Abstract

The Baoshan Terrane, as a passive continental margin during the subduction of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean and the lower plate during collision, exhibits a poorly understood magmatic history. This region is characterized by limited magmatic activity and scarce field outcrops, which has hindered a comprehensive understanding of its petrogenesis and geological evolution. This paper presents a chronological and geochemical study of two different types of syn-collisional granites identified in the Mengnuo and Muchang areas in the southern Baoshan Terrane. Our results show that the two types of granites are high-fractionated S-type granites in Bangdong pluton from Mengnuo (zircon U-Pb ages of 230.3 ± 1.4 Ma, 228.7 ± 1.6 Ma and 230.2 ± 1.1 Ma) and A-type granites in Muchang (zircon U-Pb ages of 232.3 ± 1.8 Ma), respectively. Their formation ages are close to the timing of collision, belonging to syn-collisional granites. The Mengnuo high-fractionated S-type granites have SiO2 contents ranging from 75.15 to 77.78 wt.% with A/CNK of 1.14 to 5.09, and are strongly peraluminous, high-K calc-alkaline granites. They display negative zircon εHf(t) values (−7.72 to −12.32), indicating derivation from partial melting of ancient crustal materials followed by extensive fractional crystallization. In contrast, the Muchang A-type granites contain 73.26 to 76.41 wt.% SiO2, exhibit low A/CNK ratios (0.92–1.46, average = 1.07), and high Zr + Nb + Ce + Y abundances (313.7 to 3000.3 ppm), characterizing them as weakly peraluminous A-type granites. Further classification reveals that the Muchang granites belong to A1-type granites with positive εHf(t) values (+4.01 to +8.46), indicating the involvement of mantle-derived materials in their magma sources. In this case, combined with results from relevant studies in the Changming-Menglian suture zone, we propose that the Late Triassic magmatism in the Baoshan Terrane was likely triggered by slab break-off during syn-collisional stage. Slab break-off might cause mantle upwelling, resulting in large-scale Lincang batholith and associated volcanic rocks in the upper plate as well as various magmatism activities (S-type and A-type felsic rocks and intraplate basalts) in the Baoshan Terrane.

1. Introduction

As critical sites for the demise of oceanic plates and continental amalgamation, collision zones are characterized by complex geological evolutionary processes and magmatic responses (e.g., [1,2,3,4,5,6]). The collision process can be subdivided into four distinct stages based on different deep-seated mechanisms, including: (1) the pre-collision (subduction) stage, (2) the syn-collision stage, (3) the tectonic transition stage, and (4) the post-collision stage, each characterized by corresponding magmatic activities [7,8,9]. From the perspective of the primary driving force of collision (slab pull force, [10]), the syn-collision stage can be defined as the period between initial collision and slab break-off [9].

Syn-collision magmatism has long been a focus of academic research [11]. However, several challenges persist, including the ambiguous delineation of collision stages [12,13], difficulty in constraints collision timing [14,15], and the limited occurrence of syn-collision magmatic rocks. Consequently, the origins and geodynamic processes of syn-collision magmatism remain debated; in particular, the lower plate in a collision zone. Subduction zones have a clear division into upper (active continental margin) and lower plates (passive continental margin), a distinction that can also be applied to continental collision zones. The upper plate in a collision zone corresponds to the upper plate of the pre-collisional oceanic subduction zone, and the same applies to the lower plate. The syn-collisional lower plate is typically regarded as stable and, consequently, its magmatic record is often sparse or absent. The mechanisms generating syn-collision magmatism on lower plate have been extensively investigated in the Himalayan Terrane of the India-Asian collision zone. The Himalayan region hosts contemporaneous collision-related adakitic granites [16,17], diabase dikes [18,19], and gneiss domes. Based on these geological examples, previous studies have proposed two novel mechanisms for syn-collision magmatism on lower plate: (1) Lithospheric deformation model, during early stage of continent–continent collision, lithospheric deformation leads to the upwelling of asthenospheric and lithospheric melts that intrude the base of the crust. This process not only generates mantle-derived magmas with enriched signatures but also causes extensive anatexis and metamorphism of the thickened crust [18]; (2) Slab break-off model, break-off of the subducted oceanic crust at greater depths allows upwelling asthenosphere to melt, producing mafic rocks with depleted isotopic characteristics [19]. These insights provide fresh perspectives for understanding the genetic mechanisms of syn-collision magmatism.

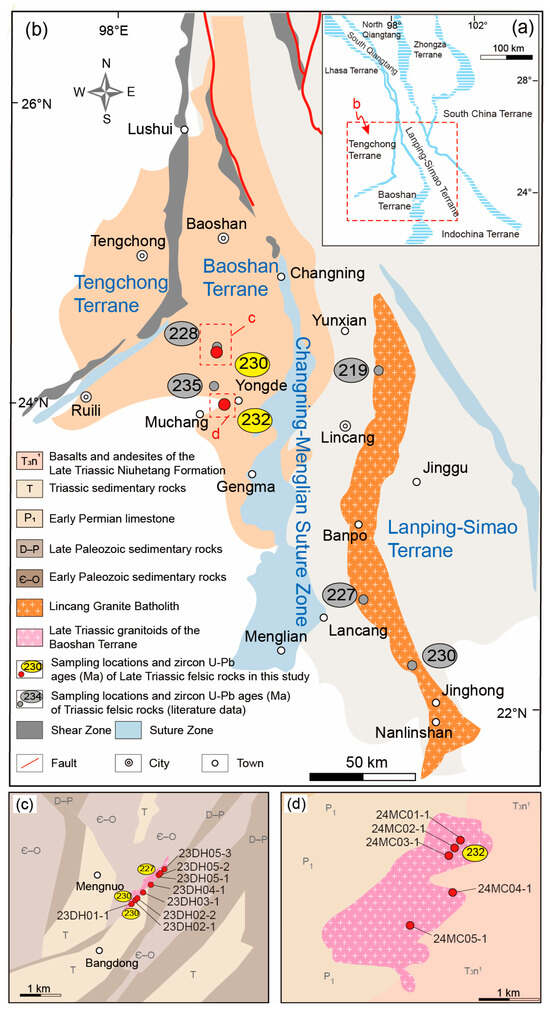

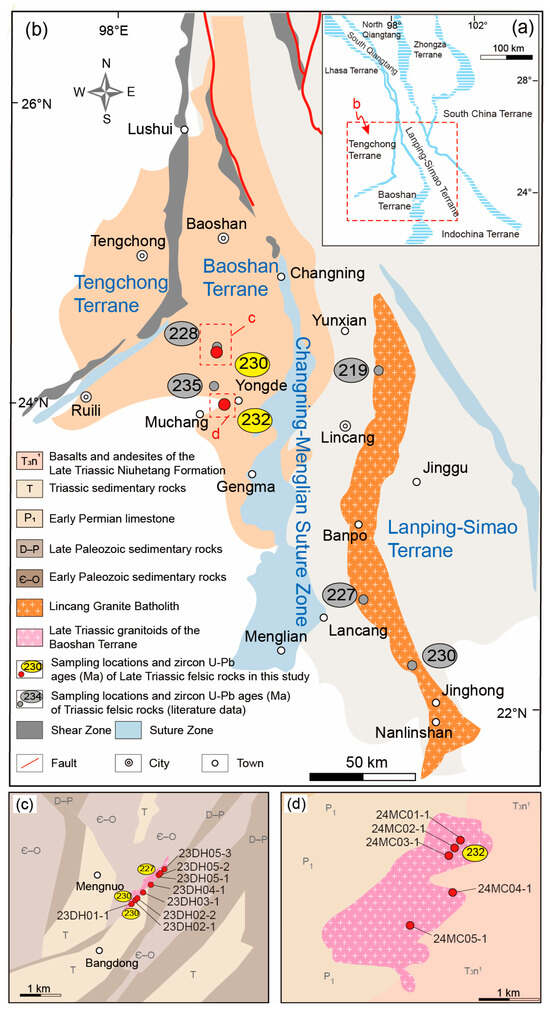

The Changning–Menglian Paleo-Tethys Ocean, situated between the Baoshan and Simao Terranes (Figure 1a), served as the main oceanic basin during the Paleo-Tethyan stage [20,21]. Multi-disciplinary evidence constrains the closure of the Changning–Menglian Paleo-Tethys Ocean at approximately 237 Ma, the ages of the syn-collision and post-collision are about 237–230 Ma and about 230–200 Ma, respectively [22,23,24,25,26,27]. As a passive continental margin during the subduction of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean and the lower plate in the collision process, the Baoshan Terrane exhibits relatively limited magmatism. Previous studies on magmatic activity in this Terrane have primarily focused on Carboniferous-Early Permian mafic rocks, which are interpreted as intraplate magmatism related to rifting. These magmas were derived from an enriched and metasomatized lithospheric mantle beneath the passive margin, and were likely controlled by the mantle plume-induced breakup of Gondwana and the opening of the Neo-Tethys Ocean [28,29]. In contrast, Late Triassic syn-collision magmatism in the Baoshan Terrane mainly comprises intraplate basalts [30], highly fractionated granites [31], and A-type granites [32,33]. However, the petrogenesis and geodynamic processes of these rocks remain poorly understood.

To address these issues, we conducted comprehensive analyses of whole-rock major and trace elements, zircon U-Pb dating, and Hf isotope compositions on granite samples from the Mengnuo and Muchang areas in the Baoshan Terrane. The results provide critical constraints on the petrogenesis and geodynamic processes of the Late Triassic syn-collisional granites in the Baoshan Terrane, as well as new evidence for understanding magma genesis within the lower plate of collisional zones.

2. Regional Geological Background

Located in the southwestern part of the Sanjiang Tethyan Domain, the Baoshan Terrane represents the northern extension of the Sibumasu Terrane and preserves critical records of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean evolution from late Paleozoic expansion, subduction, continent–continent or arc–continent collision, to post-collisional processes. Since the late Paleozoic, the eastern margin of the Baoshan Terrane has been in a passive continental margin setting of the Paleo-Tethys, depositing passive margin sedimentary assemblages exemplified by the Gengma Nanpihe Group (Late Devonian to early Late Permian) and the Cangyuan Papai Formation (late Late Permian to Early Triassic) [20,22,34].

2.1. Mengnuo

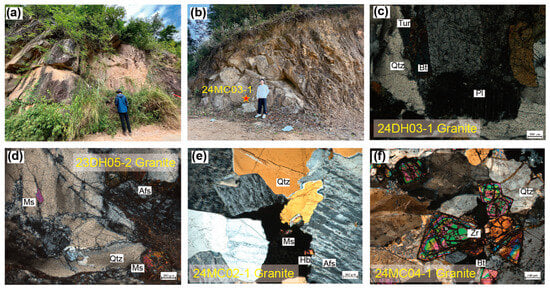

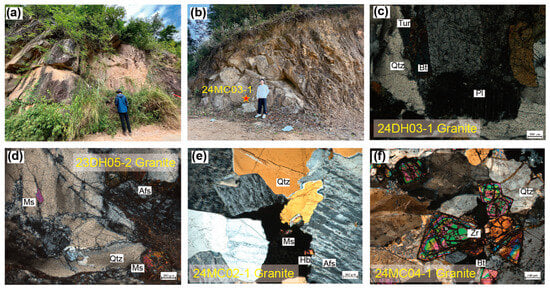

The Mengnuo area is situated in the southern part of the Baoshan Terrane (Figure 1b), southeast of Baoshan City, Yunnan Province, China. The sampling location for this study is the Bangdong pluton (Figure 1b). The Bangdong pluton extends in a NE–SW direction along the Mengboluo River fault zone and has a relatively small outcrop area. The wall rocks consist of Cambrian Subformation 1, which includes grey rhythmic slate interbedded with metamorphosed sandstone, Subformation 3, comprising grey slate with interlayers of metamorphosed sandstone and siliceous rock, as well as the Upper Triassic Nanshuba Formation, composed of shale, marl, and limestone, and the Dashuitang Formation, consisting of limestone and chert-banded limestone (Figure 1c). The granite samples collected from the Bangdong pluton are primarily mylonitized alkaline granite and mylonitized medium-grained syenite granite. The samples exhibit varying degrees of mylonitization (Figure 2b), with mylonitic matrix content ranging from 10% to 50%. The essential minerals include quartz (30%), K-feldspar (20%), muscovite (15%), plagioclase (15%), and biotite (10%), while accessory minerals include zircon, among others. Under the microscope, quartz appears as anhedral grains, 2–5 mm in size, occasionally showing fractures (Figure 2c). Quartz grains are predominantly xenomorphic (anhedral) and granular, exhibiting minor fractures, with grain sizes ranging from 2 to 6 mm, and displaying undulatory extinction. Plagioclase occurs as subhedral tabular crystals with well-developed polysynthetic twinning, having a long axis of up to 3 mm (Figure 2c). K-feldspar appears as tabular-prismatic crystals, showing slight kaolinization on the surface, and ranges from 0.2 to 0.5 mm in grain size (Figure 2d).

Figure 1.

(a) Tectonic framework of the Sanjiang orogenic belt [35,36], (b) tectonic and magmatic features map of the Baoshan Terrane [37], (c) simplified geological map of the Bangdong granites in the Mengnuo area [38], and (d) simplified geological map of the granites in the Muchang area, showing sampling sites of this study [33,39].

Figure 2.

Field photos of the (a) Mengnuo and (b) Muchang granites, (c,d) petrographical photos of the Mengnuo granites, and (e,f) petrographical photos of the Muchang granites. Abbreviations: Qtz = quartz, Pl = plagioclase, Ms = muscovite, Bt = biotite, Zr = zircon, Afs = alkali feldspar, Hb = Hornblende, Tur = Tourmaline.

2.2. Muchang

The Muchang area is located in the southern part of the Baoshan Terrane (Figure 1b). It is characterized by outcrops of Ordovician to Triassic clastic rocks, carbonates, mafic to intermediate volcanic rocks, and minor Carboniferous volcanic units (Figure 1d). The area exhibits well-developed faults and folds, resulting in a complex structural framework dominated by a series of NE–NW trending open folds and parallel faults. Overall, these structures form a V-shaped tectonic pattern that divides the area into trapezoidal segments [29]. The granite samples collected from Muchang display medium- to coarse-grained textures (Figure 2b). The main mineral assemblage consists of K-feldspar (20%), plagioclase (10%), and quartz (45%), with zircon as the primary accessory mineral. Under the microscope, quartz occurs as anhedral grains, 2–5 mm in size, occasionally exhibiting fractures and undulatory extinction (Figure 2e). Most feldspar crystals are euhedral, with a subset showing polysynthetic twinning. Quartz fills interstitially between feldspar crystals. K-feldspar appears as tabular-prismatic crystals, showing slight kaolinization on the surface, and ranges from 0.3 to 0.5 mm in grain size. In sample 24MC04-1 (Figure 2f), ca.500 μm megacryst zircon grains are observed, appearing yellow-green to pink-green under plane-polarized light. It exhibits a tetragonal prismatic or short prismatic morphology with distinct zoning and high relief, showing high interference colors (Figure 2f).

3. Analytical Methods

3.1. Zircon U-Pb Dating

U-Pb dating and trace element analysis of zircons were simultaneously conducted by LA-ICP-MS at the Wuhan SampleSolution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China, following the instrumentation and procedures detailed by Zong et al. (2017) [40]. System: GeolasPro 193 nm laser + Agilent 7900 ICP-MS, using He/Ar as the carrier gas and equipped with a signal-smoothing device. Analyses were performed with a spot size of 32 µm and a repetition rate of 5 Hz. Zircon standard 91500 was used for U-Pb isotopic calibration, and NIST610 glass reference material was employed for trace element calibration [41,42]. Each analysis included 20 to 30 s of background acquisition followed by 50 s of ablation. Offline data processing (signal selection, drift correction, concentration and age calculation) was performed using the software ICPMSDataCal 12.2. Concordia diagrams and weighted mean ages were generated using Isoplot/Ex_ver3 4.15 [43].

Zircon U-Pb isotopic dating and major and trace element analyses for the Muchang granites in this study were carried out simultaneously by LA-ICP-MS at Nanjing Nuokang Testing Technology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) Data acquisition employed a helium carrier gas flow (370 mL/min) mixed with argon, with a single-spot analysis cycle of 60 s (including 20 s of background measurement) and an isotope integration time of 15 to 20 ms. Data reduction was performed using the software ICPMSDataCal for fractionation correction. The common lead correction and age calculations were conducted using the algorithms described [41,42]. Final age uncertainties are quoted at the 2σ level and controlled within ±1 to 2%.

3.2. Whole-Rock Major and Trace Elements Analytical Methods

Whole-rock major elements of the Mengnuo granites were analyzed at Wuhan SampleSolution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd. using a ZSX Primus II wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer (Rigaku Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Detailed analytical procedures, experimental conditions, and estimates of precision and accuracy are provided [44]. Trace elements were determined by ICP-MS using an Agilent 7500 inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer.

Whole-rock major and trace element concentrations of the Muchang granites in this study were analyzed at Nanjing Nuokang Testing Technology Co., Ltd. Major elements were measured using an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (PANalytical Axios mAX, Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands) with an elemental range from Na to U; analytical precision for major elements is better than 0.5% RSD. Samples were prepared as glass beads and pressed powder pellets. The major element analyzer (Agilent 511) covers a wavelength range of 167 to 785 nm with a resolution of ≤0.007 nm at 200 nm. Trace elements were analyzed using an ICP-MS (Thermo iCAP RQ, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a mass range of 2 to 270 amu. Detection limits for most elements are below 1 ppt. The instrument is equipped with a collision/reaction cell (KED mode) and a RESOlution 193 nm excimer laser system.

3.3. Zircon Hf Isotope

The in situ zircon Hf isotopic ratios for the Mengnuo granites were analyzed by laser ablation multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-MC-ICP-MS) at Wuhan SampleSolution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd. To ensure data reliability, three international zircon standards, Plešovice, 91500, and GJ-1, were analyzed together with the actual samples. Detailed instrumental analytical methods can be referred [45].

The in situ zircon Hf isotopic analysis for the Muchang granites in this study were conducted at Nanjing Nuokang Testing Technology Co., Ltd. The laser ablation system used was a RESOlution LR 193 nm excimer laser, coupled with a Nu Plasma II multi-collector ICP-MS. Ablation parameters were set as follows: spot size of 50 μm, repetition rate of 9 Hz, and energy density of 4.5 J/cm2.

4. Data and Results

4.1. Zircon U-Pb Ages

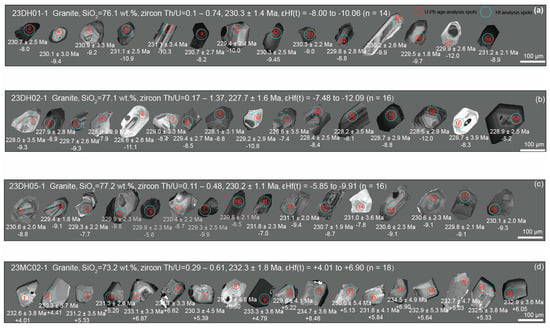

Based on detailed field investigations, three granite samples from the Mengnuo area and one from the Muchang area were selected for zircon U-Pb dating by LA-ICP-MS. The results are presented in Table 1. Most zircons in the samples are euhedral to subhedral, with a few being anhedral, measuring 70–100 μm in length with an aspect ratio of 3:1. Cathodoluminescence (CL) images (Figure 3a–d) reveal that the zircons exhibit well-defined internal structures and typical magmatic oscillatory zoning [46]. Some zircons edges are darker and black, and the middle part is lighter. The Th/U ratios of zircons from the Muchang granites range from 0.29 to 0.61, while those from the Mengnuo area vary between 0.11 and 0.74, except for one grain (sample 23DH01-1) with a Th/U ratio of 0.06. Although Th/U ratios below 0.1 are commonly interpreted as indicative of metamorphic origin [47], this particular zircon displays magmatic oscillatory zoning and yielded a concordant age similar to those of other magmatic zircons. Therefore, the U-Pb ages reported here are interpreted as the crystallization ages of the granites.

Table 1.

LA-ICP-MS zircon U-Pb analysis results of granite samples from Mengnuo and Muchang, Baoshan Terrane.

Figure 3.

Cathodoluminescence (CL) images of the Mengnuo and Muchang granites from the Baoshan Terrane (a–c); CL images of the Muchang granite (d), showing representative zircon grains, U-Pb dating spots (red circles) with corresponding ages, and Hf isotope analysis spots (blue circles) with corresponding results.

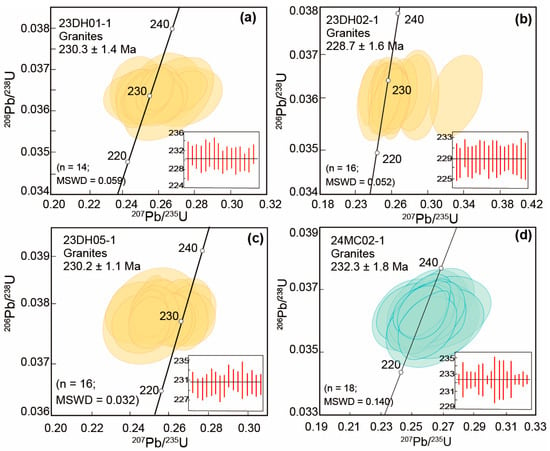

A total of 54 zircon U-Pb ages were obtained from the Mengnuo granite samples in this study (Figure 4a–c). Among them, 14 analytical spots on zircons from sample 23DH01-1 yielded a weighted mean 206Pb/238U age of 230.3 ± 1.4 Ma (n = 16, MSWD = 0.059); 16 spots from sample 23DH02-1 gave a weighted mean 206Pb/238U age of 228.7 ± 1.6 Ma (n = 16, MSWD = 0.052); and 16 spots from sample 23DH05-1 produced a weighted mean 206Pb/238U age of 230.2 ± 1.1 Ma (n = 16, MSWD = 0.320). For the Muchang granite sample 24MC02-1, 18 analytical spots yielded a weighted mean 206Pb/238U age of 232.3 ± 1.8 Ma (n = 18, MSWD = 0.140) (Figure 4d). For sample 23DH01-1, among the 18 zircon grains analyzed, one yielded a significantly younger age, while three yielded significantly older ages. For sample 23DH02-1, out of the 18 zircon grains analyzed, one yielded a younger age and one showed a discordant age. For sample 23DH05-1, two of the 18 zircon grains analyzed yielded older ages (Table 1). In summary, the zircon U-Pb ages of the Mengnuo and Muchang granites reported in this study are approximately 232–229 Ma.

Figure 4.

(a–c) Zircon U-Pb concordia diagrams of the Mengnuo and (d) Muchang granite samples from the Baoshan Terrane.

4.2. Whole-Rock Major and Trace Elements

The whole-rock major and trace element compositions of eight granite samples from the Bangdong pluton in the Mengnuo area and five samples from the Muchang area are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Whole-rock major and trace elements data of granite samples from Mengnuo and Muchang, Baoshan Terrane.

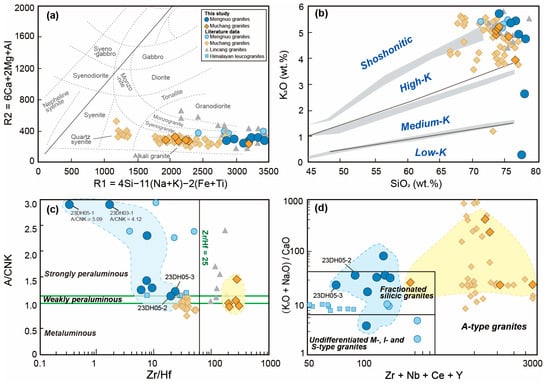

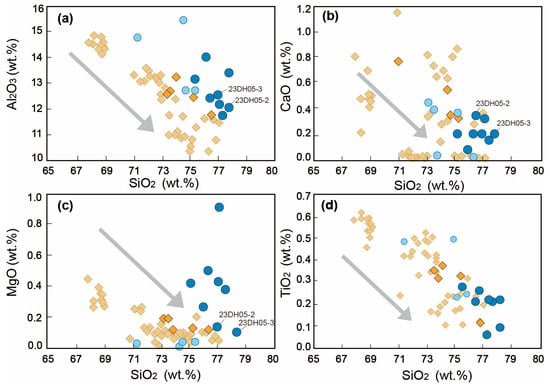

The Mengnuo granites exhibit high silica (SiO2 = 76.07–77.78 wt.%) and high potassium (K2O = 4.74–5.92 wt.%, except for samples 23DH03-1 of 2.57 wt.% and 23DH05-1 of 0.26 wt.%) contents. These samples show consistent major element characteristics, with aluminum saturation index (A/CNK = Al2O3/(CaO + K2O + Na2O)) values ranging from 1.14 to 5.09. The rocks have relatively low loss on ignition (LOI = 0.71 to 2.81), suggesting that they underwent only mild alteration or low-grade metamorphism. The absence of linear correlations between LOI and major oxides, as well as typical trace elements. Furthermore, no correlation is observed between LOI and Eu/Eu*. In the R1–R2 diagram, all samples fall within the alkali-feldspar granite field (Figure 5a). In the SiO2–K2O diagram (Figure 5b), the samples plot within the high-K calc-alkaline series. One sample falls within the medium-K range (23DH03-1; K2O = 2.57 ppm; LOI = 3.23), and one falls within the low-K range (23DH05-1; K2O = 0.26 ppm; LOI = 0.74). Sample 23DH03-1 may have undergone low-grade metamorphism. The granites also exhibit high differentiation index (DI = 74.99 to 94.19) values. The Zr/Hf (0.3 to 6.1) ratios of all samples are less than 25. The Nb/Ta ratio is 4.3 to 44.4. The Mengnuo granite samples exhibit CIA values ranging from 45 to 81, with a mean value of 59 (n = 8). Two samples (DH03-1 = 81; DH05-1 = 78) display significantly higher CIA values. The remaining six samples yield an average CIA value of 52, indicating weak weathering and a composition close to unweathered igneous rock. Samples DH03-1 and DH05-1 may have undergone moderate-intensity weathering. The PIA values of the Mengnuo Granite samples range from 61 to 88, with an average of 68 (n = 8). Among them, two samples, DH03-1 = 82 and DH05-1 = 88, exhibit significantly higher PIA values. The remaining six samples have an average CIA value of 63, suggesting they may have undergone slight alteration. Therefore, it can be concluded that samples DH03-1 and DH05-1 have undergone relatively intense alteration and weathering. The Late Triassic Mengnuo granites from the respective study areas exhibit distinct geochemical characteristics (Figure 6), indicating different petrogenetic origins, magma sources, and fractional crystallization processes.

Figure 5.

(a) R1–R2 [48], (b) SiO2–K2O [49], (c) differentiation index (DI)–A/CNK [50], and (d) Zr + Nb + Ce + Y − (K2O + Na2O)/CaO diagrams of the granites in Mengnuo and Muchang, Baoshan Terrane [51]. Data for the granites from the Baoshan Terrane are from: Kong H L et al., 2012 [52]; Li Q, 2016 [32]; Wang X L et al., 2018 [38]; Wang C B, 2019 [33]. Data for the Himalayan leucogranites are from: Zhang H F et al., 2005 [53]; Liu Z C et al., 2020 [29]; Zhang K et al., 2024 [54]; Shuai et al., 2021 [55].

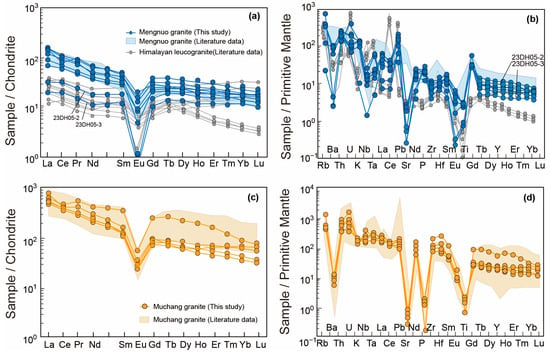

The eight samples from the Mengnuo granites have total rare earth element (REE) contents ranging from 183 ppm to 655 ppm. In the chondrite-normalized REE diagram (Figure 7a), all samples exhibit pronounced negative Eu anomalies and slight enrichment in light REEs (LREEs), with (La/Yb)N values ranging from 1.76 to 11.27. The heavy REE (HREE) patterns are relatively flat, with (Gd/Yb)N values between 0.89 and 2.15. In the primitive mantle-normalized trace element spider diagram (Figure 7b), the samples are enriched in large-ion lithophile elements (LILEs), such as Rb, Th, and U, but show significant depletions in Ba, Nb, and Sr. High field strength elements (HFSEs), including Nd, Ta, Zr, P, and Ti, are depleted. Notably, two samples from the Mengnuo granites (23DH05-2 and 23DH05-3) have lower total REE contents (183–274 ppm). Their chondrite-normalized REE patterns display a distinct “seagull-type” distribution with a strong negative Eu anomaly (Figure 7a). The zircon Hf depleted mantle model ages TDM(Hf) range from 1161 to 1382 Ma, and the crustal model ages TDM(Hf)C range from 1610 to 2016 Ma (Figure 8). On the Zr + Nb + Ce + Y − (K2O + Na2O)/CaO diagram, both samples fall within the field of highly fractionated granites (Figure 5d). The Sm/La ratios of the two samples are 0.3 and 0.39, and the Th/La ratios are 1.9 and 2.1, which likely indicate the presence of a melt-metasomatized source region. The patterns further reveal a significant tetrad effect [56], which is quantitatively confirmed by the TE1,3 values. The parameter TE1,3 was calculated as follows: TE1,3 = [(Ce/Ce* × Pr/Pr)0.5 × (Tb/Tb × Dy/Dy*)0.5]. The obtained TE1,3 values range from 1.20 to 1.21. According to the criterion proposed by [57] (TE1,3 > 1.1), these results are consistent with the presence of a tetrad effect. This study adopts the widely applied formula introduced by [57] for this assessment.

The Muchang granite samples exhibit high SiO2 contents (73.26–76.41 wt.%) and elevated K2O values (3.92–5.22 wt.%). In the R1–R2 diagram, all samples fall within the alkali-feldspar granite field (Figure 5a). In the SiO2–K2O diagram (Figure 5b), the samples classify as high-K calc-alkaline rocks. All samples display very low MnO (0.01–0.14 wt.%) and P2O5 (0.003–0.030 wt.%) contents. The aluminum saturation index (A/CNK = Al2O3/(CaO + K2O + Na2O) molar ratio ranges from 0.92 to 1.06, except for sample 24MC04-1 of 1.46. In the Zr/Hf–(A/CNK) diagram (Figure 5c), most samples are weakly peraluminous, indicating metaluminous to slightly peraluminous characteristics.

The Muchang granites show high total rare earth element (REE) contents, ranging from 558 to 3607 ppm. On the chondrite-normalized REE diagram (Figure 7c), the samples exhibit moderately negative Eu anomalies and slight enrichment in light REEs (LREEs), with (La/Yb)N values between 2.78 and 11.82 (N value represents the normalized value of relative chondrites). The HREE patterns are relatively flat, as indicated by (Gd/Yb)N values of 1.13–2.86. In the primitive mantle-normalized trace element spider diagram (Figure 7d), the samples are enriched in large-ion lithophile elements (LILEs) such as Rb, K, Th, and U, and significantly enriched in high field strength elements (HFSEs).

Figure 6.

Whole-rock Harker diagrams for the Mengnuo granites (a–d) and Whole-rock Harker diagrams for the Muchang granites (a–d) from the Baoshan Terrane. Data sources are the same as those for Figure 5.

Figure 7.

Chondrite-normalized REE and primitive-mantle-normalized trace element pattern diagrams of the granites from (a,b) Mengnuo and (c,d) Muchang, Baoshan Terrane. Both chondrite-normalized values and primitive mantle-normalized values are based on Sun and McDonough (1989) [58]. Data sources are the same as those for Figure 5.

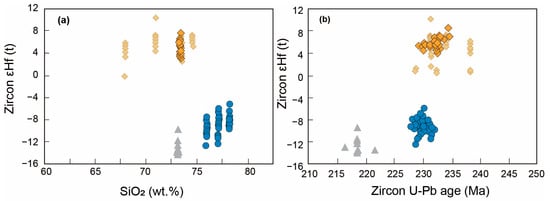

Figure 8.

(a) Plots of zircon εHf(t) vs. SiO2 and (b) zircon U-Pb ages of the Mengnuo and Muchang granites from the Baoshan Terrane. Data sources are the same as those for Figure 5.

4.3. Zircon Hf Isotopic Characteristics

Zircon Hf isotopic analyses were conducted on four samples in this study, and the results are presented in Table 3. The three Mengnuo granite samples show 176Yb/177Hf and 176Lu/177Hf ratios ranging from 0.0458 to 0.1807 and 0.0012 to 0.0045, respectively. Almost all 176Lu/177Hf ratios are lower than 0.002, indicating limited accumulation of radiogenic Hf after zircon crystallization. Therefore, the initial 176Hf/177Hf ratios can be used to represent the Hf isotopic composition at the time of zircon formation [59]. The average fLu/Hf values of the samples range from −0.86 to −0.97, which are significantly lower than those of mafic crust (−0.34; [60]) and felsic crust (−0.72; [61]). Thus, the two-stage Hf model ages are considered more representative of the timing of crustal extraction from the depleted mantle. The εHf(t) values vary between −6.76 to −12.32. The zircon Hf depleted mantle model ages TDM(Hf) range from 1161 to 1382 Ma, and the crustal model ages TDM(Hf)C range from 1610 to 2016 Ma (Figure 8).

Table 3.

Zircon Hf isotope data of granite samples from Mengnuo and Muchang in Baoshan Terrane.

For the single Muchang granite sample, zircon 176Yb/177Hf ratios range from 0.03628 to 0.16800, and 176Lu/177Hf ratios vary between 0.0009168 and 0.002505. The initial 176Hf/177Hf ratios are between 0.282763 and 0.282887, with εHf(t) values ranging from 4.01 to 8.46. The corresponding depleted mantle model ages TDM(Hf) are 592 to 722 Ma, and the crustal model ages TDM(Hf)C range from 700 to 956 Ma (Figure 8).

5. Discussion

5.1. Regional Late Triassic Felsic Magmatism

The Changning–Menglian suture zone is considered to record the subduction and closure of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean, followed by continental accretion and collisional orogenesis [62]. Late Triassic magmatism has been identified on both sides of this suture zone [63]. The eastern side of the Changning–Menglian suture, which was an active continental margin during subduction and the upper plate during collision, exhibits large-scale magmatism represented by the Lincang granite batholith [52]. The Lincang batholith trends approximately north–south, with an outcrop area of about 7400 km2 [64]. It is composed mainly of granodiorites and monzogranites (Figure 5; [52,65,66,67,68]). The batholith formed between the Permian and Jurassic (288 to 138 Ma), with a peak magmatic phase during the Middle to Late Triassic [52,69,70]. The northern part of the Lincang batholith intrudes the Triassic Manghuai Formation volcanic rocks. These volcanic rocks, which are contemporaneous with the batholith, formed from the late Middle Triassic to Late Triassic and consist predominantly of rhyolites with minor basalts [71].

On the western side of the Changning–Menglian suture zone, the Baoshan Terrane, which was a passive continental margin during subduction and the lower plate during collision, exhibits relatively weak magmatic activity. This study obtained LA-ICP-MS zircon U-Pb ages of 230.3 ± 1.4 Ma, 228.7 ± 1.6 Ma, and 230.2 ± 1.1 Ma from three Mengnuo granite samples. Although field and microscopic observations indicate mylonitization in these samples, the high closure temperature of the U-Pb system in zircon (ca. 900 °C; [72]) exceeds that of mylonitization (500 to 700 °C; [73]). Therefore, the ages obtained herein are interpreted to represent the crystallization age of the Mengnuo granites at 230 to 229 Ma. This result is consistent with previously reported granites ages from the Mengnuo area (228 Ma; [38]). Late Triassic magmatic rocks in the southern Baoshan Terrane, including the Muchang granites and the Niuhetang Formation volcanic rocks, are exposed in the Muchang and Zhenkang areas [32,33]. One Muchang granite sample from this study yielded a zircon U-Pb age of 232.3 ± 1.8 Ma, consistent with previously published ages (238.1 to 228.8 Ma; [32,33]). The Niuhetang Formation volcanic rocks, consisting mainly of basalts, andesites, and rhyolites, also formed during the Late Triassic (our unpublished data). Therefore, the geochronological results from this study, combined with regional data, indicate that the Late Triassic magmatism in the Baoshan Terrane occurred at approximately 230 Ma.

5.2. Petrogenesis of the Late Triassic Granites in the Baoshan Terrane

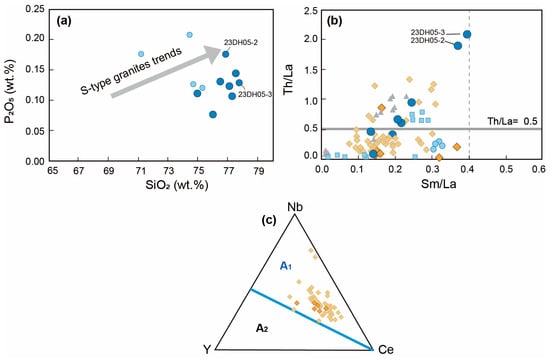

The Late Triassic Mengnuo and Muchang granites from the respective study areas exhibit distinct geochemical characteristics (Figure 6), indicating different petrogenetic origins, magma sources, and fractional crystallization processes. The Mengnuo felsic granites are characterized by high SiO2 (76.07 to 77.78 wt.%), low MgO (0.07 to 0.90 wt.%) (Figure 5b), high A/CNK ratios (1.14 to 5.09), and variable but elevated Differentiation Index (DI = 74.99 to 94.19), classifying them as strongly peraluminous, highly fractionated granites (Figure 5c). In contrast, the Muchang granites also show high SiO2 (73.26 to 76.41 wt.%) and total alkalis (Na2O + K2O = 6.23 to 9.53 wt.%), but the majority exhibit lower A/CNK ratios (<1.1) as well as elevated values of Zr + Nb + Ce + Y. They plot within the field of A-type granites and are classified as weakly aluminous A-type granites (Figure 5d).

5.2.1. Mengnuo Granites: Highly Fractionated S-Type Granites

Although some Mengnuo granite samples exhibit variable and relatively low DI values (75–94), conventional geochemical indicators for highly fractionated granites (e.g., SiO2, MgO, Mg#, and DI) can be ambiguous [65]. To circumvent this limitation, we utilized the more robust whole-rock Zr/Hf and Nb/Ta ratios, which are effective proxies for the degree of granite fractionation. The Mengnuo samples are characterized by low Zr/Hf (0.3–6.1) and Nb/Ta (4.3–44.4) ratios (Figure 5c and Figure 10b), and therefore considered to be highly fractionated granites. It is challenging to discriminate the genetic types of highly fractionated I, S, and A-type granites, as they all evolve into eutectic granites with similar mineral assemblages and geochemical characteristics [59]. Based on the following evidence, this study suggests that the Bangdong pluton granite in the Mengnuo area belongs to highly fractionated S-type granites:

- (1)

- Although the Mengnuo granite samples fall within the A-type granite field in the Zr + Nb + Ce + Y − (K2O + Na2O)/CaO diagram (Figure 5d), their low Zr + Nb + Ce + Y values and high Differentiation Index (DI = 74.99–94.19) preclude their classification as A-type granites.

- (2)

- The P2O5 content in granites is primarily controlled by the fractional crystallization of apatite, which behaves differently in I-type and S-type granites [74,75]. The P2O5 content of the Mengnuo granites increases with increasing SiO2 (Figure 9a), consistent with the evolutionary trend of S-type granites.

- (3)

- Whole-rock zircon saturation temperature calculations [76] indicate that the Mengnuo granites in this study crystallized at relatively low magma temperatures (approximately 519 to 627 °C), consistent with the typical characteristic of S-type granites (TZr < 750 °C; [77]). Furthermore, the presence of inherited zircons with ages of 310–239 Ma in samples 23DH01-1, 23DH02-1, and 23DH05-1 (Table 1) provide additional evidence for their formation at relatively low temperatures.

- (4)

- The Mengnuo granites exhibit high A/CNK ratios (1.14 to 5.09), classifying them as strongly peraluminous (Figure 5c), and exhibits low Sm/La ratios (0.14 to 0.39), reflecting possible modification of the source region by fluids, which indicates a (meta) sedimentary rock source (Figure 9b). Therefore, the Mengnuo granites are interpreted as highly fractionated S-type granites.

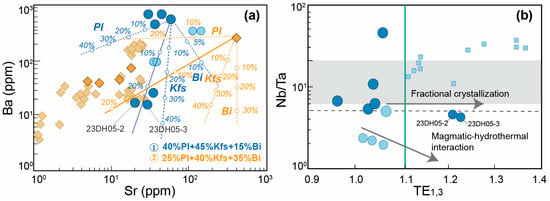

The Mengnuo granites exhibit high SiO2 content and high Differentiation Index (DI = 74.99 to 94.19). In the Harker diagrams, Al2O3, MgO, CaO, and TiO2 show negative correlations with SiO2 (Figure 6a–d), along with pronounced negative anomalies in Ba, Rb, Sr, Eu, and Ti (Figure 7b). These features indicate that the magma underwent extensive fractional crystallization of minerals such as plagioclase, K-feldspar, and biotite. Quantitative modelling results demonstrate that the compositions of Ba, Rb, and Sr in the most fractionated sample (23DH02-2; SiO2 = 76.47 wt.%, DI = 89.98) can be reproduced by approximately 20% fractional crystallization of a mineral assemblage consisting of 40% plagioclase, 45% K-feldspar, and 15% biotite from a less evolved sample (23DH04-1; SiO2 = 75.15 wt.%) (Figure 10a).

Figure 9.

Plots of (a) SiO2–P2O5 diagram [78], (b) Sm/La–Th/La and (c) Nb–Y–Ce of the Mengnuo and Muchang granites from the Baoshan Terrane [79]. Data sources are the same as those for Figure 5.

Figure 10.

Plots of (a) Sr–Ba and (b) TE1,3–Nb/Ta of the Mengnuo and Muchang granites from the Baoshan Terrane. Data sources are the same as those for Figure 5.

Notably, two samples (23DH05-2 and 23DH05-3) from the Mengnuo granites exhibit a “seagull-type” REE pattern with TE1,3 values greater than 1.1 (Figure 10b), indicating a distinct rare earth element tetrad effect. The tetrad effect in REE is generally attributed to two genetic mechanisms: magma-fluid interaction [80] and fractional crystallization [53]. Although the Mengnuo granites show some degree of twin element fractionation (e.g., Nb/Ta and Zr/Hf), a coupling often interpreted as evidence of element migration through melt, fluid interaction [53,54,55,57,80,81], the ubiquitous twin element fractionation in these rocks and their contrasting geochemical features compared to tetrad-bearing leucogranites formed by melt–fluid interaction in the Himalayas (Figure 7; [29,53,54]) suggest that the tetrad effect in the studied samples is unlikely to result from fluid-related processes. The two samples displaying the tetrad effect possess the highest SiO2 contents and differentiation indices, which align with the fractional crystallization simulation mentioned earlier. They also exhibit lower Nb/Ta and Zr/Hf ratios, implying fractional crystallization of accessory minerals that controlled the REE behavior. Therefore, the tetrad effect in the Mengnuo granites are more likely the result of extensive fractional crystallization.

In conclusion, the Mengnuo granites are S-type granites derived from partial melting of ancient crustal materials, and its REE tetrad effect may be attributed to fractional crystallization processes.

5.2.2. Muchang Granites: A-Type Granites

The Muchang granite samples are characterized by high silica (SiO2 = 73.26 to 76.41 wt.%) and high alkali (K2O + Na2O = 6.23 to 9.53 wt.%) contents, belonging to the high-K calc-alkaline series. Most samples exhibit low aluminum saturation index (A/CNK = 0.92 to 1.46) values, classifying them as metaluminous to weakly peraluminous (Figure 5c). Only one sample (24MC04-1; A/CNK = 1.46) is strongly peraluminous. Petrographic observations reveal the presence of mafic minerals and zircon grains (Figure 2e,f). The granites also show high concentrations of high field strength elements (HFSEs; Zr + Nb + Ce + Y = 313.73 to 3000.36 ppm), high FeO*/MgO ratios (13.31 to 24.14), and high whole-rock zircon saturation temperatures (∼970 °C). Therefore, the Muchang granites are classified as A-type granites.

A-type granites can be further classified into A1 and A2 subtypes based on their distinct geochemical characteristics [81]. A1-type granites exhibit incompatible element ratios similar to those of OIB (ocean island basalt), indicating the involvement of mantle-derived materials in their magma sources. whereas A2-type granites are primarily derived from crustal sources [82]. In the Nb–Y–Ce ternary diagram, all samples in this study plot within the A1 field (Figure 8), confirming their classification as A1-type granites. Furthermore, the Muchang granites exhibits depleted zircon Hf isotopic compositions, with εHf(t) values ranging from +4.01 to +8.46, suggesting the involvement of mantle-derived material in their magma sources. It is noteworthy that the Muchang granite samples have high SiO2 contents and high Differentiation Index (DI = 81.70–95.96). In Harker diagrams, Al2O3, CaO, MgO, and TiO2 show negative correlations with SiO2 (Figure 6a–d). Additionally, pronounced negative Eu anomalies and depletions in Ba, Sr, P, and Ti (Figure 7d) indicate significant fractional crystallization of biotite, K-feldspar, and plagioclase. Quantitative fractional crystallization modelling suggests that the granite underwent approximately 20% crystallization of a mineral assemblage consisting of 25% plagioclase, 40% K-feldspar, and 35% biotite (Figure 10a).

In conclusion, the A1-type Muchang granites were likely derived from a magma source containing mantle-derived components and subsequently experienced extensive fractional crystallization.

5.3. Geodynamical Interpretation

In recent years, numerous studies have identified and confirmed the presence of high-pressure glaucophane schists, ophiolitic belts, and metamorphic zones along the Changning–Menglian suture zone, providing evidence for the opening, subduction, and continent–continent or arc–continent collision of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean by the end of the late Paleozoic. However, the timing of the collision remains debated across different disciplines, with key evidence including: (1) Discontinuous lithostratigraphic sequences in the Lower Triassic and a transition from marine to continental facies, indicating that the final closure of the oceanic basin and the orogenic phase occurred between the end of the Triassic and the beginning of the Jurassic [21]; (2) Paleomagnetic studies of the Lancangjiang volcanic belt suggesting that the closure of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean occurred no later than the Carnian stage of the Late Triassic (235–230 Ma; [83]); (3) Retrograde eclogites dated to approximately 245 to 228 Ma, representing events from subduction to collision of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean [23,25,26]; (4) Metamorphic zircon rims in eclogites yielding U-Pb ages of 234 to 233 Ma, interpreted as the timing of the onset of continental subduction [27]. Wang Y. et al. (2018) [24] synthesized regional geological evidence and proposed that the initial collision between the Sibumasu Terrane and the western margin of the Indochina Terrane occurred at approximately 237 Ma, with syn-collision and post-collision stages spanning ca. 237 to 230 Ma and ca. 230 to 200 Ma, respectively. Combined with the zircon U-Pb ages of 230 Ma obtained in this study and previous works in the Mengnuo and Muchang areas of the Baoshan Terrane, both granite types investigated here are interpreted as syn-collisional granites.

The strongly peraluminous S-type Mengnuo granites in this study exhibits enriched zircon Hf isotopic compositions and originated from partial melting of ancient crustal materials. In contrast, the Muchang A-type granites show relatively depleted zircon Hf isotopes and geochemical characteristics typical of A-type granites, suggesting the involvement of mantle-derived components in their magma sources and formation in an extensional setting [84]. Additionally, contemporaneous volcanic rocks of the Niuhetang Formation include intraplate-type basalts and high-K calc-alkaline intermediate to felsic rocks [30]. Integrating these findings with regional geological data, we propose that the Late Triassic magmatism in the Baoshan Terrane likely developed in a syn-collisional tectonic setting associated with slab break-off. Numerical modeling results [85] indicate that slab break-off is a common phenomenon in collisional orogens [9]. Moreover, melting of the asthenosphere and metasomatized lithospheric mantle triggered by slab break-off may persist for several million years, with the duration primarily controlled by convergence rate, lithospheric thickness, age of the subducted slab, and subduction angle [15,85,86]. In summary, the coeval occurrence of S-type and A-type felsic rocks along with intraplate basalts during the Late Triassic in the Baoshan Terrane suggests that syn-collisional magmatism may be associated with upwelling of asthenospheric material due to slab break-off, triggering melting of both mantle and crustal sources. However, this interpretation requires further support from evidence such as studies on mafic rocks and magmatic migration patterns [87,88].

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The Mengnuo and Muchang granites were emplaced at approximately 230.3 to 228.7 Ma and 232.3 Ma, respectively. These ages are consistent with the closure of the Changning–Menglian Paleo-Tethys Ocean, indicating their origin as syn-collisional granites.

- (2)

- Whole-rock geochemical and zircon Hf isotopic data indicate that the Mengnuo granites are strongly peraluminous S-type granites, whereas the Muchang granites are weakly aluminous A-type granites.

- (3)

- The Mengnuo granites were likely derived from partial melting of ancient crustal materials, and underwent fractional crystallization dominated by a mineral assemblage comprising K-feldspar, plagioclase, and biotite. The distinctive rare earth element tetrad effect observed in these samples is likewise attributed to fractional crystallization processes. The Muchang granites are classified as A1-type granites and display depleted zircon Hf isotopic compositions, indicating the incorporation of mantle-derived components in their magma sources, followed by subsequent fractional crystallization processes.

- (4)

- Integrated with regional studies, the Late Triassic syn-collisional magmatism in the Baoshan Terrane was likely related to break-off of the subducted slab.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L., B.Y., P.W. and Z.J.; methodology, A.L.; field sampling, B.Y., A.L., Z.J. and Z.L.; validation, B.Y. and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work financially co-supported by the Major Program of Basic Research Planning of Yunnan Province (202401BC070019), the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (42102047), the Applied Basic Research Projects of Yunnan Province (202401CF070095), the Special Project for High-level Scientific and Technological Talents and Innovation Team Selection of the Department of Science and Technology of Yunnan Province (202305AT350004), and the Key Scientific and Technological Special Project of the Department of Science and Technology of Yunnan Province (202202AG050006), Scientific Research Foundation Project of Kunming University of Science and Technology (KKZ3202421132).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dicheng Zhu, Qing Wang, and the expert reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions on this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Von Blanckenburg, F.; Davies, J.H. Slab breakoff: A model for syncollisional magmatism and tectonics in the Alps. Tectonics 1995, 14, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.L.; Chu, M.F.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Lo, C.H.; Lee, T.Y.; Lan, C.Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Tibetan tectonic evolution inferred from spatial and temporal variations in post-collisional magmatism. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2005, 68, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.L.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, D.C.; Zhao, Z.D.; Liu, S.A.; Wang, R.; Dai, J.G.; Zheng, Y.C.; Zhang, L.L. Origin of the ca. 50 Ma Linzizong shoshonitic volcanic rocks in the eastern Gangdese arc, southern Tibet. Lithos 2018, 304–307, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, H.; Palin, R.M.; Dong, X.; Tian, Z.; Chen, Y. The lower crust of the Gangdese magmatic arc, southern Tibet, implication for the growth of continental crust. Gondwana Res. 2020, 77, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Gao, P. The production of granitic magmas through crustal anatexis at convergent plate boundaries. Lithos 2021, 402–403, 106232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.K.; Zhu, D.C.; Weinberg, R.F.; Wang, Q.; Xie, J.C.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhao, Z.D. Origin of Tibetan post–collisional high–K adakitic granites: Anatexis of intermediate to felsic arc rocks. Geology 2022, 50, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.L.; Zhao, Z.F.; Dai, L.Q. Post-collisional mafic magmatism: Material records of lithospheric mantle evolution in continental orogenic belts. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 1906–1918, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Chen, Y.X.; Chen, R.X.; Dai, L.Q. Tectonic evolution of convergent plate margins and its geological effects. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2022, 52, 1213–1242, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.C.; Wang, Q.; Li, S.M.; Zhan, Q.Y.; Liu, Z.; Xie, J.C.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhong, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.X. Magmatic origin and crustal evolution in continental collision zones. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2025, 55, 1398–1423, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Cui, F.Y.; Yang, S.T.; Zhong, X.Y. Key dynamic processes and driving forces of Tethyan evolution. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 53, 2701–2722, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Song, S. Post-collision magmatism and continental crust growth in continental orogenic belt: An example from North Qaidam ultrahigh–pressure metamorphic belt. Earth Sci. 2023, 48, 4481–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liegeois, J.P.; Navez, J.; Hertogen, J.; Black, R. Contrasting origin of post–collisional high-K calc–alkaline and shoshonitic versus alkaline and peralkaline granitoids. The use of sliding normalization. Lithos 1998, 45, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.X.; Zhao, Z.D.; Zhou, S.; Dong, G.C.; Liao, Z.L. Timing of the India–Asia continental collision. Geol. Bull. China 2007, 26, 1240–1244, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Maksatbek, S.; Cai, F.L.; Wang, H.Q.; Song, P.P.; Ji, W.Q.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.Y.; Muhammad, Q.; Upendra, B. Timing and closure process of the initial collision between India and Eurasia. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2017, 47, 293–309, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.D. Methods and examples for quantitatively constraining the timing and process of continent-continent collision using magmatic rocks. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2017, 47, 657–673, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Gao, L.E.; Xie, K.; Liu, Z.J. Mid–Eocene high Sr/Y granites in the Northern Himalayan Gneiss Domes: Melting thickened lower continental crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 303, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.Q.; Zheng, Y.C.; Zeng, L.S.; Gao, L.E.; Huang, K.X.; Li, W.; Li, Q.Y.; Fu, Q.; Liang, W.; Sun, Q.Z. Eocene–Oligocene granitoids in southern Tibet: Constraints on crustal anatexis and tectonic evolution of the Himalayan orogen. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 349–350, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.Q.; Wu, F.Y.; Chung, S.L.; Wang, X.C.; Liu, C.Z.; Li, Q.L.; Liu, Z.C.; Liu, X.C.; Wang, J.G. Eocene Neo–Tethyan slab breakoff constrained by 45 Ma oceanic island basalt–type magmatism in southern Tibet. Geology 2016, 44, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, Q.; Kerr, A.C.; Li, Z.X.; Dan, W.; Yang, Y.N.; Zhou, J.S.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Eocene magmatism in the Himalaya: Response to lithospheric flexure during early Indian collision? Geology 2023, 51, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.T.; Xu, Q.; Wang, L.Q. Mechanism of the multi-island arc-basin system pattern in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Mineral. Petrol. 2001, 21, 186–189, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Pan, G.T.; Wang, L.Q.; Geng, Q.R.; Yin, F.G.; Wang, B.D.; Wang, D.B.; Peng, Z.M.; Ren, F. Spatio-temporal framework of the Bangong Co–Shuanghu–Nujiang–Changning–Menglian Suture Zone: Issues on Tethyan oceanic geology and evolution. Sediment. Geol. Tethyan Geol. 2020, 40, 1–19, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.P.; Feng, Q.L.; Fang, N.Q.; Jia, J.H.; He, F.X. Paleo-Tethyan poly-island ocean tectonic evolution of the Changning-Menglian and Lancangjiang belts, southwestern Yunnan. Earth Sci. 1993, 529–539+671, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jourdan, F.; Zi, J.; Liu, H. Paleotethyan subduction process revealed from Triassic blueschists in the Lancang tectonic belt of Southwest China. Tectonophysics 2015, 662, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, X.; Cawood, P.A.; Liu, H.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, Y.; He, H.; Zhang, P. Closure of the East Paleotethyan Ocean and amalgamation of the Eastern Cimmerian and Southeast Asia continental fragments. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 186, 195–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, F.; Schertl, H.P.; Liu, P.; Ji, L.; Cai, J.; Liu, L. Paleo–Tethyan tectonic evolution of Lancangjiang metamorphic complex: Evidence from SHRIMP U-Pb zircon dating and 40Ar/39Ar isotope geochronology of blueschists in Xiaoheijiang–Xiayun area, Southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Gondwana Res. 2019, 65, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.N.; Liu, F.L.; Sun, Z.B.; Ji, L.; Zhu, J.J.; Cai, J.; Zhou, K.; Li, J. A New HP-UHP Eclogite Belt Identified in the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau: Tracing the Extension of the Main Palaeo–Tethys Suture Zone. J. Petrol. 2020, 61, egaa073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Lanari, P.; Wu, F.Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Khanal, G.P.; Yang, L. First evidence of eclogites overprinted by ultrahigh temperature metamorphism in Everest East, Himalaya: Implications for collisional tectonics on early Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2021, 558, 116760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Wang, C. Tethys tectonic evolution and its bearing on the distribution of important mineral deposits in the Sanjiang region, SW China. Gondwana Res. 2014, 26, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.C.; Wu, F.Y.; Liu, X.C.; Wang, J.G. An overview of fractional crystallization processes in Himalayan leucogranites. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2020, 36, 3551–3571, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Q.H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhu, W.M.; Xu, G.X.; Qi, R.H. Regional geochemical characteristics and prospecting direction in Zhenkang area, Yunnan Province. J. Geol. 2016, 40, 23–30, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.M. Genetic Mechanisms of Late Triassic to Early Eocene Magmatic Rocks in the Tengchong Block. Ph.D. Dissertation, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Zircon Dating, Geochemistry, Tectonic Setting and Prospecting Significance of the Muchang Granite in Zhenkang, Yunnan. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.B. Petrogenesis of the Muchang Alkaline Granite in the Baoshan Block, Southwestern Sanjiang Region; China University of Geosciences: Beijing, China, 2019; (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Mo, X.X.; Deng, J.F.; Dong, F.L.; Yu, X.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yang, W.G. Volcanic-tectonic assemblages in the Sanjiang orogenic belt, southwestern China and their implications. J. High. Educ. Geol. 2001, 7, 121–138, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, I. Tectonic framework and Phanerozoic evolution of Sundaland. Gondwana Res. 2011, 19, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, I. Gondwana dispersion and Asian accretion: Tectonic and palaeogeographic evolution of eastern Tethys. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 66, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, C.; Bagas, L.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Lu, Y. Cretaceous–Cenozoic tectonic history of the Jiaojia Fault and gold mineralization in the Jiaodong Peninsula, China: Constraints from zircon U-Pb, illite K-Ar, and apatite fission track thermochronometry. Miner. Depos. 2015, 50, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Li, W.K.; Huang, L.; Song, D.H.; Yan, H.B.; Lu, X.P. LA-ICP-MS zircon U-Pb dating, geochemistry and tectonic significance of the Triassic Bengdong granite pluton in the Longling area, western Yunnan. Geol. Bull. China 2018, 37, 2071–2078, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.Q.; Qian, T.H.; Ye, Z.S.; Yan, Y.B. Petrological and geochemical characteristics of the A-type granite in Muchang, Zhenkang, western Yunnan. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 1988, 7, 38–48, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zong, K.Q.; Klemd, R.; Yuan, Y.; He, Z.Y.; Guo, J.L.; Shi, X.L.; Liu, Y.S.; Hu, Z.C.; Zhang, Z.M. The assembly of Rodinia: The correlation of early Neoproterozoic (ca. 900 Ma) high-grade metamorphism and continental arc formation in the southern Beishan Orogen, southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB). Precambrian Res. 2017, 290, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Gao, S.; Günther, D.; Xu, J.; Gao, C.; Chen, H. In situ analysis of major and trace elements of anhydrous minerals by LA-ICP-MS without applying an internal standard. Chem. Geol. 2008, 257, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, S.; Hu, Z.; Gao, C.; Zong, K.; Wang, D. Continental and Oceanic Crust Recycling-induced Melt–Peridotite Interactions in the Trans–North China Orogen: U-Pb Dating, Hf Isotopes and Trace Elements in Zircons from Mantle Xenoliths. J. Petrol. 2010, 51, 537–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. Isoplot 3.00: A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel; Berkeley Geochronology Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.Y.; Chung, S.L.; Ji, J.; Qian, Q.; Gallet, S.; Lo, C.H.; Lee, T.Y.; Zhang, Q. Geochemical and Sr-Nd isotopic constraints on the genesis of the Cenozoic Linzizong volcanic successions, southern Tibet. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 53, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Tong, X.; Lin, L.; Zong, K.; Li, M.; Chen, H. Improved in situ Hf isotope ratio analysis of zircon using newly designed X skimmer cone and jet sample cone in combination with the addition of nitrogen by laser ablation multiple collector ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2012, 27, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.B.; Zheng, Y.F. Genesis of zircon and its constraints on interpretation of U-Pb age. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2004, 49, 1589–1604, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubatto, D.; Hermann, J. Zircon Behaviour in Deeply Subducted Rocks. Elements 2007, 3, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Roche, H.; Leterrier, J.; Grandclaude, P.; Marchal, M. A classification of volcanic and plutonic rocks using R1R2-diagram and major-element analyses—Its relationships with current nomenclature. Chem. Geol. 1980, 29, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollinson, H.R. Using Geochemical Data: Evaluation, Presentation, Interpretation; Burnt Mill Academy: Harlow, UK; Longman Scientific: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.Y.; Liu, X.C.; Ji, W.Q.; Wang, J.M.; Yang, L. Identification and research of highly fractionated granites. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2017, 47, 745–765, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Whalen, J.B.; Currie, K.L.; Chappell, B.W. A-type granites: Geochemical characteristics, discrimination and petrogenesis. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1987, 95, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.L.; Dong, G.C.; Mo, X.X.; Zhao, Z.D.; Zhu, D.C.; Wang, S.; Li, R.; Wang, Q.L. Petrogenesis of the Lincang granite in western Yunnan Sanjiang region: Constraints from geochemistry, zircon U-Pb geochronology and Hf isotopes. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2012, 28, 1438–1452, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.F.; Harris, N.; Parrish, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.D.; Li, D.W. Geochemistry of North Himalayan leucogranites: Regional comparison, petrogenesis and tectonic implications. Earth Sci.-J. China Univ. Geosci. 2005, 30, 275–288, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; Zhao, K.D.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.R.; Zhang, X.F.; Zou, H.; Cao, H.W. Elemental and boron isotopic variations in tourmaline from the Miocene Kuju leucogranite-pegmatite in the eastern Himalaya: Insights into magmatic melt evolution. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2024, 40, 2334–2352, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Shuai, X.; Li, S.M.; Zhu, D.C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhao, Z. Tetrad effect of rare earth elements caused by fractional crystallization in high–silica granites: An example from central Tibet. Lithos 2021, 384, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.; Kawakami, O.; Dohmoto, Y.; Takenaka, T. Lanthanide tetrad effects in nature: Two mutually opposite types, W and M. Geochem. J. 1987, 21, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irber, W. The lanthanide tetrad effect and its correlation with K/Rb, Eu/Eu∗, Sr/Eu, Y/Ho, and Zr/Hf of evolving peraluminous granite suites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1989, 42, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Li, X.H.; Zheng, Y.F.; Gao, S. Lu-Hf isotopic systematics and their applications in petrology. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2007, 23, 185–220, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelin, Y.; Lee, D.C.; Halliday, A.N. Early-middle archaean crustal evolution deduced from Lu-Hf and U-Pb isotopic studies of single zircon grains. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2000, 64, 4205–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, J.D.; Patchett, P.J.; Gehrels, G.E.; Nutman, A.P. Constraints on early Earth differentiation from hafnium and neodymium isotopes. Nature 1996, 379, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.D.; Wang, L.Q.; Wang, D.B.; Yin, F.G.; He, J.; Peng, Z.M.; Yan, G.C. Tectonic Evolution of the Changning–Menglian Proto-Paleo Tethys Ocean in the Sanjiang Area, Southwestern China. Earth Sci. 2018, 43, 2527–2550, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.Y.; Liu, D.; Jian, P.; Qian, Q.; Zhou, G.; Robinson, P.T. A brief review of ophiolites in China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2008, 32, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, D.; Lehmann, B.; Frei, D.; Belyatsky, B.; Zhao, X.F.; Cabral, A.R.; Zeng, P.S.; Zhou, M.F.; Schmidt, K. Early Permian seafloor to continental arc magmatism in the eastern Paleo–Tethys: U-Pb age and Nd-Sr isotope data from the southern Lancangjiang zone, Yunnan, China. Lithos 2009, 113, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Mo, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, D.; Goodman, R.C.; Kong, H.; Wang, S. Zircon U-Pb dating and the petrological and geochemical constraints on Lincang granite in Western Yunnan, China: Implications for the closure of the Paleo–Tethys Ocean. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 62, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.Y.; Yin, F.G.; Wang, D.B.; Tang, Y.; Sun, Z.M.; Sun, J. Discovery of Middle Triassic alkali-feldspar granite in the Lincang batholith, “Sanjiang” area, western Yunnan and its significance. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2014, 33, 1–12, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, F.L.; Liu, P.H.; Shi, J.R.; Cai, J. Zircon U-Pb dating of the Lincang granite in the southern Lancangjiang zone and its tectonic significance. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2014, 30, 3034–3050, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Wang, C.; Zi, J.W.; Xia, R.; Li, Q. Constraining subduction-collision processes of the Paleo-Tethys along the Changning–Menglian Suture: New zircon U-Pb ages and Sr-Nd-Pb-Hf-O isotopes of the Lincang Batholith. Gondwana Res. 2018, 62, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.X. Volcanic Rocks–Ophiolites and Mineralization in the Middle-Southern Segment of the Sanjiang Region; Geological Publishing Houses: Beijing, China, 1988; (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, K. Geochemical characteristics of Triassic granites in the Lincang granite belt and rare, rare earth and rare-scattered metals mineralization. Resour. Environ. Eng. 2020, 34 (Suppl. S2), 1–7+66, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q.; Shen, S.; Liu, B.; Helmcke, D.; Qian, X.; Zhang, W. Permian radiolarians, chert and basalt from the Daxinshan Formation in Lancangjiang belt of southwestern Yunnan, China. Sci. China Ser. D: Earth Sci. 2002, 45, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskin, P.W.O.; Schaltegger, U. The Composition of Zircon and Igneous and Metamorphic Petrogenesis. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003, 53, 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.B.; Wang, B.D.; Tang, Y.; Luo, L.; He, J.; Jiang, L.L.; Zhao, H.S.; Chen, L. Research progress and prospects of the Sanjiang Tethys in Southwest China. Geol. Bull. China 2021, 40, 1799–1813, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Jahn, B.M.; Wilde, S.A.; Lo, C.H.; Yui, T.F.; Lin, Q.; Ge, W.C.; Sun, D.Y. Highly fractionated I-type granites in NE china (I): Geochronology and petrogenesis. Lithos 2003, 66, 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Li, X.H. Formation of the 1300 km–wide intracontinental orogen and postorogenic magmatic province in Mesozoic South China: A flat–slab subduction model. Geology 2007, 35, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.B.; Harrison, T.M. Zircon saturation revisited: Temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1983, 64, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.F.; McDowell, S.M.; Mapes, R.W. Hot and cold granites? Implications of zircon saturation temperatures and preservation of inheritance. Geology 2003, 31, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaji, T.; Weis, D.; Giret, A.; Bouabdellah, M. Coeval potassic and sodic calc-alkaline series in the post-collisional Hercynian Tanncherfi intrusive complex, northeastern Morocco: Geochemical, isotopic and geochronological evidence. Lithos 1998, 45, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, G.N. The A-type granitoids: A review of their occurrence and chemical characteristics and speculations on their petrogenesis. Lithos 1990, 26, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y. Himalayan leucogranites. In Proceedings of the 2014 Annual Meeting of Chinese Geoscience Union (CGU)—Session 34: Tethyan–Tibetan Plateau Geological Evolution and Metallogeny, Beijing, China, 20–23 October 2014. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Eby, G.N. Chemical subdivision of the A-type granitoids: Petrogenetic and tectonic implications. Geology 1992, 20, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.P.; Wang, M.Y.; Qi, K.J. Current research and review on A-type granites. Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2007, 26, 57–66, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, P. Direct paleomagnetic constraint on the closure of Paleo–Tethys and its implications for linking the Tibetan and Southeast Asian Blocks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 14368–14376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Sun, D.Y.; Li, H.; Jahn, B.M.; Wilde, S. A–type granites in northeastern China: Age and geochemical constraints on their petrogenesis. Chem. Geol. 2002, 187, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hunen, J.; Allen, M.B. Continental collision and slab break-off: A comparison of 3-D numerical models with observations. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 302, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.D.; Chung, S.L.; Cawood, P.A.; Niu, Y.; Liu, S.A.; Wu, F.Y.; Mo, X.X. Magmatic record of India–Asia collision. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Ji, W.Q.; Chen, H.B.; Kirstein, L.A.; Wu, F.Y. Linking rapid eruption of the Linzizong volcanic rocks and Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (EECO): Constraints from the Pana Formation in the Linzhou and Pangduo basins, southern Tibet. Lithos 2023, 446, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.C.; Wang, Q.; Weinberg, R.F.; Cawood, P.A.; Zhao, Z.; Hou, Z.Q.; Mo, X.X. Continental crustal growth processes recorded in the Gangdese Batholith, southern Tibet. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2023, 51, 155–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).