Abstract

Sulfides are essential tracers for understanding the redox conditions, diffusion processes, and thermal mechanisms involved in the formation of ordinary chondrites. Their mineralogical and textural evolution provides valuable constraints on the metamorphic history of parent bodies. In this context, the Ksar El Goraane meteorite, which fell in Morocco in 2018 and is classified as an H5 ordinary chondrite, represents a particularly instructive case for investigating sulfur behavior during thermal metamorphism. Petrographic observations combined with geochemical data obtained by electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) were used to characterize the main silicate and sulfide phases and to evaluate their degree of chemical equilibration. The compositions of olivine (Fa18–20), Mg-Rich orthopyroxene, and sodic plagioclase (An10–15) display limited analytical dispersion and well-recrystallized textures, confirming that Ksar El Goraane experienced an equilibrated metamorphic grade consistent with an H5 ordinary chondrite. The sulfide assemblage is dominated by troilite (FeS), iron-rich pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS), and pentlandite ((Fe,Ni)9S8), with minor occurrences of pyrite (FeS2). Textural relationships and chemical homogeneity observed in backscattered electron images and elemental maps indicate progressive re-equilibration during thermal metamorphism. Formation and transformation temperatures of the sulfide phases are inferred through comparison with experimental and empirical constraints reported in the literature. These results suggest early high-temperature crystallization of troilite, followed by sulfur depletion leading to pyrrhotite formation, subsequent low-temperature exsolution of pentlandite, and localized late-stage pyrite crystallization.

Keywords:

ordinary chondrite; troilite; pentlandite; pyrrhotite; pyrite; H5; EPMA; SEM; Ksar El Goraane; sulfides 1. Introduction

Ordinary H-type chondrites are considered among the most important indicators of the early stages of planetary formation. The H5 group, characterized by a high iron content and dominated by olivine, exhibits a largely homogeneous texture and mineralogy, reflecting significant re-equilibration between silicate, metallic, and sulfide phases within the parent body [1]. Understanding the origin, transformation, and distribution of iron sulfides in these meteorites is essential, as these phases preserve sensitive information on temperature, oxygen and sulfur fugacity, and the alteration history of their parent bodies [2]. The most common sulfides in ordinary chondrites are troilite (FeS) and, more locally, pentlandite ((Fe,Ni)9S8), sometimes associated with pyrrhotite and, more rarely, pyrite. These sulfide minerals are sensitive tracers of the physicochemical conditions that prevailed in the solar nebula and within parent bodies [3,4,5,6]. Their petrological and mineralogical characteristics provide essential constraints on the thermal evolution and redox conditions of the early Solar System, although the precise conditions of their formation and their relationship with thermal evolution remain subject to debate.Two main modes of sulfide formation are commonly proposed. First, during early nebular condensation [7], metal sulfides may have precipitated directly from the gas phase or formed through gas–solid or gas–gas reactions [8]. Second, thermal metamorphism promoted the crystallization and re-equilibration of sulfides from pre-existing silicate and metallic phases during accretion and internal heating of planetesimals. These processes record the oxygen and sulfur fugacity conditions characteristic of parent bodies [9]. In addition, localized episodes of aqueous alteration may explain some of the complex textures and compositional heterogeneities observed in meteoritic sulfides [10]. Despite extensive studies of sulfides in ordinary chondrites, the detailed paragenesis and thermal evolution of Fe–Ni–S assemblages in H5 chondrites remain debated, particularly with respect to sulfur loss, nickel redistribution, and late-stage redox modifications. In this context, well-characterized meteorite falls provide valuable benchmarks for refining current models of sulfide evolution in equilibrated chondrites. This study focuses on the H5-type meteorite fall observed in Morocco in 2018, known as Ksar El Goraane. The objective is to characterize and interpret the sulfide assemblages of this ordinary chondrite in order to constrain its thermal history. We combine petrographic observations, chemical mapping, and electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to document the textures, spatial distribution, and mineralogical associations of sulfide phases (troilite, pyrrhotite, pentlandite, and pyrite). These analyses also allow us to quantify Fe–Ni–S compositions and Fe/S ratios, providing constraints on sulfide stability fields and redox conditions during parent-body metamorphism.

2. Materials and Methods

The results obtained from the study of the Ksar El Goraane meteorite are based on a combination of macroscopic observations of the sample, microscopic analyses and chemical maps describing the texture of the sample.

2.1. Field Mission

On 11 November 2018, a field mission led by Professors Hassna Chennaoui Aoudjehane and Mohammed Aoudjehane documented the event following the fall of Ksar El Goraane. The team collected detailed testimonies, recorded the coordinates of most of the recovered fragments, and determined the direction of the trajectory as well as the extent and orientation of the dispersion field [11].

2.2. SEM–EDS Analyses

Two thick sections of the Ksar El Goraane meteorite were examined in these laboratories:

- Bayerisches Geoinstitut (BGI), Germany: Observations were carried out using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; Zeiss LEO Gemini 1530, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany), equipped with a backscattered electron detector (CENTAURUS, KE Developments Ltd., Cambridge, UK) and an electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) system (Nordlys II, Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). Data acquisitions were performed at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

- Natural History Museum (NHM), London, United Kingdom: Backscattered electron imaging and EDS elemental mapping were performed using a scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM-IT500, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). A mosaic of images was generated to cover large areas, and elemental maps were used to determine phase distribution and to confirm mineralogical identification.

- University of New Mexico (UNM), United States: The chemical element maps obtained during the initial characterization of the meteorite Ksar El Goraane were integrated into this study. These maps were produced by Carl Agee using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) coupled with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS).

- University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy: A composite image of a thick section of the Ksar El Goraane meteorite was produced by assembling several high-resolution microphotographs, allowing reconstruction of a mosaic of the sample. The image was acquired at the Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, University of Pisa, using a polarizing microscope (Zeiss Axio Imager, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany) in transmitted light, coupled with a digital color camera (Axiocam 105 color, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.3. Electron Microprobe Analysis (EPMA)

At the Bayerisches Geoinstitut (BGI), mineral compositions were determined using a wavelength-dispersive electron microprobe (WD-EPMA; JEOL JXA-8200, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operated under the following conditions: an accelerating voltage of 15 keV and a beam current of 15 nA for oxides and silicates, 20 keV and 20 nA for sulfides and metals. Calibration was performed using appropriate standards for sulfur (S), phosphorus (P), titanium (Ti), chromium (Cr), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), and nickel (Ni), with counting times of 20 to 40 s per element.

2.4. Image Analysis

Images obtained by optical microscopy and backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy (SEM-BSE) were processed using ImageJ/Fiji software (version 2.9.0). Image processing was limited to linear adjustments of brightness and contrast to enhance phase visibility, without modifying the original data. Final figures were prepared using Adobe Photoshop (version 24.0) for labeling and layout, and Canva Professional (web-based version) for graphic formatting. No image manipulation affecting the scientific content of the data was applied.

3. Results

3.1. Ksar El Goraane Description Fall

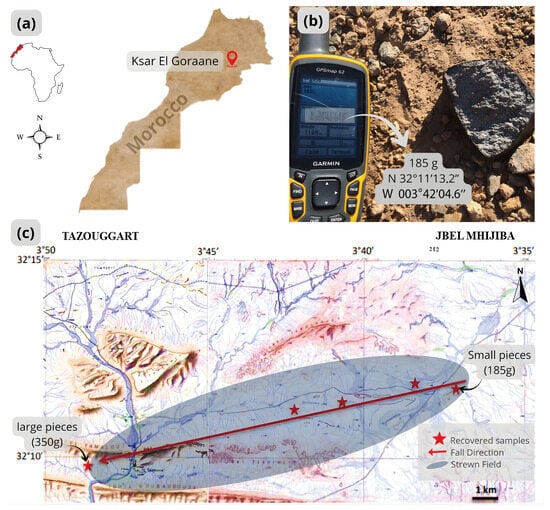

Ksar El Goraane fall was observed on 28 October 2018, at around 22:30 local time (UTC+1), near the village of Ksar El Goraane, in eastern Morocco (Figure 1a). Many witnesses, nomads and residents of the southeastern region, reported seeing a very bright fireball, first yellow then red, moving at low altitude.

Figure 1.

(a) Ksar El Goraane Location in Moroccan Maps. (b) Ksar El Goraane specimen (185 g) and its geographic coordinates. (c) Map of the Ksar El Goraane strewnfield, which extends for about 15 km. Direction of fall from ENE to WSW. This map results from a collage of two topographic maps 1:50,000, Tazouggart and Jbel Mhijiba.

A total mass of 4000 g was recovered after the observed fall of Ksar El Goraane meteorite. This mass is composed of several fragments. A sample weighing 40.4 g was received by the laboratory of the Faculty of Sciences of Casablanca (FSAC), of which 20.4 g were provided by the Moroccan Meteorite Association and 20 g were smaller fragments from a meteorite hunter. Other fragments were deposited at the University of New Mexico (0.9 g) and the University of West Bohemia (21.2 g, including a thin section). Following petrographic and mineralogical analyses, Ksar El Goraane was classified as an H5 ordinary chondrite [12].

3.2. Strewn Field

The first fragment (185 g) was found by a village shepherd the day after the fall, about 5 km east of the village of Ksar El Goraane, near the Izanarzen plateau, south of Djebel Tabouaroust Lakbir and close to Djebel Tabouaroust Essghir (Figure 1b). Most of the medium-sized fragments also come from the Izanarzen plateau, while the smaller specimens were collected further east, on the Essnam plateau. A few days later, the largest fragment (350 g) was discovered near the Kaddoussa dam, west of the Ksar El Goraane village. All of these discoveries suggest a dispersion radius of approximately 15 km, oriented east-northeast to west-southwest (Figure 1c).

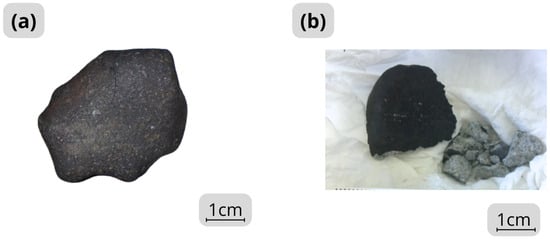

3.3. Physical Description

Numerous fragments were recovered from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite fall site. These fragments have a thin fusion crust that is matte black to slightly shiny (Figure 2a). Smaller specimens sometimes retain remnants of primary and secondary fusion crusts. The interior is gray (Figure 2b). A preliminary examination under optical microscopes reveals the presence of finely granular metallic and sulfide phases in the matrix. The rock has a friable consistency. The overall texture is fine and homogeneous, with no visible signs of brecciation. Scattered chondrules, up to 1 mm in size, are observed in the finely particulate matrix.

Figure 2.

Photographs of hand specimens of Ksar El Goraane. (a) Specimen is entirely covered with a black, matte, and slightly shiny fusion crust. (b) The interior of the specimen is gray in color and the texture of the interior of Ksar El Goraane is friable.

3.4. Petrography and Mineralogy

3.4.1. Chondrules and Matrix

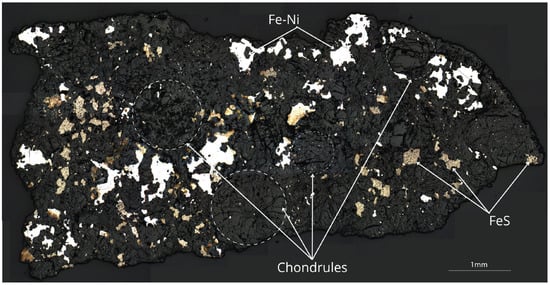

Petrographic analysis of the Ksar El Goraane (H5) meteorite reveals a high abundance of chondrules of various types (Figure 3), with diameters ranging from 0.2 to 1.2 mm and an average size of approximately 0.6 mm. Porphyritic, radial, and barred chondrules with well-defined outlines dominate the polished sections (Figure 3b). This observation is consistent with previous studies indicating that ordinary H-type chondrites generally display smaller average chondrule diameters compared to L and LL groups [13].

Figure 3.

Mosaic of thick section of the Ksar El Goraane meteorite, reflected light image (scale = 1 mm). The dark, weakly reflective matrix has a dense network of microcracks and a fine texture, composed mainly of finely crystallized olivine and pyroxene. The highly reflective white areas corresponding to Fe–Ni metal phases are arranged in irregular clusters with lobed contours. The pale yellow to cream-colored grains, often adjacent to the metal, represent sulfides, mainly troilite, associated with other phases. The opaque metallic and sulfide zones occur as submillimeter to millimeter-sized grains (up to about 0.6–0.8 mm for the largest), heterogeneously dispersed in the matrix. Several metal and sulfide associations form composite aggregates (Fe–Ni–S), with sulfur at the edges or in rounded inclusions in the metal. At the image scale, chondrules of various sizes are dispersed throughout the matrix.

The modal proportions of chondrules and matrix were estimated using a semi-quantitative image analysis performed with ImageJ/Fiji. A total of twelve representative optical and SEM-BSE images from polished sections were analyzed, covering different areas of the sample in order to account for textural heterogeneity. Chondrules and matrix were distinguished based on petrographic criteria, including grain size, morphology, and grayscale contrast in backscattered electron images. Segmentation was carried out manually rather than using automated thresholding. The resulting modal abundances, estimated at approximately 65%–70% chondrules and 30%–35% matrix, represent surface-area proportions and regarded as semi-quantitative, with an uncertainty of about ±5%–10%.

The matrix appears dark in optical microscopy and displays a fine-grained granular texture. It is composed predominantly of recrystallized olivine and pyroxene, homogeneously distributed within the matrix. Plagioclase feldspar is abundant and occurs as well-crystallized grains intergrown with the major silicates.

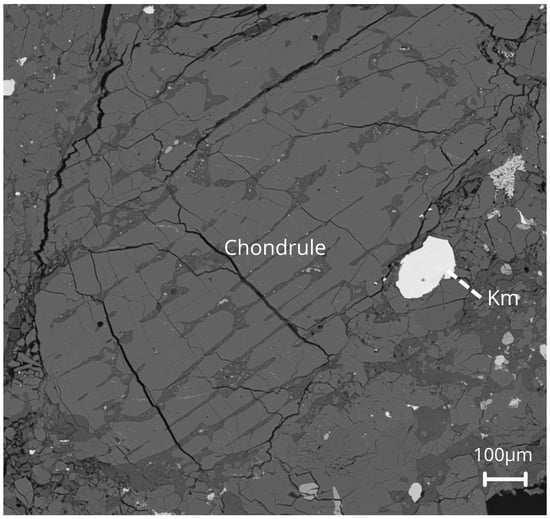

Fe–Ni metal grains (taenite and kamacite) and troilite (FeS) are common constituents of the matrix and show a heterogeneous spatial distribution (Figure 3). These phases commonly occur as irregularly shaped grains, locally reaching sizes of up to one millimeter, and are frequently observed in close association (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Backscattered electron image of a porphyritic chondrule in Ksar El Goraane (H5). The chondrule has a subrounded outline truncated by small fractures. The internal domains show weakly defined banding that alternates between olivine and pyroxene. The bright phases along the fractures correspond to Fe–Ni metal and sulfides. Scale: 100 µm.

In addition, irregularly shaped and locally fractured chromite nodules are present within the chondritic lithologies. These nodules are commonly associated with Fe–Ni metal grains within chondritic fragments.

3.4.2. Mineral Compositions

Olivine: EPMA analyses of olivine based on six spot measurements indicate a composition dominated by SiO2 (38.79 wt%), MgO (43.22 wt%), and FeO (17.97 wt%), with very low concentrations of minor and trace components (TiO2, Al2O3, CaO, P2O5, and CoO, all ≤ 0.05 wt%; Table 1). The total oxide contents sum to 100.54 wt%.

Table 1.

Average chemical composition of olivine (n = 6) from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite (H5). The contents are expressed in wt%; “n.d.” = not detected. Std. dev. refers to the standard deviation of the analytical totals.

The calculated molar proportions (Fo and Fa) indicate a magnesium-rich olivine with a moderate fayalite component, which is characteristic of ordinary H5 chondrites [14]. The low abundance of minor elements suggests that the analyzed olivines represent a chemically homogeneous phase. This interpretation is further supported by the low standard deviation of the total oxide content (Std. dev. = 0.28), consistent with the equilibrated olivine compositions typically produced by thermal metamorphism in H5 chondrites.

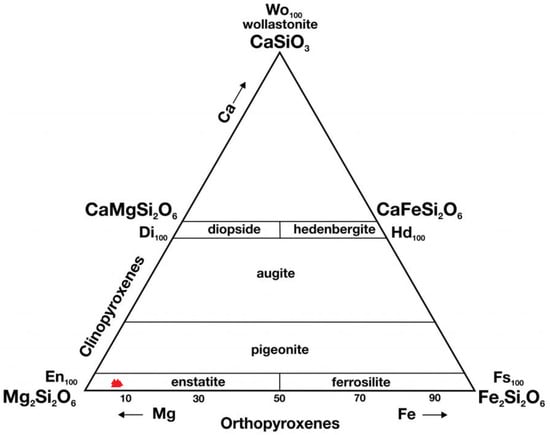

Pyroxene: The average composition in pyroxene from Ksar El Goraane is shown in Table 2. The high silica (55.91%) and magnesium (31.17%) contents, combined with a significant iron content (11.35%), indicate a balance between magnesium and iron components, characteristic of a ferromagnesian pyroxene dominated by orthopyroxene. The low concentrations of CaO (0.68%) and Al2O3 (0.21%) show minimal integration of calcium and aluminum into the crystal structure, which is typical of orthopyroxenes (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Average chemical composition of pyroxene from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite (H5). Oxides are expressed in wt%. A total of 13 analyses were performed. Std. dev. refers to the standard deviation of the analytical totals.

Figure 5.

Ternary diagram (En–Fs–Wo) of pyroxenes from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite (H5). the small red triangles on the diagram correspond to the position of magnesian enstatite (En91Fs8Wo1). En: enstatite; Fs: ferrosilite; Wo: wollastonite.

According to the calculation of the average composition, which was performed on 13 points analyzed, the result is En91Fs8Wo1 (Mg = 0.47), which corresponds to a magnesium-rich orthopyroxene (enstatite) with a moderate iron component.Therefore, the measured standard deviation of Pyroxene (Std. dev. = 0.45) is consistent with the petrographic classification of Ksar El Goraane as an H5 chondrite.

Plagioclase: Plagioclase in the Ksar El Goraane meteorite displays a sodium-rich composition, marked by low calcium contents and a minor potassium component (Table 3). Concentrations of FeO, MgO, TiO2, P2O5, MnO, and CoO are close to analytical detection limits, indicating negligible incorporation of these elements into the feldspar lattice and supporting the interpretation of a chemically high-purity plagioclase. Molar proportions calculated from Na2O, CaO, and K2O contents yield dominant albite (Ab83.1), with subordinate anorthite (An10.9) and orthoclase (Or6.0), confirming the sodic character of the feldspar with moderate Ca substitution. The limited compositional dispersion observed (Std. dev. = 0.47) indicates a homogeneous plagioclase composition, consistent with equilibrated mineral assemblages typical of ordinary H5 chondrites [15].

Table 3.

Average chemical composition of plagioclase (n = 5). Values are expressed as a percentage. Std. dev. refers to the standard deviation of the analytical totals.

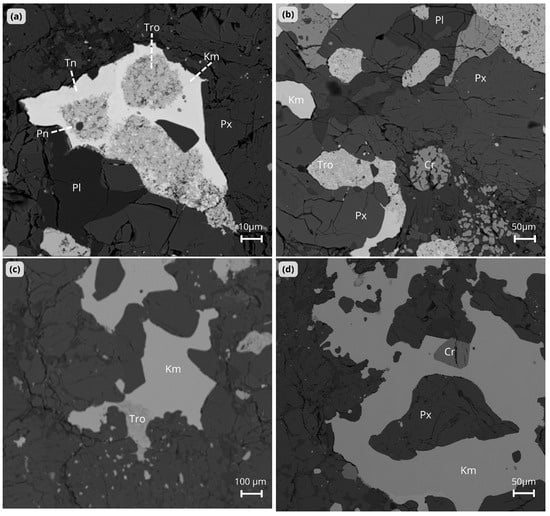

Chromite: The chromite from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite is characterized by a very high chromium content (Cr2O3 = 57.6% by weight) and low concentrations of magnesium and aluminum, together with a notable TiO2 content of approximately 2.2% (Table 4). It occurs as small, irregular to sub-spherical grains that are locally fractured and dispersed throughout the section. These grains are commonly spatially associated with Fe–Ni metallic alloys (kamacite and taenite) and, more locally, with troilite (Figure 6b).

Table 4.

Average chemical composition of chromite (n = 13). Values are expressed as % by W; “n.d.” = not detected.

Figure 6.

BSE images of Ksar El Goraane (H5). (a) The kamacite (Km) domain contains scattered lamellae of taenite (Tn) and zones of troilite (Tro). The metal is present at the interface between plagioclase (Pl) and pyroxene (Px). (b) Distribution of kamacite (Km), troilite (Tro), and silicates in the polished section. Chromite (Cr) nodule with fractured edges (dotted circle) appears in a pyroxene-rich zone (Px) near the plagioclase (Pl). (c) Kamacite (Km) grain with troilite (Tro) at the edge of the metal, forming a metal–sulfide association in a silicate matrix. (d) A large grain of kamacite (Km) surrounding pyroxene (Px). The presence of a small grain of chromite (Cr) indicates that the metal, sulfides, and silicates are closely associated. Km = kamacite; Tn = taenite; Tro = troilite; Cr = chromite; Pl = plagioclase; Px = pyroxene; Pn = pentlandite.

3.4.3. Metal Composition and Texture

EPMA analysis of the metallic phases carried out at the BGI (Table 5) indicates that kamacite is the dominant metallic phase in the Ksar El Goraane meteorite. Characterized by a low Ni content, this phase has an average composition of 7.5 ± 5.3% Ni and a high Fe/Ni atomic ratio of approximately 12.3, which corresponds to a nickel-poor -(Fe–Ni) alloy. These chemical characteristics are consistent with SEM observations (Figure 6), which reveal large continuous metallic domains, generally reaching the millimeter scale (see also Figure 3). A secondary metallic phase corresponds to taenite, the Ni-rich -(Fe–Ni) alloy. Taenite has an average composition of 29.9 ± 3.2% Ni and a lower Fe/Ni ratio of approximately 2.3. In terms of texture, taenite mainly occurs in the form of fine lamellae or rims at the grain boundaries of kamacite (Figure 6b) and locally forms crown textures around FeS (troilite).

Table 5.

Average atomic composition (at.%) of Fe–Ni metallic phases from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite determined by EPMA. Values are given as mean ±1.

3.4.4. Sulfide Phases

The EPMA analyses performed in the BGI on the Ksar El Goraane meteorite reveal a complex sulfide assemblage. This assemblage consists mainly of troilite (FeS), pentlandite ((Fe, Ni)9S8) as the main Ni-bearing phase, pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS), and minor pyrite (FeS2).

Troilite (FeS): Average EPMA analyses of sulfides from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite indicate sulfur contents ranging from 33.2 to 34.02 wt% and iron contents between 65.8 and 66.4 wt%. Minor amounts of Mn are detected (≤0.13 wt%), whereas Ni is present at low but variable levels (0.06–0.92 wt%), and remains below detection limits in some analyses.

The calculated Fe/S atomic ratios cluster tightly around unity, with an average value of 1.13, confirming that troilite (FeS) is the dominant sulfide phase.

The low standard deviations obtained for sulfur (0.31 wt%), iron (0.22 wt%), and manganese (0.05 wt%) indicate a chemically homogeneous troilite population. The slightly higher variability observed for Ni ((mean = 0.57 wt%); (std = 0.38 wt%)) reflects limited Ni substitution within the troilite structure. Overall, the compositional homogeneity of the sulfide assemblage is consistent with the classification of Ksar El Goraane as an H5 ordinary chondrite (Table 6).

Table 6.

EPMA elemental compositions (wt%) of troilite in the Ksar El Goraane meteorite (n = 6).

Pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS): EPMA analyses of pyrrhotite show relatively homogeneous average values, with sulfur contents of 29.88 wt%, iron contents of around 68.79 wt%, and an average Fe/S ratio of 1.32. These results indicate the presence of pyrrhotite that is slightly depleted in sulfur (Table 7).

Table 7.

EPMA results for pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS) from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite. All values are in wt%.

Pentlandite((Fe,Ni)9S8): EPMA analyses of pentlandite show the following compositions: S = 31.98 ± 1.33 wt%, Ni = 14.87 ± 1.71 wt%, Fe = 53.10 ± 0.54 wt% (n = 3), with an atomic Fe/S ratio of 0.96 ± 0.04. This composition corresponds to pentlandite intercalated with an Fe–S phase (troilite/pyrrhotite). These results are consistent with the H5 classification of the Ksar El Goraane meteorite (Table 8).

Table 8.

EPMA results for pentlandite ((Fe,Ni)9S8) from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite. All values are in wt%.

Pyrite (FeS2): The average EPMA analyses of the pyrite from the meteorite of Ksar El Goraane show sulfur contents ranging from 48.5 to 49.6 wt% and iron contents between 50.3 and 51.5 wt% (Table 9). Minor elements such as Ni, Mn, Ti, and P are present in trace amounts close to the analytical detection limits, indicating minimal substitution in pyrite structure. The calculated Fe/S atomic ratios range from 0.58 to 0.61, with a mean value of 0.594, which is consistent with stoichiometric pyrite (FeS2). The small standard deviations for sulfur (0.35 wt%) and iron (0.37 wt%) indicate that pyrite is homogeneous.

Table 9.

EPMA results for pyrite (FeS2) from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite. All concentrations are given in wt%.

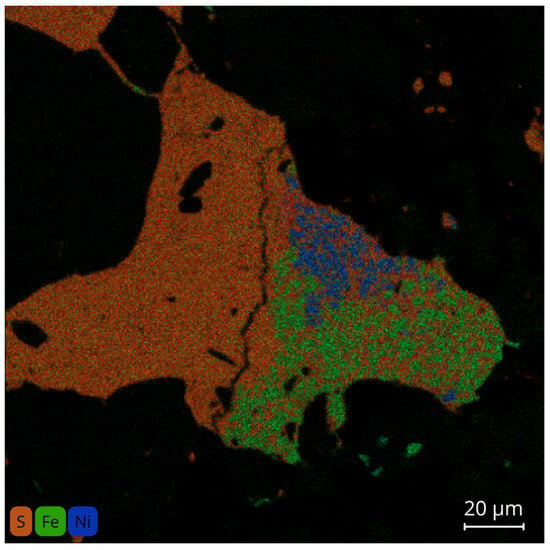

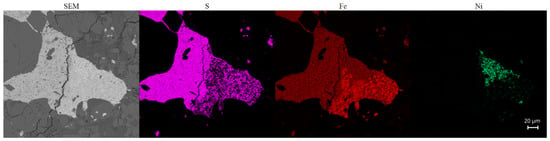

3.4.5. Distribution of Elements Based on Chemical Mapping

The chemical map (Figure 7 and Figure 8), obtained using MEB X-Rey, shows a false-color composite of the elemental distribution: sulfur is red/orange, iron is green, and nickel is blue. The dominant Fe (green) in the central zone is locally bordered by Ni (blue) enrichments, creating borders at the metal level, while the sulfur-rich areas (red/orange) indicate the presence of nearby sulfides. This textural arrangement highlights the close association between Fe–Ni metal phases (kamacite and taenite) and Fe-rich troilite/pyrrhotite, with local enrichment of Ni observed along their interfaces.

Figure 7.

X-Ray maps of elemental intensity of Ksar El Goraane representing the superposition of S–Fe–Ni in the metal–sulfide assembly.

Figure 8.

SEM-EDS chemical maps of pyrite from Ksar El Goraane: distribution of sulfur, iron, and nickel in the metal-sulfide assemblage. The S domain has a sulfur-rich envelope around a heterogeneous core. The Fe channel highlights a central domain enriched in iron, characteristic of pyrrhotite. The Ni domain reveals a localized zone of pentlandite concentration along fractures. The juxtaposition of a high S and Ni content locally with an Fe content slightly lower than that of the core is typical of pentlandite exsolution in a pyrrhotite matrix.

4. Discussion

4.1. Chemical and Textural Homogeneity of Silicates: Confirmation of H5 Metamorphic Grade

The olivines from Ksar El Goraane have a Fa18−20 composition (Table 1), which is typical of H-type chondrites [16]. Pyroxene is characterized by a dominant enstatite composition, indicating an Mg-rich orthopyroxene (Table 2). Finally, the plagioclases have compositions of An10−15 (Table 3), indicating well-crystallized feldspar. The reduced standard deviations observed for the three phases reflect chemical homogenization, which is consistent with grade 5 thermal metamorphism [17,18]. SEM (BSE) imaging confirms these results (Figure 3 and Figure 6): the silicates form a recrystallized polygonal mosaic. The chondrule boundaries are diffuse to truncated, and the matrix is dominated by crystalline feldspar, corresponding to the crystallization of plagioclase during the thermal heating characteristic of H5 chondrites [19,20]. The chromite present in the Ksar El Goraane meteorite appears as a minor accessory phase. The grains analyzed are characterized by a high Cr2O3 content and low Al2O3 and MgO content, which is typical of balanced H-type ordinary chondrites [21]. The number of spot analyses performed for each mineral phase is limited which is commonly applied in studies on H5 type balanced ordinary chondrites. The purpose of these analyses is therefore to confirm and refine the classification of Ksar El Goraane.

4.2. Ksar El Goraane Meteorite Sulfide Assemblage

EPMA analyses performed on the sulfides from the Ksar El Goraane meteorite reveal an assemblage consisting, in order of abundance, of troilite (FeS) as the main phase, pentlandite ((Fe,Ni)9S8) as the main nickel carrier, iron-rich pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS), and local occurrences of pyrite (FeS2), which represents a minor phase. Chemical maps (Figure 7) provide spatial confirmation of this paragenesis, illustrating the co-localization and elemental partitioning of S, Fe, and Ni at the grain scale, and thereby supporting the mineralogical interpretations discussed above.

Troilite is the dominant sulfide phase identified in the Ksar El Goraane meteorite. As in most ordinary chondrites, it formed either by crystallization from a sulfur-enriched metallic liquid or by direct reaction between metallic iron and sulfur at temperatures above 900 °C as inferred from experimental and empirical constraints reported in the literature [22]. Its stability within Ksar El Goraane suggests a generally reducing environment during the formation of sulfide phases. Troilite frequently contains traces of nickel (Table 6), resulting from limited exchanges with Fe–Ni alloys, as well as minor elements such as titanium and manganese. These slight enrichments reflect restricted diffusion processes between the metal and sulfide during the gradual cooling of the parent body. Such behavior is typical of ordinary H-type chondrites that have undergone moderate to high thermal metamorphism, where troilite remains the dominant sulfide phase within the mineralogical assemblage [23].

Pyrrhotite is an iron-rich, sulfur-deficient sulfide relative to stoichiometric troilite, and is commonly observed in ordinary chondrites as part of the Fe–S mineral assemblage (Table 7). Their textural association suggests a coeval formation under equilibrium conditions at intermediate temperatures, estimated between 400 and 600 °C, this temperature range being derived from previously published experimental and phase equilibrium studies [24], before the closure of the iron and sulfur diffusion systems. This behavior is characteristic of ordinary H5 chondrites, in which pyrrhotite generally forms as a result of a slight loss of sulfur due to the depletion of volatile elements during thermal metamorphism.

Pentlandite((Fe,Ni)9S8) typically forms at low temperatures, below 300 °C, as inferred from literature-based experimental and thermodynamic models of the Fe–Ni–S system, by exsolution from a monosulfide solid solution [25,26]. In the Ksar El Goraane meteorite, it occurs at the edges of sulfide grains and along fractures or micro-interfaces in contact with Fe–Ni alloys (Figure 8) (Table 8). This textural arrangement indicates a late event of nickel redistribution between metallic and sulfide phases, occurring after the slow cooling of the parent body. This process facilitated Ni diffusion from Fe–Ni alloys into sulfides. The occurrence of pentlandite, thus, serves as an important indicator of cooling dynamics and late redox evolution in ordinary chondrites.

Pyrite (FeS2) is a rare sulfide phase in ordinary chondrites and is generally interpreted as a late product at low temperatures forming under conditions slightly more oxidizing than those stabilizing troilite and pyrrhotite [27]. In the meteorite of Ksar El Goraane, pyrite is locally present as small interstitial grains associated with troilitis, pyrrhotite, pentlandite and Fe–Ni, without evidence of hydrated minerals or ubiquitous secondary alteration. Its textural relationships suggest a formation by sulfur enrichment localized during an episode of weak post-metamorphic reequilibration at very low temperatures (300–400 °C), probably induced by heterogeneous redox conditions as suggested by previous studies [28]. The occasional appearance of pyrite adjacent to Fe–Ni alloys and pentlandite (Figure 8) reflects the gradual closure of diffusive exchanges and the development of fine-scale chemical zoning, marking the last stage of the evolution of sulfides in the Ksar El Goraane.

Sulfide assemblages and similar developments have been observed in several ordinary H5 chondrites. Studies conducted on well-identified H5 meteorites [29], such as Kernouvé and Richardton, show the predominance of troilite, the presence of sulfur-depleted pyrrhotite, and the formation of pentlandite during cooling below the solidus point resulting from the redistribution of Ni in the Fe–Ni–S system [30]. These observations confirm a model of progressive thermal metamorphism followed by slow cooling of the parent body, which corresponds to the characteristics of the sulfides observed at Ksar El Goraane. The weak and localized presence of pyrite observed in some H5 chondrites has also been interpreted as a late redox rebalancing at low temperatures [31].

5. Conclusions

The evolution of sulfide phases in the Ksar El Goraane meteorite can be interpreted within the framework of progressive thermal metamorphism of its parent body. Petrographic observations and EPMA data presented in this study document a sulfide assemblage dominated by troilite, pyrrhotite, and pentlandite, with minor pyrite, recording a multi-stage paragenetic evolution. troilite, the dominant high-temperature sulfide phase (>900 °C), as inferred from experimental and empirical constraints reported in the literature, formed through direct interaction between metallic iron and sulfur. The subsequent development of iron-rich pyrrhotite indicates partial sulfur loss during metamorphism at intermediate temperatures (400–600 °C), with this temperature range being deduced from published phase-equilibrium and experimental studies rather than from direct measurements in this work. During continued cooling, nickel diffusion and redistribution within the Fe–Ni–S system led to the late formation of pentlandite at low temperatures (<300 °C), as inferred from literature-based experimental and thermodynamic models, commonly in association with Fe–Ni alloys. Localized occurrences of pyrite indicate a final stage of redox rebalancing under slightly more oxidizing conditions, interpreted on the basis of textural observations in this study and supported by literature data. This late transformation likely resulted from minor, localized post-metamorphic processes affecting the sulfide assemblage during the final stages of cooling, without evidence for pervasive secondary alteration. Overall, this multi-stage evolution suggests that Ksar El Goraane experienced slow cooling, limited alteration, and the development of late-stage redox heterogeneities at the micrometric scale.

Author Contributions

S.A.: Writing—review and editing; Writing—original draft preparation; Visualization; Software; Methodology; Investigation; Formal analysis; Data curation; Conceptualization. H.C.A.: Writing—review and editing; Validation; Supervision; Project administration; Formal analysis. A.B.: review and editing; Validation; Supervision; Resources; Methodology; Investigation; Formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the BGI, which provided a one-month research stay at its laboratory. This support enabled the analytical work carried out on the Ksar El Goraane meteorite and other Moroccan meteorite falls, from which most of the results presented in this article were obtained.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the research work of the ATTARIK Foundation for Meteoritics and Planetary Science. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the Bayerisches Geoinstitut (BGI) for providing financial support. Special thanks are also extended to the Barringer Crater Company and the Europlanet Society. I am deeply grateful to Carl Agee (University of New Mexico), Sara Russel (Natural History Museum, UK), Amy Riches (The University of Edinburgh), and Driss Takir (NASA) for their valuable assistance, scientific input, and support throughout this research. Their collaboration was essential to the successful completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gully, M.; Liu, S.; Liu, X. Chemical-petrographic types and shock metamorphism of 184 Grove Mountains equilibrated ordinary chondrites, including H5 types with strongly homogenized mineral chemistry. Minerals 2021, 8, 240. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano-Cambero, C.E.; Trigo-Rodríguez, J.M.; Blum, J.; Bischoff, A.; Hezel, D.C.; Metzler, K.; Ebert, M.; Scherer, P.; Gritsevich, M.; Kohout, T.; et al. Thermal metamorphism and chemical equilibration in ordinary chondrites: Constraints from coordinated microanalysis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2019, 246, 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, L.; Fedkin, A.V. Condensation of rock-forming minerals from solar nebular gas. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 287, 275–299. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Eiler, J.M. Temperatures and compositions of early solar system reservoirs from clumped-isotope studies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2019, 246, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolensky, M.E.; Le, L. Iron–nickel sulfide compositional ranges in chondrites: Troilite, pyrrhotite, and pentlandite. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2003, 38, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, D.L.; Davidson, J.; McCoy, T.J.; Zega, T.J.; Russell, S.S.; Domanik, K.J.; King, A.J. The Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite-group sulfides in chondrites: An indicator of oxidation and implications for small body formation conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 303, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrader, D.L.; Davidson, J.; McCoy, T.J. Widespread evidence for high-temperature formation of pentlandite in chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2016, 189, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooden, D.H.; Ishii, H.A.; Zolensky, M.E. Cometary dust: The diversity of primitive refractory grains. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2017, 375, 20160260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, D.L.; Zega, T.J.; Davidson, J.; McCoy, T.J. Petrographic and compositional indicators of formation and alteration conditions from LL chondrite sulfides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2019, 265, 208–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brearley, A.J. The action of water. In Meteorites and the Early Solar System II; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2006; pp. 587–624. [Google Scholar]

- Chennaoui Aoudjehane, H.; Agee, C.B. Ksar El Goraane (H5): The Latest Moroccan Meteorite Fall on 2018. In Proceedings of the 82nd Annual Meeting of the Meteoritical Society, Sapporo, Japan, 7–12 July 2019. LPI Contribution No. 2157. [Google Scholar]

- Gattacceca, J.; McCubbin, F.M.; Bouvier, A.; Grossman, J.N. The Meteoritical Bulletin, No. 108. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2020, 55, 1146–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.M.; Montalvo, P.E.; Watkins, J.; Rivers, M. Size-Frequency Distributions and Physical Properties of Chondrules in Ordinary Chondrites from 3D X-ray Microtomography. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2022, 57, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, A.E. Kamacite and olivine in ordinary chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1990, 54, 1217–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brearley, A.J.; Jones, R.H. Chondritic meteorites. In Planetary Materials; Papike, J.J., Ed.; Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry; Mineralogical Society of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; Volume 36, pp. 3-1–3-398. [Google Scholar]

- McSween, H.Y.; Sears, D.W.G.; Dodd, R.T. Thermal metamorphism of ordinary chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1991, 55, 211–258. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schmus, W.R.; Wood, J.A. A chemical–petrologic classification for the chondritic meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1967, 31, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, M.K.; McCoy, T.J.; Krot, A.N. Systematics and Evaluation of Meteorite Classification. In Meteorites and the Early Solar System II; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2006; pp. 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, R. Meteorites: A Petrologic, Chemical and Isotopic Synthesis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, T.L.; Grossman, J.; McCoy, T.J.; Greenwood, R.C.; Franchi, I.A.; Benedix, G.K.; Al Kathiri, A. Analysis of ordinary chondrites using powder X-ray diffraction: 2. Mineral chemistry of olivine and low-Ca pyroxene in equilibrated ordinary chondrites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2010, 45, 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bunch, T.E.; Keil, K.; Snetsinger, K.G. Chromite composition in ordinary chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1967, 31, 1569–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauretta, D.S.; Lodders, K. The cosmochemistry of sulfides in chondritic meteorites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 1997, 32, A76–A77. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, A.G.; Johnson, T.E.; Mitchell, J.T. A review of the chondrite–achondrite transition, and a metamorphic facies series for equilibrated primitive stony meteorites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2020, 55, 1254–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, D.L. The Fe/S ratio of pyrrhotite-group sulfides in chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 307, 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Etschmann, B.; Pring, A.; Putnis, A.; Grguric, B. A kinetic study of the exsolution of pentlandite (Ni,Fe)9S8 from the monosulfide solid solution (Fe,Ni)S. Am. Mineral. 2004, 89, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewman, R.W. Pentlandite phase relations in the Fe–Ni–S system and implications for sulfide exsolution. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1970, 7, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.E. Mineralogy of meteorite groups. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 1997, 32, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldrett, A.J. The central portion of the Fe–Ni–S system and its bearing on sulfide ore genesis and chondrite metal–sulfide associations. Econ. Geol. 1967, 62, 826–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.R.D.; Taylor, G.J. Chondrites and the protoplanetary disk. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1983, 47, 1647–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauretta, D.S.; Kremser, D.T.; Fegley, B. Thermodynamic constraints on sulfide formation in ordinary chondrites: The Fe–Ni–S system. Icarus 1996, 122, 288–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSween, H.Y., Jr.; Huss, G.R. Cosmochemistry: Probing the Origin and Chemical Evolution of the Solar System; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.