Abstract

Focusing on Hebei Province in China, the work investigated the impact of implicit land use transition (ILUT) on land use carbon emissions (LUCEs) for dual carbon goals. A county-level evaluation system and a measurement model were constructed to explore ILUT and carbon emissions’ spatiotemporal progression, respectively. The optimal spatial econometric model was selected by employing different testing methods to elucidate how ILUT affected carbon emissions. LUCEs increased from 49.7964 million tons (2000) to 107.401 million tons (2015) and dropped to 92.2173 million tons by 2020. The overall exhibited an inverted V-shape. Values were generally higher in the southeast and lower in the northwest. ILUT index across counties increased from 2000 to 2020, with polarization of implicit indices intensified. Spatial distribution showed that the southeastern area exhibited notably higher values compared to the northwestern parts. Significant positive spatial correlation existed between ILUT and carbon emissions within the county, while a significant negative spatial correlation was observed with carbon emissions in neighboring counties. These findings provide scientific support for formulating differentiated land use policies and optimizing carbon emission control strategies in Hebei Province, holding significant practical value for regional dual carbon targets.

1. Introduction

Global warming represents a significant obstacle facing human society and sustainable development, with excessive greenhouse gas emissions being a primary driver of this trend. Consequently, the transition to a low-carbon future through energy conservation and emission reduction is now a universally recognized global priority [1,2]. As a primary carrier of carbon sources and sinks in ecosystems, land use carbon emissions (LUCEs)—that is, the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions generated jointly by direct land use changes and human production activities carried on land—account for approximately one-quarter of the global total greenhouse gas emissions, and these emissions are only surpassed by those from industrial sources [3]. Countries have successively proposed carbon reduction targets to address this challenge [4,5]. Particularly, China explicitly announced its goals to fulfill the dual carbon goals (peaking by 2030, neutrality by 2060) at the 75th United Nations General Assembly [6]. This strategic decision imposes urgent requirements for a low-carbon transition across various socio-economic activities.

The transition of land resource utilization patterns serves as a cornerstone for achieving national low-carbon development goals. Traditional investigation predominantly examined explicit morphological transitions’ influence on land use (e.g., quantitative and spatial conversions of cropland, forest land, and construction land) on carbon emissions [7,8]. Analyses merely relying on land type classification fail to capture the full complexity of LUCE mechanisms with the transition in China’s land use policy from a focus on scale to an emphasis on quality and efficiency. Land use transition originated from forest transition research [9,10] and was first introduced to China by scholar Long Hualou. Initially, it referred to the temporal changes in land use forms corresponding to socio-economic development transitions [11]. With the advancement of research, Long Hualou deepened the connotation of land use transition from a theoretical perspective [12], dividing it into two core dimensions: explicit land use transition and implicit land use transition, which provides a fundamental theoretical framework for subsequent studies. Specifically, explicit land use transition focuses on quantitative changes and spatial conversions between land types [13], with a clear connotation and mature definition in academia. In contrast, implicit land use transition (ILUT) can only be identified through data analysis and monitoring measurements [14], focusing on the qualitative dimension of land use and serving as a key dimension in land use transition research that better reflects underlying laws. From the perspective of land input–output, scholars [15] further divide ILUT into land use input, land use output, and land use intensity. Land use input refers to the allocation status of factor and public service inputs [16]. Land use output refers to the benefits generated by the interaction between land and the external environment during the land use process [16]. Land use intensity refers to the status of resource consumption and carrying pressure [17]. To summarize, the core connotation of implicit land use transition (ILUT) can be defined as the systematic and fundamental changes in implicit land use forms over the temporal dimension, characterized by interconnected and co-evolving multi-dimensional characteristics of “input, output, and intensity”. This qualitative change is closely related to socio-economic transition, and compared with explicit land use transition, it is more capable of penetrating the underlying driving logic of carbon emissions, while also driving crucial changes in carbon emissions [12,14]. As a profound driver of carbon emission changes, the mechanism of ILUT’s influence urgently requires systematic clarification.

Current academic research primarily focuses on LUCEs’ spatiotemporal evolution [18], influencing factors [19], and the relationship with economic growth [20,21]. Numerous factors have been identified as having significant impacts on LUCEs, including GDP [22,23], population size [24,25], energy consumption [26], and sectoral composition [27]. Although existing studies have accumulated substantial achievements, several research gaps remain, particularly the effects of comprehensive socioeconomic factors on LUCEs. This neglect of integrated socioeconomic drivers essentially stems from a limited understanding of land use transition [28]. Land use transition refers to the conversion between different land categories [29,30] as well as the spatial projection of socioeconomic activities [31]. Solely focusing on explicit changes [32] (e.g., the shift from agricultural land to built-up areas) does not capture the underlying drivers, such as economic structure, population mobility, and development models. The closer interconnection of ILUT with socioeconomic activities is evidenced by its pronounced regional, comprehensive, and trend-related characteristics. Therefore, it forms the intrinsic driving mechanism of LUCEs, exerting a more fundamental and profound impact than explicit transition [33]. Current research focuses on the explicit carbon emissions of land-use type changes [34], such as changes in construction land [35], forest land [36,37], and cropland [38,39]. They cannot reveal the role of socio-economic driving mechanisms behind land use in carbon emissions and seldom address the implicit transitions reflecting land-use transition [40]. Meanwhile, land use behaviors in one area may generate external effects on adjacent areas due to factors such as the spatial proximity of land [41] and land use’s dynamics [42,43]. Lesage [44] equated the external effect with a spatial spillover effect. LUCEs exhibit significant spatial spillover effects [41]—for instance, factors such as urbanization [45], economic globalization [46], and information and communications technology [47] all exert spatial spillover effects on LUCEs. Moreover, ILUT has spatial spillover effects on urban economies [48], food production [49], as well as urban-rural income inequality [50]. However, whether ILUT exerts direct impacts and spatial spillover effects on LUCEs has not been clearly answered by existing studies. Based on the above context, this study introduces spatial econometric models as the core analytical framework. This method explicitly incorporates a spatial weight matrix to characterize the interdependencies between geographically or economically connected units, thereby overcoming the limitation of traditional econometric models that assume observational units are independent of each other [46]. The fundamental principle is that ignoring such spatial dependence will lead to model specification bias and invalid estimation. Specifically, the Spatial Lag Model (SLM) mainly adopted in this study is used to analyze the spatial diffusion effect of the explained variable itself [42]; the Spatial Error Model (SEM) is employed to handle the uncaptured spatial dependence in the model’s error term to ensure estimation efficiency [51]; while the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM), as a more general specification, not only accommodates both of the aforementioned effects but also directly estimates and quantifies the spatial spillover effects of the core explanatory variable (e.g., local implicit land use transition) on neighboring regions [47].

Recently, rapid urbanization and industrialization in Hebei Province have significantly intensified the demand for land resource development. This has driven drastic changes in the explicit forms of land use and triggered implicit, systematic transitions. An implicit transition model characterized by extensive factor inputs can no longer support the sustainable urbanization goals of Hebei Province under increasingly stringent resource and environmental constraints. Crucially, the process of ILUT is closely and complexly linked to regional carbon emission dynamics. Therefore, accurately identifying and regulating the carbon emissions of ILUT has become a critical pathway to balancing regional land resource utilization, economic development, and environmental protection. Existing studies explore the spatial correlation between ILUT and carbon emissions [15]. They are limited to overall correlation analysis, focusing on explicit morphological changes and the direct conversion of land use types. Few have quantitatively examined the direct impacts and spatial spillover effects of ILUT on carbon emissions of counties from a spatial econometric perspective. Neglecting such complex spatial effects may bias assessments of implicit carbon transition, which undermines the precision and coordination of carbon reduction policies. Most existing studies adopt large-scale basic research units [52], with limited attention paid to studies taking counties as small-scale basic units. County-level research directly affects the implementation of grassroots policies [19] and is crucial for China’s future green transition and low-carbon development.

Therefore, this study aims to systematically reveal the spatial effects of ILUT on LUCEs at the county scale. The specific objectives are as follows: (1) construct a comprehensive evaluation index system for county-level ILUT based on the three dimensions of “land use input–output–intensity” and analyze its spatiotemporal evolution; (2) establish an integrated carbon emission accounting system combining direct and indirect methods to measure LUCEs and explore their spatiotemporal evolutionary features; (3) empirically test the spatial autocorrelation between ILUT and LUCEs, and quantify the spatial effects of ILUT on LUCEs using spatial econometric models; (4) propose targeted land management policy recommendations for counties in Hebei Province to achieve carbon emission reduction by regulating ILUT, based on empirical results. This study expects to theoretically deepen the understanding of carbon emissions from implicit land use and practically provide a precise and operable scientific basis for low-carbon land management at the county scale. Guided by land use transition theory and spatial spillover theory, the following testable research hypotheses are proposed:

H1:

ILUT exerts a significant inhibitory effect on local carbon emissions (i.e., a negative direct impact).

H2:

ILUT has a significant spatial spillover effect on carbon emissions in neighboring regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Region Overview

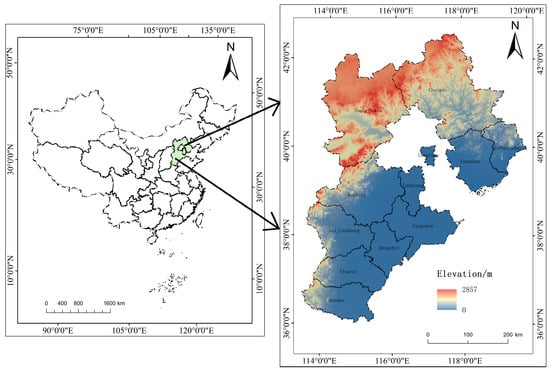

Hebei Province is located in the North China Plain (36°05′–42°40′ N and 113°27′–119°50′ E). Its northern zone comprises the Yanshan Mountains and the Bashang Plateau. It borders the Bohai Sea to the east, Shandong and Henan provinces to the south, and Shanxi Province to the west, with the Taihang Mountains as a natural boundary. Enclosing Beijing and Tianjin within its territory, Hebei Province covers 188,000 km2 and administratively consists of 11 prefecture-level cities (Figure 1). The climate of Hebei is characterized as a temperate continental monsoon. The province experiences arid and windy springs prone to sandstorms, summers of intense heat and torrential rains, crisp and temperate autumns, and frigid winters with minimal snowfall. Multi-year mean temperature reaches 11.8 °C, and precipitation exhibits a distinct southeast-to-northwest gradient. Cultivated land dominates the land use types in Hebei, followed by forestland and grassland. Hebei province had a permanent population of 74.6 million people and consumed 327.83 million tons of standard coal (2020), constituting over 68% of total energy consumption in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. This makes Hebei a critical area for carbon emission reduction within the area.

Figure 1.

Location of Hebei Province.

Hebei Province is not only a core area for the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration and air pollution joint prevention and control, but also a typical heavy industrial and energy base in China, facing urgent tasks of carbon emission reduction and high-quality development transition. Compared with regions with ample space for land incremental expansion, the land use changes in Hebei Province are more prominently reflected in the intensity improvement, efficiency optimization, and structural upgrading of stock construction land and agricultural land; that is, the ILUT exhibits prominent characteristics. Therefore, Hebei Province provides a suitable and policy-relevant typical case for empirically testing the carbon emissions of implicit land use transition at the county scale.

2.2. Research Approach

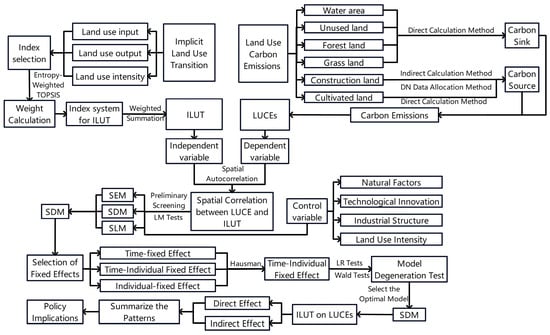

This study aims to break through the explicit constraints of land use type conversion, with Hebei Province as the research area and county-level units as the basic analysis scale. It focuses on investigating the spatial correlation mechanism between ILUT and carbon emissions. For carbon emission accounting, the carbon emission coefficient method can be adopted to quantify direct land-based emissions from cropland, woodland and other typical land types. Meanwhile, the nighttime light inversion method is applicable to estimate indirect carbon emissions from construction land, thus constructing a county-scale calculation system for LUCEs. Departing from the traditional composite index for ILUT evaluation, indicators are selected from the three dimensions of “input–output–intensity” and then standardized. Weights of these indicators are assigned via the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, followed by weighted summation to derive the comprehensive index of ILUT. In the spatial analysis stage, the global Moran’s I index is used to test the spatial correlation between ILUT and carbon emissions at the county level, which verifies the applicability of spatial econometric models for this research. The Lagrange multiplier (LM) test is further employed to preliminarily screen feasible spatial econometric approaches. Subsequently, the Hausman test is conducted to determine the choice between fixed and random effects. Finally, the likelihood ratio (LR) test and Wald test are utilized to judge whether the model degenerates and identify the optimal model specification. The technical roadmap of this study is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Technical Roadmap.

2.3. Data Sources and Preprocessing

Considering administrative division adjustments, data availability, and research needs, the work adopted the 2020 administrative divisions of Hebei Province as the benchmark. The municipal districts of each prefecture-level city in Hebei Province and the three counties of Xiong’an New Area were merged separately during data processing. Ultimately, 127 county units were delineated as analysis samples. Research data comprised multi-source information, including information on land use, meteorology, fundamental geography, and socio-economic factors (Table 1). Linear interpolation was utilized to address missing indices in some county units. Relevant spatial data were uniformly processed in terms of projection coordinate systems and spatial resolution. The land use data were sourced from the China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD) released by the team of Prof. Huang Xin from Wuhan University. This dataset includes nine land use types: Cropland, Forest, Shrub, Grassland, Water, Snow/Ice, Barren, Impervious, and Wetland. In accordance with relevant research [53], using ArcGIS 10.8.2, the land use data were reclassified into six categories: cultivated land, forest land, grass land, water area, construction land, and unused land. All raster data were uniformly projected to the CGCS2000_3_Degree_GK_Zone_39 projected coordinate system, with the spatial resolution uniformly resampled to 30 m.

Table 1.

Data sources.

2.4. Index Selection

2.4.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable of this study is LUCEs. Commonly used methods for carbon emission estimation include the bookkeeping model suitable for macro-scale accounting [56], the Input–Output Analysis focusing on carbon emission transfer associated with industrial linkages [57], and the carbon emission coefficient method characterized by simple operation [19]. Among these, the carbon emission coefficient method is the most commonly used and effective research method due to its clear principle, relatively easy access to data, and strong comparability of results [58]. Since it is relatively difficult to obtain county-level energy statistics data [6], it is challenging to directly measure the indirect carbon emissions from construction land at the county scale. In contrast, the nighttime light inversion method can effectively make up for the deficiency of incomplete county-level energy statistics data, and has become the core method for estimating indirect carbon emissions from construction land at the county scale, with its reliability having been verified [19]. Therefore, this study employs the carbon emission coefficient method and nighttime light inversion to measure LUCEs.

The carbon emission coefficient method is calculated by multiplying the area of a specific land use type by its corresponding carbon emission coefficient [58], where a positive coefficient corresponds to carbon sources (e.g., carbon emissions released from construction land and cultivated land) and a negative coefficient corresponds to carbon sinks (e.g., carbon absorption and fixation by forest land, grass land, water area, and unused land) [59]. Nighttime light inversion considers the correlation between nighttime lights and carbon emissions, using nighttime lights to invert the carbon emissions of a specific area [6]. LUCEs comprise direct as well as indirect carbon emissions [60]. Direct emissions originate proximately from land use changes; conversely, indirect emissions result distally from human production systems operating on those lands. The estimation formula is as follows.

where represents the LUCEs of the ith county; represents the sum of carbon emissions (or absorption) from grassland, cropland, forest land, unused land, and water bodies in the ith county; and represents carbon emissions from built-up land in the ith county.

- (1)

- Direct calculation method

Cultivated land, forest land, grass land, water area, and unused land are regarded as undeveloped land. Their mechanisms are clear and simple, and their carbon emission coefficients are relatively fixed [61]. Based on existing studies [58,62], the direct calculation method is adopted to calculate the carbon emissions of the aforementioned land use types. The specific formula is as follows:

where represents carbon emissions’ sum (or absorption) from unused land, water bodies, cropland, forest land, and grassland in the ith county; , , and represent ith land use type’s carbon emission amount, area, and carbon emission coefficient, respectively [58,62]. The carbon emission coefficients for different land use types are determined based on studies at the county scale of China and in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region [63,64,65,66]. The study areas of the selected literature are highly consistent with Hebei Province in terms of land use structure, climatic conditions, and county-level development characteristics. The specific coefficients and their corresponding sources are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Carbon emission coefficients for different land use types.

- (2)

- Indirect calculation method

Construction land’s carbon emissions primarily originate from energy consumption. Carbon emissions from provincial construction land can be estimated due to the incompleteness of energy data statistics. Considering the relationship between nighttime light and carbon emissions, nighttime light data can simulate carbon emissions from energy consumption as well as obtain carbon emissions from county construction land [19]. Therefore, nighttime light data from Hebei Province are utilized to estimate construction land’s carbon emissions across 127 counties in the province. Data are estimated by

where represents total carbon emissions from construction land in Hebei Province; represents the carbon emissions from the jth energy; represents the consumption of the jth energy; represents the standard coal conversion coefficient for the jth energy; and represents the carbon emission coefficient for the jth energy. The standard coal conversion coefficients are sourced from the Appendix of the China Energy Statistical Yearbook (2000–2020) published by the Development Research Center of the State Council of China. Carbon emission coefficients are strictly based on the technical specifications of the IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (2006) [55], and the standard emission coefficients for fossil fuel categories therein are adopted as the calculation basis. In addition, with reference to existing studies [67]. The standard coal conversion coefficients and carbon emission coefficients are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Standard coal conversion and carbon emission factors for energy sources.

Construction land’s carbon emissions in each county are estimated by

where represents construction land’s carbon emissions in the ith county; represents total carbon emissions from construction land in Hebei Province; and represents the entire nighttime light digital number (DN) of the ith county.

2.4.2. Independent Variables

The independent variable of this study is ILUT. Based on data availability, a comprehensive index system for ILUT is constructed from land use input, output, and intensity (Table 4) [15,68,69]. For input, the fixed asset investment per unit area targets industrial and urban land use. ILUT from extensive input to intensive refinement is reflected through capital investment scale per unit area. The local general public budget expenditure per unit area focuses on public services. The implicit upgrading of land’s supportive functions under stable patterns is presented via fund allocation in infrastructure development and ecological management.

Table 4.

Index system for ILUT.

For output, construction land’s GDP per unit area serves as a core indicator of land-use economic efficiency. It quantifies efficiency gains by measuring the variation in land’s economic output per unit. Per-unit-area total retail sales of consumer goods relate to commercial and residential land, reflecting the implicit optimization of living service functions via changes in consumption support capacity. Grain output per unit area concentrates on cultivated land. Differences in per-unit output indicate the implicit efficiency transformation of agricultural production functions. These three metrics correspond to the implicit output evolution in the economic, living, and production domains, aligning with the core of output-oriented implicit transformation.

For intensity, electricity consumption per unit area targets industrial and urban land. Dynamic changes in implicit energy consumption intensity are captured through energy use per unit area. Population density applies to urban and rural residential land, reflecting the implicit evolution of agglomeration pressure in spatial land use via population carrying capacity per unit area.

2.4.3. Control Variable

LUCEs are influenced by various factors [6,71]. Therefore, besides ILUT’s variables, elements affecting LUCEs are selected as control variables. The control variables of this study include natural factors, land use intensity, technological innovation, and industrial structure.

- (1)

- Natural Factors

Natural factors are one of the primary elements influencing the carbon sink capacity of counties [72]. The selected indices include the annual average normalized difference vegetation index, average yearly rainfall, as well as annual mean temperature, with weights of 0.130, 0.763, and 0.107, respectively. Entropy-weighted TOPSIS method is adopted to assess a comprehensive natural factor for counties in Hebei Province.

- (2)

- Land Use Intensity

Changes in land use types directly affect LUCEs, and land use intensity reflects the human disturbance level to some extent. According to the prevailing land use patterns in Hebei Province and related References [73,74], land use types are classified into four levels: Levels I-IV represent unused land, water bodies, forest land, grassland, cropland, and construction land, respectively. A higher comprehensive land use intensity index indicates greater intensity of land development and human activities within the area. Conversely, a lower index suggests lower land use intensity and fewer human activities. Land use intensity can be calculated as follows.

where represents the land use intensity’s comprehensive index; represents the graded index for the ith level; represents the land use type’s area for the ith level; represents the overall land extent; and represents the land use type’s level.

- (3)

- Technological Innovation

Technological innovation significantly impacts carbon emissions by enhancing production and energy structure or stimulating economic scale expansion. The number of newly patent applications and grants, high-tech industries, as well as registered enterprises are selected as indices, with the weights of 0.325, 0.366, and 0.309, respectively. Entropy-weighted TOPSIS method is employed to calculate the comprehensive technological innovation index for counties in Hebei Province [75].

- (4)

- Industrial Structure

Industrial structure is one of the core elements affecting carbon emissions. Energy consumption, along with carbon emission levels, is affected by differences in industry types, proportions, and internal structures. Industrial structure upgrading strengthens the positive contribution of energy technology to carbon efficiency. It is commonly measured through the share of GDP attributable to the secondary industry’s value added [76].

2.5. Research Methods

2.5.1. Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS Combined with Weighted Summation for Index Calculation

Entropy-weighted TOPSIS advances upon the traditional TOPSIS method, which is utilized to ascertain objective weights for the index decision matrix. This method has been widely adopted in various research fields due to its ease of application, strong comprehensiveness, and ability to avoid interference from subjective factors [70]. Therefore, to enhance the scientific reliability of the evaluation results for implicit land use morphology, the selected indicators for the implicit land use index are standardized. Weights are then assigned via the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, and finally, the comprehensive index of implicit land use transition (ILUT) is obtained through weighted summation, with a value range of (0, 1] [70,77]. A higher index value means higher land use input–output intensity, weaker low-carbon implicit transition, and higher carbon emission risk; a lower value means lower input–output intensity, more significant low-carbon transition, and stronger carbon control effect. As the value nears 0, the implicit characteristics of land use are stable, with a steady impact on carbon emissions. Dynamically, a sustained rise in the index slows low-carbon transition, and a sustained decline accelerates it.

2.5.2. Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel density estimation is a non-parametric estimation method. Data are used to describe the temporal evolution pattern of variables through a continuous density function [15]. The kernel density estimation method is employed to characterize the temporal features and evolution of ILUT (Equation (6)).

where represents the kernel density estimate of the ILUT index in the tth year when the index value is x; represents the sample number (N = 127), i.e., the number of county units; represents the bandwidth: larger results in a smoother curve, and smaller leads to a more rugged curve; represents the ith county unit’s ILUT index in the tth year; represents the target ILUT index of the kernel density estimated in the tth year; represents the kernel function, which assigns weight based on the standardized distance between the ILUT index of each county unit, as well as the target value. Discrete observed data are fitted into a continuous density curve, which supports the temporal distribution of the ILUT index [78].

2.5.3. Spatial Correlation Test

A spatial autocorrelation model shall be used to examine whether spatial association exists between ILUT and counties’ LUCEs in Hebei Province before applying spatial econometric models [15,79]. Global spatial autocorrelation is analyzed to investigate the ILUT’s spatial aggregation and LUCEs within the research area. The global autocorrelation test uses Moran’s I index (Equation (7)).

where represents county units’ number; as well as represent LUCEs or the implicit land-use index of county units and , respectively; represents the mean of LUCEs or the ILUT index across all county units; represents the variance of LUCEs or the ILUT index; and represents the spatial weight matrix, indicating the contiguity relationship between county units and . It takes 1 unit if and are adjacent, and 0 otherwise. I ranges between −1 and 1. > 0 indicates a positive spatial correlation in LUCEs or ILUT in Hebei Province; < 0 represents a negative spatial correlation; and = 0 represents no spatial correlation.

2.5.4. Spatial Econometric Model

From the perspective of spatial econometrics, ILUT affects LUCEs within the local county as well as neighboring counties [80]. Ignoring the spatial spillover effects of ILUT underestimates its impact on carbon emissions [81]. In light of this, the work treats ILUT as the explanatory variable and LUCE as the response variable. Spatial Durbin model (SDM), spatial lag model (SLM), as well as spatial error model (SEM) are constructed to explore ILUT’s spatial effects on LUCE. All variables are logarithmically transformed in regression estimation to address heteroscedasticity and reduce data volatility. The models are specified as follows.

where represents the ith county’s LUCEs in the tth year; represents the ith county’s ILUT in the tth year; signifies the ith county’s control variables in the tth year; represents the regression coefficient for spatially lagged term of the explanatory variable; and represent the regression coefficients of ILUT and its spatially lagged term, respectively; denotes the random disturbance term; represents the individual effect; represents the intercept term; and and represent the control variables’ regression coefficients, along with individual effects, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. LUCEs’ Spatiotemporal Evolution

3.1.1. Time-Varying Process Trend of LUCEs

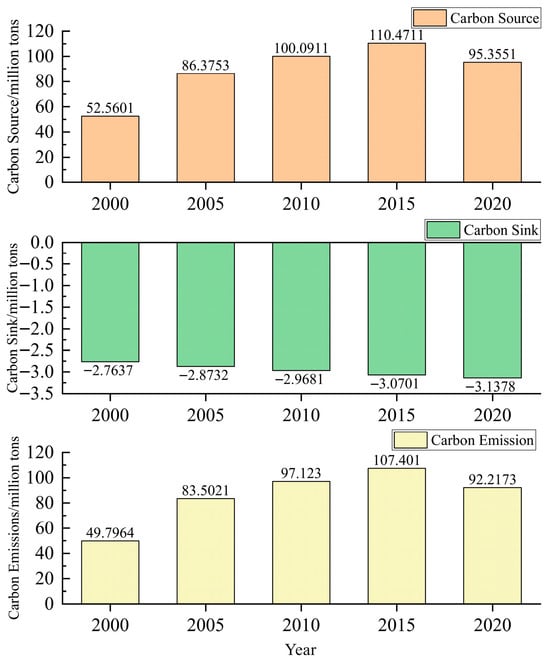

Origin 2022 was used to plot a bar-line hybrid graph of carbon emissions in Hebei Province (2000 to 2020) (Figure 3). The total carbon sink in Hebei Province was significantly smaller than its total carbon source from 2000 to 2020, meaning the province remained a net carbon source throughout this period. LUCEs first increased and then decreased. Carbon emissions increased from 49.80 to 107.40 million tons (a 116% growth) from 2000 to 2015. China experienced accelerated urbanization and industrialization during this period. Driven by these factors, Hebei Province presented continuous expansion of construction land, increased industrial production scale, and a sharp rise in energy consumption, which increased carbon emissions. Simultaneously, a significant amount of cultivated land was occupied. Cultivated land was taken as a carbon sink. The reduction in cultivated land area diminished its carbon sequestration and carbon absorption.

Figure 3.

LUCEs’ temporal evolution characteristics in Hebei Province.

The combined effect of one increase and one decrease jointly drove the substantial growth in overall carbon emissions. A persistent rise in cumulative emissions over the 2000–2015 period was concurrent with a diminishing annual growth rate during this period. Hebei Province progressively optimized its industrial structure and strictly implemented the emission reduction targets and tasks outlined in “The Opinion of the Hebei Provincial Government on Promoting Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction Work” (Ji Zheng [2008] No. 11). This process curbed regional carbon emissions’ growth. Carbon emissions decreased from 107.40 to 92.22 million tons (a reduction of 14.14%) from 2015 to 2020. This change was attributed to the systematic advancement of carbon emission reduction in Hebei Province. Emission reduction pathways were established from the production and energy consumption ends by transforming traditional industries and promoting clean energy and energy utilization. Meanwhile, the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated strategic plan’s proposal played a significant role in mitigating carbon emissions in Hebei Province. Hebei Provincial Government promoted the transition of industries toward green and low-carbon development by phasing out high-energy-consuming and high-polluting enterprises and raising environmental access standards within the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region during the process of industrial coordination and transfer. Therefore, a synergy for carbon reduction emerges, driven by policy and regional coordination.

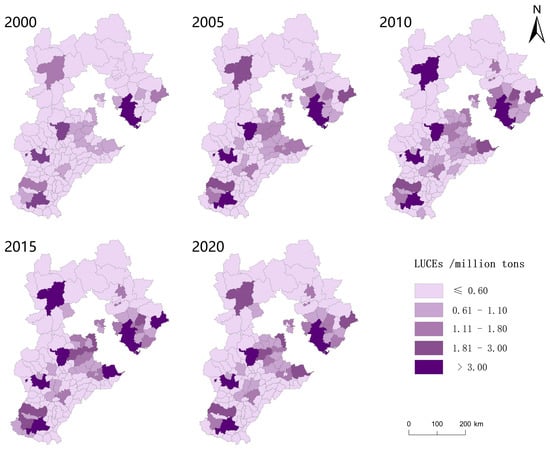

3.1.2. LUCEs’ Spatial Evolution Characteristics

LUCEs’ spatial distribution maps in Hebei Province for five years, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020, were produced through ArcGIS 10.8.2 (Figure 4). LUCEs of counties in Hebei Province were categorized into five levels: low carbon emission zone (≤0.60 million tons), medium-low carbon emission zone (0.61–1.10 million tons), medium carbon emission zone (1.11–1.80 million tons), high carbon emission zone (1.81–3.00 million tons), and ultra-high carbon emission zone (>3.00 million tons). Significant disparities in LUCEs of counties were observed across Hebei Province from 2000 to 2020, with higher emissions in the southeast and lower emissions in the northwest. Elevated carbon emission zones were concentrated within the main urban districts of various cities in Hebei Province. The quantity saw a sharp reduction.

Figure 4.

Spatial evolution of LUCEs of counties in Hebei Province.

Only the main urban area of Tangshan was an ultra-high carbon emission zone in 2000, with LUCEs reaching 3.0684 million tons. As a traditional heavy industrial base, the main urban area of Tangshan relies on pillar industries such as steel, coal, and building materials. These industries are energy-intensive, exhibiting prominent carbon emission intensity. Additionally, situated in a coastal area, the main urban area of Tangshan hosts high-frequency carbon emission industries (e.g., port logistics, shipping, and intra-port transportation), which elevate the total regional carbon emissions. However, counties (e.g., Fengning Manchu Autonomous County, Longhua County, and Chengde County) had negative carbon emissions. On one hand, the industrial structure of these counties is primarily supported by low-carbon industries such as characteristic agriculture and tourism. These industries have low energy consumption intensity as well as minimal carbon source emissions. Most of these counties are located in mountainous areas with high forest coverage and rich, diverse ecosystems. This significantly enhances the regional ecology’s carbon absorption capability, leading to prominent carbon sink functions.

Counties exhibiting negative carbon emissions decreased sharply in 2005–2015. Carbon emissions from land use in all counties significantly increased. The extent of reduced carbon emission zones shrank, whereas coverage of elevated carbon emission zones expanded. The main urban areas of cities such as Tangshan, Shijiazhuang, and Handan were classified as ultra-high carbon emission zones, each with carbon emissions exceeding 3 million tons. As core drivers of regional economic growth, these areas were characterized by high population density, heavy traffic, and the concentration of large industrial parks, which led to substantial energy consumption and intensified carbon emissions.

County-scale carbon emissions in Hebei Province had decreased significantly by 2020 compared to 2015. High and medium carbon emission zones shifted to medium-low and low carbon emission categories. The proportion of carbon-intensive zones declined, while the share of reduced carbon emission zones increased. Change could be influenced by the public health event at the end of 2019. China implemented lockdown restrictions, which led to factory shutdowns, people staying at home, and reduced economic activity. These factors subsequently reduced carbon emissions. Simultaneously, the government promoted industrial restructuring and encouraged low-carbon transitions. Hebei Province proactively advanced the low-carbon transition of its heavy industries and the development of clean energy to reduce carbon emissions.

3.2. ILUT’s Spatiotemporal Evolutionary Features

3.2.1. Temporal Sequence Evolution Properties of ILUT

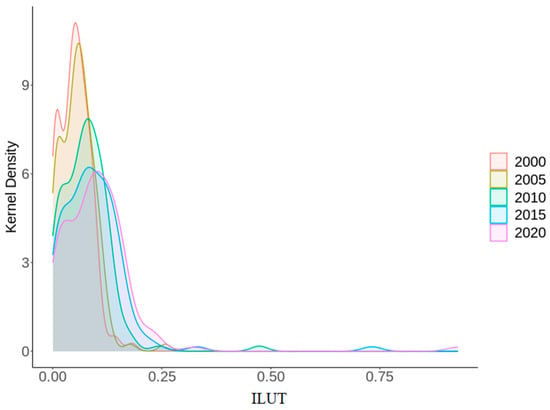

The Bioladder 2.0 platform (https://www.bioladder.cn/web/#/firstVue accessed on 21 September 2025) was used to plot the kernel density map of the comprehensive ILUT index of counties in Hebei Province from 2000 to 2020 (Figure 5). The ILUT index of counties in Hebei Province, indicating ILUT toward higher-order forms. However, the polarization disparity in ILUT widened due to differences in socio-economic development levels among counties. The index increased from 0.182 in 2000 to 0.925 in 2020.

Figure 5.

ILUT’s temporal behavioral patterns in Hebei Province.

The curve exhibited a bimodal pattern in 2000, with the main peak corresponding to the high concentration of traditional low-value land use. This aligned with the low-level homogenization of the province dominated by traditional agriculture at that time. Fixed capital stock per unit area, as well as local budgets, were generally low on input. Output relied heavily on agricultural cultivation and resource extraction, with slow growth in the land’s GDP per unit and consumer goods’ retail sales. Intensity showed relatively low electricity consumption per unit of land. Overall, the pattern reflected low input, low output, and low intensity. The secondary peak might be attributed to early explorations of new land use models, along with preliminary industrial investments or attempts at agricultural intensification in localized areas.

Economic development led to a rightward shift, a reduction in height, and a broadening of the main peak. A sharp peak transitioned to a broad and flat peak, accompanied by a lengthening tail. This transition stemmed from regional disparities in the synergy of input, output, and intensity. Langfang and Baoding, located around Beijing and Tianjin, leveraged opportunities from coordinated regional development for rapid growth in fixed asset investment and the general public budget. Tangshan capitalized on the expansion of its steel industry. Shijiazhuang enhanced its economic output through the development of a biomedical cluster, which significantly contributed to the overall index. In contrast, Zhangjiakou and Chengde in northern Hebei, constrained by their unique geographical locations and ecological function positioning, exhibited less pronounced economic growth. The persistent widening of these regional disparities broadened the curve.

The secondary peaks gradually disappeared between 2005 and 2020. These niche patterns were either integrated into mainstream models or diminished due to adjustments in development needs. This process reflected an overall increase in the composite index, the weakening of uniformity, and a shift toward diversified patterns. Ultimately, a high input–high output–high intensity cycle formed. Meanwhile, southern and northern Hebei encountered development bottlenecks, which elongated the curve’s tail. Overall, Hebei Province demonstrated a regional division characterized by coastal industry, plain agriculture, and mountainous ecology.

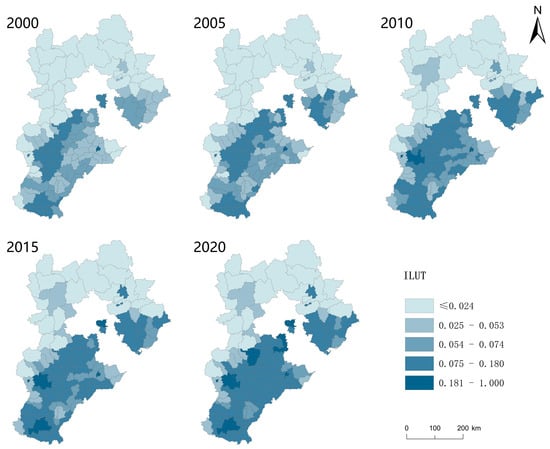

3.2.2. ILUT’s Spatial Evolution Features

Based on ILUT’s comprehensive evaluation of counties in Hebei Province, the spatial evolution from 2000 to 2020 was mapped using ArcGIS 10.8.2 (Figure 6). ILUT levels for each year were uniformly categorized into five tiers: low (≤0.024), medium-low (0.025–0.053), medium (0.054–0.074), medium-high (0.075–0.180), as well as high (0.181–1.000).

Figure 6.

Spatial evolution of ILUT in Hebei Province.

ILUT of counties in Hebei Province exhibited a pattern that displayed a distinct northwest-southeast gradient, with values increasing toward the southeast from 2000 to 2020. ILUT gradually evolved from isolated high-value single-core clustering to multi-core high-value clustering in the southeast. The northwest consistently remained at a relatively low level.

The high-value area for ILUT was the main urban area of Cangzhou City between 2000 and 2005 due to its high economic development level and relatively small area. Medium-high values formed a belt-shaped spatial feature of Zhuozhou City, Baoding City’s main urban area, Shijiazhuang City’s main urban area, and Longyao County, as well as a planar spatial feature centered around Cheng’an County. Shijiazhuang, leveraging its natural geographical advantages and status as the provincial capital, experienced sustained and rapid economic growth by 2010. Thus, its main urban area rose from medium-high to high value. A planar spatial structure with new medium-high values emerged, centered around the main urban area of Tangshan. Counties’ number exhibiting reduced values dropped from 2015 to 2020, concentrated in the northwest. High-value counties increased significantly, primarily distributed in the main urban areas of cities. Medium-high-value counties showed a slight increase, exhibiting a large-scale areal spatial distribution in the southeastern region.

3.3. Impact of ILUT on LUCEs

3.3.1. Spatial Autocorrelation Test

Spatial correlation was an essential requirement for spatial econometric analysis. Using software GeoDa 1.22, a global autocorrelation analysis was conducted for ILUT and LUCEs of counties in Hebei Province (Table 5). The global Moran’s I indices for total variables were positive and passed 1% significance degree test. ILUT and LUCEs exhibited significant positive spatial autocorrelation. Therefore, an econometric spatial model was employed to examine ILUT’s spatial effects on LUCEs.

Table 5.

Global Moran’s I Indices and related metrics for ILUT and LUCEs.

3.3.2. Selection of Econometric Spatial Model

The work employed multiple diagnostic procedures to identify an appropriate spatial econometric specification for examining ILUT’s impact on LUCEs (Table 6). The spatial autocorrelation test results indicated that both ILUT and LUCEs exhibited significant positive spatial autocorrelation. Spatial dependence in dependent as well as independent factors invalidated ordinary least squares regression. Further LM tests reached significance at 1% level, indicating that an SEM, SLM, or SDM should be employed for subsequent analysis.

Table 6.

Test results for selecting the spatial econometric model.

A Hausman investigation was performed to explore the appropriate model specification. Findings passed the threshold (p < 0.01), supporting a fixed-effect specification. Subsequently, an LR test was performed to select fixed effects. Given the statistical significance (p < 0.01) of both the individual and time effects, a model with two-way fixed effects was adopted. Finally, employing an SDM was verified using the LR and Wald tests. Both tests were significant at the 1 and 5% levels, respectively, confirming simpler SLM and SEM specifications were rejected in favor of the more general SDM. Therefore, an SDM exhibiting two-way (individual and time) fixed effects was ultimately selected for empirical analysis.

3.3.3. Regression Results

Based on the spatial econometric model and the maximum likelihood estimation method, parameter estimation was conducted to analyze the impact of ILUT on LUCEs of counties in Hebei Province from 2000 to 2020. The SDM demonstrated a high log-likelihood value and satisfactory adjusted R2 (Table 7), indicating excellent model fit to sample data. These findings thus validated the model as a suitable tool for examining the relationship between the two variables. The explained variable’s spatial lag term was positive at the 1% level in models (2) and (4), with coefficients exceeding 0.248. LUCEs across counties had a marked positive spatial spillover. ILUT’s coefficient was consistently positive at the 1% level in all models. However, the spatial lag term of ILUT in the SDM was significantly negative. ILUT had a positive spatial correlation with LUCEs in the county. Besides, a significant negative spatial spillover effect was identified on neighboring counties’ LUCEs.

Table 7.

Spatial econometric model’s regression results.

3.3.4. Effect Decomposition

SDM’s results revealed that the ILUT generated significant spillovers to LUCEs. However, the model regression results’ estimated coefficients might be biased by spatial spillover effects. These coefficients reflected the direction and significance of the effects, instead of the marginal effect intensity of the ILUT on LUCEs. Therefore, the partial differential method introduced by Lesage et al. was applied to decompose the total effect into direct effects as well as indirect spillover effects (Table 8).

Table 8.

Decomposition of spatial effects based on the SDM.

ILUT’s direct effect, along with spatial spillover effect coefficients, were 0.448 as well as −0.331, respectively, statistically significant at the 1% level. A 1% rise in ILUT was associated with a 0.448% increase in local county carbon emissions, while carbon emissions in neighboring counties decreased by 0.331%. This indicates that Research Hypothesis H1 (the negative direct effect of ILUT on local carbon emissions) is not empirically supported, while Hypothesis H2 (ILUT exerts a spatial spillover effect on carbon emissions in neighboring counties) is valid. The local county did not demonstrate the low-carbon benefits of ILUT; however, spatial redistribution of carbon emissions was achieved through the regional division of work. Counties exhibited core-periphery characteristics or a specialized division of work in socioeconomic development. This differentiation directly led to divergent carbon effects from ILUT. Specifically, land use in the local county transitioned from extensive expansion to intensive efficiency. As a result, the quantitative growth rate in carbon emissions outpaced the emission reduction effects of qualitative improvement, ultimately manifesting as a positive direct effect in the local county. The reduction in carbon emissions in neighboring counties might be driven by ILUT in the local county, which promoted the allocation of regional factors through spatial linkages. For instance, the local county might transfer energy-intensive production processes to neighboring counties. These neighboring counties achieved scale economies by absorbing such industries, which lowered carbon emissions per unit of output. Therefore, future policies should emphasize differentiated county strategies (e.g., promoting low-carbon technologies locally and coordinating regional carbon quota mechanisms) to balance transition with emission reduction.

Regarding the control variables, the direct effect coefficient was 0.595 for natural factors while the spatial spillover effect coefficient was −1.817, which both positive at the 1% level. Natural factors exhibited a strongly positive direct correlation with carbon emissions within the county, as well as a markedly negative spatial spillover effect on carbon emissions in neighboring counties. Similarly, the coefficients for the direct and spatial spillover effects of land use mix were 1.189 and −2.959, respectively, significant at the 1% level. Land use mix presented a pronounced positive direct effect on carbon emissions within the county, as well as a significant negative spatial spillover effect on neighboring counties’ carbon emissions. Technological innovation’s direct effect and spatial spillover effect coefficients were 0.209 and 0.076, respectively. Direct effect passed the significance test at the 5% level, while the indirect spillover effect passed at the 10% level. The slightly insufficient technological innovation capacity in counties hindered carbon emission reduction in the local county as well as adjacent counties. Industrial structure’s direct and spatial spillover effect coefficients were 0.486 as well as 0.391, respectively. Direct effect was significant at the 10% level, whereas the spatial spillover effect was not statistically significant. The current industrial structure was unfavorable for carbon emission reduction in the local county.

3.3.5. Robustness Tests

Three methods were employed for robustness testing to ensure the robustness of the model estimation presented earlier. First, the spatial weight matrix was replaced. Spatial adjacency matrix overlooked the geographical distance’s influence on LUCEs. A spatial distance weight matrix was incorporated into the estimation (model (1) in Table 9) to account for the sensitivity of ILUT’s carbon emission effects to the spatial distance between counties. Second, winsorization was applied. All variables were winsorized at the 1% level to mitigate the influences of extremums and outliers in panel data on the analysis results. Observations below 1% were replaced with the value at 1%, while those above 99% were replaced with the value at 99%. This approach ensured robust adjustments for extreme fluctuations in data (model (2) in Table 9). Third, biased samples were excluded. Samples from central urban districts of cities and the Xiong’an New Area were removed for estimation (model (3) in Table 9) to address potential biases arising from economic and social development disparities between counties. Based on the robustness test, the direction and significance of the spatial effects of ILUT on LUCEs of counties in Hebei Province remained largely consistent with the previous findings. The result confirmed the robustness of the empirical analysis.

Table 9.

Robustness test results.

4. Discussion

Carbon emissions of ILUT of counties in Hebei Province were examined from a spatial econometric perspective. Temporal and spatial dimensions were used to characterize ILUT and LUCEs. The spatial relationship between ILUT as well as LUCEs was revealed to explore ILUT’s local and spatial spillover impacts on LUCEs. Existing research on land use transitions’ carbon emissions focuses on the explicit dimension. The work advanced relevant theoretical frameworks by introducing ILUT to analyze its intrinsic impact on LUCEs.

The findings of the work are consistent with relevant existing research. Regarding LUCEs, LUCEs in Hebei Province exhibit distinct phase characteristics [82]. The temporal evolution of LUCEs consists of two phases: an initial stage (1995–2015) shows significant growth, while the second phase (2015–2020) exhibits a slight decline. These findings further solidify the understanding of the spatiotemporal evolution of LUCEs in Hebei Province, providing strong evidence for the carbon reduction effectiveness of national dual-carbon policies [83] and regional industrial restructuring post-2015 [84]. This powerfully demonstrates the practical value of policy guidance and development model transformation in regional carbon emission governance [85]. This pattern aligns with the observations of the work. In terms of ILUT, the ILUT level slowly grew from 2005 to 2020 [86]. The ILUT index of counties in Hebei Province increases during the study period, indicating a progression toward higher-level development. This finding corroborates the conclusions of related studies. This result confirms a steadily intensifying ILUT pattern at the county level, reflecting optimized land use input structures, improved output efficiency, and regulated use intensity across Hebei Province. It provides substantial evidence at the county level for understanding the spatiotemporal dynamics of high-quality regional land use transition, while highlighting the intrinsic synergy between socioeconomic development and co-evolution within the land use system [87].

Spatial autocorrelation tests reveal that LUCEs and ILUT exhibit significantly positive spatial autocorrelation. Land use behaviors exhibit significant spatial dependence across counties [43], contingent on their geographic locations and inherent land use characteristics [88]. This conclusion aligns with Zhang et al.’s findings [15]. Unlike previous studies employing traditional econometric models, spatial lag and error dependence terms are incorporated to account for ILUT’s spatial impact on carbon emissions. Urban-land green transition significantly suppresses local carbon emissions while exerting positive spatial spillover effects on adjacent cities [89]. Conversely, the urban-land green transition’s influence on carbon emissions varies across areas. In their study, the direction of the direct effect is consistent with Hypothesis H1 of this research, and the spatial spillover effect aligns with the core prediction of Hypothesis H2. However, the empirical results of this study indicate that Hypothesis H1 is not supported, while Hypothesis H2 is validated—specifically manifesting as a negative spatial spillover effect. this conclusion highlights the regional specificity and mechanistic heterogeneity in the carbon emissions of ILUT. Counties in Hebei Province face deep-rooted path dependency on traditional industries, low efficiency in resource allocation, and difficulties in integrating diverse development models. Outdated patterns and insufficient cultivation of emerging green drivers may lead to carbon emissions distinct from those observed in urban green transitions during the process of ILUT. Essentially, the approach of alleviating land resource pressure by transferring production activities across regions is a spatial shift in resource conflicts, lacking long-term sustainability [90]. Thus, carbon emission effects are distinct from those of urban green transformation. Counties in Hebei need to explore transition pathways tailored to their unique resource endowments and industrial foundations. The following measures should be performed to follow a green development as well as dual-carbon goals, including breaking down barriers to factor mobility, accelerating the integration of green technologies into traditional land use, and establishing inter-county collaborative transition networks.

The findings clarify ILUT’s effect on carbon emissions. According to the quantified direct as well as indirect effects of this transition in Hebei Province, the following policy recommendations are proposed to guide governmental land use regulation.

- (1)

- Optimize the input structure of the implicit transition to consolidate the foundation for low-carbon development. Concentrate on implicit investment in industrial/urban land by creating a low-carbon-driven capital allocation mechanism. Shift fixed-asset investment from traditional high-carbon sectors (e.g., steel and chemicals) towards clean energy (e.g., PV and wind) and energy-efficiency technologies. Integrate carbon intensity per unit of investment into the project approval process to limit investment-driven carbon growth at the source [91]. Boost spending on low-carbon public services (e.g., parks, woodlands, and green transport) [92]. Tie budget expenditures to regional carbon intensity reduction goals to check the implicit spread of high-carbon public projects.

- (2)

- Increase land use output efficiency to advance low-carbon value realization. Cap carbon emissions per unit of GDP to drive industries toward sustainable and smart upgrades, for example, by cultivating digital and circular economies. This decouples land-use GDP growth from carbon emissions [30]. Guide commercial land use toward low-carbon consumption scenarios (e.g., green malls) and promote subsidies for low-carbon products [93]. Upgrade consumption models to reduce the carbon footprint of retail sales growth per unit of land. Implement eco-agricultural technologies to lower agricultural carbon intensity while maintaining stable grain output [39] to achieve both high yield and low carbon goals.

- (3)

- Manage intensity thresholds to curb high-carbon, low-efficiency sprawl. Set low-carbon redlines for electricity use per unit of industrial/urban land and cap approvals for high-energy-use projects in exceedance areas. Boost distributed solar/wind power to cut carbon from energy use per unit of land [94]. Steer urban population distribution to avoid overcrowding. Build low-carbon communities in dense areas to prevent sprawl-related emissions. Control per capita carbon intensity via compact development, green space integration, and upgrades like district heating and smart, efficient buildings [25].

- (4)

- Spatial spillover effects facilitate collaborative governance to block carbon emissions’ transfer to neighboring areas. Establish a regional platform for sharing investment information and implement a joint review mechanism for cross-county high-carbon investment projects. This prevents the relocation of high-carbon industries from counties with strict emission reduction policies to neighboring areas, achieving regionally coordinated low-carbon investment steering. Create a coordinated regional low-carbon fiscal mechanism to provide cross-regional financial support to counties developing carbon sink forests or low-carbon infrastructure in neighboring areas. Thus, the positive spillover effects of public budgets are amplified. Define county-specific low-carbon industrial positioning based on regional resource endowments to avoid homogeneous competition in high-carbon industries and reduce overall regional emissions through industrial specialization. Implement an ecological compensation mechanism between primary grain production areas and consumption areas [95]. Offer cross-regional payments to major grain-producing counties adopting low-carbon farming techniques. This controls the spatial spillover of agricultural carbon emissions while ensuring food security. Develop an early warning system for regional energy consumption. For areas where electricity use per unit land in neighboring regions exceeds standards and poses a spillover risk, initiate cross-regional clean energy allocation to curb the spatial spillover of high energy consumption. Optimize population density distribution at the city cluster and metropolitan area level. Guide rational population flow through the equalization of regional public services. Prevent the spatial transmission of carbon emissions caused by excessive population concentration in any single county.

Several limitations exist in the work. First, the accuracy of the method used to estimate LUCEs is constrained by factors such as energy allocation, utilization efficiency, and technological levels, leaving room for improvement. Second, nighttime light data are used to inversely examine counties’ carbon emissions due to the lack of county data. Although some researchers have demonstrated the feasibility of this approach, discrepancies with actual values remain. Finally, the evaluation indicator system of ILUT developed in the work serves as an exploratory attempt. It does not encompass comprehensive measurement across all dimensions but rather selects key dimensions for assessment. Future research will employ more robust methodologies and data sources to enhance the accuracy of such studies.

5. Conclusions

Counties in Hebei Province were taken as the study units to estimate LUCEs, measure the ILUT index, and investigate the spatial relationship between ILUT and LUCEs. The investigation of ILUT’s direct and spillover effects on LUCEs was performed via spatial econometric modeling. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows.

- (1)

- LUCEs in Hebei Province first increased and then decreased. Emissions increased from 49.80 (2000) to a peak of 107.40 million tons (2015), marking a significant increase of 115.68%. Subsequently, they declined to 92.22 million tons by 2020, a decrease of 14.14% from the peak in 2015. Significant disparities existed in LUCEs across counties. A distinct southeast-northwest gradient was observed, with the southeast exhibiting higher emission levels along with lower emissions within the northwest. Zones with high carbon emissions were agglomerated in various cities’ main urban areas.

- (2)

- The ILUT level in the counties of Hebei Province increased steadily. The polarization disparity in ILUT among counties widened, rising from 0.182 in 2000 to 0.925 in 2020. The spatial distribution of ILUT across counties was characterized by lower levels in the northwest and higher levels in the southeast. The pattern of ILUT evolved from a single-core cluster with isolated high values to a multi-core cluster with high values in the southeastern counties. In contrast, the northwestern counties remained at relatively lower levels.

- (3)

- Both ILUT and LUCEs exhibited significant spatial correlation among counties in Hebei Province. ILUT had a significantly positive direct as well as a negative spatial spillover effect on LUCEs. A positive spatial correlation exists between ILUT as well as land use-related carbon emissions within the county, while a negative spatial correlation exists with land use-related carbon emissions within neighboring counties.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, W.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Z.Z., L.Z., G.Z. and P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Social Science Foundation of Hebei Province, China (Grant No. HB23GL014).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Infante-Amate, J.; Travieso, E.; Aguilera, E. The history of a+ 3 °C future: Global and regional drivers of greenhouse gas emissions (1820–2050). Glob. Environ. Change 2025, 92, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Deng, K.; Dong, Z.; Meng, X.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, S.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y. Comprehensive assessment of land use carbon emissions of a coal resource-based city, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Burney, J.A.; Pongratz, J.; Nabel, J.E.; Mueller, N.D.; Jackson, R.B.; Davis, S.J. Global and regional drivers of land-use emissions in 1961–2017. Nature 2021, 589, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Xin, C.; Zhang, B.; Xin, S.; Tang, D.; Chen, H.; Ma, X. Contribution of multi-objective land use optimization to carbon neutrality: A case study of Northwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 157, 111219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivhenge, E.; Mabaso, A.; Museva, T.; Zingi, G.K.; Manatsa, P. Zimbabwe’s roadmap for decarbonisation and resilience: An evaluation of policy (in) consistency. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 82, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tong, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Yao, Y. Heterogeneity study on mechanisms influencing carbon emission intensity at the county level in the Yangtze River Delta urban Agglomeration: A perspective on main functional areas. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, G.; Bi, M.; He, B.J. Carbon surplus or carbon deficit under land use transformation in China? Land Use Policy 2024, 143, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillouin, D.; Cardinael, R.; Berre, D.; Boyer, A.; Corbeels, M.; Fallot, A.; Feder, F.; Demenois, J. A global overview of studies about land management, land-use change, and climate change effects on soil organic carbon. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 1690–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, A.S. Global Trends in Forest Resources. Geography 1987, 72, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, A.S. The forest transition. Area 1992, 24, 367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.L.; Li, X.B. Analysis on regional land use transition: A case study in Transect of the Yangtze River. J. Nat. Resour. 2002, 17, 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H. Theorizing land use transitions: A human geography perspective. Habitat Int. 2022, 128, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Tu, S. Land use transitions: Progress, challenges and prospects. Land 2021, 10, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Qu, Y. Land use transitions and land management: A mutual feedback perspective. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ke, X. The study on spatial correlation of recessive land use transformation and land use carbon emission. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Long, H.; Ge, D.; Xu, L.; Li, S. Study on three-dimensional measurement of recessive farmland use morphology and its regional types: A case of the Huang-Huai-Hai Region. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Dong, Z.; Wu, P.; Dong, F.; Fang, K.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Shao, Z.; Yu, Z. How urban land-use intensity affected CO2 emissions at the county level: Influence and prediction. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, M.N.; Fang, R.Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q. Spatial-temporal characteristics of carbon emissions from land use change in Yellow River Delta region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hu, S.; Wu, S.; Song, J.; Li, H. County-level land use carbon emissions in China: Spatiotemporal patterns and impact factors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Qiu, X.; Zhou, C. Carbon emission and economic development trade-offs for optimizing land-use allocation in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 109950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubacek, K.; Chen, X.; Feng, K.; Wiedmann, T.; Shan, Y. Evidence of decoupling consumption-based CO2 emissions from economic growth. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 4, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A.; Tuspekova, A. The nexus between economic growth, renewable energy use, agricultural land expansion, and carbon emissions: New insights from Peru. Energy Nexus 2022, 6, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.; Rafiq, M.; Shafique, M.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, J. Analyzing the effect of natural gas, nuclear energy and renewable energy on GDP and carbon emissions: A multi-variate panel data analysis. Energy 2021, 219, 119592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Bao, Z.; Ng, S.T.; Song, W.; Chen, K. Land-use carbon emissions and built environment characteristics: A city-level quantitative analysis in emerging economies. Land Use Policy 2024, 137, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.A.; Shah, S.Q.A.; Tahir, M. Determinants of CO2 emissions: Exploring the unexplored in low-income countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 48276–48284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Meng, T.; Kharuddin, S.; Ashhari, Z.M.; Zhou, J. The impact of renewable energy consumption, green technology innovation, and FDI on carbon emission intensity: Evidence from developed and developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 483, 144310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, R.; Song, Y.; Shen, M.; Xiang, R. Carbon emissions, the industrial structure and economic growth: Evidence from heterogeneous industries in China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Wang, S. Mechanism of regional land use transition in underdeveloped areas of China: A case study of northeast China. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.A.; Griffith, G.E.; Auch, R.F.; Stier, M.P.; Taylor, J.L.; Hester, D.J.; Riegle, J.L.; McBeth, J.L. Understanding recurrent land use processes and long-term transitions in the dynamic south-central United States, c. 1800 to 2006. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avashia, V.; Garg, A. Implications of land use transitions and climate change on local flooding in urban areas: An assessment of 42 Indian cities. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P. Land use transitions: Socio-ecological feedback versus socio-economic change. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, R.E.; de Magalhães, L.P.; de Souza Gallo, A.; de Oliveira, J.A.; Sais, A.C. Land use transitions and the decline of family farming in Southeastern Brazil: Patterns, pressures, and environmental trade-offs. Land Use Policy 2025, 159, 107802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Qu, Y.; Tu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Development of land use transitions research in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhao, B.; Lu, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Z. Spatially explicit carbon emissions from land use change: Dynamics and scenario simulation in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. Land Use Policy 2025, 150, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Tang, Z.; Mei, Z. Urbanization, land use change, and carbon emissions: Quantitative assessments for city-level carbon emissions in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 66, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubiello, F.N.; Conchedda, G.; Wanner, N.; Federici, S.; Rossi, S.; Grassi, G. Carbon emissions and removals from forests: New estimates, 1990–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafy, A.A.; Saha, M.; Fattah, M.A.; Rahman, M.T.; Duti, B.M.; Rahaman, Z.A.; Bakshi, A.; Kalaivani, S.; Rahaman, S.N.; Sattar, G.S. Integrating forest cover change and carbon storage dynamics: Leveraging Google Earth Engine and InVEST model to inform conservation in hilly regions. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 152, 110374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Wu, Y.; Cui, H.; Lu, X. The mechanisms and spatial-temporal effects of farmland spatial transition on agricultural carbon emission: Based on 2018 counties in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 107716–107732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, N.; Tizado, E.J.; zu Ermgassen, E.K.; Löfgren, P.; Börner, J.; Godar, J. Spatially-explicit footprints of agricultural commodities: Mapping carbon emissions embodied in Brazil’s soy exports. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 62, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, H. Spatiotemporal dynamic decoupling states of eco-environmental quality and land-use carbon emissions: A case study of Qingdao City, China. Ecol. Inf. 2023, 75, 101992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, J.; Yang, T.; Ding, T. Spatial and temporal evolution characteristics and spillover effects of China’s regional carbon emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, T.; Das, A. Urbanization induced changes in land use dynamics and its nexus to ecosystem service values: A spatiotemporal investigation to promote sustainable urban growth. Land Use Policy 2024, 144, 107239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabska-Szwagrzyk, E.; Khiabani, P.H.; Pesoa-Marcilla, M.; Chaturvedi, V.; de Vries, W.T. Exploring land use dynamics in rural areas. An analysis of eight cases in the Global North. Land Use Policy 2024, 144, 107246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.; Pace, R.K. Introduction to Spatial Econometrics; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Liu, C. Regional disparity, spatial spillover effects of urbanisation and carbon emissions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Lv, Z. Spillover effects of economic globalization on CO2 emissions: A spatial panel approach. Energy Econ. 2018, 73, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnazi, R.; Dehghan Shabani, Z. The effects of spatial spillover information and communications technology on carbon dioxide emissions in Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 24198–24212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, K.; Yan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Liao, L.; Chen, Y. Urban land use transitions and the economic spatial spillovers of central cities in China’s urban agglomerations. Land 2021, 10, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, X. Inhibit or promote: Spatial impacts of multifunctional farmland use transition on grain production from the perspective of major function-oriented zoning. Habitat Int. 2024, 152, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, X.; Song, Y.; Sun, R. The spatial impacts of multifunctional farmland use transition on the urban-rural income gap: A major function-oriented zoning perspective. Cities 2025, 167, 106385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Yang, C.; Wang, M.; Failler, P. Heterogeneous impact of land-use on climate change: Study from a spatial perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 840603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wang, C.; Zou, Y.; Han, Z.; Zou, G. Multi-scale spatiotemporal interactions between land use transformation and carbon emissions in China from 1980 to 2020. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2026, 226, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.Q.; Xu, Z.J. Analysis on the spatio-temporal evolution of ecological security patterns: A case study over Taiyuan Urban Agglomeration. China Environ. Sci. 2023, 43, 5987–5997. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. 30 m annual land cover and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2021, 2021, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleston, H.S.; Buendia, L.; Miwa, K.; Ngara, T.; Tanabe, K. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Hayama, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, A.; Hartung, K.; Nützel, T.B.; Nabel, J.E.; Houghton, R.A.; Pongratz, J. Comparison of uncertainties in land-use change fluxes from bookkeeping model parameterization. Earth Syst. Dyn. Discuss. 2021, 2021, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, R.; Benders, R.M.; Moll, H.C. Measuring the environmental load of household consumption using some methods based on input–output energy analysis: A comparison of methods and a discussion of results. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 2744–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, M.; Xue, J. The role of land use landscape patterns in the carbon emission reduction: Empirical evidence from China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cai, Z.; Song, W.; Yang, D. Mapping the spatial-temporal changes in energy consumption-related carbon emissions in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region via nighttime light data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 94, 104476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, H.; Hou, H.; Xu, C.; Sun, L.; Li, Q.; Ren, J. Spatiotemporal evolution and multi-scale coupling effects of land-use carbon emissions and ecological environmental quality. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, D.; He, H.; Liu, C.; Han, S. Spatio-Temporal dynamic evolution of carbon emissions from land use change in Guangdong Province, China, 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chen, L.; Tong, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Yuan, L.; Xiao, J.; Wu, R.; Bai, L.; et al. Spatial correlations of land-use carbon emissions in the Yangtze River Delta region: A perspective from social network analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liang, H.; Chang, X.; Cui, Q.; Tao, Y. Land use patterns on carbon emission and spatial association in China. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 35, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Yin, X.; Wei, H. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Factors of the Relationship Between Land Use Carbon Emissions and Ecosystem Service Value in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. Land 2025, 14, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Bai, X.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, G.; Li, J.; Ran, C.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, L.; Liao, J.; Du, C.; et al. Global impacts of land use on terrestrial carbon emissions since 1850. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 963, 178358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z. Spatial correlation evolution and prediction scenario of land use carbon emissions in China. Ecol. Inf. 2022, 71, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Guo, X.; Zhao, S.; Yang, H. Variation of net carbon emissions from land use change in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region during 1990–2020. Land 2022, 11, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.H.; Chen, S.L.; Du, F.Y. Factors Influencing Recessive Transformation of Land Use in Fujian Province During 2000–2020. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 43, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]