Abstract

A new transformation of parameters for generic discrete-time dynamical systems with two independent parameters is defined, for when the degeneracy occurs. Here the classical transformation of parameters is not longer regular at ; therefore, implicit function theorem (IFT) cannot be applied around the origin, and a new transformation is necessary. The approach in this article to a case of Chenciner bifurcation is theoretical, but it can provide an answer for a number of applications of dynamical systems. We studied the bifurcation scenario and found out that, by this transformation, four different bifurcation diagrams are obtained, and the non-degenerate Chenciner bifurcation can be described by two bifurcation diagrams.

1. Introduction

Discrete dynamical systems arise in many applications [1] where observing a phenomenon [2] is not a continuous procedure [3] but a discrete one [4]. One of the elements of interest in dynamic systems [5] is the Chenciner bifurcation [6].

Symmetries in the local phase portrait for some polynomial dynamical systems were recently presented in [7]. In the last few decades, biology has been an important source of mathematical models, discrete and continuous [8,9,10], as has medicine [11]. E.g., a discrete-time epidemic model of heterogeneous networks was studied in [11]. That has a more complex equilibrium than the continuous cases modeled by differential equations.

The non-degenerate Chenciner bifurcation has been studied in many papers [5,12,13,14]. In the last few years, this kind of bifurcation has appeared in various research papers [15,16,17,18] in biology, physics, economy and informatics, and in multidisciplinary and applied sciences [19,20,21], due to the increasing importance of its applications [22,23] in the study of the processes and phenomena of the real world [24,25,26].

In economics, e.g., one of the simplest and most studied nonlinear models of business cycles is the one proposed by Kaldor. In [27], a version of the Kaldor business-cycle model, which is an example of discrete-time system, was studied in order to find a new model of dynamics applicable in mathematics and economics.

Since its configuration, the Kaldor model has known a number of approaches and even additions (such as the Kaldor–Kaleki variants). The idea behind the Kaldor model is that the system becomes unstable if the propensity to invest surpasses the one to save.

Additionally, in economics, one of the earliest discrete time models for the business cycle is Samuelson’s business cycle model given by [21]. Starting from this model, over the last few decades, there have been a lot of papers which generalized and studied it. For instance, Sedaghat [28] presented the sufficient conditions for the global attractivity of the fixed point and the conditions in which the solutions produce the persistent oscillations, and then showed that the solutions exhibit strange and complex behaviors. El-Morshedy [29] gave a new global attractivity criterion through a Lyapunov-like method. Sushko, Puu and Gardini [30] studied the Neimark–Sacker bifurcation when the function f from the improved model of Sedaghat [31] is a polynomial with degree 3. Li and Zhang [32] investigated the Neimark–Sacker bifurcation if the n-th Lyapunov coefficient is nonzero, and found the existence of j invariant circles for arbitrary . Zhong and Deng [16] found firstly that Equation from their paper undergoes a generalized flip bifurcation and secondly found the conditions for the Chenciner bifurcation. The Chenciner bifurcation has more complicated dynamical properties than the Bautin bifurcation of a vector field. Recent, in [3], the model of Samuelson multiplier accelerator for the echilibrium of national economy was studied. The Chenciner bifurcation has a parameter space of two dimensions. In papers such as [33,34,35] the financial market is considered as an evolutionary system of trading strategies in competition. Thus, it is possible to explain the volatility clustering for systems of multi-agent type. Nonlinear systems of economics usually present strange attractors. Evaluating them by a Lebesque measure results a strict positive value; see, for example, [36]. Other works present adaptive learning and the motivation of limited rationality [37].

The first economic application of the Chenciner bifurcation is given in [38] on a heterogeneous model having evolutionary learning. Financial markets could be considered as complex evolutionary systems, where, in principle, two categories of traders can be distinguished: “fundamentalist” and “technical analyst” (established as “trend followers” or “chartist”). "Fundamentalists" have so-called "rational expectations" based on future dividents, whereas those guided by market trends analyze past prices and extrapolate them. Over time, the weights of the categories of traders change depending on the utility obtained from the profits made, or the accuracy of the forecasts made in the past, respectively [39,40,41,42,43,44]. The conclusion reached after the analysis of this model is that the “coexistence of a stable steady state and a limit cycle arises due to a Chenciner bifurcation” [38]. Article [38] excludes the case of degeneration. Our article analyzes only a situation of degeneration. The economical example used there (see page 14) is based on a vector field of the following type written in polar coordinates:

where O means terms of higher order and the eigenvalue of the bifurcation is .

The Chenciner bifurcation is non-degenerated iff In our case the interesting condition is the complementary one , which renders the degenerated Chenciner bifurcation. The analysis of the non-degenerated discrete Chenciner bifurcation is more laborious then the regular one. There are several cases which must be separately analyzed. A first case was solved in [1], and another case in [45].

In the following is presented another possible degeneration of a discrete Chenciner bifurcation.

The mathematical part supposes a discrete dynamical system:

having , and , with Without indices the system (2) is written as

or [1]. Like in [6], Chapter 9.4, page 404 and [1], we study the dynamics system by using complex coordinates in (3)—that is,

and g being smooth functions of all arguments, where and [1]. Writing the function g in the form of Taylor series gives

In [1] where are smooth functions having complex values. Equation (4) can be thus written as

where We denote then by

A bifurcation in the system (7) for which , , but is called Chenciner bifurcation or sometimes, generalized Neimark–Sacker bifurcation. From it is obtained that

When the transformation of parameters

are regular at then the system (7) is simplified in a simpler form. This is called the non-degenerate Chenciner bifurcation, as was studied in [6]. However, the degenerate case when the change of parameters [6] is not regular at is not considered any further.

The idea is to change these coordinates and to work only using the initial parameters in the form (6).

In [1], the authors studied the Chenciner bifurcation: when it become degenerate regarding the parameter transformations (8). That is, the transformation (8) is not regular in This degeneracy does not allow us using as new parameters. The solution is to use the initial parameters in the form (7).

Recall out of [1] relation (13) page 4, that

for some and , and and so on [1].

The purpose of this article is to contribute to the enrichment of the literature with the study of Chenciner bifurcation in a case of advanced degeneration. The goal of this work was to continue the study realized in [1] for (see Theorem 2) considering a further degeneration given by the assumption that A different method than that used in [1] is needed, based on the sign of and when

This article is structured into four sections, Section 1 being the Introduction, where the non-degenerate Chenciner bifurcations (or generalized Neimark–Sacker bifurcation) are presented by using the truncated normal form of the system (5) and polar coordinates, and some of their applications in various domains are mentioned. The Section 2 describes the results obtained before in [1] concerning the existence of bifurcation curves and their dynamics in the parametric plane in the cases where and the linear parts of and nullify, respectively. The Section 3 is the most important part of this paper, in which we analyze the degenerate Chenciner bifurcation, the dynamics of the bifurcation curves in the parametric plane when and The bifurcation diagrams are also presented there. The Section 4 are presented in the fourth section of the paper.

2. Methods

It is known that the truncated form of the -map of (7) is

Then the -map of the system (7) describes a rotation by an angle depending on and It can be approximated by next equation.

It is assumed that [1]. The truncated normal form (5) is (9) and (10). In Equation (9) the -map and the -map are independent and they will be separately studied.

The one dimensional dynamic system for the -map (9) has a fixed point in origin for any value of . There is a correspondence between the fixed point of the -map strictly positive and a limit cycle in the system (9) and (10).

It can be seen that for is sufficiently small, because and By for we denote the set of series of real coefficients of the form:

It will be necessary in the next section to show the following results which have been established in [1].

Proposition 1.

The fixed point O is (linearly) stable if and unstable if for all values α with sufficiently small. On the bifurcation curve O is (nonlinearly) stable if and unstable if when is sufficiently small. At O is (nonlinearly) stable if and unstable if [1].

Periodic orbits in (9) and (10) are given “by the positive nonzero fixed points of the -map (9)” [45], which can be obtained by solving the next equation

where Denote “by respectively, and the roots of (11), if they are real numbers” [1].

Theorem 1.

“It is true that

- (1)

- (2)

- (a)

- one periodic unstable orbit if and

- (b)

- one periodic stable orbit if and

- (c)

- two periodic orbits, unstable and stable, if or in addition, if and if

- (d)

- no periodic orbits if or

- (3)

- (4)

The generic phase portraits corresponding to different regions of the bifurcation diagrams, for different regions are given in Figure 1 from [1]. That includes the phase portraits for the curves of bifurcation given by

The smooth functions can be written as and , and the transformation (8) is not regular at This means that the Chenciner bifurcation degenerates, if and only if

Remark 1.

In [1], the case when (12) is satisfied with non-zero terms, has been studied—that is, Furthermore, it was assumed before that the linear part of nullifies while has at least one linear term. Thus, the degeneracy condition (12) remains valid while the functions become

and

for some and where This can be denoted by and respectively, and

Denote also by and C the sets of points in

and

for some that is sufficiently small. The expression becomes

where and Assume When and this condition is satisfied in general since Notice that

We can mentioned the following result which is proved by a similar argument as in [1], Theorem 1:

Theorem 2.

(1) The set is a smooth curve of the form

tangent to the line

(2) If the set is a reunion of two smooth curves of the form

where and If then for

(3) If the set C is a reunion of two smooth curves of the form

where and If then for

Remark 2.

In this work, it will assumed instead that and

3. Results

Analysis of degenerate Chenciner bifurcation when will be presented below, in this section.

Then

where

In the truncated case we denoted that

3.1. The Case

Associated with any of the three above 2-variables polynomials is a 1-variable polynomial, for example,

The order among the roots of , of may be only one of the following ones:

I: II: III:

IV: V: VI:

The roots are the slops of the straight lines of equations:

of the plane They are the vanishing loci of the polynomials We are interested in the configuration of the lines It is sufficient to consider only cases I and II, since the others are rotated configurations of those. The bifurcation diagram does not depend on the rotation of configurations.

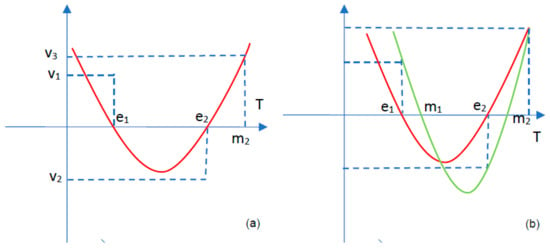

In Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 we present the graphs of for cases I and II depending on the signs of a and p.

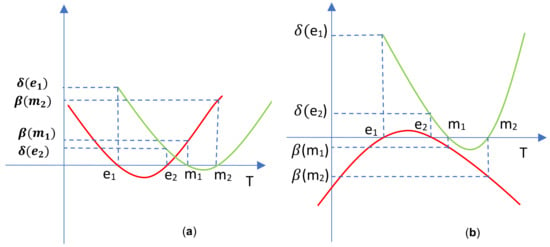

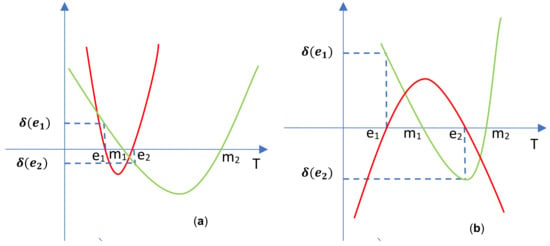

Figure 2.

The graphs of in case I: (a). ; (b). .

Figure 3.

The graphs of in case II: (a). (b). .

Figure 4.

The graphs of in case II: (a). ; (b). .

Lemma 1.

It holds,

Proof.

(1) and by the Viete relation for we get the result.

(2) For the second equality it is sufficient to use the symmetry in the triplets and □

For the sake of simplicity, we will used the notation:

Theorem 3.

In case I, if then

Proof.

In Figure 1a,b and Figure 2a,b, one may take the particular case when the two parabolas have the same symmetry axis, and that does not influence the bifurcation diagrams. That is hence

The supposition is equivalent to , and that it is equivalent to

If then (24) is equivalent to or to

or to which eventually is equivalent to □

Corollary 1.

Lemma 2.

In case II, there are examples of second degree polynomials such that E and F may have any combination of signs.

Proof.

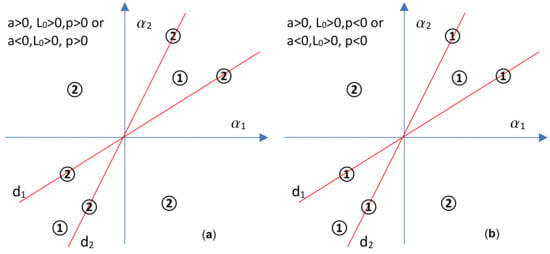

Let us consider a polynomial having , and the given numbers The sum may be positive or negative(the reasoning will be the same); see Figure 5a a for

Figure 5.

(a). The graph of when ; (b). The graph of and the graph of .

Let us consider a third positive number Then there is such that Now we will consider the parabola determined by the points

, , see Figure 5b.

That is the graph of The sum depending on , may take any value of the interval where Thus, F, which is

may be positive, or negative, and that does not depend on the sign of E, which is □

Theorem 4.

In case II:

(1) If and , then

(2) If and , then

(3) If and , then

(4) If and , then

Proof.

In all subcases 1–4: hence,

Considering , that is equivalent to (24), which is equivalent to: By multiplying (25) by (26), one gets: and hence or and that is

is equivalent to (24) or to On the other hand, by multiplying (25) by (27), is obtained: and by transitivity or which is .

(3) If then (27) is true again, and for it results in

or Multiplying (25) by (27): therefore, or which is .

(4) If then (26) is true; and if , then (28) is also true. The results show that (24) is true and multiplying (25) by (26) will be the result, and by transitivity or which is

□

Corollary 2.

Out of Theorem 4 and Lemma 2, one should deduce that case II is not possible; hence, it is eliminated.

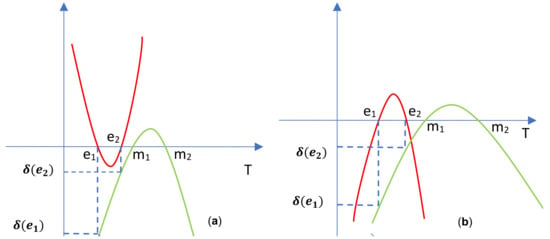

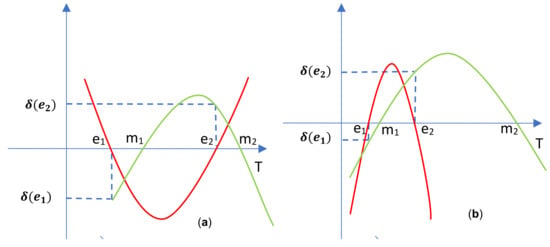

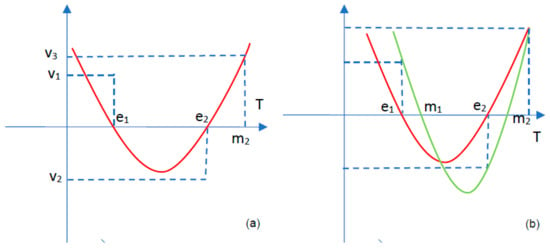

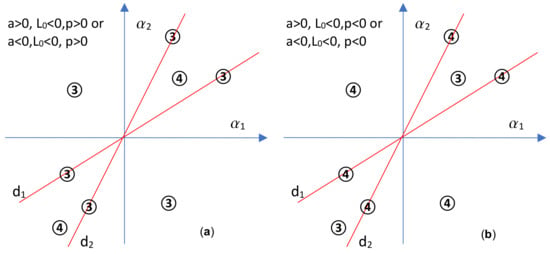

In deducing the bifurcation diagrams, one should notice that implies out of (22). The bifurcation diagrams are given in Figure 6a,b.

Figure 6.

Bifurcation diagrams for the case when : (a). or ; (b). or .

3.2. Case 2. and

In that case,

and

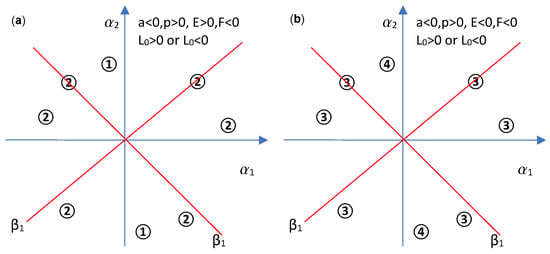

Therefore we obtained the following four bifurcation diagrams:

Figure 7.

Bifurcation diagrams in case 2, when and : (a). or ; (b). or .

Figure 8.

Bifurcation diagrams in case 2: (a). or ; (b). or .

3.3. Case 3.

Here, the signs are:

,

and

The bifurcation diagrams has a single region, which may be:

(1) Region 2 for and

(2) Region 3 for and

(3) Region 1 for and

(4) Region 4 for and

3.4. Case 4.

The rule of signs is simple: and

Moreover,

The bifurcation diagram has also a single region which may be:

(1) Region 2 for and

(2) Region 3 for and

(3) Region 1 for and

(4) Region 4 for and

The results obtained could be applied in cases of phenomena and processes (from different fields of activity—from economics, to biology or medicine and so on) for assimilation into discrete systems in which degenerate Chenciner bifurcations would be identified.

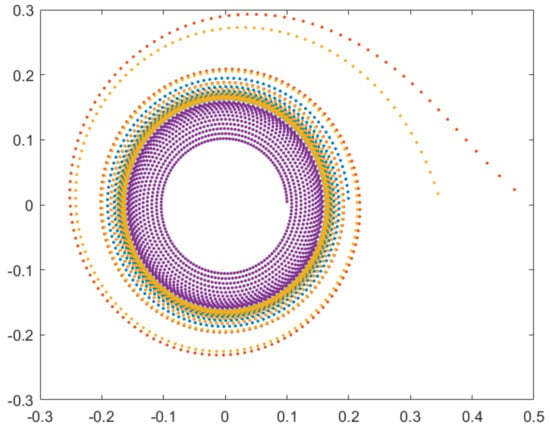

An illustrative numerical example can be presented as an application of the obtained results;

In the following we provide some numerical simulations run using MATLAB. Considering , and and taking as starting points first , then and then . Three orbits will be obtained (Figure 9). If the starting point is considered now , then the fourth orbit will appears inside of previous three orbits. The fourth orbit (magenta) departs from the origin and approximates an invariant circle. The previous three orbits approximate the same invariant closed curve, a circle like that of orbit four, when n increases to infinity. In this case the closed invariant circle is stable (Figure 9). Here so it is Case 3.3 (2), so the bifurcation diagram has a single region, region 3.

Figure 9.

The map (9) and (10) when: and and ,, and .

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

It should be noted that this study examined an issue that has not been addressed so far in the literature. This article addresses a type of Chenciner bifurcation that has not been considered before.

The present research differs from other studies by means of elements that are summarized in the following table (Table 1):

Table 1.

Comparison between previous studies and the present study.

The reasoning developed in [1] is based upon the assumption that , see Theorem 2. It is supposed greather degree of degeneracy, that is a , hence it was required of different method.

4.2. Conclusions

We presented a degeneracy case of Chenciner bifurcation written in the truncated normal form when the degeneracy condition is given by when as an answer to the open question from [1], page 10, referring to a further degeneration of . Section 3 has four subsections, and four new cases arise depending of the signum of and . The results obtained show which cases cannot happen and which are correspondences between , and the generic phase portraits.

From this study were obtained four different bifurcation diagrams, not two as, in the non-degenerate Chenciner case. The results proved in this research can be used in bifurcation theory, a field of dynamical systems which is area of applied mathematics. This research can be starting point for other practical studies that capitalize on the results obtained here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L., L.C.; Formal analysis, S.L., L.C. and E.G.; Funding acquisition, L.C., E.G.; Investigation, S.L., L.C. and E.G.; Methodology, S.L., L.C.; Project Administration, S.L., L.C. and E.G.; Supervision, S.L., L.C. and E.G.; Validation, S.L., L.C., E.G.; Visualization, S.L., L.C., E.G.; Writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; Writing—review and editing, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by Horizon 2020-2017-RISE-777911 project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tigan, G.; Lugojan, S.; Ciurdariu, L. Analysis of Degenerate Chenciner Bifurcation. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2020, 30, 2050245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidousti, J.; Eskandari, Z.; Asadipour, M. Codimension two bifurcations of discrete Bonhoeffer-van der Pool oscillator model. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 5261–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.F.; Ortega, F. An optimal equilibrium for a reformulated Samuelson economic discrete time system. Econ. Struct. 2019, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.; Bairagi, N. On the dynamic consistency of a two-species competitive discrete system with toxicity. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2020, 363, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenciner, A. Bifurcations de points fixes elliptiques. III. Orbites periodiques de “petites periodes” et elimination resonnante des couples de courbes invariantes. Inst. Hautes Etudes Sci. Publ. Math. 1988, 66, 5–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, Y.A. Elements of Applied Bifurcation Theory, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 112. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnov, Y.; Koylyshov, U.K. Symmetries in Phase Portrait. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beso, E.; Kalabusic, S.; Pilav, E. Stability of a certain class of a host-parasitoid models with a spatial refuge effect. J. Biol. Dyn. 2020, 14, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnova, V.; Pribylova, L. Two-parameter bifurcations in LPA model. J. Math. Biol. 2017, 75, 1235–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, J.; Kuttler, C. Methods and Models in Mathematical Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Dynamics of discrete epidemic models on heterogeneous networks. Phys. A 2020, 539, 122991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenciner, A. Bifurcations de points fixes elliptiques. I. Courbes invariantes. Ihes-Publ. Math. 1985, 61, 67–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenciner, A. Bifurcations de points fixes elliptiques. II. Orbites periodiques et ensembles de Cantor invariants. Invent. Math. 1985, 80, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenciner, A.; Gasull, A.; Llibre, J. Une description complete du portrait de phase d’un modele d’elimination resonante. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris Ser. I Math. 1987, 305, 623–626. [Google Scholar]

- Alidousti, J.; Eskandari, Z.; Avazzadeh, Z. Generic and symmetric bifurcations analysis of a three dimensional economic model. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 140, 110251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.F. Bifurcations of a Bouncing Ball Dynamical System. Int. Bifurc. Chaos 2019, 29, 1950191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyllenberg, M.; Jiang, J.F.; Yan, P. On the classification of generalized competitive Atkinson-Allen models via the dynamics on the boundary of the carrying simplex. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2018, 38, 615–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyllenberg, M.; Jiang, J.F.; Yan, P. On the dynamics of multi-species Ricker models admitting a carrying simplex. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2019, 25, 1489–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Singh, S. Bifurcations emerging from a double Hopf bifurcation for a BWR. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2019, 117, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, G.; Alonso, D.M.; Moiola, J.L. A Degenerate 2:3 Resonant Hopf-Hopf Bifurcations as Organizing Center of the Dynamics: Numerical Semiglobal Results. Siam J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 2015, 14, 1130–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, H.A. Interaction between the multiplier analysis and the principle of acdeleration. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1939, 21, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilnikov, L.P.; Shilnikov, A.L.; Turaev, D.V.; Chua, L.O. Methods of Qualitative Theory in Non-Linear Dynamics; Part 2; World Scientific: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.B.; Vieira, J.P.; Leonel, E.D. A new application of the normal form description to a N dimensional dynamical systems attending the conditions of a Hopf bifurcation. J. Vib. Syst. Dyn. 2018, 2, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feckan, M. Dynamics of a discrete nonlinear prey predator model, International. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2020, 30, 2050055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Vorobev, P.; Turitsyn, K. Modulated Oscillations of Synchronous Machine Nonlinear Dynamics With Saturation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 2915–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.Y.; Deng, S.F. Two codimension-two bifurcations of a second-order difference equation from macroeconomics. Discret. Contin. Dyn.-Syst.-Ser. B 2018, 23, 1581–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischi, G.I.; Dieci, R.; Rodano, G.; Saltari, E. Multiple attractors and global bifurcations in a Kaldor-type business cycle model. J. Evol. Econ. 2001, 11, 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, H. Global attractivity, oscillations and chaos in a class of nonlinear, second order difference equations. CUBO Math. J. 2005, 7, 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- El-Morshedy, H.A. On the global attractivity and oscillations in a class of second order difference equations from macroeconomics. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2011, 17, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sushko, I.; Puu, T.; Gardini, L. A Goodwin-type model with cubic investment function. In Business Cycle Dynamics Models and Tools; Puu, T., Suchko, I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 299–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sedaghat, H. A class of nonlinear second-order difference equation from macroeconomics. Nonlinear Anal. 1997, 29, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, W. Bifurcation in a second-order difference equation from macroeconomics. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 2008, 14, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommes, C.H. Heterogeneous agent models in economics and finance. In Handbook of Computational Economics; Tesfatsion, L., Judd, K.L., Eds.; Agent-Based Computational Economics; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 1109–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Kirman, A. Epidemics of opinion and speculative bubbles in financial markets. In Money and Financial Markets; Taylor, M., Ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1991; pp. 354–368. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, T. Time variation of second moments from a noise trader/infection Model. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 1997, 22, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palis, J.; Takens, F. Hyperbolicity and Sensitive chaotic Dynamics at Homoclinics Bifurcations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Honkapohja, S. Learning in Macroeconomics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gaunersdorfer, A.; Hommes, C.H.; Wagener, F.O.O. Bifurcation routes to volatility clustering under evolutionary learning. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 67, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, W.B.; Holland, J.H.; LeBaron, B.; Palmer, R.; Taylor, P. Asset pricing under endogenous expectations in an artificial stock market. In The Economy as an Evolving Complex System II; Arthur, W.B., Durlauf, S.N., Lane, D.A., Eds.; Addison-Wesley: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, S.-N.; Li, C.; Wang, D. Normal Forms and Bifurcations of Planar Vector Fields; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gils, S.A.; Horozov, E. Uniqueness of Limit Cycles in Planar Vector Fields Which Leave the Axes Invariant. Contemp. Math. 1986, 56, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Guckenheimer, J.; Holmes, P. Nonlinear Oscillations, Dynamical Systems, and Bifurcations of Vector Fields; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hommes, C.H. Financial markets as nonlinear adaptative evolutionary systems. Quant. Financ. 2001, 1, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, H.M. Nonlinear dynamical economics and chaotic motion. In Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical; System 334; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tigan, G.; Brandibur, O.; Kokovics, E.A.; Vesa, L.F. Degenerate Chenciner Bifurcation Revisited. Int. Bifurc. Chaos 2021, 31, 2150160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).