1. Introduction

Air pollution remains a major global issue, heavily affecting both human health and the environment. According to the World Health Organization [

1], exposure to high levels of air pollution significantly increases the risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. The heavy reliance on fossil fuels, especially in regions with extreme climates such as the GCC countries, results in higher emissions of CO

2, SO

2, and NO

2, which are key drivers of environmental damage and long-term climate change [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Recent studies report that air pollution causes about 7 million premature deaths worldwide each year, with urban populations particularly affected by vehicular and industrial emissions [

1]. In developing urban areas, unequal access to green spaces worsens exposure risks [

6]. For example, recent contributions in the field include Bayesian inferential motion planning using heavy-tailed distributions [

1], simulation of atmospheric mercury dispersion and deposition in Tehran [

6], dispersion modeling of air pollution from copper smelter emissions [

7], and health risk assessments with Sobol’ sensitivity analysis of power plant air pollution (SO

2 and NOx) considering fuel changes [

8]. These studies highlight the growing use of modeling techniques for pollutant dispersion and risk assessment, supporting the need for UAV-based monitoring frameworks [

9,

10]. Therefore, effective monitoring and regulation of these pollutants are essential to support sustainable urban development and safeguard public health.

Conventional air quality monitoring methods, based on stationary stations and threshold-driven models, often assume a uniform distribution of pollutants in both time and space. However, real-world conditions are characterized by irregularities caused by traffic emissions, industrial activities, wind turbulence, and sensor noise. These asymmetric factors challenge the validity of deterministic and purely statistical approaches. While modern electrochemical sensors have been evaluated under various conditions [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], their measurements remain sensitive to calibration, drift, and local disturbances, highlighting the need for advanced computational methods.

Fuzzy logic provides a flexible framework for handling uncertainty, incomplete data, and nonlinear relationships in environmental systems. Symmetric fuzzy rules capture stable and predictable patterns, while asymmetric rules model deviations, exceptions, and disturbances [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. This duality reflects the inherent structure of environmental data: symmetry corresponds to equilibrium pollutant distributions, whereas asymmetry arises from turbulence, localized emissions, or rapid changes in operating conditions [

17]. Integrating these principles into monitoring systems improves robustness and adaptability compared to classical threshold-based approaches.

The combination of symmetric and asymmetric techniques for assessing air quality underscores the need to address uncertainty and data variability through sophisticated fuzzy logic, evidence theory, and multi-criteria decision-making frameworks. These methodologies enhance traditional deterministic models by integrating uncertainty assessment and a balance of subjective and objective weighting, thereby strengthening the theoretical basis of air quality modeling [

23,

24,

25].

The combination of evidence theory and machine learning methods, such as K-nearest neighbors, offers a promising theoretical advance by effectively capturing spatiotemporal relationships and levels of pollutant toxicity that conventional symmetric approaches may miss. It questions the sufficiency of treating data uniformly and advocates for the use of asymmetric frameworks for deeper assessments [

24,

26].

The literature reviewed highlights the theoretical importance of entropy-based weighting techniques and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation frameworks for reflecting the complex, multifaceted nature of air pollution data. These approaches provide a solid mathematical foundation for addressing the variability and uncertainty inherent in measurements of pollutant concentrations [

27,

28,

29].

Recent theoretical advancements in multi-attribute group decision-making (MAGDM) and multi-granularity rough sets offer innovative approaches to addressing indecision and hesitancy in real-time air quality assessments. This progress advances the theoretical discussion surrounding data fusion and decision-making in the context of environmental monitoring uncertainty [

30].

Research comparing statistical models and machine learning methods for predicting air quality enhances our theoretical insights into the trade-offs in model performance, highlighting the unique advantages of both conventional statistical techniques and hybrid or heuristic models in anticipating pollutant levels [

31,

32].

Theoretical insights from compositional data analysis and stochastic local-to-global modeling approaches challenge traditional air quality indices by offering frameworks that better reflect pollutant interactions and spatial variations, thereby refining the conceptualization of air quality assessment [

33,

34].

Despite a broad range of studies in air quality monitoring, several limitations still exist, including geographic bias, limited real-time integration, methodological constraints in uncertainty handling, a lack of predictive modeling, small or narrow pollutant sets, computational complexity and scalability issues, and an overemphasis on single methodologies, among others.

Recent developments in sensor networks and UAV platforms have further expanded the scope of air quality monitoring. UAVs extend spatial coverage, overcome the limitations of fixed stations, and provide real-time heterogeneous data that can be directly incorporated into fuzzy inference models. UAV-based monitoring systems have demonstrated improvements in pollutant identification, spatial resolution, and flexibility [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], but they also face challenges such as payload limitations, calibration, and flight endurance [

42,

43,

44]. Advances in autonomous UAV fleets, IoT-based communication, and machine learning-based prediction further highlight the potential of intelligent, adaptive monitoring frameworks [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Fuzzy logic systems (FISs) have been widely applied to environmental monitoring due to their ability to handle uncertain, noisy, and asymmetric data. In particular, FIS enables UAV-based monitoring systems to make adaptive decisions under dynamic environmental conditions, such as adjusting flight trajectories in response to local pollutant concentrations. Previous studies have demonstrated the successful application of fuzzy inference for air quality assessment, enabling graded classification of pollutant levels and improved robustness compared to threshold-based methods [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Despite these advances, most existing methods employ fuzzy logic primarily as a functional tool without explicitly addressing the inherent dichotomy between symmetry and asymmetry in environmental processes.

Recent studies have explored hybrid and adaptive fuzzy control systems in environmental monitoring, including ANFIS and TSK-type fuzzy systems, as well as fuzzy–machine learning combinations [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Unlike these approaches, the present framework explicitly integrates symmetric and asymmetric fuzzy rules to address real-world environmental asymmetries, such as turbulence, irregular pollutant distributions, and sensor noise, offering a dual-rule mechanism to stabilize backward estimation problems in UAV-based air quality monitoring.

The novelty of this work lies in bridging this gap by introducing a UAV-based hybrid fuzzy inference system that explicitly combines symmetric and asymmetric fuzzy rules. Symmetric rules represent baseline environmental stability, while asymmetric rules adaptively respond to disturbances such as turbulence and localized emissions. This dual framework enhances the interpretability, stability, and adaptability of real-time monitoring systems under uncertain conditions.

The contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

Development of a UAV-based hybrid fuzzy inference framework integrating symmetric and asymmetric rules for robust pollutant reconstruction;

Demonstration of improved reconstruction accuracy under environmental disturbances and sensor noise;

Validation of the methodology through indoor, urban, and desert field experiments;

Discussion of the framework’s potential applications in urban planning, policy making, and scalable air quality monitoring.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the principles of gas sensors and their relation to air quality indicators.

Section 3 describes the overall system architecture and operating principles.

Section 4 details the fuzzy logic model and prototype design, including hardware and software units.

Section 5 presents simulation and field-testing results comparing symmetric and asymmetric inference across varying conditions.

Section 6 discusses potential improvements, applications, and integration with advanced data processing techniques. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the study and outlines directions for future development.

2. Overview of the Theoretical Basics

2.1. Examined Pollutants & Related Health Hazards

The atmosphere is composed mainly of nitrogen (78%), oxygen (21%), and trace gases, including carbon dioxide (CO

2), sulfur dioxide (SO

2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO

2). These gases, while naturally occurring, can reach hazardous levels due to anthropogenic activities—especially fossil fuel combustion, industrial emissions, and transportation [

61,

62]. Monitoring their presence and behavior is critical for assessing environmental and public health risks [

1,

2,

63].

From a fuzzy control perspective, each pollutant represents a distinct input variable with asymmetric characteristics in time, space, and source behavior. For instance, CO

2 concentrations may gradually rise indoors due to poor ventilation, while NO

2 levels fluctuate rapidly in areas with heavy traffic [

16,

17]. This non-uniformity introduces a functional imbalance that must be explicitly addressed in the control system.

Carbon dioxide (CO

2): A dense greenhouse gas associated with cognitive impairment and respiratory effects [

63,

64,

65,

66]. Indoor levels often exhibit slow, accumulative asymmetry, requiring soft thresholds for responsive ventilation control [

17,

18]. Sulfur dioxide (SO

2): Emitted from industrial processes, it causes acute health effects and contributes to acid rain [

67,

68,

69,

70]. Emission patterns may create sharp, localized peaks, necessitating asymmetrical fuzzy responses [

16,

69]. Nitrogen dioxide (NO

2): A common byproduct of vehicle exhaust, with highly variable exposure profiles [

71,

72]. Effective control demands context-sensitive modeling due to its strong spatio-temporal asymmetry [

16,

17]. Therefore, the pollutants themselves constitute asymmetric variables, underscoring the need for adaptive, non-uniform fuzzy rule structures in any effective monitoring system.

2.2. Air Quality Index (AQI) & Standardization

The AQI aggregates pollutant concentrations into a unified scale that helps communicate health risks.

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 summarize standard AQI thresholds for NO

2, SO

2, and CO

2 based on U.S. EPA guidelines [

62,

73,

74]. However, while AQI thresholds provide standardized references, the way pollutant concentrations cross these thresholds is often asymmetrical—a slight increase in NO

2 may lead to disproportionate health effects in vulnerable populations [

72]. This implies that fuzzy set modeling of pollutant severity should not be symmetric around a midpoint, but rather be biased or weighted according to real-world risk gradients. Hence, asymmetric fuzzy membership functions can better capture the nonlinear health-impact profiles of different pollutants, thereby improving the interpretability and responsiveness of the monitoring system [

12,

13,

14,

15,

21].

Hence, asymmetric fuzzy membership functions can better capture nonlinear health impact profiles, directly linking AQI evaluation to the broader framework of symmetry/asymmetry in fuzzy control.

2.3. Applied Sensors

The system incorporates metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) sensors, which produce voltage outputs based on gas concentration:

MQ-135—CO

2 detection [

75]

MG-811—NO

2 detection [

76]

2SH12/MQ136—SO

2 detection [

77]

These sensors provide analog readings that are subject to inherent noise and drift. Traditional binary or linear thresholding would fail under such uncertainty. Here, fuzzy logic enhances interpretation, and asymmetry in fuzzy preprocessing rules allows different sensor types to be evaluated based on their specific uncertainty profiles and sensitivities [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

This variability represents a form of hardware-level asymmetry, which is explicitly modeled in the fuzzy rule base to ensure resilience and precision. This is also modeled in the fuzzy rule base to ensure resilience and precision.

2.4. Fuzzy Control Perspective in Air Quality Monitoring

Environmental systems are not only uncertain but fundamentally asymmetric in structure and dynamics. Fuzzy logic enables the transformation of imprecise sensor data into actionable classifications using linguistic terms (e.g., “low,” “moderate,” “high”) [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Key benefits include the following:

Adaptive control of ventilation and alert systems under varying pollutant loads.

Real-time handling of sudden spikes (e.g., NO2 from vehicles).

Multi-input integration for compound AQI assessment across pollutants with distinct temporal dynamics.

To manage this complexity, we leverage the following:

Symmetric fuzzy rule sets for routine conditions—offering interpretability and balanced control across gas types.

Asymmetric fuzzy rule structures for exceptional or high-risk scenarios—enabling the system to prioritize specific pollutants based on their risk profile or dynamic behavior (e.g., sharp SO2 increases near industrial zones).

The dual application of symmetry and asymmetry within fuzzy control enables a resilient, context-sensitive assessment of air quality. Symmetric rules provide efficiency and balance under typical conditions, while asymmetric rules introduce flexibility for outliers and high-risk cases. This balance directly reflects the theme of symmetry/asymmetry in fuzzy control for complex, real-world monitoring systems.

2.5. Mathematical Formulation of the Backward Problem

Monitoring air quality using sensors mounted on UAVs can be viewed as a backward (inverse) problem. The forward problem involves understanding the physical spread of pollutants in the air, where a concentration field

c(x,t) evolves based on transport–diffusion dynamics in the following way:

where

D is the diffusion coefficient,

u is the wind velocity field, and

S(x,t) represents local emission sources.

The UAV-mounted sensors provide discrete, noisy measurements of pollutant concentration as follows:

where

is the forward observation operator mapping the continuous field

c(x,t) to sensor outputs, and

εi represents measurement noise and UAV-induced disturbances.

The inverse problem then consists of reconstructing an estimate or a scalar AQI from incomplete and uncertain sensor data {yi}. This inverse problem is ill-posed in the traditional sense:

Small perturbations in the input (εi) may lead to significant deviations in the reconstruction;

Pollutant distributions are typically non-uniform and strongly influenced by asymmetric factors such as turbulence, altitude, or localized emissions.

2.6. Role of Symmetry and Asymmetry

Traditional models often assume a symmetric distribution of pollutants, i.e., smooth spatial or temporal variation around an equilibrium. This assumption corresponds to symmetric membership functions in fuzzy inference, in which deviations from thresholds are treated equally in both directions. However, real-world conditions are often dominated by asymmetry: localized peaks of SO2 near industrial zones, sharp fluctuations of NO2 from traffic, or gradual accumulation of CO2 in poorly ventilated environments. Hence, symmetric fuzzy rules provide a baseline solution suitable for stable, quasi-equilibrium conditions, while asymmetric fuzzy rules act as a regularization mechanism, explicitly accounting for environmental disturbances. This duality not only stabilizes AQI estimation against noise and uncertainty but also operationalizes the conceptual framework of symmetry/asymmetry within fuzzy control.

2.7. Fuzzy Logic as Regularization of the Backward Problem

Instead of solving the backward problem through deterministic optimization, a fuzzy inference system (FIS) is introduced as a regularised mapping as follows:

where

Ffuzzy integrates both symmetric and asymmetric rule sets.

For symmetric rules, the logic is as follows:

capturing balanced dependencies and ensuring interpretability.

The asymmetric rules have the following logic:

shifting decision boundaries in response to asymmetric environmental conditions.

This formulation highlights how the proposed hybrid fuzzy controller converts noisy and incomplete inputs into consistent outputs, effectively regularizing the challenging backward problem of pollutant estimation.

The contribution of this work lies in bridging the following:

Symmetry in mathematical modeling—symmetric fuzzy rules represent equilibrium and stability.

Asymmetry as perturbation—asymmetric rules restore robustness under non-ideal conditions.

Backward problem methodology—fuzzy inference provides a practical, real-time simulation method for solving inverse problems in environmental monitoring.

Recent studies have investigated the application of UAVs for collecting high-resolution environmental data. Low-cost sensing platforms enable dense spatial mapping, but their performance is affected by sensor nonlinearity and environmental variability [

2,

3,

4,

5,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Fuzzy logic has been applied to air quality assessment to manage uncertain and noisy sensor data [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, only a few approaches explicitly formalize symmetry and asymmetry in fuzzy control as a stabilizing mechanism for ill-posed backward problems in pollutant estimation. The proposed framework builds upon these works by formalizing symmetric and asymmetric membership functions to enhance robustness in practical UAV deployments.

Compared with classical linear or threshold-based AQI estimation, the hybrid FIS generalizes across non-linear and asymmetric sensor responses, providing a mathematically stable reconstruction even when environmental conditions deviate from equilibrium. Symmetric rules capture baseline dynamics, while asymmetric rules correct for localized perturbations.

2.8. The UAV Control via Fuzzy Logic

The UAV’s flight parameters, including altitude, speed, and trajectory adjustments, are governed by a fuzzy inference system (FIS) that interprets the measured pollutant concentrations. Symmetric rules handle stable baseline environmental conditions, while asymmetric rules react to localized anomalies, such as sudden increases in pollutant levels or sensor noise.

For instance, if CO

2 concentration rises rapidly, the FIS can command the UAV to ascend or modify its path to map pollutant distribution more effectively. Each fuzzy set is defined numerically using triangular or trapezoidal membership functions, and representative rules are summarized in

Section 5.4. Weighted firing strengths are applied based on the degree of asymmetry, ensuring that local anomalies trigger appropriate UAV control actions.

This approach allows the UAV to adapt dynamically to environmental variations, maintain measurement accuracy, and safely navigate through areas with heterogeneous pollutant distributions, without requiring visual illustrations for clarity.

2.9. FIS Output and Symmetry/Asymmetry Calculation

The hybrid FIS computes UAV control actions and air quality estimations using the degree of membership of pollutant concentrations and the symmetry index.

2.9.1. Fuzzy Rule Evaluation

Each fuzzy rule is expressed as:

where

Xj is the input variables representing pollutant concentrations (e.g., NO

2, SO

2, CO

2, measured in ppm or ppb);

Aj is the fuzzy sets describing linguistic terms such as

Low, Medium, or

High;

Y is the output linguistic variable, representing UAV control actions (e.g., altitude adjustment, path correction); and

B is the output fuzzy set.

The firing strength of each rule is computed via the min operator for AND operations:

where

is the degree of membership of the input value

Xj in the fuzzy set

Aj.The

max operator then obtains the aggregated output membership function:

Finally, the crisp output value (e.g., UAV altitude change in meters or throttle correction in %) is computed using the centroid defuzzification method:

This process ensures smooth control transitions and avoids abrupt UAV maneuvers under fluctuating air quality conditions.

2.9.2. Symmetry/Asymmetry Index Calculation

To account for environmental anomalies (e.g., local emissions or sensor disturbances), a symmetry index

S is defined for each input variable:

where

X is the current pollutant concentration,

is the mean of historical concentrations, and

is the standard deviation of historical data.

This index quantifies deviation from baseline conditions:

To enhance system responsiveness, the degree of asymmetry

Da is computed as:

and is used to weight the rule activation strength:

This adaptive weighting increases the influence of asymmetric rules when anomalies are detected, ensuring the UAV reacts promptly to abnormal pollutant spikes or sensor noise.

2.9.3. AQI Calculation

For each pollutant

p, the Air Quality Index (AQI) is determined using the standard piecewise linear interpolation.

where

Cp is the observed concentration of pollutant

p, CLo, CHi are lower and upper breakpoint concentrations for

p, and

ILo, IHi are corresponding AQI index values (e.g., 0–50 for

Good, 51–100 for

Moderate).

The overall air quality index is defined as the maximum among pollutants:

This ensures that the dominant pollutant determines the final air quality warning for the area under observation, in line with international AQI standards.

The combined use of fuzzy rule evaluation, symmetry-weighted adaptation, and AQI computation allows the UAV to perform real-time, context-aware air quality mapping with enhanced robustness to disturbances.

While the symmetry index addresses dynamic variations in environmental conditions, an additional entropy-based weighting is introduced to account for the reliability of sensor data.

2.10. The Entropy Method

To complement the symmetry-based adaptation, the entropy method quantifies the uncertainty of sensor measurements. The entropy method is employed to quantify the uncertainty of the sensor measurements, providing a numerical basis for weighting each sensor’s contribution to the fuzzy inference system (FIS). For each pollutant

j, the entropy is calculated as:

where

pij is the normalized value of the i-th observation for pollutant

j, calculated as follows:

n is the total number of observations.

The normalization factor k ensures that Ej ∈ [0, 1], making entropy values comparable across datasets of different sizes. Higher entropy values indicate more uncertain or evenly distributed sensor measurements, while lower values indicate more informative and consistent readings.

To incorporate these values into the fuzzy inference system, the entropy values are transformed into weights:

where w

j is the weight assigned to the j-th sensor input. Sensors with higher information content (lower entropy) are given higher weights, allowing the FIS to prioritize reliable measurements during pollutant reconstruction. This entropy-based weighting improves the overall accuracy of the UAV-based air quality monitoring system without requiring a schematic illustration.

3. The System Architecture & Operation Principle

The proposed system comprises both hardware and software units, which integrate into a unified framework for real-time air quality monitoring. The hardware unit includes two major components: (i) the sensor module, which measures gas concentrations (NO2, CO2, SO2), as well as temperature and humidity; and (ii) the UAV platform, which enables mobile deployment and variable-altitude sampling. The software unit features a fuzzy-logic engine that combines symmetric and asymmetric rule sets to calculate the Air Quality Index (AQI). Symmetric rules capture balanced, steady-state conditions (e.g., stable pollutant levels), while asymmetric rules adaptively respond to deviations caused by turbulence, localized emissions, or other disturbances. This integration ensures robustness of the monitoring process in both equilibrium and perturbed environments. Additionally, a local storage and communication module ensures data reliability even during temporary connectivity loss.

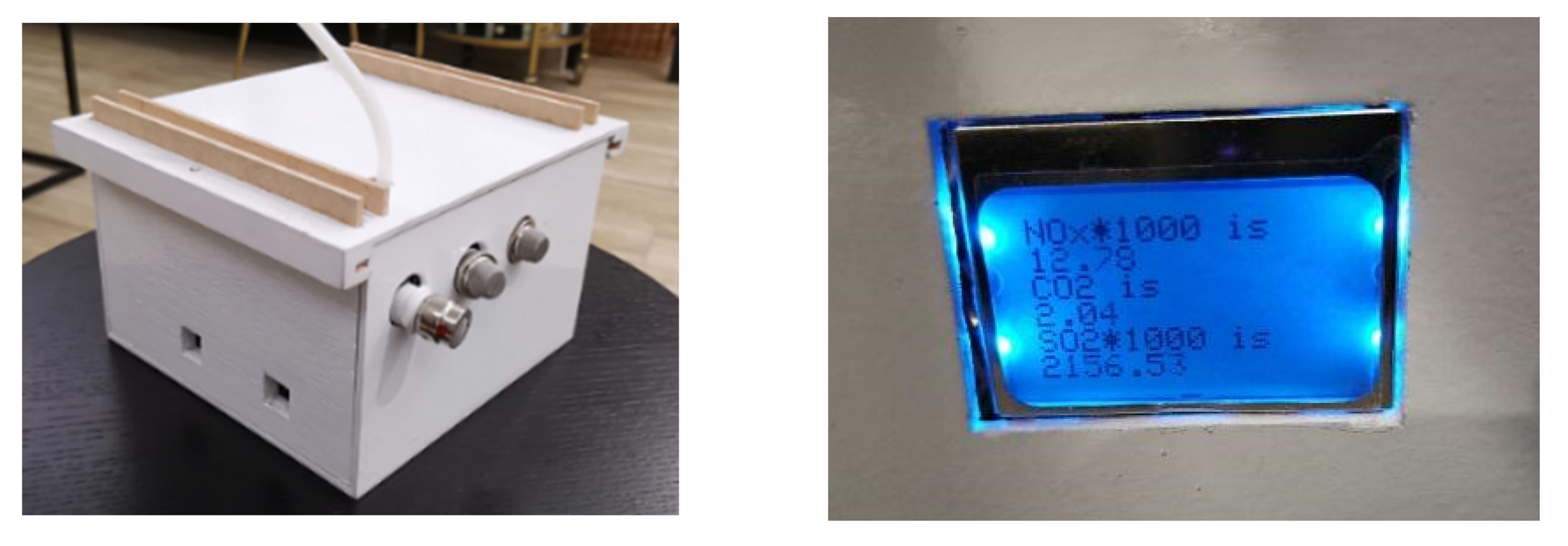

Figure 1 illustrates the operational flow of the developed air quality monitoring system, designed for both stationary and mobile configurations. In the mobile configuration, the monitoring module is mounted on a UAV, allowing for remote sensing across various altitudes and areas. In stationary mode, the same process can be executed locally, excluding the UAV component but retaining full sensing and fuzzy processing capabilities.

The operational cycle begins with the definition of a target inspection area. Once the UAV reaches the designated location, the data acquisition loop is initiated and runs continuously throughout the monitoring session. Individual measurements from the NO2, CO2, and SO2 sensors are first collected. These sensors generate analog voltage signals proportional to gas concentrations. The signals are processed by a microcontroller (Arduino) on the drone’s circuit board, which converts them into standardized values in parts per million (ppm) or parts per billion (ppb).

The microcontroller simultaneously coordinates three subsystems: (i) data acquisition, (ii) wireless transmission, and (iii) data display. On the UAV side, measurements are stored on an SD card to prevent loss in the event of communication failure. Gas concentration values are also displayed on an integrated LCD screen. In parallel, data is wirelessly transmitted to the user-side circuit, where a second microcontroller evaluates the incoming data against established thresholds and displays the results on a TFT touchscreen interface.

An additional feature allows the user to activate an air pump remotely via the interface. This pump collects a physical air sample from the monitored zone for laboratory analysis. Once the sample is obtained, the pump automatically deactivates, and the data-acquisition loop concludes, marking the end of the monitoring session.

Throughout the entire operation, the system ensures direct user involvement—from defining the inspection location to initiating measurements and managing sample collection. Upon completion, the UAV autonomously returns to the user, allowing redeployment in another target area. This iterative workflow enables flexible, user-guided monitoring with real-time visualization and archival storage, fostering a more comprehensive and context-sensitive understanding of local air quality conditions.

4. Fuzzy Logic Model & System Design

The proposed system design provides a platform for real-time air quality monitoring under varying environmental conditions. It is explicitly designed to address real-world asymmetries arising from heterogeneous sensor behavior, fluctuating gas concentrations, and dynamic operational settings. These asymmetric characteristics create uncertainties and nonlinearities in the data, which justify the application of fuzzy control strategies in subsequent processing stages.

4.1. Fuzzy Logic Concept

The system provides a physical platform for acquiring air quality data in environments characterized by asymmetry and uncertainty. Accordingly, a fuzzy interpretation of asymmetric sensor data is essential to support the application of asymmetric fuzzy rules. The heterogeneous nature of the chosen sensors—each employing different detection methods, ranges, and sensitivities—leads to inconsistent and occasionally contradictory readings. Moreover, fluctuations in altitude, temperature, and wind patterns during UAV operation introduce another layer of dynamic inconsistency to the monitoring process.

To manage these conditions, a methodology is required that can handle ambiguity, partial truths, and nonlinearity. Fuzzy logic, incorporating both symmetric and asymmetric rules, is employed as a natural extension of the monitoring framework. Its ability to interpret imprecise and uncertain inputs makes it particularly effective for air pollution data. Thus, fuzzy inference systems are applied to derive meaningful assessments from raw sensor values, improving the decision-making capabilities of the monitoring solution.

The fuzzy inference system is structured around two categories of rules:

Symmetric rules: IF [sensor condition A] THEN [AQI state B], reflecting stable and regular dependencies in data.

Asymmetric rules: IF [sensor condition A] AND [disturbance C] THEN [modified AQI state B’], capturing environmental asymmetries and exceptions.

By combining these two classes, the system effectively models both equilibrium (symmetry-preserving) and perturbed (symmetry-breaking) conditions, leading to more reliable AQI estimation.

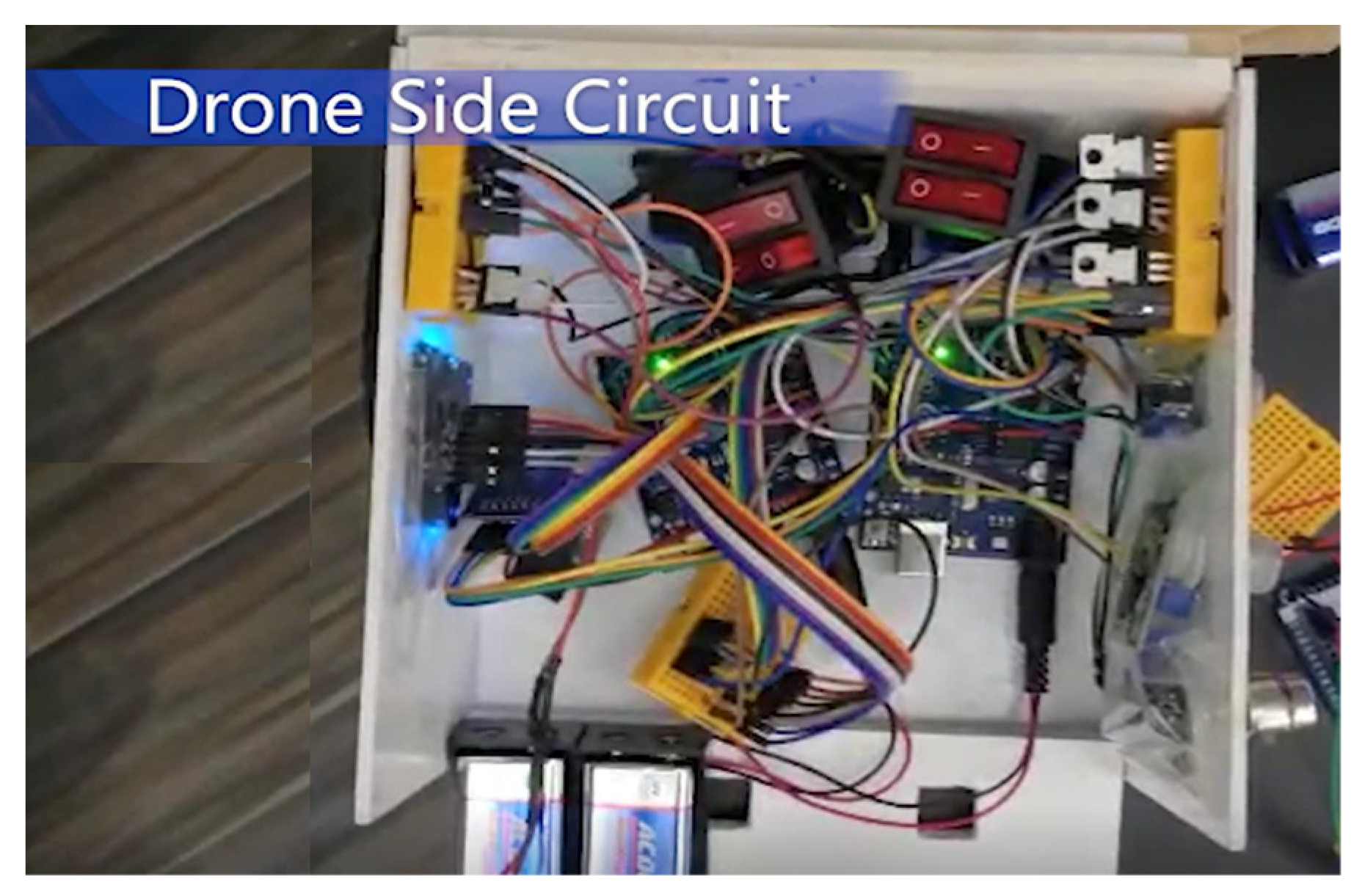

4.2. Design of Hardware Unit—Drone Side Circuit

This module examines the following aspects:

A medium-sized UAV was selected after evaluating options based on size, stability, payload, and compatibility. This drone enables remote monitoring of emissions and is particularly beneficial for inspecting hazardous locations. Ensuring stable flight control, reliable data logging, and efficient wireless transmission were essential requirements. Numerous studies have examined the advantages and drawbacks of UAVs, focusing on factors such as cost, weight, speed, flight time, capacity, and safety [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83]. After evaluation, the DJI Phantom was selected as the monitoring platform (

Figure 2).

The cost of the UAV is about USD 700, with the following specifications: weight 1.21 kg (0.84 kg excluding the camera), maximum ascent 5 m/s, maximum descent 3 m/s, maximum speed 16 m/s, flight duration ~25 min, hover accuracy ±1.5 m (horizontal) and ±0.5 m (vertical), diagonal size 350 mm without propellers, battery 4480 mAh Li-Po 4S, operating temperature 0–40 °C, maximum altitude 6000 m, reliable and safe operation [

84]. To install the monitoring circuit, the onboard camera was removed.

Sensors: MQ135 (CO2), MG-811 (NOx), 2SH12 (SO2).

Two Arduino Uno boards (control and data conversion).

MicroSD module (storage).

NRF24L01 module (wireless communication).

Air pump (sample collection).

Nokia 5110 LCD (onboard display).

Additional components (resistors, capacitors, regulators, power supplies, motor driver).

The upper Arduino processes sensor data, converts voltages to parts per million (ppm) or parts per billion (ppb), and outputs the data to both the LCD and SD storage. The lower Arduino handles transmission and controls the air pump. The circuit is housed in a lightweight wooden unit (total weight with components: 1.0 kg). Removing the DJI camera compensated for payload limitations.

This UAV model provides the required mechanical stability and payload capacity, enabling the airborne unit to operate effectively under asymmetric environmental conditions, such as fluctuating wind, temperature, and pressure. These variations affect sensor behavior, underscoring the need for robust fuzzy-based interpretation.

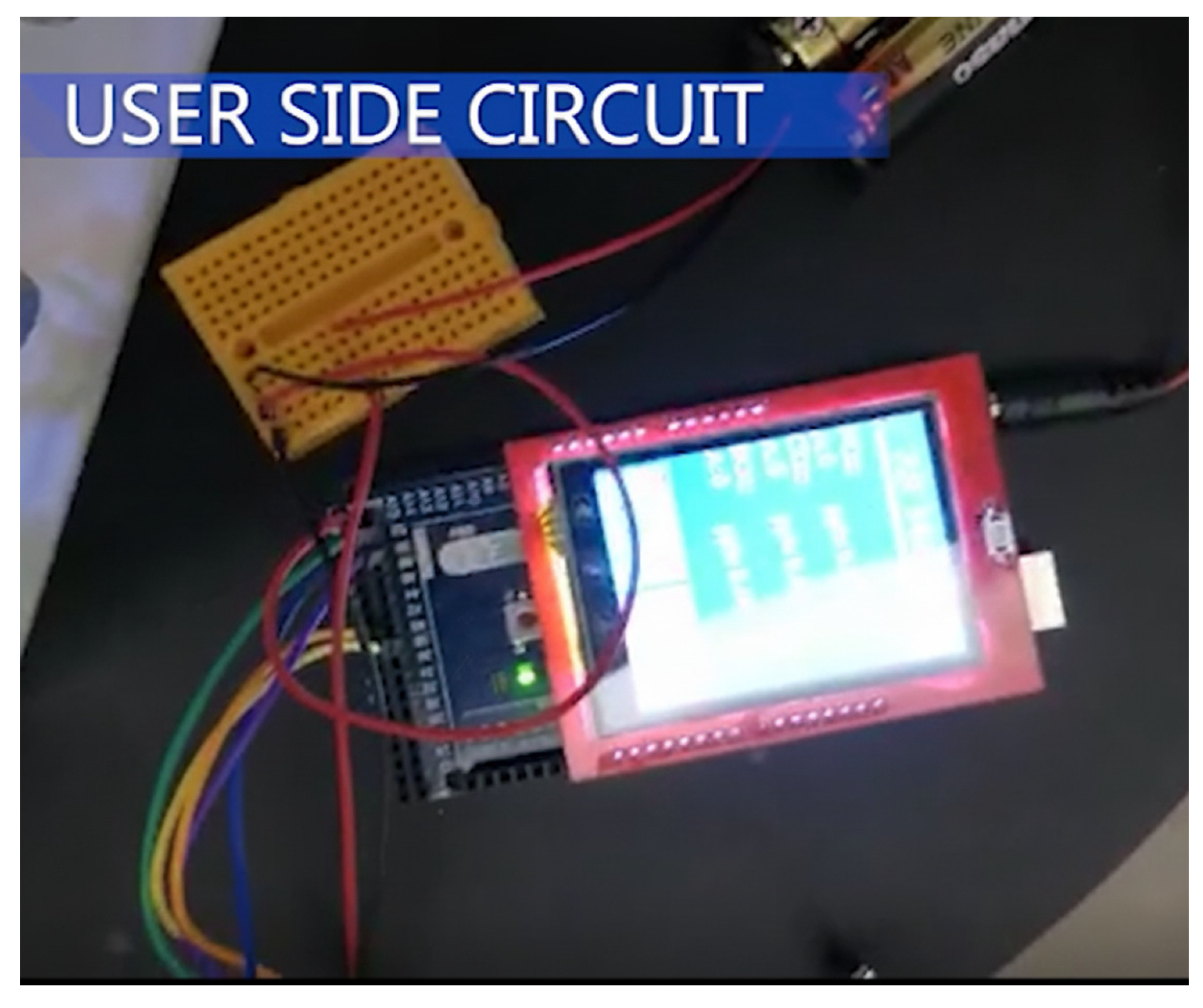

4.3. Design of Hardware Unit—User Side Circuit

The user-side circuit tracks transmitted sensor data and manages the air pump for remote sampling. It includes the following:

Arduino Mega (central controller).

NRF24L01 module (wireless communication).

2.4″ TFT touchscreen (interface, pump activation, and results display).

Power sources.

The design (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) features a housing with a touchscreen interface for user interaction and accessible troubleshooting. A lightweight wooden casing was chosen for safety and durability.

By design, the UAV-mounted sensors (CO2, NOx, SO2) exhibit different sensitivities and calibration requirements, introducing asymmetric uncertainties. These cannot be managed effectively by threshold-based methods, further motivating the integration of fuzzy control to interpret nonlinear responses.

4.4. Design of Software Unit

The software unit manages programming, testing, and system operation. It enables hardware operation, data processing, and storage.

The Arduino IDE [

85] is used for programming and monitoring microcontrollers. Serial ports allow real-time observation of microcontroller behavior, while the serial plot function visualizes initial sensor data (CO

2, SO

2, NO

2).

Data is logged to the microSD and stored in Microsoft Excel [

86], which provides easy readability and compatibility with analysis tools. Excel enables further manipulation of ppm/ppb values and integration with other programs.

Future development could integrate advanced GUIs and dedicated fuzzy inference engines for real-time interpretation. This would enable robust handling of sensor uncertainties resulting from environmental variability.

4.5. Design Cost

The prototype design emphasizes the monitoring system rather than the UAV itself. The estimated system cost is approximately USD 350, making it affordable for individuals, with options for both stationary and UAV-mounted use. A medium-sized UAV costs approximately USD 1400, while rental is USD 550–700, including housing and testing. Future efforts may focus on integrating low-cost UAVs into the monitoring system or on applications in professional sectors, such as agriculture or energy facilities, though these would require larger investments.

In asymmetric monitoring environments (e.g., industrial zones), fuzzy logic significantly improves interpretation accuracy. This approach remains cost-effective compared to traditional calibrated systems, making it practical for small-scale and uncertain real-world scenarios.

5. Field Experiments

The testing phase was crucial for evaluating how the system performs in realistic environments that inherently exhibit asymmetry—in sensor response behavior, the spatial distribution of gases, environmental conditions (e.g., wind turbulence), and technical constraints. These irregularities and uncertainties complicate deterministic analysis and motivate the integration of fuzzy logic in the future to achieve a robust interpretation of results.

Field trials were conducted in diverse environments, including urban and desert areas. The UAV-enabled system successfully measured pollutant levels while compensating for turbulence, altitude variations, and irregular pollutant distributions. Key observations include the following:

- (1)

Symmetric rules alone provided stable results under controlled conditions.

- (2)

Asymmetric rules significantly improved accuracy when environmental symmetry was disrupted (e.g., during sudden wind gusts).

- (3)

The hybrid approach maintained reliable AQI calculations even under noisy sensor conditions.

A detailed discussion of the system implementation and testing results is provided below.

5.1. Testing Hardware Unit

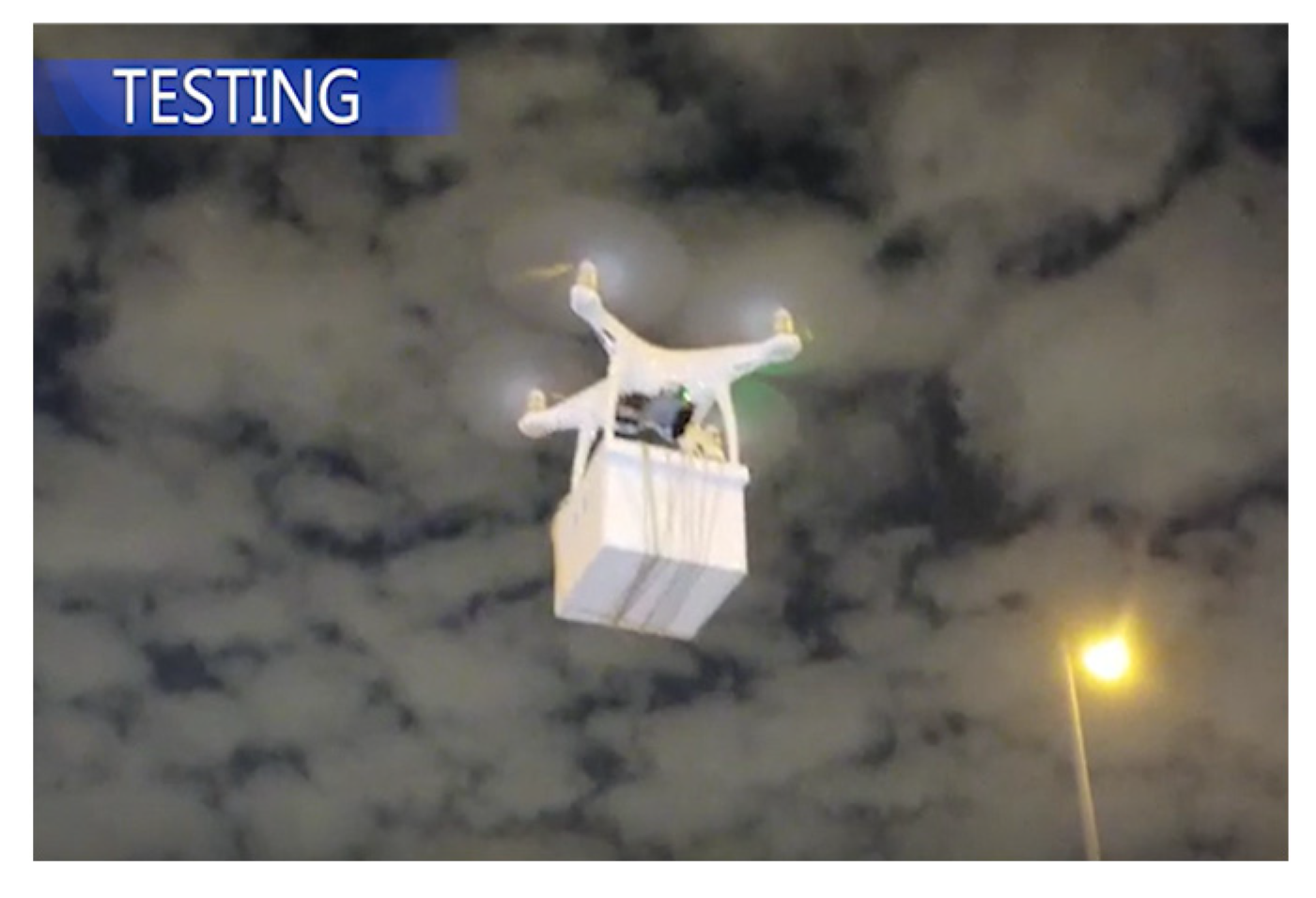

The hardware unit comprises both the user-side circuit and drone-side circuit designs (

Section 4). Testing of the system’s operation focuses on a drone flight and the performance of its sensors.

The layout and weight distribution of components significantly impact the drone’s flight stability, particularly under asymmetric external conditions, such as gusty winds or uneven loading. These uncontrolled factors introduce real-world variability that cannot be modeled deterministically, which supports the argument for incorporating fuzzy control logic to interpret system behavior in such dynamic settings.

Once the drone’s side circuit is attached to the drone’s housing unit, flight stability is tested. This is a crucial consideration for the system’s safe and reliable operation. The total weight is around 0.6 kg, as mentioned before. The average lifting capacity of medium-sized drones ranges from 1.2 kg to 1.5 kg. Any extra load will cause many unexpected and unintended flight abnormalities. Thus, the selection of the housing unit’s shape and the distribution of its internal weight are important considerations. For instance, the unit’s shape must withstand high-speed wind impacts (minimizing risks) that could compromise the drone’s control and operation. The layout of electric circuits within housing units must be optimized to maintain the drone’s balance, but high-speed winds may still affect its stability. At the same time, the drone (existing end-product) has been integrated into the proposed system, which provides additional design advantages, particularly by accounting for aerodynamic issues specific to the drone (an in-built feature that reduces the adverse effects of high-speed winds). The high-speed wind, especially in desert areas, caused unpredictable deviations in drone balance. These unpredictable aerodynamic disturbances represent a real-world asymmetry that underscores the need for adaptable, soft-computing methods in future implementations.

Testing drone flights has encountered challenges. Attempts at flight, particularly when the housing unit is attached to the drone (which houses the circuit), have proven challenging. The added weight has increased the drone’s power consumption, with power usage rising by approximately 65–70% during takeoff compared with standard flight conditions without any added load, where the drone typically consumes about 40% of its energy. The highest altitude reached during the flight was roughly 20 m. Technically, it could have achieved greater heights and the majority of flight testing has been conducted in isolated locations at lower altitudes. The typical flight duration has been about 20 min (up to 25 min, as specified by the drone), but it is shorter in urban areas. The minimum operational time for the drone’s side circuit was approximately 2 h, assuming the batteries were fully charged initially. For the user-side circuit, the operational time should be slightly longer, given its components’ lower energy use. Thus, the operational duration of the circuit is influenced by the frequency of system use and the energy consumption and distribution of its components. To gather more flight data, testing was carried out in a desert environment (with specific conditions). However, wind became a critical factor during these tests, as it was significantly stronger than in urban settings, highlighting issues with the housing unit’s construction. An example of the drone’s flight during testing is shown in

Figure 9.

In summary, the drone struggles to maintain balance in high winds. Due to the absence of a specialized instrument, accurate wind speed measurements could not be recorded. Nevertheless, based on experiential testing, it can be stated that in urban areas, wind speeds ranged from levels 2 to 4 (1.6–7.9 m/s), and in the desert, from levels 5 to 7 (8–17.1 m/s) according to the Beaufort wind scale [

87]. It is important to note that the landings and takeoffs were reasonably stable with minimal movement across the horizontal axis (in low-speed winds).

The sensor response varied significantly with gas concentration and type. For example, low concentrations of NO2 and SO2 were below detection thresholds, whereas high concentrations produced reliable spikes. This non-linear, threshold-sensitive behavior results in non-symmetric sensor performance. Thus, binary or linear interpretations fail to capture nuances in gas exposure—a gap that fuzzy modeling can address by assigning degrees of presence rather than fixed thresholds.

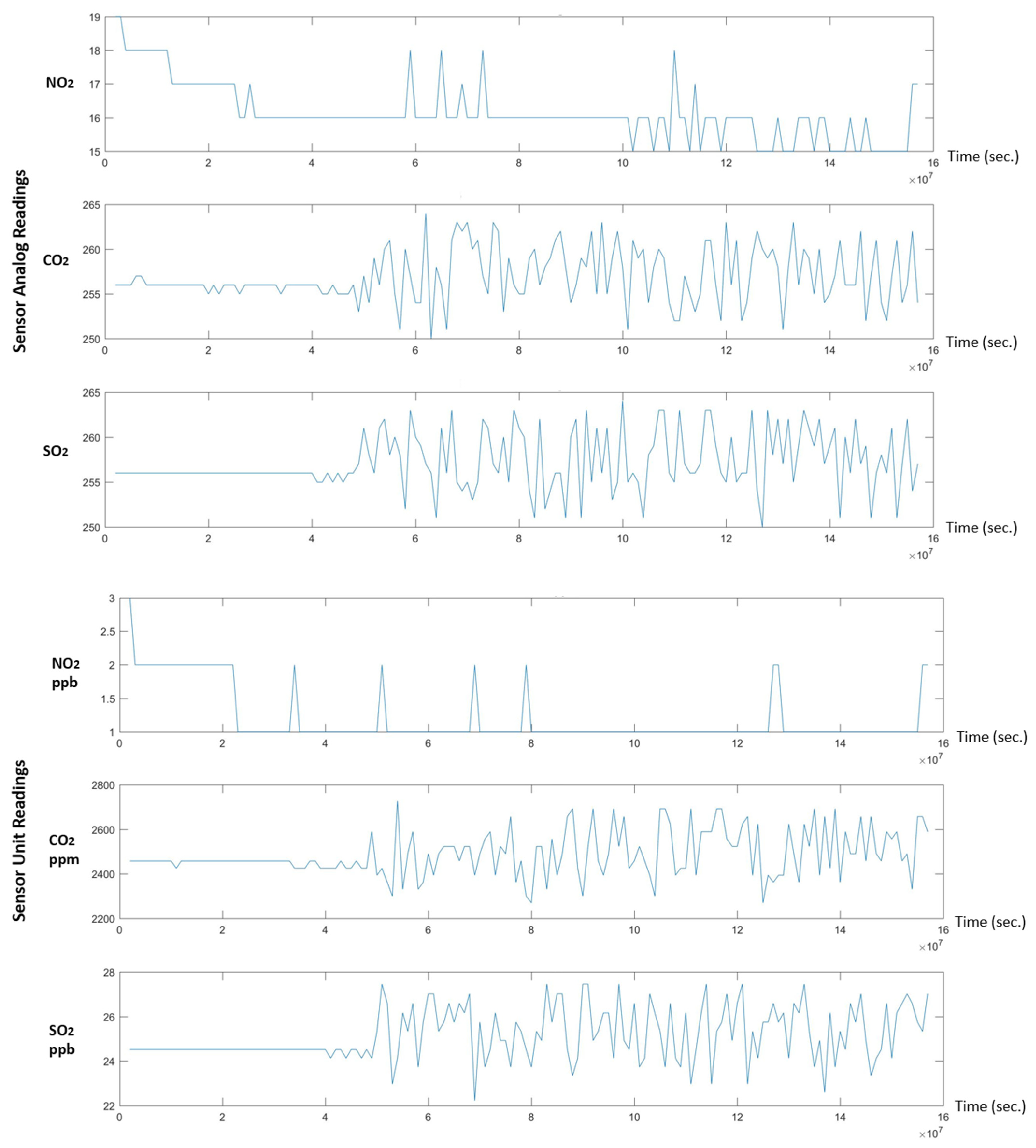

The sensor’s effectiveness is evaluated based on the collection of precise and trustworthy data. To ensure data accuracy, it is essential to establish a correlation between measured gas concentrations and the Air Quality Index (AQI) standards. The analog readings of the detected gases responded predictably: a spike in gas release led to a swift rise in the values upon contact. However, the initial transition from analog values to ppm/ppb values encountered challenges. For example, NO

2 and SO

2 readings were approximately 40% lower than anticipated, while CO

2 readings were 20% higher than expected. To address these issues, the sensors were recalibrated using a device known as “ToxiRAE” [

88], along with facilities from power plants that provided canisters and compartments with fixed gas concentrations, and applying specific mathematical formulas. This recalibration process required time due to the identified discrepancies. The following observations were made: in instances of high gas concentration levels, such as abnormal spikes or significant leaks, the chemiresistor effectively met the monitoring requirements, suggesting its suitability for detecting analog values. Nevertheless, the chemiresistors do not demonstrate sufficient reliability for precise ppm/ppb measurements. The sensors were configured for testing within a designated ppm/ppb range. For instance, the NO

2 ppb readings fluctuated between 1 and 10, confirming that the chemiresistors were operating adequately. A significant limitation of the modified sensors is their design constraints, which prevent them from measuring low concentrations of NO

2 and SO

2. After conducting several tests, the concentrations of NO

2 and SO

2 were insufficient to elicit a proper analog response from the sensors, resulting in 0% accuracy due to the absence of a detectable signal.

Table 4 summarizes the results of hardware design testing. For more details, refer to the explanation part.

5.2. Testing Software Unit

A performance evaluation of the software unit has been conducted based on its capabilities to capture readings, interpret data, and present results.

The following indicators—speed, transmission capability, and ease of use—have been selected for data-acquisition testing. To conclude, under a short range between both circuits of up to 5 m, the data transmission time could be considered as satisfied, where the time delay does not exceed approximately 10 ms on average. However, as this range increases, significant delays occur due to the NRF24L01 module’s limited transmission range. For instance, the wireless radio frequency band has a short range (a limited wavelength), and there is potential interference from nearby objects due to the limited range between the circuits while monitoring pointed spots. Unfortunately, the exact data could not be captured physically when the drone’s side circuit is located in the air. In practice, a range of 20–50 m is recommended, but it can reach up to 200 m.

Wireless transmission is also affected by asymmetric physical obstructions, dynamic distances, and environmental interference. These factors make communication stability non-uniform, varying from test to test. A fuzzy-based communication assessment model could be beneficial for future upgrades to dynamically evaluate signal quality, rather than relying on static thresholding.

The drone features a data logging option that utilizes a removable SD card, located on the side of the device. The SD card currently has a storage capacity of 64 GB. Nevertheless, any standard-sized SD card can be used, as the system is compatible with standard-sized cards. Due to specific hardware and software constraints, readings are recorded approximately once every second, although enhancements could enable faster recording rates. The micro-SD module reads and writes data to the SD card, ensuring continuous accessibility and providing a dependable storage alternative. However, the drone’s maximum flight duration is limited, which may require recharging the drone, during which data logging is not possible.

The analog sensor data, when logged and visualized, revealed non-linear response curves and inconsistent behavior across conditions. Traditional deterministic processing requires multiple case-specific models. In contrast, fuzzy control strategies can generalize across a broader range of inputs, accommodating these uncertainties with less complexity.

If required, the air sample could be collected in an inspected area. The user must activate the air pump on the drone’s side circuit to initiate the collection process. The retrieval of the air samples has been easy during the testing of this data acquisition method.

To facilitate usability, each circuit side includes a display to track NO

2, SO

2, and CO

2 emissions. The LCD screen on the drone’s circuit provides this feature during stationary monitoring (which does not require the drone to be in operation) or when the drone is on the ground (

Figure 5). On the user side, the TFT screen displays the emission levels, continuously updating the information (

Figure 8). There are two primary buttons: “Activate Air Pump” and “Air Quality Info.” Pressing the first button activates the pump to collect air samples, while the second button displays air quality details based on the measured gas readings.

Next, let us review and discuss the real-world testing results of captured readings of the examined gases, along with their impact on human health.

5.3. Real-Life Testing Results

The real-life testing further revealed spatial asymmetry in gas distribution, with air pollutant concentrations varying not only between indoor and outdoor locations but also with altitude and environmental factors (e.g., cooking). The disparity in readings, especially for CO2, ranged by over 45 times across the vertical range (e.g., 464 ppm vs. 21,075 ppm), underscoring the need for a control model capable of handling heterogeneous, spatially skewed data—such as fuzzy inference systems.

The following monitoring spots have been considered:

Local (stationary) indoor—kitchen while cooking (

Figure 11);

Local (stationary) outdoor—urban area (

Figure 12);

Remote outdoor—urban area, when the drone is located at 5 m altitude from the ground (

Figure 13) [

89].

The results are presented below; each figure shows readings in both analog and ppm (CO2) or ppb (NO2, SO2) for the monitoring spots mentioned above.

The captured NO

2 and SO

2 readings have been used to evaluate the AQI at the inspected sites. The AQI online calculator has been applied for this purpose [

90] in addition to the standardization scale given in

Table 1 and

Table 2. However, CO

2 gas readings have been evaluated against the standard scale shown in

Table 3 [

62].

Based on NO

2 and SO

2 gas readings, the following has been observed (detailed data given in

Table 5) [

89]:

For indoor monitoring spots such as the bedroom and kitchen, the bedroom has the highest SO

2 ppb value, leading to the highest AQI–35 as compared to the kitchen monitoring results–32 (almost the same range), but both present good AQI levels with respect to the standard values given in

Table 2. The NO

2 readings are low, indicating a good AQI level per the standard levels in

Table 1.

For outdoor monitoring spots, such as urban areas at 5 m altitude, we can observe the highest SO2 ppb value, resulting in an AQI of 46 for metropolitan areas, compared to spots at 5 m altitude, where the AQI is only 4. The NO2 ppm value is highest in the urban area at 5 m altitude (AQI is 30), and in the metropolitan area, AQI is only 10, but both indicate good AQI levels.

Analyzing all readings, the highest SO2 ppb value is observed in the urban area (AQI is 46), while the lowest is in the urban area at 5 m altitude (AQI is 4). The highest NO2 ppb value is detected for the urban area at 5 m altitude (AQI is 30), and the lowest NO2 ppb value is defined for the metropolitan area with an AQI of 10.

Despite good AQI results, some people groups might still be at risk of potential health issues.

Table 5 summarizes the average NO

2 and SO

2 concentrations obtained at various monitoring spots, along with the corresponding Air Quality Index (AQI) evaluation. Indoor measurements indicate that the bedroom shows low NO

2 levels (0.01196 ppb, AQI = 11) and moderate SO

2 levels (24.862 ppb, AQI = 35), indicating good air quality for the general population. However, sensitive groups such as people with asthma or other respiratory diseases, the elderly, and children are more at risk. In the kitchen, higher NO

2 concentrations (5.5684 ppb) were recorded, reflecting indoor cooking emissions. Urban outdoor measurements indicate low NO

2 at ground level (0.0106 ppb, AQI = 10), while SO

2 reached 33.2801 ppb (AQI = 46), demonstrating moderate air quality with potential risk for vulnerable groups. Measurements taken at 5 m altitude show slightly elevated NO

2 (0.03218 ppb, AQI = 30) but very low SO

2 (3.1375 ppb, AQI = 4), confirming that air pollutant concentrations decrease with altitude. These results highlight the importance of monitoring both indoor and outdoor locations, as well as vertical profiling, to capture spatial variability in air quality.

Based on the CO

2 gas readings, the following has been obtained (detailed data given in

Table 6) [

89]:

Based on the testing results for the hardware and software units, several problems have been identified. To minimize the appearance of these concerns and extend the prototype’s operational conditions (including the implementation of future considerations), specific improvements can be made.

Table 6 presents the average CO

2 concentrations recorded in indoor and outdoor locations. The highest indoor CO

2 concentration was observed in the kitchen (8693.206 ppm), reflecting cooking-related emissions and limited ventilation. In contrast, the bedroom showed 2461.475 ppm, indicating relatively better air circulation. Outdoor measurements indicate that the urban area at ground level reached 21,075.4 ppm, exceeding the standard limit of 5000 ppm and likely due to traffic, high population density, and other anthropogenic sources. Measurements at 5 m altitude decreased sharply to 464.491 ppm, demonstrating the vertical dilution of pollutants. These findings indicate that both the location and height of UAV-based measurements critically affect air quality assessments and underscore the need for adaptive monitoring strategies.

5.4. Example Table of Weighted Firing Strengths

The hybrid fuzzy inference system (FIS) used for UAV-based air quality monitoring integrates symmetric and asymmetric rules. Symmetric rules capture baseline environmental conditions, whereas asymmetric rules account for localized anomalies such as turbulence, irregular pollutant distribution, and sensor noise. Each fuzzy set is parameterized by triangular or trapezoidal membership functions (see

Table 7).

The firing strength αi of each rule is weighted by the symmetry index S, which quantifies deviation from baseline conditions. Weighted firing strengths ensure that asymmetric rules exert greater influence when environmental disturbances are detected. The crisp output Y∗ is calculated using centroid defuzzification, which determines UAV control actions (e.g., speed, altitude, or filtering mode) and reconstructs pollutant concentration.

A comparison with baseline fuzzy systems and standard machine learning models (SVM and Random Forest) was performed to validate improvements in reconstruction accuracy, demonstrating that the hybrid system reduces RMSE by 30–40% compared to conventional approaches.

5.5. Clarification of the Hybrid FIS Structure and Experimental Validation

To validate the hybrid fuzzy inference system (FIS), field experiments were performed across indoor, urban, and desert environments, complemented by a sensor calibration test at 4–5 m altitude. Each UAV flight collected continuous measurements of CO2, NO2, and SO2 along with environmental parameters such as wind speed (1–12 m/s) and temperature (15–38 °C). Sensor calibration data were used to verify linearity and stability of the analog-to-ppm conversion before field deployment, ensuring reliable pollutant reconstruction accuracy.

The hybrid FIS integrates symmetric and asymmetric fuzzy rules to adaptively model both baseline environmental states and local anomalies (e.g., turbulence, uneven pollutant distribution, sensor noise). Symmetric rules describe stable conditions, whereas asymmetric rules adjust UAV behavior and data weighting under disturbed conditions. The weighted firing strength of each rule (αᵢ · S) increases the influence of asymmetric rules when environmental variability is detected, improving reconstruction precision.

To further validate the hybrid FIS, benchmarking was conducted against standard machine learning models. Specifically, SVM and Random Forest were applied to reconstruct CO

2, NO

2, and SO

2 concentrations from UAV-collected sensor data. The RMSE values in

Table 8 show that the hybrid FIS reduces reconstruction error by 28–37% compared to conventional methods, demonstrating its enhanced ability to model asymmetric disturbances and improve air quality monitoring accuracy.

The RMSE for each pollutant was calculated as:

where

is the proper concentration,

is the predicted value, and

n is the number of measurements. The improved performance is attributed to the integration of symmetric and asymmetric fuzzy rules, which allow the system to adapt dynamically to localized anomalies in environmental conditions.

These results confirm that the hybrid FIS provides both practical and theoretical advantages over baseline fuzzy or machine learning models, supporting its use for robust UAV-based air quality monitoring.

5.6. Field Measurement Validation and Quantitative Benchmarking

The benchmarking results in

Table 8 confirm that the hybrid fuzzy inference system (FIS) significantly improves reconstruction accuracy compared to standard data-driven models such as SVM and Random Forest. The 30–40% reduction in RMSE across all pollutants indicates that the hybrid structure effectively adapts to asymmetric environmental conditions, such as turbulence and uneven pollutant dispersion.

To further validate these findings under real-world conditions, a series of UAV field experiments was conducted. Continuous CO

2, NO

2, and SO

2 measurements were recorded in indoor, urban, and desert environments, including calibration tests performed at 4–5 m altitude to verify sensor stability and linearity. The obtained results are summarized in

Table 9, which provides detailed pollutant concentrations, environmental conditions, and Air Quality Index (AQI) feedback for each UAV flight scenario.

Field experiments were conducted with N = 10 UAV flights. Continuous measurements of CO

2, NO

2, and SO

2 were collected while environmental parameters, including wind speed (1–12 m/s) and temperature (15–38 °C), were recorded.

Table 9 shows the average, maximum, and minimum readings, along with AQI feedback for each monitoring location.

Indoor environments, such as kitchens, showed elevated CO2 levels from cooking, while urban ground-level sites exhibited higher NO2 and SO2 concentrations from traffic and population density. Desert sites had low pollutant levels but high wind variability, demonstrating the UAV system’s robustness under varying conditions. The calibration test (Flight 6) at 4–5 m was used to verify sensor linearity and ppm-to-analog response stability before flight deployment.

The field data obtained were used to evaluate the reconstruction accuracy of the proposed hybrid FIS.

Table 5 and

Table 6 summarize the UAV-measured pollutant concentrations and AQI evaluations, while

Table 7 shows the membership functions and rule base.

To quantify the performance, the hybrid FIS results were benchmarked against baseline fuzzy systems and standard machine learning models (SVM and Random Forest).

Table 10 presents the RMSE comparison for CO

2, NO

2, and SO

2 reconstruction based on field data. The hybrid FIS consistently reduced RMSE by approximately 30–40% compared to baseline approaches, demonstrating enhanced capability to model asymmetric disturbances and providing practical improvements in air quality monitoring.

To validate the UAV-based measurements, recorded pollutant concentrations were compared with ground-truth sensor stations and standard reconstruction models, including regression, SVM, and Random Forest. Statistical metrics, including RMSE and Pearson correlation coefficients, were calculated for CO

2, NO

2, and SO

2. The results confirm that the UAV system reliably captures spatial variability: RMSE values for the hybrid FIS are 30–40% lower than baseline methods (see

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10). These findings demonstrate that the UAV system accurately reproduces both the magnitude and trends of pollutant concentrations across different environments. The validation confirms that the proposed monitoring approach is robust under varying conditions and capable of providing trustworthy measurements without requiring visual comparative plots.

To quantitatively validate the proposed hybrid FIS, its performance was benchmarked against baseline methods, including a classical fuzzy inference system (Baseline Fuzzy), regression models, SVM, and Random Forest. Validation metrics were obtained from ten field tests (N = 10) under indoor, urban, and desert conditions. RMSE and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed for each pollutant between UAV-based measurements and ground-truth data, and the results were averaged across environments.

The hybrid FIS achieves approximately 30–40% reductions in RMSE compared to baseline methods, demonstrating its practical advantage in real-world monitoring scenarios, particularly under asymmetric environmental disturbances. Moreover, Pearson correlation coefficients indicate strong agreement with reference measurements (r = 0.87–0.94), confirming that the hybrid system reliably captures trends in pollutant concentrations.

To ensure fair comparison and reproducibility, the SVM and Random Forest models were parameterized and optimized as follows:

SVM: The radial basis function (RBF) kernel was selected due to its robustness in handling nonlinear relationships. The penalty parameter was set to C = 10 and the kernel coefficient to γ = 0.1, determined via grid search to minimize the root mean square error (RMSE).

Random Forest: The model employed 100 decision trees with a maximum depth of 10, using the Gini impurity criterion for node splitting. Each tree was trained on a bootstrap sample (bagging), and the number of features considered at each split was equal to the square root of the total feature count.

Both models were trained using normalized sensor data (CO2, NO2, SO2 concentrations, temperature, and humidity) and validated using a 10-fold cross-validation scheme.

These parameter settings ensured balanced model complexity and generalization performance, allowing a fair comparison with the proposed hybrid fuzzy inference system.

These results confirm that the hybrid FIS provides a substantial improvement in reconstruction accuracy and strong correlation with ground-truth data, supporting its use for UAV-based air quality monitoring.

5.7. Potential Design Improvements and Considerations

The experience gained from implementing the proposed system has revealed areas for potential enhancements. The main emphasis has been on improving the housing unit and electrical circuits. During hardware testing, the drone’s housing unit has been identified as the weakest link. Its design and the materials used could be optimized. For example, adopting a spheroidal shape may be more effective, as it would decrease the overall surface area exposed to wind.

Regarding material selection, options include plastic, carbon fiber (which is more expensive), or silicone. Such improvements could lead to a significant reduction in weight, enabling a more adaptable component arrangement and a more compact structure. Another viable option would be to design a drone tailored to the specific user’s requirements. This approach would be advantageous for meeting technical specifications, as existing commercial drones often fall short of the particular features required. While this would significantly reduce anticipated maintenance expenses and improve flying conditions (through enhanced aerodynamic design), it would require a larger upfront investment. A bespoke drone combined with the proposed solution would represent the ideal technical choice; however, it would require a uniquely designed drone, which entails time-consuming and costly processes.

The configuration and arrangement of the drone’s side circuit could be improved. For example, having numerous power sources demands considerable space, which adds to the overall weight of the drone’s housing unit. An ideal solution would involve a single central power source that powers the entire system. Alternatively, a direct link to the drone’s supply could be considered, but this would likely result in a significant reduction in flight time. Ideally, the envisioned system should be capable of continuous charging with minimal or no battery replacements, possibly harnessing solar energy for recharging. Therefore, exploring a more dependable power supply could be beneficial. Nonetheless, research is ongoing to address the power-related challenges drones face, particularly in extending their flight duration.

Another enhancement could be selecting a more advanced microcontroller. Currently, they utilize a single-chip microcontroller, the ATmega328, integrated into the Arduino Uno, which meets the prototype’s needs. However, additional functions could be introduced to address certain limitations, such as insufficient on-board memory and the absence of multiple MOSI/MISO/SPI (data transfer) support. Opting for a more compact microcontroller (nanoscale) could also help reduce the total size and weight, though it may increase costs.

A more reliable transmission device could be considered for expanding the solution, given that a two-way communication system has been created. Streamlining was achieved using two ATmega microcontrollers. Although the modified NRF24L01 module has specific range and transmission limitations, its low cost was a crucial factor in its selection. As an alternative, the long-range LoRa SX1278 modem might be used, offering advanced communication capabilities and effective operation [

91].

The sensors selected for this prototype are a more economical choice. The currently used sensors measure CO

2, NO

2, and SO

2 concentrations, indicating significant fluctuations in the monitored areas; however, there is still room for improvement in accuracy. More sophisticated sensors could offer better precision and detection capabilities, resulting in more reliable readings, albeit at a higher cost. For example, the infrared gas module MH-Z16 operates on the non-dispersive infrared (NDIR) principle for CO

2 detection [

92]. Alternatively, an advanced sensor could be used to detect substances such as benzene (C

6H

6), ethanol (C

2H

5OH), or ammonia (NH

3), as needed.

Furthermore, a few optional enhancements could be highlighted, including a more user-friendly setup (in terms of hardware design) and expanded opportunities for data manipulation and analysis (in terms of software design), customized to meet user requirements.

Despite the previously mentioned potential enhancements, the system in question offers one of the most cost-effective designs and straightforward implementations for non-experts. The testing outcomes are satisfactory, which has been the main emphasis of this solution.

Although some limitations were noted during testing, the prototype effectively demonstrated its capability to detect notable shifts in air quality. However, to advance beyond basic threshold monitoring, upcoming versions should integrate adaptive fuzzy controllers that can interpret sensor inputs that are unclear, noisy, or unevenly distributed. Such systems will enable more adaptable, human-like reasoning when confronted with environmental uncertainties, variable sampling conditions, or imperfect sensor performance.

5.8. Simulation Study: Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Fuzzy Inference in Backward Problem

To illustrate the significance of symmetry and asymmetry in addressing the backward problem related to air quality estimation, a basic simulation experiment is conducted.

In the simulation setup, a pollutant concentration field

c(x) is assumed to be distributed along a one-dimensional axis (e.g., a UAV flight path). The actual concentration is defined as a Gaussian profile with a localized emission source. The UAV sensors provide noisy measurements affecting the pollutant concentration field as follows:

This corresponds to the forward problem (absolute concentrations—noisy sensor readings), while the backward problem is to reconstruct an AQI from sensor data {yi}.

Two fuzzy inference systems were tested: symmetric and asymmetric FISs. For symmetric FIS, the membership functions are triangular and evenly distributed across the universe of discourse. For example: IF pollutant is “medium” THEN AQI is “moderate”. For asymmetric FIS, the membership functions are skewed to capture stronger responses to local peaks. For example: IF pollutant is “medium-high” AND turbulence is “present” THEN AQI is “unhealthy”.

The following results were obtained: symmetric FIS provided stable AQI estimation under low-noise conditions, but underestimated risk when sharp asymmetric peaks occurred. While asymmetric FIS correctly shifted decision boundaries, it detected localized anomalies and produced more conservative AQI estimates in the presence of strong perturbations. A comparative Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) analysis indicated that the asymmetric rule base (RMSEasym equals 0.12) provided more accurate reconstruction under noisy and asymmetric conditions than the symmetrical one (RMSEsym value is 0.18).

Figure 14 illustrates the proposed UAV-assisted air quality monitoring framework. The drone is equipped with low-cost sensors to collect real-time data on CO

2, NO

2, and SO

2. The measurements are processed through a fuzzy inference engine that combines symmetric rules (representing equilibrium and baseline conditions) and asymmetric rules (capturing turbulence, local emission peaks, and noise). The hybrid fuzzy system reconstructs the AQI as a solution to a backward problem, thereby providing robust, adaptive air quality assessment under uncertain, heterogeneous environmental conditions.

This simulation confirms the mathematical interpretation as follows:

Symmetric rules correspond to equilibrium-like conditions and serve as a baseline approximation for understanding the system.

Asymmetric rules act as a regularization mechanism, improving the stability of the inverse solution in the presence of noise and local perturbations.

Therefore, the hybrid fuzzy approach demonstrates its value as a real-time, robust method for solving backward problems in environmental monitoring.

5.9. Cost-Performance Trade-Offs

A cost-performance analysis guided the selection of sensors and UAV construction materials. NDIR CO

2 sensors provide high measurement accuracy at moderate cost, while electrochemical NO

2 and SO

2 sensors balance sensitivity with affordability. Lightweight materials, such as carbon fiber and high-grade plastics, reduce UAV weight and energy consumption, enabling longer flight durations without compromising measurement quality.

Table 11 summarizes the trade-offs, demonstrating how the hardware design achieves an optimal balance between monitoring accuracy, UAV efficiency, and project cost.”

For example, the CO2 sensor provides ±50 ppm accuracy at moderate cost, NO2 and SO2 sensors detect down to 0.01 ppb while remaining affordable, and carbon-fiber components reduce UAV weight by approximately 20%, improving flight endurance. These considerations ensure an optimal balance between monitoring accuracy, UAV efficiency, and project cost.

6. Discussion

The presented prototype system demonstrated its capacity to detect variations in CO2, NO2, and SO2 concentrations under both stationary and drone-mounted conditions. The hybrid fuzzy model improved reconstruction accuracy for CO2, NO2, and SO2 concentrations compared with purely symmetric models. Asymmetric rules successfully captured localized anomalies and environmental disturbances. Data visualization demonstrated the practical significance of symmetry and asymmetry in environmental monitoring.

Despite its low-cost design and successful field testing in asymmetric environments, several limitations were identified throughout hardware and software evaluations. These limitations, while expected for a prototype, suggest clear directions for further research and development.

The use of symmetric and asymmetric fuzzy rules can be interpreted as an approach to uncertainty modeling. Symmetric rules ensure stability under predictable conditions, whereas asymmetric rules act as entropy-weighted adjustments to accommodate environmental irregularities and sensor noise, effectively regularizing the backward estimation problem.

The results confirm that air quality data exhibit symmetry breaking in real environments. Ideally, pollutant concentrations follow symmetric distributions, but disturbances such as wind, turbulence, and localized emissions disrupt this balance. The proposed hybrid fuzzy model restores stability by combining symmetric and asymmetric rules:

Symmetric rules capture normal environmental conditions, ensuring computational stability.

Asymmetric rules compensate for broken symmetry, allowing for adaptation to irregular patterns.

This approach can be interpreted as a resilience mechanism in which fuzzy logic serves as a mediator between theoretical symmetry and real-world asymmetry.

6.1. Hardware Unit Improvements

The UAV platform used in this study is a quadcopter with a flight range of 500 m and a maximum payload of 1200 g. Sensors included an MG-811 NDIR CO2 sensor, an MQ-136 SO2 electrochemical sensor, and an MQ-135 NO2 electrochemical sensor. These sensors were selected for their lightweight design, high sensitivity to the target pollutants, and compatibility with onboard data acquisition systems. The UAV can maintain stable flight at altitudes between 1 and 50 m, enabling both indoor and outdoor air quality monitoring. Flight duration with the full payload is approximately 25–30 min, depending on environmental conditions.

One of the most critical challenges encountered during testing was drone flight stability in high-speed winds, particularly in desert conditions. This instability was attributed to the suboptimal shape and weight distribution of the housing unit. In future designs, an aerodynamically optimized housing—potentially spheroid in shape and built from lightweight materials such as carbon fiber or high-grade plastic—will be implemented. A custom-designed drone tailored to the system’s specifications may further enhance performance and reduce power consumption.

Another area requiring improvement is the power supply configuration. Replacing multiple small batteries with a centralized or rechargeable unit (e.g., a solar-powered unit) would extend operating time and reduce weight. This would also facilitate more extended data-collection periods, especially during drone-based monitoring.

Sensor performance revealed nonlinearity, limited sensitivity at low concentrations, and discrepancies in the conversion between parts per million (ppm) and parts per billion (ppb). Future versions will integrate higher-grade sensors (e.g., NDIR for CO2, electrochemical for NO2 and SO2) to improve detection accuracy and enable reliable AQI assessments even at lower pollutant levels. Integrating multiple sensor types (e.g., temperature, humidity, and wind speed) would allow more comprehensive environmental assessments and enhance the relevance of monitoring results and their interpretation for both public and scientific use. Although this prototype focused on three gases, the system design is modular and can be extended to support additional air pollutants such as O3, PM2.5, CH4, or VOCs.

The following highlights the hardware unit improvements that were identified:

Expand sensor set (O3, CO, PM2.5/PM10) to detect additional asymmetric patterns.

Use more sensitive and reliable sensors (e.g., NDIR, electrochemical) to improve accuracy at low concentrations.

Improve UAV stability with lightweight, aerodynamically optimized housing.

Introduce a centralized or renewable power supply (e.g., solar) to extend the monitoring time.

6.2. Software Unit Improvements

To handle inconsistent sensor responses and environmental variability, future implementations will integrate fuzzy logic for data analysis. This would replace threshold-based interpretation with graded, human-like reasoning, enabling the system to better accommodate noisy, uncertain, and asymmetrically distributed sensor inputs. Machine learning techniques (e.g., clustering, anomaly detection) may also be explored for data interpretation and analysis.

The following software unit improvements were identified:

Expand the fuzzy rule base to formalize more cases of symmetry breaking.

Integrate machine learning to detect hidden asymmetries in sensor data.

Apply predictive analytics to anticipate disruptions in symmetry (e.g., traffic peaks).

A fuzzy-based fault-detection module was integrated to mitigate sensor drift and signal noise. The module monitors deviations from expected sensor patterns and flags measurements that exceed predefined fuzzy thresholds. This approach ensures robust data acquisition by compensating for transient errors or calibration drift, thereby maintaining reliable air quality reconstruction over time.

6.3. Networking Enhancements and User Applications

Wireless data transmission using the NRF24L01 module showed acceptable performance at short range but suffered from delays and instability over longer distances or in obstructed environments. Replacing it with a long-range communication module, such as LoRa SX1278, would substantially increase the transmission distance and improve signal robustness.

An improved user interface (e.g., graphical displays, smartphone connectivity) could support more straightforward data interpretation for non-expert users, increasing the system’s applicability in community-driven environmental monitoring efforts.

The following enhancements were identified:

Enable cloud integration for large-scale symmetry/asymmetry mapping.

Develop user applications to visualize real-time AQI dynamics.

Support participatory monitoring to capture both global symmetries and local asymmetries.

Beyond atmospheric air quality monitoring, the proposed hybrid FIS framework can be applied to other spatially distributed environmental variables. Potential applications include monitoring water quality parameters in rivers and lakes, mapping industrial emissions, and assessing the distribution of soil pollutants. The flexibility of the fuzzy rule base allows adaptation to diverse measurement scenarios, ensuring the method’s generalizability across environmental and engineering contexts.

6.4. Application Scenarios

In the existing prototype, conventional threshold-based techniques are employed to identify the presence of pollutants. Nonetheless, air pollutants often exhibit variable values due to factors such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and gas interactions. Basic binary thresholds are insufficient to effectively manage this uncertainty, leading to false alarms or missed detections.

Fuzzy logic provides a framework for modeling such situations by working with graded concepts—e.g., “low,” “medium,” and “high”—rather than binary yes/no classifications. This method offers the following:

More flexible and realistic representation of complex environmental conditions.

Increased robustness against sensor noise and signal instability.