Abstract

In this paper, we introduce two novel extragradient-like methods to solve variational inequalities in a real Hilbert space. The variational inequality problem is a general mathematical problem in the sense that it unifies several mathematical models, such as optimization problems, Nash equilibrium models, fixed point problems, and saddle point problems. The designed methods are analogous to the two-step extragradient method that is used to solve variational inequality problems in real Hilbert spaces that have been previously established. The proposed iterative methods use a specific type of step size rule based on local operator information rather than its Lipschitz constant or any other line search procedure. Under mild conditions, such as the Lipschitz continuity and monotonicity of a bi-function (including pseudo-monotonicity), strong convergence results of the described methods are established. Finally, we provide many numerical experiments to demonstrate the performance and superiority of the designed methods.

1. Introduction

This paper concerns the problem of the classic variational inequality problem [1,2]. The variational inequalities problem (VIP) for an operator is defined in the following way:

where is a non-empty, convex and closed subset of a real Hilbert space and and denote an inner product and the induced norm on respectively. Moreover, are the sets of real numbers and natural numbers, respectively. It is important to note that the problem (VIP) is equivalent to solving the following problem:

The idea of variational inequalities has been used by an antique mechanism to consider a wide range of topics, i.e., engineering, physics, optimization theory and economics. It is an important mathematical model that unifies a number of different mathematics problems such as the network equilibrium problem, the necessary optimality conditions, systems of non-linear equations and the complementarity problems (for further details [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]). This problem was introduced by Stampacchia [2] in 1964 and also demonstrated that the problem (VIP) had a key position in non-linear analysis. There are many researchers who have studied and considered many projection methods (see for more details [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]). Korpelevich [13] and Antipin [21] established the following extragradient method:

Recently, the subgradient extragradient method was introduced by Censor et al. [10] for solving the problem (VIP) in a real Hilbert space. It has the following form:

where

It is important to mention that the above well-established method carries two serious shortcomings, the first one is the fixed step size that involves the knowledge or approximation of the Lipschitz constants of the related mapping and it only converges weakly in Hilbert spaces. From the computational point of view, it might be questionable to use fixed step size, and hence the convergence rate and usefulness of the method could be affected.

The main objective of this paper is to introduce inertial-type methods that are used to strengthen the convergence rate of the iterative sequence in this context. Such methods have been previously established due to the oscillator equation with a damping and conservative force restoration. This second-order dynamical system is called a heavy friction ball, which was originally studied by Polyak in [22]. Mainly, the functionality of the inertial-type method is that it will use the two previous iterations for the next iteration. Numerical results support that inertial term usually improves the functioning of the methods in terms of the number of iterations and elapsed time in this sense, and that inertial-type method has been broadly studied in [23,24,25].

So a natural question arises:

“Is it possible to introduce a new inertial-type strongly convergent extragradient-like method with a monotone variable step size rule to solve problem (VIP)”?

In this study, we provide a positive answer of this question, i.e., the gradient method still generates a strong convergence sequence by using a fixed and variable step size rule for solving a problem (VIP) associated with pseudo-monotone mappings. Motivated by the works of Censor et al. [10] and Polyak [22], we introduce a new inertial extragradient-type method to solve the problem (VIP) in the setting of an infinite-dimensional real Hilbert space.

In brief, the key points of this paper are set out as follows:

- (i)

- We propose an inertial subgradient extragradient method by using a fixed step size to solve the variational inequality problem in real Hilbert space and confirm that a generated sequence is strongly convergent.

- (ii)

- We also create a second inertial subgradient extragradient method by using a variable monotone step size rule independent of the Lipschitz constant to solve pseudomonotone variational inequality problems.

- (iii)

- Numerical experiments are presented corresponding to proposed methods for the verification of theoretical findings, and we compare them with the results in [Algorithm 3.4 in [23]], [Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25]]. Our numerical data has shown that the proposed methods are useful and performed better as compared to the existing ones.

The rest of the article is arranged as follows: The Section 2 includes the basic definitions and important lemmas that are used in the manuscript. Section 3 consists of inertial-type iterative schemes and convergence analysis theorems. Section 4 provided the numerical findings to explain the behaviour of the new methods and in comparison with other methods.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we have written a number of important identities and relevant lemmas and definitions. A metric projection of is defined by

Next, we list some of the important properties of the projection mapping.

Lemma 1.

[26] Suppose that is a metric projection. Then, we have

- (i)

- if and only if

- (ii)

- (iii)

Lemma 2.

[27] Let be a sequence satisfying the following inequality

Furthermore, and be two sequences such that

Then,

Lemma 3.

[28] Assume that is a sequence and there exist a subsequence of such that

Then, there exists a non decreasing sequence such that as and satisfying the following inequality for numbers :

Indeed,

Next, we list some of the important identities that were used to prove the convergence analysis.

Lemma 4.

[26] For any and . Then, the following inequalities hold.

- (i)

- (ii)

Lemma 5.

[29] Assume that is a continuous and pseudo-monotone mapping. Then, solves the problem (VIP) iff is the solution of the following problem:

3. Main Results

Now, we introduce both inertial-type subgradient extragradient methods which incorporate a monotone step size rule and the inertial term and provide both strong convergence theorems. The following two main results are outlined as Algorithms 1 and 2:

| Algorithm 1 Inertial-type strongly convergent iterative scheme. |

|

In order to study the convergence analysis, we consider that the following condition have been satisfied:

- (B1)

- The solution set of problem (VIP), denoted by is non-empty;

- (B2)

- An operator is called to be pseudo-monotone, i.e.,

- (B3)

- An operator is called to be Lipschitz continuous through a constant , i.e., there exists such that

- (B4)

- An operator is called to be weakly sequentially continuous, i.e., converges weakly to for every sequence converges weakly to u.

| Algorithm 2 Explicit Inertial-type strongly convergent iterative scheme. |

|

Lemma 6.

Assume that satisfies the conditions (B1)–(B4) in Algorithm 1. For each we have

Proof.

First, consider the following

It is given that such that

which implies that

It is given that we obtain

By the use of pseudo-monotonicity of mapping on , we obtain

Let consider we obtain

Thus, we have

It is given that , we have

□

Theorem 1.

Let be a sequence generated by Algorithm 1 and satisfies the conditions (B1)–(B4). Then, strongly converges to . Moreover,

Proof.

It is given in expression (3) that

By the use of Lemma 6, we obtain

Thus, we conclude that the is bounded sequence. Indeed, by (14) we have

for some Combining the expressions (11) with (17), we have

Due to the Lipschitz-continuity and pseudo-monotonicity of implies that is a closed and convex set. It is given that and by using Lemma 1 (ii), we have

The rest of the proof is divided into the following parts:

Case 1: Now consider that a number such that

Thus, above implies that exists and let , for some From the expression (18), we have

Due to existence of a limit of sequence and , we infer that

By the use of expression (22), we have

Next, we will evaluate

Thus above implies that

The above explanation guarantees that the sequences and are also bounded. By the use of reflexivity of and the boundedness of guarantees that there exits a subsequence such that as Next, we have to prove that It is given that that is equivalent to

The inequality described above implies that

Thus, we obtain

Due to boundedness of the sequence implies that is also bounded. By the use of and in (28), we obtain

Moreover, we have

Let us consider a sequence of positive numbers that is decreasing and converges to zero. For each k, we denote by the smallest positive integer such that

Due to is decreasing and is increasing.

Case I: If there is a subsequence of such that (). Let we obtain

Thus, and imply that .

Case II: If there exits such that for all , Consider that

Due to the above definition, we obtain

Due to the pseudomonotonicity of for we have

For all we have

Due to weakly converges to through is sequentially weakly continuous on the set , we get weakly converges to Suppose that , we have

Since and we have

Next, consider in (39), we obtain

By the use of Minty Lemma 5, we infer Next, we have

By the use of . Thus, (43) implies that

Consider the expression (13), we have

Case 2: Consider that there exists subsequence of such that

By using Lemma 3 there exists a sequence as such that

As in Case 1, the relation (21) gives that

Due to , we deduce the following:

It follows that

Next, we evaluate

It follows that

By using the same explanation as in the Case 1, such that

Thus, above implies that

It implies that

As a consequence This completes the proof of the theorem. □

Lemma 7.

Assume that satisfies the conditions (B1)–(B4) in Algorithm 2. For each we have

Proof.

Consider that

It is given that we obtain

which implies that

Thus, we have

By the use of condition (B2), we have

Take we obtain

Thus, we have

Note that and by the definition of , we have

□

Theorem 2.

Let be a sequence generated by Algorithm 2 and satisfies the conditions (B1)–(B4). Then, strongly converges to . Moreover,

Proof.

From Lemma 7, we have

It is given that such that we have

Therefore, there exists in order that

Thus, implies that

Next, we follow the same steps as in the proof of Theorem 1. □

4. Numerical Illustrations

This section examines four numerical experiments to show the efficacy of the proposed algorithms. Any of these numerical experiments provide a detailed understanding of how better control parameters can be chosen. Some of them show the advantages of the proposed methods compared to existing ones in the literature.

Example 1.

Firstly, consider the HpHard problem that is taken from [30] and this example was studied by many authors for numerical experiments (see for details [31,32,33]). Let be a mapping is defined by

where and

where B is an skew-symmetric matrix, N is an matrix and D is a diagonal positive definite matrix. The set is taken in the following way:

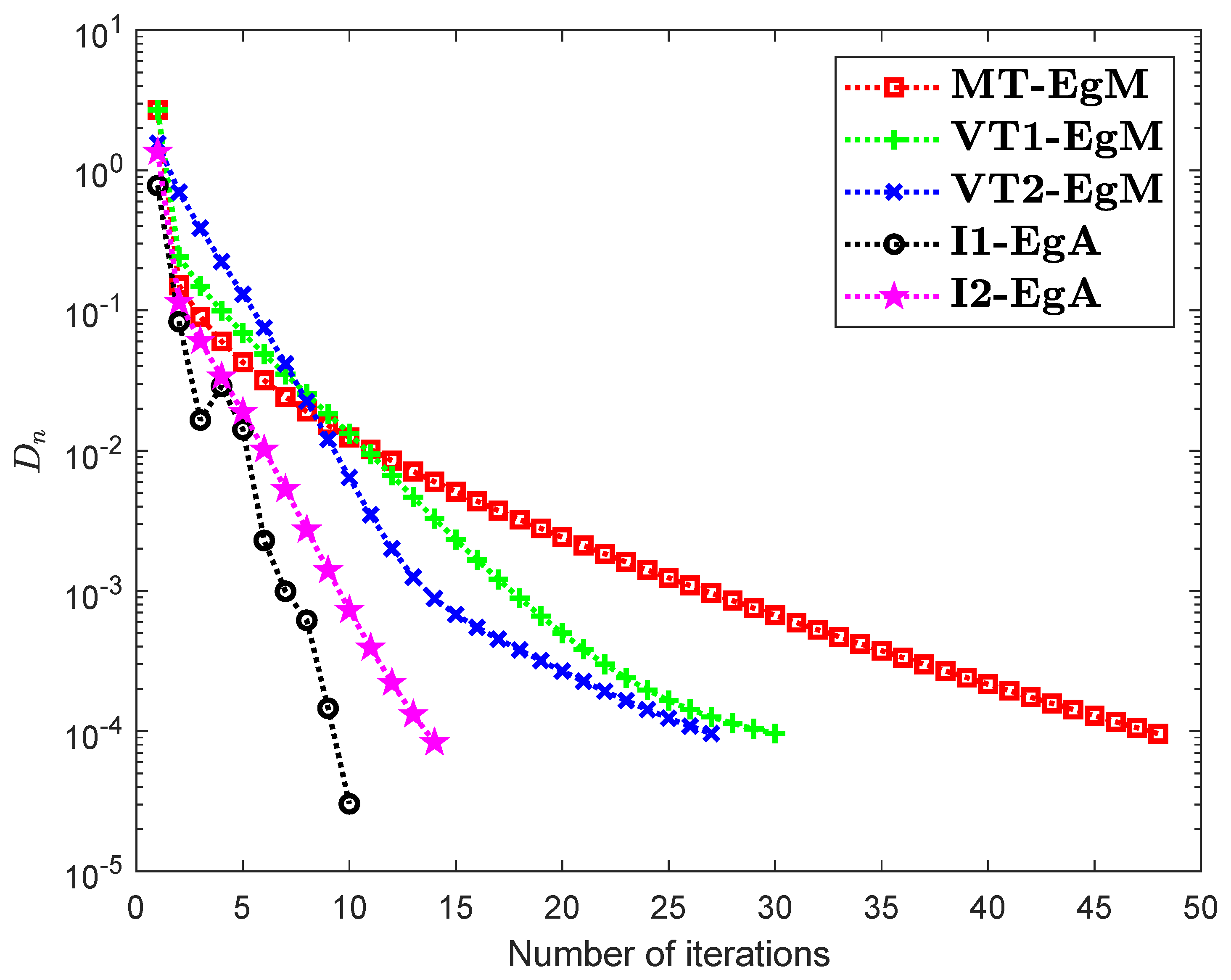

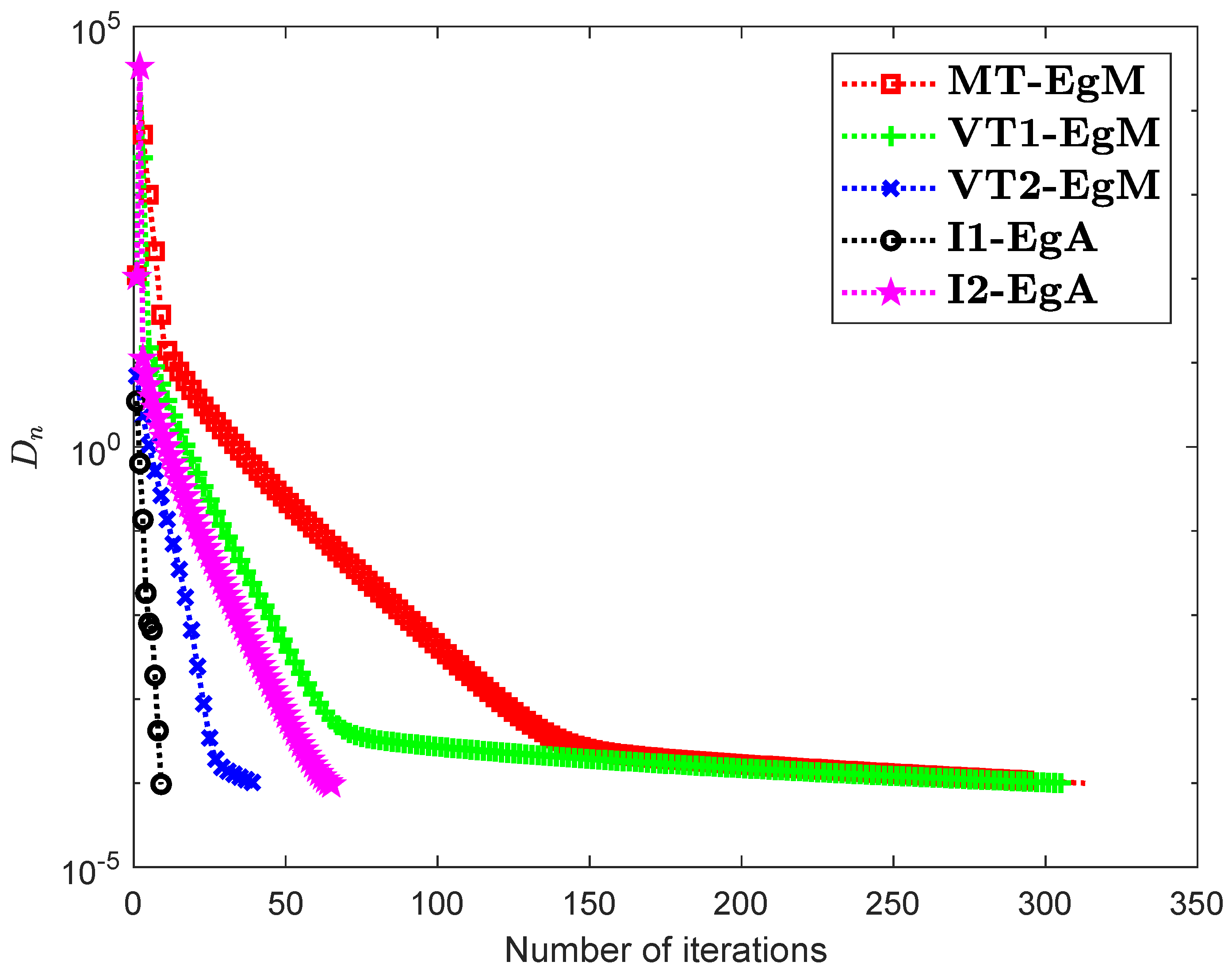

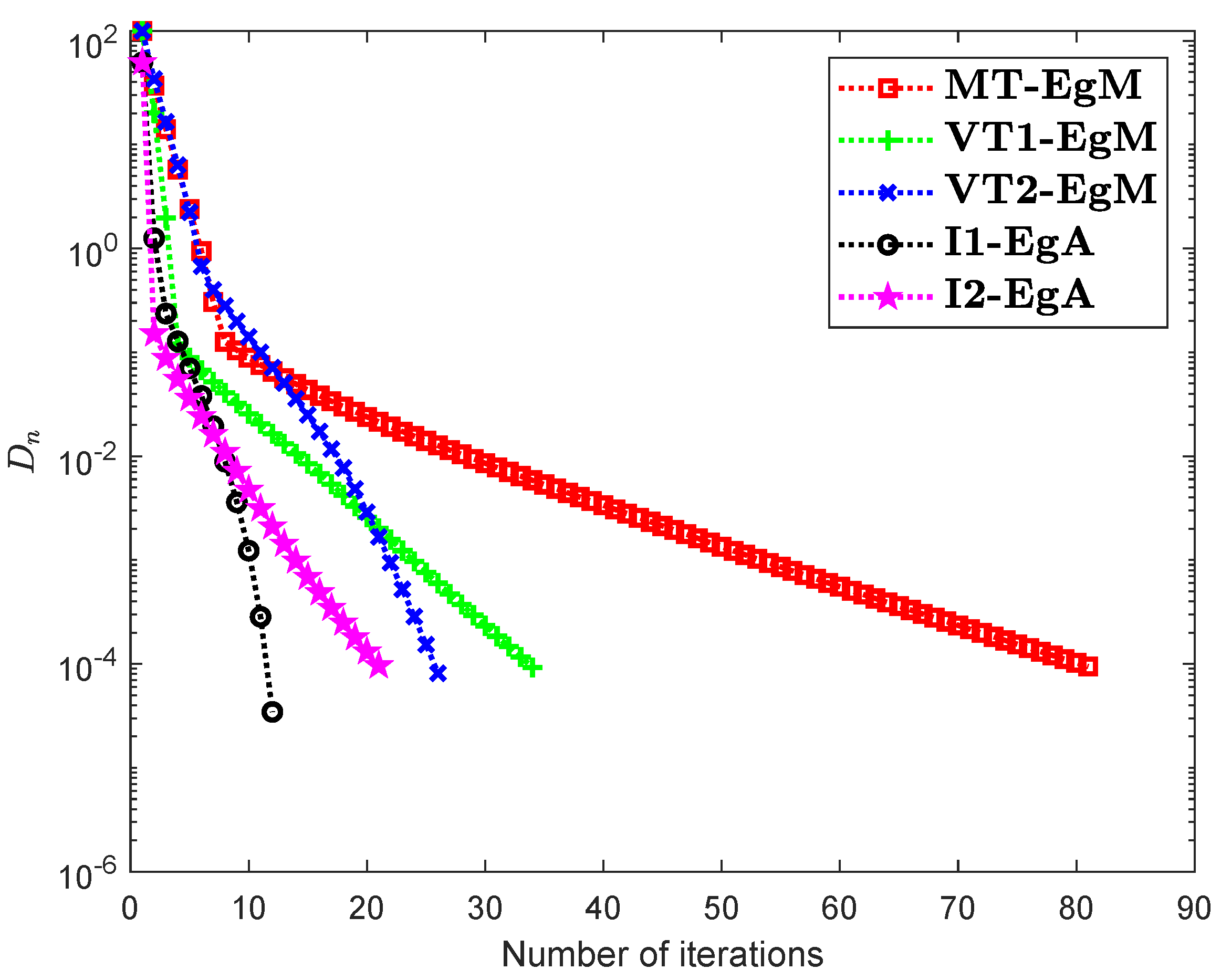

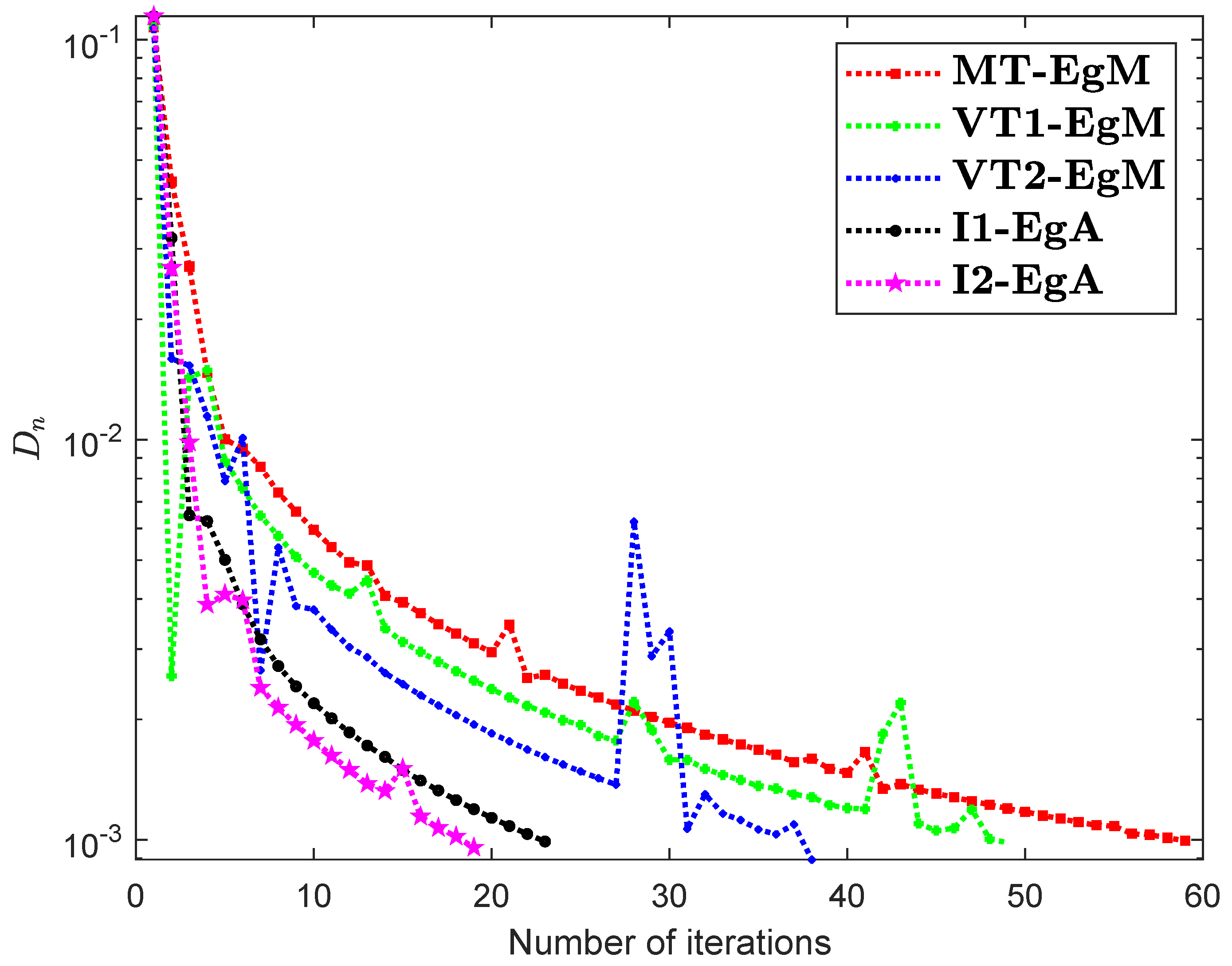

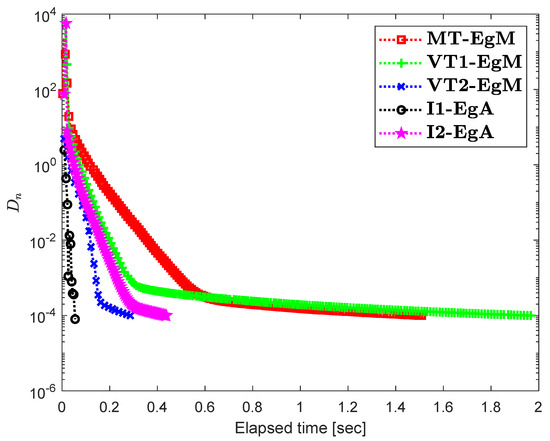

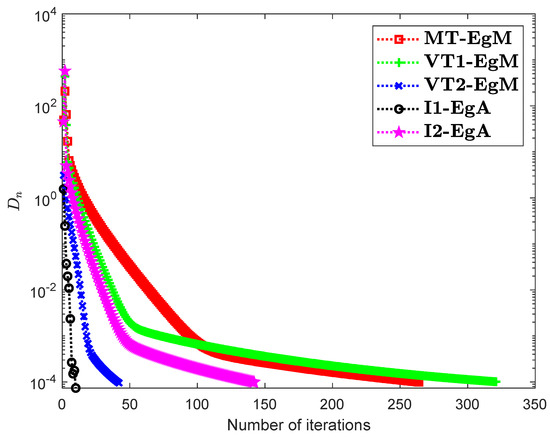

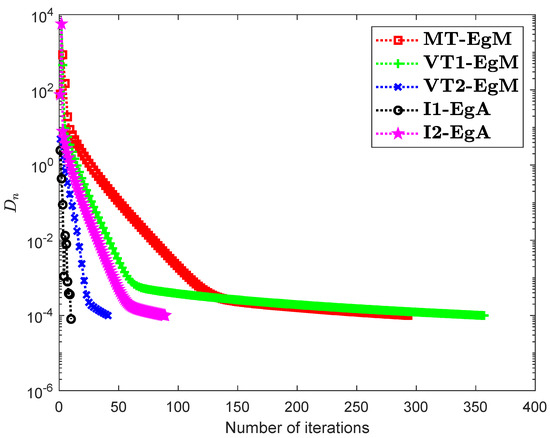

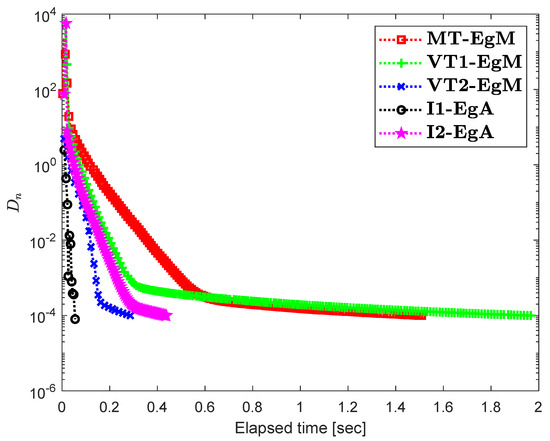

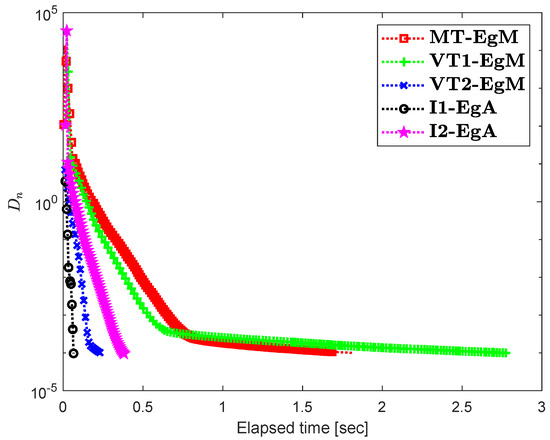

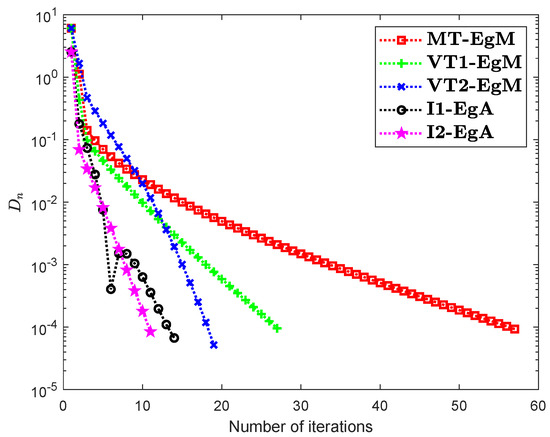

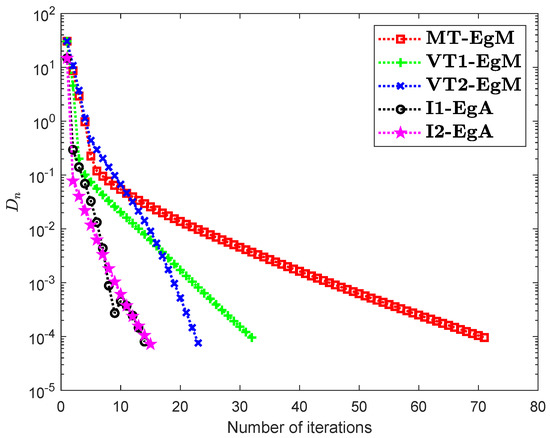

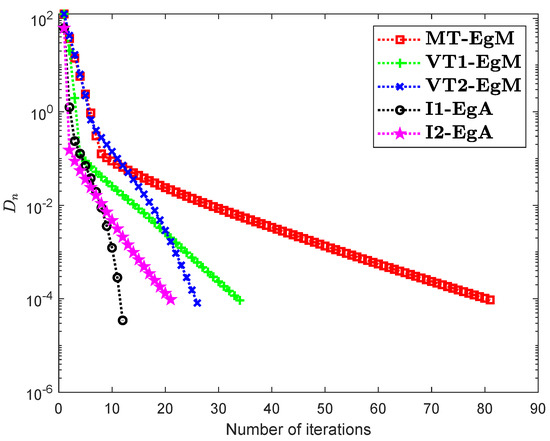

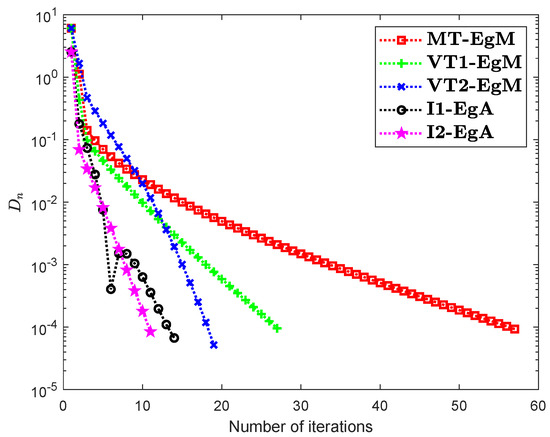

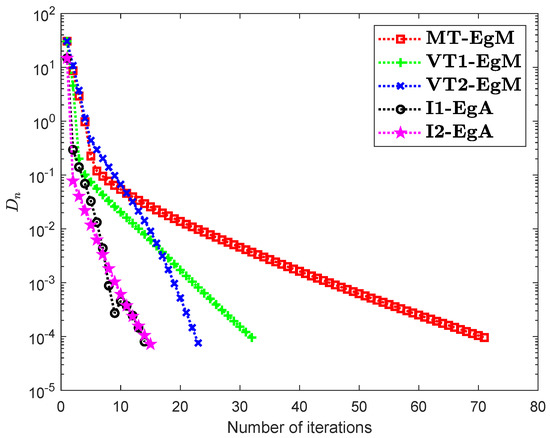

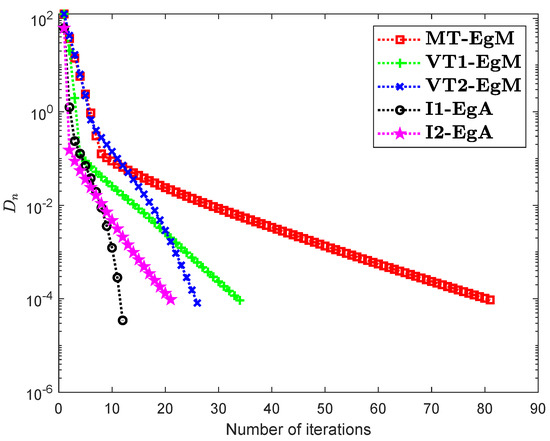

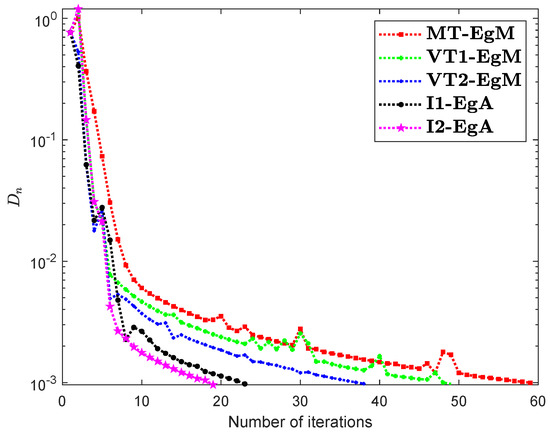

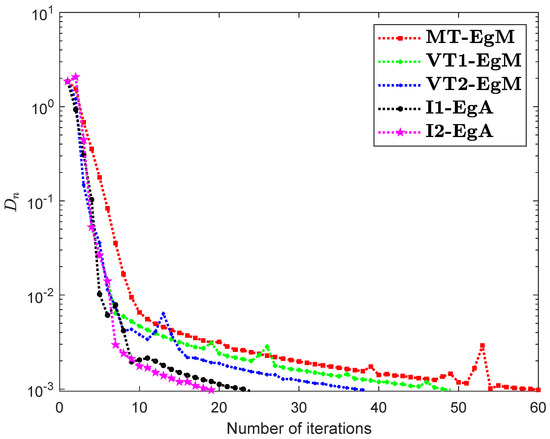

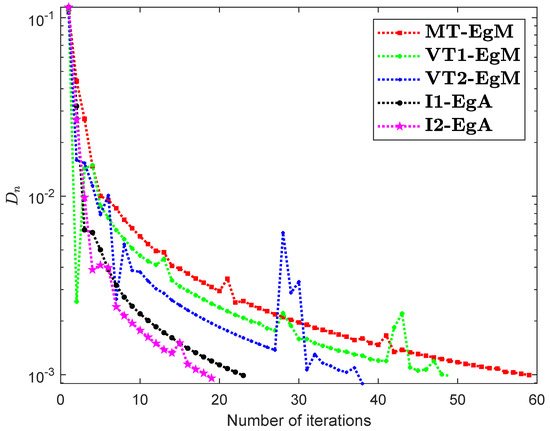

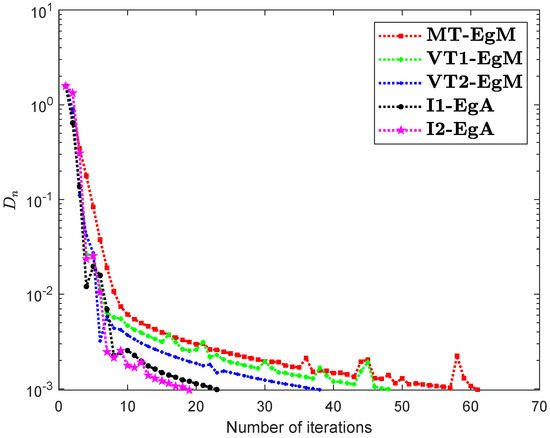

It is clear that is monotone and Lipschitz continuous through For , the solution set of the corresponding variational inequality problem is . During this experiment, the initial point is and The numerical findings of these methods are shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 and Table 1. The control conditions are taken as follows:

Figure 1.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when

Figure 2.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when

Figure 3.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when

Figure 4.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when

Figure 5.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when

Figure 6.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when

- (i)

- Algorithm 3.4 in [23] (shortly, MT-EgM):

- (ii)

- Algorithm 3.2 in [24] (shortly, VT1-EgM):

- (iii)

- Algorithm 3.1 in [25] (shortly, VT2-EgM):

- (iv)

- Algorithm 1 (shortly, I1-EgA):

- (v)

- Algorithm 2 (shortly, I2-EgA):

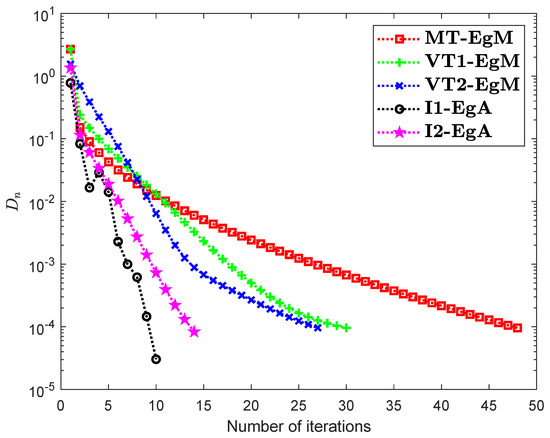

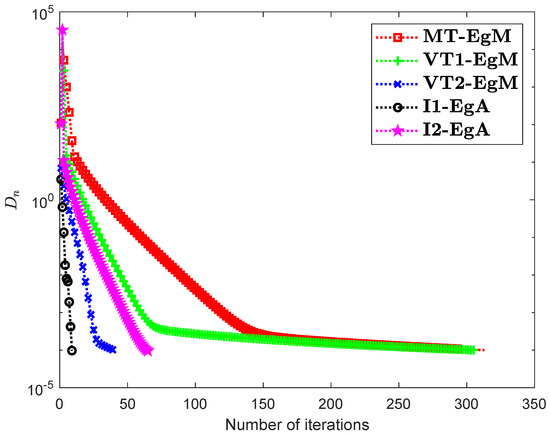

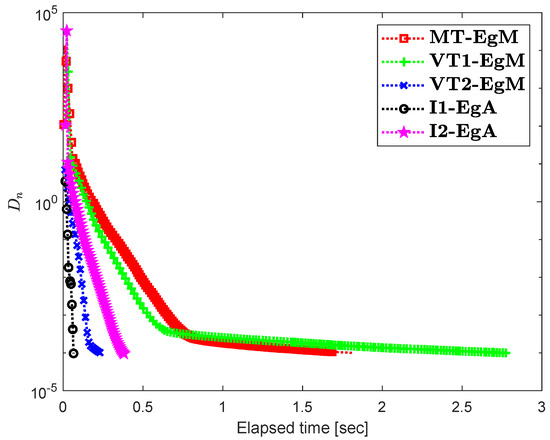

Example 2.

Assume that is a Hilbert space with an inner product

and norm is defined by

Consider that the set is a unit ball. Let is defined by

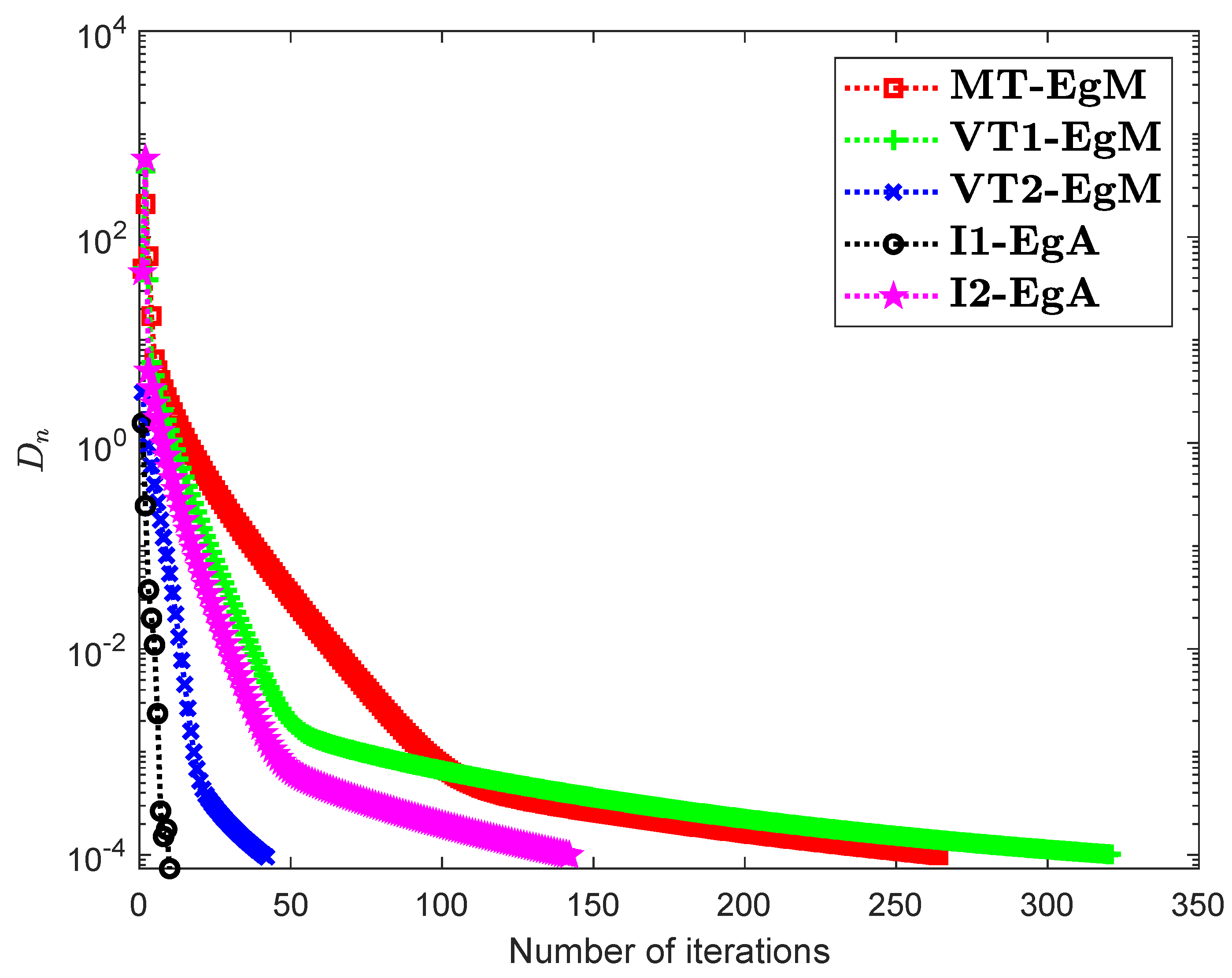

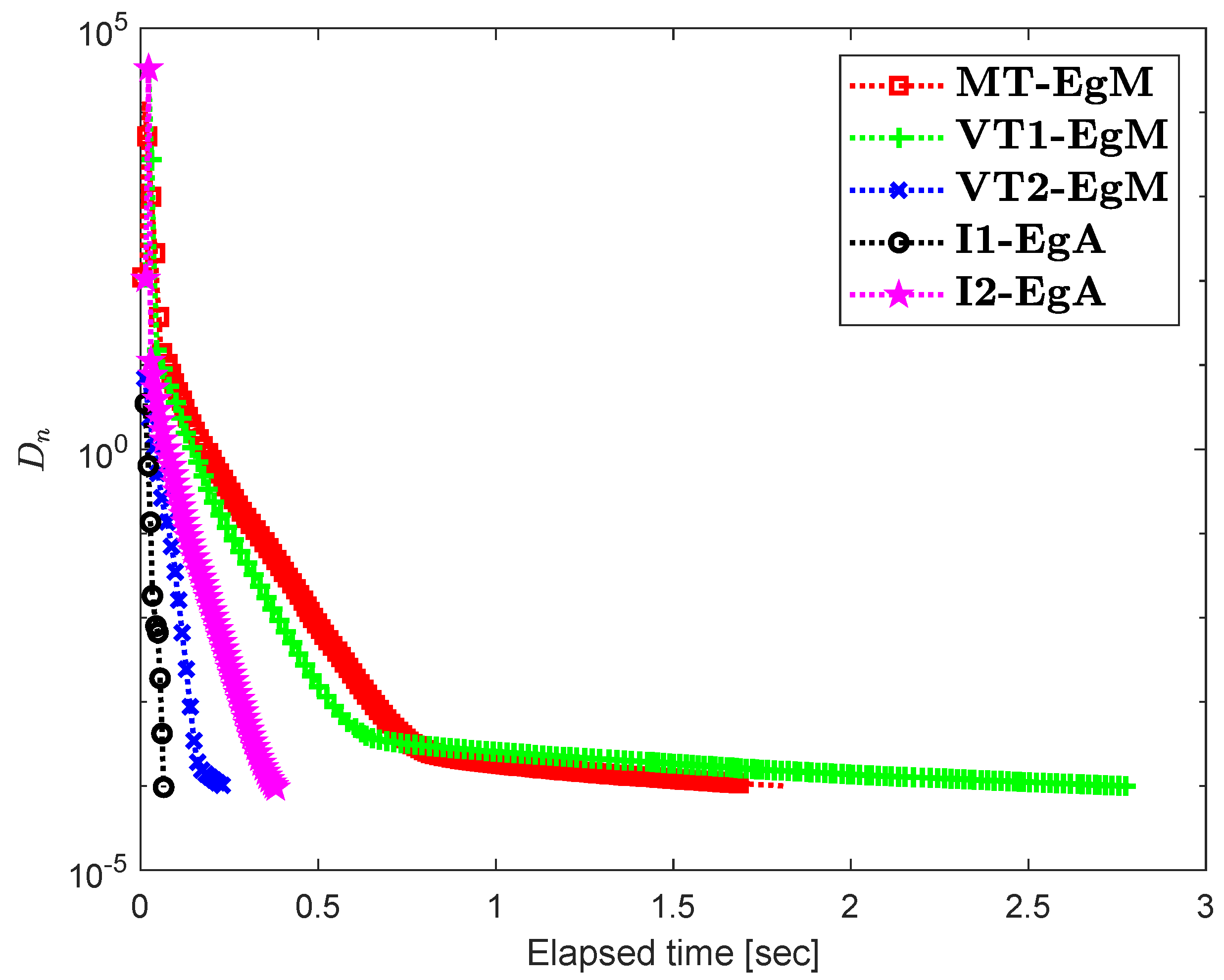

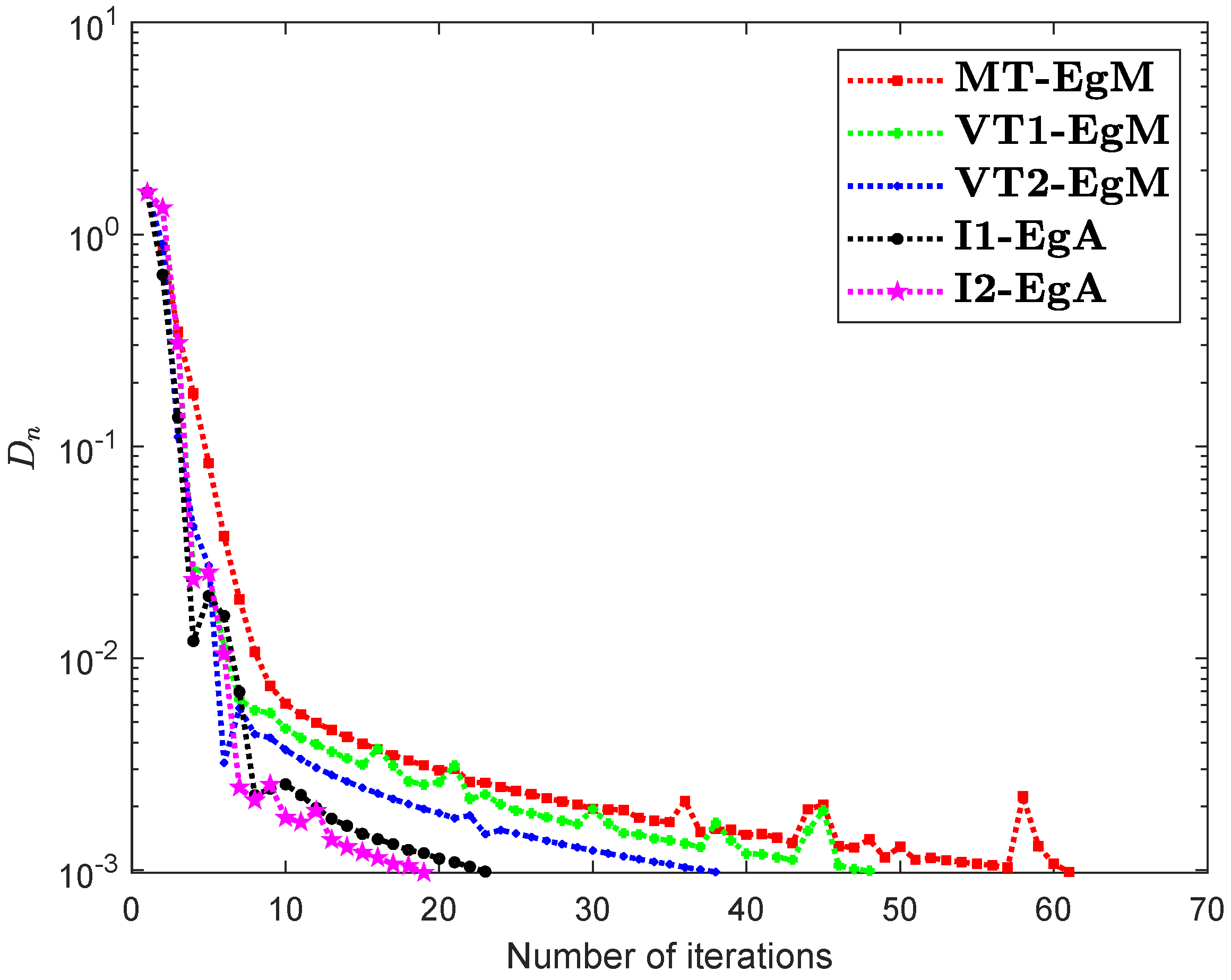

where

It can be seen that is Lipschitz-continuous with Lipschitz constant and monotone. Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 and Table 2 show the numerical results by choosing different choices of . The control conditions are taken as follows:

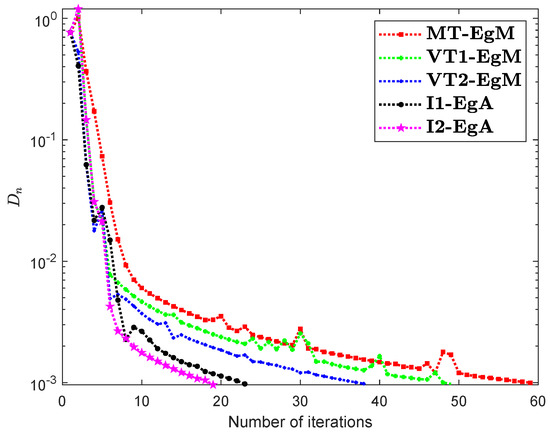

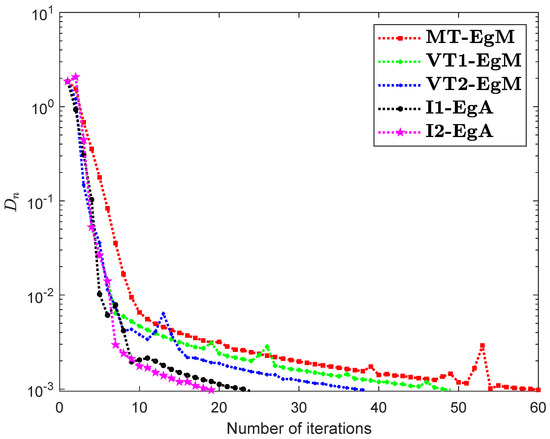

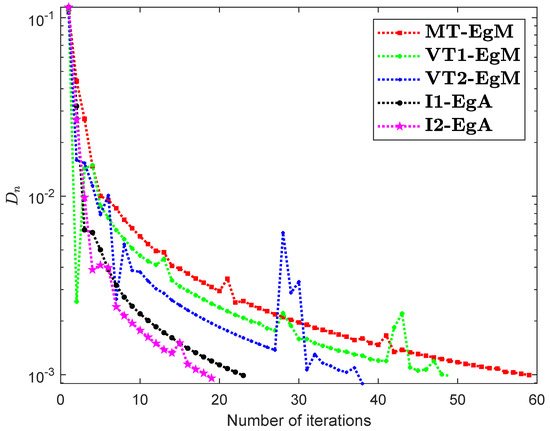

Figure 7.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when .

Figure 8.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when .

Figure 9.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when .

- (i)

- Algorithm 3.4 in [23] (shortly, MT-EgM):

- (ii)

- Algorithm 3.2 in [24] (shortly, VT1-EgM):

- (iii)

- Algorithm 3.1 in [25] (shortly, VT2-EgM):

- (iv)

- Algorithm 1 (shortly, I1-EgA):

- (v)

- Algorithm 2 (shortly, I2-EgA):

Example 3.

Consider that the problem of Kojima–Shindo where the constraint set is

and the mapping is defined by

It is easy to see that is not monotone on the set By using the Monte-Carlo approach [34], it can be shown that is pseudo-monotone on This problem has a unique solution Actually, in general, it is a very difficult task to check the pseudomonotonicity of any mapping in practice. We here employ the Monte Carlo approach according to the definition of pseudo-monotonicity: Generate a large number of pairs of points u and y uniformly in satisfying and then check if . Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 show the numerical results by taking different values of . The control conditions are taken as follows:

Table 3.

Example 3: Numerical findings of Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and .

Table 4.

Example 3: Numerical findings of Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and .

Table 5.

Example 3: Numerical findings of Algorithm 2 and .

Table 6.

Example 3: Numerical findings of Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and .

Table 7.

Example 3: Numerical findings of Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and .

Table 8.

Example 3: Numerical findings of Algorithm 2 and .

- (i)

- Algorithm 3.4 in [23] (shortly, MT-EgM):

- (ii)

- Algorithm 3.2 in [24] (shortly, VT1-EgM):

- (iii)

- Algorithm 3.1 in [25] (shortly, VT2-EgM):

- (iv)

- Algorithm 1 (shortly, I1-EgA):

- (v)

- Algorithm 2 (shortly, I2-EgA):

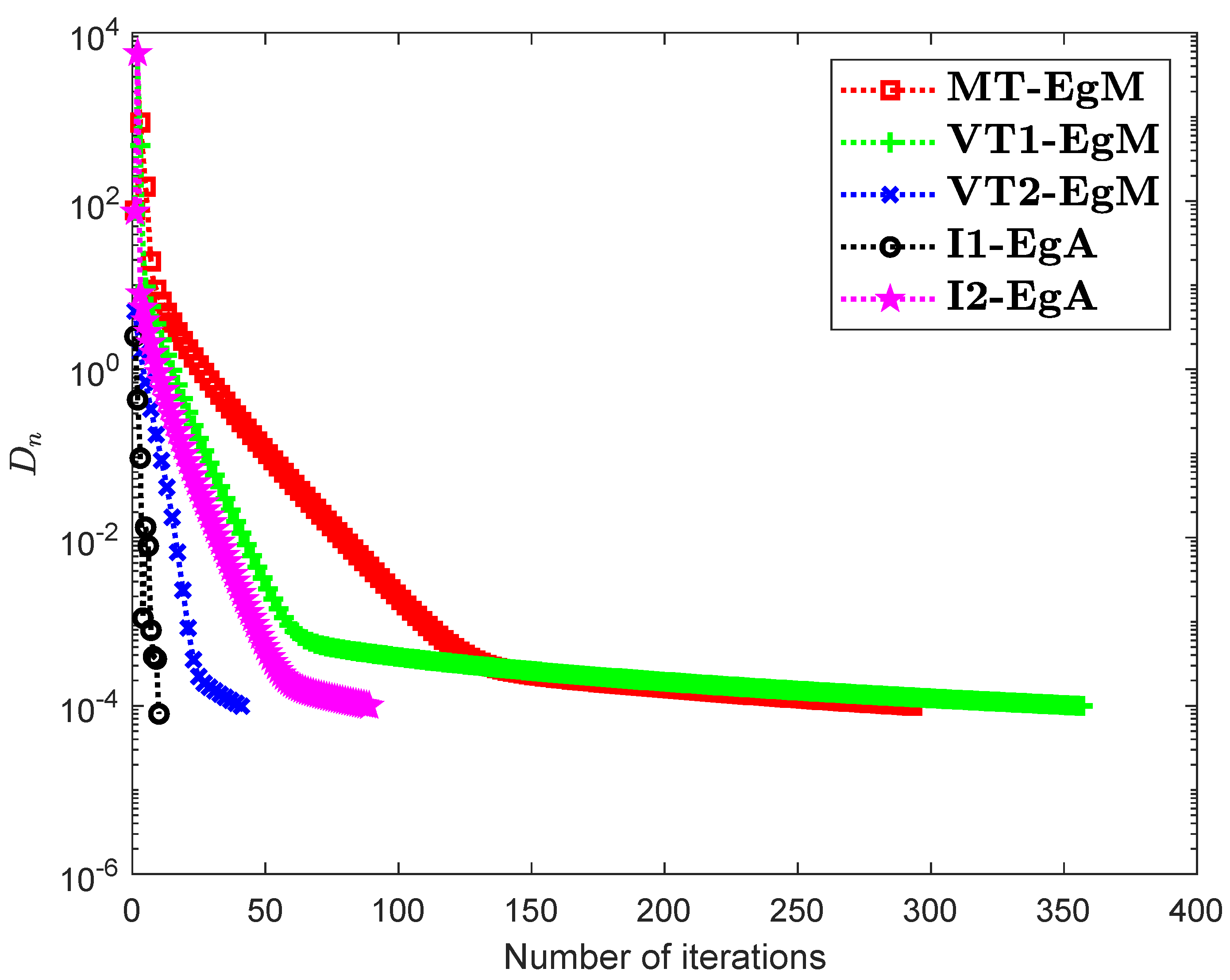

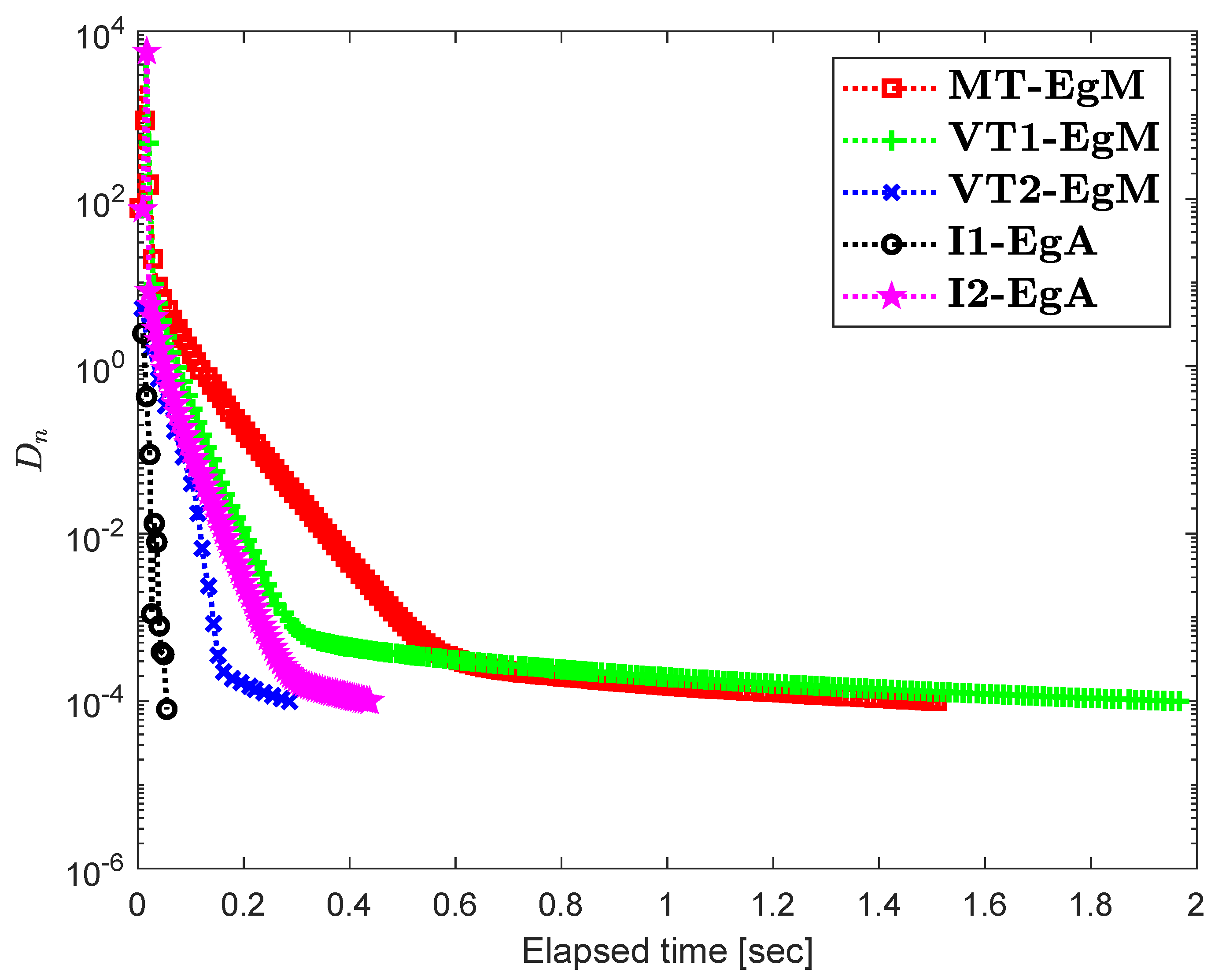

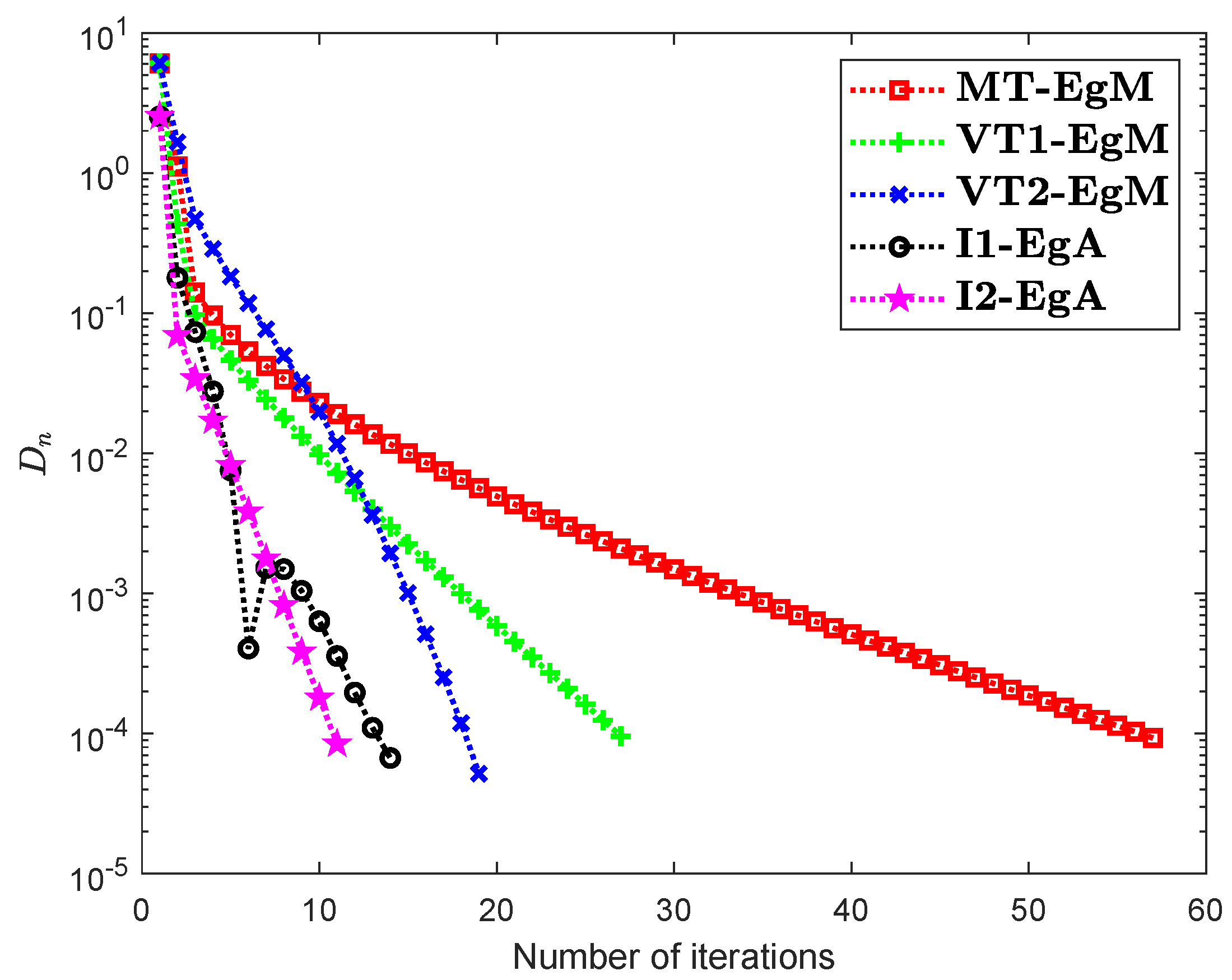

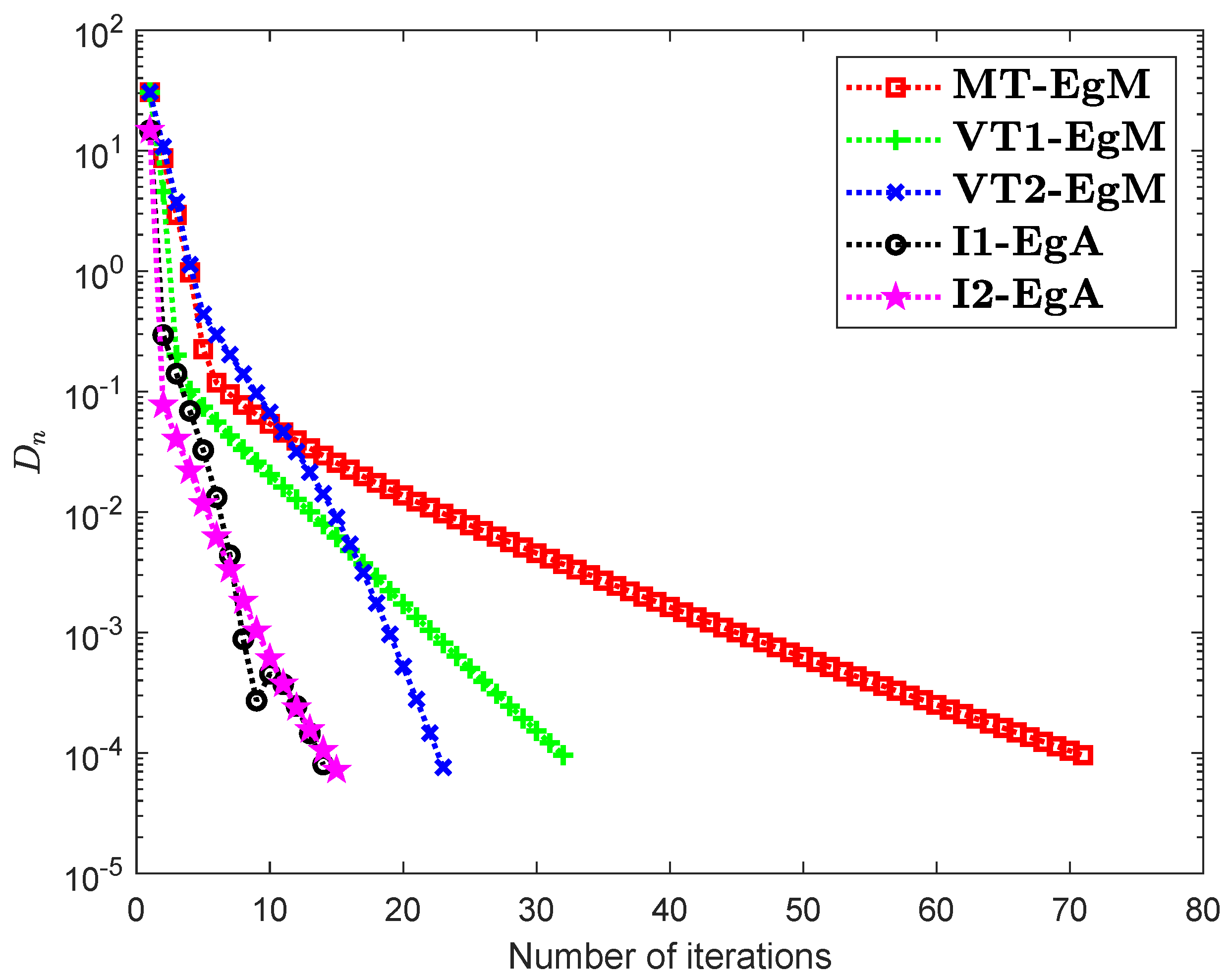

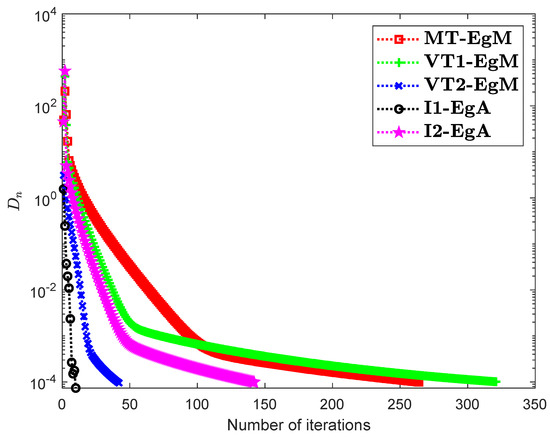

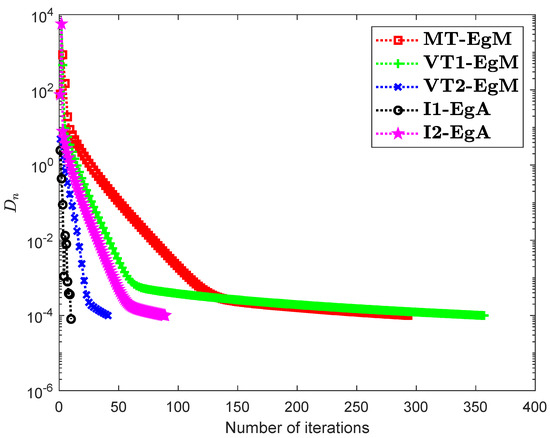

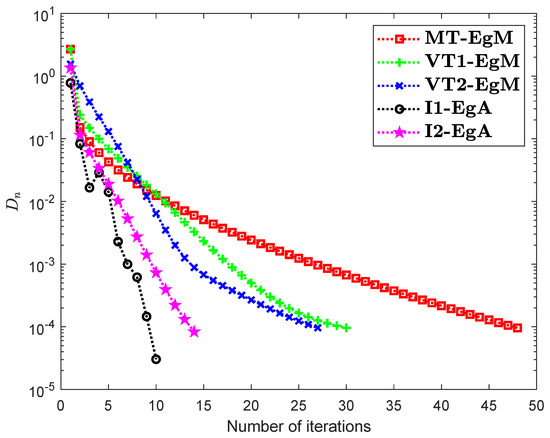

Example 4.

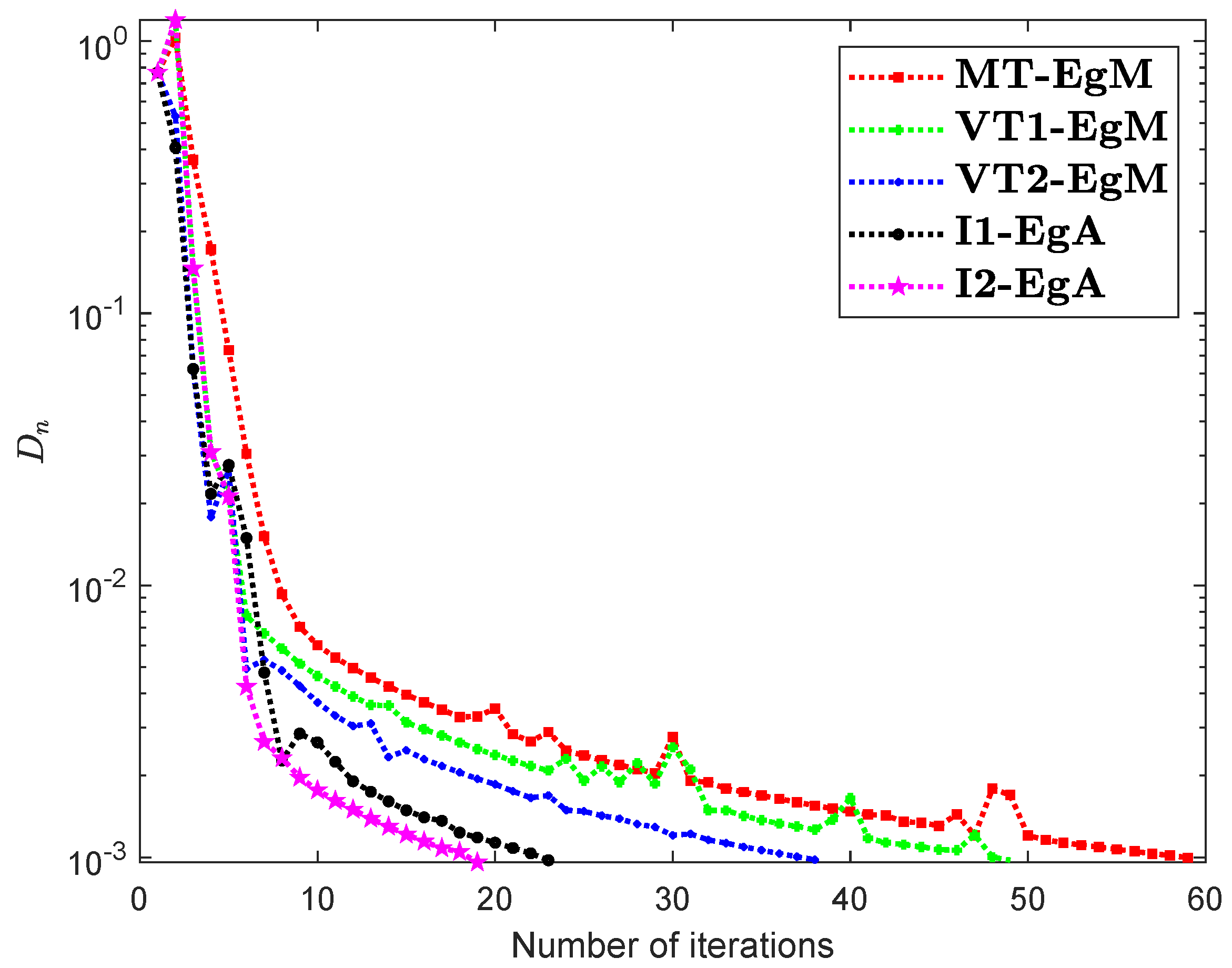

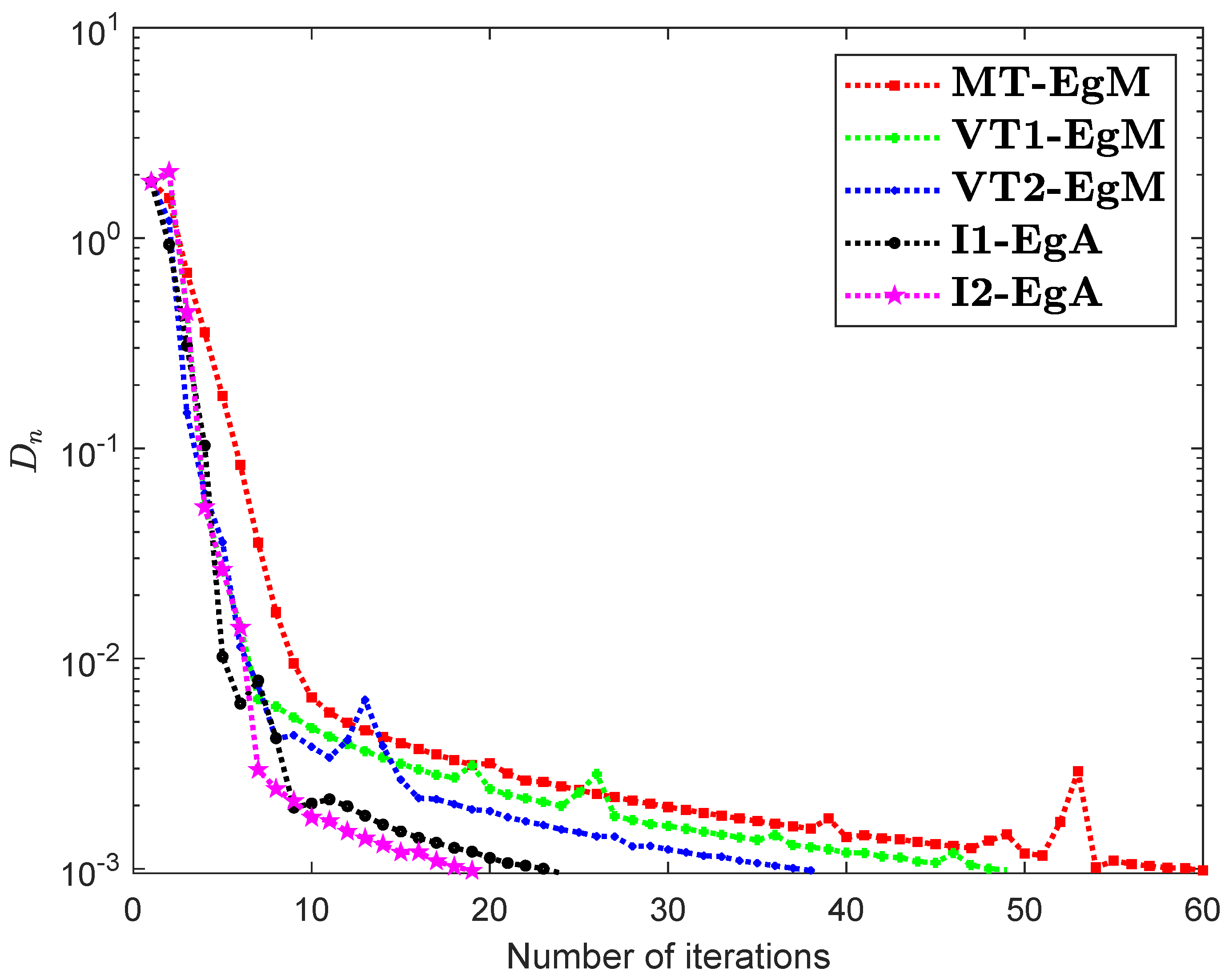

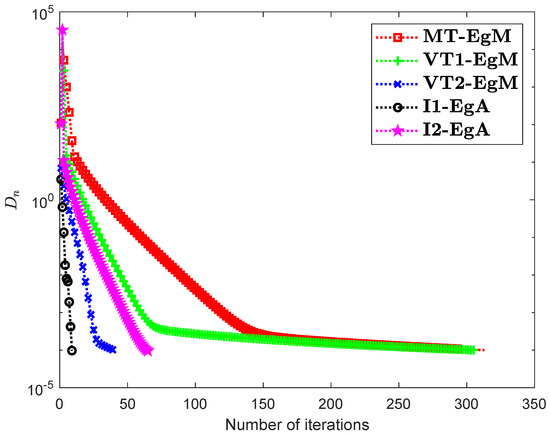

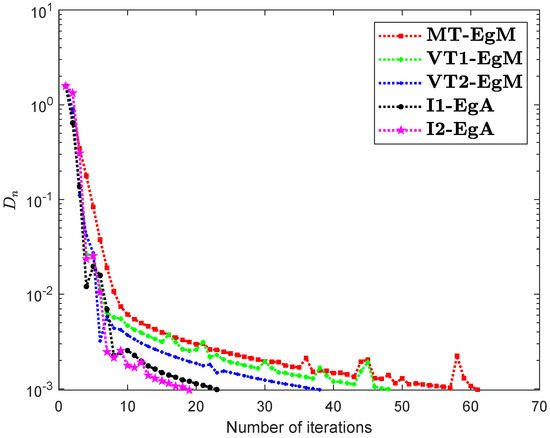

The last Example has taken from [35] where is defined by

where It can easily see that is Lipschitz continuous with and is not monotone on but pseudomonotone. Here, the above problem has unique solution Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 and Table 9 show the numerical findings by letting different values of . The control conditions are taken as follows:

Figure 10.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when .

Figure 11.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when .

Figure 12.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when .

Figure 13.

Numerical illustration of Algorithms 1 and 2 with Algorithm 3.4 in [23] and Algorithm 3.2 in [24] and Algorithm 3.1 in [25] when .

- (i)

- Algorithm 3.4 in [23] (shortly, MT-EgM):

- (ii)

- Algorithm 3.2 in [24] (shortly, VT1-EgM):

- (iii)

- Algorithm 3.1 in [25] (shortly, VT2-EgM):

- (iv)

- Algorithm 1 (shortly, I1-EgA):

- (v)

- Algorithm 2 (shortly, I2-EgA):

5. Conclusions

In this study, we have introduced two new methods for finding a solution of variational inequality problem in a Hilbert space. The results have been established on the base of two previous methods: the subgradient extragradient method and the inertial method. Some new approaches to the inertial framework and the step size rule have been set up. The strong convergence of our proposed methods is set up under the condition of pseudo-monotonicity and Lipschitz continuity of mapping. Some numerical results are presented to explain the convergence of the methods over others. The results in this paper have been used as methods for figuring out the variational inequality problem in Hilbert spaces. Finally, numerical experiments indicate that the inertial approach normally enhances the performance of the proposed methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M., N.A.A. and I.K.A.; methodology, K.M. and N.A.A.; software, K.M., N.A.A. and I.K.A.; validation, N.A.A. and I.K.A.; formal analysis, K.M. and N.A.A.; investigation, K.M., N.A.A. and I.K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M., N.A.A. and I.K.A.; writing—review and editing, K.M., N.A.A. and I.K.A.; visualization, K.M., N.A.A. and I.K.A.; supervision and funding, K.M. and I.K.A. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This first author was supported by Rajamangala University of Technology Phra Nakhon (RMUTP).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Konnov, I.V. On systems of variational inequalities. Russ. Math. C/C Izv. Vyss. Uchebnye Zaved. Mat. 1997, 41, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Stampacchia, G. Formes bilinéaires coercitives sur les ensembles convexes. Comptes Rendus Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1964, 258, 4413. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, C.M. Variational and quasivariational inequalities applications to free—boundary ProbLems. (claudio baiocchi and antónio capelo). SIAM Rev. 1987, 29, 314–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassay, G.; Kolumbán, J.; Páles, Z. On nash stationary points. Publ. Math. 1999, 54, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kassay, G.; Kolumbán, J.; Páles, Z. Factorization of minty and stampacchia variational inequality systems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 143, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinderlehrer, D.; Stampacchia, G. An Introduction to Variational Inequalities and Their Applications; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Konnov, I. Equilibrium Models and Variational Inequalities; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 210. [Google Scholar]

- Nagurney, A.; Economics, E.N. A Variational Inequality Approach; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, W. Introduction to Nonlinear and Convex Analysis; Yokohama Publishers: Yokohama, Japan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Censor, Y.; Gibali, A.; Reich, S. The subgradient extragradient method for solving variational inequalities in Hilbert space. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2010, 148, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Censor, Y.; Gibali, A.; Reich, S. Extensions of korpelevich extragradient method for the variational inequality problem in euclidean space. Optimization 2012, 61, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iusem, A.N.; Svaiter, B.F. A variant of korpelevich’s method for variational inequalities with a new search strategy. Optimization 1997, 42, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpelevich, G. The extragradient method for finding saddle points and other problems. Matecon 1976, 12, 747–756. [Google Scholar]

- Malitsky, Y.V.; Semenov, V.V. An extragradient algorithm for monotone variational inequalities. Cybern. Syst. Anal. 2014, 50, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudafi, A. Viscosity approximation methods for fixed-points problems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2000, 241, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M.A. Some iterative methods for nonconvex variational inequalities. Comput. Math. Model. 2010, 21, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, D.V.; Hieu, D.V. Modified subgradient extragradient method for variational inequality problems. Numer. Algorithms 2017, 79, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, D.V.; Hieu, D.V. Weak and strong convergence theorems for variational inequality problems. Numer. Algorithms 2017, 78, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P. A modified forward-backward splitting method for maximal monotone mappings. SIAM J. Control Optim. 2000, 38, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fang, C.; Chen, S. An inertial subgradient-type method for solving single-valued variational inequalities and fixed point problems. Numer. Algorithms 2018, 79, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipin, A.S. On a method for convex programs using a symmetrical modification of the lagrange function. Ekon. Mat. Metod. 1976, 12, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar]

- Polyak, B. Some methods of speeding up the convergence of iteration methods. USSR Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 1964, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, P.K.; Thong, D.V.; Vinh, N.T. Improved inertial extragradient methods for solving pseudo-monotone variational inequalities. Optimization 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, D.V.; Hieu, D.V.; Rassias, T.M. Self adaptive inertial subgradient extragradient algorithms for solving pseudomonotone variational inequality problems. Optim. Lett. 2019, 14, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, D.V.; Vinh, N.T.; Cho, Y.J. A strong convergence theorem for tseng’s extragradient method for solving variational inequality problems. Optim. Lett. 2019, 14, 1157–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 408. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.-K. Another control condition in an iterative method for nonexpansive mappings. Bull. Aust. Math. Soc. 2002, 65, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maingé, P.-E. Strong convergence of projected subgradient methods for nonsmooth and nonstrictly convex minimization. Set-Valued Anal. 2008, 16, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, W. Nonlinear Functional Analysis; Yokohama Publishers: Yokohama, Japan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Harker, P.T.; Pang, J.-S. For the linear complementarity problem. Comput. Solut. Nonlinear Syst. Equ. 1990, 26, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.L.; Cho, Y.J.; Zhong, L.L.; Rassias, T.M. Inertial projection and contraction algorithms for variational inequalities. J. Glob. Optim. 2017, 70, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieu, D.V.; Anh, P.K.; Muu, L.D. Modified hybrid projection methods for finding common solutions to variational inequality problems. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2016, 66, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solodov, M.V.; Svaiter, B.F. A new projection method for variational inequality problems. SIAM J. Control Optim. 1999, 37, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, J. Solving pseudomonotone variational inequalities and pseudoconvex optimization problems using the projection neural network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2006, 17, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Shehu, Y.; Dong, Q.-L.; Jiang, D. Single projection method for pseudo-monotone variational inequality in Hilbert spaces. Optimization 2018, 68, 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).