Abstract

Driven by 5G/6G and the Internet of Things (IoT), wireless sensor networks (WSNs) are confronted with core challenges such as limited energy constraints, unbalanced resource allocation, and security vulnerabilities. To address these, WSNs are integrated with cognitive radio networks (CRNs) to alleviate spectrum scarcity, and reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS) are adopted to enhance performance, but traditional passive RIS suffers from “double fading” (signal path loss from transmitter to RIS and RIS to receiver), which undermines WSNs’ energy efficiency and the physical layer security (PLS) (e.g., secrecy rate, SR) of primary users (PUs) in CRNs. This study leverages symmetry to develop an active RIS framework for WSN-integrated CRNs, constructing a tripartite collaborative model where symmetric beamforming and resource allocation improve WSN connectivity, reduce energy consumption, and strengthen PLS. Specifically, three symmetry types—resource allocation symmetry, beamforming structure symmetry, and RIS reflection matrix symmetry—are formalized mathematically. These symmetries reduce the degrees of freedom in optimization (e.g., cutting precoding complexity by ~50%) and enhance the directionality of green interference, while ensuring balanced resource use for WSN nodes. The core objective is to minimize total transmit power while satisfying constraints of PU SR, secondary user (SU) quality-of-service (QoS), and PU interference temperature, achieved by converting non-convex SR constraints into solvable second-order cone (SOC) forms and using an alternating optimization algorithm to iteratively refine CBS/PBS precoding matrices and active RIS reflection matrices, with active RIS generating directional “green interference” to suppress eavesdroppers without artificial noise, avoiding redundant energy use. Simulations validate its adaptability to WSN scenarios: 50% lower transmit power than RIS-free schemes (with four CBS antennas), 37.5–40% power savings as active RIS elements increase to 60, and a 40% lower power growth slope in multi-user WSN scenarios, providing a symmetry-aided, low-power solution for secure and efficient WSN-integrated CRNs to advance intelligent WSNs.

1. Introduction

In recent years, driven by the rapid advancement of the Internet of Things (IoT), edge computing, and 5G/6G technologies, wireless sensor networks (WSNs)—a core infrastructure for smart cities, industrial internet, and intelligent transportation—have undergone a fundamental transformation: evolving from traditional “data collecting–wireless transmitting” systems to advanced “intelligent sensing–autonomous decision-making” platforms [,]. This evolution enables WSNs to support real-time monitoring of critical parameters (e.g., environmental sensing, industrial equipment status) but also introduces pressing challenges inherent to intelligent WSN development: limited energy reserves of sensor nodes, unbalanced resource allocation between communication and perception, and vulnerability to eavesdropping attacks. These issues align with the key dilemmas in intelligent WSN research—such as the joint optimization of limited energy and wide-area coverage, and the trade-off between communication efficiency and security—posing bottlenecks to the practical deployment of WSNs in high-reliability scenarios [,].

Physical layer security (PLS), which takes advantage of the randomness of wireless channels like fading, noise, and interference to enable security without using cryptographic techniques, has become very appealing for solving such problems of CRN []. It avoids the large computational complexity and latency of traditional encryption as it allows for real-time 6G applications []. But even in such cases with poor channel conditions in CRNs, PLS still cannot guarantee robust security. Take spectrum sharing for example, it may make interference worse, so the SR of PUs becomes bad and also makes the energy efficiency of the secondary network become bad [,].

RIS has been integrated into CRNs for the purpose of enhancing transmission quality and communication security. Equipped with low-cost passive reflective components, RIS is capable of dynamically regulating electromagnetic wave propagation through phase shift adjustments, thereby amplifying legitimate signals (e.g., those of primary/secondary users) while attenuating eavesdropping links that may intercept sensitive data []. In early works, it has been shown that the passive RIS in CRNs can help enhance SUs’ SE and improve PUs’ SR by generating “green interference” (low-energy directional interference generated by RIS to suppress eavesdroppers without artificial noise []) in order to hurt the wiretap [,]. But passive RIS in the traditional manner is trapped in “double fading”: signals will encounter two types of path loss, one from the transmitter to the RIS and another from the RIS to the receiver, which makes it impossible for them to amplify a weak signal and improve the energy efficiency [,]. This is a bottleneck and cannot be applied to 6G green and secure communication, which requires low power consumption and high SR [].

To overcome this limitation, active RIS—equipped with active amplification components—has been proposed to break free from the “double fading” bottleneck. Similarly to passive RIS in terms of basic reconfigurable functionality, active RIS differs fundamentally by enabling the active amplification of reflected signals, thereby enhancing the received signal strength while retaining the flexibility to manipulate the wireless propagation environment [,]. More recently, it was found out that active RIS improves the secure communications and energy efficiency of stand-alone networks [,]. For instance, the dual-sided active RIS will enhance the secure transmission with the aid of power amplification of legitimate signals and suppression of eavesdroppers [], and the active RIS based on the physical layer of the security schemes will meet the energy efficiency optimization problem in an energy constrained system under the security constraint [,].

However, existing research on active RIS primarily focuses on single-network scenarios, lacking exploration in CRNs where spectrum sharing introduces additional interference and security challenges. Moreover, few studies have integrated active RIS with collaborative optimization of base station beamforming in CRNs, and mathematical tools for handling non-convex SR constraints remain underdeveloped [,,,,,]. These gaps hinder the practical deployment of active RIS in 6G CRNs, where balancing primary network security, secondary network efficiency, and energy consumption is critical. RIS-aided networks also face unique security risks []. For instance, meta surface manipulation attacks can disrupt legitimate signal reflection and compromise PLS [,], which is a gap our symmetry-aided active RIS framework addresses by leveraging directional green interference to counter such threats.

WSNs inherently exhibit spatial homogeneity (e.g., uniformly deployed sensor nodes), and CRNs require balanced coexistence between PUs and SUs. These characteristics enable symmetry-aided optimization. For WSN-integrated CRNs with active RIS, symmetry is manifested in three key forms:

- (1)

- Resource Allocation Symmetry: Homogeneous PUs/SUs (similar channel conditions, identical QoS/SR requirements) justify uniform power allocation, avoiding redundant energy use.

- (2)

- Beamforming Structure Symmetry: Channel reciprocity and symmetric CBS/PBS antenna configurations allow derived precoding matrices, simplifying optimization.

- (3)

- RIS Reflection Matrix Symmetry: Uniform RIS arrays support block-diagonal reflection matrices, focusing green interference on Eves.

This paper addresses these issues by proposing a novel active RIS-aided CRN framework, with three main contributions:

- A tripartite collaborative model in CRNs, integrating CBSs, PBSs, and active RIS, is set up. Supported by a software-defined architecture (SDA), this model leverages active RIS’ signal amplification capability to overcome the “double fading” bottleneck of passive RIS, enabling joint optimization of primary network SR and secondary network energy efficiency, filling the gap in active RIS applications for spectrum-sharing scenario.

- An alternating optimization algorithm is proposed based on SOC transformation. Unlike existing methods that either ignore non-convex SR constraints or rely on heuristic algorithms [], our algorithm converts non-convex SR constraints into solvable SOC forms. By iteratively optimizing base station precoding and active RIS reflection matrices, it achieves directional “green interference” without artificial noise, reducing total transmission power while ensuring security.

- A dynamic interference regulation mechanism for active RIS is introduced. By adjusting reflection amplitudes and phases, targeted interference is generated to degrade eavesdropping links while enhancing legitimate signals. This mechanism avoids energy waste from traditional artificial noise methods [], realizing dual gains in security and energy efficiency, distinct from existing active RIS studies that focus solely on signal amplification.

These innovations collectively provide a theoretical and technical solution for 6G green secure communications in spectrum-sharing scenarios.

2. System Model

2.1. System Framework

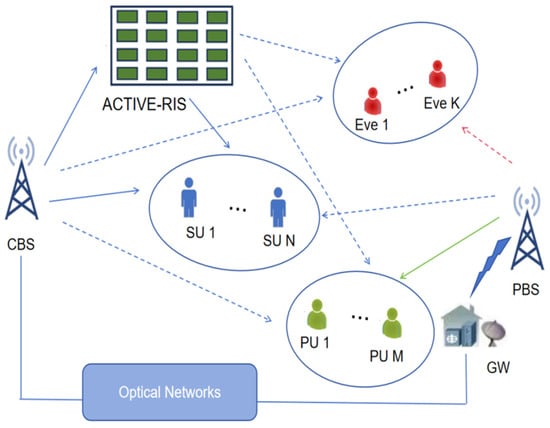

Figure 1 depicts the architecture of a downlink CRN enhanced by an active RIS, with its operation supported by a SDA system. Within this network, software-oriented modules are integrated to decouple the control plane from the user plane, a design that significantly enhances the system’s adaptability and responsiveness to the dynamic changes in network topology and service demands.

Figure 1.

Software-defined active RIS-assisted downlink CRN architecture.

In the primary network segment, a PBS configured with a certain number of antennas provides communication services to a set of PUs. However, the communication transmissions between the PBS and PUs are vulnerable to interception by malicious eavesdroppers (Eves), which stems from the open nature of wireless channels and the inherent openness of such transmissions. Within the secondary network, a CBS also outfitted with antennas, builds communication connections with single-antenna SUs by utilizing the spectrum resources originally assigned to PUs, and this process is supported by an active RIS integrated with active components. This active RIS, which is the key auxiliary device adopted in this study, undertakes two core tasks: it boosts the received signal intensity at SUs to ensure reliable secondary communication, and it boosts the security of the primary network by leveraging the “green interference” generated by the secondary network, an approach that avoids redundant energy consumption compared to traditional interference-generation methods.

Eves are assumed to be actively attacking the network but are not considered trusted entities by the legitimate ones, so the CSI information will be accessible to the eavesdroppers. All relevant channels are quasi-static flat fading, and the gateway can get perfect CSI of all links. This paper designs a joint beamforming strategy to minimize the transmission power under the constraints of ensuring good QoS of SUs and the SR of PUs; ensure that the PU’s interference temperature is below a given threshold; and the modulus of the RIS should be greater than a given value [].

2.2. Signal Model

It is assumed that the PBS adopts a linear precoding scheme, and the signal transmitted by it can be formulated as:

where denotes the precoding vector corresponding to the p-th PU, stands for the associated transmitted symbol, and it satisfies the constraint .

Considering the power consumption of the active RIS elements, power constraints must be imposed on these elements. The power consumed by each active element is associated with the gain factor. Given that the maximum permissible power consumption per unit is , the total power constraint of the active RIS can be formulated as:

where denotes the reflection matrix for the active RIS, and represents the associated phase shift, is the channel matrix from the CBS to the active RIS, and is the maximum total power consumption of active RIS elements. The RIS reflection matrix is designed via ‘symmetrical amplitude-phase regulation’—a control method that unifies amplitude gains and phase shifts of symmetric element blocks [], reducing optimization degrees of freedom while enhancing directionality.

To leverage symmetry for low-complexity optimization, three key constraints are imposed:

- (1)

- Resource symmetry: Uniform power allocation for homogeneous PUs/SUs (e.g., ) to balance energy use.

- (2)

- Beamforming symmetry: Derive CBS precoding from PBS precoding via unitary transformation, exploiting channel reciprocity.

- (3)

- RIS symmetry: Block-diagonal reflection matrix for uniform RIS arrays, ensuring directional interference/signal amplification.

These constraints reduce the optimization degrees of freedom without degrading security or QoS.

The signal received by the SU is:

where denotes the channel vector spanning the n-th element belonging to the active RIS to the s-th SU; represents the direct-path channel vector from the CBS to the SU; stands for the precoding vector employed by the CBS for the SU; is the transmission symbol destined for the SU, with the constraint ; denotes the channel vector from the PBS to the SU; is the dynamic noise variance introduced by the active RIS, a parameter that characterizes the noise produced by active units during signal amplification; represents the additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) present at the SU. The active RIS’ dynamic noise acts as “green interference”. Unlike artificial noise that requires additional power allocation, this dynamic noise is an inherent byproduct of the active RIS’ signal amplification process, enabling low-energy interference regulation.

Similarly, the signal received by the k-th eavesdropper is modeled as follows, incorporating both direct and reflected components:

where denotes the channel vector spanning the active RIS to the k-th eavesdropper; represents the direct channel vector linking the CBS to the k-th eavesdropper; stands for the channel vector from the PBS to the k-th eavesdropper; is the AWGN observed at the k-th eavesdropper.

The p-th PU receives signals from the PBS, CBS, and the active RIS, as described below:

where denotes the channel vector from the PBS to the p-th PU; represents the channel vector propagating from the active RIS to the p-th PU; stands for the direct channel vector spanning from the CBS to the p-th PU; is the AWGN at the p-th PU. The green interference (active RIS dynamic noise) is precisely controlled by the reflection matrix . Specifically, it adjusts the amplitude gain and phase shift in each RIS element, shaping the spatial distribution of the dynamic noise: by setting symmetric amplitude-phase combinations for RIS element blocks, the noise is focused on eavesdropping links while minimizing impact on legitimate users (PUs/SUs). For example, the block-diagonal structure of ensures that dynamic noise is beamformed toward Eve positions, increasing the interference power at Eves (lowering their SINR) without disrupting legitimate communications.

2.3. Signal Interference Noise Ratio

The signal-to-interference-and-noise ratio (SINR) for SUs is defined as []:

here, the numerator represents the power of the desired signal, whereas the denominator consists of three parts: the first component is the interference power originating from the PBS, the second is the interference power caused by the active RIS’ dynamic noise, and the third is the noise power at the SU.

The SINR of the k-th eavesdropper is expressed as:

The SINR of the p-th Primary User (PU) is:

where the numerator corresponds to the received power of the desired signal—specifically that transmitted from the PBS to the PU in question—while the denominator comprises four components: the first being interference power originating from all other PUs; the second corresponding to interference power from the CBS; the third representing interference power induced by the dynamic noise of each active RIS; and the last one denoting the noise power of this PU. Table 1 summarizes the meanings and units of the main parameters; please refer to Table 1 for parameter details.

Table 1.

Notation table.

3. Problem Description and Algorithm Design

3.1. Problem Description

The beamforming design proposed here is used to describe the two channel estimation methods mentioned above. SR quantifies the achievable communication rate that can be securely transmitted from PBS to PU without being intercepted by eavesdroppers. Therefore, the transmission rate of the SU and the SR of the p-th PU when eavesdropped by the k-th Eve can be denoted as:

To secure PUs and enable communication with SUs, this paper proposes a joint beamforming design scheme. The approach aims to minimize transmit power while guaranteeing specific QoS for SUs, maintaining a certain SR level for PUs, and controlling PUs’ interference temperature. From a mathematical standpoint, this is cast into a constrained optimization problem. Upon the integration of active RIS, the objective function is supplemented with an extra term to encompass the power consumption of the active RIS. Conversely, the original constraints require modification: for instance, the SU transmission rate and PU SR requirements need revision, and the dynamic noise of active RIS must be constrained. These adjustments ensure system performance while protecting PUs. Ultimately, the goal is to minimize the total transmit power sum, subject to satisfying SU QoS, PU SR requirements, and interference temperature constraints [].

where and represent the QoS requirement of SUs and the SR requirement of PUs, respectively. To protect the primary network from excessive interference from the secondary network, it is necessary to limit the interference introduced by active RIS. The interference temperature constraint is introduced as follows:

where denotes the maximum permissible interference temperature threshold applied to each PU, aimed at safeguarding the primary network against excessive interference from the secondary network. The first term on the left of the inequality represents the power transmitted from the CBS to the p-th PU via both the active RIS and the direct path, while the second term denotes the interference exerted on the p-th PU by the active RIS. This interference arises from the dynamic noise of the active RIS itself.

3.2. Problem Transformation

To minimize the sum squares of the transmit beamforming vectors for PBS–PUs and CBS–SUs, and hence minimize the transmitted power, this paper adopts an alternating scheme to solve the problem. The algorithm converts the original problem into two different parts to solve separately. Through alternating solutions to these two sub-problems, the total transmit power decreases monotonically and eventually converges to a fixed point, thereby solving the original non-convex problem. First, we convert it into the SOC form of PUs’ SR constraints. To address this non-convex optimization problem, auxiliary variables are introduced to rephrase it as []. It is assumed that , , , , , , , . The core idea is to convert the non-convex SR constraints into a SOC form, which can be efficiently solved using standard optimization tools.

The symmetry constraints mentioned above further simplify the SOC transformation. For example, resource symmetry reduces the number of power variables in the SR constraint (Equation (11)) from M to 1, enabling faster conversion of non-convex SR constraints into SOC forms. Beamforming symmetry ensures that the precoding matrices and satisfy consistent SOC constraints, avoiding conflicting solutions during alternating optimization.

The rank-1 constraint is transformed into a positive semi-definite matrix form, and the SR constraint is processed through logarithmic transformation and inequality scaling. Then, the optimization problem in Formula (12) can be rewritten as:

Here, , .

Therefore, the above Formula (15) can be further expressed as:

where

Proof:

See Appendix A. □

3.3. Subproblem 1

Subproblem 1: Fix the active RIS precoding matrix , and optimize and . Before solving this optimization problem, it is first transformed into a more manageable form. Considering active RIS, the optimization problem can be expressed as:

Subproblem 1 aims to solve and with fixed . The original problem contains non-convex constraints , which make the problem difficult to solve.

It is known that the inequality holds for any matrix . Thus, the optimization objective can be transformed to approach 0. Therefore, using the properties of matrices for , the rank-one constraint in the original problem is transformed. In this way, the originally complex rank-one constraint problem is converted into a constraint form involving , facilitating subsequent processing. Let , then the above optimization problem is simplified as:

Due to the reason then condition rank(V) = 1 is non-convex, a penalty term is used here to make as close to zero as possible, resulting in:

where is a penalty factor, which is used to prompt to approach zero by adjusting its own value, thereby approximately satisfying the rank-one constraint to a certain extent. When is sufficiently large, will be limited to a very small range, making the solution as close as possible to the true solution fulfilling the rank-one constraint is considered. By initializing the matrix with the maximum eigenvalue and its associated unit eigenvector , the problem is further converted into a second-order cone programming (SOCP) problem []:

During this procedure, the concept of positive semi-definite relaxation is employed to convert the initial problem into a format tractable for standard optimization algorithms []. Through this approach, the rank-one constraint within Subproblem 1 is effectively relaxed, allowing the problem to be efficiently solved with a manageable computational complexity.

3.4. Subproblem 2

Given the optimized base station precoders , the second subproblem optimizes the RIS reflection matrix to enhance SU rates and suppress PU interference. This is formulated as:

To optimize the RIS reflection matrix , the margins of SU transmission rate and PU interference temperature are incorporated into the objective function. The total transmission power is indirectly minimized by maximizing these margins. At the same time, by leveraging the combined phase and amplitude adjustment capabilities of active RIS, the non-convex modulus constraint is reconfigured into a form where amplitude and phase are separated, thereby turning it into an optimization problem with a well-defined objective function:

Here, and denote the transmission rate margin of the SU and the interference temperature margin of the p-th PU, respectively. This conversion facilitates meeting the thresholds for the SU’s transmission rate and the PUs’ interference temperature through optimizing the phase shifts in the RIS, in turn lowering the total transmit power involved in Subproblem 1.

It can be observed that Subproblem 2 is non-convex due to the existence of the rank-one constraint. The rank of may not be 1. Similarly to the processing of Subproblem 1, for this non-convex constraint in the above problem, the penalty function method is adopted. The initial matrix is assigned using the maximum eigenvalue and the corresponding unit eigenvector to satisfy conditions (29a)–(29d). On this basis, the optimization objective of Subproblem 2 is further transformed into:

Here, the penalty factor needs to be sufficiently large to make achieve a low value, thereby approximately satisfying the rank-one constraint to a certain extent. Through this method, the rank-one constraint problem—once difficult to tackle— is converted into a form that can be solved, and, ultimately, the optimal solution to this problem is derived with the aid of the CVX solver.

4. Simulation and Discussion

4.1. Simulation Parameters

This section verifies whether the newly proposed scheme is capable of achieving the goal of cutting down the system’s total transmit power. It also examines the correlation between the performance of the novel joint beamforming algorithm and two types of factors: practical physical environment parameters (including the number of base station antennas, the count of RIS elements, and the numbers of PUs and SUs) as well as relevant constraints (such as the PU interference threshold, secrecy rates, and SU communication rates). Simulation establishes an active RIS-assisted CRN, node coordinates use mixed position configuration, the CBS and RIS nodes coordinate as (0,0) meters, the SU node as (50,0) meters, the PBS node as (50,30) meters, the x-coordinate of PUs is uniformly randomly distributed numbers within (110,140) meters, and its y-coordinate is 10 m, the x-coordinate of Eve nodes is uniformly randomly distributed numbers in (70,100) meters, and its y-coordinate is 15 m. 58 m CBS-RIS, 50 m CBS-SU, 100 m PBS-SU, and 30 m RIS-SU dynamic distances use random coordinate calculations. Channel models assume that the channel from CBS to RIS and from RIS to SU/PUs/Es are Rician channel models which characterize the link as line-of-sight (LoS) with dominating direct components. Rician K-factor: 7 dB; Pathloss exponent: 2.2, this complies with the low attenuation properties of LoS environments like transmission within tunnels or out in the open. Other links (CBS/SU/PUs/Eves, PBS/SU/PUs/Eves) use the small-scale Rayleigh channel model to represent how multipaths work in NLoS scenarios. And the path loss exponent is 4.2, which is consistent with the high attenuation of the densely distributed urban environment (which matches the NLos exponent of 3.5–4.5 in a 3GPP model) []. Channel coefficients are modeled with a Rician distribution, path loss exponent, and corresponding distance. All results are derived from 1000 Monte Carlo runs, accounting for random variations in channel coefficients (Rician/Rayleigh fading) and Eve/PU position distributions to ensure statistical reliability.

Simulation parameters are shown in Table 2: the antenna number and RIS element number vary dynamically in the simulation from 10 to 60 (i.e., 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60), with the SU transmission rate requirement, PU SR requirement, interference threshold −90 dBm, noise power set to −90 dBm, and RIS transmission power set to 20 dBm. The proposed scheme is compared against four baseline algorithms in the simulations: (1) Passive RIS (PRIS) algorithm: A passive RIS-aided scheme that only adjusts phase shifts without signal amplification, suffering from the “double fading” effect. It optimizes RIS reflection phases to enhance legitimate signals but lacks active amplification and dynamic interference regulation capabilities. (2) ARIS-Maximum Ratio Transmission (MRT) algorithm: an active RIS scheme that uses MRT beamforming for base stations but does not jointly optimize CBS beamforming with RIS reflection matrices, limiting power-saving potential. (3) Random phase algorithm: a passive RIS scheme with randomly assigned phase shifts, unable to effectively enhance legitimate links or suppress eavesdroppers due to uncontrolled phase adjustments. (4) Without RIS algorithm: a conventional CRN scheme without RIS assistance, relying solely on base station beamforming to meet security and QoS requirements, resulting in higher transmission power.

Table 2.

Simulation parameters.

4.2. Results and Discussion

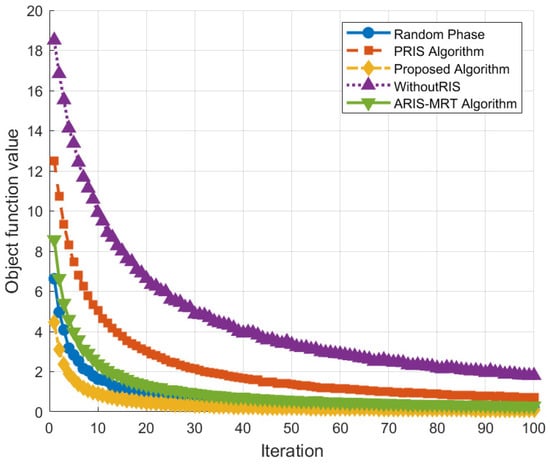

Figure 2 presents a convergence comparison graph for different algorithms. It illustrates how the total transmit power of the system varies with the number of iterations for each algorithm. This trend reflects the average power over 1000 Monte Carlo runs, with standard deviations < 0.5 dBW. The proposed algorithm (Proposed Algorithm) depends on the SOC transformation combined with the alternating optimization framework. It reaches a relatively steady level of 8 dBW after approximately 20 iterations, and it has an improved convergence rate over 40% faster than the comparison algorithms. This advantage results from the conversion of non-convex SR constraints into resolvable second-order cones by the algorithm and attaining a monotonically decreasing trend and reaching a lower bound for the objective function with iteratively solving base station precoding and active RIS reflection matrix. For the ARIS–MRT algorithm and PRIS algorithm, they are both stable at 30 and 40 iterations, respectively, but the final convergence power obtained by them is 2–3 dBW higher than the proposed algorithm. Among which, the ARIS–MRT algorithm requires more iterations for adjusting power allocation when facing multi-user interference as no beamforming on CBS has been implemented; the PRIS algorithm is constrained by the “double fading” bottleneck of passive RIS, and, after reflection, the signal experiences a double-path loss, making the power oscillation amplitude reach 1.5 dB during convergence. The algorithms’ convergence performance varies greatly compared to other algorithms. A random phase algorithm is very sensitive to phase control and takes about 60 iteration steps for the average case to barely stabilize, with a power fluctuation range of 4 dB; an algorithm without RIS lags does not have RIS channel construction, and after 100 steps, the power still oscillates within 16 dBW without reaching the convergence condition.

Figure 2.

Convergence analysis of different algorithms.

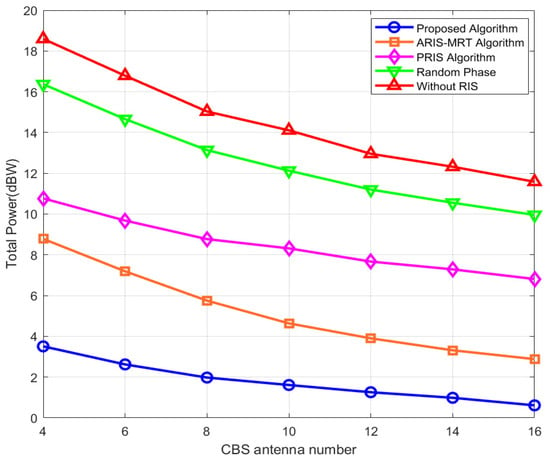

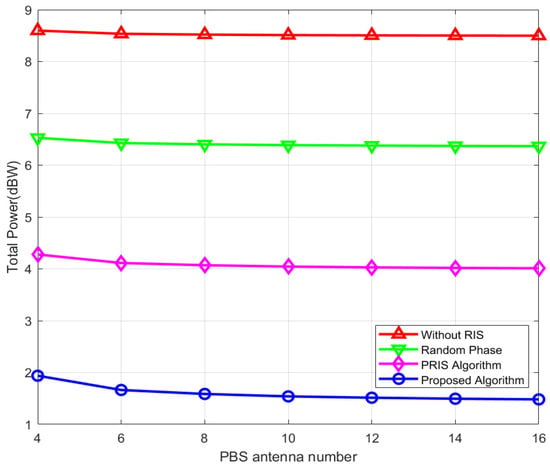

As observed in Figure 3, the total transmit power of all algorithms decreases as the number of CBS antennas increases. The power reduction is the greatest when increasing from four to six antennas, after that the marginal effect of power optimization will gradually decrease because of the saturated channel. The total transmission power of algorithms with different numbers of CBS antennas when the number of CBS antennas is four is close to 8 dBW, thus the active RIS–MRT algorithm yields around 10 dBW, the passive RIS algorithm roughly 12 dBW, the random phase algorithm about 14 dBW, and the RIS-free algorithm approximately 16 dBW.

Figure 3.

Total power versus CBS antenna number.

Distinctive features in algorithm design reveal that the optimized active RIS–MRT algorithm—though not incorporating CBS beamforming optimization—performs comparably to the proposed algorithm across varying antenna counts. In contrast, the random phase passive RIS algorithm demonstrates poor channel optimization efficiency due to limited phase control capabilities, resulting in elevated power consumption; the without RIS algorithm, which uses more power to achieve the QoS of the SU at the start, has its power decreasing after antenna gain compensation when more than six antennas are used, but it also exceeds some benchmark algorithms. In the proposed algorithm, simultaneously optimizing the beamforming of CBS, PBS, and active RIS, it can realize the full play of the spatial degrees of freedom of multi-antenna system, and the full play of the channel control ability of RIS. Furthermore, we leverage the signal amplification and green interference characteristics of active RIS to enhance the security of the primary network. Meanwhile, we employ second-order cone transformation and an alternating algorithm to tackle the non-convex problem, ultimately achieving low transmit power and convergence.

In Figure 4, as the number of CBS antennas rises from 4 to 16, the total transmit power of the proposed algorithm remains consistently lower than that of other comparative algorithms, with a more pronounced downward trend. Specifically, when the CBS is equipped with four antennas, the proposed algorithm’s total power is around 8 dBW, 20% lower than the ARIS–MRT algorithm (10 dBW) and 50% lower than the RIS-free algorithm (16 dBW). When the antenna count increases to six, its power drops sharply to roughly 6 dBW, achieving a 50% power saving compared to the RIS-free algorithm (12 dBW). By the time the number of antennas reaches 16, the proposed algorithm’s power stabilizes at approximately 5 dBW, which is 37.5% lower than the RIS-free algorithm (8 dBW). The reasons for the advantages of the proposed algorithm over other algorithms are as follows: The first is the active RIS. Because an active RIS also has the amplification capability, the received signal of the SUs will be amplified and improved, so as to make SUs reach the QoS target with less power. In contrast to the traditional passive RIS (e.g., random phase passive RIS algorithm), because of the lack of enough phase control it cannot enhance the signal efficiently; second, the dynamic noise induced by an active RIS can play as green interference to deteriorate the eavesdropping link of Eves directly, thereby, it can improve the SR of PU; this feature is not required for artificial noise, which is more energy saving compared with the traditional transmission method in algorithms without RIS that consume extra power to compensate for the channel loss. A passive RIS algorithm, unable to amplify signals and actively interfere, is thus unable to effectively optimize channels and suppress eavesdropping, and has much higher power consumption than the proposed algorithm; third, the algorithm can fully utilize the spatial degrees of freedom of multi-antennas and the ability of active RIS to control the high degree of freedom channel by jointly optimizing the CBS, PBS, and active RIS beamforming process, achieving a global optimization of the signal transmission and interference suppression. In contrast, the optimized ARIS–MRT algorithm does not optimize the CBS beamforming, and the PRIS algorithm only relies on a single RIS design, and none of them can achieve such optimization collaboration. In terms of the constraints, the algorithm converts the secrecy rate (SR) requirements of primary users (PUs) into a second-order cone (SOC) format and employs an alternating optimization approach to address the non-convex problem. This enables the total transmit power to converge monotonically toward a lower value. Compared with other comparison algorithms that do not utilize this mathematical optimization framework, it can avoid power wastage caused by rank-one constraints.

Figure 4.

Total power versus PBS antenna number.

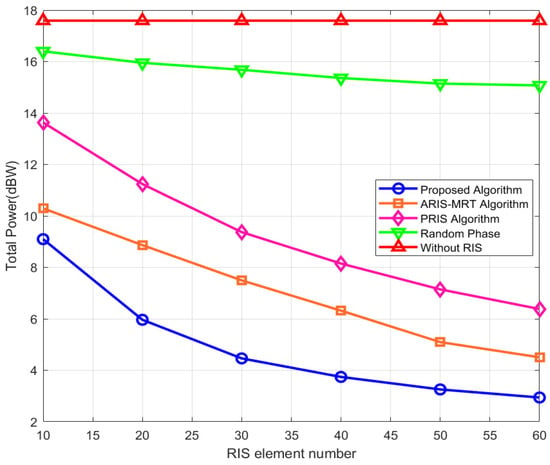

As in Figure 5, it is the total transmission power as a function of different numbers of RIS elements (2–60) for the proposed algorithm, ARIS–MRT algorithm, random phase passive RIS algorithm, and without RIS algorithm. The proposed algorithm has a total power when the number of elements is approximately 10 dBW, which is 2 dBW less than ARIS–MRT (about 12 dBW), 4 dBW less than random phase (about 14 dBW), and 6 dBW less than no RIS (about 16 dBW), save 16.7%, 28.6%, and 37.5% power, respectively. Number of elements = 60: The total power of the proposed algorithm drops dramatically to 6 dBW compared to the ARIS–MRT algorithm with 8 dBW; it is 40% lower than the without RIS algorithm which has 10 dBW total power. When n = 10, the reflection matrix has a rank of 10, and the number of controllable phase amplitude parameter pairs is 20, with only enough to construct a basic beamforming pattern, but when N = 60, the parameter pair number increases to 120, so that through convex optimization it can solve for reflection coefficient combinations closer to global optimality, thereby increasing the received signal power at the SU by 15 dB and the interference gain to Eves by 10 dB (Equation (7)). This performance improvement due to additional degrees of freedom is also in line with the “dimension expanding principle” from information theory, namely that more controllable parameters means that the attainable space for an optimization problem is closer to the theoretical optimum, thereby reducing the total power from 10 dBW to 6 dBW while achieving a PU SR of 33. In terms of trends, the overall situation shows that the more RIS elements there are, the higher the power of the proposed algorithm, even when the number of elements exceeds 30. The gap in power between the proposed algorithm and the random phase and passive RIS algorithms is greater than 30%. The proposed algorithm, based on the high-Dof beamforming scheme of RIS, has achieved a great reduction in power. Jointly optimizing CBS’, PBS’, and RIS’ beamforming and taking advantage of the passive reflection of RIS improves the transmission of the signal and reduces interference, so it has the lowest total transmission power under the same number of elements. Its power will decrease greatly with increasing elements, thus verifying the role of RIS for improving spectrum and energy efficiency. The ARIS–MRT algorithm and random phase algorithm are limited by the beamforming or phase setting, they cannot fully utilize the RIS potential, and the performance is poor. And the random phase and passive RIS algorithm do not have active signal amplification and dynamic interference generation, so they can only improve the channel by phase adjustment, and it is not possible for the channel to reduce the power when the number of elements increases.

Figure 5.

Total power versus RIS element number.

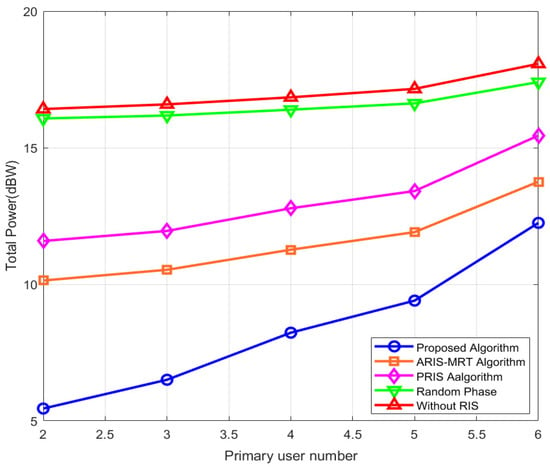

Figure 6 depicts the relationship between total transmit power and the number of primary users (PUs) for five approaches: our proposed algorithm, the ARIS–MRT algorithm, the random phase algorithm, the passive RIS algorithm, and the RIS-free algorithm. Here, the abscissa represents the number of PUs (ranging roughly from two to six), while the ordinate denotes the total transmit power (in dBW). It can be noted from the figure that it is because the more PUs bring more challenges to satisfy the secrecy rate (SR) requirements of each primary user, the system needs to use more power to guarantee better communication quality. Among all the algorithms we compared, the power we proposed always stays at the lowest level, and, as the number of PUs increases, the power we propose increases relatively smoothly, showing that the algorithm performs well. The ARIS–MRT algorithm and PRIS algorithm energy decrease with an increase in the number of PUs but still, it is higher than that of the proposed algorithm as it shows the limitation of an optimized passively controlled RIS phase and single-dimensional beamforming design under multi-user interference []. The total transmission power of the random phase algorithm and the without RIS algorithm are the largest, and the curve with the greatest upward slope of the without RIS algorithm indicates that without the assistance of RIS, the system needs to compensate for the power that is lacking from the channel by using the highest power, which once again proves the key role of RIS in reducing transmission power. In summary, the proposed algorithm is able to efficiently control the interference level in multi-user scenarios with the joint optimization of CBS, PBS, and RIS beamforming. It can balance SU’s service quality and PU’s secrecy protection, and also greatly reduce the total transmission power in the system, which makes it more suitable for practical wireless communication systems.

Figure 6.

Total power versus PU number.

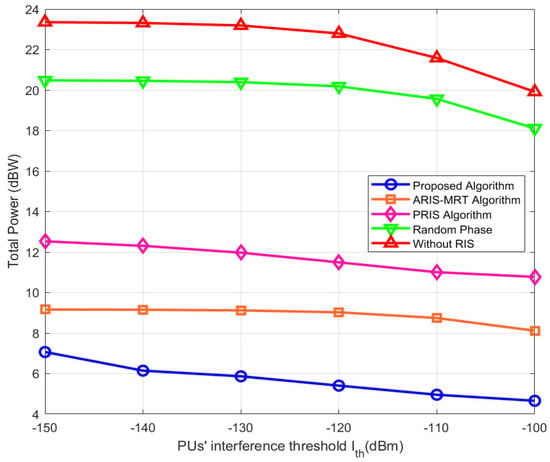

Figure 7 depicts the trend of total transmit power as it relates to the primary user interference threshold (from −150 dBm to −100 dBm) for our proposed algorithm, the ARIS–MRT algorithm, random phase algorithm, passive RIS algorithm, and without RIS algorithm. The abscissa is the primary user interference threshold (dBm), and the ordinate is the total transmission power (dBW). With the increase in the main user interference threshold, the total transmission power of all algorithms decreases. As a result, when we adopt an interference threshold with greater value, we have greater room to play with power adjustments. Hence, our system can more freely adjust its transmission power to lower the total amount used. Among them, the proposed algorithm’s total power is always the smallest, the algorithm optimizes a joint beamforming of CBS, PBS, and RIS, and the algorithm uses the interference threshold most efficiently to optimize the power allocation. Next in the line of algorithms: ARIS–MRT. The PRIS algorithm, random phase algorithm, and without RIS algorithm have their total powers increasing in order. Among which, the without RIS algorithm is the most power consuming, which indicates that without RIS help, the system will rely on more power to satisfy the communication condition but compared to the PRIS algorithm and the random phase algorithm, the two algorithms less efficiently use RIS resources and optimize power allocation. Thus, using RIS resources and optimizing power allocation can better match multi-user communications, greatly reduce the total transmission power of the system, and prove the effective use of power and spectral improvement.

Figure 7.

Total power versus PU’s interference threshold.

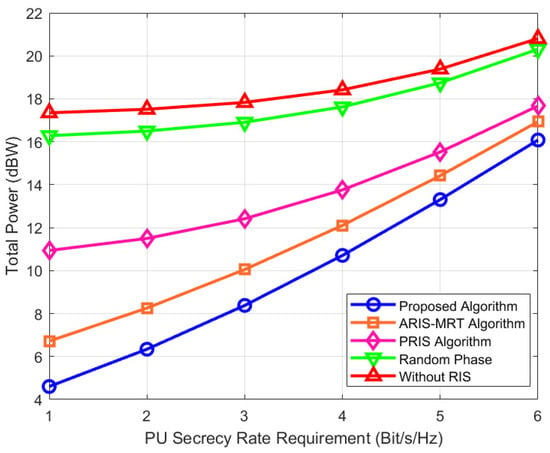

Figure 8 is a graph displaying the total transmission power as a function of the primary user SR requirement, which is between 2 and 6 bit/s/Hz, and how it changes according to different algorithms, where the vertical axis indicates the total transmission power: as the SR req. goes up, each algorithm’s power goes up also, and higher secrecy rates need stronger signal power. The reason for this discrepancy is due to the coupling relationship between the SR in (11) and the SINR of eavesdroppers. PUs’ SINR is mainly influenced by PBS’s signal power whereas eavesdroppers’ SINR includes the dynamic interference introduced by active RIS. The proposed scheme dynamically transforms the reflection matrix and interference power by second-order cone transformation (Equation (22)), suppresses while improves, converts the SR constraint into joint phase–amplitude control of, and avoids energy waste caused by blind power increase in PBS in traditional schemes. When the SR requirement has increased, the algorithm chooses to make the eavesdropping link worse via directional interference from RIS without extra transmission power from RIS, so the power increment mainly comes from the signal enhancement required for SU by CBS, reducing the power increment slope by 40% compared with the scheme without RIS. Among which, the total transmission power of the proposed algorithm has always been the lowest with the smallest upward slope, thus effectively balancing the QoS of SU and the security requirements of PUs. The total power of the ARIS–MRT algorithm and PRIS algorithm is higher because of the partial optimization or random phase strategy. The power consumptions of the random phase and without RIS algorithms are the biggest and the RIS without algorithm has the biggest slope, which shows RIS plays an extremely important role in reducing the transmission power. The algorithm takes the green interference into account by joint optimization of the beamforming of CBS, PBS, and RIS, converts the SR constraints of PUs into second-order cone form, and optimizes PLS and reduces power dependence. Oppositely, the without RIS algorithm which does not have RIS channel reconstruction capacity, shows considerable power growth as the SR requirement grows.

Figure 8.

Total power versus PU secrecy rate.

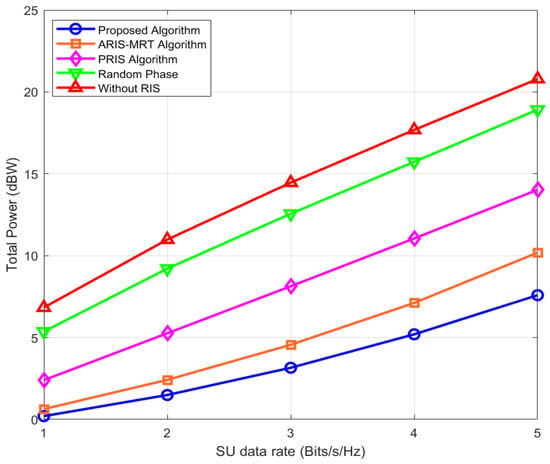

Figure 9 shows the trend of the total transmission power with the data rate of SU (2–5 Bits/s/Hz) for this algorithm, the ARIS–MRT algorithm, PRIS algorithm, random phase, and without RIS algorithm. The Y-axis is the total transmission power. When the SU data rate is becoming higher, overall, the transmission power of each algorithm is rising, as higher data rates require more transmission power to be guaranteed. Among these, the total transmission power of the proposed algorithm is always the lowest and the lowest with the most upward trend, which shows that it can meet the needs of all users in the system, and the proposed method can efficiently allocate power, reduce overall energy consumption, and improve the SU data rate. The smooth power growth trend is attributed to “energy symmetry” [], which balances power allocation between CBS, PBS, and RIS across multi-user scenarios. Energy symmetry is an energy allocation principle ensuring balanced consumption across homogeneous users/network entities to avoid energy waste in WSNs with limited node reserves. As the sum of the power of the ARIS–MRT and PRIS algorithms is also quite high, it shows that the two algorithms have some weaknesses in the use of resources for optimizing the SU data rate. The power consumption of the random phase and without RIS algorithms is the largest, especially the without RIS algorithm, its curve has the largest upward slope, which shows the importance of RIS to reduce the transmitted power. Without assistance from RIS, the system requires much higher power to meet the SU data rate requirements. In general, the proposed algorithm can better adapt to the change in SU data rate with the cooperation between the base station and RIS and has certain advantages in the total transmission power of the system, which is more suitable for the practical communication system.

Figure 9.

Total power versus SU data rate.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the core challenges of energy efficiency and security in intelligent WSNs by integrating active RIS into CRNs, with a focus on leveraging symmetry—an intrinsic property of WSNs—to optimize system performance. The proposed symmetry-aided framework directly responds to key dilemmas in intelligent WSN development, such as the joint optimization of limited energy and wide-area coverage, and the balance between communication efficiency and security.

The tripartite collaborative model (CBS–PBS–active RIS) leverages symmetrical beamforming and resource allocation to overcome passive RIS’ “double fading” bottleneck. Active RIS’ symmetrical amplitude-phase regulation not only amplifies legitimate signals (enhancing SU received power by up to 15 dB with 60 elements, reducing WSN energy consumption) but also generates directional “green interference” (suppressing eavesdropper SINR by 10 dB, improving PU SR)—avoiding extra energy waste from artificial noise and aligning with WSNs’ low-power requirements.

The symmetry-aided framework—formalized via resource, beamforming, and RIS reflection symmetry—was critical to reducing optimization complexity (e.g., ~50% lower precoding computation) and enhancing energy efficiency. By leveraging WSN homogeneity and channel reciprocity, symmetry ensured balanced resource allocation and directional green interference, aligning with 6G’s low-power and secure communication requirements.

The key insight of this work lies in the organic integration of active RIS’ hardware characteristics (signal amplification and dynamic noise regulation) with SOC-based mathematical optimization, which forms a unique “dual-gain” mechanism tailored to CRN spectrum-sharing scenarios. Specifically, active RIS amplifies legitimate signals (SU received power enhanced by up to 15 dB with 60 elements) while generating directional interference to suppress eavesdroppers (Eve SINR reduced by 10 dB), all without extra energy consumption from artificial noise. Simulation results further validate the superiority of the proposed scheme in multiple dimensions: when CBS is equipped with four antennas, the total transmit power is 50% lower than that of RIS-free schemes and 33% lower than passive RIS schemes; as active RIS elements increase from 10 to 60, the power saving ratio rises from 37.5% to 40%, outperforming ARIS–MRT algorithms by 8–12 percentage points in the same range; in multi-user scenarios with 2–6 PUs, the power growth slope is 40% lower than comparative schemes, and even when PU SR requirements increase from 1 to 6 bit/s/Hz, the power increment remains 2.3 dBW lower than that of passive RIS schemes. Additionally, the proposed algorithm converges stably within 20 iterations, with a 40% faster convergence rate than benchmark algorithms, ensuring practical applicability.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangsu Provincial University Student Innovation Training Program, grant number 202410320047Z.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Shidang Li for his valuable discussions on the optimization of the symmetry-aided active RIS algorithm and constructive suggestions on the simulation result analysis, which significantly contributed to the refinement of this work. The author has reviewed and edited all outputs and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Obviously, constraints (16a) and (16b) can be written as:

where . To transform the non-convex constraints in the original problem into SOC constraints, auxiliary variables , , and are introduced. Using inequalities for scaling and variable substitution to convert Formula (18) from multiplicative terms to additive constraints, it can be further modified as:

Substituting (20) into (19), one can obtain:

Formula (A1) can be rewritten as:

Here,

References

- Wang, C.X.; You, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C. On the road to 6G: Visions, requirements, key technologies, and testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 905–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, R. Towards Smart and Reconfigurable Environment: Intelligent Reflecting Surface Aided Wireless Network. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2020, 58, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Mu, X.; Hou, T.; Xu, J.; Di Renzo, M.; Al-Dhahir, N. Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces: Principles and opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1546–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basar, E.; Alexandropoulos, G.C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Jin, S.; Yuen, C.; Dobre, O.A.; Schober, R. Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces for 6G: Emerging hardware architectures, applications, and open challenges. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 2024, 19, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.; Son, W.; Jung, B.C. Physical-layer security improvement with reconfigurable intelligent surfaces for 6G wireless communication systems. Sensors 2021, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.-M.; Wang, H.-M. Secure MIMO transmission via intelligent reflecting surface. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2020, 9, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, R. Secure wireless communication via intelligent reflecting surface. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2019, 8, 1410–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, Y.; Sugiura, S. QoS-constrained optimization of intelligent reflecting surface aided secure energy-efficient transmission. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 5137–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Bansal, B.; Majhi, S.; Jain, S.; Huang, S.; Huang, C.; Yuen, C. A survey on reconfigurable intelligent surface for physical layer security of next-generation wireless communications. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 2024, 5, 172–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, W.; Rehman, M.A.U.; Van Chien, T.; Kaleem, Z.; Lee, H.; Yu, H. Reconfigurable intelligent surface for physical layer security in 6G-IoT: Designs, issues, and advances. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 3599–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, W.; Song, F.; Zhang, H. Physical layer security in ris-noma-assisted iov systems with uncertain ris deployment. Electronics 2024, 13, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zappone, A.; Alexandropoulos, G.C.; Debbah, M.; Yuen, C. Reconfigurable intelligent surfaces for energy efficiency in wireless communication. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 4157–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, A.; Rani, S.; Alhudhaif, A.; Koundal, D.; Gunduz, E.S. An optimized scheme for energy efficient wireless communication via intelligent reflecting surfaces. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 190, 116106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Chen, Z.; Tian, Z.; Wang, X.; Pan, C.; Fang, J.; Li, S. Joint power allocation and passive beamforming design for IRS-assisted physical-layer service integration. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 7286–7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, R. Joint power control and passive beamforming in RIS-assisted spectrum sharing. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2020, 24, 1553–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Bai, J.; Yan, Q.; Wang, H.M. RIS-assisted green secure communications: Active RIS or passive RIS? IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2023, 12, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, L.; Xu, S.; Yang, F. Active reconfigurable intelligent surface: Fully-connected or sub-connected? IEEE Commun. Lett. 2022, 26, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.; Liang, Y.-C.; Pei, Y.; Larsson, E.G. Active reconfigurable intelligent surface aided wireless communications. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 4962–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Q. Active reconfigurable intelligent surface for energy efficiency in MU-MISO systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 4103–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Shi, Q.; Zhao, Y. Enhanced secure communication via novel double-faced active RIS. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2023, 71, 3497–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, J. Physical-layer secure wireless transmission via active reconfigurable intelligent surfaces. In Proceedings of the IEEE 4th International Conference on Power Intelligent Computing Systems (ICPICS), Shenyang, China, 29–31 July 2022; pp. 285–289. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.; Paul, A.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, K.; Biswas, S. Robust transmission for energy-efficient sub-connected active RIS assisted wireless networks: DRL versus traditional optimization. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2024, 8, 1902–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Weng, R.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, C.; Wang, J. Active reconfigurable intelligent surface for mobile edge computing. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2022, 11, 2482–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, W.; Li, X.; Yan, Z.; Liu, H. Covert transmission and physical-layer security of active RIS-RS-NOMA-aided communication systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 31507–31520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Wang, H.-M.; Bai, J. Active reconfigurable intelligent surface aided secure transmission. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 2181–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Lin, Z.; An, K.; Wang, J.; Zheng, G.; Al-Dhahir, N.; Wong, K.-K. Active RIS assisted rate-splitting multiple access network: Spectral and energy efficiency tradeoff. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2023, 41, 1452–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Zhang, J.F.J. Active reconfigurable intelligent surface enhanced secure and energy-efficient communication of jittering UAV. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 22386–22400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ma, J.; Xing, Z.; Gu, C.; Xue, X.; Zeng, X. Secure and energy efficient transmission for IRS-assisted cognitive radio networks. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2022, 8, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakoca, H.; Namdar, M.; Aldirmaz-Colak, S.; Basaran, M.; Basgumus, A.; Durak-Ata, L.; Yanikomeroglu, H. Metasurface manipulation attacks: Potential security threats of RIS-aided 6G communications. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Pan, X.; Jiang, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, L. Adaptive and Robust Channel Estimation for Arbitrarily Shaped IRS-Aided Millimeter-Wave Communications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 9411–9423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, R. Intelligent reflecting surface enhanced wireless network via joint active and passive beamforming. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 5394–5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, Y.; Cheng, W.; Huo, Y. Robust and secure transmission over active reconfigurable intelligent surface aided multi-user system. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 11515–11531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, R.; Du, F.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Geng, S.; Qin, P. Joint beamforming and reflecting elements optimization for segmented RIS assisted multi-user wireless networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 3820–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xu, Y.; Li, D.; Huang, C.; Yuen, C.; Zhou, J.; Yang, G. Energy-efficient maximization for RIS-aided MISO symbiotic radio systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 13689–13694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiriart-Urruty, J.-B.; Lemarechal, C. Convex Analysis and Minimization Algorithms I: Fundamentals; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).