Abstract

In modern elite football, accurate ball localization is increasingly vital for smooth match flow and reliable officiating. Yet mainstream detectors still struggle with small objects like footballs in cluttered scenes due to limited receptive fields, weak feature representations, and non-trivial computational cost. To address these issues and introduce structural symmetry, we propose a lightweight framework that balances model complexity and representational completeness. Concretely, we design a Dynamic clustering C3k2 module (DcC3k2) to enlarge the effective receptive field and preserve local–global symmetry and a SegNeXt-based noise-attentive C3k2 module (SNAC3k2) to perform multi-scale suppression of background interference. For efficient feature extraction, we adopt GhostNetV2—a lightweight convolutional backbone—thereby maintaining computational symmetry and speed. Experiments on a Football dataset show that our approach improves mAP by 3.4% over strong baselines while reducing computation by 2.2%. These results validate symmetry-aware lightweight design as a promising direction for high-precision small-object detection in football analytics.

1. Introduction

Accurate football target detection is of vital importance for the early identification of key match events [,], prevention of referee misjudgments, enhancement of tactical analysis precision, and reduction in performance and commercial losses caused by missed detections. In recent years, the increasing pace of gameplay, tactical diversity, and rising demand for high-quality broadcasting have contributed to the growing complexity and dynamics of football matches, posing significant challenges to manual detection and real-time analysis. In scenarios such as congested penalty areas [,,,], nighttime matches, or suboptimal lighting conditions, traditional monitoring approaches often fail to achieve stable and efficient detection, leading to increased risks of false positives and missed detections.

Although manual video [] review offers interpretability in analyzing match events, it is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and incapable of delivering real-time feedback. Sensor-based tracking systems provide a degree of automation but suffer from high deployment and maintenance costs, along with limitations in adaptability under occlusion, calibration drift, and varying environmental conditions. Similarly, technologies such as infrared or radar, while effective for measuring ball velocity or player positioning, are susceptible to interference from lighting variations, crowd occlusion, and complex field textures, making it difficult to accurately distinguish football objects from background noise. To overcome these limitations, computer vision-based object detection [,,,,] methods using broadcast imagery or match video have rapidly evolved in recent years. Leveraging deep learning and real-time inference capabilities, these methods not only enhance detection accuracy but also demonstrate strong robustness and real-time performance in complex visual environments.

In the early stages of football target detection, traditional machine learning approaches relied heavily on hand-crafted features extracted from images, followed by classification using models such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), decision trees, or clustering algorithms. For instance, Wang et al. proposed a color–shape hybrid feature strategy based on HSV color space and edge descriptors for football recognition. While effective under static conditions, the method’s accuracy declined significantly in crowded or dynamic scenarios. Zhao et al. combined Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) with SVMs to build a player and ball recognition system with improved robustness []. Li et al. integrated decision trees and clustering to estimate ball position based on player pose and spatial context []. In another study, Vidal-Codina et al. employed tracking data and rule-based logic to automatically identify ball possession and key events, achieving over 90% accuracy in selected contexts []. To improve detection precision and stability, Mavrogiannis and Maglogiannis proposed a post-processing approach that combined YOLOv5 detection results with color clustering and velocity estimation, enabling high-precision tracking of both players and the ball in match videos [].

While traditional methods have demonstrated promising results in constrained environments [], they depend heavily on expert-designed features and lack the adaptability required to generalize across diverse and dynamic match conditions.

With the advancement of deep learning [,,], convolutional neural network (CNN)-based object detection models have been widely adopted in football image and video analytics. Existing deep learning approaches can generally be categorized into two types: two-stage and one-stage detectors. Two-stage detectors, such as Faster R-CNN, were initially popular in ball detection tasks []. Zhang et al. proposed the FRCNN-Football model, which integrates multi-scale feature fusion modules to improve the detection of small targets like footballs, achieving a 4.2% improvement in accuracy over the baseline on the ISSIA-CNR Soccer dataset []. Li et al. further embedded attention mechanisms into the two-stage pipeline to enhance focus on dynamic player regions while maintaining high accuracy. However, the relatively slow inference speed and computational overhead of two-stage detectors hinder their application in real-time scenarios.

To address the demand for real-time performance, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series of one-stage detectors has emerged as the mainstream approach. Komorowski et al. introduced the DeepBall model, a fully convolutional network that generates ball confidence heatmaps with minimal parameters, suitable for embedded systems []. Their subsequent work, FootAndBall [], further optimized the architecture for long-distance match footage, improving detection speed and deployability. To further enhance robustness under complex backgrounds, researchers have incorporated attention mechanisms and Transformer-based architectures into YOLO frameworks [,]. Xue et al. proposed a dual-branch Transformer combined with a Swin module to extend receptive fields and suppress background noise, achieving a 5.6% accuracy gain in low-light and nighttime scenarios [].

In parallel, lightweight YOLO architectures have become a research focus to facilitate deployment on edge or mobile devices. Chen et al. integrated modules such as GhostConv and ShuffleNetV2 into YOLOv7 and introduced CARAFE upsampling along with the SIoU loss function []. This configuration maintained an mAP above 86% while reducing model parameters by over 60%. Narayanan et al. developed a pipeline combining YOLOv8 and ByteTrack for comprehensive ball possession and pass timing analysis [].

Despite these advancements, most existing football detection methods fall short in achieving both low parameter counts and low FLOPs, which are crucial for real-time applications. Furthermore, due to the small size of football targets, models must possess large effective receptive fields to ensure precise localization.

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- Symmetry-perception detection framework: We propose Football-YOLO, a lightweight symmetry-perception object detector specifically tailored for football match scenarios. The framework is designed to treat local and global information, as well as shallow and deep features, in a symmetry-aware manner to better capture the regular patterns of footballs and players.

- Symmetry-aware backbone and neck modules: We introduce two novel modules, DcC3k2 and SNAC3k2. DcC3k2 performs dynamic clustering and symmetric convolutional aggregation in the backbone, while SNAC3k2 employs symmetry-aware attention and encoder–decoder feature fusion in the neck. Together, they enhance small-object detection and robustness in cluttered backgrounds with only a modest increase in parameters.

- Superior performance on the Football dataset: Extensive experiments on the Football dataset demonstrate that Football-YOLO achieves higher Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5 than several mainstream one-stage and two-stage detectors, while maintaining a compact model size and real-time inference speed. Ablation studies further verify the effectiveness of the proposed symmetry-aware components.

2. Method

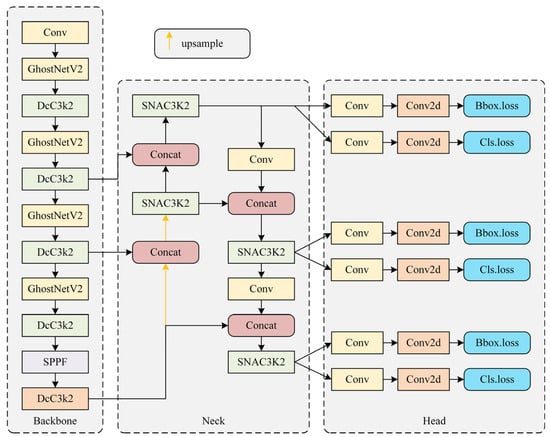

We present Football-YOLO, a novel and efficient object detection framework tailored for football match scenarios. As shown in Figure 1, the model is built upon a GhostNetV2-enhanced backbone and incorporates two key novel modules, DcC3k2 and SNAC3k2, to achieve a superior balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed Football-YOLO framework.

2.1. Yolov11

2.1.1. Backbone Layer

The backbone layer of YOLOv11 employs an optimized convolutional structure composed primarily of Conv-BN-SiLU modules and C3k2 modules []. The Conv-BN-SiLU module leverages the SiLU nonlinear activation function, enhancing the nonlinear representation capability of feature extraction. Meanwhile, the C3k2 module builds upon the traditional Cross Stage Partial (CSP) structure by integrating 2 × 2 convolutional kernels, significantly reducing parameter and computational complexity while improving the efficiency of feature fusion. Furthermore, the YOLOv11 backbone extracts features in stages, progressively representing features from shallow-level textures and edges to deep-level abstract semantic information, thereby providing rich, high-quality feature representations for subsequent multi-scale feature fusion.

2.1.2. Neck Layer

The neck layer plays a crucial role in feature fusion within the YOLOv11 architecture. Distinct from conventional PANet structures, the YOLOv11 neck incorporates an advanced spatial attention mechanism, known as the Convolutional Block with Parallel Spatial Attention (C2PSA), effectively emphasizing salient object regions while suppressing background interference. Additionally, through upsampling and cross-scale feature fusion, this layer fully utilizes the multi-scale feature maps provided by the backbone, significantly enhancing detection performance for small objects, dense scenarios, and partially occluded targets. The integration of C3k2 and C2PSA modules achieves high context-aware capability and computational efficiency, ensuring low latency.

2.1.3. Detection Head

The detection head of YOLOv11 continues the multi-scale prediction strategy, employing three distinct resolutions (P3, P4, and P5) from the neck layer outputs as inputs, facilitating precise detection from small-scale to large-scale objects. Internally, the detection head utilizes standardized Conv-BN-SiLU and C3k2 structures to further enhance the expressive capacity of the feature maps and improve detection accuracy. To address challenges such as scale variability and object overlap, YOLOv11 innovatively combines Complete Intersection-over-Union (CIoU) loss with Focal Loss during training, significantly improving localization accuracy and mitigating class imbalance and difficult sample detection issues. Additionally, its anchor-free detection head design reduces hyperparameter tuning complexity, thus enhancing the model’s generalization capability.

2.2. GhostNetV2

Object detection in soccer matches is crucial for real-time analysis of game scenarios, enhancing viewer experience, and assisting referee decision-making. Detection efficiency in real-time is a key evaluation metric. The backbone network of the YOLOv11 model widely employs convolution operations to increase the number of channels, thus expanding the receptive field. However, this approach increases the number of parameters and computational costs, adversely affecting real-time object detection tasks in soccer matches. The core idea behind lightweight network design is to enhance detection efficiency by improving convolution methods and employing more computationally efficient convolutional networks. Therefore, this study optimizes the backbone network of YOLOv11 by replacing the standard convolutions in the original network with GhostNetV2 modules to construct a lightweight feature extractor. While detection accuracy slightly decreases, the number of model parameters and computational costs are significantly reduced [].

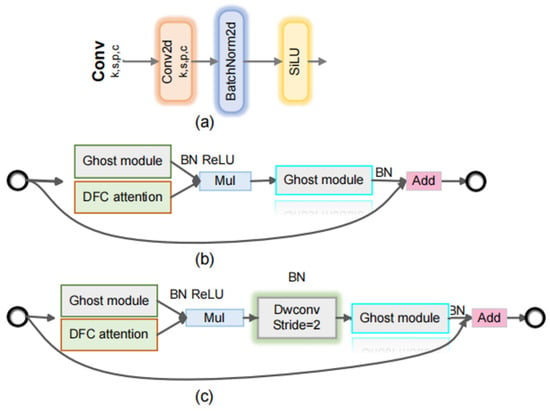

GhostNetV2 [] represents an advanced convolutional neural network architecture built upon the original GhostNet, aiming to further enhance computational efficiency and reduce redundancy in convolutional operations. The module is shown in Figure 2. Unlike traditional convolutional neural networks, GhostNetV2 introduces the Dynamic Ghost Module, which efficiently generates richer, less redundant feature maps via dynamic feature mapping, thus achieving a superior balance between accuracy and computational cost.

Figure 2.

GhostNetV2 Details. We integrate this architecture into the backbone of YOLOv11 to achieve lightweight design. (a) The structure of Conv; (b) The structure of GhostNetV2 when the stride is 1; (c) The structure of GhostNetV2 when the stride is 2.

Specifically, the Dynamic Ghost Module initially employs a small set of standard convolution operations to produce intrinsic features. Given an input feature map , intrinsic features are generated by a standard convolution operation , expressed as follows:

where X denotes the input tensor with Cin, channels and spatial resolution H × W; represents the standard convolution function that extracts intrinsic features, and corresponds to the intrinsic feature map with channels and spatial size .

Subsequently, the module uses inexpensive linear transformations (e.g., depthwise convolution or channel-wise operations) to dynamically expand the intrinsic features into additional “Ghost” features, which are redundant yet informative. This process can be mathematically formulated as:

where denotes a lightweight transformation function that efficiently generates additional ghost feature maps from the intrinsic features. Here, represents the newly synthesized ghost features, and , is the total number of output channels after combining both intrinsic and ghost components.

Moreover, GhostNetV2 integrates an adaptive gating mechanism, enabling dynamic selection and enhancement of these generated features. Assuming the gating function is denoted as , and applying the sigmoid activation function , the final output features can be defined as:

where G is the adaptive gating map controlling the importance of each ghost channel, indicates element-wise multiplication between the gating weights and the ghost features, and Concat [] denotes channel-wise concatenation. The resulting output therefore integrates intrinsic and selectively enhanced ghost features.

Here, represents the element-wise multiplication. Through this adaptive gating approach, GhostNetV2 dynamically determines whether Ghost features should be preserved or suppressed during inference, effectively reducing unnecessary computation while simultaneously strengthening feature representations.

2.3. DcC3k2

In football detection tasks, images typically contain numerous targets with substantial scale variations, particularly small-sized footballs. Such small-scale targets exhibit weak visual representations, occupy limited pixels within images, and are easily affected by background interference, posing greater challenges to feature extraction and localization capabilities of neural networks. Although parameter optimization has been performed on the backbone network in Section 2.2, the inherent constraints of lightweight network structures limit the effectiveness of traditional convolution operations, which are restricted to fixed local receptive fields. Consequently, networks struggle to model the long-range dependencies between football targets and background elements efficiently, impairing their ability to extract contextual information effectively and accurately localize football targets, thus severely limiting detection accuracy and generalization performance.

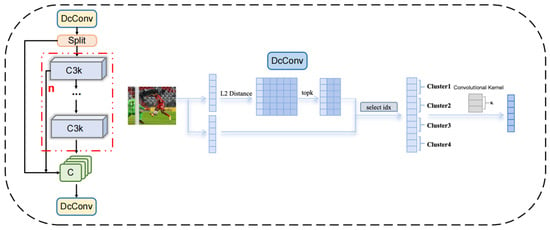

To address these challenges, this study introduces the concept of Dynamic Clustering Convolution (DCConv) and accordingly proposes an improved DCC3k2 module by modifying the C3K2f structure within YOLOv11. The module is shown in Figure 3. Unlike conventional local-window convolution, DCConv leverages an adaptive clustering mechanism to dynamically cluster spatial regions within images based on feature similarity at a global scale. Specifically, given the input feature maps, DCConv initially divides these maps into multiple spatial patches, considering each as a potential cluster center. Then, clusters are adaptively formed by calculating feature distances between image patches, with Euclidean distance employed as the measure between each patch and cluster center, :

Figure 3.

Structural details of the DcC3k2 module based on dynamic clustering convolution. This module expands the receptive field and strengthens small-object detection through adaptive feature aggregation.

Subsequently, the top-K nearest image patches to each cluster center, determined via a top-K selection strategy, constitute the clustering set. Convolution operations are then performed within each clustering set, aggregating information from these patches using shared convolution kernels, represented mathematically as follows:

Here, denotes the set of feature vectors within each clustering set, represents the weights of the dynamic convolution kernels, and denotes the bias term.

Furthermore, to alleviate the computational burden introduced by dynamic clustering at high-resolution image scales, this study adopts an efficient dynamic clustering strategy. Specifically, by employing interval sampling on feature vectors, the dimensionality involved in distance calculations is reduced, significantly decreasing the computational complexity inherent to dynamic clustering. Thus, the module achieves global semantic capture capability within an acceptable computational cost. Through the design outlined above, the proposed DCC3K2f module effectively expands the receptive field of the network, transitioning from a fixed local window to a globally adaptive semantic window, significantly enhancing the model’s capacity to capture long-range dependencies. This method effectively extracts semantic correlations between football targets and their contextual surroundings.

From the perspective of symmetry, the proposed DcC3k2 module enforces a balanced treatment of local and global information. Dynamic clustering is applied in a translation-invariant manner over all spatial positions, and each cluster is processed using the same shared convolutional kernel so that structurally similar neighborhoods are transformed in a symmetric way regardless of their absolute location in the image. Moreover, the dynamic receptive field is constructed by selecting the top-K nearest patches around each cluster center in feature space, producing a symmetric aggregation pattern where contexts from multiple directions are treated consistently. This design ensures that symmetric football patterns—such as circular ball appearances and regularly arranged players—are captured by the same set of kernels, improving both robustness and generalization in complex match scenes.

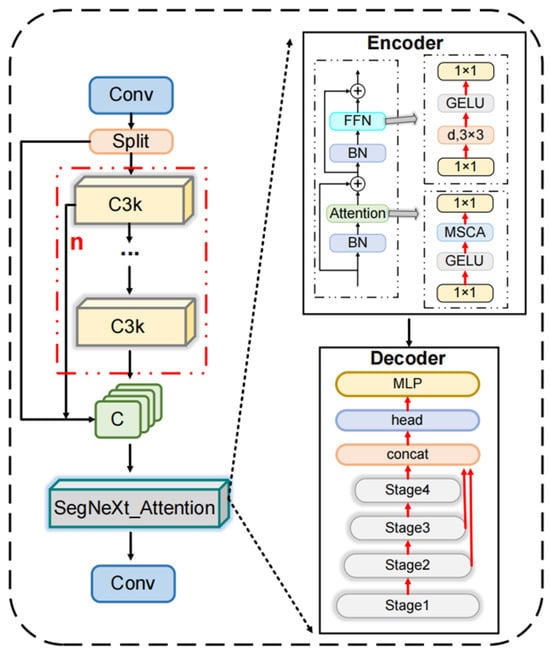

2.4. SNAC3k2 Neck Module

To further enhance global context modeling and reduce background interference, we design the SNAC3k2 module as the neck of Football-YOLO. SNAC3k2 is built on the SegNeXt attention mechanism and integrates a lightweight “hamburger” structure to capture both local and global information with low computational cost []. Specifically, SNAC3k2 receives multi-scale feature maps from the backbone, refines them with multi-branch depthwise convolutions and attention, and then fuses them in a symmetric encoder–decoder fashion. In this way, the neck can simultaneously emphasize discriminative football regions and suppress complex background clutter while keeping the model suitable for real-time deployment. The module is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the SNAC3k2 attention module, demonstrating multi-scale contextual attention and SegNeXt-based spatial feature enhancement for complex football scenes.

During the encoding stage, the input football image undergoes a sequence of convolutional and pooling operations, progressively reducing its spatial dimensions. At the same time, the feature representations are abstracted and enriched, enabling the extraction of high-level semantic information relevant to the task.

To further improve the model’s sensitivity to key regions such as players in motion, ball positions, or field markings, a Multi-Scale Contextual Attention (MSCA) module is introduced. This module adaptively emphasizes informative regions while suppressing background distractions by reweighting feature maps. It combines depthwise convolution for local feature extraction, multi-branch depthwise dilated convolution to capture multi-scale context, and convolution to model inter-channel dependencies.

The corresponding mathematical formulation is as follows:

where is the input feature map, Att denotes the attention map, and Out represents the refined output. The operator refers to element-wise multiplication, while denotes the scaling function applied to the -th branch.

In the decoding phase, the model progressively restores the spatial resolution of the image using upsampling and convolutional layers. This process integrates the high-level semantic features from the encoding path with high-resolution features generated in the decoding path, enhancing the fidelity of reconstructed target structures such as player outlines and ball trajectories.

In the decoding phase, the model progressively restores the spatial resolution of the feature maps using upsampling and convolutional layers. High-level semantic features from the encoding path are fused with high-resolution features in the decoding path through skip connections, which form a mirror-symmetric encoder–decoder topology. This symmetric cross-layer fusion allows shallow texture details and deep semantic cues to be aligned in a one-to-one manner across corresponding stages, leading to more precise reconstruction of key structures such as player contours, goalposts, and ball trajectories.

From a symmetry standpoint, SNAC3k2 is designed to maintain feature-level symmetry in three ways. First, the MSCA module employs multiple parallel depthwise dilated convolutions whose receptive fields are distributed in a balanced manner around each spatial location (e.g., in both horizontal and vertical directions and at multiple symmetric dilation radii). This configuration ensures that context from opposite directions is treated equitably when attending to a candidate football. Second, the same attention mechanism is applied in a symmetric fashion along the downsampling and upsampling paths so that information flowing from coarse to fine scales and from fine to coarse scales is processed by structurally identical blocks. Third, the integration of the lightweight “hamburger” module at the bottleneck introduces a symmetric global context interaction: local features refined by SegNeXt/MSCA are projected into a compact global representation and then redistributed back to all spatial positions, enforcing consistency between local evidence and global scene layout

To maintain a lightweight and computationally efficient decoder structure, the model selectively utilizes feature maps from only the last three stages (stage 2, stage 3, and stage 4). The symmetric reuse of SNAC3k2 across these stages, combined with the mirrored encoder–decoder connections, allows the module to preserve symmetry in both the network architecture and the feature transformations, thereby enhancing detection precision while keeping the overall model compact and suitable for real-time football video analysis.

2.5. Symmetry-Aware Design in Football-YOLO

The overall architecture of Football-YOLO is conceived under a symmetry-aware design paradigm, which seeks to maintain structural and functional balance across feature hierarchies.

At the architectural level, the modules DcC3k2 and SNAC3k2 constitute a pair of complementary, symmetrically placed components in the backbone and neck, respectively. DcC3k2 performs symmetric clustering and spatial aggregation through shared dynamic kernels, whereas SNAC3k2 realizes symmetric encoder–decoder attention and multi-scale contextual refinement. This dual arrangement enforces a consistent correspondence between local and global representations as well as between shallow and deep feature abstractions.

At the feature fusion level, the neck adopts a bidirectional fusion topology characterized by top-down and bottom-up information flows that are architecturally mirrored across the three detection scales. Each scale receives bidirectional guidance from finer and coarser resolutions via skip connections, while identical module families (C2PSA, DcC3k2, SNAC3k2) are recurrently employed across fusion paths. This mirror-symmetric propagation ensures balanced information exchange along multiple directions in the feature pyramid, a property particularly beneficial for detecting small, symmetric targets such as footballs.

At the optimization level, the detection heads operating at all scales share an identical prediction configuration and are trained under the same CIoU-based localization and classification objectives. Such uniform supervision introduces supervisory symmetry, compelling the backbone–neck pipeline to yield feature embeddings that are equally discriminative across spatial resolutions. The performance gains reported in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 empirically substantiate that this symmetry-aware formulation enhances both the robustness and the accuracy of Football-YOLO on the Football dataset.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison between Football-YOLO and YOLOv11n on the Football dataset, including Precision, Recall, mAP, and parameter count.

Table 2.

Ablation study results illustrating the individual and combined effects of GhostNetV2, DcC3k2, and SNAC3k2 modules on model performance and computational complexity. Note: ★ denotes that the respective module is included in the method configuration.

Table 3.

Performance comparison between Football-YOLO and several mainstream object detectors, including Faster R-CNN, SSD, YOLOv5s, YOLOv6-N, and YOLOv8s.

3. Experimental

3.1. Experimental Environment and Evaluation Metrics

Experimental Setup. All experiments were conducted on 64-bit Windows 10 using Python 3.10 and the PyTorch 2.1 deep learning framework for both training and evaluation. Hardware consisted of an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB of VRAM, providing ample computational capacity for efficient training and inference. To ensure consistency and reproducibility, this hardware–software configuration was held fixed across all experiments reported in this work.

We optimized with stochastic gradient descent (SGD) using a momentum of 0.9 and a weight decay of 5 × 10−4. The initial learning rate was 0.01 and followed a cosine-annealing schedule over the course of training. We employed standard data augmentations—random scaling, random cropping, and horizontal flipping—and adopted the same anchor configuration as the YOLOv11n baseline. Unless otherwise noted, these settings were kept identical across all compared models to ensure fair and reproducible comparisons.

To systematically and comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed football detection model, four widely recognized quantitative metrics were adopted: Recall, Precision, F1-score, and mean Average Precision (mAP). Specifically, Precision measures the proportion of actual positive samples among the predicted positive samples, while Recall indicates the model’s ability to detect all ground-truth targets. The F1-score, as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, provides a balanced evaluation of detection performance. The mAP metric, calculated as the mean of Average Precision (AP) across multiple classes, effectively reflects the overall detection performance of the model on the entire football dataset. The formulas for these metrics are defined as follows:

Here, (true positives) represents the number of targets correctly detected by the model, (false positives) denotes incorrectly identified non-targets, and (false negatives) indicates the number of missed targets. The term denotes the average precision for the -th class, and represents the total number of classes. In the context of football detection, where the number of target classes is limited and clearly defined, the mAP metric effectively reflects the model’s comprehensive detection performance across the entire dataset.

Furthermore, to assess the complexity and resource consumption of the model comprehensively, the total number of parameters and floating-point operations (FLOPs) were also analyzed. The number of parameters refers to the sum of all trainable weights and biases in the model, directly indicating the storage requirements and representational capacity. In contrast, FLOPs quantify the number of floating-point computations executed during a single forward inference pass, reflecting the computational resource requirements during practical deployment. These metrics are calculated as follows:

Here, and respectively denote the numbers of weights and biases in the -th layer, and is the total number of layers.

Here, represents the number of floating-point operations required in the -th layer, which depends on factors such as convolution kernel size, feature map dimensions, and network connectivity. Generally, higher FLOPs indicate a heavier computational burden, directly affecting the efficiency and suitability of the model for real-world deployment.

3.2. Datasets

The Football dataset utilized in this study is a purpose-built benchmark specifically designed for the task of football object detection. It comprises a total of 2724 manually annotated images, each containing bounding box annotations following a standardized format. The dataset is characterized as a single-class detection corpus, with all instances labeled under the category “football,” referring exclusively to the ball object. This framing defines the task as a single-class object detection problem.

To facilitate comprehensive model development and evaluation, the dataset is randomly partitioned into training, validation, and test subsets following an 8:1:1 ratio. The training set is employed for model optimization, the validation set is used for hyperparameter tuning and model selection, while the test set serves to objectively assess model generalization on previously unseen data.

Importantly, the dataset captures a wide spectrum of real-world football match scenarios, encompassing diverse backgrounds, camera viewpoints, lighting conditions, and object scales. This variability contributes to the robustness and adaptability of detection models trained on the dataset, enabling improved performance in complex and dynamic environments typical of live football matches.

3.3. Comparative Experimental Results

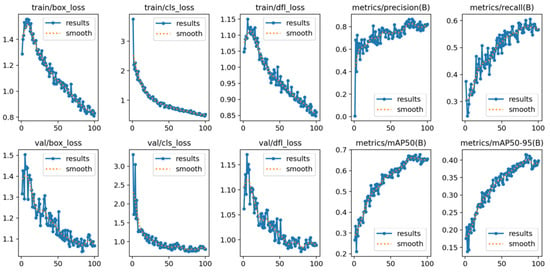

To validate the superior performance of the proposed Football-YOLO model over YOLOv11n in football match detection, we conducted comparative experiments on an identical test dataset. As illustrated in Figure 5, the proposed model demonstrates improved convergence of the loss function during training. Moreover, under various precision evaluation metrics, Football-YOLO consistently outperforms the baseline.

Figure 5.

Football training details demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method.

To further assess the applicability of Football-YOLO in football detection, we carried out a comparative analysis against the YOLOv11n model using a unified test dataset. As shown in Figure 4, Football-YOLO exhibits markedly better convergence behavior of the loss function during training and validation. In addition, across multiple accuracy evaluation metrics, the proposed model achieves significant improvements over the standard YOLOv11n model.

As illustrated in Table 1, the proposed Football-YOLO model achieves notable performance improvements over the baseline YOLOv11n across key evaluation metrics, with increases of 3.3% in Precision, 1.7% in Recall, and 3.4% in mAP. These enhancements are primarily attributed to the integration of the redesigned DcC3k2 module in the backbone, which significantly boosts the model’s ability to detect small and fast-moving targets, such as players and the football.

Furthermore, the incorporation of the novel SegNext_Attention mechanism enhances the model’s focus on task-relevant spatial features—particularly those associated with football positioning—under complex and dynamic match conditions. This mechanism also contributes to robustness by effectively suppressing background interference caused by varying lighting conditions and pitch textures.

In addition, the integration of SNAC3k2 and GhostNetV2 modules helps maintain high detection accuracy while reducing the overall parameter count by 0.2 million. This efficiency gain is largely credited to optimized convolutional operations and the lightweight “hamburger” architecture embedded within SNAC3k2, which facilitates effective global context modeling with minimal computational overhead.

Taken together, these architectural innovations enable Football-YOLO to deliver a favorable balance between model compactness and real-time, high-precision detection performance. Such capabilities make the model especially suitable for downstream applications, including tactical analysis, automated event recognition, and intelligent broadcasting in football scenarios.

3.4. Ablation Study Results

To further evaluate the detection performance of the proposed Football-YOLO algorithm, we conducted ablation studies to examine the impact of each individual improvement over the baseline. The performance metrics include Precision, Recall, F1 score, mAP, and FLOPs. The corresponding experimental results are presented in the accompanying figures and tables.

Table 2 reports the experimental results of the model on the Football dataset under various optimization strategies. As evidenced by the table, each newly integrated module contributes to incremental performance improvements. Specifically, “GN,” “DcC3k2,” and “SNAC3k2” refer to the incorporation of GhostNetV2 and two custom-designed architectural components, respectively.

Method (1) demonstrates that introducing GhostNetV2 into the backbone substantially reduces computational complexity, yielding a 2.3 G reduction in FLOPs. This efficiency is primarily attributed to GhostNetV2’s feature generation paradigm, which initially employs a limited number of standard convolutions to produce base features and subsequently enriches them through low-cost operations. This two-stage process significantly lowers computational demands. Moreover, the model benefits from enhanced feature reuse and fusion strategies, which further contribute to computational efficiency. However, this streamlined design results in a slight drop in detection performance.

To offset the accuracy degradation caused by the lightweight backbone, Method (2) introduces the DcC3k2 module into the network architecture. Compared to Method (1), this addition yields improvements of 2.5% in mAP, 2.4% in Precision, and 1.0% in Recall. These gains stem primarily from the clustering-based convolutional design of DcC3k2, which provides a larger receptive field and strengthens the model’s ability to capture global contextual information. This enables more precise localization of football targets—particularly small objects—while maintaining computational efficiency.

Building on this foundation, Method (3) incorporates the SNAC3k2 module into the Neck layer, resulting in further enhancements. Compared to prior methods and the YOLOv11n baseline, Method (3) achieves additional gains of 3.4% in mAP, 3.3% in Precision, and 1.7% in Recall. The SNAC3k2 module is designed to emphasize task-relevant features while effectively suppressing background noise in complex visual environments. Its ability to facilitate efficient multi-scale feature aggregation further elevates detection performance.

Ultimately, the final Football-YOLO architecture adopts the configuration used in Method (3), delivering the best trade-off between performance and efficiency. On the Football dataset, it achieves an mAP of 67.6% with a computational cost of 4.8 GFLOPs, outperforming the YOLOv11n baseline in both accuracy and model compactness.

3.5. Comparison with Mainstream Algorithms

We compared the proposed Football-YOLO model with several mainstream single-stage lightweight object detection models (YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5s, YOLOv6-N6, YOLOv6-N, YOLOv8s) as well as two-stage object detection models (Faster R-CNN R50-FPN and SSD) on the same football detection test dataset to further evaluate its overall performance.

The tables and figures present the experimental results of these methods on the M4SFWD football dataset. The results indicate that the proposed Football-YOLO model outperforms the current state-of-the-art single-stage object detection models, achieving a superior detection performance. Notably, it maintains a relatively small number of parameters while achieving an mAP of 90.1. These findings further validate the superiority and practical value of the proposed model in football detection tasks, particularly for multi-scale target detection in complex match scenarios.

As presented in Table 3, Faster R-CNN demonstrates limited effectiveness in football detection, primarily due to its reliance on single-scale feature maps for anchor generation, which restricts its ability to handle objects of varying sizes. Its complex two-stage architecture also results in substantial computational overhead, rendering it unsuitable for real-time match scenarios. SSD adopts multi-scale feature maps to enhance speed, yet its sensitivity to noise and the low resolution of deep-layer features diminish its detection accuracy, resulting in a lower mAP. YOLOv3-tiny improves inference speed by significantly reducing parameters (16.46 M), but this comes at the expense of accuracy, especially for small objects like footballs. YOLOv5s mitigates some of these limitations by incorporating an optimized loss function and data augmentation, achieving a more favorable balance between accuracy and model size (7.2 M). YOLOv6-N and YOLOv6-N6 further refine backbone efficiency and feature representation, yielding similar detection results despite minor differences in architectural complexity. YOLOv8s continues this progression with improved detection heads and spatial feature strategies, offering competitive performance with moderate model size (11.2 M), though still limited in complex background scenarios. In contrast, the proposed Football-YOLO model outperforms all counterparts by achieving the highest Precision (80.9%), Recall (58.1%), and mAP (67.6%) on the Football dataset while maintaining a compact size of only 4.8 M parameters. This superior performance stems from its integration of advanced modules such as DcC3k2, SNAC3k2, and GhostNetV2, which enhance feature extraction, multi-scale detection, and background suppression, making it particularly adept at identifying footballs and players in dynamic, real-world environments.

3.6. Time Complexity Analysis

To further evaluate the computational efficiency of the proposed architecture, we conducted a time complexity analysis of each key module in Football-YOLO. The total computational cost can be approximated as

where L denotes the total number of convolutional layers, Kl represents the kernel size of the I-th layer, and are the input and output channel numbers, and are the corresponding spatial dimensions. Compared with the standard convolutional baseline, the GhostNetV2 backbone substantially reduces the number of expensive convolutional operations by replacing part of the computation with lightweight linear transformations, resulting in an approximate complexity of

where s ∈ [2, 3] denotes the reduction factor determined by the ratio of intrinsic to ghost feature maps. Similarly, the DcC3k2 module achieves an adaptive receptive field expansion without quadratic growth in computation by performing clustering in a low-dimensional feature subspace, yielding a complexity of approximately

where N is the number of spatial locations, K is the number of selected nearest clusters, and d is the feature dimension. The SNAC3k2 neck module, composed primarily of depthwise convolutions and linear attention, maintains a near-linear complexity with respect to spatial resolution.

Empirically, Football-YOlO reduces the overall FLOPs from 6.6 G (YOLOv11n baseline) to 4.8 G, representing a ≈ 27% decrease in time complexity, while preserving real-time inference capability on an RTX 4090 (GPU ≈ 92 FPS). This analysis confirms that the proposed design achieves a favorable trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency, validating the practicality of Football-YOLO for real-time football analytics.

4. Conclusions

This study presents an effective and lightweight framework for small-object detection in complex football match scenarios. By integrating the DcC3k2 and SNAC3k2 modules, the model gains enhanced global context perception and fine-grained feature extraction capabilities. Coupled with the GhostNetV2 backbone, the proposed architecture achieves a favorable trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. Experimental results confirm that the method not only improves detection performance but also reduces computational burden, highlighting its potential for real-time football analysis applications and offering a viable solution for small-object detection tasks in challenging environments.

Author Contributions

J.Z. designed the research framework, conducted the experiments, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. H.L. assisted in dataset construction, literature review, and visualizations. Y.G. developed and optimized the model architecture, including algorithmic implementation and code validation, and contributed to result interpretation and manuscript revision. G.Z. supervised the overall project, provided theoretical guidance, and critically reviewed and refined the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Guangdong Higher Education Association “14th Five-Year Plan” 2025 Higher Education Research Project: Integrated Education–Technology–Talent Training Model for University Football Programs (Project No. 25GBY069).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available and can be accessed at the following link: https://blog.csdn.net/yolomaster/article/details/148128929 (accessed on 22 May 2025). Further information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, A.; Sun, Y.; Kortylewski, A.; Yuille, A.L. Robust object detection under occlusion with context-aware compositionalnets. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 12645–12654. [Google Scholar]

- Seweryn, K.; Chȩć, G.; Łukasik, S.; Wróblewska, A. Improving Object Detection Quality in Football Through Super-Resolution Techniques. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science, Singapore, 7–9 July 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzid, A.; Sierra-Sosa, D.; Elmaghraby, A. A Robust Pedestrian Re-Identification and Out-Of-Distribution Detection Framework. Drones 2023, 7, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvaras, L.; Petropoulos, G.P. A novel technique based on machine learning for detecting and segmenting trees in very high resolution digital images from unmanned aerial vehicles. Drones 2024, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Gwon, G.-H.; Kim, I.-H.; Jung, H.-J. A motion deblurring network for enhancing UAV image quality in bridge inspection. Drones 2023, 7, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, X.; Shen, S.; He, X.; Xia, X.; Li, N.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Ding, N. A Real-Time Strand Breakage Detection Method for Power Line Inspection with UAVs. Drones 2023, 7, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Qiu, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C. Defrcn: Decoupled faster r-cnn for few-shot object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 8681–8690. [Google Scholar]

- Goerlandt, F.; Montewka, J. Maritime transportation risk analysis: Review and analysis in light of some foundational issues. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2015, 138, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, X.; Gao, X.; Hong, W.; Fu, K.; Sun, X. A densely connected end-to-end neural network for multiscale and multiscene SAR ship detection. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 20881–20892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Ding, B. A new deep neural network based on SwinT-FRM-ShipNet for SAR ship detection in complex near-shore and offshore environments. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, S.; Xu, F.; Liu, J. LMSD-Net: A lightweight and high-performance ship detection network for optical remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-Q.; Zheng, P.; Xu, S.-T.; Wu, X. Object detection with deep learning: A review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 3212–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana Steffi, D.; Mehta, S.; Venkatesh, K.; Dasari, S.K. HOG-based object detection toward soccer playing robots. In Computer Vision and Robotics: Proceedings of CVR 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Euldji, R.; Boumahdi, M.; Bachene, M. Decision-making based on decision tree for ball bearing monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Workshop on Human-Centric Smart Environments for Health and Well-Being (IHSH), Boumerdes, Algeria, 9–10 February 2021; pp. 171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Codina, F.; Evans, N.; El Fakir, B.; Billingham, J. Automatic event detection in football using tracking data. Sports Eng. 2022, 25, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, C.; Wu, S.; Ren, Y. UAV-YOLOv5: A Swin-transformer-enabled small object detection model for long-range UAV images. Ann. Data Sci. 2024, 11, 1109–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha, F.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, A.; Das, S.; Karim, M.R.; Alam, M.M.; Sultana, T. From Classical Techniques to Convolution-Based Models: A Review of Object Detection Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 6th International Conference on Image Processing, Applications and Systems (IPAS), Lyon, France, 9–11 January 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Adarsh, P.; Rathi, P.; Kumar, M. YOLO v3-Tiny: Object Detection and Recognition using one stage improved model. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, 6–7 March 2020; pp. 687–694. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W.-Q. A lightweight faster R-CNN for ship detection in SAR images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, J.; Kurzejamski, G.; Sarwas, G. Deepball: Deep neural-network ball detector. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.07304. [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski, J.; Kurzejamski, G.; Sarwas, G. Footandball: Integrated player and ball detector. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.05445. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Pan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wei, H.; Liu, C. Sod-Yolo: Small-Object-Detection Algorithm Based on Improved Yolov8 for UAV Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Hashmi, K.A.; Liwicki, M.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Object Detection with Transformers: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, P.; Borch, N.; Fjeld, M. FootyVision: Multi-object tracking, localisation, and augmentation of players and ball in football video. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Multimedia and Image Processing, Osaka, Japan, 20–22 April 2024; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ouyang, H.; Chen, X. A multiscale lightweight and efficient model based on YOLOv7: Applied to citrus orchard. Plants 2022, 11, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Donthi, Y.; Kumar, R. YOLOv8: A Novel Vehicle Mirror Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Electronics and Renewable Systems (ICEARS), Tuticorin, India, 11–13 February 2025; pp. 1546–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, E.; Wei, D.; Li, F.; Lv, H.; Li, S. Object Detection Model of Vehicle–Road Cooperative Autonomous Driving Based on Improved YOLO11 Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Tian, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, M. Heterogeneous Secure Transmissions in IRS-Assisted NOMA Communications: CO-GNN Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 34113–34125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Han, K.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. GhostNetv2: Enhance cheap operation with long-range attention. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 9969–9982. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.-H.; Lu, C.-Z.; Hou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, M.-M.; Hu, S.-M. Segnext: Rethinking convolutional attention design for semantic segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).