Abstract

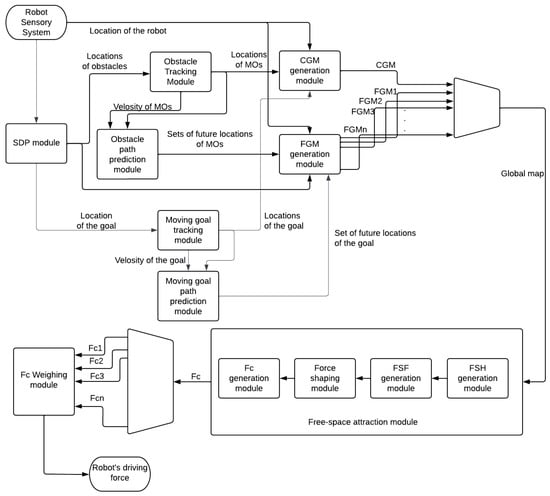

This paper presents a novel development of a new machine learning-based control system for the Agoraphilic (free-space attraction) concept of navigating robots in unknown dynamic environments with a moving goal. Furthermore, this paper presents a new methodology to generate training and testing datasets to develop a machine learning-based module to improve the performances of Agoraphilic algorithms. The new algorithm presented in this paper utilises the free-space attraction (Agoraphilic) concept to safely navigate a mobile robot in a dynamically cluttered environment with a moving goal. The algorithm uses tracking and prediction strategies to estimate the position and velocity vectors of detected moving obstacles and the goal. This predictive methodology enables the algorithm to identify and incorporate potential future growing free-space passages towards the moving goal. This is supported by the new machine learning-based controller designed specifically to efficiently account for the high uncertainties inherent in the robot’s operational environment with a moving goal at a reduced computational cost. This paper also includes comparative and experimental results to demonstrate the improvements of the algorithm after introducing the machine learning technique. The presented experiments demonstrated the success of the algorithm in navigating robots in dynamic environments with the challenge of a moving goal.

1. Introduction

Mobile robot navigation plays a vital role in the field of robotics. The Agoraphilic navigation algorithm has been developed to overcome many challenges in mobile robot navigation [1,2,3]. The work presented in this paper is an advanced development of Agoraphilic algorithm.

There are a number of path planning methods developed for robot navigation [4,5,6,7]. Among them, artificial potential field (APF) [8], cell decomposition [9], mathematical programming [10] and roadmap [11] are identified as fundamental path planning algorithms. The APF method is popular among researchers due to its many advantages, such as simplicity and adaptability. However, there are well-documented inherited problems in APF-based methods [7,12,13]. These inherited drawbacks, such as (i) trap situations or dead locks (local minima), (ii) no passage between closely spaced obstacles, (iii) oscillations in narrow corridors and (iv) the goal non-reachable-with-obstacles-nearby problem (GNRON), have motivated researchers to improve the APF-based methods and overcome these problems [14,15,16,17]. However, all these methods have attempted to address the bad outcomes of the APF method while keeping its basic concept. As a result, those algorithms have lost some of the main advantages of the APF method such as simplicity and adaptability.

The novel Agoraphilic algorithm was developed to reduce the drawbacks of APF method while keeping its advantages. It imitates human navigation behavior to reach the goal. In contrast to APF method, the Agoraphilic algorithm does not look for obstacles to avoid but for space ‘solutions’ to follow, hence the term ‘Agoraphilic’. For this reason, it is termed an ‘optimistic’ navigation algorithm.

Only a few navigation algorithms can track and hunt a moving goal in an unknown dynamic environment [4]. However, there are practical applications where a robot has to follow or hunt a moving goal. The authors’ previous work on developing the new Agoraphilic navigation algorithm in dynamic environments (ANADE) also had a limitation of tracking and hunting a moving goal. Therefore, in this research, we further improved the ANADE algorithm using a machine learning (ML)-based method to address this issue. This paper presents the novel ML-based ANADE algorithm which incorporates the free-space attraction concept to track and hunt a moving goal in an unknown dynamic environment. To successfully follow and hunt a moving goal it is essential to track and estimate the location and velocity of the moving goal. Furthermore, having a short-term path prediction of the moving goal will increase the efficiency of the task.

This paper discusses the overall development of the new algorithm while providing detailed information about the new ML-based system introduced for ANADE algorithm. Section 2 of this paper discusses the development of ML-based ANADE algorithm. Section 3 introduces the new ML-based system. Development of the experimental configuration and results are presented in Section 4. Section 5 provides a discussion of our findings and concluding remarks.

3. Machine Learning (ML) for ANADE Algorithm

The force-shaping modules used in the previous versions of ANADE algorithms do not consider the velocity of the moving goal when shaping the free-space forces [1]. The novel ML-based force-shaping module was developed to address this problem. The main challenge associated with ML was generating a good training and testing datasets. The trained module with these pre-determined datasets should be able to successfully replace the fuzzy logic controller (FLC) in the force shaping module while incorporating the velocity of the moving goal for force shaping. Training and testing datasets were developed for the five main Agoraphilic modes:

- Goal seeking: the goal is in the line of sight of the robot;

- Normal travel: the robot is in an environment with dynamic as well as static obstacles with a reasonable amount of free-space;

- Safe travel: the robot is in a cluttered environment with very limited free-space;

- Right side safe: the robot is in a cluttered environment with limited free-space on the left side of the robot;

- Left side safe: the robot is in a cluttered environment with limited free-space on the right side of the robot.

The development process of these datasets is discussed in the following sections.

3.1. Training and Testing Datasets Generation

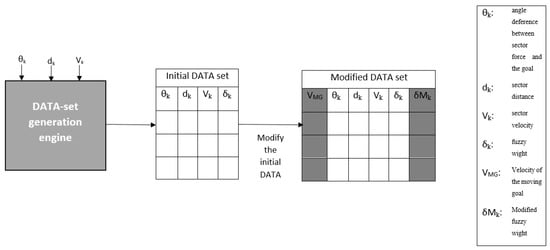

The development of a novel ML-based force shaping module required the creation of a substantial dataset for training and testing purposes. However, manually creating a large dataset is challenging and impractical. To address this, five fuzzy logic controllers (FLCs) were developed to generate initial datasets, each corresponding to one of the five main Agoraphilic modes. Subsequently, domain knowledge was applied to modify the initial datasets to obtain final training and testing datasets, Figure 2. In this stage velocity of the moving goal was considered. By making these modifications, the datasets became more representative of real-world scenarios, allowing for more accurate training and evaluation of the models across different Agoraphilic modes.

Figure 2.

Data-set generation procedure.

3.2. Datasets for Different Agoraphilic Behaviors

Five dataset generation engines were developed using five different fuzzy logic controllers. Those are linguistic fuzzy logic controllers. To develop the fuzzification module, four databases were designed. Three databases were used for the three inputs:

- angle difference between sector forces and the goal (). Five different databases were used for the five engines;

- normalized sector distance ()-this is common for all five engines (database is developed according to Equation (12));

- normalized sector velocity ()-this is common for all five engines (database is developed according to Equation (13))

and one for the output,

- 1.

- fuzzy shaping factor ().

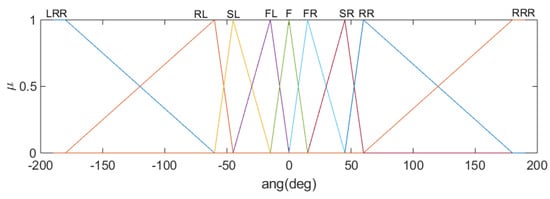

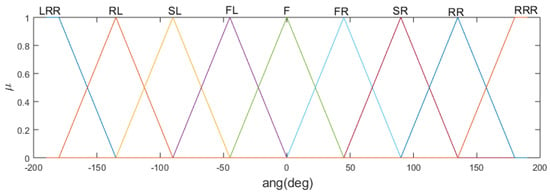

The database for consists of nine fuzzy membership functions. The corresponding linguistics are LRR: Left Rear Rear, LR: Left Rear, LS: Left Side, LF: Left Front, F: Front, RF: Right Front, RS: Right Side, RR: Right Rear and RRR: Right Rear Rear (Figure 3). As mentioned above five different databases were used for in the five dataset generation engines:

Figure 3.

Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for goal seeking behavior.

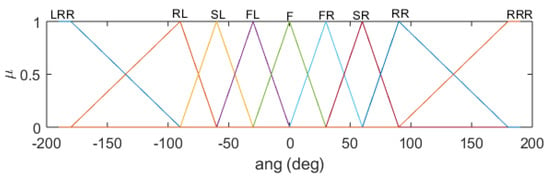

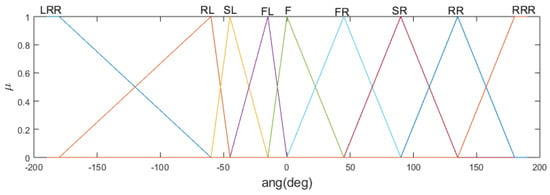

Figure 4. Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for normal travel behavior.

Figure 4. Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for normal travel behavior. Figure 5. Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for safe travel behavior.

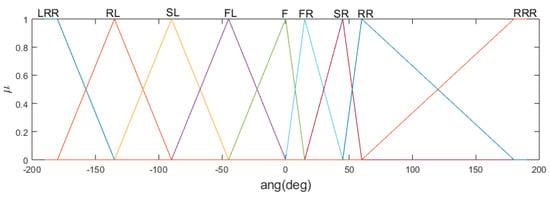

Figure 5. Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for safe travel behavior. Figure 6. Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for right-side safe behavior.

Figure 6. Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for right-side safe behavior. Figure 7. Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for left-side safe behavior.

Figure 7. Membership function for the first input of the fuzzy controller for left-side safe behavior.

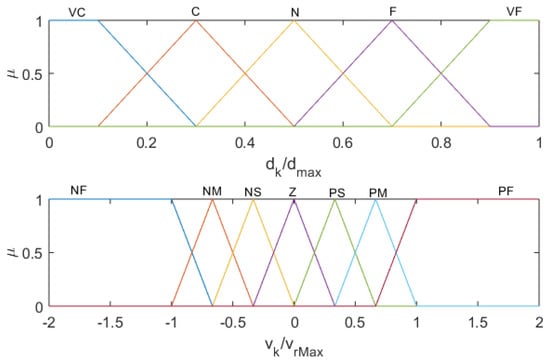

The database for also consists of five fuzzy membership functions as shown in Equation (12). The corresponding linguistics are VC: Very Close, C: Close, N: Near, F: Far, VF: Very Far, Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Membership functions of the second () and third () inputs of the fuzzy controller.

The database for also consists of seven fuzzy membership functions as shown in Equation (13). The variable is positive if the moving obstacle is approaching the robot. The corresponding linguistics are NF: Negative Fast, NM: Negative Medium, NS: Negative Slow, Z: Zero, PS: Positive Slow, PM: Positive Medium and PF: Positive Fast, Figure 8.

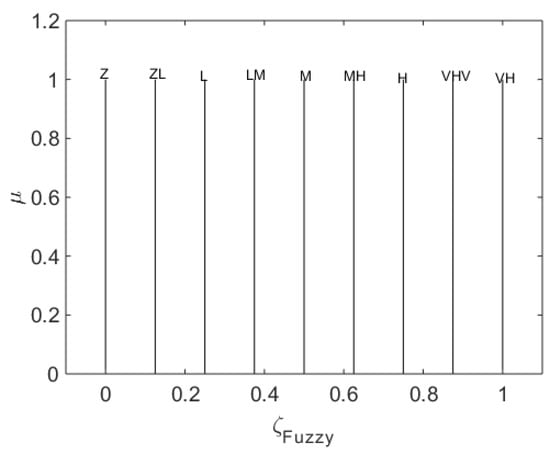

The simple output database is represented by eight fuzzy sets, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Output membership functions of the fuzzy controller.

The fuzzy rule bases used for these dataset generation engines consist of 189 rules.

Different combinations of input data (, and ) are fed into the five dataset generation engines and corresponding fuzzy shaping factor () were recorded in the ‘initial dataset’ generation process (Figure 2). This information is tabulated to get five different initial datasets for different Agoraphilic behaviors.

However, the velocity of the moving goal is not represented in those datasets. Therefore, the initial datasets were manually modified according to the domain knowledge to integrate velocity of moving goal to the dataset.

Sixty percent of the data from the new modified datasets (Figure 2) was used to train the five new ML-based modules. These modules mimic the five different Agoraphilic behaviors.

- ML module for goal seeking behavior;

- ML module for goal normal travel behavior;

- ML module for goal safe travel behavior;

- ML module for goal right side safe behavior;

- ML module for goal left side safe behavior.

To build the ML-based modules ‘k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) algorithm’ [21,22,23] was used.

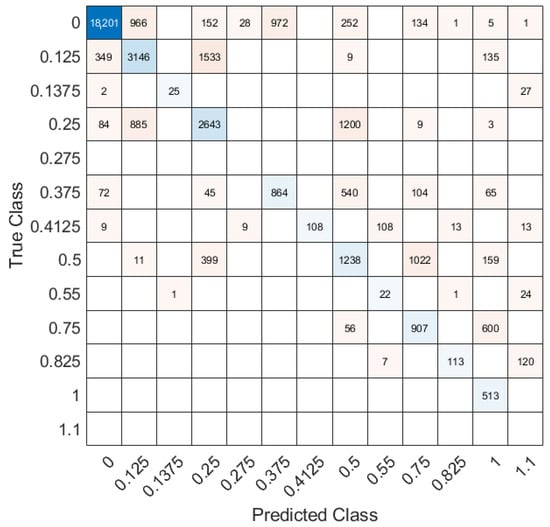

40% data from each modified dataset was used to evaluate the corresponding trained module. In the evaluation, it was identified that the mismatch of each module was as follows (Figure 10):

Figure 10.

Confusion chart of ML module for goal seeking behavior.

- ML module for goal seeking behavior, 23%;

- ML module for normal travel behavior, 7%;

- ML module for safe travel behavior, 8%;

- ML module for right side safe behavior, 9%;

- ML module for left side safe behavior, 10%.

A supervisory controller alters the robot’s motion behavior among the five Agoraphilic behaviors based on the different environmental conditions.

4. Experimental Testing and Analysis of Results

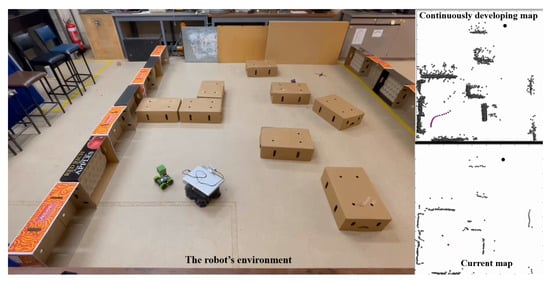

The experimental work was conducted to demonstrate and validate the performance of the algorithm with the new ML-based force-shaping module. In this paper, a random real-world experiment is presented to validate the algorithm with the proposed force-shaping module. Furthermore, two comparative experiments are presented to test the importance of the ML-based controller. The experimental setup used is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Experimental setup.

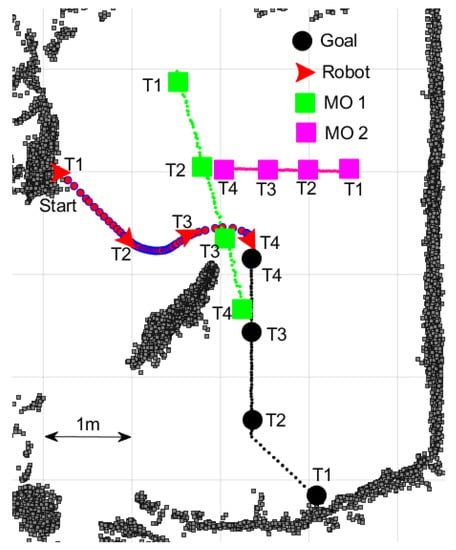

4.1. Experiment 1: Random Experiment with Two Moving Obstacles in a Cluttered Environment with a Moving Goal

This experiment was performed to test the algorithm’s capability of reaching a moving goal in a dynamically cluttered environment with multiple moving obstacles in real-world circumstances. In this experiment, two moving obstacles with random acceleration variations were used with some static obstacles. The moving goal performed a major direction change in this experiment. The starting conditions of the experiment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Initial conditions of experiment 1.

The goal, the robot, and MOs started moving at the instant labelled T1, Figure 12. At this time instant, the goal was located directly in (+x, −y) direction of the robot with a linear distance of 448 cm. During T1 to T2 MO1 and MO2 developed their movements in the robot’s left-hand side with the intention of challenging the robot in future iterations. At time instant T2, the robot had to change its direction because of the static obstacle in front of the robot. In this situation, the robot had 2 options,

Figure 12.

The robot’s path observed in experiment 1 (robot, goal and the MOs locations in four different time instants, T1–T4).

- Move to the left (towards MO1 and MO2);

- Move to the right (more free-space).

The robot picked the first option although there was more challenge from the moving obstacles. The new moving direction of the goal was the main reason for this decision. At time instant T2, the goal had changed its velocity towards +y direction. During time instants T2 to T3 the robot moved with a low speed and allowed the MO1 to pass the robot. During time instants T3 to T4 the robot moved towards the goal through the free-space passage between MO1, MO2 and the static obstacle. At time instant T4, the robot successfully reached the moving goal.

The robot took 89 s to finish the task successfully, with a path length of 275 cm. During the process, the robot maintained an average speed of 3 cm/s. The summarized test results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summarized test results of experiment 1.

4.2. Comparative Test between FLC-Based ANADE and ML-Based ANADE

The experimental work presented in this subsection was conducted to demonstrate and validate the performance improvement of the ANADE algorithm with the novel ML-based force-shaping module. The experiments were designed to test the performance of the new ML-based ANADE in comparison with FLC-based ANADE. In this subsection, a simulation test and an experimental test are presented.

4.2.1. Comparison 1—Simulation Test

This simulation test was conducted to test the algorithm’s capability of reaching a moving goal in a dynamic environment with a moving obstacle and a static obstacle. In this simulation, two tests were conducted:

- With the ML-based force-shaping module;

- With FLC-based force shaping module.

In both tests, all other parameters were kept unchanged. The initial conditions of the tests are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Initial conditions of comparison test 1.

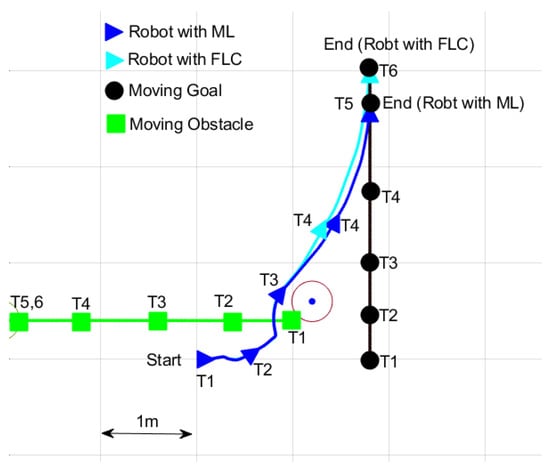

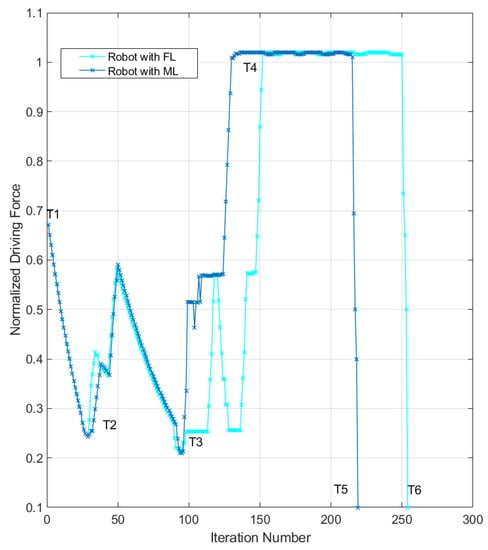

The goal, the robot, and MO started moving at the instant labelled T1, Figure 13. At this time instant, the goal was located directly in (+x, −y) direction of the robot with a distance of 900 cm. During T1 to T2, MO1 developed its movements in the robot’s right-hand side with the intention of challenging the robot. At time instant T2, the robot with ML and FLC successfully passed the MO1. From T1 to T3 the robot followed the same path in both cases. The speed variations were also almost the same from T1 to T3, Figure 14. However, the robot with ML started increasing its speed as soon as it passed the static obstacle (at T3), Figure 14. Additionally, it started moving towards the moving direction of the goal. On the other hand, the robot with FLC started increasing its speed 50 iterations later. As a result of this different decision-making, the robot with ML reached the goal with a shorter path (10%), and also in less time (13.78%). Furthermore, the robot with ML had a 4.3% higher average speed. The summarized test results are shown in Table 4.

Figure 13.

The robot’s paths observed in simulation (robot, goal, and the MO locations in six different time instants, T1–T6).

Figure 14.

The robot’s normalized driving force variations observed in simulation.

Table 4.

Summarized test results of comparison test 1.

4.2.2. Comparison 2—Experimental Test

This experimental test was conducted to test the algorithm’s capability of reaching a moving goal in a dynamic environment with multiple moving obstacles with random acceleration variations and static obstacles in the real world. Similar to comparison 1, in this experiment also two tests were conducted:

- With the ML-based force-shaping module;

- With FLC-based force shaping module.

In both tests, all other parameters were kept the same. The initial conditions of the experiments are tabulated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Initial conditions of comparison test 2 (experimental test).

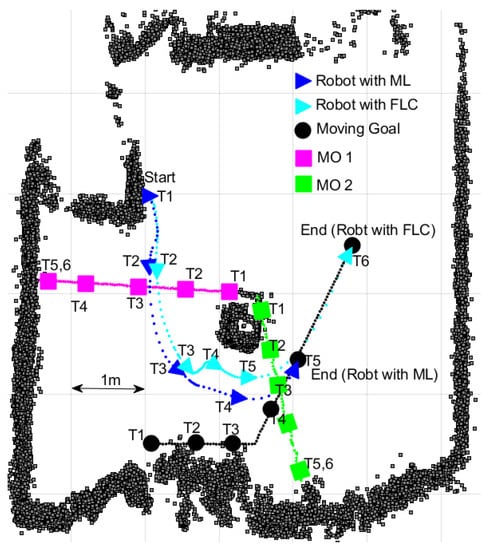

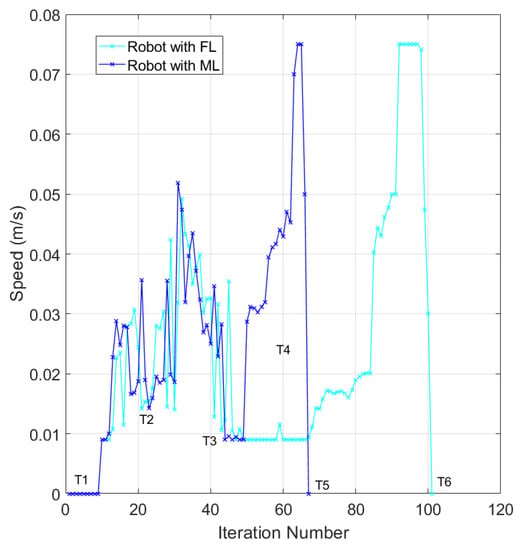

At the time instant labelled T1, the robot, MO, and the goal started moving, Figure 15. At time instant T1, the goal was positioned towards the −y direction of the robot with a distance of 250 cm. MO1 developed its movements from T1 to T2, with the purpose of challenging the robot. At time instant T2, the robot with ML and FLC successfully passed the MO1. From T1 to T3 both the robot followed slightly different paths. The speed variations show that both the algorithms (with ML and with FLC) reduced speed as the challenge from MO2, Figure 16. The robot with FLC started changing its direction to avoid MO2. On the other hand, the robot with ML without changing its path, allowed the MO2 to pass the robot. The robot with ML increased its speed as soon as MO2 passed the robot (at T3), Figure 16. Additionally, it started moving toward the moving direction of the goal. On the other hand, the robot with FLC started increasing its speed 35 iterations later. As a result of this different decision-making, the robot with ML reached the goal with a shorter path (19%) and also in less time (35%). However, the robot with FLC had an 8% higher average speed. The summarized experimental results are tabulated in Table 6.

Figure 15.

The robot’s paths observed in the experimental test (robots, goal, and the MO’s locations in six different time instants, T1–T4).

Figure 16.

The robot’s speed variations observed in simulation.

Table 6.

Summarized test results of the comparison test 2 (experimental test).

5. Conclusions

This paper presented the development of a novel machine learning-based Agoraphilic navigation algorithm. The new algorithm has proven its success and advantages in navigating robots in an unknown static and dynamic environment with a moving goal. The proposed algorithm uses a single attractive force to pull the robot towards the moving goal via current free-space leading to future growing free-space passages. This paper introduced a machine learning-based module to the Agoraphilic concept. This permitted the algorithm to effectively integrate the velocity of the moving goal in decision-making. To support the new machine learning-based module, the presented goal tracking, goal path prediction, CGM generation, and FGM generation modules were developed. Combining these novel modules with other main modules used in previous ANADE algorithms permits the algorithm to incorporate the rapid changes that occur in unknown dynamic environments with high uncertainties.

In this paper, a real-world experiment was presented to demonstrate the significance of the algorithm in navigating a robot with a moving goal. This experiment proved that the algorithm can successfully follow a moving target even in a dynamically cluttered environment with multiple moving obstacles. Furthermore, to demonstrate the importance of the ML technique, two comparison experiments were conducted. The experiments’ results proved that the novel ML-based method improved the algorithm’s performances by reducing path length, reducing the time to hunt the moving goal and also reducing the sample time. The first comparison experiment showed that the algorithm with ML used a shorter path to reach the goal (10%), also in 13.8% less time compared to the FL-based method. Moreover, the robot with ML maintained a higher average speed (4.3%) compared to the algorithm with FL. These facts were further verified by the results observed in the second comparison experiment. The algorithm with ML reached the goal with a 19% shorter path in 35% less time. Additionally, the algorithm with ML had a 5% lower average sampling time. These comparative and experimental results demonstrated the improvements of the algorithm after introducing the machine learning technique. The presented algorithm demonstrated the enhanced capability to successfully navigate mobile robots in dynamically cluttered environments to hunt a moving target.

Author Contributions

H.H., Y.I. and G.K. conceived the idea. H.H. designed the methods and performed the experiments. H.H., Y.I. and G.K. analyzed the results and wrote this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) via Federation University of Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hewawasam, H.S.; Ibrahim, Y.; Kahandawa, G.; Choudhury, T. Agoraphilic Navigation Algorithm under Dynamic Environment. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 1727–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawasam, H.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Kahandawa, G.; Choudhury, T. Agoraphilic navigation algorithm in dynamic environment with obstacles motion tracking and prediction. Robotica 2022, 40, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawasam, H.S.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Kahandawa, G.; Choudhury, T.A. Agoraphilic Navigation Algorithm in Dynamic Environment with and without Prediction of Moving Objects Location. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; Volume 1, pp. 5179–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patle, B.; Babu, L.G.; Pandey, A.; Parhi, D.; Jagadeesh, A. A review: On path planning strategies for navigation of mobile robot. Def. Technol. 2019, 15, 582–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Savkin, A.V. An algorithm for safe navigation of mobile robots by a sensor network in dynamic cluttered industrial environments. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2018, 54, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Parhi, D.R. New algorithm for behavior-based mobile robot navigation in cluttered environment using neural network architecture. World J. Eng. 2016, 13, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Lang, N.; Li, H.; Xu, D. Path Planning in Uncertain Environment with Moving Obstacles using Warm Start Cross Entropy. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siming, W.; Tiantian, Z.; Weijie, L. Mobile robot path planning based on improved artificial potential field method. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference of Intelligent Robotic and Control Engineering (IRCE), Lanzhou, China, 24–27 August 2018; pp. 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego, F.; Sanchis, J.; García-Nieto, S.; Simarro, R. UAV motion planning and obstacle avoidance based on adaptive 3D cell decomposition: Continuous space vs discrete space. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Second Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ETCM), Salinas, Ecuador, 16–20 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouwenaars, T.; De Moor, B.; Feron, E.; How, J. Mixed integer programming for multi-vehicle path planning. In Proceedings of the 2001 European Control Conference (ECC), Porto, Portugal, 4–7 September 2001; pp. 2603–2608. [Google Scholar]

- Akbaripour, H.; Masehian, E. Semi-lazy probabilistic roadmap: A parameter-tuned, resilient and robust path planning method for manipulator robots. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 89, 1401–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.Y.; Fernandes, A. Study on mobile robot navigation techniques. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology, IEEE ICIT’04, Hammamet, Tunisia, 8–10 December 2004; Volume 1, pp. 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hewawasam, H.S.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Kahandawa, G.; Choudhury, T.A. Evaluating the Performances of the Agoraphilic Navigation Algorithm under Dead-Lock Situations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 29th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Delft, The Netherlands, 17–19 June 2020; pp. 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babinec, A.; Duchoň, F.; Dekan, M.; Mikulová, Z.; Jurišica, L. Vector Field Histogram* with look-ahead tree extension dependent on time variable environment. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2018, 40, 1250–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yamashita, A.; Asama, H.; Tamura, Y. An efficient improved artificial potential field based regression search method for robot path planning. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, Chengdu, China, 5–8 August 2012; pp. 1227–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Saranrittichai, P.; Niparnan, N.; Sudsang, A. Robust local obstacle avoidance for mobile robot based on dynamic window approach. In Proceedings of the 2013 10th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology, Krabi, Thailand, 15–17 May 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Lee, S.; Varnhagen, S.; Tseng, H.E. Path planning for autonomous vehicles using model predictive control. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 11–14 June 2017; pp. 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Hewawasam, H.S.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Kahandawa, G.; Choudhury, T.A. Comparative Study on Object Tracking Algorithms for mobile robot Navigation in GPS-denied Environment. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 13–15 February 2019; pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawasam, H.S.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Kahandawa, G.; Choudhury, T.A. Development and Bench-marking of Agoraphilic Navigation Algorithm in Dynamic Environment. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 28th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–14 June 2019; pp. 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawasam, H.; Ibrahim, Y.; Kahandawa, G. A Novel Optimistic Local Path Planner: Agoraphilic Navigation Algorithm in Dynamic Environment. Machines 2022, 10, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.; Maté, C. Forecasting histogram time series with k-nearest neighbors methods. Int. J. Forecast. 2009, 25, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamparia, A.; Singh, S.K.; Luhach, A.K.; Gao, X.Z. Classification and analysis of users review using different classification techniques in intelligent e-learning system. Int. J. Intell. Inf. Database Syst. 2020, 13, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nampoothiri, M.H.; Anand, P.G.; Antony, R. Real time terrain identification of autonomous robots using machine learning. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 2020, 4, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).