Abstract

Rapid urban growth in South Indian coastal cities such as Chennai has intensified the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, with paved parking lots, walkways, and open spaces acting as major heat reservoirs. This study specifically compares conventional construction materials with natural and low-thermal-inertia alternatives to evaluate their relative ability to mitigate Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI) effects. Unlike previous studies that examine isolated materials or single seasons, this pilot provides a unified, multi-season comparison of nine urban surfaces, offering new evidence on their comparative cooling performance. To assess practical mitigation strategies, a field pilot was conducted using nine surface types commonly employed in the region—concrete, interlocking tiles, parking tiles, white cooling tiles, white-painted concrete, natural grass, synthetic turf, barren soil, and a novel 10% coconut-shell biochar concrete. The rationale of this comparison is to evaluate how conventional, reflective, vegetated, and low-thermal-inertia surfaces differ in their capacity to reduce surface heating, thereby identifying practical, material-based strategies for SUHI mitigation in tropical cities. Surface temperatures were measured at four times of day (pre-dawn, noon, sunset, night) across three months (winter, transition, summer). Results revealed sharp noon-time contrasts: synthetic turf and barren soil peaked above 45–70 °C in summer, while reflective coatings and natural grass remained 25–35 °C cooler. High thermal-mass materials such as concrete and interlocked tiles retained heat into the evening, whereas grass and reflective tiles cooled rapidly, lowering late-day and nocturnal heat loads. Biochar concrete performed thermally similarly to conventional concrete but offered co-benefits of ~10% cement reduction, carbon sequestration, and sustainable reuse of locally abundant coconut shell waste.

1. Introduction

Urbanization has significantly intensified the Urban Heat Island (UHI) phenomenon, whereby cities experience considerably higher temperatures than their rural surroundings due to extensive surface sealing, reduced vegetation cover, and increased anthropogenic heat emissions [1]. In addition to air temperature differences, urban regions also exhibit a pronounced Surface Urban Heat Island (SUHI) effect, where land surface temperatures rise sharply due to the thermal properties of built-up materials. Elevated surface and air temperatures in urban areas not only degrade outdoor thermal comfort but also escalate energy demand for cooling, degrade air quality, and amplify heat-related health risks, particularly in vulnerable populations [1,2]. Studies across tropical and subtropical cities highlight that paved and hard surfaces-including roads, parking lots, and walkways constitute approximately 30–45% of urban land cover, making them significant contributors to SUHI formation because of their high thermal mass and low reflectivity [1,3]. In Indian cities, UHI intensities of 4–6 °C have been reported in Delhi, Bengaluru, and Chennai, driven by widespread impervious cover and low vegetation fractions [4,5,6].

Cool pavements, vegetated substrates, and reflective surfaces have been widely investigated as urban heat mitigation strategies, primarily due to their ability to reduce net solar heat absorption and enhance thermal dissipation. High-albedo materials—whether through reflective coatings or inherently light-toned tiles—can significantly lower surface temperatures and improve pedestrian thermal comfort by reducing sensible heat flux [1,7,8]. Permeable and water-retentive pavements provide an additional cooling benefit via evaporative fluxes, while vegetated options, including natural grass, green roofs, and vertical greening systems, lower surface and near-surface air temperatures through latent heat removal [9,10,11]. Beyond direct thermal regulation, nature-based and bio-inspired interventions offer wider ecological and social co-benefits such as stormwater regulation, biodiversity enhancement, air pollutant filtration, and improvements in human well-being [12,13]. Despite these advantages, adoption may be constrained by higher upfront investment, irrigation requirements, or spatial limitations in dense tropical cities. Consequently, balancing technical performance with local socio-environmental feasibility remains a central challenge for UHI mitigation in rapidly urbanizing regions.

The efficacy of these mitigation strategies varies widely depending on local climatic conditions, diurnal and seasonal cycles, and urban morphology. Recent comprehensive reviews indicate that while various cool material technologies demonstrate measurable surface temperature reductions, factors such as material durability, maintenance requirements, cost-effectiveness, and secondary effects like glare or soiling substantially influence their long-term performance and adoption feasibility [14,15]. Specifically, reflective coatings and phase-change materials exhibit promising thermal benefits but can face challenges, including albedo degradation and pedestrian discomfort due to heightened glare [3,14]. Surface heating plays a critical role in determining local air temperatures through the exchange of sensible and radiative heat fluxes. Consequently, monitoring surface temperature dynamics is a fundamental approach to understanding the individual contributions of urban materials to UHI effects. Foundational research by Oke [2] established that elevated surface temperatures increase sensible heat flux, raising mean radiant temperature and consequently near-surface air temperatures, which intensifies heat stress on urban residents. Numerous subsequent studies corroborate these findings, emphasizing the cooling benefits of vegetated and reflective surfaces in mitigating local thermal loads [1,8,16,17].

Recent evidence further highlights the strong cooling and energy benefits of low-thermal-inertia and nature-based solutions. Systematic evaluations show that green roofs can reduce rooftop surface temperatures by up to 86%, lower outdoor ambient temperatures by as much as 7.4 °C, and improve indoor thermal comfort by 0.2–3.7 °C, leading to 10–35% annual energy savings in warm climates [18]. Multi-layer green roofs and other advanced configurations further reduce external surface temperatures by 25–40 °C, underscoring their high passive-cooling potential. Comparative multi-criteria assessments also demonstrate that vegetated and hybrid PV-green roofs consistently outperform cool roofs across most performance objectives, reducing heat flux by ~82% and stormwater runoff by ~90% while providing broader ecological benefits [19]. These quantitative insights substantiate the relevance of evaluating natural and low-thermal-inertia materials alongside conventional surfaces in tropical cities.

In recent years, hybrid materials combining the cooling potential of reflective or vegetated surfaces with sustainable low-carbon design principles have attracted growing interest. Biochar, a carbon-rich material derived from the pyrolysis of biomass, has emerged as an innovative supplementary cementitious material. Research indicates that incorporating small percentages (1–2% by weight) of biochar into cementitious mixtures can improve thermal insulation and reduce heat storage capacity without compromising mechanical strength, thereby contributing to both thermal and carbon mitigation objectives [20]. Such innovations align closely with circular economy principles and have substantial relevance for tropical urban construction, where minimizing embodied emissions and ambient heating are priorities [21].

Although a growing body of laboratory and simulation studies has evaluated the thermal performance of different urban materials, comprehensive field-based comparisons that integrate both seasonal and diurnal variability remain limited, particularly for tropical settings. Existing studies often focus on single technologies or short observation windows, leaving gaps in understanding how diverse surface types behave under uniform field conditions across multiple times of day and seasons [22,23]. Our pilot contributes to addressing this gap by systematically comparing nine common urban materials—including conventional pavements, reflective coatings, vegetated substrates, and a coconut-shell biochar-amended concrete—under the same environmental conditions. The specific contribution of this work lies in generating a multi-material, multi-time-of-day dataset for a tropical coastal site, coupled with life-cycle cost considerations and an exploratory assessment of biochar concrete as a sustainability-oriented hybrid option.

Adding complexity to urban heat dynamics is the often-overlooked role of parked vehicles themselves. Recent studies also highlight the overlooked role of parked vehicles, which alter surface albedo and radiative balance. Vehicle colour modulates local air temperatures, with darker cars intensifying heat loads more than lighter ones [24]. These findings argue for holistic urban heat mitigation approaches that account not only for fixed urban fabrics such as pavements and buildings but also mobile elements like vehicles.

This pilot study investigates the seasonal and diurnal surface temperature dynamics of nine commonly encountered urban materials—including conventional (concrete, interlocking tiles, parking tiles), reflective (white cooling tiles, white paint), vegetated (natural grass, synthetic turf), and hybrid materials (10% coconut-shell biochar concrete). By evaluating these surfaces under uniform field conditions across winter, transition, and summer periods, the study aims to: (i) quantify differences in heating and cooling behaviour, and (ii) assess their relative suitability as cost-effective SUHI mitigation options. The scope is limited to plot-scale surface temperature comparisons, with the goal of generating clear, actionable evidence to support material selection for sector-specific urban cooling strategies in tropical cities.

2. Materials and Methods

To identify representative surface materials for urban thermal assessment, reconnaissance surveys were carried out across different functional zones of Chennai city, focusing on parking areas, walkways, and open spaces. This survey highlighted the most frequently encountered surface types in use for pedestrian and vehicular spaces. Based on this, eight dominant categories were selected for detailed monitoring: (1) natural grass, (2) synthetic turf (synthetic grass), (3) white tile (cooling tile), (4) white paint, (5) conventional concrete, (6) parking tile, (7) interlocked tiles, and (8) barren soil.

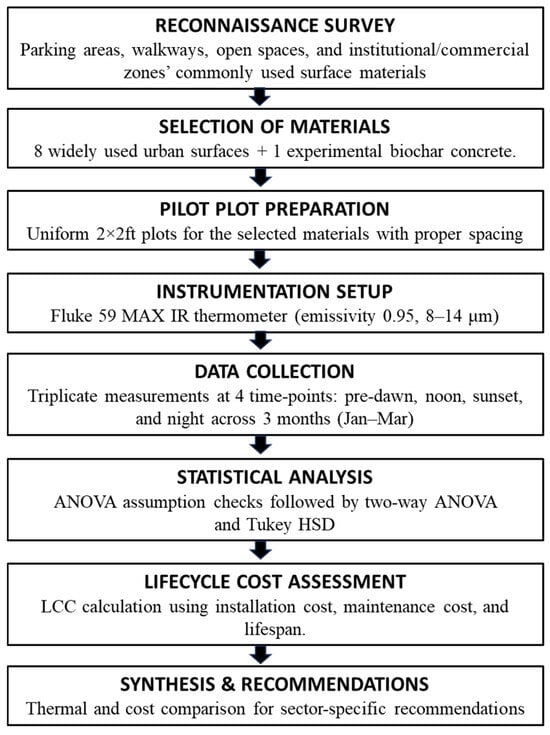

In addition to these widely used materials, an experimental category was incorporated in the form of biochar-amended concrete (10% substitution), developed as a pilot intervention to evaluate the potential of sustainable construction alternatives in reducing surface heating. Together, these nine categories provided a comprehensive cross-section of surfaces typically present in tropical urban environments, enabling comparison of both conventional practices and innovative materials. The barren soil was considered the control. The rationale for the selection of these eight dominant categories is grounded in their prevalence, climatic relevance, and functional roles within Chennai’s urban landscape. These surfaces represent the most used materials across mobility corridors (concrete, interlocking and parking tiles), reflective and heat-mitigating treatments (white paint, cooling tiles), and vegetated or semi-natural covers (natural grass, synthetic turf), along with exposed soil frequently found in vacant plots and unpaved open areas. Their widespread use, combined with their contrasting thermal properties, makes them appropriate benchmark materials for assessing surface SUHI behaviour under tropical climatic conditions. The overall research workflow, including material selection and analytical steps, is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the Study Methodology.

2.1. Biochar Concrete Preparation

This study explores the potential of coconut shell-derived biochar as a partial replacement for cement in concrete, with the primary objective of reducing cement dependency and thereby minimizing the indirect use of fossil fuels associated with cement production—a major contributor to rising global temperatures and climate change.

Three concrete mixes were prepared by replacing cement with biochar at 5%, 10%, and 15% by weight. A nominal mix ratio of 1:2:4 (cement: sand: coarse aggregate, by volume) was adopted, which is widely accepted in general construction practices for achieving workable and structurally sound concrete. In each mix, the cement portion was partially substituted with biochar while maintaining the overall volumetric balance.

Concrete cubes of 15 cm × 15 cm × 15 cm were cast for each mix. After 24 h of initial setting, the specimens were placed in water for 28 days of curing to ensure proper hydration. Post-curing, the compressive strength of the samples was tested using a Universal Testing Machine (UTM). This step was conducted to identify which biochar mix ratio yields strength comparable to conventional concrete, so that the most viable proportion could be selected for further study.

2.2. Pilot Study Preparation and Experimental Setup

To evaluate the thermal behaviour of commonly used surface materials in urban open spaces, a pilot study was conducted. An open land parcel without any overhead shading was selected and cleared of vegetation to allow uninterrupted exposure to solar radiation throughout the day. A total of nine surface types were prepared for comparison: concrete, interlocked tiles, parking tiles, white cooling tiles, white paint, synthetic turf, natural grass, barren soil (as a control), and biochar-mixed concrete.

Each material was installed in plots of uniform size (2 × 2 ft; 4 sq. ft area), with adequate spacing maintained between plots to avoid mutual thermal interaction or lateral heat transfer (Figure 2). The barren soil plot served as a reference control to benchmark material-induced variations. Construction of the experimental units followed standard installation procedures, with surfaces such as tiles and grass laid over compacted soil bases, while concrete and biochar-mixed concrete were cast in situ. The biochar concrete was prepared by replacing 10% of the cement content with coconut shell-derived biochar, representing a sustainable material innovation.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup of eight surface materials installed in 2 × 2 ft plots with spacing to avoid thermal interaction. (a) Concrete (b) Interlocked Tiles (c) Parking Tiles (d) White Cooling Tile (e) Synthetic Turf (f) Natural Grass (g) White Paint (h) Biochar Mix Concrete.

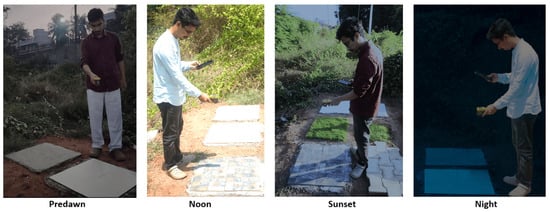

Following installation, the pilot setup was stabilized and maintained for the duration of the study period. Surface temperature measurements were subsequently carried out under consistent protocols (described in the instrumentation section), capturing diurnal and seasonal dynamics of each material. Field measurement activities, including daytime and nighttime observations, are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Field measurements of surface temperature across diurnal cycles using a Fluke 59 MAX infrared thermometer.

2.3. Data Collection

Surface temperature was measured using a Fluke 59 MAX handheld infrared thermometer (Fluke Corp., Everett, WA, USA) with a spectral range of 8–14 μm and a distance-to-spot (D:S) ratio of 10:1. The instrument has a fixed emissivity setting of 0.95, suitable for most organic and matte construction surfaces such as paints, concrete, soil, and vegetation. Measurements were taken by holding the instrument perpendicular (≤15° angle) to the surface, ensuring that the measured spot fully covered the target area. Although emissivity can vary across highly reflective or glossy surfaces, using a uniform setting ensured internal consistency across all material comparisons in this pilot study.

Each surface type (concrete, tiles, grass, synthetic turf, and biochar-mixed concrete) was measured in triplicate at four distinct times of day—pre-dawn, noon, sunset, and night—across three months (January–March 2025). These intervals were selected to capture the diurnal extremes and transitional phases of surface thermal behaviour. Pre-dawn (05:00–06:00 h) represents the coldest period of the day, when surfaces have cooled continuously through nocturnal radiative heat loss, thus providing information on the minimum temperatures and the capacity of materials to retain heat overnight. Noon (≈13:00 h) was chosen shortly after solar zenith, allowing sufficient time for maximum solar loading; this period reflects peak heat absorption and highlights the thermal response of materials under extreme exposure. Sunset (17:30–18:30 h) coincides with the onset of surface cooling as solar radiation declines, offering insights into how quickly different materials dissipate stored heat. Finally, nighttime (22:00–23:00 h) measurements capture conditions when ambient temperatures have dropped further, and surfaces have been releasing heat for several hours, enabling evaluation of thermal emissivity and residual heat retention. Together, these time points provide a comprehensive profile of material-specific diurnal thermal dynamics critical for assessing their role in microclimatic regulation. Since surface heating strongly influences local air temperature through convective and radiative fluxes, monitoring surface temperatures provides critical insights into material contributions to UHI effects.

This study focused on surface temperature dynamics as a proxy for UHI-related heating. Although near-surface air temperature, humidity, and heat flux were not directly measured, integrating these parameters in future work would provide stronger links to human thermal comfort and energy balance.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For each season, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with Material and Time-of-day as fixed factors. Before running ANOVA, the data were checked for normality (Shapiro–Wilk), homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test), and independence based on sampling design; all assumptions were satisfied (p > 0.05). Where ANOVA indicated significance (α = 0.05), pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test; results are reported as mean ± SD and compact letter groupings to indicate significant differences.

2.5. Evaluating Lifecycle Performance and Economic Viability

To evaluate the long-term cost-effectiveness of surface materials in the context of SUHI mitigation, A standard life-cycle cost (LCC) approach was applied, following the formula below-

Where:

Installed cost ($/sqft) = one-time material + labour cost required for initial installation.

Design life (years) = average functional lifespan of each material based on standard construction practice (e.g., tiles: 15 yrs, concrete: 20 yrs, turf: 8 yrs, cooling paint: 5 yrs).

Maintenance cost ($/sqft/yr) = recurring annual expenditure required for upkeep (cleaning, repainting, watering for grass, etc.).

Units:

All costs are expressed in $/sqft for installation and $/sqft/year for maintenance and annualised values.

Values reflect market rates from 2023–2025.

Assumptions:

No inflation or discounting factor was applied due to the short analysis horizon.

Disposal and end-of-life costs were excluded as these vary widely across municipalities.

Lifespans were kept constant across seasons because the study focuses on relative cost–performance comparison.

This method aligns with the principles outlined in the ISO 15686-5:2017 standard [25], which provides guidelines for performing life-cycle costing analyses of buildings and constructed assets. The standard emphasizes evaluating all relevant costs—including acquisition, operation, maintenance, and disposal—over a defined analysis period, thereby enabling informed decision-making across alternative material options [25].

3. Results

3.1. Compressive Strength of Coconut Shell Biochar Concrete Mixes

The 28-day compressive strength of conventional concrete and coconut shell biochar (CSB) concrete mixes is summarized in Table 1. The control mix (M0: 0% CSB) achieved 33.5 N/mm2, consistent with the expected strength for nominal 1:2:4 concrete. Incorporating 5% CSB (M1) resulted in 32.6 N/mm2, a marginal reduction of ~2.5% compared to the control. At 10% CSB replacement (M2), compressive strength decreased slightly to 31.9 N/mm2 (~95% of control). However, a further increase to 15% CSB (M3) reduced strength more significantly to 30.2 N/mm2 (~10% lower).

Table 1.

Compressive Strength of Biochar Concrete Mixes.

Although both 10% and 15% mixes showed reduced strength relative to the control, the decline at 15% (−9.87%) was more than double that at 10% (−4.76%). Therefore, 10% was selected as the most appropriate upper limit for further comparison and was included in the study alongside the other eight materials.

3.2. Material—Wise Surface Temperature Differences Relative to Barren Soil

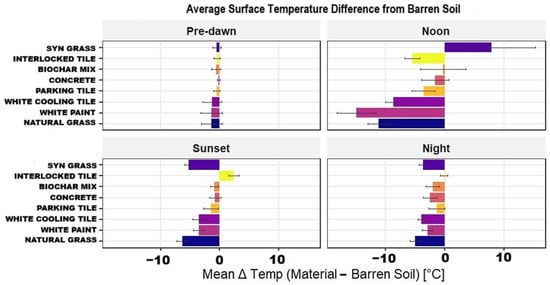

Surface temperature contrasts between different materials and barren soil showed clear diurnal variability (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Material—wise Surface Temperature Deviations from Barren Soil.

During predawn, temperature differences were minimal as all surfaces cooled toward equilibrium after nocturnal radiative loss. Reflective and vegetated surfaces such as white paint, cooling tiles, and natural grass remained slightly cooler than barren soil, while synthetic turf and interlocked tiles showed little deviation.

At noon, divergences were most pronounced. White paint and natural grass were approximately 12–15 °C cooler than barren soil at noon, and cooling tiles reduced heating by approximately 8–10 °C. Materials of intermediate reflectance, like biochar mix, concrete, and parking tiles, showed minor reductions of 1–2 °C. Synthetic turf reached 8–10 °C warmer, and interlocked tiles also remained slightly above barren soil, indicating strong heat absorption.

During sunset, temperature contrasts persisted. White paint and natural grass stayed 3–5 °C cooler, and cooling tiles maintained 2–3 °C cooling. Concrete and biochar mix were similar to barren soil, whereas interlocked tiles remained 3–4 °C warmer, showing delayed heat release. Synthetic turf, however, exhibited a cooling trend comparable to vegetated and reflective surfaces.

At night, differences narrowed but persisted: white paint and natural grass remained 2–3 °C cooler, cooling tiles and biochar mix showed ~1–2 °C advantage, while synthetic turf and interlocked tiles stayed slightly warmer than barren soil.

3.3. Seasonal and Diurnal Variations in Surface Temperature Across Urban Materials

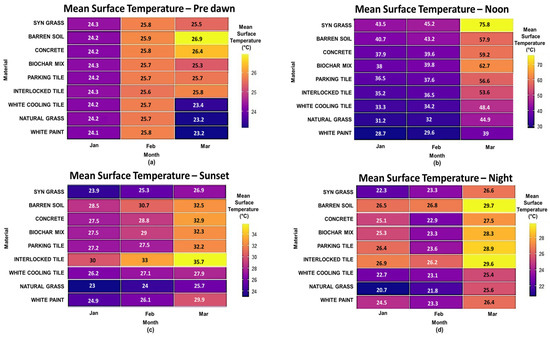

The diurnal and seasonal surface temperature patterns of the nine studied materials are presented in Figure 5, averaged across winter (January), transition (February), and summer (March) seasons. Additional statistical details for each material and time period are available in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1–S4).

Figure 5.

Seasonal and Temporal Surface Temperature Patterns of Urban Materials: (a) Pre-dawn, (b) Noon, (c) Sunset, and (d) Night.

- (a)

- Pre-dawn

At pre-dawn, barren soil registered the highest surface temperatures (26.9 °C in March), reflecting its limited evaporative potential and high thermal inertia. Concrete (26.4 °C) and interlocked tiles (25.8 °C) followed closely, within ~2–4% cooler than barren soil, also showing delayed night-time cooling due to heat storage. In contrast, natural grass and white paint remained coolest (~23.2 °C), about 13–14% lower than barren soil, as vegetation supports evaporative cooling and reflective coatings reduce heat absorption. White cooling tiles (23.4 °C) and biochar mix (25.3 °C) also moderated retention by 6–13%.

- (b)

- Noon

At midday, barren soil peaked at 57.9 °C in March, acting as a thermal benchmark due to its dark, absorptive surface. Synthetic turf exhibited extreme heating (75.8 °C), ~31% hotter than barren soil, likely from its low albedo and poor moisture content. Biochar mix (62.7 °C) was ~8% warmer than barren soil, reflecting partial heat retention in its dark surface. Conversely, concrete (59.2 °C) and parking tiles (56.6 °C) were similar to or slightly cooler than barren soil (~2–3% lower). Reflective and vegetated surfaces showed strong moderation: white cooling tiles (48.4 °C) and natural grass (44.9 °C) reduced noon heat by 16–22% compared to barren soil, while white paint (39.0 °C) was ~33% cooler, owing to its high albedo.

- (c)

- Sunset

By sunset, barren soil retained significant heat (32.5 °C in March), reflecting its slower release of absorbed radiation. Interlocked tiles showed even higher persistence (35.7 °C), ~10% hotter than barren soil, due to dense structure and low reflectivity. Concrete (32.9 °C) was nearly equivalent to barren soil, while biochar mix (32.3 °C) and parking tiles (32.2 °C) were slightly cooler (~1–2%). Cooling-oriented materials performed better: white paint (29.9 °C) and white cooling tiles (27.9 °C) reduced evening heat by 8–14% relative to barren soil. Natural grass (25.7 °C) remained coolest, ~21% lower than barren soil, as moisture and evapotranspiration supported rapid evening cooling. Synthetic turf (26.9 °C) showed intermediate reduction (~17% cooler), though its plastic fibres retained some heat.

- (d)

- Night

At night, barren soil again recorded the highest retention (29.7 °C in March), illustrating the delayed release of stored daytime heat. Interlocked tiles were nearly identical (29.6 °C), while parking tiles (28.9 °C) and biochar mix (28.3 °C) were slightly cooler (by ~3–5%). Concrete (27.5 °C) and synthetic turf (26.6 °C) showed reductions of ~7–11% compared to barren soil. White paint (26.4 °C), white cooling tiles (25.4 °C), and natural grass (25.6 °C) offered the strongest cooling, lowering night temperatures by 14–15% relative to barren soil.

3.4. Thermal Performance and Sustainability Potential of Biochar Concrete

The results show that the surface temperature of biochar-amended concrete (10% substitution by volume) remains nearly equivalent to conventional concrete across all time periods (predawn, noon, sunset, and night) during the January–March observation window. Although its direct thermal regulation benefit appears limited, biochar-modified concrete offers several important environmental co-benefits.

A key advantage lies in its ability to reduce Portland cement consumption, one of the most carbon-intensive materials globally. Cement production accounts for nearly 7–8% of global CO2 emissions, mainly from limestone calcination and fossil fuel use [26]. Even a modest 10% substitution can therefore contribute to measurable emission reductions and energy savings.

Using coconut shell-derived biochar, an abundant agro-waste in southern India, also represents a sustainable waste valorisation strategy. Converting this residue into biochar for concrete not only diverts waste from open burning or landfills but also supports a circular economy [27]. Scientifically, biochar serves as a stable carbon sink, capable of locking atmospheric carbon for centuries [28]. When incorporated into concrete, it provides long-term carbon storage within the built environment, contributing to climate change mitigation and urban sustainability. Moreover, biochar-modified composites can improve workability, durability, and resistance to cracking [29].

Thus, while the thermal behaviour of biochar concrete closely resembles that of conventional concrete, its indirect sustainability benefits—including cement substitution, carbon sequestration, and waste reuse—make it a promising climate-smart construction material (Table 2). It should therefore be viewed as a co-benefit intervention supporting UHI mitigation, rather than a primary cooling strategy.

Table 2.

Comparison Table: Conventional Concrete vs. 10% Biochar-Concrete.

4. Discussion

4.1. Compressive Strength of Coconut Shell Biochar Concrete Mixes

The slight reduction in strength with increasing CSB reflects partial cement dilution and limited pozzolanic reactivity of biochar. At ≤5%, strength loss was negligible, likely due to filler effects that enhance matrix packing and hydration.

Beyond 10%, strength decreased more noticeably, consistent with Adajar [30] and Vivek [31], as reduced cement content limits Calcium silicate hydrates(C-S-H) formation and biochar’s high surface area raises water demand.

Overall, a 10% CSB replacement offers the best balance between mechanical integrity and sustainability, justifying its selection for further experimentation.

4.2. Material—Wise Surface Temperature Differences Relative to Barren Soil

The diurnal variation clearly demonstrates that material properties strongly govern heat absorption and release relative to barren soil. High-albedo and vegetated surfaces consistently maintained lower temperatures due to enhanced solar reflectivity and evaporative cooling, proving their efficiency in minimizing surface heat load. Biochar-mixed and conventional concretes were slightly cooler than barren soil during night hours, suggesting a moderate reduction in heat retention compared to the soil baseline. In contrast, interlocked tiles exhibited persistent evening and nighttime warming, reflecting their low albedo and high thermal inertia, which delay heat release. Although synthetic turf showed strong heating at noon, its post-sunset cooling indicates rapid convective heat loss. Overall, barren soil represented an intermediate thermal baseline, with deviations highlighting the role of surface reflectivity, porosity, and moisture content in shaping diurnal thermal behaviour.

4.3. Discussion—Seasonal and Diurnal Variations in Surface Temperature Across Urban Materials

Across the diurnal cycle, clear seasonal amplification of surface heating was observed from January to March, though its expression varied with material properties. During the predawn hours, all surfaces exhibited relatively small but consistent warming of ~2–3 °C relative to barren soil, reflecting uniform night-time heat accumulation. This pattern supports earlier findings that impervious, low-moisture materials display weaker nocturnal cooling capacity [1,2]. At midday, the seasonal increase was most pronounced, with barren soil itself warming by ~17 °C and darker impervious materials showing even greater amplification. These results underscore albedo and surface moisture as dominant controls on midday heating, whereby high-absorptivity pavements intensify sensible heat flux, while reflective coatings and vegetated covers mitigate extremes [32]. By sunset, delayed release of stored solar energy was evident: barren soil and concrete warmed by ~4–5 °C across the season, while interlocked tiles increased by ~6–8 °C, confirming their stronger heat retention. This persistence extended into nighttime conditions, where March surfaces were on average ~3–4 °C warmer than in January. Dense, low-albedo pavements such as barren soil and interlocked tiles consistently delayed nocturnal cooling, prolonging heat release into the evening and thereby exacerbating residual UHI intensity [33].

To strengthen interpretation beyond descriptive patterns, we compared the materials based on underlying surface energy-balance mechanisms. High-albedo, low-thermal-inertia surfaces such as white paint and cooling tiles consistently showed strong suppression of daytime heating and faster evening cooling, driven by reduced shortwave absorption and limited heat storage. Vegetated surfaces—particularly natural grass—remained the coolest across all periods due to evapotranspiration, high moisture availability, and high emissivity, which enhances longwave radiative heat loss. In contrast, dense impervious materials such as concrete and interlocked tiles exhibited pronounced thermal inertia, absorbing large midday heat loads and releasing them slowly into the evening, consistent with classical UHI theory described by Oke [2]. Synthetic turf showed extreme midday peaks due to its dark colour, low moisture, and polymer composition, but cooled quickly after sunset due to low volumetric heat capacity. Across seasons, all materials intensified in temperature from winter → transition → summer, but the magnitude varied systematically with material properties rather than ambient conditions alone. These mechanistic differences clarify why reflective and vegetated surfaces provide strong SUHI mitigation potential, while thermally massive pavements prolong late-day and nocturnal heat stress.

4.4. Cost—Performance Assessment of Urban Surface Materials

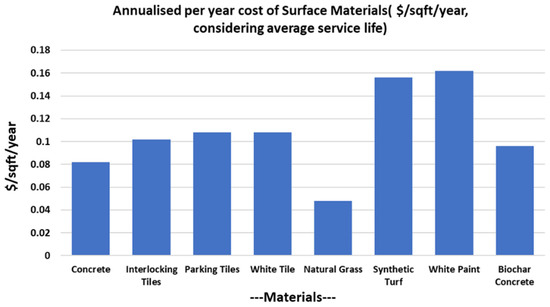

The derived annualized cost values presented in Table 3 and visualized in Figure 6 serve as a foundation for sector-wise recommendations, balancing financial feasibility with environmental performance. Cost estimates are based on Indian market data from 2023 to 2025, incorporating prevailing rates for labour, material, and upkeep. Service life assumptions used in the analysis include: Concrete and Biochar Concrete—20 years; Tiles and Pavers—15 years; Synthetic turf and Cooling White Paint—5 years; and Natural Grass—considered continuous due to its regenerative nature. These values, along with the standard life-cycle cost analysis, enabled a consistent comparison across materials, supporting sector-specific recommendations for UHI mitigation.

Table 3.

Installation, Maintenance & Annualised Cost per sqft.

Figure 6.

Annualised Per-Year Cost of Surface Materials.

4.5. Sector—Wise Recommendations

Based on the comparative analysis of installation cost, service life, and thermal performance of different surface materials, sector-specific strategies are proposed that integrate nature-based, nature supportive and material-based cooling interventions for SUHI mitigation. These recommendations consider the economic feasibility, land-use function, and potential for large-scale implementation within different urban sectors.

- (i)

- Factories & Industrial Zones

Industrial estates in and around Chennai are presently dominated by vast expanses of barren soil and dark concrete or asphalt surfaces, particularly across cargo yards, loading bays, and wide circulation roads. These surfaces act as major heat reservoirs, with our observations showing peak noon temperatures often exceeding 60 °C. Their high thermal mass, low reflectivity, and poor permeability contribute not only to surface heat buildup but also to increased worker heat stress and stormwater runoff during monsoon episodes.

To mitigate these impacts, durable and low-maintenance alternatives are recommended, prioritising materials that can withstand heavy vehicular loads while moderating surface heating. For large parking courts, cargo yards, and loading zones, interlocking pavers or parking tiles represent a practical upgrade. In our measurements, these surfaces remained ~2–4 °C cooler at noon compared to conventional dark concrete and asphalt, while their permeable joints facilitated effective rainwater percolation. Though their initial costs are moderate, their thermal benefits and long service life make them a viable first-line strategy for industrial heat resilience.

At pedestrian-access nodes such as entry gates, checkpoints, and rest shelters, applying high-albedo white cooling tiles or reflective paint, complemented by shading structures, produced surface reductions of ~8–14 °C at noon in our trials. This substantially lowers mean radiant temperature (MRT) exposure and improves occupational thermal comfort [16], aligning safety goals with worker welfare.

For newly constructed hardstands and driveways, biochar-enriched concrete (with 10% cement replacement) offers thermal behaviour nearly identical to standard concrete (Δ ≈ 0–2 °C) while reducing embodied carbon through cement substitution and biogenic carbon sequestration [28,29]. This makes it a sustainable alternative for long-term infrastructure expansion in industrial zones.

Conversely, continued reliance on unshaded concrete and asphalt should be avoided, as these consistently record the highest daytime surface temperatures and exacerbate UHI intensity. Prioritising reflective, permeable, and carbon-smart materials will therefore be critical to advancing both environmental performance and corporate sustainability in Chennai’s industrial sector.

- (ii)

- IT Parks & Technology Campuses

As Chennai serves as a major hub for IT and technology industries, its corporate campuses are uniquely positioned to adopt high-impact, visibly green infrastructure to mitigate urban heat while reinforcing their environmental branding. These large sites often contain expansive open plazas, shaded break-out zones, internal walkways, and extensive parking courts—making material choice critical for thermal comfort and sustainability reporting.

For central open spaces and employee congregation areas, installing natural grass lawns interspersed with shaded seating structures can reduce peak surface temperatures by ~10–12 °C at noon and ~4–5 °C at night compared to dark hardscapes. Such installations must be supported by greywater-based irrigation systems to overcome Chennai’s water stress, turning wastewater reuse into a visible climate-positive practice that aligns with corporate ESG targets.

In parking areas, replacing conventional concrete or asphalt with interlocking tiles or parking tiles—especially when combined with modular shading canopies—offered ~5–7 °C lower noon surface temperatures in our study and allowed rainwater infiltration, reducing runoff during Chennai’s intense monsoon spells. This dual benefit of cooling and water-sensitive design makes them highly suited to large vehicular courts typical of IT campuses.

For internal pedestrian walkways and approach corridors, high-albedo white cooling tiles or white-painted concrete surfaces provided ~8–14 °C lower midday temperatures in our dataset, giving immediate heat-stress relief to foot traffic. Although their installation cost is moderate, these materials signal visible greening efforts while requiring only routine cleaning to maintain their reflectivity.

Synthetic turf and bare dark concrete/asphalt should be avoided as primary surfacing in IT campuses. Synthetic turf heated rapidly under peak solar exposure and remained ~5–7 °C warmer at night than natural or permeable alternatives, while offering negligible evaporative cooling. Bare dark pavements showed >60 °C noon surface temperatures, substantially worsening local heat stress and undermining green branding. Their use contradicts the sustainability image that IT parks seek to project.

- (iii)

- Shopping Malls & Commercial Complexes

Commercial complexes should focus measures where pedestrian exposure and dwell times are highest, such as entry plazas, drop-offs, and shaded waiting zones. Based on our thermal observations, the most effective strategy for these micro zones is the selective use of high-albedo cooling materials, especially white cooling tiles, which showed the largest surface temperature reductions (~8–14 °C at noon) and provide immediate improvement in MRT for visitors and staff.

For extensive outdoor parking areas, interlocking pavers are recommended as the primary base material (observed reductions ~2–4 °C at noon) because they heat less than dark concrete or asphalt, require minimal maintenance, and support long-term durability. Where a more climate-conscious but structurally robust option is desired, biochar-mixed concrete can be adopted as an alternative to standard concrete: while its thermal behaviour was nearly identical to conventional concrete (Δ ≈ 0–2 °C), it offers substantial indirect benefits by lowering cement demand and embodied CO2 emissions.

For malls, the recommended hierarchy of surface materials balances thermal mitigation, durability, and user comfort. White or cooling tiles are best suited for high-footfall pedestrian areas, where they reduce surface heating and enhance comfort, while interlocking pavers are more appropriate for parking zones due to their load-bearing strength and ease of upkeep. Where cost constraints exist, interlocking pavers may be applied more extensively, with shaded patches of white cooling tiles at entrances to improve the visitor experience. For driveways and heavier load-bearing sections, biochar concrete provides structural strength and, when paired with white cooling tiles in key pedestrian areas, offers a practical compromise between durability and heat reduction.

In contrast, synthetic turf is not advised for large exposed zones because it exhibits surface temperatures similar to or slightly higher than concrete under peak sun and offers no evaporative cooling. Barren soil and dark, unshaded concrete should also be avoided, as they showed the highest daytime heating and poor thermal comfort. Similarly, whole-lot reflective paint coatings on large surfaces are discouraged, as although they initially lower surface temperature, they require frequent reapplication and create glare-related safety hazards in parking lots.

- (iv)

- Residential Neighbourhoods

In residential contexts, SUHI mitigation strategies must balance affordability, durability, and water sensitivity. While our experimental results showed that natural grass provided the greatest cooling effect (~10–12 °C lower at noon, ~4 °C lower at night), its high irrigation demand limits its practicality in water-stressed regions like Chennai. Therefore, our recommendations are presented in order of cost-effectiveness and feasibility for long-term residential application, rather than strictly by thermal efficiency.

Interlocking pavers with small vegetated pockets represent the most affordable and durable choice. They showed ~2–4 °C lower surface temperatures at noon compared to conventional hardscapes, while maintaining low upkeep costs (≈8–8.5/sqft/yr). Their modular design supports easy replacement of damaged units and reduces stormwater runoff, making them well-suited for driveways, internal walkways, and small parking bays.

Light-coloured, high-albedo tiles are a moderately priced option that recorded ~4–8 °C cooler surfaces at noon. Their application in courtyard walkways and house-front paths can substantially reduce radiant heat exposure for pedestrians and improve outdoor thermal comfort.

Natural grass patches in pocket gardens or common areas, although highly effective thermally, should only be adopted where sustainable irrigation (e.g., drip or greywater systems) is available. This option is best reserved for shaded or community-managed spaces where long-term water use can be justified.

Synthetic turf, while initially appearing cooler than bare soil, was observed to heat rapidly under peak solar exposure and remained approximately 5–7 °C warmer at night. It also requires periodic water spraying and cleaning to prevent excessive heat buildup, making it unsuitable in water-constrained residential settings. Similarly, dark pavements or bare asphalt surfaces consistently exhibited the highest surface temperatures (>55–60 °C at noon) and should be avoided, as they intensify localized heat accumulation and compromise thermal comfort.

4.6. Limitations and Future Scope

This study was conducted on small experimental plots (2 × 2 ft) at a single pilot site over a three-month period (January–March). Although the design allowed controlled and repeated field measurements, meteorological variables such as global radiation, wind speed, cloud cover, and near-surface air temperature were not directly measured at the site. Hourly meteorological values from the nearest IMD station were referenced only for general background conditions, which limits our ability to fully attribute intra- and inter-seasonal differences to atmospheric drivers.

This study focuses exclusively on SUHI behaviour, using surface temperature as the primary metric. Since air temperature, mean radiant temperature, and thermal comfort indicators were not measured, the findings represent surface-level thermal contrasts rather than broader atmospheric or human-comfort responses. The IR thermometer used in the study operated at a fixed emissivity of 0.95, which is suitable for most matte urban materials. Reflective or glossy surfaces may have lower emissivity, potentially causing slight temperature underestimation. Because all materials were measured under identical settings, relative comparisons remain reliable. However, future work should incorporate emissivity-adjustable sensors or laboratory-measured emissivity values for improved accuracy. For the biochar-amended concrete, this pilot phase focused only on compressive strength. Other durability-related properties (e.g., creep, shrinkage, long-term chemical stability) were beyond the present scope. These aspects will be incorporated in future work to provide a more complete structural assessment.

While the results provide reliable pilot-scale evidence under controlled field conditions, future work can extend observations across monsoon and post-monsoon seasons and include additional sites to capture broader urban variability. Scaling to larger plot sizes and incorporating limited microclimate measurements (e.g., radiation or wind) would further strengthen comparisons and support model-based extrapolation for real-world applications.

5. Conclusions

This study provides one of the first empirical assessments of seasonal and diurnal surface temperature dynamics of conventional, reflective, vegetated, and biochar-modified materials under tropical field conditions. The results demonstrate that material choice exerts a decisive influence on surface thermal regimes: high-albedo coatings (white paint, cooling tiles) and vegetated covers (natural grass) consistently reduced midday heating by up to 48% and accelerated nocturnal cooling by ~14% compared to barren soil, whereas dense pavements and synthetic turf exacerbated both daytime heat loads and night-time heat retention.

For urban planners and designers, these findings underscore that surface materials should be selected not in isolation but in alignment with diurnal cooling needs. Reflective pavements and vegetated corridors are particularly effective in mitigating extreme midday heat stress, while materials with lower thermal mass and enhanced convective exchange support faster evening and night-time cooling. Integrating such mixed-material strategies—combining reflective finishes in pedestrian areas with permeable pavers and shaded vegetation in open spaces—can optimize 24 h thermal comfort and lower cooling-energy demand in parking, residential, and commercial environments.

The cost-performance analysis further highlights the need for sector-specific deployment. High-investment sectors such as industrial estates and IT campuses are well-positioned to adopt advanced reflective and biochar-based materials that deliver substantial reductions in surface heating (up to 12–14 °C at noon) while advancing sustainability branding. In contrast, residential neighbourhoods and commercial complexes can prioritize cost-effective interventions such as interlocking pavers, white cooling tiles, and localized grass patches, offering meaningful reductions of 2–12 °C while remaining economically viable.

Although biochar-amended concrete showed thermal performance comparable to conventional concrete, its broader sustainability value is significant. By partially substituting cement with coconut shell biochar (up to 10% replacement), this material offers lifecycle benefits including reduced clinker demand, valorisation of agro-waste, and long-term carbon sequestration. These co-benefits position biochar concrete as a promising hybrid innovation, bridging structural durability with climate-smart design.

Overall, this study reinforces the principle that targeted, context-sensitive material choices are central to sustainable urban heat mitigation. By aligning thermal behaviour, economic feasibility, and environmental co-benefits, cities can deploy layered material strategies that reduce urban heat island intensity, improve outdoor comfort, and contribute to broader climate resilience agendas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122412/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.A., D.L.R. and S.J.; methodology, S.Z.A.; software, S.Z.A.; validation, S.Z.A., D.L.R. and S.J.; formal analysis, S.Z.A.; investigation, S.Z.A.; resources, S.J.; data curation, S.Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.A. and S.J.; writing—review and editing, D.L.R. and S.J.; visualization, S.Z.A.; supervision, S.J. and D.L.R.; project administration, S.J.; funding acquisition, D.L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge University of Catania for providing institutional support and Pondicherry University for permitting the use of campus space for conducting this study. The authors also extend their sincere thanks to Nigamananda Mohanty, Sankar Thampuran M.V., and Sovasish Karna for their valuable assistance during the preparation and setup of the field experiment. Part of this work has been done under the Project “Nature for sustainable cities: planning cost-effective and just solutions for urban issues”, PRIN 2022, funded by European Union, Next Generation EU.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| SUHI | Surface Urban Heat Island |

| UTM | Universal Testing Machine |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LCC | Life-Cycle Cost |

| CSB | Coconut Shell Biochar |

References

- Santamouris, M. Using cool pavements as a mitigation strategy to fight urban heat island—A review of the actual developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. Boundary Layer Climates, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Ren, Z.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W.; Bao, G. Efficient cooling of cities at global scale using urban green space to mitigate urban heat island effects in different climatic regions. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, H.; Singh, J.S. Green infrastructure of cities: An overview. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 2020, 86, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Anjali, A.; Singh, V.K.; Semwal, V.B. Mapping urban heat islands in Pune, India: Ecological impacts and environmental challenges. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 16, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Debele, S.E.; Khalili, S.; Halios, C.H.; Sahani, J.; Aghamohammadi, N.; de Fatima Andrade, M.; Athanassiadou, M.; Bhui, K.; Calvillo, N.; et al. Urban heat mitigation by green and blue infrastructure: Drivers, effectiveness, and future needs. Innovation 2024, 5, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Harvey, J.T.; Holland, T.J.; Kayhanian, M. The use of reflective and permeable pavements as a potential practice for heat island mitigation and stormwater management. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Kolokotsa, D. Three decades of urban heat islands and mitigation technologies research. Energy Build. 2016, 133, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. Urban greening to cool towns and cities: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Coutts, A.M.; Livesley, S.J.; Harris, R.J.; Hunter, A.M.; Williams, N.S. Planning for cooler cities: A framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfeey, A.M.M.; Chau, H.W.; Sumaiya, M.M.F.; Wai, C.Y.; Muttil, N.; Jamei, E. Sustainable mitigation strategies for urban heat island effects in urban areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting cities for climate change: The role of green infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; James, P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M.; Ragheb, S.A. Parametric investigation of the solar-thermal performance of tensile membrane roofs in hot-desert climates. Energy Build. 2023, 297, 113449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. On the energy impact of urban heat island and global warming on buildings. Energy Build. 2014, 82, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.; Potchter, O.; Matzarakis, A. Daily and seasonal climatic conditions of green urban open spaces in the Mediterranean climate and their impact on human comfort. Build. Environ. 2012, 51, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Bou-Zeid, E.; Oppenheimer, M. The effectiveness of cool and green roofs as urban heat island mitigation strategies. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 055002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cristo, E.; Evangelisti, L.; Barbaro, L.; De Lieto Vollaro, R.; Asdrubali, F. A systematic review of green roofs’ thermal and energy performance in the Mediterranean region. Energies 2025, 18, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, B.; Lienert, J.; Cook, L.M. Comparing PV-green and PV-cool roofs to diverse rooftop options using decision analysis. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, R.A.; Shanmugam, V.; Narayanan, S.; Razavi, N.; Ulfberg, A.; Blanksvärd, T.; Sayahi, F.; Simonsson, P.; Reinke, B.; Försth, M.; et al. Biochar-added cementitious materials—A review on mechanical, thermal, and environmental properties. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Scrivener, K. Making Concrete Change: Innovation in Low-Carbon Cement and Concrete; Chatham House—The Royal Institute of International Affairs: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cuce, P.M.; Cuce, E.; Santamouris, M. Towards sustainable and climate-resilient cities: Mitigating urban heat islands through green infrastructure. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, H.M.; Shammas, M.I.; Rahman, A.; Jacobs, S.J.; Ng, A.W.M.; Muthukumaran, S. Causes, modeling and mitigation of urban heat island: A review. Earth Sci. 2021, 10, 244–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, M.; Mills, G.; Silva, T.; Girotti, C.; Lopes, A. The underestimated impact of parked cars in urban warming. City Environ. Interact. 2025, 28, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 15686-5:2017; Buildings and Constructed Assets—Service Life Planning—Part 5: Life-Cycle Costing. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/61148.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Andrew, R.M. Global CO2 emissions from cement production, 1928–2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1675–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Setién, J.; Polanco, J.A.; Cimentada, A.I.; Medina, C. Influence of curing conditions on recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for environmental management: An introduction. In Biochar for Environmental Management; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Kua, H.W.; Low, C.Y. Use of biochar as carbon sequestering additive in cement mortar. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 87, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adajar, M.A.; Galupino, J.; Frianeza, C.; Aguilon, J.F.; Sy, J.B.; Tan, P.A. Compressive strength and durability of concrete with coconut shell ash as cement replacement. Geomate J. 2020, 18, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S. Feasibility study on utilization of coconut shell aggregates in concrete. i-Manager’s. J. Struct. Eng. 2023, 12, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Middel, A.; Selover, N.; Hagen, B.; Chhetri, N. Impact of shade on outdoor thermal comfort—A seasonal field study in Tempe, Arizona. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 60, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashua-Bar, L.; Pearlmutter, D.; Erell, E. The influence of trees and grass on outdoor thermal comfort in a hot-arid environment. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).