Abstract

The construction sector is progressively prioritizing environmental norms owing to its substantial role in carbon emissions from clinker manufacture. Industrial waste materials are increasingly used as alternative constituents in cement-based systems, garnering interest as a sustainable strategy. Ceramic waste powder (CWP), produced in substantial quantities with enduring properties, offers a viable alternative. Nonetheless, its elevated water absorption presents issues, requiring modification procedures such as hydrophobization and the use of nanosilica to enhance performance. This study assessed CWP in both raw and modified forms (ground and hydrophobized) as a partial aggregate replacement in concrete. A silane-derived chemical was employed for hydrophobization, with varying amounts of nanosilica. Recent mortar testing encompassed setting time, flow, and density. Durability was evaluated using capillary water absorption, and flexural and compressive strengths were quantified at 2, 7, and 28 days. Mineralogical and microstructural investigations were conducted utilizing XRD and FTIR to monitor hydration phases and reaction processes. Results indicated that unmodified CWP containing up to 1% (wt) nanosilica enhanced mechanical strength; however, elevated nanosilica concentrations diminished early strength. Hydrophobized CWP samples demonstrated improved early strength with nanosilica levels up to 0.5% (wt), but strength diminished at elevated concentrations. Microstructural analysis confirmed reduced portlandite levels and increased C–S–H production, thereby validating the progress of hydration. The regulated and altered application of CWP with nanosilica can improve mechanical performance and durability while promoting ecological sustainability in cement-based systems.

1. Introduction

The growing global population and the associated demand for accommodation lead to an increase in the number of buildings and, consequently, the consumption of cement and cement-based construction materials worldwide. The global environmental circumstances, particularly carbon emissions, have attained dangerous levels [1,2,3].

The manufacture of cement significantly contributes to global carbon emissions. It constitutes roughly 6%–8% of total global emissions, rendering it one of the principal industrial emitters of greenhouse gases. The cement production process entails the thermal breakdown of limestone (calcium carbonate) into lime (calcium oxide) and carbon dioxide, resulting in substantial CO2 emissions. Furthermore, the combustion of fossil fuels achieves the necessary elevated temperatures for production, thereby intensifying emissions [4]. The rising urbanization and population expansion are anticipated to elevate the demand for construction materials, thus raising the carbon footprint of cement production. Initiatives to mitigate emissions encompass the development of alternative materials, enhancement of energy efficiency, and implementation of carbon capture systems [5].

The ceramics sector predominantly generates emissions due to energy consumption from kilns operating at temperatures above 1000 °C for firing ceramics. The ceramics industry accounts for a modest fraction of worldwide carbon emissions in comparison to sectors like steel and cement. While precise statistics differ, estimations indicate that ceramics contribute less than 1% to total global emissions [6,7].

In such circumstances, pertinent challenges have emerged, particularly in industries such as cement, ceramics, and iron and steel, where production involves high-temperature operations, including minimizing energy requirements, assessing waste materials in production processes, and designing systems for waste heat recovery [8,9]. Materials including fly ash [10,11], blast furnace slag [12,13], different natural and calcined pozzolanic additives [14,15,16], and silica fume [17,18,19] are commonly utilized in both academic and industrial sectors [20].

The ceramic industry produces substantial quantities of waste during processing and transportation. This industry faces significant pressure to identify effective recycling techniques for its waste and by-products in order to reduce the quantity of landfills and mitigate the detrimental effects of environmentally harmful waste. Furthermore, considering the finite supplies of conventional aggregates, energy conservation, and environmental protection, the building industry is pursuing alternative sources of consolidation [21,22].

Consequently, CWP is widely utilized as coarse and fine aggregate in both mortars and concrete mixtures. Klimek et al. [23] reported that wall tile waste was utilized as a 25% substitute for sand, and mortars using CWP exhibited comparable density and porosity to those with quartz aggregate, albeit the water absorption rate was reduced. In strength tests performed following freeze–thaw cycles, the tensile and compressive strengths of mortars incorporating CWP were markedly superior to those utilizing natural sand, demonstrating that CWP exhibited greater resistance to temperature fluctuations.

Guendouz et al. [24] noticed a 30% enhancement in compressive strength and a 57% improvement in the flexural strength of fluidized sand concrete by substituting 25% of the sand with wall tile waste. The assessment and repurposing of CWP (wall tiles) as fine aggregate in place of sand for the manufacturing of fluidized sand concrete (FSC) were investigated, with sand being substituted by CWP at varying proportions (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25% of the sand volume). The study observed that the partial substitution of sand enhanced the workability of FSC, decreased its bulk density, and improved its mechanical strength relative to the incorporation of 25% wall tile waste.

The study by Mawashee et al. [25] found that substituting CWP for sand enhanced resistance to sulfate attack and improved the waterproofing qualities of concrete. This study aims to enhance certain mechanical properties of concrete through the incorporation of an integrated waterproofing additive (IWP) and fine-grained CWP in concrete manufacture. Utilizing CWP in place of sand resulted in an increase in compressive strength from 41.7 MPa to 47.8 MPa, an enhancement in elasticity modulus from 25.22 GPa to 29.61 GPa, a reduction in water absorption rate to below 1%, and an improvement in resistance to sulfate attack. These studies demonstrate that utilizing CWP as a filler material offers benefits in both environmental and mechanical dimensions.

Besides employing CWP as a filler in concrete applications, much research also explores its use as a partial alternative for cement. Alotaibi et al. [26] assessed the compressive strength and water absorption characteristics by incorporating 5%, 15%, 25%, 35%, and 45% CWP into concrete mixtures, revealing that a 5% addition of CWP enhanced the compressive strength of concrete by approximately 12.5%. Nevertheless, the strength diminished and the water absorption rate escalated with additions exceeding this threshold. SEM tests indicated that elevated ceramic content resulted in poor particle bonding and aggregation development.

The research conducted by Dehghani et al. [27] assessed the mechanical and environmental impacts of substituting CWP for cement in concrete paving blocks. The study evaluated the compressive strength, tensile strength, water absorption, freeze–thaw resistance, and abrasion resistance of paving blocks produced by replacing 10%, 20%, and 30% of the cement with CWP. A 20% substitution of CWP enhanced compressive strength by 30% and tensile strength by 19%. The freeze–thaw process reduced the mass loss by 40%. The water absorption rate decreased but failed to comply with the EN 1338 standard limitations. No notable alteration was detected in the abrasion resistance. The life cycle evaluation indicated substantial decreases in environmental consequences.

Utilizing CWP as a filler or partial alternative for cement has certain challenges and constraints. Research indicates that CWP causes bleeding in concrete by gradually releasing retained water, diminishes workability owing to its abrasive surface, and lowers fresh density due to its reduced specific gravity.

Literature indicates that the incorporation of CWP in concrete and cement-based products elevates the water demand of the mixture, and this increase adversely affects performance. Alotaibi et al. [26,28] noticed that the water intake increased with the addition of 5% to 45% CWP in the concrete mixture. The utilization of elevated concentrations of CWP augmented the porosity of the concrete and enhanced its water absorption capacity. This resulted in a reduction of the concrete’s strength.

Korat et al. [29] examined the utilization of CWP as a substitute for cement and fine aggregate in ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). The investigation revealed a reduction in the workability of the mixture attributable to the elevated surface area of CWP. This correlated with increased water absorption of CWP.

In their research, Ghonaim and Morsy [30] utilized fine CWP sourced from cyclones associated with spray dryers in ceramic tile manufacturing as a partial cement replacement material, owing to its pozzolanic characteristics in concrete production. They noted that an increase in the CWP ratio resulted in diminished workability of the concrete, with a 30% substitution leading to a 32% reduction in workability.

Recent research have investigated the integration of ceramic waste and nanosilica in cementitious materials; however, the simultaneous application of hydrophobized ceramic waste powder (CWP) and nanosilica has been largely overlooked. Alvansazyazdi et al. (2023) [31] examined the impact of hydrophobic nanosilica on the corrosion resistance and mechanical properties of concrete mixtures, whereas Korat et al. (2025) thoroughly evaluated the use of ceramic waste powder as a cement substitute in ultra-high-performance concrete, highlighting mechanical and microstructural advantages with up to 20% replacement [29,32]. Alotaibi et al. (2024) investigated the incorporation of waste ceramic powder as a filler in traditional concrete, demonstrating enhanced strength at low concentrations while noting challenges related to particle aggregation and porosity at elevated levels [26]. This study combines the inclusion of nanosilica with both natural and hydrophobized CWP to examine their synergistic effects on cement hydration, microstructure, and durability. This innovative dual strategy integrates two previously distinct study domains—nanosilica-induced nanoreactivity and hydrophobization for water repellence—providing fresh perspectives on enhancing the interfacial performance and corrosion resistance of cementitious composites.

The nanosilica dosage range (0.5–2 wt% of cement) was determined from prior studies that indicated optimal enhancements in mechanical strength and microstructure within this range, while preventing severe agglomeration and loss of workability. Fallah-Valukolaee et al. (2022) indicated that a 2% substitution of cement with nanosilica resulted in optimal strength and densification in high-performance concrete [33]. Du et al. (2014) and Lu & Poon (2018) similarly established that nanosilica concentrations over 2% result in particle aggregation, adversely impacting dispersion and hydration efficacy [34,35]. To confirm this range for the current system, first mixing studies were performed using nanosilica dosages of 0.5%, 1%, and 2%. The results validated constant workability and a consistent increase in compressive strength up to 2%, after which no more enhancement was noted.

The hydrophobization of ceramic waste powder (CWP) was executed utilizing a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based organosiloxane treatment, selected for its shown effectiveness in providing lasting hydrophobicity and chemical compatibility with silicate materials. PDMS-based siloxanes form Si–O–Si connections on the CWP surface, thereby diminishing surface energy while preserving its pozzolanic activity. Mora et al. (2019) and Wang et al. (2020) effectively employed analogous organosiloxane treatments to enhance the water resistance and corrosion durability of concrete [36,37]. In initial laboratory experiments, PDMS-treated CWP demonstrated a contact angle of around 120°, validating the successful hydrophobization and efficient dispersion within the cement matrix.

The outcome gathered from all research studies is that, while the incorporation of CWP in limited quantities may enhance both environmental and mechanical performance, positioning it as a sustainable substitute for cement and a viable filler requires extensive long-term durability research. Additionally, the application of superplasticizers is advised to improve workability and sustain a consistent water/cement ratio. This study investigated an alternative method involving the hydrophobization of CWP through chemical agents. It examined the impact of incorporating both unmodified and modified CWP, with nanosilica additions of 0.5%, 1%, 1.5%, and 2%, as a partial replacement for sand in concrete structures, focusing on fresh mortar and mechanical performance properties. The hydration reaction was monitored using X-ray Diffraction (XRD) and Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) techniques, establishing a correlation between microstructure and performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The materials utilized in this study and the experimental methodologies implemented to assess their performance are detailed below. The ceramic waste powder utilized in the research was sourced from the Çanakkale Seramik facility in Çan, Turkey. The investigation utilized Akçansa CEM I 42.5 N cement. Standard sand was procured from Limak, while the polycarboxylate ether-based plasticizer was obtained from Imerys. Silicon dioxide nano powder of 99.5% purity, with a particle size range of 10–20 nm, was obtained from Sigma Aldrich. An organo-siloxane-based hydrophobization agent was provided by Evonik.

2.2. Methods

Characterization studies included XRD and FTIR instruments for the analysis of raw materials and the observation of the hydration reaction. Samples were analyzed utilizing a Philips PANalytical X’Pert-Pro X-ray diffractometer employing copper (Cu) Kα radiation (UK). XRD investigations were conducted throughout a scanning range of 2λ = 0.6–3° at 40 mA and 30 kV working conditions. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analyses of the materials were performed utilizing a Perkin Elmer Spectrum 100 (Shelton, CT, USA) instrument in transmission mode.

The testing procedures for fresh mortar and performance evaluations were conducted in compliance with the relevant standards, along with the corresponding testing equipment detailed below. A Fritsch (Pittsboro, NC, USA) brand automatic agate mortar was used in the grinding processes in the study. A Collomix (Gaimersheim, Germany) brand VIBA 300 model shaker was used to ensure mixture homogeneity in the hydrophobization process. The Heraeus (Hanau, Germany) T6120 oven was utilized for the heat treatment required in the hydrophobization procedure. A Utest mortar mixer was used in the mixing process of concrete mortar. The Matest (Arcore, Italy) E044N model Automatic Vicat Device was utilized to determine setting times. The Baz Makina (Istanbul, Turkey) BZ-410/M type Automatic Flow Table was utilized for flow testing. A concrete mold conforming to EN 12390-1 was utilized for sample preparation [38]. The Dinç Makina Shaking Table, compliant with the EN 196-1 standard, was utilized for inserting the samples into the molds [39]. The Utest brand Compression and Flexural Strength Testing Machine was utilized for strength assessments.

All environmental parameters during the investigation adhered to the EN 1015-11 standard for mortar testing in masonry, specifically maintaining a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 50% ± 5% European Committee for Standardization (1999) [40]. Sample conditioning was conducted in compliance with the EN 1504-3 standard [41]. Initial seven days: Conditioning under ambient settings of 23 ± 2 °C and 50% ± 5% relative humidity. Next 21 days: Curing in water at 20 ± 2 °C. The flexural and compression tests of the prisms were conducted in line with the EN 12190 standard [42]. The capillary water absorption test was conducted in accordance with the EN 1015-18 standard [43].

3. Experimental

The experimental plan for the study was primarily formulated for the utilization of CWP in its natural state and after hydrophobization. The supplied CWP was initially processed and sieved to achieve a particle size of less than 63 μm. The unmodified portion was retained as is, while the hydrophobization agent was diluted with water to maintain a 15% concentration for the modification procedure. The hydrophobization procedure involved combining ceramic waste powder (CWP) with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) at a 1:6.6 weight ratio. The mixture was formulated under standard laboratory conditions at a temperature of 23 ± 1 °C and a pH of 7.2, then mechanically stirred for 10 min to achieve homogeneous mixture. The diluted chemical was incorporated into CWP and homogenized using a shaker. The resulting cake was dehydrated at 105 °C overnight. After the drying procedure, the film layer that formed on the surface was mechanically removed, and the sample was re-ground to produce hydrophobized CWP. In the experimental design, the quantities of cement, sand, ceramic waste powder, and plasticizer were maintained constant, while nanosilica was included in the mixture at concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, 1.5%, and 2%. The samples were designated as follows: the experimental set utilizing unmodified CWP was labeled N (natural), while the modified experimental set was labeled H (hydrophobized). The samples were further identified by appending the nanosilica ratio to their names.

Table 1 presents the proportions of the components used in the preparation of the samples. The reported water content corresponds to the amount necessary to ensure the desired consistency, which was assessed using the flow table method in accordance with EN 1015-3.

Table 1.

Composition of the mixtures and corresponding water content for flow consistency (wt).

All powder-based raw materials were premixed using a shaker for 3 min. Subsequently, water was added to the mixture in an amount sufficient to achieve a consistent flow value. The mortar was then prepared using a mortar mixer, following the mixing procedure specified in the relevant standard. Fresh densities were measured for all mortar mixes in accordance with EN 1015-6, and setting time tests were performed to assess their curing characteristics, following the procedure defined in EN 196-3 [32,44]. The mortar was placed in two layers into 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm molds and compacted using a flow table by applying 60 drops for each layer, as specified in EN 196-1 [39]. After casting, the specimens were kept in their molds for 24 h while sealed in plastic bags to prevent moisture loss. Subsequently, they were demolded and stored in the same sealed condition for an additional 7 days. After this period, the samples were immersed in water and cured until 28 days of age in accordance with the procedure defined in EN 12190 [42]. All specimens were subjected to flexural and compressive strength testing at the curing ages of 2, 7, and 28 days to evaluate the development of mechanical properties over time. During the strength examination, a piece of each sample was taken out for XRD and FTIR investigations to monitor the reaction. Furthermore, capillary water absorption was evaluated for each specimen, following the sample preparation and testing methodology specified in EN 1015-18 [43].

4. Results

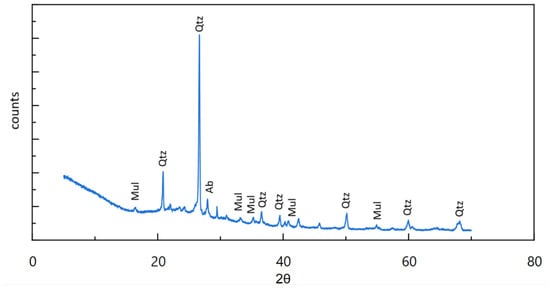

The XRD pattern of the untreated CWP displays predominant crystalline phases characteristic of high-temperature burned ceramics. In Figure 1, the strong peak at 26.6° (2θ) is characteristic of quartz (SiO2), although supplementary reflections at 20.8°, 22°, 28–30°, and 40–45° are linked to feldspathic phases (albite/microcline). Mullite peaks are distinctly observed at around 16.4°, 26°, and 40.8°, thereby affirming the existence of this aluminosilicate phase generated during the ceramic fire process. Minor high-angle peaks ranging from 50° to 65° correspond to secondary reflections of quartz and feldspar. Alongside the crystalline constituents, a low-intensity broad hump between 20 and 25° signifies the existence of amorphous silica, derived from glassy phases within the ceramic matrix. The comprehensive spectrum indicates that raw CWP is primarily crystalline with minimal amorphous content, implying low pozzolanic reactivity and that the material functions chiefly as an inert microfiller in cementitious systems.

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of the untreated CWP (Mul: mullite, Ab: albite, Qtz: quartz).

Table 2 shows the analysis of the cement used in the study using XRD Rietveld. The Rietveld refinement results indicate that the CEM I cement utilized in this study mostly consists of hatrurite (C3S, 66%) and larnite (C2S, 11%), signifying a clinker abundant in silicate phases that influence both early and long-term strength development. The occurrence of brownmillerite (C4AF, 10%) and calcium sodium aluminate–titanate (≈2.4%) indicates the standard ferrite and minor aluminate influences on hydration and setting characteristics. Sulfate-bearing phases, including gypsum (2.3%), anhydrite (0.6%), and bassanite (0.9%), govern the initial hydration of C3A and influence setting regulation. Trivial amounts of periclase (1.4%), arcanite (0.3%), and calcite (4.9%) align with typical CEM I compositions and contribute minimally to expansion regulation and carbonation-related phenomena. The mineralogical profile corresponds with standard high-quality Portland cement and corroborates the anticipated hydration mechanisms identified in the study.

Table 2.

Mineralogical composition of the cements.

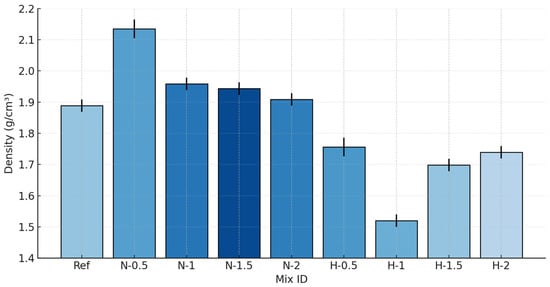

The water content was adjusted for each mixture to maintain a constant flow diameter within the range of 28–30 cm, ensuring uniform workability across all mortar compositions. Fresh mortar densities of the samples are given in Figure 2. The density values of the fresh mortar mixtures exhibited considerable variation based on the type and dosage of nanosilica used. The N-series mixtures demonstrated higher densities (from 1.909 to 2.135 g/cm3) relative to the reference sample (1.889 g/cm3), signifying a denser and more compact matrix, presumably attributable to the presence of heavier particles that reduced entrapped air content [45]. Conversely, the H-series combinations exhibited significantly lower densities (between 1.520 and 1.756 g/cm3), indicating a lighter and maybe more porous structure attributed to the nanosilica concentration and the water-repellent characteristics of hydrophobized CWP [46]. The observed differences at constant flow values (28–30 cm) highlight the influence of compositional variations on the fresh-state properties of the mortars. Such density trends are expected to influence the mechanical strength and durability performance of the hardened materials, which are further discussed in the following sections.

Figure 2.

Fresh mortar densities of the samples.

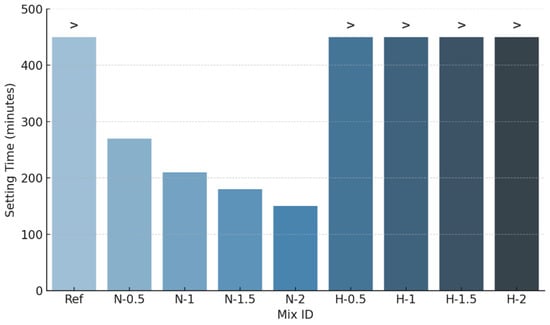

Setting times of the samples are given in Figure 3. Although both N series and H series mixtures incorporate micro silica, a notable reduction in setting time was recorded mainly in the N series (from 270 min to 150 min). Conversely, the setting time exceeded the measurement threshold of 450 min in all H series mixes. This data indicates that the hydrophobic filler substantially delayed the setting process by limiting water–cement interaction and potentially hindering the dispersion and reactivity of nanosilica. As a result, the hydrophobic component’s delaying effect was more significant than the accelerating influence of nano-silica in the H-series mixtures.

Figure 3.

Setting time test results of the samples. (> higher than 450 min).

It was noted that the addition of water to samples containing hydrophobized CWP during mortar preparation resulted in mixing difficulties and foaming, attributable to the surface energy generated by the hydrophobic ingredient. Upon curing the materials, it was ascertained that the lower section comprised concrete, while an upper layer of foam, in variable proportions, was present on the components, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Layering appearance in H-series concrete samples showing two visibly distinct phases.

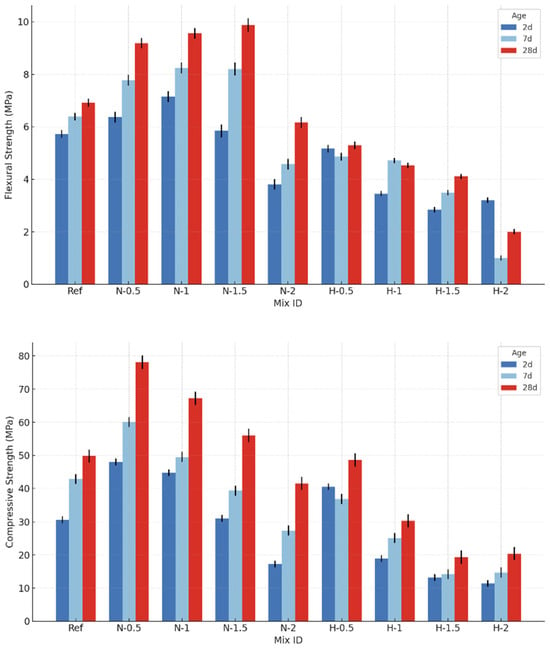

The flexural and compression strength tests of the samples on the 2nd, 7th, and 28th days were conducted in accordance with the EN 12190 standard, and the results are presented in Figure 5. The flexural strength data exhibited a clear developing trend, with an increase in curing age across all combinations. As anticipated, extended curing periods resulted in increased strength due to the advancement of cement hydration and the ensuing densification of the matrix. Among all mixes, the N-series demonstrated the most significant improvement in flexural strength. The N-1 and N-1.5 combinations achieved peak values of roughly 9.5 and 9.8 MPa at 28 days, significantly exceeding the reference mixture. This behavior underscores the beneficial impact of nanosilica due to its nucleating effect and its capacity to enhance the microstructure. Conversely, the H-series mixtures, which contained nanosilica together with hydrophobic CWP, exhibited significantly reduced flexural strength values. In H-1.5 and H-2, the strength was markedly lower than both the N-series and the reference combination. The results indicate that the hydrophobic filler may have obstructed the contact between cement particles and water, thereby delaying hydration and restricting strength development. Furthermore, the hydrophobic environment may have adversely impacted the dispersion and reactivity of nanosilica particles [31,47].

Figure 5.

Flexural and compressive strength of samples (2, 7, and 28 days).

The reference combination exhibited a progressive enhancement in strength over time, reaching around 6.9 MPa at 28 days. This number functioned as a benchmark for assessing the impacts of the various additions. The N-series exceeded the reference performance across all age groups, whereas the H-series typically underperformed.

The compressive strength data clearly illustrates the influence of nanosilica dose and the use of hydrophobic filler on the mechanical properties of cement-based composites. The reference mixture demonstrated a consistent and predicted increase in strength over time, functioning as a reliable baseline. Conversely, the N-series combinations, containing different quantities of nanosilica, demonstrated improved strength progression, especially after 28 days. The N-0.5 mixture attained the highest compressive strength (~78 MPa), demonstrating that a low-to-moderate dosage of nanosilica effectively enhances hydration and compacts the microstructure. Nonetheless, an additional increase in nanosilica concentration (as observed in N-2) resulted in a decline in strength, likely due to particle agglomeration and an imbalance in water demand.

The integration of nanosilica markedly improves the hydration process of cement-based systems via both physical and chemical mechanisms. Nanosilica particles, owing to their elevated specific surface area, facilitate the nucleation of hydration products, hence expediting the development of calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel, especially in the early stages [48]. Moreover, their elevated pozzolanic reactivity facilitates the utilization of calcium hydroxide produced during hydration, resulting in the generation of supplementary C–S–H, which enhances the volume and continuity of binding phases [49]. Their synergistic effects result in a denser microstructure and decreased porosity, hence enhancing compressive strengths at both early and late ages [50]. Thus, nanosilica emerges as a potent additive for improving the mechanical properties and microstructural integrity of concrete systems.

Conversely, the H-series mixtures, comprising both nanosilica and hydrophobic filler, consistently exhibited reduced compressive strength values at all ages. This indicates that the hydrophobic component considerably inhibited the hydration process by limiting water-cement interaction and maybe hindering the dispersion and reactivity of nanosilica [31,46].

As a result, mixes like H-1.5 and H-2 demonstrated both postponed strength growth and diminished final performance. These findings highlight the necessity of carefully calibrating chemical admixtures in cementitious systems to prevent adverse interactions and to maximize the advantages of nanoscale additives.

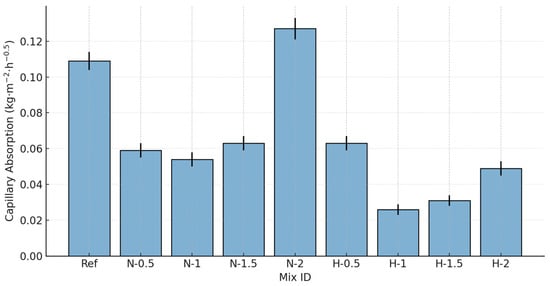

Results of capillary water absorption (Figure 6) demonstrate a substantial impact of both nanosilica dose and the inclusion of hydrophobic filler on the permeability of the mortars. The reference combination exhibited the highest absorption rate (0.109 kg·m−2·h−0.5), while all modified systems showed lower values. The N-series combinations, especially N-0.5 and N-1, exhibited improved matrix densification, hence decreasing water penetration. Nevertheless, an excessive concentration of nanosilica (N-2) resulted in increased absorption, possibly attributable to particle agglomeration or microcracking. Conversely, H-series mortars demonstrated the lowest absorption values, with H-1 and H-1.5 registering below 0.035 kg·m−2·h−0.5. This validates the efficacy of hydrophobic filler inhibiting capillary transport, underscoring its potential for applications where durability is important.

Figure 6.

Capillary water absorption values of samples.

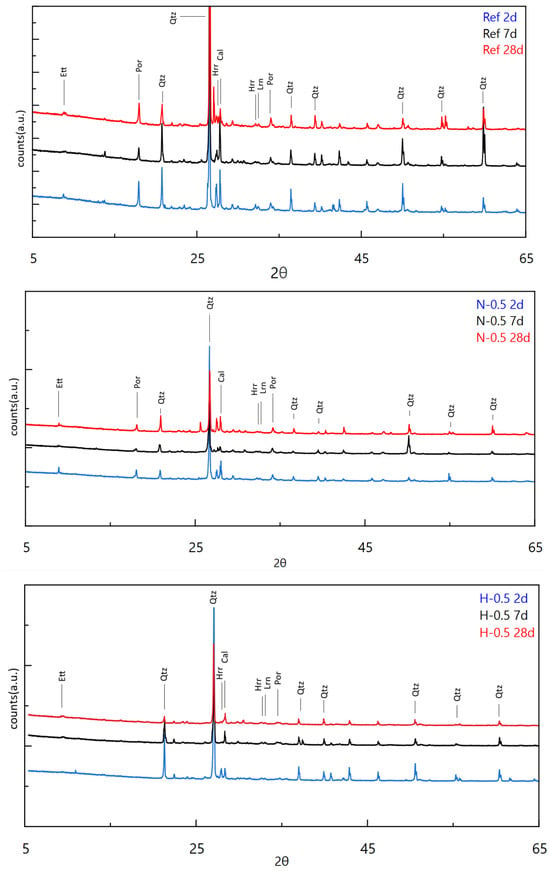

Figure 7 presents the XRD analysis diffractograms of the reference, N-0.5, and H-0.5 samples obtained after 2, 7 and 28 days of curing. The advancement of the hydration process in the samples can be monitored by the reduction of the primary cement phase (alite) at 32.5° in the XRD diffractograms and the increase of the portlandite peak at 18°. The reduction in cement quantities is evident as a result of the prolonged reaction time [51]. The XRD patterns exhibited distinct peaks associated with portlandite (18° and 34°), quartz (26.6°), and calcite (29.3° and 43°), in addition to a large amorphous hump between 20° and 22°, attributable to C–S–H gel. A slow decline in portlandite peaks and an augmentation of the amorphous C–S–H area from 2 to 28 days signified ongoing hydration and pozzolanic activity, especially in the N-0.5 mix. In the H-0.5 series, the consumption of portlandite transpired at a slower rate due to the hydrophobic surface; yet, a comparable trend was noted at later ages, affirming delayed yet ongoing hydration.

Figure 7.

XRD diffractogram of Ref, N-0.5 and H-0.5 samples for 2, 7 and 28 days (a.u.: arbitrary units) (Ett.: ettringite, Por.: portlandite, Hrr.: hatrurite, Qtz.: quartz, Lrn.: larnite, Cal.: calcite).

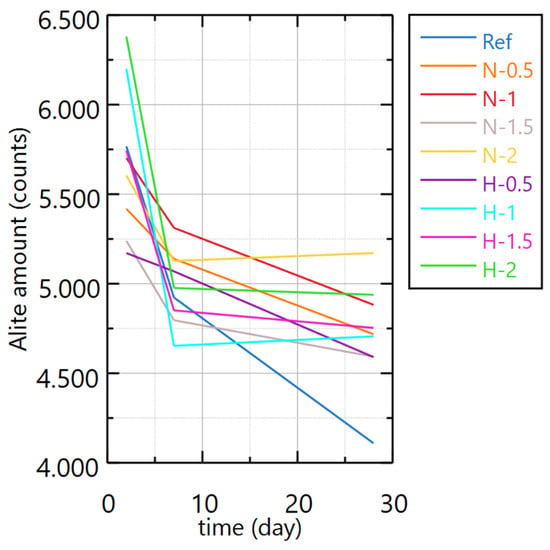

To observe the reaction progress rate for all samples, graphs were constructed based on the count values of the alite phase, the main component of cement, corresponding to their curing durations, as illustrated in Figure 8 [52]. An evaluation of cement consumption on the 2nd and 28th days of the reaction reveals that the reference sample exhibits the highest level of consumption. While the N series generally demonstrates better cement utilization than the H series, the second sample in both series shows the weakest performance. This trend aligns with the observed strength results.

Figure 8.

Amount of unreacted cement phase in samples.

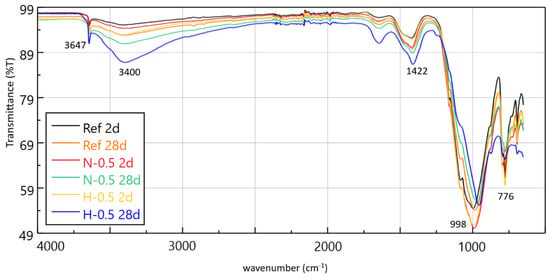

FTIR analysis is especially critical for monitoring the C-S-H gel, which cannot be detected in XRD analysis due to its amorphous structure. The FTIR analysis results for varying curing durations (2 and 28 days) were assessed to analyze the production and progression of hydration products in the samples (Figure 9). Spectra were analyzed primarily based on bands associated with C–S–H gel, Ca(OH)2, carbonate, and water.

Figure 9.

FTIR spectrum of Ref, N-0.5 and H-0.5 samples for 2 and 28 days.

The weak band at around 3640 cm−1 corresponds to the O–H stretching vibration of Ca(OH)2. The band is stronger on the second day, particularly in the reference and N-0.5 samples, and it diminishes in the 28-day samples. This scenario illustrates that the portlandite generated by hydration is gradually utilized by pozzolanic processes over time. This band exhibits considerable weakness in the H-0.5 28-day sample, potentially attributable to the influence of the addition on the hydration process [53].

The extensive bands at 3400–3450 cm−1 and 1650 cm−1 are indicative of the O–H stretching and bending vibrations of physical water, respectively. It is noted that these bands diminish in 28-day samples; this phenomenon suggests that free water is utilized during the curing period and gelation intensifies as hydration advances. Conversely, the permeability (%T) in these places is diminished in the H-0.5 28 d sample, indicating that the sample retains more water or possesses greater structural porosity [54].

The peaks detected in the ~1420 cm−1 range signify the existence of carbonate (CO32−). These peaks grew increasingly apparent, particularly in the 28-day data. The rise, linked to the generation of CaCO3 by the reaction of Ca(OH)2 with ambient CO2, signifies the progression of the carbonation process over time [53].

The distinctive band of the C–S–H gel, the principal hydration product, is detected at around 970 cm−1. The pronounced and intensified development of this band in the 28-day samples corroborates that the creation of C–S–H has augmented, and the hydration process has advanced. This rise is particularly significant in the reference samples and those doped with N-0.5. The results from the 28th day of the H-0.5 sample indicate a diminished gelation relative to the other samples [55].

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the utilization of CWP as alternatives for aggregate in cement-based systems through a comprehensive approach. The research examined the mechanical capabilities, microstructural characteristics, and durability performance of mortar and concrete samples with varying quantities of CWP additives.

Mechanical testing revealed that low-ratio ceramic waste additions, particularly at 0.5% and 1% concentrations, yielded compressive and tensile strengths comparable to, or in certain instances superior to, the reference combinations. Nevertheless, an increase in the additive ratio to 1.5% and 2% resulted in a reduction of strength values, attributed to the inert nature of the additives and the increased void volume.

XRD analyses demonstrated the temporal progression of hydration products. Regarding the production of portlandite (Ca(OH)2) and C–S–H gel, it was noted that the reference and low-additive mixes exhibited larger amounts of crystalline phases. The reduction of portlandite peaks in 28-day samples and the augmentation of amorphous regions associated with C–S–H validated the advancement of hydration.

FTIR investigations corroborate these findings, indicating that the characteristic bands of C–S–H gel near 970 cm−1 intensify over time, whereas the bands associated with water (3400 and 1650 cm−1) and portlandite (3640 cm−1) diminish. The elevation of carbonate bands noted around 1420 cm−1 signifies the carbonation process resulting from environmental contact. It was shown that, particularly in groups utilizing hydrophobic additive ceramic waste, hydration commenced later, and water was kept inside the system for an extended duration.

Tests on capillary water absorption and hydrophobic performance indicated that certain additives diminished the water permeability of concrete; nevertheless, in some samples, water absorption increased due to heightened porosity. Hydrophobized chemicals, while initially retarding hydration, ultimately enhanced carbonation resistance over time. The synergistic application of nanosilica and ceramic waste powder (CWP) significantly enhanced the mechanical and durability characteristics of the mixtures. In comparison to the reference, compressive and flexural strengths improved by as much as 57% and 43%, respectively, with the incorporation of 0.5%–1.5% nanosilica, whilst hydrophobized CWP diminished capillary water absorption by up to 76%. The findings validate that nanosilica promotes matrix densification, while PDMS-based hydrophobization significantly boosts water resistance, positioning the proposed system as a viable approach for sustainable high-performance cementitious composites.

From an environmental standpoint, replacing 30% of natural aggregate with recycled ceramic waste powder diminishes virgin material usage by around 30% and is projected to reduce CO2 emissions linked to aggregate manufacturing and transportation by about 8%–10%.

Using CWP in cement-based systems in small, controlled amounts is good for both the environment and the technology. The type of additive (e.g., granular or powder, hydrophobic or otherwise), along with its structure and dosage, significantly influences this performance. Therefore, in future studies, it is recommended that surface modification, activation processes and long-term durability performances be evaluated in detail.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Kalekim Construction Chemicals Co. for providing access to laboratory facilities and technical infrastructure used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Nevin Karamahmut Mermer is an employee of Kalekim Construction Chemicals Co. The paper reflects the views of the scientists and not the company.

References

- Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Agwa, I.S.; Rizk, M.S. Effect of industrial wastes on the properties of sustainable ultra-high-performance concrete: Ganite, ceramic, and glass. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohit, M.; Haftbaradaran, H.; Riahi, H.T. Investigating the ternary cement containing Portland cement, ceramic waste powder, and limestone. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, K.H.; Alengaram, U.J.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Yap, S.P. Feasibility study of high volume slag as cement replacement for sustainable structural lightweight oil palm shell concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteiro, P.; Araújo, A.; Oliveira, B.; Dias, A.C.; Arroja, L. The carbon footprint and energy consumption of a commercially produced earthenware ceramic piece. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 32, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, R.M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1675–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukannan, M.; Ganesh, A.S.C. The Environmental Impact Caused by the Ceramic Industries and Assessment Methodologies. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2019, 13, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Jiao, L.; Zheng, W.; Zeng, L. CO2 Emission Calculation and Reduction Options in Ceramic Tile Manufacture—The Foshan Case. Energy Procedia 2012, 16, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiang, N.; Pan, H.; Yang, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, H.; Xu, C. Performance comparison of cement production before and after implementing heat recovery power generation based on emergy analysis and economic evaluation: A case from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenco-Porto, C.A.; Fierro, J.J.; Londoño, C.N.; Lopera, L.; Atehortua, A.E.; Giraldo, M.; Jouhara, H. Potential savings in the cement industry using waste heat recovery technologies. Energy 2023, 279, 127810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, Y.; Nas, S. The effect of using fly ash on the strength and hydration characteristics of blended cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 73, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneyisi, E.; Gesoğlu, M.; Booya, E.; Mermerdaş, K. Strength and permeability properties of self-compacting concrete with cold bonded fly ash lightweight aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 74, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilim, C.; Atis, C.D. Alkali activation of mortars containing different replacement levels of ground granulated blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binici, H.; Temiz, H.; Köse, M.M. The effect of fineness on the properties of the blended cements incorporating ground granulated blast furnace slag and ground basaltic pumice. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Bahrami, J.H. Influence of metakaolin as supplementary cementing material on strength and durability of concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R.; Kadri, E.H. Effect of metakaolin and foundry sand on the near surface characteristics of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3257–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannag, M.J. High strength concrete containing natural pozzolan and silica fume. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Ochbelagh, D.; Azimkhani, S.; Gasemzadeh2, M.H. Shielding and strength tests of silica fume concrete. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2012, 45, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, F.A.; Libre, N.A.; Shekarchi, M. Mechanical and durability properties of self consolidating high performance concrete incorporating natural zeolite, silica fume and fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R. Utilization of silica fume in concrete: Review of hardened properties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1; Composition, Specification and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2000.

- Del Rio, D.D.F.; Sovacool, B.K.; Foley, A.M.; Griffiths, S.; Bazilian, M.; Kim, J.; Rooney, D. Decarbonizing the ceramics industry: A systematic and critical review of policy options, developments and sociotechnical systems. Renew. Sust. Energ. 2022, 157, 112081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.; Cruz, P.L.; Moura, B. Integrated environmental and economic life cycle assessment of improvement strategies for a ceramic industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 345, 131173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, B.; Szulej, J.; Ogrodnik, P. The effect of replacing sand with aggregate from sanitary ceramic waste on the durability of stucco mortars. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2020, 22, 1929–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guendouz, M.; Boukhelkhal, D.; Bourdot, A.; Hamadouche, A. The Effect of Ceramic Wastes on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Eco-Friendly Flowable Sand Concrete. In Ceramic Materials; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mawashee, R.S.A.; Shhatha, M.A.A.; Alatiya, Q.A.J. Waste ceramic as partial replacement for sand in integral waterproof concrete: The durability against sulfate attack of certain properties. Open Eng. Sci. J. 2023, 13, 20220455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, J.G.; Alajmi, A.E.; Alsaeed, T.; Khalaf, J.A.; Yousif, B.F. On the incorporation of waste ceramic powder into concrete. Front. Mech. Eng. 2024, 10, 1469727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, O.; Eslami, A.; Mahdavipour, M.A. Ceramic waste powder as a cement replacement in concrete paving blocks: Mechanical properties and environmental assessment. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2024, 25, 2370563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Alattyih, W.; Jebur, Y.M.; Alqurashi, M.; Garcia-Troncoso, N. A review on ceramic waste-based concrete: A step toward sustainable concrete. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2023, 62, 20230346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korat, A.; Amin, M.; Tahwia, A.M. A comprehensive assessment of ceramic wastes in ultra high performance concrete. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghonaim, S.; Morsy, R. Utilization of Ceramic Waste Material as Cement Substitution in Concrete. Buildings 2023, 13, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvansazyazdi, M.; Alvarez-Rea, F.; Pinto-Montoya, J.; Khorami, M.; Bonilla-Valladares, P.M.; Debut, A.; Feizbahr, M. Evaluating the Influence of Hydrophobic Nano-Silica on Cement Mixtures for Corrosion-Resistant Concrete in Green Building and Sustainable Urban Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 196-3; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 3: Determination of Setting Time and Soundness. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Fallah-Valukolaee, S.; Mousavi, R.; Arjomandi, A.; Nematzadeh, M.; Kazemi, M. A comparative study of mechanical properties and life cycle assessment of high-strength concrete containing silica fume and nanosilica as a partial cement replacement. J. Struct. 2022, 46, 838–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Du, S.; Liu, X. Durability performances of concrete with nano-silica. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 73, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.X.; Poon, C.S. Improvement of early-age properties for glass–cement mortar by adding nanosilica. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 89, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, E.; González, G.; Romero, P.; Castellón, E. Control of water absorption in concrete materials by modification with hybrid hydrophobic silica particles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 221, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lei, S.; Ou, J.; Li, W. Effect of PDMS on the waterproofing performance and corrosion resistance of cement mortar. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 507, 145016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12390-1; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 1: Shape, Dimensions and Other Requirements for Specimens. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2000.

- EN 196-1; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 1: Determination of Strength. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 1015-11; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 11: Determination of Flexural and Compressive Strength of Hardened Mortar. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 1504-3; Products and Systems for the Protection and Repair of Concrete Structures—Definitions, Requirements, Quality Control and Evaluation of Conformity—Part 3: Structural and Non-Structural Repair. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 12190; Products and Systems for the Protection and Repair of Concrete Structures—Test Methods—Determination of Compressive Strength of Repair Mortar. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1999.

- EN 1015-18; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 18: Determination of Water Absorption Coefficient due to Capillary action of Hardened Mortar. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- EN 1015-6; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 6: Determination of Bulk Density of Fresh Mortar. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 1998.

- Skarendahl, A. Ultrafine Particles in Concrete. Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Jiang, L.; Shi, X.; Wang, X. Water-soluble fluorosilane supplemented with fumed silica as a novel admixture for concrete: Hydrophobicity, strength, and durability. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 107127. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z. Effect of highly dispersed colloidal olivine nano-silica on early age hydration and rheology of ultra-high performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104564. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hsu, M.; Niu, D. Effects of Nanosilica on Microstructure and Durability of Cement-Based Materials. Powder Technol. 2022, 404, 117447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, M.; Kumar, S.; Sinha, S. Nanosilica’s Influence on Concrete Hydration, Microstructure, and Durability: A Review. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2024, 14, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, V.S.; Sancheti, G.; Yadav, J.S.; Agrawal, U. Smart Sustainable Concrete: Enhancing the Strength and Durability with Nano Silica. Smart Constr. Sustain. Cities 2023, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnceoğlu, F.; Mermer, N.K.; Kırmızı, V.; Tombaş, G. Influence of cement with different calcium sulfate phases on cementitious tile adhesive mortars: Microstructure and performance aspects. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 104, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermer, N.K.; İnceoğlu, F.; Pınar, E.Ü. The effect of the moisture content of sand used in cement-based ceramic tile adhesives on their microstructure and performance. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2024, 130, 103634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoch, A.; Zdaniewicz, M.; Paluszkiewicz, C. The effect of polymethylsiloxanes on hydration of clinker phases. J. Mol. Struct. 1999, 511–512, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojaraju, C.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C.M. Boosting cement hydration with boron nitride nanotubes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 157, 105894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgnies, M.; Chen, J.J.; Bouillon, C. Overview about the use of Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy to study cementitious materials. WIT Trans. Eng. Sci. 2013, 77, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.