Abstract

Vibrations induced by marine environmental loads can compromise the operational performance of offshore platforms and, in severe cases, result in structural instability or overturning. This study proposes a biomimetic nonlinear X-shaped vibration isolation system (NXVIS) to suppress earthquake-induced vibration response in offshore platforms. Compared with traditional passive vibration isolators, the key innovations of the NXVIS include: (1) the proposed NXVIS can be tailored to different load requirements and resonant frequencies to accommodate diverse offshore platforms and environmental loads; (2) By adjusting isolator parameters (e.g., link length and spring stiffness, etc.), the anti-vibration system can achieve different types of nonlinear stiffness and a large-stroke quasi-zero stiffness (QZS) range, enabling ultra-low frequency (ULF) vibration control without compromising load capacity. To evaluate the effectiveness of the designed NXVIS for vibration suppression of jacket offshore platforms under seismic loads, numerical analysis was performed on a real offshore platform subjected to seismic loads. The results show that the proposed nonlinear vibration isolation solution significantly reduces the dynamic response of deck displacement and acceleration under seismic loads, demonstrating effective low-frequency vibration control. This proposed NXVIS provides a novel and effective method for manipulating beneficial nonlinearities to achieve improved anti-vibration performance.

1. Introduction

Jacket platforms are fixed platforms secured to the seabed by steel piles penetrating a certain depth, which are widely used in offshore oil and gas production. Due to structural characteristics and operating environment, jacket platforms are susceptible to various marine environmental loads, such as earthquakes, wind, waves, ice loads, and ship impacts. Long-term exposure to these marine environments can cause structural vibrations of jacket platforms, which can cause fatigue damage to the steel structure, impacting platform production efficiency and even leading to catastrophic failure [1,2]. Furthermore, external disturbances inevitably affect worker productivity and comfort, negatively impacting production cost control. Extensive research has been conducted on vibration control of jacket platforms under marine environmental loads [3]. However, most efforts have focused on suppressing vibrations caused by wave excitation, while limited research has considered seismic excitation [4,5,6]. This is because waves are the most common loads on offshore platforms, constantly impacting structural stability [3,7]. However, structural damage caused by waves is long-term, and the initial site selection of offshore platforms usually considers local hydrological conditions. Therefore, limited wave loads can cause irreversible damage to the platform in a single instance. However, seismic loads are unpredictable and have a wide frequency range (mostly concentrated between 0.7 and 3.0 Hz) [8,9]. Strong earthquakes often have catastrophic effects on offshore platforms and can cause severe damage to these structures [5,6,10,11]. Furthermore, the first-order vibration mode of most offshore platforms falls within the frequency range of seismic energy [4], which can trigger resonance in the offshore platform and amplify the destructive power of the earthquake. Statistics indicate that approximately hundreds of offshore platforms are currently located in seismically active areas [5]. Therefore, studying the vibration control of jacket offshore platforms under seismic loads is of great significance.

The jacket offshore platform exhibits a low fundamental natural frequency and a high modal density in its vibrational characteristics. The overall structure has strong coupling and nonlinearity, and the external load has uncertainty, making offshore platform vibration control a very challenging problem [3]. Active and semi-active control are not suitable for long-term vibration control of large structures such as offshore platforms due to their high energy consumption and the need for accurate models of the controlled objects [2]. Passive control is the earliest and most widely used vibration control method due to reliability, low cost, and the advantages of no electronic equipment. Passive control achieves the purpose of vibration reduction by arranging absorption, dissipation or vibration isolation devices in the target structure and utilizing the characteristics of the device itself [3,12,13,14]. Dissipation method primarily utilizes the energy dissipation mechanism of the damping structure, i.e., by irreversibly converting the mechanical energy (kinetic and potential energy) that causes vibration into other forms of energy (primarily heat) and dissipating it, thereby suppressing the vibration response. For example, Mostafa Vaezi et al. [15] numerically simulated jacket offshore platforms with various distributions and three different support-viscous damper system configurations (knuckle, herringbone, and diagonal configurations) and various support stiffnesses under irregular wave loads, and proposed a spatially optimized layout for the support-viscous damper system. Jiang et al. [16] investigated the effectiveness of viscous dampers (VDs) in reducing vibration on offshore platforms under the combined effects of wind, waves, and earthquakes. The results showed that VDs placed diagonally at each structural level can effectively suppress platform vibration under both isolated earthquakes and wind–wave–earthquake conditions. According to their research results, passive control systems based on these devices are effective for offshore platforms under wave loads. The absorption method is the dominant approach in passive vibration control on offshore platforms. Its core principle is to attach a substructure (a mass-spring-damper system) and tune its frequency to the natural frequency of the main structure, absorbing the main structure’s vibration energy through anti-phase motion. For example, Cui et al. [17] applied tuned liquid multi-column damper (TLMCD) to the columns of tension leg platforms (TLP) to attenuate the heave response of TLP. Ghasemi et al. [18] used shape memory alloy pounding tuned mass damper (SMA-PTMD) to control the wave-induced vibration of jacket offshore platforms. The results showed that SMA-PTMD can effectively reduce the displacement response of the platform deck. Liu et al. [19] investigated the dynamic response of jacket offshore platforms under the action of wave and seismic excitation using multiple tuned mass dampers (MTMDs), considering the influence of soil–structure interaction (SSI). Furthermore, the core concept of isolation method is to insert a “flexible layer” (i.e., an isolation system) between the vibration source (e.g., waves, earthquakes) and the objective structure to be protected (e.g., platform deck, equipment). This modifies the dynamic characteristics of system, thereby reducing the transfer of vibration energy. It also shifts the system’s natural frequency away from the frequencies of major environmental loads (such as earthquakes and waves), avoiding resonance. For example, Ou et al. [11] employed a rubber vibration isolation system to reduce the vibration response of jacket offshore platforms under wave loads. The isolation system consists of passive dampers, which primarily dissipate vibration energy through their damping properties. However, these passive control devices are designed based on the characteristics of the structure or specific excitation and can only perform optimally at a certain frequency ratio. That is, they cannot work properly when the dynamic characteristics of the structure or load change [3,20]. The frequency band of earthquakes is relatively wide, and existing passive control facilities cannot achieve ideal vibration control. In summary, it is very important to develop a passive vibration control method that can be customized according to different load requirements and resonant frequencies, is basically maintenance-free, and is effective across the entire seismic frequency range.

In recent years, passive vibration isolators, developed by leveraging the advantages of nonlinearity, may offer an effective solution. Traditional linear passive vibration isolators cannot resolve the contradiction between low-frequency vibration isolation and load-bearing capacity [21]. To isolate low-frequency vibrations, it is necessary to reduce stiffness; however, soft springs exhibit large static deformations and suffer from poor static stability and load-bearing capacity. An ideal vibration isolation system should meet the requirements of low-frequency and broad-band frequency vibration suppression without reducing the system’s load-bearing capacity [22]. Nonlinear passive vibration isolation systems represent a significant advancement in the field, marking a transition from static, fixed-performance technologies toward dynamic and adaptively capable solutions. Through ingenious mechanical design, these systems achieve nonlinear dynamic characteristics that lead to breakthrough performance, particularly in addressing challenges such as ULF vibration isolation and high load-bearing/counter-impact capacity [23,24,25]. To this end, many novel structures or control methods have been proposed to improve vibration isolation performance. For example, the 4-DOF system studied by Amer et al. [12] reveals rich dynamic behaviors, including chaos and quasi-periodicity, which are crucial for understanding the system’s limits. Similarly, in-depth analysis of fundamental nonlinear systems such as planar double pendulums [26] can provide insights into internal resonance and stability, which are fundamental concepts in designing nonlinear vibration control strategies. Other innovative applications and analyses that more directly exploit nonlinearity for vibration isolation include quasi-zero structures, compliant mechanisms based quasi zero stiffness isolator, origami structures, smart materials and bionic X-shaped mechanisms [18,25,27,28,29,30]. Among them, the bionic NXVIS has received widespread attention. This method is inspired by the vibration-suppressing properties of animal legs/limbs. Jing’s research team has developed a large number of simulated nonlinear X-shaped anti-vibration methods and conducted in-depth research on nonlinear stiffness, damping, and inertia, proving the reliability of the NXVIS [22]. Due to its excellent nonlinear adjustable characteristics, it enables the design of passive isolators that combine low dynamic stiffness with high load-bearing capacity, achieving tunable ULF and broadband vibration suppression [22]. In addition, the nonlinear damping in the system can achieve energy dissipation, further reducing the amplitude of structural vibration. It is well known that the deck layer is the part with the most concentrated mass of the offshore platform and is also an important place for oil and gas production and workers’ living [3]. The nonlinear characteristics of the NXVIS mean that the isolation system can achieve ULF and broadband vibration suppression under seismic loads while ensuring the stability of the deck layer. However, there are no published reports on the results of using the biomimetic NXVIS for offshore platform vibration control under seismic excitation.

In summary, this paper develops a biomimetic NXVIS for vibration control of jacket offshore platforms under seismic loads. Through theoretical research and numerical simulation under real marine conditions, the effectiveness of the proposed NXVIS for vibration control of jacket offshore platforms under seismic loads is systematically discussed. The second part of this paper formulates a mathematical model of the NXVIS, introduces its load-bearing capacity and adjustable nonlinear characteristics, and verifies its ULF and broad-band frequency vibration isolation performance. The third part introduces the structure and characteristics of the NRB’ jacket platform and formulates a dynamic model of the offshore platform equipped with the NXVIS. The fourth part discusses the anti-vibration performance of the NRB’ platform based on the NXVIS using two typical seismic loads as an example. Finally, a summary of the entire paper is given.

2. Biomimetic Nonlinear X-Shaped Anti-Vibration Mechanism

2.1. Modeling of the X-Shaped Anti-Vibration Mechanism

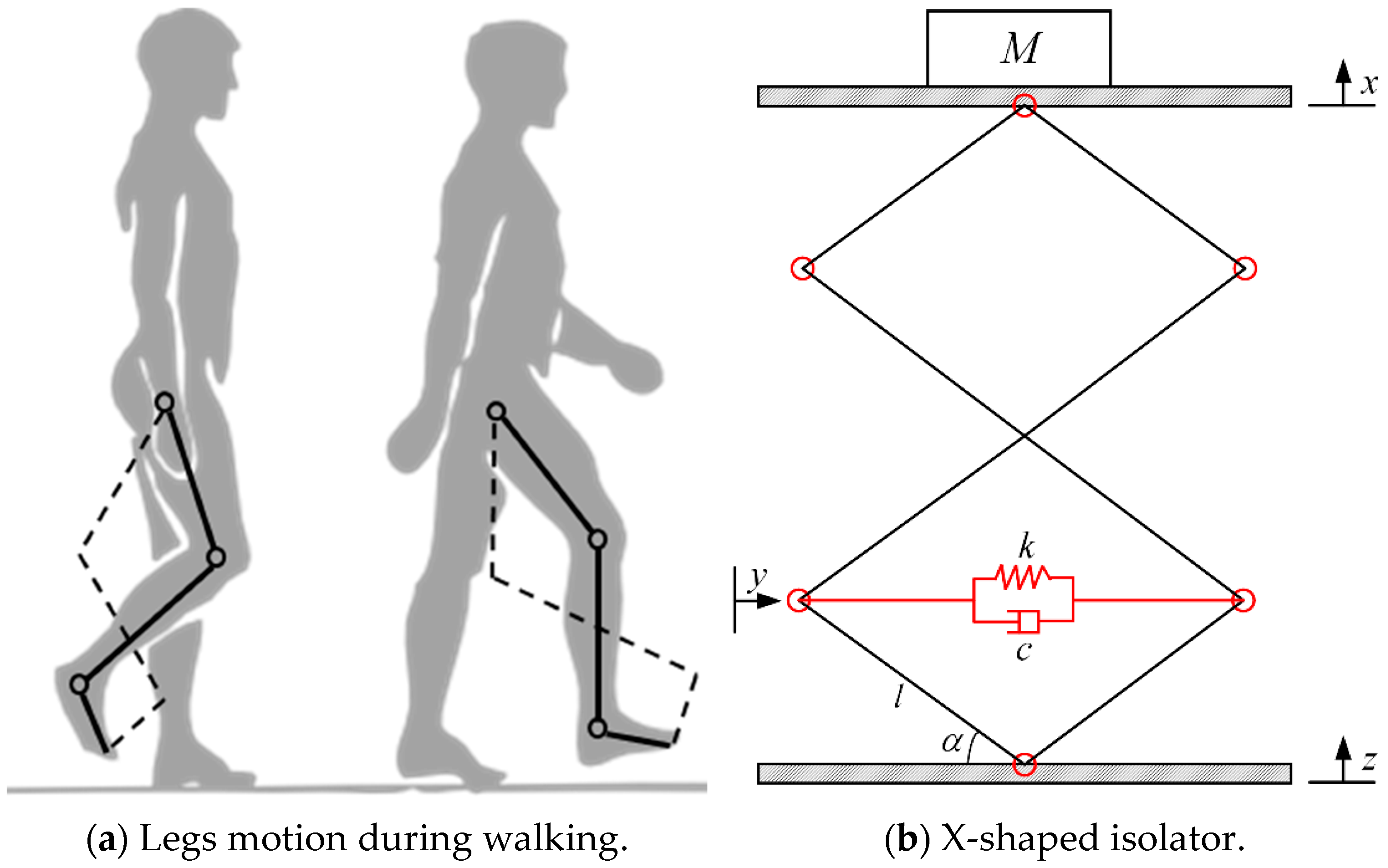

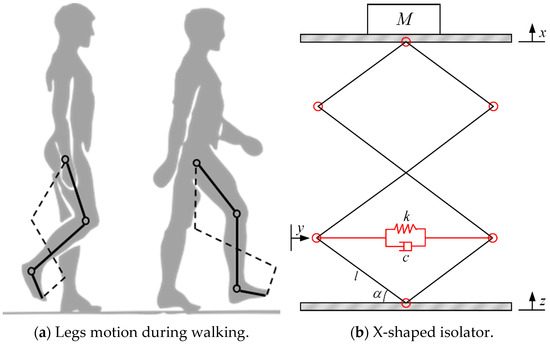

Drawing inspiration from the exceptional vibration suppression mechanisms inherent to biological systems, this research introduces an innovative biomimetic isolation strategy specifically designed for jacket offshore platforms. This method can obtain superior ULF vibration isolation and superior anti-vibration performance across a wide frequency range. A schematic layout of the proposed bio-inspired NXVIS is shown in Figure 1. The isolation structure consists of an X-shaped support leg to simulate human knee bending and a spring-damper system to simulate leg muscles.

Figure 1.

The biomimetic NXVIS.

As shown in Figure 1, the biomimetic NXVIS (Figure 1b) draws inspiration from the biomechanical configuration of the human leg during gait, with clearly labeled structural parameters. The target vibration isolation layer M is supported by the X-shaped structure. The bar length and initial installation angle of the X-shaped structure are l and α, respectively. The displacements of the top layer and the ground are x and z, respectively. A spring and damper are placed at the bottom of the NXVIS, with their stiffness and damping coefficients being k and c, respectively. Findings from the literature confirm the capability of the X-shaped isolator to achieve high static stiffness concurrently with low dynamic stiffness [22]. In this model, the bars of the X-shaped structure are considered rigid bodies. Thus, the system’s deformation arises solely from the spring and damper, and the geometric change in the mechanism. Furthermore, the mass and frictional damping of the rods in the X-shaped structure are neglected, and the structure is treated as a massless rigid connection. This practice of ignoring the mass of the bar and friction damping does not affect the generality of the conclusions, which has been confirmed in previous studies [22,31].

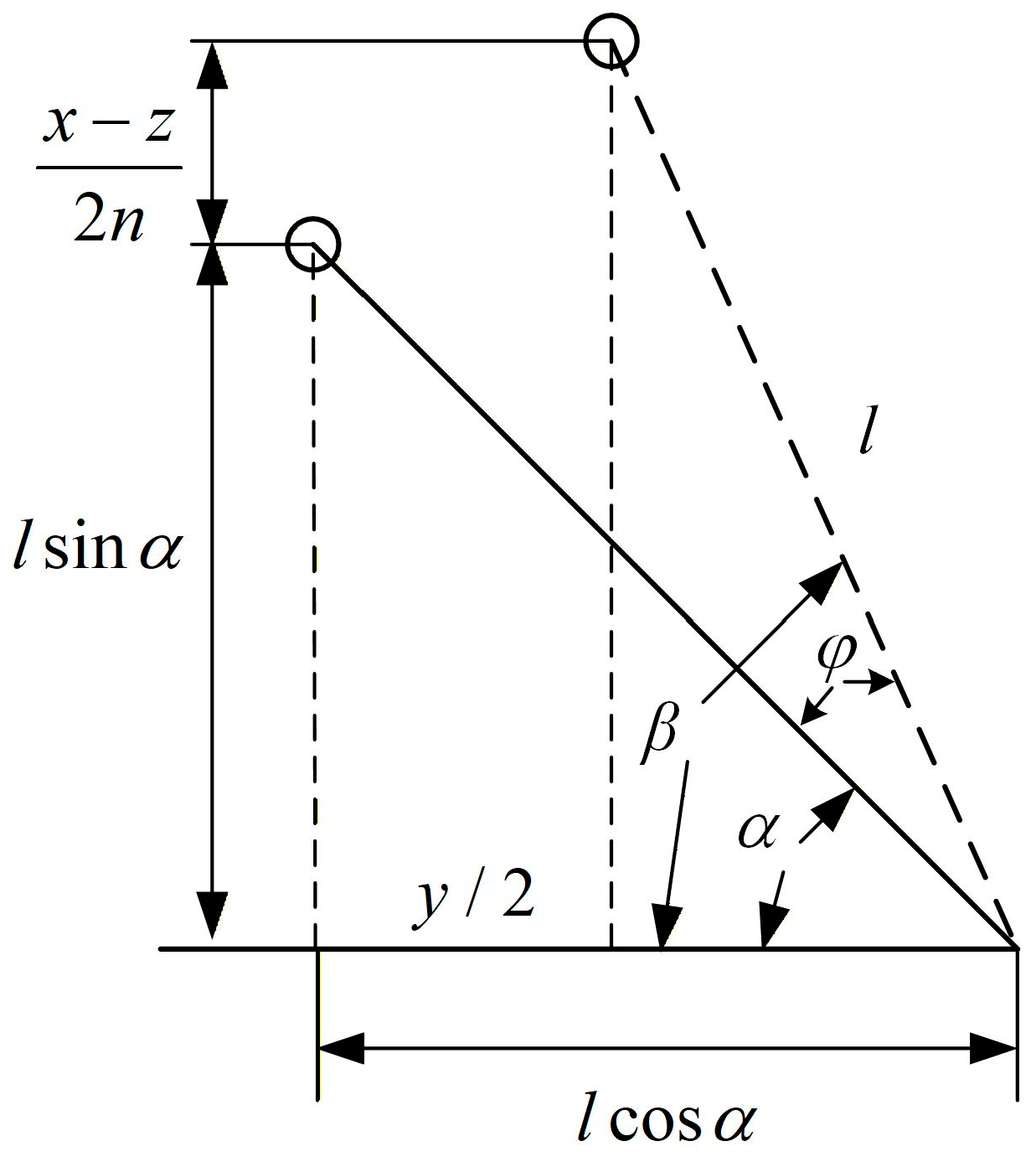

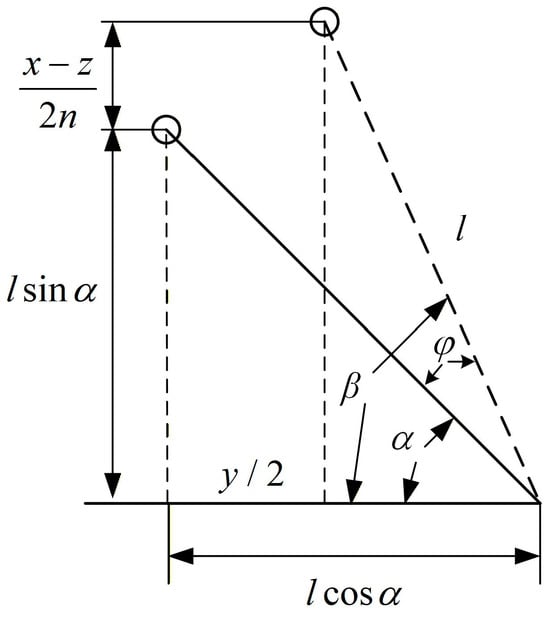

Due to the relative motion between the target layer and the base layer, geometric changes will occur between the NXVIS, as shown in Figure 2. Note that n is the number of layers in the X-shaped vibration isolation structure.

Figure 2.

Dynamic changes in geometric relationships.

The spring extension y can be written as,

where .

According to the above geometric relationship and Lagrange principle, the dynamic equation of the X-shaped anti-vibration mechanism is as follows,

where ys is the extension of the spring due to the weight of the loading M, which can be written as,

where β is the angle between the isolator and the ground when the spring is in its original length and not subject to load M. It is equal to the sum of the angles α and φ. The detailed calculation process of the dynamic equation can be found in Reference [22].

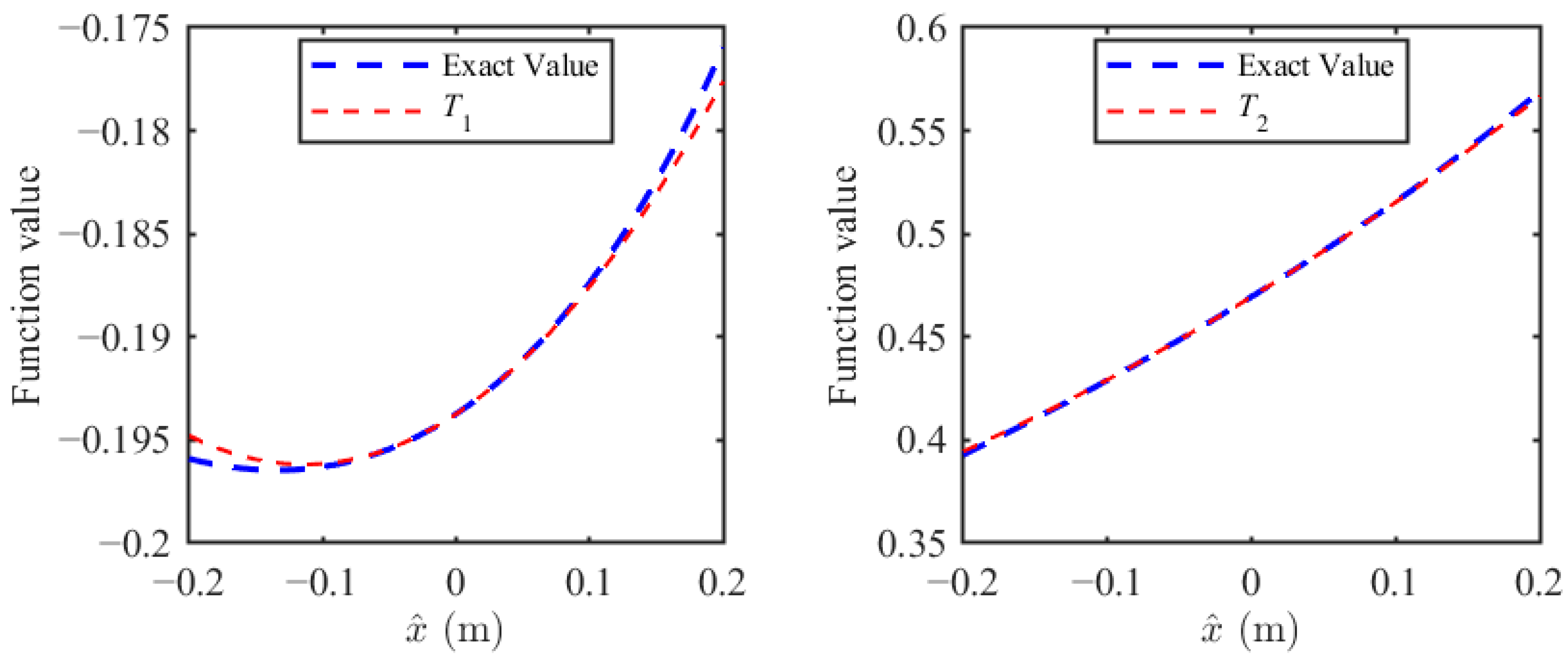

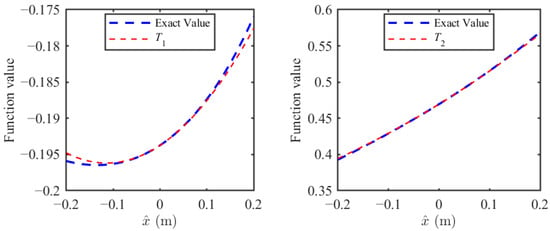

To avoid singularities or discontinuities in the computational domain and to facilitate subsequent calculations using the harmonic balance method, the Taylor expansion is adopted. The stiffness term and damping term in Equation (2) are Taylor expanded at , which can be expressed as,

where the coefficients are listed in the Appendix B. The accuracy of the Taylor expansion was evaluated by comparing the approximated terms (T1, T2) with the exact stiffness and damping terms within the specified working range (parameters provided in Appendix A). According to the motion range of the deck layer of the jacket offshore platform under typical seismic loads, the applicable range of the Taylor expansion is selected as ±0.2 m. The specific results can be obtained from Section 4. The comparative outcomes are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The comparison between the exact value and the approximated value.

As can be seen from Figure 3, the approximate value obtained by Taylor expansions has a good match with the exact value within the given motion range up to ±0.2 m, which is enough for the following vibration analysis. Therefore, the dynamic motion can be simplified as,

2.2. Static Stiffness Analysis

To reduce vibration transmission, the stiffness of traditional vibration isolation systems is often adjusted to a very small value, which will reduce the load capacity of the structure and even risk collapse. The NXVIS proposed in this paper has good high static and low dynamic stiffness (HSLDS) characteristics, ensuring that the structure has sufficient load capacity while minimizing vibration transmission. To verify the HSLDS characteristics of the proposed NXVIS, static force analysis is very necessary. The functional dependence of the load force Fs on the relative displacement is expressed as

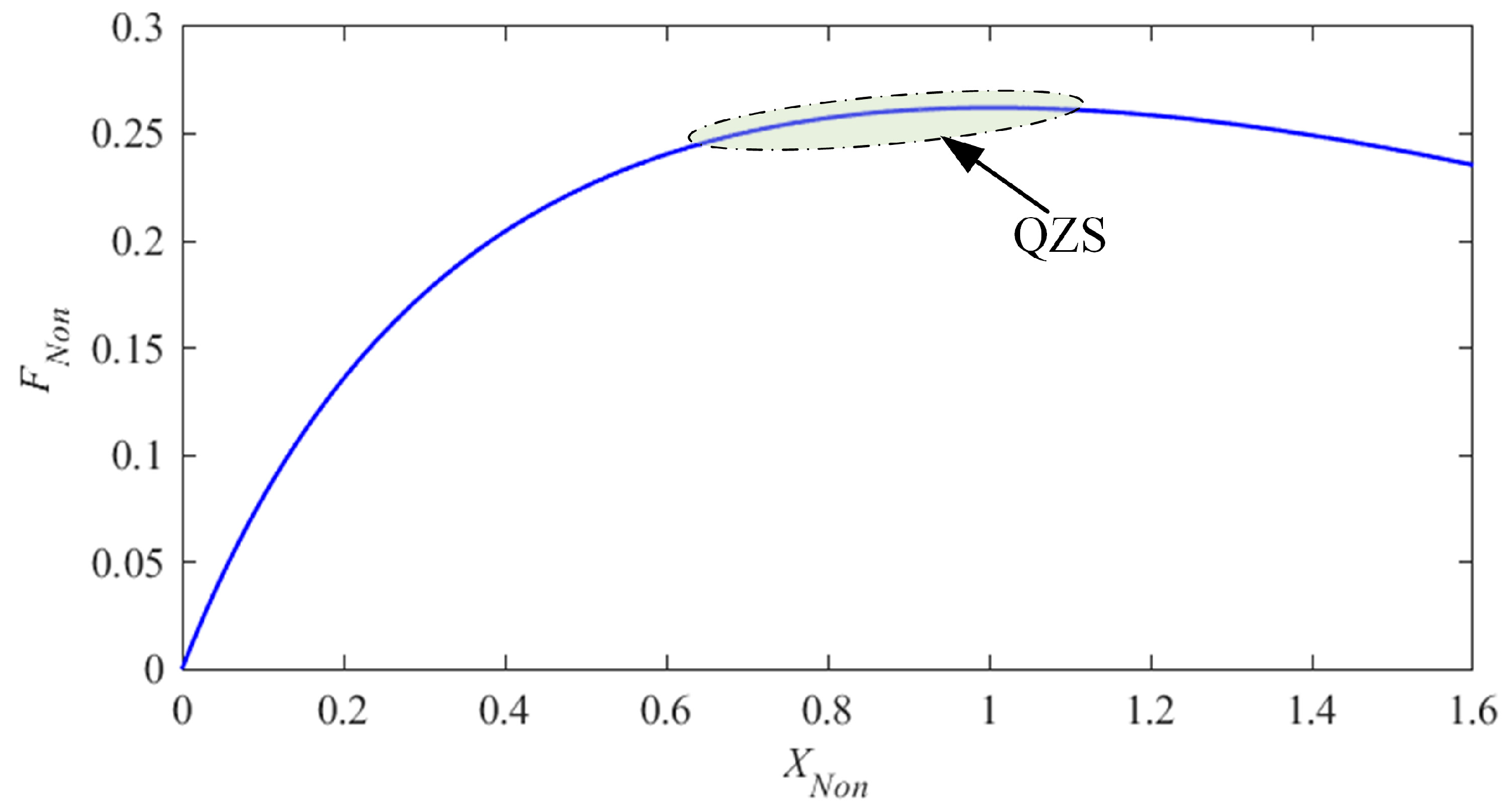

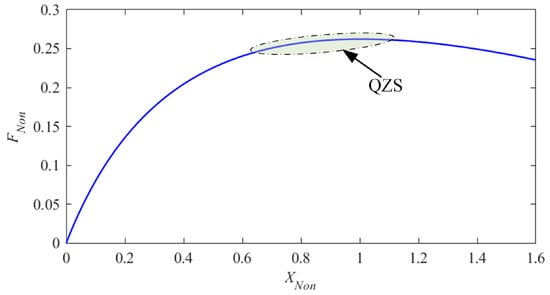

The conclusions drawn from the non-dimensional form no longer rely on a specific spring size or stiffness. As long as the non-dimensional parameters are the same, similar structures of any size will exhibit exactly the same non-dimensional force-displacement curve. Thus, the nonlinear static force is nondimensionalized and written as,

where the non-dimensional static force and the non-dimensional displacement are and .

According to Equation (8) and Appendix A, the non-dimensional static force-displacement curve of the proposed NXVIS is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Non-dimensional static force-displacement curve.

Figure 4 depicts the nonlinear relationship between the non-dimensional static load FNon and the non-dimensional displacement XNon. As XNon increases, FNon also increases, but its slope (non-dimensional static stiffness) decreases, gradually achieving quasi-zero stiffness (QZS). QZS creates a region of near-zero dynamic stiffness near the static equilibrium point, thereby resolving the fundamental challenge of traditional linear isolators in achieving both high-load and low-frequency vibration isolation. However, for vibration isolation systems, the static equilibrium position should be located within the positive stiffness range, and negative stiffness should not exist within the vibration range of the target layer. This is because negative stiffness can cause the isolator to collapse, leading to failure of the isolation system. Based on these considerations, this paper defines an indicator for evaluating the QZS: when the ratio of the non-dimensional static force FNon to the non-dimensional displacement XNon—the non-dimensional structural stiffness KNon—is less than 0.007, the corresponding region is defined as the QZS. As shown in Figure 4, when XNon = 0.7, the system enters the QZS region, where the non-dimensional stiffness approaches zero, which is ideal for vibration isolation. Considering the mass of the offshore platform deck and the definition of QZS, the angle between the isolator and the ground is set to the angle when XNon = 0.7. Furthermore, when XNon = 0.7, the load capacity M of single X-shaped isolator is 1.94 × 107 N.

To meet the design requirement (the target deck mass Mdeck is 3.1 × 104 tons), the number of X-shaped isolators Nisolator in the X-shaped vibration isolation layer can be calculated by the following formula,

where M and Mdeck are the maximum load capacity of proposed NXVIS and the target deck mass, respectively. ⌈ ⌉ represents rounding up. According to Equation (9), the number of isolators should be set to 16.

2.3. Parametric Analysis

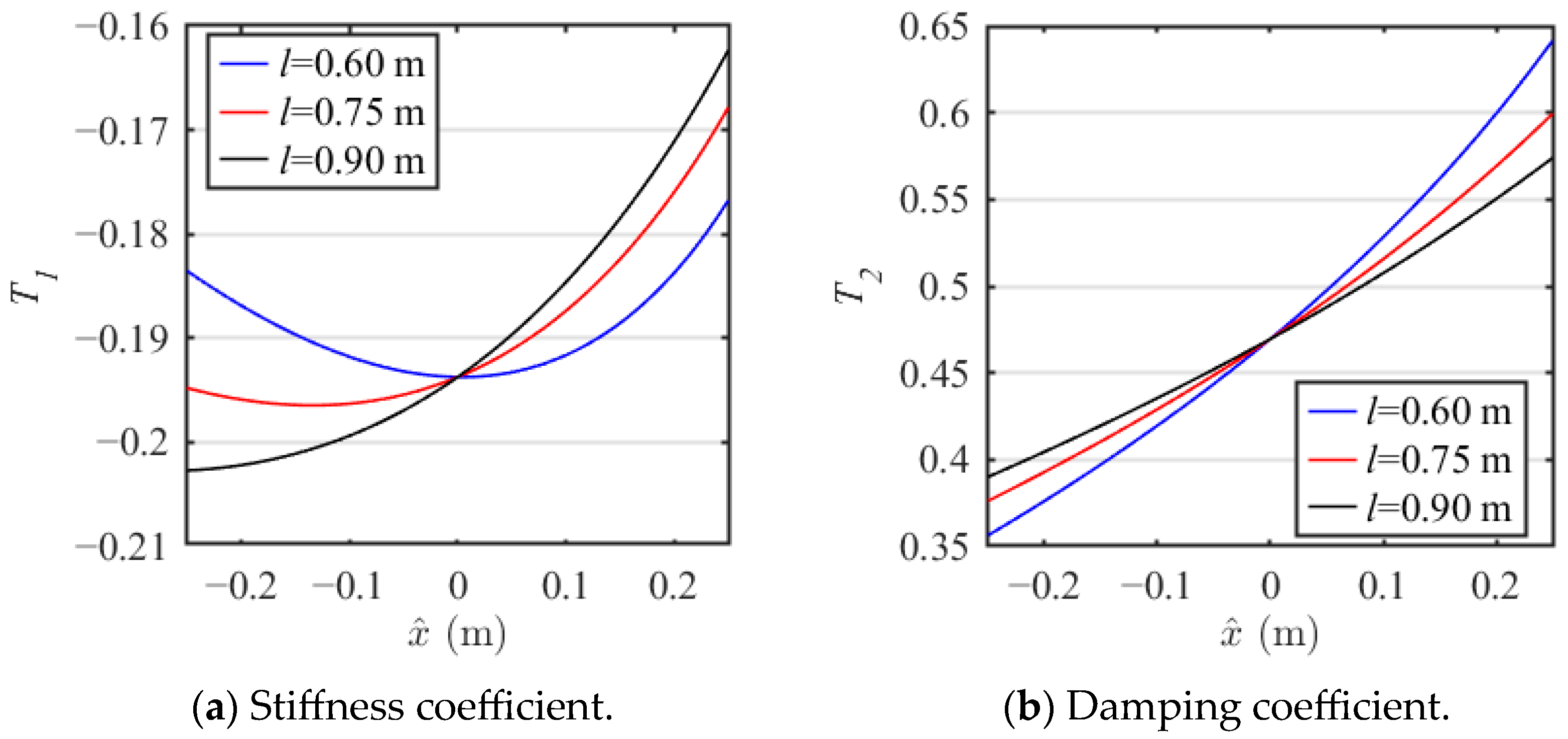

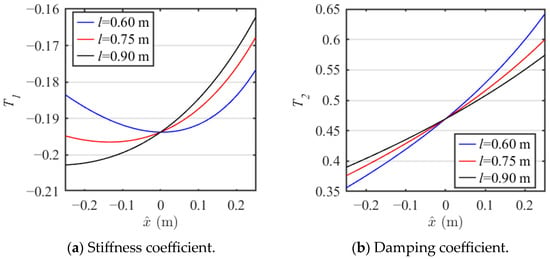

According to Equations (4) and (5), the nonlinear forces arise from a coefficient set {T1, T2}, where T1 defines the stiffness force and T2 the damping force. Both of these coefficients are governed by the common isolator parameters l, α, and n. To further understand the impact of structural parameters on the system’s nonlinearity, a parameter analysis was performed. It was assumed that when one parameter is varied, the others remain constant.

The nonlinear stiffness coefficient T1 and the nonlinear damping coefficient T2 versus displacement for bar length l ranging from 0.60 m to 0.90 m is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that the stiffness coefficient T1 and the damping coefficient T2 are constant at = 0. As bar length l increases, the stiffness coefficient T1 gradually decreases in the compression range and increases in the extension range. The nonlinearity is strongest when bar length l is small. The damping coefficient T2 exhibits an opposite relationship with bar length l as the stiffness coefficient T1.

Figure 5.

The coefficient value with different bar length l.

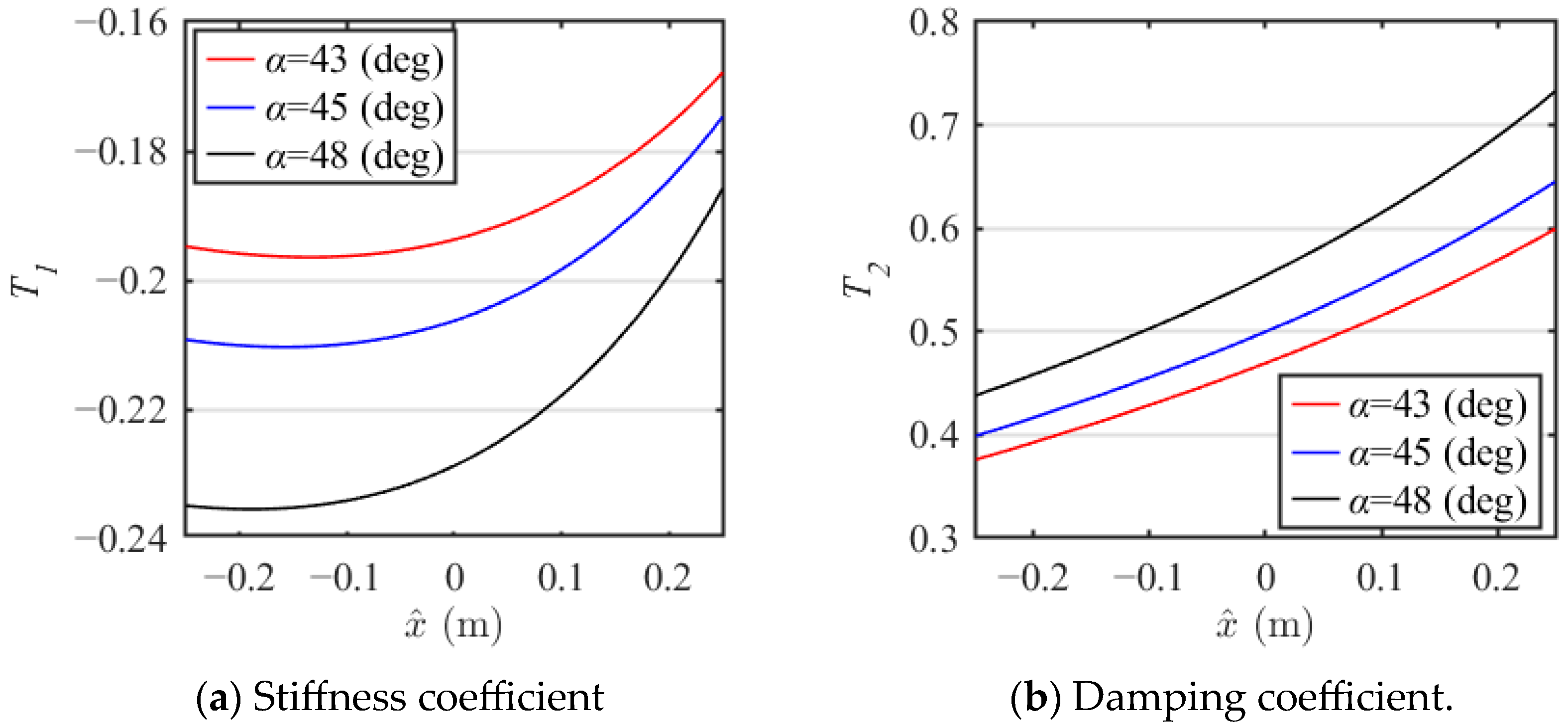

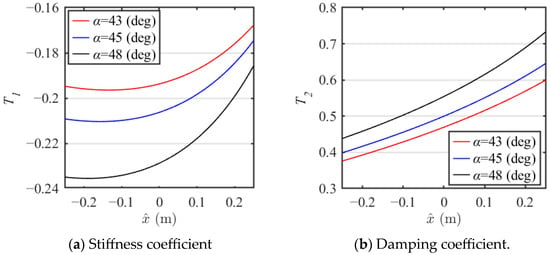

Figure 6 shows the nonlinear stiffness coefficient T1 and nonlinear damping coefficient T2 versus displacement , as the initial installation angle α changes from 43° to 48°. As can be seen, both the value and nonlinearity of the nonlinear stiffness coefficient T1 increase with decreasing angle α. This is because a smaller initial installation angle α brings the NXVIS closer to the quasi-zero range, resulting in smaller stiffness. The relationship between the nonlinear damping coefficient T2 and the initial installation angle α is opposite to that of the nonlinear stiffness coefficient T1.

Figure 6.

The coefficient value with different angle α.

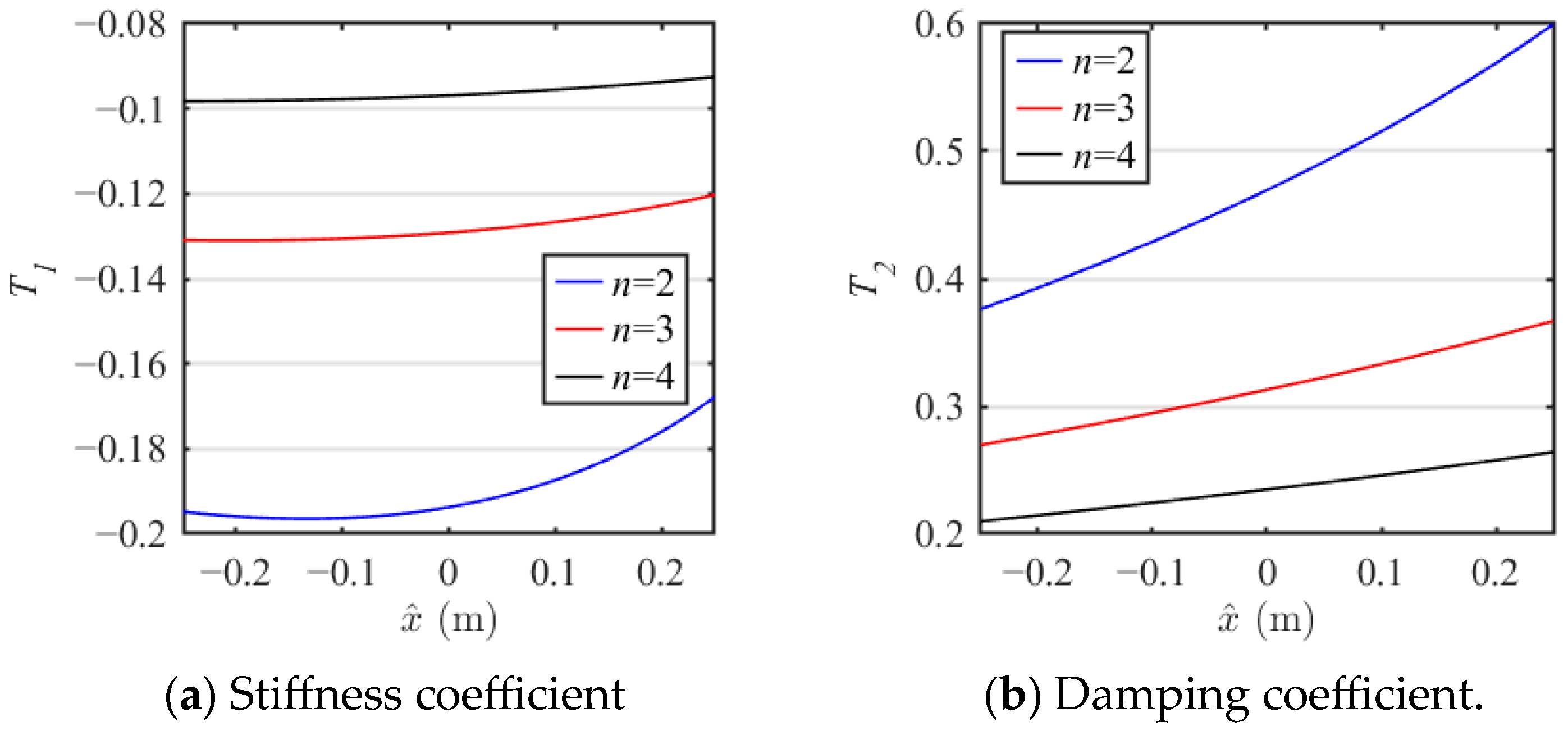

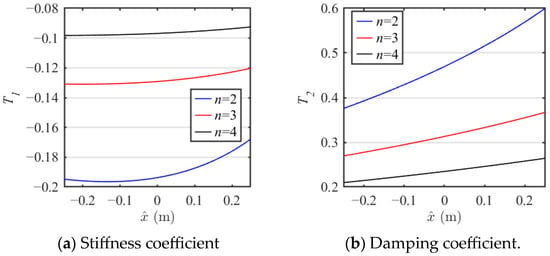

The number of layers n of the NXVIS changes from 2 to 4, and the nonlinear stiffness coefficient T1 and the nonlinear damping coefficient T2 with respect to the displacement are shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that with the increase in the number of layers n, the value of coefficient T1 rises significantly, but the nonlinearity decreases. The nonlinear damping coefficient T2 exhibits an opposite relationship to the nonlinear stiffness coefficient T1, but the rate of change is increasing with decreasing layer number n.

Figure 7.

The coefficient value with different layer number n.

From Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, it can be concluded that changes in the bar length l, initial installation angle α, and number of layers n can all lead to corresponding changes in the nonlinear stiffness coefficient T1 and the nonlinear damping coefficient T2. In particular, the bar length l causes the nonlinear stiffness coefficient T1 to produce significant nonlinear characteristics, which is conducive to optimizing stiffness. This also shows that parameter adjustments of the NXVIS will produce a special dynamic response under external excitation, thereby achieving a better passive vibration isolation effect by optimizing the structural parameters. An ideal vibration isolation system requires low stiffness and appropriate damping while ensuring sufficient load capacity.

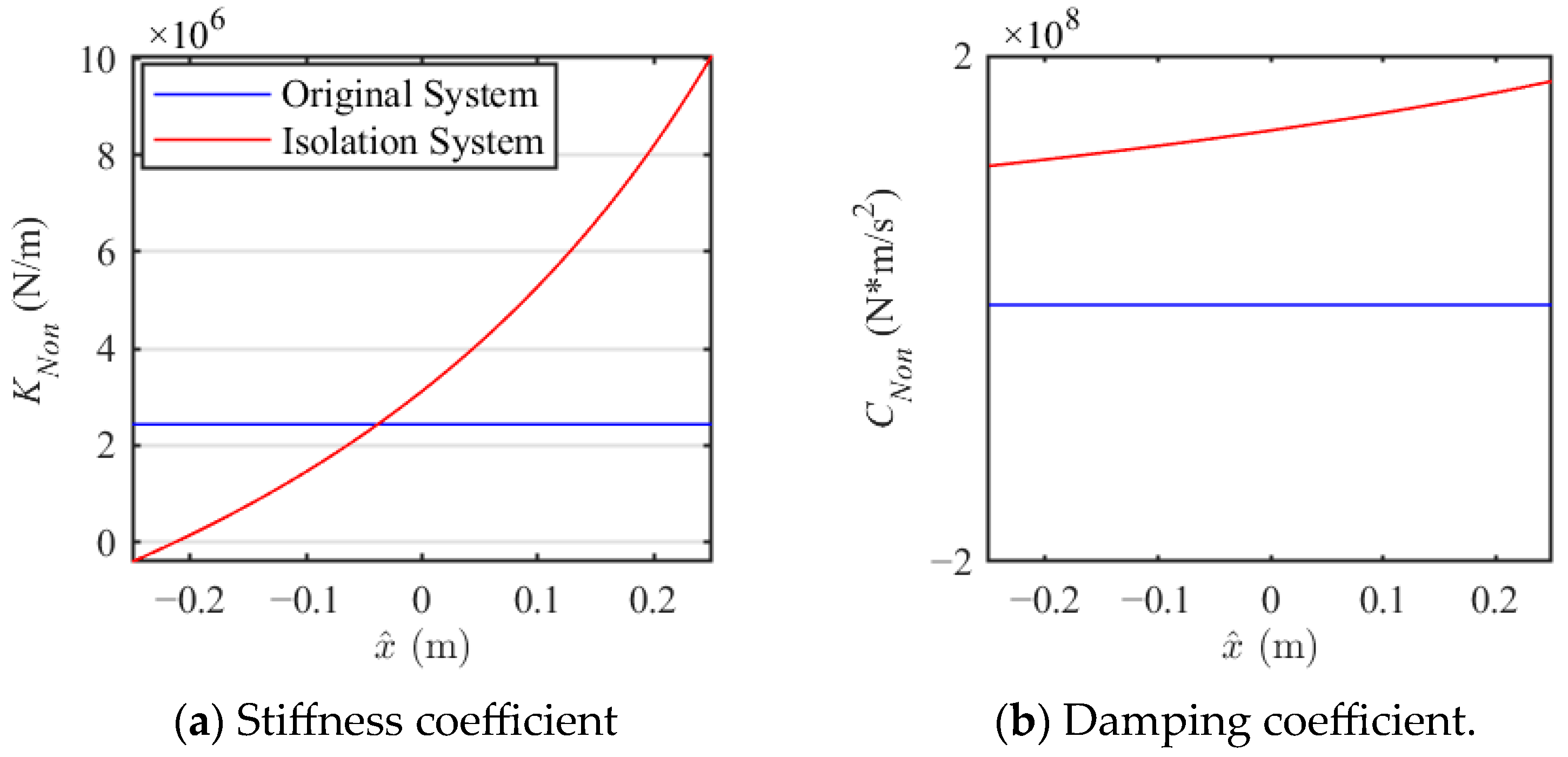

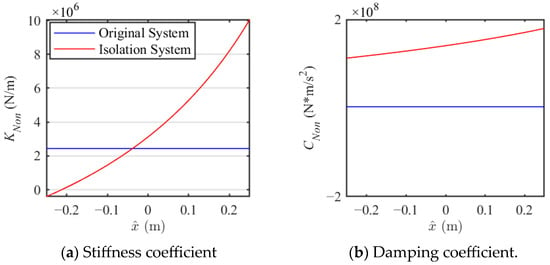

The comparison of the stiffness and damping characteristics of the original system and the NXVIS, as shown in Figure 8. The nonlinear stiffness and damping of the isolation system in this figure represent the stiffness and damping of a single isolator. Similarly, the stiffness and damping of the original system are divided by 16. As can be seen from Figure 8, the stiffness and damping of the original system remain constant throughout the entire motion range of the isolation layer, while the stiffness and damping of the isolation system with NXVIS vary throughout the entire motion range. This allows the isolation system to provide greater static stiffness at static equilibrium, maintaining overall structural stability. During relative motion, it provides less dynamic stiffness and greater dynamic damping, reducing transmission of vibration and dissipating vibration energy.

Figure 8.

The comparison of coefficients of different schemes.

2.4. Displacement Transmissibility

To evaluate and verify the anti-vibration performance of the proposed NXVIS, the harmonic balance method is employed to obtain the transmissibility of the system. According to the dynamic Equation (6), it is assumed that the base excitation is expressed as,

where z0, ω and are the amplitude, frequency and initial phase of the excitation signal, respectively.

The solution of the dynamic equation is assumed as,

where x0 and are the motion amplitude and phase angle. The and x0 in Equations (10) and (11) can be determined using the following equations,

Based on Equations (12) and (13), the value of and x0 can be derived. So, the displacement transmissibility Td can be obtained by,

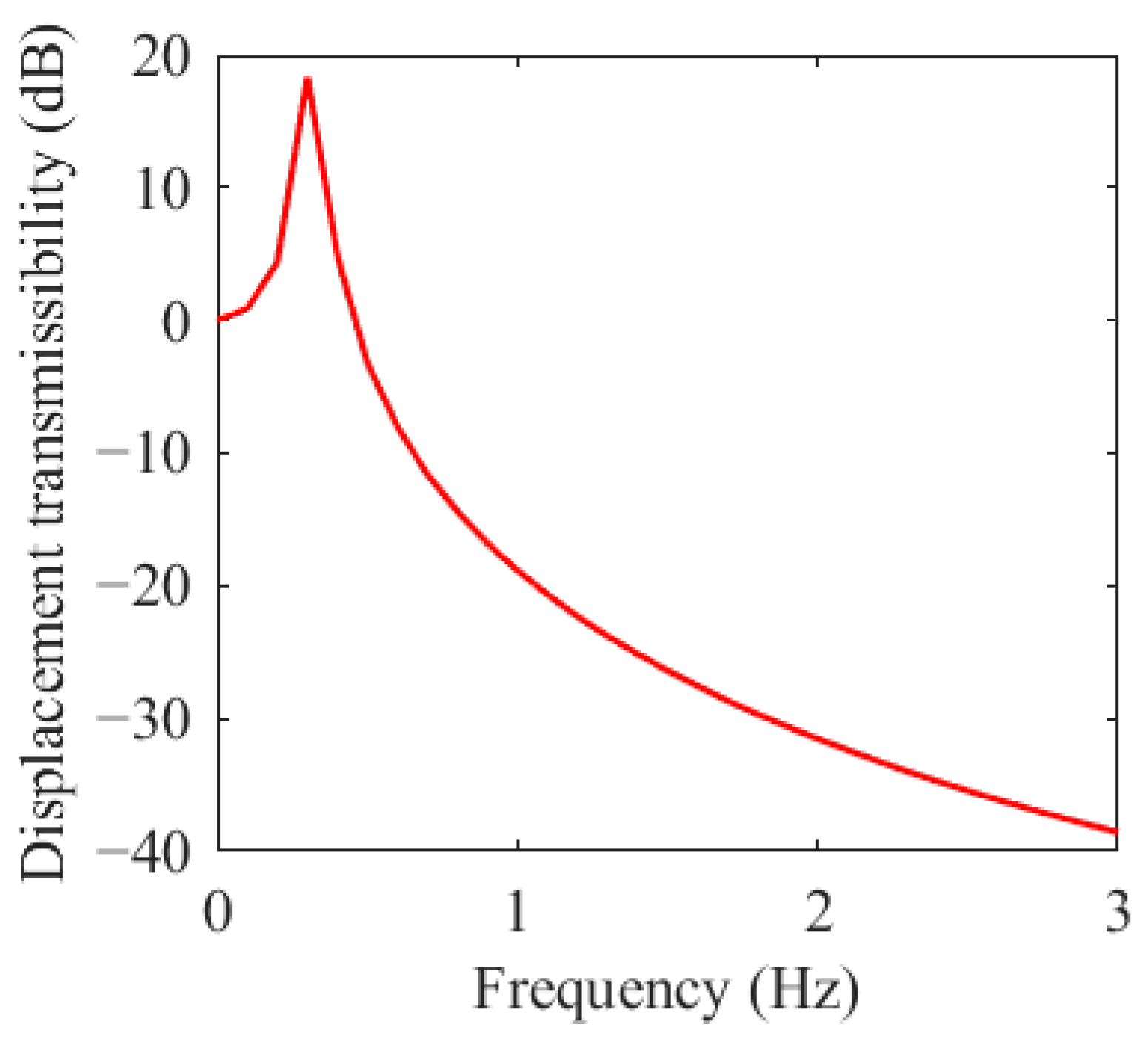

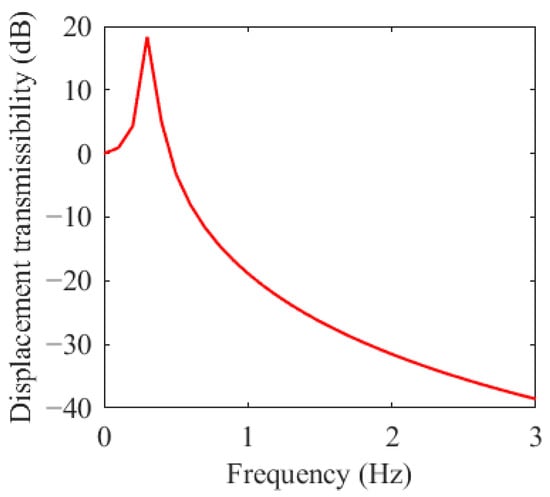

Based on the parameters in Appendix A and Equation (14), the transmissibility of the NXVIS is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The displacement transmissibility of the proposed NXVIS.

Earthquakes are generally considered to be a predominantly low-frequency excitation. While the energy released by an earthquake encompasses a wide frequency range, its frequency distribution shows that the vast majority is concentrated between 0.7 Hz and 3.0 Hz. This is the primary cause of severe damage to high-rise buildings and long-period structures (such as jacket platforms, suspension bridges and supertall buildings) during large earthquakes. Figure 9 shows that the system’s resonant frequency is 0.3 Hz. Once the frequency surpasses 0.4 Hz, the system transitions into its vibration attenuation zone, confirming the proposed isolation mechanism’s capacity for effective ULF vibration control under seismic conditions loads.

3. Jacket Platform with Nonlinear Vibration Isolation System

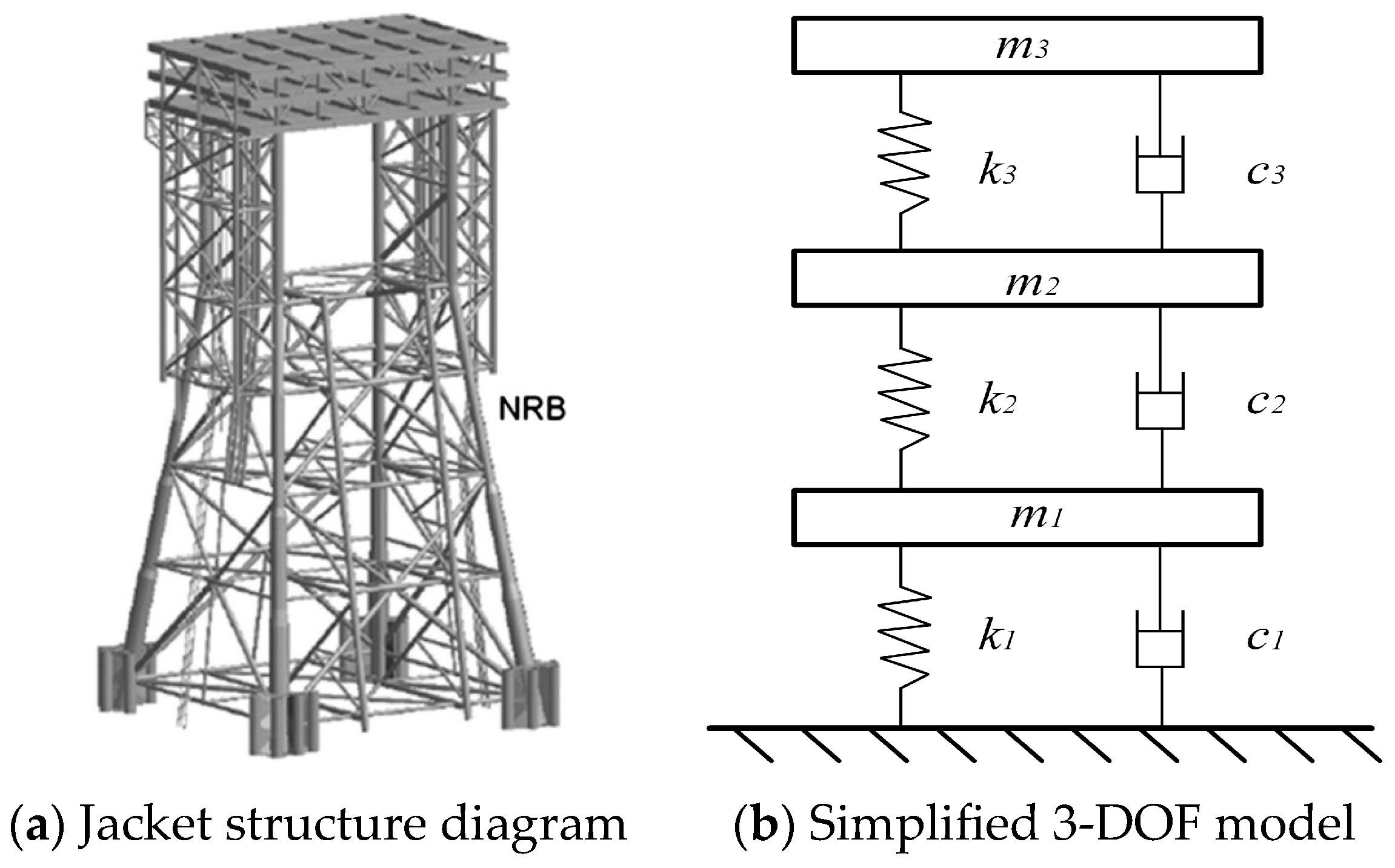

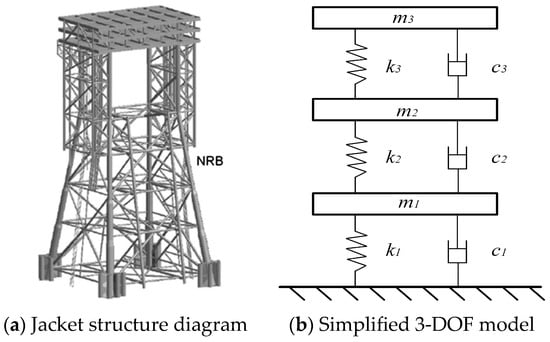

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed nonlinear X-shaped vibration isolation system for jacket offshore platforms, a real offshore platform (North Rankin B’ (NRB’)) [3] was selected for X-shaped vibration isolation system design and numerical analysis, as shown in Figure 10a. The NRB’ platform is a major offshore gas platform located approximately 135 km northwest of Dampier, Western Australia. The platform carries out jacket installation, platform hoisting and submarine pipeline laying in a water depth of 125 m, representing the high technical level of offshore engineering at that time. It was primarily constructed to develop the low-pressure gas reserves of the Rankin field, which the original North Rankin A’ (NRA’) platform could no longer efficiently extract. The platform is physically connected to the NRA’ platform by a 100 m bridge, creating the integrated Rankin A’B’ hub. This allows for shared utilities and accommodation. With a topsides weight of over 30,000 tons, NRB’ can process up to 1.6 billion standard cubic feet of gas per day. For the convenience of simulation analysis, an idealized 3-DOF system is regarded as a simplified model of the platform by the model reduction method (as shown in Figure 10b). Table 1 lists some dynamic characteristics of the platform model, such as the stiffness of each layer and the lumped mass values.

Figure 10.

The NRB’ jacket offshore platform.

Table 1.

Parameters of NRB’ platform [3].

The damping matrix for the NRB’ platform is formulated using Rayleigh damping coefficients, derived from the modal damping ratios associated with the first two frequencies [3]. The damping ratios of the first three vibration modes are set to 0.05, 0.03, and 0.02, respectively [3]. Based on the simplified structural model of the jacket platform, the governing dynamic equation is given by,

where , and are mass, damping and stiffness matrices of the simplified 3-DOF model, respectively; and , and are the vectors of displacement, velocity and acceleration of structural response, respectively. is the earthquake acceleration signal. According to Equation (15), the displacement and acceleration of deck layer of NRB’ platform can be calculated.

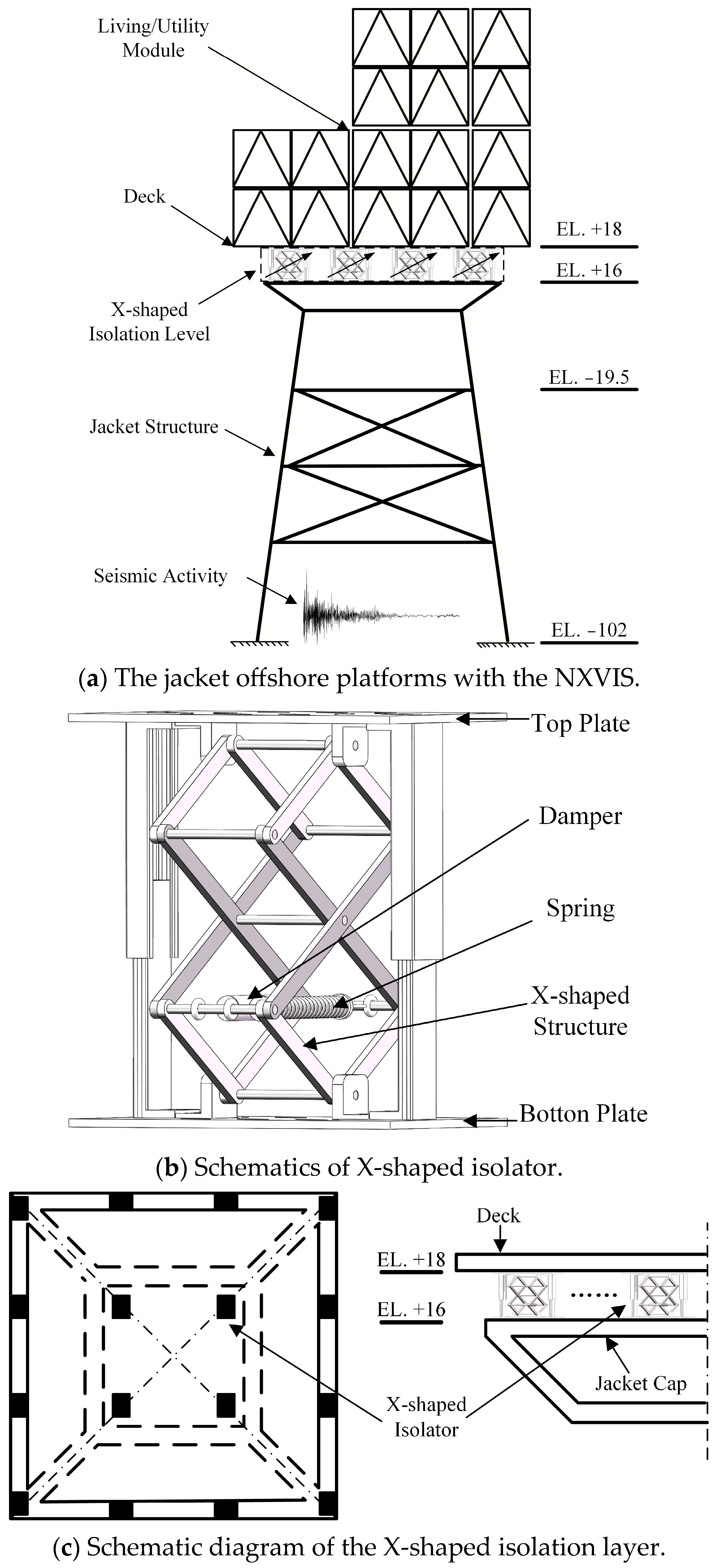

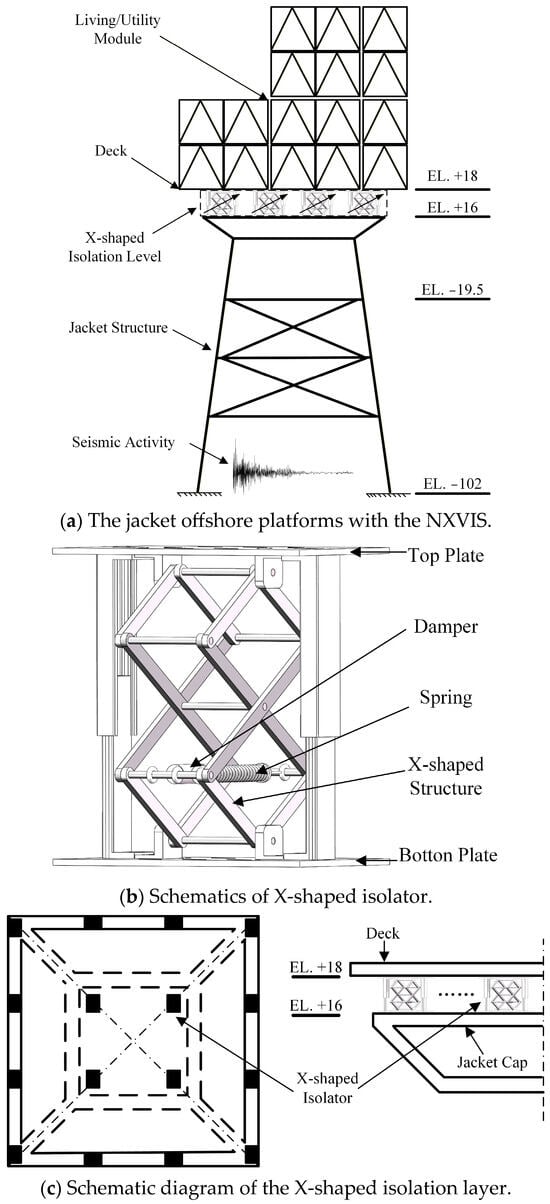

The proposed vibration isolation system for jacket offshore platforms places an NXVIS between the deck and the jacket structure of NRB’ platform, as shown in Figure 11a. To avoid excessively increasing the overall height of the NRB’ platform and thus introducing unforeseen risks, the bar length l of the X-shaped isolator is set to 0.75 m, which makes the height of the NXVIS only about 2 m. The X-shaped isolator’s primary function is to carry the upper load and achieve vibration isolation through nonlinear dynamic stiffness and damping. The structure of the X-shaped isolator is shown in Figure 11b. However, the X-shaped isolator corresponding to a bar length l of 0.75 m cannot bear the weight of the deck layer alone. Considering the weight of the deck and the QZS range of the system, 16 isolators were selected and evenly distributed in the nonlinear X-shaped isolation layer. Figure 11c shows the installation details of the X-shaped isolation layer. Figure 11c shows the installation details of the X-shaped isolation layer. As shown in Figure 11c, sixteen isolators are installed evenly between the jacket cap and the deck. This configuration results in the NXVIS being positioned between 16 and 18 m above the water surface. The X-shaped isolation layer not only isolates vibration transmission but also provides a compliant, localized deformation layer between the jacket structure and the deck, making the isolator in a QZS range. The validation of passive vibration isolation layers has been discussed previously [3]. Conventional vibration isolation approaches are frequently tailored to environmental load profiles. Consequently, their adaptability is generally deficient, and their efficacy in handling the intricacies of complex maritime environments—especially broadband excitations—remains limited. The proposed NXVIS can achieve ULF and wide-band vibration isolation under high loads, enabling the offshore platform to cope not only with low-frequency wave loads but also with wide-band seismic loads. The vibration isolation characteristics of the NXVIS have been verified in Section 2, demonstrating its effectiveness in reducing vibrations within the frequency band above 0.4 Hz. In addition, the NXVIS can dissipate vibration energy through its damping properties. Although low-frequency wave loads constantly cause platform vibration, seismic loads are the primary threat to platform safety, especially for jacket offshore platforms located in seismic zones. Therefore, this study focuses on vibration control of jacket offshore platforms under seismic loads.

Figure 11.

Nonlinear X-shaped vibration isolation system.

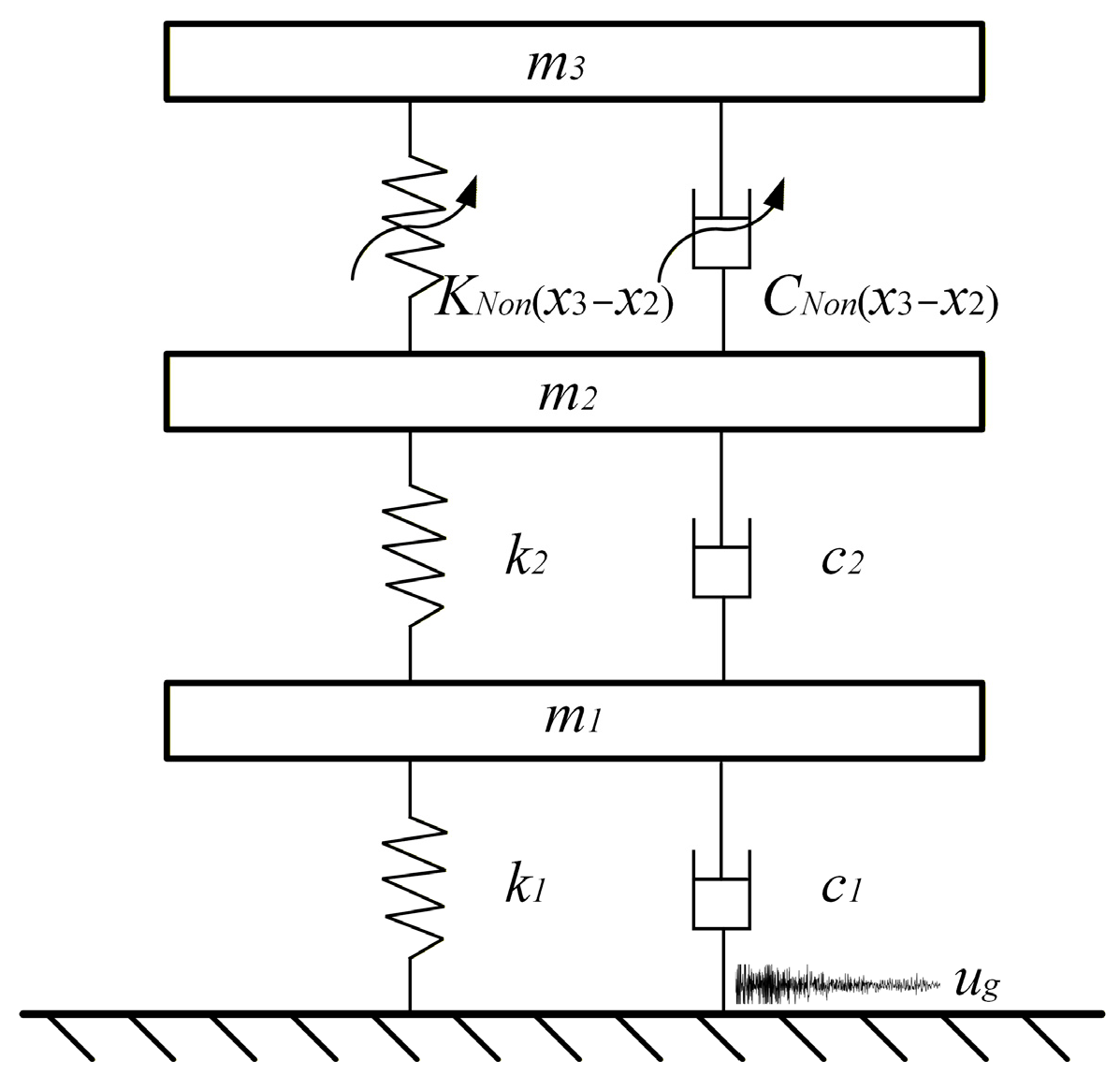

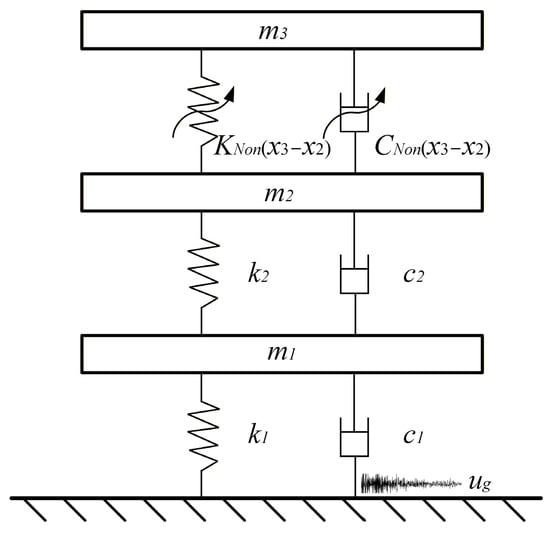

Based on the dynamic characteristics of the NRB’ platform and the designed NXVIS, a simplified 3-DOF platform with NXVIS is shown in Figure 12. In Figure 12, KNon and CNon are the dynamic stiffness and damping related to the relative displacement between layers, which can be expressed as

where x2 and x3 are the absolute displacements of the second and third layers of the NRB’ platform, respectively. The coefficients are listed in the Appendix B. The Taylor expansion coefficients can be obtained from Appendix B. Since the NXVIS has strong nonlinearity, the Lagrangian method is used to solve the dynamic equation of the simplified 3-DOF platform with NXVIS. The nonlinear dynamic equation of the NRB’ platform with NXVIS (as shown in Figure 12) can be written as

where mi, ki and ci are NRB’ platform mass, stiffness and damping coefficient of the ith floor (i = 1–3), respectively. xi represents the displacement of the ith floor relative to ground motion, respectively. k0 and c0 are the fixed stiffness and damping coefficients (constant values) of the spring and damper in the proposed X-shaped anti-vibration structure, respectively, and their values can be found in Appendix A. The actual stiffness and damping coefficients (dynamic values) of NXVIS are dynamic stiffness and damping coefficients determined by the inter-layer relative displacements x2 and x3, which can be found in Equations (16) and (17). In addition, the gravity term in Equation (20) cancels out the elastic force in the spring caused by gravity. Therefore, the dynamic response of the structure will still fluctuate around the static equilibrium position (zero position). The values of the remaining parameters are provided in Appendix A.

Figure 12.

The NRB’ platform with NXVIS.

4. Results and Discussion

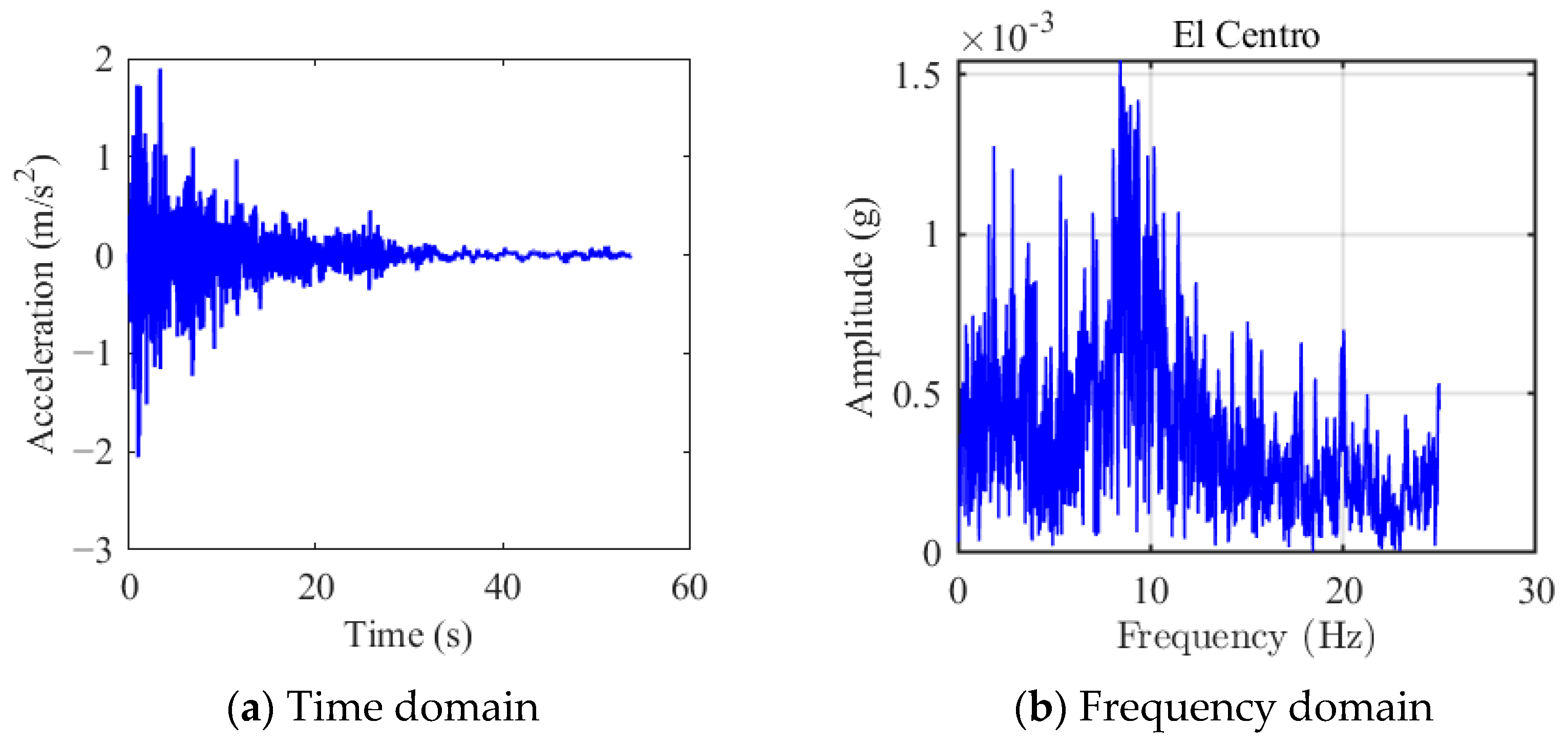

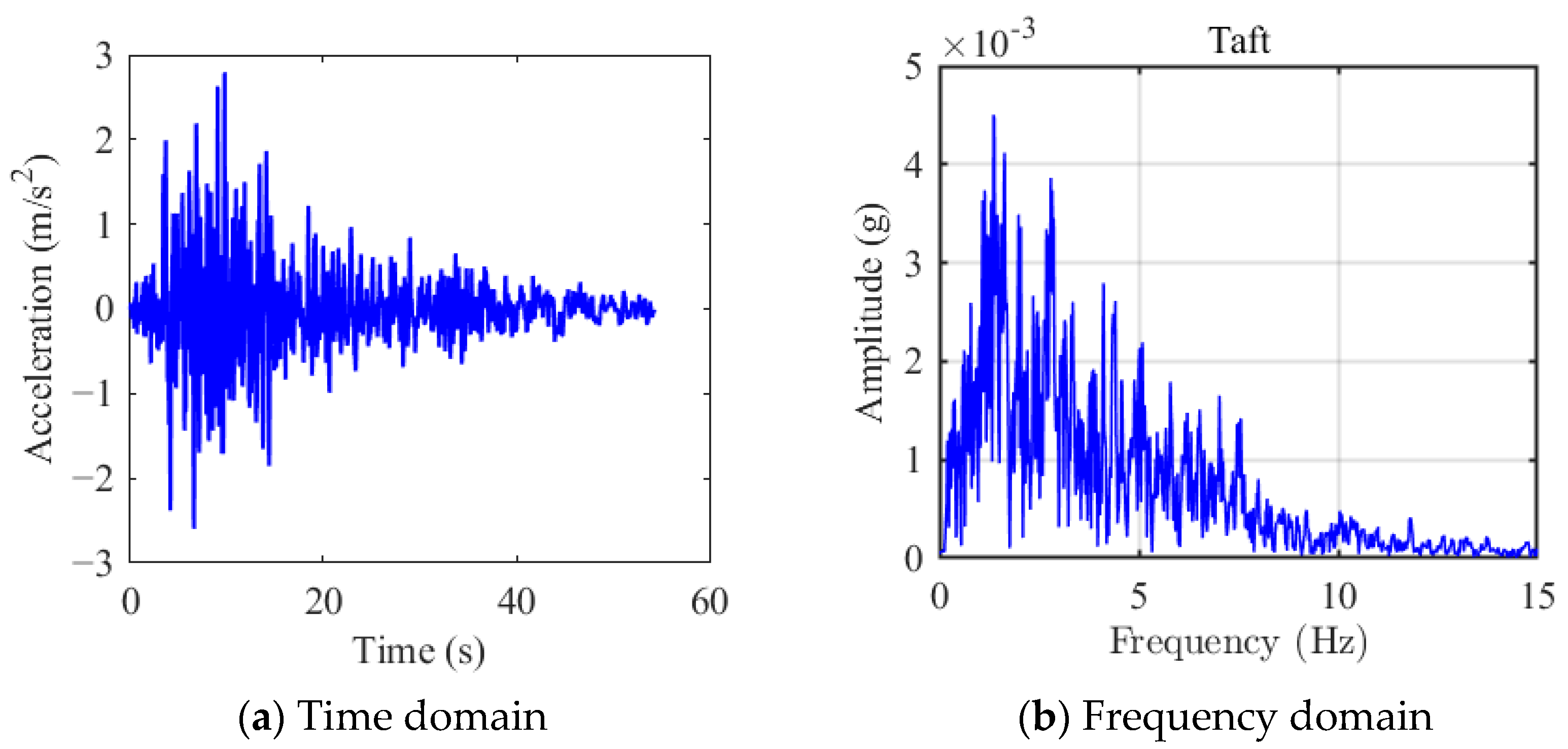

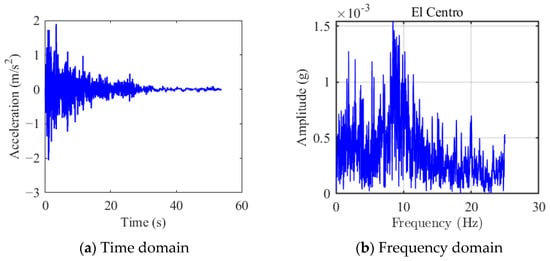

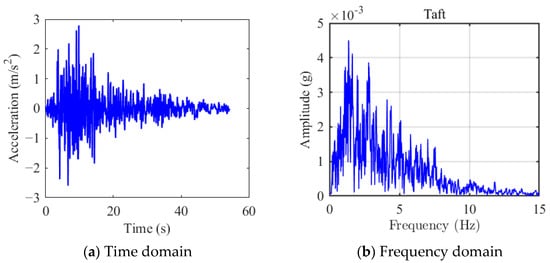

To fully validate the effectiveness of the proposed NXVIS, the NRB’ platform in Western Australia was selected for numerical analysis, which is a very important and representative offshore natural gas production platform. Similarly, to ensure the objectivity of the numerical analysis results, two typical seismic loads (El Centro, 1940; Taft, 1952) were considered, as shown in Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 13.

El Centro seismic load.

Figure 14.

Taft seismic load.

Figure 13 shows the Imperial Valley earthquake of 18 May 1940, known as the El Centro earthquake. It is one of the most famous and widely used seismic loads in the world and is a very representative example. Figure 13a shows that the seismic signal initially has concentrated energy and a large response amplitude, but the energy gradually decays over time. Figure 13b shows the El Centro earthquake in the frequency domain. The earthquake has two frequency peaks, at 1.88 Hz and 8.43 Hz, with the major energy concentrated between 1.0 Hz and 10.0 Hz. This indicates that larger earthquakes release more low-frequency energy, and vibration control for jacket offshore platforms should primarily address these extreme seismic loads.

Figure 14 shows the seismic acceleration recorded at a seismic station in Taft, California, during the 1952 Kern County earthquake, known as the Taft earthquake. It is one of the earliest fully documented strong earthquake records in the world. Due to its high data quality and typical characteristics, it has become a standard seismic load recognized by international society, widely used in seismic performance testing of structures such as buildings, bridges, and nuclear power plants. As shown in Figure 14b, the Taft seismic load peaks at 1.38 Hz, with most of its energy concentrated between 0.8 Hz and 5.0 Hz.

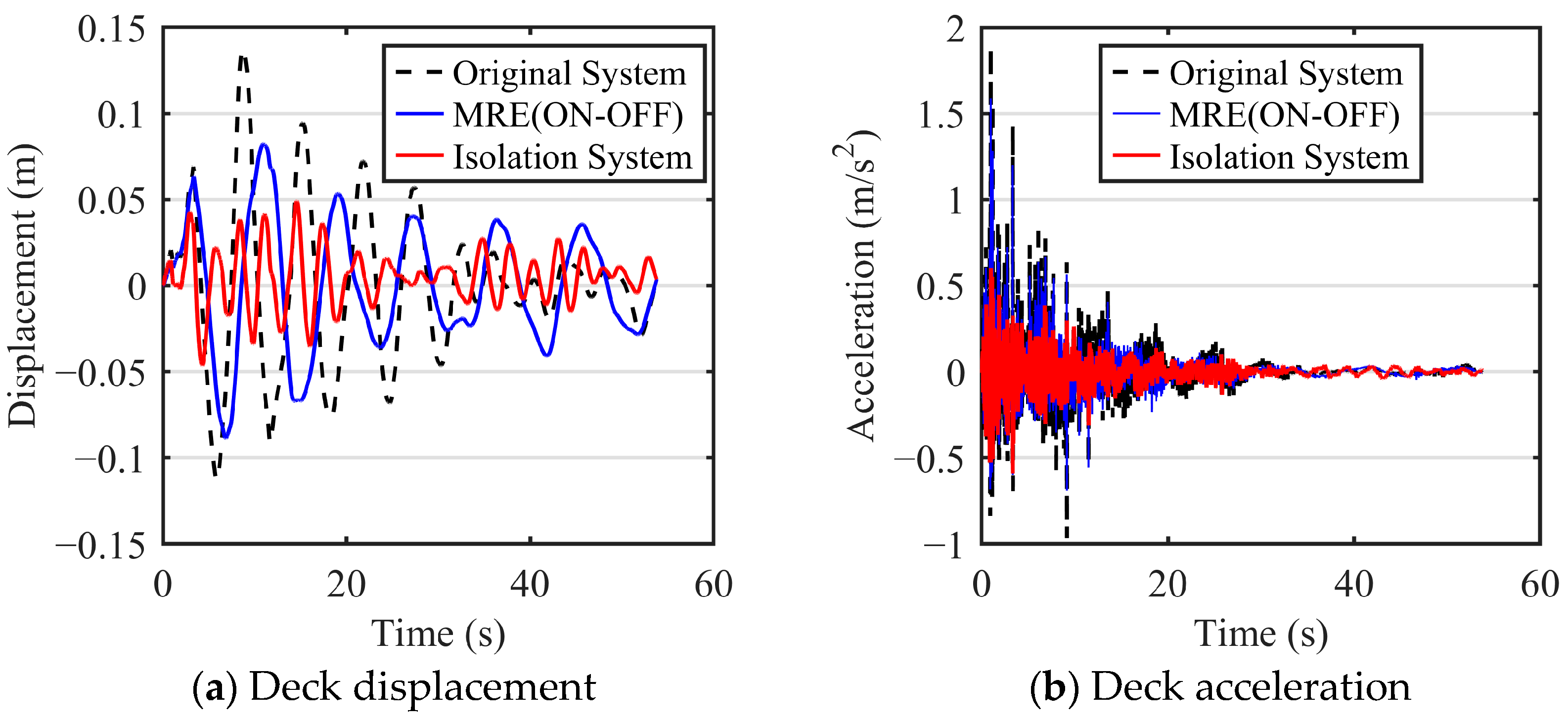

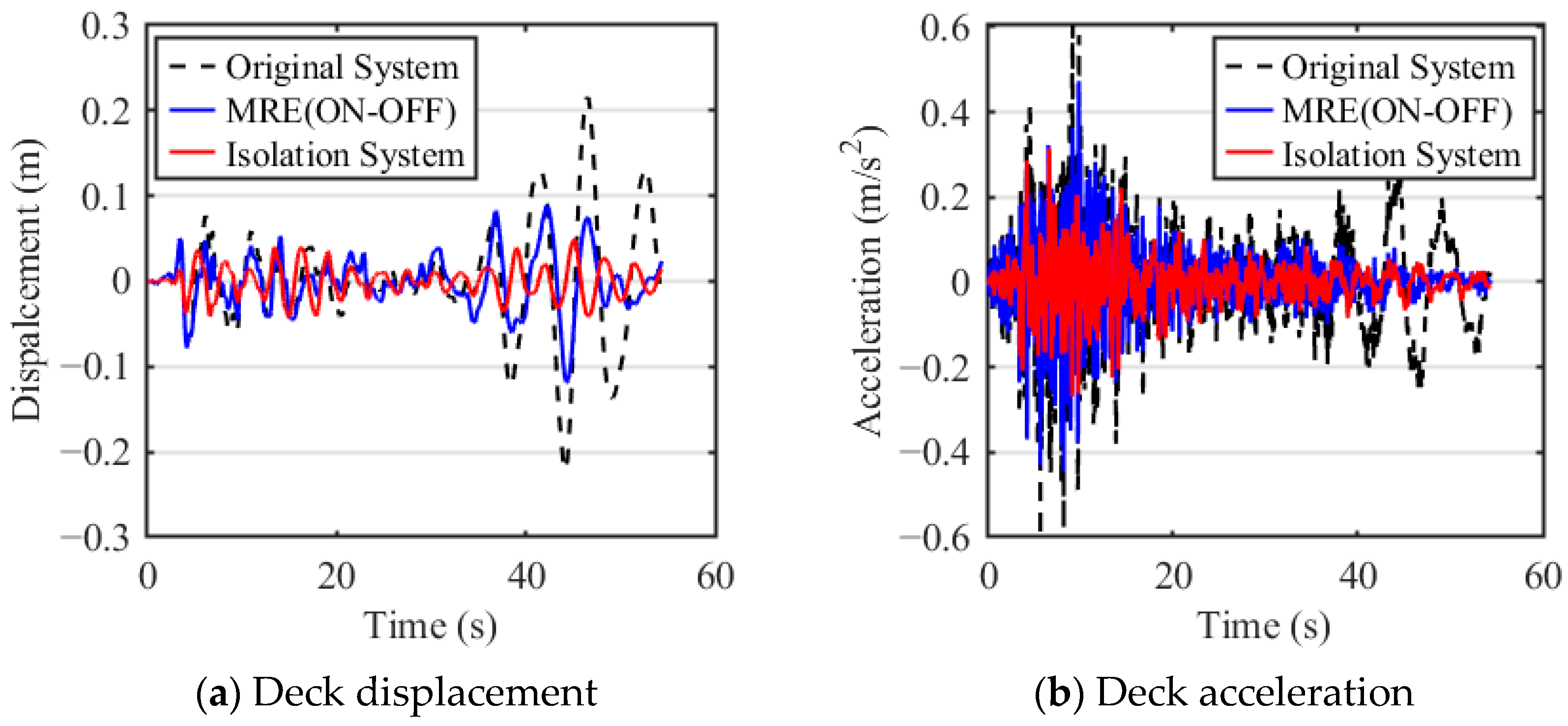

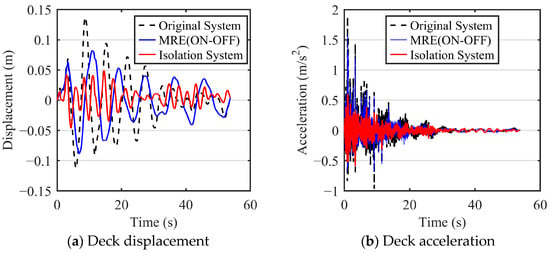

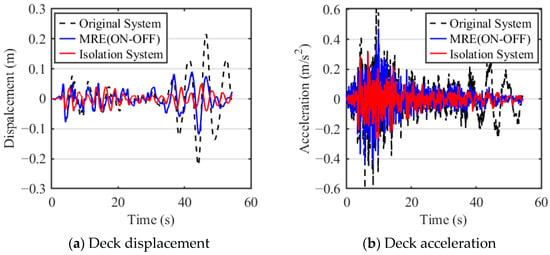

These two types of seismic loads are highly representative, characteristic, and widely applicable, and therefore can well reflect the effectiveness of vibration isolation solutions. Based on these two typical seismic loads and the dynamic model of an NRB’ offshore platform with an X-shaped anti-vibration structure, a numerical analysis of the offshore platform’s vibration performance was conducted. The deck is a crucial area of offshore platforms for oil and gas production and crew life. The displacement response of the deck can cause structural fatigue damage and equipment damage, and in severe cases, even cause the platform to capsize, resulting in significant losses. The acceleration response of the deck can affect staff comfort and the operation of sensitive equipment, ultimately impacting production efficiency and worker health. Therefore, this study focuses on analyzing the structural response of the deck. The results are presented in Figure 15 and Figure 16. It should be clarified that the “Original System” denotes the NRB’ platform without any anti-vibration mechanisms, MRE (ON-OFF) refers to the NRB’ platform with an MRE isolation layer with on–off control (for specific parameters, see Reference [3]), while the “Isolation System” refers specifically to the platform integrated with the NXVIS.

Figure 15.

Dynamic response of the NRB platform deck under El Centro seismic excitation.

Figure 16.

Dynamic response of the NRB platform deck under Taft seismic excitation.

Figure 15 and Figure 16 show that the NRB’ jacket offshore platform equipped with a NXVIS can significantly reduce the displacement and acceleration response of the deck under seismic loads. Figure 15 shows the displacement and acceleration response of the deck under the El Centro earthquake load. The maximum displacements of the deck with and without the NXVIS are 4.9 cm and 13.7 cm, respectively, with a reduction by 64.23%. The peak deck accelerations were measured at 0.602 m/s2 and 1.883 m/s2, corresponding to a significant reduction of 68.03%. Figure 16 presents the displacement and acceleration time histories of the deck subjected to Taft seismic excitation. The peak deck displacements with and without the NXVIS were measured at 4.9 cm and 21.6 cm, respectively, corresponding to a significant reduction of 77.31%. The peak deck accelerations reached 0.315 m/s2 and 0.604 m/s2, representing a substantial reduction of 47.85%. This demonstrates that the NXVIS can achieve effective vibration reduction within the seismic frequency band by changing the system’s natural frequency. In addition, the result also shows that, under El Centro seismic excitation, the RMS deck displacement and acceleration of the NXVIS are 49.31% and 14.56% lower than that of the MRE isolation system. Under Taft seismic excitation, the RMS deck displacement and acceleration of the NXVIS are 46.11% and 25.37% lower than that of the MRE isolation system. This favorable comparison not only strengthens the validation of our proposed approach but also highlights its remarkable potential as a highly effective, energy-free, and reliable solution for the seismic protection of offshore platforms. For quantitative comparison, Table 2 lists the maximum, minimum, and RMS values of the performance indicators under different systems (original system and isolation system) and seismic loads (El Centro Earthquake; Taft Earthquake).

Table 2.

Deck layer responses under different systems.

As shown in Table 2, compared to offshore platforms without NXVIS, offshore platforms equipped with NXVIS significantly reduce deck vibration response under seismic loads, with the maximum reduction reaching 81.08%. Under seismic excitation from both the El Centro and Taft records, the NXVIS achieved substantial reductions in the root mean square (RMS) deck acceleration values, amounting to 32.41% and 53.12%, respectively. Deck acceleration serves as a critical metric for assessing the vibrational performance of marine vessels and offshore structures, with direct implications for crew comfort, as well as the operational safety and reliability of sensitive on-board equipment. Notably, under both loading scenarios, the peak, minimum, and RMS acceleration values of the deck equipped with the NXVIS were consistently reduced compared to the original platform, confirming the system’s superior vibration suppression performance. The minimum deck acceleration under both load conditions was reduced by 32.41% and 53.12%, respectively. This is because the natural mode of the original NRB’ platform is closer to the main earthquake frequency band, making it more susceptible to resonance. However, the offshore platform with the NXVIS can dynamically adjust the system stiffness, achieving effective vibration isolation within the external excitation frequency band, thereby effectively suppressing the vibration response.

It should also be noted that the system stiffness of the isolation layer is relatively low, which generally reduces the acceleration response while increasing the relative motion between deck and jacket structure. This increase in relative displacement may affect the stability of equipment installation and system durability. However, the offshore platform with the NXVIS significantly reduces the relative displacement of the structure while maintaining better acceleration control. This is because nonlinear systems can achieve HSLDS characteristics. For example, under two seismic loads, the RMS value of the deck displacement was reduced by 57.78% and 73.53%, respectively, demonstrating the significant advantage of this control strategy in improving overall stability. This outcome further verifies that the proposed nonlinear isolation approach successfully reconciles the response interplay between acceleration and displacement while surpassing conventional linear passive isolation methods in overall vibration suppression effectiveness, highlighting its potential for practical deployment in offshore platforms vibration mitigation.

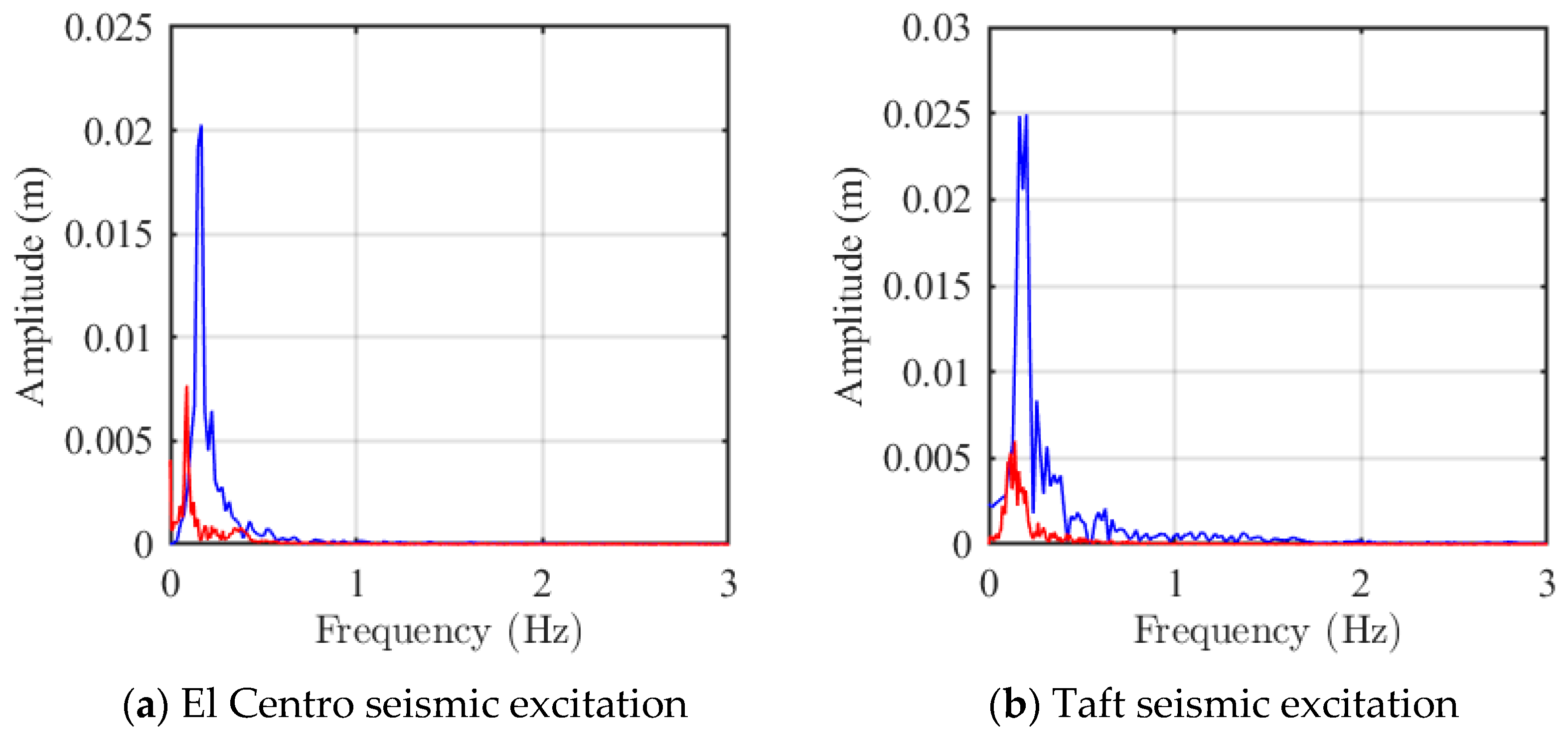

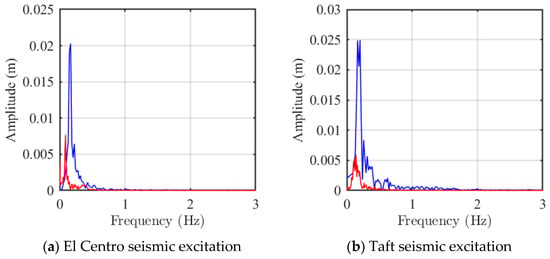

To gain deeper insight into the vibration isolation mechanism of the NXVIS in the frequency domain, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis was performed on the deck displacement responses under both El Centro and Taft seismic excitations. The resulting spectra are presented in Figure 17a (for El Centro) and Figure 17b (for Taft).

Figure 17.

Frequency domain analysis.

The frequency domain analysis reveals the fundamental working principle of the NXVIS. A consistent and critical trend is observed under both seismic records: the platform equipped with the NXVIS exhibits its dominant response frequency shifted to a lower band, accompanied by a substantial reduction in the corresponding spectral peak amplitude.

Specifically, under El Centro excitation, the dominant frequency of the original platform is 0.16 Hz with a peak amplitude of 0.020 m. In contrast, the NXVIS-isolated platform shifts this dominant frequency down to 0.08 Hz and drastically reduces the peak amplitude to 0.0077 m. A similar and even more pronounced effect is observed under the Taft record, where the dominant frequency shifts from 0.16 Hz to 0.10 Hz, and the peak amplitude is reduced from 0.025 m to a mere 0.006 m.

This dual effect of frequency shifting and amplitude suppression is the hallmark of effective base isolation. NXVIS successfully moves the fundamental frequency of the isolated system far below the dominant energy-containing frequencies of the seismic inputs (typically 0.7–3.0 Hz) and the original platform’s fixed-base frequency. This detuning effect is the primary reason for the drastic reduction in resonant response. Furthermore, the significant attenuation of the spectral peak amplitude directly quantifies NXVIS’s capacity to limit the energy transfer to the deck at the most critical frequencies, which aligns perfectly with the dramatic reductions observed in the time-domain responses (Figure 15 and Figure 16).

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a biomimetic nonlinear X-shaped vibration isolation system, inspired by the X-shaped supporting structure of the human leg, to mitigate vibrations of jacket offshore platforms under the action of seismic loads. The NXVIS demonstrates superior tunable stiffness, adaptive damping characteristics, and high load-bearing capacity, with all three properties being programmable through strategic configuration of its structural parameters. To verify the effectiveness of the proposed nonlinear X-shaped vibration isolation system for vibration control of offshore platform under the action of seismic loads, theoretical and numerical analyses were conducted on the dynamic response of the NRB’ offshore platform located in the waters of Western Australia under two typical seismic loads. The principal findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

- System modeling and theoretical analysis demonstrate that the NXVIS exhibits distinct nonlinear quasi-zero stiffness, nonlinear damping, and high load capacity, enabling ULF with minimal peak values and high vertical load capacity. This design provides tunable load-bearing and frequency response characteristics—a significant advantage over traditional passive isolation methods—allowing precise adaptation to specific platform requirements and complex marine loading scenarios.

- By modulating key structural parameters, including bar length and spring stiffness, the system can be tuned to exhibit diverse nonlinear stiffness profiles and a broad QZS operating range. This characteristic enables ULF vibration suppression without compromising the structural load-bearing integrity.

- Under typical earthquake loads, the offshore platform equipped with the NXVIS significantly reduced the dynamic response of the offshore platform. Under the El Centro earthquake load, the maximum deck acceleration of the platform with the X-shaped vibration isolation system was reduced by 68.03%, and the maximum deck displacement was reduced by 64.23% compared to the original system. Under the Taft earthquake load, the maximum deck acceleration and displacement were reduced by 47.85% and 77.31%, respectively.

- Due to the HSLDS characteristic of the X-shaped nonlinear isolator, the proposed NXVIS can effectively suppress the deck acceleration response of the offshore platform with small deck displacements, ensuring structural stability. The results demonstrate that the proposed NXVIS effectively ensures structural safety and provides good comfort.

It is worth emphasizing that the NXVIS is highly flexible in terms of size and load capacity, and its manufacturing and vibration isolation applications are also extremely cost-effective. These outstanding properties and intrinsic nonlinear characteristics make the proposed system an innovative solution for vibration control in jacket-type offshore platforms, providing a novel approach that extends beyond conventional structural vibration mitigation strategies. This system holds significant potential for widespread engineering applications, promising considerable advantages across various industrial practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, supervision, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Impact Fund of Research Grants Council (Hong Kong) (Grant No. R5047-22).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Parameters of the X-shaped isolator.

Table A1.

Parameters of the X-shaped isolator.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Mass M | 1940 ton |

| Stiffness k0 | 100 MN/m |

| Damping coefficient c0 | 300 MNs/m |

| Bar length l | 0.75 m |

| Angle α | 43 deg |

| Angle β | 63 deg |

| Layers number n | 2.0 |

Appendix B

References

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Xu, J.; Su, H.; Zhang, J. Model Reference Adaptive Vibration Control of an Offshore Platform Considering Marine Environment Approximation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, R.; Cui, F.; Townsend, N.; Foo, C.C.; Guo, J.; Shenoi, A.; Xiong, Y. A Review of Vibration Control Methods for Marine Offshore Structures. Ocean Eng. 2016, 127, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, D.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, G. Vibration Control of Jacket Offshore Platform through Magnetorheological Elastomer (MRE) Based Isolation System. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 114, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Xu, J. Neural Network-Based Fuzzy Vibration Controller for Offshore Platform with Random Time Delay. Ocean Eng. 2021, 225, 108733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som, A.; Das, D. Seismic Vibration Control of Offshore Jacket Platforms Using Decentralized Sliding Mode Algorithm. Ocean Eng. 2018, 152, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Lavassani, S.H.; Mousavi Gavgani, S.A.; Doroudi, R. Optimal Control of Jacket Platforms Vibrations under the Simultaneous Effect of Waves and Earthquakes Considering Fluid-Structure Interaction. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, R.; Chakraborty, S. Wave Vibration Control of Jacket Platform by Tuned Liquid Dampers. Ocean Eng. 2022, 247, 110721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussan, M.; Rahman, M.S.; Sharmin, F.; Kim, D.; Do, J. Multiple Tuned Mass Damper for Multi-Mode Vibration Reduction of Offshore Wind Turbine under Seismic Excitation. Ocean Eng. 2018, 160, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Chang, Z.; Zhao, L. Mitigating Deepwater Jacket Offshore Platform Vibration under Wave and Earthquake Loadings Utilizing Nonlinear Energy Sinks. Ocean Eng. 2023, 283, 115096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ying, X.; Guo, B.; He, Z. Collapse Safety Reserve of Jacket Offshore Platforms Subjected to Rare Intense Earthquakes. Ocean Eng. 2017, 131, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Long, X.; Li, Q.S.; Xiao, Y.Q. Vibration Control of Steel Jacket Offshore Platform Structures with Damping Isolation Systems. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, T.; Moatimid, G.M.; Zakria, S.; Galal, A. Dynamical Analysis of a Four-Degree-of-Freedom Vibratory Structure: Bifurcation, Stability, and Resonance Exploration. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2025, 44, 1555–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Huang, S.; Huang, C.; Liu, R.; Ouyang, F. Passive Control of Jacket–Type Offshore Wind Turbine Vibrations by Single and Multiple Tuned Mass Dampers. Mar. Struct. 2021, 77, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzangbar, A.; Vaezi, M. Effects of Pendulum Tuned Mass Dampers on the Dynamic Response of Jacket Platforms. Ocean Eng. 2022, 249, 110895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M.; Pourzangbar, A.; Fadavi, M.; Mousavi, S.M.; Sabbahfar, P.; Brocchini, M. Effects of Stiffness and Configuration of Brace-Viscous Damper Systems on the Response Mitigation of Offshore Jacket Platforms. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 107, 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Li, H.; Lv, G.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Yu, H. Vibration Control of Deepwater Offshore Platform Using Viscous Dampers Under Wind, Wave, and Earthquake. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Chen, S.; Hao, H.; Han, C.; Ni, R.; Zhuo, Y. Assessment of Hydrodynamic Performance and Motion Suppression of Tension Leg Floating Platform Based on Tuned Liquid Multi-Column Damper. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.R.; Shabakhty, N.; Enferadi, M.H. Vibration Control of Offshore Jacket Platforms through Shape Memory Alloy Pounding Tuned Mass Damper (SMA-PTMD). Ocean Eng. 2019, 191, 106348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yin, X.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Li, P.; Li, P. Effectiveness of MTMD for Jacket Offshore Platform under Wave and Earthquake Excitations. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 199, 109654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokmabady, H.; Mohammadyzadeh, S.; Mojtahedi, A. Suppressing Structural Vibration of a Jacket-Type Platform Employing a Novel Magneto-Rheological Tuned Liquid Column Gas Damper (MR-TLCGD). Ocean Eng. 2019, 180, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xu, H.; Tang, J.; Zhou, S. Exploring Nonlinear Degradation Benefit of Bio-Inspired Oscillator for Engineering Applications. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 119, 736–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X. The X-Structure/Mechanism Approach to Beneficial Nonlinear Design in Engineering. Appl. Math. Mech. 2022, 43, 979–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Jing, X. Superior Nonlinear Passive Damping Characteristics of the Bio-Inspired Limb-like or X-Shaped Structure. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 125, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Jing, X.; Chao, X. X-Shaped Mechanism Based Enhanced Tunable QZS Property for Passive Vibration Isolation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 218, 107077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Jing, X. Human Body Inspired Vibration Isolation: Beneficial Nonlinear Stiffness, Nonlinear Damping & Nonlinear Inertia. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 117, 786–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, T.S.; Moatimid, G.M.; Zakria, S.K.; Galal, A.A. Vibrational and Stability Analysis of Planar Double Pendulum Dynamics near Resonance. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 21667–21699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xuan, M.; Xin, J.; Liu, Y.; Gu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. Design and Experiment of Dual Micro-Vibration Isolation System for Optical Satellite Flywheel. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 179, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ning, D.; Sun, S.S.; Zheng, J.; Lu, H.; Nakano, M.; Zhang, S.; Du, H.; Li, W.H. A Semi-Active Suspension Using a Magnetorheological Damper with Nonlinear Negative-Stiffness Component. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 147, 107071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Shen, Z.; Lv, H.; Sareh, P. A Quasi-Zero-Stiffness Vibration Isolator Inspired by Kresling Origami. Structures 2024, 69, 107315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xie, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Luo, H.; Jing, X. Bio-Inspired Vibration Isolator with Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Self-Powered Monitoring. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 223, 111854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jing, X.; Xu, J.; Cheng, L. Vibration Isolation via a Scissor-like Structured Platform. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 2404–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).