Abstract

Pavement cracks are a critical indicator for assessing structural health and forecasting deterioration trends. Accurate and automated crack classification is of paramount importance for the intelligent maintenance of road structures. Inspired by the principles of symmetry—which often lead to robust and efficient structures in both nature and engineering—this paper proposes ASPCCNet, a lightweight network that embeds these principles into its core design. The network centers on a novel building block, AugShuffleBlock, which embodies a symmetry-informed design through the integration of Partial Convolution (PConv), a tunable channel splitting mechanism (AugShuffle), and the Channel Prior Convolutional Attention (CPCA). This design achieves efficient feature extraction and fusion with minimal computational overhead. Experimental results on the public RCCD dataset demonstrate that ASPCCNet significantly outperforms mainstream lightweight models, achieving an F1-score of 0.816, which is 6.4% to 10.9% higher than other mainstream models, with only 0.294 M parameters and 48.68 MFLOPs. This work showcases how a symmetry-guided design philosophy can be leveraged to achieve a superior balance between accuracy and efficiency for real-time edge deployment.

1. Introduction

Pavement cracks are a critical indicator for assessing structural health and forecasting deterioration trends. Different types of cracks, such as transverse, longitudinal, and alligator cracks, often signify distinct underlying pathologies, propagation rates, and potential impacts. Consequently, accurate and automated crack classification is of paramount importance for the intelligent maintenance of road structures, data-driven repair decision-making, and the long-term sustainable development of infrastructure.

The evolution of crack classification technology has clearly followed a path from manual feature design to deep learning. Early machine learning methods primarily included techniques such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [1,2,3] and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [4,5]. Research on ANNs explored various feature designs, such as the “projection histogram” technique [6], moment invariants [4], statistical values (mean and standard deviation) [7], proximity values [5], morphological features [8], and wavelet Radon transforms [9]. Similarly, research on SVMs focused on innovations in feature engineering, including candidate region extraction via multi-directional non-minimum suppression [1], texture features derived from color and Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrices (GLCM) [10], and the combination of texture and shape descriptors [2]. Beyond ANNs and SVMs, other machine learning algorithms such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [11], AdaBoost [12], Random Forest [13], and clustering [14,15] have also been widely applied in the field of pavement crack detection, collectively constituting a diverse methodology based on feature engineering.

However, although these methods achieved a certain level of success, their performance fundamentally relied heavily on the design and extraction of manual features. This dependency resulted in poor model generalization, making it difficult to adapt to the complex and variable conditions of real-world road environments, such as illumination, stains, and background interference. They were typically suitable only for specific scenarios, lacking robustness.

The rise in deep learning provided a powerful solution to this bottleneck. Models based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can learn hierarchical, high-level feature representations directly from raw image data in an end-to-end manner, significantly reducing the reliance on expert knowledge and demonstrating superior robustness. These CNN-based approaches can be broadly categorized into image-level [16,17] and patch-level [18,19,20,21,22] approaches. The patch-level approach is more prevalent among researchers as it expands the training data and provides coarse localization information.

Early CNN research primarily focused on improving model accuracy by extensively adopting and fine-tuning complex, pre-trained models. Comprehensive studies have shown that foundational architectures like AlexNet [22,23] and VGGNet [24,25,26] were successfully applied to crack identification tasks, demonstrating the powerful feature extraction capabilities of CNNs. Subsequently, deeper networks like ResNet, through the introduction of residual connections, effectively mitigated the vanishing gradient problem in deep model training, significantly enhanced classification accuracy, and became one of the widely adopted benchmark models in the field [27,28,29]. The integration of attention mechanisms (e.g., SE [30], CBAM [31]), by enabling the model to focus on more informative channels and spatial locations, further pushed the performance ceiling.

However, the pursuit of high accuracy using deep, dense models like VGG and ResNet introduced a new challenge: their enormous parameter counts and high computational complexity made them difficult to deploy on computationally constrained edge devices (e.g., embedded systems, unmanned aerial vehicles), failing to meet the urgent demand for real-time road inspection.

In response, researchers turned to lightweight models. General-purpose lightweight architectures such as MobileNet [32,33] and ShuffleNet [30] have been introduced to the field. However, most existing solutions directly adopt these generic lightweight backbones, failing to specialize them for the crack image classification task. This leads to the core problems of significant accuracy loss and a suboptimal efficiency-accuracy trade-off. Key challenges remain inadequately addressed: (1) how to integrate advanced attention mechanisms into the lightweight core with minimal overhead [31], and (2) how to optimize multi-scale feature fusion to handle crack diversity. Although new architectures like Transformer [34] and Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) [35] are being explored, their performance and efficiency under lightweight constraints still require improvement.

Addressing these challenges requires not only engineering ingenuity but also foundational design principles. Beyond specific engineering improvements, this work is also inspired by the broader concept of symmetry. In mathematics and physics, symmetry is often associated with stability, efficiency, and elegance. In the context of deep learning architecture, structural symmetry—such as the use of balanced, parallel pathways (e.g., dual branches) and repetitive, modular blocks—can lead to more robust and hardware-efficient models. This paper explores this idea by designing a network where the core building blocks explicitly incorporate and manipulate both symmetric and carefully calibrated asymmetric elements to optimize information flow and computational burden. We demonstrate that this can be achieved by reinterpreting and integrating state-of-the-art efficient operations—such as PConv, AugShuffle, and attention mechanisms—within a symmetry-aware framework.

Guided by this principle, we focus on the problem of real-time, high-accuracy pavement crack classification, aiming to develop a lightweight solution that embodies this efficient and balanced design philosophy. To this end, we draw inspiration from recent advanced techniques in efficient networks and reinterpret their integration through the lens of symmetry.

Specifically, we organically integrate designs like Partial Convolution (PConv) [36], Augmented Channel Shuffle (AugShuffle) [37], and the CPCA attention mechanism [38], into our network. The main contributions are as follows:

(1) We construct an efficient lightweight network named ASPCCNet (Augmented ShuffleNet for Pavement Crack Classification). Based on ShuffleNetV2, it seeks a superior accuracy–efficiency trade-off through an optimized strategy for stacking its fundamental building blocks, resulting in a harmonious and efficient hierarchical structure.

(2) We design a novel fundamental building block, termed AugShuffleBlock, which integrates Partial Convolution (PConv), Augmented Channel Shuffle (AugShuffle), and a lightweight CPCA attention mechanism. This design achieves more efficient feature extraction and fusion with low computational overhead, by effectively balancing symmetric operations with controlled asymmetry.

(3) Extensive experiments on public datasets demonstrate that ASPCCNet significantly surpasses mainstream lightweight models in classification accuracy while substantially reducing both the parameter count and computational complexity. It also maintains highly competitive inference speed, ultimately achieving excellent overall performance in accuracy, efficiency, and lightweight design.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 elaborates on the principles behind the core components of ASPCCNet and details its overall architecture. Section 3 provides a comprehensive experimental evaluation and discussion, encompassing comparative experiments against state-of-the-art models and systematic ablation studies. Finally, Section 4 concludes the paper and suggests potential avenues for future research.

2. Methods

2.1. Design Philosophy Guided by Symmetry

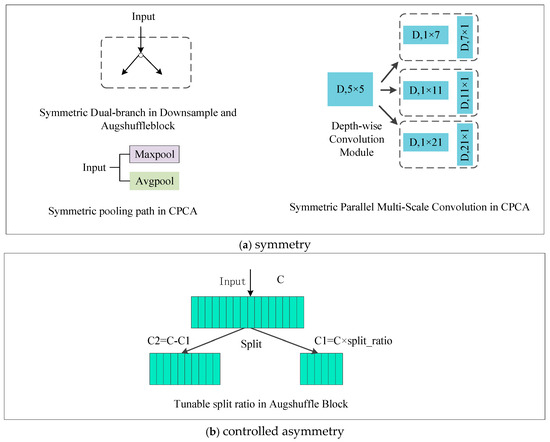

Inspired by the principle that symmetry in nature and engineering often leads to robust and efficient structures, this work elevates symmetry and its unified oppo-site—controlled asymmetry—to a core design philosophy. As illustrated in Figure 1, our strategy involves the synergistic use of global structural symmetry and localized controlled asymmetric operations.

Figure 1.

The Symmetry Design Philosophy in ASPCCNet.

At the macro-architectural level, we incorporate various symmetric designs to ensure model robustness and hardware efficiency. These include the symmetric du-al-branch structures (e.g., in Downsample modules and the AugShuffle Block), the co-existing global average and max pooling paths within the CPCA attention mechanism, and the parallel multi-scale depthwise convolutions. These elements form a stable and efficient backbone for the network.

At the micro-modular level, we strategically introduce controlled asymmetry to enhance flexibility. A prime example is the Tunable Channel Split Ratio mechanism in the AugShuffle Block. This mechanism breaks the static symmetry of equal channel splitting, enabling the model to dynamically allocate computational resources based on input complexity, thereby allowing for finer-grained control over the performance–efficiency trade-off.

This co-design philosophy—“global symmetry establishes the foundation, while local asymmetry enables optimization”—constitutes the theoretical foundation for ASPCCNet’s superior accuracy–efficiency balance.

2.2. ASPCCNet Network Architecture

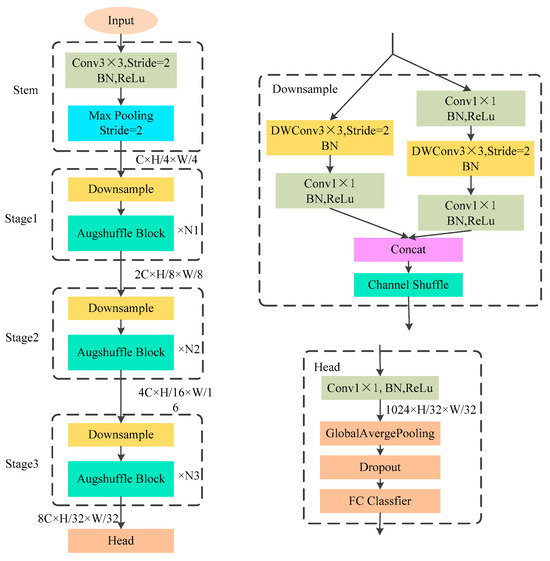

Guided by the design philosophy outlined in Section 2.1, we construct the light-weight ASPCCNet, whose overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 2. It incorporates advanced design philosophies and modules from ShuffleNetV2, FasterNet, and AugShuffleNet, and integrates the recent CPCA attention mechanism. From a design perspective, the network embodies principles of structural symmetry and balance, contributing to its computational efficiency and robustness.

Figure 2.

The Network Architecture of ASPCCNet.

The ASPCCNet network comprises three main components: the Stem, the Stages, and the Head. The Stem, serving as the initial part of the network, employs a 3 × 3 standard convolution with a stride of 2 followed by a Max Pooling operation. This design rapidly reduces the feature map resolution to 1/4 of the original input size. This approach not only significantly decreases the model’s parameter count and computational complexity but also preserves essential image features while reducing redundant information.

The intermediate Stages constitute the primary feature extraction component of the network. Stages 1 to 3 consist of repeatably stackable Downsample modules and Augmented Channel Shuffle modules (denoted as AugShuffle Block in the figure). The repetitive, modular stacking of building blocks across stages exhibits a form of translational symmetry in the network’s depth, which simplifies the design and enhances hardware efficiency. The Downsample module is primarily adapted from the downsampling block design of ShuffleNetV2, containing left and right branches. The left branch consists of a 3 × 3 Depth-wise Convolution (DWConv) with a stride of 2, followed by a 1 × 1 convolution. The right branch employs a structure with two 1 × 1 convolutions sandwiching a 3 × 3 Depth-wise Convolution. This dual-branch configuration forms a foundational symmetric (or balanced) structure for processing features, where the two paths operate in parallel before their outputs are integrated. It is noteworthy that the DWConv here includes only a Batch Normalization (BN) layer and omits an activation function. This design choice aims to reduce computational load and memory access costs, thereby enhancing computational efficiency.

The Head, serving as the final part of the model, first performs further information fusion through a 1 × 1 convolutional layer, followed by global average pooling to extract the feature vector. Subsequently, this feature vector is fed into the final fully connected classifier to obtain the model’s output. A Dropout layer can be incorporated during this process as needed to effectively prevent model overfitting.

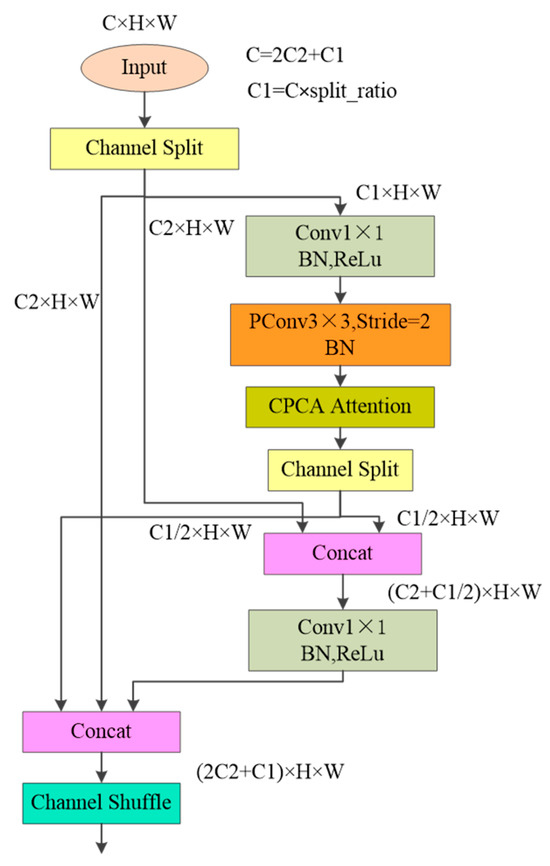

2.3. Design of the Core Building Block: AugShuffle Block

As previously mentioned, the core components of Stages 1–3 are the repeatably stackable AugShuffle Blocks. This module is pivotal to the network’s efficient feature extraction, and its design incorporates three key enhancements. First, the original Shuffle Block is augmented to become the AugShuffle Block, which features tunable channel splitting and intermediate-layer interaction. Second, Partial Convolution (PConv) is introduced to maximize computational efficiency. Finally, the Channel Prior Convolutional Attention (CPCA) mechanism is integrated to bolster feature representation capabilities. The following subsections elaborate on each of these enhancements in detail.

2.3.1. AugShuffle: Tunable Channel Splitting and Intermediate-Layer Interaction

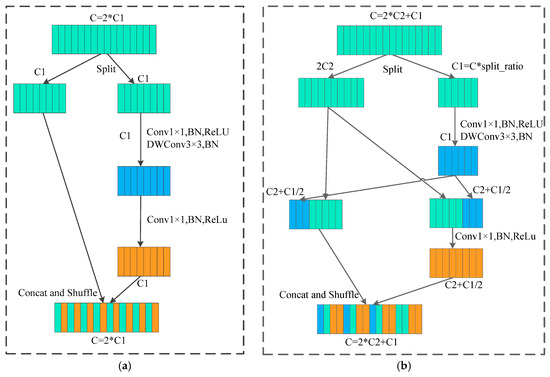

The first enhancement transforms the foundational Shuffle Block from ShuffleNetV2 into the AugShuffle Block, with its structural evolution depicted in Figure 3. Compared to the original module, the AugShuffle Block introduces two key refinements:

Figure 3.

Improvement from Shuffle Block to AugShuffle Block: (a) Shuffle Block in ShufflenetV2; (b) AugShuffle Block.

(1) Tunable Channel Split Ratio: The fixed channel split ratio (split_ratio) is reconfigured as a tunable hyperparameter. This allows for flexible adjustment of the channel count in each branch, facilitating subsequent optimization of the block’s overall efficiency in terms of parameters, computational cost, and inference speed.

(2) Enhanced Intermediate-layer Information Interaction: The original ShuffleNetV2 only performs feature concatenation and channel shuffle at the very end of its two branches, underutilizing the features from intermediate layers. The AugShuffle Block introduces an interaction mechanism after the intermediate depthwise convolution (DWConv) layer: it stores a portion of the newly generated feature maps into a shared “feature bank” while simultaneously retrieving more historical feature maps from it. This mechanism achieves effective channel expansion without introducing significant extra computational overhead, thereby enabling more thorough and efficient utilization of feature information.

By employing a tunable channel split ratio , AugShuffle reduces computational consumption compared to the original Shuffle Block. A quantitative analysis for a typical block (comprising two standard 1 × 1 convolutions sandwiching one depthwise separable convolution) is provided below.

Let the input feature be , where C denotes the number of input channels, and h and w represent the spatial dimensions. The split ratio be r determines the number of channels in the first branch as C1 = rC. The kernel size of the depthwise separable convolution is . The computational cost (in FLOPs) for a standard convolution is ; for a depthwise separable convolution, it is .

For the AugShuffle Block, the computational cost of the first 1 × 1 convolution is , the intermediate depthwise separable convolution is . The final 1 × 1 convolution has an output channel number of C/2, leading to a cost of . Thus, the total computational cost of the AugShuffle Block is expressed as:

Setting the split ratio r = 0.5 yields the computational cost of the original Shuffle Block. Let α represent the computational ratio of AugShuffle to the original Shuffle Block, given by:

Theoretical analysis indicates that as r decreases, the AugShuffle Block exhibits higher computational efficiency compared to the original module.

The evolution from the Shuffle Block to the AugShuffle Block, as depicted in Figure 3, can be interpreted through the lens of symmetry. The original Shuffle Block (a) exhibits a static, structural symmetry, primarily characterized by its equal channel splitting between two branches. In contrast, the proposed AugShuffle Block (b) introduces dynamic and controlled asymmetry. The tunable channel split ratio breaks this equal division, allowing for a more flexible and potentially more efficient allocation of computational resources across pathways. Furthermore, the intermediate feature bank interaction mechanism enables a cyclic utilization of features, where past and present features are dynamically balanced and reused, enriching the representational capacity.

2.3.2. Introduction of Partial Convolution (PConv)

The second key enhancement is the introduction of Partial Convolution (PConv) from FasterNet, which replaces the 3 × 3 depthwise separable convolution in the AugShuffle Block with a 3 × 3 partial convolution. This step aims to minimize redundant computations and memory access, thereby achieving more efficient spatial feature extraction.

The core concept of PConv is illustrated in Figure 4 in reference [36]. Unlike standard or depthwise separable convolutions, PConv performs convolution only on a subset of input feature map channels (denoted as in the figure), while leaving the remaining channels unchanged. This strategy significantly reduces computational complexity and memory access. Assuming both input and output channel counts are C, FLOPs of PConv is , and its memory access cost (MAC) is . When , the FLOPs of PConv are only 1/16 of a standard convolution, and the MAC is only 1/4, demonstrating a substantial advantage. Since PConv utilizes only partial channel information, a pointwise convolution (PWConv, i.e., 1 × 1 convolution) is typically appended afterwards in practice to facilitate information flow across all channels.

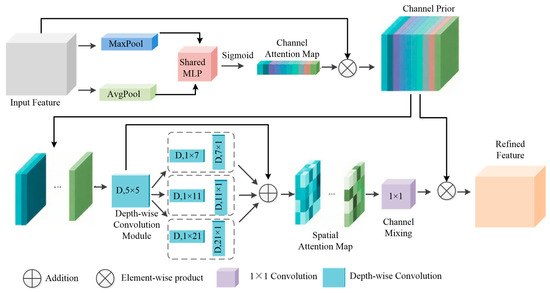

Figure 4.

The Channel Prior Convolutional Attention Mechanism (CPCA).

2.3.3. Integration of Channel Prior Convolutional Attention (CPCA)

The third key enhancement involves the integration of the Channel Prior Convolutional Attention (CPCA) mechanism to bolster the module’s capability in capturing critical features within complex scenes. Prevailing attention mechanisms, such as SE and CBAM, exhibit limitations when dealing with the low contrast and morphological diversity of crack images. The SE module focuses solely on the channel dimension, thereby restricting its ability to select crucial spatial regions. While CBAM incorporates both channel and spatial attention, it imposes a uniform spatial weight distribution across all channels; this consistency can introduce interference when processing background noise. Furthermore, some self-attention-based mechanisms incur substantial computational overhead.

The CPCA module is designed to achieve a dynamic distribution of attention weights across both channel and spatial dimensions while avoiding computationally intensive operations. It comprises two main components, Channel Attention (CA) and Spatial Attention (SA), with its core architecture illustrated in Figure 4.

(1) Channel Attention (CA) Module: The design of this module is similar to the channel attention component in CBAM. The input feature map is initially subjected to both global average pooling and max pooling operations. These two symmetric pooling pathways capture complementary information from the feature maps. The resulting feature vectors from these two pooling operations are summed and then fed into a shared Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). Finally, a one-dimensional channel attention map, denoted as , is generated via a Sigmoid activation function.

(2) Spatial Attention (SA) Module: This constitutes the innovative core of CPCA. Departing from the approach of enforcing an identical spatial attention map across all channels, this module employs a symmetrically arranged set of parallel depthwise separable convolutions to capture spatial relationships. This strategy effectively extracts multi-scale spatial features while preserving the independence between channels (i.e., the channel prior), and significantly reduces computational complexity. Specifically, the module utilizes a set of parallel depthwise strip convolutions with varying kernel sizes to process features, thereby capturing contextual information from different orientations. The use of paired horizontal and vertical strip convolutions ensures a balanced capture of features across orientations. These multi-scale features are subsequently fused through a 1 × 1 convolutional layer to produce a refined three-dimensional spatial attention map, .

Collectively, the design of CPCA is guided by a symmetry-aware philosophy that prioritizes balanced and comprehensive feature analysis. The channel attention module leverages symmetric pooling pathways to establish a complete context. The spatial attention module, through its symmetrically parallel multi-scale convolutions and structurally symmetric factorized kernels, ensures an unbiased and efficient capture of spatial relationships. This principled approach enables CPCA to dynamically and equitably distribute attention across both channel and spatial dimensions, making it particularly adept at handling the diverse and complex patterns found in pavement crack imagery.

For a given input feature map , the forward pass of the CPCA module proceeds as follows:

- First, the channel attention map is element-wise multiplied with the input feature X, yielding the channel-refined feature

- Next, the spatial attention module processes to generate the spatial attention map

- Finally, is element-wise multiplied with to produce the ultimate output feature

By replacing the depthwise separable convolution in the AugShuffle Block with PConv and integrating the CPCA attention mechanism, the feature extraction and representation capabilities of the block are comprehensively enhanced. The final structure of the complete AugShuffle Block, incorporating all three enhancements described above, is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The structure of the complete AugShuffle Block.

3. Experiment and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Dataset

This experiment employs the RCCD dataset [39], which was curated based on manually cropped images provided by the U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). The dataset comprises 1600 grayscale images sourced from platforms such as Google Street View and data collected by ARAN vehicles. Each image has a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels and contains only one type of crack. The cracks in the dataset are annotated into four categories: Transverse Crack, Longitudinal Crack, Alligator Crack, and Block Crack. Among these, transverse cracks are perpendicular to the road direction; longitudinal cracks run parallel to the road direction; alligator cracks, a form of fatigue cracking, are characterized by interconnected cracks forming a pattern resembling a series of irregular small polygons; block cracks are typical square or rectangular cracks that create a grid-like or block pattern on the pavement, usually caused by the expansion and contraction of the road surface due to temperature variations. The dataset is partitioned in a 6:2:2 ratio into training, validation, and test sets. Table 1 provides a detailed distribution of each crack type within the dataset.

Table 1.

Data Partition of the RCCD Dataset.

3.2. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

This study was conducted under a unified experimental platform and software environment with the following specifications: the hardware platform utilized an Intel i9-10900X CPU (base frequency 3.7 GHz), 64 GB of DDR4 RAM (frequency 3000 MHz), and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU (24 GB VRAM). The software environment consisted of the Windows 10 operating system, paired with the PyTorch 1.9.0 deep learning framework and Python 3.7.6 programming language.

The following parameter settings were adopted during model training: the Adam optimizer was used with its momentum parameters betas set to (0.5, 0.999), an initial learning rate of 0.01, a weight decay coefficient of 0.002, and a batch size of 32. The total number of training epochs was 100, and the learning rate scheduling strategy reduced the rate to one-tenth of its previous value every 20 epochs.

Although the images in the RCCD dataset are grayscale in content, they were converted into three-channel RGB format during preprocessing to serve as model input. Input images were resized to 256 × 256 pixels and normalized using the mean and standard deviation from the ImageNet dataset. It is noteworthy that, in order to purely evaluate the capability of the model architecture itself, no data augmentation techniques were employed in this experiment.

Given the relatively compact scale of the RCCD dataset, to ensure the statistical reliability of the experimental results and mitigate the impact of a single run’s randomness, all reported performance metrics (Precision, Recall, F1-score, etc.) are the average values obtained from 5 independent experimental runs. The corresponding standard deviations are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison of Different Models on Pavement Crack Classification.

Given the highly lightweight design of the model, a single complete training run of 100 epochs on this setup takes only approximately 5 min. The total time required for the comprehensive evaluation involving 5 independent runs was approximately 25 min, underscoring the exceptional training efficiency of our approach.

3.3. Performance Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the crack classification performance in this study, four fundamental metrics are adopted: Precision (Pr), Recall (Re), F1-score, and Accuracy (Acc). Among them, the F1-score and Accuracy provide a more comprehensive reflection of the model’s performance and thus serve as the primary basis for evaluation.

Taking the transverse crack category as an example, the sample classification in performance evaluation is defined as follow: (1) Samples where a genuine transverse crack is correctly predicted as a transverse crack are True Positives (TP); (2) Samples where other types of cracks are incorrectly predicted as transverse cracks are False Positives (FP); (3) Samples where a genuine transverse crack is incorrectly predicted as another type are False Negatives (FN).

Based on the above definitions, the Precision (Pr), Recall (Re), and F1-score for a specific category are calculated using the following formulas:

3.4. Experimental Results

3.4.1. Model Comparison Experiments

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed ASPCCNet model, this section compares it with thirteen classical and state-of-the-art deep learning models, including VGG16BN, ResNet18, the MobileNetV3 series, and the ShuffleNetV2 series, and the recent lightweight Transformer model MobileViTv2 [40]. These models cover a diverse range of architectures, from traditional deep models to modern lightweight CNNs and Transformers, ensuring good representativeness. All experiments were conducted under identical conditions—the same hardware and software environment, training dataset, data augmentation strategies, and test set (RCCD)—to guarantee the fairness of the comparison. As detailed in Section 3.2, all results are the mean of 5 independent runs to ensure robustness.

Table 2 lists the detailed performance metrics of each model on the test set. It can be observed that ASPCCNet achieves optimal or highly competitive performance across all key metrics, which is specifically demonstrated in the following four aspects:

- Superior Classification Performance: ASPCCNet ranks first in Accuracy (Acc), Precision (Pr), Recall (Re), and F1-score. Its F1-score reaches 0.816, which is significantly higher than other lightweight models. It is noteworthy that the recently introduced MobileViTv2_0.5 achieves a competitive F1-score of 0.794, yet our ASPCCNet still maintains a clear advantage of 2.8 percentage points. This indicates that the adopted AugShuffle + PConv fundamental building block combined with the CPCA attention mechanism effectively enhances the model’s feature representation capability and classification accuracy.

- Exceptional Parameter Efficiency: The parameter count of ASPCCNet is merely 0.294 M, significantly lower than that of traditional and Transformer-based models. It holds a distinct advantage even against other lightweight models, with a parameter count of only 20.3% compared to MobileNetV3S and 24.5% compared to ShuffleNetV2_1.0, and 34.6% compared to MobileViTv2_0.5. Furthermore, it is approximately 11% lower than that of the smallest compared model, ShuffleNetV2_0.5. This demonstrates the high parameter efficiency of our overall architectural design, which effectively minimizes redundancy.

- Low Computational Cost: The computational cost of ASPCCNet is only 48.68 MFLOPs, less than 16% of that of MobileNetV3 Large and two orders of magnitude lower than that of large models like ResNet50, and, crucially, only about one-fifth (19.1%) of the cost of the similarly performing MobileViTv2_0.5 (255.25 MFLOPs). This demonstrates that the model’s structural design fully considers computational efficiency, making it suitable for edge deployment scenarios with limited computational resources.

- Fast Inference Speed and Superior Balance: The inference speed of ASPCCNet ranks among the best of all models, and it achieves an exceptional balance between speed and accuracy. On a GPU, its inference time per image is 5.00 ms. This is faster than other high-accuracy models like MobileViTv2_0.5 (8.45 ms) and EfficientNet-B0 (7.88 ms). More importantly, when compared to models with similar or even faster inference speeds, ASPCCNet’s accuracy is unrivaled. For instance, while ShuffleNetV2_0.5 (5.31 ms) has a comparable speed, its accuracy (F1-score: 0.752) is significantly lower than that of ASPCCNet (F1-score: 0.816). The advantage is even more pronounced on a CPU, which is a more relevant metric for edge devices. ASPCCNet’s CPU inference time (8.94 ms) is over four times faster than MobileViTv2_0.5 (37.09 ms) and is also superior to ShuffleNetV2_0.5 (11.67 ms). Although VGG16BN has a slightly shorter GPU inference time (2.88 ms), its enormous parameter count and computational cost make it unsuitable for edge deployment. This collectively indicates that ASPCCNet achieves a superior overall balance between accuracy, speed, and efficiency.

In summary, ASPCCNet demonstrates comprehensive advantages in pavement crack image classification, exhibiting superior accuracy, exceptional parameter efficiency, low computational cost, and fast inference speed. It significantly outperforms current mainstream models and is particularly suited for practical applications demanding real-time performance and low deployment costs.

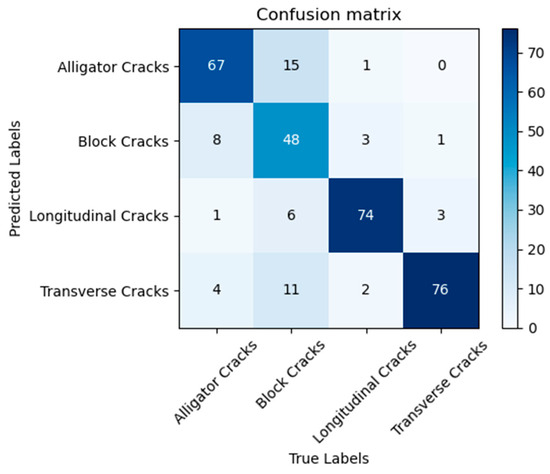

3.4.2. Misclassification Analysis

To move beyond macro-level performance metrics and gain a deeper understanding of the ASPCCNet model’s decision-making behavior and limitations, we conducted a systematic analysis of its misclassification cases. Initially, from a global perspective of error distribution, the confusion matrix (Figure 6) reveals a distinct pattern: the model’s errors are not random but are highly concentrated among specific classes. The most prominent issues are the mutual confusion between ‘Alligator Cracks’ and ‘Block Cracks’, and the misclassification of ‘Block Cracks’ as ‘Transverse Cracks’. The error rates for these confusions are significantly higher than for other class pairs, strongly suggesting that inter-class morphological similarity and the influence of dominant local features are primary sources of discrimination difficulty for the model.

Figure 6.

Confusion Matrix of ASPCCNet on the RCCD Test Set.

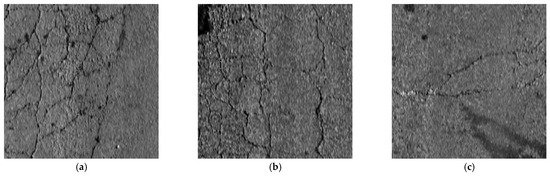

To intuitively understand the specific reasons behind these statistical patterns, we further visualized and examined typical individual cases. Figure 7 presents several representative misclassified samples. By scrutinizing these specific instances, we can pinpoint the model’s failure modes more precisely. For instance, in Figure 7a, a sample with the true label ‘Block Crack’ is misclassified as an ‘Alligator Crack’; observation reveals that the cracks in this image form an unusually regular grid-like pattern, diminishing its characteristic irregularity. Another case (Figure 7b) shows the opposite situation, where an ‘Alligator Crack’ is misclassified as a ‘Block Crack’ due to the dense and irregular distribution of its cracks. Furthermore, the ‘Block Crack’ in Figure 7c is misclassified as a ‘Transverse Crack’ (a case directly corresponding to the aforementioned statistical finding), because a sequence of linear cracks in one direction is overly prominent and continuous, causing the model to overlook the intersecting structure essential for identifying a mesh-like crack. These specific cases indicate that when strong local features in an image highly align with the typical characteristics of one category, the model exhibits insufficiency in integrating global contextual information, leading to decisions based on partial evidence.

Figure 7.

Visualization and Analysis of Typical Misclassification Cases. (a) Block Crack misclassified as Alligator; (b) Alligator Crack misclassified as Block; (c) Block Crack misclassified as Transverse.

In conclusion, the errors of our model primarily stem from the challenge of distinguishing between morphologically similar cracks and being misled by dominant local features in complex contexts. Future work could focus on enhancing the model’s comprehension of global context and its perception of fine-grained morphological differences.

3.5. Ablation Studies

To validate the effectiveness of the core components proposed in the ASPCCNet, we conducted a systematic series of ablation studies. The experiments primarily focused on four aspects: the progressive improvement of the fundamental building block, the selection of the weight decay coefficient, the optimization of the channel split ratio, and a comparison of different attention mechanisms.

3.5.1. Effectiveness of Progressive Improvements to the Basic Building Block

This study evaluated the effectiveness of the progressive improvement strategy for the basic building block. Using the original Shuffle Block as the baseline, the PConv and AugShuffle modules were introduced sequentially. The experimental results are presented in Table 3, leading to the following conclusions:

Table 3.

Effect of Basic Building Block Designs on Model Performance.

- Performance Enhancement of PConv: Introducing PConv into the baseline model, despite resulting in minor increases in parameter count and computational cost (4.1% and 3.3%, respectively), improved the F1-score by 1.6%. This indicates that PConv, via its more efficient convolutional operation, can significantly enhance the model’s feature extraction capability at a controllable computational cost.

- Optimization and Efficacy of AugShuffle: Introducing the AugShuffle module alone improved model performance (a 1.7% increase in F1-score) while simultaneously reducing model complexity, with parameter count and computational cost decreasing by 4.1% and 3.7%, respectively. This verifies the effectiveness of its tunable channel splitting and intermediate interaction mechanism in optimizing feature flow and streamlining the model architecture.

- Synergistic Effect of Module Combination: The integration of AugShuffle and PConv yielded the maximum performance improvement, achieving an F1-score of 0.808, which constitutes a 4.5% gain over the baseline. Furthermore, the complexity of the complete module was further optimized, with parameter count and computational cost reduced by 2.0% and 1.8%, respectively. This demonstrates a powerful synergy between the two components: AugShuffle macroscopically optimizes information flow and reduces redundancy, while PConv microscopically enhances spatial feature extraction through its refined convolution. Ultimately, this integration improves accuracy while reducing model complexity.

3.5.2. Analysis of Weight Decay Coefficient Optimization

The weight decay (L2 regularization) coefficient significantly influences the model’s generalization ability. To determine its optimal value, an ablation experiment was conducted, and the results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effect of L2 Regularization Coefficients on Model Performance.

The experimental results indicate that the model achieves its best performance across all evaluation metrics when the weight decay coefficient is set to 0.002. When the coefficient is too low (0.001), all metrics show a significant decline, suggesting that the model suffers from overfitting due to insufficient regularization constraints. Conversely, when the coefficient is too high (≥0.003), performance also exhibits a systematic degradation, as excessive regularization overly constrains the model capacity, leading to underfitting. In conclusion, 0.002 is identified as the ideal weight decay coefficient for this task and was consequently applied to all subsequent experiments in this study.

3.5.3. Analysis of Channel Split Ratio

The channel split ratio (split_ratio) within the AugShuffle Block is a critical hyperparameter for balancing the model’s feature extraction capability against its complexity. To identify its optimal value, an ablation study was designed, with the results detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Effect of Channel Split Ratios on Model Performance.

The experiment revealed that the model achieves optimal performance when the split_ratio is set to 9/24, yielding an F1-score of 0.808 and an accuracy of 0.809. This represents the best balance between feature utilization and model complexity. When the ratio is too small (e.g., 6/24), the model’s performance is limited by insufficient cross-path feature interaction. Conversely, when the ratio is too large (e.g., 10/24), the increase in model complexity does not translate into performance gains; instead, accuracy declines due to parameter redundancy and constrained capacity in the effective feature extraction path. In summary, a ratio of 9/24 achieves the optimal balance between performance and complexity, and its effectiveness validates the design principle of employing a tunable channel splitting mechanism.

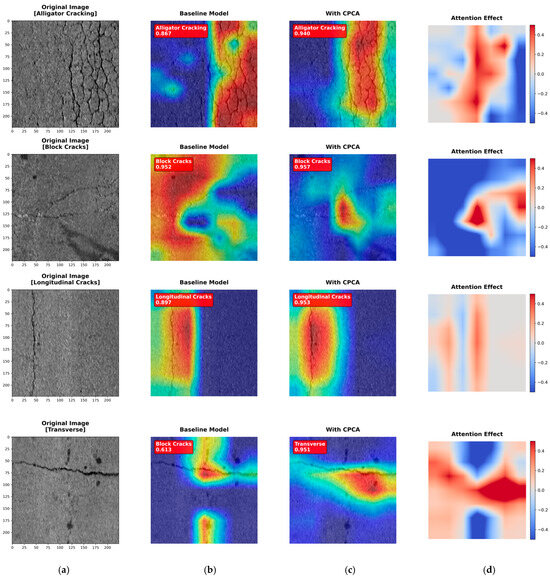

3.5.4. Comparative Analysis of Attention Mechanisms

To evaluate the proposed CPCA attention mechanism, we compared it against seven mainstream attention methods. The results (Table 6) demonstrate that CPCA achieves the highest accuracy while maintaining excellent computational efficiency.

Table 6.

Effect of Various Attention Mechanisms on Model Performance.

Specific data shows that CPCA ranks first in both F1-score (0.816) and Accuracy (0.818). Compared to other mechanisms with similar performance, such as CBAM and CAA, CPCA attains this leading performance while achieving a shorter inference time (5.00 ms), reflecting its superior design efficiency.

To move beyond numerical metrics and provide visual, intuitive validation of the CPCA mechanism’s effectiveness, we supplemented our analysis with Grad-CAM visualizations, as shown in Figure 8. By comparing the heatmaps in column (b) (without attention) with those in column (c) (equipped with CPCA), a clear observation can be made: in the absence of attention guidance, the model’s feature responses are more diffuse and can even incorrectly focus on background textures unrelated to cracks (e.g., gravel, shadows). In contrast, guided by CPCA, the model’s focus becomes more precise and concentrated, closely adhering to the main body of the crack structures. This enhanced concentration on critical discriminative regions, coupled with the effective suppression of background interference, offers an intuitive explanation for why CPCA stands out among various attention mechanisms and contributes the most significant performance gain.

Figure 8.

Visual Comparison for the Effectiveness of the CPCA Attention Mechanism. A comparison of heatmaps generated by Grad-CAM, showing the focus areas of different models on the same input image: (a) Original input image; (b) Baseline model without any attention mechanism; (c) ASPCCNet integrated with the CPCA attention mechanism; (d) Attention effect. It demonstrates that CPCA effectively guides the model to focus more precisely on the main crack structures.

The superior performance of CPCA can be attributed to its core design philosophy, which is guided by the principle of symmetry. The use of symmetric pooling paths (global average and max pooling) ensures a balanced and comprehensive channel-wise context, while the symmetrically parallel multi-scale convolutions in its spatial component enable an unbiased capture of diverse crack morphologies. This symmetry-aware architecture is key to its robust and efficient feature refinement.

In conclusion, CPCA successfully achieves the optimal balance between accuracy and efficiency, improving the F1-score by 1.0% at a minimal cost of only approximately 0.13 ms in inference time. This result validates its effectiveness as a high-performance, lightweight attention module.

4. Conclusions

This paper presented ASPCCNet, a lightweight convolutional neural network designed to resolve the accuracy–efficiency trade-off in pavement crack classification. The network introduces a core AugShuffleBlock that integrates PConv, AugShuffle, and CPCA mechanisms to achieve efficient multi-scale feature fusion. Rigorous evaluation on the RCCD dataset confirms that ASPCCNet surpasses mainstream models across key metrics: classification accuracy, parameter count, computational complexity, and inference speed, demonstrating superior overall performance.

The main contributions of this paper are threefold:

(1) The construction of ASPCCNet: a high-performance lightweight network for crack classification. Through an optimized stacking strategy of ShuffleNetV2 blocks, it achieves leading accuracy (F1-score: 0.816) with an extremely compact design (0.294 M parameters), significantly outperforming existing models.

(2) The design of the novel AugShuffleBlock: a core module that integrates PConv, AugShuffle, and CPCA to enable efficient feature extraction and fusion. Ablation studies verify that this design not only boosts accuracy but also reduces model complexity and computational cost.

(3) A comprehensive empirical validation: comprising comparisons with state-of-the-art models and extensive ablation studies on module effectiveness, channel split ratio, and attention mechanisms. These experiments identify optimal hyperparameter configurations and offer valuable insights for future lightweight model design.

Beyond these technical contributions, this work highlights the broader value of a symmetry-informed perspective in neural architecture design. The core AugShuffleBlock, with its balance of symmetric structure and controlled asymmetry, along with the CPCA mechanism and its integration of symmetric channel pooling and parallel-symmetric spatial convolutions, demonstrates how principles of symmetry can guide the creation of more powerful and efficient models.

Despite the strong performance demonstrated, this study is not without limitations. The primary limitation lies in the evaluation of a single benchmark dataset (RCCD). Consequently, the model’s robustness and generalization capability across diverse real-world scenarios require further confirmation through large-scale cross-dataset validation on other mainstream crack datasets (e.g., Crack500, AEL).

Future research will, therefore, focus on two key avenues to enhance the model’s practicality. First, as a top priority, we will perform comprehensive cross-dataset and cross-scenario generalization testing to thoroughly assess the model’s universality and stability. Second, building on the algorithmic efficiency proven here, we will advance the model’s deployment on real-world edge computing platforms. This entails comprehensive performance and power consumption benchmarking on devices like UAVs to quantify their impact on battery life and model loading time, providing a complete cost-to-performance reference for final engineering applications. Furthermore, we plan to explore multi-modal data fusion (e.g., with infrared or 3D data) and extend the application of symmetry principles to other network components.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Y. and S.G.; methodology, G.Y.; software, G.Y., X.Z. and S.C.; validation, X.W., X.Z. and S.C.; formal analysis, G.Y. and X.Z.; investigation, G.Y. and S.G.; resources, G.Y. and X.W.; data curation, X.W. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Y.; writing—review and editing, G.Y.; visualization, X.Z. and S.C.; supervision, S.G.; project administration, S.G.; funding acquisition, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hubei Provincial Key R&D Program of China, grant number 2024BAB110.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Github at https://github.com/tjboise/RCCD, accessed on 10 June 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gavilán, M.; Balcones, D.; Marcos, O.; Llorca, D.F.; Sotelo, M.A.; Parra, I.; Ocaña, M.; Aliseda, P.; Yarza, P.; Amírola, A. Adaptive Road Crack Detection System by Pavement Classification. Sensors 2011, 11, 9628–9657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, C.X.; Wang, H.N. Automatic Pavement Crack Detection Using Texture and Shape Descriptors. IETE Tech. Rev. 2010, 27, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Hou, X.D.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y. Automation Recognition of Pavement Surface Distress Based on Support Vector Machine. In Proceedings of the 2009 Second International Conference on Intelligent Networks and Intelligent Systems, Tianjin, China, 1–3 November 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.S.; O’Neill, W.A.; Cheng, H.D. Pavement Distress Classification Using Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, San Antonio, TX, USA, 2–5 October 1994; pp. 397–401. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.J.; Lee, H.D. Position-Invariant Neural Network for Digital Pavement Crack Analysis. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2004, 19, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseko, M.S.; Ritchie, S.G. A Neural Network-Based Methodology for Pavement Crack Detection and Classification. Transp. Res. Part C 1993, 1, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.D.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.G.; Glazier, C.; Shi, X.J. Novel Approach to Pavement Cracking Detection Based on Neural Network. Transp. Res. Rec. 2001, 1759, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.G.; Kim, J.H. Intelligent Crack Detecting Algorithm on the Concrete Crack Image Using Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 28th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29 June–2 July 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadas Nejad, F.; Zakeri, H. A Comparison of Multi-Resolution Methods for Detection and Isolation of Pavement Distress. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 2857–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, M.; Schoefs, F.; Ghosh, B.; Pakrashi, V. Texture Analysis Based Damage Detection of Ageing Infrastructural Elements. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2013, 28, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Qader, I.; Pashaie-Rad, S.; Abudayyeh, O.; Yehia, S. PCA-Based Algorithm for Unsupervised Bridge Crack Detection. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2006, 37, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cord, A.; Chambon, S. Automatic Road Defect Detection by Textural Pattern Recognition Based on AdaBoost. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2012, 27, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Cui, L.; Qi, Z.; Meng, F.; Chen, Z. Automatic Road Crack Detection Using Random Structured Forests. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 3434–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Li, Z.; Yao, L. Images Crack Detection Technology Based on Improved K-means Algorithm. J. Multimed. 2014, 9, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Correia, P.L. Automatic Road Crack Detection and Characterization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2013, 14, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Hoai, M.; Samaras, D. Large-scale Continual Road Inspection: Visual Infrastructure Assessment in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 2017 British Machine Vision Conference, London, UK, 4–7 September 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, K.; Khaitan, S.K.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks with Transfer Learning for Computer Vision-Based Data-Driven Pavement Distress Detection. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 157, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.D.; Zhu, Y.J. Road Crack Detection Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, L.; Peel, H.; Luo, S.; Hogg, D.; Fuentes, R. Deeper Networks for Pavement Crack Detection. In Proceedings of the 34th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Taipei, Taiwan, 28 June–1 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.H.; Le, T.H.; Perry, S.; Li, H.; Tran, T.T. Pavement Crack Detection Using Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology, Danang, Vietnam, 6–7 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbach, M.; Stricker, R.; Seichter, D.; Amende, K.; Debes, K.; Sesselmann, M.; Ebersbach, D.; Stoeckert, U.; Gross, H.M. How to Get Pavement Distress Detection Ready for Deep Learning? A Systematic Approach. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Anchorage, AK, USA, 14–19 May 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.J.; Choi, W.; Büyüköztürk, O. Deep Learning-Based Crack Damage Detection Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2017, 32, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorafshan, S.; Thomas, R.J.; Maguire, M. Comparison of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks and Edge Detectors for Image-Based Crack Detection in Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 1031–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Cho, S. Automated Vision-Based Detection of Cracks on Concrete Surfaces Using a Deep Learning Technique. Sensors 2018, 18, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, B.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Yang, G.; Xiao, J. A Robotic System Towards Concrete Structure Spalling and Crack Database. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Macau, China, 5–8 December 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.R.L.d.; Lucena, D.S.d. Concrete Cracks Detection Based on Deep Learning Image Classification. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Experimental Mechanics, Brussels, Belgium, 1–5 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.U.; Hossain, M.S.; Alam, M.J.; Andersson, K. An Integrated CNN-RNN Framework to Assess Road Crack. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 18–20 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, V.; Uong, L.; Adu-Gyamfi, Y. Automated Road Crack Detection Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Seattle, WA, USA, 10–13 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Li, L.; Gu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Lim, J.-H. A Novel Hybrid Approach for Crack Detection. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 107, 107474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Song, Y.; Yang, A.; Lv, K.; Jiang, H.; Dong, C. Accurate Classification of Tunnel Lining Cracks Using Lightweight ShuffleNetV2-1.0-SE Model with DCGAN-Based Data Augmentation and Transfer Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yao, H.; Fu, J.; Tai, N.C. The Classification and Localization of Crack Using Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network With CBAM. Eng. Struct. 2023, 275, 115854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Liu, Y.F.; Li, B.L.; Tang, L.; Fan, J.S. Automated Subway Tunnel Lining Crack Classification and Detection Based On Two-Step Sequential Convolutional Neural Network. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 15, 1765–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoni, A.L.C.; Souza, A.M.; Novo, M.S. Automated Hyperparameter Tuning for Crack Image Classification with Deep Learning. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 18247–18262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Dai, W.; Tao, J.; Qu, J.; Zhu, L.; Jin, Q. An improved transformer-based concrete crack classification method. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yue, Q.; Liu, X. Crack Image Classification And Information Extraction In Steel Bridges Using Multimodal Large Language Models. Autom. Constr. 2025, 171, 105850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.H.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L. AugShuffleNet: Communicate More, Compute Less. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.06589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zou, Y.; Lu, M.; Chen, C.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yan, F. Channel Prior Convolutional Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 178, 108784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Lu, Y. Benchmark Study on a Novel Online Dataset for Standard Evaluation of Deep Learning-based Pavement Cracks Classification Models. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. Separable Self-attention for Mobile Vision Transformers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.02680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).