Abstract

The integration of multi-omics approaches is changing microbial biotechnology towards greater environmental sustainability. This review aims to critically evaluate the application of integrative multi-omics and bioinformatics approaches to elucidate the microbial mechanisms underlying bioleaching, with a particular emphasis on key chemolithoautotrophic bacteria and filamentous fungi. Scientists can now reveal and understand the complex molecular mechanisms that allow microbes to survive in extreme environments that are rich in metal through the integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. This review shows how the use of multi-omics approaches reveals the interconnected stress responses in important bioleaching bacteria, such as Acidithiobacillus, and fungi like Trichoderma, establishing a connection between genes and their functions. This comprehensive understanding is achieved through the application of advanced computational technologies. Moreover, this review assesses the bioinformatics pipelines, from genome assembly to differential expression analysis, using tools such as DESeq2, while highlighting how machine learning and metabolic modelling can be used to predict interactions and enhance consortia for practical applications in bioleaching. Challenges such as data complexity and expenses exist; however, the field is on the verge of significant advancements. Emerging technologies, especially single-cell omics and CRISPR-based modifications, offer unmatched accuracy in modifying microbial systems. Ultimately, the combination of advanced omics with complex bioinformatics creates a strong foundation for developing next-generation, high-efficiency microbial strategies for environmental metal recovery from waste.

1. Introduction

In recent years, it has been observed that metal pollution arising from metal-rich waste streams, such as electronic waste (e-waste) and mine tailings, has created a significant and multilayered environmental and economic challenge worldwide [1,2,3]. Although these wastes are known to contain valuable and sometimes scarce or rare earth metals (such as e-waste), it has been observed that their recovery is difficult for traditional methods [4,5]. This is due to their heterogeneous nature, and the presence of these metals also occurs in low concentrations, which is why most are labelled as low-grade ore sources. As much as traditional methods, such as pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy, are perfected for metal recovery, their application in low-grade ore has been proven to be uneconomical [6]. Furthermore, they are known to be one of the processes with severe environmental effects since they require high energy inputs, use harmful chemicals, and generate toxic fumes [6]. Therefore, there is a need for sustainable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly approaches that will help meet the global demand for metals, which is increasing in line with current technological advancements and population growth.

An example of a sustainable and cost-effective method is the bioleaching process, a microbial metal solubilization process that is seen as a promising approach for addressing the challenges faced by conventional methods in low-grade ore/waste metal recovery [7]. The main feature of bioleaching is its reliance on the natural metabolic activities of microorganisms with bioleaching abilities. These microorganisms, through their metabolic activities, are able to solubilise metals and ultimately allow their recovery from low-grade ores and waste that would otherwise be uneconomical to process. Bioleaching is not a new process, and research has been conducted on microorganisms with bioleaching potential. Well-known examples of microorganisms studied include chemolithoautotrophic bacteria such as Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and Leptospirillum ferrooxidans, and chemoorganotrophic heterotrophs, such as Aspergillus niger and Penicillium [8,9]. Chemoorganotrophic heterotrophs represent a group of fungi that leach metals using indirect methods. The fungi secrete organic acids and solubilize metals through acidolysis, complexation, and redoxolysis mechanisms. Chemolithoautotrophic bacteria get energy from oxidizing inorganic compounds like ferrous iron (Fe2+) and reduced sulfur species [10,11,12]. This process helps regenerate ferric iron (Fe3+), which serves as an important oxidant in metal bioleaching processes [6,10,11]. It is because of these abilities that a range of minerals and substrates can be targeted for metal recovery. Furthermore, in fungi, the range is further expanded to include those that are less accessible to bacterial attack, such as silicate and refractory ores.

At this point, biochemical principles important to bioleaching are well established; however, their translation into robust and predictable large-scale industrial processes remains a challenge, especially for fungi. The challenge comes with the complexity of adapting a naturally occurring process of a consortia into an engineered environment. Over the years, it has been proven that culture-dependent microbiological processes only capture a limited snapshot of microbial diversity [12]. Due to culture-independent methods, it is widely known that microbial consortia in processes such as bioleaching are also composed of unculturable microorganisms whose metabolic role, interactions, and adaptive responses are poorly understood [13,14]. This has created a “black box” scenario, where during experiments, ore or a source of metals is introduced to a consortium and metal solubilisation is measured as observed in a study by Xia et al. [15]. However, the intricate biological activities, such as inter-kingdom interaction, remain invisible and uncharacterised. This then contributes significantly to the inconsistencies in the bioleaching rates, efficiencies, and the inability to manipulate microbial consortia towards optimizing the bioleaching process.

Advances in high-throughput sequencing and the integration of multi-omics approaches, such as, metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics, enable us deeply to explore and understand microbial communities involved in bioleaching [16,17]. Metagenomics looks at the total genetic potential of microorganisms in such environments. We are now able to reconstruct genomes or metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) directly from DNA extracted from environmental samples [18,19]. This is where most novel genes important for bioleaching are discovered. This includes, but is not limited to, genes encoding for metal resistance mechanisms, sulfur and iron oxidation pathways in bacteria, and organic acid production in fungi. Metatranscriptomics looks at the expression of genes under different environmental conditions, for example, which genes are differentially expressed under high metal content, pH, and nutrient limitation. This is very important as it reveals which microbial activities are activated and can be harnessed for process optimisation [20]. Complementing the two genomic methods, metaproteomics looks at the enzymes produced that enable the function of the microorganism, such as bacterial rusticyanin or fungal citrate synthase. Metabolomics then aids in characterising the metabolites (organic acids and ferric iron) produced during processes catalysed by enzymes [16]. This multilayered dataset creates a direct functional link between microbial genetic potential and the biochemical processes driving metal recovery.

The integration of multi-omics with advanced bioinformatics is currently advancing the bioleaching process. We are now moving from just reporting studies, where metal leaching organisms are listed and the metal leaching and efficiency are mentioned, to more descriptive studies, where complex microbial consortia across genera and kingdoms’ activities are described Li and Wen [16]. Not only will this enable the identification or discovery of novel bioleaching genes from uncultured microorganisms, but it will reveal the molecular determinants of metal resistance, adaptation, metabolic cooperation, and competition within and between kingdoms. In this context, this review offers a clear overview of multi-omics and bioinformatics applications that help explain the molecular mechanisms of metal solubilization, stress tolerance, and adaptation in microbial bioleaching systems. The review also shows how these methods connect genes, pathways, and metabolic results. This supports the rational design and optimisation of microbial consortia for environmentally sustainable metal recovery. This comprehensive understanding not only enhances our capacity to recover valuable metals from waste or low-grade ores but also leads to safer and more effective remediation strategies that will ultimately reduce the ecological footprint of mining activities.

2. Omics Technologies

The importance of omics technologies lies in their ability to determine the different focus areas for cellular function. This can be done through the use of high-throughput methods to give an overall overview of what happens in a biological system. Genomes offer a complete blueprint of organisms, and techniques such as whole-genome sequencing and metagenomics are the reason behind the increasing number of catalogued genes in different organisms. In addition to revealing their inherent metabolic capabilities, potential biochemical pathways for processes such as bioleaching are also revealed [16,21].

Moving beyond the cataloguing of genes, the application of transcripts aids in capturing the real-time activities of the genes through the sequencing of total RNA under low pH and heavy metal experimental conditions. This answers the question of “what genes are actively being used under these conditions” [20,22]. This is one of the important pieces of information, especially for process optimisation. This will enable researchers to pinpoint the functional roles of microorganisms under stressful or extreme conditions similar to those observed in bioleaching [20,22]. When proteomics is applied, it then adds to the pieces of information by directly identifying and quantifying the key proteins produced by the cell under such extreme conditions. This then confirms that transcription leads to functional biological activities while giving insights into the modification of proteins to control specific biological processes [23].

Metabolomics then complements the above by analysing the full range of small-molecule metabolites, observed when a specific biological reaction has occurred [24]. A snapshot of the physiological state and the biochemical outcomes of microbial activity carried out by the produced enzymes is revealed [21]. When these metabolites are tracked through targeted or untargeted analysis, scientists can observe and report on the flow of biochemical reactions to provide an understanding of how efficient bioleaching microorganisms are able to remain metabolically active in extreme conditions [20,21,24]. Altogether, the integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics provides a powerful multi-dimensional perspective on microbial systems, transforming our ability to study and harness their functions in complex environmental and industrial contexts [20,25,26].

3. Integrative Multi-Omics

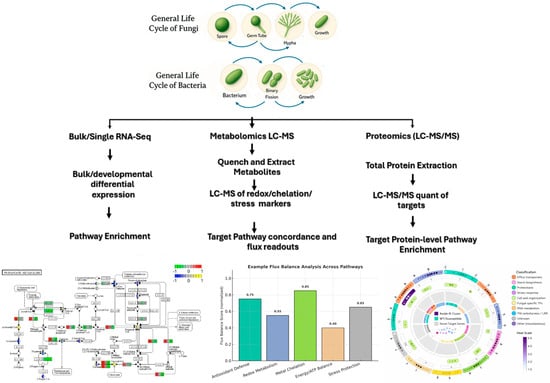

As explained above, the application of individual omics technologies does provide valuable snapshots of biological systems; however, their true capacity is mostly realised through integration. Therefore, when multiple omics techniques are combined (Figure 1), we are able to move from descriptive studies that involve the cataloguing of genes to construct predictive, mechanistic models that explain genetic potential to cellular functions and ultimately to ecosystem processes efficiency in metal bioleaching [20,26,27,28,29]. This holistic approach is crucial because biological information flows in a directional manner, and regulation occurs at each step [30]. For instance, the presence of a gene (genomics) does not always guarantee its expression (transcriptomics), and mRNA abundance does not always correlate with protein activity (proteomics) or metabolic output (metabolomics) [16,31]. For instance, an acidophilic bacterium may possess the genomic potential for iron oxidation, but only integrative analysis can confirm whether these genes are highly transcribed in low-pH or high-metal conditions. Below are case studies to support the importance of multi-omics applications.

Figure 1.

A flow diagram representing a multi-omics workflow that is used to investigate and understand microbial communities during bioleaching. The approach integrates transcriptomics, proteomics, and metagenomics data to transition from gene identification to confident inference of key bioleaching microbial processes.

3.1. Case Study 1: Deciphering Stress Responses in Acidithiobacillus

When it comes to bacterial bioleaching, the species Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, known as the model organism. However, due to the extreme conditions present during bioleaching, Acidithiobacillus’s activity is also challenged. This section focuses on how, through the application of multi-omics, we can move from merely describing genes reported in A. ferrooxidans grown in extreme bioleaching conditions to understanding what happens beyond endurance and survival through metabolic activities activated under such stressful conditions. Currently, studies that integrate multi-omics are not widely available; therefore, the information in this section has been compiled from multiple studies. Summaries of omics methods, conditions, and strains are given in Table 1. If we look at stress response studies based on the genomics of A. ferrooxidans, a study by Muñoz-Villagrán et al. [29] used two strains of A. ferrooxidans, denoted as psychrotolerant PG05 and the Antarctic strain MC2.2. They laid the groundwork by identifying genes related to metal tolerance. This includes the czcD, znuA, and copA genes (a comprehensive list of genes is provided in this study), which are associated with metal tolerance for lead, zinc, and copper, respectively. Furthermore, their genomics analysis revealed a collection of metal-stress response mechanisms. To list a few, this includes genes for cold adaptation (such as cold shock proteins, trehalose biosynthesis genes, and fatty acid desaturases), as well as oxidative stress defense (e.g., multiple superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase genes). In addition, the two strains had their own unique mechanisms, where the Antarctic strain MC2.2 exhibited genetic redundancies in mercury resistance operons (merA, merT, merP), while the Patagonian strain PG05 showed evidence of polyphosphate granule formation linked to metal tolerance. All these provide a blueprint of how these organisms not only endure and survive but also maintain metabolic activity under stressful conditions. The stressful conditions in this case include low temperature, high metal loads, and acidic pH. This then forms the basis for genetic determinants that could be targeted for process optimisation.

Table 1.

Summary of results from Case study 1.

The importance of multi-omics becomes apparent when genomics is integrated with other omics techniques. Genomics alone reveals the potential abilities, but with transcriptomics, we can build on the genomic blueprint and provide a view of how A. ferrooxidans modulates gene expression in real-time. A key study by Osorio et al. [26] on the master transcriptional regulator FNR (FnrAF) in A. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 offers a clear example. Fumarate nitrate reduction transcription factor (FNR) is an oxygen-sensing transcriptional regulator that is meant to control the switch between aerobic and anaerobic respiration [32]. FNR allows organisms to optimize energy production in a dynamic, changing environment, ensuring survival through the utilization of the most efficient respiration pathway, whether in the presence or absence of oxygen [33]. In the study by Osorio et al. [26] RT-qPCR was used to quantify the different levels of FNR transcript under various physiological conditions. The transcription of FNR was observed in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions; however, its expression was significantly upregulated in the stationary phase of anaerobic conditions. This is very important because it shows that the switch between conditions is not only influenced by the presence of oxygen, but also by the growth phase of the culture. How does this relate to the process optimisation? The stationary phase is often explained by zero growth rates and nutrient depletion. The authors hypothesized that the observed upregulation of FNR during the stationary phase could be part of a strategic stress response. This represents a survival state triggered by stress, because when the cell enters a stationary phase under anaerobic conditions, it means energy is low and nutrients are scarce, resulting in a scarcity of electron donors. To avoid wasting energy, the cell can switch between aerobic and anaerobic metabolism, leading to the upregulation of FNR. The authors also noted that anaerobic growth using Fe3+ as an electron acceptor is slower and yields less energy compared to aerobic growth with oxygen. From this, we were able to transition from simply listing the genes that seem to be triggered by stress to actually gaining more insights into the genetic instructions in the form of expressed genes.

Proteomics serves as the essential link between an organism’s genetic potential and its function by verifying the actual mechanisms that occur during stress response activation. This can be observed through the direct assessment of cellular adaptation by quantifying the various proteins expressed under specific stress conditions. In a study by Bellenberg et al. [27], a comparative shotgun proteomics approach was used to explain the molecular basis of stress adaptation in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans when cultivated on pyrite. In their analysis, the researchers compared planktonic, iron(II)-grown cells to 5-day-old pyrite biofilm cells. This comparison revealed a thorough reconfiguration of the proteome, highlighting a strategic transition from a phase of active growth to one of stress management and metabolic modification. Biofilm cells showed a considerable increase in the expression of a diverse defense system against oxidative stress. This included a greater presence of proteins involved in detoxifying reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as peroxiredoxins; the preservation of redox balance in the cell through thioredoxins and related reductases; and the restoration of oxidative damage using DNA repair enzymes and molecular chaperones.

When it comes to further understanding cellular function, metabolomics provides an extensive view of cellular physiology, encompassing the diverse range of small-molecule metabolites that demonstrate the relation between a genotype and its environment. The groundbreaking metabolomic analysis conducted by Martínez et al. [28] on Chilean biomining strains Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans Wenelen and Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans Licanantay employed capillary electrophoresis coupled with mass spectrometry (CE-MS) to examine polar metabolites under different growth conditions, which included various energy sources (ferrous iron, elemental sulfur, chalcopyrite) and lifestyles (planktonic vs. sessile). This study offered valuable functional insights that complement genomic and proteomic data. One major finding was the widespread presence of the polyamine spermidine in both intracellular and extracellular samples, particularly in sulfur-oxidizing conditions. The absence of its usual precursor, putrescine, suggests the existence of an unusual spermidine biosynthesis pathway in these acidophilic organisms. The observed extracellular release of spermidine in the presence of solid sulfur substrates suggests a possible involvement in biofilm formation and intercellular communication, making it a potential marker for sulfoxidizing activity. Furthermore, the study confirmed the important role of glutathione, a crucial activator of elemental sulfur, which was identified as one of the most abundant intracellular metabolites in A. thiooxidans. The metabolic profiles also displayed condition-dependent variations in amino acid levels, with glutamic and aspartic acid being notably abundant both within the cells and in the supernatant, likely associated with their functions in the extracellular matrix and detoxification processes. Thus, this metabolomic snapshot substantiates and enhances genomic predictions by directly linking metabolic conditions to adaptive mechanisms such as biofilm formation, energy source utilization, and management of oxidative stress in extreme bioleaching environments.

The sequential use of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics offers powerful, multilayered insights into acidophilic bioleaching bacteria that no single method can provide. The genome of Acidithiobacillus spp. reveals their built-in potential abilities for iron and sulfur oxidation, metal resistance, and carbon fixation [34]. Building on this, transcriptomics work like that of Osorio et al. [26], shows how these bacteria finely tune their genetic activity to reveal that key genetic switches, such as the FNR regulator, are not merely present but are precisely upregulated during anaerobic, stationary-phase growth, to smoothly switch between aerobic and anaerobic respiration. Proteomics by Bellenberg et al. [27] revealed which genes and transcripts translate to activity, highlighting that biofilm cells on pyrite actively produce a targeted set of proteins for defending against oxidative stress, including peroxiredoxins, thioredoxins, chaperones, and globins, which free-floating cells (planktonic cells) do not. Finally, metabolomics research like the work of Martínez et al. [28], captures the actual chemical players involved, identifying key functional metabolites such as spermidine and glutathione that are actively produced and secreted to facilitate biofilm formation and sulfur oxidation.

The main takeaway from this comprehensive perspective is that biological information flows in a specific direction, and regulation at each stage (transcriptional, translational, post-translational) creates a gap between genetic capabilities and metabolic functions. While an organism may possess the genes for a stress response, only a multi-omics approach can confirm whether these genes are transcribed, translated into functional proteins, and ultimately result in a protective metabolic state. These insights are game-changing for industrial optimization, allowing a shift from a black-box approach to a more systematic engineering strategy. For example, identifying oxygen-stable FNR or crucial oxidative stress proteins in biofilms highlights targets for genetic modification or the selective enhancement of more resilient strains. The identification of spermidine as a biomarker for biofilm development on sulfur could facilitate the real-time monitoring and optimization of the health and activity of bioleaching consortia. Ultimately, a systems-level comprehension enables the prediction of microbial behavior under varying industrial conditions, such as oxygen gradients, nutrient shortages, and metal toxicity, leading to the design of smarter, more efficient, and controlled biomining processes based on a deep comprehension of the microbial mechanisms involved.

3.2. Case Study 2: Uncovering the Multi-Layered Metal Resistance Response of Trichoderma Asperellum Through Integrated Transcriptomics

In the above example, a well-known bioleaching bacterium was used to illustrate how studies conducted over decades can be linked to optimize a specific process. In this section, an emerging bioleaching fungus is used to illustrate the importance of integrated multimodal omics, rather than the well-known Aspergillus niger. This section illustrates the ongoing progress in research, where other emerging bioleaching fungi, such as Trichoderma asperellum, are being explored in relation to bioleaching.

The traditional methods for fungal bioleaching optimisation relied mostly on monitoring physiological conditions, such as pH drop and metal recovery [20]. Although this approach confirms bioleaching activities, it provides limited insights into the important metabolic activities that result in changes in the monitored physiological conditions. The drop in pH during fungal bioleaching is attributed to their ability to produce organic acids. Previous studies have focused on identifying the optimal carbon source for high organic acid production and their quantification. Such studies successfully provided a link between bioleached metals and the type of organic acid involved. However, such studies fail to provide further insights into metabolic and genetic activities. In our previous study, Nkuna and Matambo, [20], in addition to the known physiological conditions, multi-omics approaches, including metabolomics and transcripomics, were employed to investigate the metabolic activities of T. aspereallum during bioleaching. This was essential in revealing that the bioleaching efficiency was not just a consequence of a stress-induced response, but rather a result of a partitioned response, that is, the constitutive production of leaching agents coupled with a highly inducible cellular defense system.

The application of metabolomics in this study identified the main organic acids involved in the bioleaching process. Oxalic acid, identified through HPLC, was observed as the dominant leaching agent (>930 mg/L in the two-step bioleaching). Although this established “what” of the primary leaching mechanism, the “why” and the “how” were still not established. Metabolomics could not explain why organic acid production remained stable despite increasing metal concentrations during bioleaching.

The “why” and the “how” were answered by transcriptomics, which showed the genetic reprogramming of T. asperellum. De novo RNA-Seq data analysis of RNA extracted during the bioleaching process [20] revealed no differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to organic acid biosynthetic pathways in all the different bioleaching methods that were employed. This indicates that the production of organic acids in this fungus is a constitutive trait. It was not upregulated as a stress response in the presence of metals but remained a stable metabolic output based on the available carbon source. This then provides the “why” in terms of continuous production of organic acids. Looking closer at genes linked to metal tolerance, the fungus clearly adjusted its genetic activities to defend itself against metal stress. As a result, a significant upregulation of pathways related to cellular structure and ion management was observed. The transcriptomics data show that T. asperellum focuses its adaptive energy on protecting its cellular integrity when facing metal stress, while keeping its organic acid production stable and independent from these stress responses.

The understanding gained from this integrated multi-omics approach provides a clear roadmap for process optimization in T. asperellum. This study demonstrated that organic acid production is a constitutive trait that is not interrupted by metal stress, since the organisms can manage metal stress without affecting organic acid production. This means that optimisation should revolve around creating favourable conditions for fungal growth and organic acid production. Furthermore, understanding that metal tolerance is a transcriptionally inducible defense mechanism enables the targeted improvement of metal tolerance in specific strains. However, more research is required, particularly using RT-PCR to verify and accurately quantify the expression of these genes.

The focus on T. asperellum, rather than the well-studied fungal bioleacher Aspergillus niger, is intentional. A. niger is known for producing a lot of organic acids, especially citric and gluconic acids. These acids are key in metal solubilisation and have been widely used in bioleaching and biorecovery. Most studies on A. niger have linked metal leaching to acid production responses in different environmental conditions. In contrast, our integrated omics analysis shows that T. asperellum uses a different strategy. It produces organic acids, mainly oxalic acid, as a constant process. This is paired with a metal tolerance response and cellular defence that can be triggered by transcription. This separation between leaching activity and stress adaptation reveals significant differences between these fungi. It also highlights the importance of studying new bioleaching species like T. asperellum, especially regarding process stability and specific strain improvement.

4. Bioinformatics & Computational Tools (Second Major Section)

4.1. Tools for Data Analysis

Multi-omics technologies generate large amounts of data that require strong computational systems for analysis. Over the years, bioinformatics tools have evolved from basic sequence analysis like BioEdit, to complex platforms that enable the annotations of genomes along with metabolic modelling, the prediction of complex microbial interactions, and statistical analysis [35,36,37]. This conversion of raw data into significant output provides insights that can be used to optimize processes such as bioleaching. To accomplish this, various specialized tools are designed for different purposes, such as quality control and functional annotation. A few of these specialised bioinformatics tools are described below. It is important to note that this summary describes common practices and tools; for any specific application, researchers should consult the cited references and the latest software documentation for appropriate versions and parameters.

4.1.1. Genomics: Assembly, Annotation and BGC Discovery

The foundation of any multi-omics approach is dependent on high-quality sequence data, in this case high-quality genome sequences. The methodology for reconstructing genomes as a blueprint for gene cataloguing, that is, genome assembly and annotation, follows related principles that can be separated into distinct strategies to cater to different kingdoms, such as bacteria or fungi [38,39,40]. This is due to the variation in the genomic structure and complexity.

Bacteria

As an established area of study, bacterial genomes are usually small (1–10 Mbp), haploid, and consist of a single chromosome with low repetitive sequences [41]. This results in a straightforward analysis that simplifies the entire workflow, from sequences to analysis. Genomes, either from DNA extracted from pure bacteria or the environmental sample, are sequenced through whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and shotgun metagenomics, respectively, using either short or long reads (Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) or PacBio (Menlo Park, CA, USA)) [42,43].

The workflow normally starts with a quality control process using tools like FastQC and MultiQC followed by trimming of adapters through Trimmomatic or Cutadapt [44,45]. The next step is assembly, that is, the reconstruction of the genome, where the choice of tools depends on the sequencing technology used (short-read Illumina or long-read PacBio) [40]. For example, SPAdes is used for assembling short reads generated from Illumina, whereas Flye is primarily used for assembling long reads from PacBio [46].

The next step following assembly is annotation, where the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline or Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology (RAST) are known as highly effective for bacterial genomes. The outcome of annotation is the prediction of gene function, dependent on identifying open reading frames (ORFs) and Shine-Dalgarno sequences [46,47]. Databases such as Pfam, TIGRFAM, and COG are used to assign functional annotation for the sequences of interest [40]. For bacterial communities involved in metal bioleaching, this involves the specific annotation of metabolic pathways involved in redox reactions, such as cytochrome c for iron oxidation in Acidithiobacillus and genes for metal resistance (e.g., for arsenic, copper, cadmium) [29].

Moving beyond these foundational steps, more advanced workflows now incorporate these annotations into extensive comparative genomic frameworks, enabling the exploration of the genetic basis of ecological strategies and lifestyles. For example, the bacLIFE workflow, as described by Guerrero-Egido et al. [40] automates this procedure by grouping predicted genes into functional families across numerous genomes, resulting in a pan-genomic view. It subsequently uses machine learning on these gene clusters to predict bacterial lifestyles, such as pathogenic versus beneficial, and statistically identifies Lifestyle-Associated Genes (LAGs). This provides a powerful, hypothesis-generating tool for correlating genomic content to ecological function.

Bacteria contain Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) that code for pathways responsible for producing secondary metabolites like siderophores (e.g., pyoverdine), which are important for metal chelation and uptake. Tools like antiSMASH have become essential for predicting BGC in bacteria. They work by identifying conserved biosynthetic genes (e.g., Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases and polyketide synthases) along with their genomic context, enabling the rapid association of genetic potential with specific metal-chelating molecules [40]. Advanced pipelines like bacLIFE build on this by combining antiSMASH with tools like BiG-SCAPE to group BGCs into gen cluster families (GCFs). This allows for the linking of these clusters across datasets with specific bacterial lifestyles, revealing secondary metabolites that are crucial for adapting to specific environments, such as newly identified NRPS clusters involved in phytopathogenicity [40].

Fungi

Analysing fungal genomes is complex because it is characterized by large sizes, introns, repetitive DNA, and often diploid or polyploid states, demands a more computationally intensive and evidence-driven bioinformatic approach different from standard straightforward bacterial pipelines [48]. As a result, specialised tools have been developed to tackle these challenges, which include the comprehensive platform like FungiDB and the public health-focused TheiaEuk pipeline [48,49].

While familiar tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic are used for initial quality control ad trimming, the workflow shifts afterwards. Bacterial analysis often depends on short-read assemblers like SPAdes, which TheiaEuk employs for its speed in public health contexts [48]. However, assembling fungal genomes presents a greater challenge due to their larger size and high repetitive DNA, making reliable assemblies from short reads alone difficult. As a result, the use of long-read sequencing technologies has now become essential. Assemblers specifically designed for handling noisy long reads and large genomes, such as Canu and Flye, play a crucial role in generating more complete and continuous fungal genome assemblies [46]. The resulting assembly is often further improved (“polished”) using Illumina data with tools like Pilon [48]. The primary goal is to achieve high contiguity (high N50 values) to span entire genes and gene clusters, a prerequisite for accurate annotation that databases like FungiDB rely on for their integrated genomes [48,49].

Predicting fungal genes presents a significant challenge because of the presence of introns, a characteristic absent in most bacteria. While tools like MAKER2 and Funannotate demonstrate high effectiveness, they primarily depend on external evidence [50]. FungiDB shows this by incorporating extensive RNA-Seq data to refine gene models, as well as offering the Apollo genome editor for community-driven manual curation based on this evidence [49]. The most accurate annotations incorporate multiple lines of evidence, including transcriptomic evidence (RNA-seq), protein homology, specialized identification, and typing.

Mapping RNA-seq data to the genome using aligners such as HISAT2 or STAR offers valuable insights into exon-intron structures, thereby significantly improving the accuracy of gene predictions. This process is an essential aspect of the FungiDB transcriptomics workflow and is used to facilitate searches for “Unannotated Intron Junctions” [48,49]. Beyond transcript data, information from proteomes of closely related fungi is used to guide and verify these predictions. Platforms like FungiDB utilize orthology groups (e.g., through OrthoMCL) to make functional inferences across different species [48,49]. Functional annotation is then carried out by comparing sequences against both broad databases (e.g., InterProScan, eggNOG-mapper) and fungal-specific databases (e.g., FunCat, JGI MycoCosm), which are central to the annotation capabilities in FungiDB [48,49].

Fungi have their own unique BGCs responsible for the production of compounds like siderophores (e.g., ferrichrome) and mycotoxins. Although the general principle for studying these clusters is similar to that used in bacterial analysis, the tools are specially adapted for fungi. For example, antiSMASH has a dedicated fungal version called fungiSMASH, which focuses on recognizing fungal-specific core biosynthetic genes (e.g., iterative PKSs and NRPSs) and the unique architecture of fungal BGCs [51]. FungiDB is actively developing a dedicated secondary metabolite search to complement these tools, highlighting the specialized need for BGC analysis in fungi [52].

4.1.2. Transcriptomics: Differential Expression Analysis

As mentioned above, transcriptomics moves beyond the genomic blueprint to provide an overview of the activity of microorganisms through the quantification of the entire set of RNA transcripts. This approach is crucial for understanding how bioleaching microorganisms adjust their gene expression in real-time as a response to an extreme bioleaching environment. By identifying Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs), scientists can identify essential genetic pathways that are activated for the production of energy, stress resistance, as well as interaction of the microbial community.

The standard pipeline for analysing high-quality RNA-seq reads involves their alignment against a reference genome through tools such as Bowtie2 or BWA, followed by counting reads per gene [53]. The next step is to use tools such as DESeq2 and edgeR in R/Bioconductor for statistical analysis [54]. This provides a robust negative binomial model that accounts for biological variability and accurately identifies significant DEGs. This approach has been successfully applied to RNA obtained from pure cultures and complex communities to elucidate the molecular basis of bioleaching efficacy [20,25]. For example, in the bioleaching model bacterium A. ferrooxidans, transcriptomics has revealed how the organism copes with specific stressors. In a study by Tang et al. [55], it was observed that under high magnesium stress, a significant obstacle in processing certain ores, DEG analysis indicated a down-regulation of genes related to Type IV Pili (which affects biofilm formation and attachment) as well as critical enzymes in the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle (hindering carbon fixation), thereby directly linking gene expression with observed physiological inhibition.

In more complex, synthetic consortia, metatranscriptomics revealed a well-coordinated division of activities among the organisms. A study by Ma et al. [25], used six-strain consortia and observed a temporal shift in gene expression during the adaptation phase, where genes for catalytic activity and binding were upregulated to initiate the process. As the condition became increasingly toxic in the later stages, the gene expression of the consortia shifted towards a stress response to sustain functionality and cope with the toxic conditions.

For eukaryotic microorganisms, such as fungi, RNA-seq analysis follows a fundamental workflow similar to that of bacteria, but it requires specific tools to effectively process spliced transcripts. A recent comprehensive study conducted by Jiang et al. [53] on plant pathogenic fungi offers valuable insights for improving this process. The process starts with trimming reads with fastp, where parameters are selected based on the data characteristics. Reads are then aligned to a reference genome using HISAT2, a tool selected for its good balance of speed and accuracy. Gene-level quantification is typically performed using alignment-based tools, such as featureCounts, which have demonstrated strong performance. The next step involves the statistical analysis of identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs), for which DESeq2′s parametric fitting method is recommended due to its robustness across fungal datasets. Beyond constructing a custom pipeline, integrated platforms like FungiDB compile pre-processed differential expression outcomes, enabling researchers to investigate, for instance, genes that are upregulated under metal stress [49,52]. Regardless of the organism’s kingdom, the precision of transcriptomic analysis relies entirely on a high-quality, thoroughly annotated genome, highlighting the essential role genomics plays in the multi-omics approach.

4.1.3. Proteomics and Metabolomics

Moving beyond transcriptional analysis, proteomics and metabolomics provide a more immediate insight into the proteins and small molecules that actively drive microbial functions. In bioleaching, this involves directly observing the enzymes and chemical agents that facilitate the solubilization of metals [56]. Proteomics enables the quantification of all protein sets expressed under specific conditions, with MaxQuant playing a significant role. MaxQuant is an advanced, powerful software suite that processes high-resolution mass spectrometry data to identify and quantify peptides and proteins [57]. It features advanced algorithms for precise feature detection, mass calibration, and robust statistical analysis, all of which are required for complex microbial samples. In bioleaching studies, MaxQuant has been instrumental in identifying and quantifying key enzymes, such as rusticyanin in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, and fungal laccases, confirming their enhanced production in response to metal substrates and underscoring their crucial roles in bioleaching [21,58,59]. To assist in the interpretation of MaxQuant results, platforms like ProVision offer user-friendly statistical tools and visualization options that are accessible to even those without expertise [60].

Equally, metabolomics characterizes the small molecule that results from cellular processes. The Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform is a cornerstone for analysing tandem mass spectrometry data, enabling the construction of “molecular networks” that cluster metabolites based on the similarity of their MS2 fragmentation spectra [61]. By classifying structurally related compounds, this method not only speeds up the dereplication of known molecules but also visually directs the discovery of new metabolites [62]. As an open-access knowledge base, GNPS makes use of crowdsourced curation of reference MS libraries and community-wide organization to create a “living data” ecosystem, where deposited data is continuously reanalyzed as libraries grow [61]. Advanced GNPS workflows such as Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN) can resolve isomeric compounds in bioleaching consortia, while Ion Identity Molecular Networking (IIMN) unifies various ion adducts of the same metabolite, to make the chemical landscape more understandable [62]. By identifying important microbial metabolites like novel siderophores or organic acids, these tools can establish a direct connection between the compounds produced and the genomic predictions made by antiSMASH. GNPS is an effective tool for linking genetic potential with observed biochemical activities because of its growing suite of annotation tools, such as SIRIUS and MolNetEnhancer, as well as its community-driven spectral library and continuous identification capabilities [61,62].

4.2. Modelling and AI

4.2.1. Metabolic Modelling

Metabolic modelling is a powerful computational approach that uses an organism’s genetic information to predict its physiological abilities, making it an effective tool for optimizing bioleaching strategies. The primary methodology employed is Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA), which enables the construction of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) [63,64]. These models represent the entire metabolic network mathematically, allowing simulations that predict growth rates, nutrient requirements, and the importance of specific genes or reactions under various environmental conditions [65].

The complexity and application of GEMs differ across biological kingdoms. In bacteria, the COBRA methodology is well-established. Automated systems, such as KBase, can quickly produce and analyze preliminary GEMs directly from genomic sequences. For bioleaching microorganisms, such as Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans, these models have facilitated the identification of optimal energy sources and significant metabolic trade-offs, including the allocation of resources for synthesizing metal-chelating compounds, which directly influence cultivation methods [66].

Fungal GEMs, as compared to bacterial GEMs, are inherently more complex due to larger genomes and compartmentalization within cells (e.g., mitochondria, peroxisomes). Despite this, fungal GEMs provide essential insights for industrially important processes, such as predicting citric acid yield in Aspergillus niger, and mapping complex metabolic pathways like lignin degradation, in white-rot fungi. This capability allows for the in silico optimization of fungal bioremediation and bioleaching processes before laboratory testing [65,66].

4.2.2. Machine Learning for Predicting Microbial Interactions

Machine Learning (ML) has become an essential tool for unravelling the intricate, non-linear relationships that exist within microbial systems, a challenge that often stumps conventional statistical techniques. By examining multi-omics data, ML algorithms can reveal concealed patterns crucial for comprehending and forecasting microbial behaviour. Typical uses involve categorizing microbial functions and modelling complex interactions within consortia. For example, Random Forest algorithms are prized for their reliability and clarity in both classification tasks (such as predicting pathogenicity) and regression analyses (like forecasting biomass yield) [67]. On the other hand, more sophisticated Neural Networks and deep learning models excel at assimilating diverse data layers, like genomic, transcriptomic, and environmental information, to model complex microbial interactions [67].

The predictive capabilities of ML are particularly advantageous for designing and refining microbial consortia used in bioleaching [68]. In bacterial systems, models can forecast synergistic or antagonistic interactions based on metabolic pathway compatibility drawn from genomic information [69]. Likewise, for fungi, ML trained on co-culture omics data can predict interaction results, such as whether a bacterial partner enhances or inhibits fungal processes essential for metal mobilization, such as siderophore production [69].

This methodology is directly relevant to bioleaching, where ML is increasingly applied to optimize process parameters and estimate efficiency. A notable study by Mokarian et al. [70] evaluated 40 regression-based ML algorithms using a comprehensive dataset compiled from bioleaching research. Their findings indicated Random Forest Regression as the top-performing model, achieving an accuracy of 77% in predicting metal recovery rates. The analysis highlighted that the most significant variables influencing recovery efficiency included the type of resources (primary or secondary), particle size and density, temperature, and the microorganism involved [70]. This study provides a clear example of how ML is used in biomining. It shows how ML can model recovery results based on both operational and biological factors. In addition to predictive modeling, ML can also assist in other specific areas of biomining, such as predictive maintenance. This involves using sensor data from bioreactors, including pH, redox potential, dissolved oxygen, and temperature, to predict equipment failures or process issues [71,72]. In real-time optimization, the use of reinforcement learning enables the adjustment of aeration, nutrient feed, or pulp density based on real-time sensor data and microbiome information, thereby improving metal recovery [72]. In image analysis, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are employed to examine microscopic or satellite images. This analysis helps monitor microbial biofilm growth on ores or evaluate mineral changes during heap leaching.

By leveraging such data-driven approaches, machine learning can significantly reduce the need for costly and time-intensive experimental trials, offering an effective and economical means to guide the design and optimization of bioleaching operations. The experimental validation of these ML models in real industrial settings is an important next step. A proposed validation framework starts with testing models in controlled environments. This includes using trained algorithms in pilot-scale heaps or stirred-tank reactors at mine sites [73,74]. Historical operational data will serve for initial calibration. Next, there should be closed-loop testing by applying model recommendations, such as suggested optimal pH set-points, in parallel test cells or reactors [72]. During this time, control units will run under standard conditions. This setup allows for a direct comparison of key performance metrics, like metal extraction rates and acid consumption. Finally, to maintain long-term effectiveness and relevance, deploying continuous learning systems is crucial. This means integrating real-time data from on-site sensors with regular microbiological and geochemical sampling. These combined data streams will then retrain and refine the models on-site. This approach creates systems that improve over time by considering site-specific factors like ore differences and changes in the microbial community.

Although using ML to predict fungal–bacterial interactions, specifically in bioleaching, is still new, considerable foundational progress has already been made. Combining ML with multi-omics data is a growing trend, paving the way for predictive models that can enhance metal solubilization mechanisms and engineer more effective microbial consortia [67]. These collective studies highlight a robust synergy among ML, bioleaching microbiology, and multi-omics, advancing the field toward more sustainable and regulated bioprocesses for metal recovery.

4.3. Network Biology

Co-Occurrence Networks

Going beyond basic correlation analyses, co-occurrence network inference has become a strong bioinformatics method for suggesting possible ecological interactions, such as symbiosis, competition, or syntrophy, among complex microbial consortia. A significant innovation in this field is SPIEC-EASI (Sparse Inverse Covariance Estimation for Ecological Association Inference), a method tailored to address the statistical challenges associated with microbiome data, specifically its compositional nature and high dimensionality [75]. By creating networks based on conditional independence, SPIEC-EASI distinguishes between direct, potential interactions and indirect, misleading correlations. This offers a more reliable framework for understanding the structure of microbial communities [75,76].

The shift from network inference to its practical application is clearly shown in recent bioleaching studies. Kim et al. [76] evaluated a high-performing native microbial community from mine tailings using 16S and ITS amplicon sequencing. They used the SPIEC-EASI framework to create a co-occurrence network that revealed a closely connected group of bacteria (e.g., Leptospirillum) and fungi (e.g., Cadophora), suggesting a synergistic relationship. Furthermore, multi-omics analysis supported this hypothesis. Genomic investigation through bacLIFE and FungiDB showed that the fungus Cadophora was efficient in solubilizing the ore matrix by producing organic acids, whereas the bacterium Leptospirillum effectively oxidized ferrous iron, a crucial step in the bioleaching process. Importantly, this idea from the network was tested in practice. The researchers made a minimal synthetic consortium based on these key interacting species. This carefully designed consortium, informed by the SPIEC-EASI network, achieved a significantly improved bioleaching rate in comparison to randomly formed communities, demonstrating that network inference can actively guide the development of optimized biocatalysts for industrial use [76].

This comprehensive process, which includes high-throughput sequencing, robust network inference, genomic confirmation, and consortium engineering, represents the transformation in bioleaching. It shows how bioinformatics is evolving from a purely observational tool into a crucial part of a design–build–test cycle for environmental biotechnology.

5. Challenges

Environmental and industrial multi-omics face two broad classes of obstacles. The first are technical limitations that distort measurements or complicate cross-layer integration; the second are practical barriers that limit deployment and scale. This section summarizes the most common issues in plain language, links them to concrete consequences for inference and decision-making, and outlines feasible mitigation strategies for real-world projects. Multi-omics bioleaching workflows inherit both generic data-noise problems and layer-specific weaknesses. Table 2 and Table 3 provide a compact overview: Table 2 outlines typical cost ranges and planning levers for implementing each assay, while Table 3 summarises the main read-outs, advantages and technical limitations of each omics layer in bioleaching, which we expand on below under the umbrella of technical limitation.

5.1. Technical Limitations

Data Noise (e.g., Metagenomics in Low-Biomass Environments)

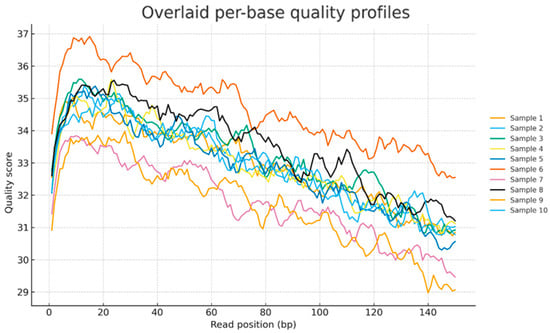

In matrices where genuine microbial material is scarce, for example, condensate, pore water, and clean-in-place residues, background DNA from extraction kits and reagents, the kitome, laboratory air and surfaces, host DNA or RNA, and barcode or index misassignment can rival or exceed the authentic signal. The result is unstable taxon or strain calls, exaggerated diversity, and false positives that vary across replicates [77]. To limit this, the study design requires paired field, extraction, and library blanks in every batch, together with a positive mock community to benchmark recall and precision. At the molecular level, spike-ins and unique molecular identifiers support molecule-aware quantification, reducing the impact of PCR duplication [78]. A further pitfall is the unadjusted mixing of single-end and paired-end libraries in one analysis. Process each type in parallel with compatible trimming and classification, carry library type as a covariate, normalise counts with size factors and an effective read length offset, base breadth metrics on sequenced bases rather than read counts, avoid co-assembly across types, and do not convert paired-end data to pseudo single end unless mates are dropped for all libraries. Read level quality control should pair concise diagnostics with targeted remediation. FastQC provides an overlaid report of per-base quality, GC bias, and over-represented sequences (as illustrated in Figure 2), but does not itself trim or deduplicate. Instead, it flags issues so that the correct preprocessing can be applied (Babraham Bioinformatics (Cambridge, UK), FastQC). Adapter and quality trimming should then be applied with established tools such as fastp, Cutadapt, Trimmomatic, or AdapterRemoval to remove residual adapters, trim low-quality tails, and, for paired-end data, merge overlapping mates to improve mappability [44,79,80,81]. Cross-species or reagent carry-over is best revealed early with mapping-based screens, such as the FastQ Screen, and downstream statistical contaminant filtering with decontam, which uses negative controls and frequency patterns to remove spurious signals [80,82,83]. Index or barcode misassignment during multiplexed runs can lead to low-level false positives; mitigation strategies include unique dual indexing, thorough removal of free adapters during cleanup, and computational correction where necessary [84,85,86]. When PCR duplication is a concern, UMI-aware deduplication improves quantification and reduces over-counting of short or GC-favoured fragments [78,87]. Even with rigorous blanks, UMI-aware deduplication, dual indexing, adapter and quality trimming, and prevalence-based filtering, low-biomass libraries remain vulnerable to residual contamination and compositional artefacts. Rare taxon calls and fine-scale functional claims should therefore be interpreted conservatively and validated across batches or by orthogonal assays such as targeted PCR or quantitative assays. Analytically, prevalence-based contaminant calling, conservative read classification thresholds, and treatment of counts as compositional reduce spurious correlation and improve comparability across libraries; centred log-ratio transforms, or appropriate size factor methods are preferred to rarefaction [82,88]. Where appropriate, host or background depletion or physical enrichment reduces non-target reads; CRISPR guided depletion can remove dominant sequences before sequencing and reclaim depth for informative molecules [89].

Figure 2.

Overlaid per-base quality profiles for ten samples. Phred scores by read position show high 5′ quality with a gradual decline towards the 3′ end.

5.2. Practical Barriers

5.2.1. Cost of High-Throughput Omics for Industry

The cost of industrial omics is not uniform. It is the sum of what the process needs, how many samples clear each quality gate, and how much rework you prevent by design. In modern industrial omics programmes, sequencing reagents are only one part of the bill. For small exploratory runs they can still dominate, sometimes accounting for roughly half of the direct spending, but as programmes scale into multi-year, multi-omics designs, the balance inverts: upstream biology (sampling, culturing, pilot reactors), quality control, validation experiments, data analysis, storage and governance typically consume most of the budget, with library kits and flow cells representing minority line items. In practice, the ratio shifts from reagent-heavy to analysis-heavy as teams add discovery-plus-confirmation tiers, multiple omics layers and tighter reproducibility requirements [84,90,91]. Since the early 1990s, when microRNA was first uncovered and later recognized with the 2024 Nobel Prize to Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun, per-unit sequencing costs have collapsed, while programmes have grown larger and more layered. The modern budget reflects that shift rather than a headline reagent figure [84,91]. Sequencing shows the fall most clearly. NHGRI’s long-running series documents orders-of-magnitude declines from the Human Genome Project era into the second-generation platforms after 2007 and through the 2010s. Vendors now advertise about two hundred US dollars per genome at full utilization on high-throughput systems, a number enabled by denser flow cells, faster optics, and refined chemistry, but that figure is a reagent base value. It does not include upstream biology, validation, computation, or compliance, which dominate industrial totals and vary with design and governance [84,91]. Proteomics has had a quieter but real throughput shift. Pre-formed-gradient chromatography made sixty samples per day a routine operating point without drastic losses in depth, and diaPASEF improved duty cycle and identification efficiency by coupling trapped ion mobility to data-independent acquisition. When instruments are booked well, the effective cost per informative sample falls, and reruns drop once QC is stable, which is where the savings are actually found [92,93]. Metabolomics has gained more from standardisation than from raw instrument discounts. The mzTab-M results format gives a shared way to report quantitative results and provenance, which cuts rework and allows for like-for-like comparison across sites. The value appears as fewer failed comparisons and cleaner review, rather than a dramatic fall in per-injection list prices [94]. What still poses a problem in 2025 is arithmetic. As unit prices drop, teams scale designs and add layers, for example through shallow discovery before deep confirmation, bulk before single-cell discovery, and proteomics before targeted panels. Storage and data movement accrue every month. Even at commodity cloud rates, S3 Standard is nearing two-point-three cents per gigabyte per month, and data-out charges become material at the terabyte scale, unless lifecycle policies are set from day one. Reproducibility has a cost as well, because without containers, pinned databases and a workflow engine, the same inputs can yield different outputs on re-runs, and you pay twice.

Table 2.

Per-assay cost ranges and planning levers for common omics workflows in the South African industry (2025 ZAR).

Table 2.

Per-assay cost ranges and planning levers for common omics workflows in the South African industry (2025 ZAR).

| Analysis | Primary Cost Driver (Why) | Unit | Cost Range (ZAR) | Planning Lever (Keep Cost Down) | Published Manuscripts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-genome sequencing, short read | Flow-cell allocation and library kit; depth chosen | per 100 M read-pairs | R4600–R5000 | Fill lanes, right-size depth, standardise library kits | [95] (NGS overview) (PMC) |

| Shotgun metagenomics, short read | Run share at moderate depth; contamination control drives reruns | per 50–100 M read-pairs | R3000–R7000 | Batch hard, predefine evidence rules, include blanks and mocks | [83] (low-biomass contamination) (PubMed) |

| Bulk RNA-seq | Library chemistry plus reads; depth targets | per sample (20–30 M pairs) | R3500–R5500 | Pilot to set depth, multiplex to full lanes | [96] (RNA-seq best practice) (BioMed Central) |

| Single-cell RNA-seq (10×) | Barcoding and reagent kits; captures per lane | library-prep only, per well | R30,000–R60,000 | Right-size cells per lane, pool libraries before sequencing | [97] (method comparison) (ScienceDirect) |

| Whole-genome sequencing, long read (ONT) | Flow cells and ligation kits; yield per cell | per PromethION flow cell | R15,000–R18,000 | Match flow-cell count to target coverage; multiplex where valid | [98] (long-read at scale) (PMC) |

| LC–MS/MS proteomics (label-free) | Instrument time and columns; gradient length | per injection/sample | R3000–R9500 | Use high-throughput gradients; plate scheduling | [92,99] (high-throughput) (PMC) |

| Untargeted LC–MS metabolomics | Instrument time, columns, solvents | per injection/sample | R2500–R3200 | Pooled QC, internal standards, shorten gradients if acceptable | [100] (large-scale workflows) (PubMed) |

| Targeted LC–MS/MS metabolomics (MRM/PRM) | Stable-isotope standards; method setup | per injection/sample | R2000–R6000 | Fix transition lists, multiplex targets, short routine runs | [101] (targeted metabolomics review) (PMC) |

| GC–MS metabolomics | Derivatisation kits and columns; oven time | per injection/sample | R2000–R3000 | Batch derivatisation; keep column health to avoid reruns | [102] (GC–MS metabolomics) (PubMed) |

| NMR metabolomics | Magnet hours and cryoprobe time | per hour | R300–R1200 | Automate queues; fixed pulse sequences | [103] (NMR metabolomics review) (PMC) |

Rights also impact pathway resources, such as KEGG, which require a commercial license for non-academic use, and version pinning is essential to avoid annotation drift and audit friction [104,105]. The way to keep budgets honest is to design for the decision and stage the assays. Carry out a small pilot up front to estimate variance, failure modes and practical pass rates, and then determine the right depth and throughput. Use a screen-then-escalate pattern so that fixed spend becomes conditional spend: shallow metagenomes before deep, bulk RNA-seq before single-cell investigations, discovery proteomics before targeted PRM or SRM, and untargeted metabolomics before focused panels. Enforce dual indexing, balance pools by molarity, stop failed libraries before they hit expensive run space, and publish pass rate by gate so that everyone can see where rework comes from. For capacity choices, present a simple break-even: the annual fixed cost of in-house divided by the spread between the service price and your variable per-unit cost gives the volume where it pays to build rather than buy. Then ground the choice with your local ranges in Table 2 so that the decision is visible in rand. Over the next two years, short-read costs per base will drift down rather than collapse, proteomics will continue to push more samples into the day as high-throughput methods standardise, and metabolomics will keep improving through standards and QC rather than hardware discounts. The main savings for industry will come from process discipline and evidence-led study design, not from a surprise in a press release [91,92,93].

Table 3.

The main advantages and limitations of each omics layer when applied to bioleaching.

Table 3.

The main advantages and limitations of each omics layer when applied to bioleaching.

| Omics Layer | Main Read-Out in Bioleaching | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations | Typical Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metagenomics (shotgun) | Community composition, gene and pathway potential | Captures uncultured organisms; resolves metal-resistance and energy-metabolism genes; supports strain-level tracking | Sensitive to kitome and background DNA; compositional bias; depth and assembly demands; annotation incomplete for bioleaching taxa | Field and extraction blanks, mock communities, UMI/dual-indexing, compositional statistics, conservative thresholds |

| Meta-transcriptomics | Active genes and pathways under process conditions | Links expression of sulfur/iron oxidation, stress and metal-transport systems to operating variables; good temporal resolution | RNA instability; strong batch effects; host/abiotic RNA background; requires higher depth and careful normalisation | Rapid preservation, rRNA depletion, balanced designs, spike-ins, robust normalisation (e.g., size factors) |

| Meta-proteomics | Enzymes and complexes actually deployed | Direct evidence of secreted oxidases, transporters and stress-response proteins; closer to phenotype | Complex sample prep; dynamic range limits; database and FDR constraints; lower throughput and higher cost | Standardised extraction, high-throughput gradients, curated databases, pooled QC samples and retention-time alignment |

| Metabolomics | Small molecules, ligands and metal–organic complexes | Captures leachate chemistry, redox couples, organic acids and biosurfactants; readout closest to process performance | Matrix effects, ion suppression, compound identification gaps; instrument drift across campaigns | Internal standards, pooled QCs, retention-time libraries, mzTab-M reporting, careful batch correction |

| Geochemistry and process data | pH, redox potential, metal concentrations, temperature, flow and aeration | Direct operational context; essential for scaling and control; anchors omics signals to engineering variables | Different sampling frequencies and error structures from omics; often stored separately from molecular data | Co-designed sampling plans, shared identifiers and metadata, joint models that link process variables to multi-omics read-outs |

5.2.2. Regulatory Gaps for Genetically Engineered Strains

Rules for industrial use of engineered microbes remain uneven across jurisdictions, and the absence of harmonised minimum requirements raises direct costs and time. Scope and definitions differ in ways that change approvals and evidence. England’s Precision Breeding Act creates a pathway for defined precision-bred organisms in plants and vertebrate animals outside the general GMO regime. The Court of Justice of the EU held in 2018 that organisms obtained by targeted mutagenesis fall within the GMO Directive. South Africa continues to treat most gene-edited products as GMOs. Similar strains, therefore, face different routes, timelines, and study expectations across markets. Evidentiary minima are weakly specified. The EU contained use regime classifies work with GM micro-organisms by risk class but leaves many details to competent authorities and guidance. EFSA’s guidance for food and feed production organisms sets expectations for identity, genetic stability, and acquired traits such as antimicrobial resistance; however, it does not establish universal thresholds for sequencing depth, structural variant resolution, copy number, or residual vector screening. In the United States, the EPA’s TSCA programme requires MCAN or TERA submissions with detailed information on the construct, host, containment, and monitoring; however, prescriptive technical floors are limited. The result is a fragmented view of what counts as proof of identity, stability, and absence of unintended integrations.

Environmental risk assessment and monitoring show similar gaps. The Cartagena Protocol sets general principles for risk assessment of living modified organisms, and the EU deliberate release regime requires post-market environmental monitoring with case-specific studies and general surveillance. In practice, methods, sampling designs, and escalation triggers still vary across dossiers and countries, which reduces comparability and increases rework. Change control and transparency are also under-specified. Industrial strains often evolve during process development, yet few regimes define what constitutes a material change, which elements must be re-evaluated, or how to demonstrate comparability across iterations. Requirements for sequence deposition and metadata are variable, and policy on digital sequence information is in flux as Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity move toward a multilateral benefit-sharing mechanism. These gaps do not require reinvention to fix. Regulators could converge on a risk-proportionate minimum package built on three pillars: identity and stability, function, and biosafety. For identity and stability, set clear, auditable minima for sequence confirmation, copy number and structural variant analysis, residual vector screening, and demonstration of stability through scale-up and stress passage. For function, define acceptable evidence that engineered pathways perform within agreed operating ranges. For biosafety, standardise methods and acceptance metrics for containment, horizontal gene transfer potential, and performance of kill switches or auxotrophies, and require simple, comparable post-deployment monitoring where environmental exposure is possible. Change control should include predefined triggers and comparability rules. Data and traceability should reference agreed deposition formats and metadata. Two mature references already point the way: the OECD Council Recommendation on safety considerations for recombinant DNA applications, which embeds Good Industrial Large-Scale Practice for intrinsically low-risk organisms, and ISO 35001:2019, Biorisk management for laboratories and other related organisations, on biorisk management, which provides a process standard suitable for certification. In practice, internationally harmonised minimum evidence standards could be built in a small number of concrete steps. First, regulators and standards bodies could co-develop a shared technical annex that specifies a baseline genomic package for industrial strains: short-read whole-genome sequencing at defined coverage, long-read or equivalent methods above a construct-size threshold, explicit copy-number and structural variant calls, residual vector screening, and a documented search for off-target changes at nominated loci using agreed bioinformatic pipelines. Second, this annex should be expressed as a risk-tiered checklist aligned to the three pillars of identity and stability, function, and biosafety, so that intrinsically low-risk chassis in contained use face lighter requirements than open-release or pathogenic strains, while maintaining common minimum floors. Third, implementation should be supported by shared reference materials, inter-laboratory ring trials and standardised reporting templates, allowing competent authorities to recognise equivalent evidence generated in other jurisdictions rather than re-running studies locally. Building these annexes onto existing frameworks such as OECD recombinant-DNA guidance and ISO biorisk standards would enable convergence without reopening entire statutes. Finally, regulation, ethics, and biosafety are essential, but they can also slow down deployment. Human-associated data require consent, privacy safeguards, and controlled access. Work with engineered strains or industrial bioprocesses often needs risk assessments, facility approvals, validated assays, and documented change control. Many rules were written for single, well-characterised isolates rather than complex or evolving consortia. Guidance is thin on validating omics-based assays for lot release, in process monitoring, and environmental surveillance, where engineered and wild-type backgrounds overlap. Reference materials for engineered strains in mixed metagenomes are scarce, which makes it challenging to evidence the limit of detection claims and cross-site comparability. Boundaries between contained use and environmental release are interpreted differently for pilots and wastewater, which feeds uncertainty on permits, biosafety levels, and reporting. Data governance is also moving. The CBD’s Decision 16/2 created the Cali Fund for benefit sharing on digital sequence information, but implementation and national uptake are still settling. Responsibilities can be diffuse when design, build, test, and analytics are split across contractors, with unclear expectations for change control, assay validation, and incident reporting in mixed microbiome settings. The net effect is slower deployment and higher compliance risk even when technical performance is sound [106,107,108].

6. Future Perspectives

6.1. Emerging Technologies

Looking at developments, four emerging technology families appear most likely to shape bioleaching over the next decade. First, genome-resolved community sequencing that couples bulk shotgun metagenomics with long reads and proximity-ligation (Hi-C) will deliver stable, strain-level reconstructions of leach communities. Second, single-cell and single-nucleus omics will resolve intra-consortium heterogeneity and developmental trajectories that bulk profiles average away (Section 6.1.1). Third, CRISPR-based engineering of keystone strains and minimal synthetic consortia, guided by multi-omics data, will enable deliberate tuning of stress tolerance, energy metabolism and cross-feeding (Section 6.1.2). Fourth, the integration of online sensors, multi-omics read-outs and machine-learning “digital twins” promises closed-loop control of bioleach performance in real time.

6.1.1. Single-Cell Omics to Resolve Consortium Heterogeneity

Single-cell methods can reveal structure that bulk omics averages away, but they only pay off in environmental and industrial matrices when applied with a narrow brief. In practice, single-cell genomics is helpful when a minority population cannot be cleanly distinguished from metagenomes. Flow sorting or microfluidics followed by whole-genome amplification can recover near-complete genomes and plasmids that anchor function and mobile elements; because coverage bias and chimeras are common, multiple cells from the same taxon are often co-assembled and then validated against bulk assemblies and read mapping [109,110,111,112,113]. When the aim is to resolve activity rather than genotype, proximity-ligation metagenomics such as Hi-C can achieve the same practical outcome at community scale, stabilising bins from a single bulk sample and linking phages and plasmids to hosts without isolating individual cells [114,115].

In extremely acidic, metal-rich environments such as bioleach liquors and acid mine drainage, single-cell workflows are technically feasible but require additional handling. Acidophiles maintain a near-neutral cytoplasm, so once cells are gently transferred into isotonic, buffered media, standard FACS- or microfluidic-based single-cell genomics protocols can be applied. Studies of omics in acid mine drainage and other extreme environments show that single cells or small consortia can be recovered and sequenced from such matrices, but low biomass, high metal loads and rapid RNA degradation mean that DNA-based single-cell genomics is currently more realistic than routine single-cell transcriptomics in strongly acidic industrial systems.

In applied settings the goal is not a comprehensive census but a defensible map from mixture to development ordering by gene expression (Figure 3). After enrichment for the population of interest (by size selection, FACS, microfluidics, or nuclei isolation), single-cell libraries are processed under an explicit QC contract: minimise dissociation artefacts by keeping processing as gentle and as cold as practicable, remove barcodes dominated by ambient RNA, exclude doublets, and retain cells with sufficient detected genes and acceptable mitochondrial/rRNA fractions [26,116,117,118,119,120,121].

Figure 3.

(A) Mixed tissue with diverse cell types. (B) Early/progenitor subset isolated or computationally enriched. (C) Cells arranged in low-dimensional space and ordered along trajectories, revealing intermediates. (D) Terminal, lineage-specific outcomes (e.g., erythroid, epithelial, neuronal). Arrows indicate progression from progenitor → intermediate → mature states.

Normalisation and feature selection are followed by batch integration where needed, after which a low-dimensional embedding (UMAP/t-SNE) and graph clustering expose discrete states that bulk profiles would average away. Marker-guided annotation is then cross-checked against metagenome-assembled genomes or single-cell genomes from the same matrix to ensure taxonomic and functional coherence, with proximity-ligation (Hi-C) used again to stabilise bins and link mobile elements to hosts from bulk material [109,110,114,122,123].