Abstract

The city of Aigion, located in the northwestern Peloponnese, flourished as an important city-state especially during the Hellenistic period (323–32 BC). This is evidenced by abundant archaeological remains, including kilns, waste pits, and pottery workshop facilities. Among the ceramic goods produced by local workshops are various types of stamped and unstamped transport amphorae. Also, recent discoveries, approximately 15 km southeast in the village of Trapeza Diakopto, have uncovered a distinctive type of amphora—identified as Type B of the Corinthian–Corcyraean or Ionian–Adriatic tradition—from destruction layers dated to the 4th and early 3rd centuries BC. This study examines the technological attributes and provenance of transport amphorae from both sites through integrated petrographic and mineralogical analyses, drawing on 27 samples from Aigion and 17 from Trapeza. Petrographic analysis, focusing on compositional and textural characteristics, identified three distinct ceramic recipes (petrographic fabric groups AIG-1, AIG-2, and AIG-3) associated with amphora types I, II, and III at Aigion. Samples from Trapeza were grouped into two main fabric categories (TR1 and TR2a/b), along with a notable number of singletons. Moreover, petrographic observations combined with X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) analysis provided insights into the firing technologies used. The results indicate that many amphorae from both Aigion and Trapeza were fired at temperatures below 850 °C, while others were fired at higher temperatures, ranging from approximately 900 °C to 1100 °C. The combined petrographic and mineralogical evidence illuminates local ceramic production techniques and interregional exchange patterns, contributing to a broader understanding of amphora manufacture and distribution in the northwestern Peloponnese from the Late Classical to the Late Hellenistic period.

1. Introduction

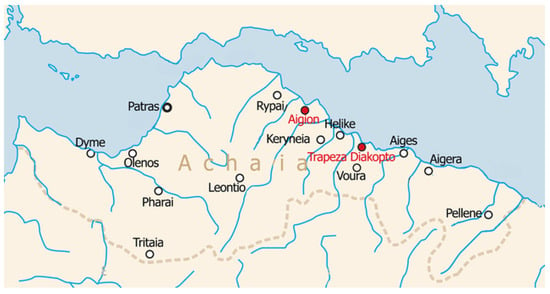

The city of Aigion is located in the northern Peloponnese, in the eastern part of the province of Achaea (Figure 1). It was one of the most important centers of ancient Greece, playing a key role in shaping the social and economic dynamics of the region. As the capital of both Achaean Leagues (A and B), the city strongly opposed Macedonian rule. During the Hellenistic period, beginning with the death of Alexander the Great, Aigion experienced significant population growth and a notable economic upturn. Following its conquest by the Romans, however, the city gradually lost its privileges—due primarily to its geographical position, especially when compared with the more advantageous location of Patras relative to the Italian peninsula—leading to its decline. Aigion’s prominence began to recover in the 1st century BC [1,2,3,4,5].

Figure 1.

The province of Achaea in antiquity [1]. The archaeological sites considered in the present study are marked with red ellipses.

Extensive archaeological excavations conducted by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Achaea have revealed the city’s urban layout across different historical periods. Pottery workshops and kilns, waste-disposal areas, and building remains have been identified, many of which have yielded stamped transport-amphora handles as well as numerous rim, body, and base fragments. These finds, which are associated with local products [1,2,3,4,5], suggest that misfired fragments and stamped handles point to local amphora production closely linked to nearby workshops. Situated near the ancient agora and the city’s port, these workshops were ideally positioned for both the manufacture and the efficient distribution of locally produced goods.

During the construction of the new railway line, building remains and roads belonging to an ancient settlement were discovered in the village of Trapeza Diakopto. Located approximately 15 km southeast of Aigion, Trapeza functioned as a port connected to the hinterland and the ancient city of Voura [5,6]. The settlement dates from the late 6th to the 3rd century BC—spanning the end of the Archaic period through the Hellenistic era—and excavations have uncovered amphorae originating both from other Greek centers and from more distant regions, indicating the site’s distinct commercial character.

Amphorae from Aigion often bear rectangular stamps with the names ΚΕΡΔΩΝOΣ, ΣΩΤHΡΙΧOΥ, or ΖΩΙΛOΥ, likely identifying local pottery workshop owners. At least three amphora types have been documented, two of which share fine micaceous fabrics containing chert, with a pale red–yellow coloration, dating from the 2nd century to the end of the 1st century BC. These vessels resemble products from nearby Corinthian workshops while also recalling Brindisian forms, suggesting possible movement or migration of potters between regions. Amphora production in Aigion reflects agricultural surpluses and a vibrant trade network that expanded after the destruction of Corinth in 146 BC [1,2,3,5].

Excavations at ancient Voura have yielded large quantities of intact and fragmentary Type B Ionian–Adriatic amphorae [5]. These vessels exhibit characteristic features typical of western Greek amphora production. While some examples align with Corcyrean production, variations in shape and fabric—at least three macroscopically distinct groups—indicate that many were likely produced in the northwestern Peloponnese.

The present article unfolds the ceramic production patterns in the two neighboring sites of Achaea, namely, Aigion and Trapeza, based on compositional and technological patterns revealed by the archaeometric investigation of the two amphora assemblages.

The information obtained from the petrographic analysis is important for identifying the source of the raw materials, for determining the composition of each sample, and, subsequently, for understanding production issues. Additionally, information on the firing temperature of each sample and on the source of the raw materials can also be obtained from the mineralogical analysis by means of X-ray diffraction in conjunction with the results of the petrographic analysis.

2. Geological Setting

In the broader region, the hydrographic network is primarily shaped by the catchments of the Meganitis, Selinous, Kerinitis, Vouraikos, Ladopotamos, and Krathis Rivers. These rivers flow through a geodynamically evolving area. During the Neogene and Pleistocene periods, their sediment load was trapped and deposited in the hydrographic network.

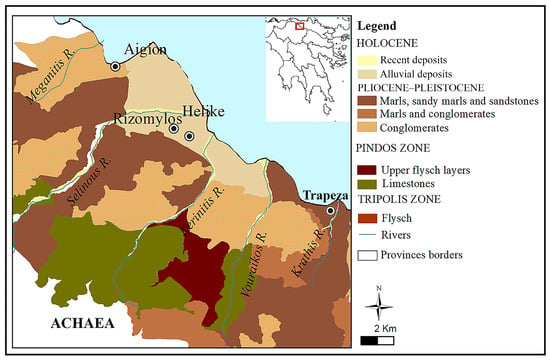

The city of Aigion lies between the basins of the Meganitis and Selinous Rivers (Figure 2). The city is located at the External Hellinides and, more specifically, in the Pindos geotectonic unit. The area of Aigion consists of Holocene alluvial deposits found in river basins and coastal zones, while the inland areas are made up of Pliocene–Pleistocene marls, sandstones, and conglomerates. Conglomerates are also present along the coastline. In the southern section, the formations include flysch and limestones from the Pindos unit, as well as primarily flysch from the Tripolis unit.

Figure 2.

Geological map of the study area (modified by Xanthopoulou [7] from IGME Aigion Sheet [8]).

The village of Trapeza is also located within the Pindos unit and is composed of Plio-Pleistocene marine sediments, including sands, clays, and conglomerates, which lie above older fluvial and lagoonal sediments. Additionally, Upper Cretaceous pelagic limestones from the Pindos unit are exposed due to the activity of the NW-SE faults. The primary source of these sediments is the Vouraikos and Krathis Rivers. The former contributes to Pliocene deposits, while the latter is associated with Lower Pleistocene deposits.

The Selinous basin is structured by two sedimentary environments. The first is an alluvial fan depositional environment, where sediment grain size varies significantly. From south to north, there is a noticeable increase in sandy and silty layers, while the conglomerates become thinner and contain smaller particles. The second environment consists of recent alluvial deposits, including cobbles, sands, and sandy mud. These materials have been deposited in various parts of the river system, specifically within the riverbed, along the banks, and at the estuary.

During the Quaternary period, the deltas of the Kerinitis and Vouraikos Rivers have undergone substantial transformation. Their deltaic and alluvial fans have accumulated up to 500 m of conglomerates, sands, and fine sediments, deposited under both marine and terrestrial conditions. Dart [9] identified erosional surfaces in these regions and proposed that some deposits originated in lacustrine or marine environments. Specifically, the Vouraikos River delta deposits lie unconformably above older lagoonal sediments from the Upper Pliocene to Late Pleistocene and are composed of alternating layers of conglomerates, sandy marls, clays, and marls.

3. Materials and Methods

The samples considered in the present study were collected from the city of Aigion and from Trapeza village and included 40 amphorae and 2 tiles. More specifically, a set of 27 specimens, macroscopically classified into three main amphora typologies (types I, II, and III; Table 1), was carefully selected from the city of Aigion. Among them, amphora type I consists of 15 samples, type II of 8 samples, and type III of 2. Two tile samples were also collected, potentially playing the role of reference material.

Table 1.

Classification of Aigion samples according to the amphora type.

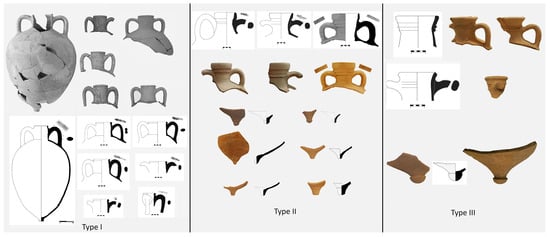

Amphorae of type I (Figure 3) have a height of 64 cm, with a rim diameter of about 12 cm, a base diameter of 3.5 cm, a maximum body diameter of approximately 40 cm, and a capacity of approximately 38 L [2,3]. The rim is usually beak-shaped, rarely oval in cross-section, and quite thin. The amphora neck of type I is mainly cylindrical, relatively narrow and short, and, in some cases, has slightly inwardly sloping walls. It has a broad oval-shaped body with an extremely narrow knob-type base, and its outline is curved. The handles of the amphorae, thin and oval in cross-section, are slightly upwards and then curve sharply. In some cases, on their outer surface, two or three vertical grooves can be observed, while they can also have rolled (bifid) handles, similar to Koan-type amphorae. Often only one of the handles has a rectangular banded stamp, measuring approximately 7 × 1.8 cm, with the name of the potter fabricant engraved on it.

Figure 3.

Aigion. Local transport amphorae (types I, II, and III). Second century BCE.

Type II (Figure 3) is similar to the so-called Greek Brindisian amphora type, which is characterized by a high, vertical or outwardly sloping, thick rim, with a curve on its upper surface and two characteristic plastic bands, the upper one being larger than the lower one, placed on the upper part of the short neck [1,2,3]. Although no intact type II amphorae from the workshops of Aigion have been preserved, comparisons with parallel intact examples from shipwrecks or terrestrial sites [3] suggest that the body of this amphora type was broadly ovoid, terminating in a low conical base with a hemispherical configuration on its lower surface. At the height of the band, solid, coarse handles of circular or almost circular cross-section are attached. These take at the upper part of the neck and then arch to the shoulder. One handle bears a rectangular banded type stamp, with names probably associated with the ceramic workshop owner or the fabricant.

In the type III amphorae (Figure 3), the rim is thick and quite high, with an angular outline and a maximum outer diameter ranging from 13.3 to 14.8 cm. The neck is low and has a conical shape, surrounded by two similar horizontal plastic ridges. It is estimated that the body of type III amphorae is broadly ovoid, while the knob-type base is small and hemispherical. The handles have a solid, fairly robust, circular cross-section, with curves and more often without stamps. Two tile samples were also included, potentially playing the role of reference material, as they bear stamps with the ethnic Aἰγιέων, a fact that indicates their unquestionable origin from the city of Aigion [1,2,3].

The samples selected (n = 15) from the amphora assemblage unearthed in Trapeza Diakopto belong to a different type of amphora, the so-called Type B of the Corinthian–Corcyraean or Ionian–Adriatic type (Figure 4), and come from destruction layers dated to the 4th and early 3rd century BC [4]. This distinctive type of pointed-bottom amphora, which is widely distributed throughout Western Greece and the Italian peninsula, at least from the mid-4th century BC, features a characteristic rim with a triangular cross-section, prominently projecting and compressed at the points where the handles are attached, giving it an oval shape. The tall cylindrical neck usually bears a plastic ring at its upper part, situated between two horizontal grooves. The shoulder has sloping, straight walls, and the body is conical, ending in a narrow cylindrical toe with a curved formation on its lower surface. The handles are tall, with an oval cross-section, rising upward, typically to the height of the rim and then curving and straightening out slightly outward, toward the shoulder of the vessel. Rarely, they bear circular stamps on the handles with the initials “BO”. While it may be tempting to identify these initials with the city of Voura, similar stamps are usually attributed to Corcyra (Corfu) and also to Lefkada [6]. Their exterior surface is typically covered with a thin yellowish or brownish slip. The large quantities of these amphorae found in the coastal settlement of ancient Voura, the presence of some stamps with the initials “BO”, and the initial macroscopic observation of at least three different fabric groups, led to the hypothesis that they may possibly be local products of northwestern Peloponnese [4].

Figure 4.

Trapeza Diakopto. Type B Ionian–Adriatic amphorae; 4th–early 3rd century BCE.

All of the selected specimens were thin-sectioned and ground to powder using an agate mortar at the Minerals and Rocks Research Laboratory of the Department of Geology at the University of Patras, Greece. The thin sections prepared were examined using a Zeiss AxioScope A1 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) polarizing microscope, aiming to describe the mineralogical and textural characteristics of the groundmass according to the methodology proposed by Quinn [10,11] and Whitbread [12,13]. Photomicrographs were captured under plane polarized light (PPL) and crossed polars (XP) employing a Jenoptik ProgRes C3 videocamera (Jenoptik AG, Jena, Germany) attached to the microscope and processed with ProgRes Capture Pro 2.5 software. X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) was performed at the Minerals and Rocks Research Laboratory of the Department of Geology, the University of Patras, using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), with Ni-filtered Cu-Kα radiation, operating at 40 kV/40mA, equipped with a Bruker LynxEye fast detector (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The scan range covered was 2–70 °2θ with an interval of 0.015 °2θ every 0.1 s [14,15]. The qualitative analysis of the XRPD patterns obtained was performed using DIFFRACplus EVA software release 2006 v.12 (Bruker-AXS, Madison, WI, USA) based on the ICDD Powder Diffraction File (2006 version). The XRPD analysis permitted us to study the mineralogical composition of the analyzed samples for further confirmation of the petrographic results and, in addition, to obtain information about the newly formed mineral phases, which are indicative of the firing conditions during the manufacturing process.

4. Results

4.1. Petrographic Description

The petrographic examination of the samples from Aigion revealed three main (3) petrographic fabric groups (AIG-1, AIG-2, AIG-3). The distribution of the samples into groups was based on mineralogical and textural features.

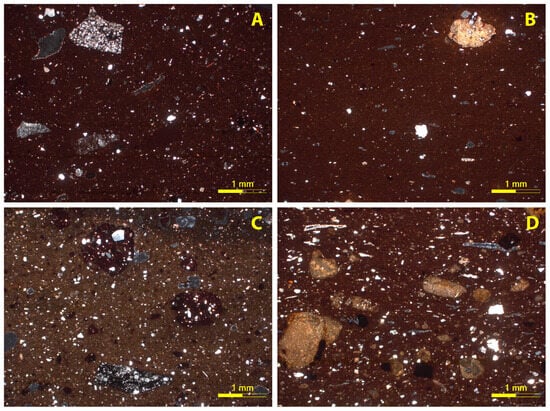

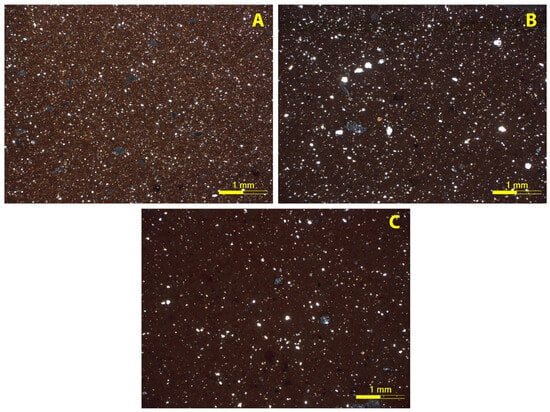

Petrofabric AIG-1 is further differentiated into two sub-groups, AIG-1a and AIG-1b. Of these, AIG-1a constitutes the most extensively represented ceramic group in this study, encompassing 13 samples (A1, A4, A6, A7, A8, A9, A12, A13, A15, A19, A21, A24, and A25), and is characterized as a fine micaceous fabric with striated b-fabric. These samples share significant common petrographic characteristics that allow their joint classification into the same group. Their micromass has mainly a ferrous composition and is optically active (Figure 5A). Its color ranges from reddish-brown to yellowish-brown under crossed polars (XP) and light yellowish to light reddish-brown under plane-polarized light (PPL). Porosity is classified as meso- to mega-pores, and the voids are represented by irregularly shaped non-oriented pores. The c:f:v10μ ratio ranges between 3:85:2 and 25:75:10. The nonplastic inclusions consist of subangular to subrounded or rounded grains ranging in size from very fine sand to granule (0.076–2.28 mm). Most of the samples are characterized by a striated b-fabric, specifically random, monostriated, and, in some cases (A1, A6, A9, A12, A19, and A25), porostriated b-fabric. Samples A8 and A13 exhibit an initial sintered clay matrix, indicating a higher firing temperature than the other samples. The dominant constituent is the monocrystalline quartz, white and brown mica, whereas micritic calcite follows. Radiolarian chert and mudstone breccia are present in subordinate quantities, whereas mudstone and sandstone fragments, plagioclase, and calcite are rarely encountered. In sample A9, the clay mixing of a ferrous clay paste within the micritic clay paste is evident.

Figure 5.

Representative photomicrographs (all under XP) of the petrofabrics identified in the Aigion amphorae: (A) subfabric AIG-1a (sample A6; amphora type II); (B) subfabric AIG-1b (sample A11; amphora type I); (C) petrofabric AIG-2 (sample A26; tile); (D) petrofabric AIG-3 (sample A2; amphora type III).

The petrofabric AIG-1b consists of nine samples (A5, A10, A11, A14, A16, A17, A20, A22, and A23), and is differentiated from AIG-1a due to the less micaceous clay paste and the lower presence of the fine fraction. Its micromass has a ferro-calcareous composition, which is optically active. It shows a light reddish-brown and light-brown color in PPL, while in XP, it is reddish or orange-brown (Figure 5B). The c:f:v10μ ratio is around 3:95:2. The nonplastic inclusions consist of subangular to subrounded grains ranging in size from very fine to medium sand (0.076–0.304 mm). The dominant mean mode of the aplastic inclusions falls at a medium silt fraction (~0.114 mm). The dominant constituents are monocrystalline quartz and micritic calcite, whereas white and brown mica follow. Radiolarian chert and mudstone fragments are present in fewer quantities in samples A5, A11, and A17. The content of mudstone breccia is significantly lower in relation to petrofabric AIG-1a, whereas plagioclase is rarely encountered. Speckled and striated b-fabric is observed in samples A5, A10, A11, A15, and A16. Furthermore, evidence of clay mixing is recognized in samples A10, A11, and A16.

The second petrofabric (AIG-2) consists of three samples (A18, A26, and A27) and is differentiated from the previous due to the larger inclusions and the common participation of mudstone breccias. Its micromass has a ferro-calcareous composition and is characterized as slightly optically active. The color of the micromass ranges from yellowish to olive brown in PPL, while in XP, the color is olive brown to brown (Figure 5C). The grain size ranges from very fine sand (~0.076 mm) to a fraction of granules (<2.72 mm), with the exception of sample A27, which reaches the fraction of fine pebble (~5.038 mm). The shape of the inclusions varies from rounded to subangular. Monocrystalline quartz dominates, whereas mudstone breccias and micritic calcite are common constituents (Figure 5C). Radiolarian chert is rarely encountered. The c:f:v10μ ratio is 25:70:5. Textural concentration features (Tcf), such as rounded “yellowish” clay pellets, are observed within the matrix, giving evidence of clay mixing and suggesting different approaches to clay preparation.

The third petrofabric (AIG-3) comprises two samples (A2 and A3), which are highly calcareous, since limestone fragments and micritic calcite dominate. More specifically, it is a coarse fabric with a grain size reaching the fraction of granules (~2.04 mm), whereas the finest fraction falls in very fine sand (~0.076 mm). It is poorly sorted and exhibits a single-spaced porphyric-related distribution. The inclusions and voids are oriented to the margin of the sherd. The c:f:v10μ is 20:70:10, and the voids are represented by meso- to macro-planars. Concerning the textural concentration features, crystallitic and porostriated b-fabric are often exhibited. The color of the micromass ranges from reddish to olive brown under XP and red to brown in PPL (Figure 5D). The dominant components are sparitic limestone fragments and micritic calcite, whereas secondary calcite often fills the pores. Monocrystalline quartz and white mica are common constituents, whereas brown mica is rarely observed. Chert, sandstone fragments, and bioclasts (microfossils) are present in subordinate quantities.

The amphorae from Trapeza were described and classified separately from those of Aigion, always paying attention to possible similarities between the two sites. The detailed petrographic description showed differentiations between the two regions, so the Trapeza samples will be presented as new petrofabrics.

The Trapeza samples were classified into two main petrofabrics (TR1 and TR2) and several singletons (i.e., samples with their own distinctive compositional and/or textural characteristics that do not permit their matching to any of the established petrographic fabric groups). A detailed description of the petrographic characteristics by petrofabric group follows.

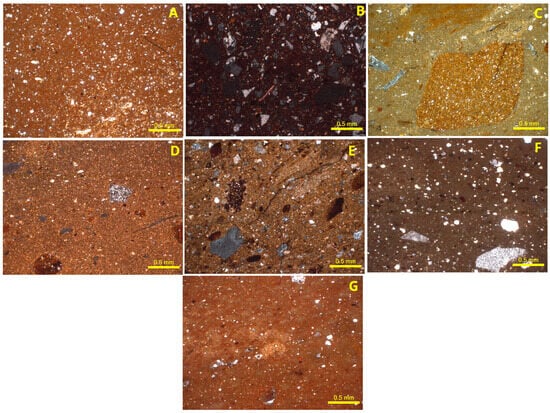

Petrofabric TR1 is a very fine micaceous fabric (Figure 6A) and encompasses three samples (B1, B12, and B14). The fabric is well sorted; its color is yellowish-brown under crossed polars (XP) and brown in plane-polarized light (PPL), and the micromass is moderately optically active. The grain size does not exceed very fine sand (<0.076 mm). Monocrystalline quartz and white mica are the dominant constituents, whereas brown mica is present in smaller quantities.

Figure 6.

Representative photomicrographs of the petrofabrics established for Trapeza amphorae, which all belong to the so-called Type B of the Corinthian–Corcyraean or Ionian–Adriatic type (all under XP): (A) petrofabric TR1 (sample B1), (B) subfabric TR2a (sample B2), and (C) subfabric TR2b (sample B9).

Petrofabric TR2 consists of five samples and is further subdivided into two sub-groups, TR2a and TR2b. Sub-group TR2a includes three samples (B2, B3, and B8) and is differentiated from the other fabrics due to its slightly larger grain size, which falls in the fine sand fraction (~0.19 mm), and its moderate sorting (Figure 6B). The color of the micromass ranges from olive to reddish-brown under XP and brown in PPL and is moderately optically active.

Sub-group TR2b consists of two samples (B6 and B9) and exhibits slightly different textural characteristics from TR2a. The color of the micromass ranges from red to olive under XP and light olive and brown in PPL, whereas its micromass is slightly optically active. Moreover, the micromass exhibits an initial sintering, indicating a firing temperature over 800 °C (Figure 6C).

Singletons

Sample B4: micaceous fine petrofabric with b-fabric

The fabric is characterized by the dominant participation of white and brown mica and micritic calcite. It is characterized by crystallitic and striated b-fabric and by an optically active micromass. The color of the micromass ranges from yellowish to reddish-brown in XP and brown under PPL (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Photomicrographs (all under XP) of the singletons encountered in the present study, which all belong to the so-called Type B of the Corinthian–Corcyraean or Ionian–Adriatic type: (A) sample B4; (B) sample B5; (C) sample B7; (D) sample B10; (E) sample B11; (F) sample B13; (G) sample B15.

Sample B5: coarse petrofabric with mica flakes

This petrofabric encompasses quartzite and mica schist fragments, mica flakes (muscovite and less biotite), plagioclase, monocrystalline quartz, and rarely volcanic and metabasic rocks (including titanite). The groundmass is inhomogeneous, and the color of the micromass ranges from brown to yellowish-brown in crossed polars (XP) and light brown under plane-polarized light (PPL) (Figure 7B). It contains angular to subangular aplastic inclusions of coarse sand size, with a maximum grain size of 1.028 mm. It exhibits moderate sorting, and c:f:v10μ = 20:75:5.

Sample B7: tempered bimodal mudstone

This petrofabric is characterized by a bimodal grain size distribution with a conspicuous presence of mudstone fragments. The micromass is calcareous, and its color is yellowish and olive brown under XP and light olive brown in PPL (Figure 7C). The grain size reaches up to the gravel fraction (~3.61 mm) and exhibits a close to open porphyric-related distribution. Subangular to angular fragments of mudstone, micritic limestone, micritic calcite, and white mica are the dominant constituents. Sandstone and micritic limestone fragments are present in lower quantities. It also exhibits crystallitic and striated b-fabric and has a slightly optically active micromass.

Sample B10: coarse petrofabric with calcareous clay matrix

The fabric of this sample is characterized by a calcareous micromass with the participation of a low percentage of coarse aplastic inclusions (Figure 7D). Specifically, their abundance is about 10%, and their grain size reaches very coarse sand (~1.9 mm). They are mainly represented by subrounded to rounded mudstone breccias, whereas quartzite and radiolarian chert fragments are less represented. Mica–schist fragments and plagioclase are rare constituents. The finest inclusions are represented by micrite and white and brown mica.

Sample B11: radiolarian chert and sparitic limestone aplastic inclusions

Petrofabric B11 can be characterized as a coarse fabric with the participation of radiolarian chert and sparitic limestone fragments in a calcareous clay matrix. The color of micromass is orange-brown under XP and brown in PPL and is slightly optically active (Figure 7E). The grain size reaches up to the very coarse sand fraction (~1.14 mm), whereas the finest fraction falls at the fine sand fraction (~0.014 mm), but their shape does not indicate an intended addition. The c:f:v10μ ratio is 10:85:5. The presence of reddish textural concentration features (Tcf) is possibly indicative of clay mixings between a calcareous and a non-calcareous raw material.

Sample B13: silicate aplastic inclusions

This petrofabric is characterized by the presence of silicates (quartz and K-feldspars) and mica and an initial sintered micromass. Its color is olive brown under XP and grayish olive in PPL, and it is optically active (Figure 7F). The grain size ranges from fine to coarse sand (~0.114–0.7 mm), whereas the aplastic inclusions have a subangular to subrounded shape. Regarding their distribution, they show a close- to single-spaced porphyric-related distribution. The aplastic inclusions’ shape is not indicative of tempering, but of preexisting material within the clay. The coarse fraction is represented by chert fragments, whereas the fine fraction comprises mono- and polycrystalline quartz and brown and white mica. Amorphous concentration features (Acf), such as iron oxides, are often encountered within the clay matrix.

Sample B15: fine micaceous petrofabric

It is a fine fabric characterized by the high proportion of brown mica. The grain size reaches very fine sand. The color of micromass ranges from reddish to olive brown under XP and light brown to light olive in PPL. It is optically active, whereas the color inhomogeneity indicates the initial sintering of the micromass (Figure 7G).

4.2. Mineralogical Analysis Through X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD)

The mineralogical analysis of the amphorae from Aigion enabled us to classify them into three classes based on their mineralogical associations (Table 2) and define their estimated equivalent firing temperature, which is given in ascending order as follows:

Table 2.

Classification of Aigion samples, according to their estimated equivalent firing temperatures (EFTs) and mineralogical associations (mineral abbreviations: Qz: quartz, Pl: plagioclase, Di: diopside, Gh: gehlenite, Hm: hematite, Cc: calcite, and Ill: illite).

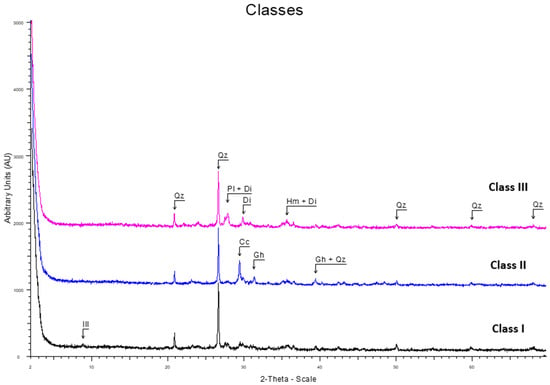

Class I includes four samples (A11, A16, A21, A25) and is represented by the mineralogical association quartz + plagioclase + illite and traces of hematite, diopside, and calcite (Figure 8). The presence of illite and the very low content of calcite, as well as of diopside and hematite, probably suggests a transitional firing regime in which calcite initiates a reaction with illite to produce gehlenite. Different reactions result in the formation of diopside and hematite. These mineralogical phases indicate a firing temperature under 900 °C [8,14,15,16].

Figure 8.

Representative X-ray diffraction patterns of the main mineralogical classes revealed in the Aigion samples. Mineral abbreviations: Qz: quartz, Pl: plagioclase, Di: diopside, Gh: gehlenite, Hm: hematite, Cc: calcite, and Ill: illite.

Class II includes seven samples (A1, A2, A3, A19, A20, A24, and A26) and is represented by the mineralogical association quartz + calcite + plagioclase + diopside + hematite + gehlenite (Figure 8). The presence of gehlenite, plagioclase, and diopside indicates a firing temperature between 850 and 950 °C [8,14,15,16].

The last class (III) consists of 16 samples (A4–9, A10, A12, A13, A14, A15, A17, A18, A22, A23, A27). This class is characterized by the mineralogical association quartz + plagioclase + diopside + hematite ± calcite ± gehlenite (Figure 8). The presence of diopside and plagioclase indicates a firing temperature above 900 °C [8,14,15,16].

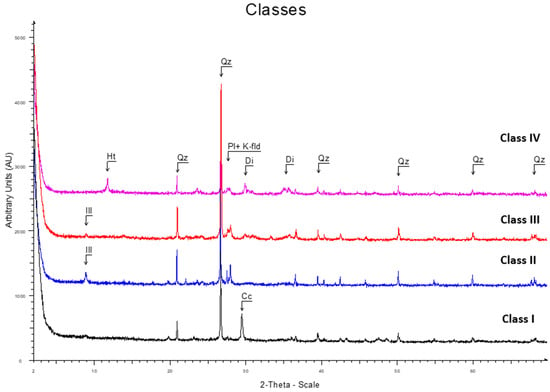

In the case of the amphorae from Trapeza Diakopto, the identified mineralogical phases enable us to classify them into four mineralogical classes (Table 3). Class I includes two samples (B10 and B11) consisting of quartz, calcite, and illite (Figure 9). The presence of calcite and illite indicates a firing temperature between 700 and 850 °C [8,14,15,16].

Table 3.

Classification of Trapeza Diakopto samples, according to their estimated equivalent firing temperatures (EFTs) and mineralogical associations. Mineral abbreviations: Ill: illite, Qz: quartz, Pl: plagioclase, Di: diopside, Gh: gehlenite, Cc: calcite, K-fld: K-feldspar, and Ht: hydrotalcite.

Figure 9.

Representative X-ray diffraction patterns of the main mineralogical classes revealed in the Trapeza samples. Mineral abbreviations: Ill: illite, Qz: quartz, Pl: plagioclase, Di: diopside, Cc: calcite, K-fld: K-feldspar, and Ht: hydrotalcite.

Class II includes only sample B5, which has the following characteristic mineralogical association: quartz + alkaline feldspars + plagioclase + illite. This sample can be characterized either as non-calcareous (due to the absence of calcite) or fired at about 900 °C, due to the remaining illite and the absence of calcite (Figure 9).

Class III includes eleven samples (B1, B2, B3, B4, B6, B7, B8, B9, B12, B13, B14) and is characterized by the initial formation of the mineralogical phases of diopside and gehlenite. Specifically, it is characterized by the association quartz + alkaline feldspars + plagioclase + illite + diopside + gehlenite ± calcite (Figure 9). This association suggests a firing temperature between 850 and 950 °C.

Class IV includes only sample B15, which consists of quartz, plagioclase, alkali feldspars, diopside, and hydrotalcite (Figure 9). The presence of plagioclase, diopside, and gehlenite indicates a firing temperature between 900 and 1100 °C.

5. Discussion

The integration of data obtained from petrographic descriptions of thin sections and mineralogical evaluations of X-ray diffraction patterns revealed a high degree of homogeneity in terms of composition and firing practices. Specifically, the petrographic analysis of Aigion samples indicated that the two primary types of amphorae, I and II, were likely produced using the same recipe, with only minor variations (see Table 4). The fine-grained texture of AIG-1 suggests that the clay raw material may have been settled or sieved to eliminate the coarser fractions. In contrast, the amphorae of AIG-2 were constructed using coarser materials that included subrounded mudstone breccia. Whitbread [13,17] referred to these aplastic inclusions as originating from Roman transport amphorae at Ancient Corinth. Similar rock types have been identified in prehistoric pottery from sites such as Tsoungiza (EH I and II) and the Nemea Valley Archaeological Project (EH II), as well as at Korakou, Tiryns, and Midea [18]. In both cases, the mudstone breccias showed a subangular shape, whereas in our analysis, they exhibited a subrounded morphology, suggesting their prior presence in the raw material and indicating a local origin. Amphorae classified as type III were made using a distinctly different recipe compared to types I and II. Additionally, one of the type I amphorae contained a clay recipe similar to that of locally identified ceramics. All the identified constituents correspond to local lithological formations, reinforcing the notion of local provenance for these amphorae. The variety of recipes indicates the use of different types of clay raw materials.

Table 4.

Classification of petro-groups in relation to amphora type from both sites.

In the case of the Trapeza Diakopto amphorae, two main petrographic groups were identified, along with a few individual samples. Groups TR1 and TR2 are distinguished by the slightly larger inclusions observed in TR2, which suggests differences in the clay pre-processing techniques. The sintered clay matrix of the TR2b samples indicates that they were fired at a higher temperature. As for the petrographic groups characterized as singletons, their compositional discrepancies suggest they may represent suspected imports to the Trapeza Diakopto site. Specifically, sample B5 contains aplastic inclusions that are not related to the local geology, implying it was imported from outside the broader region, potentially indicating trade relations with the Cyclades Islands. Another possible import is sample B7, as similar sedimentary rocks have been found in the Early Helladic I fabric from the Berbati Valley (Argos, Greece) and Corinthia (Greece) [13,18]. However, as noted by Xanthopoulou et al. [7], petrographic description of sandy sediments from the Vouraikos River, which flows into Diakopto and the western area of Trapeza, has revealed fragments of micritic limestone, sandstone, chert, and mudstone.

Concerning the firing choices, most of the Aigion samples appear to have reached firing temperatures of more than 900–950 °C (Table 5). The majority of the samples of AIG1 and both fabrics AIG2 and AIG3 exceed the firing temperature of 950 °C. The rest of the samples are limited to lower firing temperatures, with slight differences. As for the Trapeza Diakopto samples, the main fabrics TR1 and TR2 are fired under the same temperature conditions. It is worth further discussing the presence of hydrotalcite in sample B15, which suggests that the specific sherd was exposed to specific conditions within the burial environment (e.g., water flow, salinity, temperature). The formation of hydrotalcite can affect the ceramic material, potentially altering its structure and composition. In some cases, it can contribute to the overall degradation of the amphorae, while in others, it might create a protective layer [18].

Table 5.

Comparative table of mineralogical classes and petrographic groups of Aigion and Trapeza Diakopto.

The results were correlated with the mineralogical composition of the sediments in the surrounding area. The clay source for the Hellenistic transport amphorae may originate from either the Selinous River or the Neratzies region in Aigialia, located to the west of Aigion, near the Salmeniko River. The Selinous River catchment is noted to have a higher abundance of chert material compared to the Neratzies catchment. Furthermore, Xanthopoulou et al. [7] collected calcareous sand samples primarily consisting of micritic limestone fragments, with rare occurrences of sparitic calcite, from the Selinous River. These sands are also notably rich in radiolarian chert and mudstone. Xanthopoulou also gathered samples from various formations, including sandy marls, sands, sandstones, and clay layers in the area, some of which contain mudstone fragments. Another potential source could be the vicinity of the Kerinitis River, where Xanthopoulou et al. [7] noted that the clays have a composition similar to those found near the Selinous River.

The observed variability in clay recipes among the Aegion amphorae indicates that potters operated in close interaction with a geologically diverse yet readily accessible landscape. The exploitation of various clay sources and the different preparation techniques suggest a flexible production system adapted to the heterogeneity in the nearby sedimentary deposits. Moreover, the consistency of firing schemes followed (>900–950 °C) illustrates the potters’ ability to control firing conditions and their easy access to fuel resources, thus underlying a technologically embedded production tradition rather than a small-scale manufacture.

The amphorae from Trapeza Diakopto display greater compositional variability, reflecting the sedimentary heterogeneity in the Vouraikos River system and its wider catchment. The great number of petrographic groups and singletons showing non-local compositional signatures suggests a production environment embodying both local manufacturing and circulation of imported vessels. The variability noticed indicates that potters operated within a landscape with less uniform raw materials, both in terms of quality and composition, by adapting their technological behavior. This pattern is consistent with a production environment shaped by variable sediment inputs and sustained interaction with a broader regional exchange network.

6. Conclusions

This paper examines Hellenistic–Early Roman stamped transport amphorae from the Aigion area, applying mineralogical and petrographic analyses through X-ray diffractometry and optical microscopy. The findings reveal that most amphorae were fired at temperatures exceeding 950 °C. Comparisons with local geological data suggest that the raw materials for these amphorae were likely sourced from the broader Aigion area. Additionally, the production of these ceramics shows a notable homogeneity, indicating a high level of proficiency among Aigion potters. In contrast, analysis of samples from Trapeza indicates significant heterogeneity. Microscopic assessments demonstrate that several samples required separate petrographic classification, denoting them as “loners.” This variance is evidenced by the presence of large voids (mega-pores) that suggest inadequate homogenization. While several Trapeza samples displayed fine-grained material, some featured coarser grains, indicating a mix of preparation techniques. Despite this, the potters exhibited notable expertise in clay mixing and tempering.

Regarding firing conditions, the majority of Trapeza samples appear to have been fired in open fire, given that the maximum temperature they sustained has never exceeded 850 °C. An exception is the B15 sample recovered from a shipwreck, which suggests the possibility of kiln firing. The raw materials for these samples seemingly originate from the surrounding regions, with the notable exception of sample B5, which contains imported metamorphic debris. In summary, a comparative analysis indicates that potters from Aigion possessed superior skills relative to their Trapeza counterparts, as reflected in the higher quality of their amphorae, characterized by fewer and smaller voids. This study enhances our understanding of the technological practices and material sourcing of Hellenistic–Early Roman ceramics in the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.X., K.F. and I.I.; methodology, V.X., K.F., A.V., P.S. and I.I.; software, V.X., A.V. and I.I.; validation, V.X., K.F., A.V., P.S. and I.I.; formal analysis, V.X., K.F., A.V., P.S. and I.I.; investigation, V.X., K.F., A.V., P.S. and I.I.; data curation, V.X., K.F., A.V., P.S. and I.I.; writing—original draft preparation, V.X., A.V. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, V.X., K.F. and I.I.; visualization, V.X., K.F., A.V., P.S. and I.I.; supervision, V.X., K.F. and I.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Panagiotis Balasis for the preparation of the thin sections, as well as Paraskevi Lampropoulou for performing the XRPD analysis of the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Filis, K. The Local Transport Amphorae from Aigion. In Traditions and Innovations: Tracking the Development of Pottery from the Late Classical to the Early Imperial Periods. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference of IARPotHP, Berlin, Germany, 7–10 November 2013; Japp, S., Kögler, P., Eds.; Phoibos Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2016; pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Filis, K. Stamped transport amphorae from Aigion. In Proceedings of the 9th Scientific Meeting on Hellenistic Pottery, Thessaloniki, Greece, 5–9 December 2012; Kotsou, E., Ed.; Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Archaeological Receipts Fund: Athens, Greece, 2018; pp. 407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Filis, K. The Ovoid Amphorae from Aigion, in the NW Peloponnese. The Connection with Corinth and Brindisi. In Proceedings of the A Family Business: The Ovoid Amphorae in the Central and Western Mediterranean. Between the Last Two Centuries of the Republic and the Early Days of the Roman Empire, University of Seville, San Fernando, Spain, 10–11 December 2015; Garcia Vargas, E., Roberto de Almeida, R., Gonzalez Cesteros, H., Saez Romero, A.M., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Filis, K. Trapeza Diakoptou Aigialia, NW Peloponnese: Regional and interregional exchanges. Indications from transport amphorae. In Proceedings of the Daily Life in a Cosmopolitan World: Pottery and Culture During the Hellenistic Period, Lyon, France, 5–8 November 2015; Phoibos Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2019; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Filis, K. Transport amphoras from domestic and workshop facilities as indications for economic changes in the societies of NW Peloponnese from late 6th to 2nd century BC. In Assemblages of Transport Amphoras: From Chronology to Economics and Society, Panel 6.6, Archaeology and Economy in the Ancient World 36; Lawall, M.L., Ed.; Propylaeum: Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filis, K. The Transport Amphoras from the Port and Storage Facilities of Ancient Lefkada. Local and Regional Exchange Networks. In Proceedings of the Manufacturers and Markets: The Contributions of Hellenistic Pottery to Economies Large and Small, 4th IARPotHP Conference, Athens, Greece, 11–14 November 2019; Rembart, L., Waldner, A., Eds.; Phoibos Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2022; pp. 264–278. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, V.; Iliopoulos, I.; Katsonopoulou, D.; Katsarou, S. Standardized patterns in the ceramic craft at Early Bronze Age Helike, Achaea, Greece. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2022, 14, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoflias, P.; Tsoflias, C.; Fleury, J.; Ioakim, C. 1:50,000-Scale Geological Map, Aegio Sheet; Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration: Athens, Greece, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dart, C.J.; Collier, R.E.L.; Gawthorpe, R.L.; Keller, J.V.A.; Nichols, G. Sequence stratigraphy of (?)Pliocene–Quaternary synrift, Gilbert-type fan deltas, northern Peloponnesos, Greece. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 1994, 11, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P. Ceramic Petrography. In The Interpretation of Archaeological Pottery and Related Artefacts in Thin Section; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, P. Thin Section Petrography, Geochemistry & Scanning Electron Microscopy of Archaeological Ceramics; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbread, I. A proposal for the systematic description of thin sections towards the study of ancient ceramic technology. In Archaeometry: Proceedings of the 25th International Symposium; Maniatis, Y., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Oxford, UK, 1989; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbread, I. Appendix 3. The collection, processing and interpretation of petrographic data. In Greek Transport Amphorae: A Petrological and Archaeological Study; Whitbread, I., Ed.; British School at Athens: Athens, Greece, 1995; pp. 365–396. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, V.; Iliopoulos, I.; Avramidis, P. Assessment of clayey raw material suitability for ceramic production, in the Northern Peloponnese, Greece. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2021, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliozzo, E. Ceramic technology. How to reconstruct the firing process. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.; Day, P.M.; Alram-Stern, E.; Demakopoulou, K.; Hein, A. Crafting and consumption choices: Neolithic—Early Helladic II ceramic production and distribution, Midea and Tiryns, Mainland Greece. In Pottery Technologies and Sociocultural Connections Between the Aegean and Anatolia During the 3rd Millennium BC. Oriental and European Archaeology 10; Alram-Stern, E., Horejs, B., Eds.; Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Wien, Austria, 2018; pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbread, I.K. Clays of Corinth: The study of a basic resource for ceramic production. Corinth 2003, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miše, M.; Quinn, P.S.; Glascock, M.D. Lost at sea: Identifying the post-depositional alteration of amphorae in ancient shipwrecks. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2021, 134, 105463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.