Abstract

In a seminal paper V.M. Goldschmidt pointed out that, in terms of volume of the constituent ions, Earth’s crust and mantle are basically a packing of negatively charged oxygen ions bound together by the volumetrically barely significant cations. Here, this statement is revisited using modern assessments of mantle composition and pressure-dependent ionic radii. It is found that the transition to the lower mantle marks a reduction in the O2− crystal ionic volume percentage from 86 to less than 80%, significant enough to suggest an overall reduced compatibility of less abundant elements within the first few hundred km of depth below that transition from lower-mantle to upper-mantle rock. An equivalent drop across both, the 410- and 670 km mantle discontinuities occurs for large polyhedral sites, which are the potential hosts for incompatible elements. Accordingly, most large ionic lithophiles and rare earth elements in the lower mantle are highly enriched in one minor phase, davemaoite. It is proposed that those minor and trace elements that are less compatible with this mineral, such as some of the high-field strength elements, are concentrated in yet unknown accessory minerals that potentially affect geochemical signatures of deep mantle-derived igneous rocks.

1. Introduction

In 1930 V.M. Goldschmidt outlined in a publication in Die Naturwissenschaften [1] the principal features of geochemistry as a modern science. For his study, as for today’s geochemistry, the definition and assessment of ionic radii have been pivotal. The manifold, incessant phase changes and partitioning of elements within evolving Earth spatially average bond states and directions such that what is controlled by the bonding of each element in each existing phase in the Earth appears, for whole rocks, as geochemical distribution patterns that are parametrized by the ionic radii of these elements and bear witness to the geologic history of these rocks.

The series of the many essential statements in Goldschmidt’s paper [1] commences with an interpretation of a table of what he called Earth’s lithosphere composition: basically an assessment of element abundances in continental crust and upper mantle combined. The table lists the nine most abundant elements in weight-%, atomic-%, and volume-%, that is, the cube of the ionic radii which Goldschmidt reported previously [2]. In particular Goldschmidt observed that, in terms of volume-% of the ions, the ‘lithosphere’ is essentially a packing of negatively charged oxygen ions. By balancing the total charge, the cations hold that array of anions together but their contribution to the volume accounts for less than 10%. Thus, by volume, silicate Earth is an array of O2− ions with the cations interspersed. Different from present custom, Goldschmidt used the term ‘lithosphere’ for bulk silicate Earth (BSE). He added that his assessment of element abundances is likely not representative. Nearly a hundred years later, we have a much more representative composition of whole Earth and of the Earth’s mantle [3]. Furthermore, we are informed about the nature of the major seismic discontinuities that occur within the mantle [4,5]. Finally, we have some understanding of the pressure dependence of the ionic radii.

In this paper, I reexamine Goldschmidt’s volumetric assessment of Earth’s mantle’s composition in terms of cubes of ionic radii but as a function of pressure and depth of the Earth, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

In this work, mantle composition is based on the pyrolite model in [3] and an enstatite chondrite model [6] that predicts marked differences between upper- and lower mantle composition. A reference data point for average continental crust is taken from [7]. Ambient pressure- [8] and pressure-dependent crystal ionic radii [9] are used here. One modification of the previously reported pressure dependence of O2− has been applied: In [9] an empirical pressure dependence of O2− by a power-law was given for various bond coordinations and for pressures from about 5 to more than 100 GPa. It has been observed that for pressures between ambient and a few GPa, pressure-dependent radii obtained from different solids exhibit non-negligible variations [9,10]. However, at higher pressures, available data of pressure-dependent crystal structures [9] as well as the correlation of ionic and molar volumes [11] indicate that the pressure-dependent crystal radii are reproducible within uncertainties acceptable for geochemical and crystal chemical assessments. Emphasizing these much higher pressures, the overestimation of r (O2−) from those power laws at pressures below a few GPa remained unaccounted for in the previous studies [9,11]. However, in the present work, an interpolation is needed for the pressure-dependent crystal radius of O2− for bond coordinations three and four between approximately 5 GPa and the ambient pressure values [8]. These interpolated values are listed in the following table. In Table 1 and henceforth in this paper, bond coordination is indicated by Roman numerals as superscripts.

Table 1.

Interpolated values for the pressure-dependent crystal radii of O2− in three- and fourfold bond coordination.

The interpolation is based on the assumption that the power of the pressure-dependent radius of O2− between 0 and 5 GPa is intermittent between the previously reported ones and unity, warranting a continuous and monotonous contraction of the radius.

Generally, the ionic volume, as the stoichiometric sum of the cubes of the pressure-dependent crystal radii of the constituent ions [11], correlates with the difference of their pressure-dependent total ionization potentials [12] through a Morse-type functional relation (e.g., in [13]) which matches expectations from the general compression behaviour of solids over large ranges of pressure [14]. Hence, the linear compression of cations and the power-law pressure dependence of anions appear to be intrinsic to compression of ionic solids. Yet, this does not directly explain the difference in cat- and anion compression. Upon compression, overlap of bond orbitals increases, and bonds generally become more covalent [15]. With the electron density around the anion as the more electronegative ion, decreasing in this process more strongly than that around the cation, the difference between cat- and anion compression over the pressure range of the Earth’s mantle [9] can be conceived as a series expansion in pressure of electron density along the bond directions, where the cations compress linearly and the anions compress with negative power > 1.

Uncertainties in mantle composition and in the pressure dependencies of the radii propagate into an overall uncertainty of volume assessment of ~5%. Only the nine most abundant elements in the mantle are considered, which leaves out 0.21% of the total element abundances, and ionic volumes are normalized to those 99.79%. The remaining 0.21% of elements contribute to about 0.22% of the ionic volume, well within the uncertainty of the volume assessment. The same point holds for minor differences in bond coordination such as for O in enstatite and high-pressure clinoenstatite, which as well are within the ± 1% overall uncertainty and remain unaccounted for.

3. Results

V.M. Goldschmidt pointed out that in terms of the volumes of ions of the most abundant elements, the silicate shell of the Earth can be considered as a packing of oxygen anions with the comparatively much smaller cations interspersed for charge balance [1].

This estimate is based on the cube of the ionic radii of the most abundant elements. Obviously, the volume of minerals is larger than the sum of the ionic volumes, 4π/3 r3, of their constituents because of the steric arrangements of bonds in the various crystal lattices. There is a general linear relation between the sum of the ionic volumes in their stoichiometric proportions and the molar volumes of minerals and solids as a function of pressure that holds at least for simple and complex oxides [11].

Nonetheless a number of interesting observations can be made if Goldschmidt’s approach is extended to the entire pressure range of the Earth’s mantle by using pressure-dependent crystal radii. Based on these radii, the volume fraction of O2− anions (hereafter, VO) for a pyrolite mantle [3] at ambient pressure is 85.4% with additional 19.9 at % Mg, 15.9 at % Si, 2.4, 1.85, and 1.34 at% Al, Fe, and Ca, respectively. The following radii and bond coordinations were used: 1.22 Å for O2− in threefold, 0.86 Å for Mg in six-, 0.4 Å for Si in fourfold coordination, and 0.675, 1.14, and 0.92 Å for Al, Ca, and Fe2+ all in sixfold coordination and Fe2+ in the high-spin state. Other than by Goldschmidt [1], crystal radii rather than ionic radii are used here [8]. Accordingly, the volume fraction of O2− is systematically lower than in [1].

Average continental crust (CC) with the abundances reported by [7] has 84.1 volume-% O2−. Further, there are 10.9 Si, 8.5 Al, 4.5 Fe(2+), 4.1 Mg, 2.7 Ca, 2.1 Na, and 1.8 K, all in % of ionic volume. This estimate is based on a crystal radius of 1.21 Å for OII and the crystal radii for SiIV, AlIV, Fe, and Mg in sixfold and for Ca, Na, K in eightfold coordination from [8]. Based on this assessment, the volume fraction of O2− of the average CC is slightly smaller than that of the upper mantle (UM) at reference ambient pressure (Figure 1). Considering the high silica content of the CC, this seems at first glance surprising. The comparatively low VO of the CC is caused by its high amount of Ca, Na, and K and their contributions to the volume: If the same amount of these elements with the same coordination is substituted for Mg in UM pyrolite, VO of the UM drops to 81%. The net effect of all other differences between CC and UM in composition and ion coordination, such as that of the lower Al coordination, the reduced Mg content of the CC, and the change in the ionic radius of O2− from 1.21 to 1.22 Å, is minor.

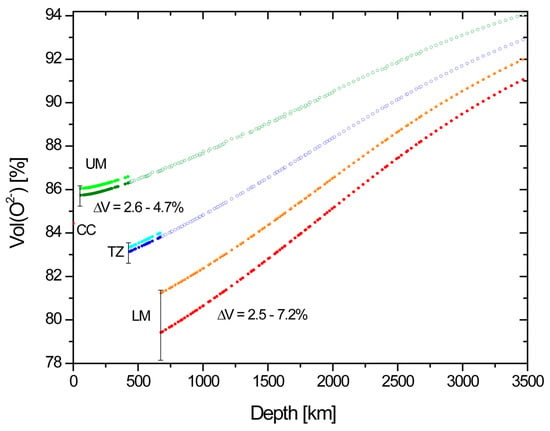

Figure 1.

Dependence of the fractional volume of O2− in Earth as function of depth. Red dot: Continental crust in average [6], UM = upper mantle, TZ = transition zone, LM = lower mantle. Dark colours based on mantle composition from ref. [3], bright ones from ref. [6]. Vertical bars indicate uncertainties.

Thus, the difference in VO between CC and UM is a consequence of the different chemical composition, notably of the high content of large cations in the CC.

In Figure 1 VO of upper mantle (UM), transition zone (TZ), and lower mantle (LM) are given as a function of depth [4]. Data for the UM are obtained from the crystal radii as mentioned above [8], but with the pressure dependencies from [9]. Further, we have, for the TZ: Fe, Al, and 60% Mg sixfold, Ca and 30% Mg twelvefold, 85% Si fourfold, 15% sixfold, O threefold; for the LM: Si, Al, Fe, and 80% Mg sixfold, 40% Mg, twelvefold, Ca twelvefold, 60% O fourfold, 40% sixfold coordinated. Thus, minor differences in bond coordination are neglected. In the lower mantle, the coordination of O2− changes from four- to sixfold in periclase and davemoite, but remains fourfold in bridgmanite. The coordination of all Si is sixfold in bridgmanite and davemaoite, Fe assumes a mixed spin state in bridgmanite and periclase [16], and Mg and Ca keep a twelvefold coordination, Al remains sixfold coordinated. Fe makes a minor contribution to the total ionic volume. Thus, the detailed changes in the spin state with pressure [16] are of no concern in the present assessment. The pressure effect on 10- and 12-fold coordinated Mg has previously been found to be undistinguishable within uncertainties [9] and the pressure dependence for MgX in [9] is used here. VO as a function of depth is shown for the pyrolitic mantle composition from [3] and for an enstatite chondrite model of Earth (Ref. [6], henceforth, EC model), which reports a markedly different LM composition.

Figure 1 shows the pressure dependence of VO for all three regions of the mantle. Two principal observations can be made: (1) VO increases with depth and (2) at each of the major mantle discontinuities, VO drops markedly.

The reduction in VO at the two major mantle discontinuities at 410 and 670 km is much more pronounced than that between CC and UM, despite the equal bulk composition of UM, TZ, and LM or, with the EC model [6], for the LM even more so. Thus, the changes in coordination, that is: chemical bonding, at each of these discontinuities dominate over a change in bulk rock composition as distinct as that between CC and UM. Yet, Goldschmidt’s statement about the dominance of VO over the volumes of all cations [1] is quite well confirmed for BSE over its the whole range of depth of the mantle.

4. Discussion

More quantitatively, the following observations are made:

- VO, the volume fraction of O2− ions of the total ionic volume of BSE, increases monotonously with pressure for each of the three mantle zones, such that in extrapolation from the top to the bottom of the whole mantle, VO gains 6-7% to 91.0 ± 1.0% (Figure 1).

- VO drops at the UM-TZ boundary by between 2.6 and 4.7% and at the TZ-LM boundary by another 2.5–7.2%. These values compare to a 5.1 and 9.6% increase in rock density at the 420 and 670 km discontinuities [4]. Thus, the reduction in VO is a substantial component of the densification at both discontinuities but at 670 km the change in cation coordination accounts for at least a third of the density increase. The enstatite chondrite model [6] remains within uncertainties for UM and TZ, but for the LM, it gives values of VO slightly higher than the initial assessment of uncertainties, which therefore are adjusted to encompass the EC model.

- The comparison between the results for pyrolitic and enstatite chondritic mantle shows that differences between upper and lower mantle affect VO, which, however, does not respond sensitively to compositional differences less marked than those between these two models, at least not with the given uncertainties.

4.1. Geophysical Implications

The increase in volume fraction of O with pressure is the result of the power-law dependence of the crystal radius of O2− with pressure, whereas the cations contract linearly [9]. The causes of this behaviour have been briefly summarized in Section 2. Hence, with increasing pressure, O2− becomes stiffer relative to the cations Si, Mg, Al, Fe, and Ca. However, at each mantle discontinuity, VO sharply decreases. This has the remarkable consequence that the value of VO that we find at the top of the UM is surpassed by LM rock only at the bottom half of the mantle, below 1800 to 2400 km. I find no indication that the main mantle transitions are directly related to the O-volume fraction in the sense of a hypothetical critical value above which a major structural transition has to occur. However, a value of VO of mantle rock of above 90% at the core mantle boundary (CMB) suggests to me that transitions or reactions that reduce this large volume fraction are energetically favoured. The occurrence of the postperovskite-phase of MgSiO3 and the range of proposed mantle-core reactions [17] seem to support this proposition but do not affect VO much, which, however, may rather reflect the limitations of the crystal radius model rather than the absence of any effect. Independent from that, it can safely be stated that dissolution of O in core metal [17] would directly reduce VO.

4.2. Geochemical Implications

The marked drop of VO at the TZ-LM boundary has potential consequences for geochemistry: The volumetric effect of substitution of minor elements whose cation radii deviate somewhat from that of the major constituent increases if VO decreases. This is to firstorder a steric effect, illustrated in Figure 2.

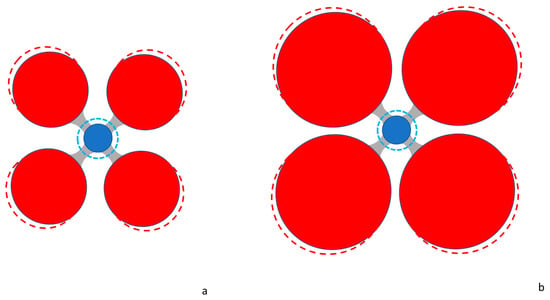

Figure 2.

A simple 2-dimensional illustration of the steric effect of a marked reduction in the ionic volume of O2−, as it occurs at the 410- and 670 km boundaries. Red circles = O2−, blue circles = cation. The radius of the cation is the same in both figures, but in (a) the radius of O2− is reduced by 2. Grey areas indicate the bond vectors (a square 4-fold coordination in this case, which may be taken for a cut through the base plane of an octahedron). Next it is assumed that the cation is substituted by a larger ion (blue dashed circle, again of equal radius in (a) and (b)): With bond distance constant O2− is pushed further out (dashed red circles), thus increasing the polyhedral volume but significantly less so for large compared to small O2−. In this illustration the effect is shown for an area only, but it is easily conceived that the effect is more pronounced in volume. This suggests that polyhedra with large contribution of the anions to the volume are more compatible with cation substitution than those with small anions.

However, it is noted that the actual bond states, although only in spherical average, are incorporated in the crystal radii, which allow for such volumetric assessments (otherwise the radius of, for instance, O2− would be invariant under different coordination). Consequently, the volumetric effect is not purely geometric. This point will be further examined in the following section in the context of established relations between partition coefficients and ionic radii and the compression of polyhedral volumes in general. According to the proposed steric effect (Figure 2), minor and trace elements are expected to become less compatible in rock-forming minerals if VO is reduced, and the effect is expected to be noticeable when the change is VO is abrupt, such as at the 410 and 670 km discontinuities. Thus, the drop in VO at the TZ-LM boundary by 5.1–9.6% potentially marks a regime where such elements are enriched in accessory phases rather than dissolved in the main minerals. In fact, this generic crystal chemical argument seems to avail: In the TZ, Ca is dissolved in majoritic garnet Mg3(Mg,Si)Si3O12, which accounts for 40 mol% of the TZ, whereas in the LM, it forms a distinct phase, davemaoite CaSiO3, which accounts only for 5–8% of the LM [3,6]. Davemaoite hosts other large lithophile elements, U, Th, and rare earth elements, but it less compatible for Li, Rb, Cs, Ba, Nb, Ta, and Hf [18,19]. Based on the above crystal chemical reasoning it is proposed here that these trace elements enter accessory minerals rather than being distributed between bridgmanite, davemaoite, and periclase. These accessories are insignificant by volume and elasticity, thus, seismically invisible but, if present, these phases control the geochemical budget of the elements that they host. Being constituents or noticeable components in such accessories, they are expected to show differences upon chemical partitioning and, for instance, may enrich Nb over Ta or Zr of Hf. This point seems rather abstract, considering the strong chemical similarity of these elements at ambient conditions, which is a consequence of the lanthanide contraction. However, within the regime of pressures of the lower mantle, these elements are predicted to undergo marked changes in the valence electron states, which make them much less similar than they are at atmospheric pressure [12]. Hence, in the LM effective separation of these elements that are seen separated in mantle-derived igneous rocks is conceivable.

The same argument can be made for moderately siderophiles such as Mo, W, and Re: They are suggested to enter accessories rather than residing in the three main minerals. This could be sulfides, carbides, nitrides, hydrides, and iron metal, as well as oxides.

The proposed regime of reduced minor- and trace-element compatibility extends at least to the depth where VO of the LM has recovered the value that it had just above the 420km transition. This occurs at a depth of between 1200 and 1900 km.

At even greater depths, the overall increase in VO with depth is expected to outweigh the effect of the mantle transitions and reduce the differences in minor and trace element compatibility in main rock minerals, which, consequently, are expected to become more accommodating for minor and trace elements.

At the UM-TZ boundary, the effect of the changed partial ionic volumes of minor and trace elements could be important if the actual ΔVO is closer to the upper bound of the present assessment of 4.7%. The proposed effects are the potential consequence of the steric effect of the change in VO on trace element substitution, but it can be quantified better by looking at element partitioning and polyhedral volumes. This is attempted in the following section.

Geochemical Implications–Polyhedral Volumes

The logarithm of partition coefficients of trace elements is correlated to the square of the difference between the ionic radii of the element substituted and the element substituting [20,21]. This relation is quite well established for the partitioning of traces between solids and melts of compounds with O2− as constituent and has originally been shown to hold for simple halides [16,17,18,19]. The slope of the correlation RT lnD = const r0(ri − r0)2 involves the Young modulus of the crystal site at which the substitution takes place [20,21]. Here the partition coefficient D is taken as the ratio of the concentration of an element in the solid phase over that in a liquid or fluid phase in equilibrium.

Further, it is known that polyhedral volumes compress along a general correlation Bpoly/750 = n/d3, where Bpoly is the polyhedral bulk modulus in GPa, n the formal valence of the cation, and d the cation-anion distance in Å [22]. The Young modulus of the sites where substitution takes place is expected to exhibit the same or similar compression behaviour: The sum of the Young moduli along all stress directions is not identical to but dominated by the elastic tensor components that constitute the bulk modulus.

Here, an average polyhedral bulk modulus ⟨Bpoly⟩ is calculated as the sum of the basic polyhedral building blocks of pyrolite in upper-mantle, transition-zone, and lower-mantle rock as follows:

for the upper mantle. For the transition zone ⟨Bpoly⟩ is estimated as

and for the lower mantle as

all in GPa, which gives a general increase in polyhedral elastic strength with pressure for all the mantle regions, as expected, but also shows a drop of 7% at the UM-TZ boundary and a drop of almost 19% at the TZ-LM boundary (Figure 3).

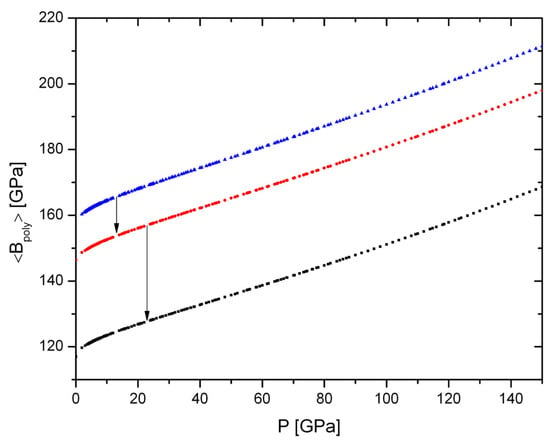

Figure 3.

Evolution of ⟨Bpoly⟩, the average value of the polyhedral volume for pyrolitic mantle with blue = upper-, black = lower mantle, red = transition zone. Equivalent to the volumetric fraction of O2− as a function of pressure, the average polyhedral volume increases with pressure but drops markedly at both major mantle discontinuities (indicated by arrows).

For trace elements that show no preference for sites, this drop signals a marked reduction in compatibility between TZ and LM.

The softening of Bpoly with increasing geothermal temperature is not considered here, as we are concerned with a principal crystal chemical effect, in particular, right at the two major mantle discontinuities where temperature is nearly constant. The present assessment is far from a quantitative forward modelling of mantle minor- and trace-element distributions, which requires more information than we currently have (see below) and that would also involve actual geotherms (globally and regionally).

The drop in ⟨Bpoly⟩ between UM and TZ is primarily caused by the increase in the anion bond coordination and radius. The marked drop at the TZ-LM boundary results in part from the change in Si-bond coordination, in part from the further increase in radius and bond coordination of O2−. This finding about the averaged polyhedral volume is equivalent to the above observations about the effect of the change in VO because the cause of the discontinuities is the same: coordination changes of cat- and anions as function of pressure.

Most trace elements are expected to have preferences for specific sites. In fact, most of the incompatible elements concentrate in clinopyroxene in the shallow region of, and in garnet in, the deeper upper mantle and in the transition zone, whereas in the lower mantle they take refuge in the crystal lattice of davemaoite [18,19]. In the light of pressure-dependent ionic radii, this observation is further quantified: We take the percentage of large polyhedral sites, which are known to host the geochemically most important incompatible elements such as the rare earth elements, the large ionic lithophiles, and the heavier high-field-strength elements for upper mantle, transition zone, and lower mantle as

for the TZ (neglecting 8% of sixfold coordinated Si in majorite). For the UM the same formula is used but with the radii of threefold coordinated O2− and a gradual increase in the fraction of MgX from 0 to 0.3. For the LM we use:

(neglecting that 8% of Si is bound to O also in sixfold coordination in davemaoite).

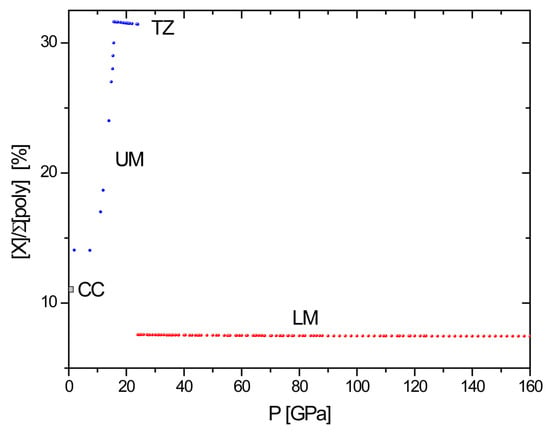

The numerators in these two formulas indicate what is depicted in Figure 4: The transformation of garnet to bridgmanite removes nearly 3/4th of the polyhedral volume in potential host phases for incompatible elements. Although Mg in bridgmanite has 10-fold bond coordination, it is known to be incompatible for rare earths, large ionic lithophiles, and heavier high-field-strength elements [18,19]. In comparison, davemaoite possesses a larger A-site and O with higher bond coordination and, therefore, larger crystal radius than in bridgmanite, which observations bring us back to the initial argument that was made about the steric effect of VO (Figure 2). The change in available large polyhedral sites leaves davemaoite as host phase among the rock-forming minerals of the LM. However, davemaoite has been found not to be compatible (that is, with D < 1) for Li, Rb, Cs, Ba, Nb, Ta, and Hf [18,19]. Having ‘no place to go’, these elements may still be hosted in davemaoite or, as suggested above, are enriched in accessory phases. It is not possible to make strong predictions about which phases these might be, but it is suggested here that they might be post-spinel phases of the maohokite-chenmingite- or xieite-tschaunerite series, which have suitably large crystal sites and also show, in part, noticeable solubility of alkaline elements [23]. This observation also holds for liuite [23], although the A-site in this perovskite is not as large as that in the post-spinel oxides, but it suggests that perovskite-type accessory phases similar to those of the isolueshite-goldschmidtite series are also plausible host phases. Notably goldschmidtite has been found as inclusion in a mantle diamond [24].

Figure 4.

Approximate percentage of large polyhedral sites in upper mantle (UM), transition zone (TZ), and lower mantle (LM). As in Figure 1, continental crust (CC) is given for reference. UM + TZ exhibit the largest proportion of large polyhedra due to the high phase proportion of garnet. The 670 km boundary implies a significant drop in large crystal sites available for hosting mantle-incompatible elements. Interestingly CC is intermediate between UM and LM, owing to the high abundance of free silica in the upper, and pyroxene in the lower, CC (which are not further discriminated here), which tentatively is consistent with the proposed general trend: The CC exhibits a large variety of minerals enriched in elements that are less compatible with the feldspar-, amphibole-, or clinopyroxene-structures, whereas the upper mantle hosts the bulk of incompatible elements in garnet.

It is important to note that any such concentration of minor and trace elements in accessories requires their mobilization and local enrichment through partial melts or fluids, which ties the question of mineral variety and trace-element distribution to the amount of, and depth at which chemically bound water occurs within the lower mantle.

5. Conclusions

The assessment of the contributions of the most abundant chemical species to the volume of the mantle with pressure-dependent crystal radii confirms Goldschmidt’s [1] statement about bulk silicate Earth as a packing of O2− anions with the cations contributing little to its volume, while they balance the charge. It is found that pressure increases the O2− volume fraction monotonously, that, however, at each of the major mantle discontinuities at 410 and 670 km depth it is reset to markedly smaller values such that right at the 670 km discontinuity, the O2− volume fraction drops to less than 80%. It is argued that these sudden reductions in the O2− volume fraction potentially reduce minor- and trace-element compatibility in major rock-forming minerals and formation of accessories enriched in these elements. These accessories are not seismically observable but affect geochemical distribution patterns of rocks who sample these regions of Earth. The pressure dependence of polyhedral volumes and the change in percentage of large polyhedral sites in rock-forming minerals that may host such elements support this proposal. In particular, Li, Rb, Cs, Ba, Nb, Ta, and Hf may segregate into minor accessories, given partial melts or fluids to mobilize them. Hence, the mineralogy of deep Earth may not be as plain as commonly assumed.

In particular, the boundary regions between crust and mantle, upper mantle and transition zone, transition zone and lower mantle have the potential of evolving into narrow horizons of rich mineralogy due to the release of fluids correlated with these major chemical or crystal chemical transitions. This point holds for the subcontinental lithospheric upper mantle, at least locally for the upper mantle–transition zone boundary [25,26], and conceivably for the boundary between transition zone and lower mantle. Based on the crystal chemical arguments of this paper, the region below 1200–1900 km depth is predicted to be chemically less distinct, whereas the CMB region is potentially rich in mineral speciation if reactions with core metal occur. This has been proposed based on experiments and geodynamic modelling but is also consistent with the reduction in VO of deep mantle rock, which is suggested here to be energetically favourable.

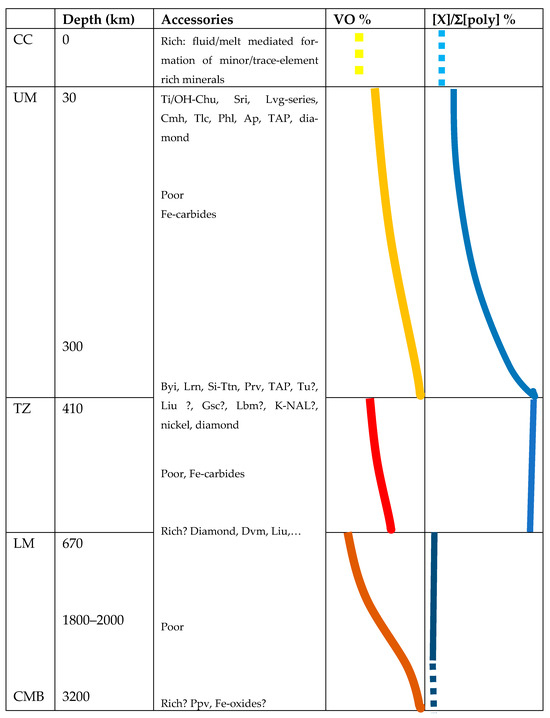

The following picture of richness in mineral species in different regions of the Earth’s mantle is proposed (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic overview of potential zones of rich mineralogy and effective segregation of trace elements in the mantle. The evolution of VO and the percentage of large over total polyhedral volumes are taken from Figure 1 and Figure 4. Only observed minerals are listed. Abbreviations of mineral names are taken from the current IMA list: Ap = apatite, Byi = breyite, Chu = clinohumite, Cmh = carmichaelite, Dvm = davemaoite, Gsc = goldschmidtite, Lbm = liebermannite, Lrn = larnite, Liu = liuite, Lvg = loveringite, Phl = phlogopite, Prv = perovskite, Sri = srilankite, Tlc = talc, Tu = tuite. Further, Si-Ttn stands for Si-dominated titanite, K-NAL for the K-bearing ‘NAL’-phase, TAP stands for the ‘10Å-phase’, and ppv for the ‘postperovskite phase’.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data are presented in this paper or given in the cited references.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Goldschmidt, V.M. Geochemische Verteilungsgesetze und kosmische Häufigkeit der Elemente. Die Naturwiss. 1930, 49, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, V.M. Die Gesetze der Krystallochemie. Die Naturwiss. 1926, 21, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.F.; Sun, S.-s. The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 1995, 120, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewonski, A.; Anderson, D.L. Preliminary Reference Earth Model. Phys. Earth Planet. Int. 1981, 25, 297–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringwood, A.E. Phase transformations and their bearing on the constitution and dynamics of the mantle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1991, 55, 2083–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javoy, M.; Kaminski, E.; Guyot, F.; Andrault, D.; Sanloup, C.; Moreira, M.; Labrosse, S.; Jambon, A.; Agrinier, P.; Davaille, A.; et al. The chemical composition of the Earth: Enstatite chondrite models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 293, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Gao, S. Composition of the Continental Crust. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Rudnick, R.L., Holland, H.D., Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 1–64, 659p. ISBN 0-08-043751-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic-radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschauner, O. Pressure-Dependent Crystal Radii. Solids 2023, 4, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G.V.; Cox, D.F.; Ross, N.L. The incompressibility of atoms at high pressures. Am. Min. 2020, 105, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschauner, O. Systematics of Crystalline Oxide and Framework Compression. Crystals 2024, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, M.; Cammi, R.; Ashcroft, N.W.; Hoffmann, R. Squeezing All Elements in the Periodic Table: Electron Configuration and Electronegativity of the Atoms under Compression. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10253–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschauner, O. Towards an Extended Concept of Tolerance Factors for Postspinel Phases. Minerals 2025, 15, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, W.B. Equations of state for solids under strong compression. High Press. Res. 1998, 16, 81–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prewitt, C.T.; Downs, R.T. High-pressure crystal chemistry. In Ultrahigh-Pressure Mineralogy: Physics and Chemistry of the Earth’s Deep Interior; Hemley, R.J., Ed.; Mineralogical Society of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; Volume 37, pp. 283–317. [Google Scholar]

- Sturhahn, W.; Jackson, J.M.; Lin, J.F. The spin state of iron in minerals of Earth’s lower mantle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L12307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K.; Labrosse, S.; Hernlund, J. Composition and State of the Core. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2013, 41, 657–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K.; Shimizu, N.; van Westrenen, W.; Fei, Y. Trace element partitioning in Earth’s lower mantle and implications for geochemical consequences of partial melting at the core–mantle boundary. Phys. Earth Planet Inter. 2004, 146, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corgne, A.; Liebske, C.; Wood, B.J.; Rubie, D.C.; Frost, D.J. Silicate perovskite-melt partitioning of trace elements and geochemical signature of a deep perovskitic reservoir. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundy, J.; Wood, B. Prediction of crystal-melt partition coefficients from elastic moduli. Nature 1994, 372, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, H. Trace Element Partition Coefficient in Ionic Crystals. Science 1966, 152, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazen, R.M.; Finger, L.W. Bulk modulus—Volume relationship for cation-anion polyhedra. J. Geophys. Res. 1979, 84, 6723–6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Tschauner, O.; Beckett, J.R.; Prakapenka, V.B. New high-pressure Fe-Ti oxide minerals in the Shergotty Martian meteorite: Feiite, Fe 2+2(Fe2+Ti4+)O5, liuite, FeTiO3, and tschaunerite, (Fe2+)( Fe2+Ti4+)O4. Meteor. Planet. Sci. 2025, 60, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.A.; Wenz, M.D.; Walsh, J.P.S.; Jacobsen, S.D.; Locock, A.J.; Harris, J.W. Goldschmidtite, (K,REE,Sr)(Nb,Cr)O3: A new perovskite supergroup mineral found in diamond from Koffiefontein, South Africa. Am. Min. 2019, 104, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercovici, D.; Karato, S. Whole-mantle convection and the transition-zone water filter. Nature 2003, 425, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Tschauner, O.; Yang, S.; Humayun, M.; Liu, W.; Gilbert Corder, S.N.; Bechtel, H.A.; Tischler, J. HIMU Geochemical Signature Originating from the Transition Zone. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020, 542, 116323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.