Abstract

The flotation effect of the new collector, 2-octylthio(aniline) (2-OA), on two types of sulfide ores under various conditions was investigated and compared with that of the conventional collector, potassium amyl xanthate (PAX). Collector 2-OA showed better floatability in copper sulfide ore flotation, and the copper grade could be enriched up to 1.5 times the original ore during the secondary flotation of copper sulfide ore. Compared to PAX, 2-OA demonstrated a stronger ability to collect copper than iron. Furthermore, in the flotation of gold sulfide ore, a 13% higher gold recovery was achieved with 2-OA than with PAX. Surface chemical analysis showed that 2-OA altered the surface charge of minerals and formed Cu–S and Cu–N bonds on the chalcopyrite surface. The adsorption capacity of 2-OA exceeded that of PAX, thereby enhancing the flotation effect. Overall, 2-OA exhibits better flotation performance and potentially serves as an efficient collector for sulfide ore flotation.

1. Introduction

Polymetallic sulfide ores are the most important group of ore minerals that serve as the raw material for most non-ferrous metal supplies in the world [1]. Flotation is one of the main methods used for mineral processing. Almost all nonferrous sulfide ores can be recovered by flotation [2,3,4]. During the flotation process, the hydrophobicity of the surfaces of different minerals is changed by adding an appropriate amount of flotation reagents, enabling the target minerals to be selectively separated from vein minerals. Therefore, flotation reagents, particularly collectors, play an important role in flotation [5].

Xanthate is the most widely used and representative collector in the flotation of sulfide ores. It possesses a long history of industrial application and stable flotation behaviors. In addition, dithiophosphate is also a common collector for sulfide ores, which is often used as a composite to enhance the collecting ability and selectivity of the xanthate system due to its high price. Thiocarbamate and dithiocarbamate are often used as supplemental collectors to improve metal grades during flotation. Their performance is different regarding mineral selectivity and recovery efficiency, and they can be optimally combined according to the properties of ores [6]. However, with the increasing complexity of mined ores in recent years, the poor selectivity of xanthates has made it difficult to efficiently separate target minerals such as chalcopyrite from pyrite or oxidized gangue minerals, thus limiting their flotation performance [7,8]. Furthermore, oxide minerals such as silicates are prone to forming hydrophilic layers on their surfaces, which significantly hinders the adsorption of collectors on mineral surfaces [9]. In contrast, non-oxidized minerals such as chalcopyrite possess predominantly sulfide surfaces with inherent hydrophobicity. Their flotation performance relies more heavily on the selective differences between collectors for the target sulfide minerals and gangue minerals. This further emphasizes the critical importance of developing highly efficient collectors [10]. As a result, some researchers have focused on the development of novel collectors [11,12]. These are designed to improve the flotation effect of complex sulfide ores through stronger coordination or higher selectivity. In general, the current collectors for sulfide ores are evolving from the traditional universal type to new functionalized reagents with adjustable structure and more accurate interfacial control ability.

The structure of the new collector, 2-(octylthio)aniline (2-OA), is dominated by a hydrophobic benzene ring carrying -S and -NH2 with a metallophile and a long alkyl chain with hydrophobicity. However, amine collectors typically present some environmental concerns, including higher toxicity and poor biodegradability, which may cause pollution in industrial operations [13]. However, compared to conventional collectors, 2-OA can achieve higher recovery while using lower dosages, thereby potentially reducing the environmental impact while maintaining flotation performance. For example, in chalcopyrite flotation, the use of collector 2-OA increased copper recovery by 25% compared to PAX at the same dosage [14]. However, the flotation effect of 2-OA on other types of ores, such as sulfide ores of different grades or those containing other metals, has not yet been verified. In recent years, the grades of available ores have decreased, and their composition has become more complex [15,16,17]. Several studies have focused on utilizing low-grade and polymetallic ores [18,19,20]. Therefore, a comprehensive experimental discussion on the flotation effect of 2-OA was carried out in this study. To confirm the effectiveness of 2-OA on different sulfide ores, flotation tests under different flotation parameters, such as pulp pH, collector dosage, particle size, and pulp density, were conducted on two different grades of copper sulfide ores and a gold sulfide ore. Flotation kinetics were studied on the copper sulfide ore using collectors 2-OA and PAX to investigate the flotation behavior. Moreover, continuous secondary flotation was performed on the copper sulfide ore to confirm the copper enrichment ability of collector 2-OA. A conventional xanthate collector PAX was utilized for comparative studies. Additionally, zeta potential, FTIR, and adsorption tests were employed to explain the difference in flotation performance by investigating the collectors’ flotation behaviors.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

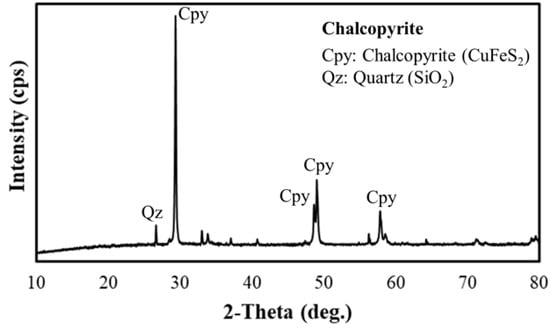

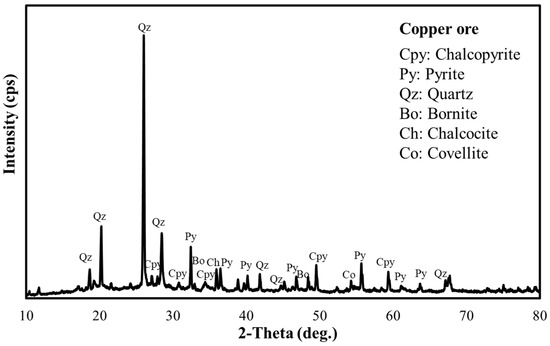

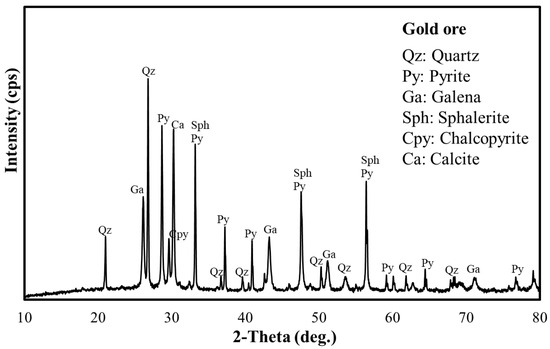

A chalcopyrite sample from Acari mine in Peru, a copper sulfide ore from a mine in Chile, and a polymetallic gold sulfide ore, from a mine in Southeast Asia were used in this study. The original ores were dry crushed using a jaw crusher (P-1, Fritsch, Yokohama, Japan) and ground using a disc mill (P-13, Fritsch). Chalcopyrite, a mineral sample of high purity, was used to study the adsorption behavior of collectors on mineral surfaces. Copper ore was employed to validate the flotation performance of the new collector 2-OA on actual ore due to its complex composition. Gold ore, as a representative sulfide ore, was utilized to verify the performance of 2-OA across different types of sulfide ores. A vibrating screen (AS200 digits, Retsch, Tokyo, Japan) was then used for size classification to the particle size below 75 μm (P80 = 73.6 μm for the copper ore and P80 = 72.5 μm for the gold ore, MT3000 II, Microtrac, Osaka, Japan). Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the X-ray diffraction (XRD, RINT–2200V, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) patterns of chalcopyrite, copper ore, and gold ore, respectively. The main chemical compositions of the three types of ores were analyzed using an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF, Rigaku ZSX Primus II) and a Micro Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer (MP-AES, Agilent 4210, Agilent, Tokyo, Japan), as listed in Table 1. Copper ore was used in both the primary and secondary flotation tests, whereas gold ore was only used in the primary flotation stage.

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of chalcopyrite (Chalcopyrite 93%; Quartz 3.5%).

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of copper ore (Pyrite 31%; Quartz 30%; Bornite 5%; Chalcocite 3%; Chalcopyrite 1%).

Figure 3.

XRD pattern of gold ore.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of the three sulfide ores.

The new collector, 2-(octylthio)aniline (2-OA), with high analytical purity, was synthesized in the laboratory following a previously reported procedure [10]. In brief, the starting material 2-aminobenzenethiol was reacted with 1-bromooctane and potassium hydroxide (KOH) as a catalyst in acetone under reflux with nitrogen gas. The products after the reaction were washed with water, dehydrated with anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), and dried under vacuum at 100 °C for 12 h. The conventional collector, potassium amyl xanthate (PAX, 97%, Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), was used in this study to compare the flotation effect with that of the new collector 2-OA. The main properties of collectors 2-OA and PAX are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main properties of collectors 2-OA and PAX.

2.2. Flotation Experiments

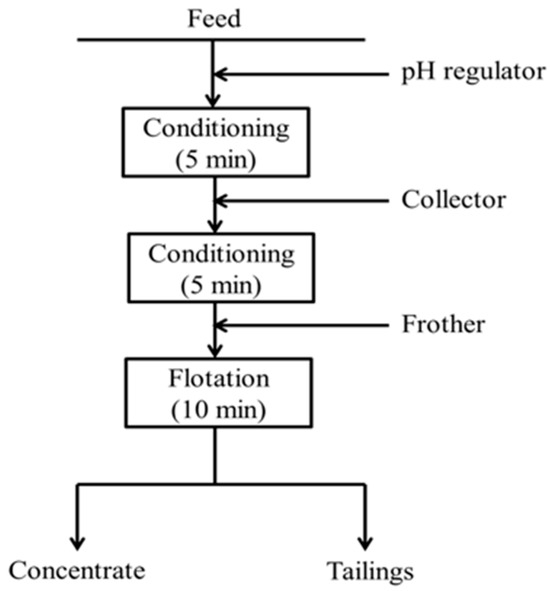

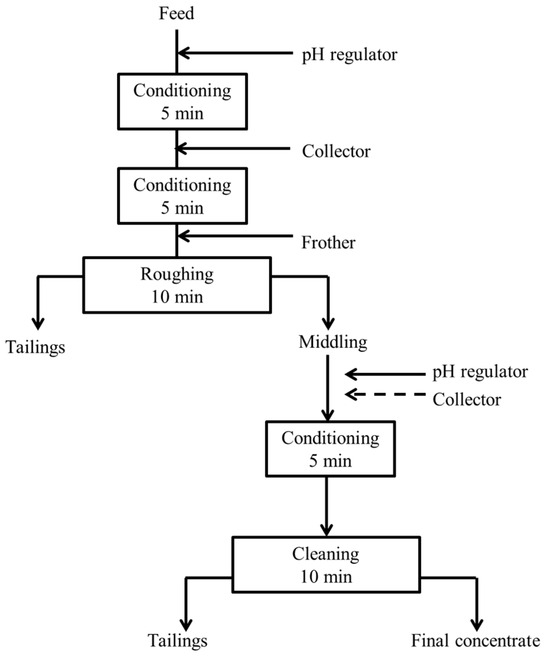

The primary flotation of the copper ore and the gold ore was conducted using a flotation machine (MS P203, ASAHI, Tokyo, Japan) with a cell volume of 250 mL. The flotation speed was set to 1000 rpm. For the copper ore, 5 g of ore and 225 mL of distilled water were added to the cell to maintain a pulp density of 10%. Comparative tests were carried out at pulp density of 5%, 10%, and 20% in the initial stage. The results (Figure S1) showed that the copper recovery did not change much under different pulp densities, while the concentrate grade decreased under higher density. Therefore, a pulp density of 10%, which is generally suitable in laboratory flotation tests to ensure stable operation and comparability of results, was chosen. For the low-grade gold ore, a pulp density of 30% (75 g ore and 175 mL distilled water) was selected based on the same principle, considering stable flotation operation and experimental controllability under laboratory conditions. Calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) was used to adjust the pH of the pulp, which was then conditioned for 5 min. Afterward, a certain amount of collector was added, and a further 5 min of conditioning time was allowed. The frother methyl isobutyl carbinol (MIBC) with a dosage of 100 g/t was then added with agitation for 1 min. Froth collection started and lasted for 10 min. Finally, the obtained concentrate and tailings were dried, weighed, and analyzed for their chemical compositions using MP-AES. The primary flotation process is shown in Figure 4. For the continuous secondary flotation of copper ore, the roughing stage was performed using a flotation machine (Agitare, ASAHI, Tokyo, Japan) with a cell volume of 5 L. A total of 500 g of ore was mixed with 4500 mL of distilled water to maintain a pulp density of 10%. Then, the middling concentrate from the roughing was directly fed to the flotation machine with a cell volume of 1 L (Agitare, ASAHI, Tokyo, Japan) for cleaning. All conditioning operations were the same as those in the primary flotation. The dried concentrate and tailings were analyzed using MP-AES. The process of continuous secondary flotation is presented in Figure 5. Each flotation experiment, except for the gold ore (limited availability), was repeated three times to ensure the reliability of the results. Flotation experiments were conducted using the collector dosage in an industrially common unit of g/t. For a better understanding and comparison, the corresponding concentrations in mol/L are also provided in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Primary flotation process for copper ore and gold ore.

Figure 5.

Continuous secondary flotation process for copper ore.

Table 3.

Conversion of collector dosage units in flotation experiments: from g/t to mol/L.

2.3. Flotation Kinetics

Flotation kinetics is the study of changes in floated minerals over time during the flotation process. The flotation process can be better simulated, and the influence of various factors on flotation can be better described [21]. Many researchers have established flotation kinetic models to explain the flotation process. These models have also been applied in practice to improve the flotation process and optimize the design of flotation plants and equipment [22,23]. The first-order model, Equation (1), which is often used in flotation kinetics studies, was employed in this study to evaluate the flotation rate constants of collectors 2-OA and PAX [24,25,26].

where R is the cumulative copper recovery at time t, k (min−1) is the flotation rate constant, and t (min) is the flotation time.

ln(1 − R) = −kt

2.4. Zeta Potential Test

The adsorption effect and modulation of the interfacial charge of collectors on the mineral surface can be analyzed by comparing the changes in the zeta potential of minerals before and after treatment with collectors. For each test, 0.05 g of chalcopyrite (less than 5 μm) was added to 50 mL of the prepared solutions with or without collectors (1 × 10−3 mol/L) to ensure that the collectors were fully adsorbed on the mineral particle surface. The pulp pH was then adjusted to the expected range (2–12) using HCl or NaOH and stirred for 5 min. The samples collected from the stirred suspension were analyzed using the ELSZ-1000 system (Otsuka Electronics, Osaka, Japan). Each measurement was repeated three times [27].

2.5. FTIR Analysis

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to determine the adsorption of the collector on chalcopyrite by comparing the spectral features before and after treatment. A 2 g portion of chalcopyrite sample (<5 μm) was dispersed in distilled water, and the pulp pH was adjusted to 9 using sodium hydroxide. The collector was then added at a concentration of 1 × 10−3 mol/L, followed by magnetic stirring for 15 min. The suspension was filtered, and the solid residue was washed three times with distilled water. The obtained products were dried at 45 °C for 24 h and subsequently ground manually to prepare the test specimens. FTIR spectra were recorded using a Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS50 spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA) in the wavenumber range of 4000–500 cm−1.

2.6. Adsorption Test

A series of collector solutions with gradient concentrations was prepared, and their absorbances were measured using a UV spectrophotometer (UV-1280, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) to establish a standard calibration curve. Next, 5 g of the chalcopyrite sample was added to 50 mL of distilled water in a beaker. The pulp pH was adjusted to 9 using sodium hydroxide. A specific amount of collector was then added, and the mixture was stirred magnetically for 15 min. Afterward, the pulp was filtered, and the filtrate was centrifuged. The supernatant was measured using a UV spectrophotometer to determine the residual collector concentration, which was then calibrated against the standard curve. Each test was repeated three times. The adsorption rate of the collector was calculated according to Equation (2).

where RA (%) is the adsorption rate of the collector, C0 (mol/L) is the initial collector concentration, and C (mol/L) is the residual collector concentration after reaction.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Copper Ore Flotation

3.1.1. Effect of pH

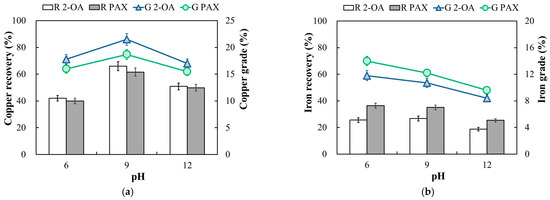

The 2-OA and PAX collectors were used for comparative tests of the flotation performance. The effect of pH on the copper sulfide ore was tested under a pulp density of 10% and a collector dosage of 100 g/t. The flotation results are shown in Figure 4. Here, R 2-OA and R PAX represent the recovery (%) for collectors 2-OA and PAX, respectively, while G 2-OA and G PAX denote the grade (%) of the concentrate. Figure 6a shows that as the pulp pH increased, the flotation environment changed from acidic to alkaline, and the copper recovery of collectors 2-OA and PAX increased. However, the recovery and grade of copper and iron for both collectors, 2-OA and PAX, decreased when the pH increased to 12. This was because, as the pH increased, a hydrophilic iron oxide hydroxyl substance was formed on the mineral surface, hindering the reaction and decreasing the recovery [28,29]. The highest copper recovery was obtained at a pH of 9. Collector 2-OA achieved a copper recovery of 66.0% with a copper grade of 21.5%, whereas the copper recovery of PAX was 61.6% with a lower copper grade of 19.1%. A suitable, highly alkaline environment enhanced the inhibition of gangue minerals and improved the selectivity for copper minerals. As shown in Figure 6b, the iron recovery and grade of collector 2-OA were 26.7% and 10.7%, respectively, which were lower than those of PAX at 35.1% and 12.2%, respectively. This is probably attributed to the fact that collector 2-OA holds an amino group with stronger metallophilicity. The amino group binds more easily to copper under alkaline conditions, especially under strong alkaline conditions [30,31]. Thus, collector 2-OA showed a more favorable separation tendency for copper and iron than PAX during the flotation of the copper sulfide ore. Overall, under the investigated pH conditions, the flotation results indicated that collector 2-OA achieved a higher copper recovery and grade while maintaining lower iron recovery compared with PAX on the copper ores.

Figure 6.

Effect of pH on the recovery and grade of copper (a) and iron (b) in copper ore flotation. R 2-OA and R PAX: recovery (%); G 2-OA and G PAX: grade (%). (Flotation condition: −75 μm, pulp density 10%, pH 6–12, collector 100 g/t, frother 100 g/t).

The overall flotation recovery of the copper ore was relatively low. The monomer liberation degree of different mineral components before and after flotation was analyzed using MLA (MLA650F, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The results showed that the monomer liberation degree of chalcopyrite was approximately 50%, indicating that most of the particles were tightly bound to gangue minerals with a limited exposed surface area. In contrast, pyrite exhibited an 80% liberation degree, making it more readily adsorbed by collectors. Since collectors primarily work on exposed mineral surfaces, the low effective coverage of chalcopyrite led to reduced copper flotation efficiency due to competitive adsorption by gangue minerals. This also resulted in weaker responsiveness to pH changes. Preliminary flotation tests were also conducted at −45, −75, and −160 μm to investigate the effect of grinding conditions, with the results being −75 μm > −45 μm > −160 μm. Due to the high pyrite and quartz contents in this copper ore, fine grinding will produce a large amount of fine sludge that will cover the chalcopyrite surface, reducing the advantage of improved dissociation. Therefore, the flotation performance of −45 μm was not better than that of −75 μm, which was a reasonable grinding size considering the lack of dissociation and the effect of fine sludge.

3.1.2. Effect of Collector Dosage

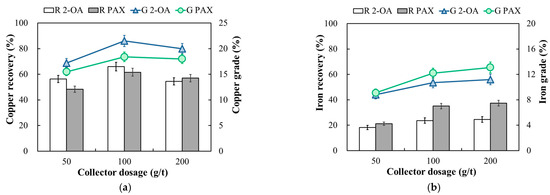

The effect of collector dosage was investigated at a collector dosage of 50–200 g/t at a pulp density of 10% and pH 9. As shown in Figure 7, the copper and iron recovery of collector 2-OA and PAX increased gradually to the highest values with an increase in the collector dosage from 50 to 100 g/t. When the collector dosage was increased to 200 g/t, the copper decreased, but the iron recovery increased. For complex sulfide ores, this phenomenon may be caused by multiple factors. On the one hand, Qiu et al. (2014) [32] noted that in complex sulfide copper ores with high gangue content, copper recovery tends to be saturated when collector dosage reaches 50–60 g/t. Further increases in dosage instead lead to a decline in the concentrate grade [32]. On the other hand, the ore used in this study contained less than 1% chalcopyrite, while pyrite and quartz accounted for approximately 31% and 30%, respectively, indicating a high proportion of gangue minerals. For such highly ganged ores, the surface area of target minerals is limited. Gangue minerals readily adsorb collectors, intensifying competitive adsorption and diminishing collector selectivity [33]. As shown in the flotation results, iron recovery still increased slightly, but copper recovery decreased under relatively high collector dosage. The overall trend of the results showed that collector 2-OA had a higher collecting capacity for copper, resulting in a higher copper recovery. The flotation results presented for the copper ores are comparable to those observed on mixed oxidized-sulfide Cu-Co ores by Tijsseling et al. [6]. Their study compared SIPX (Sodium Isopropyl Xanthate) with the composite collector DF507B, and the copper recovery of DF507B in roughing was increased by about 8% compared to SIPX, showing that highly selective collectors are more favorable for complex ores. In this study, 2-OA improved the copper recovery by about 5%–8% compared with PAX, which is in line with the improvement trend of DF507B, indicating that 2-OA exhibits a stronger tendency for selective copper collection in the flotation of complex sulfide ores under the investigated dosage range.

Figure 7.

Effect of collector dosage on the recovery and grade of copper (a) and iron (b) in copper ore flotation. R 2-OA and R PAX: recovery (%); G 2-OA and G PAX: grade (%). Flotation condition: −75 μm, pulp density 10%, pH 9, collector dosage 50–200 g/t, frother 100 g/t.

3.1.3. Flotation Kinetics Analysis

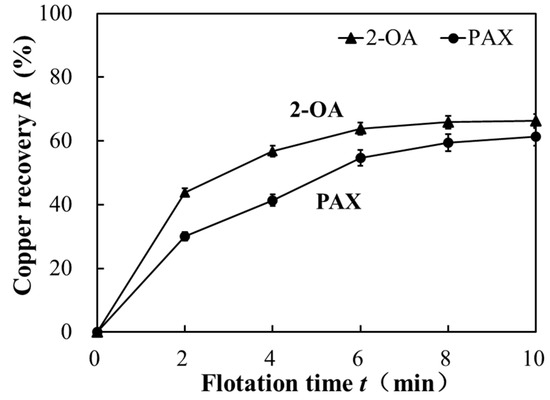

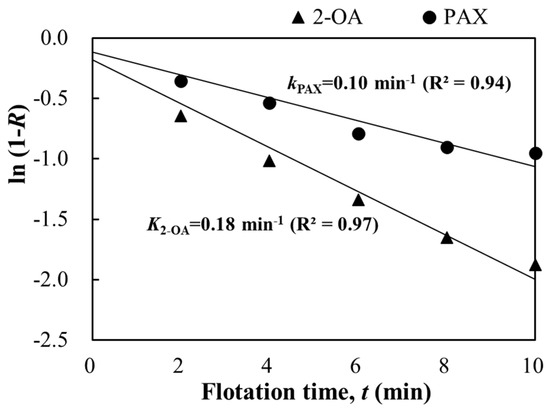

The flotation kinetics tests of the copper sulfide ore were conducted using collectors PAX and 2-OA at the optimum conditions of pH 9 and a collector dosage of 100 g/t obtained from the above conditioning tests. Figure 8 shows that the cumulative copper recovery increased rapidly from 0 to 2 min, and the increase stabilized after 6 min. The copper recovery of both collectors, 2-OA and PAX, almost stopped increasing and reached a maximum of 65% and 62%, respectively. The flotation was nearly completed within 10 min. Moreover, the copper recovery of collector 2-OA consistently surpassed that of PAX over the entire 10-min duration. As shown in Figure 9, the slope representing the flotation rate constant (the fitting error was ≥0.94) was calculated and fitted using Equation (1) based on the cumulative copper recovery obtained from Figure 8. The flotation rate constant of collector 2-OA was 0.18 min−1, whereas that of PAX was only 0.10 min−1. This indicates that collector 2-OA reacted faster than PAX and could significantly improve copper recovery in a short period, which is consistent with the flotation results presented earlier. The flotation efficiency of collector 2-OA was higher under the same conditions [34].

Figure 8.

Comparison of cumulative copper recovery over time for copper ore flotation. Flotation condition: −75 μm, pulp density 10%, pH 9, collector 100 g/t, frother 100 g/t.

Figure 9.

Comparison of flotation rate constants for copper ore flotation. Flotation condition: −75 μm, pulp density 10%, pH 9, collector 100 g/t, frother 100 g/t.

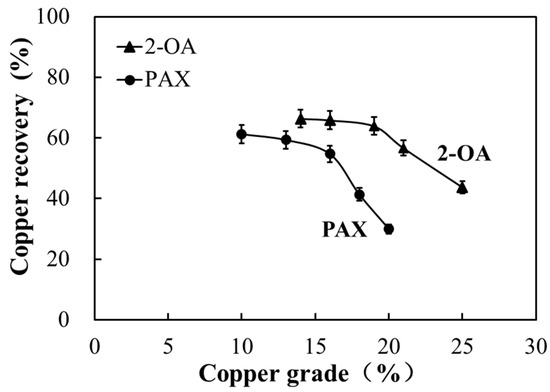

The Halbich curve was employed to characterize the enrichment behavior of copper during flotation based on the relationship between copper grade and recovery at different flotation times. A curve positioned toward the upper right reflects a more favorable upgrading tendency, characterized by higher grades at comparable recovery levels. A significant change indicates more pronounced enrichment behavior [35]. As shown in Figure 10, 2-OA achieved a relatively higher copper grade even at low recovery, demonstrating distinct early enrichment characteristics. In contrast, PAX generally yielded a lower grade than 2-OA at equivalent recovery. Overall, the 2-OA curve was positioned predominantly in the upper-right quadrant, whereas the PAX curve tended toward the lower-left region, indicating a more favorable copper enrichment tendency of 2-OA under the investigated kinetic conditions.

Figure 10.

Comparison of copper enrichment effect between collector 2-OA and PAX in copper ore flotation.

It should be noted that more systematic qualitative and quantitative mineral data are not yet available due to equipment limitations. Therefore, the discussion of the separation and enrichment effect of the novel collector 2-OA and the conventional collector PAX is primarily based on metal recovery, grade, and flotation kinetics. Related aspects will be further investigated in future work as more comprehensive mineralogical information becomes accessible.

3.2. Gold Ore Flotation

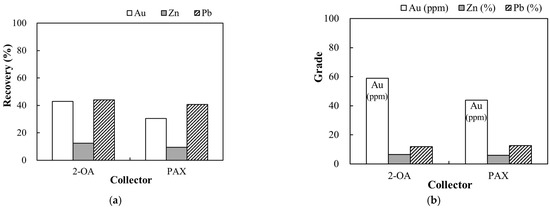

A gold sulfide ore was employed in this study to explore the flotation effect of 2-OA on different types of sulfide ores. The purpose of this test was to obtain the basic flotation properties of the novel collector 2-OA in different mineral backgrounds to serve as a reference for future expansion of the study to more kinds of sulfide ores. Xanthate is widely used in the flotation of gold ores because of its strong collecting capacity [36]. Therefore, PAX was used for comparison in this study. The flotation test was performed with a particle size below 75 μm, pulp density of 30%, pH of 7–8, collector of 100 g/t, and frother of 200 g/t. The results are shown in Figure 11. The recoveries of Au, Zn, and Pb from collector 2-OA reached 43%, 12.4%, and 44%, respectively, and the grades of Au, Zn, and Pb were 59 ppm, 6.4%, and 12.0%, respectively. Compared with the utilization of PAX, the recovery of gold increased by 13%, and the grade increased by 15 ppm. The recovery and grade of Zn increased by 3% and 0.4%, respectively. The improvement in Pb recovery was 4%, likewise, the Pb grade. Mineralogical analysis indicated that gold in the ore was mainly associated with galena and pyrite. Regarding the surface electronic properties, Pb2+ exposed on the galena surface is a soft acid, whereas Zn2+ exposed on the sphalerite surface is a borderline acid. The S and N atoms in the collector 2-OA are soft bases, which coordinate more effectively with the soft acid Pb2+ than with Zn2+ [37]. Therefore, the adsorption on galena may be stronger than on sphalerite. A previous study demonstrated that S or N atoms in collector molecules can chelate Pb atoms on the galena surface, exhibiting a strong affinity for galena at pH levels of 8.0–9.0 [38]. In addition, aryl thiourea collectors containing a benzene ring, amino, and sulfur groups that are similar to the structure of 2-OA have been reported in the separation of sphalerite and galena. It shows that such compounds can form C-S-Pb and C-N-Pb coordination chemical bonds on galena, further enhancing adsorption and flotation performance, while adsorption on sphalerite remains mainly physisorption [39]. The newly developed collector 2-OA used in this study possesses structural features that are likely to facilitate multi-point coordination on galena. This coordination promotes galena flotation and enhances gold recovery. These factors also explain the more pronounced variation in the recovery and grade of Pb observed with 2-OA compared to Zn in flotation tests.

Figure 11.

Recovery (a) and grade (b) of gold, zinc, and lead in gold ore flotation. Flotation condition: −75 μm, pulp density 30%, pH 7–8, collector 100 g/t, frother 200 g/t.

3.3. Continuous Secondary Flotation

Collector 2-OA showed a better flotation effect and superior collecting ability for gold than PAX during the one-stage flotation of copper and gold ores. However, the flotation results showed that the enrichment effect of copper from 2-OA was comparable to that of PAX in the flotation of copper sulfide ores. Therefore, to further demonstrate the copper-collecting ability of 2-OA, continuous secondary flotation tests were carried out on the copper sulfide ore.

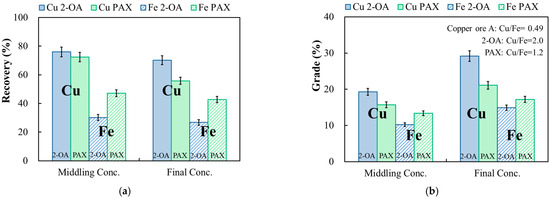

3.3.1. Addition of Collector Only in the Roughing Stage (Condition ①)

The roughing of condition ① was performed at pH 9, 100 g/t of collector, and 100 g/t of frother. The results are shown in Figure 12. The copper recovery of collector 2-OA in roughing was 76.3%, while the copper grade in the concentrate (middling) was 19.3%. On the other hand, utilizing PAX yielded a copper recovery of 72.4% and a copper grade of 15.7% in the concentrate (middling). The concentrates from roughing were directly fed into the cleaning stage. The pH was increased to 10, and 25 g/t of frother was added without the addition of a collector. The final copper recovery of collector 2-OA was 70.2%. By employing a continuous secondary flotation process, the copper grade was successfully enriched to 1.5 times higher than that of roughing, from 19.3% to 29.2%. When comparing the performance of PAX to collector 2-OA, a lower copper recovery of 55.8% and a copper grade of 21.1% were obtained. Additionally, the separation effect of copper and iron minerals for collector 2-OA was superior to that of PAX. The final iron recovery obtained from collector 2-OA was 26.8%, which was lower than that of PAX (42.8%). The metal grade results (Figure 12b) showed that the final copper-iron grade ratio of 2-OA increased from an initial ratio of 0.49 to 2.0, while the ratio of PAX only increased to 1.2. The significant increase in the copper grade of 2-OA, coupled with a substantial difference in the iron grade, clearly demonstrates an effective copper and iron separation.

Figure 12.

Effect of the addition of collector only in the roughing stage on the recovery (a) and grade (b) of copper and iron in the continuous secondary flotation of copper ore. Cu 2-OA and Cu PAX: copper recovery (%) or copper grade (%) of 2-OA and PAX; Fe 2-OA and Fe PAX: iron recovery (%) or iron grade (%) of 2-OA and PAX. Condition ①: −75 μm, pulp density 10%; roughing: pH 9, collector 100 g/t, frother 100 g/t; cleaning: pH 10, collector 0 g/t, frother 25 g/t.

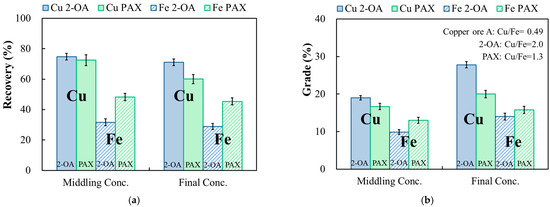

3.3.2. Addition of Collector in Both Roughing and Cleaning Stages (Condition ②)

The flotation results under condition ② are shown in Figure 13. The roughing conditions were the same as in condition ①. During the cleaning stage, except for raising the pH to 10 and adding 25 g/t of frother, another 25 g/t of collector was added to investigate the flotation effect of collector dosage during cleaning. When collector 2-OA was used, the copper recovery was 74.8%, with a copper grade of 19.0% during roughing. Collector PAX yielded a lower copper recovery of 72.5% and a copper grade of 16.7% in the roughing stage. After an additional 25 g/t of collector, the copper recovery of the final concentrate when utilizing collector 2-OA was 71.1%, and the copper grade was 27.8%. On the other hand, the copper recovery and copper grade of the final concentrate when using the collector PAX were 60.1% and 20.0%, respectively. The order of iron recovery remained the same as that in the above tests, with 2-OA at 28.9% lower than that of PAX at 45.4%. As shown in Figure 13b, the copper–iron ratio also showed similar results to condition ①. The favorable copper–iron ratio of 2-OA compared to PAX showed a superior collecting ability of copper than iron, as in previous tests. Overall, the novel collector 2-OA performed better than PAX in continuous secondary flotation.

Figure 13.

Effect of addition of the collector in both the roughing and cleaning stages on the recovery (a) and grade (b) of copper and iron in continuous secondary flotation of copper ore. Cu 2-OA and Cu PAX: copper recovery (%) or copper grade (%) of 2-OA and PAX; Fe 2-OA and Fe PAX: iron recovery (%) or iron grade (%) of 2-OA and PAX. Condition ②: −75 μm, pulp density 10%; roughing: pH 9, collector 100 g/t, frother 100 g/t; cleaning: pH 10, collector 25 g/t, frother 25 g/t.

Comparing the flotation results of the two conditions, with the addition of an extra 25 g/t collector for cleaning, the copper recovery of 2-OA increased by only 0.9%, while that of PAX increased by only 4.3%, accompanied by a decrease in the final copper grade. Moreover, the iron recovery increased with the addition of the collector. Collector 2-OA showed a 2.1% increase in iron recovery, PAX showed a 2.6% increase, and the separation effect of copper and iron slightly worsened. This shows that collector 2-OA exhibits good sustainability and fast reactivity during flotation, which is consistent with the flotation kinetics results. Therefore, the dosage of the collector during cleaning can be reduced or even eliminated. Meanwhile, the final copper concentrate grade of the secondary flotation can be increased to 1.5 times that of roughing compared to the primary flotation, showing a better enrichment effect of copper. The maximum difference in the final copper recovery between 2-OA and PAX was around 15%. This obvious difference proves that collector 2-OA has a strong ability to collect copper, and the collector’s effect can be fully exerted to improve the quality of concentrates using secondary flotation. The results are also in good agreement with the data reported by Xia et al. [40]. They achieved a copper recovery of around 70% when floating high sulfur low copper ores using the SBX (Sodium Butyl Xanthate) and ADD (Ammonium Dibutyl Dithiophosphate) combination at a total dosage of 210 g/t and their self-developed collector combination of ML-8 and Z-200, with a slight increase in copper grade for the self-developed collector combination. Both their ore samples and the copper ore in our study were characterized by poor dissociation, large number of gangues, and pyrite competition, so the flotation difficulty was similar. The copper recovery in this study using 2-OA and PAX for two-stage flotation was also about 70%, which is highly consistent with the literature reports. This demonstrates the reliability of the established benchmark system, which clearly shows the performance enhancement of 2-OA.

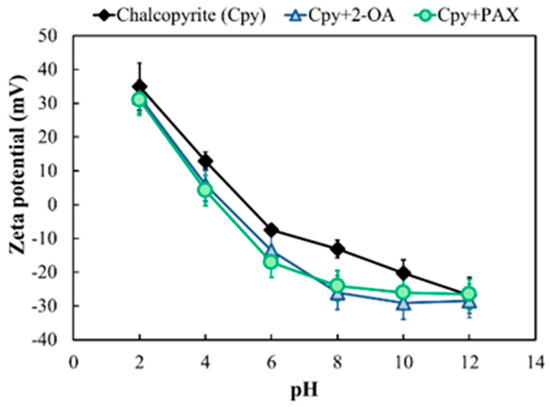

3.4. Zeta Potential Results

Zeta potential measurements were performed on chalcopyrite before and after interaction with 2-OA and PAX at a collector concentration of 1 × 10−4 mol/L. The zeta potential results revealed different surface interaction mechanisms between chalcopyrite and the two collectors, as shown in Figure 14. Without collector addition, the chalcopyrite surface showed a positive charge at pH < 5 and a negative charge at pH > 5 due to surface S2− species, with an isoelectric point around pH 5. The gradual decrease in zeta potential with increasing pH was attributed to enhanced OH− adsorption on the surface. PAX, as a typical anionic collector, dissociates into ROCSS− anions in aqueous solution. Its interaction with chalcopyrite surfaces is primarily electrostatic adsorption supplemented by weak chemical coordination. After the addition of PAX, ROCSS− binds to positively charged metal sites on the chalcopyrite surface through electrostatic attraction, and the sulfur atom forms coordination bonds with surface metal ions. Finally, the adsorption of anions directly contributes to a negative charge, shifting the zeta potential toward negative values. However, constrained by the coordination capacity of a single site, the degree of the negative shift is relatively small.

Figure 14.

Zeta potential of chalcopyrite before and after treatment with 2-OA/PAX.

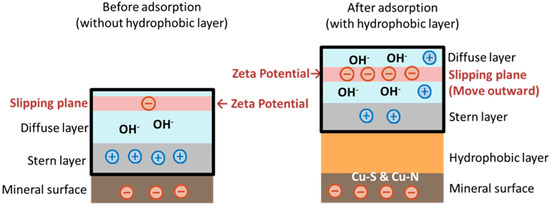

In contrast, at pH < 7, 2-OA became positively charged due to the protonation of its amino group into NH3+, resulting in minimal changes to the zeta potential of chalcopyrite in acidic conditions. When pH > 8, a negative shift in the zeta potential of chalcopyrite induced by 2-OA was observed. This may be due to the reconstruction of the solid–liquid interface by the adsorption layer formed by its long carbon chain on the mineral surface. There is a study that the adsorption of nonionic surfactants significantly affects the zeta potential by altering the position of the slip plane [41]. The 2-OA molecule possessed a long alkyl chain, making it likely to form a dense hydrophobic adsorption layer on the chalcopyrite surface. This dense hydrophobic layer pushed the solution’s slip plane outward. Within the electric double layer structure, further from the mineral surface, the closer the potential approached the region where anions (e.g., OH− under alkaline conditions) accumulated in the diffusion layer, typically exhibiting a more negative potential [42]. Meanwhile, the hydrophobic layer repelled hydrated cations, weakening positive charge compensation. The combined effect of these two mechanisms reduces the potential at the slip plane, ultimately showing as a negative shift in the zeta potential, as shown in Figure 15. Furthermore, although 2-OA is a nonionic collector, both its -S and -NH2 groups can coordinate with surface copper atoms, resulting in strong chemical adsorption on chalcopyrite surfaces [43]. This strong double-site chemical adsorption involved electron transfer from the collector molecule to the mineral surface, sufficiently altering the surface charge state of chalcopyrite to cause a negative shift in the zeta potential. The chemical adsorption enabled collector 2-OA to effectively cover the mineral surface, maintaining high hydrophobicity. This facilitated easier bubble attachment to mineral particles, achieving high recovery and better selectivity. To further validate whether 2-OA was adsorbed on the chalcopyrite surface through double-site chemical adsorption, FTIR analysis was employed to verify the interactions between the collector and the chalcopyrite surface.

Figure 15.

Zeta potential changes after treatment with 2-OA (alkaline condition).

3.5. FTIR Analysis Results

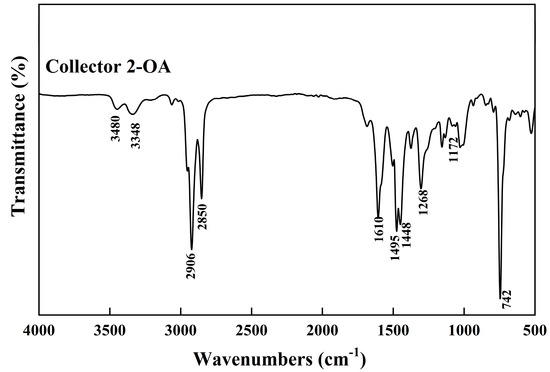

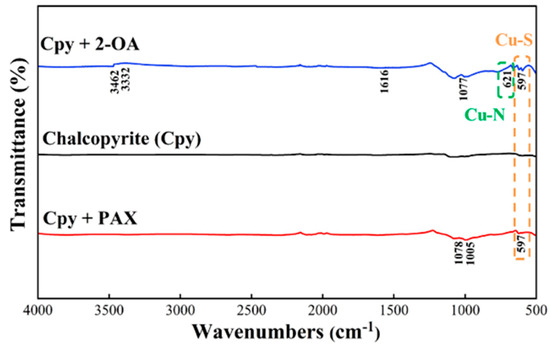

To investigate the effect of the interaction principle between the two collectors and chalcopyrite on the flotation performance, FTIR analysis was conducted on chalcopyrite before and after treatment with 2-OA and PAX, respectively. In the infrared spectrum of 2-OA (Figure 16), 3480 cm−1 and 3348 cm−1 corresponded to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of the amino group (-NH2), respectively, while 2906 cm−1 and 2850 cm−1 were related to C-H stretching vibrations. The peak at 1610 cm−1 represented N-H bending vibrations. Peaks near 1500 cm−1 indicated skeletal vibrations of the benzene ring, and 1268 cm−1 corresponded to C-N stretching vibrations. The peaks observed at 1172 cm−1 and 742 cm−1 were attributed to the C-S (Ar–S–R skeleton) vibration. As shown in Figure 17, after chalcopyrite treatment with 2-OA, the characteristic peaks of the stretching vibration of the amino group shifted by approximately 16–18 cm−1 and the intensity of N–H bending (1610 cm−1) decreased. A slight peak appeared near 621 cm−1, which suggests that the amino group may coordinate with copper in chalcopyrite, leading to the formation of a Cu-N bond. Meanwhile, the C-S stretching vibration peak was weakened, and a new peak at 597 cm−1 was formed, indicating the combination of the thiol group in 2-OA [44,45]. This further demonstrated the significant interaction between 2-OA and the mineral surface. Furthermore, the C-H stretching peak in the 2-OA molecule also exhibited a slight shift after interaction, and the intensity of the peaks decreased, indicating that the long alkyl chain also participated in the adsorption and provided hydrophobicity, which contributed to enhanced flotation performance. This also confirmed the double-site adsorption mentioned in the zeta potential test.

Figure 16.

IR spectra of collector 2-OA.

Figure 17.

IR spectra of chalcopyrite before and after treatment with 2-OA/PAX.

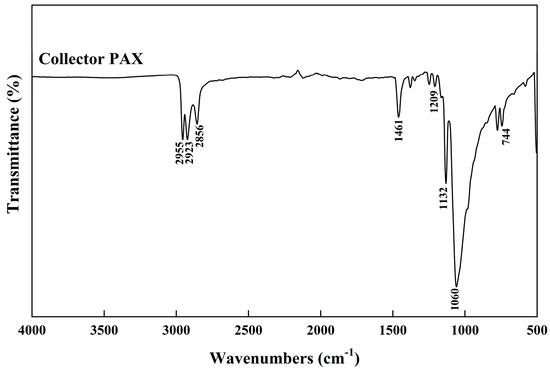

In contrast, the interaction process of PAX was simpler. PAX mainly exhibited characteristic peaks at 1209 cm−1 (C-O-C asymmetric vibration), 1132 cm−1 (C=S stretching vibration), 1060 cm−1 (C-O-C symmetric vibration), and 744 cm−1 (C-S stretching vibration), as shown in Figure 18 [46]. After interaction with chalcopyrite, the C-S stretching vibration was weakened and a new peak appeared at the same position as 2-OA (597 cm−1), indicating the formation of a Cu-S bond. The C-O-C group shifted and the intensity decreased, primarily due to its contribution to hydrophobicity, affecting the flotation effect rather than directly participating in chemical reactions [47,48]. Studies have shown that under room temperature and neutral or weakly alkaline conditions, xanthate mainly forms Cu–S–C(=S)–OR bonds (single sulfur coordination) on chalcopyrite surfaces [49,50]. This indicates that only C-S coordinated with copper in chalcopyrite during the adsorption of PAX on chalcopyrite. Overall, there were formations of two bonds, Cu-N and Cu-S, observed from 2-OA. But only one bond, Cu-S, formed from PAX, after interaction. Therefore, 2-OA exhibited stronger binding to the chalcopyrite surface, potentially creating a more stable adsorption layer that facilitated maintaining higher floatability during flotation.

Figure 18.

IR spectra of collector PAX.

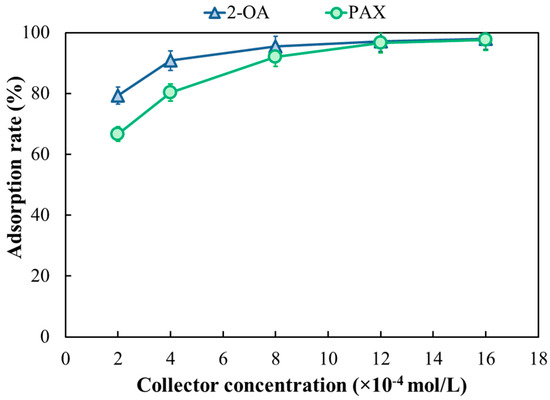

3.6. Adsorption Results

The effect of collector concentration on the adsorption rate was conducted at pH 9. As shown in Figure 19, both collectors 2-OA and PAX exhibited a similar adsorption trend with concentration, with a rapid initial increase followed by plateauing. However, 2-OA demonstrated superior overall adsorption capacity. At the same concentration, the adsorption rate of PAX was consistently lower than that of 2-OA, and 2-OA reached saturation adsorption earlier than PAX. At a concentration of merely 2 × 10−4 mol/L, 2-OA achieved an adsorption rate exceeding 80%, higher than the 67% achieved by PAX at the same concentration. When the collector concentration increased to 8 × 10−4 mol/L, the adsorption rate of 2-OA tended to level off. However, PAX approached a steady state after the concentration exceeded 12 × 10−4 mol/L. At a concentration of 16 × 10−4 mol/L, the adsorption rates of both 2-OA and PAX reached over 97%, approaching saturation. Adsorption rate is the proportion of collector molecules that can stably exist on the mineral surface. A higher adsorption rate for collector 2-OA indicated that 2-OA more fully covered the mineral surface, resulting in a broader hydrophobic region on the mineral surface. This significantly enhanced the adhesion of collectors to bubbles, thus improving the floatability [51]. For collector 2-OA, the combination of S–Cu, N–Cu bonds and ordered long-chain hydrophobic chains not only ensures high coverage but also enhances adsorption stability on copper minerals, explaining its high copper recovery and better selectivity in chalcopyrite flotation.

Figure 19.

Absorption rate of 2-OA and PAX on chalcopyrite.

4. Conclusions

With the decline in the grade of sulfide ores and the increasing complexity of ore compositions, conventional collectors such as xanthate often show insufficient selectivity and limited adsorption efficiency when treating lightly oxidized or complex sulfide ores. Therefore, the development of novel collectors with stronger coordination capacity and high selectivity has become a hot topic. In this study, the flotation performance of the novel collector 2-OA was evaluated on sulfide ores with different compositions, and a preliminary discussion on the possible factors contributing to its performance enhancement was conducted based on kinetic and interfacial adsorption results. The effects of various flotation parameters, such as pulp pH, collector dosage, and flotation speed of 2-OA compared with those of the conventional collector PAX, were tested on a copper sulfide ore and a gold sulfide ore. The results indicated that 2-OA showed relatively higher copper recovery than PAX in the copper ore flotation under the conditions set in this study. For the gold ore, 2-OA exhibited a higher gold recovery than PAX based on the measured results. Even in secondary flotation, 2-OA can significantly enhance the copper grade, improving the quality of the copper concentrate. Collector 2-OA was more efficient than PAX in terms of faster reaction speed and lower dosage under the same conditions.

Surface chemical analysis further supported the above conclusions. The zeta potential tests showed that 2-OA rendered the chalcopyrite surface more hydrophobic through hydrophobic layer reconstruction and strong coordination, thus the flotation effect was superior to that of PAX. FTIR analysis revealed that 2-OA formed Cu-S and Cu-N bonds on the chalcopyrite surface, promoting chalcopyrite flotation more effectively than the single-bond adsorption of PAX. Adsorption experiments demonstrated that 2-OA exhibited higher adsorption rates than PAX, with more pronounced enrichment effects on chalcopyrite. These findings are consistent with the flotation performance results, further demonstrating that 2-OA exhibits a better flotation effect than PAX in sulfide ore flotation.

These findings provide an experimental supplement to the existing understanding of the flotation behavior of aniline-based collectors. They not only propose a new solution for the separation of complex sulfide ores, but also offer a reference for the optimization of the collector structure and the design of new flotation reagents. Nevertheless, there are still some limitations in this study in terms of the coverage of ore types and the depth of interface characterization. In future study, more types of sulfide ores and collectors and finer characterization techniques can be combined to further compare the flotation properties and clarify the adsorption mechanisms of 2-OA on sulfide minerals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min16010045/s1, Table S1: Apparent distribution of metals between flotation products of copper ore under different pH; Table S2: Apparent distribution of metals between flotation products of copper ore under different collector dosages; Table S3: Apparent metal distribution between final flotation products of copper ore obtained from two-stage flotation tests; Table S4: Apparent distribution of metals between flotation products of gold ore; Figure S1: Effect of pulp density on the recovery and grade of copper (a) and iron (b) in copper ore flotation; Figure S2: Effect of particle size on the recovery and grade of copper (a) and iron (b) in copper ore flotation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; Formal analysis, J.Z.; Investigation, J.Z.; Methodology, K.H., M.Y. and A.S.; Project administration, S.H. and A.S.; Resources, S.H. and A.S.; Supervision, A.S.; Validation, J.Z. and S.H.; Visualization, J.Z.; Writing—original draft, J.Z.; Writing—review and editing, L.L.G. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the “JSPS KAKENHI” (grant number 19H04309).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Seunggwan Hong was employed by the company JX Advanced Metals Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Vaughan, D.J. Sulfide mineralogy and geochemistry: Introduction and overview. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2006, 61, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Feng, Q.; Wen, S.; Xian, Y.; Liu, J.; Liang, G. Flotation separation of chalcopyrite from molybdenite with sodium thioglycolate: Mechanistic insights from experiments and MD simulations. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 342, 126958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. The interaction of flotation reagents with metal ions in mineral surfaces: A perspective from coordination chemistry. Miner. Eng. 2021, 171, 107067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Acharjee, A.; Mandal, U.; Saha, B. Froth flotation process and its application. Vietnam J. Chem. 2021, 59, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulatovic, S.M. Handbook of Flotation Reagents: Chemistry, Theory and Practice—Volume 1: Flotation of Sulfide Ores, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 5–39. ISBN 9780080471372. [Google Scholar]

- Tijsseling, L.T.; Dehaine, Q.; Rollinson, G.K.; Glass, H.J. Flotation of mixed oxide sulphide copper-cobalt minerals using xanthate, dithiophosphate, thiocarbamate and blended collectors. Miner. Eng. 2019, 138, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Huang, K.; Jia, Y.; Wang, S.; Cao, Z.; Zhong, H. Investigating the selectivity of a xanthate derivative for the flotation separation of chalcopyrite from pyrite. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 205, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, B.; Finch, J. Wills’ Mineral Processing Technology, 8th ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 265–380. ISBN 9780080970530. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Cao, Z.; Luo, X. Present situation and prospect of beneficiation technology of copper oxide ore. Met. Mine 2016, 45, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, T.D.S.; Hsia, T.; Ritchie, C.; Thang, S.H. Flotation efficiency and surface adsorption mechanism on chalcopyrite and pyrite by a novel cardanol derivative 3-pentadecylphenyl 4-(3,3-diethylthiouredo-4-oxobutanoate). Miner. Eng. 2024, 207, 108566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopéz, R.; Jordão, H.; Hartmann, R.; Ämmälä, A.; Carvalho, M.T. Study of butyl-amine nanocrystal cellulose in the flotation of complex sulphide ores. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 579, 123655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreider, E.M.; Kontorovich, V.E.; Galanov, M.E.; Trachik, T.L.; Lagutina, L.V. Flotation properties of selected monocyclic aromatic compounds. Koks. Khim. 1981, 4, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Duan, H.; Fang, P.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, X. Study on quantitative structure-biodegradability relationships of amine collectors by GFA-ANN method. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Godirilwe, L.L.; Haga, K.; Yamada, M.; Shibayama, A. Flotation behavior and surface analytical study of synthesized (octylthio) aniline and bis (octylthio) benzene as novel collectors on sulfide minerals. Miner. Eng. 2023, 204, 108422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooren, J.; Binnemans, K.; Björkmalm, J.; Breemersch, K.; Dams, Y.; Folens, K.; Kinnunen, P. Near-zero-waste processing of low-grade, complex primary ores and secondary raw materials in Europe: Technology development trends. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, M.; Drielsma, J.; Humphreys, D.; Storm, P.; Weihed, P. Why current assessments of ‘future efforts’ are no basis for establishing policies on material use—A response to research on ore grades. Miner. Econ. 2019, 32, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northey, S.; Mohr, S.; Mudd, G.; Weng, Z.; Giurco, D. Modelling future copper ore grade decline based on a detailed assessment of copper resources and mining. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 83, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkuna, R.; Ijoma, G.N.; Matambo, T.S.; Chimwani, N. Accessing metals from low-grade ores and the environmental impact considerations: A review of the perspectives of conventional versus bioleaching strategies. Minerals 2022, 12, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Selective extraction performance of Ni, Cu, Co, and Mn adopted by a coupled leaching of low-grade Ni-sulfide ore and polymetallic Mn-oxide ore in sulphuric acid solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2022, 168, 110814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watling, H.R. Review of biohydrometallurgical metals extraction from polymetallic mineral resources. Minerals 2015, 5, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmann, R., Jr. Flotation Kinetics. Methods for steady-state study of flotation problems. J. Phys. Chem. 1942, 46, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, E.; Kelebek, S. Flotation kinetics of a pyritic gold ore. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2011, 98, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humeres, E.; Debacher, N.A. Kinetics and mechanism of coal flotation. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2002, 280, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. Role of surface roughness in the wettability, surface energy and flotation kinetics of calcite. Powder Technol. 2020, 371, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Dehghani, F.; Rezai, B.; Aslani, M.R. Influence of the roughness and shape of quartz particles on their flotation kinetics. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2012, 19, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, M.; Chander, S. First-order flotation kinetics models and methods for estimation of the true distribution of flotation rate constants. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 58, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Xiao, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z. Investigation on the flotation behavior and adsorption mechanism of 3-hexyl-4-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole-5-thione to chalcopyrite. Miner. Eng. 2016, 89, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellón, C.I.; Toro, N.; Gálvez, E.; Robles, P.; Leiva, W.H.; Jeldres, R.I. Froth flotation of chalcopyrite/pyrite ore: A critical review. Materials 2022, 15, 6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Feng, Q.; Lu, Y. The effect of lizardite surface characteristics on pyrite flotation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 259, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, S.; Pawar, G.G.; Kumar, S.V.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, D. Selected copper-based reactions for C−N, C−O, C−S, and C−C bond formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16136–16179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Xie, S.; Xue, P.; Zhang, X.; Dong, J.; Jiang, Y. Efficient and economical access to substituted benzothiazoles: Copper-catalyzed coupling of 2-Haloanilides with metal sulfides and subsequent condensation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4222–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Yan, H.; Ai, G.; Qiu, X. Test study of improving copper sorting index by flash flotation. Nonferr. Met. Sci. Eng. 2014, 5, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sun, W. Influence of BP-series collector on flotation performance of molybdenum oxide and gangue minerals. Min. Metall. Eng. 2013, 33, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Godirilwe, L.L.; Haga, K.; Yamada, M.; Shibayama, A. Evaluation of flotation performance using a novel collector 2-(octylthio) aniline for copper sulfide ore under various flotation conditions. In Proceedings of the XXXI International Mineral Processing Congress (IMPC 2024), Washington, DC, USA, 29 September–3 October 2024; pp. 3319–3325. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Sajjady, S.A.; Gholami, H.; Amini, S.; Özkan, S.G. An improvement on selective separation by applying ultrasound to rougher and re-cleaner stages of copper flotation. Minerals 2020, 10, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, K. Research status and progress of the flotation technology for gold sulfide ore. Ind. Miner. Process. 2022, 51, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G. Hard and soft acids and bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3533–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Cheng, C.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, G. The flotation separation of galena from pyrite with 2-dialkylamino-s-triazine-4-thiol-6 (1H)-thione sodium at pH∼ 8.0: Emphasize on adsorption mechanism. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 411, 125722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Sun, W.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, R.; Cao, J. Different aryl thiourea compounds as flotation collectors in a lead–zinc sulfide mixed system. Minerals 2023, 13, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Xie, X.; Wang, C.; He, D.; Tong, X.; Zhao, C.; Ping, F. Research on the flotation of high-sulfur and low-Copper ore based on mineralogical characteristics. Minerals 2025, 15, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostolska, I.; Wiśniewska, M. Application of the zeta potential measurements to explanation of colloidal Cr2O3 stability mechanism in the presence of the ionic polyamino acids. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2014, 292, 2453–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahame, D.C. The electrical double layer and the theory of electrocapillarity. Chem. Rev. 1947, 41, 441–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernack, E.; Costa, D.; Tingaut, P.; Marcus, P. DFT studies of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole and 2-mercaptobenzimidazole as corrosion inhibitors for copper. Corros. Sci. 2020, 174, 108840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.G.; Tan, J.; Hu, F. Flotation separation of pyrite from chalcopyrite by tetrazinan-thione collectors. J. Cent. South. Univ. 2023, 30, 2587–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.; Brandão, P.; Peres, A. The infrared spectra of amine collectors used in the flotation of iron ores. Miner. Eng. 2005, 18, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Sun, W.; Chen, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C. The effects of hydroxyl on selective separation of chalcopyrite from pyrite: A mechanism study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 608, 154963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Zhang, J. A study of temperature effect on the xanthate’s performance during chalcopyrite flotation. Minerals 2020, 10, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Liu, J.; Han, Y.; Jiang, K.; Zhao, W. Effects of xanthate on flotation kinetics of chalcopyrite and talc. Minerals 2018, 8, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Cao, Y.; Sun, C. FTIR studies of xanthate adsorption on chalcopyrite, pentlandite and pyrite surfaces. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1048, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, R.; Ravanasa, E.; Mirzapour, Y. Exploring mechanism of xanthate adsorption on chalcopyrite surface: An atomic force microscopy study. J. Min. Environ. 2018, 9, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Seo, J.; Kim, S.B.; Kim, W. Flotation behavior of malachite using hydrophobic talc nanoparticles as collectors. Minerals 2020, 10, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.