Orbital-Scale Climate Control on Facies Architecture and Reservoir Heterogeneity: Evidence from the Eocene Fourth Member of the Shahejie Formation, Bonan Depression, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Database and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Lithofacies Associations

4.1.1. Alluvial Fans (LFA 1)

4.1.2. Braided Rivers (LFA 2)

4.1.3. Floodplain Mudstones (LFA 3)

4.1.4. Fan Deltas (LFA 4)

4.1.5. Saline Lacustrine (LFA 5)

4.2. Vertical and Lateral Facies Distributions

4.2.1. Vertical Distribution

4.2.2. Lateral Distribution

4.2.3. Paleogeographic Evolution

4.3. Sequence Stratigraphic Architecture

4.3.1. Sequence Boundaries

4.3.2. Systems Tracts

- (a)

- Lowstand Systems Tract

- (b)

- Transgressive Systems Tract

- (c)

- Highstand Systems Tract

4.4. Paleoclimate Proxies

- (a)

- Geochemical Proxies

- (b)

- Mineralogical Indicators

- (c)

- Sedimentological Signatures

- (d)

- Cyclostratigraphic Framework

4.5. Provenance Signatures and Sediment Supply Pathways

4.5.1. Provenance Signatures

4.5.2. Sediment Supply Pathways

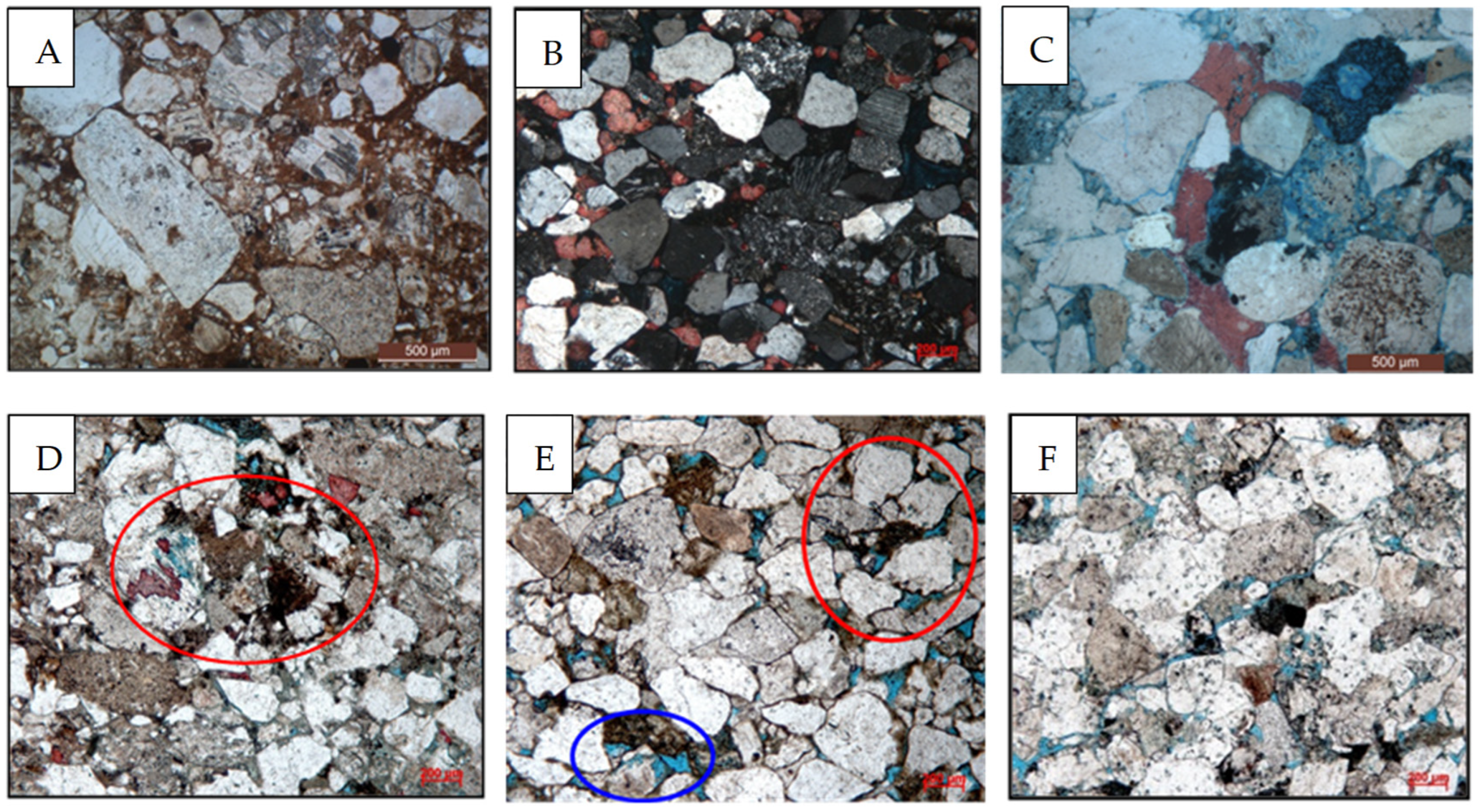

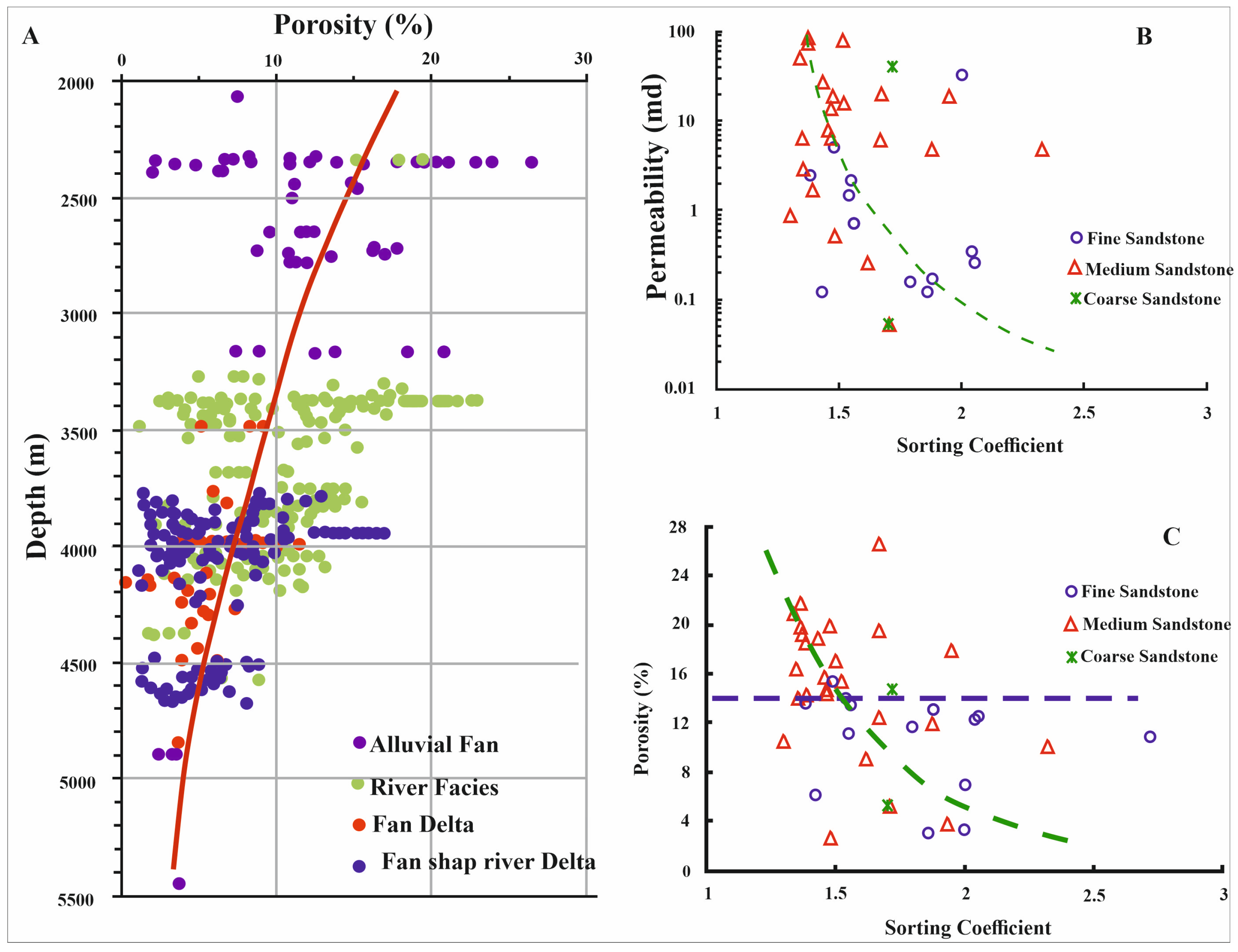

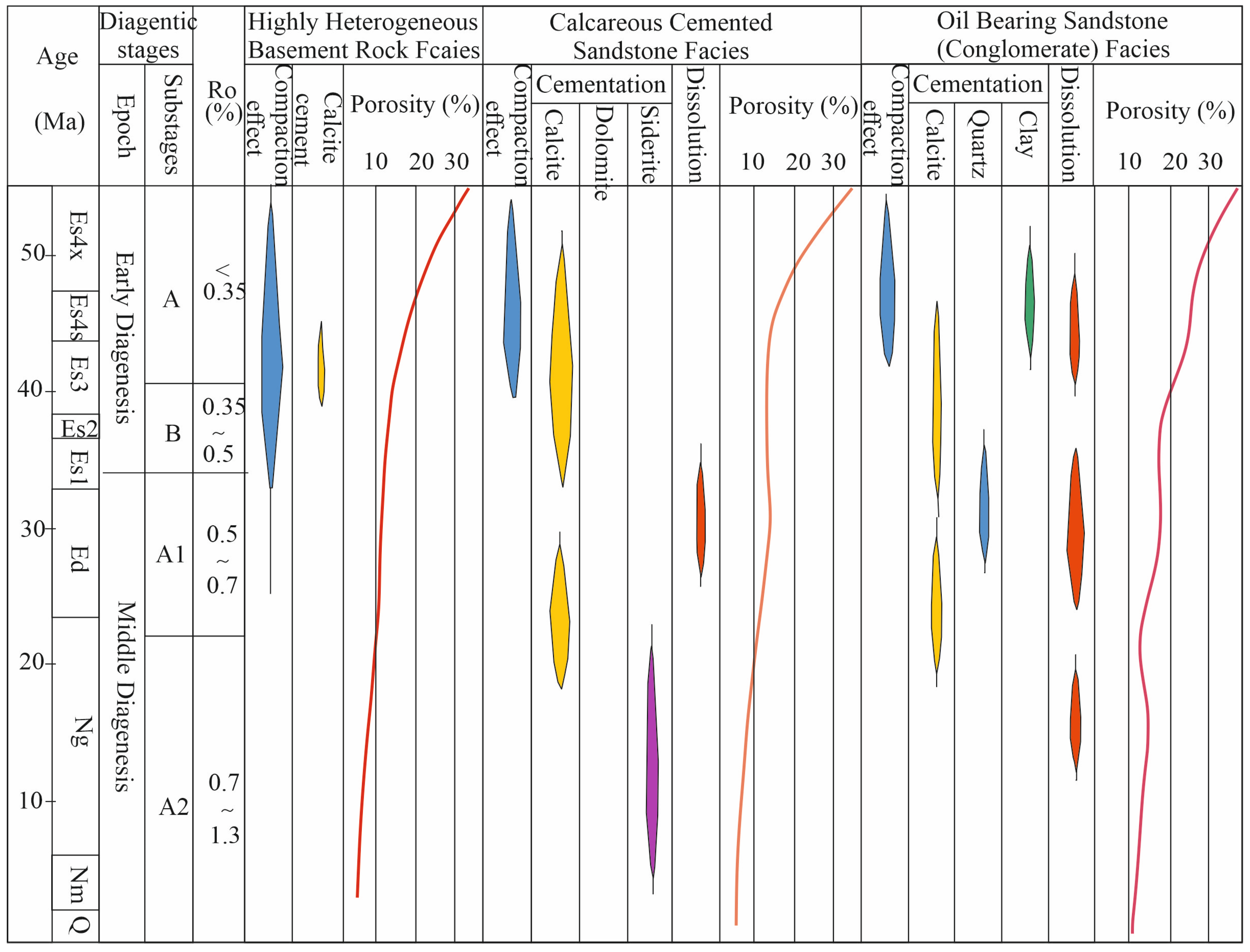

4.6. Diagenetic Modifications and Impact on Reservoir Properties

4.6.1. Diagenetic Processes

4.6.2. Diagenetic Facies Zonation

4.6.3. Reservoir Quality Evolution

5. Discussion

5.1. Sedimentary Evolution of the Eocene Fourth Member (Lower Submember of the Fourth Member of the Shahejie Formation)

5.1.1. Stage I

5.1.2. Stage II

5.1.3. Stage III

5.2. Depositional Model for Eocene Red Beds

5.3. Tectonic and Climatic Controls on Deposition

5.3.1. Tectonic Dominance

5.3.2. Climate Overprint

5.4. Facies Model for Arid Humid Transitional Basins

5.4.1. Climate-Driven Vertical Successions

5.4.2. Tectonically Partitioned Facies Belts

5.4.3. Diagenetic Zonation

5.5. Reservoir Implications

5.5.1. Facies Dominated Reservoir Zonation

5.5.2. Diagenetic Pathways

5.6. Synthesis of Sedimentological Controls

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qi, Z.C.; Li, P.; Wu, J.J.; Gamisch, A.; Yang, T.; Zhao, Y.P.; Xu, W.Q.; Chen, S.C.; Cameron, K.M.; Qiu, Y.X. Climatic niche evolution in Smilacaceae (Liliales) drives patterns of species diversification and richness between the Old and New World. J. Syst. Evol. 2023, 61, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, L. Stepwise hydroclimate changes in Northeast China linked to proto-Paratethys Sea retreats and global cooling during the Eocene. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2024, 648, 112306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froemchen, M. Inheritance Across the Scales–Assessing the Relative Importance of Crustal and Lithospheric Structures During Rift Evolution. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2024. Available online: https://etheses.dur.ac.uk/15825/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Q.; Qin, L. The Segmented Multi-Source Sediment Routing System on the Hangingwall Dipslope of the Xihu Depression, East China Sea Shelf Basin: Insights From Palaeogeomorphology, U–Pb Ages and Heavy Minerals. Basin Res. 2024, 36, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Chen, L.; Lu, C.; Chen, K.; Zheng, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Cao, J. Depositional and Paleoenvironmental Controls on Shale Reservoir Heterogeneity in the Wufeng–Longmaxi Formations: A Case Study from the Changning Area, Sichuan Basin, China. Minerals 2025, 15, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qayim, B.A. The Paleogene Forebulge Carbonate Banks, Zagros Foreland Basin, Northern Iraq: Their Paleogeography, Basin Evolution, and Economic Implications. Iraqi Geol. J. 2024, 57, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, L.; Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Zeng, S.; Ruebsam, W.; Ahmed, M.S.; Shen, H.; Mansour, A. Eocene climate and hydrology of eastern Asia controlled by orbital forcing and Tibetan Plateau uplift. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2024, 646, 118981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Ma, C.; Feng, Z.; Tang, W.; Fang, X. Tibetan plateau uplift changed the Asian climate and regulated its responses to orbital forcing during the late Eocene to early Miocene. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2025, 130, e2024JD042872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Bai, N.; Wu, S.; Liu, B. Organic matter enrichment mechanism in saline lacustrine basins: A review. Geol. J. 2024, 59, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wu, S.; Yue, D.; Cui, W. Paleosalinity reconstruction in offshore lacustrine basins based on elemental geochemistry: A case study of Middle-Upper Eocene Shahejie Formation, Zhanhua Sag, Bohai Bay Basin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2024, 42, 1087–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Yan, X.; Tan, X.; Garzanti, E.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Luo, L. Lacustrine hydrochemical variations and carbon sequestration under hyperthermal climates: Insights from the Lower Eocene Kongdian Formation (Bohai Bay Basin, NE China). Int. J. Earth Sci. 2025, 114, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Li, Z.; Huang, L.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, J. Characteristics and controlling factors of deep-seated reservoir: A case study from the Fukang Sag of Junggar Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, M.; Fatemi Aghda, S.M.; Sarkheil, H.; Teshnehlab, M.; Salehi, E.; Kamrani, K.; Yamini, A. A systematic review to identify carbonate rock exploration paradigms and examine current and future research directions: A case study at one of the southwest oil fields of Iran. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2025, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Fang, X.; Hu, X.; Meng, T.; Yu, L.; Guo, Z.; Liu, G.; Liu, K. Strong Reservoir Wettability Heterogeneities of an Eocene Tight Oil Play from the Bonan Sag, Bohai Bay Basin as Revealed by an Integrated Multiscale Wettability Evaluation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyat, A.M.E.; Obaidalla, N.A. Sequence stratigraphy, sea-level dynamics, and syn-sedimentary tectonic evolution of the Late Cretaceous/Paleocene basin on the western shoulder of the Gulf of Suez, Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 2025, 18, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhou, Q.; Li, S.; Guan, Q.; Wang, G. Mesozoic to Cenozoic tectonic evolution in the central Bohai Bay Basin, East China. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2024, 136, 4965–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Tong, D.; Hu, C.; Xu, Y.; Ren, J. Two Stages of Rifting Control the Crust Thinning and Basin Evolution: Insights from the Southern Qiongdongnan Basin, NW South China Sea. Basin Res. 2025, 37, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-J.; Wang, Y.-R.; Lu, R.; Zhang, S.-S.; Wang, G.-L. Geology, carbon emission reduction potential, and development progress of hot dry rock in China. China Geol. 2025, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Fan, G.; Lu, Y.; Shao, D.; Liu, S.; Wang, W. Tectonic Subsidence and Its Response to Geological Evolution in the Xisha Area, South China Sea. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Cao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Yu, H.; Chen, W.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, W. Impact of Pore Structure on Seepage Capacity in Tight Reservoir Intervals in Shahejie Formation, Bohai Bay Basin. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Fault Families Around Salt Structures: Implications for Fluid Flow, Storage and Production. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2023. Available online: https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/165655/1/2023zhangqphd.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Gao, M.; Yu, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Hu, S.; Zhang, M. Control of slope-pattern on the deposition of fan-delta systems: A case study of the Upper Karamay Formation, Junggar Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 18, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J. Sedimentary cycles of evaporites and their application in sequence division in the upper member of the Xiaganchaigou Formation in Yingxi Area, Southwestern Qaidam Basin, China. Carbonates Evaporites 2020, 35, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, K.; He, S.; Song, G.; Wang, Y.; Hao, X.; Wang, B. Petroleum generation and charge history of the northern Dongying Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China: Insight from integrated fluid inclusion analysis and basin modelling. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2012, 32, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, D.; Li, R.; Mao, Y. Drainage evolution in accretionary thrust systems as responses to tectono-climatic variability: Insights from sandbox modelling. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2025, 50, e70099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Huan, L.; Zhangqiang, S.; Donghui, J. Sequence stratigraphy of the lacustrine rift basin in the Paleogene system of the Bohai Sea area: Architecture mode, deposition filling pattern, and response to tectonic rifting processes. Interpretation 2020, 8, SF57–SF79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cai, L.; Liu, H.; Jin, J. Sedimentary characteristics and depositional model of hyperpycnites in the gentle slope of a lacustrine rift basin: A case study from the third member of the Eocene Shahejie Formation, Bonan Sag, Bohai Bay Basin, Eastern China. Basin Res. 2023, 35, 1590–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wang, J.; He, R.; Wang, S.; Xie, J.; Li, Y. Application of Principal Component Analysis to Diagenetic Facies Division of Lake Gravity Flow Sandstone Reservoirs in Dongying Depression of Bohai Bay Basin, China. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-F.; Dong, D.-Z. Thickening-upward cycles in deep-marine and deep-lacustrine turbidite lobes: Examples from the Clare Basin and the Ordos Basin. J. Palaeogeogr. 2020, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaomin, Z.; Xiaolin, W.; Xin, H.; Xiang, W.; Zijie, G. Frontiers and future prospects of international sedimentological research: Review on the 37th International Meeting of Sedimentology. Oil Gas Geol. 2025, 46, 685–704. Available online: https://www.sciopen.com/article/10.11743/ogg20250301 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Wu, T.; Lei, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jie, Y.; Liu, H. Erosion processes and sediment source tracing on heterogeneous slopes in the red soil region of southern China. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 1969–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tan, C.; Shan, X.; Yu, X.; Shi, X. Modern Fluvial-Deltaic Deposits in Daihai Lake Basin, Northern China. In Field Trip Guidebook on Chinese Sedimentary Geology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ji, Y.; Wu, C.; Duclaux, G.; Wu, H.; Gao, C.; Li, L.; Chang, L. Stratigraphic response to spatiotemporally varying tectonic forcing in rifted continental basin: Insight from a coupled tectonic-stratigraphic numerical model. Basin Res. 2019, 31, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, H.; Wen, H.; Xu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. Facies architecture and sediment infilling processes in intrabasinal slope belts of lacustrine rift basins, Zhanhua Depression, Bohai Bay Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 112, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, X.; Wood, L.J.; Shi, R. Evolution of drainage, sediment-flux and fluvio-deltaic sedimentary systems response in hanging wall depocentres in evolving non-marine rift basins: Paleogene of Raoyang Sag, Bohai Bay Basin, China. Basin Res. 2020, 32, 116–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Lu, Z.; Lin, C.; Wang, X.; Pan, R.; Geng, M.; Xue, Y. An early Eocene subaqueous fan system in the steep slope of lacustrine rift basins, Dongying Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China: Depositional character, evolution and geomorphology. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2019, 171, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-Y.; Shi, B.-H.; Ping, Z.-Y.; Li, Z.-Q.; Sun, B. Characteristics of Lacustrine Carbonate Reservoirs: A Case Study of Es4s Layers of Shahejie Formation in Zhanhua Sag, Jiyang Depression. In Proceedings of the International Field Exploration and Development Conference, Xi’an, China, 12–14 September 2024; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, B. Influence of multiphase carbonate cementations on the Eocene delta sandstones of the Bohai Bay Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 205, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Cao, Y.; Eriksson, K.A.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Y. Burial evolution of evaporites with implications for sublacustrine fan reservoir quality: A case study from the Eocene Es4x interval, Dongying depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 76, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Song, G. Sedimentation in a continental high-frequency oscillatory lake in an arid climatic background: A case study of the Lower Eocene in the Dongying depression, China. J. Earth Sci. 2017, 28, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Meng, T.; Bi, J.; Jiang, C. The character and origin of sequence architecture in the arid climate zone: A case of the Lower Submember of the Fourth Member of Shahejie Formation in the Bonan Sub-Sag. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 804, 022033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Meng, T.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H. The sedimentary evolution of distributive fluvial system in arid and low accommodation space sag: A case study of the lower fourth sub-member of Shahejie Formation from Bonan Sag in Zhanhua Depression, Bohai Bay Basin. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 2958, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-C.; Zou, C.-N.; Feng, Y.-L.; Jiang, S.; Wu, W.-A.; Zhu, R.-x.; Yuan, M. Distribution and controls of petroliferous plays in subtle traps within a Paleogene lacustrine sequence stratigraphic framework, Dongying Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, Eastern China. Pet. Sci. 2020, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Yue, Y.; Meng, T.; Bi, J.; Jiang, C. Paleoclimate quantitative reconstruction and characteristics of continental red beds: A case study of the lower fourth sub-member of Shahejie Formation in the Bonan Sag. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2023, 13, 1993–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Song, G. Sedimentary environmental controls on petrology and organic matter accumulation in the upper fourth member of the Shahejie Formation (Paleogene, Dongying depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China). Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 186, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Lin, C.; Li, G.; Dong, C.; Jiang, L.; Du, X.; Ren, M.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Yuan, Y. Lithofacies Characteristics and Sweet Spot Distribution of Lacustrine Shale Oil: A Case Study from the Dongying Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China. Lithosphere 2022, 2022, 3135681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Peng, J.; Xu, T.; Han, H.; Yang, Y. Analysis of Organic Matter Enrichment and Influences in Fine-grained Sedimentary Strata in Saline Lacustrine Basins of Continental Fault Depressions: Case study of the upper sub-section of the upper 4th member of the Shahejie Formation in the Dongying Sag. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2024, 42, 701–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Cao, Y.; Lin, C.; Wang, J. Diagenetic evolution and its implication for reservoir quality: A case study from the Eocene Es4 interval, Dongying Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China. Geosci. J. 2018, 22, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xu, S.; Cai, C.e.; Shang, W.; Mao, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Yin, N.; Luo, K. Fault control on sedimentation in the southern gentle slope of the Dongying Sag, Bohai Bay Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 166, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, W.J.; Goñi, M.F.S. Orbital-and sub-orbital-scale climate impacts on vegetation of the western Mediterranean basin over the last 48,000 yr. Quat. Res. 2008, 70, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Jin, Z.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Hao, Y. Terrestrial sedimentary responses to astronomically forced climate changes during the Early Paleogene in the Bohai Bay Basin, eastern China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 502, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structural Zone | Dominant Facies | Diagnostic Features |

|---|---|---|

| Steep Slope (Fault-Controlled) | Alluvial Fans (LFA 1) | Conglomerates raised on a matrix that has low sorting (sorting coefficient: 1.8–2.5); Seismic wedge geometries exhibit dips of 1520, and this shows progradation of fans along the fault scarp. |

| Central Depression (Subsidence-Dominated) | Floodplain mudstones (LFA 3) | Sand-mud rhythmic alternating sequences, root-marked paleosols and sheet-like sandbars with continuity of over 10–15 km, indicating long lake-time stability. |

| Gentle Slope (Progradational Margin) | Braided Rivers (LFA 2)/Fan Deltas (LFA 4) | Chlorite-coated sands containing intact porosity (12%–19%) sigmoid clinoforms indicating progradational stacking patterns, as well as lobate geometries of deltas that had an interval of vertical relief of 30 to 40 m. |

| Facies Association | Avg. Porosity | Key Controls | Exploration Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Braided Rivers (LFA 2) | 12%–19% | Chlorite grain coatings (5–10 μm) inhibit quartz overgrowth; moderate mechanical compaction (8% loss) | High-priority targets, especially on gentle slopes (e.g., Wudi Uplift); overpressure enhances secondary porosity by +3%–5% |

| Fan Deltas (LFA 4) | <8% | Calcite cementation (5%–15%); high ductile lithic content leads to severe compaction | Target fracture corridors near fault zones (10–50 μm); avoid interfan areas with high cementation |

| Floodplain mudstones (LFA 3) | 6%–9% | Illite-smectite pore-filling clays; permeability typically < 1 mD | Non-reservoir under normal conditions; may act as an effective seal unless fractured |

| Alluvial Fans (LFA 1) | 4%–7% | Matrix-supported conglomerates; intense compaction dominates diagenetic history | Poor reservoir potential; viable only with artificial stimulation or natural fracturing |

| Saline Lacustrine (LFA 5) | 3%–5% | Halite/gypsum dissolution creates localized secondary porosity | Potential secondary porosity zones near sequence boundaries (e.g., SB4); limited lateral continuity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Room, S.A.e.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Y.; Ahmad, W.; Nota, P.J.; Khan, A. Orbital-Scale Climate Control on Facies Architecture and Reservoir Heterogeneity: Evidence from the Eocene Fourth Member of the Shahejie Formation, Bonan Depression, China. Minerals 2026, 16, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010048

Room SAe, Zhang L, Yan Y, Ahmad W, Nota PJ, Khan A. Orbital-Scale Climate Control on Facies Architecture and Reservoir Heterogeneity: Evidence from the Eocene Fourth Member of the Shahejie Formation, Bonan Depression, China. Minerals. 2026; 16(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoom, Shahab Aman e, Liqiang Zhang, Yiming Yan, Waqar Ahmad, Paulo Joaquim Nota, and Aamir Khan. 2026. "Orbital-Scale Climate Control on Facies Architecture and Reservoir Heterogeneity: Evidence from the Eocene Fourth Member of the Shahejie Formation, Bonan Depression, China" Minerals 16, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010048

APA StyleRoom, S. A. e., Zhang, L., Yan, Y., Ahmad, W., Nota, P. J., & Khan, A. (2026). Orbital-Scale Climate Control on Facies Architecture and Reservoir Heterogeneity: Evidence from the Eocene Fourth Member of the Shahejie Formation, Bonan Depression, China. Minerals, 16(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/min16010048