Abstract

To address the issues of high cost and poor low-temperature adaptability in cement-based backfill materials, this study developed a high-volume fly ash-based solid waste cementitious backfill material (FAPB) along with a specialized low-temperature admixture. Investigated the fundamental properties and microscopic curing mechanisms of the FAPB at different temperatures. The results indicate that the yield stress and plastic viscosity of FAPB slurry increase with higher contents of the curing agent and admixture, and rise as the temperature decreases. The variation in slump flow aligns with the rheological parameters, with the minimum slump flow being 14.5 cm (>10 cm). Bleeding rate increases with decreasing amounts of curing agent and admixture content, as well as lower temperatures, reaching a maximum bleeding rate of 9.26% (T5C10). Setting time decreases with increased amounts of curing agent and admixtures, and significantly increases with decreasing temperature. Strength increases with curing time and curing agent content, but decreases significantly as temperature drops. Adding admixtures can compensate for strength deterioration caused by low temperatures, with an optimal dosage of 3%. Microstructural analysis showed that the main hydration products of hardened backfill include AFt, C-S(A)-H, and Ca(OH)2. Low temperature (5 °C) restricts hydration product formation, and the admixture facilitates continuous polycondensation of C-S(A)-H gel, resulting in sustained strength gain. This study provides a theoretical basis for the preparation and application of low-temperature-resistant Fly ash-based backfill materials, holding significant importance for advancing green mining practices in cold regions.

1. Introduction

As mining activities expand further, the relationship between “environment and development” has become a contentious issue. On the one hand, mining drives economic growth and social progress; on the other, it causes environmental pollution that threatens societal advancement. To achieve sustainable mining, the industry must embrace “green mining” practices. This entails promoting cleaner production wherever possible, enhancing resource and energy utilization rates, and advancing comprehensive waste utilization to propel the mining sector toward sustainable development.

Backfill mining has emerged as a core technology for green mining, given its ability to effectively control surface subsidence, enhance resource recovery rates, and enable the utilization of solid waste [1,2,3]. Currently, mine backfilling primarily relies on cement-based systems, which face the following challenges: Firstly, high costs. Cement accounts for 60%–70% of the total cost of backfill materials, and the need for additional strength-enhancing agents in low-temperature environments further increases expenses [4,5]. Secondly, poor adaptability to low temperatures. Low temperatures significantly inhibit the hydration reaction rate of cementitious backfill materials, resulting in reduced strength that increases only slowly over extended curing periods. This severely compromises the stability of the backfill body and mining productivity [6,7]. With the continuous growth in global demand for mineral resources, mining activities expanding into deeper strata and cold regions have become an inevitable trend. Therefore, developing high-solid-waste-content, low-cost, and low-temperature-resistant backfill materials has become crucial for the sustainable development of cold-region mines.

Coal-fired power plants are often located near mining areas. Burning one ton of coal produces 2.4 tons of CO2 and emits no less than 0.1 tons of fly ash (FA) [8]. Currently, China’s annual FA emissions have reached 600 million tons, showing a gradual increasing trend [9]. Due to its rich content of silico-aluminate active components, FA can form stable hydration products under alkaline activation, making it a commonly used pozzolanic material [10]. Therefore, FA is widely used in the concrete and construction industries [11]. Although the resource utilization pathways for FA are quite diverse, large numbers of power plants are concentrated around typical energy and mineral bases. The emitted FA is too concentrated to be fully utilized and continues to accumulate, posing serious environmental pollution risks [12].

Backfill technology, leveraging its advantage in large-scale solid waste disposal, has become the optimal method for handling FA. In recent years, numerous scholars have focused on developing new backfill materials from solid wastes such as fly ash (FA) and investigating their temperature-dependent behavior [13,14,15]. Studies consistently demonstrate that appropriate FA dosage significantly enhances both the mechanical properties and flow characteristics of filling materials. However, for low-temperature mining areas, ensuring the quality of the filling body is crucial for safe production. Therefore, the impact of temperature on the performance of filling materials is of paramount importance. Xiang He et al. investigated the mechanical properties of coal-based cemented backfill at 20–50 °C [16]; Pan Yang et al. studied the influence of fly ash content on the mechanical and microstructural properties of magnesium-based solid waste backfill at 20–40 °C [17]; Sada Haruna et al. found that the reactivity of FA-substituted cementitious filling material systems is highly dependent on curing temperature [18]. Chang Cai et al. examined the degradation mechanism of coal gangue-fly ash backfill under combined high-temperature (40 °C) and salt erosion conditions [19]; Meng Wang et al. explored the effects of temperature (20–90 °C) and bleeding on the rheological properties of cement slurry [20]. While studies such as these are too numerous to list individually, most share a common characteristic: they focus on ambient or elevated temperatures, while the influence of low-temperature conditions has been largely overlooked. However, in cold-region mines, ensuring the quality of the backfill material is crucial for safe production.

Therefore, this study developed a high FA content-based solid waste cemented backfill material (FAPB) and a dedicated low-temperature admixture. The system investigated the influence laws of curing time, curing agent and admixture content on the flow characteristics, bleeding rate, setting time and strength of backfill materials under room temperature and low temperature environments, and revealed the hardening mechanism of backfill materials based on microscopic analysis. This research provides a basis and theoretical guidance for the preparation, performance regulation and on-site application of low-temperature-resistant FAPB, which is of great significance for the promotion and application of FA-based solid waste backfill technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

The raw materials used in this paper are FA, curing agent and a small amount of self-developed admixtures.

2.1.1. Fly Ash

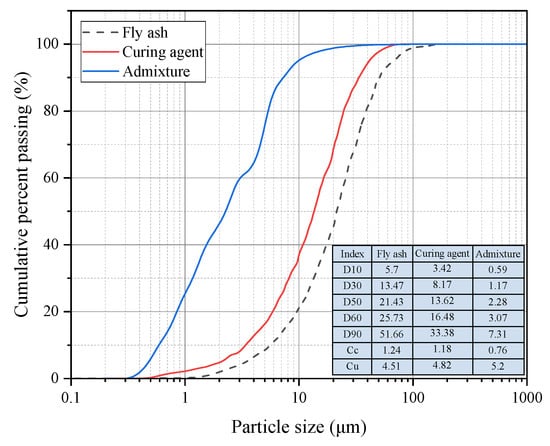

FA is from coal-fired power plants around the mine. The chemical composition of FA was tested using an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Bruker, S8 TIGER, Bill Ricard, MA, USA), as shown in Table 1. The content of SiO2 in FA is more than 50%, and the content of A12O3 is relatively high, indicating its potential activity is higher; CaO content is less than 10%, which is class F ash (i.e., low calcium ash). The particle size distribution of FA measured using a particle size analyzer (Malvern, Mastersizer 3000, Worcestershire, UK) is shown in Figure 1. The FA particle size is concentrated between 5 μm and 70 μm, and the D50 is 21.43 μm. The FA’s coefficient of unevenness (cu) and coefficient of curvature (cc) are 4.51 and 1.24, respectively. The specific gravity of FA is 2.097, and the loose bulk density is 0.935 g/cm3.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of raw materials.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution of raw materials.

2.1.2. Curing Agent (Binder)

The curing agent is a self-developed hydraulic cementitious material. Its primary components include S95-grade blast furnace slag powder (S95 slag, 50%), fly ash (10%), desulfurization gypsum (10%), lime (10%), and high-heat clinker (20%), which are compounded and ground together. The main component of desulfurization gypsum is dihydrate gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O), with an effective content exceeding 90%. Lime consists mainly of calcium oxide (CaO), which undergoes rapid hydration upon contact with water, releasing substantial heat and generating Ca(OH)2. This provides an alkaline environment that activates pozzolanic materials, stimulating the pozzolanic reaction of active silicon-aluminum components in FA and granulated blast furnace slag [21]. The chemical composition of the compound curing agent used in this study is presented in Table 1, and its particle size distribution is shown in Figure 1. The particle size of the curing agent ranges predominantly from 2 μm to 50 μm, with a D50 of approximately 13.62 μm, indicating a finer gradation compared to FA.

2.1.3. Admixture

The admixture used in this study is a self-developed composite material comprising powder and liquid components (BGRIMM, ZQ-D02). The particle size distribution of the powder is shown in Figure 1. This admixture utilizes sulfoaluminate cement clinker as a dispersant, with other components including small amounts of water glass, sodium hydroxide, nitrates, and organic constituents (such as triethanolamine). Its primary function is to activate the curing agent in low-temperature environments, enhancing the early activity of the FA system to thereby improve the strength of the backfill.

2.2. Sample Preparation

The sample preparation was carried out according to the ratios in Table 2. Firstly, the appropriate amounts of FA and the compound curing agent were weighed according to the ratios and mixed evenly by stirring. Then, a certain weight of admixture was weighed and added to the mixing water, and stirred evenly before being added to the dry materials. The mixture was quickly stirred until completely mixed. Finally, the prepared slurry was taken out for initial performance testing or used to prepare backfill test blocks. Among them, the mixing water is ordinary tap water.

Table 2.

Mix Design of studied samples.

When preparing the backfill test blocks, the slurry should be poured into molds with dimensions of 70.7 mm × 70.7 mm × 70.7 mm, leveled off, and then placed, respectively, in curing chambers with humidity ≥90% and temperatures of 20 ± 1 °C, 10 ± 1 °C and 5 ± 1 °C. After curing to the specified age (3 d, 7 d, 14 d and 28 d), relevant tests should be conducted.

2.3. Experimental Method

2.3.1. Fluidity Test

Fluidity was evaluated by slump flow and rheological tests based on the mixes in Table 2. Slump flow tests followed Chinese National Standard GB/T 51450-2022 [22].

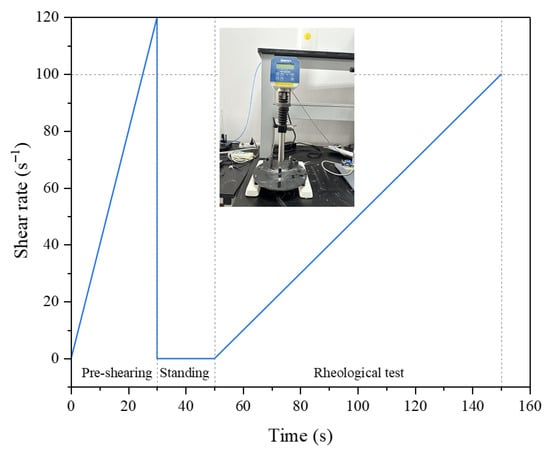

Rheological properties were measured with a Brookfield RST-SST rheometer (Middleboro, MA, USA) under a controlled shear rate mode. First, pre-shear the FAPB slurry at a high shear rate (120 s−1) for 30 s. Subsequently, set the shear rate to increase from 0 to 100 s−1 (100 s), with the program automatically recording data every second (Figure 2). A Bingham model (Equation (1)) was used to analyze the rheological parameters from the data.

where τ is the shear stress (Pa), τ0 is the yield stress (Pa), η is the plastic viscosity (Pa·s), and is the shear rate (s−1).

Figure 2.

Rheological testing procedures and equipment for FAPB slurry.

2.3.2. Bleeding Rate Test

The bleeding rate is a key indicator for evaluating the solid–liquid separation tendency of a solid–liquid two-phase slurry. Excessive bleeding rate can affect the performance of the backfill material and increase the amount of underground drainage work. Bleeding rate tests followed Chinese National Standard GB/T50080 [23].

2.3.3. Setting Time Test

The setting time was measured using a standard Vicat apparatus, specifically following the Chinese National Standard GB/T 1346 [24].

2.3.4. Uniaxial Compressive Strength Test

The uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) tests were conducted at specified curing ages using an AEC-01 strength testing machine. The machine was calibrated prior to testing, and a controlled displacement rate of 1 mm/min was applied. Three specimens were tested for compressive strength at each age, and the final result was taken as the average of the three values.

2.3.5. Microscopic Test

Hardened specimens cured for 28 d were subjected to microstructural morphology and phase composition analysis after hydration termination. The microscopic morphology of the backfill material was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss, Sigma 300, Oberkochen, Germany), and the phase composition of the hydration products was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker, D8, Bill Ricard, MA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fluidity of FAPB Slurry

3.1.1. Rheological Property

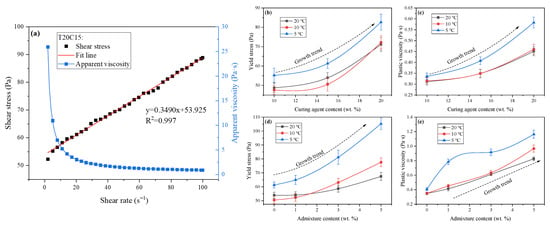

Figure 3a illustrates typical rheological curves of the FAPB slurry within the shear rate range of 0–100 s−1, which can be described by the Bingham model. The rheological parameters of slurries with different ratios obtained by fitting the Bingham model are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Rheological curves and parameters of the FAPB slurry. (a) Typical rheological curves of the FAPB slurry. (b,c) show the influence of curing agent content on rheological parameters at different temperatures. (d,e) show the influence of admixture content on rheological parameters at different temperatures.

Table 3.

Rheological test results of backfill slurry.

Figure 3b,c illustrate the influence of curing agent content on rheological parameters at different temperatures. When the temperature is held constant, both the yield stress (τ0) and plastic viscosity (η) increase with rising curing agent content. Notably, the difference in rheological parameters between the samples at 20 °C and 10 °C is minimal and almost negligible. At 5 °C, the τ0 values for T5C10, T5C15, and T5C20 are 55.198, 61.331, and 82.651 Pa, respectively, with corresponding η values of 0.3363, 0.4077, and 0.5831 Pa·s. Indicates that increased curing agent content leads to reduced flowability. This can be attributed to two main factors. Firstly, the curing agent has a finer particle size compared to FA. As the curing agent content increases and replaces more FA, the overall particle size distribution of the system becomes finer, resulting in a higher relative consistency at the same mass concentration. Secondly, although a higher curing agent content affects the hydration process to some extent, this influence is minimal in the fresh slurry state.

When the curing agent content remains constant, both τ0 and η generally increase with decreasing temperature, which is consistent with the findings reported by Cheng Haiyong et al. [25]. When the curing agent content is 20%, its τ0 values at 20 °C, 10 °C, and 5 °C are 71.180, 72.221, and 82.651 Pa, respectively, with corresponding η values of 0.4511, 0.4607, and 0.5831 Pa·s. Overall, the effect of temperature on rheology is less significant than that of curing agent content. The mechanism by which temperature affects fluidity is a coupled effect involving both physical and chemical processes. At an ideal temperature, further increasing the temperature promotes hydration, while the basic water requirement of the system also increases, jointly enhancing the inter-particle forces and thereby reducing fluidity. However, for systems with slow reaction rates, the influence of hydration on the fresh slurry is relatively minor. When the temperature decreases, the viscosity of free water increases, while the Brownian motion of molecules weakens. This affects the formation of the water film around particles, collectively leading to an increase in the viscosity of the slurry. However, for rapid-reacting systems, hydration exhibits greater sensitivity to temperature, leading to precisely the opposite effect [26].

Figure 3d,e illustrate the influence of admixture content on the rheological parameters of FAPB slurry under different temperatures. When the temperature is held constant, both τ0 and η increase with rising admixture content. This is because the particle size of the admixture is relatively small, and its addition leads to an increase in concentration. Additionally, the introduction of the admixture accelerates the dissolution of the particles, disrupts the water film on the particle surfaces, and alters the electrostatic repulsion and van der Waals forces between the particles [27,28]. The rheological parameters of the samples with the same mix proportion exhibit minimal differences between 20 °C and 10 °C, which is consistent with the previous pattern. This finding further confirms that reducing the temperature from 20 °C to 10 °C does not significantly affect the fluidity of the FAPB slurry. At 5 °C, the τ0 values for samples with admixture contents of 0%, 1%, 3%, and 5% were 61.331, 65.002, 81.216, and 105.228 Pa, respectively, while the corresponding η values were 0.4077, 0.7841, 0.9174, and 1.1644 Pa·s. Compared to the control group (0%), the sample with 5% admixture content exhibited increases of 71.57% in τ0 and 185.60% in η. This indicates the existence of a critical point between 10 °C and 5 °C, as the hydration kinetics, interparticle physical forces, and water viscosity within the system exhibit nonlinear temperature dependence. Prior to this critical point, the influence of these factors is relatively minor or mutually counteracting, resulting in minimal changes. Upon reaching the critical point, however, the hydration rate declines sharply, water viscosity increases significantly, and the dispersing efficiency of admixtures decreases substantially. Consequently, rheological parameters undergo pronounced alterations [29].

When the admixture content remains constant, both τ0 and η generally increase with decreasing temperature. The τ0 values for T20A3, T10A3 and T5A3 are 58.661, 63.096 and 81.216 Pa, respectively, and the η values are 0.6122, 0.6334 and 0.9174 Pa·s, respectively. The maximum increases are 38.45% and 49.85%, respectively. The addition of admixtures leads to reduced slurry flowability. This is primarily because, after dispersing within the system, the admixtures increase the flocculation structure of the slurry, thereby raising its viscosity. Generally, to ensure adequate fluidity, the τ0 of backfill slurry should not exceed 200 Pa [30]. The τ0 values of FAPB are significantly lower than this threshold.

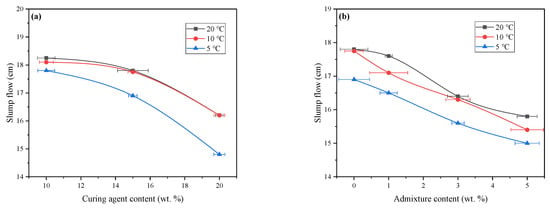

3.1.2. Slump Flow

Figure 4 presents the slump flow test results of backfill slurry with different mix proportions. The variation trend of slump flow with curing agent content was consistent across the three temperature series, showing a progressive decrease as the curing agent content increased. The curves for 20 °C and 10 °C nearly overlapped, consistent with the rheological observations. At 20 °C, the slump flow values of samples with curing agent contents of 10%, 15%, and 20% were 18.25, 17.80, and 16.2 cm, respectively. At 5 °C, the corresponding values were 17.80, 16.90, and 14.80 cm. When the temperature decreased below 10 °C, the reduction in slump flow became progressively more significant with increasing curing agent content.

Figure 4.

The slump flow of FAPB slurry at different temperatures. (a) Effect of curing agent content. (b) Effect of admixture content.

When the admixture content increased from 0% to 5% (20 °C), the slump flow of the slurry continuously decreased from 17.8 cm to 15.8 cm. This indicates that the addition of the admixture significantly enhances the interparticle interactions within the slurry, thereby increasing flow resistance. Notably, as the ambient temperature decreases, the reduction in fluidity caused by the increase in admixture content is markedly amplified. For example, at 10 °C, the increase in admixture content from 0% to 5% resulted in a slump flow reduction of 2.95 cm, which is significantly greater than the reduction observed at 20 °C (2.0 cm). When the admixture content remains constant, the slump flow of the samples decreases with reducing temperature. This observation aligns with the variation trends of the rheological parameters discussed earlier. Additionally, the slump flow of T5A5 (14.5 cm) was lower than that of T103 (16.0 cm), indicating that temperature exerts a more pronounced effect on the flowability of the mortar.

Overall, increasing the content of the curing agent or admixture, as well as reducing the environmental temperature, adversely affect the slump flow of the slurry. Generally, a slump flow below 10 cm is considered indicative of poor fluidity. However, the FAPB slurry demonstrates a slump flow of ≥14.5 cm, and combined with its rheological data, it confirms that the FAPB slurry exhibits excellent flow and transport properties.

3.2. Bleeding Rate and Setting Time

3.2.1. Bleeding Rate

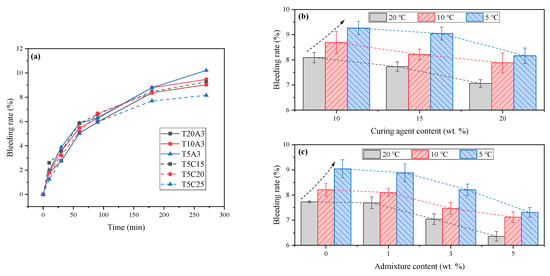

Figure 5a illustrates the variation pattern of the bleeding rate of FAPB slurry over time. The bleeding rate curves of samples with different mix proportions exhibit a consistent trend: initially increasing with time before gradually stabilizing. The influence of curing agent content on the final bleeding rate of the backfill slurry is illustrated in Figure 5b. At 20 °C, the bleeding rates of samples with curing agent contents of 10%, 15%, and 20% were 8.09%, 7.73%, and 7.06%, respectively. Due to the finer particle size of the curing agent, higher curing agent content requires more water, resulting in a lower bleeding rate. The same trend was observed at 10 °C and 5 °C. Conversely, when the curing agent content was constant, lower temperatures led to higher bleeding rates. For example, the bleeding rates of the sample with 15% curing agent content at 20 °C, 10 °C, and 5 °C were 7.73%, 8.21%, and 9.04%, respectively.

Figure 5.

The bleeding rate of FAPB slurry. (a) The variation pattern of the bleeding rate of FAPB slurry over time. (b) Effect of curing agent content. (c) Effect of admixture content.

The influence of admixture content on the final bleeding rate of the FAPB slurry is shown in Figure 5c. As the admixture content increases, the bleeding rate gradually decreases. At 5 °C, the bleeding rates of samples with admixture contents of 0%, 1%, 3%, and 5% were 9.04%, 8.88%, 8.21%, and 7.31%, respectively. Regardless of whether the variable is the curing agent or admixture, the bleeding rate of samples with the same mix proportion increases as temperature decreases. The underlying reason is that low temperatures significantly retard the hydration reaction of the system while also slowing the diffusion of water through the particle matrix. This provides more time for solid particles to settle under gravity and for water to separate and rise, leading to increased bleeding [31]. Simultaneously, during the sedimentation and consolidation process, the reduced distance between particles and enhanced interparticle interactions also affect the rheological parameters of the slurry [20].

3.2.2. Setting Time

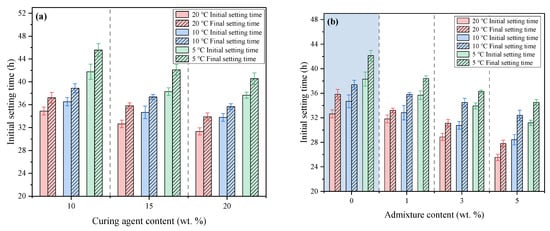

The influence of curing agent content on the setting time of the FAPB slurry is shown in Figure 6a. At 20 °C, the initial setting times of samples with curing agent contents of 10%, 15%, and 20% were 38.30 h, 34.67 h, and 33.92 h, respectively, while the final setting times were 34.89 h, 32.64 h, and 31.34 h. As the curing agent content increased, both the initial and final setting times shortened to some extent. Compared to T20C10 (34.89 and 37.22 h), the initial and final setting times of T20C20 were shortened by 10.17% and 8.92%, respectively. As the temperature decreased, the setting times of the samples significantly prolonged. The initial setting times for T20C15, T10C15, and T5C15 were 32.64, 34.67, and 38.30 h, respectively, while their final setting times were 35.81, 37.37, and 42.12 h, respectively.

Figure 6.

The Setting time of FAPB slurry at different temperatures. (a) Effect of curing agent content. (b) Effect of admixture content.

The influence of admixture c on the setting time of the FAPB slurry is shown in Figure 6b. At a constant temperature, increasing the admixture content gradually shortened the setting time of the samples. Taking T20A3 as an example, its initial and final setting times were reduced by 21.72% and 22.37%, respectively, compared to T20A0 (32.64 and 35.81 h). When the admixture content remained constant, a decrease in temperature significantly prolonged the setting time. The initial setting times for T20A3, T10A3, and T5A3 were 28.87, 30.75, and 33.92 h, respectively, while their final setting times were 31.10, 34.48, and 36.30 h, respectively. Compared to T20A3, the initial and final setting times of T10A3 and T5A3 increased by 6.51%, 10.87%, 17.49%, and 16.72%, respectively. This further demonstrates that temperature is the primary factor influencing setting. Although low temperatures prolong the setting time, no non-setting situation occurred. Therefore, backfilling remains feasible as long as the strength meets the required standards.

3.3. Mechanical Properties of FAPB

3.3.1. Influence of Curing Agent Content

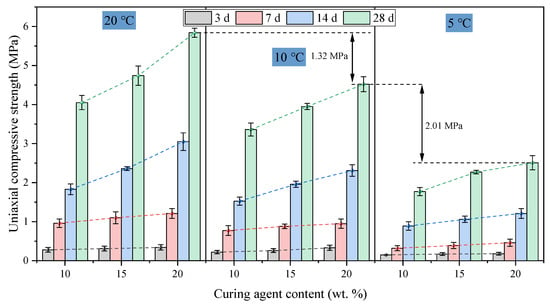

The influence of curing agent content on the UCS of hardened backfill is shown in Figure 7. The strength of FAPB increases with curing age, exhibiting rapid early strength development followed by a gradual slowdown and stabilization in later stages. At each curing stage, when the temperature is constant, a higher content of the curing agent results in greater strength. At 20 °C, the 28 d strengths of T20C10, T20C15, and T20C20 are 4.05, 4.74, and 5.84 MPa, respectively. The strength increased almost linearly with curing age, and the rate of increase was higher with greater curing agent content, indicating the excellent long-term strength development capability of FAPB. The strength differences between T20C10 and T20C20 at 3 days and 28 days were 0.06 MPa and 1.79 MPa, respectively. In the early stages, the effect of increased curing agent content on strength was not significant; noticeable differences in strength only emerged after 7 d, which is related to the pozzolanic reaction mechanism of the system.

Figure 7.

The influence of curing agent content on the UCS of hardened FAPB.

At 10 °C, the 28 d strengths of T10C10, T10C15, and T10C20 were 3.36, 3.95, and 4.52 MPa, respectively. At 5 °C, the 28 d strengths of T5C10, T5C15, and T5C20 were 1.77, 2.27, and 2.51 MPa, respectively. After reducing the curing temperature, the general trends of strength development with curing age and curing agent content remained consistent. In all temperature environments, increasing the curing agent content enhanced the strength at each curing age. However, as the temperature decreased, the strength of samples with the same curing agent content declined significantly. The 28 d strength of samples cured at 5 °C was only equivalent to the strength achieved at 7–14 d under 20 °C conditions. For example, the 28 d strength of T20C20 is 5.84 MPa, while the strength reduction for T10C20 and T5C20 reaches 22.60% and 57.02%, respectively. This further confirms that the hydration rate of the system is highly dependent on the ambient temperature, as higher temperatures significantly promote molecular activity of the reactants, thereby accelerating and enhancing the formation of a network structure.

Additionally, at low temperatures, the strength gain from increasing the curing agent content diminishes significantly. At 5 °C, the strength difference between samples with 10% and 20% curing agent content at 3 days and 28 d was 0.03 MPa and 0.74 MPa, respectively. According to the Arrhenius equation, the chemical reaction rate decreases by approximately half for every 10 °C drop in temperature [32]. Low-temperature conditions severely inhibit reaction activity, resulting in a loose microstructure with numerous defects and delayed strength development. Therefore, under low-temperature conditions, simply increasing the curing agent content cannot fully compensate for the performance loss caused by the slowed reaction.

3.3.2. Influence of Admixture Content

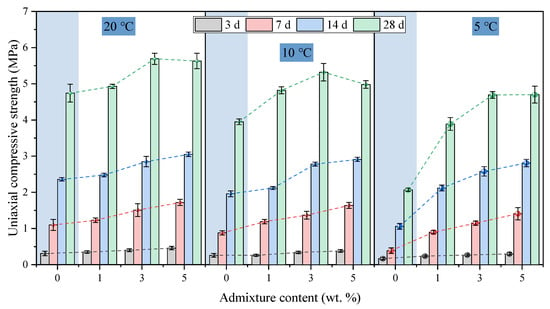

The influence of admixture content on the UCS of hardened backfill is shown in Figure 8. At 20 °C, the 28 d strengths of T20A0, T20A1, T20A3, and T20A5 were 4.74, 4.93, 5.69, and 5.63 MPa, respectively.

Figure 8.

The influence of admixture content on the UCS of hardened FAPB.

At 14 d and earlier, the strength gradually rose with increasing admixture content. By 28 d, the strength increase was relatively modest (0.95 MPa) when the admixture content increased from 0% to 3%, indicating that the primary reactions had largely proceeded to completion. However, a further increase from 3% to 5% led to a slight decrease in strength (–0.03 MPa), suggesting that excessive admixture may have adverse effects. Despite this, the enhancing effect of the admixture remained significant compared to the control group. Specifically, the 28 d strength of samples with 1%, 3%, and 5% admixture increased by 4.01%, 20.04%, and 24.89%, respectively, compared to the control group at the same age. The primary components of admixtures comprise various salt-alkali composite materials, which rapidly dissolve and accelerate the erosion of active silica-alumina-based substances within the system. Additionally, owing to their finer particle size, these admixtures exhibit superior physical filling and dispersion effects, providing more reaction nucleation sites and thereby accelerating the precipitation of hydration products [33,34,35,36]. Furthermore, the admixture provided more pronounced benefits at early ages. For example, sample T20A3 exhibited strength increases of 29.03%, 37.27%, 20.76%, and 20.04% at 3, 7, 14, and 28 d, respectively, compared to the control.

Observation of results at 10 °C and 5 °C revealed that at any constant temperature, incrementally increasing admixture content (0–5%) enhanced strength at various ages to varying degrees, with more pronounced strength gains at lower temperatures. This is because at room temperature, the reaction rate of the system is already approaching its maximum threshold, and even the addition of accelerators yields relatively limited improvements in hydration. However, at low temperatures, the baseline strength is lower, making the benefits of admixtures particularly crucial. At 20 °C, 10 °C, and 5 °C, the maximum increases in 28 d strength for samples containing admixtures relative to their control groups were 24.89%, 34.68%, and 127.05%, respectively. Among these, the 28 d strength of T5A5 (4.70 MPa) showed the greatest relative increase compared to T5A0 (2.07 MPa), yet remained lower than T20A0 (4.74 MPa). This indicates that while admixtures partially compensate for low-temperature disadvantages, they cannot overcome the inherent limitations imposed by temperature on chemical reaction kinetics. However, more admixture does not necessarily yield better results. For instance, at 10 °C, the 28 d strength of T10A1, T10A3, and T10A5 increased by 22.03%, 34.68%, and 26.08%, respectively, compared to T10A0. At 5 °C, the 28 d strength of T5A1, T5A3, and T5A5 increased by 87.92%, 126.57%, and 127.05%, respectively, compared to T5A0. Considering the overall economic cost and benefit, the admixture content should not exceed 3%. In summary, low temperatures lead to strength reduction regardless of the presence of the admixture. Nevertheless, through the combined action of the admixture and extended curing time, the long-term strength can still reach a satisfactory level.

3.4. Microscopic Curing Mechanism

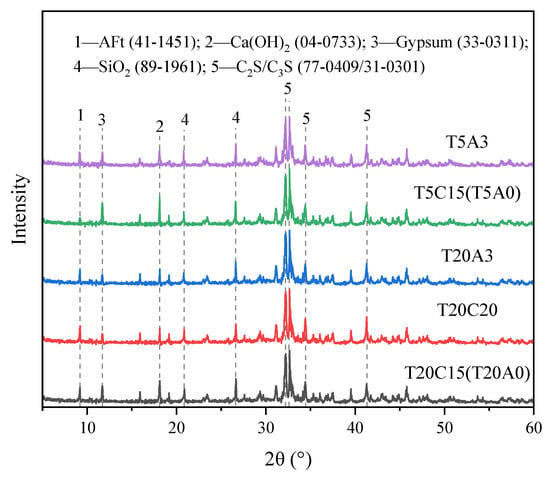

3.4.1. XRD Analysis

XRD analysis was conducted on samples T20C15, T20C20, T20A3, T5C15, and T5A3 after 28 d of curing (Figure 9). The results revealed that the primary hydration products in the hardened backfill include ettringite (AFt), hydrated gel (C-S(A)-H), Ca(OH)2 (CH), among others [37,38]. In addition, there are also non-hydrated product components such as SiO2 contained within the material itself.

Figure 9.

XRD pattern of FAPB after 28 d of curing.

There were no significant differences in the types of hydration products of different samples. Comparing T20C15 and T20C20, it was observed that after increasing the curing agent content, the actual system contained a higher proportion of gypsum. However, the characteristic peaks for gypsum and CH (Ca(OH)2) were notably reduced. This indicates that the increased curing agent content enhanced the synergistic effects within the system, accelerating both the hydration and pozzolanic reactions. As a result, more gypsum was consumed to form AFt. The lack of a significant increase in AFt may be attributed to its possible conversion to AFm [39]. Comparing T20C15 and T5C15 reveals that the decrease in temperature leads to a significant reduction in AFt. The enhanced CH peak results from the system’s slow hydration rate for CH formation exceeding the rate of CH consumption by the pozzolanic reaction, a finding further supported by the increased gypsum peak. Comparing T20A0 and T20A3 with T5A0 and T5A3 reveals that the gypsum and CH peaks are significantly reduced, while the AFt peak shows an increase but remains lower than that of the 20 °C sample. These results demonstrate that although the admixture promotes the hydration process, it cannot fully counteract the adverse effects of low temperature. This finding aligns with the observed strength development patterns.

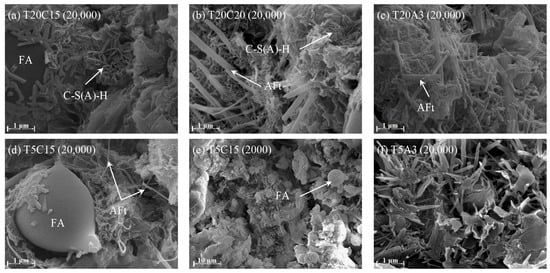

3.4.2. SEM Analysis

To further investigate the microstructural differences in grout under various conditions, SEM observations were conducted on the microstructures of T20C15, T20C20, T20A3, T5C15, and T5A3 grouts cured for 28 days. The results are shown in Figure 10. It can be observed that, in addition to spherical FA particles, the predominant hydration products are acicular AFt and honeycombed hydrated gel (C-S(A)-H).

Figure 10.

SEM image of FAPB after 28 d of curing.

The primary pozzolanic materials in the FAPB system are FA and slag, whose pozzolanic reaction is a complex multi-step process. In the early stages, a small amount of clinker phase materials (tricalcium silicate, dicalcium silicate, etc.) undergo hydration to form CH and C-S-H gel, providing early strength and creating a strongly alkaline environment. Additionally, admixtures can stimulate the reactivity of FA. Under the influence of admixtures, the covalent bonds between Si-O-Si and Si-O-Al in FA and slag are broken, causing the network structure to depolymerize. This releases active ions such as SiO44− and AlO45−. When the concentration of Ca2+ in the pore solution reaches an oversaturation level with the concentrations of dissolved SiO44− and AlO45−, new hydrated products will precipitate out. The main products include C-S-H and C-A-H gels. Due to the presence of desulfurized gypsum in the system, it will react with active Al2O3 to form AFt, which is a key reaction for obtaining early strength [40,41]. As the hydration process continues, C-S(A)-H keeps growing and interlaces with AFt, enhancing the uniformity and compactness of the backfill body and continuously increasing its strength [42,43].

Al2O3 + 3Ca(OH)2 + 3CaSO4·2H2O + 23H2O →

3CaO·Al2O3·3CaSO4·32H2O

3CaO·Al2O3·3CaSO4·32H2O

Comparing Figure 10a,b, it is observed that when the curing agent content increases from 15% to 20% (Figure 10b), the AFt in the sample becomes significantly more abundant and better developed, exhibiting a slender and interlaced morphology. This is because when the amount of curing agent increases, the particle gaps at the physical level become smaller. At the chemical level, the content of the curing agent per unit volume is higher, and in the combined action with FA, more hydration gels are produced, significantly enhancing the strength. Comparing Figure 10a,d,e, it is observed that when the temperature decreases from 20 °C to 5 °C, the amount of hydration products significantly diminishes, becoming insufficient to fully encapsulate the FA. Moreover, the AFt become scattered and sparse, leaving numerous unfilled voids, which results in a significant reduction in strength. Comparing Figure 10a,c with Figure 10d,f, it is observed that when 3% of the external agent is added at 20 °C and 5 °C, respectively, the main hydration products significantly increase in quantity and become more dense. However, at 20 °C, they are significantly more developed and denser than at 5 °C. The microstructural results show remarkable consistency with the strength patterns, indicating that the admixture significantly accelerates the hydration process, partially compensating for the strength loss caused by low temperatures. Although temperature significantly affects the formation quantities of C-S(A)-H and AFt, it does not influence the types of products formed. Even under low-temperature conditions, the pozzolanic and hydration reactions in the system proceed stably, and strength continues to increase steadily after sufficient hydration time.

4. Conclusions

This study developed a fly ash-based solid waste backfill material (FAPB) and a dedicated low-temperature admixture, systematically investigating the effects of curing agent and admixture content on the fundamental properties of FAPB at different temperatures. The main conclusions are as follows:

- The rheological curves of fresh FAPB slurry conform to the Bingham model. At a constant temperature, τ0 and η increase with increasing content of curing agent or admixture. With identical mix proportions, τ0 and η increase as temperature decreases. The difference in flowability at 20 °C and 10 °C is relatively small, but it decreases significantly at 5 °C. At 5 °C, T5C20 exhibits the highest τ0 and η values, reaching 82.651 Pa and 0.5831 Pa·s, respectively. The variation pattern of slump flow aligns with rheological parameters, with a minimum slump flow of 14.5 cm (>10 cm), indicating excellent flowability of FAPB.

- At the same standing time, the lower the content of curing agent or admixture, the higher the bleeding rate. With identical mix proportions, the bleeding rate increases with decreasing temperature, reaching a maximum of 9.26% (T5C10). At the same temperature, the setting time gradually shortens with increasing content of curing agent or admixture, with the effect of admixture being more pronounced. The final setting time of T20C20 was 8.92% shorter than that of T20C10 (37.22 h). The final setting time of T20A3 was 22.37% shorter than that of T20A0 (35.81 h). Setting time markedly increased with decreasing temperature. When temperature decreased from 20 °C to 5 °C, the final setting time of the C15 series increased by 6.31 h, while that of the A3 series increased by 5.20 h.

- The UCS of FAPB increases with curing age, and higher curing agent content correlates with greater UCS. Specifically, the 28 d UCS of T20C10 and T20C20 are 4.05 MPa and 5.84 MPa, respectively. As temperature decreases, the strength of samples with the same mix ratio drops significantly. The 28 d UCS of T10C20 and T5C20 decreased by 22.60% and 57.02%, respectively, compared to T20C20 (5.84 MPa). The addition of admixtures enhanced UCS at all ages, with the greatest increase (127.05%) observed at 5 °C, though still lower than results obtained at 20 °C. Considering the overall economic cost and benefit, the admixture content should not exceed 3%.

- The primary hydration products of hardened FAPB include AFt, C-S(A)-H, and Ca(OH)2. Increased curing agent content promotes more developed AFt formation, thereby enhancing strength. When temperature decreases from 20 °C to 5 °C, hydration products significantly diminish and the overall structure becomes more porous. Admixtures facilitate the dissolution of active substances within the system, thereby promoting AFt and gel formation, compensating for strength deterioration caused by low temperatures.

In summary, FAPB demonstrates excellent adaptability to low-temperature environments when combined with admixtures, offering a technical solution to the challenge of strength development in backfill systems within cold regions. However, the effectiveness of admixtures in other backfill systems remains unclear, presenting a subject requiring further exploration in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.W. and S.R.; methodology, C.Y.; validation, G.R. and R.H.; investigation, C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R. and W.W.; writing—review and editing, R.H.; project administration, G.R. and C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deep Earth Probe and Mineral Resources Exploration— National Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2024ZD1003705); The Youth Science and Technology Innovation Fund of BGRIMM (04-2362).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Shishan Ruan and Chao Yang were employed by the company BGRIMM Technology Group. Author Runing Han was employed by the company Xizang Huatailong Mining Development Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| FAPB | Fly ash-based solid waste cementitious paste backfill material |

| FA | Fly ash |

| CH | Ca(OH)2 |

| AFt/AFm | Ettringite/Monosulfoaluminate |

| C-S(A)-H | Hydrated gel |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| UCS | Uniaxial compressive strength |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| τ0 | Yield stress |

| η | Plastic viscosity |

| τ | Shear stress |

| Shear rate |

References

- Cheng, H.; Wu, A.; Wu, S.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Niu, N. Research Status and Development Trend of Solid Waste Backfill in Metal Mines. Chin. J. Eng. 2022, 44, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, T.; Qin, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liang, B.; Zhao, J.; Zuo, S. Preparation of Self-Consolidating Cemented Backfill with Tailings and Alkali Activated Slurry: Performance Evaluation and Environmental Impact. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, S. Recycling Quarry Dust as a Supplementary Cementitious Material for Cemented Paste Backfill. Minerals 2025, 15, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, L.; Monzó, J.; Bonilla, M.; Tashima, M.M.; Payá, J.; Borrachero, M.V. Effect of Pozzolans on the Hydration Process of Portland Cement Cured at Low Temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 42, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Gao, L.; Wu, A.; Feng, Y.; Tao, Y.; Wang, D. Alkaline-Washed Phosphogypsum-Based Cemented Paste Backfill Prepared Using Steel Slag and Blast Furnace Slag: Mechanical Properties, Fluoride Immobilization, and Hydration Mechanism. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e04028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Jiang, H.; Ren, L.; Cui, L.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z. Improving Early-Age Performance of Alkali-Activated Slag Paste Backfill with Calcium Salts at Low Temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134608.1–134608.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, A.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Jin, F.; Yang, X.; Zhou, F. Effect of low temperature on early strength of cemented paste backfill from a copper mine and engineering recommendations. Chin. J. Eng. 2018, 40, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.-J.; Iizuka, A.; Shibata, E. Utilization of Low-Calcium Fly Ash via Direct Aqueous Carbonation with a Low-Energy Input: Determination of Carbonation Reaction and Evaluation of the Potential for CO2 Sequestration and Utilization. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 288, 112411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Han, J. Hazards of Fly Ash and Its Utilization Status. China Resour. Compr. Util. 2022, 40, 118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, S.K.; Ghosh, C.N.; Mishra, D.P.; Singh, P.; Mishra, K.; Buragohain, J.; Mandal, P.K. Strength Development and Microstructural Investigation of Lead-Zinc Mill Tailings Based Paste Backfill with Fly Ash as Alternative Binder. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 109, 103553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K.; Kumar, R.; Naik, B.S. Effect of Curing Temperature on Mechanical, Durability, and Microstructural Properties of Blended Pure Phases of Cement with Fly Ash and Limestone. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2025, 102, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Du, W.; Jin, Y.; Li, Y. Performance and Hydration Mechanism of Fly Ash Coal-Based Solid Waste Backfill Material Affected by Multiple Factors. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Wang, H.; Dong, L.; Zhao, X.; Jin, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Lv, D. One-Part Alkali-Activated Wood Biomass Binders for Cemented Paste Backfill. Minerals 2025, 15, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Gao, J. Utilization of Industrial Solid Waste as Binders in Cemented Paste Backfill (CPB): Mechanisms, Challenges, and Prospects. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 202, 107720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.K.; Mishra, D.P.; Singh, P.; Mishra, K.; Mandal, S.K.; Ghosh, C.N.; Kumar, R.; Mandal, P.K. Utilization of Mill Tailings, Fly Ash and Slag as Mine Paste Backfill Material: Review and Future Perspective. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 309, 125120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wei, L.; Yang, K.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hou, Y. Effects of Curing Temperature and Age on the Mechanical Properties and Damage Law of Coal-Based Solid Waste Cemented Backfill. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e04937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, L.; Suo, Y.; Zhu, M.; Xie, G.; Deng, S. Mechanical Properties, Pore Characteristics and Microstructure of Modified Magnesium Slag Cemented Coal-Based Solid Waste Backfill Materials: Affected by Fly Ash Addition and Curing Temperature. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 176, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, S.; Fall, M. Reactivity of Cemented Paste Backfill Containing Polycarboxylate-Based Superplasticizer. Miner. Eng. 2022, 188, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Li, F.; Fan, S.; Yan, D.; Sun, Q.; Jin, H.; Shao, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, M. Investigation on Deterioration Mechanism of Geopolymer Cemented Coal Gangue-Fly Ash Backfill under Combined Action of High Temperature and Salt Corrosion Environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 398, 132518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, P.; Yan, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, M. Effects of Temperature and Bleeding on Rheology of Cement Paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 403, 133085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, A.; Wang, S.; Wu, P. Utilization of Alkaline Additives for Backfilling Performance Improvement of Sulphide-Rich Tailings. Environ. Res. 2025, 283, 122188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 51450; Technical Standards for Mine Backfill in Metal and Non-Metal Mines. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 50080; Standard for Test Method of Performance on Ordinary Fresh Concrete. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB/T 1346; Test Methods for Water Requirement of Standard Consistency, Setting Time and Soundness of the Portland Cement. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Cheng, H.; Wu, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Influence of Time and Temperature on Rheology and Flow Performance of Cemented Paste Backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 231, 117117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Taheri, A.; Karakus, M.; Chen, Z.; Deng, A. Effects of Water Content, Water Type and Temperature on the Rheological Behaviour of Slag-Cement and Fly Ash-Cement Paste Backfill. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambara Júnior, L.U.D.; de Matos, P.R.; Lima, G.S.; Silvestro, L.; Rocha, J.C.; Campos, C.E.M.; Gleize, P.J.P. Effect of the Nanosilica Source on the Rheology and Early-Age Hydration of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Qiu, J.; Jiang, H.; Xing, J.; Sun, X.; Ma, Z. Flowability of Ultrafine-Tailings Cemented Paste Backfill Incorporating Superplasticizer: Insight from Water Film Thickness Theory. Powder Technol. 2021, 381, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, S.; Noman Husain, M.; Chaudhary, S. Factors Affecting the Rheology of Cement-Based Composites: A Review. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 108, e20429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, H.; Guo, L.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wei, X. Experimental on Rheological Properties of Composite Aggregate Filling Slurry Based on Response Surface Methodology. Nonferrous Met. 2022, 12, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Wang, K. Influence of Bleeding on Properties and Microstructure of Fresh and Hydrated Portland Cement Paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 115, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalal, D.; Danzandorj, S.; Bayarjavkhlan, N.; Nishiwaki, T.; Yamamoto, K. Compressive Strength Development and Durability Properties of High-Calcium Fly Ash Incorporated Concrete in Extremely Cold Weather. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 316, 125801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçaözoğlu, K.; Akçaözoğlu, S.; Açıkgöz, A. Investigation of Hydration Temperature of Alkali Activated Slag Based Concrete. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 2994–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Varga, I.; Castro, J.; Bentz, D.P.; Zunino, F.; Weiss, J. Evaluating the Hydration of High Volume Fly Ash Mixtures Using Chemically Inert Fillers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananyachandran, P.; Vasugi, V. Development of a Sustainable High Early Strength Concrete Incorporated with Pozzolans, Calcium Nitrate and Triethanolamine: An Experimental Study. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 54, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Chen, H. The Role of Fly Ash Microsphere in the Microstructure and Macroscopic Properties of High-Strength Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 83, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Wu, H.; Zhang, K.; Liao, H.; Ma, Z.; Cheng, F. Effect of Curing Temperature on the Reaction Kinetics of Cementitious Steel Slag-Fly Ash-Desulfurized Gypsum Composites System. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 62, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, B.; Yang, L.; Kang, M. Recycling Multisource Industrial Waste Residues as Green Binder for Cemented Ultrafine Tailings Backfill: Hydration Kinetics, Mechanical Properties, and Solidification Mechanism. Powder Technol. 2024, 441, 119799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Adesanya, E.; Ohenoja, K.; Kriskova, L.; Pontikes, Y.; Kinnunen, P.; Illikainen, M. Byproduct-Based Ettringite Binder—A Synergy between Ladle Slag and Gypsum. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wan, Z.; de Lima Junior, L.M.; Çopuroğlu, O. Early Age Hydration of Model Slag Cement: Interaction among C3S, Gypsum and Slag with Different Al2O3 Contents. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 161, 106954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, B.A.; Hamada, H.M.; Almeshal, I.; Bakar, B.H.A. Durability and Mechanical Properties of Cement Concrete Comprising Pozzolanic Materials with Alkali-Activated Binder: A Comprehensive Review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.; Liu, L.; Zhu, M.; Shao, C.; Xie, L. Development and Field Application of a Modified Magnesium Slag-Based Mine Filling Cementitious Material. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahoui, H.; Maruyama, I.; Vandamme, M.; Pereira, J.-M.; Mosquet, M. Impact of Alkalis and Shrinkage-Reducing Admixtures on Hydration and Pore Structure of Hardened Cement Pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 184, 107620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).