Abstract

Truck platooning enabled by V2X and cooperative driving can reduce aerodynamic drag and consequently decrease fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. Meanwhile, hub-and-spoke courier networks require strategic decisions on hub locations, allocation, and line-haul routing. This paper introduces an integrated Hub Location-Platoon Routing Problem (HLPRP) that jointly optimizes (i) hub selection and single allocation of spokes; (ii) the departure hubs where platoons are formed; (iii) line-haul (inter-hub) service design and route selection; and (iv) demand routing, while internalizing monetized carbon benefits from platooning. A variable neighborhood search-based simulated annealing solution framework is developed to eliminate duplicated hub pair representations induced by network symmetry. Computational experiments on benchmark and large-scale North China instances demonstrate that the proposed approach consistently produces high-quality solutions within practical runtimes. The results indicate that the optimal network structure is primarily driven by transportation cost trade-offs and is further shaped by platoon-enabling investment and the associated carbon benefit, which concentrates on a subset of high-volume inter-hub corridors. Overall, the proposed framework provides a decision support approach for designing low-carbon courier line-haul networks.

1. Introduction

Intelligent connected truck platooning has been widely recognized as a promising technology for improving road freight efficiency, safety, and sustainability. By maintaining short inter-vehicle gaps via cooperative control, a platoon can reduce aerodynamic resistance and thus fuel use and emissions. However, the magnitude of these benefits depends strongly on where platoons can be formed and which corridors they operate on, which are strategic network design decisions. In courier line-haul networks, strategic hub location and service-network design are traditionally optimized without explicitly modeling platoon formation and carbon impacts.

The traditional location and routing problem concerns the strategic decisions of selecting appropriate nodes as hubs and routing traffic through the resulting network. This study is motivated by the operational characteristics of courier line-haul networks and the emerging opportunity of intelligent connected truck platooning. Courier systems are typically organized as hub-and-spoke networks, where hubs serve as consolidation facilities that collect flows from non-hub branch offices and from other hubs, while branch offices generate original pickup-delivery demands. At hubs, loading, unloading, sorting, and cross-docking operations are performed. Branch offices are customarily assigned to a hub mainly for management and operational convenience. The branch-to-hub legs are usually short-distance with relatively small volumes. Therefore, ground transportation is commonly adopted for moving parcels from branches to hubs. Consistent with practice in China, only ground transportation is considered in this paper as the dominant mode for parcel delivery firms.

Beyond conventional hub location-allocation and line-haul routing, truck platooning introduces a new strategic dimension. Platooning benefits (fuel savings and emission reductions) are realized primarily in line-haul corridors and depend critically on where platoons can be formed and which inter-hub routes they operate on. In courier networks, hubs are natural coordination points for platooning because they already perform consolidation and scheduling activities. However, not all hubs are equally suitable for platoon formation due to differences in infrastructure, operational capabilities, and the ability to synchronize departures. Therefore, strategic network design should explicitly determine (i) which hubs are selected and how branches are allocated, (ii) which hubs are platoon-capable departure points, and (iii) which inter-hub services (corridors) are designated for platoon operations so that carbon and cost impacts can be evaluated endogenously.

Accordingly, two interrelated network layers are designed in this study: the physical network and the service (trip) network. The physical network design includes hub locations and the allocation of non-hub nodes, while the service network design specifies the provision and routing of inter-hub line-haul services that carry consolidated flows. The physical network design is closely related to classic hub location models. For service network design, interested readers may refer to [1,2]. In the proposed platooning-oriented setting, the service network is further enriched by distinguishing platoon-operated line-haul services from conventional services, reflecting that only selected corridors (and corresponding operational plans) can deliver platooning benefits.

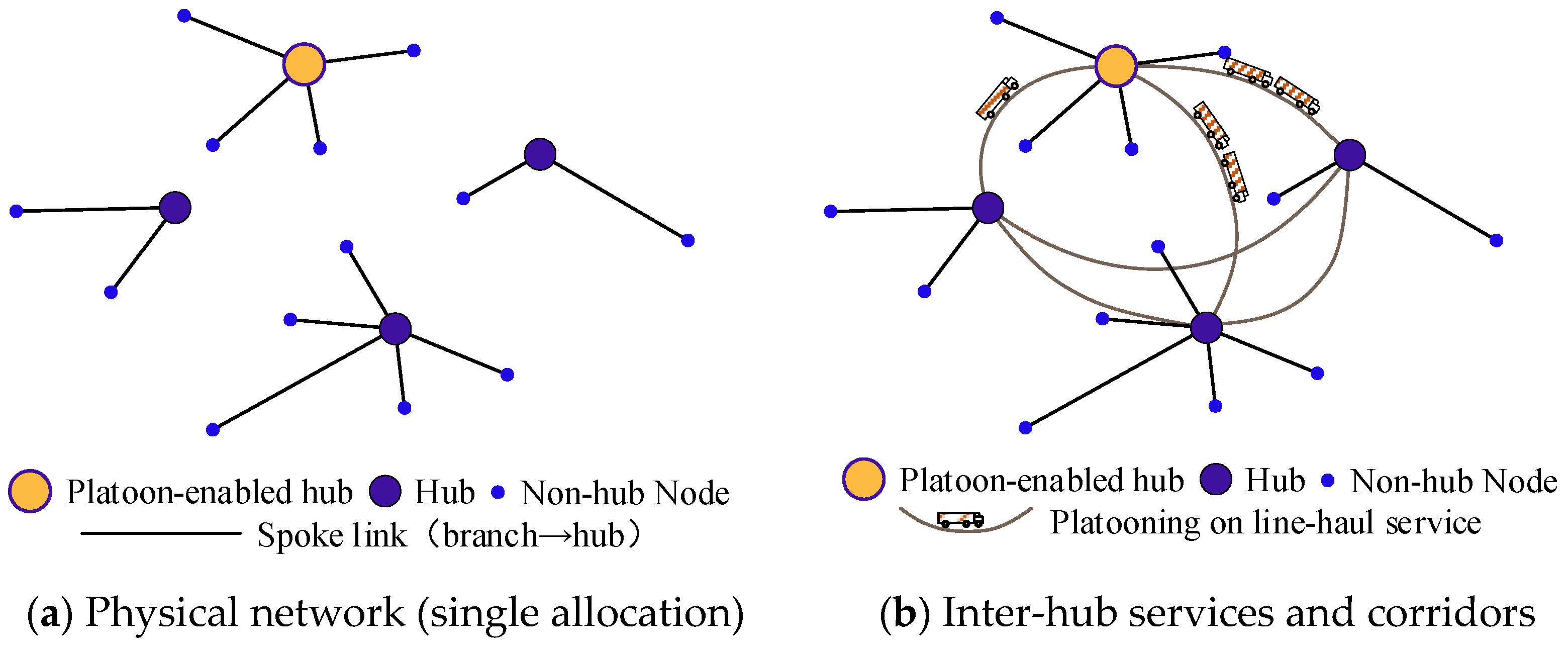

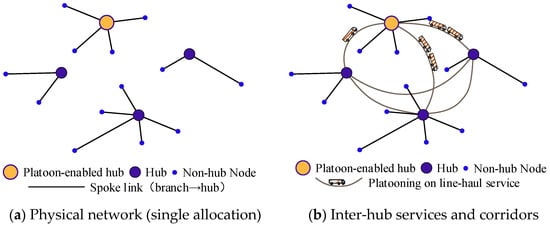

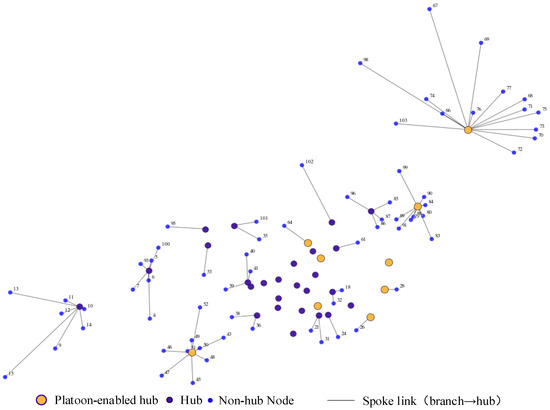

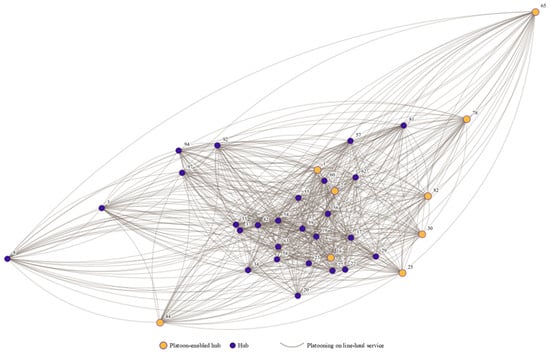

As illustrated in Figure 1a, a branch of nodes is selected as hubs (purple circles), and each non-hub node (blue circle) is assigned to exactly one hub, forming spoke links and geographically compact hub-spoke clusters. Platoon-enabled hubs (yellow circles) are the hubs where platooning departures can be organized. The inter-hub line-haul services are activated between selected hub pairs and operated along a chosen corridor from a set of candidates, as shown in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

Platooning on line-haul service.

Several cost components are considered in establishing and operating the courier network. These include the fixed cost of building hub facilities and opening line-haul services/links, as well as material-handling costs associated with loading, unloading, sorting, and cross-docking at hubs. Material-handling costs may vary by hub location due to differences in labor and utility prices. The consolidation process at hubs is analogous to the accumulation of traffic flows in the classification yard of railway transportation [3,4]. A consolidation coefficient is introduced to describe how flows are aggregated at hubs, and demand arrivals are assumed to be uniformly distributed. In addition to these conventional components, the platooning setting motivates incorporating platoon-related operational considerations (e.g., platoon-capability investment or coordination requirements at departure hubs) and carbon impacts associated with line-haul operations, so that the trade-offs between cost efficiency and sustainability can be quantified at the strategic planning level.

The purpose of this study is to develop a quality solution for a platooning-enhanced location and routing problem in courier networks at the strategic level. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

- (i)

- The hub location platoon routing problem (HLPRP), jointly optimizing hub locations, single allocations, platoon-enabled departure hubs, and inter-hub route selection, is formulated as a mixed-integer linear programming model.

- (ii)

- The monetized carbon benefits are incorporated into the objective function via an emission-reduction model tied to platoon-operated line-haul routes.

- (iii)

- A hybrid solution approach that decomposes physical network design and service network routing is designed to remove duplicated directed-pair representation caused by network symmetry, enabling scalability to realistic instances.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Hub Location in Hub-And-Spoke Courier Networks

In the courier delivery network, hubs serve as the consolidation centers for demands from the non-hub nodes. Usually, the hubs are interconnected, while the non-hub nodes have to ship their traffic through hubs. When designing the delivery network, a deterministic number p of nodes is selected as hubs, and other nodes are allocated to one or multiple hubs. The p-hub median problem can be referred to Campbell [5]; in their research, both the single and multiple allocation p-hub median problems are investigated, and heuristics are developed to solve the problem. Talbi and Todosijević [6] introduced an ingenious approach to quantify the robustness of a solution in the presence of uncertainties, with the property providing a solution that is robust for any realization of the number of changes that might occur. Ghaffarinasab [7] investigated a robust, incapacitated, multiple-allocation p-hub median problem in which OD demand was treated as uncertain. Two exact Bender decomposition-based procedures were proposed and validated through extensive computational experiments. Wang et al. [8] extended single-allocation hub location by introducing demand stratification, where nodes belong to different strata (e.g., service types) and must be served under heterogeneous requirements.

Generally, the location-allocation problem is to determine the optimal locations of facilities (hubs) to serve the demands and to allocate the demand nodes to the hubs. Berman and Mandowsky [9] dealt with the location-allocation decisions in networks under conditions of congestion incurred by the possible arrival of demands when no server is available. Chen et al. [10] built a model to minimize location cost and maximize customer distance satisfaction, considering the characteristics of an express logistics system. Except for the allocation of non-hub nodes to hub nodes, the allocation problem can also include the resource allocation in the network. For example, Cheng et al. [11] formulated a two-stage stochastic resource-allocation and facility location-allocation model for disaster response, where the uncertain availability of relief supplies, casualty levels, and hospital responsiveness was represented via discrete scenarios.

In the hub-and-spoke network, the location and routing problem concerns finding the best location of hubs and designing routes to transport the demands from the customers. Ghaderi and Burdett [12] formulated the strategic location-routing problem as a two stage-stochastic program, in which strategic decisions are made concerning the location of transfer yards, and then hazmat routing is performed. Bayram et al. [13] extended classical hub locations by jointly optimizing hub locations, capacity acquisition, and dynamic OD routing while accounting for congestion and demand uncertainty. Cuzzocrea et al. [14] formulated hub location under demand uncertainty as a two-stage model in which hub locations are selected in the first stage and node allocations are optimized as second-stage recourse.

In summary, hub location and location-allocation studies have established rich modeling and algorithmic foundations, including extensions under uncertainty and congestion. However, in hub-and-spoke courier systems, the joint treatment of hub selection with inter-hub service design decisions that shape the line-haul layer is still limited, especially when additional operational mechanisms, such as platoon-enabling investments and monetized carbon benefits, are considered. This gap motivates the present study.

2.2. Service Network Design

Service network design (SND) is widely used as a tactical-planning paradigm for consolidation-based freight carriers, where a subset of services is activated, and shipment flows are routed to balance transportation cost and network operating constraints. Early work (for example, Powell [15]) framed Less-than-Truckload (LTL) network planning as a fixed-charge network design problem and developed local-improvement heuristics to add or drop services under practical operating requirements efficiently. Jarrah et al. [16] advanced large-scale formulations tailored to LTL practice, enabling tractable optimization on realistically sized networks and providing a baseline for later extensions in schedules and resource coupling. Multi-layer service network design frameworks have been proposed to model carrier planning problems as interconnected layers, where an arc in one layer is defined through a set of arcs in another layer, and all layers are designed jointly to satisfy OD demand at minimum total cost [17].

Beyond service design and flow assignment on a fixed set of candidate links, integrated SND models explicitly combine routing choice and resource feasibility [18]. In particular, in the resource-constrained project scheduling problem, activity sequencing decisions are optimized jointly with resource feasibility requirements under complex precedence structures [19]. Bilegan et al. [2] integrated revenue management into scheduled service network design for intermodal consolidation carriers by jointly selecting services and schedules, routing demand, and allocating the key operating resources. In scheduled settings, Hewitt [20] proposes a flexible variant of the scheduled service network design problem that selects a limited set of shipments whose available times are adjusted to increase consolidation opportunities and reduce total transportation and handling costs. Hewitt and Lehuédé [21] propose new formulations in which model consolidations are more direct and also improve tractability and relaxation strength.

A growing trend of SND research explicitly includes carbon emissions in network planning so that the selected services and routed flows are evaluated not only according to transportation and handling costs but also the emission cost implied by a carbon price or carbon tax. In most models, emissions are computed from distance, mode, and load. This framework is widely used in freight network and network design studies [22]. For intermodal systems, carbon emissions are often modeled together with service selection and routing decisions. Representative intermodal service network design studies include greenhouse gas emissions as an explicit objective or as a monetized cost and examine how the trade-off among transportation cost, service time, and emissions reshapes the chosen services, routes, and mode combinations [23,24]. Service network planning has also been connected to fleet transition and decarbonization decisions, where emissions parameters are embedded in network optimization to evaluate the operational impact of adopting cleaner assets [25]. These studies provide the most relevant progress for extending classical SND toward low-emission operations, where carbon effects are not only evaluated but are also driven by explicit design and investment choices.

In many strategic courier planning settings, road distances and the resulting baseline emissions are treated as symmetric. Nevertheless, inter-hub service decisions are often indexed by directed hub pairs in existing hub location and service network formulations, even when the two directions correspond to the same physical corridor under symmetric costs. As a result, duplicated representations are introduced, which enlarges the decision space and leads to redundant evaluations in heuristic search. This issue becomes particularly salient in integrated hub-and-spoke planning, because the number of candidate inter-hub services scales quadratically with the number of hubs. Despite extensive research on hub location, service network design, and platooning, an explicit symmetry modeling treatment that removes such duplicated hub pair representations within an integrated planning framework has remained limited.

2.3. Truck Platooning: Planning and Routing

Truck platooning coordinates multiple trucks to travel in close formation so that aerodynamic drag is reduced and fuel consumption is lowered [25,26]. In planning models, the key decision is not only whether platooning is used, but where and when vehicles are synchronized (meeting, waiting, merging, or splitting) and how those synchronization choices interact with routing, scheduling, and practical constraints, such as time windows, congestion patterns, driver rules, and platoon size limits [27].

The coordination of policies and schedules has been widely studied to increase platoon formation opportunities while controlling delays. Vehicle-to-platoon assignment models adjust the matching and timing of individual vehicles to nearby platoons in real time, with the goal of reducing total energy use at the system level [28]. Integrated routing, scheduling, and platoon formation have also been addressed in operational problems. Platooning is embedded into vehicle routing and timing decisions [29]. Platoon formation with time window constraints is modeled on time–space networks to limit detours and delays while still capturing fuel savings [30]. In freight and terminal operations, autonomous truck scheduling models incorporate platooning and speed decisions when coordinating container transshipment between terminals. Practical constraints are increasingly incorporated, including driver mandatory breaks, intermediate relay requirements, state-dependent fuel-saving rates, and platoon size limits [31].

Platooning has additionally been connected to network design and infrastructure planning. Dedicated platoon lane planning is formulated as a spatiotemporal network design problem that selects where dedicated lanes are deployed and specifies their operating hours [32]. In addition, corridor-oriented platooning network models represent platoon operations through coupling/decoupling locations and quantify economic gains that are largely attributed to driver compensation savings under hybrid platooning operations [33].

The recent literature shows that platooning benefits depend on coordinated decisions across multiple levels, ranging from vehicle matching and schedule alignment to network and corridor design. These studies make it clear that platooning formation is largely formed where consolidation and synchronization are enabled, and that the associated fuel and emission savings are sensitive to routing structure, timing flexibility, and operational constraints. This motivates the present study, which brings platooning into the strategic design of courier line-haul systems by jointly optimizing hub locations and inter-hub routing while explicitly valuing carbon benefits.

2.4. Research Gaps of This Study

Based on the above review, several gaps are identified where hub location, service network design, carbon-emission modeling, and truck platooning are considered together. Table 1 summarizes how these gaps are addressed by the present study through the integrated HLPRP with monetized carbon benefits and a solution framework.

Table 1.

Comparison between representative studies and this work.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Problem Settings

We consider the strategic design of a courier line-haul network where consolidation is performed at hubs and line-haul movements are executed by trucks on a road network. The proposed hub location and platoon routing problem (HLPRP) integrates hub location-allocation, service network design, and platoon formation and routing decisions. The following settings and assumptions are adopted:

- (i)

- The system is modeled using two coupled network layers: a physical network that determines which nodes operate as hubs and how non-hub nodes are allocated to hubs; and a service (trip) network that determines which inter-hub services are provided, which feasible corridors they use, and whether platooning is activated on those services.

- (ii)

- OD demand between nodes is deterministic and measured in tons. Considering hub selections and allocations, OD flows are aggregated into hub-to-hub consolidated demands used to design and operate line-haul services.

- (iii)

- Road distances (and baseline emissions) are assumed symmetric between hubs. Therefore, inter-hub decisions are defined on undirected hub pairs, and each hub pair corridor is modeled only once to avoid duplication.

3.2. Integrated HLPRP Formulation

Before presenting the mathematical formulation, the essential abbreviations and notations used throughout the paper are provided in the Abbreviations and notations section.

The integrated problem jointly optimizes hub location-allocation, platoon departure hubs, and service network route selection. The total objective combines physical network costs, service network transportation costs, and monetized carbon benefits from platoon-operated line-haul movements:

The monetized carbon benefit term is used to internalize the value of emission reductions within the objective. The coefficient is interpreted as a scenario-dependent carbon price. If , the model reduces to the cost-only formulation.

Each node must be assigned to one and only one hub. Because single allocation is employed, node cannot be split across multiple hubs:

Exactly hubs must be opened:

Node is allowed to be allocated to node only when node is selected and operated as a hub. If node is not selected as a hub, then no node is allowed to be allocated to . In other words, allocation to a non-hub node is not permitted (Constraint (4)). Similarly, a node can be designated as a platoon departure hub only when it is selected and operated as a hub. If node is not selected as a hub, then it cannot be equipped for platoon formation and coordinated departures and also cannot be used as a platoon departure point in the network design (Constraint (5)).

If an inter-hub service between and is provided, then exactly one route must be selected from the candidate set to operate that service:

A route can be selected for the hub pair only when both and are chosen as hubs. If either or is not chosen as a hub, then no route is allowed to be selected for this pair, and an inter-hub service between these two nodes cannot be established:

For each OD pair , the full demand must be assigned to an ordered hub pair . The variables split and distribute the demand across hub pairs, and the total amount should neither exceed nor fall short of the given demand:

Demand from origin to destination can be assigned to hub and only if is allocated to and allocated to . Note that Constraints (9) and (10) can be rewritten as a single constraint defined for every hub pair . However, such a combined form would require enumerating all hub pairs, thereby increasing the number of constraints. To keep the formulation compact and computationally manageable, we choose to retain the two separate constraints:

All consolidated flow between hubs and must be carried on the selected route set for that hub pair:

Flow can use route only if that route is selected. Here, is chosen to be large enough so it does not restrict feasible flows:

Platoon operation can be activated only when the corresponding service exists. If no service is provided for hub pair , then platooning is not available:

Platoon operation on hub pair is allowed only if both endpoint hubs are platoon-enabled. If either endpoint is not platoon-enabled, then platooning cannot be used for this hub pair:

The platoon flow on a route cannot exceed the total flow on that route:

If platooning is not activated on hub pair , then there should be no flow on that hub pair treated as platoon flow:

Platooning is activated on service from to only when a positive amount of freight is actually carried under platoon operation on that hub pair. Without Constraint (17), the model could activate platooning but assign no flow to the corresponding routes:

The domains of variables are as follows:

The above model is an integrated mixed integer linear programming, the constraint scale of which shows polynomial growth with the cardinalities of the model sets. Specifically, the number of constraints is of order , where denotes the average number of candidate routes per hub pair. The OD coupling and route selection components typically account for the majority of constraints.

4. Variable Neighborhood Search-Based Simulated Annealing

4.1. Initial Solution Construction

According to the decision variables in the integrated HLPRP, a feasible solution is defined by three components: the selected hub set, the single allocation of each node to one hub, and the platoon enabling decision for hubs. Given these three components, the inter-hub services, route selection, and platoon operation decisions can be derived consistently from the consolidated flows between hubs. Therefore, the goal of the initial solution is to generate a feasible and reasonable starting point that reflects the demand structure and the distance structure of the network.

To clarify how an initial solution is built, consider an OD demand from node to node . Once an initial hub set is selected and each node is assigned to one hub, node is assigned to an origin hub and node is assigned to a destination hub . The single allocation of node is represented by a mapping . We define as the set of platoon-enabled hubs. If and with , this OD demand contributes to the consolidated flow on the hub pair . Otherwise, it does not create inter-hub traffic. By summing such contributions over all OD pairs, the consolidated flow on each hub pair can be obtained. If the flow on exceeds the platoon threshold and both endpoint hubs are platoon-enabled, platoon operation on that hub pair becomes available, and the corresponding monetized carbon benefit can be credited in the objective value. The initial solution can be expressed as . Based on the above principles, the procedure for constructing an initial solution is as follows:

Step 1: Select an initial hub set. Compute the total OD volume for each node, including both outgoing and incoming demands. Select the top nodes with the largest amount as the initial hubs.

Step 2: Generate a feasible single allocation. Assign every node to exactly one selected hub. A practical rule is to allocate each node to the nearest hub in the initial hub set. This immediately yields a feasible allocation that satisfies the single allocation requirement.

Step 3: Identify inter-hub flows implied by the allocation. Using the allocation obtained in Step 2, aggregate OD demands into consolidated flows between hub pairs. For each OD pair with positive demand, the origin node contributes its demand to the hub of its origin allocation, and the destination node contributes its demand to the hub of its destination allocation.

Step 4: Enable platoon capability by a greedy improvement rule. Examine each selected hub and temporarily enable its platoon departure capability. Evaluate the objective value after allowing the hub to be platoon-enabled, where the inter-hub route selection and platoon operation decisions are updated according to the consolidated flows. If enabling a hub decreases the objective value, then keep it enabled. Repeat this operation until no further improvement can be obtained by enabling an additional hub.

Step 5: Derive route selection and platoon operation decisions. For each hub pair with positive consolidated flow, select one candidate route from its route set by choosing the route that yields the smallest net line haul cost, where the net cost includes the regular line haul transportation cost and the monetized carbon benefit. This produces a complete initial solution for the HLPRP.

The above construction yields a feasible solution with a clear structure: a hub and spoke physical network, a consistent set of inter-hub services implied by the allocation, and a platoon enabling configuration that is supported by the consolidated flows. It also provides a stable starting point for the subsequent VNS-based SA search.

4.2. Neighborhood Structures

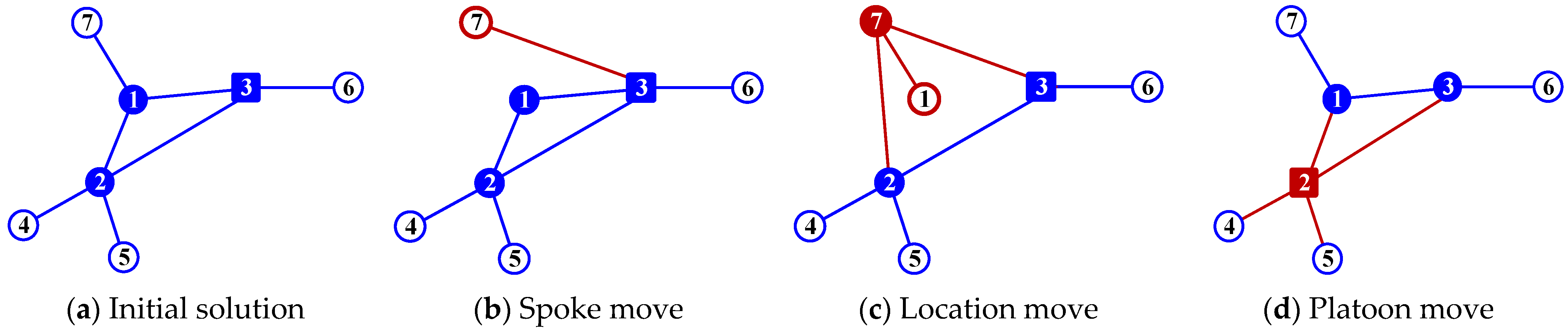

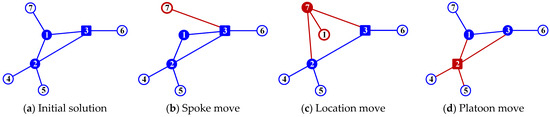

There are four perturbation rules to generate neighborhood solutions depicted in Figure 2, the nodes and links affected by the neighborhood move are highlighted in red for clarity. Each rule modifies one part of the decision structure (allocation, hub set, platoon enabling, or local refinement), and the resulting solution is repaired when necessary to satisfy the single allocation and hub number requirements. Each type of perturbation is chosen according to a pre-given probability .

Figure 2.

Examples of perturbation rules.

Spoke move (SM): Randomly select a node and reassign it from its current hub to another hub in . This change only alters the allocation of node , and keeps the hub set unchanged. The feasibility of single allocation is preserved by construction because each node is always assigned to exactly one hub. In Figure 2, solid circles denote the selected hub nodes, hollow circles denote the non-hub nodes (which are assigned to exactly one hub under the single allocation setting), and squares denote platoon-enabled hubs. Figure 2a gives a simple example of an initial solution. In Figure 2b, node 7 is reassigned from hub 1 to hub 3 (the square hub). Therefore, the spoke link of node 7 changes from 7-1 in (a) to 7-3 in (b). All other hubs and allocations remain the same.

Location move (LM): Select one open hub to close and one non-hub node to open, so Constraint (3) is maintained. Then, repair allocations of nodes previously assigned to by reassigning them to the nearest hub in the new . In Figure 2c, node 1 (hub in (a)) is removed from the hub set and node 7 (a branch node in (a)) becomes a new hub. After this swap, the allocation is repaired: node 1 becomes a branch node and is assigned to the new hub 7, which is shown by the new spoke link 1-7. Other nodes keep feasible allocations to the available hubs.

Platoon move (PM): Select a hub and change its platoon enabling status, that is, enable platoon departure capability if it is currently not enabled, or disable it otherwise. This change determines whether platooning can be applied to inter-hub services that involve hub . In Figure 2d, the platoon-enabled status is shifted from hub 3 (square in (a)) to hub 2 (square in (d)). The hub set and all spoke connections remain the same as in (a). Only the platoon enabling label changes.

Intensification move (IM): Perform a short greedy improvement phase that repeatedly applies the best improving move.

4.3. VNS-Based SA Framework and Acceptance Rule

A variable neighborhood search-based simulated annealing (VNS-based SA) framework is adopted to solve the integrated HLPRP. In the SA search, the fitness function is the same performance measure as the objective value of the mathematical model, which is a direct calculation of the model objective under the solution representation.

For the SA part, the algorithm iteratively generates neighbor solutions using multiple neighborhood structures at each temperature level. The neighborhood index controls the size and type of perturbation. The Markov chain length is denoted as , which is fixed to 60 in all experiments. Starting from the current solution , the algorithm performs a shaking step to obtain a perturbed solution . The fitness values and are computed, and the acceptance rule is used to decide whether replaces the current solution. Let denote the change in fitness. If is non-positive, the candidate is accepted because it improves the objective value. If it is positive, the candidate is accepted with a probability , where is the current temperature. The temperature is updated by a geometric cooling schedule with the cooling rate .

The search stops when the temperature falls below a preset minimum value , or when a maximum number of iterations is reached. The pseudocode of the proposed algorithm, including the input parameters and the acceptance rule, is provided in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Probability based simulated annealing with four probabilistic moves for HLPRP | |

| Input: SA parameters T0, Tmin, β, L; move probabilities p = (p0, p1, p2, p3) | |

| Output: Best solution S* and fitness fit(S*). | |

| 1 | S ← INITIALSOLUTION() |

| 2 | F ← fit(S) |

| 3 | S* ← S, F* ← F |

| 4 | T ← T0 |

| 5 | while T > Tmin do |

| 6 | for ℓ ← 1 to L do |

| 7 | Sample op ∈ {Spoke, Location, Platoon, Intensification} according to p |

| 8 | if op is Spoke then |

| 9 | S′ ← SpokeMove(S) |

| 10 | else if op is Location then |

| 11 | S′ ← LocationMove(S) |

| 12 | else if op is Platoon then |

| 13 | S′ ← PlatoonMove(S) |

| 14 | else |

| 15 | S′ ← LocalSearch(S) |

| 16 | F′ ← fit(S′) |

| 17 | Δ ← F′ − F |

| 18 | if Δ ≤ 0 then |

| 19 | accept ← true |

| 20 | else |

| 21 | accept ← true with probability exp(−Δ/T) |

| 22 | if accept then |

| 23 | S ← S′, F ← F′ |

| 24 | if F < F* then |

| 25 | S* ← S, F* ← F |

| 26 | T ← βT |

| 27 | return (S*, F*) |

The initialization mainly involves hub selection and spoke assignment, followed by constructing inter-hub service decisions over hubs. Therefore, the initialization cost scales with and , while the overall computational burden is driven by repeated solution evaluations during the search.

5. Numerical Experiments and Sensitivity Analysis

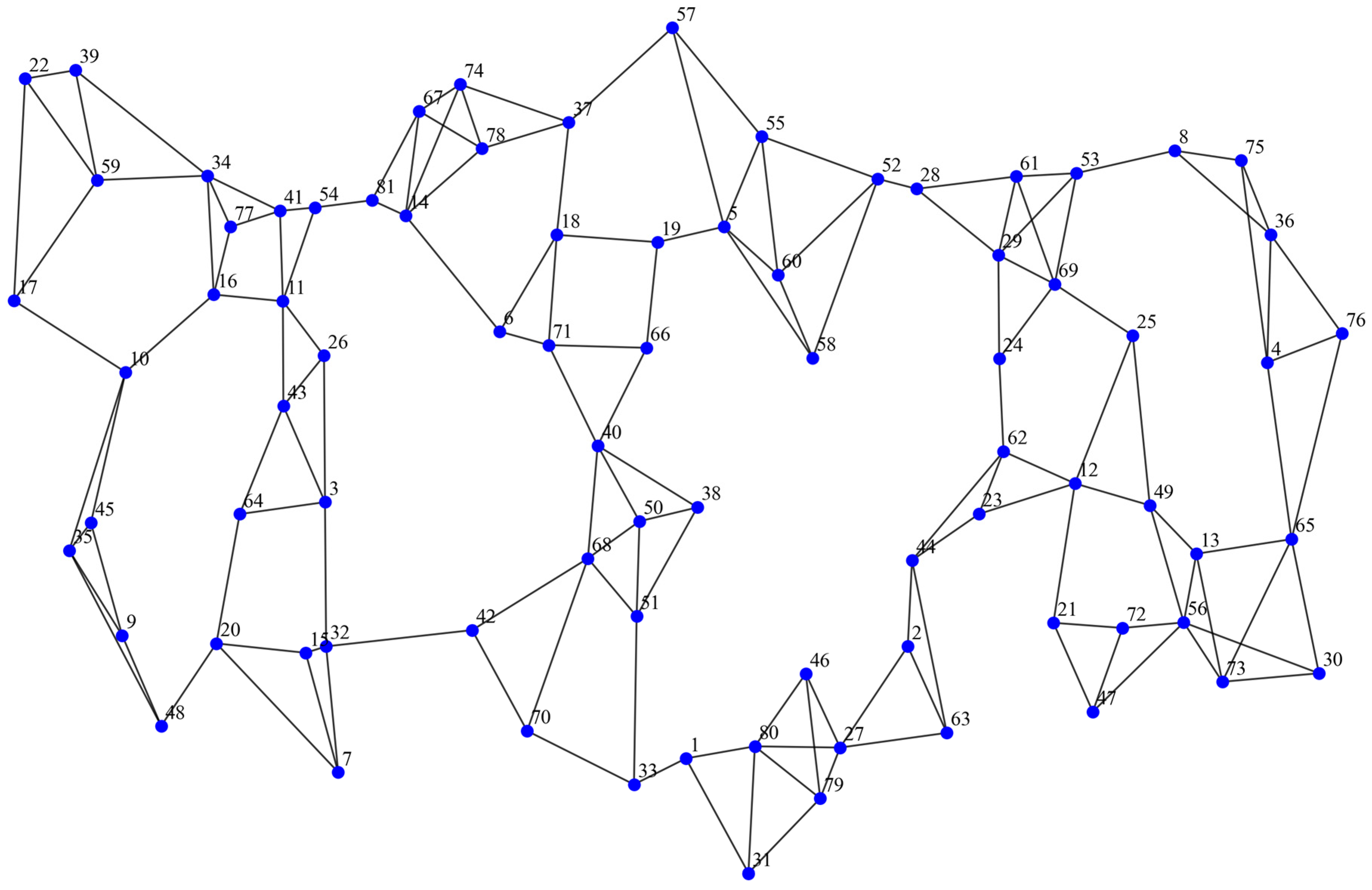

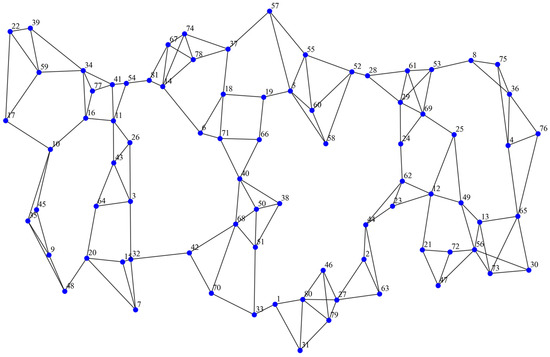

In this section, the proposed solution approach is evaluated on the Turkish CAB data set reported by Beasley [34]. The original Turkish network contains 81 nodes. To examine scalability, we conduct experiments on a sequence of instances with increasing size, starting from a small network with 11 nodes and gradually expanding to the full 81-node network. The geographic locations of the nodes are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of the 81-node Turkish network.

A dedicated sensitivity analysis is then conducted on the probability settings of the four neighborhood moves. By varying the move probabilities while keeping other parameters fixed, their impacts on convergence speed, acceptance behavior, and final objective values are quantified, thereby providing empirical support for the baseline probability configuration used in subsequent experiments.

Finally, an empirical study is presented based on China road network, and the city names and their corresponding node indices (IDs) are provided in Appendix A. A deployable hub and service configuration is derived, including the selected hubs, platoon-capable hubs, and activated inter-hub services. The resulting objective value and the corresponding cost are reported to illustrate how the proposed model and algorithm can support real-world strategic line-haul network design with platoon considerations.

5.1. Numerical Experiments

In the numerical study, the unit transportation cost coefficients are set to for spoke movements and for inter-hub line-haul movements. Platoon operation is controlled by a flow threshold. Specifically, a hub pair is eligible for platooning only when its consolidated flow is no less than tons, and both endpoint hubs are equipped with platoon departure capability. For the carbon component, the baseline emission factor is set to . The emission reduction ratio under platooning is set to , meaning that platooning reduces emissions by 12% relative to the baseline on the corresponding line haul movement. The emission reductions are monetized using a carbon price coefficient , so that the environmental benefit is consistently incorporated into the objective function in monetary terms.

For the VNS-based SA algorithm, the initial temperature is set to . is set to be high enough to yield a high acceptance probability for non-improving moves in the early stage, so that the search can effectively diversify and escape poor local optima at the beginning. In practice, is calibrated via a short pilot sampling so that the initial acceptance rate of uphill moves remains at a reasonable level [35].

The decreasing rate is selected according to classic SA-related studies, where geometric cooling with factors close to 1 has been successfully used [36,37]. The minimum temperature is selected in accordance with the magnitude of the objective values in the tested instances. Since the objective function is reported in the order of ~, should be set at the same order of magnitude so that accepting non-improving moves becomes rare and the search behavior is effectively stabilized at low temperatures. In other words, a too large would still allow frequent uphill acceptance near termination, whereas a too small would prematurely freeze the search. For the neighborhood selection probabilities, we employ four VNS neighborhoods and fix the probability vector to . These values are determined by brief tests on representative small and medium instances and then kept unchanged for all instances. In this case, more productive neighborhoods can be invoked more frequently, while more disruptive neighborhoods are still selected occasionally to reduce the risk of premature convergence. All experiments are conducted in Python 3.12.4 (Spyder 5.5.1) on a desktop PC with an Intel (R) Core (TM) i5 processor and 32 GB RAM under a 64-bit Windows 11 operating system. For stochastic evaluation, each instance is solved with 10 independent runs using a fixed seed set . The pseudo-random number generator is re-seeded at the start of each run to ensure exact reproducibility. The results of numerical experiments are reported in Table 2. The instance size and the resulting network configuration are described in terms of the numbers of nodes, opened hubs, platoon-enabled hubs, activated inter-hub services, and spoke assignment links, which together characterize the physical and service networks. The objective values are reported as Obj (scaled by ), and Table 2 provides the best objective value as well as the mean ± standard deviation over multiple independent runs. The solving time is also reported as mean ± standard deviation. In addition, the last four columns summarize the attempted share (in %) of the four neighborhood moves (SM, LM, PM, and IM), providing a concise view of how the search effort is distributed across move types.

Table 2.

Performance of the proposed VNS-based SA algorithm under different network sizes (11–81 nodes).

As shown in Table 2, enlarging the network induces a consistent increase in the structural scale of both the physical and service layers. The number of activated inter-hub services grows rapidly from 3 to 190, indicating that positive consolidated flows are induced for essentially all unordered hub pairs under the considered demand structure, leading to a fully connected inter-hub service layer. The best objective value increases from to , which is expected as both network size and the induced service structure expand. The corresponding mean objective values show only modest variability across runs. Despite the quadratic growth in the number of inter-hub services, the computational time remains moderate and increases smoothly with instance size, from 0.38 ± 0.02 s for the smallest instance to 23.89 ± 0.43 s for the 81-node case, suggesting that the proposed VNS-based SA framework scales to the full benchmark without deterioration in tractability. The platoon-enabled hub set is observed to become more selective as the network expands (e.g., 8 out of 16 hubs for 61 nodes and 14 out of 20 hubs for 81 nodes), implying that platoon enabling is activated only when the corresponding flow aggregation and benefit potential can offset the additional enabling investment under the flow threshold mechanism. Finally, the share of the four neighborhood moves remains stable across all scales and is consistent with the pre-specified move selection probabilities, thereby supporting the comparability of the subsequent sensitivity analysis on move probabilities.

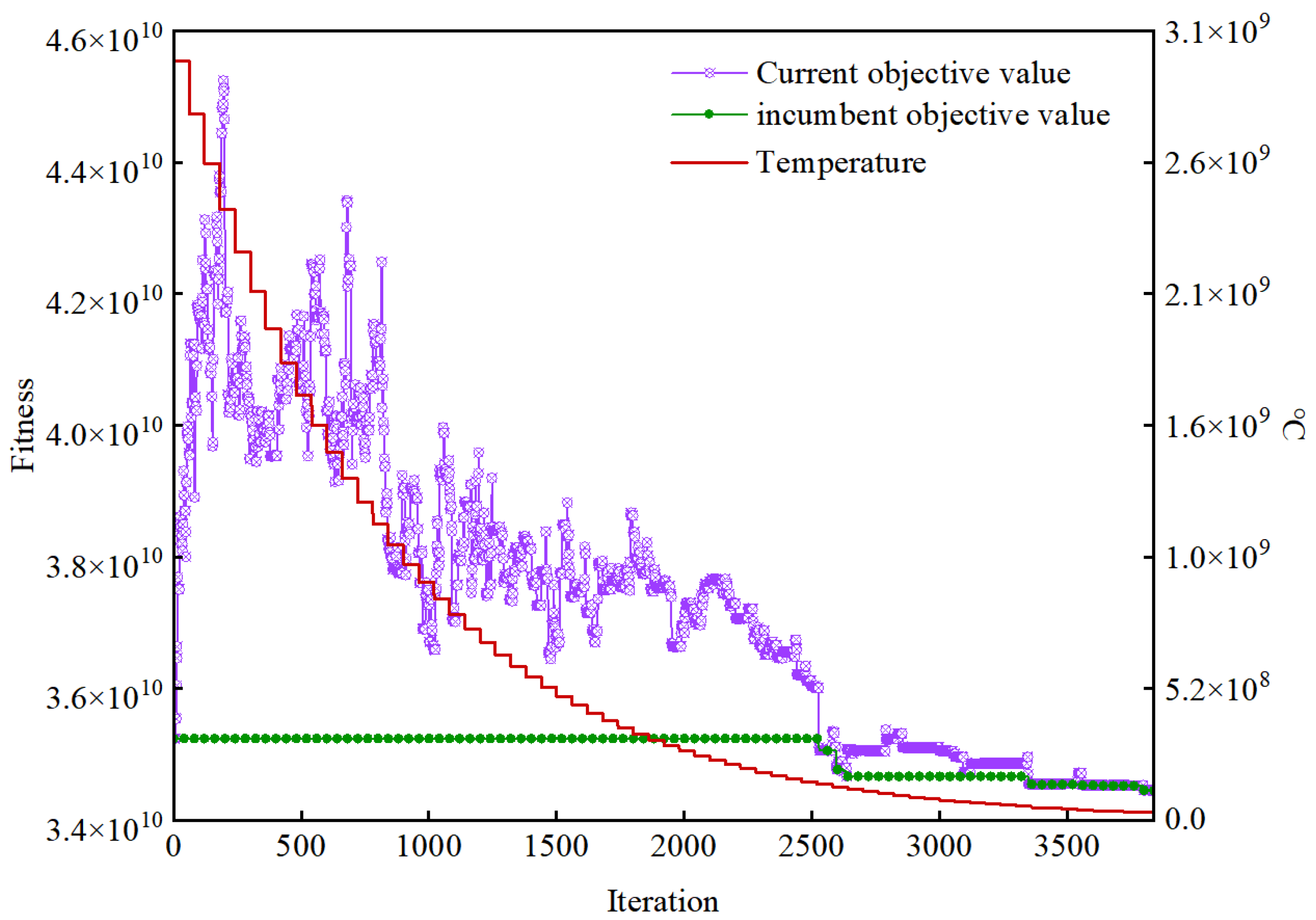

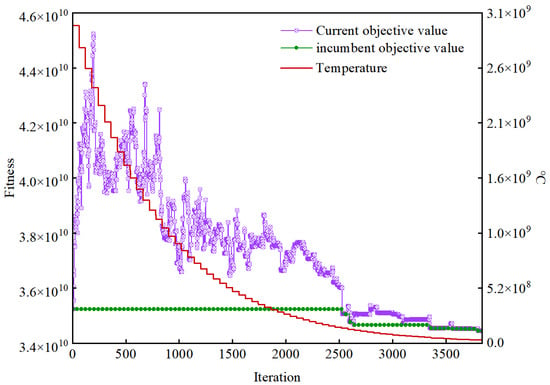

Figure 4 illustrates the convergence behavior for a representative single-seed run. For the SA, the current objective value exhibits substantial fluctuations in the early stage, when the temperature is high and non-improving moves are accepted with relatively large probability, which promotes diversification and facilitates escaping poor local optima. As the temperature decreases under the geometric cooling schedule, the frequency of these oscillations decreases progressively, indicating a gradual transition from exploration to exploitation. In parallel, the incumbent objective value evolves in a stepwise non-increasing manner, suggesting that further improvements become increasingly rare once the search enters a stable region. The eventual stabilization of both the current and incumbent trajectories at low temperatures indicates convergence toward a high-quality solution under the adopted termination criterion.

Figure 4.

Convergence performance of the VNS-based SA algorithm.

In addition, we further assess the effectiveness of (default settings are used unless stated otherwise) the proposed VNS-based SA by benchmarking it against two representative references, including (i) an exact MIP solver baseline using Gurobi 13.0 to provide an exact reference and (ii) a pure SA baseline using the same solution encoding and objective function as the proposed approach, evaluated on eight instances with increasing scales . For fairness, all methods are tested on identical instances under the same stopping criterion, and the same initial solution procedure is used: stochastic results are summarized over multiple independent seeds. It should be noted that Gurobi is run with a time limit of 3600 s per instance, and its incumbent objective value and the final MIPGap are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparative results of VNS-based SA against SA and time-limited Gurobi.

As summarized in Table 3, VNS-based SA consistently improves solution quality over the SA baseline across all tested instances. For example, the relative improvement of VNS-based SA over SA ranges from 0% on the smallest instances to 18.63% on (71,18) and remains 16.26% on (81,20), while the computational time remains within an acceptable range. Regarding the exact solver, Gurobi achieves optimality on the smallest instances (11,3) and (21,5). However, when the instance size increases, starting from (31,8), the corresponding MIP model becomes substantially more difficult for the solver. Within the 3600 s limit, Gurobi terminates with a large remaining MIP gap—60% on (31,8) and 217% on (41,10)—indicating that the time-limited results are not reliable as a quality benchmark for larger instances. Therefore, the Gurobi results for only the small instances are reported, where it provides a meaningful reference. These results indicate that the proposed VNS-based SA offers a favorable balance between solution quality and computational efficiency, especially for medium and large instances where exact MIP solving is computationally expensive.

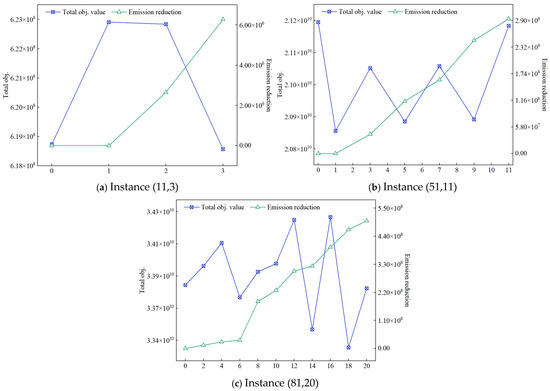

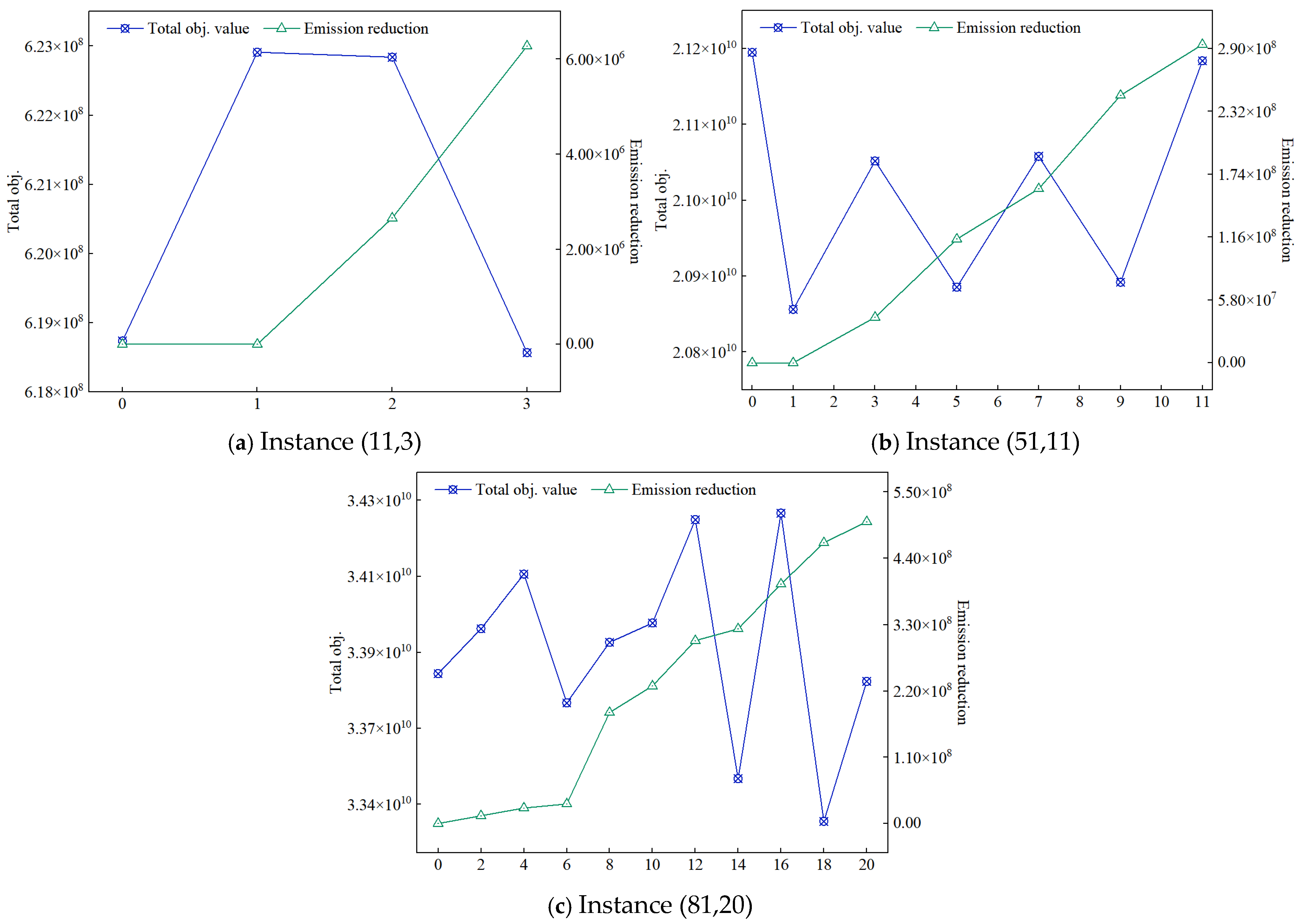

To clarify the managerial and policy implications of platoon deployment, an additional analysis is conducted by varying the number of platoon-enabled hubs while keeping the instance size fixed. It is observed that the emission reduction increases with , whereas the objective does not necessarily improve monotonically, implying diminishing marginal returns and an instance-dependent effective range of . Detailed numerical results and the corresponding trade-off plots are provided in Appendix B.

5.2. Sensitivity Analysis on Platoon Eligibility Threshold

The platoon eligibility threshold is a key mechanism parameter in our model because it directly governs when platooning can be activated on an inter-hub service. To verify that our structural insights are not artifacts of a single threshold setting, we conduct a sensitivity analysis on . Three levels are designed, namely , (baseline), and , and the monetized carbon benefits, emission reductions, number of activated inter-hub services, and platoon-enabled hubs are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of platoon eligibility threshold.

For (11,3), only minor changes are induced when is reduced to . Although the underlying solution may vary, the resulting differences are negligible at this scale and are not distinguishable under the reported numerical precision. When is increased to , the inter-hub service layer and platoon-enabled hubs are reduced from 3 to 2, and lower emission reduction and monetized benefits are obtained. For (51,11), the objective is reduced from 2.09 to 1.87 when the threshold is relaxed, along with increases in inter-hub services from 55 to 68 and platoon hubs from 8 to 11. Under , inter-hub services and platoon hubs are reduced and the objective increases to 2.57. For (81,20), the strongest structural response is observed. When the threshold is relaxed to , the number of activated inter-hub services increases from 190 to 213 and the platoon-enabled hubs increase from 14 to 18, accompanied by higher monetized benefits and a lower objective value (from 3.32 to 3.27 ). When the threshold is tightened to , the activated inter-hub services decrease from 190 to 136, the platoon-enabled hubs decrease from 14 to 9, and the objective value increases to 3.86 .

Overall, relaxing the threshold (from to ) enlarges the set of eligible flows, which tends to increase both the scale of the service and the scope of platooning decisions. For medium and large instances, this leads to more activated inter-hub services and a larger set of platoon-enabled hubs, accompanied by higher emission reductions and monetized carbon benefits, thereby improving the overall objective value. Conversely, tightening the threshold to makes platooning more selective, reducing eligible services and typically shrinking the platoon-enabled hub set, which lowers the monetized environmental gains and results in a higher total objective. These results indicate that the reported structural insights are driven by the threshold mechanism itself rather than by a single parameter setting.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis on Neighborhood Move Probability

Sensitivity analyses are conducted to examine how the probability configuration of the four neighborhood moves affects search behavior and final solution quality. In the proposed VNS-based SA framework, one move is sampled at each iteration from a categorical distribution , corresponding to the spoke move (SM), location move (LM), platoon move (PM), and intensification move (IM). The baseline setting is used across the numerical experiments hereinbefore.

To independently evaluate the impact of each move type, a controlled perturbation scheme is adopted in which only the move selection probabilities are varied, while all remaining model parameters and SA settings are kept unchanged. For each probability configuration, the number of platoon-enabled hubs, the best objective value, and the solving time are determined. In addition, the attempted share of each move is monitored to verify that the realized move usage is consistent with the prescribed probability vector.

The effect of perturbing the neighborhood move selection probabilities on solution structure, objective value, computational time, and realized move usage for three representative instances (11-, 51-, and 81-node networks) is listed in Table 5. Across all probability configurations, the realized move shares remain close to the prescribed selection probabilities, indicating that the sampling mechanism is implemented correctly and that comparisons across configurations are meaningful.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis of neighborhood move selection probabilities.

From a performance perspective, the objective value is slightly sensitive to the probability allocation, in which the largest instance exhibits the clearest differentiation. It is quite obvious that, for the 81-node case, the best objective values are obtained under configurations that maintain a balanced allocation between structural diversification (SM/LM) and platoon-related adjustments (PM), whereas pushing excessive probability toward a single move tends to degrade performance. In particular, configurations that increase the emphasis on location moves (LMs) or platoon moves (PMs) can alter the search trajectory noticeably, leading to different counts of platoon-enabled hubs and measurable changes in the final objective. This behavior is consistent with the fact that LMs and PMs directly reshape consolidated inter-hub flows and therefore affect both service activation and platoon eligibility.

The number of platoon hubs varies with the probability setting, especially in the medium and large instances, confirming that platoon-enabling decisions are influenced by the frequency of PM and by the frequencies of reallocations (SMs) and hub relocations (LMs) allowed to restructure flow aggregation. Meanwhile, the solving time generally increases with network size but also exhibits variation across probability settings for a fixed instance, reflecting differences in the difficulty of the search path induced by different move mixes. Finally, the reported acceptance rates show a systematic pattern, that is, SM tends to have very high acceptance, while LM exhibits lower acceptance in larger instances due to LM inducing larger structural changes that are more frequently rejected at lower temperatures.

Overall, the results support the use of the baseline probability configuration as a robust compromise. It yields competitive objective values while maintaining stable move utilization and consistent convergence behavior.

5.4. Real-World Application

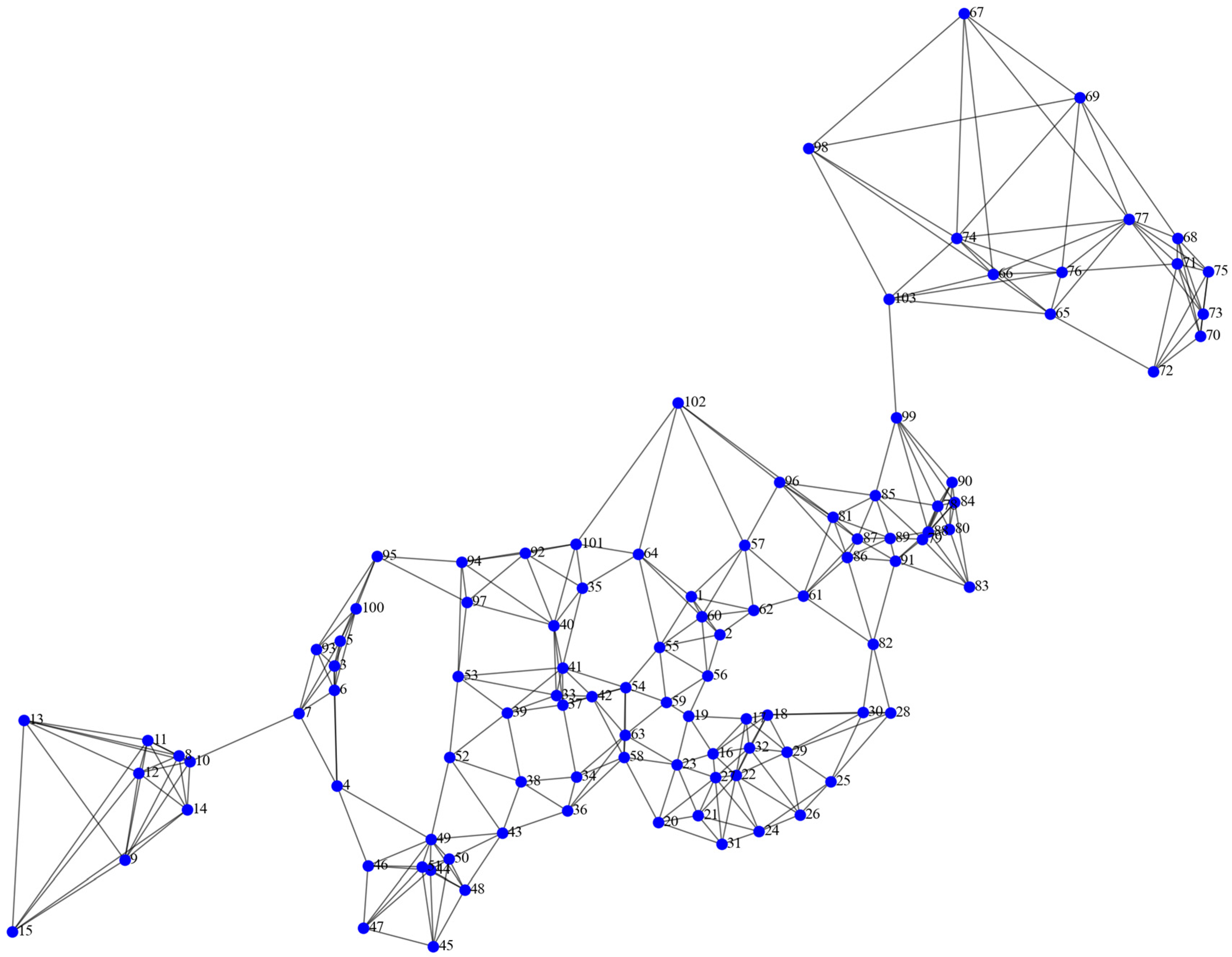

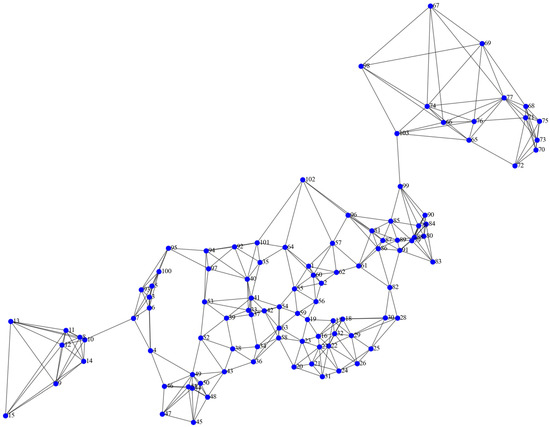

The real-world case study is built on a set of northern China cities, which covers 103 cities across 11 provincial regions, including two municipalities (Beijing and Tianjin) and nine provinces or autonomous regions (Ningxia, Qinghai, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Liaoning, and Inner Mongolia). The topological structure of the network constructed for the Northern China instance is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Topological structure of the Northern China network.

For each city, geographic coordinates are extracted and pairwise distances are approximated by great circle distance (km), which can approximate the distance on a spherical surface accurately [38]. Since detailed cost and freight statistics between cities are not fully available for all nodes, we construct a consistent set of HLPRP inputs based on administrative status and economic importance. Specifically, each node is assigned an economic weight based on whether it is a municipality, a provincial capital, or a major economic or port city. Hub’s fixed opening costs and platoon enabling costs are then scaled with the economic weight to reflect the higher facility and coordination investments at economically dominant nodes. The OD demands are generated by a gravity mechanism so that larger economic nodes tend to exchange larger flows, while long-distance pairs are less likely to generate demand. Detailed information can be found in Appendix A.

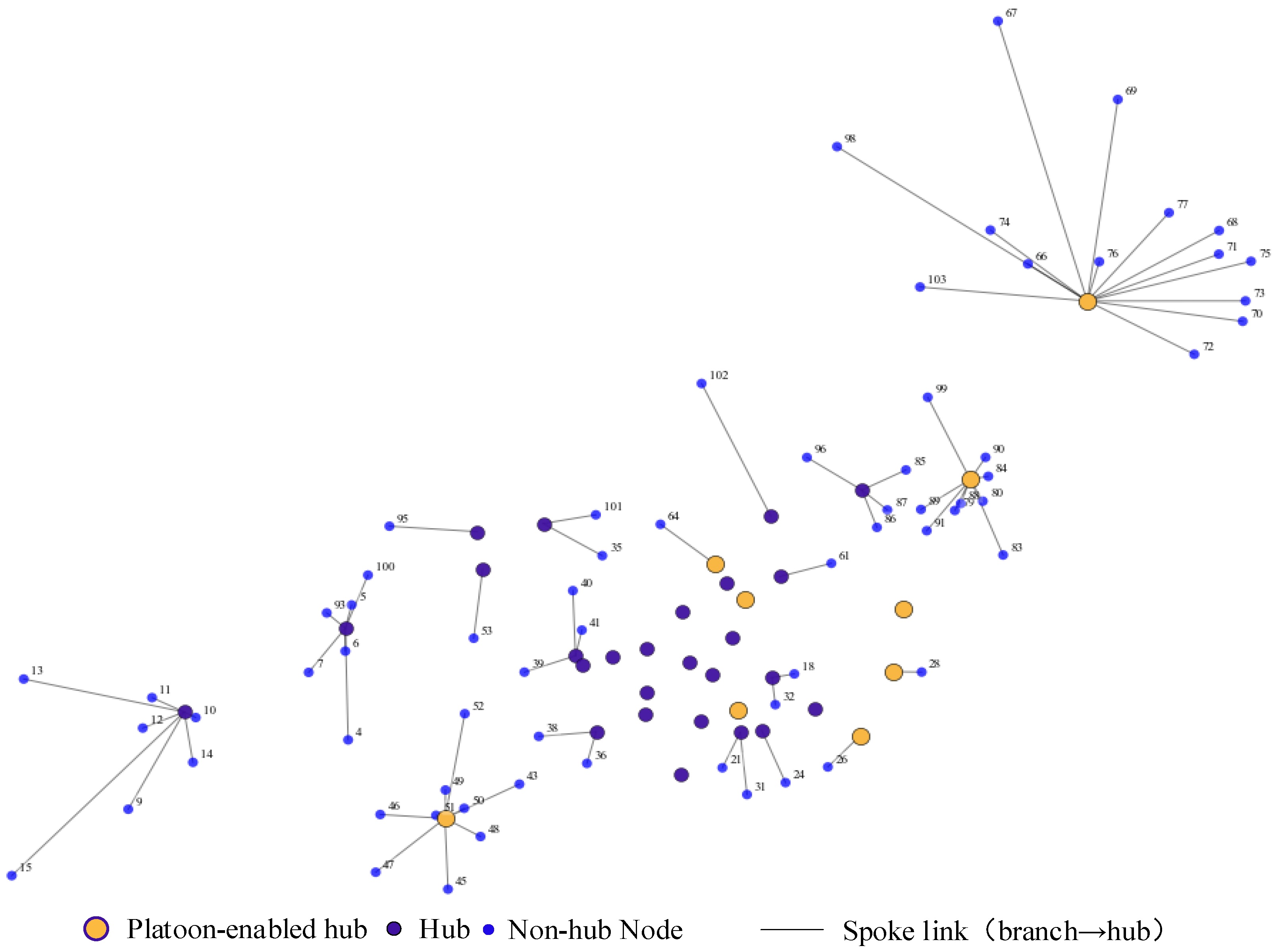

Figure 6 visualizes the hub selection and single-allocation structure produced by the VNS-based SA algorithm for the 103-node North China instance. A total objective value of 37,357,838.81 is attained in the best solution, where 26 hubs are opened and 9 platoon-enabled hub is selected. In the physical network, each non-hub city is connected to exactly one assigned hub, the structure of which is enforced by the single-allocation rule reflected in the solution output. Each node is associated with a unique assigned hub and a corresponding spoke distance. It is quite obvious that shorter spoke distances are predominantly observed in dense regions (e.g., Node 28 (Weihai) → Platoon-enabled hub 30 (Yantai), 69.17 km), whereas longer spokes are mainly induced in sparsely distributed areas (e.g., Node 98 (Hulunbuir) → Platoon-enabled hub 65 (Harbin), 642.93 km).

Figure 6.

Physical network induced by a single allocation.

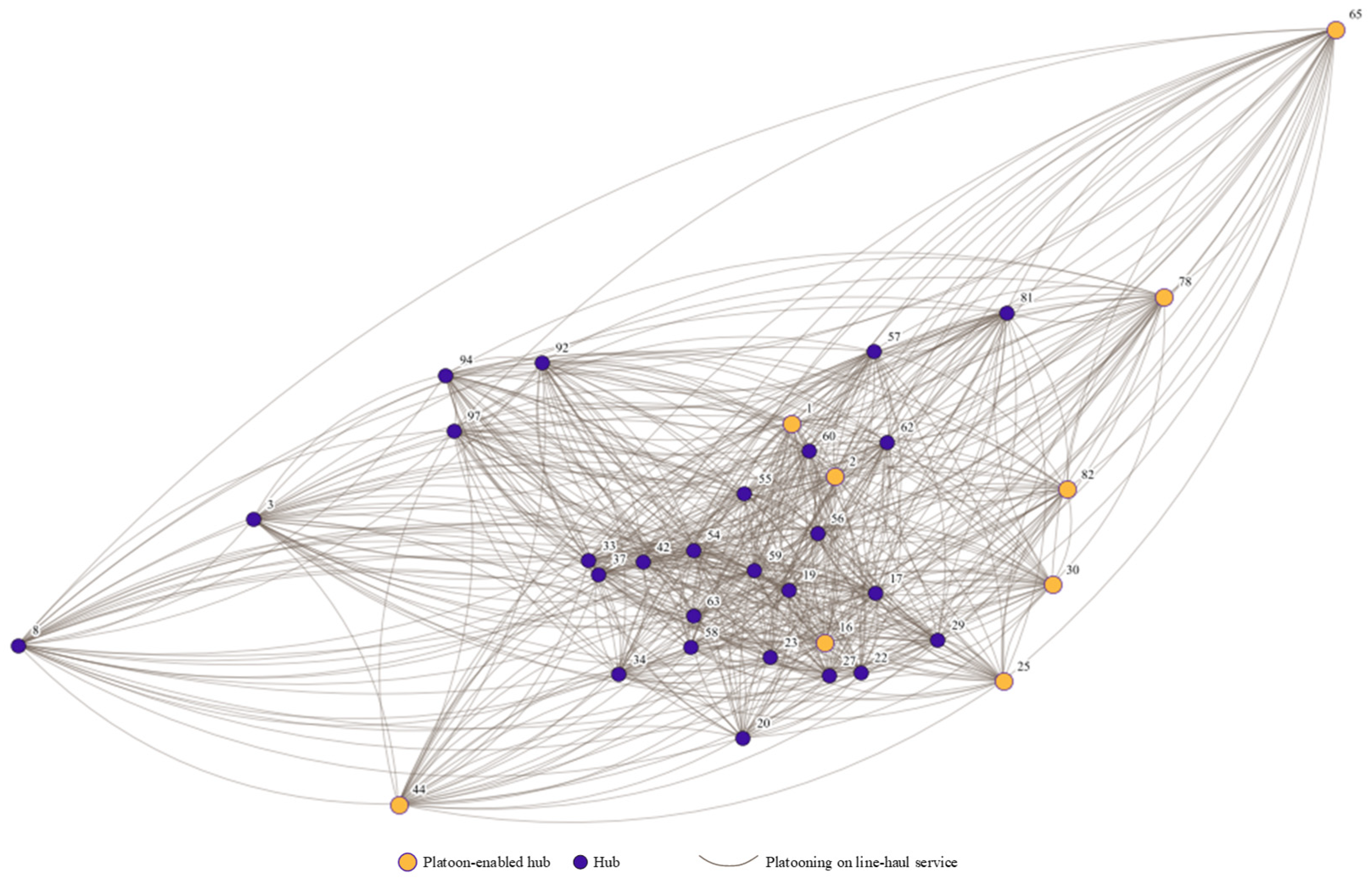

A highly connected and dense service network is depicted in Figure 7. Inter-hub flows are generated by consolidating OD demands over hub pairs: whenever the origin and destination are assigned to different hubs, the corresponding OD demand is aggregated into the consolidated flow of that hub pair. Under these circumstances, 576 inter-hub pairs are activated with positive consolidated flows. From an operational perspective, stronger service corridors are associated with high-volume interregional demand. For example, the hub pair Harbin → Shenyang carries a consolidated flow of 2411.9 tons, indicating a dominant northeast corridor in the solution. The service and physical network confirm that the solution is driven by transportation costs and are further modulated by platoon investment and the resulting carbon benefit. The total cost is dominated by the line-haul cost () and the spoke cost (), while platoon enabling costs and carbon benefits are determined by the nine opened platoon-enabled hubs and the inter-hub services for which platooning is activated. It can be concluded that distance-based assignment is emphasized in the physical network (yielding hub-spoke clustering), whereas a dense service network is induced as OD demands are aggregated across many opened hubs, producing dispersive inter-hub flows.

Figure 7.

Inter-hub service network with platoon-enabled hubs.

It is worth noting that existing hub location and service network models primarily focus on cost-oriented network structure, while platooning studies are often conducted on a given network or fixed routes. Consistent with the platooning literature, the results indicate that environmental gains are realized only when sufficient flow consolidation enables platoon operations. Different from prior studies, these effects are captured within an integrated planning framework where hub locations, service links, and platoon-enabled hubs are decided jointly, and carbon impacts are explicitly reflected through a monetized benefit term, thereby making the trade-offs between cost and emission observable in strategic network planning.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, an integrated hub location and platoon-enabled routing model is formulated for courier line-haul networks with single allocation. The planning operation is organized into two parts, namely the construction of the physical hub-and-spoke network and the design of the inter-hub service network, where platooning is enabled at selected hubs and the resulting carbon benefit is monetized and credited in the objective. To solve the resulting large-scale problem, a VNS-based simulated annealing heuristic is developed to search the physical network decisions efficiently, while the associated service network decisions are generated consistently from the consolidated hub-to-hub flows and the selected corridors. Computational experiments for a realistic, large-scale China example are conducted to examine the effectiveness of the model and the solution approach. The results indicate that the proposed approach produces a high-quality solution within practical runtimes. Sensitivity analyses further show that the number and placement of hubs and platoon-enabled hubs significantly affect both the structure of hub-spoke clusters and the density and strength of inter-hub services, which in turn determine the carbon benefit.

For future research, capacitated and time-dependent extensions should be prioritized. The current work evaluates line-haul operations on a corridor basis and does not explicitly model service schedules, departure sequence, or capacity limits at hubs and on line-haul links. Incorporating hub processing capacity, link capacity, and time-window or timetable constraints would make platoon formation and waiting decisions more realistic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; methodology, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, H.J.; resources, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.J.; supervision, H.J.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hebei Province Natural Science Foundation—the Young Scientific Research Fund Project (Category C), grant number E2025210085.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations and Notations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HLPRP | Hub Location-Platoon Routing Problem |

| LTL | Less-Than-Truckload |

| MIP | Mixed Integer Programming |

| MILP | Mixed Integer Linear Programming |

| NLP | Nonlinear Programming |

| OD | Origin-Destination |

| PM | Platoon Move |

| IM | Intensification Move |

| LM | Location Move |

| SM | Spoke Move |

| SND | Service Network Design |

| VNS | Variable Neighborhood Search |

| SA | Simulated Annealing |

The following notations are used in this manuscript:

| Sets | |

| Set of nodes (candidate hubs and branch offices) | |

| Set of selected hubs | |

| Set of candidate feasible routes (corridors) between the hub pair | |

| Set of OD demand pairs | |

| Set of undirected hub pairs, represented by unordered hub pairs , and each pair is modeled once to avoid duplication under symmetric distances | |

| Parameters | |

| Number of hubs to be located | |

| Demand from origin to destination | |

| Unit cost for shipping flow between node and hub (spoke legs) including handling costs | |

| Fixed cost of establishing a hub | |

| Fixed investment cost of equipping hub with platoon formation and synchronized departures | |

| Generalized cost weight of the candidate inter-hub route | |

| Unit cost coefficient for line-haul transportation per ton-km | |

| Baseline emission factor measured in per ton-km | |

| Emission reduction ratio under platooning, that is, the decrease in emissions per ton-km when the corresponding line-haul movement is operated as a platoon | |

| Monetization coefficient converting emissions to cost | |

| Minimum flow threshold required for a service to be eligible for platoon operation | |

| Big-M constant | |

| Decision variables | |

| Binary variable, equals 1 if node is assigned to hub under the single-allocation rule (i.e., each node is allocated to exactly one selected hub); equals 0 otherwise | |

| Binary variable, equals 1 if node is selected as a hub facility; equals 0 otherwise | |

| Binary variable, equals 1 if hub is designated as a platoon departure hub, that is, platoon formation and synchronized departures are allowed at . By construction, a platoon hub must also be a selected hub; equals 0 otherwise | |

| Binary variable, equals 1 if candidate inter-hub route is selected to provide the line-haul connection for the undirected hub pair ; equals 0 otherwise | |

| Binary variable, equals 1 if an inter-hub line-haul service (i.e., a service arc in the service network) is provided for the undirected hub pair ; equals 0 otherwise | |

| Binary variable, equals 1 if the inter-hub service for is operated under truck platooning; equals 0 otherwise | |

| Continuous variable, total consolidated freight flow (in tons) assigned to route for the undirected hub pair | |

| Continuous variable, portion of the flow (in tons) that is transported under platoon operation on route for the hub pair | |

| Continuous variable, portion of OD demand whose origin is assigned to hub and destination is assigned to hub | |

Appendix A

The complete dataset for the China case study used throughout this paper is provided in Appendix A. All the inputs, including the node list, OD demand data, distance between node pairs, fixed hub and link costs, and enabled costs, are compiled in this appendix to ensure reproducibility.

The full information of this instance has been uploaded to ResearchGate and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21954.44485 (accessed on 13 February 2026).

Appendix B

To provide additional numerical evidence for the practical implications discussed in the main text, a supplementary analysis is reported in this appendix, where the number of platoon-enabled hubs is systematically varied while the instance size is kept fixed. The resulting changes in total logistics cost (total operational cost before carbon credit), monetized carbon benefits, emission reductions, and the objective value are reported in Table A1, together with Total obj. measured against the reference case (no platoon-enabled hubs).

Table A1.

Numerical comparisons of solutions obtained with different platoon-enabled hub settings.

Table A1.

Numerical comparisons of solutions obtained with different platoon-enabled hub settings.

| Instance | Platoon Hubs | Total Logistics Cost | Hub Open Cost | Platoon-Enable Cost | Monetized Carbon Benefits | Emission Reduction | Total Obj. | Δ Total Obj. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (11,3) | 0 | 618,736,720 | 1263 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 618,736,720 | 0 |

| 1 | 622,911,611 | 1152 | 131 | 0 | 0 | 622,911,611 | 4,174,891 | |

| 2 | 622,720,551 | 1279 | 334 | 119,488 | 2,655,295 | 622,840,039 | −71,572 | |

| 3 | 618,285,379 | 1241 | 474 | 282,266 | 6,272,594 | 618,567,645 | −4,272,394 | |

| (51,11) | 0 | 21,233,916,318 | 4473 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21,233,916,318 | 0 |

| 1 | 20,827,313,139 | 4583 | 118 | 0 | 0 | 20,827,313,139 | −406,603,179 | |

| 3 | 21,060,270,740 | 4568 | 570 | 1,889,577 | 41,990,614 | 21,062,160,317 | 234,847,178 | |

| 5 | 20,857,265,623 | 4551 | 935 | 5,137,223 | 114,160,531 | 20,862,402,846 | −199,757,471 | |

| 7 | 21,062,288,854 | 4771 | 1142 | 7,227,472 | 160,610,506 | 21,069,516,326 | 207,113,480 | |

| 9 | 20,859,148,312 | 4480 | 1439 | 11,108,336 | 246,851,915 | 20,870,256,648 | −199,259,678 | |

| 11 | 21,207,475,316 | 4473 | 1851 | 13,221,427 | 293,809,493 | 21,220,696,743 | 350,440,095 | |

| (81,20) | 0 | 33,818,811,995 | 9234 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33,818,811,995 | 0 |

| 2 | 33,948,410,477 | 9760 | 395 | 575,364 | 12,785,873 | 33,948,985,841 | 130,173,846 | |

| 4 | 34,105,054,719 | 10,147 | 710 | 1,153,835 | 25,640,786 | 34,106,208,554 | 157,222,713 | |

| 6 | 33,732,835,410 | 9636 | 1049 | 1,461,121 | 32,469,355 | 33,734,296,531 | −371,912,023 | |

| 8 | 33,901,141,724 | 9687 | 1438 | 8,292,384 | 184,275,206 | 33,909,434,108 | 175,137,577 | |

| 10 | 33,955,185,166 | 9473 | 1857 | 10,278,086 | 228,401,932 | 33,965,463,252 | 56,029,144 | |

| 12 | 34,250,187,827 | 9646 | 2292 | 13,668,259 | 303,739,107 | 34,263,856,086 | 298,392,834 | |

| 14 | 33,500,066,658 | 9495 | 2404 | 14,540,954 | 323,132,311 | 33,514,607,612 | −749,248,474 | |

| 16 | 34,264,988,932 | 10,684 | 2607 | 17,867,222 | 397,049,394 | 34,282,856,154 | 768,248,542 | |

| 18 | 33,369,969,197 | 9906 | 3053 | 20,954,293 | 465,650,958 | 33,390,923,490 | −891,932,664 | |

| 20 | 33,773,757,912 | 9234 | 3311 | 22,528,697 | 500,637,712 | 33,796,286,609 | 405,363,119 |

Note: Total logistics cost refers to the sum of all operational cost components in the objective function before accounting for carbon-related benefits; Δ Total obj. denotes the change in the objective value relative to a reference setting, that is, k = 0 represents no platoon-enabled hubs, where a negative value indicates a reduction (improvement) in the objective.

The results provide clear, quantitative insights for both logistics companies and policymakers. First, platooning does not automatically generate benefits once hubs are enabled; the benefits appear only when the underlying flow and routing conditions allow platoons to actually form. For example, for scenario (11,3), no carbon benefit is realized at , whereas enabling more hubs activates platooning and yields tangible improvements, whereby moving from to leads to an emission reduction of 6,272,594 and an objective improvement of 4,272,394. Second, on larger instances, substantial environmental gains can be achieved, but the best-performing is not necessarily the maximum, which supports actionable deployment guidance. For example, on (81,20), an emission reduction of 465,650,958 is obtained at , and the objective is improved by 891,932,664 relative to . Meanwhile, the case does not yield the best net objective, indicating that the marginal benefit of enabling additional hubs may diminish or be offset by the associated enabling and network configuration effects.

From a logistics company’s perspective, Table A1 can therefore be interpreted as an investment guideline. The platoon-enabling decision should be prioritized on a subset of hubs where platooning is actually triggered and yields strong net savings, rather than being applied indiscriminately. From a policy perspective, the same results quantify the emission reductions achievable by increasing the number of platoon-enabled hubs and can directly support incentive/subsidy design under budget constraints since the incremental environmental benefit associated with higher is explicitly observed in the reported emission reduction and carbon benefit values.

Figure A1 illustrates how the total objective value and the emission reduction vary with the number of platoon-enabled hubs for three representative instances. A clear monotonic increase in emission reduction is observed as increases, indicating that enabling platooning at more hubs expands the set of hub pairs where platoon operations can be activated and thus enhances the environmental benefit. Meanwhile, the objective does not necessarily decrease monotonically with . This is because the objective is influenced by both the additional platoon-enabling cost and the extent to which emission reductions can be realized under the flow and routing patterns.

For the small instance (11,3), as shown in Figure A1a, no emission reduction is realized at , whereas a positive emission reduction emerges once , which suggests a threshold effect where platooning is not triggered until a sufficient number of hubs is enabled. For instances (51,11) and (81,20) in Figure A1b,c, substantial emission reductions are achieved for larger , but the best objective is attained at an intermediate , implying diminishing marginal returns and possible offsetting effects from additional enabling costs and network reconfiguration. As a result, an effective range of is indicated, where most of the emission reduction is captured while the objective remains favorable.

Figure A1.

Effect of platoon-enabled hubs on objective and emission reduction.

Figure A1.

Effect of platoon-enabled hubs on objective and emission reduction.

References

- Shang, P.; Yang, L.; Yao, Y.; Tong, L.; Yang, S.; Mi, X. Integrated optimization model for hierarchical service network design and passenger assignment in an urban rail transit network: A Lagrangian duality reformulation and an iterative layered optimization framework based on forward-passing and backpropagation. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 144, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilegan, I.C.; Crainic, T.G.; Wang, Y. Scheduled service network design with revenue management considerations and an intermodal barge transportation illustration. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 300, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Jing, E.; Xu, J.; Chen, C. The accumulation cost of relaxed fixed time accumulation mode. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 16, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleplanque, S.; Hosteins, P.; Pellegrini, P.; Rodriguez, J. Train management in freight shunting yards: Formalisation and literature review. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 16, 1286–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.F. Hub Location and the p-Hub Median Problem. Oper. Res. 1996, 44, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbi, E.-G.; Todosijević, R. The robust uncapacitated multiple allocation p-hub median problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 110, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarinasab, N. Exact algorithms for the robust uncapacitated multiple allocation p-hub median problem. Optim. Lett. 2022, 16, 1745–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wandelt, S.; Sun, X. Stratified p-Hub Median and Hub Location Problems: Models and Solution Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 11452–11470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, O.; Mandowsky, R.R. Location-allocation on congested networks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1986, 26, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cao, B.; Li, R. Multi-objective Pick-up Point Location Optimization Based on a Modified Genetic Algorithm. In Communications in Computer and Information Science; Pan, L., Liang, J., Qu, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 1159, pp. 751–760. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.; Jia, T.; Du, R.; Lei, D. A Location-Allocation Problem of Emergency Facilities Considering Multi-Resources Under Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control (ICNSC), Hangzhou, China, 18–20 October 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi, A.; Burdett, R.L. An integrated location and routing approach for transporting hazardous materials in a bi-modal transportation network. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 127, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, V.; Yıldız, B.; Farham, M.S. Hub Network Design Problem with Capacity, Congestion, and Stochastic Demand Considerations. Transp. Sci. 2023, 57, 1276–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzzocrea, A.; Gallo, C.; Fornari, G.; Gatto, V. Optimal Location of Hubs over Networks with Demand Uncertainty: A Fundamental Mathematical Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), 30 June–5 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, W.B. A Local Improvement Heuristic for the Design of Less-than-Truckload Motor Carrier Networks. Transp. Sci. 1986, 20, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrah, A.I.; Johnson, E.; Neubert, L.C. Large-Scale, Less-than-Truckload Service Network Design. Oper. Res. 2009, 57, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crainic, T.G. Multi-Layer Network Design for Consolidation-Based Transportation Planning. In Combinatorial Optimization and Applications: A Tribute to Bernard Gendron; Crainic, T.G., Gendreau, M., Frangioni, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 179–205. [Google Scholar]

- Crainic, T.G.; Hewitt, M.; Toulouse, M.; Vu, D.M. Scheduled service network design with resource acquisition and management. EURO J. Transp. Logist. 2018, 7, 277–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, A.K.; Ghafoori, S.; Mahjoob, M.; Fazeli, S.R.; Mirmozaffari, M. A Bi-objective mathematical model for resource constrained project scheduling problem: Formulation and metaheuristics. Soft Comput. 2025, 29, 5683–5706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, M. The Flexible Scheduled Service Network Design Problem. Transp. Sci. 2022, 56, 1000–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, M.; Lehuédé, F. New formulations for the Scheduled Service Network Design Problem. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2023, 172, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsfeld, T.; Hamdan, S.; Jouini, O.; Gast, J. On the optimization of green multimodal transportation: A case study of the West German canal system. Ann. Oper. Res. 2025, 351, 667–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, E.; Burgholzer, W.; Hrušovský, M.; Arıkan, E.; Jammernegg, W.; Woensel, T.V. A green intermodal service network design problem with travel time uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2016, 93, 789–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, N.; Huang, B. Green road–rail intermodal routing problem with improved pickup and delivery services integrating truck departure time planning under uncertainty: An interactive fuzzy programming approach. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 1459–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Gvozdjak, A.; Winkenbach, M. The Service Network Fleet Transition Problem. Transp. Econ. Manag. 2025, 3, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, J.J.; Cafiero, G.; Iuso, G. Aerodynamic drag reduction by means of platooning configurations of light commercial vehicles: A flow field analysis. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2021, 90, 108823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, M.; Shahabi, M.; Yin, Y.; Masoud, N. Itinerary planning for cooperative truck platooning. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2021, 153, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Eksioglu, B.; Schmid, M.J.; Huynh, N.; Comert, G. Optimizing Energy Savings for a Fleet of Commercial Autonomous Trucks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 7570–7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Chung, B.D. Optimizing vehicle route, schedule, and platoon formation considering time-dependent traffic congestion. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 192, 110205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.L.; Lin, Y.-T. Concurrent optimization of routing and platooning decisions for autonomous truck fleets. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2025, 30, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yan, X.; Yin, Y. Truck routing and platooning optimization considering drivers’ mandatory breaks. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 143, 103809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Sun, X.; Luo, Q. Dedicated Lane Planning for Autonomous Truck Fleets under Hours of Service Regulations. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), 2–5 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 2890–2895. [Google Scholar]

- Liatsos, V.; Golias, M.; Mishra, S.; Hourdos, J. The Capacitated Hybrid Truck Platooning Network Problem. Available at SSRN 4248701. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4248701 (accessed on 13 February 2026).

- Beasley, J. OR-library: Hub Location. 1990. Available online: https://people.brunel.ac.uk/~mastjjb/jeb/info.html (accessed on 13 February 2026).

- Ben-Ameur, W. Computing the Initial Temperature of Simulated Annealing. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2004, 29, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.L.; Kuruoglu, E.E.; Chan, W.K. Neural Network Structure Optimization by Simulated Annealing. Entropy 2022, 24, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ma, L.; Jia, X.; Yan, D.M.; Huang, T. GraphReg: Dynamical Point Cloud Registration With Geometry-Aware Graph Signal Processing. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 7449–7464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Yi, H. A rapid globe-wide shortest route planning algorithm based on two-layer oceanic shortcut network considering great circle distance. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 287, 115761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.