Abstract

The International Energy Agency (IEA) asserts that worldwide electricity demand is rising exponentially every year. Energy storage is the cornerstone of electricity demand. Gravity-based energy storage systems represent the optimum alternative for energy storage systems. They offer zero carbon emission, environmental sustainability, cost-effectiveness, geographical flexibility, long-duration storage, and scalability ranging from 0.5 to 10 GWh. This research introduces a novel design to confirm the workability of the gravity energy storage model. It validates the feasibility of the system through the drive train setup. The drive train model involves storing potential energy by elevating the stack weight using solar photovoltaic input and releasing the weight to generate electrical energy using the gravitational field. The gravity motion is theoretically proven by the mathematical analysis, drive train control system transfer function model, and golden ratio-based design. Solidworks simulation model enhances the working of the drive train setup. Through hardware iterative experimental results with different load profiles, validate the performance metrics. The gravity energy storage system’s feasibility is demonstrated by its scalability in comparison with battery energy systems. Gravity-based energy storage is the best option for utility-scale renewable energy grid integration, since it has a low energy density, medium and large capacity, long-lasting storage, and high scalability.

1. Introduction

By 2050 the 70% of electricity demand will be contributed by renewable energy sources. Globally, the predominant factor for solving electrical problems is the strengthening of the energy storage system. The need for an efficient energy storage system is to fulfill the intermittency of the renewable energy system. Energy storage is vital for the reliability of the electrical grid system [1], optimizing electrical energy distribution, and reducing the impact of global warming through fossil fuels. The electrical energy storage in terms of electrochemical systems dominates the overall energy storage market. Other storage systems have limitations like geographical and environmental conditions, scalability, upfront cost, deployment, and other factors. The gravity energy storage system is one of the alternative energy storage systems [2], by utilizing the gravitational field impact on the potential energy of the stack weight [3]. These systems store the surplus energy by hoisting the stack weight and generate electricity by releasing the stack weight. The stack weight moves downwards due to the vital action of the Earth’s gravitational field, with low environmental footprints and utilization of natural resources. This renewable energy storage system is the sustainable optimal choice for storing longer-duration energy systems [4].

1.1. Motivation of the Study

This research article investigates the workability of the gravity energy storage system and assesses the scope of gravity storage technology. The objective is to design and verify the gravity energy storage system experimentally and to create a positive impact on the gravity storage system.

1.2. Significance of the Study

The key contribution of this article includes mathematical analysis, a transfer function model, Solidworks 2022 simulation, golden ratio implementation, a novel design of a renewable-energy-sourced gravity energy storage system with a drive train model, hardware setup, iterative experimental analysis of power across different load setup, a comparative study with a battery storage system, estimation of 1 kW gravity energy storage system, and scalability analysis.

The proposed model aims to achieve the following:

- 1

- Quantify gravity system workability and characterize energy conversion performance.

- 2

- Classify the design parameters and operational stability for efficient power output.

- 3

- Provide a validated framework of gravity energy storage technologies for sustainable and reliable power applications.

1.3. Problem Statement

Even though gravity energy systems have a lot of potential, there are issues with their upfront cost, energy efficiency, environmental conditions, drive train mechanical model, utility-scale interaction with electrical grids, large-scale deployment, and scalability [5].

The proposed research highlights the workability of the gravity mechanism to generate efficient load torque at the output. This is essential for practical electromechanical energy conversion.

This paper proceeds with the following structure:

- Describe the types and detailed comparison of energy storage systems.

- Classify the gravity energy storage system based on the surface, movement, material, and mechanism.

- Propose the modified gravity energy storage system and showcase the hardware setup of the system.

- Experimentally verify the working process and compare with the standard system.

- Conclude with a recommendation and focus the future exploration for research and development in gravity energy storage integration.

By presenting an alternative efficient method of electricity storage in terms of gravity beyond conventional battery-based systems, the research clarifies its novelty and provides meaningful insights into the design potential and applicability of gravity-based energy storage technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Energy Storage System

2.1.1. Architecture of Energy Storage System

Storing surplus energy from a system for a standby condition is called energy storage. Storing energy is a very hectic process when compared to energy generation. The energy storage leads to loss of energy due to conversion processes like mechanical, chemical, electrical, hydraulic, and pneumatic.

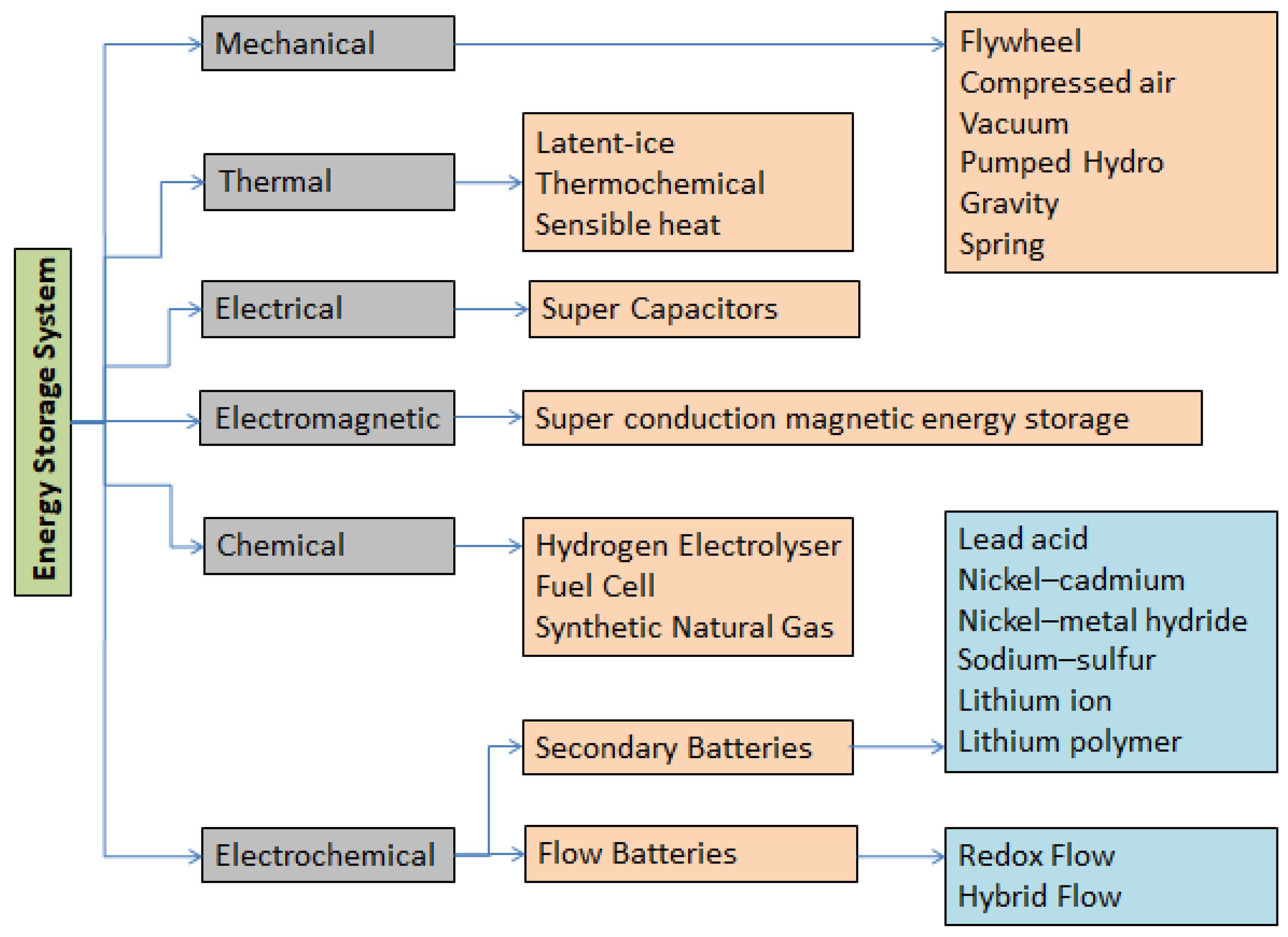

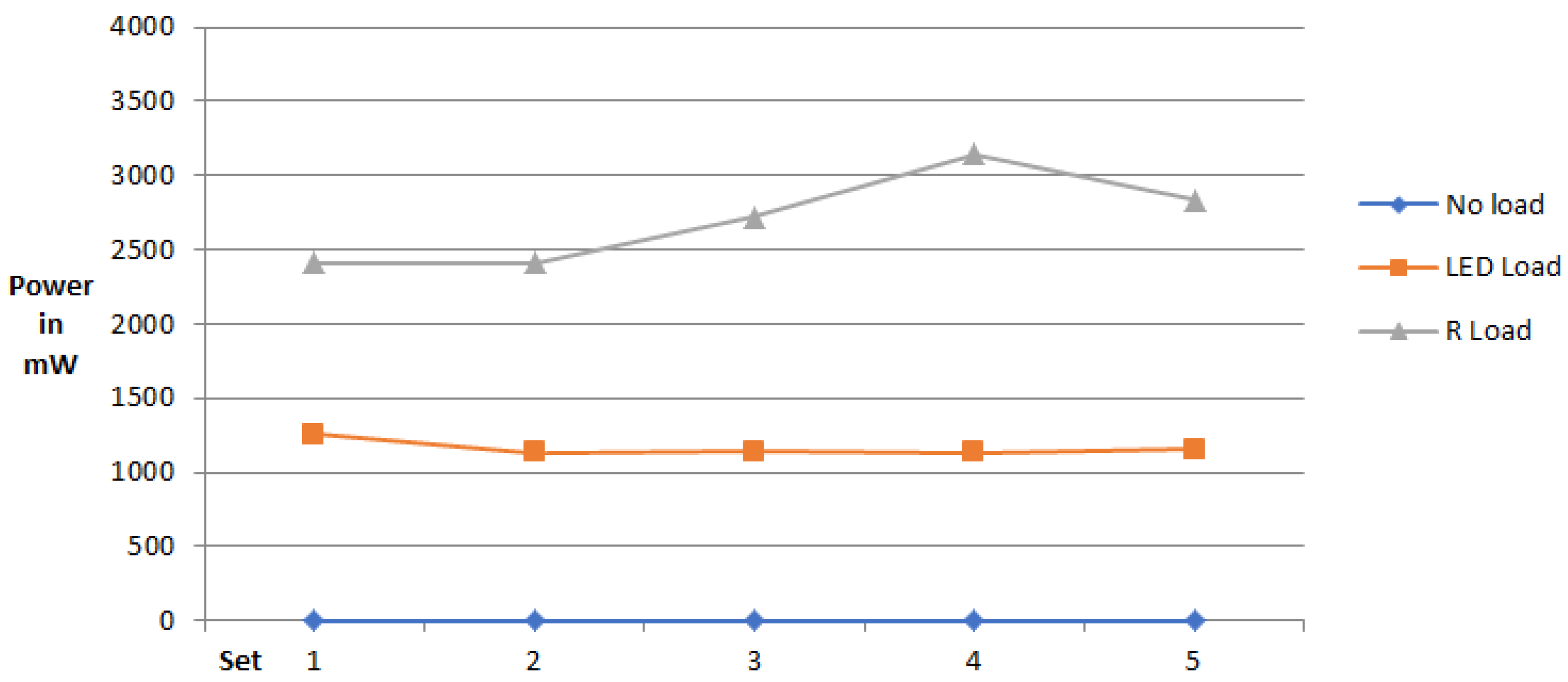

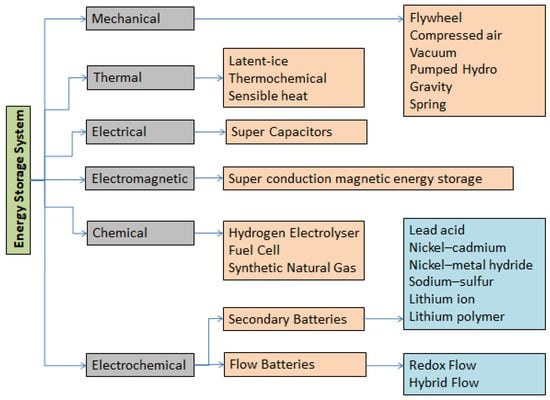

Figure 1 shows the types of energy storage systems for different engineering disciplines. Selection of energy storage system depends on the environment, lateral area, climatic condition, initial and running cost, system maintenance, lifetime, legal issue, and impact on the society [6].

Figure 1.

Energy storage system.

An energy storage system stores energy during periods of low demand or low production cost. It supplies energy during periods of high demand or no generation [7].

2.1.2. Comparison of Energy Storage Systems

The detailed comparative study of several energy storage technologies, including thermal, electrical, chemical, mechanical, electromagnetic, and electrochemical systems, is shown in Table 1. The backup duration of every system in Table 1 serves as the basic parameter for the comparison. The majority of energy storage systems fall into the medium-term (a few minutes to hours) category. High investment costs and several legal requirements are necessary for long-term backup storage systems [8,9].

Table 1.

Comparison of different energy storage systems.

The installed capacity and lifespan of different energy storage systems are also shown in Table 1. The capacity describes the existing maximum installation capacity of various energy storage systems. The life span outlines the efficient working duration of the systems [10].

2.2. Gravity Energy Storage System

An energy storage system using gravitational force is a type of mechanical system in which mass movement takes place against the gravitational force during energy storage. When it moves downward due to gravity, the potential energy is converted into mechanical rotation, which can be converted into electrical energy [11,12].

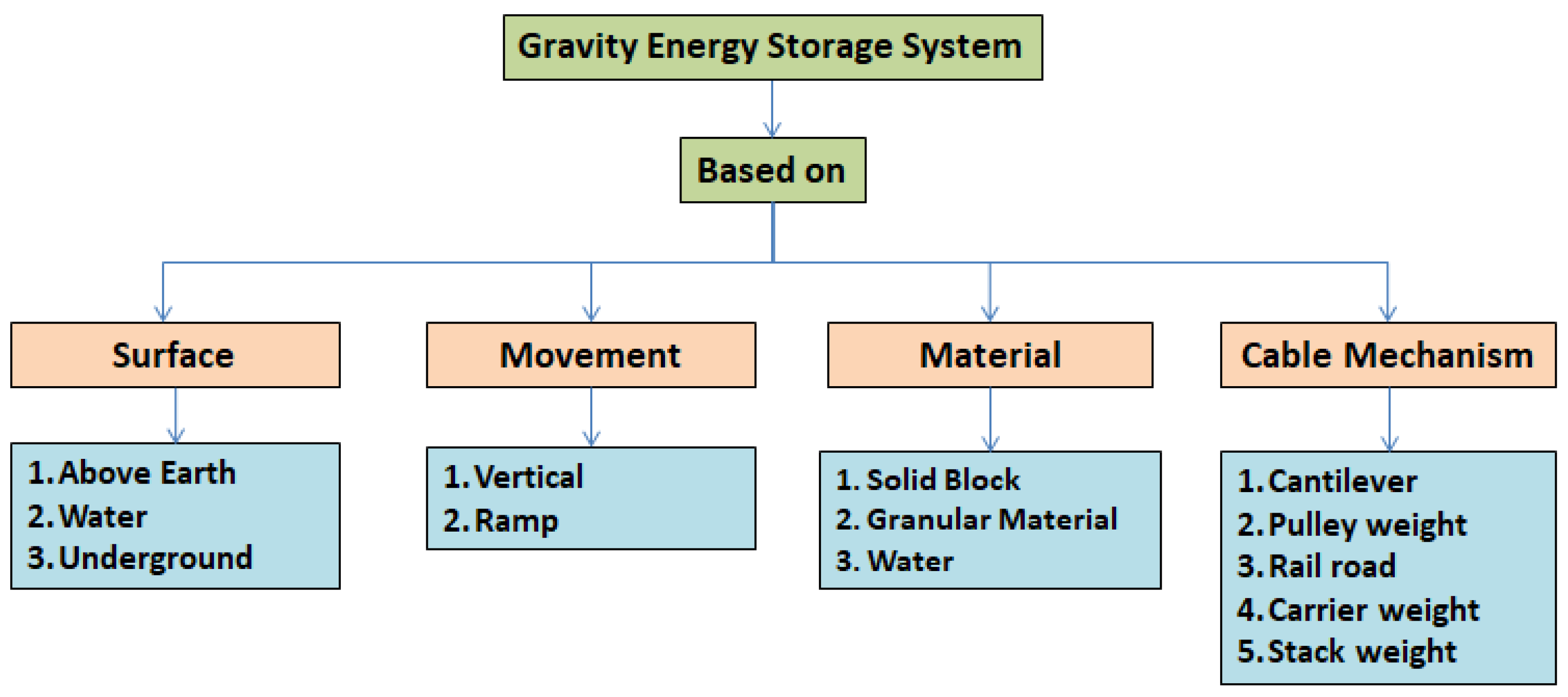

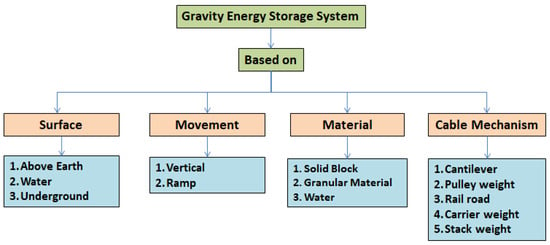

Types of Gravity Energy Storage System

The classification of gravity-based energy storage systems is shown in Figure 2. The classification is based on multiple states, including the surface, movement, material, and cable mechanism. The system may have a motor generator unit for energy conversion or another physical conversion system [13].

Figure 2.

Types of gravity energy storage system.

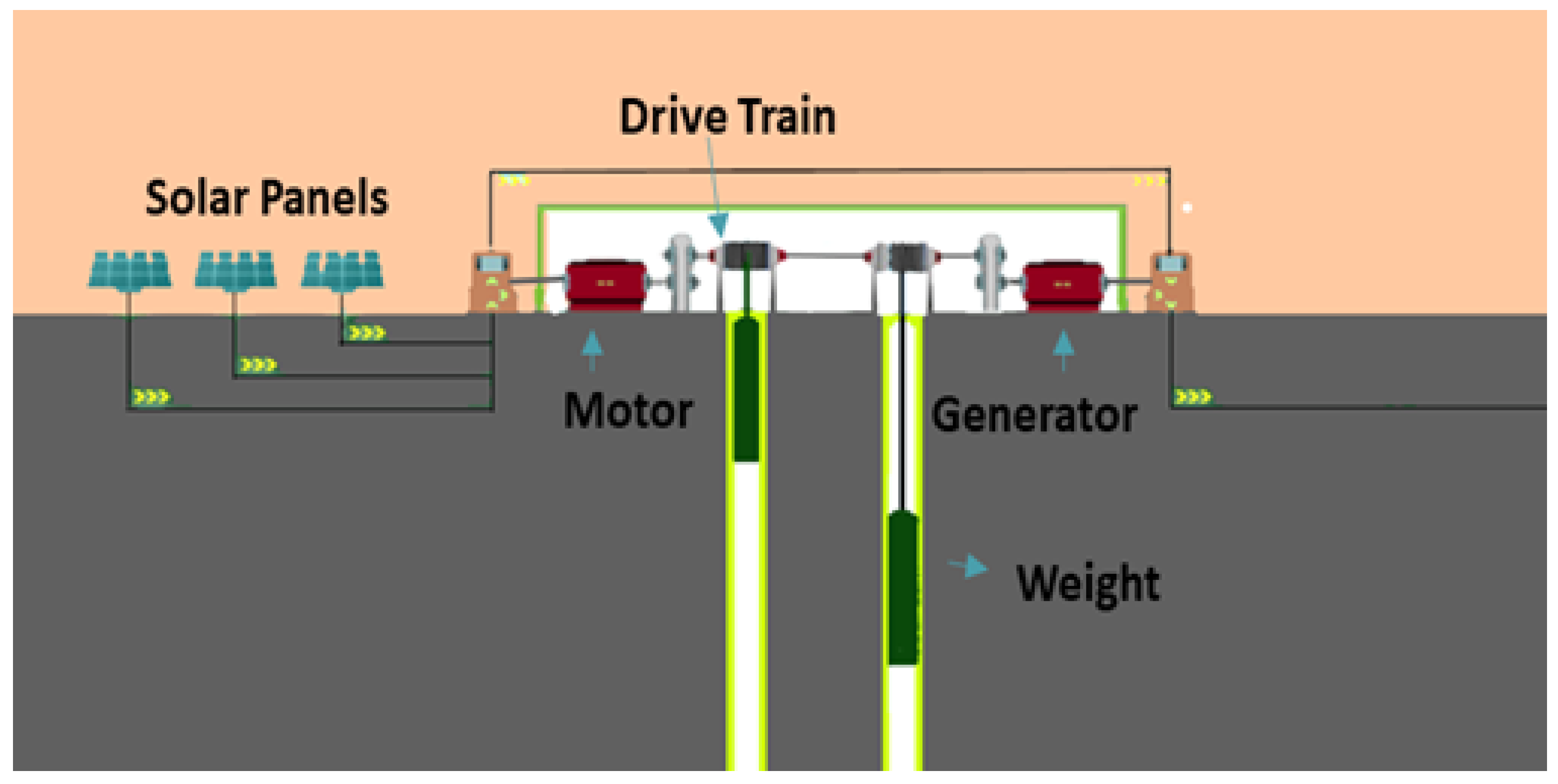

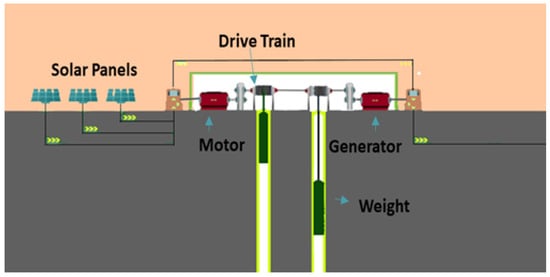

2.3. Proposed Gravity Energy Storage System

2.3.1. Block Diagram of the Proposed Gravity Energy Storage System

The conceptual model of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system is shown in Figure 3. The proposed system is hoisted underground, consisting of steel and a stack weight cable mechanism moving vertically to generate potential energy. The solar panel produces electrical energy, and it is given to the load during normal operation [14]. If excess energy is available, it is transferred to the motor in order to raise the stack weight from the bottom to the top surface. With the aid of a generator connected to the drive train system, the potential energy is transformed into electrical power when the stack weight is released due to gravity [15,16].

Figure 3.

Conceptual model of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system.

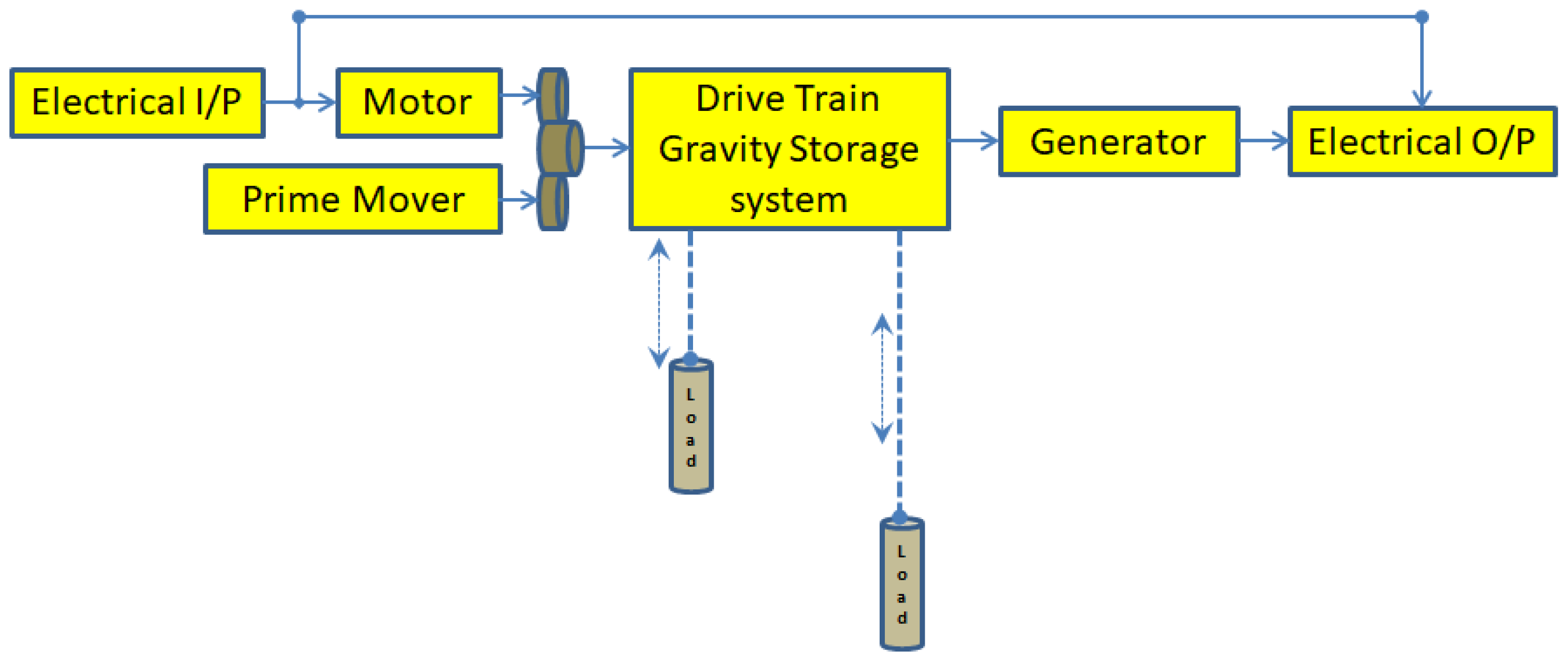

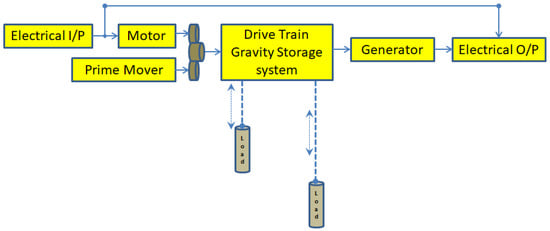

The block diagram of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system is shown in Figure 4. During normal operation, the electrical energy from any renewable or electrical power generator is given to the electrical load directly. When there is surplus energy in the electrical generation, that energy is supplied to the electrical motor to create rotational torque at the drive train system. In the drive train system, the stack weight load is moved up to store the potential energy. When the stack weight is released, due to gravity, it moves downwards, which produces kinetic energy. The stored potential energy is converted into kinetic energy in the load shaft. The generator coupled to the load shaft generates electrical energy to satisfy the demand. The storing and discharging process can be activated by the drive train model. Any mechanical rotational motion is available as input, which can be given to the drive train system as a prime mover.

Figure 4.

Block diagram of gravity energy storage system.

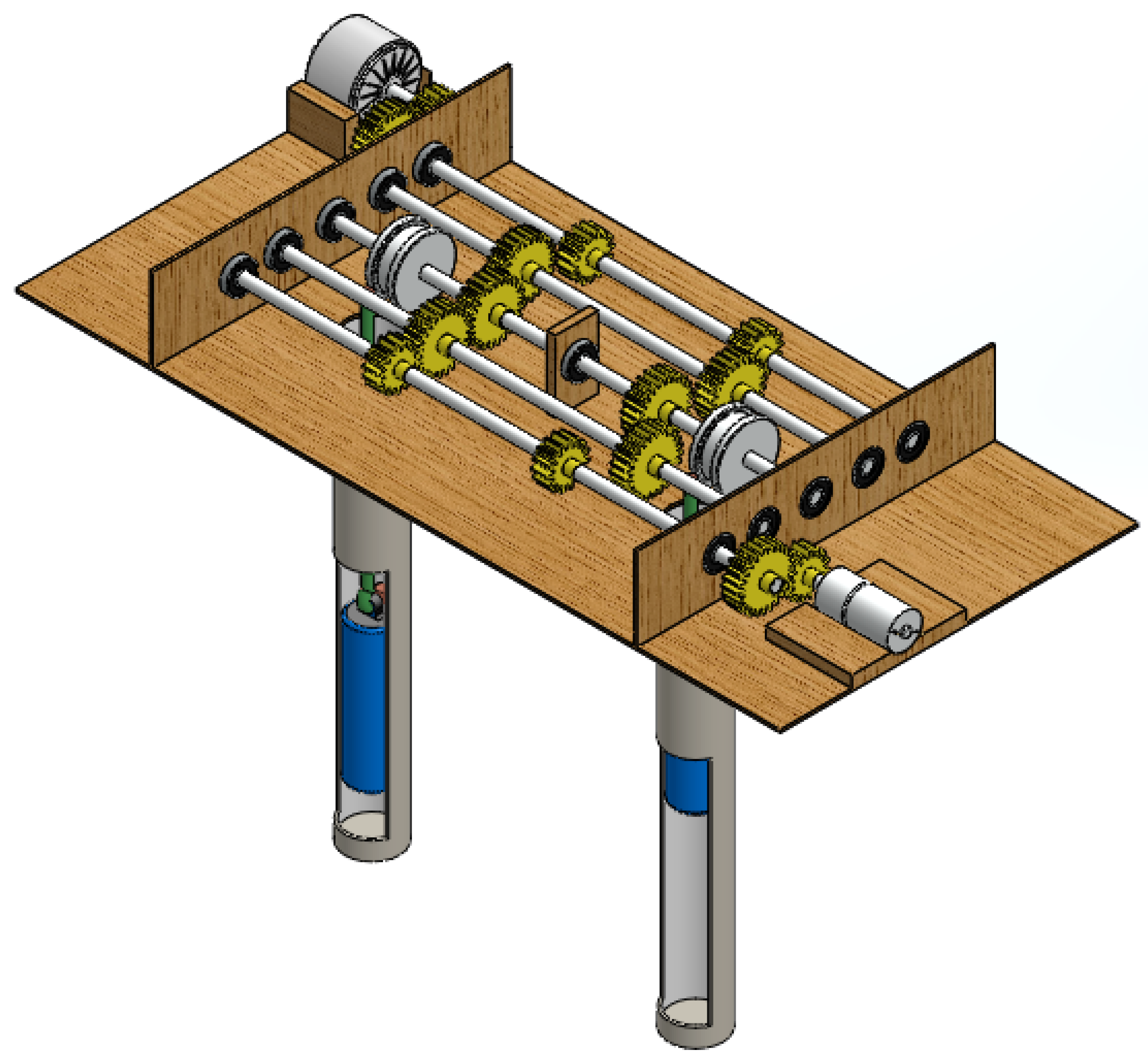

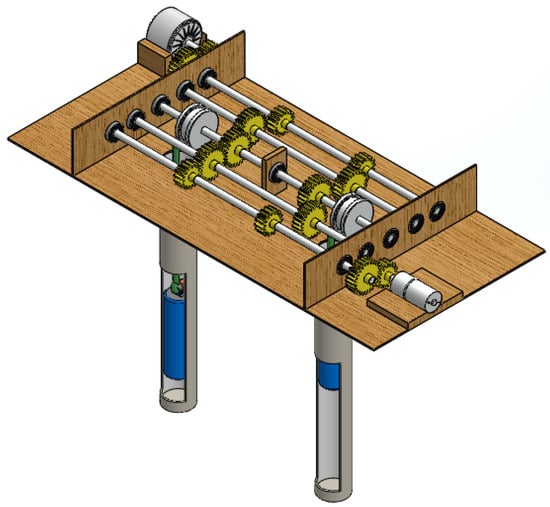

2.3.2. CAD Model

The CAD model of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system was designed using SolidWorks 2022 software, as shown in Figure 5. The simulation provides motion analysis, accurate modeling, integration, and selection of material. It helps to improve the quality of design and effective mechanical arrangement to increase system efficiency. See Supplementary Materials.

Figure 5.

SolidWorks model of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system.

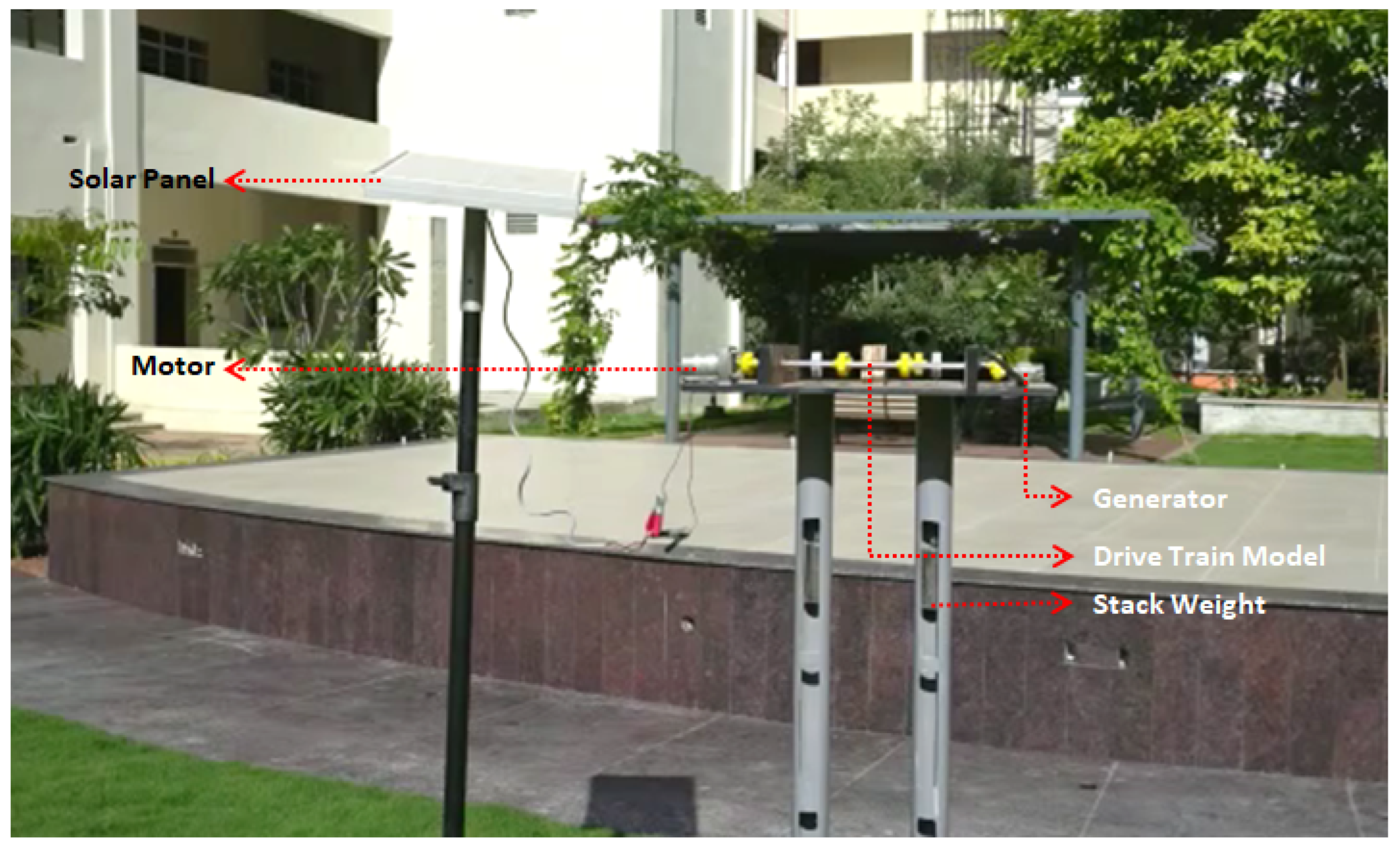

2.4. Experimental Setup of the Proposed Gravity-Based Energy Storage System

2.4.1. Experimental Setup of the Proposed System

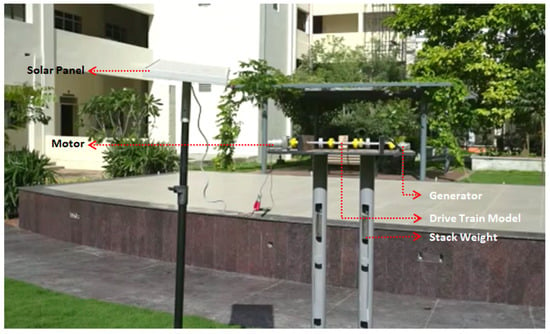

The experimental setup of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system is shown in Figure 6. Two steel stack weights, load 1 and load 2, are placed in a hollow cylindrical tube beneath the drive train system. The solar panel output is given to the motor to rotate the pulley through the gear arrangements, which pulls the load stack upward [17]. When the stack weight moves down due to gravity, the LED load connected to the generator will glow [18,19]. See Supplementary Materials.

Figure 6.

Experimental setup of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system.

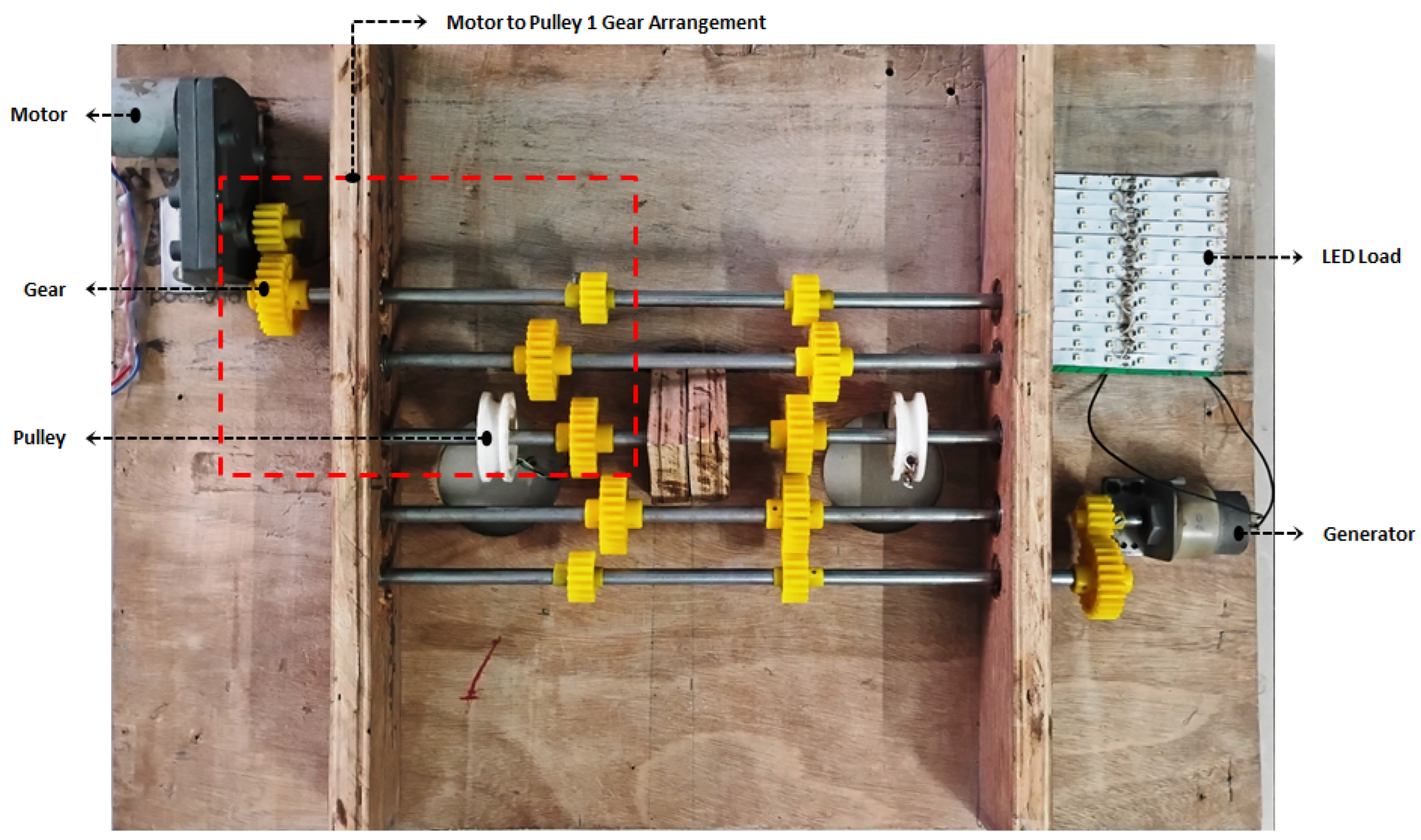

2.4.2. Mechanical Setup and Drive-Train Assembly

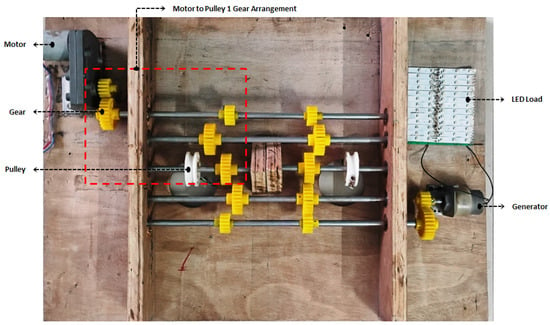

The drive train model of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system is shown in Figure 7. The square gear motor drives the shaft through the first set of gears; the second and third sets of gears drive the pulley, which lifts the stack weight load. The gear adjustments can be made manually from the motor to the load 1 or 2 stack, or from the load 1 or 2 stack to the generator [20].

Figure 7.

Drive train assembly of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system.

2.4.3. Golden Ratio

It is a ratio between two terms, a and b, and the ratio is 1:1.618. Mathematically expressed as ; the term series has been indicated by Pingala (200–400 BC), Fibonacci (1170–1240 AD), and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519 BC). The golden ratio is a self-replicating number, which can be identified in nature, like trees, branches, flowers, shells, sea waves, etc. Most natural things and evolutions follow this ratio [21,22]. Materials with the golden ratio have a longer lifetime and good efficiency when compared to normal values. The golden ratio concept (1:1.618) is incorporated in the drive train model arrangement for better performance.

Ratio of the diameter of toothed wheels:

Ratio of the number of toothed wheels:

Shaft Length = 34 cm

Stack Weight = 1 kg

Bore Length = 1 m

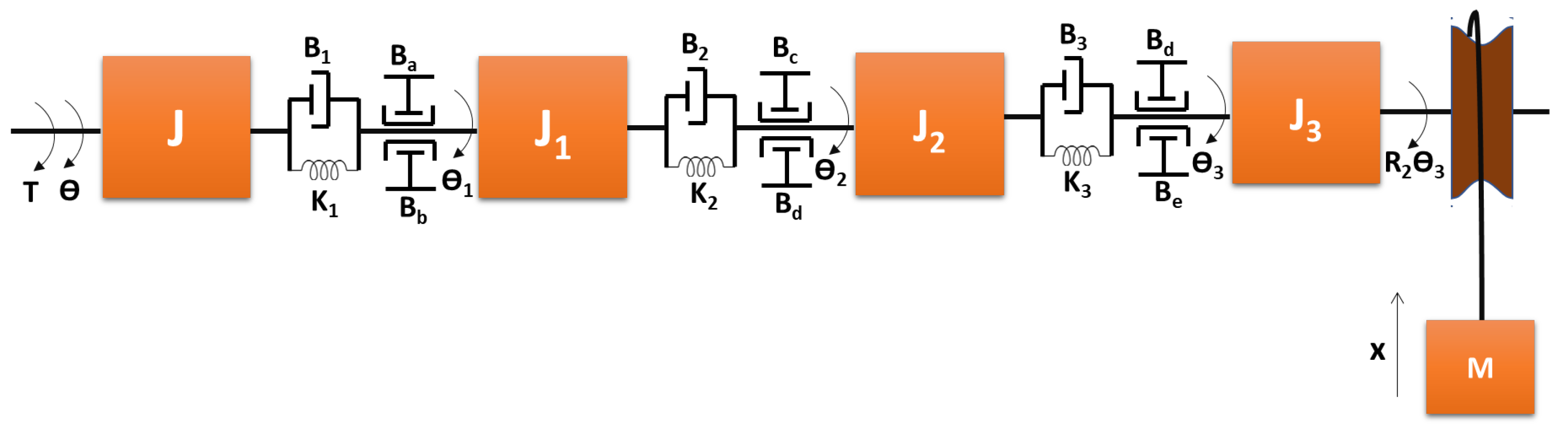

2.4.4. Transfer Function Model

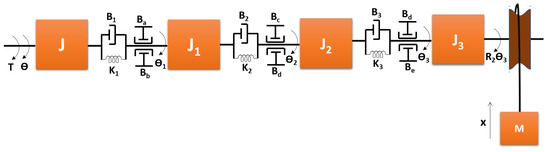

The energy conversion from electrical to mechanical systems can be theoretically observed with the help of a control system transfer function model. The dotted box in Figure 7 indicates the gear arrangement from motor to pulley 1 [23]. The electromechanical transfer function model of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system is shown in Figure 8. The motor rotational torque is taken as input; the stack weight vertical movement is taken as output. The shaft, bearings, gear arrangements, and pulley are indicated as rotational mass, rotational spring, and dashpot, respectively, as indicated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Transfer function model of the proposed system.

Similarly, the output equation from stack load movement to the generator is the inverse of Equation (1). With the help of the control system transfer function of the mechanical gear arrangement system, the torque and speed changes in each gear stage and the performance of the system with the influence of gear ratio can be identified. The overall working and behavior of the system is analyzed for a better understanding of system operation.

2.4.5. Hardware Specification

The hardware components and specifications of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system are shown in Table 2. The experimental setup is shown in Figure 6 and the mechanical connection is illustrated in Figure 7.

Table 2.

Hardware specification of the proposed gravity energy storage system.

The primary measurement indicators are solar irradiance to solar panel, motor input voltage and current, rotational speed of shaft, drive train torque, gravitational load displacement, and generator electrical output. These quantities are monitored using calibrated sensors integrated into the mechanical and electromechanical subsystems.

The variable boundaries are identified based on both hardware limitations and operating constraints. The boundaries are the gear ratio of the drive train assembly, the allowable stack weight of the gravity load, the durability of the wire and pulley mechanism, maximum lifting height, torque and speed limits of the motor, and the generator loading condition.

These key control variables, indicators, and boundaries define the operating domain for the transfer-function model and the mathematical analysis. The simulation parameters reflect the safe physical conditions. The specification of these indicators ensures the system’s operation.

2.4.6. Mathematical Analysis

Torque available at the motor shaft:

The torque needed to lift 1 kg of mass against gravity is given by:

Torque available at the load shaft with gear arrangement:

Since the available torque exceeds the required torque:

Torque available at the generator from stored gravity energy:

Power available at the output shaft:

Efficiency of the proposed system:

The torque developed at the motor shaft was initially calculated to assess the mechanical input to the system. The torque required to lift a 1 kg mass against gravity was determined as 9.8 Nm. The designed gear arrangement increases the torque available at the load shaft from 3.9366 Nm to 10.041 Nm, which exceeds the required lifting torque, confirming that the system can effectively raise the load. When the stack load releases, the torque available at the load shaft is 7.6 Nm, which produces the electrical power of 45.56 W at a speed of 60 rpm. The theoretical efficiency of the system is 78.12% (19), indicating that the proposed gravity energy storage can efficiently convert stored gravitational potential energy into useful mechanical and electrical output with minimum losses, demonstrating its practical viability for energy storage applications.

3. Results

As per the manufacturer’s data sheet, the input torque produced by the motor shaft is 3.936 Nm. With the help of the drive train model, the torque is boosted to 10 Nm to lift a 1 kg stack weight to store energy in terms of gravitational potential. When the load is released, the stack weight moves downwards due to gravity and produces 7.2 Nm rotational torque at the load side of the drive train model. These data are recorded using a rotary shaft torque transducer. The measured torque value validates the effective mechanical power transfer within the prototype and offers a reliable performance benchmark for the gravity-based energy storage mechanism.

3.1. Input Characteristics—Motor

The renewable energy source utilized for the proposed experimental setup is a solar panel rated at 12 V and 50 W. This solar photovoltaic (PV) module converts incident solar radiation into electrical energy, which serves as the primary input power to the system. The generated DC power is directly supplied to the square gear motor, which acts as the prime mover in the mechanical subsystem.

The square gear motor converts electrical input energy into mechanical rotational energy, driving the connected load through its output shaft. To evaluate its performance under various loading conditions, the motor was tested with three distinct load cases:

- Without load (free-run condition);

- With single load stack;

- With two load stacks.

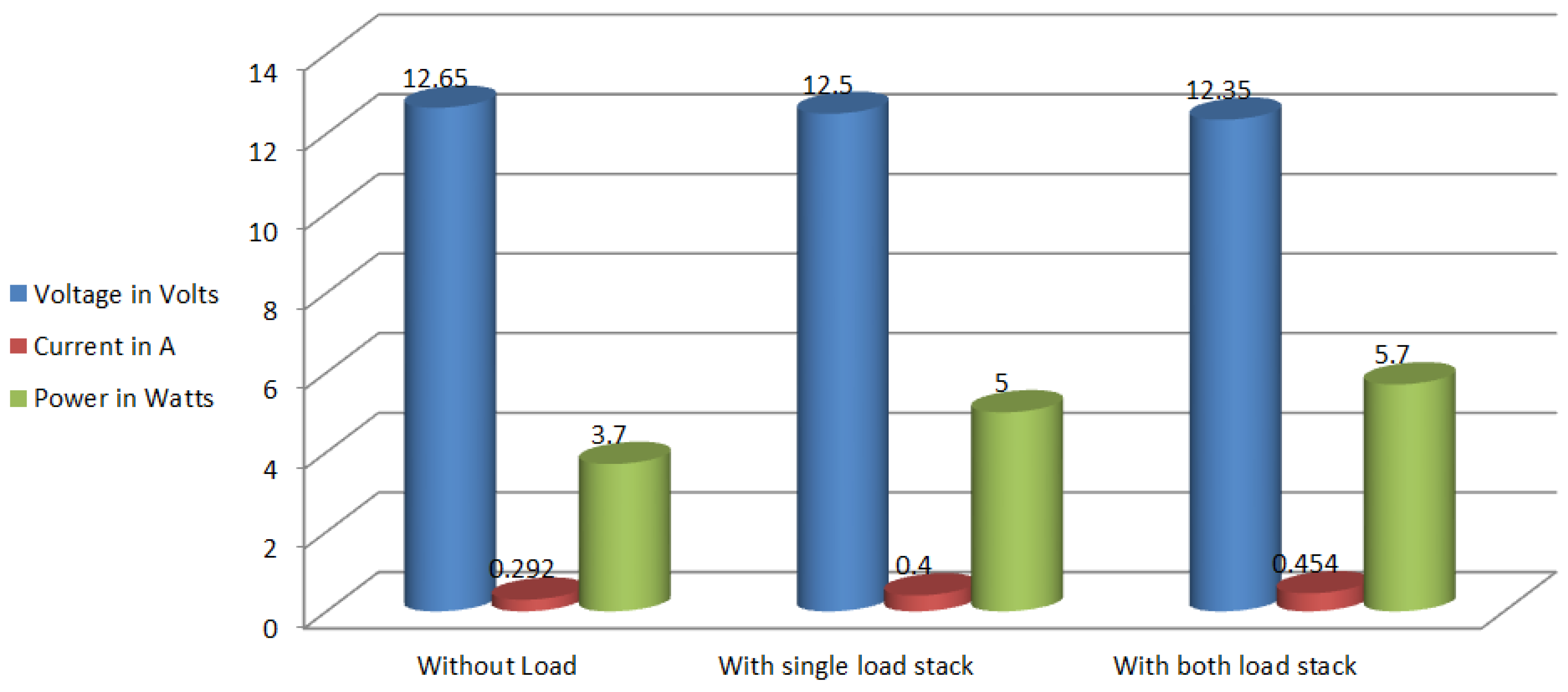

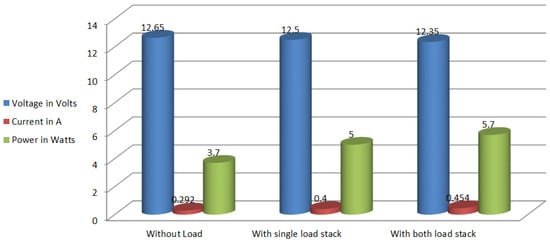

The corresponding electrical parameters, such as voltage, current, and power, were measured and recorded. The measured data are presented in Table 3, and the comparative results are illustrated graphically in Figure 9.

Table 3.

Square gear motor with variable load condition.

Figure 9.

Experimental results of square gear motor for different load condition.

From the recorded observations, it was found that under no-load conditions, the motor consumed a voltage of 12.65 V and a current of 292.49 mA, resulting in a power consumption of 3.7 W. This represents the minimum input power required to overcome internal frictional and magnetic losses.

When a single load stack was applied, the motor operated at 12.5 V and 400 mA, consuming 5.0 W of electrical power. This increase in current indicates a higher torque demand due to the external mechanical load.

With the application of two load stacks, the supply voltage slightly dropped to 12.35 V, and the current increased to 454.54 mA, resulting in a maximum input power of 5.7 W. This demonstrates that as the load increases, the current drawn and power consumption also increase to maintain the required torque output.

The variation trend confirms the direct proportionality between load and current consumption in DC motors. The voltage variation remains marginal, signifying stable supply performance from the solar source.

The bar chart shown in Figure 9 graphically represents this relationship among voltage, current, and power for different load conditions. The plot clearly illustrates that current and power rise with load increment, whereas voltage exhibits minimal fluctuation.

These results validate that the square gear motor performs efficiently under different mechanical load conditions when powered by a solar energy source. The observed characteristics indicate the suitability of this motor for renewable energy-based mechanical drive systems, maintaining stable operation with variable load.

3.2. Output Characteristics—Generator

The electrical motor of 12 V, 60 rpm is chosen as a generator for the proposed system to validate the system operation. The output characteristics (generated voltage, current, and power) with no load, LED load, and rheostat load are shown in Table 4. The results of single load stack and double load stack with respect to time taken are also tabulated with five sets of readings, and the average value is also indicated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Experimental results of gravity system for different load setup.

The experimental evaluation of the gravity-based energy storage system involved measuring the generator output under different load conditions, including no-load, LED load (12 V, 5 W, 72 LED strip), and resistive load (, 2 A). When a single stack load was released, the generator exhibited an average voltage of 9.29 V under no-load conditions, decreased to 7.84 V and 7.62 V under LED and resistive loads, respectively. The corresponding average currents were 7.84 mA and 7.62 mA for LED and resistive loads. The average power delivered was 1165 mW for the LED load and 2704.69 mW for the resistive load, indicating efficient energy conversion.

In case of double load release, the generator output showed a slight increase in average voltage for the loaded condition, reaching 8.21 V for the LED load and 8.06 V for the resistive load, with the average current of 152.59 mA and 333.72 mA, respectively. The corresponding average power outputs were 1251 mW for the LED load and 2691 mW for the resistive load.

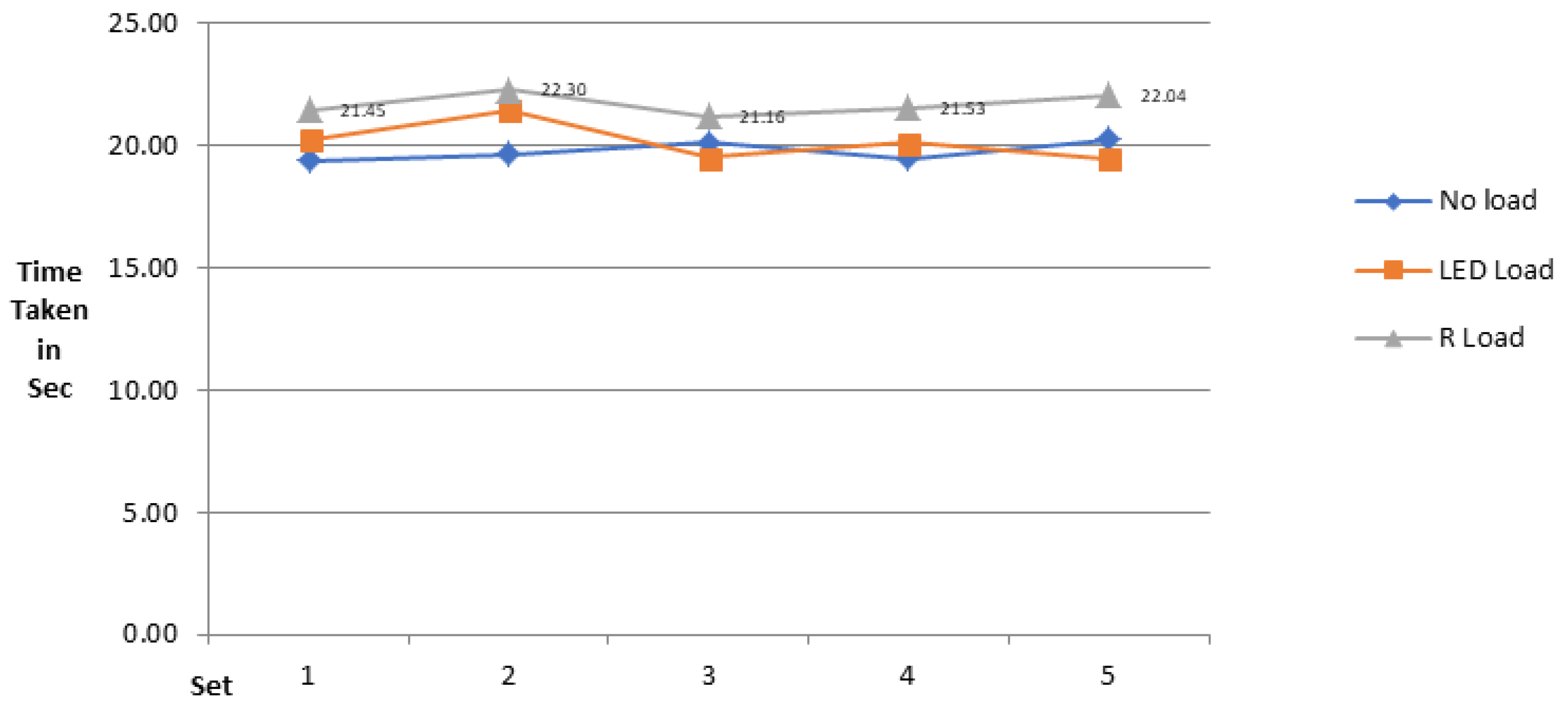

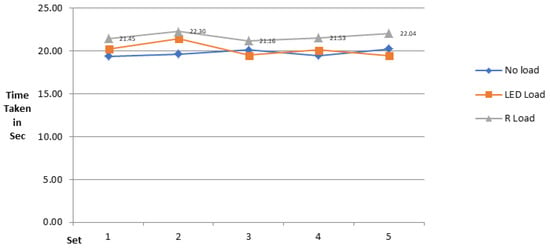

The graphical analysis of the experimental data provides a clear understanding of the gravity-based energy conversion system under different load conditions. Figure 10 illustrates the time duration required for the system to complete its operation for various load setups, indicating a nearly consistent performance with minimal variation across trials.

Figure 10.

Time taken for the gravity system with different load conditions.

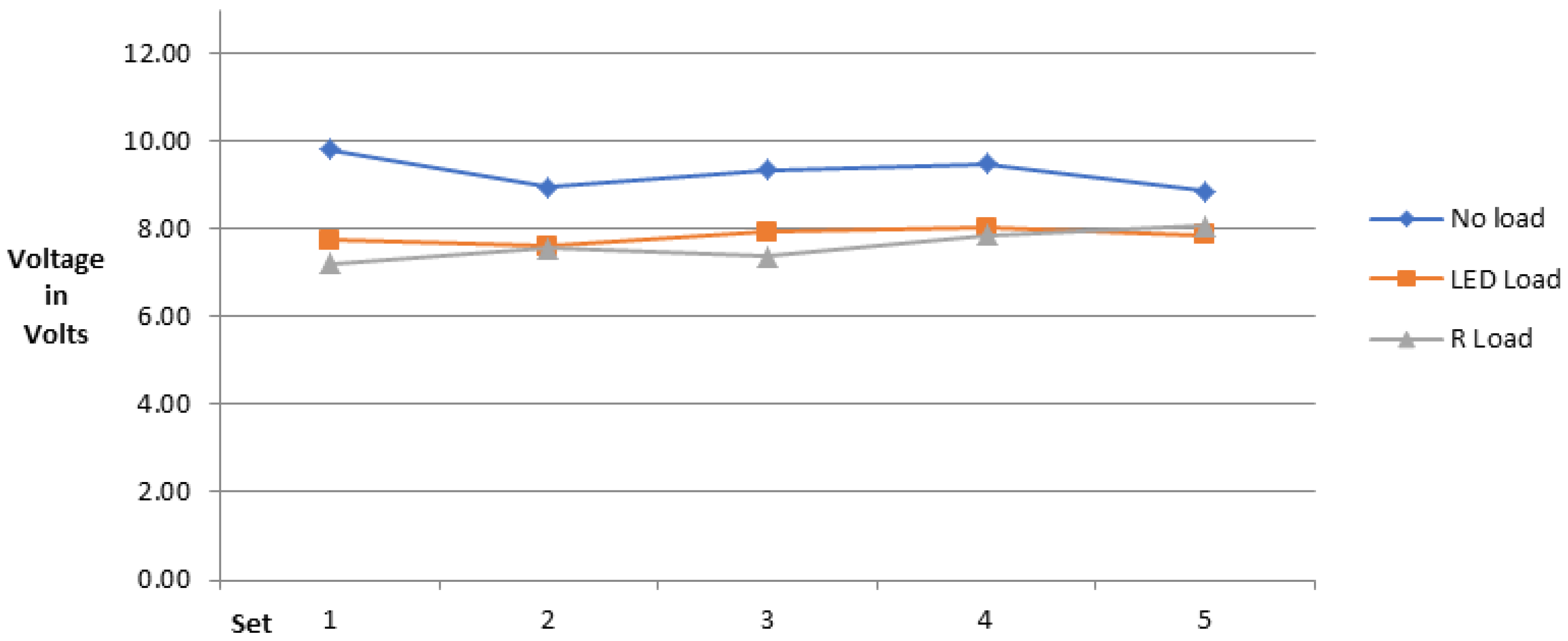

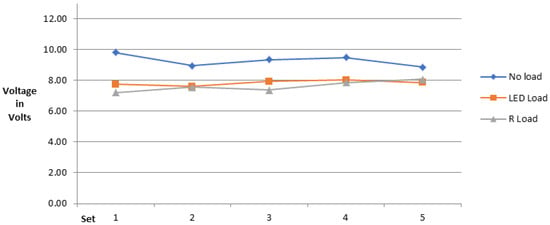

Figure 11 presents the generated output voltage under no-load, LED load, and resistive (R) load conditions. It is observed that the output voltage remains relatively stable, with a slight reduction under loaded conditions due to increased current demand.

Figure 11.

Generated output voltage for gravity system with different load conditions.

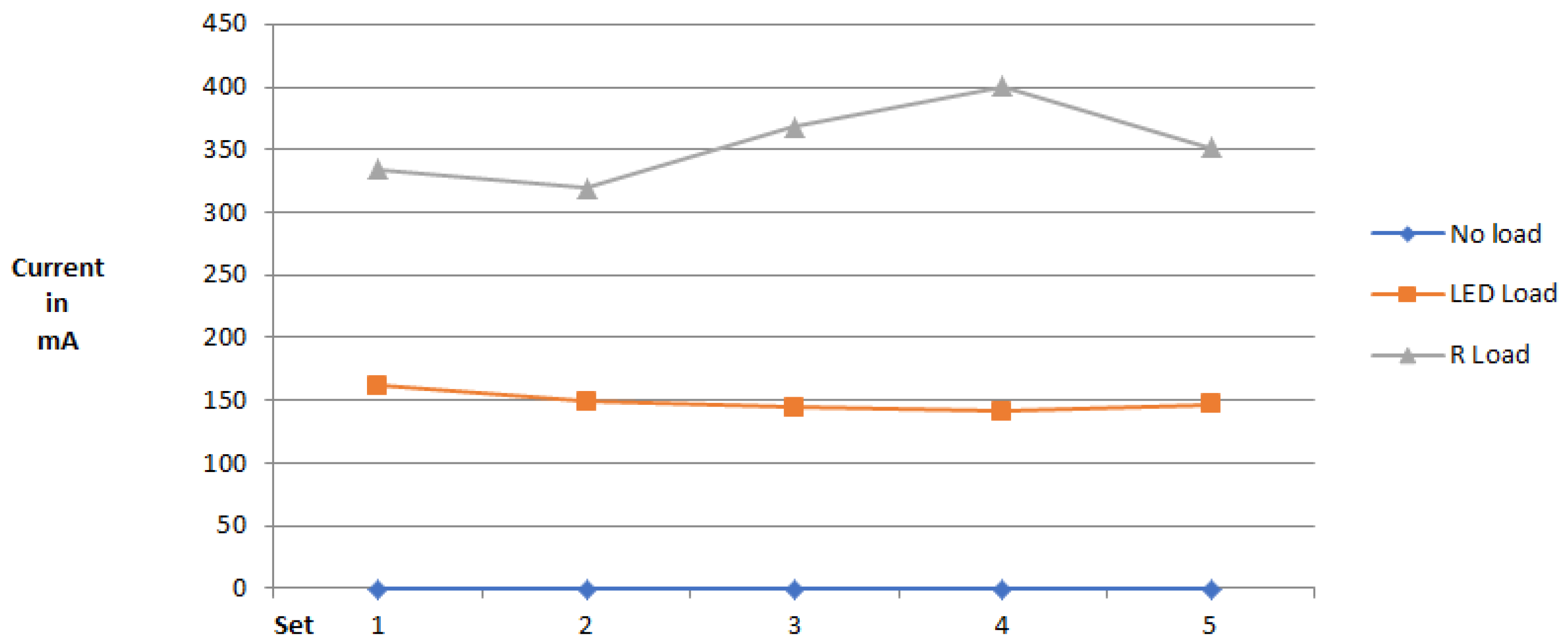

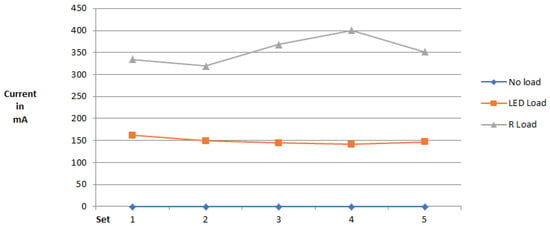

Similarly, Figure 12 depicts the generated output current for the same set of conditions. The resistive load exhibits the highest current output compared to the LED and no-load cases, validating the system’s ability to deliver greater electrical energy under higher load demands.

Figure 12.

Generated output current for the gravity system with different load conditions.

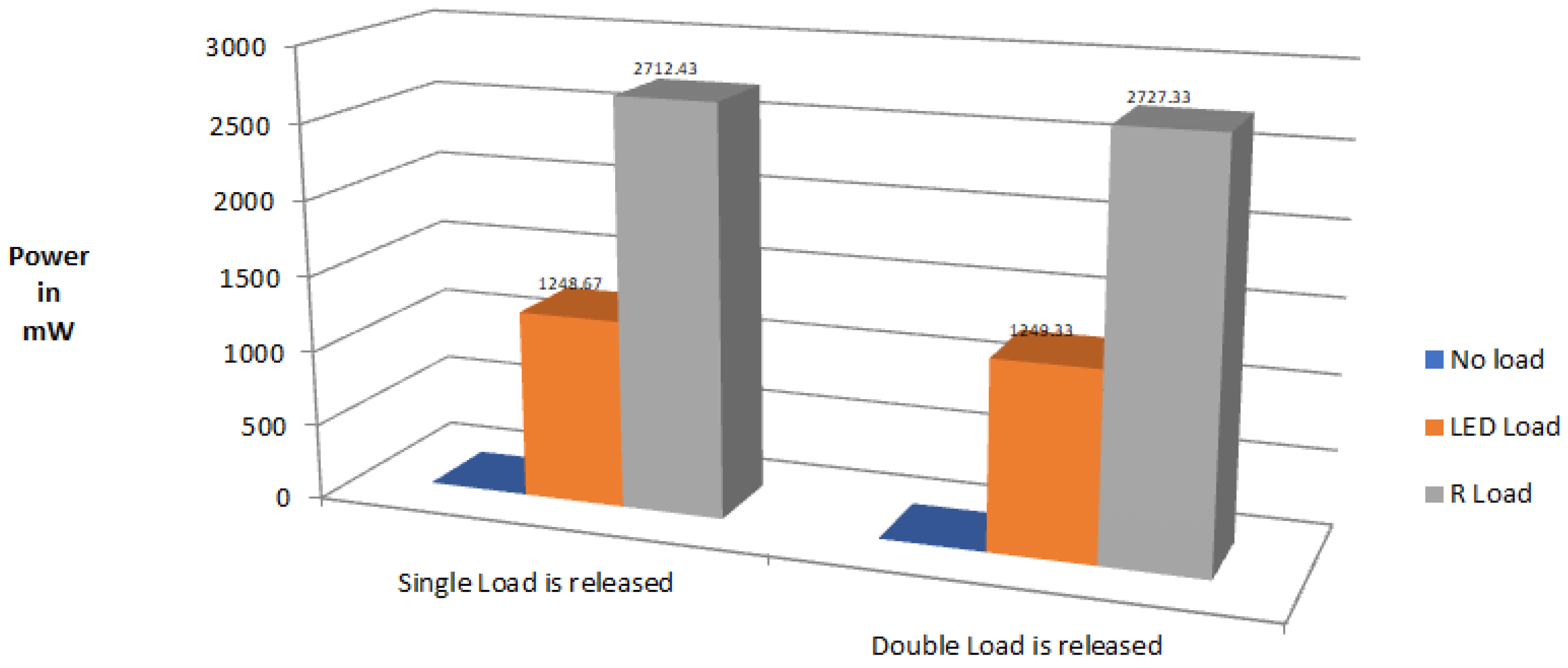

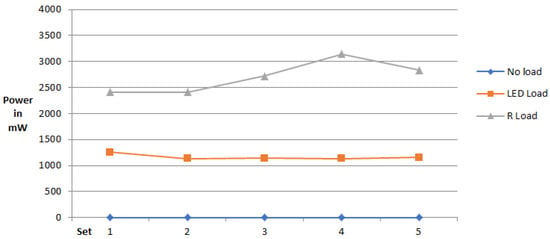

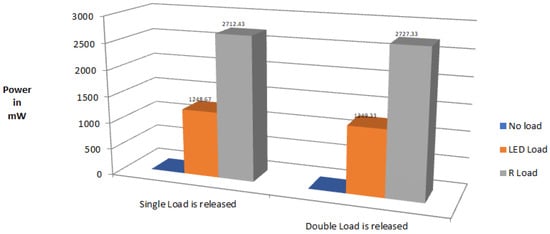

Figure 13 represents the corresponding power output variation across different sets, demonstrating that the resistive load condition produces the maximum power, followed by the LED load and no-load conditions.

Figure 13.

Generated output power for the gravity system with different load conditions.

Furthermore, Figure 14 compares the generated power when single- and double-load stacks are released. The results indicate a noticeable increase in power generation with double-stack release, confirming the direct relationship between the released gravitational potential energy and the resulting electrical output.

Figure 14.

Generated output power with different load conditions for the stack weight.

The results presented in Table 4 and the graphical representations in Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 collectively substantiate the successful conversion of stored gravitational potential energy into usable electrical energy. The consistency of the obtained data highlights the reliability and efficiency of the designed gravity-based energy harvesting system.

These results demonstrate that the system can reliably convert gravitational potential energy into electrical energy, with consistent power delivery across varying load conditions. The consistent power output highlights the scalability potential of the system for increased energy storage capacity.

3.3. Comparison Between Battery and Gravity Storage System

Table 5 illustrates the comparison of battery and gravity energy storage systems, and the pros and cons of gravity storage system parameters with the battery storage system are indicated [24,25,26].

Table 5.

Comparison of battery and gravity storage system.

In Table 5, the comparison between battery and gravity storage systems highlights their distinct characteristics. Batteries offer high energy density, fast response, and low maintenance, making them suitable for short-duration, high-power applications, but their lifespan is limited, and large-scale deployment is challenging. In contrast, gravity storage provides long operational life exceeding 50 years, scalable capacity, and renewable energy utilization, making it ideal for utility-scale integration and grid stability. Although gravity systems involve higher maintenance and complex construction, they offer low operating costs, a reasonable return on investment, and long-term sustainability, despite lower energy density and slower response.

3.4. Estimation of 1 KW Gravity System

The estimation of a 1 KW gravity storage system is shown in Table 6. Excluding land and construction cost, the investment is INR 235,690 for the gravity storage system and INR 210,000 for the battery storage system [27,28].

Table 6.

Estimation of the 1 kW gravity storage system.

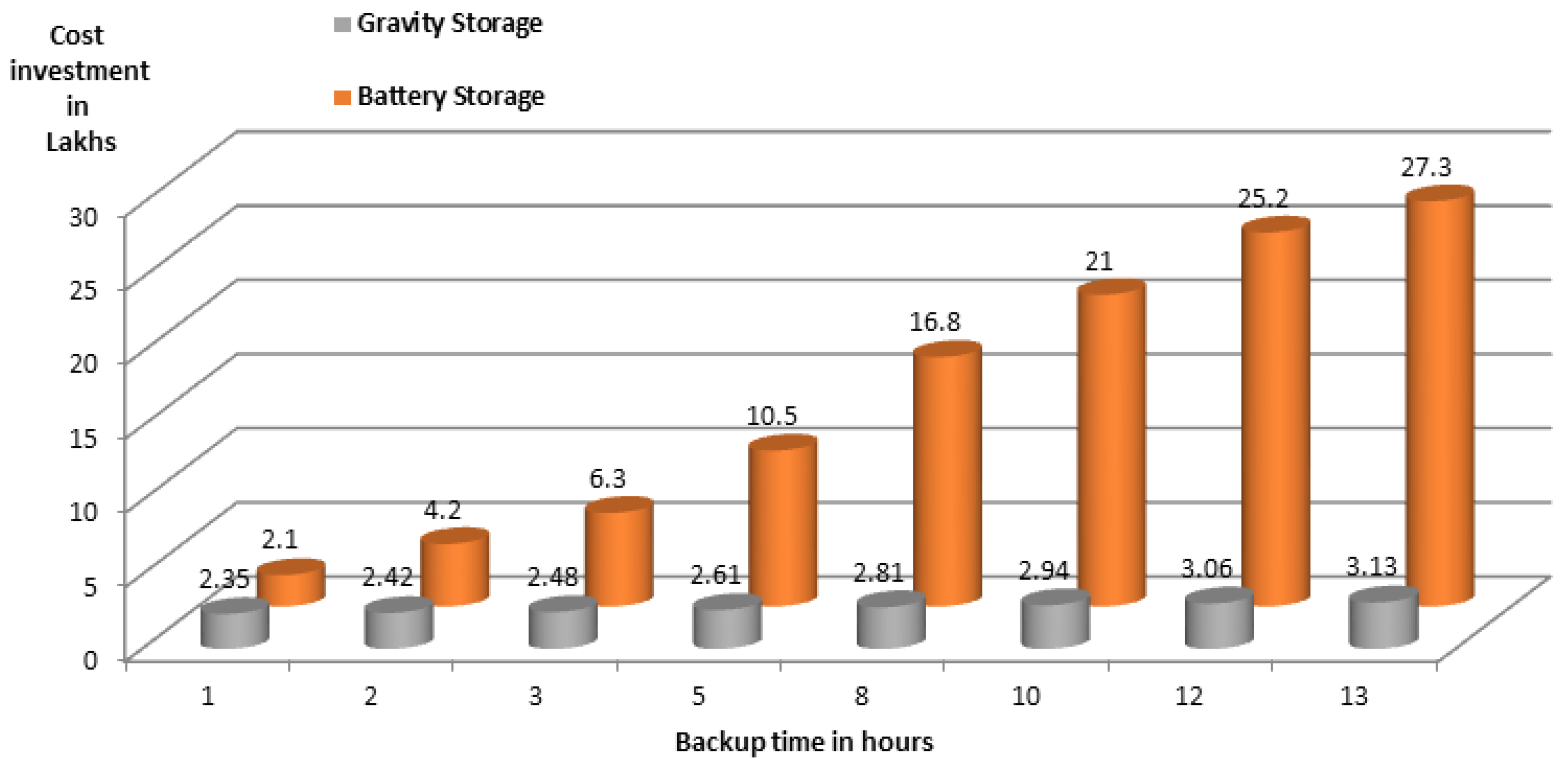

3.5. Scalability of Gravity Storage System

The scalability of a 1 KW battery and gravity storage system is tabulated in Table 7. The cost of a battery storage system increases when the backup time increases. But in a gravity storage system, the cost increases slightly with respect to backup time. When compared to a battery storage system, the gravity storage system is more efficient and economical [28,29].

Table 7.

Scalability of 1 kW battery and gravity storage system.

The graphical representation of a 1 kW gravity and battery storage system with respect to backup time is shown in Figure 15. The gravity storage system is almost flat while the battery storage system is linearly increasing with respect to backup time [30,31,32].

Figure 15.

Comparison of the 1 kW gravity/battery storage system with respect to time.

The gravity storage cost remains nearly constant across varying backup durations. In contrast, the cost of a battery storage system increases linearly. The results highlight gravity storage as a cost-effective and scalable solution for extended energy backup.

The comparison of the gravity and battery storage systems conveys meaningful scientific insights:

- Lifetime difference is intrinsic to economic comparison. In the gravity storage system, the lifetime exceeds 50 years with proper maintenance, but the battery system requires a whole replacement every 5 years.

- The raw cost data imply that the gravity system avoids very large battery replacements and influences long-term economics when compared to the battery system.

- The backup capacity of the battery system is multiple times that of the backup time; in the gravity system, the addition of stack weight is the only concern.

The experimental validation supports the feasibility of gravity storage as a practical alternative.

4. Conclusions

Energy storage is important for a sustainable future. Energy storage technology is essential for managing the energy source, supply, and demand. Also, it is integrating renewable and non-renewable energy for better electrical grid stability. The energy storage system can be decided based on environmental conditions, economic conditions (initial and running costs), space requirements, technical considerations, energy density, conversion response, and deployment. The gravity-based energy storage systems have high attention due to their efficient energy storage capacity. The experimental results confirm the practical output of 7.2 Nm from the gravity storage for the stack weight of 1 kg. The produced usable power supports the workability and feasibility of the proposed gravity-based energy storage system. The intrinsic lifetime advantage of the gravity system exceeds 5 decades, clearly indicating the long-lasting energy storage difference from the battery system. By establishing a validated framework, this present work provides a foundation for optimizing gravity energy storage systems and supports their potential deployment as reliable, low-carbon energy solutions. The initial investment of a gravity storage system is more when compared to other storage systems (battery); for small- and medium-scale utility levels, battery systems are more efficient because they are static, have high energy density, and have flexible deployment. For large-scale low-energy-density applications, gravity energy is the optimal solution due to its low operational cost, high durability, longer lifespan, low raw cost, and high scalability.

5. Discussion and Future Scope

The proposed gravity energy storage system, with experimental results, confirms the energy storage and conversion of gravitational force to electrical energy. Since this work introduces a novel energy storage system, the primary goal is to experimentally demonstrate the feasibility and workability of the system. Nevertheless, we have now strengthened the discussion to more explicitly link our experimental results to the theoretical framework, clarifying how the observations support or refine the proposed mechanism. This enhances the conceptual grounding of our study while highlighting the practical validation of the new system. This study contributes significantly to the gravity energy storage system and the drive train mechanical setup. However, several areas need advanced exploration, such as the following:

- Low-speed electrical generator design;

- Enhanced drive train methodologies;

- Environmental condition;

- Lock and hold mechanism in stack weight assembly;

- Enhancing energy security;

- Supporting technological advancement;

- Utility scale renewable integration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1yyf_0EBW2CkT6AUBt4d3PQeycqnJvf00/view?usp=sharing/s1 (accessed on 14 October 2025), Video S1: Gravity Based Energy Storage System Prototype.

Author Contributions

V.E. conceptualized the study, performed the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. S.P. supervised the research work, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and contributed to interpretation of results. A.M. and A.A. provided guidance on work methodology and experimental result. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank PSG College of Technology for providing research facilities and institutional support for carrying out this work. We are deeply grateful to late Raghul.A for his in valuable support in the early stage of this research. His contribution and dedication to this field will be remembered.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GESS | Gravity Energy Storage System |

| LED | Light Emitting Diode |

| CAD | Computer Aided Design |

| mA | milli Ampere |

| mW | milli Watts |

| KW | Kilo Watts |

| MW | Mega Watts |

| GW | Giga Watts |

| KWh | Kilo watt Hour |

| R Load | Resistive Load |

References

- Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Shi, C.; Zhao, C. A Review of Gravity Energy Storage. Energies 2025, 18, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, V.; P, S.; A, R.; R, P.; C, I.; E, P. A Review of Electrical Energy Storage System. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, 17–18 March 2023; pp. 1940–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Lu, Z.; Chen, W.; Han, M.; Zhao, G.; Wang, X.; Deng, Z. Solid Gravity Energy Storage: A Review. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Lata, P.; Gupta, A. Gravity Based Energy Storage System: A Technological Review. Int. J. Emerg. Trends Eng. Res. 2020, 8, 6406–6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyke, A. The Fall and Rise of Gravity Storage Technologies. Joule 2019, 3, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekka, A.; Ghaffari, R.; Venkatesh, B.; Wu, B. A Survey on Energy Storage Technologies in Power Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference (EPEC), London, ON, Canada, 26–28 October 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Storage in the UK: An Overview, 2nd ed.; Renewable Energy Association: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.r-e-a.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Energy-Storage-FINAL6.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Chaturvedi, D.K.; Yadav, S.; Srivastava, T.; Kumari, T. Electricity Storage System: A Gravity Battery. In Proceedings of the Fourth World Conference on Smart Trends in Systems, Security and Sustainability (WorldS4), London, UK, 27–28 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D.; Zakeri, B.; Jurasz, J.; Tong, W.; Dąbek, P.B.; Brandão, R.; Patro, E.R.; Đurin, B.; Filho, W.L.; Wada, Y.; et al. Underground Gravity Energy Storage: A Solution for Long-Term Energy Storage. Energies 2023, 16, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Mandal, K.K.; Datta, A. Solar PV Driven Hybrid Gravity Power Module—Vanadium Redox Flow Battery Energy Storage for an Energy Efficient Multi-Storied Building. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 18477–18494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S. Weights-Based Gravity Energy Storage Looks to Scale Up. Engineering 2022, 14, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morstyn, T.; Chilcott, M.; McCulloch, M.D. Gravity Energy Storage with Suspended Weights for Abandoned Mine Shafts. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, C.D.; Kamper, M.J. Capability Study of Dry Gravity Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2019, 23, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowoto, O.K.; Emenuvwe, O.P.; Azadani, M.N. Gravitricity Based on Solar and Gravity Energy Storage for Residential Applications. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2021, 12, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Lu, Z.; Han, M.; Zhao, H.; Xu, G.; Zhao, G.; Hunt, J. Inertial Characteristics of Gravity Energy Storage Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 6–9 December 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrada, A.; Loudiyi, K.; Garde, R. Dynamic Modeling of Gravity Energy Storage Coupled with a PV Energy Plant. Energy 2017, 134, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushiri, T.; Jirivengwa, M.; Mbohwa, C. Design of a Hoisting System for a Small Scale Mine. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 8, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, A.C.; Ghodeswar, P.; Khot, T.; Gawande, B.; Sohel, M.; Wagh, S. Design and Fabrication of Gravity Based Energy Storage System. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 598–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Shahmoradi-Moghadam, H.; Schonberger, J.O.; Schegner, P. Algorithm and Optimization Model for Energy Storage Using Vertically Stacked Blocks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 217688–217700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugyema, M.; Kamper, M.J.; Wang, R.-J.; Sebitosi, B.A. Performance and Cost Comparison of Drive Technologies for a Linear Electric Machine Gravity Energy Storage System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 46953–46966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, C. The Golden Ratio: Real-Life Math. Math. Teach. Middle Sch. 2011, 16, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, N. Another Appearance of the Golden Ratio. Math. Gaz. 2024, 108, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, I.; Halevi, Y. Transfer Function Modeling of a Flexible Gear Train. In Proceedings of the ASME International Design Engineering Technical Conferences, Volume 3: Dynamic Systems and Controls, Torino (Turin), Italy, 4–6 January 2006; pp. 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hilfi, L.M.A.; Morris, S.; Fathima, A.P.; Ezra, M. Investigation of Potential Benefits and Challenges of Using Gravity Energy Storage in Residential Sectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE PECCON, Chennai, India, 5–6 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarini, A.; Longo, M.; Brenna, M.; Zaninelli, D. Battery Electric Storage Systems: Advances, Challenges, and Market Trends. Energies 2023, 16, 7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bremner, S.; Menictas, C.; Kay, M. Battery Energy Storage System Size Determination in Renewable Energy Systems: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, B. Day-Ahead Scheduling of a Gravity Energy Storage System Considering the Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrada, A.; Loudiyi, K.; Zorkani, I. System Design and Economic Performance of Gravity Energy Storage. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrada, A.; Emrani, A.; Ameur, A. Life-Cycle Assessment of Gravity Energy Storage Systems for Large-Scale Application. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farakhor, A.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Fang, H. Scalable Optimal Power Management for Large-Scale Battery Energy Storage Systems. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 2024, 10, 5002–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.D.; Zakeri, B.; Falchetta, G.; Nascimento, A.; Wada, Y.; Riahi, K. Mountain Gravity Energy Storage: A New Solution for Closing the Gap Between Existing Short- and Long-Term Storage Technologies. Energy 2020, 190, 116419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrada, A.; Loudiyi, K.; Zorkani, I. Sizing and Economic Analysis of Gravity Storage. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2016, 8, 024101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).