Abstract

Rapid human population growth accelerates biodiversity loss through urban habitat fragmentation, yet ecologically informed urban planning can mitigate these effects. This study evaluates whether and how vegetation characteristics, as captured by Earth observation data varies across forest habitats in a small Mediterranean city in Italy. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), the Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI), and Land Surface Temperature (LST) for the Functional Urban Area of Campobasso were derived from multitemporal Landsat 8 imagery (2020–2023) acquired during the growing season and combined with elevation data to account for topographic gradients. Different forest habitats were identified using the regional coeval Carta della Natura (Map of Nature) and were sampled by a random stratified strategy yielding more than 900,000 observations. A linear mixed-effects model was used to model NDVI as a function of NDMI, LST, elevation, and habitat type, while accounting for temporal and spatial dependencies. The model explained a large proportion of NDVI variability (marginal R2 = 0.75; conditional R2 = 0.85), with NDMI emerging as the strongest predictor, followed by weaker effects of LST and elevation. Habitat differences were also evident: oak-dominated forests (i.e., Quercus frainetto, Q. cerris, and Q. pubescens dominated habitats) exhibited the highest NDVI values, while coniferous plantations (i.e., Pinus nigra dominated habitat) had the lowest; forests dominated by Robinia pseudoacacia and riparian Salix alba showed intermediate vegetation greenness values. These results highlight the ecological importance of oak forests in Mediterranean urban landscapes and demonstrate the value of satellite-based monitoring for capturing habitat variability. The reproducible workflow applied here provides a scalable tool to support habitat conservation and planning in urban environments, also accounting for impending climate change scenarios.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of human population is a major driver of biodiversity loss, primarily through the fragmentation and degradation of natural habitats [1], processes that are particularly prevalent in urbanized areas [2]. Although urban areas currently occupy only about 3% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface [3], their ecological footprint extends far beyond their physical boundaries, affecting climate systems, natural resources, biogeochemical cycles, and biodiversity patterns [4]. Accordingly, these impacts can reduce species richness, abundance, and ecological diversity. At the same time, cities also present important opportunities for biodiversity and ecosystem conservation [5]. Strategic urban interventions, such as habitat protection, ecological connectivity through corridors and steppingstones, and the integration of ecological principles into urban planning, can help mitigate biodiversity loss and enhance ecosystem services [6].

Forests within and around cities are more than just remnants of nature in an urban landscape: they regulate microclimates, sequester carbon, and sustain biodiversity, which directly supports human well-being [7,8,9]. In the context of rapid urbanization and accelerating climate change, monitoring the condition of urban and peri-urban vegetation is therefore essential. Reliable information on forest habitats is critical both for tailoring conservation strategies and adaptive management, and for enhancing the provision of ecosystem services in cities. Small and medium-sized Mediterranean cities are particularly interesting in this regard. They often host a mosaic of natural and semi-natural forest habitats surrounding the urban core, which can play a disproportionate role in sustaining regional biodiversity [10,11] but remain poorly studied compared to large metropolitan areas [12,13].

Satellite Remote Sensing (SRS) offers unique opportunities to monitor such habitats in a spatially explicit and repeatable way. By providing standardized, verifiable information across large areas and longtime spans, SRS allows to capture biodiversity indicators and ecological processes that would be impractical to assess solely through field surveys [14]. In urban ecology, multispectral satellite sensors have been the workhorse for decades, and indices derived from them have become indispensable tools [15]. Among these, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is by far the most widely used proxy for vegetation greenness and photosynthetic activity, with more than 17,000 studies published between 1985 and 2021 across an increasingly wide set of disciplines [16]. Complementary indices, such as the Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI), provide information on canopy moisture [17], while Land Surface Temperature (LST) offers insights into vegetation thermal conditions, particularly relevant in urban heat island contexts [18,19]. Together, these metrics may enable a more nuanced characterization of vegetation functioning across different habitat types.

Building on these premises, our study aims to assess whether and how vegetation characteristics, as captured by NDVI, vary across distinct forest habitats within the Functional Urban Area (FUA) of Campobasso, a small Mediterranean city in Southern Italy. Specifically, we addressed the following questions: (i) to what extent do canopy moisture (NDMI), land surface temperature (LST), and elevation explain variation in vegetation greenness (NDVI) across a Mediterranean FUA? and (ii) do forest habitats differ in their NDVI values, and which habitat types exhibit higher levels of canopy greenness?

By integrating Earth observation data with ecological habitat mapping, we contribute to the monitoring of biodiversity in small Mediterranean cities. This approach supports evidence-based conservation and urban planning, while highlighting the ecological value of urban and peri-urban forests as strategic assets for climate adaptation and human well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

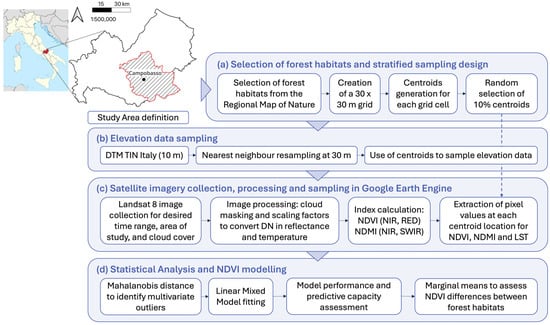

To explore whether and how vegetation, as captured by NDVI, varies across distinct forest habitats in relation to NDMI, LST, and elevation within the FUA of Campobasso, we followed a sequence of steps schematically reported in Figure 1: (a) selection of forest habitats and stratified sampling design; (b) elevation data sampling; (c) satellite imagery collection, processing, and sampling; (d) statistical analysis and NDVI modeling.

Figure 1.

Workflow to assess variations in vegetation features across distinct forest habitats, as captured by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), in relation to Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI), Land Surface Temperature (LST), and elevation within the Functional Urban Area of Campobasso.

2.1. Study Area and Main Forest Habitat Types

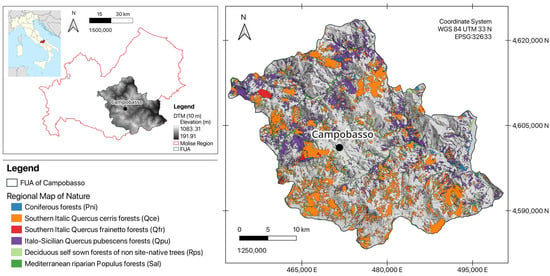

The study was conducted within the Functional Urban Area (FUA) of Campobasso, a small Mediterranean city in the Molise region, Italy (Figure 2). Campobasso is a pilot city in the national framework of Italian Biodiversity Future Center (NBFC). Within this research center there is an interdisciplinary group (Spoke 5: Urban Biodiversity) aimed at improving the current knowledge on biodiversity in Italian cities and providing new insights to protect and improve nature in built-up areas (https://nbfc.it/en/spoke accessed on 24 December 2025).

Figure 2.

Functional Urban Area of Campobasso, a small Mediterranean city in the Molise region, Italy, along with the analyzed forest habitat with EUNIS habitat name and abbreviation code in parentheses.

The concept of FUA, developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the European Commission [20], provides a harmonized framework to delineate urban areas across Europe based on population density and commuting flows [21]. The FUA boundary of Campobasso was derived from the official dataset available on the OECD website [22].

The Campobasso FUA covers 1028 km2 and lies within a hilly to mountainous physiographic context ranging between approximately 190 and 1084 m a.s.l., with the urban area situated at a mean elevation of 701 m a.s.l. The territory, located between the Apennine Range to the west and the Adriatic Sea to the east, belongs to the Apennine ecoregional province and has a temperate sub-mediterranean climate [23,24], characterized by mean annual temperature of 13.3 °C, coldest-month averages between −1 °C and 4 °C, two months exceeding 20 °C, and a mean annual precipitation of 806 mm [25,26]. Land use is defined by a relatively compact urban core embedded in an agricultural matrix with substantial forest cover [27].

According to the Carta della Natura (Map of Nature) program of ISPRA (Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale) [28] and previous research [29], six main forest habitat types were considered, corresponding to EUNIS classification [30]: Southern Italic Quercus cerris forests (Qce), Southern Italic Quercus frainetto forest (Qfr), Italo-Sicilian Quercus pubescens forest (Qpu), Mediterranean riparian Populus forest (Sal), Deciduous self-sown forest of non-native trees (Rps), and Coniferous forest (Pni). These habitats are dominated, respectively, by Quercus cerris L., Q. frainetto Ten., Q. pubescens Willd., Salix alba L., Robinia pseudoacacia L., and Pinus nigra J.F. Arnold. A summary of forest habitat types, their corresponding codes, and dominant species is provided in Table 1. Their spatial distribution within the FUA is reported in Figure 2 (see Supplementary Table S1 for full descriptions of habitats after EUNIS classification and Table S2 for configuration metrics of analyzed forest habitats).

Table 1.

Forest habitat types analyzed in the study, including their dominant tree species and the abbreviation codes (listed in alphabetical order).

Ecologically, these types range from deciduous, meso- to xerothermophilous oak systems to evergreen conifer and riparian softwood forests. Qce are dominated by Quercus cerris, a deciduous, sub-Mediterranean, mesophilous oak forming mixed broadleaf stands on well-drained soils [31]. Qfr are deciduous thermophilous oak woods often found on fertile hillsides with hornbeam or other oaks, including Q. cerris, representing mesophilous oak–hornbeam assemblages ranging from the central–southern Balkans to the southern Apennines [32]. Qpu represent sub-Mediterranean, xerothermophilous oak forests prevailing on shallow calcareous or flysch substrates; Q. pubescens shows high drought tolerance via coordinated anatomical and physiological adjustments (e.g., modulation of vessel traits, stomatal conductance and leaf morpho-anatomy) that enable acclimation to amplified drought scenarios [33,34]. Sal are softwood gallery forests along lowland river corridors dominated by Populus spp. and Salix alba. The structure and function of these forests are tightly constrained by hydrogeomorphic dynamics, with tree growth, water-use efficiency and wood anatomy responding to drought severity and river flow, while S. alba typically relies on shallow sources of soil water in seasonal settings [35,36]. Rps are secondary, even-aged stands dominated by the non-native, Nitrogen-fixing Robinia pseudoacacia; they establish on disturbed, base-rich or urban–agricultural substrates, spread vigorously by root suckering, alter nutrient cycling and understory composition, and can persist as monodominant patches unless actively managed [37,38]. Finally, Pni comprise sub-Mediterranean to montane Pinus nigra plantations. The species is heliophilous, often growing on skeletal calcareous sites. Despite its suitability for restoration on degraded terrain, P. nigra growth is sensitive to warming and hot droughts, with projections indicating declines in basal-area increment across its latitudinal range under future climates and a generally high disturbance exposure in Mediterranean landscapes [39,40].

Beyond structure, these forests underpin distinct biodiversity profiles. Oak-dominated types (Qce, Qfr, Qpu) generally host species-rich and functionally diverse herb–shrub layers tightly linked to overstory composition and stand structure, highlighting how understory diversity contributes to ecosystem functioning [41]. Riparian galleries (Sal)—when in good conservation conditions—often act as local biodiversity hotspots, with higher plant richness and a greater incidence of rare species than adjacent upland woods [42]. By contrast, Rps stands of Robinia pseudoacacia tend to depress native understory and invertebrate diversity relative to native forests [37]. Pni forests—at least in non-plantation conditions—sustain variable understory assemblages modulated by canopy structure and site conditions, with richness and composition tracking overstory attributes [43]. For further climatic description of the study area and ecological characterization of these habitats, see Varricchione et al., 2024 [29].

2.2. Stratified Sampling Design and Elevation Data

To analyze and compare forest types based on SRS ecological variables and elevation data, we implemented a stratified random sampling design to ensure the representativeness of forest habitats, with each forest type defined as a distinct stratum. A 30 × 30 m grid was overlaid across the extent of the Campobasso FUA to match both the scale of the Carta della Natura (1:25,000) and the spatial resolution of the satellite imagery (30 m). The centroid of each grid cell overlapping with forest habitat polygons was computed using QGIS v. 3.34.15.

A random selection of 10% of the centroids was performed to balance computational efficiency with ecological representativeness. This procedure yielded a total of n = 20,539 sampling points, each associated with a forest type and its corresponding polygon identifier.

Elevation was included as a key predictor. In mountain systems, elevation acts as a robust proxy for complex environmental gradients, including temperature lapse rates, solar radiation exposure, and the length of the growing season, all of which are known to strongly influence vegetation productivity [44]. Elevation data were obtained from the TINITALY DTM 1.1 [45], a seamless national digital terrain model with a 10 m spatial resolution. The DTM was resampled to 30 m using nearest-neighbor interpolation to match the spatial resolution of Landsat 8 imagery. The elevation data were then sampled at the sampling point locations.

2.3. Satellite Imagery Collection and Processing

Satellite imagery was processed in Google Earth Engine (GEE) a cloud-computing platform [46]. For this study, we selected Landsat 8 imagery Collection 2 Level 2 (L8) [47] because it uniquely combines multispectral and thermal bands, enabling the simultaneous estimation of vegetation indices as well as LST. Although the native resolution of the TIRS thermal band is 100 m [48] (resampled to 30 m), Landsat 8 remains the highest-resolution freely available source of LST at global scale with a revisit time of 16 days. For the purposes of this study, only the red (RED), near-infrared (NIR), shortwave infrared 1 (SWIR1), and thermal infrared 1 (TIR1) bands were used. Additionally, two quality assessment bands were included: the pixel quality band for cloud cover assessment (QA_PIXEL) and the radiometric saturation quality band (QA_RADSAT).

Imagery was filtered by acquisition date, retaining only scenes captured during the vegetative season (May to October) between 2020 and 2023, and clipped to the extent of the Campobasso FUA. This temporal range was selected to align with the reference date of the Carta della Natura of the region (2021) [28], thus minimizing inconsistencies between habitat classification and SRS data. Only images with less than 70% cloud cover were retained. A complete list of the 81 images resulting from the query and used for analysis, is reported in Table S3. Cloud-contaminated pixels were masked using a bitwise algorithm based on the QA_PIXEL band, and saturated pixels were further removed using the QA_RADSAT band. Following USGS guidelines for Collection 2 Level 2 products [49], the appropriate scaling factors and additive offsets (Table 2) were applied to convert raw digital numbers into surface reflectance and land surface temperature (LST), as follows:

Table 2.

Scaling factors and additive offsets to convert Landsat 8 imagery pixels’ digital number into surface reflectance and land surface temperature values.

As for the LST, since it is given in degrees Kelvin, it was then converted to degrees Celsius.

From the processed imagery, two multispectral indices were computed for each L8 image: (i) the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), calculated as the normalized difference between the reflectance in the NIR and RED spectral bands as

ranging between −1 and +1, with higher values denoting increasing photosynthetic activity and biomass, and (ii) the Normalized Difference Moisture Index (NDMI), computed as the normalized difference between the reflectance in the NIR and SWIR1 bands:

NDMI is a proxy of vegetation water content, typically ranging between −1 and +1, with higher values indicating greater canopy moisture.

Sampling was performed using the GEE function sampleRegions over the stratified point set (see Section 2.2 Stratified Sampling Design), adopting the UTM zone 33N projection (EPSG:32633). Each of the 20,539 sampling points was sampled repeatedly across dates. However, because the bit-wise cloud masking algorithm removed only cloudy pixels at each date, the number of valid samples varies by image. This resulted in a total of 947,864 valid point–date observations containing NDVI, NDMI, and LST. Moreover, for each sampled pixel we retained both sampling point attributes (i.e., sampling point id, forest habitat code, forest polygon id, geometry, elevation), and image metadata required for reproducibility (i.e., acquisition date, system time, and scene cloud cover). Records lacking any of the analysis variables (NDVI, NDMI, or LST) were discarded before export. All valid observations were retained individually. We did not apply temporal aggregation (e.g., averaging or compositing), as preserving intra-seasonal variability was important for the subsequent modeling. Temporal dependence among repeated observations was handled in the statistical analysis using acquisition date as a random intercept (see Section 2.4).

The complete, reproducible GEE workflow in JavaScript, including filters, masking, scaling, index computation, sampling, and export, is publicly available at the following repository: https://code.earthengine.google.com/?accept_repo=users/chabottaro/shared_unimol (accessed on 24 December 2025).

2.4. Statistical Modeling

A linear mixed-effects model (LMM) was used to model NDVI as a function of forest habitat type, NDMI, LST, and elevation. To account for repeated observations across space and time, polygon ID (index_r) and image acquisition date (year–month) were included as random intercepts. The model was fitted using the lmer function of the lme4 R package (v 1.1-36) [50]. Prior to modeling, NDVI, NDMI, LST, and elevation values were standardized to zero mean and unit variance using z-score standardization. This enabled direct comparison of regression coefficients across predictors.

Multivariate outliers were identified using the Mahalanobis distance, computed as

where x is the vector of standardized NDVI, NDMI, and LST values for each observation, μ is the vector of mean values, and S−1 is the inverse of the covariance matrix. Observations exceeding the critical threshold of the chi-square distribution (p < 0.001, df = 3) were considered outliers and excluded from further analysis. This procedure resulted in the removal of 33,795 cases from the original dataset, yielding a final sample size of n = 910,809 observations.

Multicollinearity among standardized continuous predictors (NDMI, LST, Elevation) was evaluated using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), via vif function in car R-package [51]. All VIF values were below 1.2, indicating no multicollinearity concerns.

Residual spatial dependence was evaluated to verify that inference was not driven by unmodelled spatial structure. Pearson residuals were extracted from the final LMM and aggregated at the polygon level (index_r; one mean residual per forest polygon) to avoid pseudo-replication arising from repeated temporal observations at the same spatial location. Distances were computed in a projected metric coordinate reference system (UTM zone 33N; EPSG:32633). Residual spatial dependence was assessed using (i) a Monte-Carlo Moran’s I test based on k-nearest-neighbor weights (k = 10; 999 permutations) and (ii) a Moran’s I correlogram computed using uniformly spaced 0.5 km distance classes up to 40 km and 1000 permutations, reporting both nominal and Benjamini–Hochberg–adjusted p-values. These analyses were used as diagnostics; the main model retained the original random-effects structure to preserve consistency and computational feasibility on the full dataset.

The explanatory power of the fitted model was quantified with marginal R2 (variance explained by fixed effects) and conditional R2 (variance explained by both fixed and random effects). To further evaluate predictive performance, we conducted five-fold cross-validation (K = 5) with the cross_validate function of the cvms R package [52]. To preserve spatial independence between training and testing sets, folds were assigned at the polygon level (index_r). Predictive accuracy was measured in terms of root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE).

To assess differences in NDVI responses between forest habitats, post hoc comparisons of estimated marginal means with 95% confidence intervals (Sidak-adjusted) were computed by using the emmeans R package [53], and compact letter displays were generated with the cld function of the multcomp package [54]. All analysis were conducted in R (v 4.4.3) [55].

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance, Residual Spatial Diagnostics and Predictor Effects

The linear mixed-effects model explained a substantial proportion of the variation in NDVI. The marginal R2, representing the variance explained by fixed effects, was 0.75, whereas the conditional R2, which includes both fixed and random effects, was 0.85. The inclusion of random intercepts for polygon identifier (index_r) and image acquisition date (year–month) accounted for additional spatial and temporal structure in the model. The remaining unexplained variability in NDVI (σ2) represents residual variance not captured by either the fixed or random effects (Table S4).

Residual spatial diagnostics indicated weak but detectable spatial structure. A Monte-Carlo Moran’s I test on polygon-aggregated Pearson residuals showed positive residual autocorrelation (Moran’s I = 0.124; p = 0.001). A residual correlogram revealed that autocorrelation is primarily short-ranged, with positive correlations at small distances that decay toward zero at intermediate distances (overall mean across distance classes: mean I = −0.017). Although a substantial proportion of distance classes was statistically significant, effect sizes were consistently small in magnitude, suggesting limited residual spatial dependence that is unlikely to affect the substantive interpretation of fixed effects.

Cross-validation confirmed the stability of the model, with a mean RMSE of 0.032 ± 0.001 and a mean MAE of 0.025 ± 0.001 across folds. Importantly, cross-validated R2 values (R2m = 0.75, R2c = 0.85) closely matched those obtained from the fitted model, indicating strong generalizability. Among the continuous predictors, NDMI exhibited the strongest positive effect on NDVI, while LST had a smaller positive effect and elevation negative effect (all p < 0.001). Forest habitat type also contributed significantly to NDVI variation (p < 0.001). A complete summary of parameter estimates, and confidence intervals is provided in Supplementary Table S4.

3.2. Difference in NDVI Across Forest Habitats

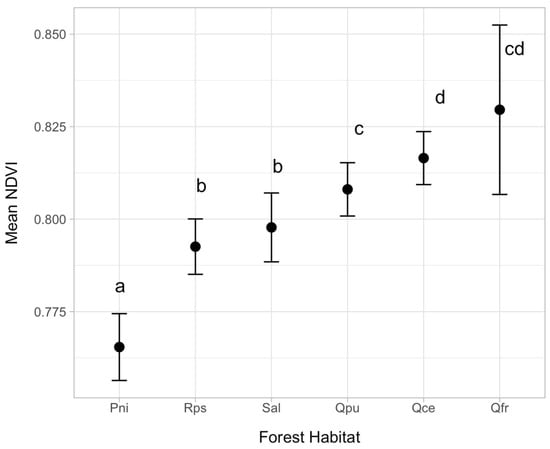

Estimated marginal means revealed clear differences in NDVI among forest habitat types (Figure 3). The lowest values were observed in coniferous forests dominated by Pinus nigra (Pni, mean = 0.765, 95% CI [0.756–0.774]), which formed a distinct group (p < 0.001). Deciduous self-sown forests dominated by Robinia pseudoacacia (Rps, mean = 0.793, 95% CI [0.785–0.800]) and riparian forests dominated by Salix alba (Sal, mean = 0.798, 95% CI [0.788–0.807]) exhibited significantly higher NDVI values than coniferous forests but did not differ significantly from each other.

Figure 3.

Estimated marginal means of NDVI for forest habitat types, adjusted for NDMI, LST, and elevation. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Letters denote statistically similar groups (Sidak-adjusted pairwise comparisons).

Oak-dominated habitats showed the highest NDVI values. Quercus pubescens forests (Qpu, mean = 0.808, 95% CI [0.801–0.815]) had significantly higher values than riparian habitats and deciduous self-sown forests, while Q. cerris forests (Qce, mean = 0.817, 95% CI [0.809–0.824]) exhibited even higher values (group “d”). Southern Italic Q. frainetto forests (Qfr, mean = 0.830, 95% CI [0.807–0.852]) reached the overall highest NDVI, but their confidence intervals overlapped with those of Q. cerris, resulting in partial group overlap. Taken together, these results indicate that oak-dominated habitats consistently exhibit higher NDVI values compared with coniferous plantations, deciduous self-sown forests of non-native trees, and riparian forests.

4. Discussion

4.1. Drivers of NDVI Variability

In both Mediterranean natural forests and the urban forests of the Functional Urban Area of Campobasso, vegetation greenness (NDVI) is mainly driven by canopy moisture content (NDMI), with smaller contributions from land surface temperature (LST) and elevation.

The strong and positive effect of NDMI highlights the central role of canopy water status in determining photosynthetic activity, confirming findings from previous studies that link vegetation moisture to NDVI [56,57]. In Mediterranean forests, higher canopy water content supports photosynthetic capacity by maintaining leaf turgor and enabling sustained stomatal opening under water-limited conditions. Well-hydrated foliage allows greater CO2 diffusion into mesophyll tissues, enhancing carbon assimilation and primary productivity, especially during seasonal drought. Conversely, when water availability declines, stomatal closure and reduced mesophyll conductance inhibit photosynthesis, constraining growth. Empirical work in young Mediterranean mixed stands (e.g., Pinus pinea, Quercus ilex, Juniperus oxycedrus) has shown a strong sensitivity of photosynthetic parameters to leaf water potential and soil moisture [58]. Likewise, measurements in dry and mesic Mediterranean forests confirm that photosynthesis and stomatal conductance decline sharply under reduced water availability [59]. It is important to note that both NDVI and NDMI are indirect proxies of vegetation function, and their relationship partially reflects mathematical dependence due to the shared use of the NIR band. Nonetheless, empirical studies have demonstrated strong correlations between NDVI and canopy structure and photosynthetic potential [60] or leaf area index in Mediterranean forests [61], as well as between NDMI and canopy water content and physiological stress responses [62]. Therefore, while caution is needed when attributing direct physiological meaning to spectral indices, the patterns observed here are consistent with established links between canopy greenness, water status, and productivity in Mediterranean ecosystems.

Our models identified NDMI as the most significant driver of NDVI variability, while LST showed a much weaker, secondary effect. This is statistically coherent, as water availability (NDMI) is widely recognized as the primary limiting factor for photosynthesis in Mediterranean ecosystems, particularly during the growing season [58,59]. The subordinate role of LST can be further interpreted from an ecological perspective. All the analyzed forest habitats, regardless of their specific composition (e.g., Quercus, Pinus, or mixed stands), provide a significant thermal buffering service [63]. This generalized cooling effect relative to the much warmer non-forested urban matrix compresses the range of LST values within our dataset. Although studies have shown that different forest types (e.g., broadleaf vs. coniferous) can produce distinct thermal regimes, these differences are often subtle or primarily dictated by structural attributes like LAI and canopy density rather than species alone [64,65]. This limited thermal variance across our sites makes LST a weaker predictor of NDVI changes compared to the overriding influence of water availability. Thus, our findings suggest that while the thermal buffering role is a comparable ecosystem service across these habitats, their differences in greenness (NDVI) are more closely linked to biodiversity and structural attributes that regulate moisture retention.

The analysis also revealed a negative, albeit weak, relationship between NDVI and elevation. This trend is ecologically consistent with the general principle that higher altitudes experience lower temperatures and shorter growing seasons, which typically constrain vegetation productivity [44].

However, the limited explanatory power of elevation in our models is almost certainly attributable to the modest range within our specific study area. This compressed gradient limits the variable’s statistical leverage. In studies encompassing more pronounced topographic variability, elevation often emerges as a primary driver of vegetation patterns, capable of explaining significant portions of NDVI variance due to strong climatic controls [66]. Our findings therefore suggest that while elevation remains a relevant ecological factor, its statistical contribution becomes secondary in landscapes where other factors, such as water availability (NDMI), exhibit much stronger variability.

4.2. Habitat-Level Differences

Habitat type significantly contributed to NDVI variability, with oak-dominated forests showing consistently higher values than riparian, alien-dominated and coniferous habitats. In particular, Quercus frainetto and Q. cerris forests displayed the highest NDVI, suggesting increased photosynthetic potential under local climatic conditions. Oak forests are characterized by high species richness, hosting several sclerophyllous taxa, which tolerate prolonged aridity and can capture atmospheric moisture even in the absence of rainfall [29,67], as well as, semi-deciduous or late-deciduous species that extend photosynthetic activity into mild autumns through delayed leaf fall [68]. These eco-morphological adaptations promote denser and persistent canopies, enhancing near-infrared reflectance and sustaining higher NDVI values. By contrast, coniferous plantations exhibited the lowest NDVI, a pattern that may reflect both their artificial origin and reduced structural and floristic complexity [69]. Riparian and R. pseudoacacia forests, while greener than coniferous stands, were less productive than oak forests, likely due to their dependence on hydrological dynamics and potential sensitivity to seasonal water availability [70]. The species richness of these habitats is also lower than oaks forest, largely because of the restrictive environmental conditions of riparian strips, where only a limited number of species are well-adapted to withstand frequent flooding [71,72], but most likely also due to the allelopathic effects exerted by the alien species R. pseudoacacia [73]. Moreover, these forests are characterized by a lighter canopy structure and by foliage that is highly vulnerable to seasonal drought stress [74]. In Mediterranean conditions, these species tend to exhibit earlier leaf senescence or a pronounced physiological decline during summer, thereby shortening the period of maximum photosynthetic activity. As a result, they consistently display lower NDVI values.

These findings support the ecological importance of oak forests in maintaining high canopy greenness and primary productivity in Mediterranean landscapes, and the consequent great interest that has received Q. cerris lately [75,76,77]. From a management perspective, canopy greenness (NDVI) is a widely used proxy for stand productivity, physiological performance, and drought resilience [78,79]. Lower NDVI often reflects reduced carbon uptake capacity, simplified stand structure, or higher vulnerability to hydrological stress [80], all of which are key attributes informing forest condition assessments in Mediterranean landscapes.

4.3. Model Performance and Robustness

The LMM framework proved effective in disentangling the effects of environmental gradients and habitat types while accounting for spatial and temporal dependence. The high marginal R2 (0.75) indicates that fixed effects captured the majority of NDVI variation, while random effects associated with polygon identity and acquisition date accounted for additional variability.

Residual spatial diagnostics indicated weak but detectable spatial autocorrelation. However, its magnitude was small and primarily short-ranged. Together with the hierarchical random-effects structure, this suggests that remaining spatial dependence is limited and unlikely to affect the substantive interpretation of fixed-effect estimates.

Consistently, cross-validation confirmed the predictive robustness of the model, as out-of-sample metrics closely matched in-sample performance, indicating absence of overfitting despite the large dataset.

4.4. Implications and Perspectives

From a management perspective, our results emphasize the functional importance of oak-dominated forests as key habitats sustaining vegetation greenness. These native broadleaf systems are critical as they typically host a high biodiversity well-adapted to fluctuating Mediterranean conditions, which is foundational to their resilience despite the ever-growing evidence of oak-decline in the Mediterranean [81]. Similarly, riparian forests emerged as hotspots of productivity, a finding consistent with their high NDMI values. These habitats act as essential green corridors and microclimatic buffers in fragmented peri-urban landscapes, and their preservation is paramount for maintaining connectivity and biodiversity-related ecosystem services [82].

Conversely, the coniferous plantations in our study displayed significantly lower NDVI. This suggests a reduced capacity for primary production and related services. This finding aligns with evidence from other Mediterranean areas, where monospecific coniferous stands, often resulting from past afforestation policies, can exhibit lower functional diversity and reduced resilience to disturbances such as extreme drought compared to native mixed or broadleaf forests [83,84].

The methodological framework applied here, integrating satellite-derived vegetation metrics, open-access cloud platforms, and mixed-effects modeling, is replicable in other urban and peri-urban areas, providing a scalable tool for habitat monitoring and prioritizing conservation efforts under global change scenarios [85,86].

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the robustness of our approach, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, NDVI and NDMI are indirect proxies of several vegetation functions and properties rather than direct physiological measurements [87]. In addition, these indices may saturate in dense canopies, potentially underestimating differences among habitats, especially during the peak growing season when greenness and moisture levels approach their upper limits [88].

While recent field campaigns in the region have produced valuable forest structural and compositional data [29], stand-level measures of leaf area index for Quercus cerris [76] and carbon stocks for oak stands [89], these datasets were not designed for the calibration or physiological validation of spectral indices. A promising direction for future research in the region would be to integrate targeted field measurements with satellite data to calibrate models that translate spectral metrics into more explicit physiological information. In this respect, Landsat 8 provides reliable and well-calibrated spectral and thermal data [48], and despite the relatively coarse spatial detail of its TIR sensor, it remains one of the most robust sources for land surface temperature estimation at landscape scales.

From a modeling perspective, although weak and short-ranged residual spatial dependence was detected, its influence on inference is mitigated by the hierarchical structure of the model and the use of spatially blocked validation. Future work could explore alternative sampling densities, incorporate additional predictors (e.g., soil type, stand age, stand density or disturbance history) to refine habitat-level assessments, or explicitly model spatial correlation structures where computationally feasible.

Finally, the modeling framework is spatially structured and could be extended to generate spatially explicit maps of predicted NDVI. Such outputs could be integrated with spatial prioritization or decision-support tools to identify areas where habitat functioning is comparatively low (e.g., coniferous plantations), or where conservation actions should be targeted, (e.g., riparian corridors). In addition, future work could couple these spatially explicit functional indicators with landscape connectivity or fragmentation analyses, enabling a joint assessment of habitat functioning and structural connectivity in urban and peri-urban forest networks. This would further enhance the operational value of the analysis for land managers and urban planners.

5. Conclusions

This study combined satellite-derived vegetation indices with mixed-effects modeling to assess the drivers of NDVI variability across forest habitats within the Campobasso Functional Urban Area. Results highlighted canopy moisture (NDMI) as the dominant predictor of NDVI, with smaller contributions from LST and elevation. Habitat type also played a key role, with oak-dominated forests sustaining the highest levels of greenness compared to riparian stands and coniferous plantations. The modeling framework demonstrated strong explanatory power and predictive accuracy, underscoring the reliability of integrating satellite multispectral data with statistical modeling in habitat monitoring.

By evidencing the functional importance of oak forests and the comparatively lower greenness of coniferous plantations, our findings provide valuable insights for prioritizing restoration efforts, guiding the management of coniferous plantations, and supporting the conservation of native oak and riparian forests in Mediterranean peri-urban landscapes. The approach is broadly transferable and offers a replicable pathway for monitoring vegetation function in other urban and peri-urban contexts under changing environmental conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15010057/s1, Table S1: Classification and description of analyzed forest habitats; Table S2: Configuration metrics of the analyzed Forest habitats; Table S3: List of Landsat 8 Collection 2 Level 2 imagery used for analysis; Table S4: Results of the linear mixed-effects modeling of NDVI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., M.F., M.I., M.L.C. and G.S.; methodology, C.B., M.F., M.I., M.L.C. and G.S.; software, C.B.; validation, M.I.; formal analysis, C.B. and M.I.; investigation, C.B.; data curation, C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.; writing—review and editing, C.B., M.F., M.I., M.V., M.L.C. and G.S.; visualization, C.B.; funding acquisition, M.L.C. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Recovery and Resilience Plan, Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4—Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU; grant number: Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP D43C22001250001, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC”.

Data Availability Statement

The Map of Nature “Carta della Natura” is available upon request at the following website (in Italian) https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/servizi/sistema-carta-della-natura/servizi-al-cittadino-1/modulo (accessed on 24 December 2025). Satellite data collection, processing and exporting is available through Google Earth Engine Platform at the following repository https://code.earthengine.google.com/?accept_repo=users/chabottaro/shared_unimol (accessed on 24 December 2025). Other data will be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the three reviewers and the editors for their constructive comments, which have remarkably helped us improve the original version of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Van Vliet, J. Direct and Indirect Loss of Natural Area from Urban Expansion. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzialetti, F.; Gamba, P.; Sorriso, A.; Carranza, M.L. Monitoring Urban Expansion by Coupling Multi-Temporal Active Remote Sensing and Landscape Analysis: Changes in the Metropolitan Area of Cordoba (Argentina) from 2010 to 2021. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Center WAD|World Atlas of Desertification. Available online: https://wad.jrc.ec.europa.eu/urbanplanet (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Kronenberg, J.; Andersson, E.; Elmqvist, T.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Xue, J.; Khmara, Y. Cities, Planetary Boundaries, and Degrowth. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e234–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotswood, E.N.; Beller, E.E.; Grossinger, R.; Grenier, J.L.; Heller, N.E.; Aronson, M.F.J. The Biological Deserts Fallacy: Cities in Their Landscapes Contribute More than We Think to Regional Biodiversity. BioScience 2021, 71, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, S.; Aronson, M.F.J.; Carpenter, E.; Herrera-Montes, A.; Jung, K.; Kotze, D.J.; La Sorte, F.A.; Lepczyk, C.A.; MacGregor-Fors, I.; MacIvor, J.S.; et al. A Research Agenda for Urban Biodiversity in the Global Extinction Crisis. BioScience 2021, 71, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Scopelliti, M.; Lafortezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Ferrini, F.; Salbitano, F.; Agrimi, M.; Portoghesi, L.; Semenzato, P.; Sanesi, G. Go Greener, Feel Better? The Positive Effects of Biodiversity on the Well-Being of Individuals Visiting Urban and Peri-Urban Green Areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livesley, S.J.; McPherson, E.G.; Calfapietra, C. The Urban Forest and Ecosystem Services: Impacts on Urban Water, Heat, and Pollution Cycles at the Tree, Street, and City Scale. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.; Jasrai, Y.T. Urban Green Patches As Carbon Sink: Gujarat University Campus, Ahmedabad. J. Fundam. Appl. Life Sci. 2013, 3, 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, R.; Catalano, C.; Pasta, S. Beyond Urban Forests: The Multiple Functions and the Overlooked Role of Semi-Natural Ecosystems in Mediterranean Cities. Diversity 2024, 16, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, J.Z.; Hoyk, E.; de Morais, M.B.; Csomós, G. A Systematic Review of Urban Green Space Research over the Last 30 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega-Brodsky, C.C.; Aronson, M.F.J.; Piana, M.R.; Carpenter, E.-S.; Hahs, A.K.; Herrera-Montes, A.; Knapp, S.; Kotze, D.J.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Moretti, M.; et al. Urban Biodiversity: State of the Science and Future Directions. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.; Jin, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, P. Evaluation and Obstacle Analysis of Sustainable Development in Small Towns Based on Multi-Source Big Data: A Case Study of 782 Top Small Towns in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettorelli, N.; Laurance, W.F.; O’Brien, T.G.; Wegmann, M.; Nagendra, H.; Turner, W. Satellite Remote Sensing for Applied Ecologists: Opportunities and Challenges. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 51, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finizio, M.; Pontieri, F.; Bottaro, C.; Di Febbraro, M.; Innangi, M.; Sona, G.; Carranza, M.L. Remote Sensing for Urban Biodiversity: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y. Bibliometric Analysis of Global NDVI Research Trends from 1985 to 2021. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Sader, S.A. Comparison of Time Series Tasseled Cap Wetness and the Normalized Difference Moisture Index in Detecting Forest Disturbances. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 94, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ren, Z.; Chang, X.; Wang, G.; Hong, X.; Dong, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.; Wang, W. Understanding the Cooling Capacity and Its Potential Drivers in Urban Forests at the Single Tree and Cluster Scales. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 93, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaab, J.; Meier, R.; Mussetti, G.; Seneviratne, S.; Bürgi, C.; Davin, E.L. The Role of Urban Trees in Reducing Land Surface Temperatures in European Cities. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Redefining “Urban”. A New Way to Measure Metropolitan Areas; OECD: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H.; Veneri, P. The EU-OECD Definition of a Functional Urban Area; OECD Regional Development Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 2019/11. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Definition of Cities and Functional Urban Areas. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/datasets/oecd-definition-of-cities-and-functional-urban-areas.html (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Blasi, C.; Capotorti, G.; Copiz, R.; Guida, D.; Mollo, B.; Smiraglia, D.; Zavattero, L. Classification and Mapping of the Ecoregions of Italy. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2014, 148, 1255–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, C.; Capotorti, G.; Copiz, R.; Mollo, B. A First Revision of the Italian Ecoregion Map. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2018, 152, 1201–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, L.; Matzarakis, A. Influence of Height/Width Proportions on the Thermal Comfort of Courtyard Typology for Italian Climate Zones. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 29, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaresi, S.; Biondi, E.; Casavecchia, S. Bioclimates of Italy. J. Maps 2017, 13, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angeli, C.; Ceralli, D.; Varricchione, M.; Carranza, M.; De Francesco, M.C.; Innangi, M.; Santoianni, L.; Stanisci, A. Carta Della Natura at Local Scale as a Tool for Urban Biodiversity Monitoring: The Case Study Of Campobasso. Reticula 2024, 35, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ceralli, D.; Laureti, L. Carta Della Natura Della Regione Molise: Cartografia e Valutazione Degli Habitat Alla Scala 1:25.000; Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA): Rome, Italy, 2021; p. 127.

- Varricchione, M.; Carranza, M.L.; D’Angeli, C.; de Francesco, M.C.; Innangi, M.; Santoianni, A.L.; Stanisci, A. Exploring the Distribution Pattern of Native and Alien Forests and Their Woody Species Diversity in a Small Mediterranean City. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2024, 158, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency EUNIS. Habitat Types Search. Available online: https://eunis.eea.europa.eu/habitats.jsp (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Lados, B.B.; Benke, A.; Borovics, A.; Köbölkuti, Z.A.; Molnár, C.É.; Nagy, L.; Tóth, E.G.; Cseke, K. What We Know about Turkey Oak (Quercus cerris L.)—From Evolutionary History to Species Ecology. Forestry 2024, 97, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, G.; Blasi, C.; Paura, B.; Scoppola, A.; Spada, F. Phytoclimatic Characterization of Quercus frainetto Ten. Stands in Peninsular Italy. Vegetatio 1990, 90, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laoué, J.; Gea-Izquierdo, G.; Dupouyet, S.; Conde, M.; Fernandez, C.; Ormeño, E. Leaf Morpho-Anatomical Adjustments in a Quercus pubescens Forest after 10 Years of Partial Rain Exclusion in the Field. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodnik, D.; Gričar, J.; Lavrič, M.; Ferlan, M.; Hafner, P.; Eler, K. Anatomical and Physiological Adjustments of Pubescent Oak (Quercus Pubescens Willd.) from Two Adjacent Sub-Mediterranean Ecosites. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 165, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, J.J.; Colangelo, M.; Rodríguez-González, P.M. Tree Growth, Wood Anatomy and Carbon and Oxygen Isotopes Responses to Drought in Mediterranean Riparian Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 529, 120710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, J.; Tetzlaff, D.; Dubbert, M.; Dubbert, D.; Smith, A.; Soulsby, C. Xylem Water in Riparian Willow Trees (Salix alba) Reveals Shallow Sources of Root Water Uptake by in Situ Monitoring of Stable Water Isotopes. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 2073–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítková, M.; Müllerová, J.; Sádlo, J.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P. Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) Beloved and Despised: A Story of an Invasive Tree in Central Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 384, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítková, M.; Sádlo, J.; Roleček, J.; Petřík, P.; Sitzia, T.; Müllerová, J.; Pyšek, P. Robinia pseudoacacia-Dominated Vegetation Types of Southern Europe: Species Composition, History, Distribution and Management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 134857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel-Pérez, D.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; García-Cervigón, A.I.; Tíscar, P.A.; Andivia, E.; Bose, A.K.; Sánchez-Salguero, R.; Camarero, J.J.; Linares, J.C. Forest Structure Drives the Expected Growth of Pinus nigra along Its Latitudinal Gradient under Warming Climate. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacek, Z.; Cukor, J.; Vacek, S.; Gallo, J.; Bažant, V.; Zeidler, A. Role of Black Pine (Pinus nigra J. F. Arnold) in European Forests Modified by Climate Change. Eur. J. For. Res. 2023, 142, 1239–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, S.; Gosselin, F.; Balandier, P. Influence of Tree Species on Understory Vegetation Diversity and Mechanisms Involved—A Critical Review for Temperate and Boreal Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 254, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielech, R. Plant Species Richness in Riparian Forests: Comparison to Other Forest Ecosystems, Longitudinal Patterns, Role of Rare Species and Topographic Factors. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 496, 119400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, O.Y.; Yılmaz, H.; Akyüz, Y.F. Effects of the Overstory on the Diversity of the Herb and Shrub Layers of Anatolian Black Pine Forests. Eur. J. For. Res. 2018, 137, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. The Use of ‘Altitude’ in Ecological Research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarquini, S.; Isola, I.; Favalli, M.; Battistini, A.; Dotta, G. TINITALY, a Digital Elevation Model of Italy with a 10 Meters Cell Size; Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV): Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS EROS Archive-Landsat Archives-Landsat 8-9 OLI/TIRS Collection 2 Level-2 Science Products|U.S. Geological Survey. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-landsat-archives-landsat-8-9-olitirs-collection-2-level-2 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Wenny, B.N.; Helder, D.; Hong, J.; Leigh, L.; Thome, K.J.; Reuter, D. Pre- and Post-Launch Spatial Quality of the Landsat 8 Thermal Infrared Sensor. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 1962–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey How Do I Use a Scale Factor with Landsat Level-2 Science Products? Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/how-do-i-use-a-scale-factor-landsat-level-2-science-products (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, L.R.; Zachariae, H.B.; Patil, I.; Lüdecke, D. Cvms, version 2.0.0. Cross-Validation for Model Selection. CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Lenth, R.V. Emmeans, version 2.0.1. Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means. CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P.; Heiberger, R.M.; Schuetzenmeister, A.; Scheibe, S. Multcomp, version 1.4-29. Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models. CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bchir, A.; Masmoudi-Charfi, C. Estimating and Mapping NDVI and NDMI Indexes by Remote Sensing of Olive Orchards in Different Tunisian Regions. In Recent Advances in Environmental Science from the Euro-Mediterranean and Surrounding Regions, Proceedings of the Euro-Mediterranean Conference for Environmental Integration (EMCEI-3), Sousse, Tunisia, 20–25 November 2021; Ksibi, M., Negm, A., Hentati, O., Ghorbal, A., Sousa, A., Rodrigo-Comino, J., Panda, S., Lopes Velho, J., El-Kenawy, A.M., Perilli, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 515–518. [Google Scholar]

- Karan, S.K.; Samadder, S.R.; Maiti, S.K. Assessment of the Capability of Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques for Monitoring Reclamation Success in Coal Mine Degraded Lands. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoral, C.; Calama, R.; Sánchez-González, M.; Pardos, M. Modelling the Influence of Light, Water and Temperature on Photosynthesis in Young Trees of Mixed Mediterranean Forests. New For. 2015, 46, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llusia, J.; Roahtyn, S.; Yakir, D.; Rotenberg, E.; Seco, R.; Guenther, A.; Peñuelas, J. Photosynthesis, Stomatal Conductance and Terpene Emission Response to Water Availability in Dry and Mesic Mediterranean Forests. Trees 2016, 30, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J.A.; Field, C.B.; Goulden, M.L.; Griffin, K.L.; Hartley, A.E.; Joel, G.; Penuelas, J.; Valentini, R. Relationships Between NDVI, Canopy Structure, and Photosynthesis in Three Californian Vegetation Types. Ecol. Appl. 1995, 5, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, A.; Salvati, R.; Manes, F. Comparing Leaf Area Index Estimates in a Mediterranean Forest Using Field Measurements, Landsat 8, and Sentinel-2 Data. Ecol. Process. 2023, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusig, D.; Petruzzellis, F.; Tomasella, M.; Napolitano, R.; Altobelli, A.; Nardini, A.; Marusig, D.; Petruzzellis, F.; Tomasella, M.; Napolitano, R.; et al. Correlation of Field-Measured and Remotely Sensed Plant Water Status as a Tool to Monitor the Risk of Drought-Induced Forest Decline. Forests 2020, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Bari, E. Examining the Relationship between Land Surface Temperature and Landscape Features Using Spectral Indices with Google Earth Engine. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Frenne, P.; Lenoir, J.; Luoto, M.; Scheffers, B.R.; Zellweger, F.; Aalto, J.; Ashcroft, M.B.; Christiansen, D.M.; Decocq, G.; De Pauw, K.; et al. Forest Microclimates and Climate Change: Importance, Drivers and Future Research Agenda. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2279–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, W.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, J.; Cao, Y.; Chen, L. Comparative Analysis of Two Methods for Valuing Local Cooling Effect of Forests in Inner Mongolia Plateau. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalefa, E.; Pepin, N.; Teeuw, R. Long-Term Vegetation Trends and Driving Factors of NDVI Change on the Slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 81, 2027–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussotti, F.; Ferrini, F.; Pollastrini, M.; Fini, A. The Challenge of Mediterranean Sclerophyllous Vegetation under Climate Change: From Acclimation to Adaptation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 103, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratani, L.; Catoni, R.; Varone, L. Morphological, Anatomical and Physiological Leaf Traits of Q. Ilex, P. Latifolia, P. Lentiscus, and M. Communis and Their Response to Mediterranean Climate Stress Factors. Bot. Stud. 2013, 54, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, A.; Csilléry, K.; Klisz, M.; Lévesque, M.; Heinrichs, S.; Cailleret, M.; Andivia, E.; Madsen, P.; Böhenius, H.; Cvjetkovic, B.; et al. Risks, Benefits, and Knowledge Gaps of Non-Native Tree Species in Europe. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 908464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, M.M.; Stella, J.C.; Roberts, D.A.; Singer, M.B. Groundwater Dependence of Riparian Woodlands and the Disrupting Effect of Anthropogenically Altered Streamflow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2026453118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaffarelli, G.; Vagge, I. Cities vs Countryside: An Example of a Science-Based Peri-Urban Landscape Features Rehabilitation in Milan (Italy). Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 128002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giupponi, L.; Borgonovo, G.; Leoni, V.; Zuccolo, M.; Bischetti, G.B. Vegetation and Water of Lowland Spring-Wells in Po Plain (Northern Italy): Ecological Features and Management Proposals. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 30, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Kato, M. Invasive Characteristics of Robinia pseudoacacia and Its Impacts on Species Diversity. Diversity 2024, 16, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, A.P.; Gonçalves, J.F.; Durance, I.; Vieira, C.; Honrado, J. Riparian Forest Response to Extreme Drought Is Influenced by Climatic Context and Canopy Structure. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimková, M.; Vacek, S.; Šimůnek, V.; Vacek, Z.; Cukor, J.; Hájek, V.; Bílek, L.; Prokůpková, A.; Štefančík, I.; Sitková, Z.; et al. Turkey Oak (Quercus cerris L.) Resilience to Climate Change: Insights from Coppice Forests in Southern and Central Europe. Forests 2023, 14, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, L.; Di Marzio, P.; Fortini, P. Quercus cerris Leaf Functional Traits to Assess Urban Forest Health Status for Expeditious Analysis in a Mediterranean European Context. Plants 2025, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantozzi, D.; Sferra, G.; Trupiano, D.; Scippa, G.S. Design and Application of Species-Specific Primers to Quercus cerris Roots’ Identification in Urban Forests. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recanatesi, F.; Giuliani, C.; Ripa, M.N.; Recanatesi, F.; Giuliani, C.; Ripa, M.N. Monitoring Mediterranean Oak Decline in a Peri-Urban Protected Area Using the NDVI and Sentinel-2 Images: The Case Study of Castelporziano State Natural Reserve. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buras, A.; Rammig, A.; Zang, C.S. The European Forest Condition Monitor: Using Remotely Sensed Forest Greenness to Identify Hot Spots of Forest Decline. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 689220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Rammig, A.; Blickensdörfer, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.X.; Buras, A. Species-Specific Responses of Canopy Greenness to the Extreme Droughts of 2018 and 2022 for Four Abundant Tree Species in Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 177938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentilesca, T.; Camarero, J.J.; Colangelo, M.; Nolè, A.; Ripullone, F. Drought-Induced Oak Decline in the Western Mediterranean Region: An Overview on Current Evidences, Mechanisms and Management Options to Improve Forest Resilience. iForest Biogeosci. For. 2017, 10, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Zina, V.; Duarte, G.; Aguiar, F.C.; Rodríguez-González, P.M.; Ferreira, M.T.; Fernandes, M.R. Riparian Ecological Infrastructures: Potential for Biodiversity-Related Ecosystem Services in Mediterranean Human-Dominated Landscapes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo-Navascues, M.; Martínez del Castillo, E.; Tejedor, E.; Serrano-Notivoli, R.; Longares, L.A.; Saz, M.A.; Novak, K.; de Luis, M. The Imprint of Droughts on Mediterranean Pine Forests. Forests 2022, 13, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Pérez, J.M.; Carreño, M.F.; Esteve-Selma, M.Á. Enhancing the Resilience of a Mediterranean Forest to Extreme Drought Events and Climate Change: Pinus—Tetraclinis Forests in Europe. Forests 2021, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantero, G.; Morresi, D.; Marzano, R.; Motta, R.; Mladenoff, D.J.; Garbarino, M. The Influence of Land Abandonment on Forest Disturbance Regimes: A Global Review. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2723–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomou, A.D.; Proutsos, N.D.; Karetsos, G.; Tsagari, K. Effects of Climate Change on Vegetation in Mediterranean Forests: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 2, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Tang, L.; Hupy, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Shao, G. A Commentary Review on the Use of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) in the Era of Popular Remote Sensing. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhong, R.; Yan, K.; Ma, X.; Chen, X.; Pu, J.; Gao, S.; Qi, J.; Yin, G.; Myneni, R.B. Evaluating the Saturation Effect of Vegetation Indices in Forests Using 3D Radiative Transfer Simulations and Satellite Observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antenucci, E.; Di Pirro, E.; di Cristofaro, M.; Garfì, V.; Marchetti, M.; Lasserre, B. Beneficial or Impactful Management? Life Cycle Assessment and i-Tree Canopy to Evaluate the Net Environmental Benefits of Mediterranean Urban Forests. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 107, 128800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.