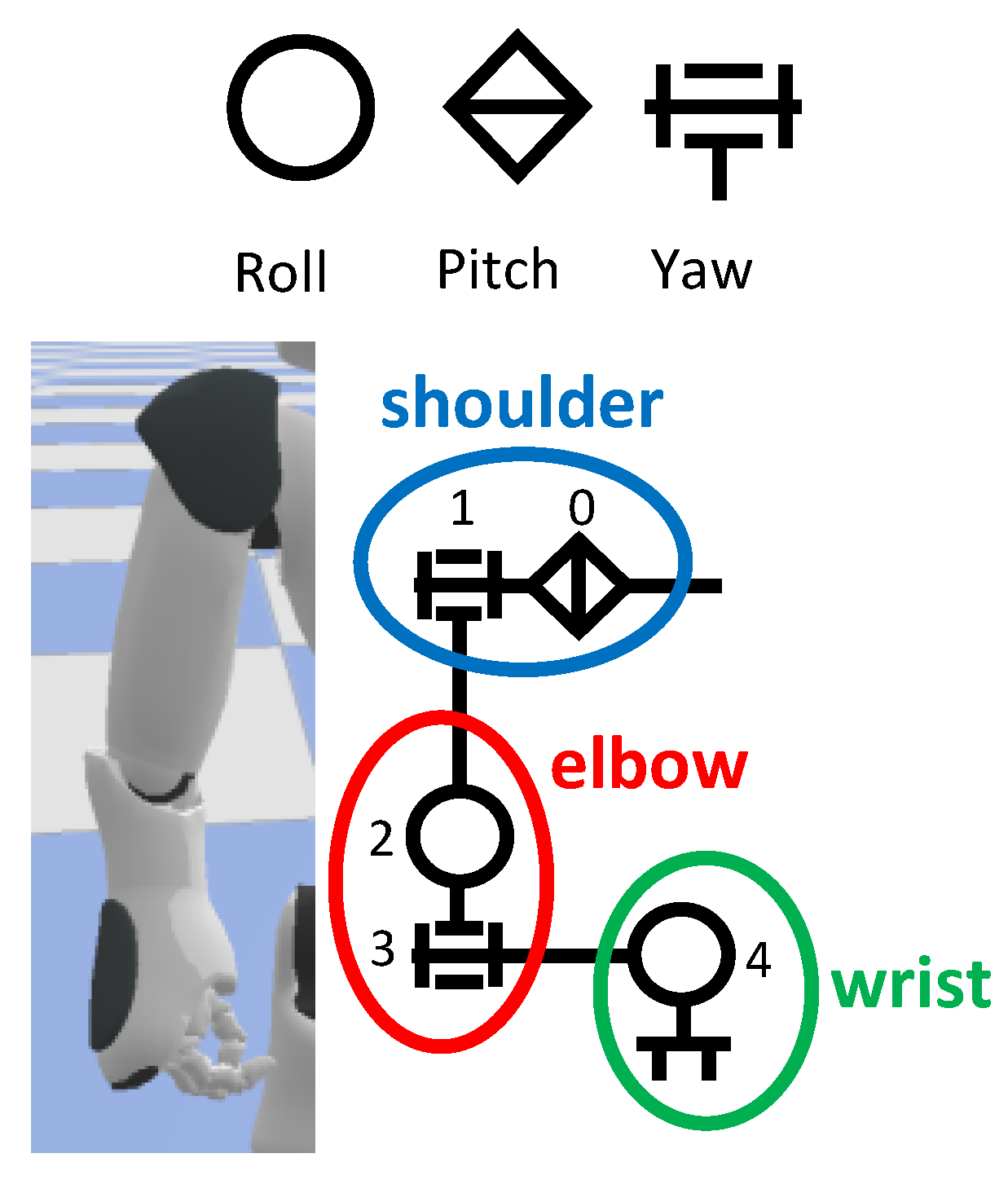

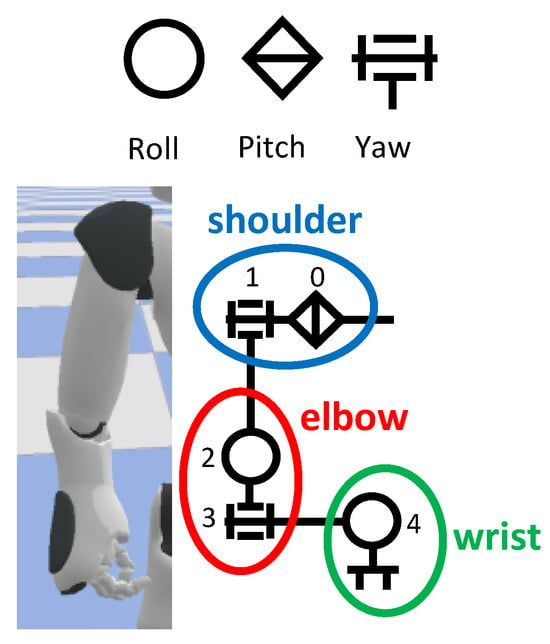

We conducted an experiment to test whether the proposed method could learn the movements of humans and robots with an embodiment gap. The robot used in the experiment is SoftBank’s NAO V6 (SoftBank Robotics, Paris, France), a humanoid robot with a height of 52 cm and a body structure featuring 25 degrees of freedom (DoF). The evaluation of the proposed method is performed by conducting experiments that consider the embodiment gap between humans and the NAO V6. The experiments are conducted using the qiBullet 1.4.6 simulation environment [53] in Python 3.8. The robot’s state and action are defined as follows:

In this study, we limited the analysis to four joints in the right arm to focus on the interpretability of attention mechanisms in cross-embodiment imitation learning. Extending the method to full-body humanoid motion would require advanced whole-body control strategies, which fall outside the scope of this work.

Figure 7 shows the joint numbers of the NAO robot, which correspond to those used in subsequent graphs. We collected 80 samples for each of the three circular movements performed by the human right arm and conducted imitation learning. The robot’s control frequency was set to 10 Hz. The k-means++ algorithm divided the motion data into 10 segments for whole-arm circles, elbow-centered circles, and wrist-centered circles. The Transformer model used four layers, with the following hyperparameters: four heads, a model dimension of 128, a batch size of 32, and a learning rate of . The feed-forward network (FFN) of the Transformer is a three-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP), defined as follows:

Figure 7.

The joint number corresponding to the angular joint.

The notation 512 × 3 indicates that the feed-forward network is composed of three hidden layers, each forming a 512-dimensional feature representation.

In this study, we employ a method where the state is input into the Transformer’s Encoder, and the action is predicted and output by the Decoder. Given the initial state of the NAO robot, predictions are made based on the Transformer model that has learned the actions required to transition to the next state. Through this action , NAO obtains the joint angles to move for each time step and performs the corresponding movements. This enables the realization of imitation.

This study presents three results. First, we compare the end-effector position trajectory from demonstration data with the inferred trajectory to assess if the Transformer model accurately replicates movements. Second, we visualize which parts of the body the model pays attention to during the inferred movement and observe shifts in preferred body parts and transitions of the attention score. Third, we analyze the relationship between joint angles and attention score, evaluating correlations between changes in attention score and joint angle variations in specific body parts.

In this study, the attention score represents the value of the output from the Multi-Head Attention mechanism defined by Equation (13).

Note that the attention scores in this work are distinct from the physical sensitivity captured by the Jacobian . While the Jacobian represents kinematic relationships, attention scores are learned from data and reflect task-relevant joint importance.

4.2. Imitation Learning Results and Analysis of Dynamic Attention to Body Parts

In this study, the imitated movement is drawing a circle with the right arm in three ways: using the entire arm, centering on the elbow, and using the wrist. There is a 1-DOF difference at the shoulder and wrist between the human and the robot. Thus, the robot is expected to focus on different body parts compared to the human. We observe and evaluate these differences during the imitation of the three circular movements.

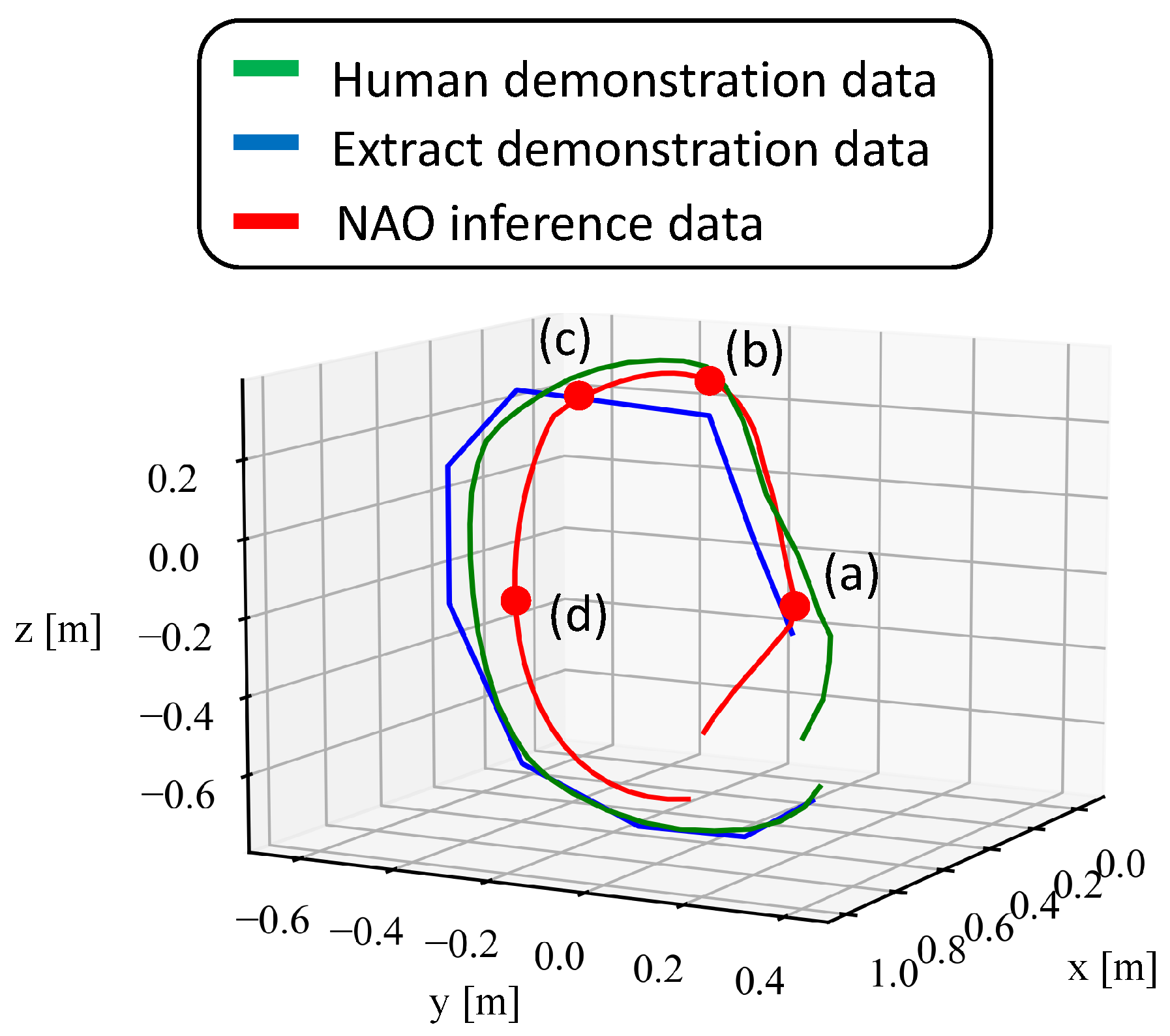

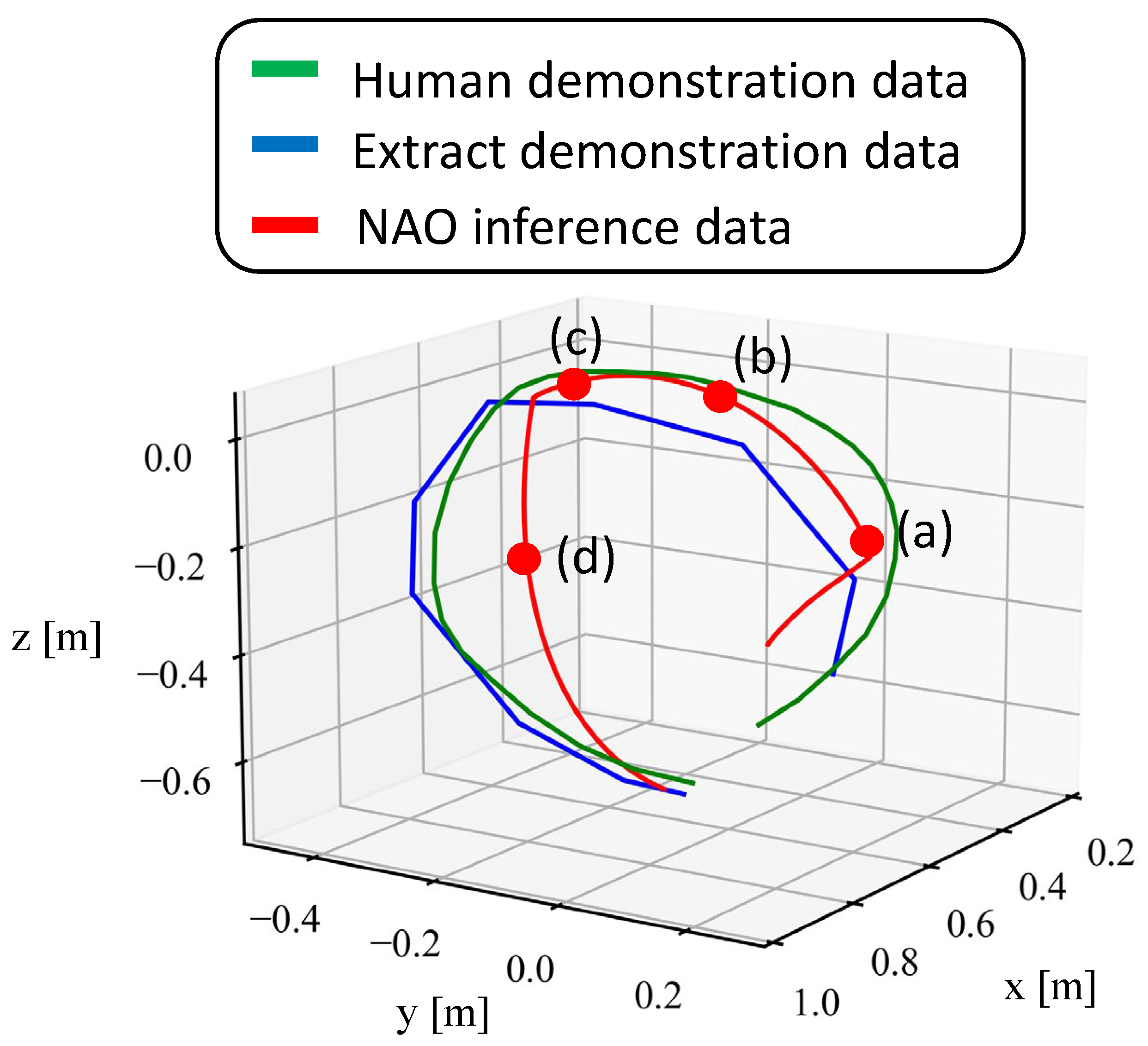

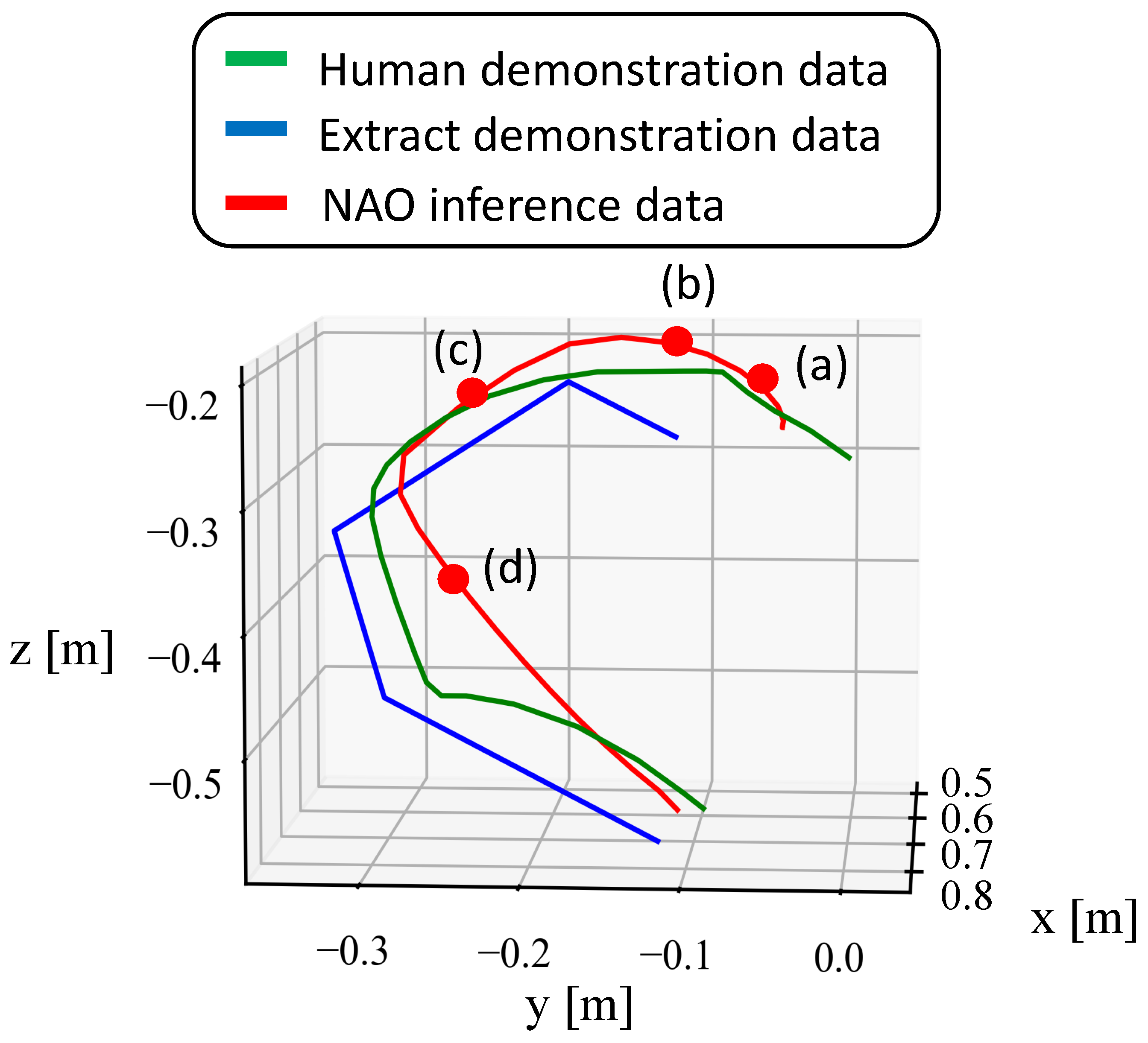

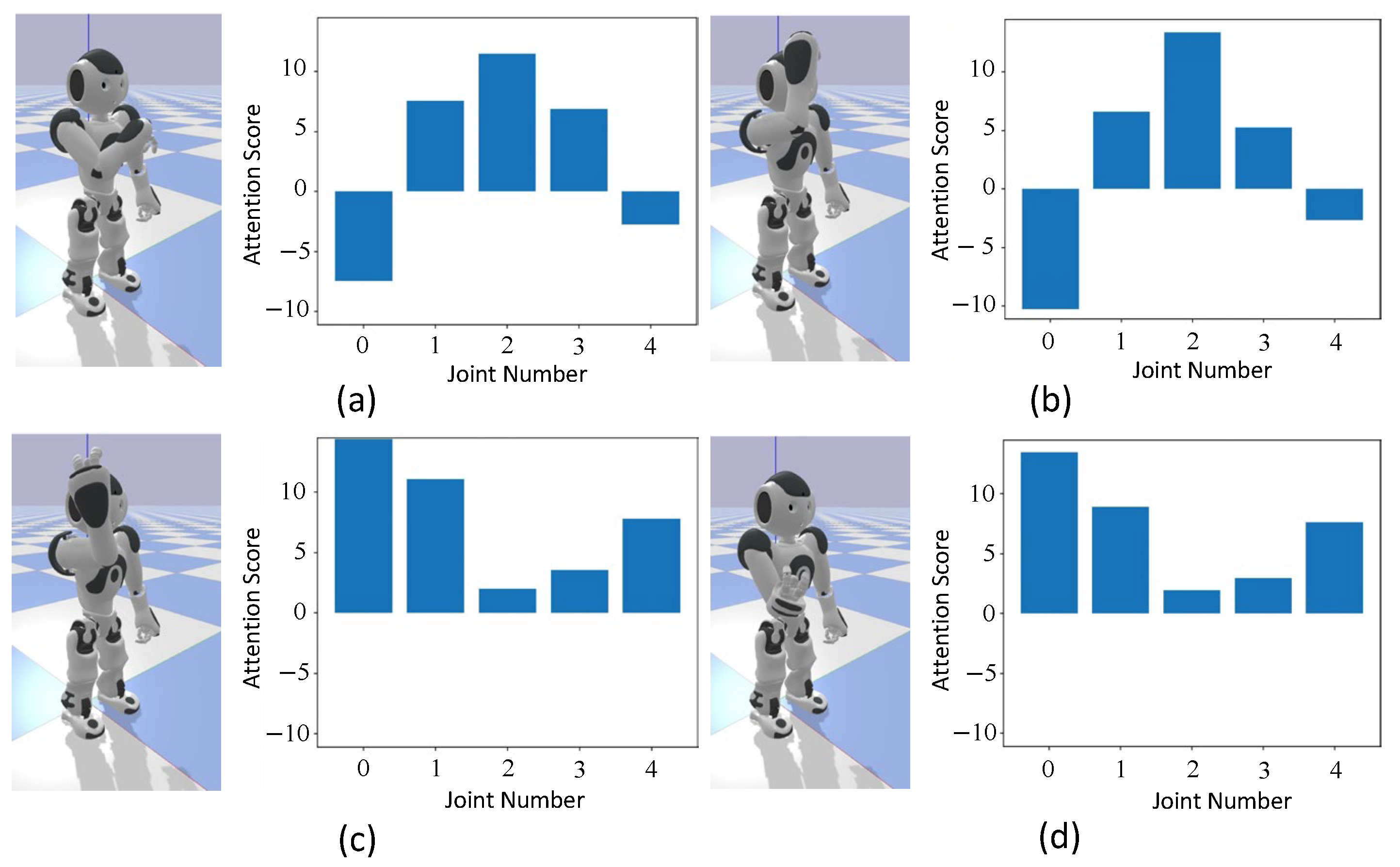

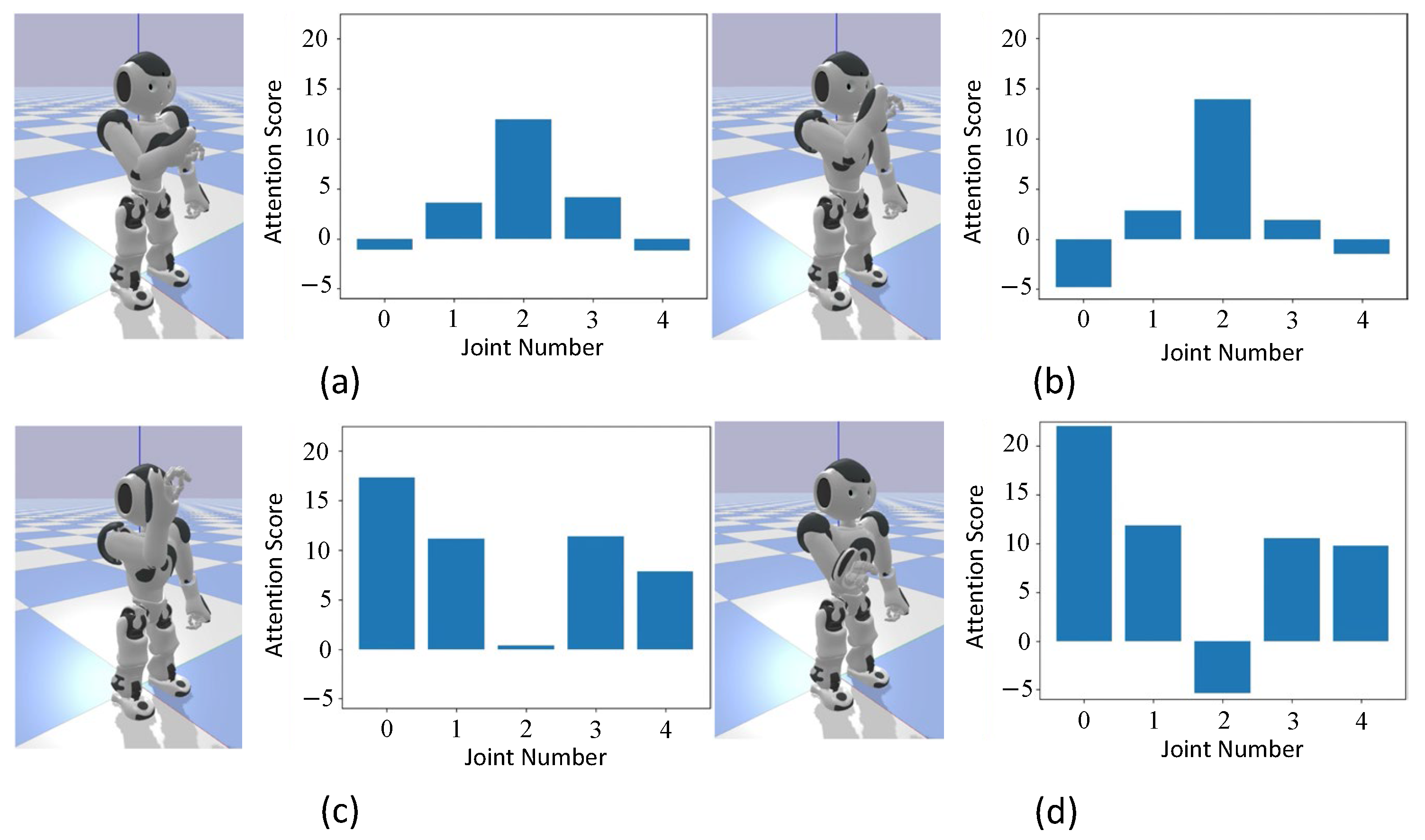

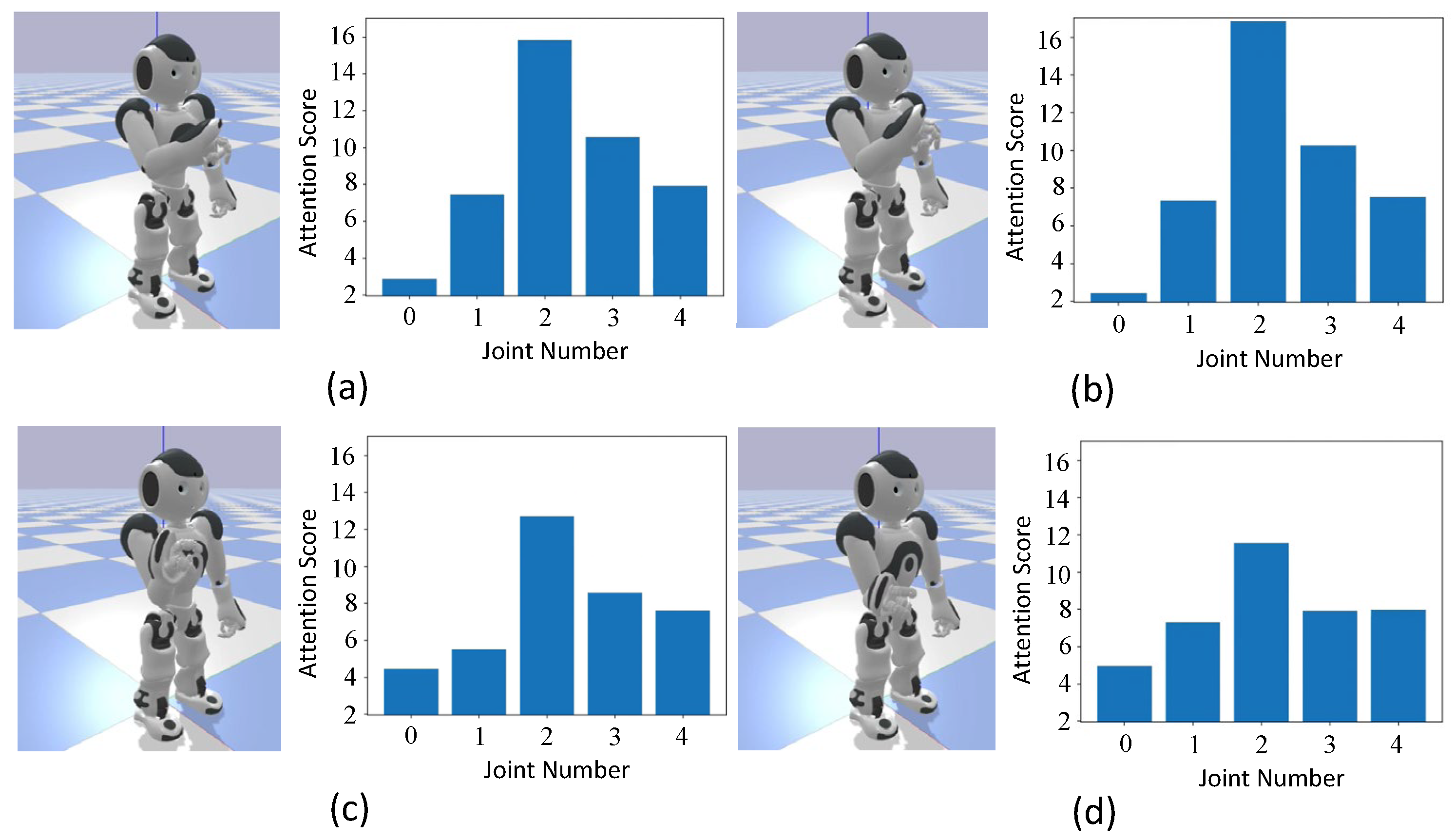

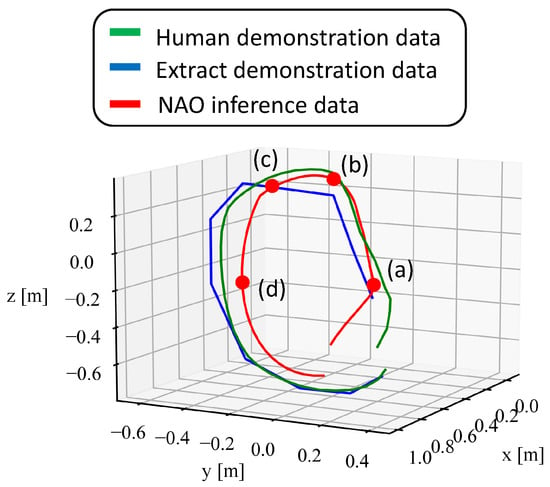

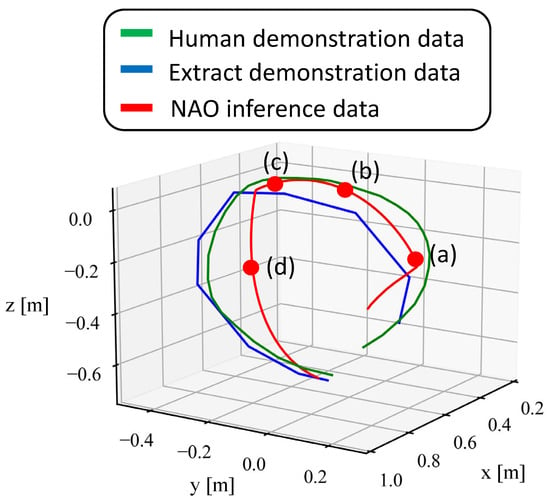

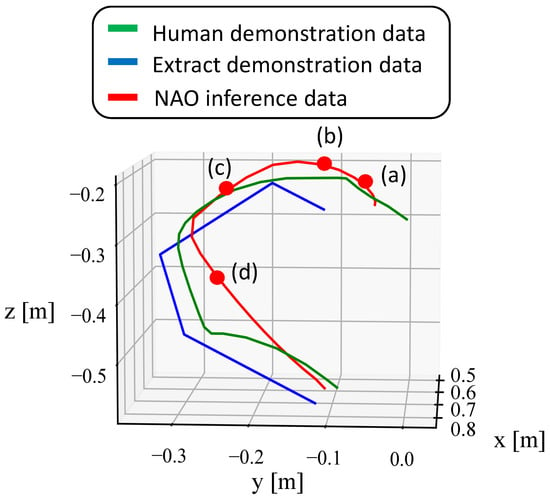

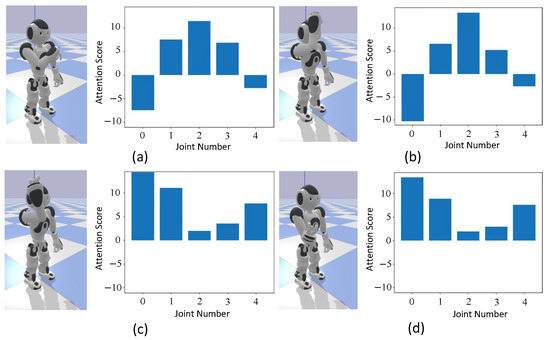

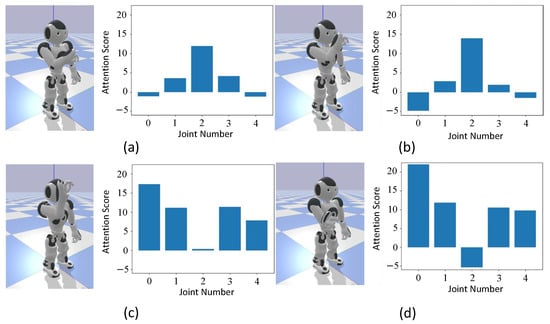

First, we verify the trajectory of the movements acquired through imitation learning. Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the end-effector position trajectories for each type of circular movement. Additionally, we observe which body parts the model focuses on and transitions between during the acquired movements. Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 below show graphs of the body parts receiving attention for each of the three types of circular movements. a, b, c, and d in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 correspond to a, b, c, and d in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 8.

Trajectory of the end-effector position when drawing a circle with the whole arm.

Figure 9.

Trajectory of the end-effector position when drawing a circle focusing on the elbow.

Figure 10.

Trajectory of the end-effector position when drawing a circle focusing on the wrist.

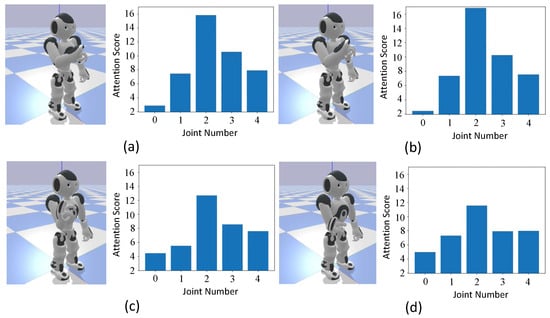

Figure 11.

Attention when drawing a circle with the whole arm. This figure is divided into four parts: (a) The process of raising the arm at 1.0 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (b) The process of drawing a circle while raising the arm at 3.3 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (c) The process of only drawing a circle at 4.3 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (d) The process of lowering the arm at 5.7 s and the corresponding attention at that time.

Figure 12.

Attention when drawing a circle focusing on the elbow. This figure is divided into four parts: (a) The process of bending and rotating the elbow at 9.0 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (b) The process of only rotating the elbow at 3.2 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (c) The process of beginning to lower the arm at 4.5 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (d) The process of lowering the arm at 6.8 s and the corresponding attention at that time.

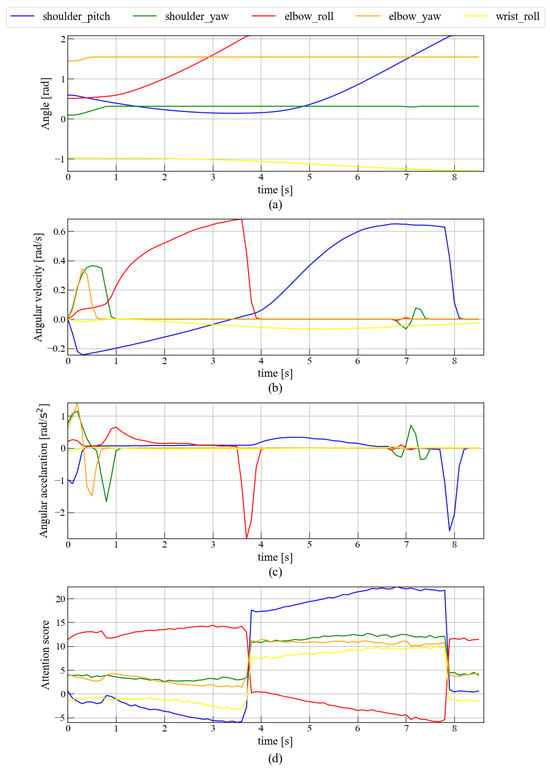

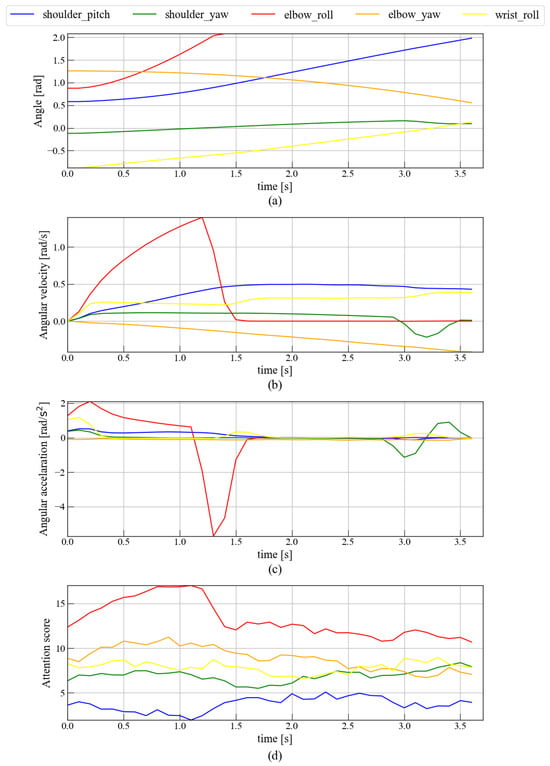

Figure 13.

Attention when drawing a circle focusing on the wrist. This figure is divided into four parts: (a) The process of raising the arm using the elbow at 7.0 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (b) The process of rotating the elbow at 1.1 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (c) The process of lowering the arm using the elbow at 1.8 s and the corresponding attention at that time. (d) The process of moving the arm horizontally to the left at 2.7 s and the corresponding attention at that time.

Figure 8 shows the end-effector trajectory when drawing a circle with the entire arm, while Figure 11 shows the robot’s movement and attention in Figure 8. Figure 9 shows the end-effector trajectory when focusing on the elbow, and Figure 12 shows the corresponding movement and attention in Figure 9. Finally, Figure 10 shows the end-effector trajectory when focusing on the wrist, with Figure 13 showing the corresponding movement and attention in Figure 10.

As shown in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, the green trajectory represents the human demonstration data obtained by estimating the embodiment gap, the blue trajectory shows the end-effector position of the feature-extracted demonstration data using k-means++, and the red trajectory indicates the position acquired by the NAO through imitation learning. The learned movements closely follow the trajectory of the blue demonstration data, but the robot’s movement speed is consistently slower, likely due to the simulation’s control software.

In Figure 11a,b and Figure 12a,b, which correspond to the arm-rotating phases of the motion, high attention scores are observed for the elbow roll angle, indicating that the model focuses on this joint during circular movement. In contrast, in Figure 11c,d and Figure 12c,d, where the arm is lowered, attention score shifts to the shoulder pitch angle, suggesting that the model adapts its focus according to the motion phase.

In Figure 13, for the movement of drawing a circle focusing on the wrist, it can be seen that attention score is largely focused on the elbow. While humans have a pitch angle in the wrist, the robot lacks this degree of freedom. Therefore, it is assumed that the robot compensates for the missing wrist joint angle by using the elbow joint angle.

From Figure 11 and Figure 12, it can be seen that during arm raising and lowering movements, attention score is focused on the shoulder, while in rotational movements, the focus is on the elbow. This indicates that the robot focuses on similar body parts as humans do during these movements. Moreover, Figure 13 shows that although humans focus on the wrist, NAO, lacking a corresponding body part, focuses on the elbow instead. This suggests that even with the embodiment gap, the robot adapted by focusing on alternative body parts.

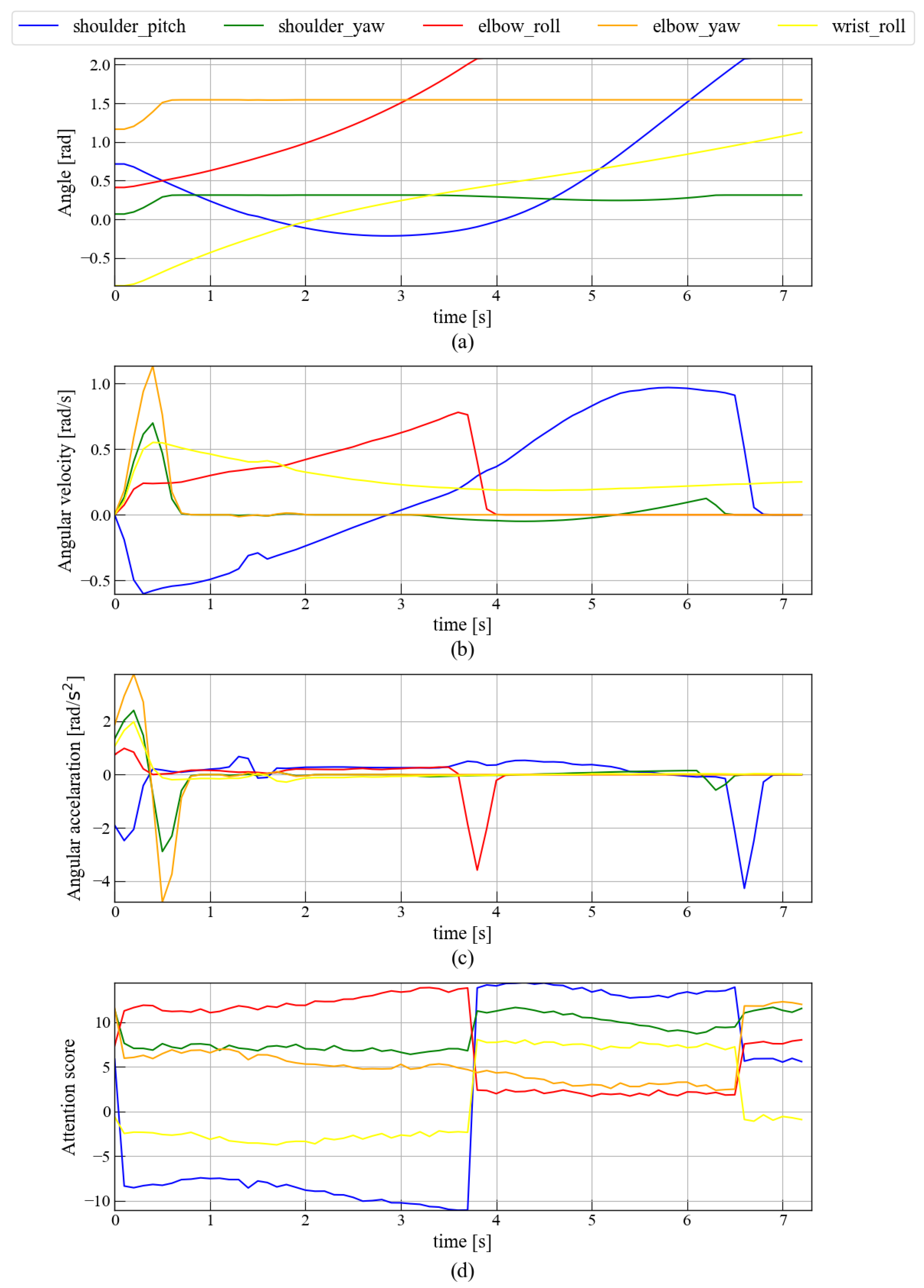

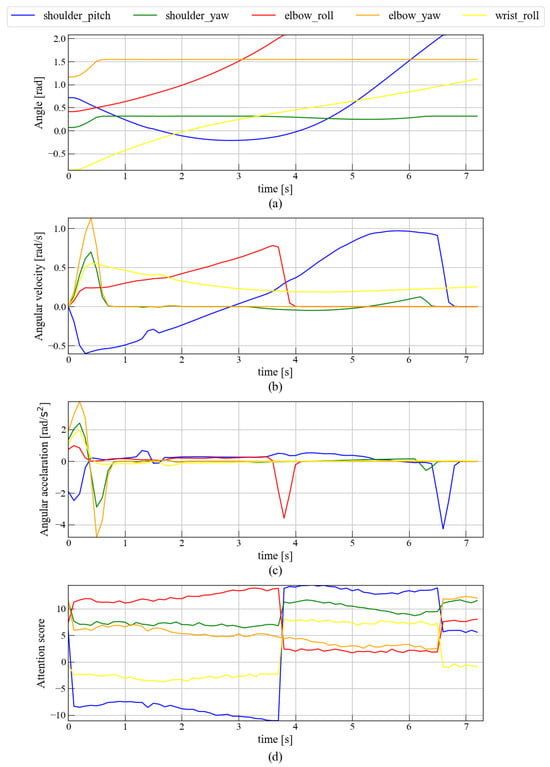

Figure 14 compares joint angle, angular velocity, and angular acceleration with the corresponding attention scores during the entire-arm circle-drawing task. Figure 14a,b,d reveal that the elbow roll undergoing large angular movements receive higher attention. Around 3.7 s, elbow roll movement ceases and its attention score drops sharply from about 14 to 3. Immediately thereafter, the shoulder pitch motion increases markedly when the attention score increases.

Figure 14.

Relationship between attention and whole-arm body movement. This figure is divided into four parts: (a) The transition of joint angles during the movement of drawing a circle with the entire arm. (b) The transition of joint angular velocity during the movement of drawing a circle with the entire arm. (c) The transition of joint angular acceleration during the movement of drawing a circle with the entire arm. (d) The transition of attention during the movement of drawing a circle with the entire arm.

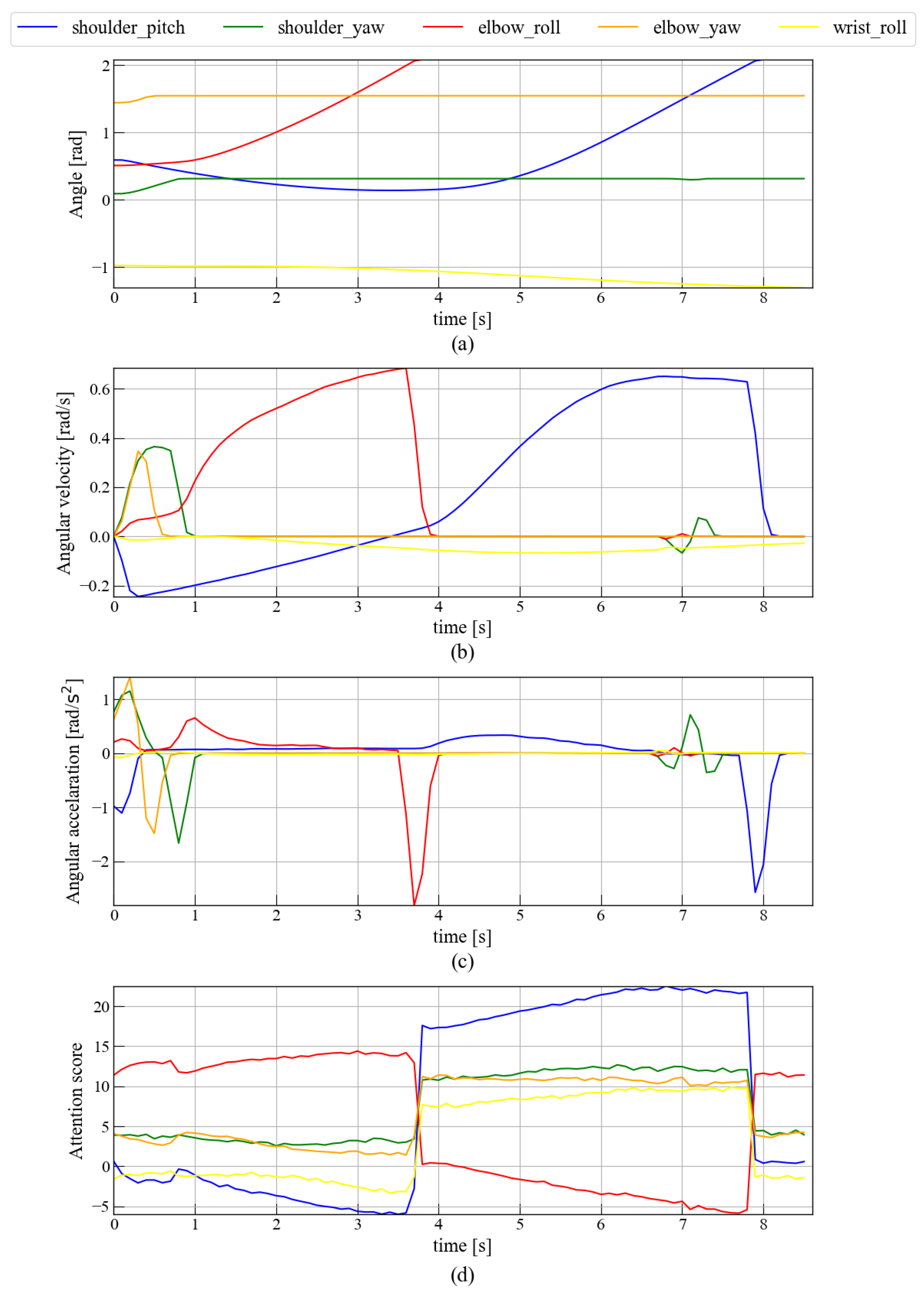

Figure 15 compares joint angle, angular velocity, and angular acceleration with the corresponding attention scores during during the task of drawing a circle centered on the elbow. Figure 15a,b,d reveal that the elbow roll undergoing large angular movements receives higher attention. Around 3.7 s, elbow roll movement ceases and its attention score drops sharply from about 15 to 0. Immediately thereafter, the shoulder pitch motion increases markedly when the attention score increases.

Figure 15.

Relationship between attention and elbow-weighted body movements. This figure is divided into four parts: (a) The transition of joint angles during the movement of drawing a circle centered on the elbow. (b) The transition of joint angular velocity during the movement of drawing a circle centered on the elbow. (c) The transition of joint angular acceleration during the movement of drawing a circle centered on the elbow. (d) The transition of attention during the movement of drawing a circle centered on the elbow.

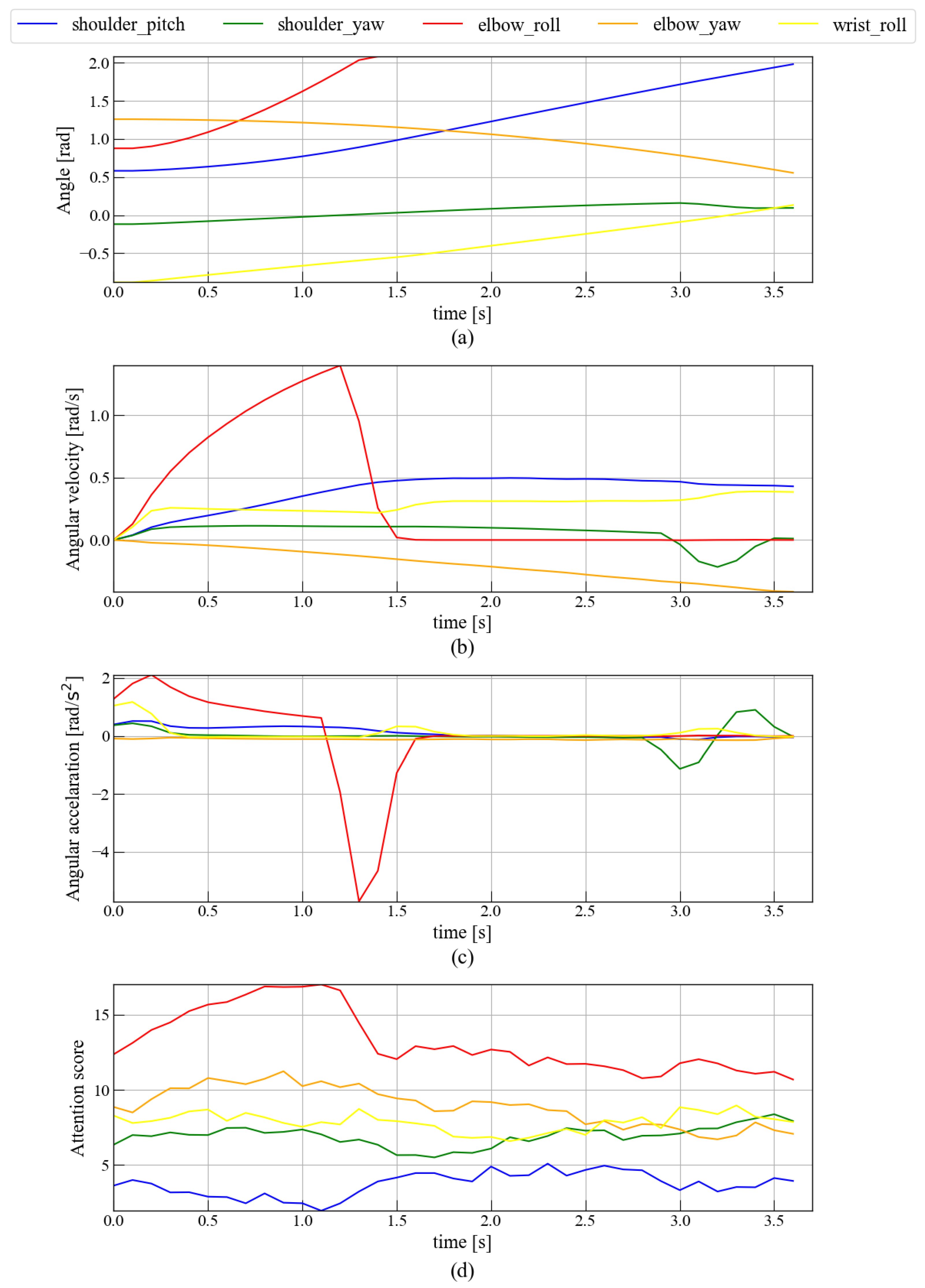

Figure 16 compares joint angle, angular velocity, and angular acceleration with the corresponding attention scores during during the task of drawing a circle centered on the wrist. Figure 16a,b,d reveal that the elbow roll undergoing large angular movements receives higher attention. After that point, the elbow roll angle stops changing when the attention score decreases.

Figure 16.

Relationship between attention and wrist-weighted body movements. This figure is divided into four parts: (a) The transition of joint angles during the movement of drawing a circle centered on the wrist. (b) The transition of joint angular velocity during the movement of drawing a circle centered on the wrist. (c) The transition of joint angular acceleration during the movement of drawing a circle centered on the wrist. (d) The transition of attention during the movement of drawing a circle centered on the wrist.

Further, as shown in Figure 14c and Figure 15c, abrupt shifts in attention often coincide with peaks in joint angular acceleration, especially at the elbow and shoulder. For example, around 3.7 s, a decrease in both elbow motion and attention is followed by increased shoulder activity and attention, indicating a compensatory shift of focus between joints to maintain task performance. In Figure 16c, limited wrist mobility induces compensatory elbow motion, which again aligns with simultaneous increases and decreases in attention and acceleration.

We quantified the functional link between the Transformer’s attention and joint actuation by computing trend-removed correlations (Pearson [54], Spearman [55], Kendall [56]) and mutual information (MI) [57] between joint angular velocity and attention score. Table 2 summarizes the results across three movement patterns.

Table 2.

Trend removed correlation and mutual information between joint angular velocity and attention score.

Key findings are threefold: (i) Shoulder pitch and elbow roll consistently rank highest: under whole-arm motion, elbow roll shows strong associations (Spearman , Kendall , Pearson ), indicating that the model allocates attention in sync with the primary driving joint. (ii) In elbow-weighted motion, both shoulder pitch and elbow roll remain high, but the metric profile differs (e.g., shoulder pitch reaches , while elbow roll shows the largest MI at 1.77 bits), suggesting nonlinear/monotonic dependencies beyond a simple linear link. (iii) In wrist-weighted motion, elbow roll still dominates (, ), implying that even when the task emphasizes distal motion the controller routes driving force through proximal DoFs compatible with the robot’s embodiment.

In most cases, the correlation coefficient exceeds 0.5, indicating a strong correlation [58]. Importantly, all MI values exceed 1 bit, demonstrating substantial information transfer from attention to action that cannot be captured by linear or rank correlation alone. Before analysis, we removed long-term trends to isolate short timescale cofluctuations, ensuring that the reported associations reflect immediate, control-relevant synchrony rather than slow task drift. Together with Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16, these results indicate that the Transformer autonomously identifies and allocates driving force to task-relevant joints, adapting with the movement pattern under embodiment constraints.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we analyzed how the Transformer dynamically allocates attention across body parts in imitation learning between humans and robots. To adapt human motion to different robot embodiments, imitation movements were estimated by solving forward and inverse kinematics with the Levenberg–Marquardt method, enabling motion generation that considers differences in link lengths and joint configurations. Demonstration data were segmented and refined using the k-means++ clustering algorithm to extract representative motion features, which stabilized training and allowed the Transformer to capture distinct movement patterns. Furthermore, the temporal transitions of attention were visualized using UMAP, allowing interpretation of how the model dynamically shifts its focus between body parts during imitation. This framework provides a systematic approach to understanding the relationship between robot motion and the Transformer’s internal attention mechanisms, offering insight into how embodiment differences influence imitation learning behavior.

The results demonstrated that the Transformer effectively learned to allocate attention across body parts, and a consistent relationship was observed between attention changes and variations in joint angles, angular velocities, and accelerations. In particular, the correspondence between abrupt changes in attention and peaks in joint acceleration suggests that attention may exert an influence on motion generation. Furthermore, a high correlation was obtained between attention and angular velocity, indicating that the attention mechanism reflects the dynamic characteristics of motion. These findings imply that the Transformer’s attention mechanism autonomously identifies the joints most relevant to each motor task and appropriately distributes control effort among them.

Future research will extend this framework toward result-level and intent-level imitation, integrating Active Inference or variational Bayesian control to model goal-directed behavior beyond movement-level imitation. Additionally, incorporating multi-robot generalization and energy-based embodiment metrics will further enable scalable imitation across heterogeneous platforms. Through these directions, the proposed framework is expected to serve as a foundation for next-generation embodied imitation systems that autonomously reason about how and why to imitate rather than merely reproducing human motion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T. and K.S.; methodology, Y.T. and K.S.; software, Y.T.; validation, Y.T. and K.S.; formal analysis, Y.T.; investigation, Y.T.; resources, Y.T.; data curation, Y.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T. and K.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.T. and K.S.; visualization, Y.T.; supervision, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants. The images included in this manuscript are anonymized (e.g., applied blurring to the face). Because the images do not allow identification of individuals and the use involves minimal risk, written consent was not obtained; participants agreed to the use of the anonymized image data in the submitted manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OECD. OECD Employment Outlook 2025: Can We Get Through the Demographic Crunch? OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argall, B.D.; Chernova, S.; Veloso, M.; Browning, B. A survey of robot learning from demonstration. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2009, 57, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinon, S.; Billard, A. Incremental learning of gestures by imitation in a humanoid robot. In Proceedings of the 2007 2nd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Washington, DC, USA, 9–11 March 2007; pp. 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Tykal, M.; Montebelli, A.; Kyrki, V. Incrementally assisted kinesthetic teaching for programming by demonstration. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–10 March 2016; pp. 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Koenemann, J.; Burget, F.; Bennewitz, M. Real-time imitation of human wholebody motions by humanoids. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 2806–2812. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; McCarthy, Z.; Jow, O.; Lee, D.; Chen, X.; Goldberg, K.; Abbeel, P. Deep imitation learning for complex manipulation tasks from virtual reality teleoperation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 5628–5635. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M.; Sekiyama, K. Human-Robot Imitation Learning of Movement for Embodiment Gap. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Cybern, Oahu, HI, USA, 1–4 October 2023; pp. 1733–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.; Bashkirov, S.; Rico, J.F.; Toriyama, I.; Miyada, N.; Yanagisawa, H.; Ishizuka, K. Learning Bipedal Robot Locomotion from Human Movement. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 2797–2803. [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeyer, T.; Torr, P.; Henriques, J.F. Learn what matters: Cross-domain imitation learning with task-relevant embeddings. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 26283–26294. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Chopra, S.; Hadsell, R.; Ranzato, M.; Huang, F. A tutorial on energy-based learning. Predicting Structured Data; Bakir, G., Hofman, T., Scholkopf, B., Smola, A., Taskar, B., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Florence, P.; Lynch, C.; Zeng, A.; Ramirez, O.A.; Wahid, A.; Downs, L.; Wong, A.; Lee, J.; Mordatch, I.; Tompson, J. Implicit Behavioral Cloning. In Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Robot Learning, Zurich, Switzerland, 29–31 October 2018; pp. 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Hidalgo, G.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.-E.; Sheikh, Y. OpenPose:Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation using Part Affinity Fields. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Delmerico, J.; Poranne, R.; Bogo, F.; Oleynikova, H.; Vollenweider, E.; Coros, S.; Nieto, J.; Pollefeys, M. Spatial Computing and Intuitive Interaction: Bringing Mixed Reality and Robotics Together. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2022, 29, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Park, H.A.; Yuan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Sentis, L. LEGATO: Cross-Embodiment Imitation Using a Grasping Tool. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 2854–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, C.; Li, Y. Tool-as-interface: Learning robot policies from human tool usage through imitation learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.04612. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.Z.; Kumar, V.; Levine, S.; Finn, C. Learning fine-grained bimanual manipulation with low-cost hardware. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.13705. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiullah, N.M.M.; Cui, Z.J.; Altanzaya, A.A.; Pinto, L. Behavior Transformers: Cloning k modes with one stone. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.11251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lu, K.; Rajeswaran, A.; Lee, K.; Grover, A.; Laskin, M.; Abbeel, P.; Srinivas, A.; Mordatch, I. Decision Transformer: Reinforcement Learning via Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.01345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotar, Y.; Vuong, Q.; Hausman, K.; Xia, F.; Lu, Y.; Irpan, A.; Kumar, A.; Yu, T.; Herzog, A.; Pertsch, K.; et al. Q-Transformer: Scalable Offline Reinforcement Learning via Autoregressive Q-Functions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.10150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Carbajal, J.; Chebotar, Y.; Dabis, J.; Finn, C.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Hausman, K.; Herzog, A.; Hsu, J.; et al. RT-1: Robotics Transformer for Real-World Control at Scale. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.06817. [Google Scholar]

- Zitkovich, B.; Yu, T.; Xu, S.; Xu, P.; Xiao, T.; Xia, F.; Wu, J.; Wohlhart, P.; Welker, S.; Wahid, A.; et al. RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.15818. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, M.; Sommut, C. A Framework for Behavioral Cloning. Mach. Intell. 1999, 15, 103–129. [Google Scholar]

- De Giacomo, G.; Iocchi, L.; Favorito, M.; Patrizi, F. Restraining bolts for reinforcement learning agents. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 13659–13662. [Google Scholar]

- Zakka, K.; Zeng, A.; Florence, P.; Tompson, J.; Bohg, J.; Dwibedi, D. Xirl: Cross embodiment inverse reinforcement learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.03911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, T.G.W.; Lee, O.Y.; Liu, C.K.; Bohg, J. Crossing the human-robot embodiment gap with sim-to-real rl using one human demonstration. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.12609. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Yu, M.; Dong, Z.; Calinon, S.; Caldwell, D.; Chen, F. Human-Humanoid Robots Cross-Embodiment Behavior-Skill Transfer Using Decomposed Adversarial Learning from Demonstration. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.15166. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Xu, Z.; Chi, C.; Veloso, M.; Song, S. Xskill: Cross embodiment skill discovery. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), Atlanta, GA, USA, 6–9 November 2023; pp. 3536–3555. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Lin, C.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; et al. Human2LocoMan: Learning Versatile Quadrupedal Manipulation with Human Pretraining. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.16475. [Google Scholar]

- Dessalene, E.; Mantripragada, P.; Maynord, M.; Aloimonos, Y. EmbodiSwap for Zero-Shot Robot Imitation Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.03706. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Bharadhwaj, H.; Tulsiani, S. DemoDiffusion: One-Shot Human Imitation using pre-trained Diffusion Policy. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20668. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Liu, S.; Jiang, H.; Yang, R.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X. DexMV: Imitation Learning for Dexterous Manipulation from Human Videos. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 570–587. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. Behavioral Cloning from Observation. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligencem, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018; pp. 4950–4957. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. Generative adversarial imitation from observation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06158. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. Imitation Learning from Video by Leveraging Proprioception. In Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Macao, Chaina, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 3585–3591. [Google Scholar]

- Karnan, H.; Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. Adversarial Imitation Learning from Video Using a State Observer. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 2452–2458. [Google Scholar]

- Pavse, B.S.; Torabi, F.; Hanna, J.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. RIDM: Reinforced Inverse Dynamics Modeling for Learning from a Single Observed Demonstration. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 6262–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. DEALIO: Data-Efficient Adversarial Learning for Imitation from Observation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 2391–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Finn, C.; Xie, A.; Dasari, S.; Zhang, T.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. One-shot imitation from observing humans viadomain-adaptive meta-learning. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 26–30 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sermanet, P.; Lynch, C.; Hsu, J.; Levine, S. Time-Contrastive Networks: SelfSupervised Learning from Multi-view Observation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 486–487. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, E.; Warnell, G.; Torabi, F.; Stone, P. Skeletal Feature Compensation for Imitation Learning with Embodiment Mismatch. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–17 May 2022; pp. 2482–2488. [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma, H.; Ito, H.; Mori, H.; Ogata, T. Deep Active Visual Attention for Real-Time Robot Motion Generation: Emergence of Tool-Body Assimilation and Adaptive Tool-Use. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 8550–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, T. Solvability-Unconcerned Inverse Kinematics by the Levenberg- Marquardt Method. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2011, 27, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.S.; Park, D.D.H.; Lee, Y.B.; Han, D.G.; Su, S.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, P.C.W. A study on the measurement of wrist motion range using the iPhone 4 gyroscope application. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2014, 73, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moromizato, K.; Kimura, R.; Fukase, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ishida, H. Whole-body patterns of the range of joint motion in young adults: Masculine type and feminine type. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2016, 35, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwerus, E.L.; Willigenburg, N.W.; Scholtes, V.A.; Somford, M.P.; Eygendaal, D.; van den Bekerom, M.P.J. Normative values and affecting factors for the elbow range of motion. Shoulder Elb. 2019, 11, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macqueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In 5-th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, D.; Vassilvitskii, S. k-means++: The advantages of careful seeding. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, New Orleans, LA, USA, 7–9 January 2007; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 1027–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.; Müller, K.R. Nonlinear Component Analysis as a Kernel Eigenvalue Problem. Neural Comput. 1998, 10, 1299–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar]

- Busy, M.; Caniot, M. qiBullet, a Bullet-based simulator for the Pepper and NAO robots. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.00779. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick, P. Pearson’s correlation coefficient. BMJ 2012, 345, e4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissler, C. The Spearman correlation formula. Science 1905, 22, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, H. The Kendall rank correlation coefficient. Encycl. Meas. Stat. 2007, 2, 508–510. [Google Scholar]

- Kraskov, A.; Stögbauer, H.; Grassberger, P. Estimating mutual information. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 066138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).