Abstract

Precise segmentation of flotation froths is a critical bottleneck to achieving intelligent perception and optimal control of process operations. Traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are inherently limited by local receptive fields, making it challenging to accurately segment adhesive and multi-scale froths. To address this fundamental issue, this paper proposes a deep segmentation network with integrated global context awareness, termed GC-FSegNet, which establishes a new paradigm capable of jointly modeling macro-level structures and micro-level details. The proposed GC-FSegNet innovatively integrates the Global Context Network (GCNet) module into both the encoder and decoder of a Nested U-Net architecture. The GCNet captures long-range dependencies between froths, enabling macro-level modeling of clustered foam structures, while the Nested U-Net preserves high-resolution boundary details. Through their synergistic interaction, the model achieves simultaneous and efficient representation of both global contours and local details of froth images. Furthermore, the Mish activation function is employed to enhance the learning of weak boundary features, and a combined Dice and Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss function is designed to optimize boundary segmentation accuracy. Experimental results on a self-constructed copper–lead flotation froth dataset demonstrate that GC-FSegNet achieves an mDice of 0.9443, mIoU of 0.8945, mRecall of 0.9866, and mPrecision of 0.9705, significantly outperforming mainstream models such as U-Net and DeepLabV3+. This study not only provides a reliable technical solution for high-adhesion froth segmentation but, more importantly, introduces a promising “global–local collaborative modeling” framework that can be extended to a wide range of complex industrial image segmentation scenarios.

1. Introduction

Flotation is a core separation technique in mineral processing, where bubbles selectively adsorb target mineral particles to achieve resource enrichment. The efficiency of this process directly governs both the recovery rate of valuable minerals and the economic benefits of mining enterprises.

Consequently, the visual characteristics of froth—specifically Bubble Size Distribution (BSD), mobility, and surface texture—have long been recognized as critical indicators of flotation performance [1,2,3]. Experienced operators rely on these visual cues to adjust air flow rates and reagent dosages. In recent years, automated machine vision systems have been increasingly applied to objectify this process. For instance, studies have demonstrated that monitoring variations in bubble size and coalescence rates can effectively predict mineralization efficiency and froth stability [4,5,6]. Furthermore, real-time analysis of froth velocity and color features has been utilized to optimize control strategies for concentrate grade improvement [7]. However, the reliability of these downstream applications fundamentally depends on the precise segmentation of individual bubbles from complex froth images, which remains a challenging task due to the adhesive and multi-scale nature of the froths.

With the rapid development of deep learning, image segmentation methods based on fully convolutional networks (FCNs) have gradually replaced traditional approaches, emerging as the mainstream due to their end-to-end feature learning capability [8,9,10].

Long et al. [11] first introduced the FCN architecture, replacing fully connected layers with convolutional layers to enable pixel-level image segmentation, thus laying the foundation for the application of deep learning in segmentation tasks. Subsequently, various models such as SegNet, U-Net, and DeepLab have been proposed and continuously optimized, achieving breakthroughs in fields such as medical imaging and industrial inspection [12].

In the context of flotation froth segmentation, numerous studies have addressed domain-specific challenges. For instance, Zhang et al. [13] proposed an improved U-Net architecture with optimized skip connection fusion strategies to mitigate over-segmentation and under-segmentation issues in froth segmentation and to enhance computational efficiency. Tang et al. [14] developed an I-Attention U-Net for zinc flotation froth segmentation, introducing channel attention mechanisms to strengthen the learning of salient features while simplifying network complexity for on-site deployment. Ghareh Chobogh et al. [15] employed Mask R-CNN to achieve instance-level segmentation of froth images, enabling accurate localization and classification of individual froths for size distribution analysis. Du et al. [16] designed the IG-EMA-U2Net algorithm based on the U2Net architecture, incorporating integrated gradient optimization and exponential moving average strategies to reduce information loss and further improve segmentation accuracy.

Despite these remarkable advances, the unique complexity of flotation froth imagery continues to pose several unresolved challenges that constrain segmentation accuracy [17]:

- Scale variance and blurred boundaries. Due to variations in slurry flow, lighting reflections, and particle adhesion on froth films, froth edges often exhibit weak gradient transitions and lack clear contours. Consequently, conventional CNNs struggle to accurately delineate these boundaries. Furthermore, the wide range of froth diameters—from a few millimeters to over ten centimeters—makes it difficult for local-feature-based models to handle multi-scale segmentation tasks effectively. For example, although Ghareh Chobogh et al. enhanced small-froth recognition in Mask R-CNN by integrating SE modules, their method still achieved only 82% accuracy in boundary segmentation of aggregated froths due to the inherent limitations of attention mechanisms in modeling adhesive froth clusters.

- Loss function adaptability. Single loss functions are often sensitive to class imbalance between froth (foreground) and slurry (background) regions. For instance, although Dice loss effectively measures region overlap, it lacks the ability to optimize boundary-level precision, leading to suboptimal segmentation of froth edges [18].

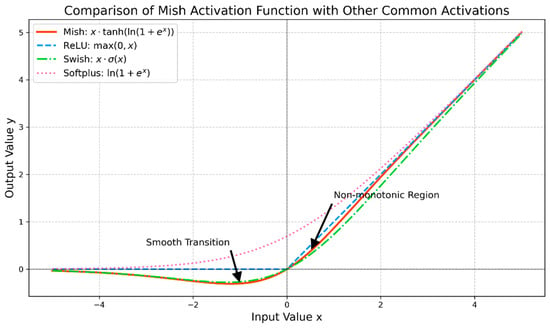

- Limitations of activation functions. Common activation functions, such as ReLU, exhibit drawbacks including dead neurons and inadequate gradient flow in negative domains, thereby hindering the extraction of weak boundary features in froth segmentation.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this study proposes a globally context-aware GC-FSegNet architecture. Its core design principles and key components are as follows:

- Introducing a global context modeling attention mechanism module by integrating the GCNet module into the encoder and decoder of NestedUNet. This captures long-range dependencies between bubbles through global attention pooling, enhancing the modeling capability of overall bubble structures and effectively resolving misclassification of adhered bubbles.

- Designing a combined loss function that integrates Dice loss and BCE loss to form a boundary-aware loss function. This simultaneously optimizes segmentation integrity and pixel classification accuracy, with a focus on improving the segmentation precision of bubble boundaries.

- The Mish activation function is introduced to mitigate gradient vanishing, enhancing the network’s learning capability for weak boundary features. A specialized optimization strategy for flotation is employed, alongside adaptive data augmentation techniques such as random rotation, brightness adjustment, and model regularization methods, to improve the model’s robustness against variations in flotation conditions.

- We finally conducted comparative experiments on our self-built copper-lead ore flotation foam dataset against advanced segmentation algorithms, including U-Net, DeepLabV3+, and AttentionU-Net. Through quantitative metrics and qualitative visualization analysis, we validated the effectiveness and industrial application value of GC-FSegNet.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. U-Net Series Architectures for Pixel-Level Image Segmentation

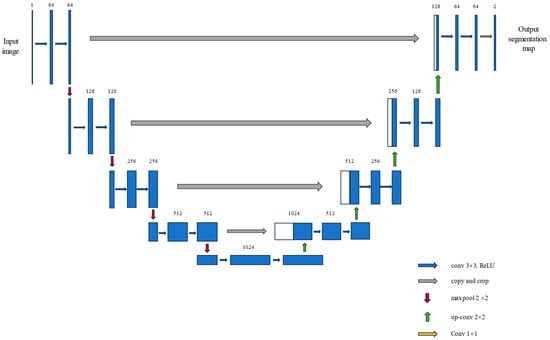

The U-Net architecture, proposed by Ronneberger et al. in 2015 [12], was originally designed for biomedical image segmentation. The architectural structure of the model is illustrated in Figure 1. The key advantage of the model lies in its encoder–decoder structure, enhanced by employing the skip connections, which effectively combine semantic and spatial information [12].

Figure 1.

The network structure diagram of U-Net.

In the field of flotation froth segmentation, U-Net and its variants have become the most widely adopted baseline architectures due to their strong performance in small-object segmentation and their relatively moderate parameter size. The main structure and functional characteristics of the U-Net are summarized as follows:

The encoder of U-Net consists of multiple convolutional blocks, each containing two 3 × 3 convolution layers with ReLU activation and batch normalization (BN), followed by max-pooling for downsampling. This process halves the spatial resolution while doubling the number of channels, gradually extracting high-level semantic features that represent the overall froth contours.

The decoder then restores the spatial resolution through upsampling, combining the high-level semantic features with high-resolution spatial details from the encoder via skip connections. Finally, a 1 × 1 convolution layer produces a binary segmentation probability map distinguishing froth from the background.

While the original U-Net demonstrates satisfactory performance in froth segmentation, it also suffers from notable limitations. First, the direct concatenation of features from different semantic levels leads to feature mismatching, as shallow encoder layers emphasize spatial details but low semantics, whereas deep decoder layers emphasize high-level semantics but limited spatial resolution. Second, the fixed-size convolutional kernels restrict the receptive field, making it difficult to adapt to the wide range of froth scales—especially for small froths with diameters less than 3 cm—resulting in incomplete feature extraction.

2.2. Nested U-Net for Enhanced Multi-Scale Feature Fusion

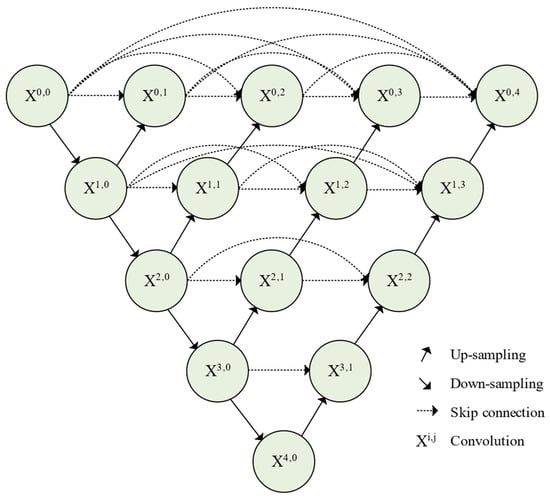

To overcome the feature inconsistency issue of the original U-Net, Zhou et al. (2018) proposed the Nested U-Net, also known as U-Net++ [19]. As shown in Figure 2, this model introduces a densely nested skip-connection structure, forming a pyramid-like multi-scale fusion pathway that enables fine-grained feature integration across different depths.

Figure 2.

Architecture of Nested U-Net.

Compared with the conventional U-Net, the Nested U-Net introduces two key improvements:

- Nested skip connections: Instead of using a single skip connection between corresponding encoder and decoder layers, U-Net++ introduces multiple intermediate convolutional blocks, forming multi-scale fusion pathways. This design enables the gradual integration of shallow spatial features with deep semantic features, thus reducing the semantic gap and improving feature compatibility.

- Multi-output supervision: Multiple output layers are established at different decoder depths, each computing independent losses during training. This multi-task learning strategy ensures that features at different levels are directly optimized through backpropagation, thereby enhancing boundary preservation and improving small-object segmentation.

In flotation froth segmentation, the Nested U-Net generally outperforms the original U-Net. For example, Tang et al. reported that the froth extraction rate of Nested U-Net increased by approximately 8% compared with U-Net. Similarly, Du et al. designed the IG-EMA-U2Net algorithm based on the Nested U-Net framework, which effectively retained boundary details through nested fusion pathways.

However, despite its superior local feature fusion capability, the Nested U-Net still lacks global contextual awareness. The convolutional operations remain inherently local, limiting the receptive field and making it difficult to capture long-range dependencies between froths. When multiple froths adhere to form large agglomerated clusters, this can lead to the model incorrectly classifying them as a single object, which results in inaccurate boundary segmentation [20].

The limitations of both conventional U-Net and Nested U-Net architectures indicate the necessity for global context modeling in froth segmentation networks. Capturing long-range spatial dependencies and maintaining boundary precision simultaneously are essential for addressing the challenges of adhesive and multi-scale froths in complex industrial flotation imagery.

3. Proposed Method

To address the challenges of adhesive froths, multi-scale variations, blurred boundaries, and the limited receptive field of conventional convolutional operations, this study proposes GC-FSegNet. Built upon the Nested U-Net architecture, the proposed model integrates the GCNet attention mechanism, Mish activation function, and a hybrid Dice + BCE loss, enabling global context modeling, weak boundary feature enhancement, and optimized segmentation accuracy. This section elaborates on the network architecture, core module design, and dataset construction.

When multiple froths agglomerate, conventional convolutional layers—which perceive only local boundary segments—fail to determine if these edges belong to a single, larger structure. In contrast, global context modeling aggregates holistic image features to recognize such boundaries as part of a unified froth cluster, thereby avoiding misclassification.

3.1. Overall Architecture and Design Concept

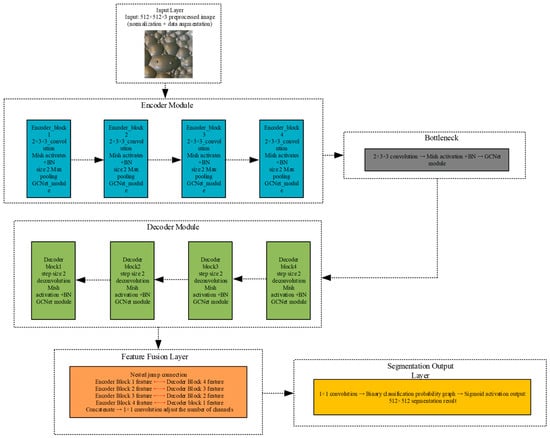

The overall structure of GC-FSegNet is shown in Figure 3. The model follows a modular encoder–decoder architecture comprising six main components: an input layer, encoder, bottleneck, decoder, feature fusion module, and segmentation output layer.

Figure 3.

Overall architecture of GC-FSegNet, Full-process integration of the GCNet module.

- Input layer:The network receives preprocessed froth images of size 512 × 512 × 3, which have been normalized to the [0, 1] range and augmented to enhance robustness against variations in flotation conditions.

- Encoder module:Composed of four nested convolutional blocks, each containing two 3 × 3 convolutional layers, a Mish activation, and a BN layer, followed by 2 × 2 max-pooling for downsampling. A GCNet module is embedded after each encoder block to capture global context features at different scales, reinforcing the representation of macro-level froth structures.

- Bottleneck layer:Situated between the encoder and decoder, this layer comprises two 3 × 3 convolutional layers, Mish activation, BN, and one GCNet module to extract the most abstract global features and model long-range dependencies between froths.

- Decoder module:Consists of four nested convolutional blocks, each using transposed convolution (stride = 2) for upsampling. Before feature fusion, each block integrates a GCNet module that utilizes global contextual cues to guide the refinement of local boundary features.

- Feature fusion layer:Employs nested skip connections to concatenate the upsampled decoder features with their corresponding encoder features, thereby combining semantic information with spatial details. A 1 × 1 convolution is applied after fusion to adjust channel dimensionality and prevent feature redundancy.

- Segmentation output layer:A 1 × 1 convolution maps the fused features to a binary segmentation probability map, followed by a Sigmoid activation that outputs the per-pixel probability of belonging to the froth class.

The entire model is trained in an end-to-end fashion using the Dice + BCE hybrid loss function to measure the discrepancy between predicted and ground-truth masks. Optimization is performed using the Adam optimizer, ensuring adaptive convergence of network parameters.

3.2. GCNet Attention Mechanism for Global Context Modeling

Attention mechanisms enhance model performance by reweighting features according to their importance, enabling the network to focus on key regions—such as froth areas—while suppressing irrelevant background noise. This approach has become one of the most effective techniques for improving segmentation precision [21].

3.2.1. Limitations of Conventional Attention Mechanisms

- Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) Module [22]:SE performs global average pooling to compress spatial information and then uses two fully connected layers to learn inter-channel dependencies. However, it only models channel-wise relationships, ignoring spatial correlations, and thus cannot effectively capture the spatial associations critical for adhesive froth segmentation.

- Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [23]:CBAM extends SE by sequentially applying channel and spatial attention. While it improves performance in general vision tasks, its spatial attention still relies on local convolutions with limited receptive fields, making it unsuitable for modeling long-range dependencies between froths.

- Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) [24]:ECA replaces fully connected layers with adaptive 1 × 1 convolutions to reduce computational cost while maintaining effective channel attention. Nevertheless, it still lacks the capacity to encode global spatial context.

3.2.2. Principle of Global Context Modeling Based on GCNet

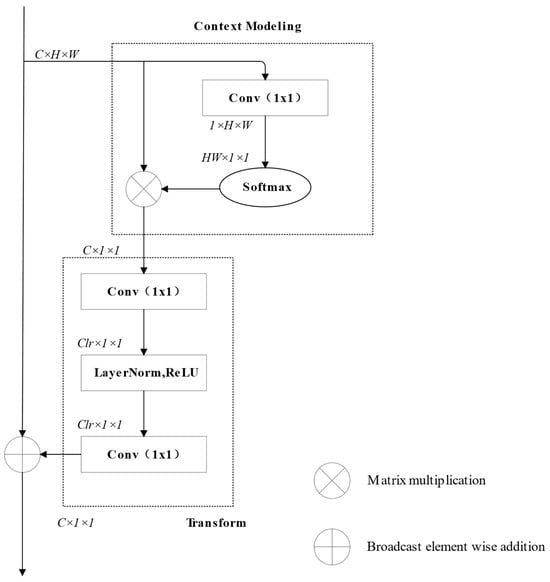

The GCNet, proposed by Cao et al. [25], is designed to efficiently capture long-range dependencies while maintaining computational simplicity, making it ideal for industrial segmentation tasks. As illustrated in Figure 4, GCNet consists of two core components: Context Modeling and Feature Transformation.

Figure 4.

Structure of the GC module.

- Context Modeling:Instead of using simple global average pooling, GCNet employs global attention pooling to compute a weighted global context vector. Specifically, a 1 × 1 convolution first generates attention scores across spatial positions, followed by a Softmax operation to compute spatial weights. The final global context vector is obtained through a weighted summation of all spatial locations.Mathematically:where denotes the input feature, and is a 1 × 1 convolution kernel. This approach adaptively focuses on regions with significant froth boundary features rather than averaging all spatial information equally [26].

- Feature Transformation:Similarly to the SE module, this stage applies two fully connected layers (MLPs) to transform the global context vector , generating channel-wise weights. The first FC layer reduces the channel dimension and applies ReLU activation; the second restores the dimension and applies a Sigmoid to obtain scaling coefficients . The refined feature map is then obtained by element-wise multiplication:

In Equation (2), the role of is to normalize the output to generate “attention weights” between 0 and 1. It quantifies the importance of each feature channel through weights to achieve the screening of the channel attention mechanism. Compared with Non-Local Networks, GCNet reduces computational complexity from to , Where represents the number of channels, represents height, and represents width. increasing parameter count by only ~0.1% while effectively modeling global dependencies.

In GC-FSegNet, integrating GCNet modules enables the network to model the overall spatial distribution and long-range relationships among froths, thereby resolving mis-segmentation of adhesive clusters and improving overall boundary precision.

From a practitioner’s perspective, this global modeling capability is essential for handling ‘froth clustering’ phenomena common in high-grade concentrates. Traditional local convolutions often mistake a cluster of adhesive bubbles for a single large object. By aggregating context from the entire image, GCNet helps the model distinguish the boundaries within these dense clusters, ensuring that the bubble count reflects the true physical state of the froth.

3.3. Optimization Strategies for Model Training

The choice of activation and loss functions significantly impacts the convergence and accuracy of deep learning models. Considering the weak boundaries and class imbalance typical in flotation froth images, consequently, the Mish activation function and Dice + BCE hybrid loss were adopted to enhance model performance.

3.3.1. Mish Activation Function for Weak Boundary Feature Learning

Activation functions introduce nonlinearity to neural networks, allowing them to model complex feature relationships. Conventional functions such as ReLU, Swish, and tanh each have drawbacks: ReLU may cause dead neurons due to zero outputs for negative inputs; Swish offers smoothness but exhibits limited gradient flow in negative domains; tanh can saturate, slowing convergence in deep networks.

Figure 5.

Mish Activation Function and Common Activation Functions.

The Swish and Mish activation functions appear visually similar in their performance in the negative interval, but there are actually fundamental differences between them. Because the Sigmoid function converges to zero extremely rapidly as tends to negative infinity, the output of the Swish function in the negative interval strictly approaches zero. In contrast, the output of Mish in the negative interval approaches zero slowly. This is because converges to zero more gently as tends to negative infinity, resulting in a slower decay of . This difference manifests in gradient calculation and information retention in deep networks, with the result that Mish can retain more gradients of negative features, while Swish suppresses negative features more thoroughly. Mish combines the advantages of smoothness, non-monotonicity, and unboundedness. It preserves small gradients in weak-boundary regions, avoids gradient saturation, and prevents neuron death, making it particularly effective for capturing fine froth edges [28].

In industrial flotation environments, uneven lighting and slurry turbidity often result in bubbles with extremely low contrast (weak boundaries). While standard ReLU activation tends to suppress these weak signals (causing ‘dead neurons’), Mish preserves the gradient flow for negative inputs. This property is particularly crucial for recovering the fine edge details of small bubbles in shadowed regions, thereby improving the robustness of the segmentation against variable lighting conditions.

3.3.2. Hybrid Loss Function for Region–Boundary Balance

Loss functions quantify the discrepancy between predicted and ground-truth masks and guide network optimization. In froth segmentation, single loss functions often fail to balance region completeness and boundary precision.

BCE Loss:

where and denote the predicted and true labels, respectively. BCE is sensitive to class imbalance, often biasing the model toward the majority (background) class.

Dice Loss:

where is a smoothing term. Dice loss effectively measures region overlap but inadequately constrains fine boundary accuracy.

To overcome these limitations, a hybrid Dice + BCE loss is proposed:

This combination leverages the region-overlap optimization of Dice loss and the pixel-wise classification accuracy of BCE loss, ensuring both regional completeness and boundary precision. As a result, the model can mitigate foreground–background imbalance and achieve robust segmentation of froths with fuzzy or complex edges.

For mineral processing engineers, the ultimate goal of segmentation is to obtain accurate BSD curves. This requires not just detecting the bubble (Region) but precisely delineating its contour (Boundary). The proposed hybrid loss specifically addresses this need: the Dice term ensures the overall bubble shape is captured for area calculation, while the BCE term forces the model to sharpen the pixel-level edges, preventing the fusion of adjacent bubbles that would distort BSD statistics.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup and Dataset

4.1.1. Experimental Platform and Parameter Configuration

The experiments were conducted using Python 3.10 as the programming language and the PyTorch 2.5.1 framework for the implementation of GC-FSegNet. The CUDA 11.8 and cuDNN 8.7.0 deep learning acceleration modules were employed to ensure GPU acceleration during training. The following hyperparameters were set for the training process:

Initial learning rate (lr0) = 1 × 10−4

Minimum learning rate (min_lr) = 1 × 10−5

Momentum = 0.9

Optimizer: Adam [29]

Maximum training epochs = 100

Weight decay = 0.001

Batch size = 4

Image size = 512 × 512

The experiments were performed on a Windows 11 system equipped with a 13th Generation Intel® Core™ i5-13400F CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU, ensuring efficient model training for flotation froth image segmentation.

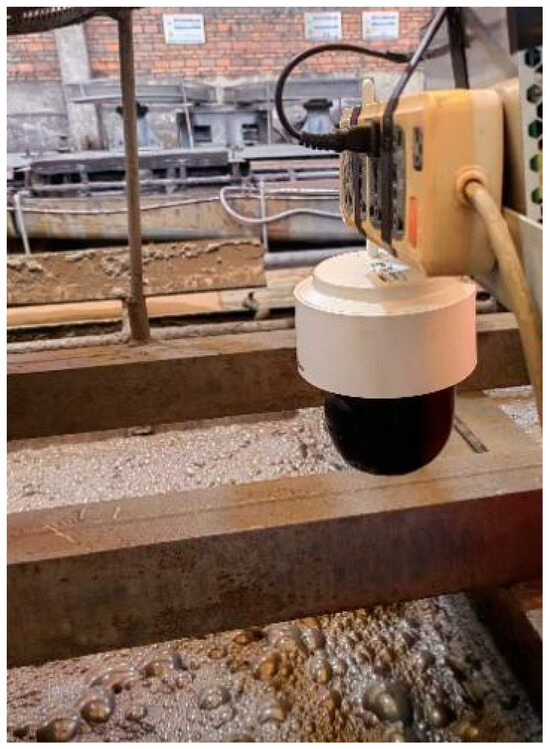

4.1.2. Flotation Froth Dataset Construction and Preprocessing

The dataset used in this study consists of self-collected flotation froth images, captured using a high-definition spherical camera with a 2000 × 2000 pixel resolution and a 3 mm focal length as shown in Figure 6. Each pixel has a bit depth of 24, ensuring high-quality image acquisition. As the flotation process occurs in a copper–lead mineral flotation workshop, the dataset includes images of froths formed in different flotation conditions and with various ore types.

Figure 6.

Spherical camera setup for data collection.

In the copper–lead flotation system, froths vary in size:

Large froths: 8–10 cm diameter

Medium froths: 3–5 cm diameter

Small froths: <3 cm diameter

During rougher flotation, medium froths are more common, while over-mineralized froths tend to be smaller. When the mineralization is poor, small froths merge into larger bubbles, but the larger bubbles may break easily. Froth shape is variable, typically circular but influenced by slurry flow, bubble interactions, and particle adhesion to froth films. When sufficient water is available, the contours are sharp; however, when mineral content is high, froths may become uneven or break apart, causing the contours to blur.

In the annotation process, various tools were tested, and the Photoshop tool combined with LabelMe was used to manually annotate froth regions, producing binary masks. The dataset includes a total of 310 images under varying flotation conditions and mineral types. The dataset was divided into 210 training images, 50 validation images, and 50 test images.

Additionally, several data augmentation techniques were applied to increase dataset diversity and reduce overfitting risks, improving the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. These techniques include:

Random rotations by multiples of 90°

Random horizontal and vertical flips

Random adjustments of brightness and contrast, with brightness and contrast ranges set to [−0.2, 0.2]

Resizing images to 512 × 512 pixels and normalizing pixel values to the [0, 1] range

These transformations improve the model’s robustness against various industrial flotation conditions and enhance training stability by normalizing pixel values and reducing variance across samples.

To ensure the high quality of the dataset, a consensus labeling protocol was employed. Initial annotations were performed using the LabelMe tool, followed by a rigorous cross-check by two independent domain experts. Any ambiguous boundaries were discussed and refined to generate the final high-precision ground truth masks. Furthermore, to evaluate the generalization ability and robustness of the model, we adopted a repeated random sub-sampling validation strategy (Monte Carlo cross-validation). The dataset was randomly split into training, validation, and testing sets three independent times with different random seeds. The quantitative results reported in this paper represent the average performance (mean ± standard deviation) across these three independent experiments.

4.1.3. Model Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of GC-FSegNet for flotation froth segmentation, quantitative metrics were selected based on the specific challenges in froth image segmentation. These metrics include Dice coefficient (mDice), Intersection over Union (mIoU), recall (mRec), precision (mPre), Accuracy, and the F1.

IoU measures the overlap between predicted and ground-truth regions.

Dice coefficient quantifies the similarity between the predicted and true regions.

Recall measures the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples to all actual positive samples.

Precision measures the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples to all predicted positive samples.

Accuracy measures the proportion of all correctly classified pixels.

F1 provides a harmonic mean of precision and recall, offering a balanced assessment of the model’s performance, especially in cases of class imbalance.

The formulas for these metrics are as follows:

Dice coefficient:

where TP means true positives, FP means false positives, and FN means false negatives.

IoU:

Recall:

Precision:

Accuracy:

F1:

where TN represents true negatives. The F1 is a comprehensive metric that balances the trade-off between precision and recall.

To ensure a fair evaluation, all quantitative metrics (Dice, IoU, Precision, Recall, etc.) were computed on the final binarized segmentation masks using a threshold of 0.5.

These metrics provide a comprehensive view of the model’s performance, particularly in terms of segmentation accuracy and robustness under varying flotation conditions.

4.2. Validation of the Proposed Model

This paper combines the aforementioned four quantitative metrics with the U-Net architecture as a baseline to construct networks employing four sets of improvement strategies. Model evaluation on a flotation foam image test set verifies the effectiveness of each module. Specifically, Improvement Strategy 1 employs Nested U-Net, Improvement Strategy 2 combines Nested U-Net with GCNet, Improvement Strategy 3 integrates Nested U-Net with GCNet and Mish, and Improvement Strategy 4 utilizes the proposed GC-FSegNet. The network enhancement results under different improvement strategies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evaluation Metric Results Under Different Improvement Strategies.

The results, summarized in Table 1, demonstrate that:

GC-FSegNet outperforms U-Net and Nested U-Net across all metrics, with mDice improving from 0.8456 to 0.9443, and mIoU increasing from 0.7325 to 0.8945. Similarly, its F1 reaches 0.9785, demonstrating a superior balance between precision and recall compared to the baseline models. This improvement can be attributed to the enhanced feature fusion in the Nested U-Net, which resolves issues related to feature mismatching.

Incorporating GCNet in the Nested U-Net significantly improves the model’s ability to model long-range dependencies, increasing mDice from 0.8606 to 0.9235, and recall from 0.9578 to 0.9766.

Adding the Mish activation function further refines boundary learning, resulting in a higher mDice of 0.9323 and recall of 0.9796. This highlights the boundary-free and smooth nature of the Mish function, which resolves the “neuron death” issue common in the negative value region of traditional ReLU activation functions. It preserves minute gradient information along the weak boundaries of bubbles, enhancing feature learning for fuzzy boundaries. Consequently, it improves recall while also restoring classification accuracy for small bubble pixels, enabling the model to learn complex bubble features more comprehensively.

Finally, the GC-FSegNet model achieves the highest performance with an mDice of 0.9443, an mIoU of 0.8945, and an mRecall of 0.9866, demonstrating its robustness and high segmentation accuracy for froth images, especially in terms of handling weak boundaries and small froth segmentation. Notably, it also achieves the highest accuracy of 0.8582 and F1 of 0.9785, confirming its overall superiority in both pixel-level classification accuracy and model.

4.3. Performance Analysis of the Proposed Model

To further validate GC-FSegNet’s performance, a comprehensive comparison was made with other popular segmentation models, including U-Net, DeepLabV3+, Attention U-Net, and Nested U-Net variants that integrate different attention mechanisms, such as SE, CBAM, and ECA. All models were trained on the same experimental platform and hyperparameter settings.

The results, summarized in Table 2, demonstrate that:

Table 2.

Evaluation results of different models.

GC-FSegNet outperforms the traditional models by a significant margin. Compared with DeepLabV3+, GC-FSegNet achieves a 3.97% improvement in mDice and a 5.35% increase in precision, highlighting the model’s superior boundary detection and small-object segmentation capabilities. Additionally, this model achieved the highest F1 of 0.9785 among all comparison models, indicating its strong ability to balance precision and recall. This confirms its comprehensive segmentation performance.

Further analysis reveals that GCNet’s global context pooling mechanism enables the model to better handle the challenges posed by adhesive and multi-scale froths, especially in comparison with the attention mechanisms used in other models. This design not only improves the segmentation of individual froths but also significantly reduces errors and missed detections.

Table 3 presents the inference performance comparison of various segmentation networks on the RTX 4060. It is evident that the standard U-Net achieves the fastest inference speed, yet its relatively simple network architecture struggles to fully capture complex features. NestedU-Net significantly enhances feature reuse capability through multi-layer skip connections, but its inference time increases to 55.41 ms. DeepLabv3 and AttentionU-Net achieve improved accuracy through the introduction of dilated convolutions and attention mechanisms, respectively, but their inference speeds decrease to 78.83 ms and 70.22 ms, indicating that complex feature extraction modules incur substantial computational overhead.

Table 3.

Processing Speed of Different Network Models.

In contrast, the proposed GC-FSegNet achieves an inference speed of 68.98 ms/frame while maintaining strong feature representation capabilities. It outperforms both AttentionU-Net and DeepLabv3 and achieves a more balanced trade-off between speed and accuracy compared to Nested U-Net variants incorporating GCNet modules. This demonstrates that GC-FSegNet effectively incorporates global contextual information without substantially increasing computational burden, showcasing excellent model architecture optimization. Overall, GC-FSegNet strikes an effective balance between feature extraction capability and inference efficiency, thereby exhibiting significant potential for practical application in complex scene segmentation tasks.

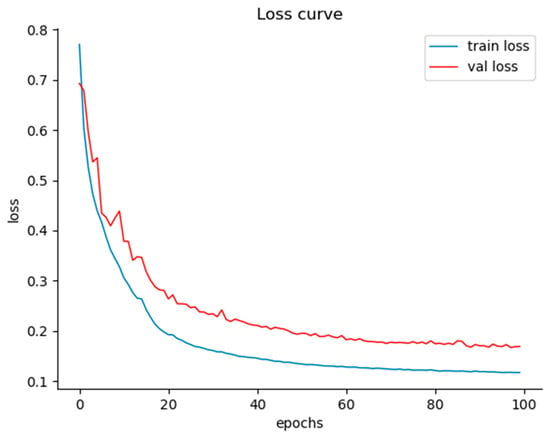

To visually demonstrate the training convergence and generalization capabilities of GC-FSegNet, this paper visualizes its loss curve during training on the flotation foam dataset, with results shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Loss curve of GC-FSegNet during training on the flotation dataset.

This loss curve plots training epochs on the horizontal axis and loss values on the vertical axis, where the blue curve represents training loss and the red curve represents validation loss. The trend reveals that both curves exhibit a rapid decline during the initial training phase, as the model swiftly learns fundamental features of flotation bubbles—such as bubble shape and grayscale distribution. As training progresses, the loss curves gradually stabilize, with the training loss settling around 0.12 and the validation loss stabilizing near 0.18.

This convergence behavior can be explained by two key factors: First, the GCNet module integrated into GC-FSegNet enables global context modeling, the Mish activation function enhances gradient flow, and the combined Dice+BCE loss function balances category weights. These designs endow the model with efficient feature learning capabilities, thereby rapidly reducing loss. Second, strategies such as batch training and dynamic learning rate adjustment effectively prevent overfitting and vanishing gradients. This ensures synchronous convergence of training and validation losses, with their difference consistently maintained within a reasonable range. The loss curve of GC-FSegNet converges stably, achieving low loss values on both training and validation sets. This demonstrates that the segmentation model under GC-FSegNet exhibits high detection accuracy and good fit to the training data, enabling it to reliably perform foam flotation segmentation tasks.

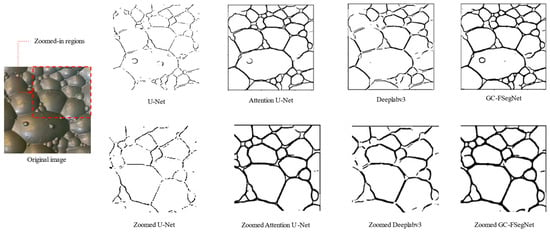

4.4. Visualization and Analysis of Segmentation Results

To provide a more intuitive understanding of the segmentation performance, the results obtained from different models were visualized and compared, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Visualization of segmentation results from different models.

As illustrated in Figure 8, GC-FSegNet demonstrates superior segmentation accuracy and visual quality compared to other models. Based on the global context modeling principle discussed in Section 3.2.2, GC-FSegNet effectively captures long-range dependencies among froths, accurately representing the overall distribution pattern of froth clusters.

When dealing with adhesive froths, GC-FSegNet successfully distinguishes individual bubbles within aggregated clusters, thereby overcoming the common issue of mis-segmentation where multiple adjacent froths are incorrectly identified as a single object. In terms of boundary delineation, the proposed model produces more refined contours than those obtained by U-Net or Attention U-Net, showing clear improvements in edge continuity and completeness. Moreover, GC-FSegNet effectively reduces both false segmentation and missed detections, while maintaining strong performance on small or weakly visible froths.

These precise segmentation outcomes have practical implications for flotation process optimization. For instance:

When the segmentation results reveal uniformly small froths with sparse distribution, this indicates insufficient aeration, suggesting that the airflow rate should be increased to promote the formation of appropriately sized froths.

Conversely, the presence of large adhesive froth clusters may imply excessive slurry concentration; therefore, the slurry density should be adjusted to improve froth dispersion.

However, it is important to emphasize that flotation behavior is governed by multiple interacting physical and chemical factors, including mineral liberation, particle size distribution, pulp chemistry, reagent dosage, and the degree of hydrophobicity of the mineral surfaces. In addition, the froth characteristics vary considerably across different sections of a flotation circuit (rougher, scavenger, and cleaner stages), as well as with ore type and machine configuration.

Consequently, image analysis and modeling of the flotation froth alone cannot directly improve flotation performance. Instead, this approach should be viewed as a complementary diagnostic tool that assists process engineers in understanding system behavior.

In future studies, the proposed vision-based framework will be extended to incorporate additional process variables such as feed grade, reagent concentration, and pulp chemistry, and to integrate with other sensing technologies for comprehensive monitoring of the flotation process.

In particular, further experiments will focus on relatively simple and well-liberated porphyry copper ores and the rougher–scavenger circuits, which may provide a more controlled foundation for model generalization.

Therefore, accurate segmentation provided by GC-FSegNet can serve as a direct visual indicator for optimizing flotation parameters such as aeration rate and slurry concentration. This enables more stable and efficient operation of flotation equipment, providing a solid foundation for the industrial implementation of intelligent process monitoring and control in mineral processing.

5. Discussion

The experimental results presented in Section 4 demonstrate that GC-FSegNet significantly outperforms traditional architectures in handling adhesive and multi-scale froths. While quantitative metrics such as mDice and Accuracy validate the algorithmic superiority, the practical implication of this improvement lies in the reliability of the extracted process data. In industrial flotation, the misclassification of clustered bubbles as single large objects—a common failure mode in U-Net and Attention U-Net—leads to distorted BSD. Specifically, the global context modeling employed by GCNet allows the network to distinguish individual bubbles within dense clusters by aggregating long-range dependencies, rather than relying solely on local edge contrasts. This ensures that the derived morphological parameters reflect the true hydrodynamic conditions of the flotation cell, providing a trustworthy foundation for downstream process analysis.

The transition from raw image segmentation to quantitative feature extraction enables a deeper understanding of the metallurgical process. Key performance indicators derived from the segmentation masks, such as froth velocity, stability, and coverage ratio, serve as direct proxies for mineral recovery and grade. Crucially, the utilization of the Mish activation function in our model enhances the preservation of weak boundary features, which is vital for detecting small bubbles in poorly illuminated or turbulent zones. For instance, a sudden increase in bubble coalescence, accurately delineated by the model’s refined boundary detection, often signals froth instability caused by insufficient frother dosage or excessive pulp density. Conversely, the detection of uniformly small bubbles with sparse coverage provides actionable intelligence regarding poor mineralization. Unlike manual observation, which is subjective and intermittent, the continuous stream of high-fidelity data provided by GC-FSegNet allows process engineers to correlate visual symptoms directly with reagent regimes and hydrodynamic variables.

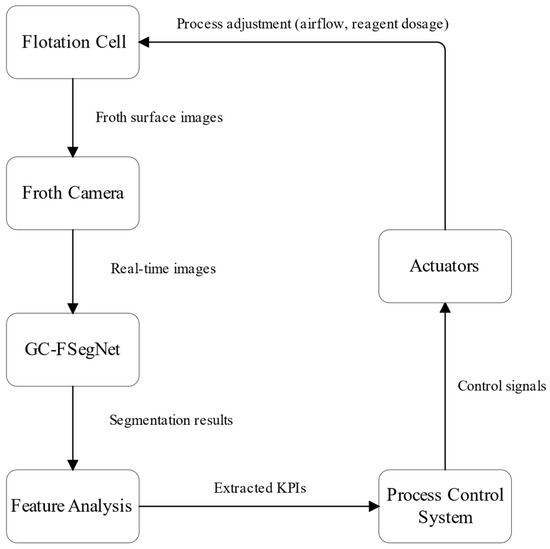

From an engineering perspective, the ultimate value of this vision-based framework is its integration into automated control strategies. As illustrated in Figure 9, the high inference speed of GC-FSegNet satisfies the real-time requirements of industrial control loops. By serving as a robust soft sensor, the proposed network allows for the implementation of closed-loop feedback systems where critical variables—such as air flow rate and reagent dosage—are dynamically adjusted based on the visual state of the froth. This precise control not only optimizes metallurgical indices but also contributes to energy efficiency by preventing over-aeration, aligning with the industry’s push towards smart and sustainable mineral processing.

Figure 9.

Conceptual Framework for Integrating GC-FSegNet into an Automated Flotation Control Loop.

Despite these promising results, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. Flotation behavior is governed by complex physicochemical factors, and froth appearance can vary significantly across different ore types and reagent systems. While GC-FSegNet shows strong robustness on the copper-lead dataset, its generalization to other mineral systems (e.g., coal or gold flotation) may require transfer learning strategies. Furthermore, extreme operating conditions, such as violent surface turbulence, pose challenges for any vision-based system. Future work will focus on deploying this model in edge computing devices at diverse flotation sites to validate its long-term stability and explore adaptive learning mechanisms to handle such process variability.

6. Conclusions

In the flotation process, the visual characteristics of froth—such as bubble size, adhesion, and dispersion—serve as critical indicators of mineral separation efficiency. The ability to accurately segment and analyze froth morphology provides direct insight into the mineralization state of particles and the dynamic balance between air flow, slurry concentration, and reagent dosage. The proposed GC-FSegNet establishes a reliable visual foundation for interpreting these phenomena by accurately delineating froth boundaries and identifying individual bubbles within complex flotation environments. This visual precision enhances the understanding of bubble–particle interactions that govern flotation selectivity and recovery.

By integrating global contextual modeling and fine-grained boundary perception, GC-FSegNet effectively addresses the long-standing challenges of segmenting adhesive and multi-scale froths. The model captures both the macroscopic structure of froth clusters and the microscopic variations at their interfaces, yielding more accurate measurements of froth size distribution, coverage ratio, and stability. These indicators serve as a basis for assessing mineral separation performance, enabling data-driven adjustments to flotation parameters and providing a quantitative link between visual observation and metallurgical outcomes.

From an engineering standpoint, the segmentation results produced by GC-FSegNet can be incorporated into real-time flotation monitoring systems, enabling automatic extraction of froth morphology features to guide parameter optimization. By linking image-derived froth metrics with process control variables, such as air rate and reagent dosage, this approach supports the development of intelligent flotation control strategies. Consequently, the proposed framework not only advances the visual analysis of froth behavior but also offers a practical pathway toward more stable, efficient, and intelligent mineral separation operations in modern flotation plants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.Z. and G.C.; methodology, Z.J.; software, P.Z.; validation, P.Z., G.C. and Z.P.; formal analysis, Z.J.; investigation, P.Z.; resources, G.C.; data curation, Z.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.J.; visualization, P.Z.; supervision, Z.P.; project administration, G.C.; funding acquisition, Z.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52364025.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the reviewers and editors for their opinions and suggestions on this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GC-FsegNet | Global Context-Aware Flotation Froth Segmentation Network |

| GCNet | Global Context Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| FCN | Fully Convolutional Network |

| BSD | Bubble Size Distribution |

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| SE | Squeeze-and-Excitation Network |

| ECA | Efficient Channel Attention |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| BCE | Binary Cross-Entropy |

| Dice | Dice Similarity Coefficient |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| BN | Batch Normalization |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| TP | True Positive |

| FP | False Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

| mDice | Mean Dice Coefficient |

| mIoU | Mean Intersection over Union |

| mRec | Mean Recall |

| mPre | Mean Precision |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| Ir0 | Initial Learning Rate |

| min_lr | Minimum Learning Rate |

| Adam | Adaptive Moment Estimation |

| GC | Global Context |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| GAP | Global Average Pooling |

References

- Qu, J.; Luukkanen, S.; Wan, H. Machine vision-driven analysis of flotation froth properties: A comprehensive review of multidimensional feature extraction and intelligent optimization. Miner. Eng. 2025, 233, 109591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Yu, L.; Shao, P.; An, M.; Wen, S. Recent advances in flotation froth image analysis via deep learning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 147, 110283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhondayi, C.; Moys, M.H.; Tshibwabwa, E. Relationship between froth bubble size estimates and flotation performance in a semi-batch lab cell. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2018, 39, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, C.; Marais, C.; Shean, B.; Cilliers, J. Online monitoring and control of froth flotation systems with machine vision: A review. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2011, 96, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morar, S.H.; Harris, M.C.; Bradshaw, D.J. The use of machine vision to predict flotation performance. Miner. Eng. 2012, 36–38, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendaouia, A.; Abdelwahed, E.; Qassimi, S.; Boussetta, A.; Benzakour, I.; Amar, O.; Bourzeix, F.; Jabbahi, K.; Hasidi, O. Advancing Flotation Process Optimization Through Real-Time Machine Vision Monitoring: A Convolutional Neural Network Approach. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval, KDIR 2023 as part of the 15th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management, IC3K 2023, Rome, Italy, 13–15 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hadler, K.; Greyling, M.; Plint, N.; Cilliers, J.J. The effect of froth depth on air recovery and flotation performance. Miner. Eng. 2012, 36–38, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnowski, P.; Gładysiewicz, L.; Król, R.; Ozdoba, M. Energy Efficiency Analysis of Copper Ore Ball Mill Drive Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, C.; Liu, X. Monitoring of flotation systems by use of multivariate froth image analysis. Minerals 2021, 11, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of Deep Learning: Concepts, CNN Architectures, Challenges, Applications, and Future Directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Aldrich, C. Flotation froth image recognition with convolutional neural networks. Miner. Eng. 2019, 132, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhong, Y. Froth image segmentation algorithm based on improved I-Attention U-Net for zinc flotation. J. Hunan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 50, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehchobogh, B.K.; Kuzekanani, Z.D.; Sobhi, J.; Khiavi, A.M. Flotation froth image segmentation using Mask R-CNN. Miner. Eng. 2023, 192, 107959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Liu, Q.; Liu, G. Flotation Froth Image Segmentation Algorithm for Pyrite Based on IG-EMA-U2Net. Met. Mine 2025, 3, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Flores, A.; Ilyas, S.; Heyes, G.W.; Kim, H. A critical review of artificial intelligence in mineral concentration. Miner. Eng. 2022, 189, 107884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Li, W.; Vercauteren, T.; Ourselin, S.; Cardoso, M.J. Generalised Dice Overlap as a Deep Learning Loss Function for Highly Unbalanced Segmentations. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, D.; Wan, K. A froth velocity measurement method based on improved U-Net++ semantic segmentation in flotation process. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 1816–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11531–11539. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, J.; Lin, S.; Wei, F.; Hu, H. GCNet: Non-Local Networks Meet Squeeze-Excitation Networks and Beyond. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the Difficulty of Training Deep Feedforward Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), Sardinia, Italy, 13–15 May 2010; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, D. Mish: A Self Regularized Non-Monotonic Neural Activation Function. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08681. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, D. Flotation bubble size distribution detection based on semantic segmentation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 11842–11847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).