Abstract

This paper proposes an event-triggered distributed switching strategy, which solves the consensus problem of switching multi-agent systems. By introducing an event-triggering mechanism, the exchange signals of each agent are updated only at discrete trigger moments, thereby reducing communication and computing loads. The design of the trigger conditions takes into account the error between the follower and its neighbor states to ensure consensus is reached. By constructing multiple Lyapunov functions and using loop functions related to event triggering, the conservativeness of multiple Lyapunov function methods is relaxed. It is shown that the closed-loop system achieves exponential leader—follower consensus even when all subsystems are unstable, while strictly excluding Zeno behavior. Numerical simulations verify the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Keywords:

event-triggered control; multi-agent systems; leader–follower consensus; switching law; looped-functional MSC:

93A16; 93C65

1. Introduction

Cooperative control of multi-agent systems (MASs) has flourished in recent decades, with applications spanning various domains such as formation control [1], intelligent transportation [2], networked estimation [3], cooperative guidance of multiple missiles [4], and distributed optimization [5]. Among cooperative control problems, the consensus problem is one of the most extensively studied and widely applied coordination issues. The consensus control refers to designing appropriate protocols for each agent so that, using only information exchanged with neighbors, all agent states eventually reach a common value. For MASs with single-integrator dynamics, seminal works provided sufficient conditions for achieving consensus under both directed and undirected graphs [6]. Consensus of second-order integrator MASs was studied in [7], which proposed a protocol design and analysis strategy enabling agreement in both position and velocity. Consensus problems with switching network topologies have also been addressed. For instance, ref. [8] considered switching communication graphs that are not strongly connected at every instant; by utilizing graph-theoretic tools and relative state information, joint connectivity conditions ensuring consensus were derived.

In the consensus research of multi-agent systems, traditional control protocols usually take the continuous communication between agents as a prerequisite. However, in practical applications, the limitations of network bandwidth and the constraints of equipment resources make this continuous communication mechanism not only lead to high control costs, but also may cause the system to be unsustainable due to excessive energy consumption. To break through this technical bottleneck, scholars have begun to focus on the optimized design of communication mechanisms, striving to enhance resource utilization efficiency while maintaining system stability. The classic periodic sampling control method [9,10] converts continuous signal transmission into periodic data exchange by introducing discrete-time communication mechanisms. However, due to the lack of attention to the dynamic changes of the agent itself, the designed periodic sampling control is often conservative [11,12], but determining the optimal sampling rate to ensure stability and performance remains challenging. An excessively long sampling interval may reduce performance, while an excessively high sampling rate can lead to unnecessary transmission and frequent controller updates, thereby lowering efficiency. To save resources, reduce controller updates and avoid unnecessary information transmission during the control process, a method that forces agents to perform “on demand” has been proposed, namely event-triggered control [13]. Among them, the control signal is updated only when specific trigger conditions are met. This method significantly reduces the communication burden by avoiding continuous or periodic communication.

In the research of multi-agent cooperative control problems, the consistency process relies on the information interaction among agents. Traditional distributed control is usually based on the assumption that the communication network among all agents is ideal. However, due to the limited network resources in practical applications, ideal network communication is clearly not feasible [14,15], especially in complex applications such as multi-agent systems. For instance, in wireless communication, signals may be interfered with by factors such as electromagnetic interference, leading to a decline in communication quality and resulting in data loss or delay. These actual existing limiting factors severely restrict the performance of multi-agent systems in real environments, making traditional control methods based on the assumption of ideal communication difficult to apply directly. In recent years, event-driven control has been introduced into the research of multi-agent systems, providing new ideas for solving the problem of cooperative control in resource-constrained environments and achieving remarkable results. For instance, reference [16] proposed a novel distributed event-driven mechanism, which only requires the discrete state information of neighboring nodes to achieve consistent control of multi-agent systems under fixed and switched topologies. Reference [17] extends the event-driven control strategy to nonlinear multi-agent systems, deduces the sufficient conditions for achieving consistency in this system, and provides a theoretical tool for solving the cooperative control problem of random disturbances. For the situation where communication resources are limited, reference [18] proposed a hybrid driving mechanism of continuous event-driven mechanism and time-driven mechanism, achieving leader-following consistency in stochastic multi-agent systems. The static event-driven mechanism significantly enhances the resource utilization efficiency of multi-agent systems by reducing unnecessary communication and control updates, demonstrating its wide applicability and significant value in complex multi-agent systems. For multi-agent systems with external disturbances, reference [19] proposed an event-driven scheme with dynamic thresholds, which not only effectively solved the leader-follower bounded consistency problem of the system, but also significantly improved the anti-interference ability of the system.

Recently, scaled consensus problems for hybrid multi-agent systems have also attracted considerable attention. In [20], Donganont studied scaled consensus of hybrid MASs via impulsive protocols, where continuous-time and discrete-time agents are coordinated under a common impulsive framework. In a related work, Donganont [21] further developed finite-time leader–following scaled consensus strategies, providing conditions under which the followers track a scaled version of the leader in finite time. Closely related to edge-based coordination, Park et al. [22] investigated scaled edge consensus in hybrid MASs, where the inter-agent couplings are designed such that the edge states achieve scaled agreement under pulse-type communication. These results highlight the usefulness of hybrid and scaled consensus concepts under impulsive or pulse-modulated protocols. In contrast, the present paper focuses on unscaled leader–follower consensus for purely continuous-time switched MASs, and combines an event-triggered communication mechanism with a looped-functional-based switching law design.

It should be pointed out that in all the above results, the dynamics of the agent remain unchanged. In fact, many natural systems and artificial systems contain dynamic behaviors with different patterns. Take the street network as an example. The street network is a system composed of roads and traffic lights in a specific area, with the traffic lights switching between different colors. Therefore, introducing the switching mechanism into multi-agent systems is of extremely significant importance. To achieve this goal, we need to combine the concept of switching systems with the characteristics of multi-agent systems.

Reference [23] addresses the COR problem in switched multi-agent systems with input saturation by proposing sufficient conditions derived from a distributed control scheme. Meanwhile, the consensus problem for uncertain switched MASs with delays under a fixed directed topology is examined in [24]. References [25,26] designed a new switching law for switching systems based on event triggering and state dependence. However, the design of the switching signal in reference [25] led to a mismatch in the dynamic responses between the subsystem and the controller, resulting in asynchronous switching. However, the new switching law designed in reference [26] does not exhibit asynchronous behavior. Reference [27] designed a switching law dependent on agents, allowing all subsystems of each agent to be non-stabilizing, ensuring the necessary and sufficient conditions for the collaborative output regulation problem of switching multi-agent systems. However, the involved switching law cannot guarantee the length of the switching time interval and may trigger Zeno behavior. Therefore, references [28,29] designed a fully distributed integral event-triggering mechanism and an agent-dependent switching law with residency time constraints, ensuring that the positive lower bound of the adjacent switching time intervals of each agent is guaranteed and avoiding Zeno behavior.

Building upon the above insights, the primary goal of this paper is to develop a distributed event-triggered control and agent-dependent switching framework that guarantees leader–follower consensus for switched multi-agent systems while rigorously excluding Zeno behavior, even when all subsystem dynamics are unstable. The main conclusions show that, under the proposed scheme, each follower can exponentially track the leader despite switching among unstable modes, and that positive lower bounds on inter-event times can be explicitly established for all agents and modes, thereby ensuring Zeno-free operation and a substantial reduction of communication and computation load.

- (i)

- We design a distributed event-triggered consensus scheme for leader–follower-switched MASs in which all subsystems may be unstable. In contrast to [16,28,29], which mainly focus on cooperative output regulation and often rely on stabilizable subsystems, our framework explicitly handles unstable agent dynamics while still guaranteeing consensus.

- (ii)

- We develop a state-dependent switching law that is only updated at event-triggered instants. Different from the average-dwell-time-based switching laws in [23,28] and the joint triggering strategies in [25,26], the proposed law requires only intermittent detection at trigger times, thereby reducing continuous monitoring and avoiding the asynchronous switching issues reported in [25].

- (iii)

- We construct a two-sided looped Lyapunov–Krasovskii functional tailored to the event-triggered setting. This function removes the temporary increase of Lyapunov functions during the mismatched intervals between the minimal switching and triggering instants, thus relaxing the conservatism of standard multiple-Lyapunov-function approaches and providing tractable LMI conditions for leader–follower consensus under the proposed event-triggered switching scheme.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews basic graph-theoretic notions and formulates the leader–follower consensus problem for switched multi-agent systems. Section 3 presents the proposed prediction-based event-triggered control law and agent-dependent switching strategy and establishes Zeno-free properties and consensus conditions via a two-sided looped Lyapunov–Krasovskii functional and associated LMIs. Section 4 provides numerical examples that illustrate the performance of the proposed scheme and verify the theoretical results. Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses possible directions for future research.

2. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

2.1. Graph Theory Preliminaries

The communication topology among the agents is modeled by a weighted digraph , where represents the set of follower agents, and is the set of directed edges. An edge indicates that agent i can receive information from agent j. The neighbor set of node i is .

Let denote the adjacency matrix of , defined by if and otherwise. The in-degree of node i is , and is the in-degree matrix. The Laplacian of the graph is . To incorporate a leader (denoted node 0), we consider an augmented graph obtained by adding node 0 to . The leader-to-follower influence is described by : we set if follower i can receive information from the leader, and otherwise. Let . We define the augmented Laplacian as

In this paper, we assume the following about the communication topology:

Assumption 1

([29]). The follower graph among the N followers is undirected and connected. Moreover, the augmented leader–follower graph obtained by adding the leader node 0 admits a directed spanning tree rooted at the leader. Equivalently, the pinned Laplacian is positive definite.

It is worth noting that the connectivity level of the communication graph has a direct impact on both the efficiency and the performance of the overall system. Intuitively, stronger connectivity leads to faster information diffusion and hence faster consensus, but it requires more communication links and a higher communication burden. Conversely, reducing connectivity decreases the communication load, but typically slows down the convergence and may make the stability conditions more conservative. In our framework, the connectivity assumptions ensure that leader–follower consensus is still guaranteed for the considered graphs, while the event-triggered mechanism is designed to reduce the effective communication load without changing the underlying topology.

2.2. Problem Formulation

We consider a leader–follower MAS consisting of one leader and N followers (). The agents’ dynamics switch among multiple modes governed by a common switching signal . The leader, which provides a reference trajectory, follows:

and each follower i has the following dynamics:

where are the leader and follower state vectors, respectively; is the control input for follower i. For each mode j in the set , and are the state and input matrices of that subsystem. The switching signal is a piecewise constant function characterized by a sequence of switching instants : we write for , meaning the -th subsystem is active on that interval. We assume that switching instants have no finite accumulation points (i.e., a positive minimum dwell-time exists), and no state jumps occur at switching times.

The control objective is to design a distributed control law and a state-dependent switching law , updated only at event-triggered instants, such that the switched MAS achieves leader–follower consensus.

Definition 1

([30]). The switched MAS is said to achieve leader-follower consensus if, for any initial states and for all agents , the designed control inputs guarantee that

In other words, each follower’s state asymptotically converges to the leader’s state.

Remark 1.

The above definition follows the standard asymptotic notion of leader–follower consensus, that is, the tracking errors converge to zero as time goes to infinity. In the main results below, we will in fact derive stronger sufficient conditions ensuring that this convergence is exponential under the proposed event-triggered switching scheme.

3. Main Results

3.1. Event-Triggered Control and Switching Law Design

Our distributed control framework consists of three key components: (i) state prediction and estimation error, (ii) the control protocol, and (iii) an event-triggered mechanism that determines when to transmit and switch. These are detailed as follows.

Each follower i employs a state predictor between events. Let be the sequence of event times for agent i, with . On each interval , follower i predicts its state using the last sampled state at . Specifically,

is the predicted state (an open-loop estimate assuming no further input updates). The prediction error is defined as

which is reset to zero at each event and grows when no new information is received about agent i’s true state.

We propose the following control input for follower i:

where is the mode-dependent state-feedback gain matrix associated with the active subsystem , i.e., whenever . For each mode , the gain is designed off-line by solving the LMI-based synthesis conditions in Theorem 3, where matrices and satisfying (33) are first computed and then is recovered. In this way, the closed-loop disagreement dynamics are exponentially stable, and the gains determine the decay rate and damping of the followers’ responses.

The vector inside the brackets in (5) collects the relative state information available to follower i, namely the differences between its predicted state and the predicted states of its neighbors , together with the leader–follower mismatch (we assume that the leader broadcasts its state to its neighbors at event times, so that ). Physically, scales this aggregated relative information into the actual control input , thereby shaping how strongly each follower reacts to the discrepancies with its neighbors and the leader. With this structure, the control law remains fully distributed, because agent i only requires information from its immediate neighbors.

Each follower i decides its next transmission (and switching) instant by monitoring an event-triggering function that measures the difference between its state and its neighbors’ states. Specifically, starting from an event time , the -th event time is defined as follows:

the first time t after that becomes non-negative.

We design the trigger function as follows:

where is a design parameter (trigger threshold). In words, agent i triggers an event when the norm of its prediction error grows large relative to a weighted norm of its neighbors’ relative state discrepancies. Prior to the threshold being reached, we have , meaning of the neighbor difference term; this condition will be used to ensure stability and exclude Zeno behavior.

Building on this event-triggered framework, we now design a state-dependent switching law based on a common switching signal . Let denote the ordered sequence of global event instants, i.e., the union of all local event times . At each the active mode is updated as

and remains constant for all . In other words, all agents share the same mode , while the switching instants are determined in a distributed manner by the local event-triggering conditions.

Remark 2.

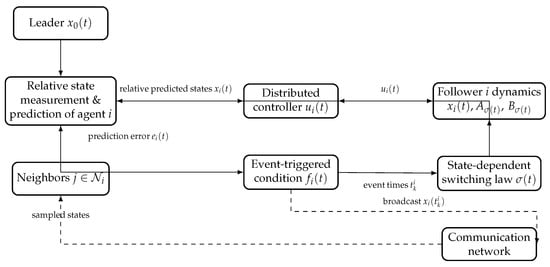

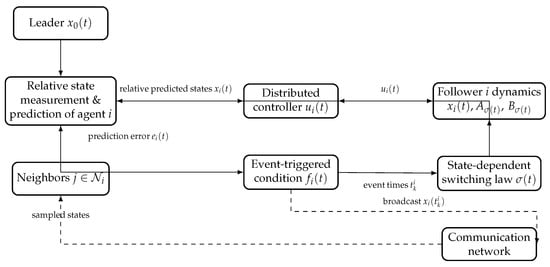

In Figure 1, the block “Relative state measurement & prediction of agent i” corresponds to the predictor and the prediction error defined in (4), whereas the block “Distributed controller” implements the control input given by (5). The block “Event-triggered condition ” realizes the triggering rule (6) and generates the local event instants . At each global event time , the block “State-dependent switching law ” updates the mode according to (8), and the updated mode is shared by both the follower dynamics and the distributed controller. The dashed arrows represent the communication network, which is only used at event times to broadcast the sampled states to neighboring agents.

Figure 1.

Configuration of the proposed prediction-based event-triggered switching scheme for a generic follower i.

Remark 3.

Conventional state-dependent switching laws often require continuous monitoring of agents’ states and frequent information broadcasts, imposing significant communication and computation burdens. In contrast, the above event-triggered switching law operates on an on-demand basis: it updates the mode only at discrete trigger times. This on-demand strategy eliminates the need for continuous state monitoring or broadcasting, reducing network usage and preventing unnecessary switching.

Remark 4.

The event-triggered switching mechanism guarantees that controller updates and subsystem switches occur simultaneously when the trigger condition is met. This inherent synchrony means the controller and plant remain matched to each other’s mode, which avoids performance degradation from asynchronous switches. In effect, by limiting switches to trigger instants and imposing a dwell-time, the strategy maintains system stability while substantially reducing the switching frequency.

Remark 5.

Our event-triggered mechanism is fully distributed in the sense that each agent uses only locally available information at triggers. Between events, no continuous communication is needed. Each agent i only requires its neighbors state information at the moments defined by (6). This significantly alleviates network traffic among agents and reduces each controller’s computational load.

With the control law (5), trigger rule (6)–(7), and switching law (8) in place, we next derive the closed-loop error dynamics and present the main theoretical results.

Let denote the tracking error of follower i relative to the leader. Stacking all follower-leader errors, define . From (1)–(2) and the control law (5), we can derive the closed-loop dynamics for . First, note that

Substituting from (5) and rearranging, we obtain:

The step from (9) to (10) uses the definitions and . One can verify that and , which yields the decomposition into -terms and e-terms above.

By collecting terms for all N followers, the overall closed-loop error dynamics can be written compactly in vector form. Using the augmented Laplacian defined earlier, we have the following:

where stacks the prediction errors of all followers. The i-th block of corresponds to agent i’s neighbors.

This section presents the design of a distributed ETS, an agent-dependent switching signal, and a corresponding control protocol. The objective is to achieve leader-following consensus for switched MASs while explicitly excluding Zeno behavior.

3.2. Exculed Zeno Behavior

Theorem 1.

Consider the closed-loop system (11) under the distributed event-triggered mechanism (6)–(7). For each follower agent i, there exists a uniform positive lower bound on its inter-event times . In particular,

for any mode l active during . Thus, no agent exhibits Zeno behavior (infinitely many triggers in finite time) under the proposed triggering law.

Proof.

Without loss of generality, consider an interval during which the network is in mode . Suppose there are q trigger instants for agent i in this interval, labeled with and . For any t in (where ), the prediction error is .

We examine the growth of on . Using the system dynamics (10), one can bound the right-hand Dini derivative of as:

At the trigger instant , we have (the error is reset to zero). Integrating the differential inequality (12) from to some t in yields:

Now, by the event-triggering condition (7), while t remains prior to the next trigger , we have . This implies the following:

Combining the above inequality with (13), for any we obtain the following:

Integrating (14) once more from to and applying Fubini’s theorem to swap integrals, we get the following:

Because the left-hand side of (15) is exactly times the square-bracketed term in (14) integrated over . To make this step precise, define the following:

The integrand in is a norm and hence nonnegative. In the nontrivial case where a new event is generated, it cannot vanish identically on , so we have for all . Inequality (15) can therefore be rewritten as follows:

Now let (the time elapsed since the last trigger). The right-hand side of (16) evaluates to . Thus (16) simplifies to

or equivalently

Solving for gives the following:

The right-hand side of (17) is a positive constant (depending on system matrices and the chosen ) and serves as a uniform lower bound for any inter-event interval of agent i while mode l is active. Importantly, this bound does not depend on or the particular trajectory, only on the system and trigger parameters.

Since the mode l was arbitrary and there are finitely many modes, we can take as the minimum of the bounds in (17) over all possible modes . is still positive, and thus every inter-event time is bounded below by . This proves that agent i cannot trigger infinitely often in any finite time interval, i.e., Zeno behavior is excluded.

Having established that trigger instants cannot accumulate, we next present conditions under which the proposed control and switching strategy guarantees convergence of all followers to the leader.

3.3. Leader–Follower Consensus Under State-Dependent Event-Triggered Switching

Theorem 2.

Consider the event-triggered switched MASs (1)–(2), Assume that for each mode there exist symmetric matrices

such that the following LMIs hold:

where and . Then the closed-loop system achieves exponential leader–follower consensus. In particular, there exist constants and such that

and hence for all . Moreover, Zeno behavior is excluded by Theorem 1.

Remark 6.

In the above LMIs, the matrix is a slack matrix introduced via the S-procedure in order to incorporate the event-triggering constraint into the Lyapunov inequality in a convex way.

More specifically, the triggering condition (see (6)–(7)) can be written in quadratic form with respect to the augmented vector as

which bounds the measurement error by the disagreement term involving . When deriving an upper bound for , a cross term of the form appears. The S-procedure allows us to combine this cross term with the above quadratic triggering inequality by adding a weighted version of the trigger matrix to the Lyapunov matrix. After completing the squares, this leads to the LMI in which the block associated with becomes instead of , with treated as an additional decision variable.

Therefore, does not represent any physical parameter of the agents; it is a design slack matrix that determines how strongly the triggering condition is used to compensate the – coupling in . Allowing to be free (subject to ) increases the degrees of freedom of the LMI and thus helps to reduce the conservatism of the resulting sufficient conditions.

Proof.

Let for . Set

so that , and .

Stack the tracking errors as and the prediction errors as . On the q-th subinterval define the following:

Let .

Note that the candidate Lyapunov functional used here is precisely the two-sided looped Lyapunov–Krasovskii functional announced in the introduction, adapted to the event-triggered setting. As a consequence, the derivative bounds and the LMIs obtained from this functional hold uniformly for all positive inter-event intervals and do not require specifying any explicit upper bound on their length. From the viewpoint of time-delay systems, each inter-event interval plays the role of a (possibly time-varying) delay in the feedback loop. The above uniformity means that the conditions in Theorem 2 are delay-range-free: once the LMIs are feasible, exponential consensus is guaranteed for all sequences that satisfy the positive lower bound implied by Theorem 1, without the need to compute a finite maximum admissible delay.

Because one of vanishes at each endpoint, we have the following:

We next compute for . Using , and the aggregated disagreement dynamics .

Define

Then

Since and the integrands are squares, ; hence

From (21), using ,

For the third term in (21), apply Young’s inequality with :

Moreover, since , we upper-bound the following:

The trigger (6)–(7) can be written as the quadratic constraint

By the S-procedure, this implies that for some nonnegative scalar multiplier (absorbed into the design),

where is a mode-dependent slack matrix introduced by the S-procedure to encode the triggering inequality and enlarge the feasible LMI region.

Introduce . Using (27) and (28), and completing squares for the -dependent part, we obtain the following:

with

Origin of the blocks: collects the symmetric part from together with the term; comes from the – cross term ; and are produced when completing squares with the terms weighted by ; is the negative weight on coming from . The trigger inequality (6)–(7) is encoded by the S-procedure, which yields the additional LMI constraint (18).

If in (18), then and hence there exists such that

Integrating over gives the interval-wise contraction

Effect of the state-dependent switch at . At the global event a subset of agents triggers. For each the rule selects minimizing at . Since is continuous, we have

i.e., V is nonincreasing at switching instants:

Theorem 1 guarantees a uniform positive inter-event lower bound, so the sequence has no finite accumulation and . By induction and using , the estimate above yields the following:

On each flow interval the derivative inequality implies , hence for all we obtain the global bound

In other words, decays to zero exponentially. Since is positive definite with respect to the stacked tracking error , this shows that converges to zero exponentially, i.e., exponentially for all . Together with Theorem 1, which guarantees a uniform positive lower bound on the inter-event times and excludes Zeno behavior, this completes the proof. □

Theorems 1 and 2 together guarantee that under the proposed event-triggered control and switching strategy, the closed-loop MAS is both Zeno-free and convergent to consensus. Even if individual agent dynamics are unstable, the cooperative design stabilizes the overall system. In the next section, we would validate these theoretical results with numerical simulations, demonstrating that all followers track the leader and highlighting the communication savings due to event-triggering.

3.4. State-Feedback Gains

Theorem 3.

Let be the augmented Laplacian in Section 2, and let be the set of its strictly positive eigenvalues (; for pinned leader graphs typically , for leaderless graphs ). For each mode , suppose there exist matrices

such that the following convex LMIs hold simultaneously for all :

Then, with the mode-dependent static gains

the disagreement dynamics is exponentially stable for each active mode j, with decay rate at least . Consequently, by fixing as above and solving the LMIs in Theorem 2 for , the conditions of Theorem 2 become feasible and the closed-loop event-triggered switched MAS achieves leader–follower consensus while remaining Zeno-free.

Proof.

Let T be an orthogonal matrix that diagonalizes : with . Applying the transformation , the aggregated error dynamics decouples into N blocks

For any and any , define the Lyapunov function . Then

where we used and the LMI (33). Hence each disagreement block is exponentially stable with rate , so the overall disagreement state decays exponentially whenever the mode j is active. Fixing the gains obtained above, and are constant, and Theorem 2 reduces to a convex feasibility problem in the auxiliary variables ; feasibility ensures the quadratic upper bound (25) is negative definite on flows while the S-procedure captures the trigger, yielding consensus and Zeno exclusion as claimed. □

Remark 7

(Common gain option). If a common feedback gain is desired, set and for all j. Then solve

for variables , and set . This yields a single K robust to all modes and all positive Laplacian eigenvalues, at the price of extra conservatism.

4. Numerical Example

4.1. Example 1

For a switching multi-agent system consisting of one leader and four followers, each agent has two distinct operating modes with the following system matrices, and whose communication topology is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example 1: communication topology of the leader–follower multi-agent system.

A straightforward eigenvalue calculation yields

so has one eigenvalue with positive real part and is therefore unstable. For the second mode, we obtain

whose real parts are all negative; hence is a Hurwitz stable matrix. In other words, Example 1 involves one unstable subsystem (mode 1) and one stable subsystem (mode 2).

The communication topology between agents is shown in Figure 1, which includes a directed spanning tree with the leader as the root, solving Theorem 2

The initial states of the leader and followers are chosen as

These particular initial states are not specially tuned to facilitate convergence; they are simply taken as distinct, nonzero vectors in so that the transient responses of the followers and their convergence toward the leader can be clearly visualized in the simulations. According to Theorem 2, once the corresponding LMIs are feasible, the proposed event-triggered scheme guarantees leader–follower consensus for arbitrary initial conditions , . For this example, we choose the parameter in the triggering condition, which yields a positive minimum inter-event interval and thus excludes Zeno behavior.

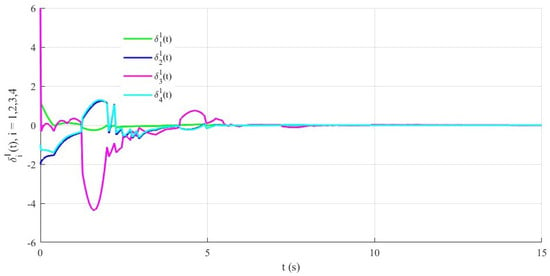

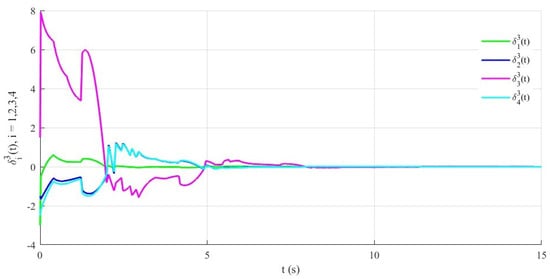

Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 depict the trajectories of the tracking error components , , for all followers. One can see that all error components converge to zero, which confirms that every follower asymptotically tracks the leader under the proposed event-triggered scheme. Figure 6 shows the switching signal of the closed-loop system, while Figure 7 illustrates the event-triggered instants of all agents. In contrast to a continuous or time-driven (periodic) communication strategy, where information would be exchanged at every sampling instant, the triggering instants in Figure 7 are relatively sparse. From a network perspective, this means that the effective connectivity of the communication graph is reduced in time, leading to a substantial decrease in the number of transmissions and thus an improvement in communication efficiency. At the same time, the convergence of the tracking errors in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 demonstrates that the closed-loop consensus performance is well preserved despite this reduced connectivity.

Figure 3.

Example 1: trajectories of the first component of the tracking errors for the four followers, where .

Figure 4.

Example 1: trajectories of the second component of the tracking errors for the four followers, where .

Figure 5.

Example 1: trajectories of the third component of the tracking errors for the four followers, where .

Figure 6.

Example 1: switching signal of the closed-loop switched multi-agent system.

Figure 7.

Example 1: event-triggered communication instants of the four followers.

To quantitatively evaluate the communication efficiency of the proposed event-triggered scheme, we compare it with a conventional periodic control strategy in Example 1. The periodic controller samples every s, resulting in updates over the s simulation horizon. In contrast, under the proposed asynchronous event-triggered mechanism, the four agents are triggered 57, 45, 69 and 36 times, respectively, yielding a total of updates and an average of per agent. As shown in Table 1, the event-triggered strategy achieves nearly the same convergence performance ( s) while reducing communication by approximately 96.6%.

Table 1.

Comparison between periodic and event-triggered update schemes in Example 1.

4.2. Example 2

Consider a pendulum system used to demonstrate the effectiveness of the switching control strategy, which consists of four followers and one leader. We use the following linearized equation of the pendulum as the ith follower:

where represents the deflection angle of the pendulum rod, denotes the control torque, and represent the length and mass of each pendulum respectively, and m/s2 is the gravitational acceleration constant. In this example, is measured in radians and denotes a small deviation around the downward equilibrium . With the chosen initial conditions we have for all , so the pendulum angles remain in a small-angle regime throughout the simulation, and the linearized model used above is valid.

The leader’s dynamics are given by the following:

Let be the state vector, then the system matrices are as follows:

where the selected parameters are kg, kg, m, m. Consider the communication topology shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Example 2: communication topology of the leader–follower pendulum network.

We obtain the controller gain:

These gains are obtained by solving the LMI-based synthesis conditions in Theorem 3, which enforce a relatively fast convergence rate for the closed-loop pendulum dynamics. For the linearized model

the gravitational term is comparatively large, whereas the input channel is scaled by . As a result, the feedback gains and must take relatively large numerical values in order to compensate the gravitational torque and shift the closed-loop eigenvalues sufficiently to the left half-plane. Nevertheless, since the pendulum angles and angular velocities are small in this example, the resulting control torques remain of moderate magnitude in the simulations.

The initial states are chosen as follows:

Figure 9 shows the switching signals of the agents. Figure 10 depicts the event-triggered instants of the agents, which excludes Zeno behavior. Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 present the trajectories of the tracking errors between the followers and the leader. From Figure 11 and Figure 12, it is clear that leader–following consensus is achieved under the proposed event-triggered switching scheme.

Figure 9.

Example 2: switching signal of the closed-loop pendulum system.

Figure 10.

Example 2: event-triggered communication instants of the four followers.

Figure 11.

Example 2: trajectories of the second component of the tracking errors for the four pendulum followers, where .

Figure 12.

Example 2: trajectories of the second component of the tracking errors for the four pendulum followers, where .

To further assess the communication efficiency and scalability of the proposed event-triggered mechanism, we also carry out a second simulation in Example 2. The simulation horizon is s. For the conventional periodic control strategy with sampling period s, this leads to control/communication updates. In contrast, under the proposed asynchronous event-triggered scheme, the four agents are triggered 33, 71, 55 and 45 times, respectively, yielding a total of updates and an average of per agent. As shown in Table 2, the event-triggered strategy achieves almost the same convergence performance as the periodic controller, while reducing the overall communication load by approximately .

Table 2.

Comparison between periodic and event-triggered update schemes in Example 2.

5. Conclusions

This paper has investigated the leader–follower consensus problem for switched multi-agent systems with dynamically changing modes under the combined action of event-triggered control and state-dependent switching signals. The proposed event-triggered mechanism not only reduces the communication and computation burden among neighboring agents, but also improves the overall performance of the system. It is rigorously proved that the designed event-triggered control scheme guarantees a strictly positive dwell time between any two consecutive triggering instants for all agents and modes, which completely excludes the Zeno phenomenon. In addition, a more general switching rule is introduced, namely a state-dependent switching signal updated only at event-triggered instants. This rule breaks through the limitations of traditional time-dependent switching laws and allows leader–follower consensus to be achieved even when all subsystems are unstable.

From a practical point of view, the numerical examples demonstrate that the proposed event-triggered leader–follower switching scheme can achieve consensus with a substantial reduction of control and communication updates when compared with a conventional periodic implementation. For the representative scenarios considered in Section 4, the total number of updates is reduced by more than ninety percent while the convergence speed remains almost unchanged. These results indicate that the proposed framework is promising for resource-limited networked control applications in which bandwidth and energy consumption are critical concerns. At the same time, the present study is subject to several constraints. The analysis is carried out for continuous-time linear multi-agent systems with known dynamics, under a fixed connected communication topology and ideal communication channels without delays, packet dropouts, or measurement noise. Moreover, only state-feedback controllers are considered, and the LMI conditions are derived for a specific class of looped Lyapunov–Krasovskii functionals. Extending the framework to nonlinear or uncertain agent dynamics, switching or time-varying topologies, output-feedback settings, and more general communication imperfections will be an interesting direction for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z., X.L. and J.S.; methodology, X.L., T.W. and H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L., T.W., H.W. and J.S.; supervision, X.L. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Qianyi Technology (Changchun) Co., Ltd. (Grant Number RES0008506).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study was funded by Qianyi Technology (Changchun) Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Oh, K.K.; Park, M.C.; Ahn, H.S. A survey of multi-agent formation control. Automatica 2015, 53, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbo, F.; Mandiau, R.; Zargayouna, M. Extended review of multi-agent solutions to Advanced Public Transportation Systems challenges. Public Transp. 2024, 16, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespanha, J.P.; Naghshtabrizi, P.; Xu, Y. A survey of recent results in networked control systems. Proc. IEEE 2007, 95, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H. Cooperative control of multi-missile systems. IET Control Theory Appl. 2015, 9, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedić, A.; Ozdaglar, A. Distributed subgradient methods for multi-agent optimization. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2009, 54, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfati-Saber, R.; Murray, R.M. Consensus problems in networks of agents with switching topology and time-delays. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 49, 1520–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Beard, R.W. Consensus seeking in multiagent systems under dynamically changing interaction topologies. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, L. Stability of multiagent systems with time-dependent communication links. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Z. Second-order consensus for multiagent systems via intermittent sampled position data control. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 50, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Jia, Y. Consensus in networked multi-agent systems via sampled control: Fixed topology case. In Proceedings of the 2009 American Control Conference, St. Louis, MO, USA, 10–12 June 2009; pp. 3902–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhou, L.; Yu, X.; Lü, J.; Lu, R. Consensus in multi-agent systems with second-order dynamics and sampled data. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2012, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Chen, T. Sampled-data consensus for multiple double integrators with arbitrary sampling. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 3230–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Årzén, K.E. A simple event-based PID controller. IFAC Proc. Vol. 1999, 32, 8687–8692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Han, Q.L.; Ge, X.; Zhang, X.M. An overview of recent advances in event-triggered consensus of multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2017, 48, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Wu, J.; Su, S.F.; Zhao, X. Neural network-based fixed-time tracking control for input-quantized nonlinear systems with actuator faults. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 3978–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, J. Distributed event-triggered consensus using only triggered information for multi-agent systems under fixed and switching topologies. IET Control Theory Appl. 2018, 12, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Shi, P.; Xiang, Z.; Shi, Y. Consensus tracking control of switched stochastic nonlinear multiagent systems via event-triggered strategy. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 31, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.L.; Deng, F.Q. Tracking control for stochastic multi-agent systems based on hybrid event-triggered mechanism. Asian J. Control 2019, 21, 2352–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Feng, J.; Xu, C.; Wang, J. Observer-based dynamic event-triggered strategies for leader-following consensus of multi-agent systems with disturbances. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 3148–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donganont, M. Scaled consensus of hybrid multi-agent systems via impulsive protocols. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2025, 36, 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Donganont, M. Leader-following finite-time scaled consensus problems in multi-agent systems. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2025, 38, 464–478. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.; Donganont, S.; Donganont, M. Achieving Edge Consensus in Hybrid Multi-Agent Systems: Scaled Dynamics and Protocol Design. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2025, 18, 5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Zhao, J. Output regulation of switched linear multi-agent systems: An agent-dependent average dwell time method. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2016, 47, 2510–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhao, J. Leader-following consensus for switched uncertain multi-agent systems with delay time under directed topology. In Proceedings of the 2023 42nd Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Tianjin, China, 24–26 July 2023; pp. 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, J. Event-triggered control for switched linear systems: A control and switching joint triggering strategy. ISA Trans. 2022, 122, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, J. Event-triggered-based switching law design for switched systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 19985–19998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, J. Distributed integral-based event-triggered scheme for cooperative output regulation of switched multi-agent systems. Inf. Sci. 2018, 457, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, J. Distributed adaptive integral-type event-triggered cooperative output regulation of switched multiagent systems by agent-dependent switching with dwell time. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2020, 30, 2550–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhao, J. Fully distributed event-triggered cooperative output regulation for switched multi-agent systems with combined switching mechanism. Inf. Sci. 2023, 638, 118970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Jiang, Z.P. Event-based leader-following consensus of multi-agent systems with input time delay. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2014, 60, 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).