Abstract

In the manufacturing of iron core for high-power transformers, a cutting stock problem arises where large-width silicon steel coils must be cut into narrower coils, known as strips. Typically, the required length of each strip far exceeds that of a single coil. Therefore, the problem necessitates additional consideration of how to split the strips and arrange them on the large coils, with the goal of minimizing the total number of strips. In this paper, we propose a discrete artificial bee colony algorithm to address this problem. The algorithm replaces the stochastic roulette wheel with biased selection in the onlooker bee phase and introduces partially mapped crossover in both the onlooker and scout bee phases. These enhancements facilitate more effective utilization of information from high-quality solutions, thereby improving the algorithm’s stability and its capacity to obtain higher-quality results. Experimental results show that compared to existing methods reported in the literature, the proposed approach reduces the total number of strips by an average of over 3.9% and 7.6% for Set 2 and Set 3, respectively, while also exhibiting a faster convergence rate than other competitive algorithms.

1. Introduction

The cutting stock problem (CSP), also referred to as a nesting problem [1], is an NP-complete optimization task [2] that involves cutting a set of small items from large stocks. The problem is subject to geometric constraints requiring that all items lie entirely within the stock and do not overlap. The CSP has widespread industrial applications, including in the sheet metal [3], furniture [4,5], paper sheet [6], and glass industries [7]. A common objective is to minimize waste or production time, thereby generating significant economic benefits for manufacturers.

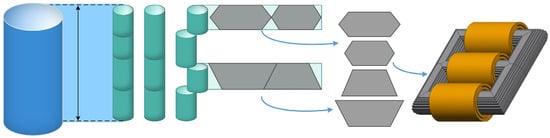

This paper addresses a two-dimensional cutting stock problem (2DCSP) arising in the manufacturing of iron cores of high-power transformers. Figure 1 illustrates the iron core manufacturing process. Initially, a shearing machine cuts large-width silicon steel coils into strips. These strips are subsequently processed by another machine that cuts them into smaller pieces, which are then stacked—either manually or automatically—to form the complete iron core.

Figure 1.

The production process of the iron core cutting the coils into strips, cutting the strips into pieces, and stacking the pieces.

The problem studied here focuses on the first stage: cutting heterogeneous coils into strips of varying widths, with the goal of minimizing the total number of strips. The required length of a strip equals the total length of all the pieces sharing the same width, which typically far exceeds the length of an individual coil. Consequently, the problem entails determining how to divide the strip and arrange the sub-strips on the multiple coils. The divisibility of the item makes it distinct from other cutting stock problems.

Several algorithms are proposed for the 2DCSP problem and evaluated on over a hundred instances [8]. The experimental results verified the effectiveness and practicality of the approaches. However, the standard deviation of the results indicates that the stability of the outcomes is compromised when solving larger-scale instances. This observed inconsistency motivates our work to develop an approach capable of delivering more reliable and higher-performing outcomes.

In this paper, a discrete artificial bee colony (DABC) algorithm is proposed to solve the 2DCSP. The artificial bee colony simulates the foraging behavior of a real honey bee colony [9] and is known for maintaining an effective balance between intensification and diversification [10]. It has demonstrated excellent performance in solving combinatorial optimization problems [11,12].

The DABC introduces two innovations: first, biased selection is used in place of the stochastic roulette wheel during the onlooker bee phase; second, partially mapped crossover is incorporated in both the onlooker and scout bee phases, enabling a more structured and informative generation of new solutions compared to the random way. These enhancements allow the algorithm to better leverage information from high-quality solutions, improving both stability and solution quality.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We propose a discrete artificial bee colony algorithm for the 2DCSP, extending the applicability of the artificial bee colony algorithm, and provide a reference for solving other combinational optimization problems.

- We introduce biased selection and a partially mapped crossover to the artificial bee colony, which improves the performance of the algorithm.

- We analyze the effect of the parameter on the performance of the algorithm and provide guidance for the combination of parameters.

- Extensive experiments involving more than one hundred instances are carried out to validate the proposed metaheuristic. It benefits readers to comprehensively understand the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed algorithm.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related works. Section 3 provides a formal definition and formulation of the problem, along with an illustrative example. Section 4 details the proposed metaheuristic approach. Experimental results and analyses are presented in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Cutting stock problems and their numerous variants have been extensively studied in the literature. The one-dimensional CSP (1CSP) is one of the classical forms, in which only the lengths of the stock and items need to be considered. The stock is a bar with a fixed length, and items cannot be split. Ravelo et al. [13] developed a heuristic and two metaheuristic algorithms to solve a 1CSP involving single-size bars, with the bi-objective of minimizing both the number of retail items kept in stock and the material loss. Karaca et al. [14] also considered a bi-objective 1CSP aimed at minimizing the trim loss and the number of welds per product. Campello et al. [15] studied two types of 1CSP involving single-size and multiple-size bars, with objectives focused on minimizing the number of stocks used and the combined costs of material waste and storage.

In the two-dimensional CSP (2CSP), both the width and length of stocks and items are considered. Here, the length of the stock is not significantly larger than its width, as is the case for the item. The stock is usually called sheet or bin, and items are of fixed size. Furini et al. [16] proposed a column generation heuristic algorithm for 2CSP under a two-stage guillotine cutting constraint, aiming to minimize the total area of bins used. Later, Furini and Malaguti [17] proposed three mixed-integer programming models, building on existing formulations, and conducted a computational comparison among them. Hadj Salem et al. [18] presented a mixed integer linear programming model for the 2CSP involving multiple bin sizes in the textile industry. The cutting pattern must meet the two-stage guillotine cut constraint. Their study considered two objectives: minimizing the total textile material used and minimizing the total number of cutting patterns. Polyakovskiy and Hallah [19] investigated a cutting stock problem with multiple-size bins and an unrestricted guillotine, proposing a hybrid metaheuristic to solve it. Libralesso and Fontan [20] and Parreño et al. [21] both studied a single-size 2D-CSP with three-stage guillotine cuts, where bins may contain defects. The former employed an iterative tree search procedure, while the latter introduced a beam search algorithm with several novel features. Parreño and Alvarez [7] later developed integer linear models for this problem and applied exact solution methods. Although a variety of sophisticated methods have been developed for standard 2CSPs, they are generally unsuitable for the problem studied in this paper, as they assume that items cannot be split.

Chen et al. [22] proposed a heuristic for a 2CSP encountered in the paper and plastic film industries. In their setting, the stock (coil) has a length much greater than its width. Input coils may have different widths and can be combined (called skiving operation) to form longer coils, with the objective of minimizing the total stock area used. Wang et al. [23] studied a bi-objective CSP in the steel industry, where skiving is also permitted to meet sheet demand. Their objectives were to minimize the material cost and the number of setups, addressed via a weighted-sum method and a column-and-row generation approach. Li et al. [24] presented a heuristic algorithm for a CSP with usable leftover, where items are significantly longer than the stock and can be split. Their model considered minimizing both material and production costs.

While these studies address 2CSPs involving stocks and items whose lengths are much greater than their widths—similar to the context of this paper—their objectives differ from the 2CSP studied here, which aims to minimize the total number of strips. Moreover, since the material in our case is silicon steel, skiving operations are not permitted. Consequently, most existing approaches are not directly applicable to our problem.

To the best of our knowledge, the artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm has been applied to various combinatorial optimization problems, including ordering scheduling [25], vehicle routing problems [11], the flight path of an unmanned autonomous helicopter [12], unrelated parallel machine scheduling [26,27], and imaging satellite mission planning [28]. Akay et al. [10] provided a survey on ABC applications in discrete optimization problems, particularly binary, integer, and mixed-integer programming problems. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the CSPs and the solution approaches.

Table 1.

Summary of the existing literature.

3. Problem Definition and Formulation

3.1. Problem Definition

Each coil is represented as a rectangle denoted by , where . Here, and are the vertical and horizontal lengths, respectively.

The value of equals the original coil width minus the trimmed edge width , as the rough edges are unusable. Typically, the trimmed edge width is set to 10. Note that edge trimming is unnecessary if the input coil is a leftover. Similarly, the required strips are of various sizes, each defined by dimensions , . A strip may be split into multiple sub-strips in the vertical direction.

The 2DCSP involves cutting a set of strips from rectangular coils of multiple sizes under specific constraints, with the objective of minimizing the total number of strips. This objective aims to enhance production efficiency and reduce operational costs. Loading strips into the cutting machine is time-consuming due to the considerable weight of silicon steel coils—often several hundred kilograms. Therefore, a higher number of strips leads to increased processing time and greater warehouse space usage.

A key feature that distinguishes this 2DCSP from those studied in [18,19] is that strips can be split into sub-strips vertically when generating cutting patterns. Moreover, unlike the problems in [20,21], the coils in this study come in different sizes and cannot be joined or merged—meaning skiving operations [23] are not allowed.

The basic constraints are as follows: strips must be obtained through two-stage guillotine cuts at most; strips cannot be rotated; and strips must lie entirely within a coil and must not overlap. Three operational constraints are as follows: the width of the leftover strip in a pattern must be larger than for reuse the next time; the surplus length of each strip in the pattern must not be larger than ; and the length of each strip must be greater than .

The mathematical model for the strip splitting problem is formulated based on the classical literature [29,30,31,32]. A mixed-integer programming model formally states the problem as follows:

Subject to:

Objective function (1) minimizes the number of strips cut from the coils. Constraints (2) and (3) make the sum of the subparts’ length equal to the original length. Constraint (4) determines that if the sub-strip exists, it must be cut from a coil, or if the sub-strip or sub-coil does not exist, there is no need to cut the sub-strip. Due to constraints (5) and (6), either there must be no residual strip in the pattern when , or the width of the leftover strip must be larger than when , which is inspired by the literature [30,31,32]. As a result of constraint (7), each pattern must meet the operational constraint. Constraints (8)–(12) determine the domain constraints for the variables. Constraint (8) imposes the condition that the of sub-strip must be larger than or equal to zero. Constraint (11) and (12) impose the condition that the value of

3.2. Illustrative Example

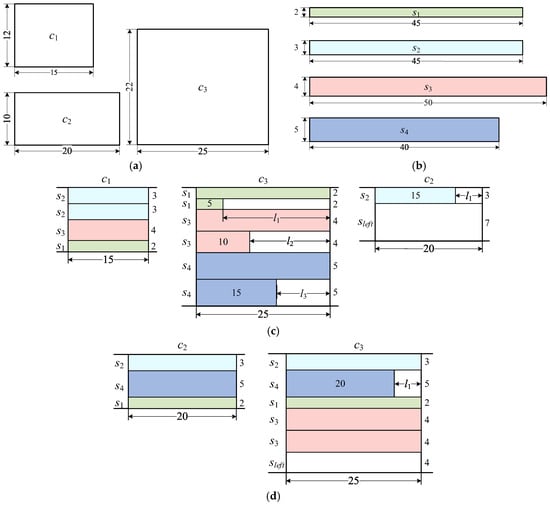

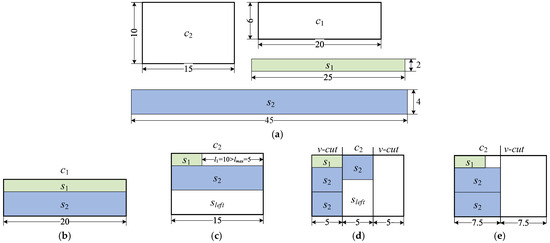

Figure 2 provides an illustrative example. There are three input coils of different sizes shown in Figure 2a and four required strips shown in Figure 2b. Two feasible cutting plans are shown in Figure 2c,d. In cutting plan 1, all coils are used. is cut into the strips , , and . The strip is divided into two sub-strips because the coil is not long enough. This situation also occurs in a next cutting pattern. is cut to satisfy the demand for , , and . is cut into strip and a leftover. In cutting plan 2, only coils and are used. The is perfectly cut into strips , , and . The is cut into all demand strips and a leftover.

Figure 2.

Illustrative example of the 2DCSP problem. (a) Input coils. (b) Demand strips. (c) Cutting plan 1. (d) Cutting plan 2.

Each cutting pattern meets the basic and operational constraints. The width of the usable leftover strip must not be less than . The surplus length of each strip in the same pattern is not larger than . Taking in cutting plan 1 as an example, the surplus lengths , , and are less than . The length of each strip is larger than .

Table 2 summarizes the information of the two solutions. It can be seen that each strip in cutting plan 1 is produced more than its demand. For example, strip has a surplus length of 20, as the total production length is 65 while the demand is only 45. In comparison, cutting plan 2 is more effective, as it uses fewer strips and generates less surplus material. Furthermore, it is evident that the choice of coil sequences significantly influences the results.

Table 2.

Cutting plan information of the illustrative example.

4. The Discrete Artificial Bee Colony for 2DCSP

4.1. The Overview of the Algorithm

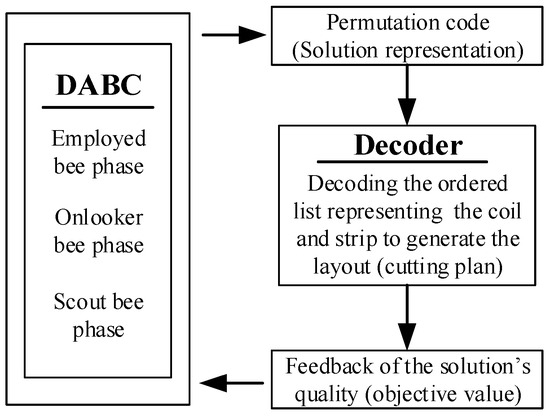

Figure 3 depicts the framework of the DABC algorithm. Solutions are encoded using permutation codes and evolved through three distinct phases, which modify both the coils using order and the strip packing order. A decoder transforms the permutation encoding into feasible cutting patterns based on the coding sequence and calculates the corresponding objective value. While the global optimization mechanism of DABC searches for the optimal sequence of strips and coils, the decoder generates a cutting plan that satisfies all problem constraints.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the framework of the proposed approach.

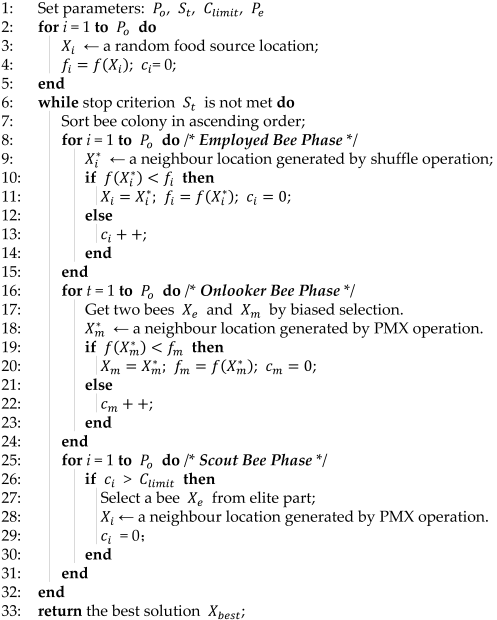

The pseudo-code of the DABC algorithm is outlined in Algorithm 1. It has four parameters: colony size (), stop criterion (), the abandonment threshold for food sources (), and the percentage of elite bees (). The algorithm initializes food source positions randomly for the bees, evaluates food sources, calculates objective value (), and initializes counter value () (lines 2–5). During the foraging cycle, the bee colony is sorted in ascending order based on the objective value. The bees subsequently perform their roles in three phases: the employed bees (lines 8–15), onlooker bees (lines 16–24), and scout bees (lines 25–31).

| Algorithm 1: DABC |

|

In the employed bee and onlooker bee phases, if a new solution is better than the current solution , then is replaced, and its counter is set to zero. Otherwise, the current solution is retained, and is incremented by one. The mechanism for generating new solutions in these phases will be elaborated in the following section. In the scout bee phase, if exceeds the threshold , solution is considered exhausted and is replaced by a newly generated solution. The three phases are executed sequentially until the stop criterion is met.

Note that our implementation of the ABC algorithm incorporates a non-standard modification in the scout bee phase. Unlike the original ABC, which allows at most one scout bee per cycle, our approach permits multiple scout bees to generate new solutions simultaneously within a single iteration. This adaptation is commonly employed for discrete optimization problems.

4.2. Encoding and Neighbor Location Generation

The solution is represented using a permutation encoding scheme. Specifically, each solution is encoded as a vector of positive integers: , where denotes a coil, and denotes a strip. The sequence of elements in the vector determines the order in which the corresponding coils and strips are utilized. Note that operations on this solution vector, including shuffle and crossover, are performed separately on the coil segment and the strip segment. This ensures the logical integrity of the solution.

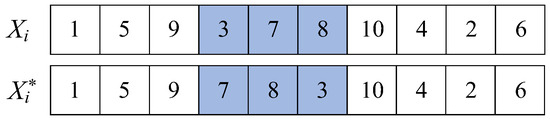

In the employed bee phase, a neighbor solution is generated through a shuffle operation, as illustrated in Figure 4. This process involves randomly selecting a contiguous substring from the encoding vector and performing a random permutation of its elements. The length of this substring is provided by , where is the length of the vector.

Figure 4.

Shuffle operation in employed bee phase. The color represents the selected substring.

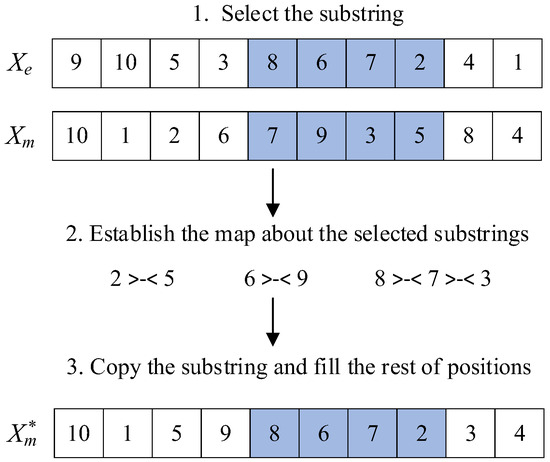

In the onlooker bee phase, biased selection instead of a stochastic roulette wheel is adopted to assign onlooker bees to high-quality food sources. First, the colony is divided into two parts: a small group of elite bees with the best cost function values and the remaining non-elite bees. Then, the algorithm randomly selects one bee, , from the elite group, and another, , from the non-elite group. A new solution is generated by applying the partially mapped crossover (PMX) operator [33,34], as illustrated in Figure 5. The length of the substring is the same as the shuffle operation

Figure 5.

PMX operation in the onlooker and scout bee phases. The color represents the selected substring.

In the scout bee phase, the DABC similarly employs biased selection and the PMX method to generate a new neighbor location. These strategies enhance the algorithm’s exploitation capability by effectively leveraging information from high-quality solutions.

4.3. Decoding Procedure

The decoding procedure is a randomized constructive heuristic that converts the encoded vector into a feasible cutting plan, as outlined in Algorithm 2. The process begins by initializing the first coil as an empty cutting pattern and selecting the first strip from the ordered vector as the current strip to be placed. Three feasibility checks are then performed to determine whether the strip can be allocated to the current coil. The test verifies whether the strip satisfies the first operational constraint. If the cutting pattern already contains one or more strips, the test is applied to ensure compliance with the second constraint. Finally, when a strip must be split, the test guarantees that the remaining segment still meets the third operational requirement.

| Algorithm 2: Decoding Procedure |

|

If a strip passes all feasibility checks and does not require splitting, it is allocated to the current cutting pattern (lines 8–10). When the strip is longer than the coil or the current pattern, it must be split (line 12). In such cases, the algorithm introduces a randomized decision: a random number is generated from the interval [0, 1], and the strip is placed only if (line 11).

If a strip cannot be placed—whether due to failed checks or the split condition—the procedure searches through the remaining strips in sequence to identify the first feasible one (lines 7–16). This search strategy helps mitigate inefficiencies arising from the initial strip ordering, thereby improving the likelihood of constructing high-quality solutions.

If no remaining strips can be accommodated in the current pattern, the search terminates, the pattern is finalized, and the algorithm proceeds to the next coil—or shortens the current coil if applicable (lines 20–24)—to initialize a new pattern. These steps repeat iteratively until all strips have been placed or no usable coil material remains.

When a strip must be split, the decoder considers two approaches: splitting it to fit the exact remaining length of the cutting pattern or dividing it into equal segments. The latter is preferred if it satisfies all three feasibility constraints.

Figure 6 presents an illustration of splitting strategies. There are two input coils, and , and two demand strips, and . When generating cutting pattern 1, the second pattern is infeasible because of the constraint (the maximal surplus of , , is larger than the ) is not satisfied, as shown in Figure 6b,c. If strip is split according to the remaining length of the current pattern, the resulting solution uses a total of six strips, shown in Figure 6d. In contrast, if is divided into equal segments, the total number of strips is reduced to five, as illustrated in Figure 6e. The second method obtains a better solution, which is the reason for preferring it.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the splitting method. (a) Input coils and demand strips. (b) Cutting plan 1. (c) Infeasible pattern. (d) Solution 1 (split directly). (e) Solution 2 (split equally).

5. Numerical Experimental Results

All experiments were performed on an E5-2676 CPU @2.4 GHz with 32 GB RAM, running Windows. The algorithms were implemented in C++11 on Visual Studio 2019. The dataset proposed by the literature [8] consists of 135 instances from the transformer manufacturing company. It has three sets (Set1, Set2, Set3). Each set contains three subsets, and every subset includes fifteen problems. Therefore, this sums up to 3 × 3 × 15 = 135. The values are set as follows: , , and .

This section is organized as follows. First, we analyze the influence of parameter settings on the performance of the DABC algorithm for the 2DCSP and identify the optimal configuration. Next, the algorithm’s performance is evaluated and compared against competitive algorithms. Finally, a statistical analysis is conducted to assess the significance of the experimental results.

5.1. Configuration of the DABC

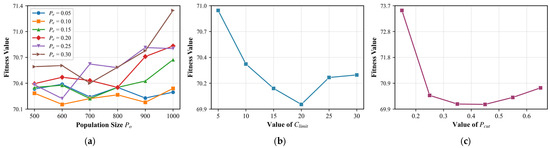

The stopping criterion for the algorithms is set to 120 s to ensure fair comparison, as the algorithms perform a different number of solution evaluations per iteration. Therefore, a comparison based on an equal number of iterations is not appropriate for the proposed method. Four parameters require configuration: , , , and . To analyze their impact on algorithm performance and calibrate the metaheuristic, we performed extensive experiments on multiple instances. Guided by the ranges recommended in [8,10] (see Table 3), we selected six evenly spaced values for each parameter. For each value, the algorithm was executed 30 times. Since the number of elite individuals depends on both and , a total of 36 paired experimental configurations were evaluated. The corresponding results are summarized in Figure 7.

Table 3.

Parameter range and value for the DABC.

Figure 7.

The effects of the four parameters on the performances of the DABC. (a) Effects of parameters and . (b) Effect of parameter . (c) Effect of parameter .

As shown in Figure 7a, increasing the population size does not improve results; in fact, larger populations tend to degrade performance. However, the smallest population size is not optimal either. A similar pattern is observed for , where the curve for is lower than the others. The optimal values for and are found to be 600 and 0.10, respectively.

From Figure 7b,c, fitness first decreases and then increases with and , indicating that both overly small and large values impair performance. The best result is achieved at , while values between 0.30 and 0.45 yield better outcomes. Based on these observations, the final parameter values are listed in Table 3.

5.2. The Performance of the Algorithm on Datasets

The proposed DABC is evaluated against three state-of-the-art metaheuristics from the literature [8]: a biased genetic algorithm (BGA), decimal grey wolf optimization (DGWO), and variable neighborhood search (VNS). For a more comprehensive comparison, two additional variants of the artificial bee colony algorithm are also implemented: a basic ABC (bABC) and a modified ABC (mABC) based on [10]. Both bABC and mABC adopt the standard roulette wheel selection in the onlooker bee phase and random solution generation in the scout bee phase. The bABC uses an insert operation in the employed bee phase and position-based crossover in the onlooker phase, whereas the mABC employs a swap operation and partially mapped crossover.

Given the stochastic nature of the algorithms, each one was executed 30 independent runs per instance to ensure statistical reliability. Performance was assessed using the minimum (Min), maximum (Max), mean (Mean), and standard deviation (Std) of the objective values obtained over these runs. Table 4 summarizes the averages of these four metrics across the nine datasets, with the best-performing values highlighted in bold. Detailed results for each instance are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 4.

Computational results of the algorithms on all datasets.

As shown in Table 4, the four indicator values of the six algorithms in Set11, Set12, and Set13 are very close, which indicates that all of them are better at solving small-size problems. However, the DABC obtained smaller values in the remaining six datasets than the other five algorithms. In comparison with the BGA, bABC, and mABC, the DABC algorithm achieves average reductions of more than 3.9%, 7.5%, and 5.4% in the minimum values for Set 2, respectively, and more than 7.6%, 9.8%, and 7.5% for Set 3, respectively.

Moreover, the DABC demonstrates a significant reduction in standard deviation, with average decreases of over 55%, 34%, and 23% in Set 2, respectively, and over 77%, 43%, and 42% in Set 3, respectively. The experimental results demonstrate that the DABC algorithm can achieve higher-quality solutions and deliver more stable results than the compared methods.

To elucidate the individual contribution of the improvements in the algorithm, we analyzed the progressive performance gains between bABC, mABC, and DABC. The enhancement from bABC to mABC is attributed mainly to the introduction of the PMX operator. The consistent superiority of mABC over bABC, as evidenced in Table 4, confirms that PMX boosts performance by facilitating a more effective exploration of the solution space through structured sequence exchanges. The subsequent outperformance of DABC over mABC, both employing PMX, highlights the critical role of the biased selection strategy. This strategy provides a decisive incremental improvement by intensifying the search around the best-known solution, thereby guiding the crossover more effectively.

To establish a baseline for evaluating the metaheuristics, the mathematical model was solved using the commercial solver CPLEX 12.8 on the smaller datasets (Set11, Set12, Set13) with a time limit of 3600 s. The results for each instance are shown in Supplementary Materials. The comparative results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Performance gaps of the metaheuristic algorithms relative to the solver baseline, measured by the mean metric on small instances.

It reveals that CPLEX found the optimal or a high-quality solution for these instances. Notably, for some cases in Set12, certain metaheuristics (e.g., bABC and mABC) found solutions that marginally outperformed the best solution obtained by CPLEX within the limited time. The proposed metaheuristic consistently delivered solutions that were either competitive with or very close to the CPLEX baseline, with an average gap of less than 2%. This demonstrates their capability to reliably approximate near-optimal solutions, providing a strong justification for their use on larger-scale problems where exact solvers are impractical.

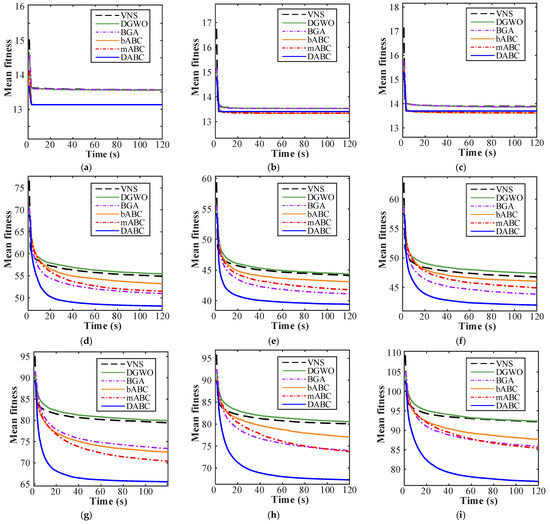

Figure 8 presents the convergence curves of the six algorithms across nine datasets, averaged over 15 instances per dataset. On Sets 11–13, all algorithms converge at a similar rate. In the remaining datasets, however, DABC achieves the fastest convergence. BGA ranks second in convergence speed on Sets 21–23, though it is outperformed by both bABC and mABC on Set 31. On Sets 32–33, BGA converges rapidly within the first 60 s compared to bABC and mABC, yet all three ultimately reach similar final values. Notably, the convergence curves of VNS and DGWO are nearly identical throughout.

Figure 8.

Convergence curves of six algorithms for nine datasets. (a) Set11. (b) Set12. (c) Set13. (d) Set21. (e) Set22. (f) Set23. (g) Set31. (h) Set32. (i) Set33.

A detailed view of Figure 8 shows that while VNS converges quickly in the early stages, it is overtaken by DABC, BGA, bABC, and mABC after approximately 10 s. Furthermore, the mABC converges faster and to better values than the bABC, underscoring the efficacy of its incorporated improvements. Overall, the DABC outperforms other algorithms, demonstrating not only accelerated convergence but also superior results.

5.3. Statistical Significance of Results

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed to assess the statistical significance of the results obtained by the DABC algorithm. The alternative hypothesis, which posits a difference between the results of the two algorithms, is accepted when the p-value is less than 0.05. Conversely, the null hypothesis, which suggests no difference between the results of the two algorithms, is accepted when the p-value exceeds 0.05. The p-values are shown in Table 6. For each performance metric (Min, Mean, Max, Std), the test compares the paired results of two algorithms across all 15 instances within a given dataset. This evaluates whether the performance difference between the two algorithms is statistically significant across the entire set of instances in the dataset.

Table 6.

Wilcoxon test p-values comparing DABC against three competitive algorithms across four evaluation indicators.

As shown in Table 6, there is statistical evidence of a significant difference between the results obtained by the DABC and the other compared algorithms in Set2 and Set3, with two exceptions: the comparison between DABC and BGA on the minimum indicator in Set22 and the comparison between DABC and mABC on the standard deviation indicator in Set21. Additionally, there is statistical evidence of no difference between the results obtained by the DABC and the other compared algorithms in Set11, Set12, and Set13. Based on these findings and the analysis in the previous section, it can be concluded that the superiority of the DABC algorithm over the other competitive algorithms is statistically significant for large-scale instances, while all algorithms demonstrate similarly effective performance on small-scale problems.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a discrete artificial bee colony algorithm to address a cutting stock problem arising in the production of iron cores for high-power transformers. The algorithm introduces biased selection and partially mapped crossover in the onlooker bee phase to improve information sharing. In the scout bee phase, the PMX operator is applied between exhausted and elite individuals to generate new solutions. These enhancements promote more effective knowledge transfer among high-quality solutions, strengthening both exploitation and exploration. Experimental results show that the proposed DABC reduces the total number of strips by an average of over 3.9% for Set 2 and 7.6% for Set 3 compared to competitive approaches.

The reduction in the number of strips achieved by our method brings clear operational benefits. In practice, each coil requires about thirty minutes to load and set up. Thus, for a typical order, our approach saves 2–4 h of crane and equipment time. It also reduces warehouse space requirements, improving logistics and cutting overhead costs. These savings highlight the direct industrial value of our research.

Furthermore, the DABC significantly reduces the standard deviation—by over 55% on average in Set 2 and 77% in Set 3—demonstrating markedly improved solution stability. It also converges faster than the five algorithms in most datasets. These results collectively confirm the robustness and efficiency of the proposed method. While the parameters in this study were tuned to static values through a systematic sequential approach, the potential of employing an adaptive parameter strategy presents a promising direction for future research. Furthermore, automated tuning methods like CRS-Tuning and F-Race [35] offer advantages in potentially finding better configurations. Future work will focus on applying these advanced tuning methodologies to further optimize algorithm performance. Examining the mathematical model of the problem is also one of the meaningful future works.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/machines13121106/s1, Table S1. Computational results of three approaches on Set 11 dataset. Table S2. Computational results of three approaches on Set 12 dataset. Table S3. Computational results of three approaches on Set 13 dataset. Table S4. Computational results of three approaches on Set 21 dataset. Table S5. Computational results of three approaches on Set 22 dataset. Table S6. Computational results of three approaches on Set 23 dataset. Table S7. Computational results of the six algorithms on Set 31 dataset. Table S8. Computational results of the six algorithms on Set 32 dataset. Table S9. Computational results of the six algorithms on Set 33 dataset. Table S10. Computational results obtained by Solver on Set11, Set12, and Set13.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L.; methodology, Q.L.; software, Z.T.; validation, Q.L., and Z.T.; formal analysis, Q.L., Z.T., and C.P.; investigation, Q.L.; resources, Q.L.; data curation, Z.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.T. and C.P.; visualization, Q.L.; supervision, C.P.; project administration, Q.L.; funding acquisition, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province, grant number 20252BEJ730194; the Science and Technology Research Project of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education, grant number GJJ2400705; and the High-level Talents Research Foundation of Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, grant number jxust-22.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the numerical experiments are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following notations are used to construct the model:

| The number type of width of strips; | |

| The number of coils; | |

| Index of strips; | |

| Index of coils; | |

| Index of sub-strips; | |

| Index of sub-coils; | |

| , | The vertical and horizontal length of input coil; |

| The edge-trimmed width; | |

| , | The vertical and horizontal length of demand strip; |

| The minimum width of the leftover strip in a pattern; | |

| The maximum surplus length of each strip in the pattern; | |

| The minimum length of each strip; | |

| Constant, maximum number of sub-strips that can be obtained. , where corresponds to the largest integer smaller than or equal to x; | |

| Integer variable, the horizontal length of the sub-strip, ; | |

| Constant, maximum number of sub-coils that can be split. , where corresponds to the largest integer smaller than or equal to x; | |

| Integer variable, the horizontal length of the sub-coil, ; | |

| Binary variable, equal to 1 if the sub-strip of strip is assigned to the sub-coil of coil , 0 otherwise; | |

| 1 = there is residual strip in sub-coil of coil , 0 = other; | |

| 1 = the sub-strip exists, 0 = other; |

References

- Duta, E.-A.; Jimeno-Morenilla, A.; Sanchez-Romero, J.-L.; Macia-Lillo, A.; Mora-Mora, H. An approach to apply the Jaya optimization algorithm to the nesting of irregular patterns. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2024, 11, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, R.J.; Paterson, M.S.; Tanimoto, S.L. Optimal packing and covering in the plane are NP-complete. Inf. Process. Lett. 1981, 12, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Tang, C.; Zhang, H.; Wu, S.; Wei, L.; Liu, Q. An iteratively doubling binary search for the two-dimensional irregular multiple-size bin packing problem raised in the steel industry. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 162, 106476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.F.; Wäscher, G. A MIP model and a biased random-key genetic algorithm based approach for a two-dimensional cutting problem with defects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 286, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, S.; Liu, Q.; Wei, L.; Lin, L.; Leng, J. An exact approach for the constrained two-dimensional guillotine cutting problem with defects. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 2986–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, B.-I.; Cho, H. Multiple-choice knapsack-based heuristic algorithm for the two-stage two-dimensional cutting stock problem in the paper industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 5675–5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreño, F.; Alvarez-Valdes, R. Mathematical models for a cutting problem in the glass manufacturing industry. Omega 2021, 103, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Du, B.; Rao, Y.; Guo, X. Metaheuristic algorithms for a special cutting stock problem with multiple stocks in the transformer manufacturing industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 210, 118578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D. An Idea Based on Honey Bee Swarm for Numerical Optimization; Technical Report-TR06; Erciyes University, Engineering Faculty, Computer Engineering Department: Kayseri, Türkiye, 2005; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Akay, B.; Karaboga, D.; Gorkemli, B.; Kaya, E. A survey on the Artificial Bee Colony algorithm variants for binary, integer and mixed integer programming problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 106, 107351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.; Cui, Z.; Li, M. A dynamical artificial bee colony for vehicle routing problem with drones. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 107, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Chen, M.; Shao, S.; Wu, Q. Improved artificial bee colony algorithm-based path planning of unmanned autonomous helicopter using multi-strategy evolutionary learning. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 107374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelo, S.V.; Meneses, C.N.; Santos, M.O. Meta-heuristics for the one-dimensional cutting stock problem with usable leftover. J. Heuristics 2020, 26, 585–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, T.K.; Samanlioglu, F.; Altay, A. Solution approaches for the bi-objective Skiving Stock Problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 179, 109164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, B.S.C.; Ghidini, C.T.L.S.; Ayres, A.O.C.; Oliveira, W.A. A residual recombination heuristic for one-dimensional cutting stock problems. TOP 2022, 30, 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furini, F.; Malaguti, E.; Durán, R.M.; Persiani, A.; Toth, P. A column generation heuristic for the two-dimensional two-staged guillotine cutting stock problem with multiple stock size. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 218, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furini, F.; Malaguti, E. Models for the two-dimensional two-stage cutting stock problem with multiple stock size. Comput. Oper. Res. 2013, 40, 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, K.H.; Silva, E.; Oliveira, J.F.; Carravilla, M.A. Mathematical models for the two-dimensional variable-sized cutting stock problem in the home textile industry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 306, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakovskiy, S.; M’hAllah, R. A lookahead matheuristic for the unweighed variable-sized two-dimensional bin packing problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 299, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libralesso, L.; Fontan, F. An anytime tree search algorithm for the 2018 ROADEF/EURO challenge glass cutting problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 291, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreño, F.; Alonso, M.; Alvarez-Valdes, R. Solving a large cutting problem in the glass manufacturing industry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 287, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, X.; Ouelhadj, D.; Cui, Y. A heuristic for the skiving and cutting stock problem in paper and plastic film industries. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2019, 26, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiao, F.; Zhou, L.; Liang, Z. Two-dimensional skiving and cutting stock problem with setup cost based on column-and-row generation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 286, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Chen, Y.; Hu, X. Manufacturing-oriented silicon steel coil lengthwise cutting stock problem with useable leftover. Eng. Comput. 2022, 39, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-C.; Xu, J.; Bai, D.; Chung, I.-H.; Liu, S.-C.; Wu, C.-C. Artificial bee colony algorithms for the order scheduling with release dates. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 8677–8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.; Yang, H. Scheduling unrelated parallel machines with preventive maintenance and setup time: Multi-sub-colony artificial bee colony. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 125, 109154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.; He, S. An adaptive artificial bee colony for unrelated parallel machine scheduling with additional resource and maintenance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 205, 117577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, D. A Hybrid Discrete Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm for Imaging Satellite Mission Planning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 40006–40017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, P.C.; Gomory, R.E. A linear programming approach to the cutting-stock problem. Oper. Res. 1961, 9, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Pruncu, C.I.; Khan, A.S.; Naeem, K.; Abas, M.; Khalid, Q.S.; Aziz, A. A Mathematical Model for Reduction of Trim Loss in Cutting Reels at a Make-to-Order Paper Mill. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, V.M.R.; Leao, A.A.S.; Oliveira, J.F.; Santos, M.O. Models for the two-dimensional level strip packing problem—A review and a computational evaluation. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2020, 71, 606–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, A.; Martello, S.; Vigo, D. Models and Bounds for Two-Dimensional Level Packing Problems. J. Comb. Optim. 2004, 8, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, V. A review on genetic algorithm: Past, present, and future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E.; Lingle, D. Alleles, Loci, and the Traveling Saleman Problem. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Genetic Algorithms and Their Applications, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 24–26 July 1985; pp. 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veček, N.; Mernik, M.; Filipič, B.; Črepinšek, M. Parameter tuning with Chess Rating System (CRS-Tuning) for meta-heuristic algorithms. Inf. Sci. 2016, 372, 446–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).