Abstract

This study develops a stochastic SIQR epidemic model with mean-reverting Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) processes for both transmission rate and quarantine release rate ; this is distinct from existing non-white-noise stochastic epidemic models, most of which focus on single-parameter perturbation or only stability analysis. It synchronously embeds OU dynamics into two core epidemic parameters to capture asynchronous fluctuations between infection spread and control measures. It adopts a rare measure solution framework to derive rigorous infection extinction conditions, linking OU’s ergodicity to long-term averages. It obtains the explicit probability density function of the four-dimensional SIQR system, filling the gap of lacking quantifiable density dynamics in prior studies. Simulations validate that ensures almost sure extinction, while leads to stable stochastic persistence.

Keywords:

stochastic SIQR model; mean-reverting process; stationary distribution; probability density function MSC:

60H10; 34D05

1. Introduction

Epidemiological modeling is key to understanding disease transmission, predicting outbreaks, and formulating control strategies [1]. Diekmann and Kretzschmar [2] linked transmission to demography; Feng and Thieme [3,4] refined endemic transitions; and Hethcote et al. [5] quantified quarantine efficacy. Traditional deterministic SIQR models [6,7] assume fixed parameters (e.g., constant) but fail to reflect real-world randomness—such as seasonal contact changes, policy adjustments, or medical resource fluctuations—requiring stochastic extensions [8].

where all of the parameters are assumed to be positive and are defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

The definitions of the parameters.

Early stochastic models used white noise for tractability, but its memoryless, unbounded nature contradicts the mean-reverting trend of real epidemic parameters (e.g., stabilizes at a baseline post-outbreak). Ornstein–Uhlenbeck processes, which encode “fluctuation around a central value,” address this, yet existing OU-based studies have critical gaps.

Recent non-white noise stochastic epidemic research has limitations: (1) Quarantine/hospital compartment models focus on determinism, while Zhang et al. [6] only add white noise to , ignoring k’s mean reversion. (2) White noise models [1,8] lack temporal correlation for parameters like seasonal . (3) Non-Gaussian models [9] omit joint (k) stochasticity and explicit compartment density functions.

To fill these gaps, this study develops a stochastic SIQR model with OU processes for both and as follows:

where , and in the same way, . In addition, we write , and . The aim is to (1) capture asynchronous infection-control fluctuations; (2) derive an extinction threshold via OU’s ergodicity; (3) obtain the system’s explicit density function; and (4) validate thresholds via simulations.

This paper systematically investigates the dynamical behavior of stochastic SIQR models with mean-reverting process noise. The analysis is methodologically structured into four principal components: In Section 2, we establish the existence and uniqueness of the global mild solution for the considered system by applying the Banach fixed-point theorem. Subsequently, in Section 3, a Lyapunov function-based approach is employed to demonstrate the existence of a unique stationary distribution for the stochastic system (SI2). Through spectral analysis, we derive the explicit expression in Section 4, which enables us to characterize the extinction thresholds under different parameter regimes. Finally, extensive numerical simulations are conducted to validate the theoretical predictions through comparative analysis of stochastic trajectories and stationary distribution fitting.

2. Existence and Uniqueness of the Global Positive Solution of System (2)

Relevant basic knowledge about existence and uniqueness are found in reference [10], and the main conclusions are as follows.

Theorem 1.

Along with the initial value , there exists a unique solution of model (2) on and the solution will remain in with probability 1, that is, the solution for all a.s..

Proof.

Due to [10], there is a unique local solution on (0, ) for any initial value, where is an explosion time. [11]. To prove that the local solution is global, we only need to prove a.s. Let be sufficiently large for every component of lying within the interval . For each integer , we define the stopping time

we set = ∞. Obviously, increases as . We set ; thus, a.s.; if we show that a.s., then a.s. If a.s., then there are two constants, and , such that Therefore,

we have

and then

Define as follows:

By applying It’s formula [12] to , we have

where

where ; then, we have

Define = for , therefore,

where is the indicator function of . Taking , we have

We have for all almost surely (a.s.). This completes the proof. □

3. Existence of a Stationary Distribution of System (2)

Define a critical value

Theorem 2.

Assuming , the model (2) has a unique stationary distribution under .

Proof.

Define a function

where and are both positive. The specific values of and will be given in the following proofs.

Applying It formula [13] to , then we have

Let , , then we have

where

In addition, applying the I formula to the others, we get

Then we define a non-negative -function ,

where has a minimum . Applying the formula to , then, we have

where is sufficiently large that it satisfies the following conditions

Construct a closed set in the following form

where is sufficiently small that satisfies the following conditions:

Then …, where

Case (1) If , according to Equation (6), we have

Case (2) If , from Equation (7), we get

Case (3) If , by Equation (8), we obtain

Therefore, the global positive solution of system (2) converges as a stationary distribution (·). This completes the proof of Theorem 2. □

4. Density Function and Extinction of System (2)

We define a quasi-equilibrium point for system (2), which is determined by the following equation [4]

where the definition of quasi-equilibrium is similar to that in Section 1.

Theorem 3.

Around the equilibrium of approximately , the stationary distribution has a normal density function along with initial value . Then the specific form of the covariance matrix Σ is as follows.

where

where

where

where ; the other parameters that are not defined will be given specific values in the proof below.

Proof.

Let , , and

Then the corresponding linearized model (10) is written as . According to [13], the probability density function is as follows [14]:

According to G is a constant matrix, we obtain

Since [7], the above equation is written as

where , and .

Define

Before we can prove that is positive definite, the characteristic polynomial of the matrix F takes

where

By the Routh–Hurwitz stability criterion [14], we know that the matrix F has all negative eigenvalues.

Step 1.Consider the equation

Firstly, let ; we have

Next, let ; we have

where , . Then we define ; we have

where , . Define ; we obtain

where , . Let ; then we obtain

where

For the values of and have no influence, we omit them here.

Therefore, the Equation (12) is equivalent to

Let , where ; then, the above Equation (13) can be simplified as

where , by solving Equation (14), we have

where . Since the proof for is similar to the proof for Equation (11), we omit it here. By the proof result of Zhou et al. [15], in Appendix A of his paper, we have that is semi-positive definite. Then, is also a semi-positive definite matrix. Furthermore, there exists a positive constant such that

For the following algebraic equation,

Firstly, we define ; then, we obtain

Define ; then, we have

where , let ; we get

Finally, let ; then we obtain

where

Similarly, we omit , and here. Therefore, Equation (15) is equivalent to

Let , where , then the above Equation (16) can be equivalent to

By solving Equation (17) above, we obtain

According to , by the proof result of Zhou et al. [15], in the Appendix A of his paper, we have that is semi-positive definite. Then, is also a semi-positive matrix. Furthermore, there exists a positive number satisfying

Then, the covariance matrix

Furthermore, the normal density function exists around . □

Theorem 4.

Proof.

According to It’s formula, we have

Integrating this from 0 to t and dividing by t leads to

By [6], we obtain

where , because of ; then, we have

where

The proof is completed. □

5. Numerical Simulations

We study the spread of disease through numerical simulations. Along [6,8], the corresponding discretization equation of model (2) is given by

where .

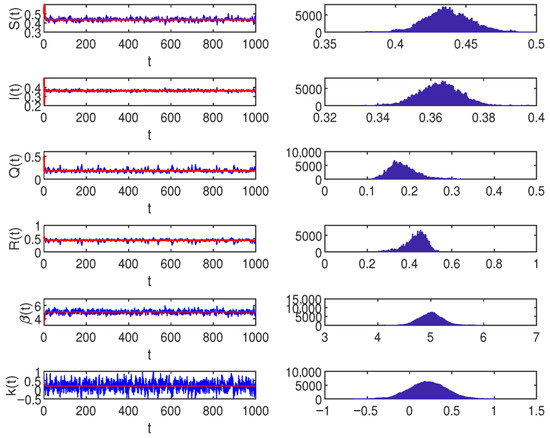

Let the parameters , , , , , , , , , and let the stochastic perturbations , , , . According to Theorem 2, which we have already proven, System (10) has the corresponding conclusion, which can be shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

When , the blue lines represent the simulations under Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process on the left. On the right, the frequency histogram and marginal density function curve of , , , , , , , , , and let the stochastic perturbations , , , in the model (2).

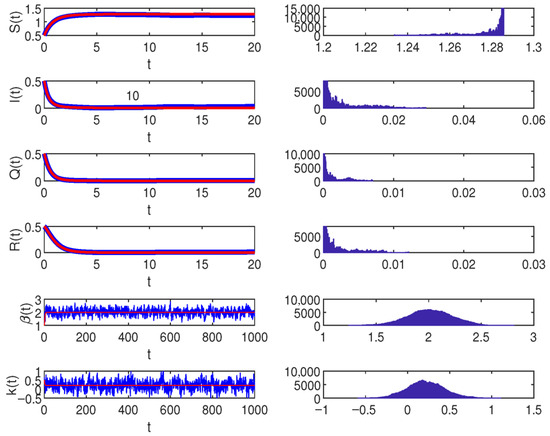

Consider the main parameters , , , , , , , , , and similarly let the stochastic perturbations , , , . According to the results already given in Theorem 4, the infected individuals in system (2) will be extinct, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

When , the blue lines show the simulations under the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process on the left. The right figure presents the density properties with , , , , , , , , , and similarly, let the stochastic perturbations , , , in model (2).

Therefore, the blue shows the simulations of the model (2) and the red indicates the simulation of the system (1). The figure on the right represents the density of the model (2). In Figure 2, when . This similarly means that the system (2) will be extinct.

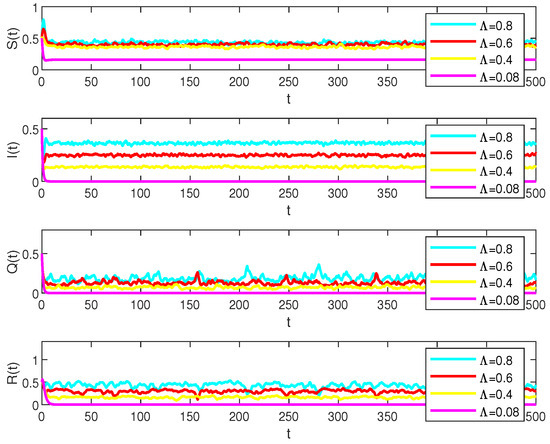

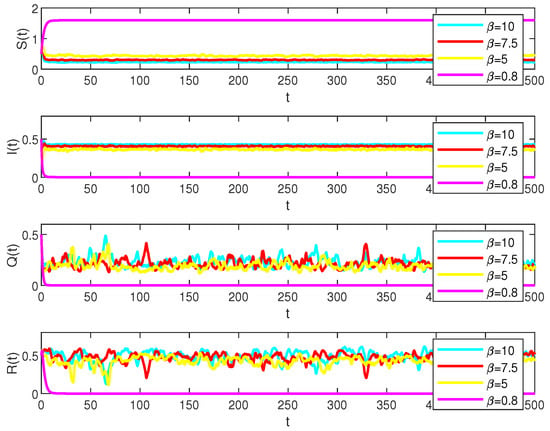

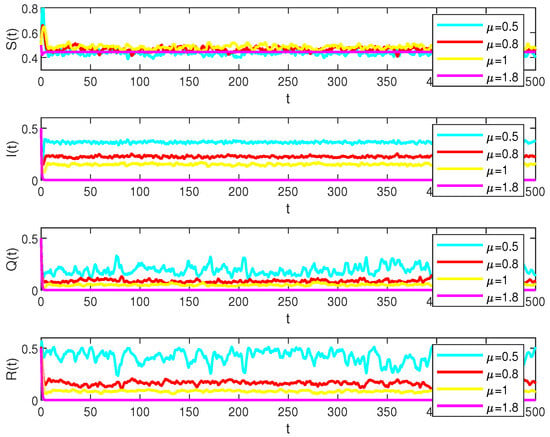

In system (2), parameters , , and play a key role in numerical simulations. By analyzing each of them individually, examples can be found in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 3.

Numerical simulations of the solution S(t), I(t), Q(t) and R(t) in model (2) under the different , , , and values, respectively.

Figure 4.

Numerical simulations of the solutions S(t), I(t), Q(t) and R(t) in system (2) under the different values, , , , values, respectively.

Figure 5.

Numerical simulations of the solution S(t), I(t), Q(t) and R(t) in model (2) under the different values, , , , , respectively.

Let the main parameters , , , , , , , , and let the stochastic perturbations , , , . And

which represents that for , , , the diseases will persist but will be extinct when as in Figure 3.

With the data , , , , , , , , let the stochastic perturbations , , , . And

which illustrates that the diseases will exist when , , but will be extinct when , as in Figure 4.

Consider the parameters , , , , , , , , and let the stochastic perturbations , , , . And

which indicates that for , , , the diseases will persist but will be extinct when , as in Figure 5.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically examines the stochastic dynamics of an SIQR model incorporating a mean-reverting process with parameters . We first establish the existence and uniqueness of a non-negative global solution for the stochastic system using the Banach fixed-point theorem. By constructing a suitable Lyapunov function, we further demonstrate that the system admits a unique stationary distribution in the long-time asymptotic regime. Through detailed analysis of the associated Fokker–Planck equation, we derive the exact probability density function of the system’s state variables, revealing critical insights into the mean-reverting behavior inherent in the mean-reverting process. Subsequently, we determine the extinction threshold for the stochastic epidemic model by analyzing the asymptotic stability of the disease-free equilibrium. This allows us to establish theoretical conditions for effective disease control strategies. Finally, we validate the obtained theoretical results through extensive numerical simulations using the Euler–Maruyama method, comparing the simulated trajectories with the analytical PDF and verifying the extinction criteria under various parameter regimes.

Future work could extend this model by incorporating time-varying contact rates or age-structured populations. Exploring multi-strain dynamics with mean-reverting noise and relaxing the Gaussian assumption for parameters are also promising directions. Additionally, applying the framework to real epidemic datasets (e.g., COVID-19) to calibrate parameters would enhance practical relevance. Meanwhile, we can propose a novel data-driven reliability evaluation method based on the nonlinear Tweedie exponential dispersion process as in [16].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and Z.N.; methodology, H.Z., Z.N., and D.J.; validation, D.J. and J.S.; formal analysis, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.N.; supervision, D.J.; project administration, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities No. 25CX03003A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anderson, R.M.; May, R.M. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, O.; Kretzschmar, M. Patterns in the effects of infectious diseases on population growth. J. Math. Biol. 1991, 29, 539–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, C.W. Handbook of Stochastic Methods for Physics, Chemistry and the Natural Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, S. Dynamic analysis of a stochastic epidemic model incorporating the double epidemic hypothesis and Crowley-Martin incidence term. Electron. Res. Arch. 2023, 31, 6134–6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hethcote, H.W.; Zhien, M.; Liao, S. Effect of Quarantine in Six Endemic Models for Infectious Diseases. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2002, 180, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, M.; Chen, L. Optimal quarantine strategies in stochastic SIR models with white noise. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 67, 3542–3551. [Google Scholar]

- Nirwani, N.; Badshah, V.H.; Khandelwal, R. Dynamical Study of an SIQR Model with Saturated Incidence Rate. Nonlinear Anal. Differ. Equ. 2016, 4, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, D.J. An algorithmic introduction to numerical simulation of stochastic differential equations. SIAM Rev. 2001, 43, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divine, W. Estimating white noise intensity regions for comparable properties of a class of SEIRs stochastic and deterministic epidemic models. J. Appl. Anal. Comput 2021, 11, 1095–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Teng, Z. Dynamical properties and density function in a stochastic epidemic model with incomplete and temporal immunization. Adv. Contin. Discret. Model. 2025, 2025, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Marion, G.; Renshaw, E. Environmental brownian noise suppresses explosions in population dynamics. Stoch. Process. Appl. 2002, 97, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasminskii, R. Stochastic Stability of Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X. Stochastic Differential Equations and Applications; Horwood Publishing: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roozen, H. An Asymptotic Solution to a Two-Dimensional Exit Problem Arising in Population Dynamics. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1989, 49, 1793–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Jiang, D.; Dai, Y.; Hayat, T. Stationary distribution and density function expression for a stochastic SIQRS epidemic model with temporary immunity. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 105, 931–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Du, S. Reliability estimation method based on nonlinear Tweedie exponential dispersion process and evidential reasoning rule. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 206, 111205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).