Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Tourism Through Community Participation: Insights from Mt. Rtanj, Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

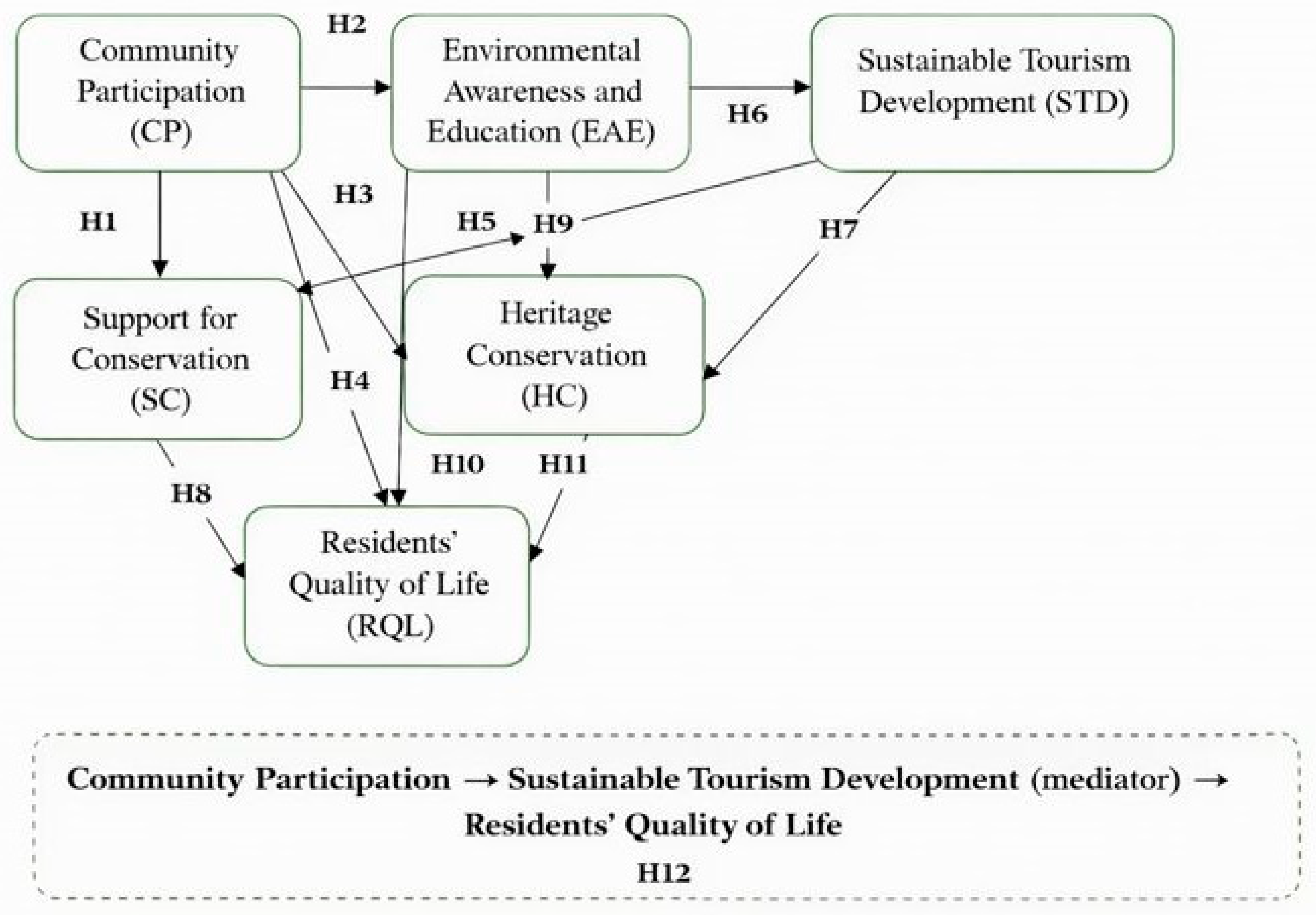

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Nature Protected Areas and Ecotourism

2.2. Community Participation in Ecotourism

2.3. Sustainable Tourism Development

2.4. Support for Conservation

2.5. Environmental Awareness and Education

2.6. Heritage Conservation

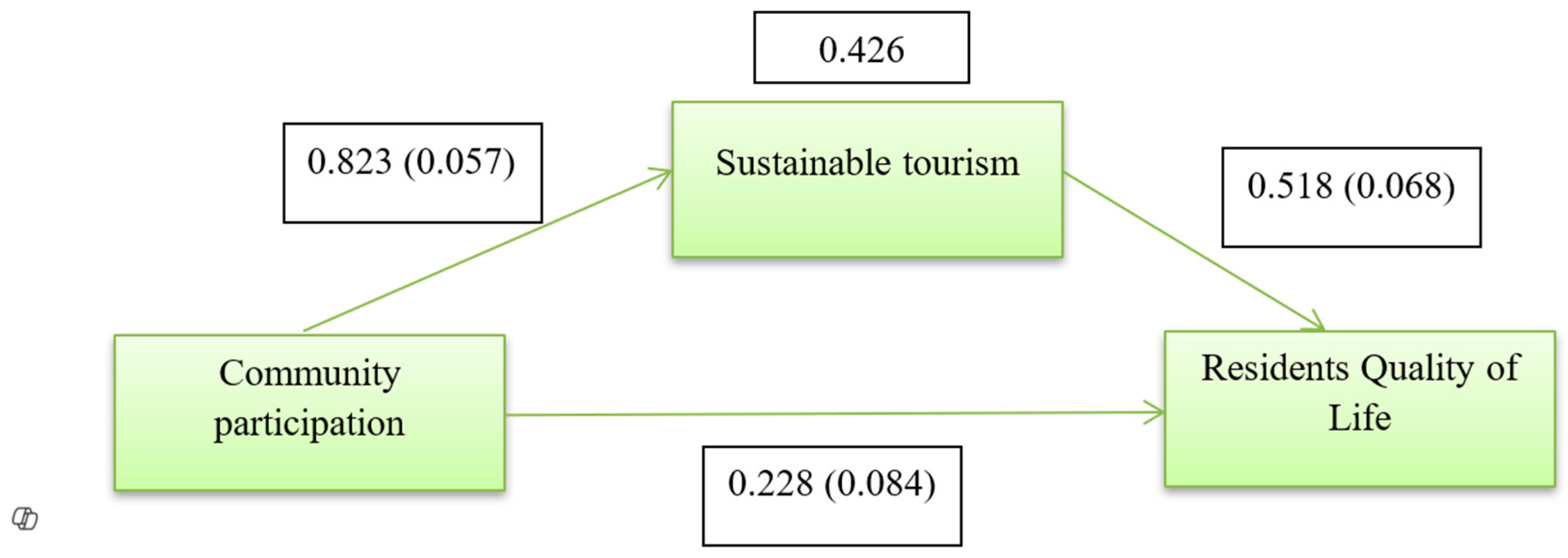

2.7. Moderating Role of Sustainable Tourism Development

3. Materials and Methods

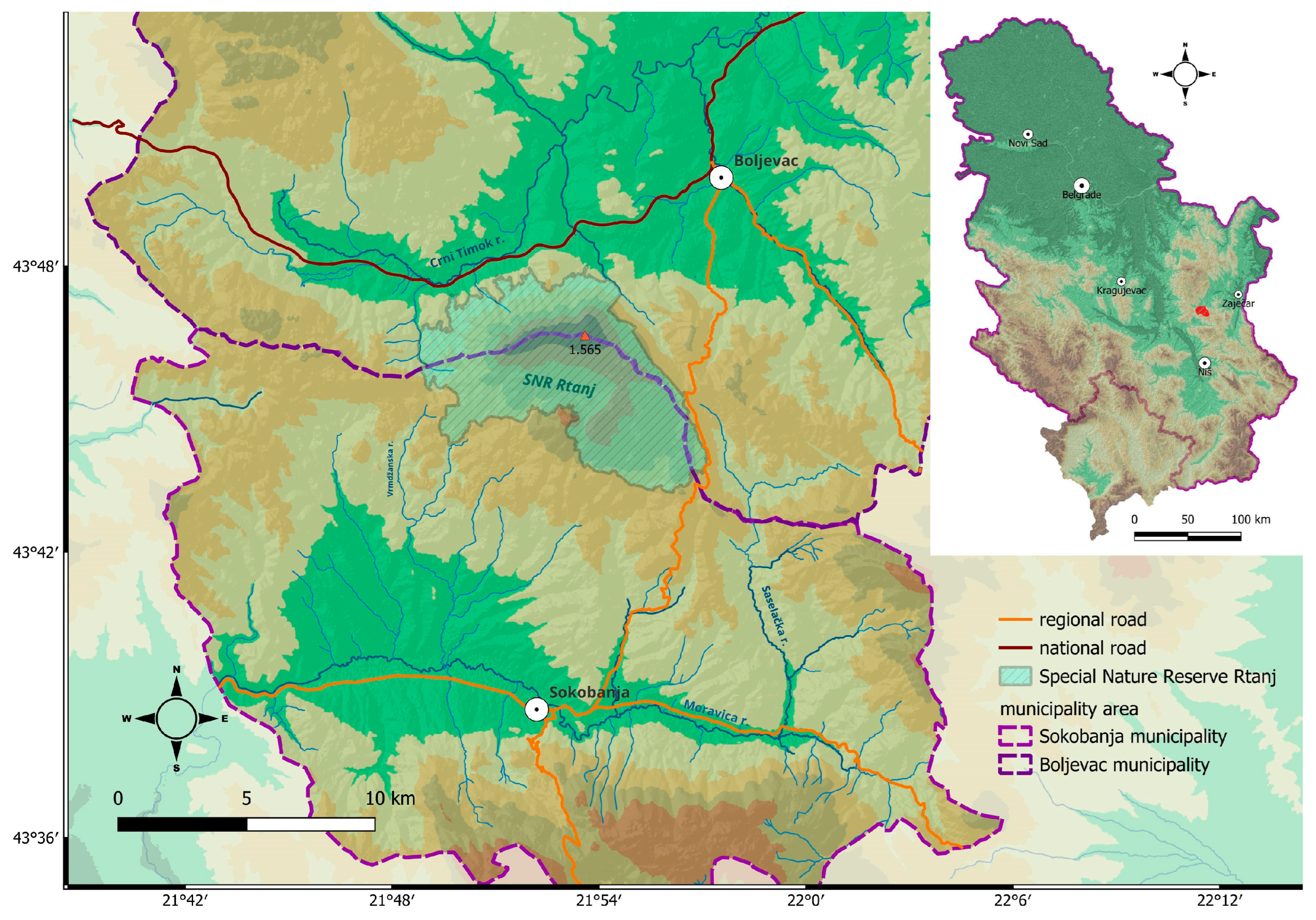

3.1. A Brief Overview of the Case Study

3.2. Study Sample

3.3. Creating and Collecting Questionnaires

3.4. Measurement of Constructs

- −

- “I contribute to conservation programs and tourism development decision-making in my community.”

- −

- “I join activities that are relevant to the promotion of heritage sites.”

- −

- “Tourism increases the community well-being.”

- −

- “I participate in sustainable tourism-related plans and development.”

- −

- “I would be willing to engage in volunteer work regarding the conservation of natural and cultural resources.”

- −

- “Residents believe environmental education is important for preserving geoheritage.”

- −

- “Tourism contributes to the protection of Rtanj’s natural and cultural heritage.”

3.5. Statistical Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, R.; Mehrotra, A.; Mishra, A.; Rana, N.P.; Nunkoo, R.; Cho, M. Four decades of sustainable tourism research: Trends and future research directions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, R.; Xiao, X.; Wei, Z.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y.; Lu, S.; Zheng, C. How to coordinate the use and conservation of natural resources in protected areas: From the perspective of tourists’ natural experiences and environmentally responsible behaviours. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1028508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, R.; Dash, R. Ecotourism, biodiversity conservation and livelihoods: Understanding the convergence and divergence. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2023, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ao, C.; Liu, B.; Cai, Z. Ecotourism and sustainable development: A scientometric review of global research trends. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 2977–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, F.; Padilla, J.; Granobles-Torres, J.C.; Echeverri-Rubio, A.; Botero, C.M.; Suarez, A. Community preferences for participating in ecotourism: A case study in a coastal lagoon in Colombia. Environ. Chall. 2023, 11, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiong, K.; Huang, D. Natural world heritage conservation and tourism: A review. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN—United Nations. The Top 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainable Development Goals 2025. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- de los Angeles Somarriba-Chang, M.; Gunnarsdotter, Y. Local community participation in ecotourism and conservation issues in two nature reserves in Nicaragua. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1025–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, H.; Bires, Z.; Berhanu, K. Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: Evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P. The impact of sustainable tourism on local community cultural heritage conservation awareness in Hanoi. Herit. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 7, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chale, H.A.; Ding, X.-H.; Ahmed, S.M.; Liu, R. Empowering Communities and Advancing Sustainable Eco-Tourism: The Intermediary Function of Community Support for Eco-Tourism. J. Manag. Dev. 2025, 2, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Aziz, N.A.; Mohd Ariffin, N.F.; Ismail, N.A.; Alias, A. Community Participation in the Importance of Living Heritage Conservation and Its Relationships with the Community-Based Education Model towards Creating a Sustainable Community in Melaka UNESCO World Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, T.A.; Cater, C.; Page, S.J. Adventure and ecotourism safety in Queensland: Operator experiences and practice. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gültekin, Y.S. Ecotourism through the perception of forest villagers: Understanding via mediator effects using structural equation modeling. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 70899–70908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lei, S.L. A structural model of residents’ intention to participate in ecotourism: The case of a wetland community. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, M.; Brankov, J.; Ćurčić, N.; Pavlović, S.; Dobričić, M.; Tretiakova, T.N. Protected Natural Areas and Ecotourism—Priority Strategies for Future Development in Selected Serbian Case Studies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, F.G.; Lovelock, B.; Carr, N. Constraints of community participation in protected area-based tourism planning: The case of Malawi. J. Ecotourism 2016, 16, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, P.; Esmaeilzadeh, H.; Sadeghi, S.M.M.; Wolf, I.D.; Deljouei, A. Relationship Analysis of Local Community Participation in Sustainable Ecotourism Development in Protected Areas, Iran. Land 2022, 11, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustini, N.K.; Sri Budhi, M.K.; Setyari, N.P.W.; Setiawina, N.D. Development of sustainable tourism based on local community participation. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. Stud. 2022, 5, 3283–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Marahatta, D.; Devkota, H. Aspects of Community Participation in Eco-tourism: A Systematic Review. J. Multidiscip. Res. Adv. 2024, 2, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginting, N.; Wahid, J. Community Participation in Sustainable Tourism: A Case Study in Balige, Indonesia. Environ. Proc. J. 2023, 8, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjuraman, V.; Hussin, R.; Che Aziz, R. Community-based ecotourism as a social transformation tool for rural community: A victory or a quagmire? J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 39, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.B.; Getz, D. Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyisi, A.; Lee, D.; Trees, K. Facilitating collaboration and community participation in tourism development: The case of south-eastern Nigeria. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Yang, L.; Wang, R.; Dai, M.L. Community participation in tourism employment: A phased evolution model. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 48, 10963480221095722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C.; Wang, J.T.M.; Wu, M.R. Community participation as a mediating factor on residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development and their personal environmentally responsible behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1764–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, L.N.; Thapa, B.; Ko, Y.Y. Residents’ perspectives of a World Heritage Site: The Pitons Management Area, St. Lucia. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, Y.; Karacaer, S.S. Complex Relationships Between Sustainable Tourism Development and Its Antecedents: A Test of Serial Mediation Model. Nat. Resour. Forum 2024, 48, 1436–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Ecotourism: A Means to Safeguard Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functions? Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, O. The Role of Ecotourism in Conservation: Panacea or Pandora’s Box? Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP; UNWTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. Tourism Carrying Capacity: Report on the Senior-Level Expert Group Meeting Held in Paris, June 1990; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing sustainable tourism development: The 2030 agenda and the managerial ecology of sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, M. Heritage Interpretation and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K.; Haufiku, M.S.; Tan, K.L.; Farid Ahmed, M.; Ng, T.F. Systematic Review of Education Sustainable Development in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Calleo, A.; Benedetti, A.C.; Bartolomei, C.; Predari, G. Fostering Resilient and Sustainable Rural Development through Nature-Based Tourism, Digital Technologies, and Built Heritage Preservation: The Experience of San Giovanni Lipioni, Italy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriello, M.A.; Redmore, L.; Sène, A.L.; Katju, D.; Barraclough, L.; Boyd, S.; Madge, C.; Papadopoulos, A.; Yalamala, R.S. The scope of empowerment for conservation and communities. Conserv. Biol. 2025, 39, e14249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobster, P.H.; Floress, K.; Westphal, L.M.; Watkins, C.A.; Vining, J.; Wali, A. Resident and user support for urban natural areas restoration practices. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 203, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B. Environmental Human Rights and Climate Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. Association Analysis on Pro-Environmental Behaviors and Environmental Consciousness in Main Cities of East Asia. Behaviormetrika 2010, 37, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üzülmez, M.; Ercan İştin, A.; Barakazı, E. Environmental Awareness, Ecotourism Awareness and Ecotourism Perception of Tourist Guides. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Staus, N.L. Free-choice learning and ecotourism. In International Handbook on Ecotourism; Packer, J., Ballantyne, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Wheaton, M.; Bowers, A.W.; Hunt, C.A.; Durham, W.H. Nature-based tourism’s impact on environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior: A review and analysis of the literature and potential future research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 838–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y.; Gao, M.; Kim, H.; Shah, K.J.; Pei, S.-L.; Chiang, P.-C. Advances and Challenges in Sustainable Tourism toward a Green Economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavod za Zaštitu Prirode Srbije. Zavod za zaštitu prirode Srbije 2025. Available online: https://zzps.rs/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Gaudenyi, T.; Milošević, M.V. The East Serbian Carpathians: Toward Its Definition, Delineation, and Relation to The South Carpathians. Eur. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 4, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratić, M.; Marjanović, M.; Radivojević, A.; Pavlović, M. M-GAM method in function of tourism potential assessment: Case study of the Sokobanja Basin in Eastern Serbia. Open Geosci. 2020, 12, 1468–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatković, B.K.; Bogosavljević, S.S.; Radivojević, A.R.; Pavlović, M.A. Traditional use of the native medicinal plant resource of Mt. Rtanj (Eastern Serbia): Ethnobotanical evaluation and comparison. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census (Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia). 2022 Census of Population—Ethnicity, Households and Dwellings; Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2022.

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Jepson, A.; Clarke, A.; Ragsdell, G. Investigating the application of the motivation–opportunity–ability model to reveal factors which facilitate or inhibit inclusive engagement within local community festivals. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 14, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ahmad, A.G.; Barghi, R. Community participation in World Heritage Site conservation and tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhiasa, S.; Wakarmamu, T.; Firman, A. Community participation as agent for sustainable tourism: A structural model of tourism development at Bali Province, Indonesia. Int. J. Econ. Res. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Balmford, A.; Green, J.M.H.; Anderson, M.; Beresford, J.; Huang, C.; Naidoo, R.; Walpole, M.; Manica, A. Walk on the Wild Side: Estimating the Global Magnitude of Visits to Protected Areas. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladeji, S.O.; Grace, O.; Ayodeji, A.A. Community Participation in Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage Resources in Yoruba Ethnic Group of South Western Nigeria. Sage Open 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Riyanto, I.; Supriono; Fahmi, M.R.A.; Yuliaji, E.S. The effect of community involvement and perceived impact on residents’ overall well-being: Evidence in Malang marine tourism. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2270800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, C.A.; Morrison, R. Fostering social participation and inclusion in rural communities: The case of the TAIKAN Group in Chile. Challenges 2025, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazani, S.N.; Reynolds, K.J.; Osborne, H. What works and why in interventions to strengthen social cohesion: A systematic review. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 938–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Araoz, E.G.; Gallegos Ramos, N.A.; Paredes Valverde, Y.; Quispe Herrera, R.; Mori Bazán, J. Examining the Relationship between Environmental Education and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Regular Basic Education Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeloro, G.; Tartari, M. Heritage-led sustainable development in rural areas: The case of Vivi Calascio community-based cooperative. Cities 2025, 161, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Selvanathan, E.A.; Bhatia, B.; Greenland, S.; Jayasinghe, M. Well-being and sustainable development: A systematic review and avenues for future research. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Employment | Type of Job | |||

| Male | 39.8% | Student | 8.0% | Agriculture | 3.4% |

| Female | 60.2% | Employed | 72.3% | Public sector | 27.7% |

| Age | Unemployed | 12.9% | Private sector | 33.0% | |

| Average age = 42 Std. = 13.1838 Age range (18–74) | Retiree | 6.8% | Tourism | 6.8% | |

| Household size | Artisan | 3.4% | |||

| Less than three | 32.2% | Nature protection | 4.5% | ||

| Three to five | 55.3% | Other | 21.2% | ||

| More than five | 12.5% | Length of Residency | |||

| Less than 9 years | 9.5% | ||||

| 10–19 years | 10.6% | ||||

| Education | 20–29 years | 19.3% | |||

| Elementary school | 3.0% | 30–39 years | 23.9% | ||

| High school | 36.0% | 40–49 years | 12.1% | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 42.1% | More than 50 years | 24.6% | ||

| Master’s degree/PhD degree | 18.9% | ||||

| Variables | Mean | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | 3.66 | 0.849 | 0.521 | 0.836 |

| RQL | 3.97 | 0.939 | 0.690 | 0.885 |

| STD | 4.01 | 0.932 | 0.525 | 0.777 |

| EAE | 3.37 | 0.820 | 0.513 | 0.829 |

| SC | 3.82 | 0.857 | 0.644 | 0.823 |

| HC | 3.28 | 0.713 | 0.518 | 0.735 |

| CP | RQL | SSTD | EAE | SC | HC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | 0.721 | |||||

| RQL | 0.505 | 0.830 | ||||

| STD | 0.666 | 0.611 | 0.725 | |||

| EAE | 0.500 | 0.433 | 0.414 | 0.716 | ||

| SC | 0.641 | 0.445 | 0.659 | 0.460 | 0.802 | |

| HC | 0.540 | 0.521 | 0.436 | 0.449 | 0.425 | 0.720 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Beta | Std. Error | C.R. (t) | Status of Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CP to SC | 0.641 * | 0.057 | 13.513 | Supported |

| H2 | CP to EAE | 0.500 * | 0.047 | 9.337 | Supported |

| H3 | CP to HC | 0.540 * | 0.051 | 10.390 | Supported |

| H4 | CP TO RQL | 0.505 * | 0.069 | 9.463 | Supported |

| H5 | STD to SC | 0.759 * | 0.039 | 18.855 | Supported |

| H6 | STD to EAE | 0.414 * | 0.040 | 7.366 | Supported |

| H7 | STD to HC | 0.436 * | 0.044 | 7.845 | Supported |

| H8 | SC to RQL | 0.445 * | 0.060 | 8.050 | Supported |

| H9 | EAE to HC | 0.449 * | 0.061 | 8.126 | Supported |

| H10 | EAE to RQL | 0.433 * | 0.082 | 7.781 | Supported |

| H11 | HC to RQL | 0.521 * | 0.070 | 9.881 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Obradović Strålman, S.; Milentijević, N. Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Tourism Through Community Participation: Insights from Mt. Rtanj, Serbia. Land 2026, 15, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010008

Obradović Strålman S, Milentijević N. Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Tourism Through Community Participation: Insights from Mt. Rtanj, Serbia. Land. 2026; 15(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleObradović Strålman, Sanja, and Nikola Milentijević. 2026. "Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Tourism Through Community Participation: Insights from Mt. Rtanj, Serbia" Land 15, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010008

APA StyleObradović Strålman, S., & Milentijević, N. (2026). Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Tourism Through Community Participation: Insights from Mt. Rtanj, Serbia. Land, 15(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/land15010008