Abstract

This study examines urban–water synergy as the spatial coordination between urban expansion and water systems. Using land-use data from 2000 to 2020, the central urban areas of Jingzhou and Anqing are analyzed as representative small and medium-sized cities. Urban–water synergy is assessed across three dimensions: land-use synergy, pathway synergy, and directional synergy. These dimensions are quantified using four indicators: Urban–Water Interaction Intensity (UWII), Urban–Water Interaction Displacement (UWID), Spatial Path Alignment Distance (SPAD), and Directional Alignment Angle (DAA). The results show that Jingzhou and Anqing exhibit two distinct urban–water synergy modes: a convergent interaction mode characterized by increasing alignment in land-use interactions, spatial pathways, and directional tendencies, and a divergent synergy mode characterized by persistent separation across these dimensions. Differences between these synergy modes are associated with expansion pressure, physical template, and institutional mechanisms. Spearman rank correlation and principal component analysis suggest that institutional mechanisms constitute an independent analytical dimension and may be relevant for interpreting potential non-linear changes in urban–water interaction patterns. Based on these findings, this study discusses governance implications centered on institutional effectiveness, supported by spatial restoration and expansion regulation, for informing urban–water synergy governance in small and medium-sized cities.

1. Introduction

With ongoing urbanization, contradictions between urban expansion and the preservation of natural water systems have become increasingly prominent. As vital ecosystem components, water bodies provide essential functions such as flood control and water retention, as well as ecological benefits like climate regulation and landscape shaping [1]. However, under the pressure of urban land expansion, water bodies are frequently encroached upon and fragmented, undermining their spatial continuity and ecological functions, thereby compromising regional ecological security and spatial structural stability [2,3].

At the conceptual and analytical perspective level, existing studies have largely examined water bodies within broader urban environmental or governance frameworks, with research attention primarily directed toward water management, water environment protection, and related regulatory issues. In this line of research, water bodies are commonly analyzed with respect to water supply security, wastewater and stormwater management, flood risk control, and water quality regulation [4,5,6,7], often emphasizing how planning regulations, infrastructure systems, and governance arrangements respond to water-related pressures associated with urban growth. Within this predominantly city-centered perspective, urban systems are typically treated as the primary analytical focus, while water bodies tend to be framed as managed or regulated elements within urban development processes. As a result, studies that explicitly place cities and water bodies as co-evolving and relatively equivalent systems—and systematically examine their spatial evolution and interactive dynamics—remain comparatively limited.

At the methodological level, current research on the relationship between cities and water systems primarily focuses on urban land-use change, the evolution of water landscapes, and their interactions [8,9,10,11]. One line of research examines urban expansion and its disruptive effects on water structures, particularly highlighting the correlations among land-use transitions, reductions in water surface area, and increased landscape fragmentation [12,13,14]. Another line analyzes how the configuration of water systems—through ecological corridors or hydrological networks—exerts reciprocal influences on urban spatial morphology [15,16]. In recent years, some scholars have begun to emphasize the interactivity and harmony of urban–water relationships [17]. These approaches are effective in reflecting local changes in either urban or water systems; however, they still exhibit certain limitations in directly characterizing the interactive relationships and the degree of coordination between cities and water bodies, making it difficult to systematically reveal their coupled and interactive behaviors during spatial evolution.

At the governance and application level, existing studies have discussed a range of planning and management responses to urban–water challenges, including regulatory frameworks, spatial control measures, and ecological restoration approaches. In particular, prior research has focused on the design of policy instruments, planning regulations, and project-based interventions aimed at mitigating water-related risks, improving environmental performance, or enhancing urban water management capacity under conditions of urban growth [18,19,20,21]. However, relatively few studies have further examined how insights derived from mechanism analysis can be used to identify and organize governance priorities and intervention logics. As a result, the relative importance of key driving factors underlying urban–water coordination often remains unclear and has not been sufficiently identified through systematic analysis.

In response to these research gaps, this study explores the intrinsic relationships and driving mechanisms between urban expansion and the evolution of water system patterns from the perspective of dynamic interaction and systemic coupling [22]. Building upon this, the concept of urban–water synergy is introduced as a conceptual and analytical perspective to support the coordinated coexistence of urban and water systems. Urban–water synergy refers to the coordinated coexistence of urban and water systems as reflected in their spatial interaction patterns and spatial configuration [23]. In this study, urban–water synergy is defined as the spatial coordination between urban expansion and water systems, reflected in how the two systems interact, organize, and orient in space over time. Rather than treating spatial interaction as a single process, this study conceptualizes it as a multi-dimensional spatial relationship that operates at different levels. The land-use dimension captures spatial interaction in its most direct form through land conversion between urban land and water bodies, representing spatial competition or adjustment [24]. The pathway dimension captures spatial interaction at the level of spatial organization by examining whether urban expansion follows, responds to, or departs from the evolving spatial structure of water systems [25]. The directional dimension further captures spatial interaction in terms of dominant expansion orientation, indicating whether urban growth is aligned with or diverges from water-system evolution [26]. Together, these three dimensions represent complementary aspects of urban–water spatial interaction—direct occupation, spatial organization, and expansion orientation—thereby providing a coherent operational framework for analyzing urban–water synergy as a form of spatial coordination.

The primary objectives of this study are threefold: (1) to adopt a system-equivalent perspective that treats cities and water bodies as interacting systems, and to characterize their spatial interactions during urban expansion in order to reveal the patterns of urban–water synergistic evolution; (2) to develop a multidimensional indicator system capable of capturing the interaction processes and the configurations of urban–water synergy between urban and water systems; and (3) to clarify the relative importance of key driving mechanisms underlying urban–water synergy evolution and, on this basis, to discuss governance priorities and intervention logics that can inform spatial decision-making for urban–water synergistic governance.

This study focuses on small and medium-sized cities. Compared with large cities, there are relatively fewer studies on urban–water relationships focusing on small and medium-sized cities. According to the Northam curve [27], many of these cities are in early or accelerated stages of urban expansion, where rapid spatial growth outpaces water governance, making urban–water conflicts more visible. As these cities remain in critical adjustment phases rather than mature development stages, urban–water synergy research is particularly relevant for contemporary planning practice. Accordingly, this study selects Jingzhou and Anqing as representative small and medium-sized cities to examine urban–water synergy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

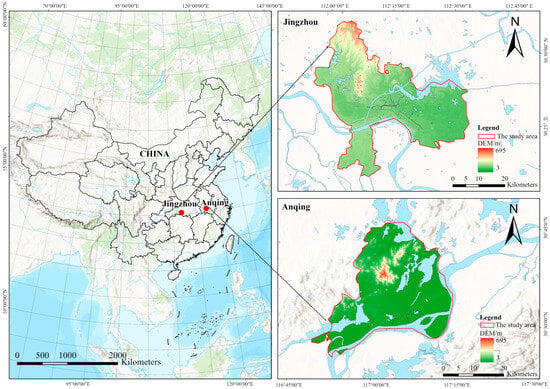

This study takes the central urban area of Jingzhou City in Hubei Province, China, as the core research region and selects the central urban area of Anqing City in Anhui Province, China, for comparative analysis. Jingzhou is located in the Jianghan Plain in the south-central part of Hubei Province, with its main urban area consisting of Shashi District and Jingzhou District. The city extends along the Yangtze River, displaying a typical “river-flanked” spatial layout. Anqing is situated in the southwestern part of Anhui Province, with its main urban area comprising Yingjiang District, Daguan District, and Yixiu District. The city exhibits a distinct riverside development pattern, with an overall expansion trend characterized by water-oriented spatial agglomeration (Figure 1). Both are key prefecture-level cities within their respective provinces. Their central urban areas concentrate significant administrative, economic, and residential functions, making them representative and comparable cases at the scale of small and medium-sized cities [28].

Figure 1.

Overview Map of the Study Area.

The central urban area of Jingzhou has a relatively dense water network, with the Yangtze River running through it and serving as the primary backbone. Within the city are Chang Lake and Meizi Lake, as well as rivers and artificial waterways such as the Ju-Zhang River and the Yangtze-to-Han Canal [29], which together form a complex water network shaped by natural configuration and significant human intervention. Similarly, Anqing’s main urban area centers around the main stream of the Yangtze River, complemented by small and medium rivers, lakes, and canal systems, collectively presenting an overall pattern of linear expansion along the Yangtze River and the localized aggregation of water bodies in certain zones [30].

Anqing City was selected as the comparative counterpart to Jingzhou based on the following considerations. First, both cities are located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, sharing similar climatic conditions and hydrological structures, which provide a comparable natural background for contrastive analysis. Second, they are equivalent in administrative hierarchy and urban scale. Each represents a small or medium-sized prefecture-level city, carrying comprehensive administrative, economic, and residential functions in the core urban areas [31]. Third, both cities exhibit river-oriented layouts and waterfront development patterns, making their spatial structures broadly comparable. Fourth, the two cities exhibit distinct spatial evolutionary patterns in urban expansion and water system development, facilitating comparative studies of their diversified urban–water synergy mechanisms. Finally, there are significant differences in governance policies and regulatory frameworks between the two cities, offering a practical basis for institutional-level comparative analysis. By constructing a “stable–dynamic” sample pair, this study aims to identify the shared mechanisms and divergent pathways in urban–water synergy, thereby improving the specificity and practical explanatory power of the analysis.

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

This study uses land-use data from the main urban areas of Jingzhou and Anqing for the period of 2000–2020 to construct a multi-period time series, setting 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020 as observation points. The land-use data are sourced from the China Land-Use/Cover Change (CNLUCC) dataset released by the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center (RESDC), Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.resdc.cn/, accessed on 5 November 2024). This dataset is derived from Landsat satellite imagery and generated through manual visual interpretation at a cartographic scale of 1:100,000. The original vector-based land-use data were subsequently rasterized and distributed at a spatial resolution of 30 m for analysis. Digital elevation data were obtained from the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center (RESDC), using the national DEM dataset with a spatial resolution of 90 m (http://www.resdc.cn/, accessed on 5 November 2024), which was used to extract elevation and slope information. Administrative boundary data are sourced from the National Platform for Common Geospatial Information Services (https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/, accessed on 5 November 2024). Hydrographic data of rivers, lakes and canals are extracted from the open source platform OpenStreetMap (OSM) via the Geofabrik data service (https://download.geofabrik.de/, accessed on 5 November 2024), which are used to extract the boundaries of major water bodies and support hydrological and ecological process analysis.

Only the CNLUCC raster data were involved in the core analyses, with all operations conducted at a unified spatial resolution of 30 m. DEM data with a resolution of 90 m and vector datasets were excluded from indicator calculations and used solely for locational visualization, spatial positioning, and boundary delineation to ensure spatial consistency. Uncertainties mainly arise from classification errors inherent in manual visual interpretation and minor information loss during raster–vector conversion; given the city-scale focus of this study, their impacts on overall conclusions are limited.

Land-use data were clipped and preprocessed using ArcGIS 10.8 to generate land-use maps at a resolution of 30 m, consistent with the native resolution of Landsat imagery and commonly applied in city-scale land-use analyses. The CNLUCC dataset adopts a two-level classification system, including six primary land-use types and 25 secondary subclasses. This study relies on the primary classification (Table 1), selecting construction land and water bodies as analytical objects representing urban space and water systems, respectively, while other land-use types are retained as background categories and excluded from indicator calculations.

Table 1.

Primary Land Use Classification in CNLUCC.

2.3. Research Framework

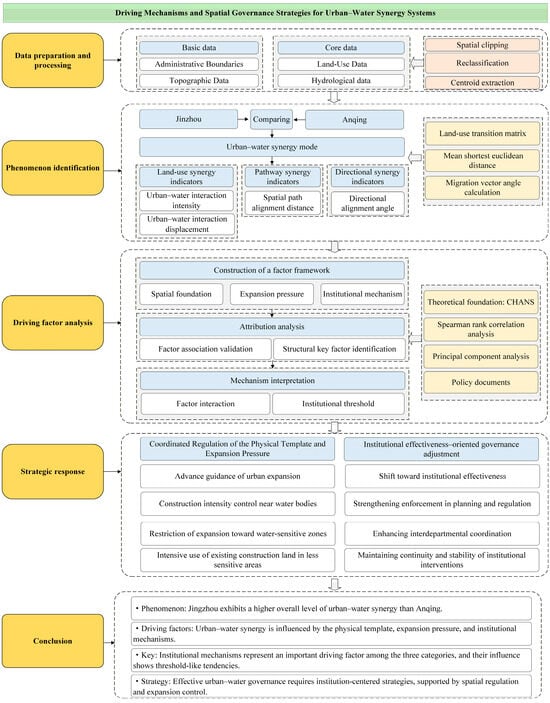

This study adopts urban–water synergy as its core analytical concept and constructs a staged research framework to organize the overall analysis process, including data preparation and preprocessing, phenomenon identification, driving factor analysis, and strategy response (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Framework of the Study.

In the first stage, multi-temporal land-use data for the central urban areas of Jingzhou and Anqing from 2000 to 2020 are collected and preprocessed to establish a consistent spatial and temporal data foundation, thereby supporting subsequent urban–water synergy analysis [32,33].

The second stage focuses on phenomenon identification. A three-dimensional urban–water synergy framework is constructed, consisting of land-use synergy, pathway synergy, and directional synergy. This stage identifies the spatial interaction patterns and evolutionary trajectories of urban–water synergy and compares the synergy patterns between Jingzhou and Anqing to reveal their differences [34,35].

In the third stage, driving factor analysis is conducted to examine how the identified urban–water synergy differences are related to underlying drivers. Three categories of driving factors—expansion pressure, physical template, and institutional mechanisms—are introduced. Spearman’s rank correlation is used to test whether these driving factors are statistically associated with the three dimensions of urban–water synergy, while principal component analysis is applied to identify the key factor within the driving-factor system [36].

In the final stage, strategy-related implications are discussed based on the research findings. The coupled effects of multiple driving factors and the threshold characteristics of the key factors are examined, and corresponding governance considerations are outlined accordingly.

2.4. Research Methodology

2.4.1. Land-Use Transition Matrix

The land-use transition matrix is employed to quantify the conversions among different land-use types across multiple time periods [37]. In this study, four-stage transition matrices are constructed to reflect the dynamic conversions between urban land and water bodies in the central urban areas of Jingzhou and Anqing during 2000–2020 [38]. The general form of the matrix is as follows:

where tij denotes the area converted from land-use type i to type j, and n is the number of land-use types. Diagonal elements represent areas that remain unchanged, whereas off-diagonal elements represent land converted between urban land and water bodies. These conversion elements provide the quantitative basis for calculating the intensity and displacement of urban–water land-use interactions in subsequent analyses.

2.4.2. Land-Use Interaction Metrics

Two indicators are established to characterize the conversion between urban land and water bodies: Urban–Water Interaction Intensity (UWII) and Urban–Water Interaction Displacement (UWID), which, respectively, quantify the intensity and directional tendency of land-use changes, with their formulas given by:

where represents the area converted from water bodies to urban land (km2), denotes the area converted from urban land to water bodies (km2), and refers to the total area of the study region (km2).

UWII (0–1) measures the overall intensity of land conversion between urban land and water bodies, with higher values indicating more frequent conversion. UWID (−1–1) measures the dominant conversion displacement: positive values indicate urban expansion into water bodies, while negative values indicate water restoration. Values of UWID close to zero indicate relatively balanced interaction. The two indicators are therefore interpreted jointly to characterize different land-use synergy states, as summarized in Table A1.

2.4.3. Spatial Path Alignment Distance

The Spatial Path Alignment Distance (SPAD) is used to quantify the spatial alignment between the centroid migration trajectories of urban land and water bodies over time [39]. It is calculated based on centroid coordinates extracted at multiple time points, as the mean bidirectional minimum Euclidean distance between the two trajectories, and is expressed in degrees (°) [40]. The formula is as follows:

where and are the centroid nodes on the migration trajectories of urban land and water bodies, respectively; and are the polylines of the migration trajectories; denotes the Euclidean distance from point a on one migration trajectory to the nearest point b on the other migration trajectory, and n is the number of centroid nodes.

A smaller SPAD value indicates a closer spatial alignment between the centroid migration trajectories of urban land and water bodies; conversely, a larger SPAD value indicates greater spatial separation between the two trajectories.

2.4.4. Directional Alignment Angle

The Directional Alignment Angle (DAA) quantifies the directional relationship between the centroid displacement vectors of urban land and water bodies across consecutive time intervals [39]. It is calculated as the angle between the two displacement vectors and is expressed in degrees (°). The formula is as follows:

where and represent the centroid displacement vectors of urban land and water bodies in period t, respectively; “·” denotes the dot product; and is the vector magnitude. The resulting DAA value ranges from 0° to 180°.

A smaller DAA value indicates a smaller angular difference between the centroid displacement directions of urban land and water bodies; conversely, a larger DAA value indicates greater directional divergence between the two displacement vectors.

2.4.5. Structural Continuity Assessment Using COHESION

To address the potential uncertainty introduced by centroid-based indicators, this study further incorporates the Patch Cohesion Index (COHESION) to assess the structural continuity of urban built-up land and water bodies [2]. COHESION measures the physical connectedness of patches belonging to the same class at the landscape level and reflects whether a spatial system remains coherent rather than fragmented. The COHESION is calculated as:

where Pij is the perimeter of patch j of class i, Aij is the area of patch j of class i, and A is the total landscape area. The index ranges from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating stronger physical connectedness and higher structural continuity of the corresponding spatial system.

In this study, COHESION is employed as a supplementary structural indicator to evaluate whether urban and water systems maintain overall spatial integrity during the study period. Rather than capturing fine-scale internal morphological variations, COHESION is used to examine whether the systems exhibit signs of system-level spatial fragmentation. This assessment provides a structural context for interpreting centroid-based indicators and helps contextualize the use of SPAD and DAA in capturing macro-scale pathway and directional tendencies.

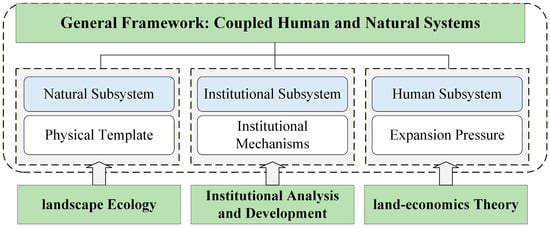

2.4.6. Construction of the Driving-Factor Framework

Drawing on the Coupled Human and Natural Systems (CHANS) framework proposed by Liu et al. [24], which conceptualizes urban systems as the coupling of natural, human, and institutional subsystems, this study organizes the driving factors of urban–water synergy into three analytical dimensions: physical template, expansion pressure, and institutional mechanisms. These dimensions correspond to the natural, human, and institutional subsystems in CHANS and are grounded in established disciplinary theories to form an integrated analytical structure (Figure 3). The physical template dimension is grounded in landscape ecology and is represented by changes in water area, reflecting variations in water-body scale [41]. The expansion pressure dimension draws on urban land-economics theory and is quantified using changes in built-up land area, capturing the scale and pace of urban spatial expansion [42]. The institutional mechanism dimension is informed by Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework and is measured using an institutional mechanism score that reflects changes in planning control, ecological policy intervention, and spatial governance capacity over time [25].

Figure 3.

Analytical framework of driving factors in the urban–water system.

To enable quantitative assessment, this study develops a stage-based institutional scoring system (0–5) grounded in the IAD framework and China’s territorial spatial control instruments, including the Blue Line (waterbody protection boundary), Red Line (ecological protection boundary), and urban development boundary [43]. The six levels represent a progressive trajectory of institutional capacity—from the absence of effective regulation to a mature and enforcement-capable system that can influence land-use direction and, in strong cases, reverse land-to-water flows (Table 2). This scoring system is used solely for analytical purposes to quantify institutional change and does not serve as an evaluative ranking of policy performance.

Table 2.

Institutional Capacity Scoring Criteria (0–5).

2.4.7. Spearman Rank Correlation Analysis

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ) is used to quantify the monotonic association between the driving factors and the urban–water synergy indicators [44]. It is calculated based on the ranked differences between paired variables. The formula is as follows:

where represents the rank difference between paired variables, and n denotes the number of observations.

The value of ρ ranges from −1 to 1. A larger absolute value indicates a stronger monotonic relationship, with values approaching 1 signifying a strong positive association, values approaching −1 indicating a strong negative association, and values near 0 suggesting a weak or no monotonic relationship.

2.4.8. Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used to extract the dominant structural components among the driving factors by transforming standardized variables into a set of orthogonal principal components [45]. The calculation is based on the eigen-decomposition of the covariance matrix derived from standardized data. The formula is as follows:

where Z is the standardized data matrix, C denotes the covariance matrix, is the eigenvector representing the loading of each variable on the k-th principal component, and is the corresponding eigenvalue reflecting the amount of variance explained by that component. The proportion of variance explained is given by:

A higher variance ratio indicates a stronger explanatory contribution of that principal component. PCA thus enables the identification of key driving structures and their relative importance.

3. Results

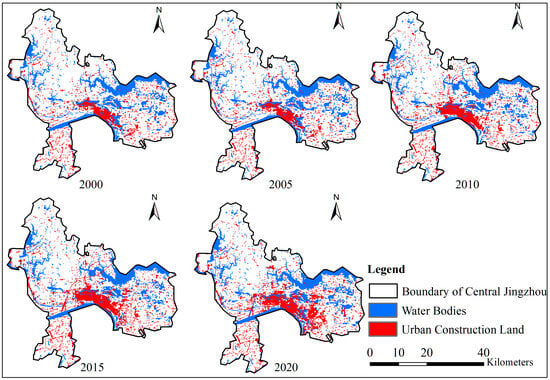

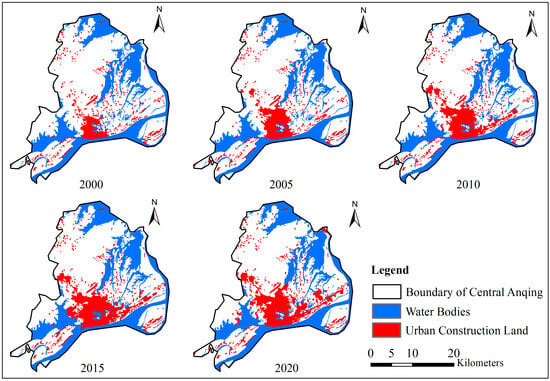

Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the spatial distribution of construction land and water bodies in the main urban areas of the two cities from 2000 to 2020, providing a visual overview of their basic spatial patterns.

Figure 4.

Spatial Distribution of Urban Land and Water Bodies by Time Period in the Main Urban Area of Jingzhou.

Figure 5.

Spatial Distribution of Urban Land and Water Bodies by Time Period in the Main Urban Area of Anqing.

3.1. Urban–Water Land-Use Synergy Evolution Indicators and Comparative Analysis (2000–2020)

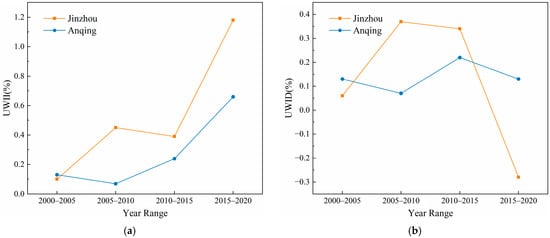

To reveal the evolutionary characteristics of land-use synergy between urban areas and water bodies, a comparative analysis of Jingzhou and Anqing was conducted using two indicators: Urban–Water Interaction Intensity (UWII) and Urban–Water Interaction Displacement (UWID). Land-use transition matrices were constructed for Jingzhou and Anqing across five-year intervals from 2000 to 2020 (Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8 and Table A9). Based on these matrices, UWII and UWID were derived and presented in Table 3 and Figure 6.

Table 3.

Urban–Water Interaction Intensity (UWII) and Interaction Displacement Index (UWID) in the Central Urban Areas of Jingzhou and Anqing, 2000–2020.

Figure 6.

Temporal evolution of urban–water interaction metrics for Jingzhou and Anqing, 2000–2020. (a) Urban–Water Interaction Intensity (UWII); (b) Urban–Water Interaction Displacement (UWID).

In Jingzhou, UWII increased from 0.10% to 0.45% during 2000–2010 (Table 3), slightly declined during 2010–2015 (Figure 6), and then rose sharply to 1.18% in 2015–2020, indicating an overall intensification of land-use conversion between urban land and water bodies. UWID remained positive from 2000 to 2015 and turned negative (−0.28%) during 2015–2020, suggesting a shift in land-use conversion direction from water-to-urban dominance toward urban-to-water conversion. Taken together, these trends indicate a transition in Jingzhou toward a high-intensity, restoration-oriented land-use interaction mode between urban land and water bodies, corresponding to Case II in Table A1.

In Anqing, UWII exhibited an overall increasing trend throughout the study period, indicating a continuous intensification of land-use conversion between urban land and water bodies (Figure 6). However, UWID remained consistently positive, suggesting that land conversion was persistently dominated by the transformation of water bodies into urban land, with no evident reversal. This combination reflects a high-intensity, encroachment-oriented land-use interaction mode between urban land and water bodies, corresponding to Case I in Table A1.

3.2. Urban–Water Pathway Synergy Evolution Indicator and Comparative Analysis (2000–2020)

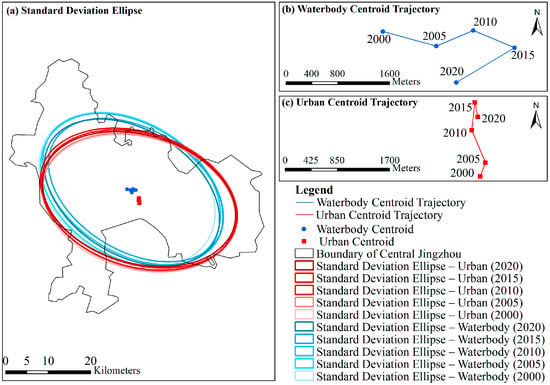

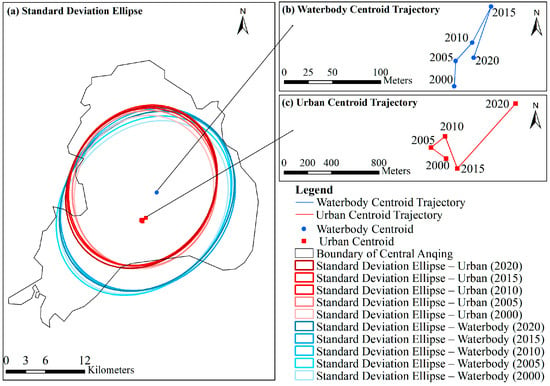

Using the standard deviation ellipse tool, the centroid coordinates of urban and water lands in Jingzhou and Anqing were extracted (Table A10 and Table A11). The centroid coordinates were then used to construct the centroid migration trajectories shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Based on the centroid migration trajectories, the Spatial Path Alignment Distance (SPAD) was calculated (Table 4).

Figure 7.

Centroid migration trajectories and standard deviation ellipses of urban and water bodies in Jingzhou City, 2000–2020.

Figure 8.

Centroid migration trajectories and standard deviation ellipses of urban and water bodies in Anqing City, 2000–2020.

Table 4.

Changes in Directional Alignment Angle (DAA) and Spatial Path Alignment Distance (SPAD) Between Urban and Water Trajectories in Jingzhou and Anqing, 2000–2020.

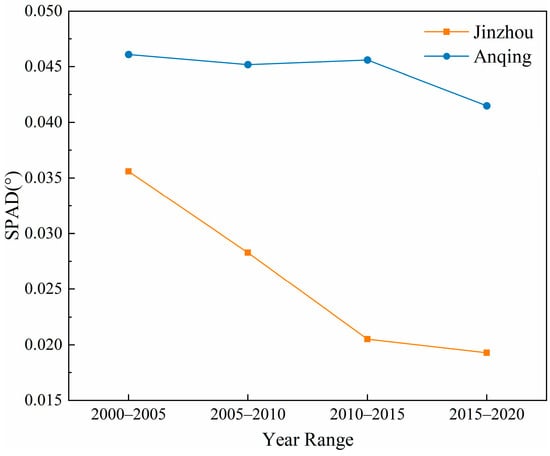

In Jingzhou, SPAD continuously decreased from 0.0356° to 0.0193° during 2000–2020 (Table 4), representing a reduction of more than 45%. The decline was more pronounced between 2000 and 2015 and became moderate after 2015 (Figure 9), indicating a progressive increase in spatial alignment between urban expansion pathways and water body evolution paths, followed by stabilization. Overall, Jingzhou exhibits a pathway interaction pattern with increasing spatial alignment over time.

Figure 9.

Temporal evolution of Spatial Path Alignment Distance (SPAD) between urban and water bodies in Jingzhou and Anqing, 2000–2020.

In Anqing, SPAD showed only a slight downward trend with fluctuations and remained at a relatively high level throughout the study period (Figure 9). This pattern indicates a persistently large spatial separation between urban expansion pathways and water body evolution paths. Accordingly, Anqing exhibits a pathway interaction pattern characterized by sustained separation and relatively weak spatial alignment.

3.3. Urban–Water Directional Synergy Indicators and Comparative Analysis (2000–2020)

Using the standard deviation ellipse tool, the centroid coordinates of urban areas and water bodies in Jingzhou and Anqing were extracted (Table A10 and Table A11). The centroid coordinates were then used to generate the centroid migration trajectories (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Based on the centroid migration trajectories, the Directional Alignment Angle (DAA) was calculated and the results are summarized in Table 4.

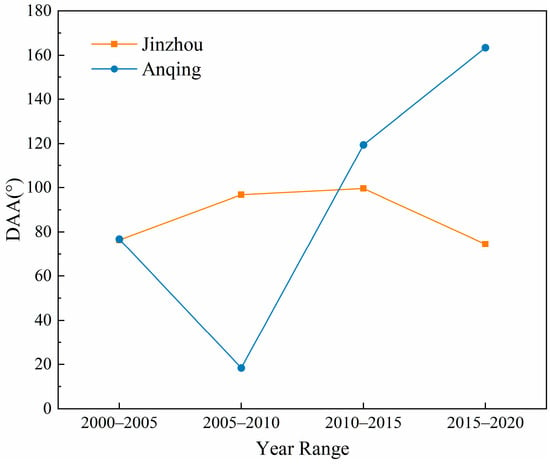

In Jingzhou, DAA increased from 76.32° to 99.56° during 2000–2015 and subsequently declined to 74.44° during 2015–2020 (Table 4), showing a pattern of initial divergence followed by convergence (Figure 10). This trend indicates a decrease in directional difference between urban expansion and water body migration in the later period, corresponding to a shift in their directional relationship.

Figure 10.

Temporal evolution of Directional Alignment Angle (DAA) between urban and water bodies in Jingzhou and Anqing, 2000–2020.

In Anqing, DAA decreased sharply from 76.76° to 18.43° during 2000–2010 (Table 4), suggesting strong early directional alignment. However, it increased continuously thereafter (Figure 10), reaching 163.42° by 2020, indicating pronounced directional divergence. Anqing exhibits a directional interaction pattern marked by a progressive increase in directional divergence between urban expansion and water body migration trajectories over time.

3.4. Structural Continuity of Urban and Water Systems

The COHESION results for urban built-up land and water bodies are summarized in Table 5. For both Jingzhou and Anqing, Water-COHESION values consistently exceed 95% throughout the study period, indicating stable and continuous water system structures. Urban-COHESION values range from approximately 87% to 97% and exhibit an overall increasing trend, suggesting that urban built-up areas maintain high structural continuity despite expansion and increasing morphological complexity.

Table 5.

COHESION Indices of Urban Built-up Land and Water Bodies (2000–2020).

3.5. Statistical Validation of Driving Factors

3.5.1. Institutional Mechanism Scoring

Institutional mechanisms were quantified using the 0–5 stage-based scoring system introduced in Section 2.4.5 (Table 6). The scoring was based on official documents released between 2000 and 2020, including territorial spatial plans, ecological restoration policies, water resource bulletins, and municipal governance reports [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. These materials provide evidence for the establishment and enforcement of blue lines, ecological redlines, development boundaries, and lake restoration measures.

Table 6.

Institutional Mechanism Scores for Jingzhou and Anqing, 2000–2020.

3.5.2. Spearman Correlation Analysis

The driving factors—expansion pressure, physical template, and institutional mechanisms—were represented by the Δ-values of built-up land, water area, and institutional change to align with the temporal variation in the synergy indicators.

In Jingzhou, institutional mechanisms exhibit a relatively strong correlation with DAA (ρ = 0.78) (Table 7). Built-up land change shows the strongest correlation with UWID (ρ = 0.80), while water area change is strongly negatively correlated with DAA (ρ = −1.00). Together, these results indicate that institutional, water-related, and expansion-related factors are all statistically associated with different dimensions of urban–water synergy in Jingzhou.

Table 7.

Spearman Rank Correlations Between Driving Factors and Synergy Indicators in Jingzhou.

In Anqing, built-up land change shows strong negative correlations with both UWII and DAA (ρ = −1.00), while water area change is strongly negatively correlated with DAA (ρ = −1.00) and UWII (ρ = −0.80) (Table 8). Institutional mechanisms exhibit higher correlations with UWID (ρ = 0.71) and SPAD (ρ = 0.89), whereas correlations with other indicators are relatively weaker. Overall, the correlation results suggest differentiated association patterns among driving factors and synergy indicators in Anqing.

Table 8.

Spearman Rank Correlations Between Driving Factors and Synergy Indicators in Anqing.

3.5.3. Results of the Principal Component Analysis

In Jingzhou, PC1 explains 75.24% of the total variance (Table 9), with all three factors showing relatively high loadings (ΔBuilt-up Land = 0.60; ΔWater Area = −0.63; ΔInstitutional Mechanisms = 0.50), indicating a strong shared variation among built-up land change, water area change, and institutional adjustment. PC2 explains 20.02% of the variance and is mainly characterized by a high loading of institutional mechanisms (−0.85), reflecting that institutional change constitutes a prominent component of variance beyond the primary land–water co-variation pattern. PC3 has a low explanatory power (4.73%) and is of limited analytical relevance.

Table 9.

PCA Loadings and Explained Variance of Driving Factors in Jingzhou and Anqing.

In Anqing, PC1 explains 69.60% of the variance and is primarily characterized by built-up land change (−0.69) and water area change (−0.60) (Table 9), indicating that land expansion and water area variation form the dominant axis of system change. Institutional mechanisms exhibit a relatively lower loading on PC1 (−0.40). PC2 explains 30.37% of the variance and is again mainly associated with institutional mechanisms (loading = −0.85), suggesting that institutional change represents an important secondary component of system variation. PC3 accounts for only 0.02% of the variance and is therefore negligible.

4. Discussion

4.1. Identification and Attribution of Urban–Water Synergy Differences

4.1.1. Comparative Differences in Urban–Water Synergy Modes

Based on the results presented in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, Jingzhou and Anqing exhibit clear and persistent differences in their urban–water synergy modes, as expressed through contrasting spatial interaction patterns during the study period. These differences are consistently reflected across land-use interactions, pathway relationships, and directional tendencies, indicating divergent evolutionary logics of urban–water interaction rather than short-term or isolated fluctuations.

Jingzhou is characterized by a convergent interaction mode, in which the three dimensions evolve in a relatively coordinated manner. In the land-use dimension, interactions shift from unidirectional urban encroachment toward restoration-oriented adjustment, corresponding to a transition from Case I to Case II in Table A1. Urban expansion pathways show increasing spatial alignment with the trajectories of water bodies, and directional relationships transition from early divergence toward renewed convergence in the later stage. In contrast, Anqing exhibits a divergent interaction mode. In the land-use dimension, change remains persistently dominated by water-to-urban conversion, corresponding to a stable expansion-dominated interaction pattern (Case I) in Table A1 throughout the study period. Pathway relationships remain weakly aligned, and directional tendencies evolve from early-stage coordination toward sustained divergence.

Overall, the contrast between the two cities is not fundamentally about “higher” versus “lower” urban–water synergy, but about two distinct structural modes of urban–water interaction. One mode is characterized by relatively closer spatial association and directional consistency, accompanied by a transition in land-use interaction from expansion-dominated to restoration-oriented patterns, whereas the other mode is characterized by persistent spatial separation, directional divergence, and continued expansion-dominated land-use interaction. These modes represent different configurations of urban–water interaction shaped by contrasting land-use trajectories and spatial constraints, providing a basis for subsequent analysis of their underlying driving mechanisms.

It should be noted that SPAD and DAA are designed to capture pathway and directional tendencies of urban–water interactions rather than fine-scale internal morphological variations. The meaningful interpretation of these indicators, therefore, presupposes a certain degree of overall structural continuity in the underlying spatial systems. To verify this prerequisite, COHESION is incorporated as a supplementary landscape pattern metric. The results indicate that both urban built-up land and water bodies maintain relatively high levels of structural continuity throughout the study period, supporting the applicability of centroid-based indicators for tendency-level analysis. Under this structural context, the identified interaction modes are interpreted as reflecting differences in dominant spatial relationships, whereas detailed diagnoses of internal fragmentation or polycentric configurations fall beyond the analytical scope of this study.

4.1.2. Verification of Driving-Factor Associations

Based on the Spearman rank correlation results reported in Section 3.5.2, multiple correlation coefficients in both Jingzhou and Anqing reach moderate to strong levels (|ρ| ≈ 0.7–1.0). Specifically, expansion pressure, represented by changes in built-up land, shows strong associations with land-use synergy and directional indicators; the physical template, represented by changes in water area, exhibits significant negative correlations with directional synergy (DAA) in both cities; and institutional mechanisms, represented by institutional change, display moderate to strong correlations with selected directional or pathway indicators in different cities.

These results indicate that expansion pressure, physical template, and institutional mechanisms are all statistically associated with urban–water synergy indicators across different synergy dimensions. This pattern suggests that variations in urban–water synergy are not random fluctuations but are systematically related to multiple driving factors, providing direct empirical support for the three-factor driving framework developed in this study under the Coupled Human and Natural Systems (CHANS) theoretical perspective [56].

4.1.3. Institutional Mechanisms as the Key Driving Factor

Principal component analysis (PCA) reveals the internal covariance structure among driving factors, providing a systematic perspective for understanding the functional roles of key drivers. As shown in Table 8, institutional mechanisms (ΔInstitutional Mechanisms) emerge as a relatively independent structural dimension in both Jingzhou and Anqing. In both cities, institutional mechanisms exhibit near-exclusive high loadings on the second principal component (PC2) (Jingzhou: −0.85, explaining 20.02% of the variance; Anqing: −0.85, explaining 30.37% of the variance). This result indicates that the variation in institutional mechanisms follows a logic distinct from the core pattern dominated by changes in built-up land and water area (PC1).

This structural finding is of particular significance: institutional mechanisms are not merely secondary outcomes of expansion pressure reflected by built-up land growth, nor of physical template conditions represented by changes in water area. Rather, they operate as a higher-level structural factor with an evolutionary logic distinct from land–water co-variation [57]. Insights from urban water collaborative governance practices further support this interpretation. Although built-up land expansion and water system protection and restoration are influenced by multiple factors—such as economic development, population dynamics, and natural conditions—their spatial outcomes are largely implemented through planning control and policy instruments [58]. Accordingly, the institutional “independence” identified by PCA is consistent with the real-world role of institutions as upper-level regulatory tools, endowing them with the capacity to influence the direction of system evolution [59]. A comparative analysis between the two cities shows that in Jingzhou, variation along this institution-dominated dimension corresponds closely with changes observed in multiple urban–water interaction indicators, with institutional adjustments accompanying sustained shifts in interaction patterns (Table 10). In contrast, in Anqing, although institutional changes exhibit some association with individual indicators, they do not coincide with a system-wide transition in urban–water interaction patterns, and institutional effects remain limited [60].

Table 10.

Institutional Mechanism Differences in Urban–Water Synergy between Jingzhou and Anqing.

Based on the combined evidence from structural characteristics and observed interaction outcomes, differences in the effectiveness and contextual embedding of institutional mechanisms contribute to understanding the divergent urban–water interaction trajectories observed in the two cities [61]. The “key” role of institutions lies not only in their independent structural influence revealed by PCA, but more importantly in whether such influence can be translated into sustained and systematic spatial regulation in practice. Moreover, although institutional mechanisms form an independent driving dimension in both cities, the pronounced disparity in observed interaction outcomes further indicates that institutional influence does not automatically translate into effective system regulation across different contexts, suggesting a possible transition of governance effectiveness from quantitative accumulation to qualitative transformation [62].

4.2. Factor Interactions and Threshold Effects

The evolution of urban–water synergy is shaped by the coupled effects of physical template, expansion pressure, and institutional mechanisms, rather than by any single factor [63,64,65,66]. Physical conditions provide rigid ecological constraints, expansion pressure acts as a continuous external disturbance [67], while institutional mechanisms operate as an upper-level structural factor that shapes the interaction between urban development and water systems [68]. The effectiveness of institutional regulation is jointly conditioned by ecological foundations and development pressure, which conditions whether the system remains locked in imbalance or has the potential to shift toward coordinated adjustment [69].

Within the multi-factor coupled urban–water system, institutional mechanisms serve as a key coordinating factor, whose influence does not increase in a continuously linear manner but often manifests as leap-like responses [24,25]. When execution capacity, organizational competence, and governance resources accumulate to a certain “institutional threshold”, the system’s regulatory capability may undergo a qualitative shift, thereby being associated with a state transition. Conversely, insufficient institutional input often fails to withstand expansion pressures and may even accelerate system degradation. This threshold effect helps to explain why the evolutionary pathways of the urban-water synergy diverge across different regions [70].

Taking Jingzhou as an example, since 2015, its institutional intervention capacity has improved significantly. For planning and control, a triple-layered control system of “blue lines—red lines—development boundaries” (referring, respectively, to water protection control lines, ecological protection redlines, and urban development boundaries) has been established. At the execution level, a “multi-plan integration” platform has largely promoted cross-departmental coordination. In practical implementation, a series of ecological restoration initiatives—such as dike removal for lake restoration, lake re-vegetation, and shoreline rehabilitation—have been launched [49,52]. These measures are temporally consistent with a strengthening of institutional capacity, alongside easing expansion pressures and a gradual shift from an “expansion-driven” toward an “ecological restoration-oriented” model [71].

In contrast, although Anqing’s planning documents set out several objectives for ecological protection and river-lake governance, its execution mechanisms remain underdeveloped, interdepartmental coordination is limited, and financial resources are constrained [48,50,53]. Consequently, policy effectiveness has long lingered below the institutional failure threshold, limiting its capacity to generate effective counterbalancing feedback against expansion pressures and further weakening the resilience of the natural system. As a result, the evolution of Anqing’s urban-water system remains trapped in a vicious cycle of “development priority—governance lag—continuous degradation.”

These phenomena are consistent with Ostrom’s institutional design principles, particularly those concerning “monitoring mechanisms,” “credible commitments,” and “institutional supply.” Institutions must not only exist but also demonstrate adequate enforcement power, coordination capacity, and public trust to function effectively as system regulators [25]. Furthermore, the “policy threshold” concept broadens the CHANS framework (Coupled Human and Natural Systems theory) by deepening the understanding of the regulatory capacity of the social subsystem within human–environment systems [24] and highlights the nonlinear regulatory capacity of institutional factors in overcoming intertwined natural constraints and expansion pressures.

In summary, the “institutional threshold” is not merely a theoretical explanatory tool but a critical identification indicator in practical planning and policy intervention. Assessing whether an urban–water system can move toward a more synergistic configuration depends less on the number of factors involved and more on whether its institutional mechanisms have crossed a critical threshold and formed an efficient, sustainable, and systemically integrated intervention chain [72].

4.3. Mechanism-Oriented Strategies for Enhancing Urban–Water Synergy

Synthesizing the preceding analyses, the evolution of urban–water synergy is not determined by the effect of any single factor. Rather, it depends on whether institutional mechanisms are able to continuously translate their potential regulatory capacity into effective governance outcomes [25]. Accordingly, governance strategies should place institutional capacity enhancement at the core, while being coordinated with improvements in spatial conditions and adjustments to expansion pressure [24].

4.3.1. Coordinated Regulation of the Physical Template and Expansion Pressure

In contexts where urban–water spatial relationships have long remained misaligned, relying solely on institutional regulation often entails high implementation costs and resistance [73]. It is therefore necessary to guide urban expansion in advance through targeted spatial integration and land-use constraints [74]. This approach helps reduce the adjustment burden faced by subsequent institutional interventions.

Specifically, such guidance can be achieved by clarifying construction intensity controls in areas adjacent to water bodies and restricting the disorderly expansion of newly built-up land toward water-sensitive zones [75]. In addition, existing construction land can be guided toward more intensive use in less sensitive areas [76]. Through these measures, the structural mismatch between urban expansion and water system evolution can be reduced at the spatial level.

These interventions are not intended to directly alter urban–water relationships. Instead, by alleviating unidirectional land consumption and expansion pressure, they create more stable spatial and developmental conditions for the sustained engagement of institutional mechanisms. In this way, they primarily serve a supportive and buffering role.

4.3.2. Institutional Mechanisms and Governance Transition Under Threshold Effects

The critical difference in institutional mechanisms across cities lies not in whether they are established, but in whether they can be effectively embedded into the governance of urban–water spatial processes [77]. In cities where synergy improvement is more evident, institutional adjustments are translated into stable spatial behavioral feedback, guiding land-use decisions and development activities to align with the configuration of water systems. By contrast, in cities where synergy remains constrained, institutional influence tends to remain at the framework level, making it difficult to break the long-term imbalance in urban–water relationships.

Accordingly, institutional governance should shift its emphasis from “institutional establishment” to “institutional effectiveness” [78]. Systematic enhancement should focus on three aspects: enforcement strength, interdepartmental coordination, and temporal continuity [79]. On the one hand, planning and regulatory requirements need to be rigidly implemented in actual decision-making processes [80,81], for example, by ensuring that zoning controls, development intensity limits, and water-related protection rules are consistently applied in land-use approval and project siting, so that institutional rules can exert stable constraints on spatial development behaviors rather than being continuously weakened by expansion pressures. On the other hand, improving cross-sectoral coordination is essential to reduce fragmentation in policy execution [82]. In practice, this may involve aligning review standards and implementation procedures across planning, land, and water-related agencies, allowing regulatory effects to extend to land-use conversion, spatial pathway organization, and the guidance of expansion directions in a more coherent manner.

In addition, institutional interventions must maintain sufficient continuity and stability. This allows their regulatory effects to accumulate over time [83]. For instance, when planning controls and regulatory requirements are applied consistently across successive development cycles, their influence on spatial behaviors becomes more predictable and enduring. When institutional regulation shifts from intermittent intervention to sustained constraint and gradually exceeds an effective operational level, its influence may transition from latent potential to observable synergy improvement. Under such conditions, the urban–water system can move from passive response toward proactive regulation [84].

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the main urban areas of Jingzhou and Anqing and adopts a combined quantitative and qualitative approach. By constructing land-use synergy indicators (UWII and UWID), a pathway synergy indicator (SPAD), and a directional synergy indicator (DAA), the study analyzes the spatial evolution of urban and water areas from 2000 to 2020 and systematically reveals the evolutionary characteristics of urban–water synergy in the two cities. In addition, the roles and interactions of three categories of driving factors—physical template, expansion pressure, and institutional mechanisms—are examined. On this basis, a factor-responsive optimization strategy framework is proposed. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Jingzhou and Anqing exhibit two distinct urban–water synergy modes across the three dimensions. Jingzhou is characterized by a convergent interaction mode, marked by increasing alignment in land-use interactions, spatial pathways, and directional tendencies, whereas Anqing exhibits a divergent interaction mode, in which these relationships remain weakly aligned and increasingly separated.

- (2)

- Differences in urban–water synergy modes between the two cities are related to the combined influence of three categories of driving factors: the physical template, expansion pressure, and institutional mechanisms.

- (3)

- Among the three categories of factors, institutional mechanisms are interpreted as an upper-level regulatory layer of the urban–water system. Policy enforcement effectiveness does not follow a linear trajectory but instead is discussed as exhibiting an “institutional threshold” effect. When institutional capacity approaches or exceeds this critical point, the urban–water system may shift from expansion-driven imbalance to coordinated adjustment.

- (4)

- Based on the identified driving factors and their observed associations with urban–water interaction patterns, this study outlines an analytical framework in which institutional mechanisms play a central interpretive role. Institutional threshold crossing is discussed as a possible explanatory perspective for understanding divergent urban–water interaction trajectories, while physical template conditions and expansion pressure are considered supporting contextual factors. Together, these elements help structure the analysis of potential “mechanism breakpoints” in urban–water systems. The framework is intended as a diagnostic reference for examining urban–water interaction challenges and informing context-sensitive governance considerations through a “diagnosis–intervention–transition” logic.

This study has certain limitations. First, the institutional mechanism score is constructed using a relatively simplified evaluation approach. While it captures general policy trends, it may not fully reflect cross-sectoral differences in enforcement effectiveness or governance capacity. Second, the sample size and data volume are constrained by research scale and data availability, as the empirical analysis is based on a limited number of time periods and two representative medium-sized cities. Third, although the proposed framework explains urban–water synergy from spatial, institutional, and stress-related perspectives, it primarily emphasizes macro-scale structural interactions. Process-oriented factors—such as water quality dynamics, pollution levels, landscape alteration, and engineering-based restoration measures—are not explicitly incorporated. These factors may influence urban–water relationships through synergistic or antagonistic pathways and therefore merit further investigation in future research. The use of SPAD and DAA is subject to methodological scope conditions. These indicators are better suited to relatively aggregated urban systems, while in highly polycentric urban contexts characterized by complex, multi-directional expansion, their representativeness may be reduced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F. and Q.C.; methodology, Y.F. and C.T.; formal analysis, Y.F. and C.T.; data curation, Y.F. and C.T.; visualization, Y.F. and C.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F. and C.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.F. and Q.C.; supervision, Q.C.; project administration, Q.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 2024 Industry-University Cooperative Education Program of the Ministry of Education, “Teaching Exploration of Urban-Rural Planning and Design under the Context of Big Data and Machine Learning Technologies” (Project No. 231103242252339).

Data Availability Statement

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Classification of Urban–Water Land-Use Interaction Patterns Based on UWII and UWID

Table A1.

Classification of Urban–Water Land-Use Interaction Patterns Based on UWII and UWID.

Table A1.

Classification of Urban–Water Land-Use Interaction Patterns Based on UWII and UWID.

| Case | UWII (Conversion Intensity) | UWID (Conversion Direction) | Main Characteristics | Land-Use Interaction Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Elevated | Positive | Frequent land conversion dominated by urban expansion into water bodies | Elevated-intensity, expansion-dominated interaction pattern |

| II | Elevated | Negative | Frequent land conversion dominated by water-body restoration | Elevated-intensity, restoration-dominated interaction pattern |

| III | Elevated | Approximately zero | Frequent land conversion with a relatively balanced pattern between expansion and restoration | Elevated-intensity, bidirectional interaction pattern |

| IV | Reduced | Positive | Infrequent land conversion dominated by urban encroachment into water bodies | Reduced-intensity, expansion-dominated interaction pattern |

| V | Reduced | Negative | Infrequent land conversion dominated by water-body restoration | Reduced-intensity, restoration-dominated interaction pattern |

| VI | Reduced | Approximately zero | Limited land conversion with a near-balanced conversion direction | Reduced-intensity, low-disturbance balanced interaction pattern |

Appendix A.2. Land Use Transition Matrices of Jingzhou and Anqing (2000–2020)

Table A2.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Jingzhou Central Area from 2000 to 2005 (Unit: km2).

Table A2.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Jingzhou Central Area from 2000 to 2005 (Unit: km2).

| Type | Grassland | Cultivated Land | Construction Land | Forest Land | Water Bodies | 2000 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 0.0972 | / | 0.0045 | / | / | 0.1017 |

| Cultivated Land | 0.0036 | 1113.8346 | 4.3713 | 0.6318 | 8.8353 | 1127.6766 |

| Construction Land | / | 1.8027 | 133.3647 | 0.0315 | 0.2853 | 135.4842 |

| Forest Land | / | 0.3141 | 0.3438 | 25.1568 | 0.0252 | 25.8399 |

| Water Bodies | / | 2.0196 | 1.2213 | 0.0450 | 266.9634 | 270.2493 |

| 2005 Total | 0.1008 | 1117.9710 | 139.3056 | 25.8651 | 276.1092 | 1559.3527 |

Note: The symbol “/” indicates no land use conversion or negligible conversion area.

Table A3.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Jingzhou Central Area from 2005 to 2010. (Unit: km2).

Table A3.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Jingzhou Central Area from 2005 to 2010. (Unit: km2).

| Type | Grassland | Cultivated Land | Construction Land | Forest Land | Water Bodies | Unused Land | 2005 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 0.0999 | / | / | / | 0.0002 | / | 0.1001 |

| Cultivated Land | 0.0006 | 1054.6017 | 31.9162 | 9.2676 | 21.9842 | 0.0020 | 1117.7723 |

| Construction Land | 0.0022 | 9.6923 | 128.7205 | 0.0641 | 0.5864 | 0.2104 | 139.2759 |

| Forest Land | / | 5.3846 | 0.6752 | 19.7205 | 0.0721 | / | 25.8524 |

| Water Bodies | 0.0836 | 19.8384 | 6.4179 | 1.5362 | 248.1133 | / | 275.9894 |

| 2010 Total | 0.1863 | 1089.5170 | 167.7298 | 30.5884 | 270.7562 | 0.2124 | 1558.9901 |

Note: The symbol “/” indicates no land use conversion or negligible conversion area.

Table A4.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Jingzhou Central Area from 2010 to 2015. (Unit: km2).

Table A4.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Jingzhou Central Area from 2010 to 2015. (Unit: km2).

| Type | Grassland | Cultivated Land | Construction Land | Forest Land | Water Bodies | Unused Land | 2010 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 0.1805 | 0.0044 | 0.0021 | / | / | / | 0.1870 |

| Cultivated Land | 0.0010 | 1062.5973 | 23.4287 | 0.4516 | 2.9573 | 0.0070 | 1089.4429 |

| Construction Land | 0.0048 | 3.3630 | 163.9301 | 0.0499 | 0.3736 | / | 167.7214 |

| Forest Land | / | 0.6055 | 0.9481 | 28.8969 | 0.1267 | / | 30.5772 |

| Water Bodies | 0.0008 | 3.1216 | 5.6380 | 0.1099 | 261.8308 | / | 270.7011 |

| Unused Land | / | 0.0052 | / | / | / | 0.2072 | 0.2124 |

| 2015 Total | 0.1871 | 1069.6970 | 193.9470 | 29.5083 | 265.2884 | 0.2142 | 1558.8420 |

Note: The symbol “/” indicates no land use conversion or negligible conversion area.

Table A5.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Jingzhou Central Area from 2015 to 2020. (Unit: km2).

Table A5.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Jingzhou Central Area from 2015 to 2020. (Unit: km2).

| Type | Grassland | Cultivated Land | Construction Land | Forest Land | Water Bodies | 2015 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 0.0962 | 0.0043 | / | / | 0.0852 | 0.1857 |

| Cultivated Land | 0.0065 | 986.8650 | 48.8458 | 5.4842 | 27.8806 | 1069.0821 |

| Construction Land | 0.0008 | 27.7383 | 154.2043 | 0.5597 | 11.3849 | 193.8880 |

| Forest Land | / | 9.9132 | 0.5832 | 17.9247 | 1.0364 | 29.4575 |

| Water Bodies | 0.0025 | 26.0671 | 6.9709 | 0.3105 | 231.5504 | 264.9015 |

| Unused Land | / | 0.0120 | 0.2022 | / | / | 0.2142 |

| 2020 Total | 0.1060 | 1050.5999 | 210.8064 | 24.2791 | 271.9375 | 1557.7289 |

Note: The symbol “/” indicates no land use conversion or negligible conversion area.

Table A6.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Anqing Central Area from 2000 to 2005. (Unit: km2).

Table A6.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Anqing Central Area from 2000 to 2005. (Unit: km2).

| Type | Grassland | Cultivated Land | Construction Land | Forest Land | Water Bodies | 2000 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 95.8743 | 0.0702 | 0.0081 | 0.2214 | 0.0306 | 96.2046 |

| Cultivated Land | 0.0846 | 319.3983 | 16.9902 | 0.1233 | 0.0909 | 336.6873 |

| Construction Land | 0.0045 | 0.0621 | 58.5378 | 0.0063 | 0.0243 | 58.6350 |

| Forest Land | 0.2682 | 0.0954 | 0.0063 | 93.3120 | 0.0099 | 93.6918 |

| Water Bodies | 0.0171 | 0.0891 | 1.0611 | 0.0144 | 224.8821 | 226.0638 |

| 2005 Total | 96.2487 | 319.7151 | 76.6035 | 93.6774 | 225.0378 | 811.2825 |

Table A7.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Anqing Central Area from 2005 to 2010. (Unit: km2).

Table A7.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Anqing Central Area from 2005 to 2010. (Unit: km2).

| Type | Grassland | Cultivated Land | Construction Land | Forest Land | Water Bodies | 2000 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 94.8.22 | 0.2756 | 0.6007 | 0.3746 | 0.0941 | 96.2272 |

| Cultivated Land | 0.2664 | 301.7435 | 16.6874 | 0.3177 | 0.6535 | 319.6685 |

| Construction Land | 0.0174 | 0.4835 | 76.0378 | 0.0069 | 0.0548 | 76.6004 |

| Forest Land | 0.2960 | 1.3896 | 0.8944 | 91.0246 | 0.0520 | 93.6566 |

| Water Bodies | 0.1026 | 0.8094 | 0.5088 | 0.0487 | 223.4606 | 224.9301 |

| 2005 Total | 95.5646 | 304.7015 | 94.7291 | 91.7725 | 224.3150 | 811.0827 |

Table A8.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Anqing Central Area from 2010 to 2015. (Unit: km2).

Table A8.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Anqing Central Area from 2010 to 2015. (Unit: km2).

| Type | Grassland | Cultivated Land | Construction Land | Forest Land | Water Bodies | Unused Land | 2005 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 93.4191 | 0.3599 | 1.3136 | 0.3566 | 0.1079 | / | 95.5571 |

| Cultivated Land | 0.3853 | 290.1305 | 12.4039 | 0.3897 | 1.3673 | 0.0060 | 304.6827 |

| Construction Land | 0.0441 | 0.8628 | 93.6823 | 0.0250 | 0.1154 | / | 94.72.6 |

| Forest Land | 0.3430 | 0.3838 | 2.8510 | 87.9626 | 0.0762 | 0.1587 | 91.7753 |

| Water Bodies | 0.1109 | 0.7261 | 1.8671 | 0.0712 | 221.5026 | / | 224.2778 |

| 2010 Total | 94.3023 | 292.4630 | 112.1179 | 88.8051 | 223.1694 | 0.1647 | 811.0224 |

Note: The symbol “/” indicates no land use conversion or negligible conversion area.

Table A9.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Anqing Central Area from 2015 to 2020. (Unit: km2).

Table A9.

Land Use Transition Matrix of Anqing Central Area from 2015 to 2020. (Unit: km2).

| Type | Grassland | Cultivated Land | Construction Land | Forest Land | Water Bodies | Unused Land | 2010 Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassland | 90.8504 | 0.9222 | 1.1193 | 0.8717 | 0.3109 | 0.1732 | 94.2477 |

| Cultivated Land | 0.9138 | 271.3875 | 16.4631 | 1.0028 | 2.2270 | 0.3440 | 292.3383 |

| Construction Land | 1.5758 | 11.5875 | 94.0349 | 2.0623 | 2.1445 | 0.7033 | 112.1026 |

| Forest Land | 1.0114 | 0.9626 | 1.6424 | 84.8104 | 0.1637 | 0.1715 | 88.7621 |

| Water Bodies | 0.2395 | 2.8720 | 3.1976 | 0.1810 | 216.3475 | 0.0035 | 222.8413 |

| Unused Land | / | 0.0004 | 0.0056 | 0.0899 | / | 0.0688 | 0.1647 |

| 2015 Total | 94.5911 | 287.7266 | 116.4630 | 89.0182 | 221.1936 | 1.4643 | 810.4567 |

Note: The symbol “/” indicates no land use conversion or negligible conversion area.

Appendix A.3. Centroid Coordinates of Urban Areas and Waterbodies in Jingzhou and Anqing (2000–2020)

Table A10.

Centroid Coordinates of Urban Areas and Water Bodies in Jingzhou from 2000 to 2020.

Table A10.

Centroid Coordinates of Urban Areas and Water Bodies in Jingzhou from 2000 to 2020.

| Year | Water Space Centroid (°E) | Water Space Centroid (°N) | Urban Space Centroid (°E) | Urban Space Centroid (°N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 112.1898 | 30.3795 | 112.2171 | 30.3481 |

| 2005 | 112.1983 | 30.3770 | 112.2182 | 30.3500 |

| 2010 | 112.2045 | 30.3787 | 112.2162 | 30.3549 |

| 2015 | 112.2110 | 30.3760 | 112.2171 | 30.3588 |

| 2020 | 112.2012 | 30.3717 | 112.2174 | 30.3567 |

Note: All coordinates are expressed in decimal degrees (°).

Table A11.

Centroid Coordinates of Urban Areas and Water Bodies in Anqing from 2000 to 2020.

Table A11.

Centroid Coordinates of Urban Areas and Water Bodies in Anqing from 2000 to 2020.

| Year | Water Space Centroid (°E) | Water Space Centroid (°N) | Urban Space Centroid (°E) | Urban Space Centroid (°N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 117.0838 | 30.5885 | 117.0550 | 30.5526 |

| 2005 | 117.0839 | 30.5887 | 117.0538 | 30.5536 |

| 2010 | 117.0841 | 30.5889 | 117.0552 | 30.5543 |

| 2015 | 117.0844 | 30.5892 | 117.0559 | 30.5518 |

| 2020 | 117.0841 | 30.5888 | 117.0617 | 30.5561 |

Note: All coordinates are expressed in decimal degrees (°).

References

- Maimaiti, B.; Chen, S.; Kasimu, A.; Simayi, Z.; Aierken, N. Urban Spatial Expansion and Its Impacts on Ecosystem Service Value of Typical Oasis Cities around Tarim Basin, Northwest China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 104, 102554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Lu, J.; Sun, D. Influence of Urban Agglomeration Expansion on Fragmentation of Green Space: A Case Study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Land 2022, 11, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, S.; Wen, Y.; Chen, H. Study on the Driving Factors of Ecosystem Service Value under the Dual Influence of Natural Environment and Human Activities. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanakakis, V.A.; Paranychianakis, N.V.; Angelakis, A.N. Water Supply and Water Scarcity. Water 2020, 12, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.D.; Shuster, W.; Hunt, W.F.; Ashley, R.; Butler, D.; Arthur, S.; Trowsdale, S.; Barraud, S.; Semadeni-Davies, A.; Bertrand-Krajewski, J.-L.; et al. SUDS, LID, BMPs, WSUD and More—The Evolution and Application of Terminology Surrounding Urban Drainage. Urban. Water J. 2015, 12, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Formiga, K.T.M.; Milograna, J. Integrated Systems for Rainwater Harvesting and Greywater Reuse: A Systematic Review of Urban Water Management Strategies. Water Supply 2023, 23, 4112–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechowska, E. Approaches in Research on Flood Risk Perception and Their Importance in Flood Risk Management: A Review. Nat. Hazards 2022, 111, 2343–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, I.; Aneaus, S. Landscape Transformation of an Urban Wetland in Kashmir Himalaya, India Using High-Resolution Remote Sensing Data, Geospatial Modeling, and Ground Observations over the Last 5 Decades (1965–2018). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, K.; Gao, W. Monitoring the Changes in Land Use and Landscape Pattern in Recent 20 Years: A Case Study in Wuhan, China. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 272, 01022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, F.; Ou, S.-J.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Chien, Y.-C. Analysis of Landscape Spatial Pattern Changes in Urban Fringe Area: A Case Study of Hunhe Niaodao Area in Shenyang City. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 17, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhu, H. Assessing the Interaction Impacts of Multi-Scenario Land Use and Landscape Pattern on Water Ecosystem Services in the Greater Bay Area by Multi-Model Coupling. Land 2024, 13, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhsen, M.; Hammad, A.A.; Elhannani, M. Effect Of Land-Use Changes On Landscape Fragmentation: The Case Of Ramallah Area In Central Palestine. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 16, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, H. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Evolution Relationships between Land-Use/Land Cover Change and Landscape Pattern in Response to Rapid Urban Sprawl Process: A Case Study in Wuhan, China. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 182, 106716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.K.; Sajjad, H.; Roshani; Rahaman, H.; Sharma, Y. Exploring the Impact of Land Use/Land Cover Changes on the Dynamics of Deepor Wetland (a Ramsar Site) in Assam, India Using Geospatial Techniques and Machine Learning Models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 4043–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Pan, J.; Gong, N.; Yan, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhao, B. Spatial Response of Urban Land Use Intensity to Ecological Networks: A Case Study of Xi’an Metropolitan Region, China. Envir. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 36685–36701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Luo, Q.; Zhu, Z. Integrating Static and Dynamic Analyses in a Spatial Management Framework to Enhance Ecological Networks Connectivity in the Context of Rapid Urbanization. Ecol. Model. 2025, 501, 111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yuan, W.; Wang, L.; Ding, J.; Li, C.; Wang, B. Consideration of River Governance Based on the Concept of Urban Spatial Resilience. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 983, 012087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Seetharaman, A.; Maddulety, K. Framework for Sustainable Urban Water Management in Context of Governance, Infrastructure, Technology and Economics. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 3903–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluchinotta, I.; Pagano, A.; Vilcan, T.; Ahilan, S.; Kapetas, L.; Maskrey, S.; Krivtsov, V.; Thorne, C.; O’Donnell, E. A Participatory System Dynamics Model to Investigate Sustainable Urban Water Management in Ebbsfleet Garden City. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 67, 102709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Rosely, W.I.H.; Voulvoulis, N. Systems Thinking for the Sustainability Transformation of Urban Water Systems. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1127–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Li, Q.; Khan, S.; Khalaf, O.I. Urban Water Resource Management for Sustainable Environment Planning Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 86, 106515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Huang, A.; Yin, X.; Yang, J.; Deng, L.; Lin, Z. Investigating the Impact of Urbanization on Water Ecosystem Services in the Dongjiang River Basin: A Spatial Analysis. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ning, Q.; Zhou, H.; Lai, N.; Song, Q.; Ji, Q.; Zeng, Z. Digital Research on the Resilience Control of Water Ecological Space under the Concept of Urban-Water Coupling. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1270921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dietz, T.; Carpenter, S.R.; Alberti, M.; Folke, C.; Moran, E.; Pell, A.N.; Deadman, P.; Kratz, T.; Lubchenco, J.; et al. Complexity of Coupled Human and Natural Systems. Science 2007, 317, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 58–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Han, L. The Synergistic Effect of Urban and Rural Ecological Resilience: Dynamic Trends and Drivers in Yunnan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northam, R.M. Urban Geography; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Cai, Y.; Yang, Y. Construction and Application of a Water Resources Spatial Equilibrium Model: A Case Study in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Water 2023, 15, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Q.; Su, X.; Zheng, S.; Li, Y. Interaction between Surface Water and Groundwater in the Alluvial Plain (Anqing Section) of the Lower Yangtze River Basin: Environmental Isotope Evidence. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2021, 329, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Q.; Su, X.; Wang, S.; Zheng, S.; Li, Y. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Evolution of Groundwater in the Alluvial Plain (Anqing Section) of the Lower Yangtze River Basin: Multivariate Statistical and Inversion Model Analyses. Water 2021, 13, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Ni, H.; Liu, D.; Liang, H. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Water Resource Disparities in Yangtze River Economic Zone. Water 2024, 16, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z. Coupling Coordination and Spatial-Temporal Evolution of Water-Land-Food Nexus: A Case Study of Hebei Province at a County-Level. Land 2023, 12, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Zuo, D.; Gong, Z. How Does the Coupling Coordination Relationship between High-Quality Urbanization and Land Use Evolve in China? New Evidence Based on Exploratory Spatiotemporal Analyses. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Ge, D.; Yan, R.; Ma, Y.; Sun, D.; Lu, M.; Lu, Y. The Evolution of the Interactive Relationship between Urbanization and Land-Use Transition: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Delta. Land 2021, 10, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; You, X. A Study on Spatio-Temporal Coordination and Driving Forces of Urban Land and Water Resources Utilization Efficiency in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 14, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G. Exploring the Spatial–Temporal Evolution and Driving Mechanisms for Coupling Coordination between Green Transformation of Urban Construction Land and Industrial Transformation and Upgrading: A Case Study of the Urban Agglomeration in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 119385–119405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, C.; Kang, X.; Chen, F. A Loosely Coupled Model for Simulating and Predicting Land Use Changes. Land 2023, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kuang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Qin, Y.; Ning, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Yan, C.; et al. Spatiotemporal Characteristics, Patterns, and Causes of Land-Use Changes in China since the Late 1980s. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Zou, Y.; Chen, M.; Shen, J. Monitoring the Spatiotemporal Trajectory of Urban Area Hotspots Using the SVM Regression Method Based on NPP-VIIRS Imagery. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O.; Khalis, A. Urban Water Systems: Development of Micro-Level Indicators to Support Integrated Policy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.T.T. Land Mosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes and Regions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, W. Location and Land Use: Toward a General Theory of Land Rent; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964; pp. 55–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Su, B.; Chen, Z.; Lin, W. China’s Environmental Policy Intensity for 1978–2019. Sci Data 2022, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; He, J.; Yu, E.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H. Driving Factors of Ecosystem Services and Their Trade-Offs and Synergies in Different Land Use Functional Zones: A Case Study of Shanxi Province, China. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 28, 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murariu, G.; Dinca, L.; Munteanu, D. Trends and Applications of Principal Component Analysis in Forestry Research: A Literature and Bibliometric Review. Forests 2025, 16, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]