Abstract

This article presents a fluid–elastic structure interaction (FSI) problem when the temperature variation of the two media is also taken into account. We introduced the mathematical description of this interaction in a recent article. Our model includes the coupling between the fluid and the elastic medium equations and, in addition, the coupling with the temperature equations. The novelty of this approach is that we succeed in analyzing a complicated double-coupled problem that allows us to describe more complex physical phenomena both from the theoretical and numerical points of view. Since the main goal of this article is to analyze the influence of an exterior field of temperature on fluid pressure variations, the theoretical results obtained in our previous article are completed with qualitative properties concerning the fluid pressure, such as existence, regularity and uniqueness. Our study continues with approximation schemes: in order to improve the unknowns regularity, we introduce the pressure approximation by a sequence of viscoelastic pressure functions and we prove the weak convergence of this sequence to the pressure; then, we present a numerical approximation scheme with stability and convergence results and Uzawa’s algorithm. The last part of the article is devoted to numerical simulations that rely on the numerical schemes introduced and studied before and highlight some physical phenomena related to the considered problem.

Keywords:

thermal fluid–structure interaction; blood pressure; pressure uniqueness; viscoelastic problems; numerical approximation; convergence; Uzawa’s algorithm; simulations MSC:

74F10; 74F05; 76D03; 65M12

1. Introduction

Fluid–elastic structure interaction is a phenomenon that appears in biology, aerodynamics and other fields of real life and represents a coupled multiphasic problem. Mathematical and numerical analysis of the coupled fluid–elastic structure interaction problem have been topics of interest in the last years. The works presented below have been selected to highlight different approaches from mathematical and numerical points of view regarding FSI problems. In [1,2] existence results are obtained, Refs. [3,4] present an asymptotic analysis, Refs. [5,6] analyze optimal control problems, Refs. [7,8] deal with numerical methods and algorithms, while [9] gives a mathematical introduction to modeling, analysis and simulation techniques for FSI problems.

Our work represents a mathematical and numerical study associated with a simplified model of blood flow through the circulatory system. We consider a thermal FSI problem, which means that in addition to the two coupled models—the incompressible Navier–Stokes system for the fluid and the linear elasticity equations for the elastic structure—we also consider the temperature variation in the two media. Temperature is a physical parameter that plays an important role in many real-life applications. To support this claim, we give two examples of very recent articles dealing with this parameter: [10,11]. So, considering temperature as an additional unknown of the problem on the one hand leads to a mathematical model closer to a physical phenomenon, but, on the other hand, it greatly complicates the mathematical study.

Theoretical studies of FSI problems involving temperature have been published, as far as we know, rarely and only in the last few years (see [12,13,14]). In [12] only the fluid is heat-conducting; the structure does not conduct heat; in [13] a nonlinear interaction problem between a thermoelastic shell and a heat-conducting fluid is considered; the model introduced in [14] deals with a weakly coupled thermal FSI problem; the stationary Navier–Stokes equations for the fluid domain; the convection-diffusion problem for the whole domain and the linear thermoelasticity system in the elastic domain are solved separately. The novelty of our approach is that, unlike the problem studied in [14], we succeed in analyzing, both from mathematical and numerical viewpoints, a fully coupled system with nonlinear equations and nonhomogeneous boundary conditions. In our model the fluid motion is described by the incompressible Navier–Stokes system in the Boussinesq approximation; the behavior of the elastic medium is modeled by the linear thermoelasticity equation and, in addition, the variation in the temperature is given by a convection-diffusion equation corresponding to each medium (nonlinear in the fluid domain). The coupling conditions on the interface between the two media are the continuity of velocities and temperatures, and the continuity of normal stresses, and of heat fluxes.

We introduced this model in [15] where we presented the variational formulation for the thermal FSI model, the approximation results and numerical schemes. The present article represents the second part of our approach to the thermal FSI problem. Since the main purpose of this article is to analyze how the changes in the exterior temperature influence blood pressure variations according to our model, we begin by establishing qualitative properties for the fluid pressure such as existence, regularity and uniqueness.

In order to improve the unknowns regularity, we approximate the variational problem with pressure with a sequence of viscoelastic problems and we prove the weak convergence of the sequence of viscoelastic pressure functions to the pressure.

The next step of the theoretical study is to introduce a suitable numerical approximation scheme and to prove its stability and convergence.

Uzawa’s algorithm allows us to solve the finite-dimensional problem studied before by replacing a functional space with restrictions with a space without restrictions.

The last part of the article is devoted to numerical simulations chosen in order to emphasize physical phenomena related to the considered problem. These simulations rely on the numerical schemes presented before and highlight the following aspects:

- The way in which the changes in the exterior temperature influence the blood pressure variations. For example, Ref. [16] says that high ambient temperatures are associated with lower blood pressure; more specifically systolic blood pressure decreases by 5 mm Hg as the exterior medium temperature increases by 10 °C. Another article, Ref. [17], analyzes in more detail the variation in blood pressure with the variation in exterior temperature. So, when the exterior temperature is between 10 °C and 27 °C, the pressure decreases as the temperature increases, but if the temperature is higher than 27 °C, the pressure increases. Another study, Ref. [18], shows a significant influence of temperature in a closed space on blood pressure variation.

- A comparison between the thermal FSI and FSI models. These simulations highlight the fact that taking into account temperature variations in the two media determines major changes, for example, regarding the longitudinal velocity profile in the fluid.

- The influence of the forces acting in the elastic domain on the fluid longitudinal velocity. This study is of practical interest for the blood flow through vessels, representing one of the most important applications of the FSI. We give two examples that support this assertion. The first example concerns blood flow in venous insufficiency. The blood flow through a leg vein has an anti-gravity sense; when the vein loses its elasticity, this sense is modified, determining the reflux of the blood, which leads to medical complications. These complications are reduced by using elastic stockings. A mathematical analysis of how the compression exerted by the elastic stocking influences blood reflux can be found in [6]. The second example is related to blood flow in stenotic coronary arteries. In [19] the influence of the stenotic coronary arterial wall compliance on the arterial blood flow is analyzed.

2. Presentation of the Mathematical Model

The purpose of this section is to present the mathematical model associated with the thermal FSI problem introduced in [15] and some results and notation from [15], necessary in what follows. The mathematical model describing the FSI consists of the system of equations

with boundary conditions,

junction conditions,

and initial conditions

The unknowns of system (1)–(4) are , p, , , , representing the fluid velocity, the fluid pressure, the fluid temperature, the displacement and the temperature of the elastic medium, respectively.

The data of the problem are as follows:

- The geometric data: (the fluid domain), (the solid domain), (the union of the previous two domains), (the fluid boundary), (the solid boundary), (the interface between the two media);

- the positive constants: (which gives the time interval), , (the thermal expansion coefficients corresponding to the two phases), , (the thermal conductivities), , (the specific heats), , (the densities), (the fluid viscosity), (the bulk modulus), where , are the Lamé coefficients;

- the matrix-valued elasticity coefficients , i, with the following:where E is a positive constant representing Young’s modulus and is a constant representing Poisson’s coefficient. The Lamé constants are linked to the elasticity modulus E and the Poisson ratio by

- (the gravitational acceleration);

- the functions (the initial velocity), (the initial temperature), with , , , (the internal heat sources), (the force in ) and (a given temperature on a part of the elastic domain boundary).

The elements of the elasticity coefficients have the well-known properties

Of all the data, the most important role in our problem is played by that appears in and represents an exterior field of temperature that acts on a part of the boundary of the coupled domain.

To reduce the number of unknowns of the problem we introduced the functions and ,

and then we defined and :

where represents an extension on of and has the following properties:

The functional spaces necessary for the study of the variational problem considered in [15] are presented below

The units of the variables or constant expressions that appear in (1)–(4) are as follows: m (for , ), m/s (for , ), K (for , , , ), kg· K−1· m/s3 (for , ), kg/(m· s3) (for , ), kg· m/s2 (for ), s (for ), kg/(m·s) (for ), K−1· m2/s2 (for , ), kg/m3 (for , ), K−1 (for , ), kg/(m· s2) (for , k, p), m/s2 (for ).

The variational formulation that follows is written in dimensionless variables, defined as follows: , , , , , , , , , , .

Let us introduce the notation:

where is the characteristic function of the set A.

The variational problem presented below

was studied in [15].

For obtaining more regularity for the function , as explained in [15], we considered the family of viscoelastic problems depending on a small parameter

In the remainder of this section, we present the elements of the numerical schemes introduced and studied in [15], which are necessary in what follows.

Consider , a great parameter and divide the time interval in N intervals of equal length . Let X be a Banach space. We associate to any function , the approximations , defined by

For a fixed value of , we associate to the viscoelastic problem (12) the following numerical scheme

where

and

Define the following functions:

Define the following sets:

3. The Variational Problem with Pressure

As can be seen, the variational problem (11), studied in [15], does not contain the fluid pressure. The aim of this section is to introduce fluid pressure and to study its properties. Unlike in the case of Navier–Stokes problems, when the pressure is unique up to an additive constant/function of t, we will prove that in our case the pressure is unique.

In addition to the spaces given by (9) we also define the space

Theorem 1.

The pair is the unique solution of problem (11) if and only if there exists a unique function such that is the solution to the problem:

Proof.

2. Suppose next that is the unique solution for (25).

Considering the space

we notice that for all , the function in , in is a test function for , which means that

Denoting

and taking into account the regularity of the terms from the right-hand side of (28), it follows that

Using Prop. 1.1 and Prop. 1.2 of [20], Chap. 1, we introduce a distribution q such that

and

Relation (31) may be written as

Using the density of in we can extend the functional from to and hence for a.e.

Let us define

Since , we can take in (36) , that yields

Let open, bounded with Lipschitz. Denote

the trace operator

and

For calculating for we will use the following generalized Stokes formula:

Relation (31) can also be written as

and, taking into account the regularity of the left-hand, it follows that

Applying next (42) for , we obtain a.e. in

Using the previous relation, (27) becomes

Proceeding in the same way for we obtain a.e. in

with

Consider . Taking as a test function in (45) and in (46) and adding the two relations we obtain a.e. in

An easy calculation gives

Taking into account the Expression , the right-hand side of (48) may be written as

Let us define the spaces

We construct in what follows a function such that

Let . We consider the problem

The compatibility condition being fulfilled, problem (54) has at least a solution.

Since the operator is surjective, there exists such that .

We define by

and it is easy to show that , which means that we have proven (53).

We define

and we notice that is a linear and continuous functional on that vanishes on . Using a linear algebra theorem, there is a Lagrange’s multiplier such that

Consider and define

The corresponding equation for is

Let . We calculate that gives

Denote

The integration by parts gives

and using the coupling condition on for , we obtain

So leads us to

that represents .

To achieve the proof it remains to show the uniqueness of the pressure. Let us suppose that has two solutions , . From (33) and (61) it follows that

Writing for the two solutions and subtracting them we obtain

which means , that achieves the proof. □

4. The Viscoelastic Variational Problem with Pressure

In this section we introduce the viscoelastic problem with pressure, following the ideas of [15] and we prove that the sequence of viscoelastic pressure functions is weakly convergent to the fluid pressure. To this aim, we consider first the variational problem:

As in [15] we prove

We associate the viscoelastic solution introduced in [15] with the viscoelastic pressure and we have a result similar to Theorem 1:

Theorem 3.

Let be the unique solution of the viscoelastic problem (12). Then there exists a unique such that verifies

The main purpose of this section is to give a sense of the approximation of the unique function p introduced in Theorem 3 by the sequence of viscoelastic pressure functions . To this aim, we prove some auxiliary results.

Proposition 1.

Proof.

In our previous article, Ref. [15], we have obtained

and

The convergence (73) follows by combining the previous two results. □

Proposition 2.

Let be an arbitrary element. Then, there is that verifies

Proof.

We verify first the compatibility condition associated with the problem (76), namely

We have

The assertion of this proposition follows using a result of [21], Chap. III.3. □

Proposition 3.

Proof.

We write for fixed, we choose as a test function with the unique solution of problem (76) corresponding to and we integrate from 0 to ; this yields

Using the boundedness of the sequence in established in [15] and (76)3 we obtain for ,

with depending on and independent of .

The main result of this section is given by

Proof.

From (77) on a subsequence we have

We write the relations (72)2,3,4,5 corresponding to subsequences for a fixed , we take the test function with , with , with and with and we integrate from 0 to

We choose in (84) with ; arbitrary functions, which leads to

Taking in (86) as a test function we obtain

which means

being a function that depends only on t. Introducing (88) in (86) we obtain

and hence

So, any weak limit point of the sequence is equal to p, which means (81) and the proof is achieved. □

5. The Numerical Approximation Scheme with Pressure

In Section 7.3 we presented the numerical scheme associated with the viscoelastic problem (12). Below we introduce a more convenient numerical scheme associated with the same problem

In our previous article, Ref. [15], we associated problem (12) with a different numerical scheme, namely (15). In (90) we add two terms containing the expression in order to obtain a numerical scheme of the same type as (72). We will analyze these terms separately when we prove the convergence result.

In addition to the spaces introduced by (13), we define the step functions space

with the characteristic function of the set . So

which means that the elements of have the property that ,.

The next theorem introduces the pressure approximation and establishes its properties.

Theorem 5.

Let be the unique solution of the problem (90). Then, there is a unique element such that

Proof.

The differences between problems (90) and (93) are the additional term with

and the fact that the space for the test function is different.

We define the functional by

Using it follows that

which means that the functional is a linear functional on that vanishes on . Hence, using a linear algebra theorem it follows that

We define by

or

Using the regularity of the functions given by (99) and the equality

we obtain

which achieves the proof of the existence result.

- Uniqueness

We suppose that is not unique. Then, there exists such that verifies (93), . Defining and subtracting relations corresponding to we obtain

or, using the previous computation and (98)

Let us define the spaces

and the function by

Standard calculations give

We are now in a position to apply a result from [22], Chap. II and so, for any there exists such that

Since , we can take in (102) and we obtain

We establish a stability theorem for the pressure approximations. To this aim, we define the functions

and the set

where , with defined in [15]. □

We prove

Theorem 6.

The set is stable.

Proof.

The relation may be written as

since

Using (104) we obtain the following estimate

We estimate each term from right-hand side of (110) written for using (106) and (112). We present below some examples of these calculations:

All the constants introduced by the previous estimates are independent of h,m,N,. Introducing these calculations in (110) we obtain

since

We estimate the nine terms from the right-hand side of (113), denoted . The calculations for

are given in Appendix A.

For we apply either Theorem 6.2 from [15] or Proposition A1 and, introducing all these estimates in (113), we finally obtain

with independent of h, N and the proof is achieved. □

From (93), independent of time, we will build the equivalent problem that depends on time. We have the functions , , , defined by (16)–(18) and (108), respectively, , , , , , defined by (19)–(22). We also have

Let the functions , , , , , , , and be given by (16)–(22) and (108), respectively. We associate to problem (93), independent of time, a time-dependent system and we prove the following obvious result:

Proposition 4.

is a solution for (93) if and only if , , , ; , , verify the problem

Theorem 7.

Let , , . For all let be the unique solution of problem (93) and the functions , , , , , , be defined by (16)–(22) and (108), respectively. Let be the unique solution of the problem (72). Then, this solution represents the only weak limit point of the sequence when , with respect to the weak convergence in the sets for which the stability of the sets , , , holds.

Proof.

Let us begin with the comparison between problems (117) and (72). The last one has an additional equation, , that does not appear in (117). This additional equation appears since in problem (72) the divergence-free condition for is not included in the space and this property is obtained from . Unlike in (72), in problem (117) we have a weaker condition for divergence.

Using the estimate (115) it follows that there exists a subsequence such that

Let us consider , .

In a similar way, we define the restriction operator

with and given by . Since represent a convergent internal approximation of , it follows that

Consider with . For any fixed value we multiply problem (117) corresponding to the subsequence , by , we integrate from 0 to , integrating by parts the terms with , , and finally, we choose as a test function .

Using dense in , (118) and the calculations from the convergence theorem in [15], we obtain, passing to the limit, that is a solution for (72) and from the pressure uniqueness, we have

So

that achieves the proof. □

Remark 1.

Details concerning the convergence of the terms that do not contain the pressure can be found in Theorem 6.4 from [15].

6. Uzawa’s Algorithm

Solving the finite-dimensional problem (93) means determining and verifying the relations of the system (93). Taking into account the definition of the space , namely (13)1, it follows that the first component of the unknown, , is subject to the constraint of the space. In order to overcome this difficulty, we consider the problem presented below:

For , find, for all and for all , such that

The unknown of the previous problem is . We notice that, unlike , which is subject to the constraint of the space , the first component of the solution to (123) belongs to the space without constraint .

So, Uzawa’s algorithm represents the iterative process of approximating a function subject to restrictions by a sequence of functions without restrictions. This leads to the approximation of by the sequence .

The following theorem gives the existence and uniqueness of the solution of problem (123).

Theorem 8.

For all , , , and , the problem (123) has a unique solution .

Proof.

The problem (123) is divided into three problems

Problem 1 (for )

Problem 2 (for )

Problem 3 (for )

Remark 2.

Because and are uniquely determined by and , respectively, everything we need to prove is the existence and uniqueness for .

Define , by

and

We notice that

where and were defined in [15] by

Starting with the corresponding properties for and , it is easy to prove that is bounded and coercive and is bounded; hence, the existence and uniqueness of follows by means of the Lax-Milgram theorem and the proof is completed. □

We prove next the convergence of the Uzawa’s algorithm.

Theorem 9.

Let , with , and . We suppose that ρ satisfies:

Then, for fixed values of h, N, m, we have the following convergences when :

Proof.

Since h, N, m are fixed, denote

The calculation –(93) gives the following:

Eliminating between , choosing as a test function and adding the equations, it follows that

We estimate next the terms of the left-hand side of the previous equality, denoted . We give below a few examples of these calculations:

Introducing all these calculations in (134) we obtain

Taking into account the expressions of the coefficients of and it is obvious that there is such that

Using the notation (132) and the property , the relation may be written as

Choosing in (137) we obtain

Calculating next we obtain

Writing (141) for , and adding the relations for , it follows that

The inequality (142) shows that the series , , ; , ; are convergent; this gives using Korn’s inequality

or, using the fact that the norm on is the one induced by ,

namely . In the same way, we obtain

namely .

Relation for becomes

Using the properties of the matrices we obtain

and, hence

which is .

It remains to prove . The estimate (142) shows that is bounded in and thus it contains a weakly convergent subsequence in , i.e., there exists such that

On the other hand, the same estimate gives the convergence of which shows that is a Cauchy sequence in the strong topology from .

Combining these two properties we obtain

It remains to prove that in . Passing to the limit with in we obtain

and, since with a closed subspace in it follows that .

We define the function

and, with the same technique as in Theorem 5, it follows that there exists a function such that

This means

which gives the convergence . □

7. Numerical Simulations

The FSI problems appear in many real-life examples that can be found in the literature. A lot of aspects from numerical and mathematical points of view have been studied in the last few years in the case where the temperature is constant; therefore, it does not influence the characteristics of the model. In everyday life, the fluid–structure interactions depend on temperature and we want to show that the temperature influences the motion. The following numerical simulations emphasize the role of temperature in actual life phenomena.

In all examples presented below, we considered a simplified domain, namely , representing the cross-section of a blood vessel, which means that the central domain is the domain occupied by the viscous fluid surrounded by two strips that represent the elastic domain.

The approximation schemes used for the simulations are associated with the viscoelastic problems. We use a finite difference method for time and a finite element method for space. Then, we use Uzawa’s algorithm. The small parameter introduced with the family of viscoelastic problems, which is a fixed parameter in the numerical schemes, must be higher than , where is the time step and are the space steps on and axes, respectively. We have chosen different space and time steps in order to obtain optimum convergence.

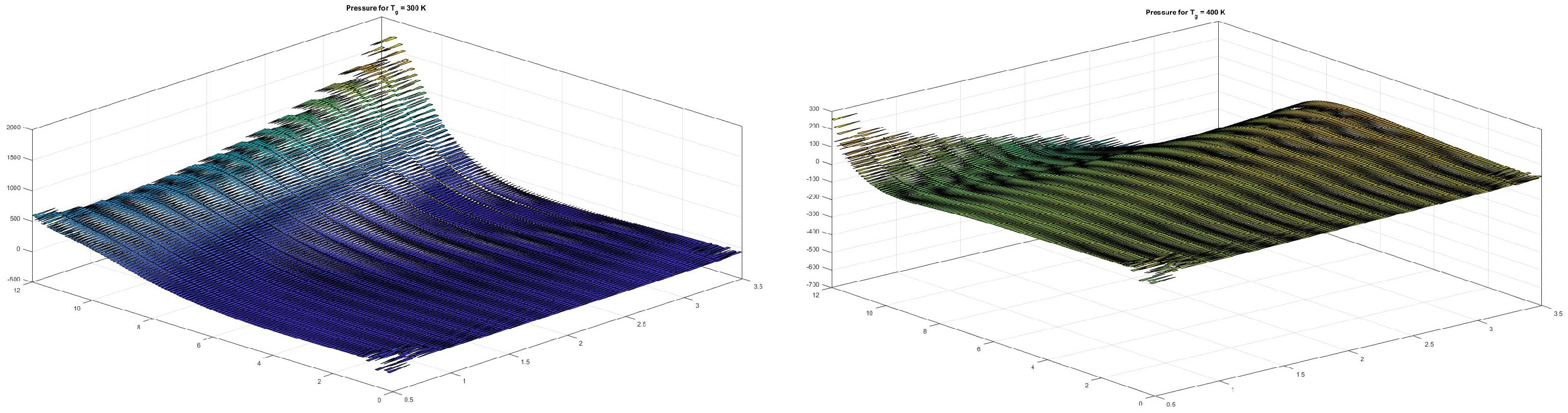

7.1. Pressure Dynamics When Changing the Temperature

In Figure 1 we present two numerical simulations that give the influence of an exterior known field of temperature on the blood pressure variations. They are in agreement with real-life examples: [16] says that high ambient temperatures are associated with lower blood pressure, more specifically the systolic blood pressure decreases with 5 mm Hg as the exterior medium temperature increases with 10 °C. Another article, Ref. [17], analyzes in more detail the variation in blood pressure with the variation in exterior temperature. So, when the exterior temperature is between 10 °C and 27 °C, the pressure decreases as the temperature increases, but if the temperature is higher than 27 °C, the pressure increases. Another study, Ref. [18], shows a significant influence of temperature in a closed space on blood pressure variation. As we can see in the figures below, if we increase the temperature (400 K), we obtain lower pressure values and if we decrease the temperature (300 K) we have higher pressure values.

Figure 1.

The pressure profiles for different exterior temperature values, K (left), K (right).

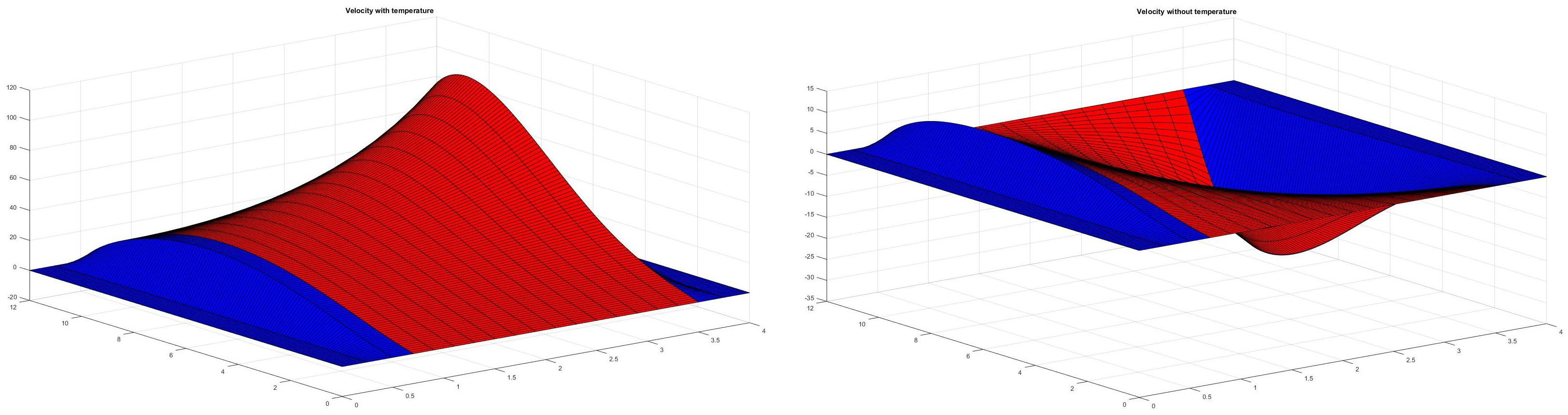

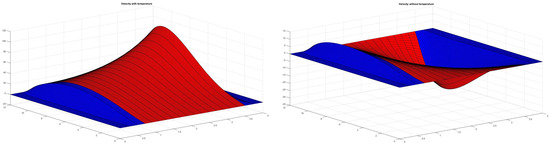

7.2. Temperature Influence on the Fluid–Structure Coupling

In real life, there are many situations in which the interaction between a fluid and an elastic medium is strongly influenced by temperature variations. As an example of the important role played by the temperature we mention the connection between the ambient temperature and the variation in velocity in these two articles [23,24]. In the simulations presented in Figure 2 it can be seen how the velocity profile has important differences if we take into account or not the temperature variations.

Figure 2.

The velocity with and without temperature.

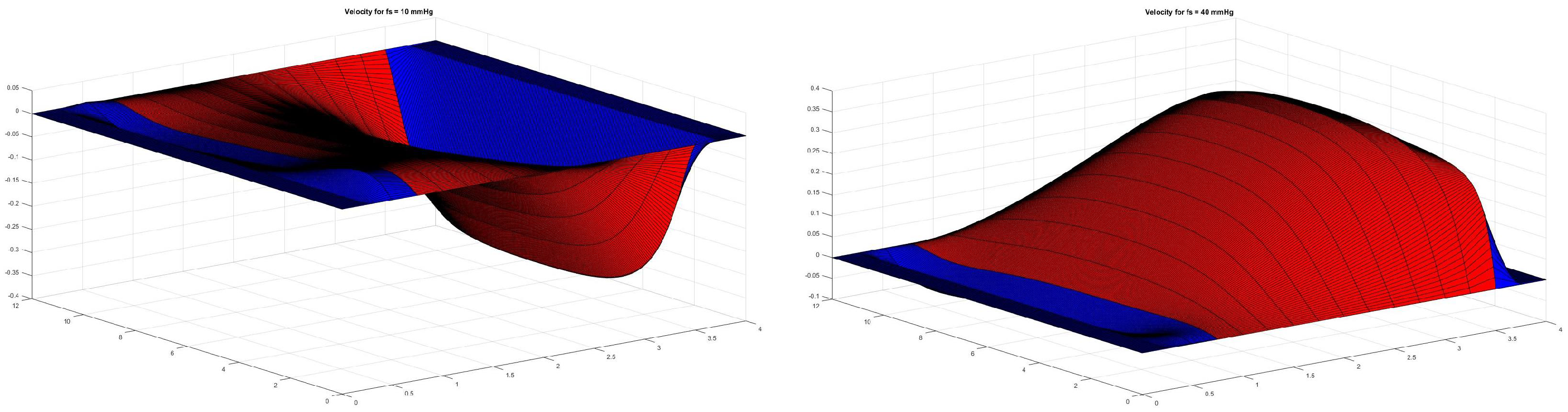

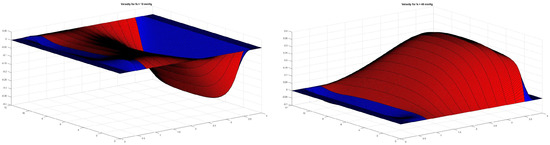

7.3. Velocity Dynamics When Changing the Forces

Among many other examples, the FSI model describes the interaction between the blood and the blood vessel walls. The blood flow through a leg vessel has an anti-gravity sense and this sense is modified when the vein loses its elasticity. When the vein has less elasticity, stagnation and recirculation of the blood might occur. The negative consequences of the lack of vein elasticity can be prevented by exterior compression applied on the blood vessel walls to diminish the blood recirculation phenomena. We have many examples that illustrate what we want to show in our study [25,26,27].

The compression forces act on the -axis. As we will see in Figure 3, lower force values (10 mm Hg) lead to predominant negative values of the velocity and higher force (40 mm Hg) values to predominant positive values.

Figure 3.

The velocity profiles for different force values, mm Hg (left), mm Hg (right).

7.4. Convergence

Data used

Section 7.1 , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 1,000,000.

Section 7.2 , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 500,000.

Section 7.3 , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 500,000.

The convergence has been reached in most cases for , . It can be said that the present numerical method has successfully demonstrated the applicability of the scheme in analyzing the fluid–structure interaction problem.

8. Conclusions

The present article represents the second part of a complete theoretical and numerical approach for an FSI problem when the temperature variations are also taken into account. The mathematical model describing this double-coupled problem (fluid/elastic medium/temperature variation) was introduced in [15] and it represents a challenging topic both from the mathematical and from the numerical viewpoints. In this article, we succeed in obtaining qualitative properties for the fluid pressure by means of variational techniques and proposing suitable approximation schemes, establishing stability and convergence results. Relying on these approximation schemes, we perform numerical simulations that show that our mathematical model faithfully describes real-life physical phenomena. We summarize step by step the proposed approximations, which establish the connection between the calculated solution and the exact solution of the problem. As the following scheme shows, we have proven the calculated solution converges by means of Uzawa’s algorithm to the solution of (123), solution equivalent to the solution of (117). This solution converges to the viscoelastic solution that converges to the exact solution when .

The novelty of this article is represented by the complex model considered since, as far as we know, there are no similar models in the literature (except for a simplified one in [14], in which the problems are decoupled so the study is much simpler) and the methods proposed for overcoming all the difficulties determined by the double-coupling, the nonlinearity and the nonhomogeneity of the problem. Since our work represents a mathematical and numerical study associated with a simplified model of blood flow through the circulatory system, some directions of future research could be to consider a more realistic geometry of the problem or a model closer to reality for modeling blood flow.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and A.C.; methodology, R.S.; software, A.C.; validation, R.S. and A.C. All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

We take in and we estimate each of the terms, denoted .

We estimate next the two remaining terms from the right-hand side of .

We introduce these computations in written for

We take in and estimate each of the terms, denoted .

Introducing these computations in written for we obtain

Then we add the relations for m from 1 to r, and we obtain

Introducing these estimates in the right-hand side of (A3) with , , , we obtain

We estimate next the thirteen terms of the right-hand side of (A4), denoted using some results from [15].

The previous calculations concern the terms that contain unknown functions. For the remaining terms we use

Proposition A1.

Let . For all and we define the time approximations of f, denoted , by (because ). Then

All the constants appearing in the previous calculations are independent of h, N and r. Using these calculations it follows that

with independent of h and N.

References

- Grandmont, C.; Vergnet, F. Existence for a Quasi-Static Interaction Problem Between a Viscous Fluid and an Active Structure. J. Math. Fluid Mech. 2021, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bociu, L.; Čanić, S.; Muha, B.; Webster, J.T. Multilayered Poroelasticity Interacting with Stokes Flow. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 2021, 53, 6243–6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasenko, G.P.; Stavre, R. Viscous Fluid–Thin Elastic Plate Interaction: Asymptotic Analysis with Respect to the Rigidity and Density of the Plate. Appl. Math. Optimiz. 2020, 81, 141–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasenko, G.P.; Stavre, R. Three Dimensional Asymptotic Analysis of an Axisymmetric Flow in a Thin Tube with Thin Stiff Elastic Wall. J. Math. Fluid Mech. 2020, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavre, R. Optimization of the blood pressure with the control in coefficients. Evol. Equ. Control. Theory 2020, 9, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavre, R. A boundary control problem for the blood flow in venous insufficiency. The general case. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2016, 29, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, P.; Reymond, P.; Deparis, S.; Kontaxakis, D.; Stergiopulos, N.; Quarteroni, A. Fluid–structure interaction simulation of aortic blood flow. Comput. Fluids 2011, 43, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deparis, S.; Discacciati, M.; Fourestey, G.; Quarteroni, A. Fluid–structure algorithms based on Steklov–Poincaré operators. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2006, 195, 5797–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, T. Fluid-structure Interactions, Models, Analysis and Finite Elements. In Lecture Notes in Computational Science and Engineering; Barth, T.J., Griebel, M., Keyes, D.E., Nieminen, R.M., Roose, D., Schlick, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwate, M.; Tawade, J.V.; Janthe, P.G.; Garayev, M.; El-Meligy, M.; Kulkarni, N.; Gupta, M.; Khan, M.I. Numerical solutions for unsteady laminar boundary layer flow and heat transfer over a horizontal sheet with radiation and nonuniform heat Source/Sink. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2024, 17, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, N.; Al-Dossari, M.; Tawade, J.; Alqahtani, A.; Khan, M.I.; Abdullaeva, B.; Waqas, M.; Khedher, N.B. Thermoelectric energy harvesting from geothermal micro-seepage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 93, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, D.; Takahashi, T. Existence and uniqueness of strong solutions for the system of interaction between a compressible Navier-Stokes-Fourier fluid and a damped plate equation. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2021, 59, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mácha, V.; Muha, B.; Šárka Nečasová, Š.; Roy, A.; Trifunović, S. Existence of a weak solution to a nonlinear fluid-structure interaction problem with heat exchange. Commun. Partial. Differ. Equ. 2022, 47, 1591–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feppon, F.; Allaire, G.; Bordeu, F.; Cortial, J.; Dapegny, C. Shape optimization of a coupled thermal fluid-structure problem in a level set mesh evolution framework. Bol. Soc. Esp. Mat. Apl. 2019, 76, 413–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciorogar, A.; Stavre, R. A Thermal Fluid–Structure Interaction Problem: Modeling, Variational and Numerical Analysis. J. Math. Fluid Mech. 2023, 25, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Powles, J.W. The effect of ambient temperature on blood pressure in a rural West African adult population: A cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2010, 21, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Ban, J.; Liu, F.; Li, T. Acute effects of temperature exposure on blood pressure: An hourly level panel study. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Ikaga, T.; Hoshi, T.; Ando, S. Effects of Indoor Air Temperature on Blood Pressure among Nursing Home Residents in Japan. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Energy and Environment of Residential Buildings, Brisbane, Australia, 20–24 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, V.; Lopes, D.; Silva, J.; Puga, H.; Lima, R.A.; Teixeira, J.C.; Teixeira, S. Comparison of CFD and FSI simulations of blood flow in stenotic coronary arteries. In Applications of Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation and Modeling; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temam, R. Navier-Stokes Equations; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Galdi, G.P. An Introduction to the Mathematical Theory of Navier–Stokes Equations; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Girault, V.; Raviart, P.A. Finite element approximation of the Navier-Stokes equations. In Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Dold, A., Eckmann, B., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1979; 749p. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, A.; Khanafer, K.; Vafai, K. Fluid-Structure Interactions in a Tissue During Hyperthermia. Numer. Heat Transf. Part Appl. 2014, 66, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Nie, H.; Xu, L.; Yue, J.; Huang, Y. A thermal stress analysis of fluid–structure interaction applied to boiler water wall. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 15, e2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksamawi, H.A.; Mostapha, A.; Brill, A.; Vigolo, D.; Alexiadis, A. Modelling Particle Agglomeration on Through Elastic Valves Under Flow. ChemEngineering 2021, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gataulin, Y.A.; Yukhnev, A.D.; Rosukhovskiy, D.A. Fluid–structure interactions modeling the venous valve. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1128, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajati, Z.; Moghanlou, F.S.; Vajdi, M.; Razavi, S.E.; Matin, S. Fluid-structure interaction of blood flow around a vein valve. Bioimpacts 2020, 10, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).