Abstract

A fuzzy extractor is a foundational cryptographic component that enables the extraction of reproducible and uniformly random strings from sources with inherent noise, such as biometric traits. Reusable fuzzy extractor guarantees the security of multiple extractions from the same noisy source. In addition, although isogeny-based cryptography has become an important branch in post-quantum cryptography, the study of fuzzy extractors based on isogeny assumptions is still in its early stages and holds much room for improvement. In this paper, we give two reusable fuzzy extractor schemes derived from isogeny-based assumptions: one is based on the linear hidden shift assumption over group actions, while the other is built upon the group-action decisional Diffie–Hellman assumption within the isogeny framework. Both proposed constructions achieve post-quantum security and are capable of correcting a linear proportion of errors. They rely solely on fundamental cryptographic primitives, which ensure simplicity and efficiency. Additionally, the second construction is based on restricted effective group action, which is weaker than the effective group action used in the first construction, thereby offering greater practical applicability.

1. Introduction

In cryptography, many cryptographic primitives, whether in symmetric or asymmetric cryptography, rely on keys that are uniformly random and exactly reproducible to ensure security. Nonetheless, generating such keys is a challenging task. Additionally, despite the fact that numerous noisy sources are available, they are usually unsuitable for direct use due to the noise. Since we aim to derive the same secret key in each generation phase, we ideally expect a symmetric process. However, due to the presence of noise, the reconstruction must handle an inherent asymmetry in the input data, ultimately achieving a goal that appears symmetric in effect. In view of this situation, the term of fuzzy extractor (FE) was initially articulated by Dodis et al. [1] in 2004, which offers a solution to the problem of how to reliably generate and accurately reproduce a uniformly random cryptographic key from noisy sources, such as biometric features [2,3] (e.g., fingerprints and iris scans), physical unclonable functions (PUFS) [4], and quantum information [5].

1.1. Fuzzy Extractor and Reusable Fuzzy Extractor

1.1.1. Fuzzy Extractor

The core of an FE consists of two procedures. One is the generation function Gen(), which receives a reading of the noisy source and produces a string R along with a public help string P; the other is the reproduction function Rep(, P), which takes a new reading and P as input. The security of the FE ensures that if has sufficient entropy, the output string R remains uniformly random from the adversary’s perspective, even if the public help string P is accessible to the adversary. Moreover, as long as , Rep(, P) will output R with overwhelming probability. Then, its correctness is guaranteed.

1.1.2. Reusable Fuzzy Extractor

Nevertheless, the original FE can merely guarantee the security of a single extraction. Repeated extraction of the same noisy source will compromise security. Hence, Boyen [6] put forward the idea of reusable fuzzy extractor (RFE), which can overcome the aforementioned drawbacks and significantly enhance security. Specifically, RFE ensures such security by invoking fuzzy extractor’s generation algorithm Gen() to generate multiple pairs of for different readings from the same noisy source; even if any other multiple pairs of and are exposed to the adversary, still remains pseudo-random from the perspective of the adversary.

In 2016, Canetti et al. [7] introduced an RFE designed for low-entropy distributions, which is based on digital lockers and capable of handling binary strings with Hamming noise. Nonetheless, their construction can only withstand a sublinear proportion of errors and relies on a non-standard assumption.

In 2018, Wen et al. [8] presented the first strongly RFE from the DDH assumption. Later, they [9] constructed another RFE built upon the LWE assumption, which is capable of withstanding a linear proportion of errors. Subsequently, they first formalized the notion of a robustly reusable fuzzy extractor (RRFE) and constructed the first RRFE under the DDH assumption and DLIN assumption over pairing groups [10]. In 2019, they [11] proposed another two RRFEs from LWE and DDH in groups without pairings, respectively.

In 2020, Li et al. [12] presented another RFE based on the LPN assumption. Their construction serves as a post-quantum secure RFE and is more efficient than previous work.

Recently, Zhou et al. proposed the first RRFE [13] and the first RFE [14] from isogeny, both of which rely on the weak pseudo-randomness of CSI-FiSh [15]. Their constructions also support the linear fraction of errors.

1.2. Isogeny-Based Cryptography and Isogeny-Based Assumptions

Advances in quantum computing have greatly promoted the rise of post-quantum cryptography [16,17]. Lattice-based hard assumptions [18,19] are a promising class of quantum-resistant problems, and lattice-based cryptographic research [20] dominates a significant portion of post-quantum cryptography. This makes post-quantum cryptography lack sufficient diversity [13,21]. Isogeny-based cryptography represents another viable non-lattice-based alternative for post-quantum secure cryptosystems [22,23]. One of the most famous protocols based on isogeny is Supersingular Isogeny Diffie–Hellman (SIDH), proposed by Jao and De Feo [24]. However, SIDH is vulnerable to certain quantum attacks [25,26], and its efficiency and security continue to be areas of active research [27]. In 2018, Castryck et al. [28] introduced Commutative Supersingular Isogeny Diffie–Hellman (CSIDH), which simplifies the SIDH protocol and provides a more efficient key exchange mechanism. Building on the CSIDH protocol, CSI-FiSh was proposed as a signature scheme by Beullens et al. [15] in 2019. Later, Alamati et al. [21] established a novel framework built on group actions, allowing for the straightforward usage of various isogeny-based assumptions.

1.2.1. Linear Hidden Shift Assumption

The linear hidden offset (LHS) problem over group actions was first proposed by Alamati et al. in [21], where they formally defined the LHS assumption and analyzed its security. They imply that the LHS assumption is secure in (restricted) effective group action (e.g., CSIDH and CSI-Fish, which are based on supersingular elliptic curves). In addition, they showed that the LHS assumption enables the realization of many cryptographic applications, including symmetric KDM-CPA secure encryption, trapdoor functions, and designated-verifier non-interactive zero-knowledge (NIZK) proofs. Later, Alamati et al. [29] constructed the new trapdoor claw-free functions (TCFS) based on the LHS assumption, which is the first post-quantum secure candidate that operates independently of lattice-related problems. Recently, Alamati et al. [30] designed another two cryptographic primitives with hinting properties from the LHS assumption, including hinting pseudo-random generators (PRGS) and hinting weak pseudo-random functions (WPRFS).

1.2.2. Group Action Decisional Diffie–Hellman Assumption

Similar to the DDH assumption, the GA-DDH assumption is the corresponding hard problem over isogeny-based group actions, which makes its first formal appearance in Stolbunov’s PhD thesis [31] and has attracted widespread research interest in recent years. In 2020, Castryck et al. [32] proposed an efficient attack to break the GA-DDH assumption for all supersingular elliptic curves over with . However, this attack does not extend to the case where , which is precisely the setting used in CSIDH. Hence, it is generally accepted that the GA-DDH assumption holds for CSIDH [28,33]. So far, many cryptographic primitives based on it have emerged, including verifiable random functions (VRF) [34], oblivious pseudo-random functions (OPRF) [35], key encapsulation mechanisms (KEM) [36], etc.

From our perspective, the application of the LHS assumption or GA-DDH assumption in constructing post-quantum secure cryptographic schemes in the isogeny setting exhibits considerable potential and academic merits. In addition, as far as we know, no reusable fuzzy extractor built upon LHS or GA-DDH assumptions has been constructed. Inspired by the above process, an obvious question comes to mind:

Is it feasible to construct an RFE utilizing either the LHS assumption or the GA-DDH assumption?

1.3. Our Contributions

In this work, we provide a confirmed answer to the aforementioned question. The principal contributions of our work are as follows:

- –

- First, we extend the assumption to the assumption via a hybrid argument. Similar to [13], we redefine the reusable fuzzy extractor and introduce an extra initialization algorithm to make it more adaptable to isogeny-based assumptions.

- –

- We give two constructions of RFE from isogeny-based assumptions. Our first construction is the first reusable fuzzy extractor based on the LHS assumption over isogeny-based group actions. Our second construction is the first reusable fuzzy extractor built upon the GA-DDH assumption. Furthermore, we instantiate both constructions based on specific instances of the underlying building blocks.

- –

- Both of our constructions are straightforward and resilient to the linear proportion of errors. In addition, compared with some previous works on reusable fuzzy extractor, our constructions impose no additional requirements (i.e., homomorphism or key-offset security) on the building blocks.

In Table 1, we present a comparison between our constructions and existing reusable fuzzy extractor schemes.

Table 1.

Comparison with some existing reusable fuzzy extractor constructions. “*” is used to distinguish different works with the same abbreviation. “weak” means that any PPT adversary cannot distinguish from uniform strings when given the . “strong” means that any PPT adversary cannot distinguish from uniform strings, even when given the and . “linear” and “sublinear” represent the ability to correct the linear fraction of errors and sublinear fraction of errors, respectively. “IT” denotes Information-theoretic. “H-KS-Free” represents whether reusability does not rely on the homomorphism or key-shift security of the building blocks. “Src. Entropy” denotes the entropy requirement of the fuzzy source. “Comp.Cost” refers to the computational cost of RFE.Gen and RFE.Rep, primarily involving modular exponentiations and group actions (exp, ★). Here, (where is the bit-length of the input and is the order of , as defined in [10]), and l and n are dimensions of the sampled matrix in Scheme 1. “PQ-Res.” indicates post-quantum resistance.

1.4. Challenges and Our Approaches

As we all know, the reusability of many mainstream RFEs relies heavily on the homomorphic property of the underlying cryptographic primitives or the hardness assumptions that have properties similar to key-shift security [8,9,12,14]. Nevertheless, in the context of isogeny, either the set has no operations (as discussed in [13]), or the same operations are not defined in the same domain (e.g., the “+” in the LHS assumption, , “+” on the left is over , and the right is in group ), which makes it difficult to construct reusable fuzzy extractors or fuzzy extractors with stronger security (i.e., robustly reusable fuzzy extractors) from isogeny by conventional means.

To facilitate the use of isogeny assumptions and minimize the requirements on the underlying building blocks, we adopt the approach proposed in [13] and redefine reusable fuzzy extractor. Our modification introduces only an initialization algorithm while preserving the core structure of the traditional RFE. In our construction, the overhead of this initialization algorithm is minimal, as each user invokes it only once, requiring just a single additional execution of the secure sketch generation procedure .

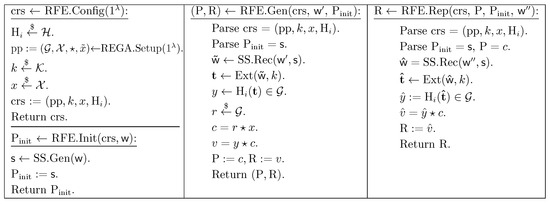

1.4.1. Construction 1: RFE from LHS Assumption

For the first construction, we just utilize a secure sketch, universal hash functions, and an effective group action (EGA) as the key components. In RFE.Config, we incorporate the uniformly random selected hash function along with certain public parameters of the EGA into crs (public and unmodifiable). During the phase of RFE.Init, will produce a , which is stored in the public help string and enables the recovery of in subsequent algorithms. In the RFE.Gen, we first use the sketch to recover as long as the new reading satisfies . Later, will take as input. The generated () will serve as a crucial component of the LHS assumption. Subsequently, we uniformly and randomly sample from and from the set . The EGA and its regularity property guarantee the efficiency of this sampling process. Next, and are put into the public help string P. Under the LHS hypothesis, cannot be distinguished from uniformly random elements in , which is crucial for ensuring reusability. Similar to RFE.Gen, by relying on the correctness of the security sketch and some public parameters, the RFE.Rep algorithm can always regenerate R.

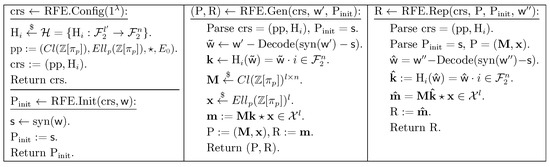

1.4.2. Construction 2: RFE from GA-DDH Assumption

Our second construction follows the same framework as construction 1, making the overall process somewhat similar. However, there are notable differences in the details. First, by leveraging restricted effective group action (REGA, where the GA-DDH assumption is conjectured to hold), construction 2 achieves greater practicality compared to construction 1 (EGA is more powerful than REGA). Furthermore, in our specific construction, we employ a secure sketch, an average-case strong extractor, and a family of universal hash functions. The combination of the latter two primitives, along with the special leftover hash lemma, is the key to our reusability. The detailed information is presented in Section 3.3.

2. Preliminaries

This section is organized as follows. We first introduce the notational conventions used throughout the paper, followed by the definitions of cryptographic primitives and security notions that form the basis of our constructions and security proofs.

2.1. Basic Notation

In our notation, normal, bold, and capital bold letters, like x, , and , are used to represent an element, column vector, and matrix, respectively. Let be the security parameter. For a column vector x, let denote the i-th element of x. Given a matrix , let denote the transpose of . For a matrix and a matrix , we use [, ] to denote the matrix . Let denote the set . The interval refers to the set . Let indicate that x is drawn from the distribution X. For two random variables, X and Y, signifies that these two random variables are statistically (computationally) indistinguishable, with a maximum distinguishing advantage of , if ; the notation can be simplified as . For a set , we write to indicate that x is selected uniformly from . refers to the size of the set. PPT stands for probabilistic polynomial-time. . Our security proof follows a game-based approach. Here, G⇒ 1 signifies that the outcome of game G is 1.

Considering a cryptographic primitive XX and its corresponding security requirement YY, we denote by that the security experiment returns 1 after the interaction with the adversary . The term denotes adversary ’s advantage within the context of this security experiment, that is, .

2.2. Metric Spaces

Definition 1

(Metric spaces [1]). A metric space consists of a set , along with a distance function which defines the distance between its elements (e.g., the Hamming distance, which denotes the number of positions at which two strings of equal length differ).

2.3. Min-Entropy and Statistical Distance

Definition 2

(Min-entropy [1]). Let X be a discrete random variable; the min-entropy of X is defined as

Definition 3

(Average min-entropy [1]). Considering two discrete random variables X and Z, the average min-entropy of X given Z is defined as

Definition 4

(Statistical distance [1]). Considering X, Y be two random variables defined over a set , the statistical distance of X and Y is given by

2.4. Universal Hashing

Definition 5

(Universal hash functions [1]). A family of hash functions is called universal if for all/any distinct inputs , we have

Lemma 1

(Generalized leftover hash lemma [1]). If is a family of universal hash functions, then for any random variable W taking values in and any random variable Z, we have

where I and U follow uniform distributions over the sets and .

Here, we introduce the following special case of a leftover hash lemma [21,30], with its proof provided in [38].

Lemma 2.

Let be an abelian group under addition with the order , and let such that . If , , and , it is evident that , where .

2.5. Secure Sketch and Average-Case Strong Extractor

Definition 6

(Secure sketch [1]). An -secure sketch consists of two algorithms with the following specifications.

- –

- takes as input and outputs a sketch ;

- –

- takes and a sketch as input and outputs .

It also satisfies the following properties:

- –

- Correctness: If , then

- –

- Security: For any distribution W over ,

An instantiation of SS was introduced in [1], which achieves information-theoretic security. For completeness, we restate it in Section 4.1.

Definition 7

(Average-case strong extractor [1]). A function is an average-case -strong extractor with seed if for any variable W over and variable Y such that , we have where K and U are uniformly distributed over and , respectively.

2.6. Group Action, LHS Assumption, and GA-DDH Assumption

For the sake of clarity and abstraction, prior research has resorted to modeling certain isogeny-based constructions through group actions [21,29,30]. In the following, we provide a brief overview of cryptographic group actions and isogeny assumptions.

Definition 8

(Group action [21]). Let be a group that acts on , with a mapping from to satisfying the following conditions:

- 1.

- Identity: For the identity element e of , for all ;

- 2.

- Compatibility: For all and , we have .

According to [30], it is reasonable to use the symbol + to represent the binary operation in within this paper. Here, we concentrate on group actions that are both abelian and regular , as considered in prior works [13,30]. More precisely, we have the following:

- 1.

- Abelian: The group is abelian;

- 2.

- Transitive: For any , there is a group element satisfying ;

- 3.

- Free: A group element is the identity element if for some .

Remark 1.

For a regular group action, the map creates a bijection between and for any .

Definition 9

(Effective group action [21,30]). An effective group action is a group action that satisfies some properties described below:

- 1.

- is a finite group, and efficient algorithms are available for membership testing, equality testing, random sampling, group operation, and inversion;

- 2.

- is a finite set, and known algorithms efficiently handle membership testing and compute the unique bit-string representation for every element in ;

- 3.

- There is a distinguished element , known as the origin, whose bit-string representation is available;

- 4.

- For any and , efficient algorithms can compute .

As stated in [13], we can obtain a regular and abelian EGA from CSI-FiSh [15].

Definition 10

(Linear hidden shift assumption [21,29,30]). For an , and let such that . The assumption is -hard if for any adversary and any , it holds that,

where , , and .

By using a hybrid argument, we have the following lemma.

Lemma 3.

For an , and let such that , . If the assumption is -hard over the EGA, then the assumption is -hard. More precisely, for every adversary ,

where , , and .

Proof.

Let , , and , where , , and for . Let

Then, we get

□

While an EGA serves as a useful abstraction, it may sometimes be too powerful compared to what is practically achievable. A restricted effective group action (REGA) can be seen as a more limited form of an EGA.

Definition 11

(Restricted effective group action [21,33]). A restricted effective group action is a group action that satisfies the following properties:

- 1.

- The finite group is generated by a set , and ;

- 2.

- The set is finite, and known algorithms efficiently handle membership testing and compute the unique bit-string representation for every element in ;

- 3.

- There exists a distinguished element called the origin whose bit-string representation is known;

- 4.

- There exists an efficient algorithm that, when given in the generating set and any , outputs and where .

Remark 2.

REGA can be instantiated through isogeny-based group actions, such as CSIDH [28]. Additionally, its generator set enables approximate uniform sampling over the group . Furthermore, due to the regularity of the group action , an efficient algorithm exists for drawing elements [33].

Definition 12

(GA-DDH assumption [33,39,40]). Given a REGA , the GA-DDH assumption is -hard if for all adversary , the distinguishing advantage satisfies

where .

Remark 3.

GA-DDH is considered to be applicable to particular group actions derived from isogeny, such as CSIDH [28,33], which is the typical instance of REGA. We stress that our second construction in Section 3.3 is built upon the GA-DDH assumption, which is fundamentally different from the weak pseudo-randomness (WPR) assumption adopted in prior works [13,14]. Not only are the underlying assumptions distinct, but the settings are also different; the WPR assumption is considered over EGA (instantiated via CSI-FiSh), whereas GA-DDH is known not to hold in EGA, as comprehensively analyzed in [13].

3. Reusable Fuzzy Extractor

3.1. Definition of Reusable Fuzzy Extractor

Similar to [13], we introduce a modified version of the reusable fuzzy extractor RFE that incorporates an additional initialization algorithm RFE.Init, which generates the initial public string . Notably, RFE.Init is invoked only once per user. The generated serves as input for the remaining algorithms.

Definition 13

(Reusable fuzzy extractor). An -reusable fuzzy extractor for the metric space consists of four algorithms (, , ,

- –

- inputs the security parameter λ and generates a ;

- –

- takes and an element from the set as input, and then generates the initial public string ;

- –

- takes , , and as input and generates a public helper string and an extracted string ;

- –

- takes the , , , and as input, and then returns .

In addition, it meets the following properties:

- –

- For with , , if , , , , then ;

- –

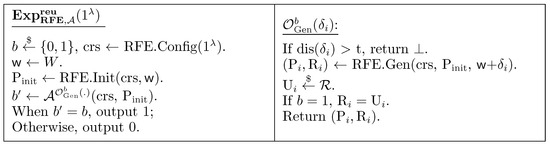

- For any distribution W over metric space satisfying and for any adversary , the following holdswhere , as shown in Figure 1, describes the reusability experiment conducted between a challenger and an adversary .

Figure 1. The reusability experiment .

Figure 1. The reusability experiment .

Remark 4.

The goal of the experiment depicted in Figure 1 is to show that, when adversary is given the public parameters and and further obtains multiple pairs from oracle queries, still cannot distinguish whether the challenge response was generated via the RFE.Gen algorithm or sampled uniformly at random from the output space , even when is known. In other words, even if the same noisy source is used multiple times (n times), and the adversary learns the first pairs , as well as the final helper string , the output still appears uniformly random to . Our security notion focuses on the indistinguishability of from a uniformly random string. The values, being public helper strings generated alongside each , are inherently meant to be public. is initialized only once per user when the user runs the fuzzy extractor scheme for the first time.

3.2. Construction of RFE from LHS Assumption

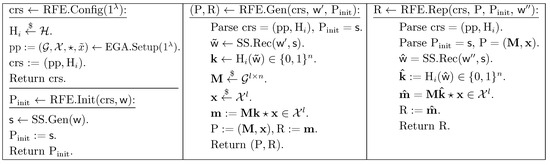

The detailed design of RFE = (RFE.Config, REF.Init, REF.Gen, REF.Rep) from the LHS assumption is depicted in Figure 2, which is composed of the following building blocks:

Figure 2.

Design of reusable fuzzy extractor from LHS.

- –

- An -secure sketch SS = , where .

- –

- An EGA equipped with , which outputs .

- –

- A family of universal hash functions , as defined in Equation (3). Let such that .

Theorem 1.

If is a -secure sketch, , is a family of universal hash functions . The is -hard over the EGA ; then, in Figure 2 is a -reusable fuzzy extractor, where

Proof.

First, we verify the correctness of the construction in Figure 2. If dis(, ) ≤ t, dis(, ) ≤ t, and , then, by the correctness of SS, we have , where ← SS.Rec(, ) and Consequently, . Then, can be computed correctly, i.e., =, and RFE can always reproduce R.

Next, we demonstrate its reusability by presenting a sequence of games and proving the indistinguishability of adjacent ones. The differences between adjacent games are highlighted with underlined text.

Game : Game can be viewed as . More specifically, it can be viewed as the following:

- Challenger selects , samples , and then calls to generate and sets crs:=(pp, ); it sends to .

- selects according to W, calculates , and then sets , returning to .

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , calculates , , and then samples , ; it calculates and sets ; if , ; otherwise, , and it returns to .

- finally outputs a guessing bit ; when , the game outputs 1; otherwise, it outputs 0.

Obviously, we have

Game : is identical to , c:

- 2.

- chooses according to W, calculates , , and then sets , returning to .

- 3.

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets , and then samples , , calculates , and sets ; if , ; otherwise, , and it returns to .

□

Lemma 4.

Proof.

Due to the correctness of the secure sketch and , we deduce that

Furthermore, we can get Hence, we conclude that The lemma follows. □

Game : is equivalent to , with the difference that is replaced by . More specifically, we have the following:

- 2.

- chooses according to W, calculates , , and then sets , returning to .

Lemma 5.

Proof.

We prove this lemma using an argument based on information theory. Note that only appears in the second step to calculate both in and ; thus, is all the information about W that is revealed to . Since our SS is an -secure sketch and , we have

Due to Lemma 1 and the fact that , the statistical distance between and is at most , where and . More precisely, we have the following:

We now define a powerful algorithm and show that if an adversary is capable of distinguishing between and with a non-negligible advantage, then can also distinguish and with the same advantage. Assume receives , where is either or a uniform element . The goal of is to identify which case it is. The algorithm operates as follows:

- Algorithm samples , calls to generate , sets crs:=(pp, ), and returns to .

- sets and and sends to .

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets , samples , , calculates , and sets if , ; otherwise, , and it returns to .

- finally outputs a guessing bit ; when , the game outputs 1; otherwise, it outputs 0.

If is given the tuple , where is derived from and is generated via , it will be able to simulate the game for perfectly. On the other hand, if is given , where is randomly chosen from , it will simulate the game for flawlessly. Therefore, we can conclude that The lemma follows. □

Game : is equivalent to , with the difference that is changed to , where . More specifically, we have the following:

- 3.

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for ., sets , samples , , and , sets , and sets ; if , ; otherwise, , and it returns to .

Lemma 6.

Proof.

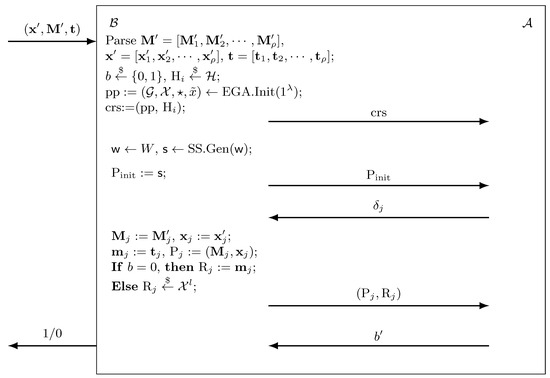

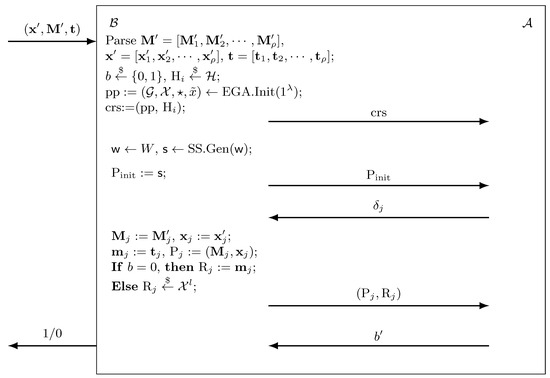

We aim to demonstrate that if a PPT adversary can distinguish between and with a significant advantage, then it is possible to construct a PPT algorithm that can solve the assumption with the same advantage. Suppose is given an LHS tuple , where is either or , and , , , . The goal of is to determine which scenario holds. operates as follows, and the entire interaction is illustrated in Figure 3:

Figure 3.

The entire interaction of Lemma 6.

- Algorithm parses , and , selects , samples , and then calls to generate , setting crs:=(pp, ) and sending to .

- chooses according to W, calculates , and then sets , returning to .

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets and , , and sets ; if , ; otherwise, , returning to .

- finally outputs a guessing bit ; when , the game outputs 1; otherwise, it outputs 0.

If , where , , , then will accurately simulate game for . Conversely, if , where , then perfectly simulates game for . Hence, we deduce that

The lemma follows. □

Lemma 7.

Proof.

In , no matter whether or 1, is always selected uniformly at random from ; then, the adversary ’s probability of making a correct guess is . The lemma follows. □

By putting Equation (1) and Lemma 4–7 together, we obtain that Theorem 1 follows.

3.3. Construction of RFE from GA-DDH Assumption

The detailed design of RFE = (RFE.Config, REF.Init, REF.Gen, REF.Rep) from the GA-DDH assumption is depicted in Figure 4, which is composed of the following building blocks:

Figure 4.

Design of reusable fuzzy extractor from GA-DDH.

- –

- An -secure sketch SS = .

- –

- A REGA equipped with , which outputs with order .

- –

- An average-case -strong extractor. Let such that .

- –

- A family of universal hash functions (While our GA-DDH-based construction requires the seed of the universal hash function to be sampled with high min-entropy (ideally uniformly at random), the design is tolerant to minor imperfections due to the entropy gap between the source and the output. However, for practical implementations, we recommend using a cryptographically secure pseudo-random number generator or high-entropy physical source to ensure robust security).

Theorem 2.

If is a -secure sketch, is a family of universal hash functions . The GA-DDH assumption is -hard over the REGA ; then, in Figure 4 is a -reusable fuzzy extractor, where

Proof.

First, the correctness of the RFE in Figure 4 follows from the correctness of the secure sketch SS. Similar to the proof of Theorem 1, we also use game-based proof to verify reusability. Adjacent games’ differences are highlighted with underlined text.

Game : Game can be viewed as . More specifically, we have the following:

- Challenger selects , samples , and then calls to generate , selecting , , setting crs:=(pp, k, x, ), and returning to .

- chooses according to W, calculates , and then sets , returning to .

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , computes , , and , samples , computes , and then calculates , setting ; if , ; otherwise, , and it returns to .

- finally outputs a guessing bit ; when , the game outputs 1; otherwise, it outputs 0.

Obviously, we deduce that

Game : is equivalent to , aside from some conceptual differences:

- 2.

- chooses according to W, calculates , , , and then sets , returning to .

- 3.

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets , , samples , computes , and then calculates , setting ; if , ; otherwise, , returning to .

□

Lemma 8.

Proof.

Due to the correctness of the secure sketch and , we have

Furthermore, we can get

Hence, we have The lemma follows. □

Game : is identical to , with the difference that is changed to . More specifically, we have the following:

- 2.

- chooses according to W, calculates , , , and then sets , returning to .

Lemma 9.

Proof.

Note that only appears in the second step to compute both in and ; thus, is all the information about W that is revealed to . Meanwhile, since our SS is an -secure sketch and , we have

We now present an algorithm and prove that if an adversary exists that can distinguish from with a non-negligible advantage, then can distinguish between and with the same advantage. Let receive , where is either or a uniformly chosen element . The task of is to identify which case is given. Algorithm operates as follows:

- Algorithm selects , samples , and then calls to generate ; it samples , sets crs:=(pp, k, x, ), and returns to .

- sets , , , and returns to .

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets , , samples , computes , , and sets ; if , ; otherwise, , returning to .

- finally outputs a guessing bit ; when , the game outputs 1; otherwise, it outputs 0.

Assuming that is given the tuple , where is generated by , k is sampled from , and is created via , will successfully simulate game for . On the other hand, if is provided with the tuple , where is randomly chosen from , will simulate game for perfectly. Consequently, we conclude that

The lemma follows. □

Game : is identical to , with the difference that is changed to . More specifically, we have the following:

- 2.

- chooses according to W, calculates , , , and then sets , returning to .

Lemma 10.

Proof.

Recall that in , , (i.e., ), and are public in crs. According to Lemma 2, we have where , , and . Thus, y is statistically indistinguishable in and . This proof follows similarly to that of Lemma 5, and can thus be easily derived. The lemma follows. □

Game : is equivalent to , with the difference that is changed to , where . More specifically, we have the following:

- 3.

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets , , samples , computes , samples , and then calculates , setting ; if , ; otherwise, , returning to .

Lemma 11.

Proof.

We prove this lemma through a series of games , where . The specific description of is provided below.

- Challenger selects , samples , and then calls to generate , selecting and ; then, it sets crs:=(pp, k, x, ) and returns to .

- chooses according to W, calculates , , , sets , and returns to .

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets , , samples , computes . If , samples , and then sets ; otherwise, it sets . Then, it sets ; if , ; otherwise, , returning to .

- finally outputs a guessing bit ; when , the game outputs 1; otherwise, the outputs 0.

Obviously, we have , which is identical to , and is equivalent to . Before proving this lemma, let us first prove the following proposition. □

Proposition 1.

Proof.

We will show that if there exists an adversary that can distinguish and with a non-negligible advantage, then there exists a PPT algorithm that can solve the GA-DDH problem with the same advantage. Assume that is provided with a tuple , where and , and is either or a random element from . The goal of is to determine which case holds. Algorithm operates as follows:

- Algorithm selects , samples , and then calls to generate ; it samples , sets crs:=(pp, k, x, ), and sends to .

- chooses according to W, calculates and , implicitly sets , and then sets , returning to .

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets , implicitly sets , samples , and computes . If , it samples and sets ; if , it sets , ; if , it sets . Then, it sets ; if , ; otherwise, , returning to .

- finally outputs a guessing bit ; when , the game outputs 1; otherwise, it outputs 0.

If , then accurately simulates game for ; if , then perfectly simulates game for . Hence, we conclude that

The proposition follows. □

Therefore, by using Proposition 1 times, we obtain The lemma follows.

Game : is identical to , except that is changed to , where . More specifically, we have the following:

- 3.

- may request up to queries from the generation oracle. Upon obtaining an offset satisfying for , sets and , samples , computes , samples , and then sets , setting ; if , ; otherwise, , returning to .

Lemma 12.

Proof.

Note that in , , . Since the group action is regular, according to Remark 1 and Remark 2, is uniformly distributed over in in the REGA setting. Thus, the distributions of in and are identical. The lemma follows. □

Lemma 13.

Proof.

The proof is similar to that of Lemma 7 and is omitted for brevity. □

Putting Equation (2) and Lemmas 8–13 together, we obtain that Theorem 2 follows.

4. Instantiation

4.1. Instantiation of Building Blocks

4.1.1. Syndrome-Based Secure Sketch

Considering a linear error-correcting code that is and lies within the space . Specifically, , where is an parity-check matrix. As proposed in [1], a syndrome-based secure sketch can be constructed using an efficient -linear error-correcting code, and the construction can be summarized as follows:

- –

- ;

- –

- .

Lemma 14.

Given an error-correcting code, it is feasible to construct an secure sketch, which is efficient if encoding and decoding are efficient.

As there are efficient -linear error-correcting codes where , the syndrome-based secure sketch can handle a linear proportion of errors.

4.1.2. Universal Hash Functions and Strong Extractor

In our construction 1, we use the following commonly used family of universal hash functions [8,14].

where , symbol “·” represents matrix-vector multiplication in , and i is interpreted as an Toeplitz matrix.

In our construction 2, we use the universal hash function presented in Lemma 2. More precisely, we have the following:

The leftover hash lemma (Lemma 1) implies that universal hash functions are good (average-case strong) extractors. The construction of universal hash functions in Equation (3) is a good instance.

4.1.3. (Restricted) Effective Group Action

- EGA from CSI-FiSh. As stated in [13], we can derive a regular and abelian effective group action (EGA) from isogeny via CSI-FiSh, which precomputes the group structure of CSIDH-512 (to optimize sampling from the ideal class group , one can precompute its group structure, typically making cyclic. Uniform sampling from then becomes efficient. Sampling from can be realized by applying a random group element to a fixed representative, leveraging the regularity of the group action. This strategy is used in prior isogeny-based works such as CSI-FiSh.).

- , where p specifies the prime field, N denotes the order of the ideal class group , is a generator of , and is the base elliptic curve defined by .

- Define , , and set the origin . The group supports efficient group operations, including equality checking, random sampling, addition, and inversion.

- REGA from CSIDH. As stated in [41], let p be a large prime of the form , where each is a small distinct odd prime. We consider the elliptic curve over , which is supersingular. The endomorphism ring of this curve over is , where is the Frobenius endomorphism. is the set of elliptic curves defined over whose endomorphism ring is . The ideal class group acts on this set, which is formalized by a map.

We abstract the generation process of (R)EGA as an algorithm called , which outputs the description of (R)EGA.

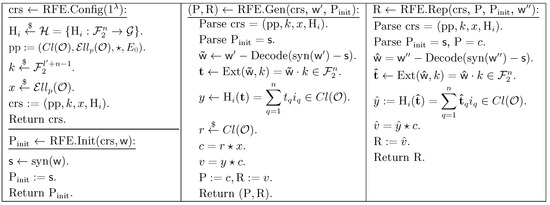

4.2. Instantiations of Our Construction 1 and Construction 2

Based on concrete instantiations of the aforementioned building blocks, Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate the complete instantiations of our reusable fuzzy extractors under the LHS assumption and the GA-DDH assumption, respectively.

Figure 5.

Instantiation of reusable fuzzy extractor from LHS.

Figure 6.

Instantiation of reusable fuzzy extractor from GA-DDH.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we present two constructions of RFE under isogeny-based assumptions and rigorously prove their security. Indeed, our motivation stems from the observation that existing post-quantum secure FE schemes (whether reusable or robust) are predominantly based on lattice-based hardness assumptions, such as the LWE assumption. Excessive dependence on lattice assumptions has led to a lack of diversity in post-quantum FE constructions. If significant progress were to be made in solving lattice problems, the security of these lattice-based fuzzy extractors would be at serious risk.

Moreover, we note that fuzzy extractors based on isogeny assumptions are still rare. To the best of our knowledge, only two such constructions [13,14] exist, both published last year and relying on the WPR assumption, a specific isogeny-based hardness assumption. In contrast, other cryptographic primitives based on isogeny assumptions, such as key exchange protocols [28] and digital signatures [15], have seen rapid development. This disparity suggests that adapting isogeny-based assumptions to the fuzzy extractor setting is non-trivial and that constructing reusable or robust fuzzy extractors using conventional techniques is far from straightforward—a challenge also noted in [13]. Therefore, inspired by the refinement of the RRFE security model in [13], we propose a similar modification to the security model of RFE. This refinement eliminates the need to rely on the key-shift security of underlying primitives or assumptions in the security proof. Based on the optimized model, we construct two reusable fuzzy extractors under the LHS assumption and the GA-DDH assumption, respectively. Compared to the construction in [13,14], our first scheme is able to extract longer uniform strings (l-times longer), albeit at a higher computational cost. Moreover, our second construction achieves the same output length as the schemes in [13,14] while incurring a lower computational cost than [13] and nearly matching the efficiency of [14].

Our constructions utilize only some fundamental cryptographic primitives: secure sketches for fuzzy error correction, and hash functions or strong extractors to extract uniform randomness, which can be further employed in other cryptographic applications, such as serving as keys for symmetric or asymmetric encryption schemes. On the one hand, we achieve the reusability of FE, ensuring security across multiple extractions from the same noisy source. On the other hand, we recognize that robustness is also a crucial component of fuzzy extractor security; it protects against active attacks on the public helper string. However, we have not yet identified an effective or satisfactory method for achieving robustness in our setting. In particular, achieving both robustness and reusability in a single fuzzy extractor remains an open challenge, which we leave for future investigation.

In addition, an interesting open direction for future research is to investigate the applicability of our framework to multi-factor fuzzy sources, such as combinations of voice and facial biometrics. This would require addressing challenges in feature fusion, noise modeling, and entropy extraction beyond the single-source setting considered in this work. Another promising direction for future work is to investigate the practical deployment of our constructions on resource-constrained edge systems, as well as to evaluate their robustness under real-world noise patterns. Meanwhile, it is important to explore the integration of our reusable fuzzy extractor constructions with other post-quantum cryptographic protocols, such as key exchange, authentication, and secure enrollment schemes. In particular, combining our techniques with post-quantum primitives (e.g., isogeny-based or lattice-based protocols) may yield end-to-end secure systems that are resilient against quantum adversaries and robust to input noise.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; Methodology, Y.W.; Validation, T.J.; Formal analysis, T.J.; Writing—original draft, T.J.; Writing—review & editing, Y.W. and W.L.; Supervision, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62102077), Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 24ZR1401300).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the editors and reviewers for their time and consideration in evaluating this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dodis, Y.; Reyzin, L.; Smith, A.D. Fuzzy extractors: How to generate strong keys from biometrics and other noisy data. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2004, Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Interlaken, Switzerland, 2–6 May 2004; Cachin, C., Camenisch, J., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 3027, pp. 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Bauer, L.; Bonneau, J.; Cranor, L.F.; Thomas, J.; Ur, B. Can Unicorns Help Users Compare Crypto Key Fingerprints? In Proceedings of the CHI’17: 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3787–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Jain, A.K. Longitudinal study of fingerprint recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8555–8560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Al-Sarawi, S.F.; Abbott, D. Physical unclonable functions. Nat. Electron. 2020, 3, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Liscidini, M.; Gaeta, A.L.; Weiner, A.M.; Lukens, J.M. Frequency-bin photonic quantum information. Optica 2023, 10, 1655–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyen, X. Reusable cryptographic fuzzy extractors. In Proceedings of the CCS 2004, 11th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Washington, DC, USA, 25–29 October 2004; Atluri, V., Pfitzmann, B., McDaniel, P.D., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetti, R.; Fuller, B.; Paneth, O.; Reyzin, L.; Smith, A.D. Reusable fuzzy extractors for low-entropy distributions. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2016, Proceedings of the 35th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Vienna, Austria, 8–12 May 2016; Fischlin, M., Coron, J., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 9665, pp. 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Liu, S.; Han, S. Reusable fuzzy extractor from the decisional Diffie-Hellman assumption. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2018, 86, 2495–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Liu, S. Reusable fuzzy extractor from LWE. In Proceedings of the ACISP 2018, Wollongong, Australia, 11–13 July 2018; Susilo, W., Yang, G., Eds.; LNCS. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 10946, pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Liu, S. Robustly reusable fuzzy extractor from standard assumptions. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2018, Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Brisbane, Australia, 2–6 December 2018; Peyrin, T., Galbraith, S., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 11274, pp. 459–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Liu, S.; Gu, D. Generic constructions of robustly reusable fuzzy extractor. In Public-Key Cryptography—PKC 2019, Proceedings of the 22nd IACR International Conference on Practice and Theory of Public-Key Cryptography, Beijing, China, 14–17 April 2019; Lin, D., Sako, K., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 11443, pp. 349–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Gu, D.; Chen, K. Reusable fuzzy extractor based on the LPN assumption. Comput. J. 2020, 63, 1826–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Han, S. Robustly Reusable Fuzzy Extractor from Isogeny. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2024, 1008, 114677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Han, S. Reusable Fuzzy Extractor from Isogeny. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Provable Security, Gold Coast, Australia, 25–27 September 2024; Liu, J.K., Chen, L., Sun, S., Liu, X., Eds.; LNCS. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 14904, pp. 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beullens, W.; Kleinjung, T.; Vercauteren, F. CSI-FiSh: Efficient isogeny based signatures through class group computations. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2019, Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Kobe, Japan, 8–12 December 2019; Galbraith, S., Moriai, S., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 11921, pp. 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.J.; Lange, T. Post-quantum cryptography. Nature 2017, 549, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dam, D.; Tran, T.; Hoang, V.; Pham, C.; Hoang, T. A survey of post-quantum cryptography: Start of a new race. Cryptography 2023, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, K.; Yu, Y. The hardness of LPN over any integer ring and field for PCG applications. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2024, Proceedings of the 43rd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Zurich, Switzerland, 26–30 May 2024; Joye, M., Leander, G., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, M.; Stehlé, D.; Wallet, A. On the ring-LWE and polynomial-LWE problems. In Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2018, Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Tel Aviv, Israel, 29 April–3 May 2018; Nielsen, J., Rijmen, V., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 10820, pp. 146–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peikert, C. A decade of lattice cryptography. Found. Trends® Theor. Comput. Sci. 2016, 10, 283–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamati, N.; De Feo, L.; Montgomery, H.; Patranabis, S. Cryptographic group actions and applications. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2020, Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 7–11 December 2020; Moriai, S., Wang, H., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 12492, pp. 411–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, L.; Fouotsa, T.B.; Panny, L. Isogeny problems with level structure. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2024, Proceedings of the 43rd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Zurich, Switzerland, 26–30 May 2024; Joye, M., Leander, G., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 14657, pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, A. A new isogeny representation and applications to cryptography. In Advances in Cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2022, Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Taipei, Taiwan, 5–9 December 2022; Agrawal, S., Lin, D., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 13792, pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jao, D.; De Feo, L. Towards quantum-resistant cryptosystems from supersingular elliptic curve isogenies. In Post-Quantum Cryptography, Proceedings of the PQCrypto 2011, Taipei, Taiwan, 29 November–2 December 2011; Yang, B.Y., Ed.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 7071, pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castryck, W.; Decru, T. An efficient key recovery attack on SIDH. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2023, Proceedings of the 42nd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2023; Hazay, C., Stam, M., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 14008, pp. 423–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouotsa, T.B.; Petit, C. A new adaptive attack on SIDH. In Topics in Cryptology—CT-RSA 2022, Proceedings of the RSA Conference 2022, Virtual, 1–2 March 2022; Galbraith, S.D., Ed.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 13161, pp. 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, A.; Fouotsa, T.B. New SIDH countermeasures for a more efficient key exchange. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2023, Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Guangzhou, China, 4–8 December 2023; Guo, J., Steinfeld, R., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 14445, pp. 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castryck, W.; Lange, T.; Martindale, C.; Panny, L.; Renes, J. CSIDH: An efficient post-quantum commutative group action. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2018, Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Brisbane, Australia, 2–6 December 2018; Peyrin, T., Galbraith, S., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 11274, pp. 395–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamati, N.; Malavolta, G.; Rahimi, A. Candidate trapdoor claw-free functions from group actions with applications to quantum protocols. In Theory of Cryptography, Proceedings of the 20th International Conference, TCC 2022, Chicago, IL, USA, 7–10 November 2022; Kiltz, E., Vaikuntanathan, V., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 13747, pp. 266–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamati, N.; Patranabis, S. Cryptographic Primitives with Hinting Property. J. Cryptol. 2024, 37, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolbunov, A. Cryptographic Schemes Based on Isogenies. Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castryck, W.; Sotáková, J.; Vercauteren, F. Breaking the decisional Diffie-Hellman problem for class group actions using genus theory. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2020, Proceedings of the 40th Annual International Cryptology Conference, CRYPTO 2020, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 17–21 August 2020; Micciancio, D., Ristenpart, T., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 12171, pp. 92–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Liu, S.; Han, S. Universal composable password authenticated key exchange for the post-quantum world. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2024, Proceedings of the 43rd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Zurich, Switzerland, 26–30 May 2024; Joye, M., Leander, G., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 10820, pp. 120–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y. CAPYBARA and TSUBAKI: Verifiable random functions from group actions and isogenies. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2023. Volume 1. Available online: https://cic.iacr.org/p/1/3/1 (accessed on 1 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Heimberger, L.; Hennerbichler, T.; Meisingseth, F.; Ramacher, S.; Rechberger, C. OPRFs from isogenies: Designs and analysis. In Proceedings of the ASIA CCS ’24: 19th ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Singapore, 1–5 July 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, J.; Hartmann, D.; Kiltz, E.; Kunzweiler, S.; Lehmann, J.; Riepel, D. Group action key encapsulation and non-interactive key exchange in the QROM. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2022, Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Taipei, Taiwan, 5–9 December 2022; Agrawal, S., Lin, D., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 13792, pp. 36–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apon, D.; Cho, C.; Eldefrawy, K.; Katz, J. Efficient, reusable fuzzy extractors from LWE. In Proceedings of the CSCML 2017, Beer-Sheva, Israel, 29–30 June 2017; Dolev, S., Lodha, S., Eds.; LNCS. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10332, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regev, O. On lattices, learning with errors, random linear codes, and cryptography. J. ACM (JACM) 2009, 56, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneh, D.; Kogan, D.; Woo, K. Oblivious pseudorandom functions from isogenies. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2020, Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 7–11 December 2020; Moriai, S., Wang, H., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 12492, pp. 520–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, T.; Takashima, K.; Aikawa, Y.; Takagi, T. An efficient authenticated key exchange from random self-reducibility on CSIDH. In Proceedings of the Information Security and Cryptology—ICISC 2020, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2–4 December 2020; Hong, D., Ed.; LNCS. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 12593, pp. 58–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Eisenhofer, T.; Kiltz, E.; Kunzweiler, S.; Riepel, D. Password-authenticated key exchange from group actions. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2022, Proceedings of the 42nd Annual International Cryptology Conference, CRYPTO 2022, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 15–18 August 2022; Dodis, Y., Shrimpton, T., Eds.; LNCS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 13508, pp. 699–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).