Abstract

Suzhou’s historic city center serves as a significant repository of Jiangnan cultural memory. However, ongoing urban modernization and large-scale population inflows have introduced notable challenges to heritage preservation, particularly deficiencies in spatial structure and coordination. Accordingly, this study constructs a “Historical Stratification–Spatial Cognition–Existential Narrative” framework to interpret the city’s historical urban landscape. Focusing on Suzhou—a representative canal-based historic city—this research integrates literature review with field investigation. It maps the physical points, lines, and planes of the historical urban landscape to corresponding elements, scenes, and plots within spatial narratives, thereby forming coherent and multi-perspective pathways of historical spatial narration. Moreover, by examining the coupled relationship among space, narrative, and memory, the study analyzes the spatiotemporal evolution and cultural characteristics of Suzhou’s water–land symbiosis. As a result, it identifies the intrinsic logic and mechanisms of spatial narratives within historic urban landscapes and expands the applicability of spatial narrative theory. Overall, the findings provide new insights for uncovering and revitalizing cultural heritage in Suzhou’s Old City within the Jiangnan context, while offering innovative conservation approaches and methodological strategies for reconstructing historical memory and guiding sustainable urban renewal.

1. Introduction

Cities serve as repositories of human civilization, encapsulating collective memory across time and space. While the urban landscape possesses inherent spatial and cultural attributes, its organizational structure and meaning evolve through social dynamics, transformation, and experience [1]. Accordingly, cities shaped by diverse historical trajectories and socio-cultural contexts develop into distinct humanistic environments, each embodying unique spatial identities, expressing diverse cultural forms, and narrating localized stories of place and character [2].

1.1. Current State of Suzhou Ancient City’s Urban Layout

A late Tang Dynasty poem famously states, “When you come to Gusu, every household rests beside the river”. This poetic image vividly captures the distinctive urban layout of Suzhou’s historic city, where residences were traditionally built along waterways, forming a picturesque waterside settlement. Gusu, a time-honored Jiangnan city with more than 2500 years of urban history, was shaped by water and prospered through its river network. Its dense system of canals intersects with streets, while scattered lakes create a spatial pattern often compared to a water labyrinth—a characteristic that has earned Suzhou the name “Venice of the East”. Notably, Suzhou’s Old Town preserves the collective memory of Jiangnan culture and is recognized as the cradle of Wu Culture. Its urban morphology—including the characteristic parallel water–land transportation system—has remained largely intact for centuries, consistent with the configuration recorded in the Southern Song Dynasty’s Pingjiang Map.

However, with the advancement of modern urbanization—notably the construction of Ganjiang Road—the original network of streets and alleys was significantly disrupted. This major thoroughfare interrupted the once-continuous land–water spatial fabric, thereby weakening the integrity of historical urban spaces. At the same time, rapid economic development and substantial population inflows reshaped the local social ecosystem. Traditional communities that carried collective memory became diluted, while new residents often lacked emotional attachment to the city’s historical context, resulting in a progressive erosion of urban memory. Consequently, urban heritage has become increasingly fragmented, and the intangible, everyday memories embedded in streets, riverbanks, and local life are gradually disappearing. Although the spatial strata of different historical periods constitute layered historical information, such implicit narratives remain obscured without systematic analysis and holistic recognition.

Therefore, it is essential to develop a comprehensive and forward-looking system for the conservation and sustainable utilization of Suzhou’s ancient city heritage. This system should promote a shift from static historical preservation toward revitalization and narrative-based interpretation, thereby enabling the city to more effectively respond to the challenges posed by contemporary urban development.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

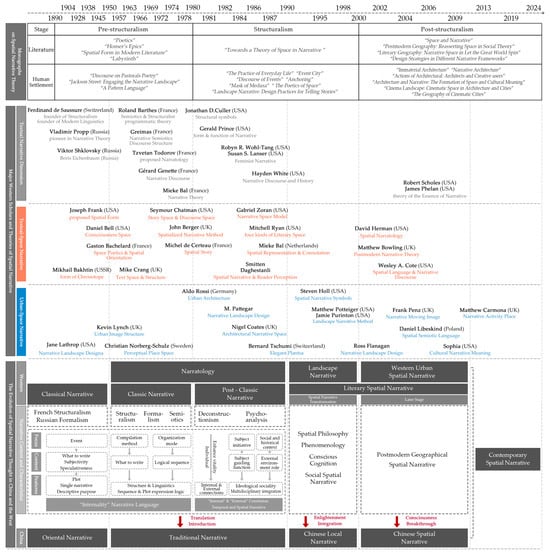

1.2.1. The Developmental Trajectory of Spatial Narrative Theory (Figure 1)

Spatial narratology emerged in the early twentieth century as Western narrative theory increasingly emphasized spatial dimensions, thereby establishing a spatial cognitive framework informed by geography, sociology, urban studies, psychology, and anthropology [3,4,5,6]. Within this framework, spatial narrative describes the process through which narrative subjects employ both tangible and intangible spatial elements as expressive media. Drawing on the semiotic relationship between signifier and signified, spatial narrative transforms social meanings into spatial experiences, enabling recipients to develop perceptual and cognitive engagement with place. Structurally, spatial narrative constitutes a system of spatial juxtaposition characterized by coexistence and synchronicity and operates through mechanisms of temporal presence, spatial logic, and causality. Accordingly, it can be understood as a methodological “spatiotemporal complex”. As an important research direction in architecture, spatial narrative has evolved through sustained interdisciplinary integration, shifting from its roots in literary and aesthetic theory toward broader architectural and urban applications [7]. As a result, continued theoretical and methodological innovation has progressively refined and expanded the framework of spatial narrative studies [8].

Within the field of spatial design, an increasing number of architects, urban planners, and scholars have adopted multidisciplinary approaches to advance the study of spatial narrative [9,10]. In architectural practice, early explorations of narrative techniques emerged in the 1970s, as demonstrated in Alvaro Siza’s Theatre of the World, Bernard Tschumi’s Parc de la Villette in Paris, and Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum Berlin. These projects employ symbolic and metaphorical languages informed by narrative theory to construct spatial discourse and evoke layered experiential meaning. Accordingly, narrative offers a systematic framework for interpreting-built environments and can be effectively integrated with visual media to investigate architectural space. Notably, Sophia Psarra’s seminal work Architecture and Narrative: The Construction of Space and Its Cultural Meaning articulated the significance of narrative in architectural cognition, spatial order, and sociocultural meaning, establishing a major foundation for contemporary architectural narratology [11].

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework outlining key scholars, theoretical stages, and interdisciplinary developments in spatial narrative studies, illustrating the evolution from classical narratology to contemporary spatial and landscape-based approaches [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. (Source: author).

Among the most influential contributions, Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City identifies five fundamental elements that shape urban perception, thereby pioneering the integration of spatial cognition with urban spatial structure [20]. Similarly, in The Spirit of Place, Christian Norberg-Schulz underscores the phenomenological relationship between people and their environments, arguing that place inherently carries narrative and experiential meaning [21]. Ross King’s The Story of the City: Narrative and Urban Life Studies further investigates urban form through multiple narrative perspectives [22]. At its core, spatial narrative arises from the dynamic interaction between people and their spatial environments, which constitutes the foundational basis of narrative formation. Accordingly, theoretical models contend that understanding spatial cognition requires analyzing the narrative systems embedded within spatial environments. Research on the relationship between narrative and urban spatial structure commonly employs quantitative, structural, comparative, and case-based analytical approaches, thereby advancing interdisciplinary dialogue across urban design, architecture, and cultural geography.

Overall, contemporary academic research on spatial narrative can be categorized into four principal domains: ① The first pertains to conceptual understanding and historical evolution, focusing on defining spatial narrative and tracing its localized adaptations and theoretical development; ② The second involves integrating spatial narrative theory with urban planning, with the aim of establishing systematic frameworks for narrative-oriented urban spaces; ③ The third addresses analytical methods and practical applications, in which scientific tools—notably spatial syntax—are employed to interpret and evaluate narrative spaces within urban contexts; ④ The fourth concerns the design and pedagogical translation of spatial narratives, encompassing architectural design, spatial expression, and educational practices. Accordingly, existing research on spatial narratives in heritage conservation largely represents an extension and reinterpretation of modern architectural narrative design, rather than a fully independent theoretical paradigm.

1.2.2. The Application of Spatial Narrative Theory in Heritage Conservation

In the process of urban development and cultural heritage conservation, contemporary research and practices often separate tangible and intangible elements. This segregation results in a fragmented and one-dimensional approach to urban heritage conservation. Specifically: ① Loss of cultural significance—the conservation of physical spaces frequently fails to embody their cultural meaning, leading to structures that lack spiritual resonance; ② Weakening of social value—the transmission of intangible heritage is often detached from spatial contexts, making it difficult to embed within contemporary urban life; ③ Limited public engagement—citizens struggle to perceive and experience the historical and cultural significance of urban heritage through spatial interaction.

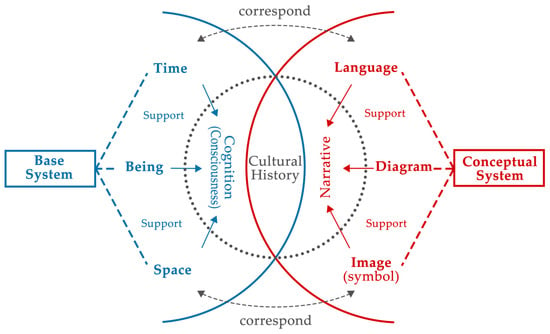

Therefore, to address the disjunction between tangible and intangible dimensions that emerges during urbanization, spatial narrative—conceptualized as a method of expressing emotional and cultural meanings through spatial form—possesses distinct contemporary relevance [23]. This is evident in its ability to visualize intangible cultural information within physical space, integrate dispersed cultural elements, construct local cultural identity, and uncover the intrinsic dynamics of urban evolution. Specifically, grounded in the ontological logic of spatial narrative, this approach serves as a means to recognize spatial interconnectivity and to interpret relationships among urban entities [24]. It thereby establishes a historical spatial narrative framework for the study of historic cities (Figure 1). Within this framework, the spatial elements of historic cities are systematically extracted, integrated, encoded, and correlated to construct a spatiotemporal continuum linking the past and the present, thereby offering new pathways for sustaining urban cultural continuity [12] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Relationship Between Spatial Narratives and Spatial Cognition. (Source: author).

Over the past several years, supported by extensive practical experience, our research team has focused on the conservation and adaptive utilization of urban heritage sites along the Grand Canal, thereby establishing a robust research foundation. Throughout this process, we identified the profound potential of spatial narrative theory as an effective framework for interpreting and reinforcing the authenticity and integrity of heritage values. Accordingly, this study seeks to develop a strategic framework for historical urban heritage conservation grounded in spatial narrative theory, using the Grand Canal as a representative living linear heritage site. The strategy primarily consists of two principal components:

- 1.

- Identify and classify the components of historical spatial narratives within historic cities, focusing on both tangible and intangible elements embedded in the urban spatial context, so as to more intuitively reveal the cities historical evolution and spatial characteristics.

- 2.

- Construct spatial narrative structures by organizing and integrating narrative elements through appropriate narrative techniques, thereby enabling multidimensional evaluations of traditional urban districts and reconstructing the cultural memory of canal cities through spatial sequence narratives.

Through the above analysis, a value-centered narrative framework emerges in which the linear heritage of the canal constitutes the primary object, and spatial narrative methods clarify how spatial cognitive subjects develop multi-layered value perceptions and emotional attachments. Accordingly, these insights inform and guide strategies for heritage conservation and revitalization. Compared with traditional conservation models, the strength of this framework lies in its systematic treatment of canal heritage as an integrated whole, emphasizing both its historical evolution and its contemporary reinterpretation. As a result, heritage conservation is transformed from a focus on physical restoration to a deeper social practice that shapes collective memory and reinforces cultural identity.

By examining the spatial forms, functional layouts, and cultural connotations of historical landscapes in canal cities across different historical periods, this study organically integrates tangible and intangible elements within historical spaces. It introduces spatial narrative theory into the field of cultural heritage conservation, establishing a multi-layered and multidimensional narrative framework. Such an approach enhances the authenticity and integrity of heritage sites and provides a renewed perspective for interpreting, analyzing, and shaping the spirit of place in canal city environments. Through the design of historical spatial narratives, the collective memory and symbolic identity of canal culture are embedded within contemporary urban spaces, thereby fostering public recognition and a sense of belonging while sustaining the historical and cultural continuity of canal heritage.

2. Materials and Methods

As a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site, the Grand Canal of China represents a crucial component of the nation’s historical and cultural legacy, with canal cities functioning as essential carriers of this heritage [25]. Spatial narrative, serving as a medium for conveying stories, emotions, and cultural meanings through physical space, plays a distinctive role in preserving cultural context and continuity. Building on this foundation, the present study seeks to establish a historical spatial narrative framework grounded in the core principles of spatial narrative theory. Drawing upon a comprehensive review of multi-source historical data and extensive field research on Suzhou urban heritage, the framework is developed with “heritage value” as its primary evaluative criterion. This approach facilitates multidimensional assessment of historic urban quality and provides a more effective means of articulating the city’s intrinsic spatial and cultural character. The specific structure and methodological content are outlined as follows.

2.1. Methods

Applying spatial narrative theory and methodology to historic urban spaces—guided by Kevin Lynch’s concepts of spatial cognition and urban perception—establishes a hierarchical narrative structure that progresses from urban pattern narratives to regional, street, node, and scene narratives. Within this framework, streets and lanes, functioning as the connective tissue of the urban fabric, organically integrate diverse spatial elements and thereby become critical carriers of spatial narratives. Accordingly, the linear spatial narrative of historic cities can be systematically developed through the progressive logic of “element extraction—structural analysis—meaning interpretation” (Table 1).

Table 1.

Linear Historical Spatial Narrative Structure Framework. (Source: author).

2.1.1. Define the Research Scope and Content and Extract Key Elements

Building upon a linear spatial narrative framework, historical documents of canal cities are analyzed through historical scene localization and element extraction. In combination with field investigations, the identified elements are correlated with components of the historical spatial narrative and further subjected to value analysis, thereby constructing an interconnected element network that reveals the spatial narrative logic of canal cities.

Define the scope and content of historical document collection, integrate multi-source data, and extract key elements. The collection and organization of historical materials along the canal route—including historical records, maps, literary texts, and photographic archives—are conducted to establish a comprehensive historical dataset. By combining field investigations with digital technologies such as GIS and 3D laser scanning, both spatial elements (e.g., architectural forms, street patterns, landscape nodes) and cultural elements (e.g., traditional crafts, folk customs, and collective memories) are systematically identified and extracted for subsequent analysis [26,27,28].

For the extracted elements, we conduct a value assessment according to their relevance to the defined narrative theme. Following narrative logic, we establish the thematic focus—such as urban canal governance—and, through a systematic review of historical records, maps, and archival documents, identify elements directly or indirectly associated with that theme. These elements are then evaluated and scored based on authenticity, completeness, and multiple value dimensions, including historical value (period), artistic value (aesthetic rank), technological value (structural characteristics), social value (contemporary function), and emotional value (cultural significance). This evaluation framework supports the development of narrative units and the structuring of narrative pathways.

2.1.2. Construct a Linear Narrative Structure Based on the Canal Narrative as Its Logical Framework

Drawing on phenomenology, anthropology, semiotics, and narratology, this study explores the potential application of spatial narratives within historical urban spaces. By employing points (e.g., architectural typologies, docks, granaries, locks), lines (e.g., commercial streets, canal routes), and planes (e.g., neighborhoods, residential blocks) as core analytical elements, the framework establishes a networked model that emphasizes temporal, social, and cultural dimensions. Accordingly, this model sequentially expands spatial pathways to enrich the connotations and extend the dimensions of historical spatial narratives.

- Temporal Dimension: Through spatial sequencing, this study investigates how spatial narratives re-enact historical memory across temporal layers. It further examines how dynamic spatial elements—such as variations in light and shadow or seasonal transitions—can be integrated into historical spaces to reinforce temporal continuity and enhance the experiential perception of historical memory.

- Social Dimension: Grounded in Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production, this study adopts sociological and anthropological perspectives to construct an interactive model of historical spatial narratives. The model integrates spatial sequencing with community engagement, taking social structure, social interaction, and social memory as its core components. Accordingly, it seeks to reinforce the social value and vitality of canal-based historic cities.

- Cultural Dimension: Drawing on theories and perspectives from cultural studies and semiotics, this approach examines the intangible elements embedded within spaces. Through symbols and their associated meanings, it reveals how physical spaces embody and transmit cultural memory, thereby shaping collective identity. This process not only forges cultural continuity but also conveys cultural essence and highlights the distinctiveness of place.

Based on the above discussion, a research framework for narrative spatial patterns can be constructed and organized around the sequence of “narrative theme—narrative units—narrative pathway organization—narrative atmosphere creation”. This theoretical framework enhances the reconstruction of historical memory and supports the renewal and interpretive transformation of historical urban spaces.

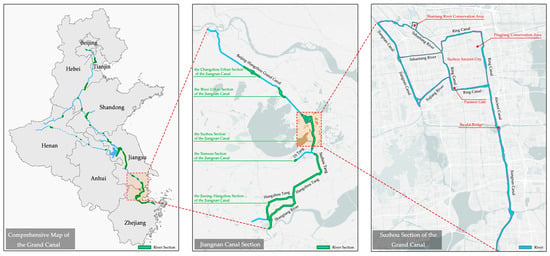

2.2. Research Area

At the 2014 World Heritage Committee meeting in Doha, the Grand Canal of China was officially inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Extending across the northeastern and central-eastern plains of China, the Grand Canal stretches from Beijing in the north to Zhejiang Province in the south [25]. Initially constructed in sections beginning in the 5th century BC, it was first unified as an imperial communication and transportation system during the Sui Dynasty in the 7th century AD. This undertaking resulted in a series of immense construction projects, forming the largest and most sophisticated civil engineering achievement in the world prior to the Industrial Revolution. The canal became the backbone of the empire’s inland transportation network, facilitating the movement of grain, raw materials, and other essential goods, and ensuring food security for the population. By the 13th century, the system extended over 2000 km of artificial waterways, linking five of China’s major river basins. Notably, the Grand Canal has continued to play a vital role in sustaining China’s economic prosperity and spatial integration, and it remains an essential waterway in active use today (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Research Scope: The location of the Suzhou section within the entire length of the Grand Canal of China. (Source: drawn by the author based on the map of The Grand Canal—maps of inscribed property, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1443/maps/ (accessed on 17 October 2025)).

The Grand Canal of China flows unceasingly across the landscape, extending for thousands of miles as a vast and enduring artery of civilization. The Jiangnan section, first excavated during the late Spring and Autumn Period (486 BC), underwent two major reconstructions during the Sui (610 AD) and Yuan (1341 AD) Dynasties. It continues to function today as a vital waterway for urban transportation and logistics. Suzhou, located along its banks, flourished through canal-driven prosperity and regional exchange. The multiple historic cultural districts within the Suzhou section vividly demonstrate the Grand Canal’s profound influence on regional development, underscoring its formative role in shaping exemplary canal cities such as Suzhou within the broader narrative of global urban history [29]. The canal network not only structured the city’s waterways and defined its road grid but also continues to provide essential infrastructure and cultural support to contemporary urban life.

This study focuses on Suzhou’s historic urban district, a site of outstanding representativeness within the Grand Canal system. As the canal meandered through Suzhou urban fabric, it inscribed a series of spatial and cultural watermarks along its historical course, from which streets and alleys gradually unfolded [30,31]. Through the stratification of successive historical periods, time acquired a tangible spatial form, and the city evolved into a landscape of harmonious coexistence between land and water. Within these interwoven networks, Suzhou urban culture has continued to grow, circulate, and flourish along the lifeblood of its waterways.

3. Results

3.1. Narrative Analysis of the Urban Spatial Fabric Along the Suzhou Canal Section

3.1.1. The Historical Connection Between Suzhou and the Grand Canal

The Suzhou section of the Grand Canal can be broadly divided into three segments: the Western Section from Wangting to Baiyangwan, also known as the Suzhou–Wuxi Section; the Ancient City Section, which extends from Baiyangwan through Suzhou historic city center to Baodai Bridge; and the Southern Section south of Baodai Bridge, continuing through Wujiang to Jiaxing, also referred to as the Suzhou–Jiaxing Section [32]. Historically, under the combined influence of six major shifts in the Yellow River’s course and various human management interventions, the navigable waterways of the Suzhou section experienced alternating periods of prosperity and decline. Nevertheless, its fundamental route remained largely consistent, continuing to serve as a vital artery for transportation and cultural exchange [33].

Following the founding of the People’s Republic of China, and particularly after the rerouting of the Suzhou section in 1986, the Shantang, Shangtang, and Xujiang canals—though still connected to the Grand Canal water system—ceased navigation and gradually became abandoned waterways [34]. In recent decades, ecological assessments of cities along the Grand Canal have indicated that vegetation has exerted the most significant influence on the ecological environment of cities located in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River Basin. Since 2019, vegetation has become the dominant factor shaping the ecological conditions along the Suzhou section.

Beyond human canal engineering, the evolution of the Suzhou section has also been influenced by natural hydrological processes, including river course migration and riverbed evolution. The city’s current multi-tiered river system, with the Grand Canal as its structural backbone, has defined Suzhou distinctive water network. Historically, during periods when water transport in the Jiangnan region offered superior convenience and efficiency, this hydrological framework laid the foundational conditions for Suzhou urban development [35].

3.1.2. Characteristics of the Suzhou Section of the Grand Canal

Through historical accumulation, the Suzhou section of the Grand Canal has acquired the following characteristics [36]:

- Dating back more than two millennia, the Suzhou section of the Grand Canal—originally excavated as the Han Canal under King Fuchai of Wu—has long served as a vital waterway in southern China, forming the foundation of Suzhou’s hydraulic and urban development.

- Benefiting from its gentle topography and abundant water resources, the Suzhou section has maintained continuous north–south navigation and cargo transport for over two thousand years. It remains a key artery for regional circulation and goods distribution.

- Suzhou was both born from and prospered along the canal [37]. The waterway course shaped the morphology of urban and rural street networks as well as the city’s overall form, giving rise to a distinctive canal-based spatial structure and a rich array of landscape heritage.

3.1.3. Narrative Analysis of Suzhou’s Urban Spaces

Spatial narratives share a defining characteristic: they require a comprehensive understanding of spatial wholeness and holistic thinking—that is, the synthesis of relationships between the whole and its constituent parts within a given space [38,39]. By analyzing the spatial typologies and cultural characteristics of Suzhou’s canal system, three distinct categories can be identified: ① moats that integrate waterways, city walls, and gates; ② historic districts characterized by a dual grid pattern of water and land, such as the Pingjiang Road and Shantang Street Historic Districts; and ③ canal-related cultural complexes, including Suzhou’s classical gardens and former government offices. Each category embodies unique spatial narratives and reveals distinct urban characteristics rooted in the city’s historical evolution [40]. Examining the spatial narrative logic of Suzhou’s canal spaces and translating this linear spatial narrative into concrete spatial forms provide a more tangible interpretation of the city’s essence and its enduring historical context.

3.2. Segmented Narratives of Suzhou Canal’s Water and Land Spaces

Following a comprehensive analysis of the Suzhou section of the Grand Canal, this study focuses on three significant and representative nodes or areas for detailed examination [41]. The discussion unfolds across three interrelated layers: the spatial–temporal historical narrative, the spatial–cultural cognitive narrative, and the spatial–material carrier narrative. It should be emphasized that these three narrative dimensions constitute an integrated and dynamic whole, mutually influencing and permeating one another. They progress hierarchically—from macro to micro scales, from external to internal perspectives, and from the visual and tactile to the symbolic and metaphorical. The rationale for this tripartite analysis is to gain deeper insight into the narrative characteristics of spatial form, clarify the intrinsic spatial features of canal-based heritage, and enhance public spatial cognition.

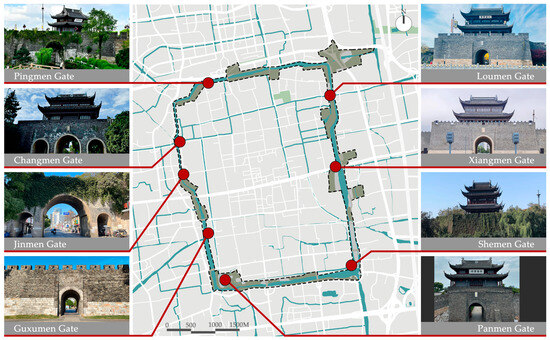

Among these, the moat system—comprising waterways, city walls, and gates—served as the ancient boundary of Suzhou, defining the city’s spatial limits. In imperial China, urban boundaries were delineated by walls, and development was generally confined within them; accordingly, the moat area functioned as the city’s defining perimeter. The historic districts characterized by a dual grid pattern of water and land represent the most renowned water-based residential form in the Jiangnan region along the lower Yangtze River. Their streets and alleys run in parallel, where residents lived, worked, and conducted production along the waterways, embodying the quintessential spatial and social characteristics of a canal city [42]. Canal-related cultural complexes encompassed administrative institutions responsible for both municipal governance and canal management. These offices constituted essential components of ancient Chinese urban administration. Given the strategic importance of canal transport, transshipment, and storage, dedicated canal management systems—independent of general government offices—were established in all canal-connected cities. Similarly, the classical gardens of Suzhou, also inscribed on the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage List, emerged as cultural products of the canal prosperity. These gardens epitomize the pinnacle of Jiangnan cultural refinement, reflecting the aesthetic achievements and spatial ingenuity of Chinese garden art during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

3.2.1. Moat (Waterway, City Walls, and City Gates)

- 1.

- Historical Spatial Narratives: From City Walls to Parks

The spatial–temporal narrative takes time as its axis and space as its structural foundation. Within urban environments, history itself functions as a documentary form of storytelling. Spatial elements embedded in historical contexts readily evoke collective memory and historical consciousness. Moreover, the narrative power of historical scenes experienced directly within physical space often exceeds that of indirect or textual interpretations of history. Accordingly, this approach establishes a clearer spatial order and strengthens the cognitive and emotional connection between individuals and their spatial environment.

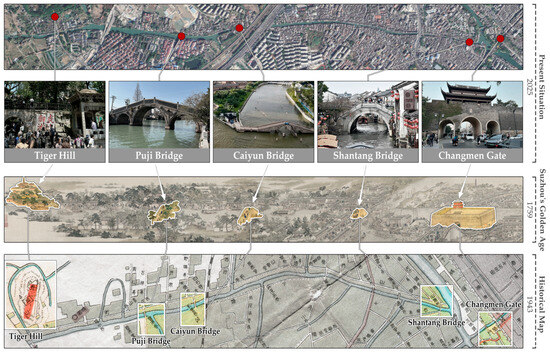

The spatial–temporal order of Suzhou moat system has been evident since the city’s founding, when it first emerged as a defensive structure. Over time, this system evolved into a major urban landmark of enduring historical and cultural significance. The area encompassing the city walls and moat forms an integral component of Suzhou’s traditional urban identity. Unlike many other Chinese cities, Suzhou retains a remarkably complete water system integrated with its city walls. Originally constructed during the Spring and Autumn Period, the moat has survived more than two millennia of historical transformation and remains a defining element of the city urban fabric. Consequently, the presence of moats and walls required all routes entering or leaving the city to pass through gates, thereby shaping a distinctive and orderly urban landscape. Each gate possessed a unique spatial form that corresponded to its specific function. Notably, Changmen Gate served as a major transportation hub connecting Suzhou ancient city to the Grand Canal. It also marked the starting point of Shantang Street, which extended toward the scenic Tiger Hill. As a result, the vibrant flow of goods and people fostered the formation of a prosperous commercial district that has thrived since the Song Dynasty. Today, the Changmen area endures as the most representative spatial remnant of that dynamic historical period in the collective memory of Suzhou’s residents.

From the Spring and Autumn Period to the present day, Suzhou moat and city walls have carried the weight of its profound historical legacy while sustaining remarkable vitality in the modern era. Although the traces of past warfare have long disappeared, the dynamic rhythms of urban life continue to unfold along these enduring spatial structures (Figure 4). Accordingly, the moat system not only embodies defensive origins of the city but also symbolizes the continuity of its urban spirit through time.

Figure 4.

The moat, city walls, and the remaining eight city gates. (Source: author).

- 2.

- Spatial Cognitive Narratives: From Boundaries to Interfaces

Historically, city walls and moats delineated the physical and symbolic boundaries of urban space. For centuries, they constituted Suzhou most formidable defensive system, clearly distinguishing the “inner city” from the “outer city.” Even today, many long-term residents continue to identify locals based on whether they live within the ancient walls. This enduring spatial distinction not only reveals the lasting social and cultural imprint of the walls but also underscores their profound significance within Suzhou collective memory and urban heritage.

As Suzhou continued to develop and expand, its municipal boundaries gradually extended beyond the confines of the ancient city. The original moat, city walls, and the surrounding areas became enduring vessels of Suzhou historical memory and traditional way of life. Following Suzhou designation as both a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a National Historic City, stringent regulations were implemented to control urban development within the old city. In response to increasing public demand for waterfront accessibility and green space, the extensive zones formed by the moat and city walls were subsequently transformed into public parks, effectively connecting the landscapes inside and outside the historic core. As a result, when people began to view the old city from beyond its walls, its historical boundaries gradually blurred, and the skyline of the ancient city evolved into a visible interface between Suzhou’s past and present.

- 3.

- Existence Narrative: As a Vehicle for Carrying Intangible Cultural Heritage

The Suzhou Ancient City Wall measures approximately 12 m wide at its base, 9 m at the top, and over 8 m in height, enclosing a perimeter of around 15 km. Most of the existing brick walls and gate towers date from the early Qing Dynasty, while sections such as Panmen and Xumen preserve architectural features characteristic of the late Yuan Dynasty. The wall’s irregular rectangular form follows the natural topography of the city. Historically, it functioned as an integrated system combining political administration, military defense, and waterway transportation. Today, the wall has been revitalized through urban renewal and now serves as a vibrant public space, hosting community cultural activities such as poetry recitals, calligraphy exhibitions, and local festivals.

Beyond cultural events, the area surrounding Suzhou ancient city walls and moat has also become a popular filming location for numerous films and television dramas. Its profound historical atmosphere and cultural depth provide abundant inspiration and material for visual storytelling. As a result, many classic productions have been filmed here, enabling audiences to gain a deeper appreciation of Suzhou rich historical and cultural heritage. With the continuous advancement of digital technology and evolving aesthetic preferences, the city walls have also become a stage for large-scale cultural performances, including fireworks displays and immersive light shows held during traditional Chinese festivals. Consequently, walking through these illuminated scenes evokes a sense of temporal immersion, allowing visitors to experience the city ancient charm through modern visual expression. This fusion of heritage and contemporary creativity defines the enduring allure of Suzhou ancient city.

It is precisely this millennia-old urban configuration of land and water that has shaped the distinctive spatial narrative of renewal and continuity within this ancient cityscape.

3.2.2. Historical District Featuring a Dual Land–Water Chessboard Layout

If the moat and city walls define the city outline and structural framework, then the dual grid pattern of streets running parallel to land and water forms its circulatory system—it’s very muscles and blood vessels. Notably, the core spatial narrative of this historic district resides within the fabric of everyday life, where daily routines, human interactions, and cultural practices continuously shape and sustain its living heritage [43,44,45,46].

- 1.

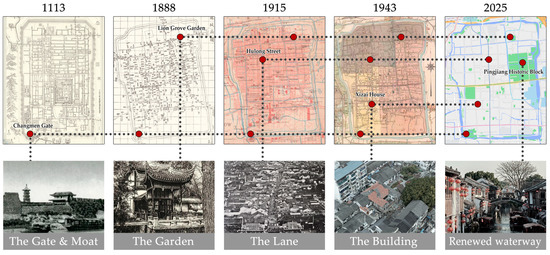

- Historical Narrative: The Unchanging Urban Fabric of a Millennium

The Jiangnan region is characterized by low-lying terrain interlaced with a dense network of waterways. Since ancient times, the people of Suzhou have established their settlements along these waters, shaping a distinctive pattern of water-oriented urban development. Beginning in the Song Dynasty, a dual grid pattern gradually emerged within the city’s streets and alleys, defined by the spatial principle of “streets adjacent to rivers, with water and land routes running parallel.” This spatial configuration reached its zenith during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The concept of “rivers and streets running parallel, water and land coexisting” describes the grid-like network formed by interwoven waterways and parallel streets, which together created the city’s dual grid morphology. The buildings constructed along these canals, closely integrated with the streetscape, collectively formed the quintessential scenery of Jiangnan water towns.

The southern regions of China, largely spared from the devastation of warfare, historically remained prosperous and culturally vibrant. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the flourishing of handicrafts, commerce, and industry—together with the active trade along the Grand Canal—fueled sustained economic prosperity in the Suzhou region. Notably, the Shantang Street area has served as Suzhou principal commercial and cultural hub since the Tang Dynasty, thriving due to its advantageous water and land transportation network. Situated between the Shantang River and bustling marketplaces, it was vividly depicted in Cao Xueqin Dream of the Red Chamber as “one of the most opulent and elegant places in the mortal world” [47]. Similarly, the Pingjiang Road Historic District embodies this enduring legacy [48]. Oriented along the Pingjiang River in the northeast, extending from Northeast Street to East Ganjiang Road, it has preserved its original river alignment and street pattern for more than eight centuries. The district exemplifies the distinctive spatial structure of “parallel water and land routes, with streets adjacent to the river,” and retains the quintessential Jiangnan water-town landscape of “small bridges over flowing water, whitewashed walls, and black-tiled roofs.” As a result, it stands today as one of Suzhou most historically significant and emblematic canal-side streets.

Within the enduring fabric of Suzhou streets and alleys, the city historical spatial narrative remains continuous and multilayered. Historically, waterways functioned as vital transport corridors for logistics and trade, while the parallel streets that developed alongside them fostered neighborhood commerce and vibrant street markets. Over time, street vendors and small businesses gradually shaped these spaces into dynamic commercial streets that embody both economic vitality and cultural tradition. Consequently, this landscape represents a living temporal narrative of everyday life and commercial activity—one that seamlessly connects the city historical past with its contemporary urban experience.

- 2.

- Spatial Cognitive Narratives: Paths and Nodes

The streets and alleys of urban spaces constitute multidimensional environments composed of multiple planes and structural layers. Specifically, these environments comprise three primary spatial interfaces: the ground interface that extends across the street surface, the side interfaces formed by building facades flanking the road, and the upper interface encompassing the sky and distant visual corridors. Fundamentally, street morphology serves as a tangible expression of the temporal evolution of urban development. Beyond being shaped by natural, cultural, economic, and technological forces, the diverse configurations of urban streets and alleys are intrinsically tied to each city distinctive modes of life and spatial practices. Notably, street morphology also reflects the functional organization of the city, as its spatial characteristics inherently respond to evolving production and living patterns. As a result, street spaces continually adapt through functional transformation, thereby sustaining the continuity of urban culture and identity.

Suzhou City was born and flourished alongside its canals. Throughout its long history, the region has relied almost entirely on its extensive network of waterways to sustain both internal circulation and external exchange. Along these waterways, corresponding land routes gradually emerged, forming a dual transportation structure that integrates waterborne and terrestrial mobility. When viewed through the lens of urban morphology, the geometric patterns and topological relationships of this network reveal a cognitive map of the city—an intricate overlay of two systems running in parallel, water and land. From the perspective of a boat gliding along the canals, one perceives the horizontal continuity of the water surface, the quays and docks, and the shimmering reflections—a flowing yet subtly detached sensory experience. Conversely, from the perspective of walking along the streets, one encounters the tactile rhythm of bluestone pavements, the intimate proximity of storefronts, and the ascending steps of stone bridges—an embodied, vertical narrative of daily life. Together, these perspectives construct a multidimensional spatial narrative that intertwines perception, movement, and memory within Suzhou urban fabric.

Within the linear spatial narrative of Shantang Street and the Pingjiang Road Historic District, the central theme centers on the everyday rhythms of commerce and social interaction in the marketplace. Walking leisurely along Shantang Street—from Xinmin Bridge toward Shantang Bridge—the body experiences a continuous sense of spatial guidance, accompanied by the lively sequence of storefronts and street activities. These spatial experiences collectively articulate an intuitive, outward-facing narrative of commerce and public life. By contrast, the Pingjiang Road Historic District presents a more intimate and immersive cognitive narrative, where the interplay between the main street and its branching alleys creates a sense of human-scale warmth, tranquility, and temporal depth (Figure 5). Together, these two spaces exemplify the coexistence of dynamism and serenity that defines Suzhou historical urban life.

Figure 5.

From top to bottom: A Prosperous View of Gusu, a map of Suzhou city in 1915, and a current aerial photograph of Suzhou. It is evident that the dual grid pattern of streets and alleys, intertwined with both land and water, has remained largely unchanged. (Source: author).

- 3.

- Existence Narrative: A Moving Panorama of Everyday Life

Within Suzhou ancient urban fabric, preserved and continuously evolving over millennia, the “dual grid pattern of water and land” is far more than a static spatial blueprint. Rather, it forms a dynamic, three-dimensional living landscape whose physical structure functions as the narrative stage for everyday urban life. The intricate network of pathways and carefully articulated junctions defines the classic Jiangnan model of “streets bordering rivers, with land and water coexisting.” Accordingly, this pattern unfolds in a rhythmic linear sequence where “roads cross rivers and bridges follow in succession.” Moreover, bridges, wharves, and revetments interlace the waterways and streets, collectively forming a resilient spatial foundation that has sustained and reflected the unfolding drama of urban life for thousands of years.

Historically, this spatial stage hosted the everyday narratives of livelihoods and social interaction. Waterways functioned as the city arteries for transporting essential goods. The parallel streets and alleys acted as the city veins for pedestrian movement and commerce, lined with teahouses, taverns, and artisan workshops that collectively animated a vivid urban landscape. Furthermore, docks and riverbanks served as communal living spaces where residents washed clothes, traded goods, and exchanged neighborhood news. Accordingly, these dual water–land pathways were not merely channels of movement but also dense social networks that sustained the dynamic rhythms of everyday urban life.

Today, this historic stage presents a renewed performance where tradition and modernity intertwine. It remains a vibrant cultural hub, yet its characters and narratives have evolved into an immersive open-air museum and cultural experience space. Visitors glide through the waterways by boat, observing this floating panorama from unique vantage points, or pause at cafés near ancient bridges to enjoy the leisurely fusion of the old and the new. Notably, many traditional residences have been revitalized as venues for Kunqu Opera and Pingtan storytelling. When the distinctive sound of water-grinding resonates within these waterfront courtyards, it represents the living transmission of intangible cultural heritage within its authentic setting. Furthermore, digital innovations such as augmented reality tours reconstruct historical scenes, transforming ordinary strolls into immersive journeys through time. As a result, this enduring spatial stage, marked by its adaptability and inclusivity, successfully bridges the ancient narratives of urban life with contemporary expressions of cultural consumption and experiential tourism. According to the UNESCO evaluation committee, the district’s conservation plan “exemplifies urban revitalization,” as its achievements in preserving historical character, maintaining social fabric, and establishing sustainable operational models demonstrate that historic districts can achieve balanced development. By adhering to the principle of restoring structures to their original state, the Pingjiang Road Historic District has avoided the displacement of residents for large-scale commercial projects.

3.2.3. Canal-Related Cultural Complex

When the moat and city walls are regarded as the city’s structural framework and the dual grid pattern of land and water as its lifeblood, the cultural complexes associated with canal culture constitute its soul and spirit. Notably, these complexes directly reflect the city’s functional organization and serve as tangible manifestations of its cultural identity. Over time, through continuous transformation and adaptation, they have evolved from centers of imperial administration and expressions of literati aesthetics into World Heritage sites that embody both historical continuity and cultural resilience.

- 1.

- Historical Narratives: The Order of Power and the Integrity of Literati

Suzhou, located on the Taihu Plain and characterized by its dense network of waterways, has served as a crucial hub for water transport since ancient times. The construction of the Luoyang Grand Canal during the Sui and Tang dynasties, and particularly the straightening and extension of the canal to Beijing in the Yuan dynasty, positioned Suzhou at the strategic intersection where the empire’s north–south trunk canal converged with the east–west inland waterways linking Taihu Lake to coastal ports. As a result, Suzhou gradually developed into a national distribution center, transshipment hub, and commercial nexus for major commodities such as grain, salt, silk, and cotton cloth. Given the scale and complexity of this logistics system, which was vital to the national economy and people’s livelihoods, an efficient administrative framework became essential. Accordingly, a specialized canal administration was established. Its institutional structure included the Grain Transport Administration, which oversaw the collection, inspection, transportation, and storage of grain taxes shipped to the capital; customs offices responsible for regulating merchant vessels and collecting tariffs; and the Suzhou Textile Bureau, which directly procured silk fabrics for the imperial court.

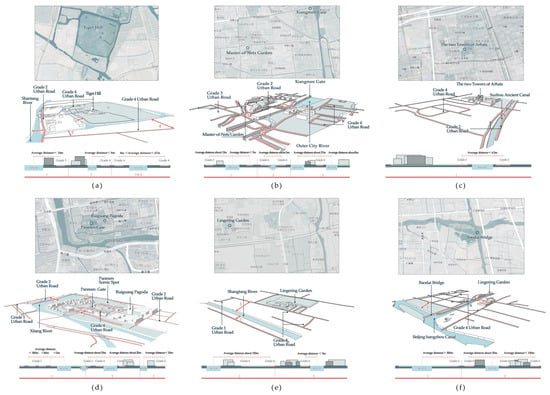

The canal management system and commercial networks generated substantial wealth, which primarily flowed into three social groups. First, many Suzhou natives who served as officials in the capital or other regions returned home after retirement, bringing with them accumulated wealth and administrative experience. Second, merchants engaged in the trade of silk, cotton cloth, grain, and other commodities accumulated considerable capital through canal-based commerce. Third, the flourishing class of literati and scholars emerged from the city expanding economic base. As wealth and culture converged, the pursuit of spiritual refuge and cultural self-expression became increasingly prominent, giving rise to Suzhou classical gardens. Influenced by Confucian ideals, these gardens represented a “mountain retreat within reach,” providing the literati with a utopian sanctuary for reflection and the cultivation of inner peace after their withdrawal from official life. Importantly, the prosperity brought by the canal transformed this ideal into a physical reality. The gardens were not merely landscaped spaces; they functioned as three-dimensional compositions—livable works of art that hosted poetic gatherings, calligraphy, painting, and theatrical performances, thereby serving as arenas for both social interaction and cultural production. Therefore, their emergence and flourishing were direct outcomes of the economic prosperity and cultural vitality fostered by the Grand Canal (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Canal-Related Cultural Architectural Complexes (Government Offices, Gardens) and Their Symbiotic Relationship with Urban Waterways, (a) Tiger Hill Pagoda, (b) Master-of-Nets Garden, (c) the Two Towers of Arhats, (d) Panmen Scenic Area, (e) Lingering Garden, (f) Baodai Bridge. (Source: author).

Within the architectural complexes associated with the canal, the canal administrative offices and classical gardens illustrate the dual dimensions of Suzhou prosperity shaped by its waterways. On the one hand, government offices embodied the public, orderly, and authoritative character of the canal city, functioning as key nodes of imperial governance and urban management. On the other hand, classical gardens reflected the private, aesthetic, and spiritual dimensions of urban life, providing sanctuaries for the literati and cultural elites. Together, these two typologies composed a comprehensive portrait of Suzhou as a canal metropolis distinguished by administrative efficiency, economic vitality, and profound cultural sophistication.

- 2.

- Cognitive Narratives: Advanced Decoding of Cultural Symbols

The evolution of spatial cognition reflects a fundamental shift in society’s understanding of the value and meaning of these two architectural typologies.

Government offices and administrative bureaus were regarded by citizens as the absolute centers of authority, order, and public governance. Their monumental spatial configurations inherently evoked feelings of reverence and submission. Functionally, these institutions represented the enforcement of imperial laws and the administrative apparatus encountered by citizens in matters of litigation, taxation, and regulation. At the core of this perception was their role as vessels of centralized power. In contrast, today, with their administrative functions entirely extinguished, these former official sites have been reinterpreted as open-air museums and educational spaces showcasing the culture of ancient governance. People no longer perceive them as active seats of authority but as spatial representations of historical urban operations and bureaucratic systems. Consequently, they have transitioned from awe-inspiring centers of power to heritage sites of study, reflection, and public engagement.

Classical gardens were perceived as exclusive and deeply private spaces. They functioned as spiritual retreats where owners and their intellectual circles convened for poetry recitals, calligraphy, painting, and philosophical discourse, cultivating a highly personalized artistic world detached from the secular realm. Appreciating such spaces required cultural literacy and aesthetic sensitivity, as visitors needed to interpret the metaphors embedded in rocks, couplets, and inscriptions—an act comparable to decoding a symbolic language. In the contemporary era, particularly following their inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List, the perception of gardens has undergone a profound transformation. Once private retreats of the elite, they have become shared aesthetic sanctuaries and cultural heritage sites open to the public. Visitors now engage with these spaces not only as masterpieces of landscape art but also as embodiments of universal aesthetic values and craftsmanship recognized by UNESCO. Accordingly, modes of appreciation have shifted from the intimate “shared understanding” of a select few to broader forms of “aesthetic learning” and “cultural experience” accessible to all.

- 3.

- Existence Narrative: Distinctive Culture and Urban Context

The cultural complexes associated with the canal—Suzhou government offices and classical gardens—are not merely passive “containers” of intangible culture. Rather, they constitute dynamic cultural gene fields that have emerged from Suzhou distinctive urban fabric. The spatial structure, morphological characteristics, and environmental qualities of these complexes fundamentally shape the formation, expression, and transmission of the intangible cultural practices they embody. Collectively, they constitute a dual-structured cultural system within the urban context, functioning as the core foundation of Suzhou cultural identity and continuity.

The spatial narrative of Suzhou government offices must be interpreted within the broader context of the city’s role as a major hub of the Grand Canal and the administrative center of the Jiangnan region. Their carefully aligned spatial axes and hierarchically organized courtyard layouts are more than architectural configurations; they represent the material manifestation of the imperial bureaucratic system and Confucian ritual order. As a crucial node in the grain transport network, Suzhou government complexes—particularly specialized institutions such as the Grain Transport Bureau and the Textile Manufactory—were designed with spatial logics that directly supported logistics management, taxation, and administrative operations. Each threshold and courtyard serves as a three-dimensional chronicle of governance practices and the spatial encoding of institutional culture. Collectively, these spaces exemplify a highly rationalized and systematically organized civilization of canal governance.

The spatial narrative of classical gardens is deeply rooted in the cultural milieu of Suzhou literati, who embraced a life philosophy balancing official duty and reclusion, underpinned by a refined civic aesthetic culture. The design principles of “finding the grand within the small” and “winding paths leading to secluded beauty” are not simply horticultural techniques but spatial articulations of the literati’s worldview and existential sensibilities. Amidst Suzhou commercial prosperity and material affluence, this social class cultivated a distinctive paradigm: the pursuit of mountain-like serenity within the vibrancy of the city. Accordingly, the gardens were not spaces of withdrawal but carefully constructed mental landscapes intended to nurture both inner tranquility and artistic creativity. Cultural activities such as poetry gatherings, painting exhibitions, and guqin performances held within these settings exemplify the living transmission of the refined lifestyle characteristic of Suzhou literati and the broader Jiangnan region.

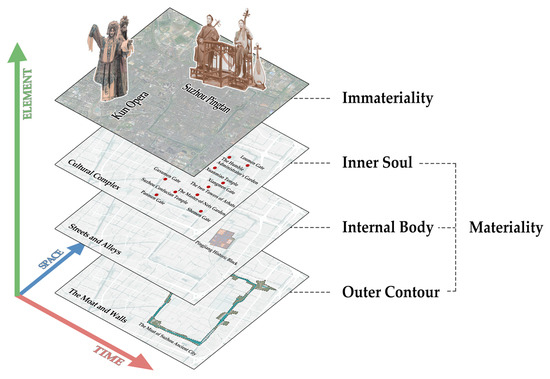

3.3. Summary of Narrative Characteristics in Historic Urban Spaces

The spatial narrative of Suzhou ancient city unfolds as an epic chronicle shaped by the symbiotic relationship between land and water, with the Grand Canal serving as its dynamic axis and organizing framework. Through deliberate functional differentiation and adaptive evolution across successive historical periods, this narrative has gradually accumulated into a layered cultural epic [49,50,51,52]. From a historical perspective, Suzhou has transformed from a “canal hub” to a “cultural heritage city,” reflecting the transition from economic utility to cultural symbolism. Spatially, the city has evolved from a pattern of “dualistic coexistence” between land and water to an integrated urban image that harmonizes natural and built environments. Accordingly, its physical spaces function as vessels for cultural memory, continuously activating, transmitting, and renewing the city diverse cultural identities.

The moat has evolved from a military boundary into an urban interface, while the historic districts have sustained the rhythms of daily life through interconnected pathways and nodes. Government offices and classical gardens, in turn, embody distinct spatial narratives of institutional order and spiritual expression. Collectively, these three elements constitute a coherent cognitive framework for understanding Suzhou ancient city—extending from its external form (the moat) to its internal fabric (streets and alleys) and its metaphysical essence (gardens) (Figure 7). Grounded in Suzhou distinctive dual grid pattern of land and water, this framework addresses three fundamental questions of spatial cognition: Where is the city? How does the city live? Why is the city poetic?

Figure 7.

An overlap analysis of the city maps from different periods. (Source: author).

The symbiosis of land and water represents not merely a physical form but the foundational paradigm of Suzhou spatial organization. Waterways facilitate transportation and commerce, whereas land supports everyday living and habitation, together constituting a complementary system that defines the city functional distribution. The north–south commercial axis of the Grand Canal intersects with the east–west residential axis at nodes such as Changmen, generating vibrant mixed-use zones that integrate trade, residence, and cultural exchange. This multilayered and interconnected cognitive framework encapsulates the essence of Suzhou spatial narrative, revealing its most profound and distinctive urban character.

4. Discussion

After conducting a historical spatial narrative analysis of Suzhou’s urban landscape and distilling the core narrative characteristics of the canal city as a representative historical urban typology, we proceed to construct a framework for historical urban spatial narratives [53,54,55,56]. This framework synthesizes the preceding discussion and demonstrates that historical spatial narrative is not only a methodological tool for interpreting cultural heritage but also a sustainable and critically informed approach for guiding contemporary heritage practice [57].

The three-dimensional narrative framework we have constructed—historical time–space, spatial cognition, and existential experience—derives its strength from a multifaceted understanding of spatial attributes and the innovative adaptation of narrative theory. It is not a mere juxtaposition of independent perspectives but a coherent theoretical model with rigorous internal logic. By applying this enriched three-dimensional framework, we can offer a more nuanced reinterpretation of the narrative characteristics previously identified in canal cities (Figure 8):

Figure 8.

Schematic Diagram of the Logical Framework for Narrating Historical Urban Spaces. (Source: author).

Narrative Shift from Logistics to Cultural Flow: This process reflects not only an economic transition but also a fundamental reconstruction of urban narrative meaning. Historically and temporally, it appears as the re-functionalization of docks and warehouses; spatially and cognitively, it indicates a shift from the utilitarian viewpoints of merchants and laborers toward the aesthetic and experiential perceptions of tourists and residents; existentially, it entails transforming former trade-oriented settings into cultural narratives activated through festivals, exhibitions, and immersive performances.

Strip–Cluster Structure: This structure represents the material embodiment of three interwoven narrative dimensions. Historically and spatially, it reflects the spatial logic of canal-based transport economies. In terms of spatial cognition, the linear corridor operates as a directional and efficiency-oriented cognitive axis, while the clusters serve as experiential nodes that support exploration, pause, and immersion. Within the existential narrative, the linear corridor accommodates continuous and processional cultural practices (such as parades and relay activities), whereas the clusters host concentrated and symbolically significant events (including markets and rituals).

The Symbiosis of Practicality and Idealism: This cultural core constitutes the fundamental source of spatial narrative tension. Government offices and classical gardens represent two contrasting narrative modes: the former conveys a strong narrative, in which spatial organization is tightly aligned with a single logic of governance and authority; the latter conveys a weak narrative, characterized by spatial openness that accommodates multiple, individualized interpretations and experiential meanings. The ingenuity of canal cities lies in their capacity to integrate these divergent narratives within a unified urban system through functional zoning (such as commercial quarters and residential neighborhoods) and spatial transitions (such as alleys that guide movement from bustling markets to secluded gardens) [58]. As a result, these narratives coexist and enter into productive dialogue, rather than negating one another.

From Organic Growth to Symbolic Extraction: This shift reveals the core logic of contemporary heritage practice, namely the governance and construction of narratives. When picturesque scenes of bridges, waterways, and dwellings are abstracted from everyday life and transformed into urban symbols, the process becomes a deliberate project of shaping spatial cognitive narratives. Through tourism promotion, cultural programming, and urban design, heritage discourse actively orients public perception and experience toward a particular interpretive framework that aligns with designated heritage values. While this constitutes a necessary articulation of cultural significance, it also entails the risk of reducing complex historical processes into oversimplified stereotypes.

The construction of this framework ultimately seeks to critically reassess mainstream heritage conservation paradigms and to advance new possibilities for more adaptive and culturally informed approaches.

- Challenging the Dogma of Authenticity: Within the World Heritage system, the principle of authenticity is often constrained by debates centered on material fabric and original form. Our three-dimensional framework advances a more holistic and operational understanding of authenticity, encompassing historical-layered authenticity, experiential–cognitive authenticity, and existential–practical authenticity. Under this expanded perspective, a restored wharf attains dynamic and multidimensional authenticity—rather than relying solely on material originality—when it preserves its historical hydrological context (historical dimension), facilitates comprehension of its former operational functions (cognitive dimension), and supports contemporary communal or celebratory uses (existential dimension).

- From Protected Objects to Relational Networks: Traditional conservation practices have typically emphasized discrete elements, such as individual buildings or designated historic districts. However, a spatial narrative framework urges a shift toward understanding the city as a network of interdependent narrative relationships. Accordingly, the focus of preservation transitions from safeguarding isolated components to maintaining and reconstructing critical relational pathways that sustain urban meaning. For example, preserving the visual and processional connection between Guanqian Street and Xuanmiao Temple reinforces their cognitive narrative function, while restoring the service-oriented and social interactions between the canal and adjacent teahouses revitalizes their existential narrative role.

- From Expert Empowerment to Collaborative Storytelling: Spatial cognitive narratives underscore multi-subject participation, thereby challenging the traditional expert-centered paradigm in heritage practice. Accordingly, future preservation should evolve into a co-creative narrative process. Through oral history, participatory design, and community-based cultural activities, the memories of long-term residents, the experiences of immigrants, and the creativity of younger generations can be collectively incorporated into the unfolding narrative of urban space. As a result, heritage becomes an inclusive and continuously evolving assemblage of stories, rather than a closed historical text defined solely by institutional authority.

The case of Suzhou’s historic urban landscape, characterized by the coexistence of land and water, demonstrates that the strength of spatial narrative lies in its complexity, stratification, and inherent dialogic qualities. It conveys the grand historical narrative of imperial grain transport as well as the subtle rhythms of everyday life unfolding within its alleys and lanes. It also embodies the philosophical aesthetics of the literati, while simultaneously generating new narrative layers through contemporary cultural–tourism integration in the digital era. Accordingly, the three-dimensional framework proposed in this study is intended to interpret, preserve, and dynamically extend these multifaceted narratives.

Therefore, the core contribution of historical urban spatial narrative research lies in reframing heritage conservation from a primarily technical and engineering-oriented practice to a cultural and urban design paradigm centered on meaning interpretation, identity formation, and future-oriented spatial imagination. Accordingly, this perspective underscores that decisions in urban renewal extend beyond physical interventions; they involve deliberate choices about which histories to inherit, which contemporary conditions to sustain, and which futures to articulate for the city.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

Architectural culture constitutes a city’s fundamental asset, enabling it to transcend spatial uniformity and sustain its distinctive cultural heritage. Spatial narrative methodologies integrate intangible cultural meanings into tangible spatial carriers, transforming historical buildings and urban layouts from static entities into living places imbued with collective memory and emotional resonance. Through systematic interpretation and contextual articulation, this approach not only safeguards the cultural soul of a city but also converts heritage resources into drivers of civic identity and cultural competitiveness, laying a resilient foundation for future development.

The deeper significance of spatial narrative lies in its paradigm shift—from static preservation to dynamic, collaborative renewal. Rather than advocating historical stagnation, it emphasizes an intelligent dialogue between the old and the new, grounded in an understanding of a site’s intrinsic narrative logic. As exemplified by Suzhou moat, which evolved from a defensive boundary into a living urban interface, this paradigm fosters new urban chapters aligned with contemporary life while preserving the essential narrative of connection. Consequently, heritage is liberated from the notion of being a constraint on development and redefined as a source of inspiration that fuels innovation, cultivates distinctive spaces, and reinforces civic belonging—thereby realizing the living transmission of culture.

Looking ahead, spatial narrative theory provides a human-centered framework for sustainable urban conservation. It advocates inclusive participation, empowering communities and the public to serve as co-narrators of their shared heritage. By integrating digital technologies such as VR/AR and digital twins, new narrative dimensions are created through immersive experiences that revitalize cultural expression in the digital age. Ultimately, this approach establishes a living and adaptive pathway in which essential cultural genes are precisely identified and preserved while innovative forms of expression are encouraged. In safeguarding core values and fostering creative renewal, spatial narratives achieve the long-term integration of cultural, social, and economic sustainability.

5.2. Research Limitations

Existing spatial narratives have predominantly emphasized grand historical events, official governance practices, and elite literati culture—represented by garden owners, scholars, and landscape artists—thereby constructing a predominantly top-down interpretive framework. However, such emphasis on macro-historical and elite perspectives, coupled with a static understanding of authenticity, may obscure the organic evolution of heritage within contemporary society. While we frequently describe the dual chessboard pattern of land and water, the everyday lives, emotions, and experiences of ordinary residents along riverfront neighborhoods often remain underrepresented. As a result, the spatial narrative risks becoming less multidimensional, diminishing its capacity to reflect the full social complexity and lived reality of historic urban spaces.

5.3. Recommendations and Future Works

1. Narrative Shift—From Grand Narratives to Microhistories and Plural Voices: The future of spatial narrative research calls for a paradigm shift from dominant, elite-centered grand narratives toward microhistorically and plural narratives that capture diverse perspectives and lived experiences.

Action Path—Towards Inclusive Narrative Practices: Through the integration of oral histories, community-based participatory mapping, and grassroots archival research, this approach actively seeks to uncover and document the “voices of silence” often overlooked in conventional heritage discourse. It aims to construct a multi-layered corpus of spatial stories encompassing officials, literati, residents, merchants, and artisans. Accordingly, future narratives of Pingjiang Road should extend beyond the renowned scholar Gu Jiegang to include the everyday stories of ordinary families, such as the Wangs living within its narrow alleys, thereby restoring the authenticity and social inclusiveness of urban heritage narratives.

2. Paradigm Evolution—From Frozen Preservation to Dynamic Adaptive Management: The contemporary conservation paradigm has shifted from static [59,60,61], object-centered preservation toward dynamic and adaptive management that recognizes the evolving nature of heritage within its social and spatial contexts.

Action Path—Toward Integrated and People-Centered Conservation: This approach advocates the incorporation of cultural landscape and living heritage management concepts, emphasizing the stratified character of heritage. Contemporary interventions, renovations, and uses are understood as new layers within the ongoing historical continuum. When evaluating conservation strategies, it is therefore essential to prioritize not only the preservation of physical form but also the maintenance of community vitality and the continuity of cultural practices. Ultimately, this framework re-centers people and their everyday social practices within spatial narratives, ensuring that heritage remains a living, evolving component of urban life.

3. Methodological Innovation—Digital Empowerment: This approach employs VR/AR and digital twin technologies not only to reconstruct the visual authenticity of historical environments but also to simulate immersive soundscapes and light atmospheres. By integrating sensor-based monitoring systems that capture real-time environmental dynamics, it enables the creation of a perceptible, interactive, and continuously evolving digital narrative of spatial experience. Such digitally enhanced narratives extend the boundaries of spatial perception, allowing heritage spaces to be experienced, interpreted, and managed in more dynamic and participatory ways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.; methodology, C.S.; investigation, C.S., J.F. and R.Y.; resources, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.; writing—review and editing, C.S., J.F. and R.Y.; visualization, J.F. and R.Y.; supervision, C.S.; project administration, C.S.; funding acquisition, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Philosophy and Social Sciences Research General Project Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China, NO. 21LSC007; and the Hui-Chun Chin and Tsung-Dao Lee Chinese Undergraduate Research Endowment.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Diao, J.; Lu, S. A narrative-led approach for the revitalization of places of memory: A case study of Haiyan moat waterfront (Zhejiang, China). Urban Des. Int. 2024, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, A.; Tonnelat, S. Urban poetic narratives along the Seine: Everyday practices and collective memory. City Community 2012, 11, 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan, R. Tales of the City: A Study of Narrative and Urban Life; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, G. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method; Lewin, J.E., Translator; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory; Coser, L.A., Ed. and Translator; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, D. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- White, H. The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.-L.; Foote, K.; Azaryahu, M. Narrating Space/Spatializing Narrative: Where Narrative Theory and Geography Meet; The Ohio State University Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Calvino, M.; Cutini, V. Space syntax and urban heritage: The case of Siena’s historic core. J. Space Syntax 2015, 6, 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, N.; Zhang, J. Revitalizing Beijing hutongs: Spatial narrative and everyday life. J. Urban Des. 2021, 26, 1025–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Psarra, S. Architecture and Narrative: The Construction of Space and Cultural Meaning; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y. Research on Urban Marathon Path from the Perspective of Spatial Narrative Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Long, D.Y. Spatial Narratology: A New Field in Narratology Studies. J. Tianjin Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2008, 6, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.Y. Domestic Research and Reflection on Spatial Narrative. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2009, 1, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A. On the Development of Spatial Narratology. Soc. Sci. 2008, 1, 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Research on Contemporary Chinese Fiction in the “Spatial Turn”. Master’s Thesis, Soochow University, Suzhou, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y.Y. A Narrative Study of Urban Historical Landscapes. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.Z.; Ma, X. Quantitative Research on the Narrative Environmental System of Historic Urban Districts. South Archit. 2013, 2, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.H.; Tang, Y.Q. Evolution of Contemporary “Spatial Narrative” Theories: Cognitive Shifts and Practices of Space in Narratology. Guangxi Soc. Sci. 2021, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- King, R. The Story of the City: Urban Tales and the Built Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. The Theoretical Lineage of Spatial Narrative Design and Its Contemporary Value. Cult. Stud. 2020, 4, 158–181. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. Place-narratives: A New Mode for the Construction of the Connotation and Characteristics of Urban Culture. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2012, 20, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The World Heritage List. The Grand Canal. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1443 (accessed on 7 October 2025).