Coordination-Driven Rare Earth Fractionation in Kuliokite-(Y), (Y,HREE)4Al(SiO4)2(OH)2F5: A Crystal–Chemical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Chemical Composition

2.3. Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

3. Results

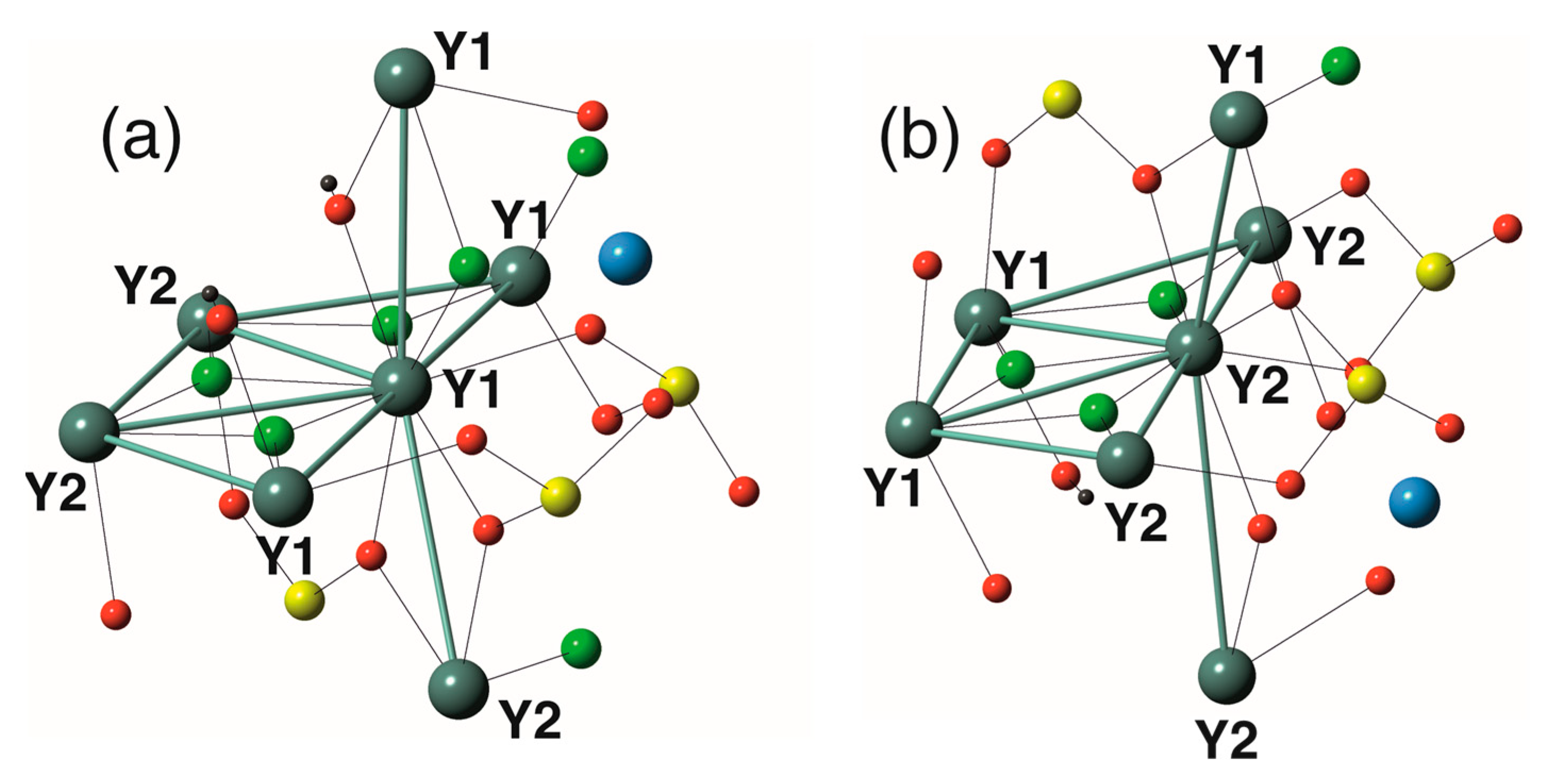

3.1. Cation Coordination and Site Assignment

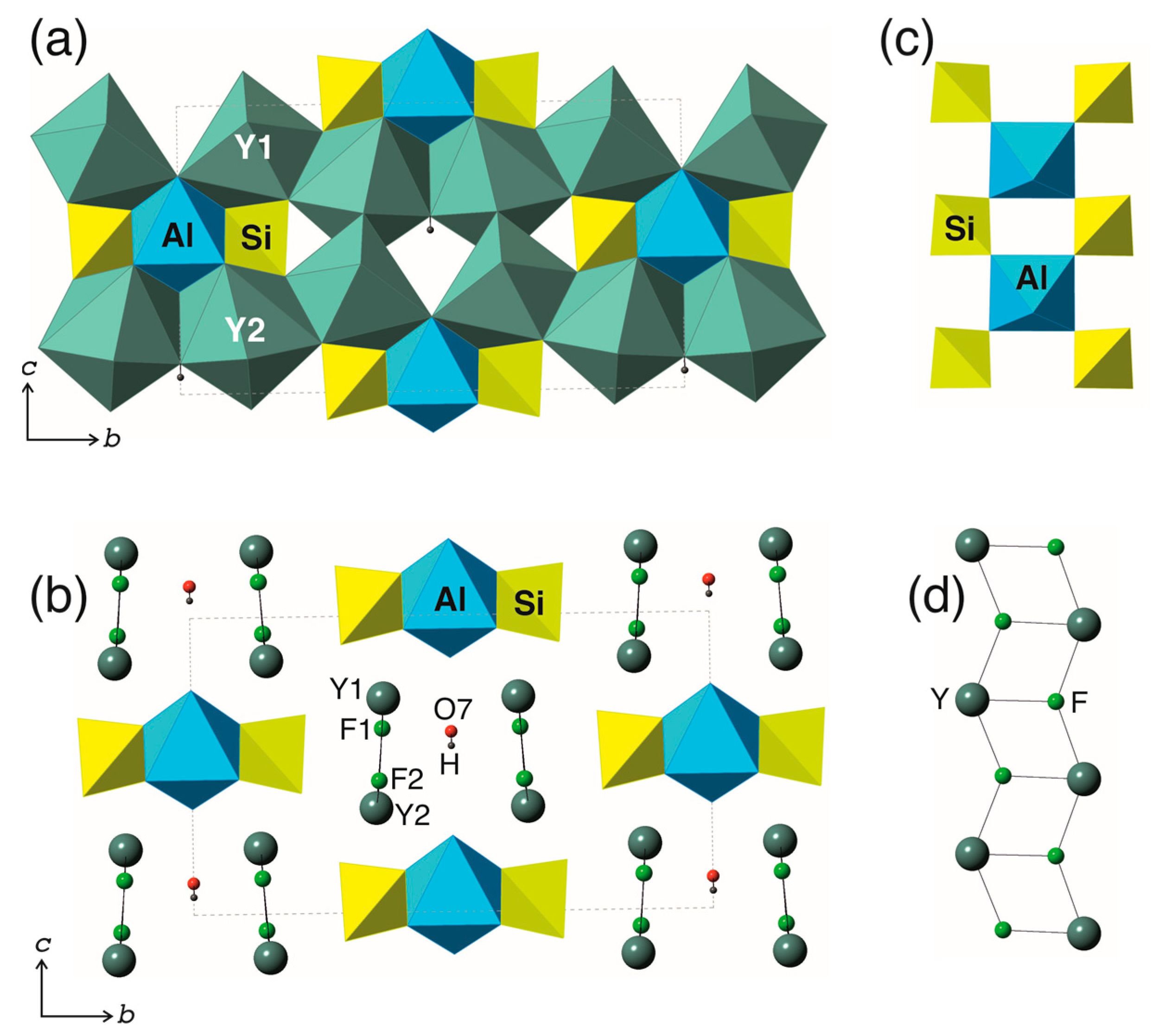

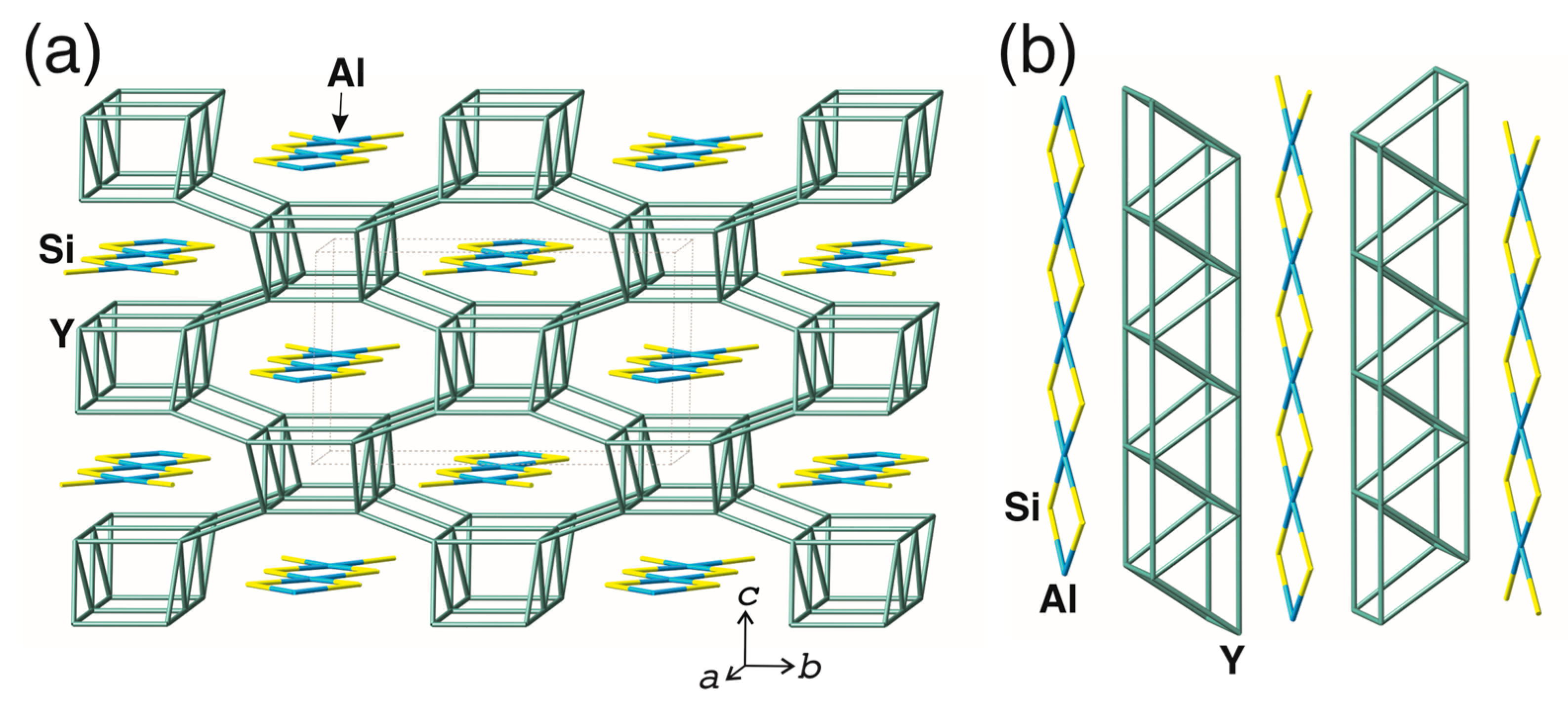

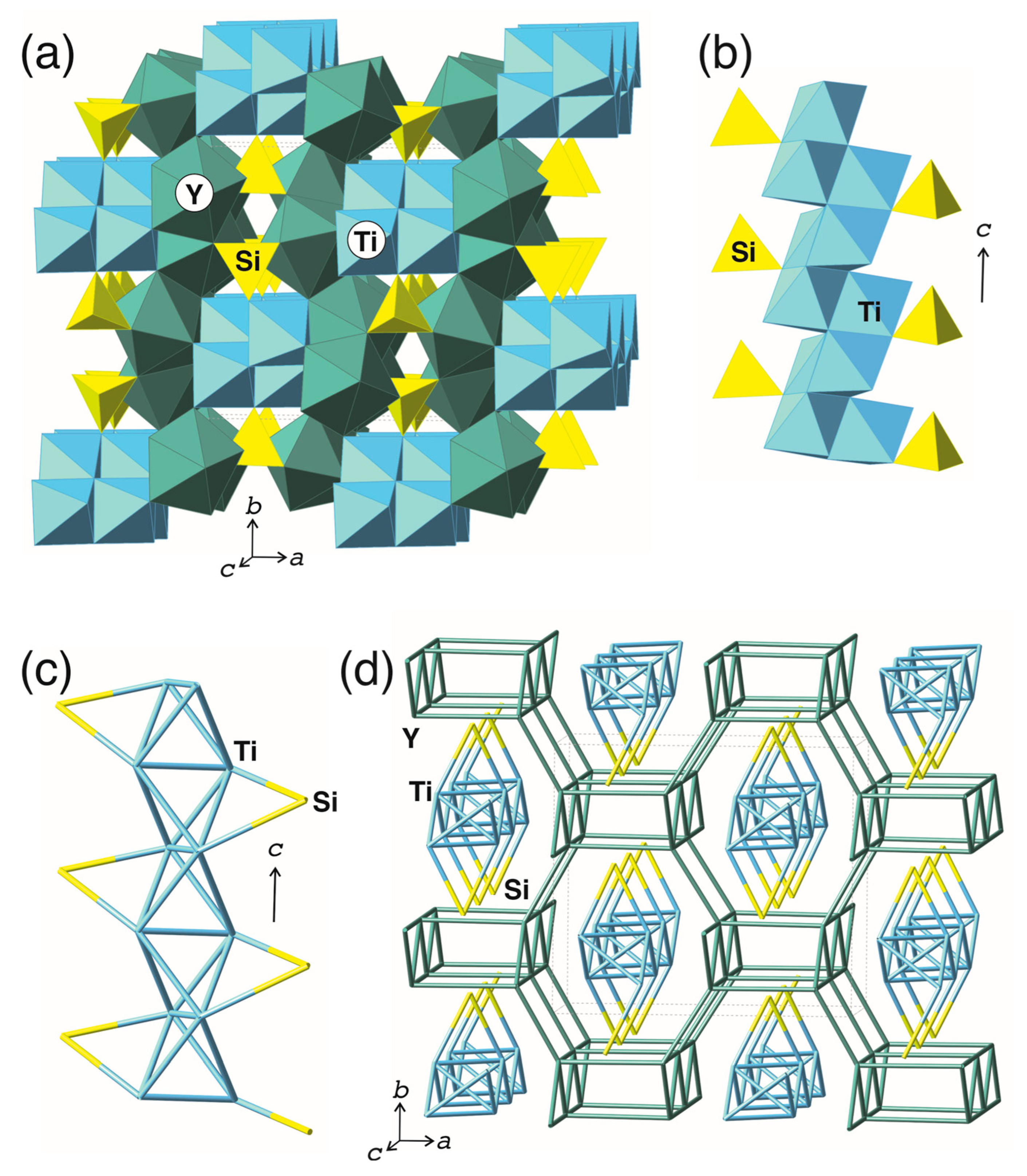

3.2. Structure Description

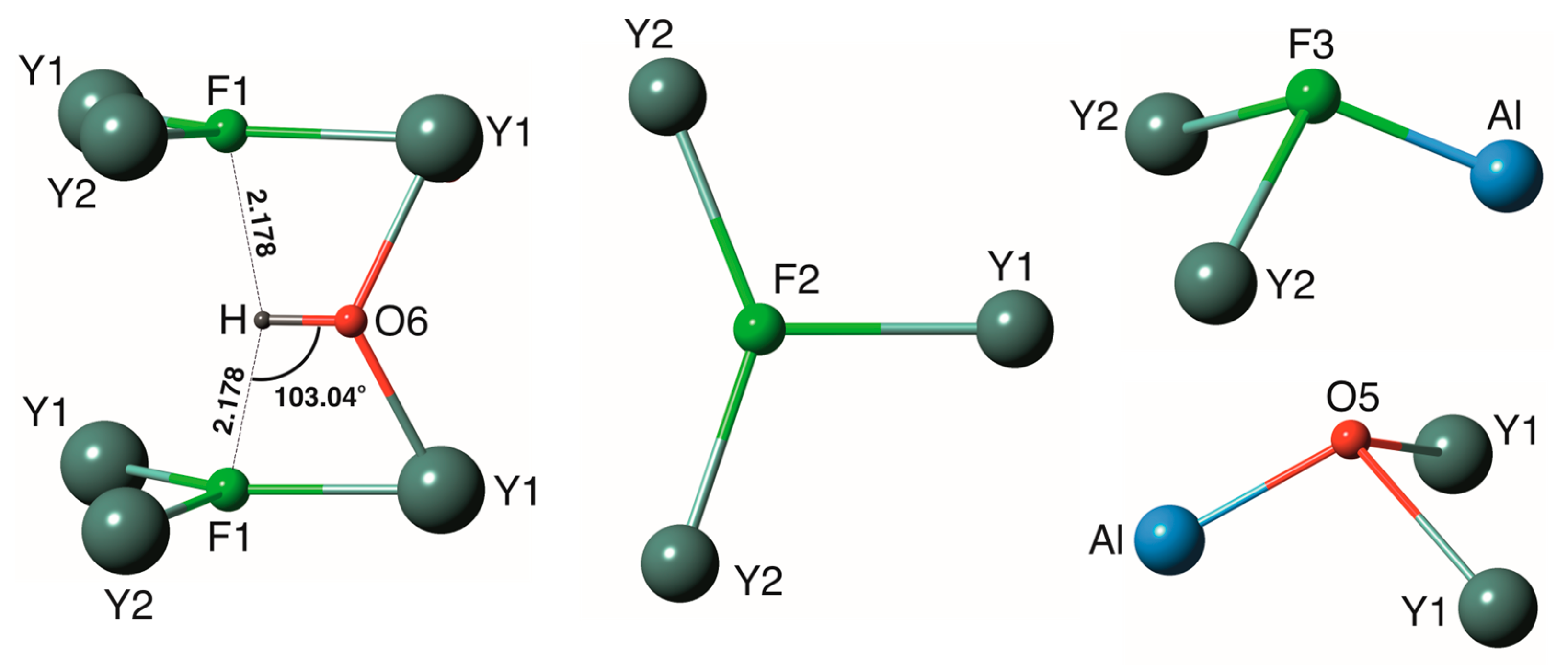

3.3. Hydrogen Bonding

4. Discussion

4.1. Rare Earth Fractionation

4.2. Chemical Formula and Nomenclature Considerations

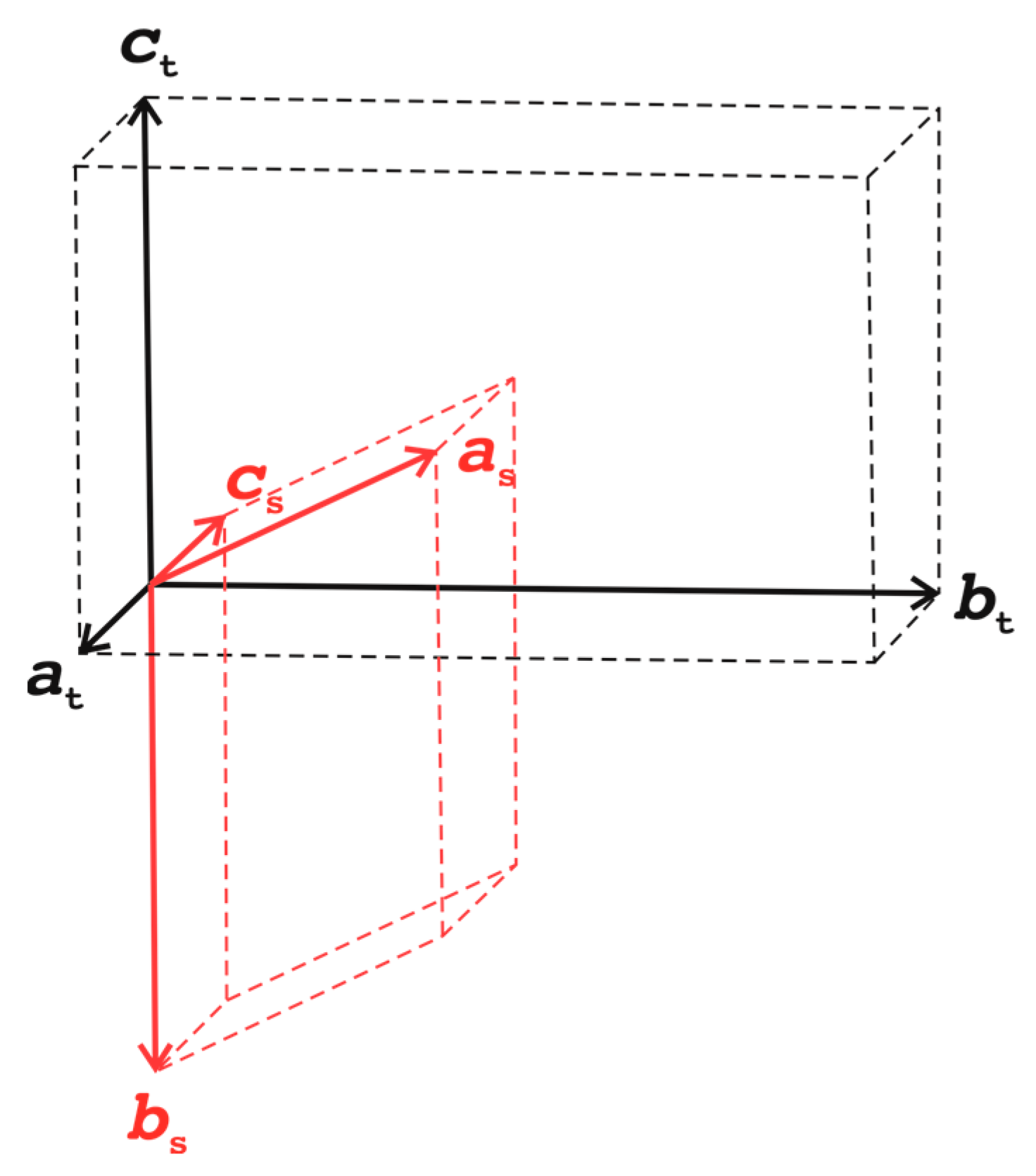

4.3. Optical Orientation

4.4. Comparison with Trimounsite

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalashnikov, A.O.; Konopleva, N.G.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Ivanyuk, G.Y. Rare Earth Deposits of the Murmansk Region, Russia—A Review. Econ. Geol. 2016, 111, 1529–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, K.M.; Wall, F.; Merriman, D. The Rare Earth Elements: Demand, Global Resources, and Challenges for Resourcing Future Generations. Nat. Resour. Res. 2018, 27, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, N.K.; Ayuso, R.A. Conventional Rare Earth Element Mineral Deposits—The Global Landscape. In Rare Earth Metals and Minerals Industries: Status and Prospects; Murty, Y.V., Alvin, M.A., Lifton, J.P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 17–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Ilton, E.S.; Wang, Z.; Rosso, K.M.; Zhang, X. Global Rare Earth Element Resources: A Concise Review. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 175, 106158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, P.; Han, Y. Rare Earth Elements Resources and Beneficiation: A Review. Miner. Eng. 2024, 218, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campostrini, I.; Demartin, F.; Finello, G.; Vignola, P. Aluminotaipingite-(CeCa), (Ce6Ca3)Al(SiO4)3[SiO3(OH)]4F3, a New Member of the Cerite-Supergroup Minerals. Miner. Mag. 2023, 87, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtstam, D.; Casey, P.; Bindi, L.; Förster, H.-J.; Karlsson, A.; Appelt, O. Fluorbritholite-(Nd), Ca2Nd3(SiO4)3F, a New and Key Mineral for Neodymium Sequestration in REE Skarns. Miner. Mag. 2023, 87, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, A.R.; Ma, C.; Marty, J. Chinleite-(Nd), NaNd(SO4)2(H2O), The Nd analogue of chinleite-(Y) from the Markey Mine, Red Canyon, San Juan County, Utah, USA. Can. J. Miner. Petrol. 2023, 61, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Gu, X.; Zhang, W.; Hu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Song, W.; Yu, M.; Cook, N.J. Jingwenite-(Y) from the Yushui Cu Deposit, South China: The First Occurrence of a V-HREE-Bearing Silicate Mineral. Am. Miner. 2023, 108, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykova, I.; Rowe, R.; Poirier, G.; Friis, H.; Helwig, K. Mckelveyite Group Minerals Part 2: Alicewilsonite-(YCe), Na2Sr2YCe(CO3)6·3H2O, a New Species. Eur. J. Miner. 2023, 35, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrejka, M.; Uher, P.; Ferenc, Š.; Majzlan, J.; Pollok, K.; Mikuš, T.; Milovská, S.; Molnárová, A.; Škoda, R.; Kopáčik, R.; et al. Monazite-(Gd), a New Gd-Dominant Mineral of the Monazite Group from the Zimná Voda REE-U-Au Quartz Vein, Prakovce, Western Carpathians, Slovakia. Miner. Mag. 2023, 87, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Števko, M.; Myšľan, P.; Biagioni, C.; Mauro, D.; Mikuš, T. Ferriandrosite-(Ce), a New Member of the Epidote Supergroup from Betliar, Slovakia. Miner. Mag. 2023, 87, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, X.; Dong, G.; Hou, Z.; Nestola, F.; Yang, Z.; Fan, G.; Wang, Y.; Qu, K. Calcioancylite-(La), (La,Ca)2(CO3)2(OH,H2O)2, a New Member of the Ancylite Group from Gejiu Nepheline Syenite, Yunnan Province, China. Miner. Mag. 2023, 87, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Gu, X.-P.; Rao, C.; Wang, R.-C.; Xing, X.-Q.; Wan, J.-J.; Zhong, F.-J.; Bonnetti, C. Gysinite-(La), PbLa(CO3)2(OH)H2O, a New Rare Earth Mineral of the Ancylite Group from the Saima Alkaline Complex, Liaoning Province, China. Miner. Mag. 2023, 87, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasatkin, A.V.; Zubkova, N.V.; Škoda, R.; Pekov, I.V.; Agakhanov, A.A.; Gurzhiy, V.V.; Ksenofontov, D.A.; Belakovskiy, D.I.; Kuznetsov, A.M. The Mineralogy of the Historical Mochalin Log REE Deposit, South Urals, Russia. Part V. Zilbermintsite-(La), (CaLa5)(Fe3+Al3Fe2+)[Si2O7][SiO4]5O(OH)3, a New Mineral with ET2 Type Structure and a Definition of the Radekškodaite Group. Miner. Mag. 2024, 88, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, G.; Sun, N.; Yao, W.; Yu, H.; Tian, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhao, F.; Cook, N.J. Wenlanzhangite–(Y) from the Yushui Deposit, South China: A Potential Proxy for Tracing the Redox State of Ore Formation. Am. Miner. 2024, 109, 1738–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykova, I.; Rowe, R.; Poirier, G.; Friis, H.; Helwig, K. Mckelveyite Group Minerals—Part 3: Bainbridgeite-(YCe), Na2Ba2YCe(CO3)6·3H2O, a New Species from Mont Saint-Hilaire, Canada. Eur. J. Miner. 2024, 36, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykova, I.; Rowe, R.; Poirier, G.; Friis, H.; Helwig, K. Mckelveyite Group Minerals—Part 4: Alicewilsonite-(YLa), Na2Sr2YLa(CO3)6·3H2O, a New Lanthanum-Dominant Species from the Paratoo Mine, Australia. Eur. J. Miner. 2024, 36, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrejka, M.; Bačík, P.; Majzlan, J.; Uher, P.; Ferenc, Š.; Mikuš, T.; Števko, M.; Čaplovičová, M.; Milovská, S.; Molnárová, A.; et al. Xenotime-(Gd), a New Gd-Dominant Mineral of the Xenotime Group from the Zimná Voda REE-U-Au Quartz Vein, Prakovce, Western Carpathians, Slovakia. Miner. Mag. 2024, 88, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekov, I.V.; Zubkova, N.V.; Kasatkin, A.V.; Chukanov, N.V.; Koshlyakova, N.N.; Ksenofontov, D.A.; Škoda, R.; Britvin, S.N.; Kirillov, A.S.; Zaitsev, A.N.; et al. Hydroxylbastnäsite-(La), an “old New” Bastnäsite-Group Mineral. Miner. Mag. 2024, 88, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczka, A.; Kristiansen, R.; Stachowicz, M.; Dumanska-Slowik, M.; Goleebiowska, B.; Seȩk, M.P.; Nejbert, K.; Kotowski, J.; Marciniak-Maliszewska, B.; Szuszkiewicz, A.; et al. Heflikite, Ideally Ca2(Al2Sc)(Si2O7)(SiO4)O(OH), the First Scandium Epidote-Supergroup Mineral from Jordanów Ślaȩski, Lower Silesia, Poland and from Heftetjern, Tordal, Norway. Miner. Mag. 2024, 88, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, H.; Liu, S.; Fan, H.; Gu, X.; Li, X.; Yang, K.; Wang, Q. Oboniobite and Scandio-fluoro-eckermannite, Two New Minerals in the Bayan Obo Deposit, Inner Mongolia. Chin. J. Geol. 2024, 59, 1466–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Du, W. High-Pressure Minerals and New Lunar Mineral Changesite-(Y) in Chang’e-5 Regolith. Matter Radiat. Extrem. 2024, 9, 027401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Liu, P.; Li, G.; Sun, N.; Yang, W.; Jiang, C.; Du, W.; Zhang, C.; Song, W.; Cook, N.J.; et al. Yuchuanite-(Y), Y2(CO3)3·H2O, a New Hydrous Yttrium Carbonate Mineral from the Yushui Cu Deposit, South China. Am. Miner. 2024, 109, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, D.; Yu, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Ren, J. Discovery and Geological Significance of New Mineral Tantalaeschynite-(Ce). Geol. Surv. China 2024, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, A.R.; Ma, C.; Marty, J. Chinleite-(Ce), NaCe(SO4)2(H2O), a new mineral from the Blue Streak Mine, Montrose County, Colorado, USA. Can. J. Miner. Petrol. 2025, 63, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcherek, T.; Schlüter, J.; Husdal, T. Anorthoyttrialite-(Y), Y4(SiO4)(Si3O10), a Natural Representative of B-Type Rare Earth Disilicates. Miner. Mag. 2025, 89, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plášil, J.; Steciuk, G.; Sejkora, J.; Kampf, A.R.; Uher, P.; Ondrejka, M.; Škoda, R.; Dolníček, Z.; Philippo, S.; Guennou, M.; et al. Extending the mineralogy of U6+ (I): Crystal structure of lepersonnite-(Gd) and a description of the new mineral lepersonnite-(Nd). Miner. Mag. 2025, 89. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plášil, J.; Steciuk, G.; Škoda, R.; Philippo, S.; Guennou, M. Extending the mineralogy of U6+ (III.): Pendevilleite-(Y), a new uranyl carbonate mineral from Kamoto-East Open-Cut, Democratic Republic of Congo. Miner. Mag. 2025, 89. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, H.M.; Cooper, M.A.; Cerny, P.; Grice, J.D.; Hawthorne, F.C. Xenotime-(Yb), YbPO4, a New Mineral Species from the Shatford Lake Pegmatite Group, Southeastern Manitoba, Canada. Can. Miner. 1999, 37, 1303–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, W.B.; Hanson, S.L.; Falster, A.U. samarskite-(Yb): A new species of the samarskite group from the Little Patsy pegmatite, Jefferson County, Colorado. Can. Miner. 2006, 44, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voloshin, A.V.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Men’shikov, Y.P.; Povarennykh, A.S.; Matvinenko, E.N.; Yakubovich, O.V. Hingganite-(Yb), a new mineral from amazonite pegmatites of the Kola Peninsula. Dokl. AN. SSSR 1983, 270, 1188–1192. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voloshin, A.V.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Tyusheva, F.N. Keiviite Yb2Si2O7—A new ytterbium silicate from amazonitic pegmatites of the Kola Peninsula. Mineral. Zhurnal 1983, 5, 94–99. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Voloshin, A.V.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A. Minerals and Evolution of Mineral Formation in Amazonitic Pegmatites of the Kola Peninsula; Nauka: Leningrad, Russia, 1986. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Voloshin, A.V.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A.; Tyusheva, F.N.; Sokolova, E.V.; Egorov-Tismenko, Y.K. Kuliokite-(Y)—new yttrium-aluminum fluorosilicate from amazonitic pegmatites of the Kola Peninsula. Mineral. Zhurnal 1986, 8, 94–99. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Raade, G.; Saebo, P.C.; Austrheim, H.; Kristiansen, R. Kuliokite-(Y) and its alteration products kainosite-(Y) and kamphaugite-(Y) from granite pegmatite in Tordal, Norway. Eur. J. Miner. 1993, 5, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husdal, T.A. The minerals of the pegmatites within the Tysfjord granite, Northern Norway. Nor. Bergverksmus. Skr. 2008, 38, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, E.V.; Egorov-Tismenko, Y.K.; Voloshin, A.V.; Pakhomovskii, Y.A. Crystal structure of the new Y-Al silicate kuliokite-(Y), Y4Al[SiO4]2(OH)2F5. Sov. Phys. Crystallogr. 1986, 31, 601–603. [Google Scholar]

- Agilent Technologies. CrysAlisPro, Version 1.171.36.20; Agilent Technologies: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2012.

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, A.L. Single-Crystal Structure Validation with the Program It PLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flack, H.D. On enantiomorph-polarity estimation. Acta Crystallogr. A 1983, 39, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, O.C.; Hawthorne, F.C. Comprehensive Derivation of Bond-Valence Parameters for Ion Pairs Involving Oxygen. Acta Crystallogr. B 2015, 71, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brese, N.E.; O’Keeffe, M. Bond-Valence Parameters for Solids. Acta Crystallogr. B 1991, 47, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandurkin, G.A.; Dzhurinskii, B.F.; Tananaev, I.V. Pecularities of Crystal Chemistry of Rare Earth Compounds; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1984; p. 230. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, R.B. Lanthanide Contraction: What Is Normal? Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 3715–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.A.; Djanashvili, K.; Geraldes, C.F.G.C.; Platas-Iglesias, C. The Chemical Consequences of the Gradual Decrease of the Ionic Radius along the Ln-Series. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 406, 213146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, F.C.; Gagné, O.C. New Ion Radii for Oxides and Oxysalts, Fluorides, Chlorides and Nitrides. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 80, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleid, T.; Müller-Bunz, H. Einkristalle von Y3F[Si3O10] Im Thalenit-Typ. Z. Für Anorg. Und Allg. Chem. 1998, 624, 1082–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škoda, R.; Plášil, J.; Jonsson, E.; Čopjaková, R.; Langhof, J.; Galiová, M.V. Redefinition of Thalénite-(Y) and Discreditation of Fluorthalénite-(Y): A Re-Investigation of Type Material from the Österby Pegmatite, Dalarna, Sweden, and from Additional Localities. Miner. Mag. 2015, 79, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Moore, P.B. Crystal structure of cappelenite, Ba(Y,RE)6[Si3Be6O24]F2: A silicoborate sheet structure. Am. Miner. 1984, 69, 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Krivovichev, S.V. Structure Description, Interpretation and Classification in Mineralogical Crystallography. Crystallogr. Rev. 2017, 23, 2–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivovichev, S.V. Topology of Microporous Structures. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 2005, 57, 17–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, M.; Peskov, M.A.; Ramsden, S.J.; Yaghi, O.M. The Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource (RCSR) Database of, and Symbols for, Crystal Nets. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1782–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource. Available online: http://rcsr.net/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Krivovichev, S.V. Which Nets Are the Most Common? Reticular Chemistry and Information Entropy. CrystEngComm 2024, 26, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara Topological Data Center. Available online: https://topcryst.com/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Haase, M.G.; Günther, W.; Görls, H.; Anders, E. N-Heteroarylphosphonates, Part II. Synthesis and Reactions of 2- and 4-Phosphonatoquinolines and Related Compounds. Synthesis 1999, 1999, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, J.; Ejaz; Khan, I.U.; Harrison, W.T.A. N-(4-Aminophenyl)-4-Methylbenzene-Sulfonamide. Acta Crystallogr. E 2011, 67, o2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, K.; Kojima, T.; Ikeda, Y. Solid Form Selection of Highly Solvating TAK-441 Exhibiting Solvate-Trapping Polymorphism. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 3335–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, G.A. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 1997; p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Yakubovich, O.V.; Massa, W.; Pekov, I.V.; Gavrilenko, P.G. Crystal Structure of Tveitite-(Y): Fractionation of Rare-Earth Elements between Positions and the Variety of Defects. Crystallogr. Rep. 2007, 52, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatehouse, B.M.; Grey, I.E.; Kelly, P.R. The Crystal Structure of Davidite. Am. Miner. 1979, 64, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Pushcharovsky, D.Y. Structures and Properties of Crystals; GEOS: Moscow, Russia, 2022; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Piret, P.; Deliens, M.; Pinet, M. La trimounsite-(Y), nouveau silicotitanate de terres rares de Trimouns, Ariege, France; (TR)2Ti2SiO9. Eur. J. Miner. 1990, 2, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolitsch, U. The crystal structure of trimounsite-(Y), (Y,REE)2Ti2SiO9: An unusual TiO6-based titanate chain. Eur. J. Miner. 2001, 13, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, L.; Nespolo, M.; Krivovichev, S.V.; Chapuis, G.; Biagioni, C. Producing Highly Complicated Materials. Nature Does It Better. Rep. Progr. Phys. 2020, 83, 106501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Oxide | 1 | 2 | 3 | Average | Atom | 1 | 2 | 3 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 | 5.76 | 5.94 | 6.11 | 5.94 | Al | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.92 |

| SiO2 | 15.36 | 15.55 | 15.68 | 15.53 | Si | 2.05 | 2.04 | 2.03 | 2.04 |

| CaO | – | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.07 | Ca | – | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Y2O3 | 40.32 | 41.68 | 45.10 | 42.37 | Y | 2.86 | 2.91 | 3.11 | 2.96 |

| Gd2O3 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.30 | Gd | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Dy2O3 | 2.69 | 2.90 | 3.34 | 2.98 | Dy | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Ho2O3 | 0.98 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 1.09 | Ho | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Er2O3 | 6.69 | 6.59 | 6.35 | 6.54 | Er | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| Tm2O3 | 1.87 | 1.71 | 1.41 | 1.66 | Tm | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Yb2O3 | 14.46 | 13.04 | 9.48 | 12.33 | Yb | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.49 |

| Lu2O3 | 1.61 | 1.47 | 0.76 | 1.28 | Lu | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| F | 10.45 | 10.45 | 10.99 | 10.63 | F | 4.41 | 4.34 | 4.50 | 4.42 |

| 100.46 | 100.98 | 100.68 | 100.71 | OH | 2.64 | 2.68 | 2.52 | 2.61 | |

| –O=F2 | −4.40 | −4.40 | −4.63 | −4.48 | <SSF>, e− | 48.23 | 47.41 | 46.14 | 47.31 |

| H2Ocalc * | 2.97 | 3.07 | 2.92 | 2.99 | |||||

| Total | 99.03 | 99.65 | 98.97 | 99.22 |

| Temperature (K) | 293(2) |

| Crystal system | monoclinic |

| Space group | Im |

| a (Å) | 4.32130(10) |

| b (Å) | 14.8123(6) |

| c (Å) | 8.6857(3) |

| β (o) | 102.872(4) |

| Volume (Å3) | 541.99(3) |

| Z | 2 |

| ρcalc (g/cm3) | 4.723 |

| μ (mm−1) | 24.620 |

| F(000) | 702 |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.17 × 0.12 × 0.10 |

| Radiation | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 9.56–82.14 |

| Index ranges | −7 ≤ h ≤ 7, −27 ≤ k ≤ 26, −15 ≤ l ≤ 15 |

| Reflections collected | 8540 |

| Independent reflections | 3202 [Rint = 0.0301, Rsigma = 0.0428] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 3202/3/117 |

| Flack parameter | 0.969(12) |

| Goodness-of-fit (S) on F2 | 1.153 |

| Weighting scheme | W = 1/[S2(Fo2) + (0.0578P)2 + 1.6209P], where P = (Fo2 + 2Fc2)/3 |

| Final R indexes [I ≥ 4σ(I)] | R1 = 0.030, wR2 = 0.087 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.030, wR2 = 0.087 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole/e Å−3 | 3.434/−2.366 |

| Site | Occupancy | x | y | z | Uiso | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 | Y0.84Yb0.16 | 0.46546(8) | 0.36988(3) | 0.72252(5) | 0.0053(1) | ||||

| Y2 | Y0.69Yb0.31 | 0.28434(5) | 0.14586(2) | 0.85270(4) | 0.0053(1) | ||||

| Si | Si | 0.6186(4) | 0.1555(1) | 0.5428(2) | 0.0045(3) | ||||

| Al | Al | 0.1137(6) | 0 | 0.5499(3) | 0.0056(4) | ||||

| O1 | O | 0.7421(10) | 0.2101(3) | 0.4058(5) | 0.0089(6) | ||||

| O2 | O | 0.4979(10) | 0.2189(3) | 0.6712(5) | 0.0086(6) | ||||

| O3 | O | 0.3275(9) | 0.0900(3) | 0.4551(5) | 0.0063(6) | ||||

| O4 | O | 0.9081(10) | 0.0925(3) | 0.6426(5) | 0.0072(6) | ||||

| F1 | F | 0.4270(10) | 0.1329(3) | 0.1207(6) | 0.0120(7) | ||||

| F2 | F | −0.171(1) | 0.1398(3) | 0.9452(6) | 0.0111(7) | ||||

| F3 | F0.5(OH)0.5 * | 0.4082(14) | 0 | 0.7581(7) | 0.0102(8) | ||||

| O5 | OH | 0.3136(14) | ½ | 0.8570(8) | 0.0092(8) | ||||

| O6 | OH | 0.538(2) | ½ | 0.6077(10) | 0.019(1) | ||||

| H | H | 0.72(5) | ½ | 0.56(4) | 0.080 * | ||||

| Site | U11 | U22 | U33 | U23 | U12 | U13 | |||

| Y1 | 0.0057(2) | 0.0056(2) | 0.0048(2) | −0.0009(1) | 0.0018(1) | −0.0003(1) | |||

| Y2 | 0.0055(1) | 0.0057(1) | 0.0049(1) | −0.0008(1) | 0.00181(9) | −0.0004(1) | |||

| Si | 0.0050(5) | 0.0048(6) | 0.0042(5) | 0.0000(5) | 0.0020(4) | 0.0002(4) | |||

| Al | 0.0062(8) | 0.0049(9) | 0.0057(9) | 0 | 0.0015(6) | 0 | |||

| O1 | 0.0127(14) | 0.0072(14) | 0.0082(14) | 0.0035(11) | 0.006(1) | 0.001(12) | |||

| O2 | 0.0139(15) | 0.0056(13) | 0.0075(14) | −0.0003(11) | 0.005(1) | −0.000(1) | |||

| O3 | 0.0046(12) | 0.0084(14) | 0.0060(13) | 0.0002(10) | 0.001(1) | −0.001(1) | |||

| O4 | 0.0063(12) | 0.0083(14) | 0.0061(14) | −0.0001(10) | −0.000(1) | 0.001(1) | |||

| F1 | 0.0078(15) | 0.0200(19) | 0.0084(17) | 0.0014(12) | 0.002(1) | 0.001(1) | |||

| F2 | 0.0061(14) | 0.0193(18) | 0.0085(18) | 0.0004(11) | 0.003(1) | −0.000(1) | |||

| F3 | 0.0102(19) | 0.009(2) | 0.010(2) | 0 | −0.001(2) | 0 | |||

| O5 | 0.010(2) | 0.0081(19) | 0.009(2) | 0 | 0.0003(16) | 0 | |||

| O6 | 0.039(4) | 0.007(2) | 0.017(3) | 0 | 0.019(3) | 0 | |||

| Y1–O6 | 2.225(4) | Y2–O1 | 2.199(4) |

| Y1–O2 | 2.291(4) | Y2–O2 | 2.270(4) |

| Y1–F1 | 2.298(5) | Y2–F1 | 2.280(5) |

| Y1–O3 | 2.340(4) | Y2–F2 | 2.288(4) |

| Y1–F2 | 2.353(5) | Y2–O4 | 2.297(4) |

| Y1–F1 | 2.355(5) | Y2–F2 | 2.312(4) |

| Y1–O1 | 2.357(4) | Y2–F3 | 2.413(3) |

| Y1–O5 | 2.419(4) | <Y2–X *> | 2.294 |

| <Y1–X *> | 2.330 | ||

| Si–O1 | 1.624(4) | ||

| Al–O5 | 1.877(7) | Si–O2 | 1.629(4) |

| Al–O4 | 1.906(4) 2× | Si–O3 | 1.637(4) |

| Al–O3 | 1.910(5) 2× | Si–O4 | 1.644(4) |

| Al–F3 | 1.966(6) | <Si–O> | 1.634 |

| <Al–X *> | 1.913 |

| Atom | O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | F1 | F2 | F3 | O5 | O6 | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.34, 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.34 2×↓ | 0.55 2×↓ | 3.09 | ||

| Y2 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.33, 0.35 | 0.25 2×↓ | 2.82 | |||

| Al | 0.50 2×→ | 0.50 2×→ | 0.43 | 0.54 | 2.97 | |||||

| Si | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 3.91 | |||||

| Σ | 1.97 | 1.94 | 1.88 | 1.91 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.22 | 1.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krivovichev, S.V.; Yakovenchuk, V.N.; Goychuk, O.F.; Pakhomovsky, Y.A. Coordination-Driven Rare Earth Fractionation in Kuliokite-(Y), (Y,HREE)4Al(SiO4)2(OH)2F5: A Crystal–Chemical Study. Minerals 2025, 15, 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15101064

Krivovichev SV, Yakovenchuk VN, Goychuk OF, Pakhomovsky YA. Coordination-Driven Rare Earth Fractionation in Kuliokite-(Y), (Y,HREE)4Al(SiO4)2(OH)2F5: A Crystal–Chemical Study. Minerals. 2025; 15(10):1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15101064

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrivovichev, Sergey V., Victor N. Yakovenchuk, Olga F. Goychuk, and Yakov A. Pakhomovsky. 2025. "Coordination-Driven Rare Earth Fractionation in Kuliokite-(Y), (Y,HREE)4Al(SiO4)2(OH)2F5: A Crystal–Chemical Study" Minerals 15, no. 10: 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15101064

APA StyleKrivovichev, S. V., Yakovenchuk, V. N., Goychuk, O. F., & Pakhomovsky, Y. A. (2025). Coordination-Driven Rare Earth Fractionation in Kuliokite-(Y), (Y,HREE)4Al(SiO4)2(OH)2F5: A Crystal–Chemical Study. Minerals, 15(10), 1064. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15101064