Abstract

The Paraguayan spatial planning system is analyzed through its legal framework, institutional structure, and implementation mechanisms, placing it within the Latin American context marked by fragmented governance and institutional inequality. Based on a review of laws and planning instruments at the national, departmental, and municipal levels, this study examines the system’s evolution, with particular focus on the period from the consolidation of the constitutional framework to the formulation of recent policies promoting sustainable development, decentralization, and democratic decision-making. The findings show a process of partial institutionalization, where norms and methodologies advance more rapidly than operational and financial capacities, resulting in uneven implementation across regions. Ongoing challenges include regulatory fragmentation, overlapping responsibilities, and weak multilevel coordination. Enhancing institutional coherence, prioritizing planning instruments, and strengthening subnational technical capacities are key to achieving a coherent and equitable spatial planning system that integrates international cooperation and translates sustainability and equity principles into practical dimensions of territorial governance.

1. Introduction

Governance and spatial planning systems in Latin American countries show structural weaknesses at the institutional, legal, and operational levels, accounting for many of the persistent challenges in territorial management across the region [1]. The implementation of territorial policies has evolved in a context of contrasts and varying degrees of political maturity compared with European or other Western countries, which is further influenced by a late industrialization process that has shaped institutional structures, development priorities, and state planning capacity [2]. These dynamics are further intensified by prolonged transitions from colonial land tenure regimes and Indigenous practices to state-led modernization models and market-oriented reforms [3,4,5,6].

Currently, Latin American systems of territorial governance are characterized by the instability and ambiguity of their institutional structures, limited citizen participation in decision-making processes, and a lack of political will to acknowledge and implement effective spatial planning [7]. Planning systems in the region are deeply shaped by colonial legacies and post-colonial reforms, whose combined effects create a planning environment characterized by institutional hybridity, informality, and persistent sociopolitical contestation. This context differs significantly from the planning systems of the Global North [8].

Within this broad territorial context—characterized by challenges common to spatial planning [9], conflicts arising from rapid urbanization and territorial fragmentation [10], institutional fragilities and reactive planning mechanisms [11], and pronounced political centralization [12]—it becomes imperative to examine the institutional framework that underpins both the normative foundations and the territorial model. Such an examination is essential for the effective design, implementation, and governance of spatial planning processes in Latin American countries.

In Paraguay, the spatial planning framework has been profoundly shaped by historical legacies of unequal land tenure, incomplete agrarian reforms, and the rapid expansion of agro-industrial frontiers [13]. These structural conditions render Paraguay a pertinent case for investigating both the constraints and prospects for consolidating territorial governance and spatial planning systems within the Latin American context [3,14,15,16,17]. In this regard, the present study offers a detailed analysis of the regulatory framework and planning instruments, along with an updated contribution to the understanding of territorial governance in Paraguay. Accordingly, this study provides a comprehensive perspective on how spatial planning operates in Paraguay within a context marked by institutional hybridity and limited development of comparative spatial planning research [8].

This article provides a critical review of the evolution and consolidation of Paraguay’s spatial planning system, with particular attention to the institutionalization of its spatial planning apparatus. In line with broader scholarship on spatial planning and territorial governance in Latin America, the analysis is grounded in the premise that the establishment and operationalization of robust institutions are central to fostering a democratic state that guarantees citizens’ rights and promotes equitable resource distribution [18]. Accordingly, effective territorial governance, which involves institutions coordinating their actions with the aim of aligning the spatial or territorial impacts of sectoral policies, should be guided by democratic, collaborative, and territorially integrated strategies [19].

From this perspective, the article addresses two primary research questions:

- How has the spatial planning system evolved in Paraguay?

- What are the main political and institutional characteristics and challenges of the Paraguayan spatial planning system?

The relevance of this study is further justified by the historically palliative, rudimentary, and provisional nature of spatial interventions in Paraguay, which has resulted in the absence of mechanisms and instruments capable of defining a coherent territorial model [20]. Furthermore, the situation is exacerbated by the predominance of a clearly hierarchical (top-down) planning approach and the lack of structured mechanisms for citizen participation [9]. These factors reinforce the perception of structural fragility in planning systems, providing insight into how countries organize their planning institutions, maintain the balance between the State and the market, and allocate territorial (universal) rights and values [21,22,23].

Additionally, the overlap of visions and competencies, as well as the complexity of processes for approving public policies, impedes spatial planning due to insufficient coordination and institutional inertia [24,25]. In this context, effective spatial planning should ensure not only social well-being and equity [26] but also the harmonization of legal and institutional frameworks across all levels of government [22,25].

2. Institutional Design and Structure of the Spatial Planning System

The study of spatial planning systems has generated multiple lines of analysis, ranging from national interpretative frameworks to supranational comparative perspectives. In this context, it is essential to recognize that spatial planning manifests differently depending on the prevailing institutional and legal frameworks, as well as the specific planning cultures and traditions of each country [27]. Broadly speaking, spatial planning constitutes a distinct form of public governance aimed at managing and transforming space, reflecting the State’s intention to intervene strategically in order to shape a new territorial order [28,29].

The institutional framework identified by the authors of [30] as the “planning system” can be understood as a fundamental structural function of the State, on par with other domains of public action. It establishes the rules, objectives, and mechanisms that govern spatial use, shaping the ways in which the State interacts with citizens and territory. In this context, the formulation of planning laws constitutes an exercise in institutional design, articulating these relationships while embedding democratic values and principles of equity [31]. The idea of spatial planning system as an “institutional technology” [32] further enables public authorities to guide territorial transformation and management, integrating goals related to sustainable development, land-use regulation, environmental protection, and coordination of sectoral policies [21,30,33,34]. This institutional technology also combines formal instruments—plans, strategies, and regulations—with informal institutions that structure social interaction and generate trust in the system. The norms underpinning this technology may be cultural, economic, or political, and may be either legal or informal; moreover, these norms evolve over time and depend on historical trajectories, introducing volatility and uncertainty into the planning process [35].

Thus, spatial planning systems function as institutional mechanisms that structure competencies, resources, and procedures across different levels of government. Their transformation depends on both internal dynamics and external pressures [21,36,37]. Consequently, their conceptual link to multilevel governance is essential, as this framework explicates the interactive processes among actors operating at different territorial scales—national, regional, and local—within decision-making. From this vantage point, political and regulatory fragmentation emerges because of overlapping mandates, normative gaps, or contradictions between the competencies, norms, and practices of the different government levels, resulting in significant impediments to policy coherence and the effective design and implementation of planning instruments [37,38,39].

The existing literature highlights that the institutional dimension of spatial planning is foundational, as it defines the structural framework within which the entire spatial planning system functions, ultimately shaping its effectiveness, legitimacy, and adaptability. This importance stems from several key conditions:

- Institutions consolidate the “rules of the game” regulating development and land-use rights, influencing the distribution of power among the State, the market, and other actors [21,27,39].

- Institutional stability is reflected in territorial and urban stability, facilitating coordination among different levels of government (national, subnational, and local) [21,39].

- The institutional dimension conditions planners’ capacity to act, prioritize, and respond to the challenges of sustainable development and policy integration [21,39,40].

Consequently, an analysis of the institutional design of spatial planning must consider the following:

- The distribution of competences among different levels of government—the locus of power—as well as the mechanisms of interaction and coordination among them [39,41];

- The hierarchy of planning instruments, which determines their scope, coherence, and implementation capacity [42,43,44];

- The mechanisms of integration, both among political sectors and between formal and informal institutions [30,45];

- Participation, understood as the active engagement of civil society in planning processes, ensures legitimacy and fosters participatory governance [1,22,25];

- The legal and administrative frameworks, which establish the objectives, procedures, values, and guiding principles of planning, the mechanisms of implementation, and the systems of control and evaluation [21,23,46].

An additional key element in institutional analysis is the study of institutional change and capacity processes. These perspectives enable an understanding of how institutions evolve, adapt, and transform over time [27,36,47]. Any change in the political apparatus is reflected in the rules, norms, and organizational structures that underpin spatial planning systems, and thus warrants particular attention in the scholarly literature.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

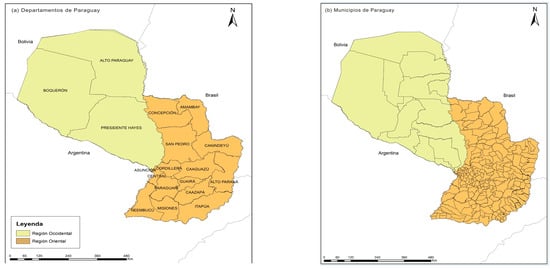

This section describes the geographical, demographic, bioclimatic, and institutional characteristics of Paraguay, which constitute the spatial reference framework for the analysis developed in this study. The territorial division of the country into departments and municipalities is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Departments; (b) municipalities. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on [44].

Paraguay is a landlocked country situated in the centre of South America, sharing borders with Brazil to the north and east, Argentina to the south and southwest, and Bolivia to the northwest. Its territory spans 406,752 km2 and is divided into two major natural regions—Eastern Paraguay and the Western Chaco—separated by the Paraguay River, whose longitudinal course functions as a structuring axis influencing the country’s relief, climate, and territorial dynamics.

The country has a population of 6,109,903 inhabitants [48]. The demographic distribution is markedly asymmetric: 96.5% of the population lives in the Eastern Region, which represents 39% of the territory, while 3.5% resides in the Western Region, which covers 61% of the territory. This configuration reflects a historical trajectory of greater urban and economic concentration in the eastern part of the country.

Paraguay’s territory belongs to the major South American river basins. The Paraguay and Paraná Rivers constitute the main fluvial axes and perform strategic functions for navigation, hydroelectric generation, and regional integration. The Paraguay River connects the La Plata basin with the logistic corridors of the Southern Cone, while the Paraná River delineates much of the southeastern border and concentrates binational hydroelectric infrastructure. These river systems are complemented by smaller tributaries such as the Pilcomayo, Apa, Tebicuary, and Aquidabán rivers, along with a network of wetlands and lagoons that form ecosystems of high biological diversity. Concurrently, Paraguay is part of the Guaraní Aquifer System, one of the largest underground freshwater reserves on the continent, whose presence adds a strategic dimension to territorial and environmental management.

In bioclimatic terms, Paraguay presents subtropical conditions with regional variations. The Eastern Region is characterized by a humid to sub-humid climate and the presence of Atlantic forests, whereas the Western Region exhibits a drier climate and is dominated by savannas, wetlands, and xerophytic forests.

Administratively, the country is organized into 17 departments and one capital district, subdivided into 262 municipalities. The Eastern Region concentrates most of these jurisdictions, while the Western Region has a more extensive territorial structure with a lower population density. This organizational framework constitutes the basis for the formulation and implementation of the spatial planning instruments analyzed in this study.

3.2. Methodological Design and Analytical Procedures

The methodology adopted is structured into four consecutive phases, as illustrated in Figure 2. In the first phase, the normative corpus was identified and refined through a systematic review of laws, decrees, regulations, and administrative documents related to spatial planning at the national, departmental (or regional), and municipal levels. This process enabled the compilation of a documentary corpus focused on provisions regarding land-use planning, spatial organization, public competencies, and guiding principles associated with spatial planning.

Figure 2.

Methodological framework for the analysis of spatial planning. Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The second phase involved content and discourse analysis, aimed at identifying principles, values, objectives, institutional functions, and both explicit and implicit spatial planning criteria present in the normative texts. A thematic coding matrix was developed based on analytical categories related to territorial development, governance, multilevel coordination, sustainability, institutional capacity, normative hierarchy, decentralization, and regulatory fragmentation.

The third phase consisted of a systematic review of operational planning instruments in force across different scales. The review encompassed the Plan Nacional de Desarrollo (National Development Plan, PND), national sectoral plans (covering environmental, urban, water resources, housing, and habitat sectors), the Planes Departamentales de Desarrollo (Departmental Development Plans, PDDs), the Planes de Desarrollo Sustentable Municipal (Municipal Sustainable Development Plans, PDSMs), and the Planes de Ordenamiento Urbano y Territorial (Urban and Spatial Plans, POUTs). The analysis focused on their regulatory nature, time horizon, intervention mechanisms, methodological foundations, and modes of articulation across scales. Based on this review, comparative matrices were constructed to support the systematization conducted in subsequent stages.

The fourth phase integrated the findings from the previous phases through a comparative systematization procedure, enabling the organization and interrelation of normative, institutional, and operational information in a structured manner.

The collection and systematization of regulatory information and planning instruments were conducted with a cut-off date of August 2025; therefore, the data reflect the most up-to-date status available at the time of analysis. This temporal delimitation does not alter the structural trends identified but rather allows for a more accurate assessment of the current degree of institutionalization and operational capacity of the planning system. In the case of the PDDs, PDSMs, and POUTs, the information was obtained from official records of the governing institutions and subnational governments, systematized by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF). There is no uniform updating periodicity for these instruments, as it depends on administrative cycles, plan formulation or renewal processes, and the reporting practices of subnational governments; thus, this represents an inherent limitation of the comparative analysis.

First, the study adopts the use of a neutral term of spatial planning—not tied to specific planning traditions, practices, or geographical context—as it is employed in the international literature on planning systems [35] and, in particular, in the ESPON COMPASS (Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe, 2018) project, whose final report provides key insights for an integrated understanding of spatial planning as a set of institutions aimed at regulating territorial transformations, as well as for defining the analytical logic and procedures concerning the structure and evolution of spatial planning systems [49].

Based on this, the analytical categories were defined through a prior literature review and the adaptation of methods used in COMPASS and subsequently contrasted with the regulatory corpus through an iterative adjustment process. The validation of these categories was carried out by means of theoretical triangulation and cross-review among the researchers, which ensured the internal coherence of the coding system. The four methodological phases are aligned in a sequential and integrated way: the identification of the regulatory corpus (Phase 1) constitutes the empirical basis for thematic coding (Phase 2); this, in turn, guides the comparative analysis of operational instruments across different spatial scales (Phase 3), whose results are finally consolidated through the cross-sectional systematization of the planning system (Phase 4).

Concurrently, across all phases, a review of the specialized literature on spatial planning, multilevel governance, and Latin American experiences was carried out, providing conceptual frameworks and analytical criteria to guide the organization of the analysis.

4. Results

The results are presented through three analytical dimensions, providing a structured and systematic examination of spatial planning in Paraguay. The first dimension explores the conceptualization of spatial planning within the current legal framework, analyzing how planning is defined, interpreted, and regulated. The second dimension examines the institutional framework and the distribution of competences across different levels of government. The third focuses on planning instruments and their degree of implementation and operational effectiveness.

This framework facilitates an understanding of the conditions under which spatial planning operates and the factors influencing its effectiveness. The bibliographic review indicates that policy coherence depends not only on conceptual clarity but also on institutional coordination and the practical functionality of planning instruments. Accordingly, the results highlight key limitations and provide a foundation for evaluating the capacity of the spatial planning system to support the country’s sustainable territorial development.

4.1. Evolution and General Approach to Spatial Planning in Paraguay

The conceptualization of spatial planning as a set of organized actions aimed at promoting territorial development and well-being dates to the colonial period. The Guaraní socio-political and territorial units (guará) and cooperative practices such as jopoi and minga structured community-based modes of intermittent land and resource use, characterized by mobile settlements and territorial control oriented toward subsistence and cultural cohesion [50,51]. From 1556 onward, the encomienda system forcibly redistributed population and labor—with approximately 20,000 Indigenous people assigned to some 300 encomenderos—establishing hierarchical structures of domination over land and labor [52]. In contrast, the Jesuit reductions (1610–1767) organized regular urban layouts, service infrastructures, and productive circuits with marketable surpluses, representing an early example of community-based territorial governance [50,53,54].

After the declaration of independence in 1811, the Paraguayan State inherited concentrated land ownership, intensified the alienation of public lands, and promoted colonization and immigration processes that introduced modern associative arrangements and experiences of collective management [55,56]. This historical background combined two persistent vectors: a centralized territorial configuration, with strong asymmetries in access to and control over land, and a tradition of community organization with self-management capacity, which is later reflected in the cooperative practices and institutional formalization of the twentieth century. Thus, the contemporary conceptualization of spatial planning in Paraguay rests upon this dual legacy of concentration and cooperation, which continues to influence multilevel coordination and the effectiveness of planning instruments [13,50].

An initial milestone of contemporary planning in Paraguay was the Plan Triángulo, conceived in the 1960s within the framework of the Alliance for Progress and aimed at connecting Asunción, Encarnación, and Ciudad del Este through road and energy corridors. Its purpose was to integrate the national territory and promote the opening of new agricultural areas, supported by external investments and the arrival of migrants. Although it became a reference for road planning until the 1980s, its impact was limited by the absence of a comprehensive legal framework and by the resistance of dominant economic sectors [52]. Consequently, spatial planning faced persistent obstacles: fragmented regulatory frameworks, low institutional coordination, and limitations in data and technical capacities [14]. In parallel, the processes of collective Indigenous land titling advanced slowly and unevenly, generating tensions between the formal recognition of rights and their effective application in the territory [17].

A current review of the Paraguayan legal framework shows that spatial planning lacks a dedicated law or overarching framework explicitly regulating it, resulting in a fragmented approach, with provisions distributed across different normative levels. At the apex is the National Constitution (1992), which establishes the basis for the country’s political–administrative division, recognizes the autonomy of departmental and municipal governments, and emphasizes the need for plans that integrate social, economic, and environmental factors [57]. Within this context, laws such as the Ley Orgánica Departamental (Law No. 426/1994, Departmental Organic Charter) and the Ley Orgánica Municipal (Law No. 3966/2010, Municipal Organic Charter) assign planning competences to subnational governments. These are complemented by sectoral regulations that incorporate the territorial dimension into urban, environmental, and water resource management domains.

The content and discourse analysis of these provisions reveals advances in incorporating principles such as legality, efficiency, transparency, and citizen participation, as well as various forms of inclusion of the territorial component within the current regulatory framework. Nevertheless, the absence of a formal Spatial Planning Act perpetuates regulatory fragmentation and impedes coherence across scales and sectors. Table 1 provides a synthesized overview of the core regulatory framework related to spatial planning in Paraguay. The detailed regulatory content for each regulation is presented in Appendix A Table A1.

Table 1.

Core regulatory framework related to spatial planning in Paraguay (synthesized overview).

Presently, spatial planning and territorial governance in Paraguay are characterized by a dispersed set of regulatory statements addressing sectoral aspects related to natural resource management, urban–rural planning, and cross-border cooperation. From a legal and administrative perspective, spatial planning is articulated through a framework of principles, norms, and competences that grant local governments a degree of autonomy in managing their territories. By delegating political, administrative, and financial authorities, municipalities and departments obtain the capacity to plan, organize, and implement projects that address the needs of their populations. In doing so, they constitute the legal foundations for territorial (or spatial) governance [58].

Spatial planning also encompasses the social, economic, and cultural dimensions of territory. This includes the recognition of rights—such as the communal ownership of Indigenous lands—and the incorporation of socioeconomic, demographic, ecological, and cultural criteria in shaping the State’s administrative divisions. Moreover, it regulates land use and the social function of land through agrarian reform and rural development policies aimed at territorial organization and territorial management.

4.2. Levels of Government and Competences in Spatial Planning in Paraguay

Spatial planning in Paraguay is based on the provisions of the National Constitution (1992), whose Article 177 states that “national development plans shall be non-binding for the private sector and mandatory for the public sector.” This provision grants a structural nature to spatial planning, linking state action to a general mandate that requires the articulation of strategies across different levels of government. Consequently, spatial planning in Paraguay is not conceived as a discretionary power but as a constitutional responsibility.

Based on this foundation, the institutional structure is organized under a decentralized framework, in which national, departmental, and municipal bodies interact. At the national level, the formulation of guidelines and policies with nationwide scope falls under the competence of multiple institutions. Among them are the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF), through the Vice-Ministry of Economy and Planning; the Ministry of Urbanism, Housing and Habitat (MUVH); the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MADES); the National Forestry Institute (INFONA); and the National Institute for Rural Development and Land (INDERT). These institutions are responsible for establishing strategic guidelines within their respective areas of action.

At the departmental level, the governorships are responsible for formulating and implementing the PDD and for coordinating their actions with the central government and the municipalities [59]. At the local level, municipalities exercise operational powers through mandatory instruments such as the PDSMs and POUTs [60]. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of the competences, limitations, and regulatory framework corresponding to each level of government.

Table 2.

An Overview of Planning Competences by Level of Government in Paraguay.

At the national level, the empirical review reveals persistent regulatory and sectoral fragmentation, largely attributable to the absence of a comprehensive Framework Law on Spatial Planning. Overlapping competences among ministries and autonomous agencies are evident, together with weak horizontal and vertical coordination between national and subnational governments. In addition, institutional changes linked to political cycles produce discontinuities in governance structures and planning priorities.

At the departmental level, the results indicate a high degree of budgetary and financial dependence on the central government, which significantly constrains managerial autonomy [61]. The availability of specialized technical personnel in spatial planning remains limited at the subnational scale, as acknowledged in Objective 5 of the PMNDyOT [62] (pp. 86–88). Furthermore, PDDs show low levels of implementation and a non-binding character. Limited capacity to coordinate municipalities and articulate policies at the regional scale is also observed [63] (pp. 20–26).

At the municipal level, the results highlight notable limitations in territorial information systems and in local management capacity, in part due to deficiencies in interinstitutional coordination [64]. The presence of technical teams and specialized offices dedicated to spatial planning also remains restricted [65]. Moreover, there is a marked time gap between the legal mandate to prepare POUTs and PDSMs (Ley 3966/2010) and the effective availability of methodological guidelines issued by the STP (POUT Guidelines, 2018; PDSM Guidelines, 2023), which has delayed their practical implementation [66,67].

4.3. Processes of Spatial Planning Implementation and Operationalization

The spatial planning instruments exhibit a gradual process of institutionalization that has enabled the formalization of operational frameworks across different levels of government. The transition from normative formulation to implementation presents uneven patterns across territories, with variations observed in technical capacities, availability of resources, and local specificities.

At the national level, the PND 2030 serves as the main strategic reference, guiding the formulation of sectoral and territorial policies. At the departmental level, the PDDs aim to articulate national guidelines with subnational priorities and realities. Finally, at the municipal level, the PDSMs and POUTs represent the instruments closest to citizens, integrating social, economic, environmental, and land-use dimensions. Table 3 summarizes the main instruments currently in force and the challenges associated with their implementation.

Table 3.

Spatial planning Instruments in Paraguay: Levels of Application, Purpose, and Regulatory Nature.

The PMNDyOT (2011) was approved by the STP as a non-binding document and continues to be recognized as a conceptual and methodological reference in spatial planning. Nevertheless, it has not been consolidated as a binding plan across the different levels of government.

The PND 2030, in force since 2014 and updated with a horizon to 2030, constitutes the first strategic plan with national scope. Its structure is organized around three main pillars: poverty reduction and social development, inclusive economic growth, and Paraguay’s integration into the world. These pillars are articulated through four cross-cutting lines: equal opportunities, transparent and efficient public management, spatial and territorial development planning, and environmental sustainability, which together give rise to twelve public action strategies. The plan is currently under review to develop the PND 2050 [69], which incorporates goals aimed at strengthening spatial planning and promoting the development of green cities, thereby reinforcing the territorial dimension within national planning.

The PNUVH is currently in the implementation phase and serves as a guiding framework for state action. Its content establishes the objectives, values, and principles that govern territorial interventions, granting it normative authority to guide the actions of public entities.

At the subnational level, PDDs are present in all 17 departments of the country [70], although with uneven levels of implementation. Departments such as Amambay, Canindeyú, Itapúa, and Central have explicitly incorporated spatial planning and established medium- and long-term horizons, while others, such as Cordillera, Guairá, and Misiones, are limited to short-term periods linked to government terms. Likewise, cases such as Ñeembucú, Boquerón, and Alto Paraguay show the absence of comprehensive PDDs, relying instead on previous or sectoral instruments.

At the local level, the PDSMs began to be developed in 2015. Of the 263 municipalities, 74% currently have expired plans, 19% have valid ones, and 7% show no documentary evidence. Coverage is broad but uneven, with greater progress in Itapúa, Alto Paraná, and Central, where consistent articulation with higher-level guidelines has been observed [71]. Regarding the POUTs, mandatory since Law No. 3966/2010, only 14% of municipalities had an approved plan as of April 2025, 13% were in the process of elaboration, and 73% lacked this instrument. Recent advances have been recorded in Alto Paraná, Itapúa, and Central; however, low coverage remains a significant limitation for ensuring balanced territorial development [72].

Overall, the assessment of spatial planning instruments highlights pronounced disparities in their degree of implementation across the three levels of government. National instruments tend to display a higher level of formal consolidation, whereas departmental and municipal tools remain partial or pending. These findings point to persistent challenges in inter-level integration, regulatory consistency, and uneven technical capacities, which collectively constrain the effective institutionalization of spatial planning in the country.

5. Discussion

Paraguay’s territorial governance exhibits a partial process of institutionalization: the normative and methodological framework has progressed more rapidly than the operational capacity necessary for its implementation. The result is a system that is decentralized in theory but centralized in practice, where overlapping competencies, financial dependence on the national level, and the limited availability of specialized human resources undermine territorial coherence [21,24,30]. The discrepancy between institutional design and implementation hampers policy continuity and the consolidation of territorial evaluation mechanisms, further accentuating regional inequalities stemming from the low autonomy of subnational governments [35]. These structural limitations partly explain the temporal and institutional gap that has characterized the evolution of the country’s spatial planning system.

From a historical–institutional perspective, a distinctive characteristic of the Paraguayan case is the temporal–institutional gap between the constitutionally defined competencies and the actual establishment of spatial planning instruments. Although the National Constitution (1992) established the foundations for a decentralized planning system—making national plans mandatory and promoting articulation across different levels of government—departmental powers were not regulated until 1994, and municipal ones until 2010. The first National Development Plan (PND) was approved in 2014, more than two decades after the constitutional enactment. This asynchrony produced a prolonged disconnection between the founding principles of spatial planning and its effective application, resulting in persistent gaps in intergovernmental coordination. At the same time, the proliferation of sectoral frameworks—agrarian, environmental, and urban—broadened normative fragmentation, hindering the integration of territorial policies within a common framework [30,43].

The operational institutionalization of spatial planning has been grounded in the establishment of Departmental and Municipal Development Councils, structures designed to foster intergovernmental coordination and the participation of social actors. However, their practical implementation suffers from inconsistencies and irregularities, limiting their function to a formal or nominal compliance that differs substantially from an effective or substantive application.

Moreover, the absence of dedicated funding, the rotation of representatives, and the lack of monitoring mechanisms prevent these councils from consolidating themselves as effective components of territorial governance [36]. This institutional weakness is replicated in other components of the system, particularly in the enforcement of the regulatory framework and in participation mechanisms.

Paraguayan spatial planning is based on a fragmented legal framework that combines constitutional provisions, sectoral laws, and local regulations. This fragmentation generates redundancies and overlaps in competencies among the different levels of government in regard to environmental, agrarian, and urban issues. The lack of a normative hierarchy hinders multilevel articulation and the coherence of planning instruments, reproducing a pattern of fragmented planning [21,33]. Furthermore, citizen participation—although established as a guiding principle—remains limited to consultative instances, where Indigenous peoples and rural communities continue to be underrepresented in planning processes, thereby reducing the social legitimacy of the planning instruments [73].

Given these internal limitations, international cooperation has played a compensatory role in building Paraguay’s institutional capacities, particularly through programs promoted by the JICA, UNDP, and USAID. These initiatives have supported the formulation of national- and subnational-scale territorial governance instruments, the development of technical guidelines, and the implementation of pilot initiatives in selected departments and municipalities [62,66,67]. Nevertheless, the strong reliance on external technical support has also generated intermittent progress and structural constraints on the sustainability of policies once projects have ended, as planning and governance processes often depend on externally funded capacity-building initiatives, posing risks to their long-term institutional consolidation [14].

From a territorial governance perspective, this situation is consistent with the persistence of local capacity constraints identified in place-based territorial governance approaches [74], which limit the consolidation of governance, management, and multilevel coordination processes in the medium and long term. This is further reinforced by what the authors of [75] conceptualize as a “capability trap”, in which externally driven reforms and technical assistance fail to translate into durable local capacities due to mechanisms such as isomorphic mimicry and institutional overloading. Within this framework, international cooperation may play a transformative role insofar as its interventions are explicitly oriented towards the effective consolidation of endogenous institutional capacities, thus avoiding the reproduction of dynamics of dependency and low performance in policy implementation.

The enforceability of regulations constitutes another structural challenge. The principles of sustainability, equity, and transparency coexist with gaps in control and sanction, which weaken the effective application of planning instruments. Several studies indicate that the lack of coercive power reduces the effectiveness of spatial planning systems by turning regulations into indicative references rather than binding frameworks [22,23]. This condition is reflected in the limited operability of the PDSMs and POUTs, whose coverage remains low.

The territorial consequences of the disconnection between spatial planning and sustainability are reflected in the agricultural and livestock expansion in the Western Chaco, which is characterized by a rapid loss of forest cover in areas lacking effective territorial management [76]. Regional inequalities amplify the effects of this institutional fragmentation: gaps in public investment, technical capacities, and plan implementation are more pronounced in rural areas with low population density and limited infrastructure. This configuration, linked to a demographic and economic structure concentrated in the Eastern Region, reproduces a historical pattern of centralization and institutional dependence [77], highlighting the need to integrate spatial planning with policies aimed at regional cohesion and balance.

From a regional perspective, Paraguay shares with other Latin American countries several structural challenges related to regulatory fragmentation, overlapping competencies, and intergovernmental coordination. Some national frameworks have introduced provisions for territorial coordination or municipal implementation instruments, while others have advanced toward multilevel planning schemes; however, their scope and outcomes remain heterogeneous across the region [1]. Paraguay continues to operate under an indicative system with limited enforceability [14]. As highlighted in [42], the effectiveness of spatial planning depends on the hierarchical order and practical applicability of local instruments—dimensions that are still under development in the country.

Within the specific context of the Southern Cone, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay show more consistent progress in the articulation of sectoral, physical–spatial, environmental, and, in some cases, regional approaches. Argentina combines sectoral development with physical–spatial and environmental planning; Brazil integrates physical–spatial and environmental planning with an explicit regional development approach; Uruguay primarily articulates physical–spatial planning with an environmental approach within a nationally coordinated system; and Chile is predominantly oriented toward physical–spatial planning. In contrast, Paraguay maintains a more limited articulation situated between physical–spatial planning and the environmental approach, without explicitly incorporating the regional approach or territorial organization as structuring axes [78].

The analysis reveals that consolidating a coherent spatial planning system in Paraguay depends on clarifying normative hierarchies and achieving effective coordination among different levels of government [58]. Institutional fragmentation, weak enforcement mechanisms, and limited technical capacity at the subnational level continue to constrain the operability of planning instruments [24,30]. In this regard, territorial observatories and development councils represent potential platforms for improving governance and information integration, provided they are supported by technical expertise and administrative continuity.

In summary, the analysis of spatial planning in Paraguay reveals a persistent mismatch between the institutional structure and its implementation capacity. This imbalance reflects the gap between normative formalization and administrative practice—a feature shared with other Latin American countries. Overcoming this divide requires progress toward a planning approach capable of integrating sustainability, equity, and multilevel coordination as operational rather than merely declarative dimensions within public policy.

6. Conclusions

This article provides an integrated analysis of Paraguay’s spatial planning system, examining its legal framework, the distribution of competencies, and the operability of its planning instruments. In terms of evolution, the system has moved toward partial institutionalization: frameworks and methodologies have been established, but their implementation remains uneven across government levels and territories. Regarding its main features and challenges, regulatory fragmentation, overlapping competencies, weak enforceability of planning instruments, and heterogeneous subnational capacities persist, all of which limit multilevel coherence.

From an academic perspective, the main contribution of this study lies in demonstrating how the gap between normative design and operational implementation becomes a structural feature of spatial planning in contexts characterized by indicative governance, limited enforcement, and uneven state capacities, thereby contributing to the comparative literature on multilevel territorial governance in Latin America.

The findings yield important implications for the design and management of Paraguay’s spatial planning system. Effectiveness depends less on introducing new instruments than on enhancing existing ones through clear hierarchy, enforceability, and monitoring mechanisms. More specifically, this requires an explicit definition of the hierarchical relationships between national, departmental, and municipal plans; the establishment of binding implementation and monitoring requirements for subnational instruments; and the consolidation of interoperable territorial information systems. In operational terms, this implies clarifying the relationships among different levels of government, strengthening subnational technical capacities, and consolidating information systems that enable the evaluation of outcomes and the adjustment of strategies. It also suggests aligning international cooperation with permanent institutional structures to ensure that external assistance is integrated into administrative continuity and national and local budgetary cycles.

Advancing toward an integrated system requires transferring principles into actionable and verifiable practices, necessitating instruments with clearly defined hierarchy and enforceability, operational multilevel alignment, and social legitimacy grounded in meaningful citizen participation. When planning, sustainability, and equity operate as functional rather than merely declarative dimensions, territorial governance will possess the necessary conditions to guide spatial transformations that are predictable, redistributive, and sustainable.

The identified limitations highlight new paths for research. It is crucial to explore in greater detail the intra-departmental and inter-municipal variation in the adoption of planning instruments, assess the effects of fiscal and technical capacity on implementation, and examine the relationship between Indigenous governance and local planning structures. Likewise, it is relevant to deepen the analysis of the link between planning and land-use change, drawing on longitudinal evidence and comparable metrics that connect instruments, decisions, and territorial outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L.G. and V.S.S.; methodology, E.L.G. and V.S.S.; validation, E.L.G., V.S.S. and N.B.I.F.; formal analysis, E.L.G. and V.S.S.; investigation, E.L.G. and N.B.I.F.; resources, N.B.I.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.G. and V.S.S.; writing—review and editing, E.L.G., V.S.S. and N.B.I.F.; visualization, E.L.G.; supervision, V.S.S.; project administration, E.L.G.; funding acquisition, E.L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated in this study. All information used originates from public, regulatory, and documentary sources duly cited in the manuscript. The data and documents used for the analysis, including the Departmental Development Plans (PDDs) and the Municipal Development and Urban and Spatial planning Plans (PDSMs and POUTs) referenced in Appendix A, are publicly available from official institutional sources.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the National Scholarship Program for Postgraduate Studies Abroad “Don Carlos Antonio López” (BECAL), Paraguay, as well as the academic collaboration of the National University of Itapúa and the University of Barcelona during the development of this research. During the preparation of this manuscript, AI-based assistance was used for language revision and text editing. The authors reviewed and validated all content and assume full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMUCA | Association of Municipalities of Caazapá |

| CDD | Departmental Development Council |

| CN | National Constitution |

| EIA | Environmental Impact Assessment |

| FODA | Strengths, Opportunities, Weaknesses, and Threats (SWOT) |

| INDERT | National Institute for Rural and Land Development |

| INFONA | National Forestry Institute |

| JICA | Japan International Cooperation Agency |

| MADES | Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development |

| MEF | Ministry of Economy and Finance |

| MERCOSUR | Southern Common Market |

| MUVH | Ministry of Urbanism, Housing, and Habitat |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OTAS | Environmentally Sustainable Spatial Planning |

| PAN | National Environmental Policy |

| PDD | Departmental Development Plan |

| PDSM | Municipal Sustainable Development Plan |

| PGA | Environmental Management Plan |

| PLANDETUR | Strategic Tourism Development Plan (Ñeembucú) |

| PMNDyOT | National Framework Plan for Development and Spatial Planning |

| PND | National Development Plan |

| PNPI | National Plan for Indigenous Peoples |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| PNUVH | National Policy for Urban Development, Housing, and Habitat |

| POTA | Territorial and Environmental Planning Plan |

| POUT | Urban and Spatial planning Plan |

| SENATUR | National Tourism Secretariat |

| SISNAM | National Environmental System |

| STP | Technical Secretariat for Economic and Social Development Planning |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Regulatory framework for spatial planning in Paraguay: objectives, guiding principles, and implementation instruments.

Table A1.

Regulatory framework for spatial planning in Paraguay: objectives, guiding principles, and implementation instruments.

| Regulation | Objectives Related to Spatial Planning | Guiding Principles Related to Spatial Planning | Implementation of Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Constitution (1992) | To promote quality of life, socioeconomic development, environmental preservation, and citizens’ well-being. | Human dignity, freedom, equality, justice, equity, participatory democracy, and social, economic, and cultural welfare and integration. | -PND |

| Law No. 904/1981–Estatuto de Comunidades Indígenas (Statute of Indigenous Communities) | To establish legal mechanisms for the allocation of public or private lands, preserving traditional possession and ensuring the cultural, social, and economic continuity of communities. | Cultural identity, territorial equity, social justice, community participation, and environmental preservation. | -Plan Nacional de Pueblos Indígenas (National Plan for Indigenous Peoples, PNPI 2016–2020). |

| Law No. 294/1993—Evaluación de Impacto Ambiental (Environmental Impact Assessment) | To establish a regulatory framework guiding spatial planning in Paraguay and providing the technical and strategic basis for the deliberation and approval of new development projects and activities. | Transparency and public participation, precautionary principle, and subsidiarity in regulation. | -Política Ambiental Nacional (National Environmental Policy, PAN) *; -Plan de Gestión Ambiental (Environmental Management Plan, PGA) |

| Law No. 426/1994—Ley Orgánica Departamental (Departmental Organic Law) | To coordinate and implement policies, plans, and projects for departmental development in areas such as economy, society, and culture, aligning efforts with the National Development Plan to ensure coherence across government levels. | Equity, transparency, accountability, and citizen participation. | -PDDs. |

| Law No. 1863/2002—Estatuto Agrario (Agrarian Statute) | To promote the adjustment of the agrarian structure, strengthen family farming, and ensure equitable land distribution, thus fostering the economic and physical integration of the territory. | Social and economic function of land, rational use of resources, environmental sustainability, distributive equity, rural rootedness, community participation, institutional cooperation, and food security. | -Land-use and management plans; land surveying and subdivision. -Environmental Impact Studies (EIA). |

| Law No. 3239/2007—Recursos Hídricos del Paraguay (Water Resources of Paraguay) | To integrate water resource management with development planning and territorial organization, using the watershed as the central element for equitable territorial integration. | Human right to water, equality, and participatory management. | -Política Nacional de los Recursos Hídricos ** (National Water Resources Policy). |

| Law No. 3966/2010—Ley Orgánica Municipal (Municipal Organic Law) | To develop and implement municipal spatial planning through two instruments: the PDSMs and the POUTs. The latter aims to guide and reconcile land use and occupation in both urban and rural areas. | Transparency, rationality, social equity, and citizen participation. | -PDSMs. -POUTs. |

| Decree No. 1110/2024—Approval of the Política Nacional de Urbanismo, Vivienda y Hábitat (National Policy for Urbanism, Housing, and Habitat, PNUVH) | To promote sustainable urban planning that fosters orderly city growth and improves quality of life through access to basic services, quality housing, and climate-resilient urban spaces, ensuring efficient land use and prioritizing environmental conservation and development in suitable areas. | Sustainability, participation, transparency, accountability, shared responsibility, and territorial resilience. | -PNUVH (under development). |

| Law No. 7261/2024—Acuerdo sobre Localidades Fronterizas Vinculadas (Agreement on Linked Border Localities) | To formulate Planes Conjuntos de Desarrollo Urbano y Ordenamiento Territorial (Joint Urban Development and Spatial Planning Plans, PCDUyOT) to promote cross-border cooperation, harmonize spatial organization, improve service provision, and strengthen infrastructure, contributing to reducing asymmetries among MERCOSUR border municipalities. | International cooperation, reciprocity, territorial equity, socioeconomic integration, sustainability, and community participation. | -PCDUyOT (not yet implemented). |

* The Política Ambiental Nacional (PAN) is formally designated as a policy, although its implementation is operationalized through planning instruments, mainly the Plan de Gestión Ambiental (PGA) and Environmental Impact Studies (EIA). ** The Política Nacional de los Recursos Hídricos is formally designated as a policy, and its implementation is carried out through instruments derived from Law 3239/2007, primarily watershed management plans, specific programs, and projects oriented toward integrated water management.

Table A2.

Comparative Analysis of Departmental Development Plans (PDDs) in Paraguay.

Table A2.

Comparative Analysis of Departmental Development Plans (PDDs) in Paraguay.

| Department | Validity | Articulation with PND 2030 | Incorporation of Spatial Planning | Participation Mechanisms | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Concepción | 2016–2020 | Partial. Contains social, economic, and environmental objectives compatible with the PND 2030 but does not explicitly adopt its structure of pillars and cross-cutting lines. | Partial (no specific axis on spatial planning, though coordination with municipalities is mentioned). | Multisectoral meeting with public institutions, communities, associations, and NGOs; methodological support from STP. | Broad and documented participation; STP assistance; inclusion of various social sectors. Short validity and no clear linkage with the PND 2030. |

| 2. San Pedro | 2018–2023 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit (includes spatial planning and sustainability as cross-cutting dimensions). | Working meetings, technical talks, and opinion debates with social and institutional actors. | Articulated with the PND 2030; incorporates territorial and environmental dimensions; broad participation with a consultative emphasis. |

| 3. Cordillera | 2016–2018 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit (includes spatial planning and sustainability as cross-cutting lines). | Establishment of sectoral roundtables for diagnosis and the subsequent formulation of objectives and actions. | Aligned with the PND 2030; short validity coinciding with the political government period. |

| 4. Guairá | 2016–2018 | Partial. Contains social, economic, and environmental objectives compatible with the PND 2030 but does not explicitly adopt its structure. | Explicit: includes departmental spatial planning as a strategic objective and agreements with STP. | Multisectoral meeting with representatives of public and private institutions, NGOs, and communities; formal establishment of the Departmental Development Council. | Short validity; highlights the formal creation of the Departmental Council as a governance mechanism. |

| 5. Caaguazú | 2014–2030 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit (includes spatial planning as a strategic dimension and urban improvement). | Working tables with local and departmental actors; District and Departmental Development Councils; Mayors’ Council; coordination with STP and ministries; interaction with the private sector and embassies. | Long-term plan (2014–2030) aligned with the PND 2030; includes indigenous rootedness, youth employment, and family farming; strong emphasis on spatial planning to reduce informal settlements; demonstrates a multi-level participatory approach. |

| 6. Caazapá | 2016–2021 | Explicit (states the relationship with the PND 2030 pillars and coordination with PDMs of 11 districts). | Partial: recognizes the territorial dimension in the diagnosis and SWOT, mentioning forest reserves and environmental management. | Departmental Development Council; working groups and assemblies with public institutions, AMUCA, sectoral councils, and indigenous communities. | Inclusive participatory process; strong focus on health, education, and environment. Medium-term validity and recognized articulation with PND 2030. |

| 7. Itapúa | 2016–2030 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit: incorporates spatial planning as a cross-cutting axis and links it to municipal POUTs and PDSMs. | Participation through the Departmental Development Council; workshops, assemblies, and working groups with social, economic, and environmental actors; methodological assistance from STP. | Long-term horizon (2016–2030) aligned with PND 2030; strong integration of spatial planning in departmental management; broad, well-documented participatory process; one of the most consolidated PDDs in terms of multi-level coherence. |

| 8. Misiones | 2019–2024 | Partial. Contains dimensions aligned with PND 2030 pillars but does not adopt its methodological structure or explicitly mention it. | Implicit. Addresses infrastructure and land-use issues but does not include spatial planning as a strategic axis. | Consultations with the Departmental Board, mayors, municipal councils, business sectors, teachers, livestock producers, health, culture, and youth sectors. | Medium-term validity; broad, multisectoral participation; planning focused on social and productive issues but lacking methodological reference to PND or spatial planning as a structural policy. |

| 9. Paraguarí | 2016–2020 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit (includes environmental sustainability and spatial planning as part of the territorial diagnosis and strategic axes). | Working meetings, technical talks, and opinion debates with social and sectoral actors. | Articulated with PND 2030; strong emphasis on environmental sustainability; short validity coinciding with the departmental government period. |

| 10. Alto Paraná | 2016–2020 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit: incorporates spatial planning in departmental planning and recognizes the need for new urban centers. | Departmental councils and permanent commissions (health, education, economy, public works, agriculture, strategic studies, public–private investment); methodological support from STP. | Reflects the department’s urban and agricultural dynamics; highlights economic diversification and the challenge of border-model restructuring. |

| 11. Central | 2016–2026 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit: promotes orderly territorial development, with emphasis on environmental sustainability and participatory planning. | Participatory process through the Departmental Development Council, sectoral roundtables, and records of citizen initiatives; methodological support from STP. | Medium- to long-term plan (2016–2026); strong articulation with PND 2030; broad program agenda in health, education, and economy; notable for including a political–institutional axis of participatory local development. |

| 12. Ñeembucú | Not identified | Not identified in a PDD. Indirect references are observed in the Strategic Tourism Development Plan of Ñeembucú (PLANDETUR 2020–2024), which incorporates guidelines on accessibility, sustainability, and land use for tourism purposes. | Within the framework of PLANDETUR, workshops were held with the Governor’s Office, municipalities, SENATUR, tourism operators, and community organizations. | The department lacks an identified PDD. However, the PLANDETUR Ñeembucú 2020–2024 is available as a sectoral instrument reflecting efforts in spatial planning within the tourism field, though it does not replace a comprehensive PDD articulated with the PND 2030. | |

| 13. Amambay | 2016–2020 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit. Includes the Territorial and Environmental Planning Plan (POTA) as a tool for urban and rural land management, land regularization, and environmental sustainability. | Formation of the Departmental Development Council (CDD); workshops and participatory diagnostics with institutional, community, and Indigenous representatives. | PDD with a 2016–2020 horizon, articulated with the PND 2030. Integrates objectives in education, health, employment, infrastructure, and environment; incorporates spatial planning through the POTA with a multi-actor participatory approach. |

| 14. Canindeyú | 2016–2020 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit. Foresees the development of a departmental spatial planning plan over five years, with guidelines for land use, infrastructure, and environmental protection. | Official formation and recognition of the Departmental Development Council; diagnostic workshops; participation of public institutions, community organizations, producers, and Indigenous peoples. | PDD with a 2016–2020 horizon, aligned with the PND 2030. Integrates programs in education, health, employment, infrastructure, family farming, and environment. Explicitly includes spatial planning as a strategic goal and features a broad, multisectoral participatory approach. |

| 15. Presidente Hayes | 2017–2020 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit. The plan envisages a spatial planning process defining rural and urban land use, considering economic, social, cultural, and environmental impacts to improve public service provision. | Departmental Development Council with participatory diagnostics, neighborhood committees, and inter-institutional agreements with municipalities and civic associations. | Short-term PDD (2017–2020). Includes objectives in education, health, infrastructure, tourism, and spatial planning. Reflects a participatory local development approach but with a limited horizon and no clear methodological articulation with the PND 2030. |

| 16. Boquerón | 2014–2018 | Explicit (adopts the strategic pillars and cross-cutting lines of the PND 2030). | Explicit. Incorporates spatial planning guidelines for land use, environmental sustainability, agricultural production, and natural resource management. | Developed from the 2014–2018 Strategic Plan of the Governor’s Office. Included diagnostics, workshops with public and private sectors, technical validation, and periodic follow-up through mini workshops. | PDD with a 2014–2018 horizon, aligned with the PND 2030. Integrates goals in education, health, infrastructure, production, and environment. Incorporates spatial planning as a tool for sustainability and reflects a structured, periodic participatory process. |

| 17. Alto Paraguay | Agenda 2010 (in implementation since 2003) | Not explicit, developed before its approval. | Explicit. Departmental and municipal spatial planning projects with ordinances for zoning and sustainable resource use. | Forums and workshops with broad participation (over 600 public, private, Indigenous, and community actors); inter-institutional executive committee. | Plan with distinctive features compared to other PDDs. A pioneering precedent of participatory spatial planning in the Paraguayan Chaco, with a strong environmental and intercultural emphasis. Lacks recent updates and is not methodologically articulated with the PND 2030, although it introduced innovations in territorial governance and aligns with the concept of territorial development as a process of productive and institutional transformation in self-determined rural spaces aimed at poverty reduction and local cooperation strengthening. |

Table A3.

Status of Municipal Sustainable Development Plans (PDSMs) and Urban and Spatial Planning Plans (POUTs) by Department.

Table A3.

Status of Municipal Sustainable Development Plans (PDSMs) and Urban and Spatial Planning Plans (POUTs) by Department.

| Department | No. of Municipalities | PDSMs | POUTs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Available | Expired | Valid (≥2025) | Not Available | In Progress | Approved | ||

| Asunción * | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Concepción | 14 | 3 | 11 | - | 12 | 2 | - |

| San Pedro | 22 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 19 | 1 | 2 |

| Cordillera | 20 | - | 17 | 3 | 18 | - | 2 |

| Guairá | 18 | - | 18 | - | 17 | - | 1 |

| Caaguazú | 22 | - | 21 | 1 | 14 | - | 8 |

| Caazapá | 11 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| Itapúa | 30 | 2 | 19 | 9 | 22 | 3 | 5 |

| Misiones | 10 | - | 10 | - | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| Paraguarí | 18 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 2 |

| Alto Paraná | 22 | - | 11 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 7 |

| Central | 19 | - | 11 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 3 |

| Ñeembucú | 16 | - | 14 | 2 | 15 | 1 | - |

| Amambay | 6 | 1 | 5 | - | 6 | - | - |

| Canindeyú | 16 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 1 |

| Presidente Hayes | 10 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Boquerón | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 3 | 1 |

| Alto Paraguay | 4 | - | 1 | 3 | - | 3 | 1 |

| Totals | 263 | 18 | 194 | 51 | 193 | 33 | 37 |

| 100% | 7% | 74% | 19% | 73% | 13% | 14% | |

* The City of Asunción is not part of Paraguay’s political–administrative departmental division, in accordance with Article 77 of the National Constitution (1992), which establishes its status as the capital of the Republic, the seat of the branches of government, and a municipality independent from any department. Its inclusion in the table is solely for comparative analysis purposes. The information on the PDSMs and POUTs is based on official administrative records available as of August 2025. Their updating does not follow a uniform periodicity, as it depends on local administrative cycles and the formal approval or revision processes of each instrument.

References

- Blanc, F.; Cabrera, J.; Cotella, G.; Vecchio, G.; Santelices, N.; Casanova, R.; Saravia, M.; Blanca, M.; Reinheimer, B. Latin American territorial governance and planning systems and the rising judicialisation of planning. Disp Plan. Rev. 2022, 58, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Vargas, M.J. Consolidación de los Antiguos Espacios Territoriales de Capacitación y Reincorporación en el Ordenamiento Territorial Municipal de Colombia: De la Norma a la Práctica. Estudio de caso del antiguo ETCR de Filipinas, Municipio de Arauquita, Arauca. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De Waroux, Y. Frontier constellations: A history of land-use regimes in Paraguay’s Pilcomayo River Basin. Geogr. Rev. 2024, 114, 489–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomers, A.; van der Haar, G. (Eds.) Current Land Policy in Latin America: Regulating Land Tenure Under Neo-Liberalism; KIT Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Botella-Rodríguez, E.; González-Esteban, Á. Twists and turns of land reform in Latin America: From predatory to intermediate states? J. Agrar. Change 2021, 21, 834–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picanço, M.; Guimarães, J.; Silva, W.; da Silva, M.; da Cruz, S.; Júnior, R. The historical evolution of land use. Cader. Pedagóg. 2025, 22, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irazábal, C. Governance, Institutional COORDINATION, and socio-Spatial Justice: Reflections from Latin America and the Caribbean. In Resilient Urban Regeneration in Informal Settlements in the Tropics; Carracedo García-Villalba, O., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, J.; Blanc, F.; Cotella, G. Exploring Territorial Governance and Planning in Latin America. In Territorial Governance and Planning in Latin America; Cabrera, J., Blanc, F., Cotella, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagómez, M.; Cuesta, R.; Sili, M.; Vieyra, A. Metodología para el análisis de las prácticas y políticas de ordenamiento territorial en América Latina: El caso de Argentina, Ecuador, México y Paraguay. Rev. Geogr. 2020, 160, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, L.; Baur, R.; Csaplovics, E. Urban sprawl and fragmentation in Latin America: A dynamic quantification and characterization of spatial patterns. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 115, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocco, R. Introduction to Special Theme Practice Forum: Latin American spatial planning beyond clichés. Plan. Pract. Res. 2019, 34, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, H. Ordenamiento Territorial en América Latina; EUROsociAL+: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eurosocial.eu/biblioteca/doc/ordenamiento-territorial-en-america-latina/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Lezcano González, E.; Simeonova, V. Cooperativa y Desarrollo local en Paraguay: Desde los Guaraníes hasta la Modernidad. In América Latina: Paradigmas, Procesos y Desafíos en un Contexto de Cambios (Hiper) Acelerados; Plaza Gutiérrez, J.I., Sánchez Ondoño, I., Moreno Arriba, J., Eds.; Asociación Española de Geografía (AGE): Madrid, Spain, 2025; pp. 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delphin, S.; Snyder, K.; Tanner, S.; Musalem, K.; Marsh, S.; Soto, J. Obstacles to the development of integrated land-use planning in developing countries: The case of Paraguay. Land 2022, 11, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro-Cañete, A.; Fogel, R. A coup foretold: Fernando Lugo and the lost promise of agrarian reform in Paraguay. J. Agrar. Change 2017, 17, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusing, C. The new Guarani reductions: Aftermaths of collective titling in Northern Paraguay. J. Peasant Stud. 2021, 50, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusing, C.; Leemann, E. Time as the enemy? Disjointed timelines and uneven rhythms of Indigenous collective land titling in Paraguay and Cambodia. Land 2023, 12, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioletti, M. The national territorial governance and planning systems in the LAC region: The structure of Brazil, Bolivia, and Cuba. Prog. Plan. 2024, 188, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallabrida, V.; Büttenbender, P.; Covas, A.; de Mendonça Covas, M.; Costamagna, P.; de Oliveira Menezes, E. State and society in building capabilities to strengthen practices of territorial governance. Rev. Bras. Estud. Urbanos Reg. 2022, 24, e019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sili, M.; Ávila, C.; Sotelo, N. Modelos de acción y desarrollo territorial: Un ensayo de clasificación en el Paraguay. Cuad. Geogr. 2019, 58, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, E.; Cotella, G.; Rivolin, U.; Solly, A. Territorial governance and planning systems in the public control of spatial development: A European typology. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 29, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, D. Legal aspects of spatial planning: Foreign experience. Law Innov. 2024, 2, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeonova, V.; Nowak, M. Legal compliance in spatial and urban planning: Myth or reality? A comparative analysis of Bulgaria and Poland. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2024, 102, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Cotella, G.; Sleszyński, P. The legal, administrative, and governance frameworks of spatial policy, planning, and land use: Interdependencies, barriers, and directions of change. Land 2021, 10, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchehlyuk, S.D. Institutional Support for Spatial Planning of the Amalgamated Territorial Communities. In Socio-Economic Problems of the Modern Period of Ukraine; National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: Lviv, Ukraine, 2019; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinós-Dasi, J. Guía para una Gobernanza Efectiva del Territorio: Un Decálogo para la Buena Práctica de la Ordenación del Territorio en España; Publicacions de la Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://omp.uv.es/index.php/PUV/catalog/book/444 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Sorensen, A.; Adams, N. Regulating capital investment in urban property: Towards comparative-historical research in planning history. Plan. Perspect. 2024, 40, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewdwr-Jones, M. Cohesion and Competitiveness: The Evolving Context for European Territorial Development. In Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning; Adams, N., Cotella, G., Nunes, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massiris Cabeza, A. Construcción de Territorialidades y Prácticas de Ordenamiento Territorial en América Latina. In Territorio y Estados: Elementos para la Coordinación de las Políticas de Ordenación del Territorio en el Siglo XXI; Farinósi Dasí, J., Peiró Sánchez-Manjavacas, E., Eds.; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2018; pp. 1211–1240. ISBN 978-84-16556-85-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nadin, V.; Stead, D.; Dąbrowski, M.; Fernandez-Maldonado, A. Integrated, adaptive and participatory spatial planning: Trends across Europe. Reg. Stud. 2020, 55, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, L.A.; Falcão, A.O.; do Carmo, M.B. Territorial governance and Institutional Arrangements in Land-Use Planning: A Systematic Review. Land 2023, 12, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolin, U.J. Planning systems as institutional technologies: A proposed conceptualization and the implications for comparison. Plan. Pract. Res. 2012, 27, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, J. Plan(e) speaking: A multiplanar theory of spatial planning. Plan. Theory 2008, 7, 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Territory spatial planning and national governance system in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadin, V.; Cotella, G.; Schmitt, P. Spatial planning systems: A European perspective. In Spatial Planning Systems in Europe: Comparison and Trajectories; Nadin, V., Cotella, G., Schmitt, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, K.; Humer, A.; Mäntysalo, R. Tensions in city-regional spatial planning: The challenge of interpreting layered institutional rules. Reg. Stud. 2020, 55, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulumello, S.; Cotella, G.; Othengrafen, F. Spatial planning and territorial governance in Southern Europe between economic crisis and austerity policies. Int. Plan. Stud. 2020, 25, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotella, G.; Rivolin, U.; Pede, E.; Pioletti, M. Multi-level regional development governance: A European typology. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2021, 28, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Making Strategic Spatial Plans: Innovation in Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trygg, K.; Wenander, H. Strategic spatial planning for sustainable development: Swedish planners’ institutional capacity. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 30, 1985–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. Spatial planning in cross-border regions: A systems-theoretical perspective. Plan. Theory 2016, 15, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Petrișor, A.; Mitrea, A.; Kovács, K.; Lukstiņa, G.; Jürgenson, E.; Ladzianska, Z.; Simeonova, V.; Lozynskyy, R.; Řezáč, V.; et al. The role of spatial plans adopted at the local level in the spatial planning systems of Central and Eastern European countries. Land 2022, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asprogerakas, E.; Melissas, D. Reflections on the hierarchy of the spatial planning system in Greece (1999–2020). Int. Plan. Stud. 2023, 28, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, R.A. The Concept of Spatial Planning and the Planning System. In Spatial Planning in Ghana; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]