Cross-Embodiment Kinematic Behavioral Cloning (X-EKBC): An Energy-Based Framework for Human–Robot Imitation Learning with the Embodiment Gap

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Motion-level imitation: imitation involves directly mapping the demonstrator’s limb trajectories onto the robot’s corresponding joints, reproducing the observed kinematics.

- Result-level imitation: Reproducing the results of actions such as picking and placing objects.

- Intent-level imitation: Imitation that incorporates intent. For example, whether the action is intended for pick-and-place or merely to move something out of the way.

- Generalization of robot kinematics using the joint matrix, enabling consistent imitation learning across robots with different structures using the same human demonstration data.

- Energy-based evaluation of embodiment gaps, allowing quantitative assessment of embodiment gaps and enabling motion-level comparison across robots with heterogeneous structures, which has been difficult in conventional approaches.

2. Related Work

2.1. Demonstration Collection Methods Addressing Embodiment Gaps

2.2. Imitation Learning Approaches

2.2.1. Behavioral Cloning as a Baseline

2.2.2. Addressing Embodiment Gap

2.2.3. Imitation from Observation

3. Cross-Embodiment Kinematic Behavioral Cloning (X-EKBC)

3.1. System Architecture of X-EKBC

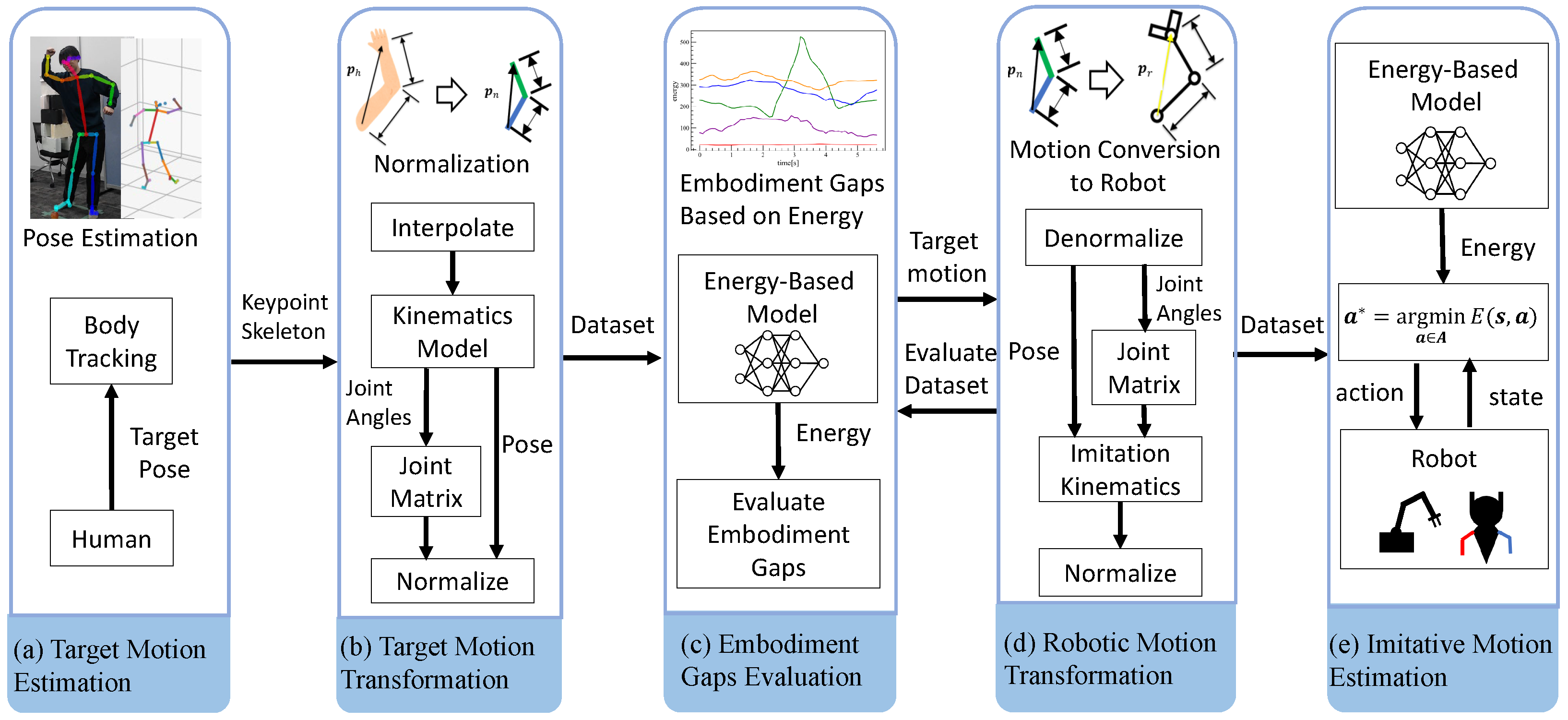

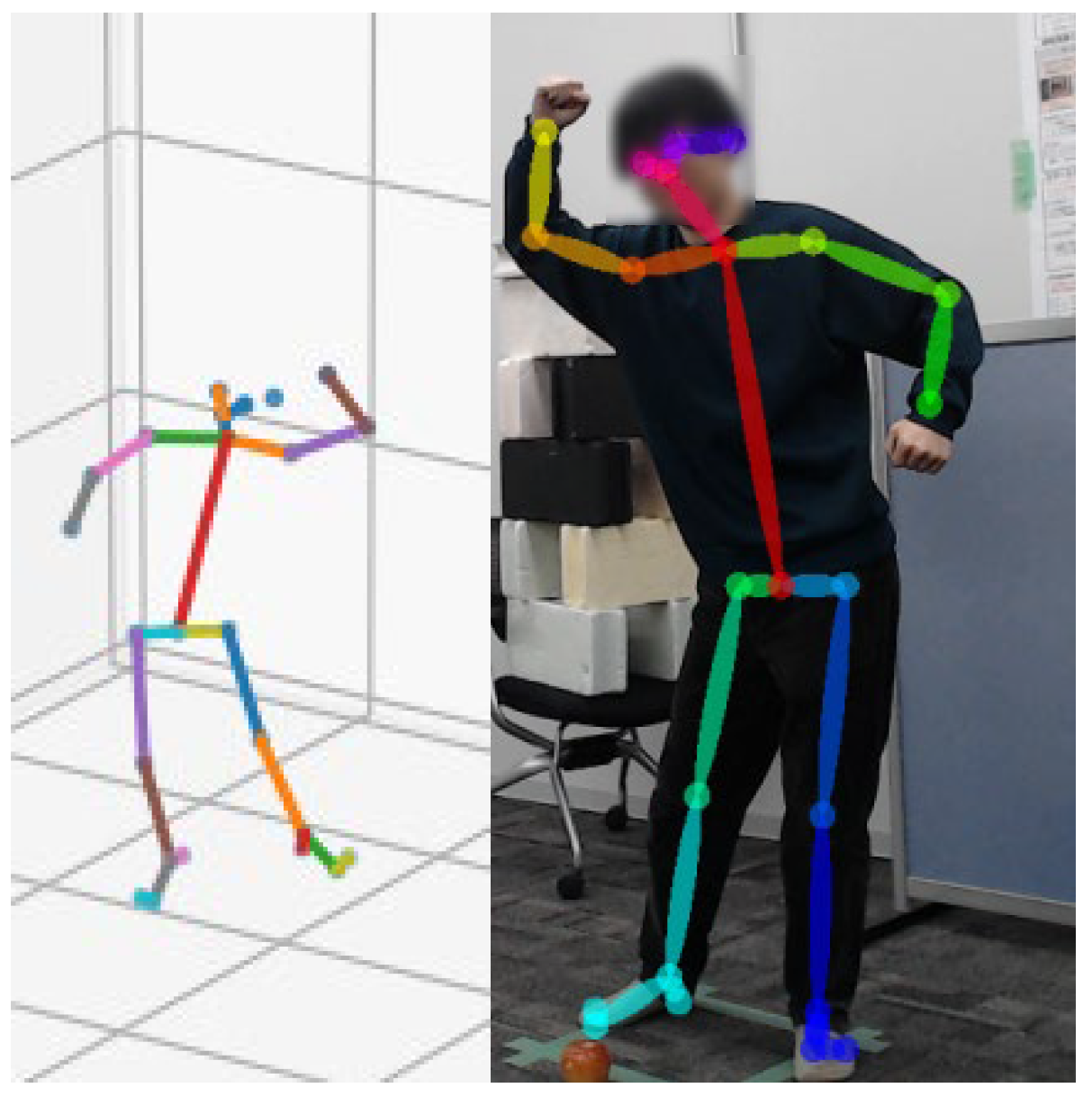

- In Figure 2a, the demonstrator’s motion is estimated. This is achieved by extracting a skeletal model from visual recordings of the demonstrator.

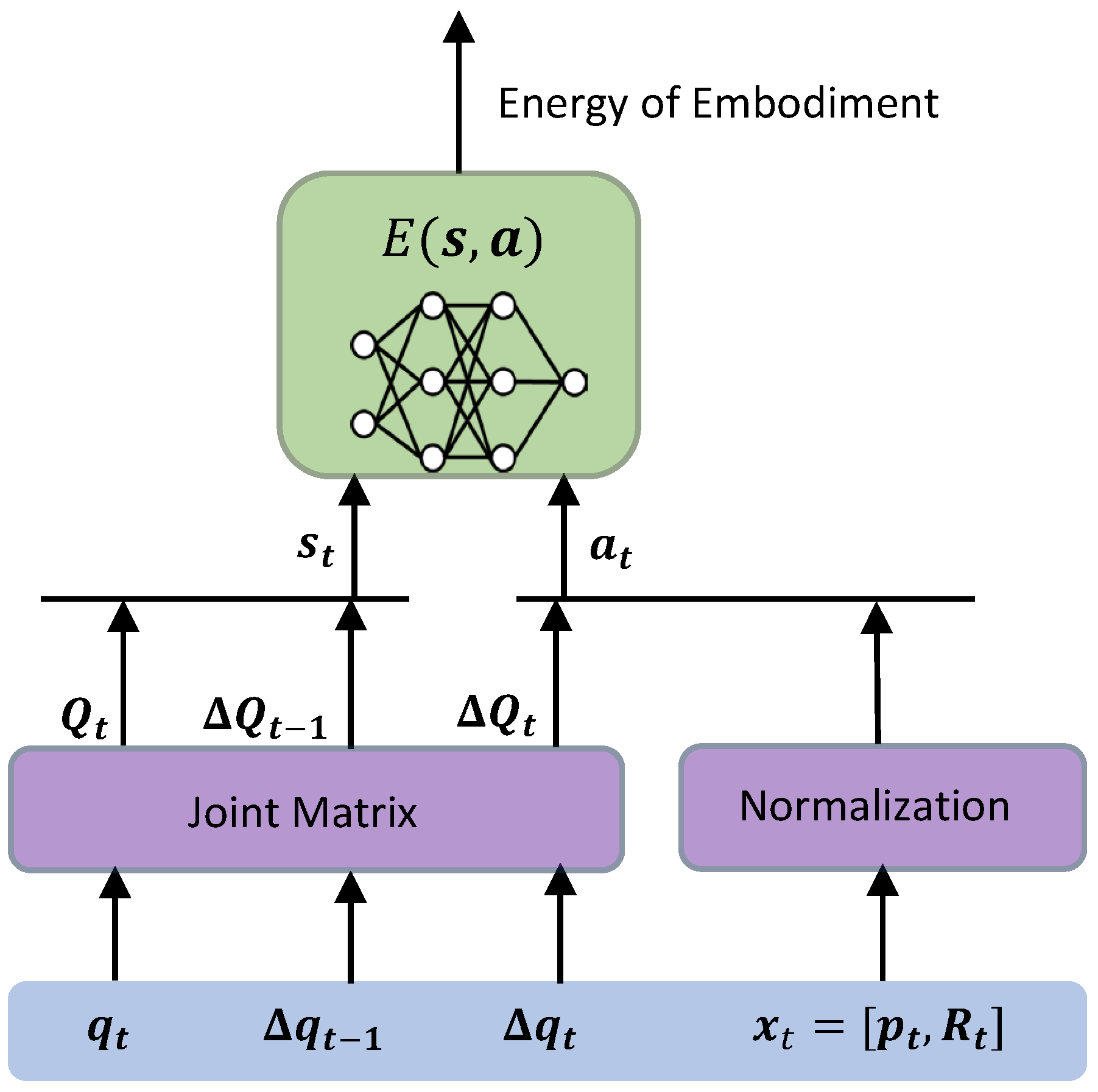

- In Figure 2b, the estimated motion undergoes preprocessing for generalization. Specifically, joint angles and end-effector poses are computed from the skeletal model, followed by normalization of feasible motion ranges and transformation into a matrix form using the newly defined joint matrix.

- In Figure 2c, an embodiment model of the demonstrator is learned. This model is represented in the form of an EBM.

- In Figure 2d, the embodiment gaps between the demonstrator and the robot are evaluated. The demonstrator’s motion is transformed into multiple candidate trajectories adapted to the robot’s embodiment, and the learned embodiment model is used to select the transformation that minimizes embodiment discrepancy.

- Finally, in Figure 2e, the robot learns an imitation behavior model, which is also trained using an EBM.

3.2. Acquisition of Demonstrator Motion Through Observation

3.3. Motion Transformation of the Demonstrator

3.3.1. Normalization of the Motion Space

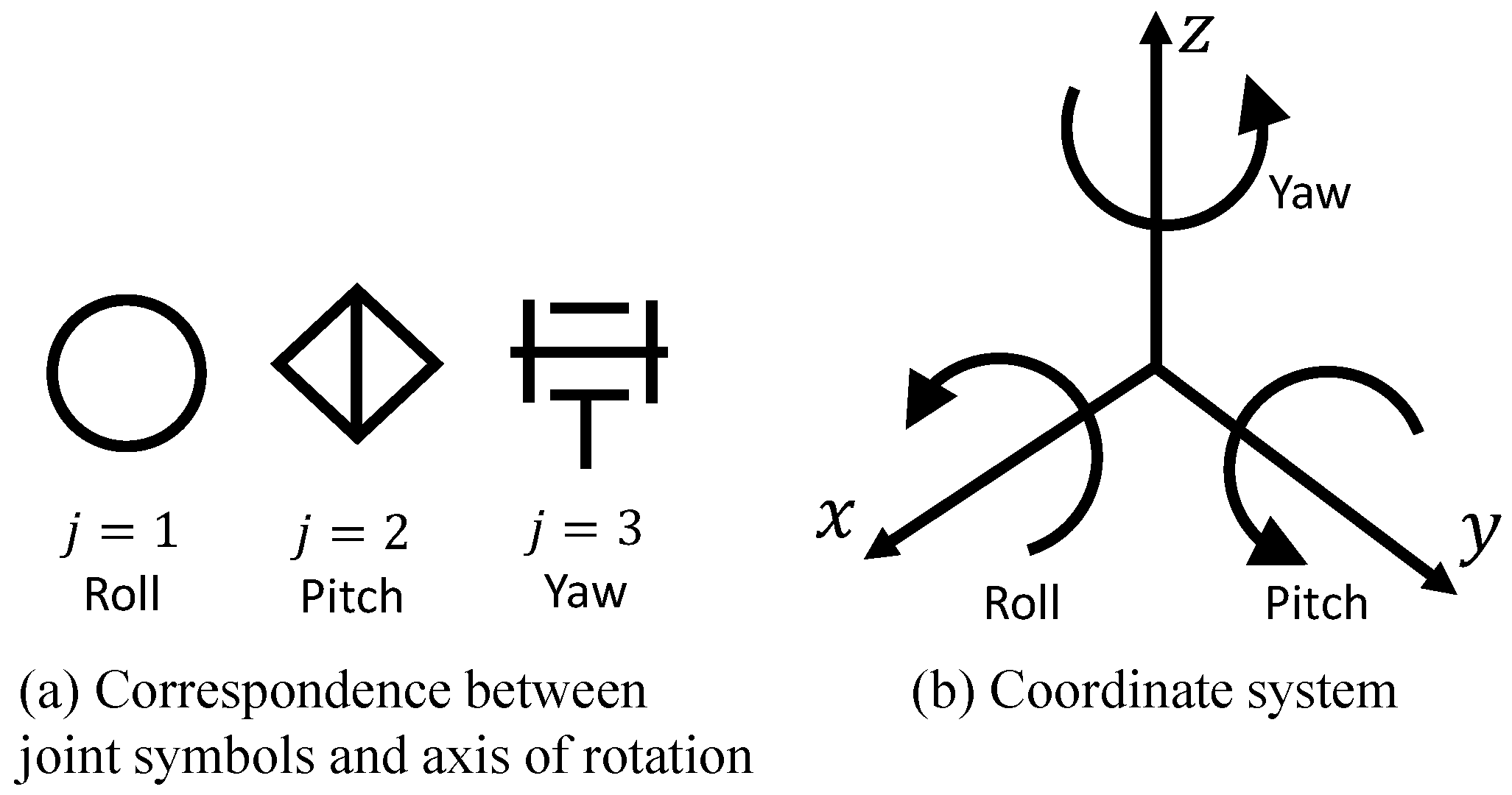

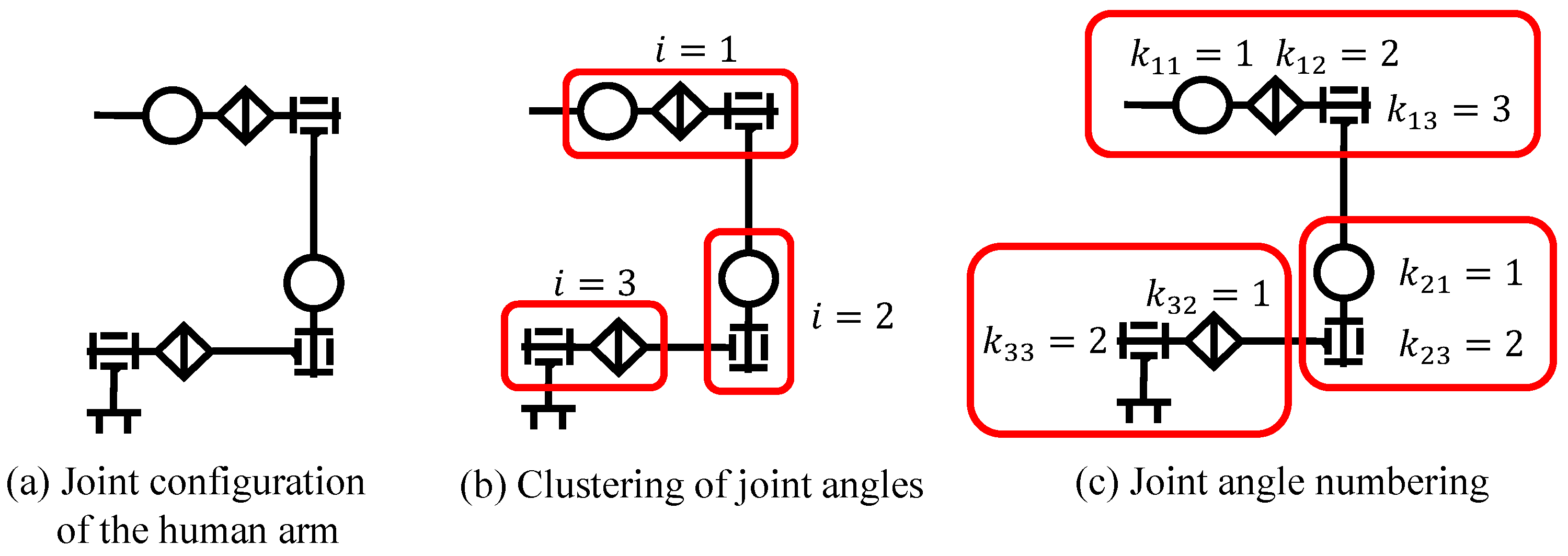

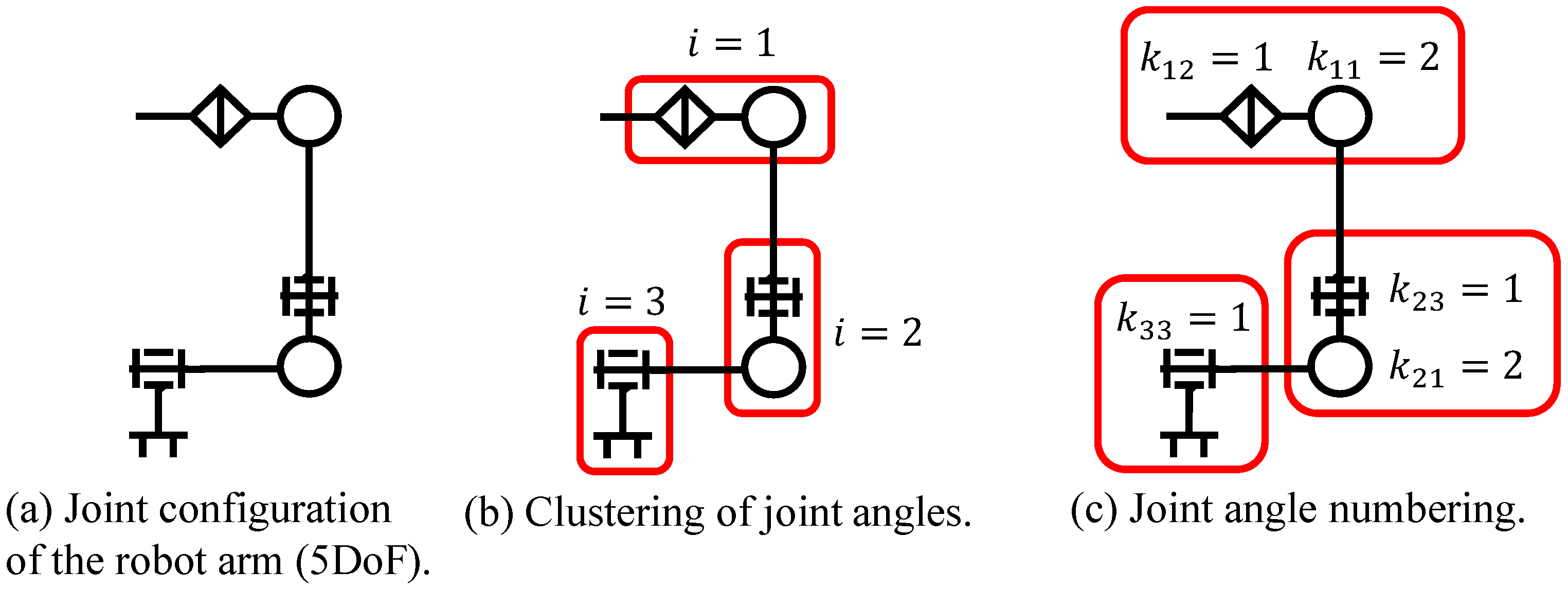

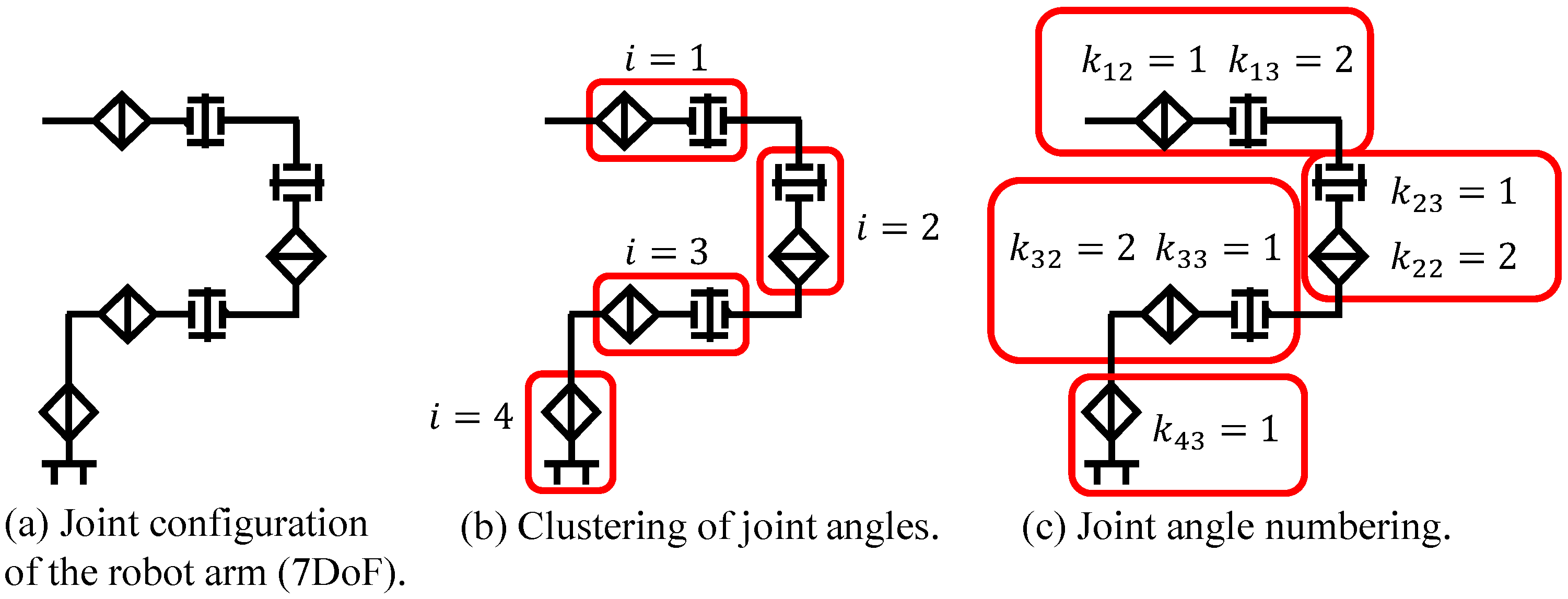

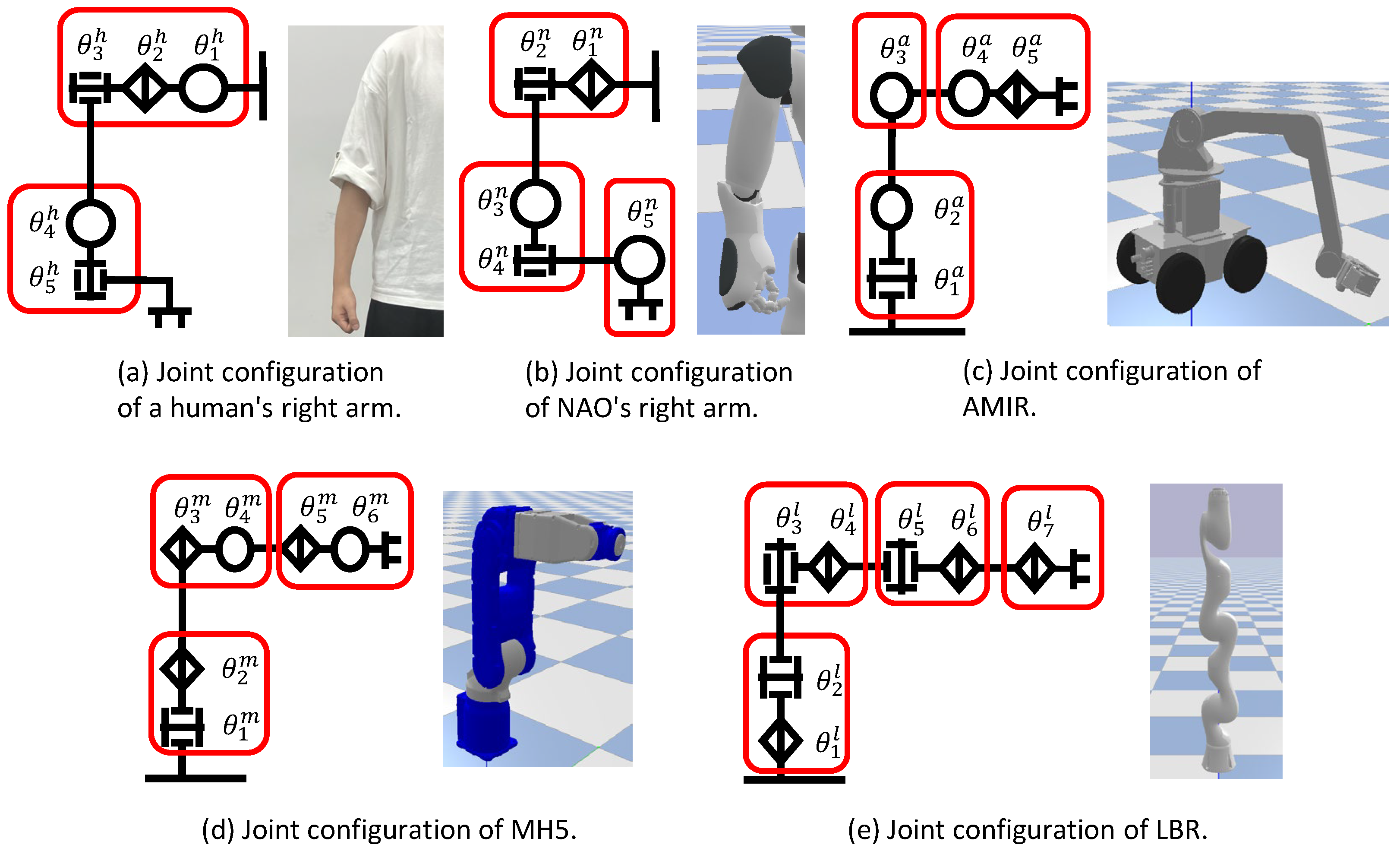

3.3.2. Transformation of Joint Configurations

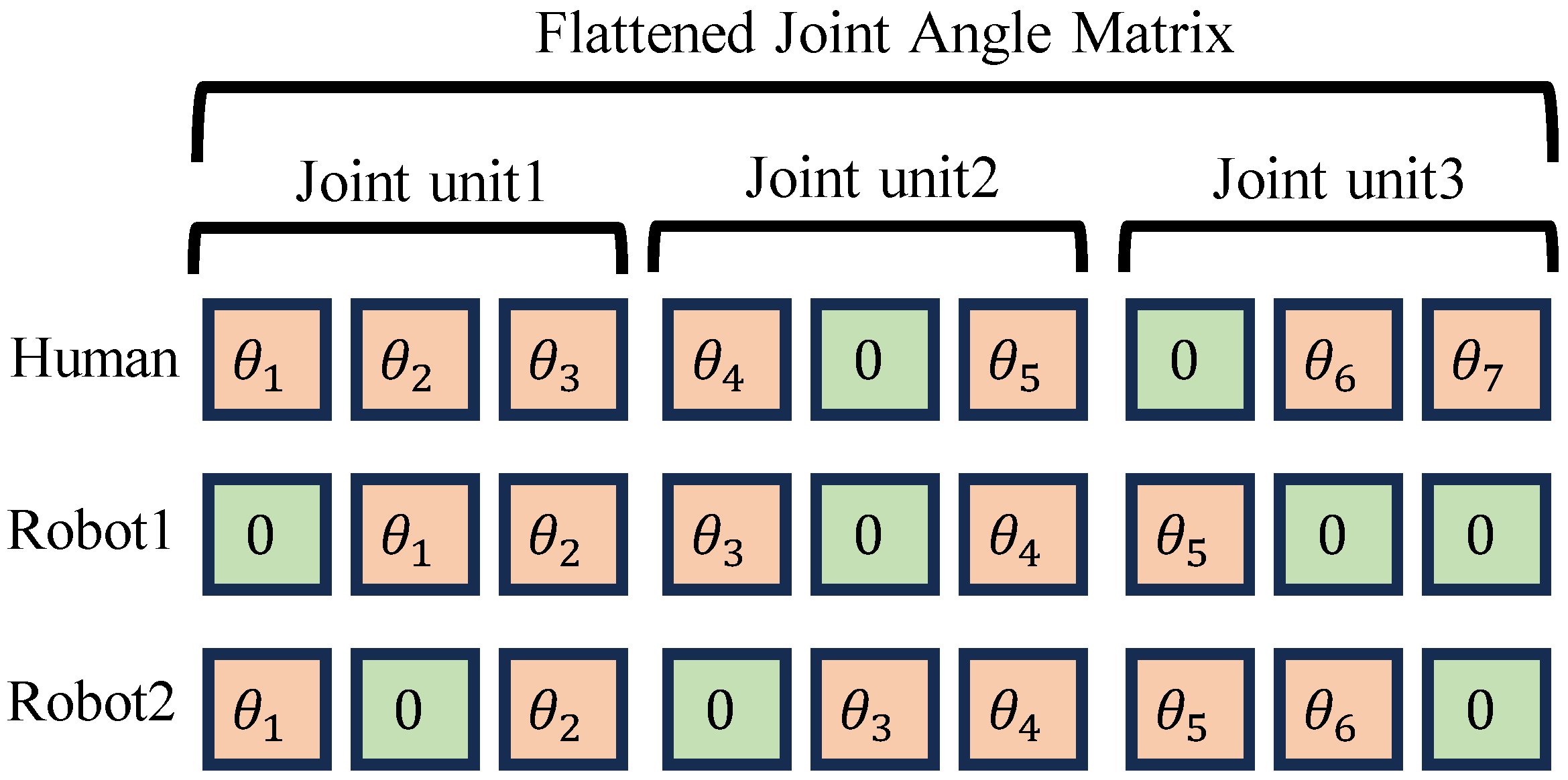

- Neighboring joints that are physically connected are grouped and treated as a single joint unit.

- Each joint unit contains only one element for each rotational axis.

- The elements within a joint unit are numbered according to the order of the rotational axes, counting from the base link.

3.3.3. Imitation Kinematics for Imitation Learning

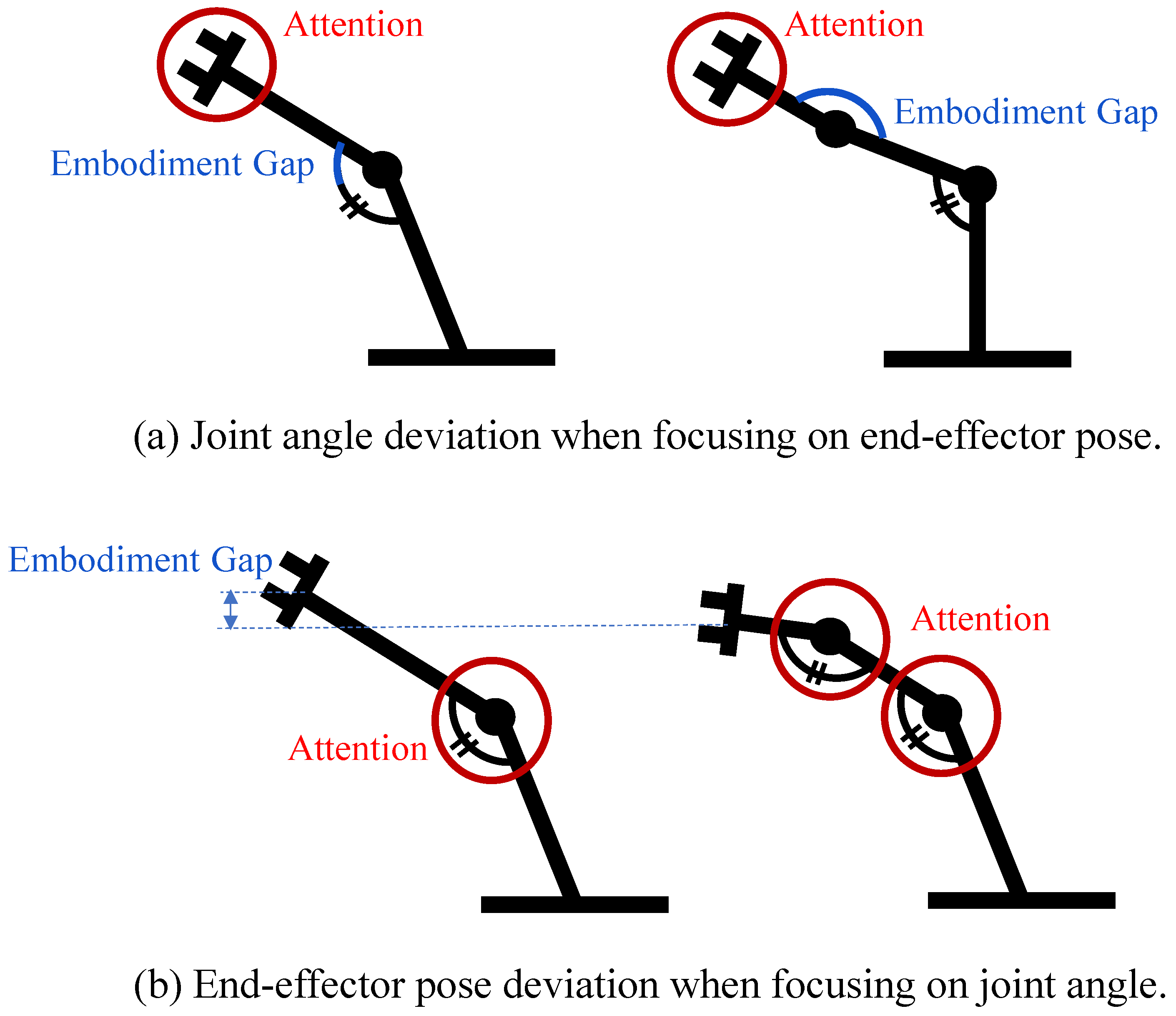

- Due to the embodiment gaps, it is unlikely that a robot state exists that simultaneously satisfies both the target end-effector pose and the target joint angles.

- In , the joint angles that do not exist in the demonstrator are set to 0 [rad].

| Algorithm 1 Imitation Kinematics |

|

3.4. Learning Embodiment and Imitative Movement

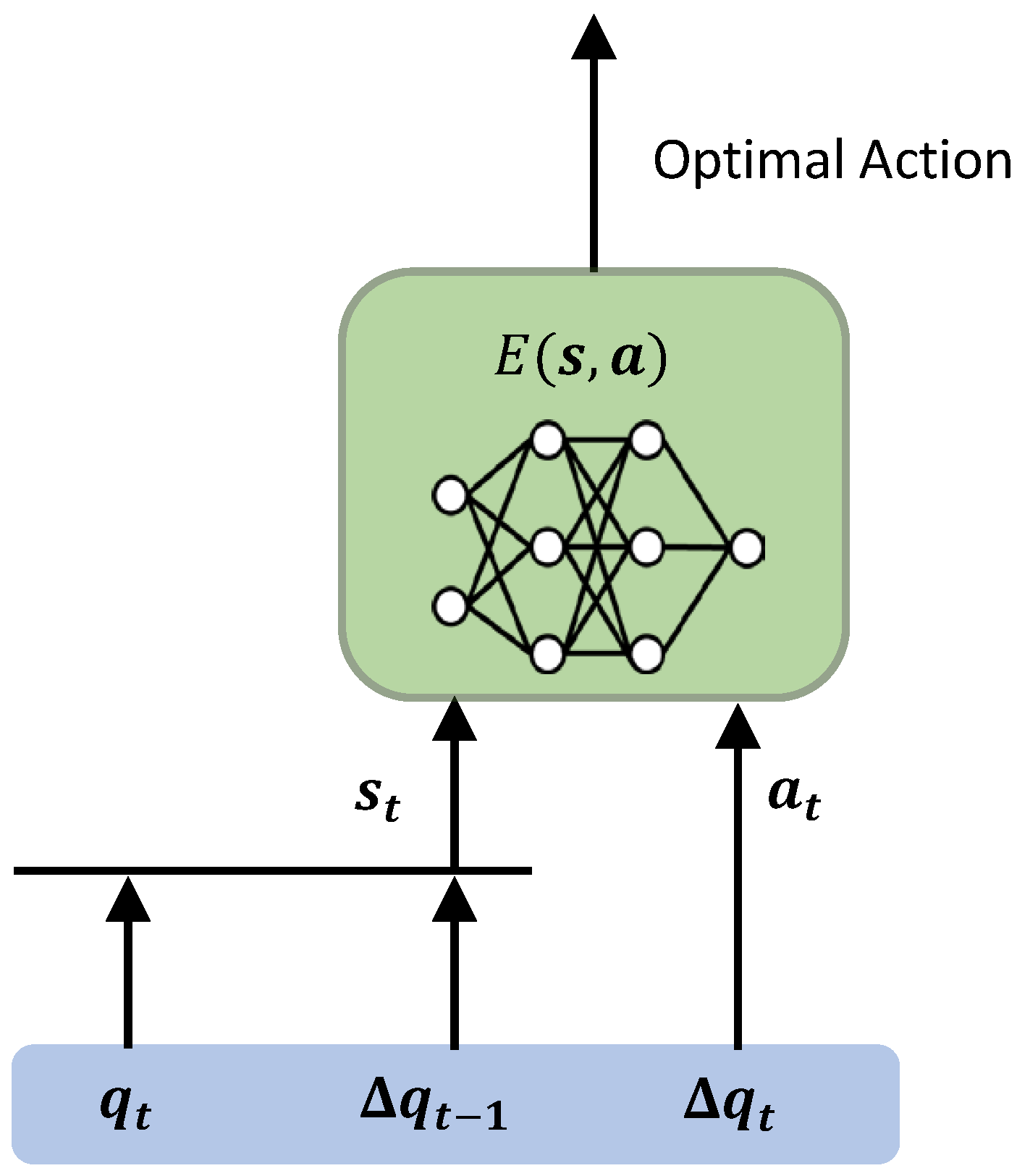

3.4.1. Evaluation of Compatibility by Energy-Based Model

| Algorithm 2 Importance Sampling |

|

3.4.2. Embodiment Model of Demonstrator and Imitative Movement Model of Robot

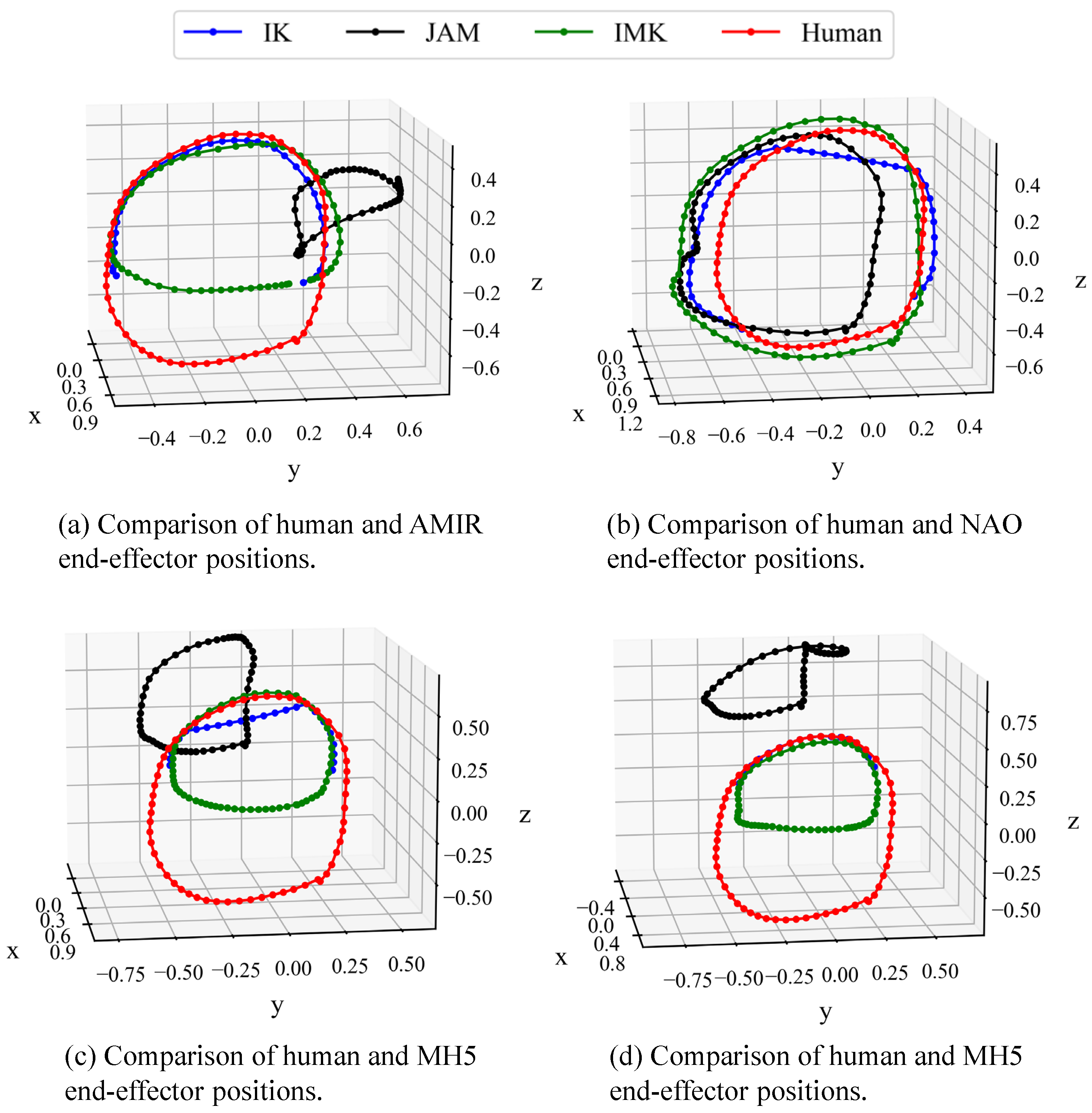

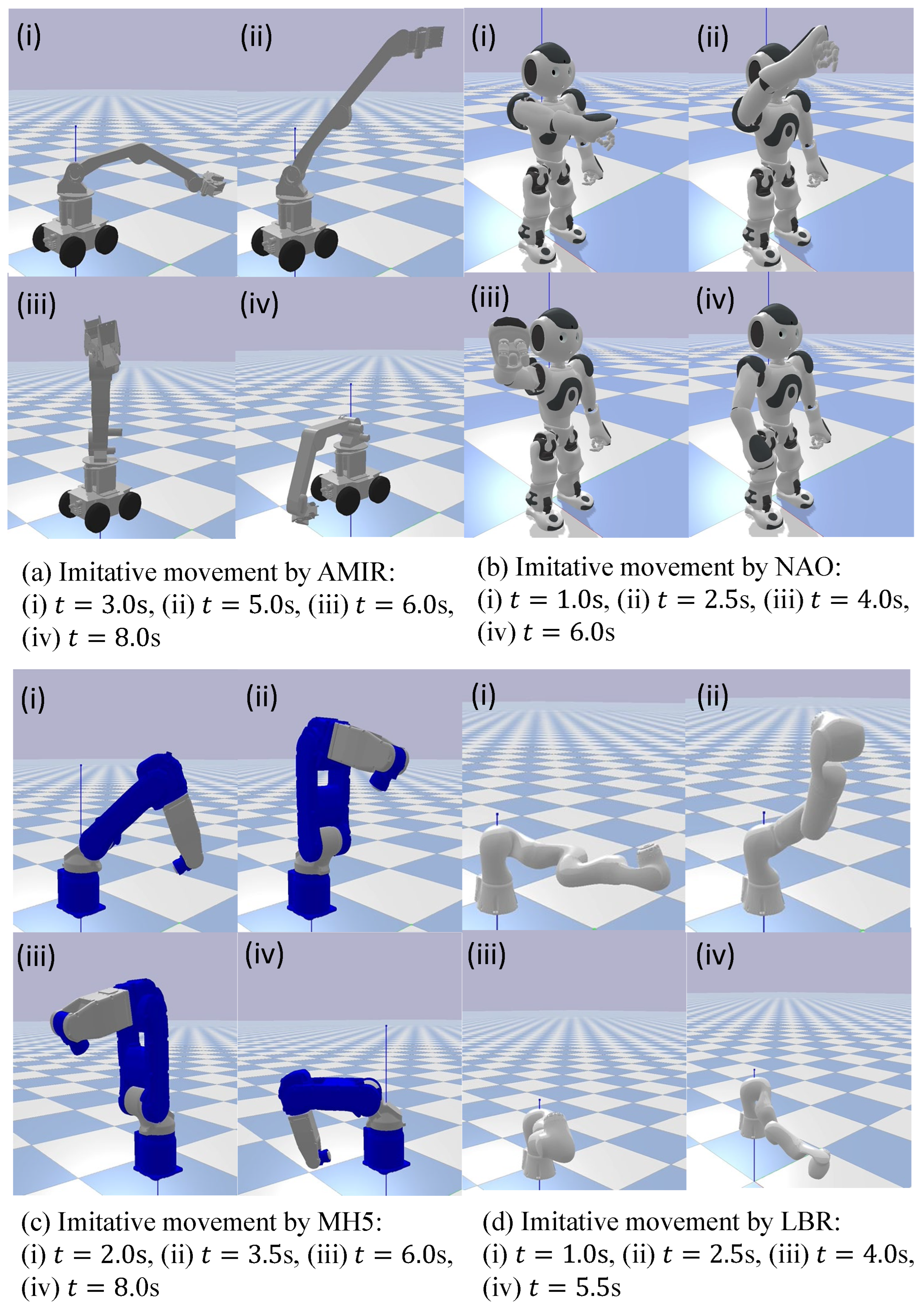

4. Imitation Learning Considering Embodiment Gap Using X-EKBC

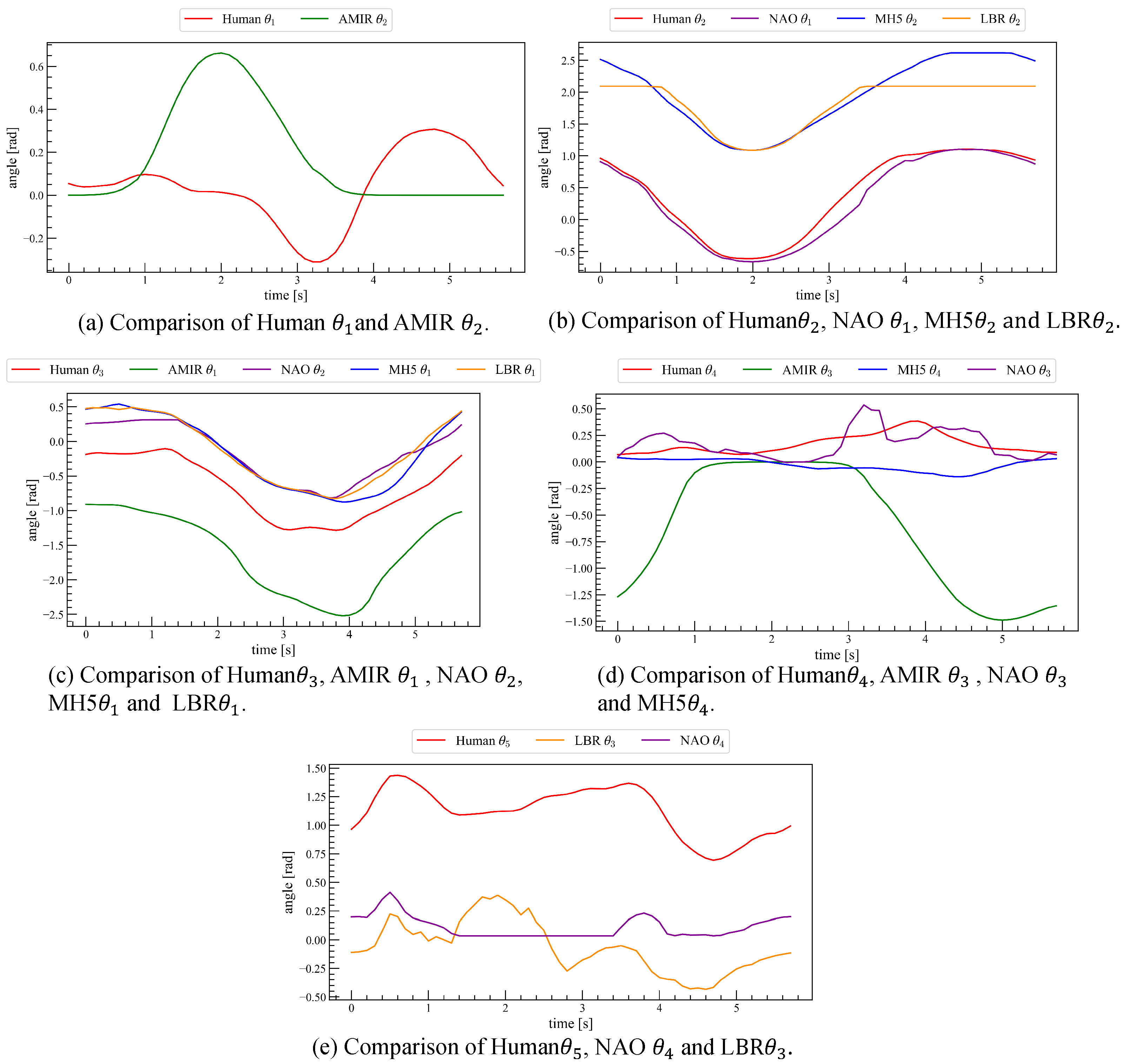

4.1. Motion Reconstruction Using Joint Matrices

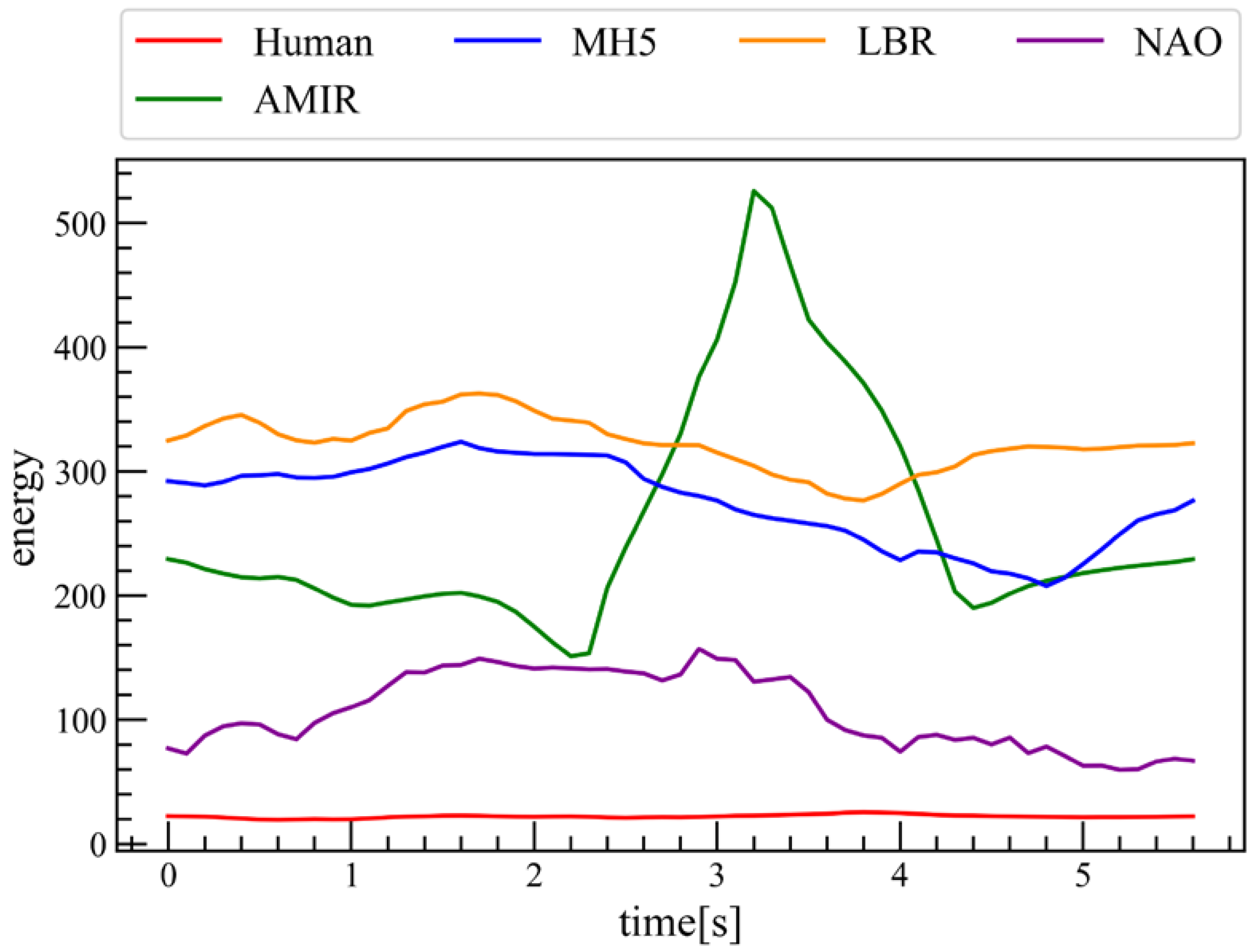

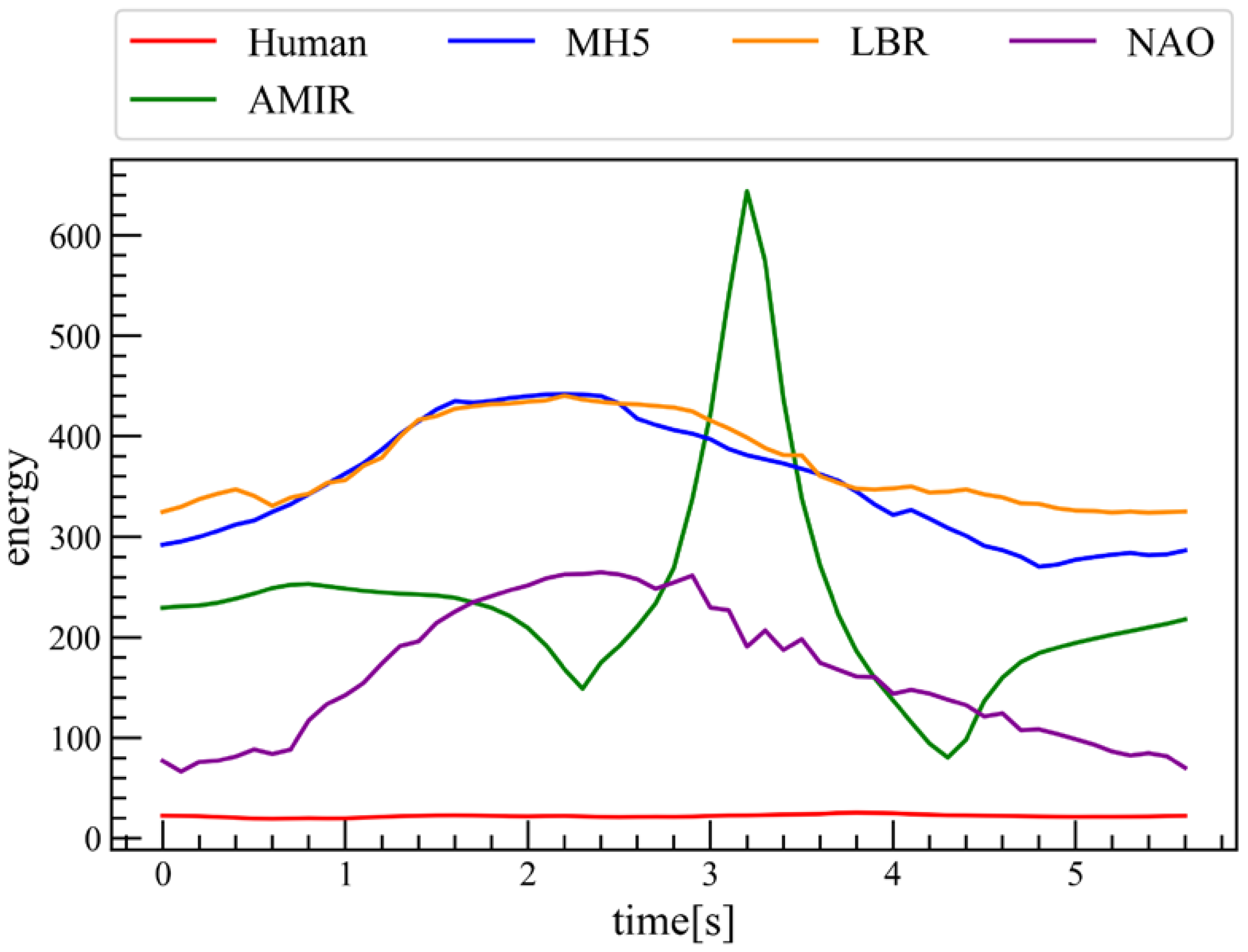

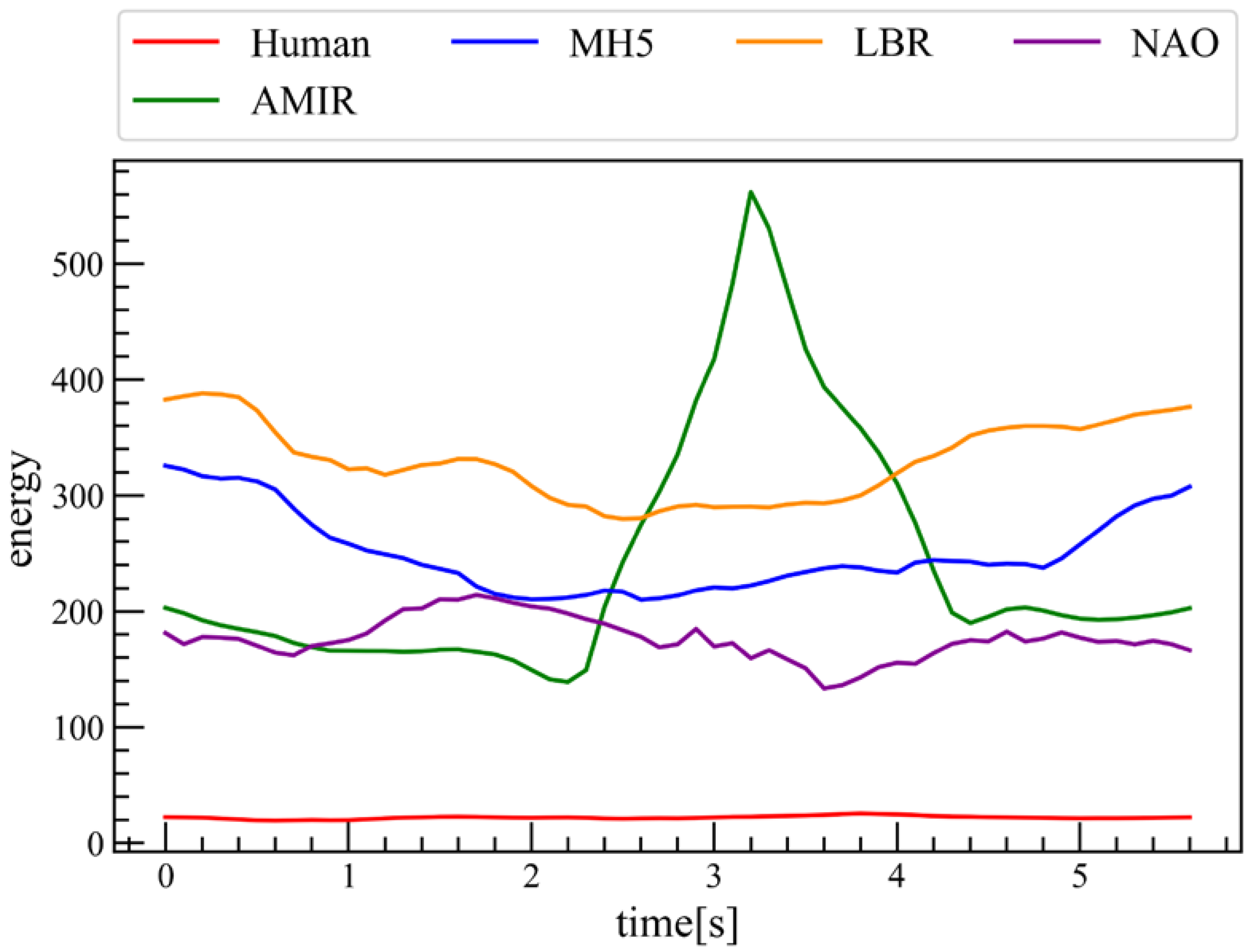

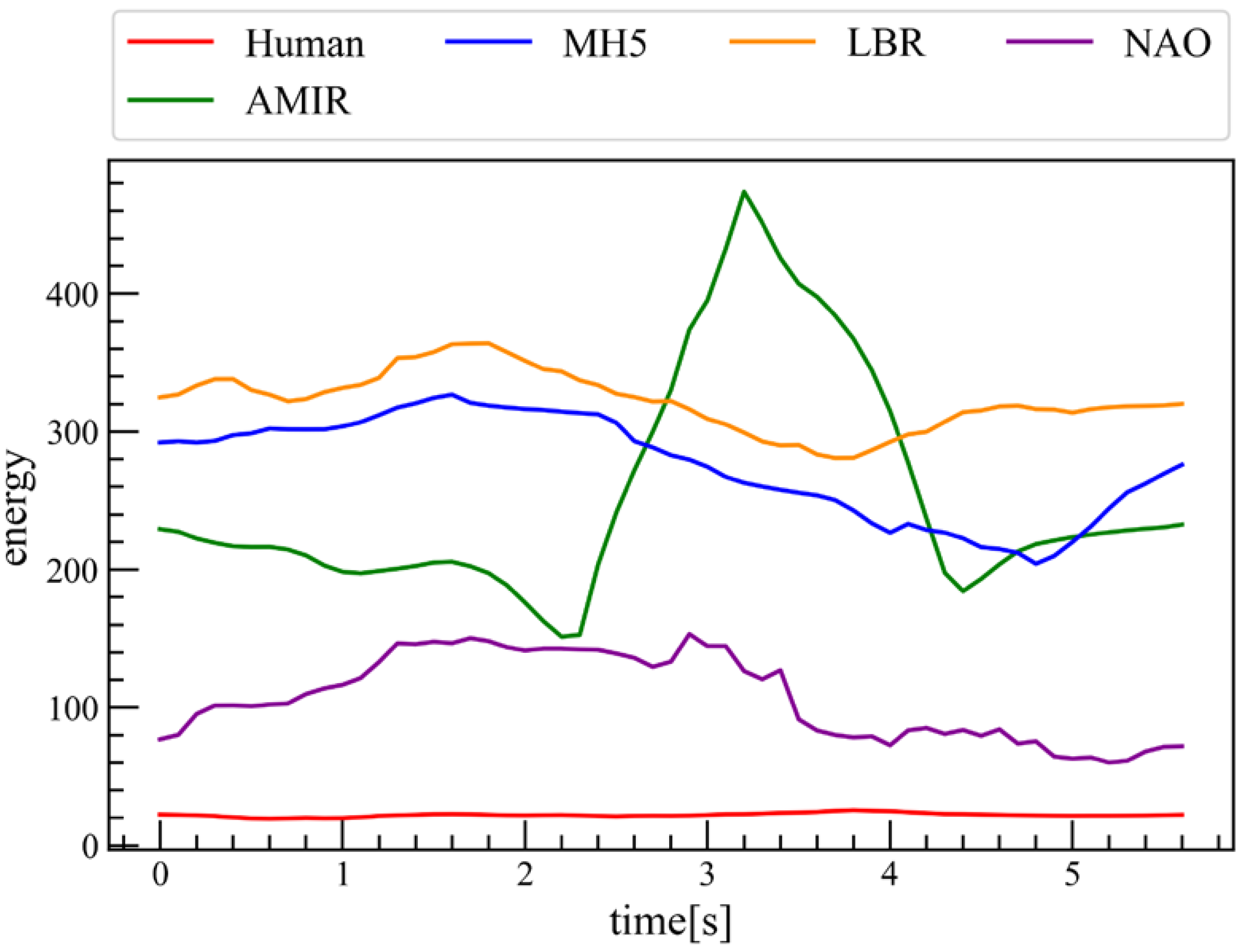

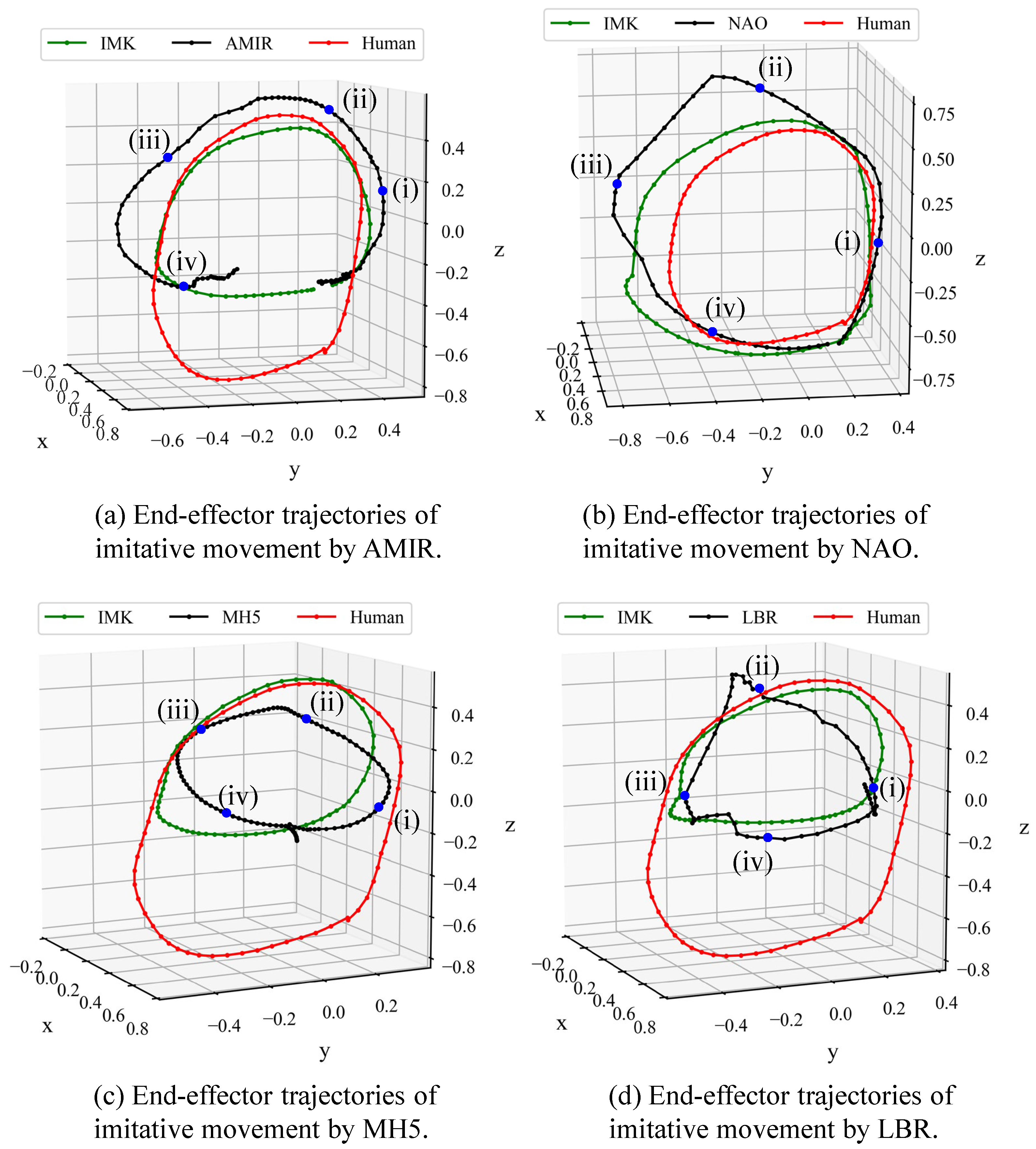

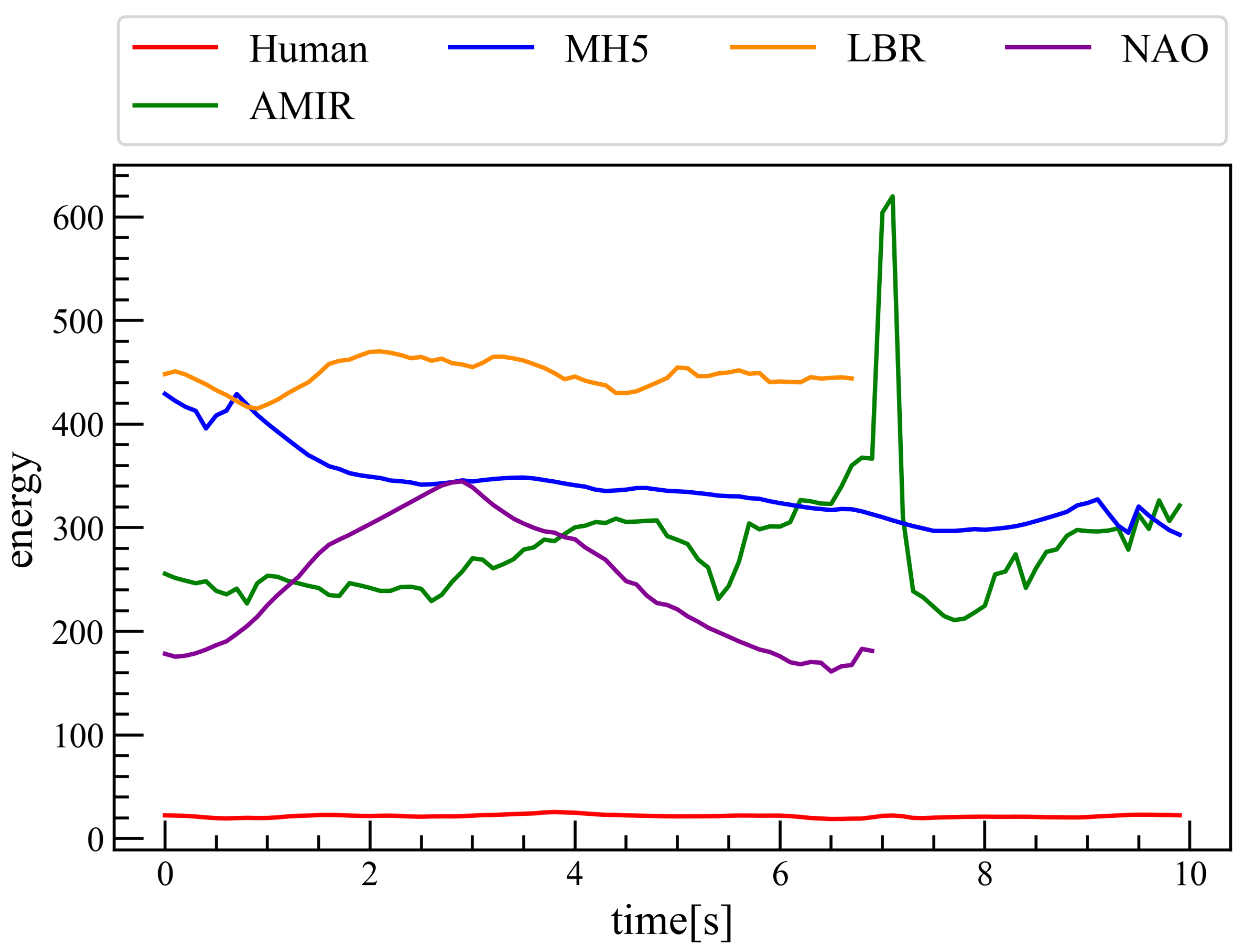

4.2. Quantifying Embodiment Gap Through EBM

4.3. Imitation Learning with IBC

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Argall, B.D.; Chernova, S.; Veloso, M.; Browning, B. A survey of robot learning from demonstration. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2009, 57, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; McCarthy, Z.; Jow, O.; Lee, D.; Chen, X.; Goldberg, K.; Abbeel, P. Deep imitation learning for complex manipulation tasks from virtual reality teleoperation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 5628–5635. [Google Scholar]

- Tykal, M.; Montebelli, A.; Kyrki, V. Incrementally assisted kinesthetic teaching for programming by demonstration. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–10 March 2016; pp. 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.; Bashkirov, S.; Rico, J.F.; Toriyama, I.; Miyada, N.; Yanagisawa, H.; Ishizuka, K. Learning Bipedal Robot Locomotion from Human Movement. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 2797–2803. [Google Scholar]

- Zakka, K.; Zeng, A.; Florence, P.; Tompson, J.; Bohg, J.; Dwibedi, D. Xirl: Cross embodiment inverse reinforcement learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.03911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Chopra, S.; Hadsell, R.; Ranzato, M.; Huang, F. A tutorial on energy-based learning. In Predicting Structured Data; Bakir, G., Hofman, T., Scholkopf, B., Smola, A., Taskar, B., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Florence, P.; Lynch, C.; Zeng, A.; Ramirez, O.A.; Wahid, A.; Downs, L.; Wong, A.; Lee, J.; Mordatch, I.; Tompson, J. Implicit Behavioral Cloning. In Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Robot Learning, Zurich, Switzerland, 29–31 October 2018; pp. 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M.; Sekiyama, K. Human-Robot Imitation Learning of Movement for Embodiment Gap. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Cybern, MD, USA, 1–4 October 2023; pp. 1733–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M.; Sekiyama, K. Human-Robot Imitation Learning for Embodiment Gap. Master’s Thesis, Meijo University, Nagoya, Japan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Delmerico, J.; Poranne, R.; Bogo, F.; Oleynikova, H.; Vollenweider, E.; Coros, S. Spatial Computing and Intuitive Interaction: Bringing Mixed Reality and Robotics Together. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2022, 29, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Park, H.A.; Yuan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Sentis, L. LEGATO: Cross-Embodiment Imitation Using a Grasping Tool. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 2854–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Mohan, L.; Pinto, L.; Gupta, A. Multiple interactions made easy (MIME): Large scale demonstrations data for imitation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning, Zürich, Switzerland, 29–31 October 2018; pp. 906–915. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Suh, H.J.; Zhao, T.; Graesdal, B.P.; Kelestemur, T.; Wang, J.; Pang, T.; Tedrake, R. Physics-driven data generation for contact-rich manipulation via trajectory optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.20382. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Johns, E. One-Shot Dual-Arm Imitation Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.06831. [Google Scholar]

- Lum, T.G.W.; Lee, O.Y.; Liu, C.K.; Bohg, J. Crossing the human-robot embodiment gap with sim-to-real rl using one human demonstration. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.12609. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, P.; Kedia, K.; Chao, A.; Duan, E.W.; Pace, M.A.; Ma, W.C.; Choudhury, S. X-Sim: Cross-Embodiment Learning via Real-to-Sim-to-Real. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.07096. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, M.; Sommut, C. A Framework for Behavioral Cloning. Mach. Intell. 1999, 15, 103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, C.; Levine, S.; Abbeel, P. Guided Cost Learning: Deep Inverse OptimalControl via Policy Optimization. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 20–22 June 2016; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Ermon, S. Generative adversarial imitation learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.03476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.Z.; Kumar, V.; Levine, S.; Finn, C. Learning fine-grained bimanual manipulation with low-cost hardware. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.13705. [Google Scholar]

- Franzmeyer, T.; Torr, P.; Henriques, J.F. Learn what matters: Crossdomain imitation learning with task-relevant embeddings. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.12093. [Google Scholar]

- Fickinger, A.; Cohen, S.; Russell, S.; Amos, B. Cross-domain imitation learning via optimal transport. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.03684. [Google Scholar]

- Sermanet, P.; Lynch, C.; Hsu, J.; Levine, S. Time-Contrastive Networks: SelfSupervised Learning from Multi-view Observation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 486–487. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Xu, Z.; Chi, C.; Veloso, M.; Song, S. Xskill: Cross embodiment skill discovery. In Proceedings of the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), Atlanta, GA, USA, 6–9 November 2023; pp. 3536–3555. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Kang, J.; Kang, H.; Cho, M.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y. UniSkill: Imitating Human Videos via Cross-Embodiment Skill Representations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.08787. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, L.; Agboh, W.C.; Hogg, D.C.; Fuentes, R. O2a: One-shot observational learning with action vectors. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 686368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, A.; Rehman, A.; Gupta, A.; Maddukuri, A.; Gupta, A.; Padalkar, A.; Lee, A.; Pooley, A.; Gupta, A.; Mandlekar, A.; et al. Open X-Embodiment: Robotic Learning Datasets and RT-X Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2310.08864. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. Behavioral Cloning from Observation. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligencem, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018; pp. 4950–4957. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. Generative adversarial imitation from observation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06158. [Google Scholar]

- Pavse, B.S.; Torabi, F.; Hanna, J.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. RIDM: Reinforced Inverse Dynamics Modeling for Learning from a Single Observed Demonstration. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 6262–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. DEALIO: Data-Efficient Adversarial Learning for Imitation from Observation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 2391–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, E.; Warnell, G.; Torabi, F.; Stone, P. Skeletal Feature Compensation for Imitation Learning with Embodiment Mismatch. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 2482–2488. [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma, H.; Ito, H.; Mori, H.; Ogata, T. Deep Active Visual Attention for Real-Time Robot Motion Generation: Emergence of Tool-Body Assimilation and Adaptive Tool-Use. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 8550–8557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, T. Solvability-Unconcerned Inverse Kinematics by the Levenberg-Marquardt Method. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2011, 27, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Martinez, G.H.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.E.; Sheikh, Y. OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation using Part Affinity Fields. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Tola, D.; Corke, P. Understanding urdf: A dataset and analysis. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 4479–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busy, M.; Caniot, M. qiBullet, a Bullet-based simulator for the Pepper and NAO robots. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.00779. [Google Scholar]

| Symbol | Definition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| i | joint set order | - |

| j | rotation axis | 1: Roll 2: Pitch 3: Yaw |

| joint order | 0: No joint |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsunekawa, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Sekiyama, K. Cross-Embodiment Kinematic Behavioral Cloning (X-EKBC): An Energy-Based Framework for Human–Robot Imitation Learning with the Embodiment Gap. Machines 2025, 13, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121134

Tsunekawa Y, Tanaka M, Sekiyama K. Cross-Embodiment Kinematic Behavioral Cloning (X-EKBC): An Energy-Based Framework for Human–Robot Imitation Learning with the Embodiment Gap. Machines. 2025; 13(12):1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121134

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsunekawa, Yoshiki, Masaki Tanaka, and Kosuke Sekiyama. 2025. "Cross-Embodiment Kinematic Behavioral Cloning (X-EKBC): An Energy-Based Framework for Human–Robot Imitation Learning with the Embodiment Gap" Machines 13, no. 12: 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121134

APA StyleTsunekawa, Y., Tanaka, M., & Sekiyama, K. (2025). Cross-Embodiment Kinematic Behavioral Cloning (X-EKBC): An Energy-Based Framework for Human–Robot Imitation Learning with the Embodiment Gap. Machines, 13(12), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13121134