Abstract

Urban heat islands (UHIs) represent a major environmental challenge, particularly in cities with complex topography and local air dynamics where spatial variability of the surface temperature is difficult to model. This study presents an enhanced UHI modeling framework that integrates Random Forest regression with Regression Kriging (RF–RK) in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Using a network of 36 air temperature sensors and spatial predictors such as urban environment and location parameters, we evaluated the performance of RF–RK against traditional Multiple Linear Regression (MLR). Results show that RF–RK achieved substantially higher accuracy (R2 = 0.844, RMSE = 0.241 °C) compared to MLR (R2 = 0.653, RMSE = 0.359 °C). Spatial patterns revealed that a notable thermal gradient can be seen between the western and eastern parts of the city and the extension of the heat island core eastward. The combined approach effectively captured both the non-linear relationships of predictors and the spatial autocorrelation of residuals, outperforming single-method models. These findings highlight the potential of hybrid machine learning–geostatistical frameworks for urban climate research and provide insights for urban planning and heat mitigation strategies in topographically diverse cities.

1. Introduction

Urban heat islands (UHIs) are among the most studied local manifestations of climate change, reflecting the combined influence of urban morphology, land cover, and anthropogenic heat emissions on near-surface air temperatures. Luke Howard is generally regarded as the first to describe the Urban Heat Island phenomenon, while Oke aid the modern theoretical foundation for UHI studies. Since the pioneering work of Howard [1] and Oke [2], extensive research has documented the intensity, drivers, and impacts of UHIs across a wide range of cities worldwide. Early studies were primarily descriptive, focusing on temperature contrasts between urban and rural sites, while recent work has increasingly applied advanced statistical and geospatial approaches to capture the spatial heterogeneity of UHI patterns. Understanding this heterogeneity is crucial, as UHIs influence energy demand, air quality, and public health risks, and their impacts are expected to intensify under ongoing climate change and rapid urbanization. UHIs not only increase thermal discomfort for residents but also contribute to higher energy consumption, intensified air pollution, and amplified climate change effects [3,4,5].

Medium-sized cities with diverse topographies present unique challenges in mapping and managing UHIs [2]. Complex topography can significantly influence the spatial distribution of temperatures, creating variations that are difficult to capture using traditional interpolation methods [5].

Combined modeling techniques using machine learning algorithms (ML) and geostatistical interpolation methods (Regression Kriging) provide more accurate estimates for the prediction of variables of interest in space and time. In many recent studies, combined methods are applied to monitor and evaluate different types of environmental variables, such as physical–chemical characteristics and digital soil mapping [6,7,8,9,10], mapping of aboveground biomass of forests [11] estimation of geological characteristics [12], water levels of the shallow groundwater system [13], land price estimation and mapping [14].

Current methods for UHI mapping often involve traditional geostatistical techniques such as SPLINE function, IDW, ordinary and universal kriging, etc., which interpolate spatial data based on the assumption of spatial autocorrelation. Mesoscale urban climate modeling has been widely employed to simulate urban atmospheric processes, particularly the influence of urban surfaces and canopy structures on temperature and wind fields. The Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model [15] features urban canopy schemes such as the bulk parameterization, the Single-Layer Urban Canopy Model (SLUCM) [16], and the Multi-Layer Urban Canopy Model (MLUCM) [17], providing increasing levels of urban detail and complexity in regional climate simulations. At finer spatial scales, microscale models with building-level resolution, such as PALM [18,19], MITRAS [20], and ENVI-met [21], explicitly represent urban morphology and surface–atmosphere interactions, enabling detailed analyses of local-scale urban heat island processes. Recent review work demonstrates the growing importance of coupling complex urban schemes with observational alignment for accurate urban weather modeling [22], with many scenario experiments focused on urban heat island effects.

The necessity for high-resolution climate information to inform regional impact studies has driven the rapid development of statistical downscaling techniques. Machine Learning (ML) approaches, such as Random Forests (RF) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), have proven particularly effective in capturing the complex, non-linear relationships between coarse-resolution General Circulation Model (GCM) outputs and local observations [23]. These models excel at mapping large-scale atmospheric patterns (predictors) onto local climate variables (predictands) with exceptional accuracy, offering a robust and computationally efficient alternative to traditional regression methods [24,25]. Furthermore, the application of more advanced deep learning techniques, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), shows increasing promise for handling the spatial coherence inherent in climate fields, leading to state-of-the-art downscaling performance [26].

However, these methods can fall short in accurately capturing the complex interactions between urban morphology, topography, and temperature variations. Machine learning algorithms, such as Random Forest (RF), have been increasingly employed to enhance prediction accuracy by handling non-linear relationships and interactions between variables. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of combining machine learning techniques with geostatistical methods to improve the spatial accuracy of UHI models. High-resolution urban climate mapping, essential for micro-scale planning and mitigation strategies, has been significantly advanced by statistical Machine Learning (ML) techniques. Hybrid approaches, notably Regression-Kriging (RK) that incorporates ML models such as Random Forest (RF), have emerged as state-of-the-art tools for accurately mapping complex thermal fields like the Urban Heat Island (UHI) [27]. These methods efficiently model the non-linear relationship between local air temperature (or Land Surface Temperature) and a wide array of high-resolution spatial predictors, including detailed land cover (e.g., Local Climate Zones, LCZ), topographic features, and urban geometry [28]. By leveraging the predictive power of ML and combining it with the spatial error correction capabilities of kriging, these hybrid statistical models generate robust, continuous, fine-scale climate surfaces, offering superior performance compared to traditional geostatistical or multivariate regression techniques alone. The RF model was successfully used by to predict air temperature in Nanjing, China [29], using independent variables such as landcover, impervious surface, surface albedo, and anthropogenic heat flux. For a large ensemble of French cities an RF model and a regression-based model to forecast nocturnal urban heat island intensity (UHII) was developed, using six predictors, and concluded that the RF model is superior to the regression-based model for predicting UHII [30]. In the city of Guangzhou [31] eight different air temperature prediction models were compared using the network of existing weather stations. The best results for hourly air temperature data over a month were obtained using regression kriging (RK) and multiple linear regression (MLR) methods.

Despite these methodological advances, several gaps remain. First, relatively few studies have combined ML techniques with geostatistical modeling in medium-sized cities, where limited monitoring networks often constrain predictive performance. Second, most RF–RK applications have been conducted in large, relatively flat metropolitan areas, leaving open questions about the effectiveness of this hybrid framework in cities with complex topography. Elevation gradients, slope, and valley morphology can substantially alter airflow and thermal stratification, introducing spatial complexity that remains understudied in UHI modeling. Finally, there is limited work assessing the added value of hybrid models over traditional regression in such contexts, particularly regarding their implications for urban climate adaptation strategies.

The present study addresses these gaps by developing and testing an integrated RF–RK framework for UHI modeling in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, a medium-sized city characterized by diverse land surface properties and significant elevation variability. The study focuses on the nocturnal period, when atmospheric stability enhances the influence of surface characteristics on air temperature, offering a robust snapshot of the peak UHI intensity rather than a full diurnal cycle. Specifically, the objectives are (i) to evaluate the relative contribution of urban environmental and localization parameters in explaining nocturnal UHI patterns; (ii) to compare the performance of RF–RK relative to MLR in terms of predictive accuracy; and (iii) to discuss the implications of the results for urban planning and climate adaptation in topographically complex urban environments. The study fulfills its aims by delivering two key contributions: demonstrating the methodological efficacy of hybrid Machine Learning–geostatistical models in fine-scale urban climate analysis, and contextually clarifying the influence of terrain-driven processes on UHI patterns in medium-sized cities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

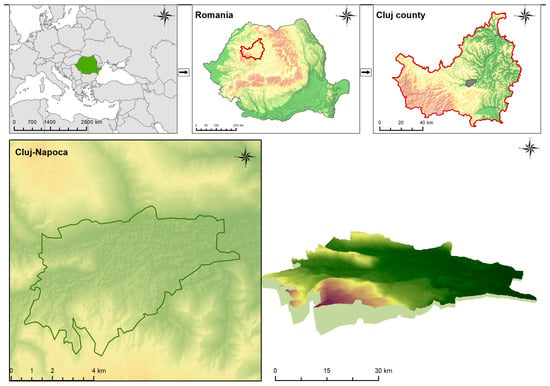

The city of Cluj-Napoca is located in the Transylvania region, in northwestern Romania. The city is primarily placed on the terraces of the Someș Valley, emerging from the mountainous area. It is enclosed between the head of the “cuesta” and a hill that rises to about 900 m, extending towards the valley in an east–west direction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The geographical position of Cluj-Napoca, Romania. All subsequent maps represent temperature distributions within the same administrative boundary of Cluj-Napoca shown here.

The climate is temperate with moderate continental influences (Dfb climate type according to Koeppen). This results in distinct seasonal variations, with cold winters and warm summers. The local air dynamics are characterized by mountain breezes and the wind channeling phenomenon. The local air dynamics play a crucial role in shaping the urban climate. Mountain breezes, which occur due to the temperature differences between the mountain slopes and the valley, help in cooling the area during the summer nights. Additionally, the wind channeling phenomenon, where winds are funneled through narrow valleys or between buildings, influences the city’s microclimate, contributing to variations in temperature and air flow patterns across different urban zones.

Cluj-Napoca is one of the largest cities in Romania, with a population of around 320,000 inhabitants. The city features a mix of residential, commercial, and industrial zones. Cluj-Napoca is experiencing rapid urban growth, with a significant increase in construction and infrastructure development. The city has parks and green areas, but their distribution is uneven.

The choice of Cluj-Napoca as a study area is based on several crucial factors. First, the city is experiencing rapid urban growth and significant urbanization, making this region a relevant site for studying the Urban Heat Island (UHI). Second, the unique topography, the diversity of economic activities, and urban characteristics such as residential, industrial, and commercial zones offer a unique opportunity to analyze thermal variations in various urban contexts. Finally, the availability of MICCRO [32] network data and topographical surveys facilitate an in-depth analysis of the influence of geographic and climatic parameters on the formation of the UHI in Cluj-Napoca.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Design of the MICCRO Network

- Phase I: Theoretical Foundation and LCZ Mapping (2007–2015)

The design of the automatic observation network for the Urban Heat Island (UHI) was based on the concept of local climate zones (LCZs) [33]. LCZs represent areas with uniform surface cover, structure, materials, and human activity, extending horizontally from hundreds of meters to several kilometers. Their delineation provides two major advantages in UHI research: (i) objective characterization of urban–rural thermal contrasts, and (ii) comparability of results across international studies.

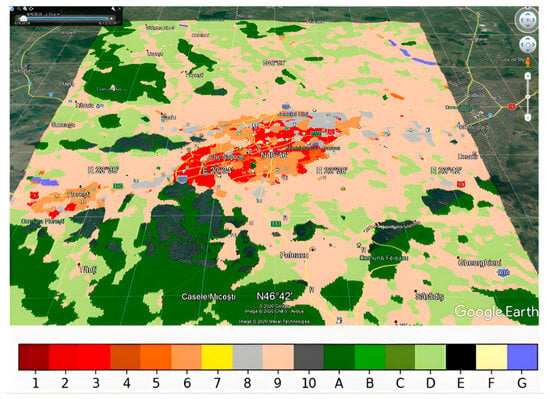

Bechtel emphasized that progress in urban climate science is often limited by the lack of high-resolution information describing the form and function of cities. As part of the World Urban Database and Access Portal Tools (WUDAPT), a global initiative was launched to provide standardized methods and data for mapping LCZs [34]. Using this methodology, LCZs were identified in Cluj-Napoca (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

LCZs in Cluj-Napoca—LCZ 2 (Compact Mid-Rise Buildings): In Cluj, this corresponds to mid-rise residential buildings from the communist period; LCZ 3 (Compact Low-Rise Buildings): In Cluj, this corresponds to the city center; LCZ 5 (Open Mid-Rise Buildings): In Cluj, this corresponds to garden city-type neighborhoods; LCZ 6 (Open Low-Rise Buildings): In Cluj, this corresponds to neighborhoods with urban-type houses; LCZ 8 (Large Low-Rise Buildings): In Cluj, this corresponds to either supermarkets with parking lots or the abandoned industrial area of the city; LCZ 9 (Dispersed Buildings): In Cluj, this corresponds to neighborhoods with rural-type houses or isolated farms; A—Dense forest; B—Scattered trees; C—Bush, scrub; D—Low plants; E—Empty land; F—Bare soil or sand; G—Water.

- Phase II: Field Campaigns and Critical Point Selection (2015–2017)

Seasonal field campaigns were conducted in winter, autumn, and summer under anticyclonic conditions, with observations carried out during the nocturnal stability period (23:00–01:00). The observations covered all LCZs resulting in a large number of measurement points (84 locations). Manual measurements were corrected for time differences to ensure comparability.

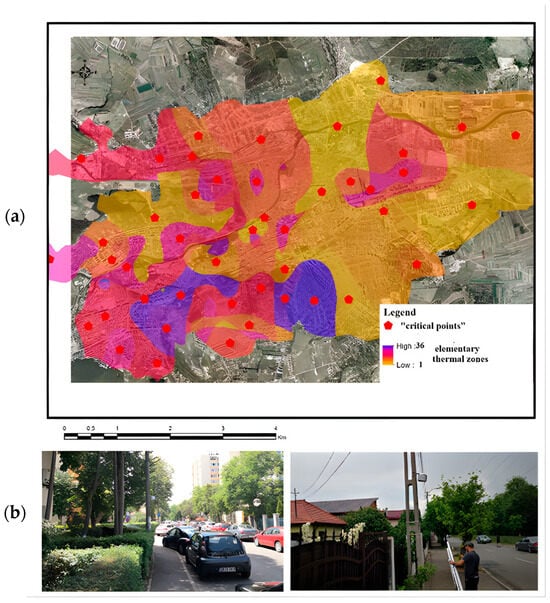

In order to reduce the number of measurement points, without losing the spatial characteristics of thermal variability, seasonal UHI maps were reclassified into three quantile-based classes to normalize variation intervals. Using ArcGIS 10.8 “combine” tools, elementary thermal zones were delineated, defined as areas with similar thermal behavior. Polygons smaller than 0.1 km2 were excluded to avoid fragmentation. The centroids of the elementary thermal zones were designated as critical points [35] forming the basis for optimal sensor placement. Using this objective method, the number of observation points was reduced to 40 locations.

- Phase III: Automatic Network Implementation (2019–2023)

Based on the critical points, a permanent monitoring network was established between 2019 and 2023. A total of 40 HOBO U23 Pro V2 Temp/RH sensors were installed across 179.5 km2 (Figure 3a). Sensors were mounted on utility poles at 3 m above ground level and protected by Onset M-RSA solar radiation shields (Figure 3b). This height was chosen to minimize the direct radiative influence of nearby surfaces and to maintain consistency with international urban-climate monitoring standards, while still capturing the thermal characteristics of the urban canopy layer. Such placement is also a common practice in urban meteorological monitoring, as it reduces the risk of vandalism or accidental interference with the instruments. Sensors were installed at a standardized height of 3 m above ground level and protected using Onset M-RSA radiation shields, ensuring adequate ventilation and minimizing radiative heating effects during all seasons, including winter conditions with snow cover or icing. The HOBO U23 Pro v2 temperature sensors used in the MICCRO network have a manufacturer-specified accuracy of ±0.21 °C and are designed for long-term environmental monitoring with low sensor drift; detailed technical specifications regarding accuracy, precision, and stability are publicly available from the manufacturer. Although the MICCRO network was initially composed of 40 sensors, four stations were excluded from the final analysis due to practical constraints: one sensor experienced a technical malfunction and could not be read, while three sensors were physically lost during the long-term deployment period. The remaining 36 sensors provided continuous and consistent records for the analyzed period. Potential local site effects related to nearby surfaces (e.g., buildings, vegetation, pavement) were minimized through careful site selection following standardized urban climate monitoring guidelines. In addition, data quality was further ensured through statistical screening, including outlier detection and spatial consistency analysis, which helped identify and exclude anomalous readings unrelated to actual microclimatic conditions. This design ensured representative coverage across LCZs while maintaining standardized measurement conditions.

Figure 3.

MICCRO network: (a) the centroids of the elementary thermal zones; (b) examples of installation of the sensors mounted on electrical poles at a height of 3 m.

2.2.2. Temperature Data

The temperature dataset used in this study was derived from the permanent MICCRO observation network operating between 2020 and 2023. To ensure consistency and comparability, we focused on the month of August, which is the most stable summer month in the temperate continental climate of Cluj-Napoca. Moreover, according to Oke [2] nocturnal stability conditions maximize the influence of the active surface on the urban canopy. For this reason, the analysis was restricted to the average air temperature measured at 01:00 AM local time, corresponding to the midpoint of the nocturnal stability period when the UHI signal reaches its maximum intensity. Averaging across a three-year period further reduced micro-variability and allowed for a clearer representation of the nocturnal UHI spatial regime.

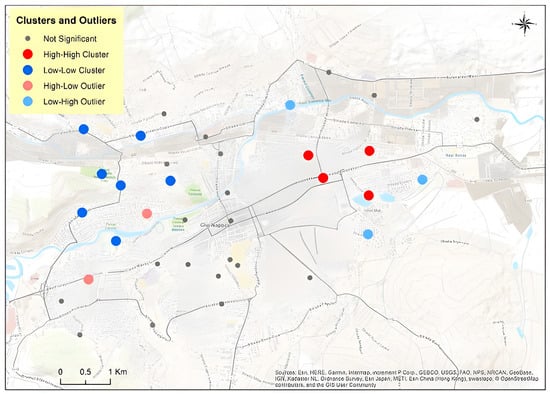

A series of quality control procedures were applied to the raw dataset. First, outlier values exceeding two standard deviations from the mean were removed in order to reduce the impact of measurement errors and increase data reliability. Subsequently, the dataset was validated through spatial analysis in ArcMap, using the Cluster and Outlier tool based on the Local Moran’s I statistic [36]. This procedure compared the temperature of each point with those of its neighbors and classified them into four categories: High–High clusters (hot points surrounded by hot points), Low–Low clusters (cool points surrounded by cool points), High–Low outliers (hot points surrounded by cooler neighbors), and Low–High outliers (cool points surrounded by warmer neighbors). Points not falling into any of these categories were labeled as not significant.

For the spatial conceptualization of relationships, the inverse distance method was used, which assumes, in accordance with Tobler’s first law of geography, that closer entities exert a stronger influence. The relatively small study area allowed the tool to calculate Euclidean distances automatically, ensuring that each point had at least one neighbor. To strengthen the robustness of statistical inference, 999 permutations were applied, resulting in a minimum pseudo p-value of 0.001.

Through this combined approach, the final dataset (36 sensors) was confirmed to be both statistically reliable and spatially consistent, providing a solid basis for the subsequent regression analyses. Although the present analysis focuses on a single nocturnal hour (01:00 AM) and one month (August), this period was deliberately selected to capture the strongest and most stable nocturnal UHI signal. As noted by [2] Oke (1982), August nights under anticyclonic conditions maximize surface–canopy coupling, providing a consistent basis for comparison across sites. Seasonal and diurnal extensions of this work are planned for future monitoring phases. Despite the limited number of sensors (36 stations across 179.5 km2), their spatial allocation followed a stratified design based on Local Climate Zones (LCZs) and elementary thermal zones, ensuring adequate representation of both surface heterogeneity and elevation gradients.

2.2.3. Predictor Variables

The independent variables used in this study were grouped into two categories: (i) location-related variables and (ii) urban environment variables.

- Location-related predictors included altitude, X and Y coordinates, distance from the city center, and distances from the north–south and east–west axes. Altitude was extracted from the EU-DEM dataset at a spatial resolution of 30 m. This digital elevation model was generated by combining SRTM and ASTER GDEM data and provides consistent coverage across Europe.

- Urban environment predictors consisted of building density, tree density, NDVI, and building height, all reflecting different aspects of urban form and vegetation.

- -

- Building density was obtained from the Copernicus Imperviousness Density raster (10 m resolution), which quantifies the proportion of impervious surfaces per pixel, ranging from 0% (completely permeable) to 100% (completely impervious).

- -

- Tree density was derived from the Copernicus Tree Cover Density dataset (10 m resolution), which provides the proportional crown coverage per pixel, ranging from 0% (no tree cover) to 100% (full crown coverage).

- -

- Building height data were retrieved from the Urban Atlas Building Height dataset (10 m resolution), which provides information on average building heights for 870 European cities.

- -

- NDVI was calculated for the vegetation period (May–August 2018) using Sentinel-2 Level-2A imagery accessed via Google Earth Engine (GEE). Only images with less than 10% cloud cover were selected. NDVI values were computed using GEE’s built-in normalized difference function applied to bands B4 (RED) and B8 (NIR). Although NDVI data (Sentinel-2 Level-2A, 2018) precede the temperature observations (2020–2023), regional analyses of vegetation cover indicate high spatial stability in canopy distribution. Nevertheless, uncertainty related to NDVI temporal mismatch is acknowledged and discussed as a limitation. Thus, the 2018 dataset provides a reliable proxy for the spatial variability of surface greenness during the study period.

All predictor layers were spatially aligned to the same coordinate system and resolution to enable comparability and integration into the regression analyses. The resulting images were aggregated and resampled in ArcGIS to a common 30 m resolution, ensuring consistency with the coarser spatial datasets. This multi-source, multi-resolution approach allowed the analysis to capture both biophysical (elevation, vegetation) and anthropogenic (building density, imperviousness, height) drivers of nocturnal air temperature.

2.3. Regression Methods

This study employs the regression kriging method, a geostatistical approach that combines regression techniques with spatial interpolation [37]. The regression kriging model accounts for the spatial structure of the data while incorporating regression relationships to estimate thermal variations. The deterministic part of regression kriging is based on the use of two types of regression: multiple linear regression (MLR) [38] and Random Forest, a machine learning algorithm [39].

Multiple linear regression is a statistical method that models the relationship between a dependent variable and multiple independent variables by fitting a linear equation to the observed data. On the other hand, Random Forest is a robust machine learning technique that creates a multitude of decision trees during training and outputs the mode of the classes for classification or mean prediction for regression, enhancing model accuracy and reducing overfitting. The Random Forest regression model was optimized using a grid-search approach combined with 10-fold cross-validation. The tested hyperparameter ranges included the number of trees (n_estimators = 200–1000), maximum tree depth (max_depth = 5–30), and the number of predictors considered at each split (mtry = √p to p/3). Feature importance was computed using the mean decrease in impurity metric, averaged across all trees. Model performance was evaluated using an 80/20 train–test split, repeated 30 times to reduce sampling bias. We acknowledge that repeated random splits can produce optimistic estimates when spatial autocorrelation is present. The following metrics were reported on the independent test set: coefficient of determination (R2), mean squared error (MSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE). This ensured that the reported metrics reflect predictive rather than training accuracy.

Residuals from both MLR and RF were modeled geostatistically using regression kriging. Experimental variograms were computed using isotropic binning with a lag distance of 300 m. Spherical, exponential, and Gaussian models were tested and compared using leave-one-out cross-validation. The spherical model provided the best compromise between goodness-of-fit and prediction accuracy. Residuals were examined for approximate normality and stationarity. Anisotropy was tested but did not significantly improve variogram fit and was therefore not retained. The final model was selected based on leave-one-out cross-validation, yielding the best fit with a spherical variogram (nugget = 0.05, sill = 0.42, range = 3.5 km).

Regression Kriging follows the formulation:

where Y is the observed temperature at location s, Regression results represent the deterministic component estimated by the regression model, and ε denotes spatially autocorrelated residuals interpolated using ordinary kriging.

Y = Regression results + ε,

In the final stage, the stochastic part is added, which consists of the ordinary kriging of the residuals [40]. This step accounts for the spatial dependence not captured by the regression models, improving the accuracy of surface temperature predictions. This step ensures that the spatial autocorrelation of the residuals is appropriately modeled, further refining the accuracy of the temperature variation estimates.

The complete modeling workflow is summarized in Figure 4. Predictor rasters were harmonized to a 30 m resolution and matched to sensor locations, after which regression models (MLR and RFR) were trained using cross-validation and hyperparameter tuning. Residuals from the best-performing model were interpolated through regression kriging based on variogram fitting. The final hybrid RF–RK surface combined the strengths of machine learning and geostatistics, yielding spatially refined UHI predictions.

Figure 4.

Workflow diagram.

3. Results

3.1. Anselin Local Moran’s I Statistic

The Local Moran’s I analysis (Cluster and Outlier tool in ArcMap) was applied to assess the spatial structure of the nocturnal temperature dataset and to identify potential anomalous values prior to modeling. Out of 36 observation points, 16 were statistically significant at the 95% confidence level and were classified into the four standard categories (Figure 5). Four stations in the eastern sector formed High–High clusters, while seven stations in the western part were classified as Low–Low clusters. Three additional points in the eastern part were identified as Low–High outliers, and two points in the west as High–Low outliers, indicating localized anomalies relative to their neighbors. The remaining 20 stations were not significant, reflecting heterogeneous values without spatial clustering.

Figure 5.

Clusters and Outliers in Cluj-Napoca.

By confirming the presence of these statistically significant clusters and ruling out spurious sensor errors, the Local Moran’s I result provide a robust basis for the subsequent regression and kriging analyses.

3.2. MLR Results

The final Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) model retained four independent variables after the iterative forward selection procedure based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The positional variables included longitude (X), distance to the north–south axis, and distance to the east–west axis, along with one environmental variable, NDVI. Among these, longitude (X) and NDVI exhibited the highest standardized beta coefficients, indicating their stronger relative contributions to the model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Standardized beta coefficients for the predictors retained in the final MLR model.

The spatial distribution of predicted air temperatures generated by the MLR model (Figure 6a) reflects the retained variables, with longitude emerging as the most influential factor. A clear contrast is visible between the eastern and western parts of the city.

Figure 6.

MLR results: (a) The spatial distribution of air temperature values predicted by the Multiple Linear Regression (MLR); (b) Ordinary Kriging of Residuals.

However, the model tends to underestimate temperatures in the central–eastern hotspot identified by the Anselin Moran’s I analysis. This underestimation is clearly highlighted by the kriging of residuals (Figure 6b), where positive maxima are concentrated in the same area. Conversely, the cold spot located in the northwestern part of the city is correctly reproduced, with predicted values approximately 3 °C lower than those in the central districts.

3.3. RFR Results

The Random Forest regression model produced high predictive performance, as evaluated by the coefficient of determination (R2), mean squared error (MSE), and root mean squared error (RMSE). The relative importance of predictors, derived from the trained model, is shown in Table 2. Longitude (X) had the highest importance score (0.219), followed by distances to the north–south axis, to the city center, and altitude (0.111–0.147). NDVI and distance to the east–west axis showed intermediate importance (0.096–0.105). Building density, latitude (Y), building height, and tree density had comparatively lower contributions (0.009–0.074).

Table 2.

Feature importance scores of predictors in the Random Forest regression model.

The RFR model reproduced both the central–eastern hotspot and the northwestern cold spot identified previously (Figure 7a). Residual analysis (Figure 7b) indicated localized overestimation in the central districts, though the magnitude and spatial extent of these residuals were smaller compared to those of the MLR model.

Figure 7.

RFR results: (a) The spatial distribution of air temperature values predicted by the Random Forest Regression (RFR); (b) Ordinary Kriging of Residuals.

3.4. RK Results

Regression Kriging (RK) was applied to integrate the deterministic predictions from MLR and RFR with the spatial autocorrelation of residuals. This procedure generated continuous prediction maps for nocturnal air temperature across the study area (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Kriging regression results: (a) MLR; (b) RFR.

Performance metrics are summarized in Table 3. Compared to MLR, the RFR model achieved higher predictive accuracy, with an R2 of 0.844 and lower error values (MSE = 0.058; RMSE = 0.241). The MLR model reached an R2 of 0.653, with higher error values (MSE = 0.129; RMSE = 0.359).

Table 3.

Performance metrics of Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Random Forest Regression (RFR) models.

The integration of regression predictions with kriging of residuals (Figure 8) improved the spatial detail of the results, reducing localized underestimations observed in the regression-only outputs. Both MLR-RK and RFR-RK produced coherent spatial fields of nocturnal temperature distribution, with RFR-RK showing the smallest residuals and the best agreement with the observed network values.

The integration of regression predictions with kriging of residuals (Figure 8) improved the spatial detail of the results, reducing localized underestimations observed in the regression-only outputs. Both MLR-RK and RFR-RK produced coherent spatial fields of nocturnal temperature distribution, with RFR-RK showing the smallest residuals and the best agreement with the observed network values. In addition to the central–eastern hotspot, the results also revealed a second hotspot located in the southern districts of the city, where predicted temperatures were approximately 2 °C higher than in surrounding areas at lower elevations. Also, compared with the base regression models, the integration of Regression Kriging reduced the RMSE by approximately 5.4% for RF and 7.6% for MLR, while improving R2 by 0.03–0.05, confirming a consistent gain in predictive accuracy.

Overall, the results highlight clear differences in the predictive performance of MLR, RFR, and RK, as well as distinct spatial patterns of nocturnal air temperature across Cluj-Napoca. These aspects are further examined in the Discussion Section, where their implications and underlying mechanisms are addressed.

4. Discussion

The non-linear approach was particularly effective in capturing the complex interactions between topography, land cover, and urban form, as reflected in the high explanatory power of altitude, imperviousness, and building density. These findings align with recent studies in other European and Asian cities that highlight the importance of combining machine learning with geostatistical techniques to account for both non-linear relationships and spatial autocorrelation [41].

A notable observation concerns the contrasting role of NDVI across models. While NDVI was a strong predictor in the linear framework of MLR, its relative importance declined sharply in RF. This suggests that the vegetation signal, which correlates linearly with cooling effects, may be subsumed in RF by more complex combinations of variables such as altitude and impervious fraction. Similar findings were reported by Han et al. [42], who observed reduced vegetation cover importance in non-linear models when topographic predictors were included. This highlights the necessity of interpreting predictor contributions within the context of model architecture rather than assuming universal.

The spatial distribution of hotspots and cold spots identified in Cluj-Napoca further confirms the strong interaction between urban morphology and local topography. Hotspots were concentrated in dense built-up districts located in valley bottoms, whereas cold spots appeared predominantly in the western part of the city. Importantly, this west–east contrast cannot be attributed to land cover alone. It reflects the influence of local airflow dynamics along the Someș Valley, where mountain breezes descending at night enhance ventilation and cooling in the western districts, while simultaneously displacing the urban heat plume eastward. In addition to this pattern, a secondary hotspot was detected in the southern districts situated at higher elevations. This feature can be linked to nocturnal thermal inversions associated with valley breezes, where descending cool air accumulates in lower areas, while relatively warmer air remains over the elevated neighborhoods. Together, these dynamics illustrate how local-scale air dynamics, superimposed on urban morphology, shape intra-urban thermal contrasts. Although direct measurements of wind or atmospheric stability were not available, the observed west–east thermal gradient is consistent with previous studies [33] documenting valley-channeled nocturnal ventilation in cities with similar topographic settings, thereby supporting the conclusion that the UHI shifts downwind. An important contribution of this study is the identification of the dual structure of the nocturnal UHI in Cluj-Napoca, expressed both horizontally and vertically. Horizontally, the results show a clear west–east contrast shaped by valley-channeled breezes that cool the western districts and displace the heat plume toward the east. Vertically, the detection of a secondary hotspot in the elevated southern neighborhoods reflects the role of nocturnal thermal inversions, where cool air descends into the valley while relatively warmer air persists on surrounding slopes. This combined horizontal–vertical perspective offers a novel understanding of UHI dynamics in medium-sized, topographically diverse cities, expanding the largely two-dimensional view that dominates studies from flat metropolitan areas.

From an applied perspective, these results have implications for urban planning and climate adaptation. The identification of persistent nocturnal hotspots in compact residential areas can guide targeted mitigation measures such as increasing vegetative cover, enhancing ventilation corridors, and reducing impervious surfaces. Conversely, recognizing the cooling effect of valley-channeled breezes underscores the importance of preserving airflow pathways and avoiding construction that could block natural ventilation along the Someș Valley.

5. Limitations and Future Work

This study also has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis focused on a single nocturnal hour (01:00 AM) during August, chosen because stable atmospheric conditions maximize the influence of the active surface on the urban canopy layer [2]. While this provides a robust snapshot of peak UHI intensity, it does not capture diurnal or seasonal variability. Second, the sensor network consisted of 40 stations across 179 km2, which, while comparable to other medium-sized city studies, still imposes limits on spatial resolution. Third, although Random Forest and regression kriging proved effective, both methods have known drawbacks: RF may underestimate extreme values, while kriging assumes stationarity that may not hold in the presence of strong spatial trends. While spatial cross-validation would provide a more conservative estimate of predictive performance, the limited number of monitoring stations (n = 36) prevents robust spatial blocking or leave-one-LCZ-out validation. Performance metrics are therefore interpreted cautiously, with emphasis on spatial pattern consistency rather than absolute accuracy.

To mitigate some of these constraints, measurements were aggregated over a three-year period, which reduced micro-scale variability and yielded a clearer representation of the stable UHI regime. Nevertheless, future research should extend the temporal scope to multiple seasons and synoptic conditions, as well as explore additional machine learning such us Support Vector Regression or Gradient Boosted Trees—geostatistical hybrids to further test model generalizability.

Although the present study identifies a combined horizontal–vertical structure of the nocturnal UHI based on spatial modeling results, direct measurements of vertical thermal profiles and airflow dynamics were not available. Future research will address this limitation through dedicated vertical profiling campaigns using an instrumented DJI Mavic 3 drone equipped with a calibrated air-temperature sensor and data logger, enabling direct assessment of nocturnal thermal stratification and inversion layers.

6. Conclusions

This study applied a hybrid modeling approach that combined Random Forest regression with Regression Kriging to assess the nocturnal Urban Heat Island (UHI) in Cluj-Napoca, based on three years of temperature observations. By combining non-linear modeling with spatial interpolation, the approach captured both the complexity of surface–atmosphere interactions and the spatial autocorrelation inherent in urban temperature fields, achieving substantially higher predictive accuracy than traditional Multiple Linear Regression.

The results revealed two key spatial patterns. First, a clear west–east contrast was identified, with the western districts systematically cooler and the eastern districts warmer. Second, a secondary hotspot was detected in the elevated southern neighborhoods, where nocturnal temperatures were approximately 2 °C higher than in the valley areas. These findings demonstrate that the UHI in Cluj-Napoca exhibits both a horizontal (west–east) and a vertical (altitudinal) structure.

The originality of this study lies in showing how local airflow dynamics shape UHI intensity in a medium-sized, topographically diverse city. Valley-channeled breezes along the Someș River enhance ventilation in the west and displace warm air toward the east, while nocturnal inversions explain the persistence of warmer conditions on the elevated slopes. This three-dimensional characterization underscores that UHI processes cannot be fully understood within a purely planar framework.

From a practical perspective, these insights provide useful guidance for urban planning and climate adaptation. Preserving ventilation corridors, maintaining vegetated surfaces, and targeting mitigation in persistent hotspots can help reduce UHI intensity and its associated health and energy impacts.

Author Contributions

I.-H.H.—Conceived and designed the study, conducted experiments, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; M.A.—collected data, writing—review and editing; K.T.-I.—collected data, data visualization, writing—review and editing; C.-D.U.—contributed to the methodology, data visualization, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Internal grants for supporting the strategic infrastructure of UBB 2019: Implementation of an Urban Heat Island measurement network in Cluj-Napoca.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the large volume and specialized format but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to all the students who participated in the field observations. Your dedication and hard work have been invaluable to this research. We are especially grateful to the volunteers from the Applied Climatology Study Group. Your expertise, enthusiasm, and commitment have significantly contributed to the success of this project. Without your tireless efforts, this study would not have been possible. Thank you all for your exceptional contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Howard, L. The Climate of London: Deduced from Meteorological Observations, Made at Different Places in the Neighbourhood of the Metropolis; W. Phillips: London, UK, 1818; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Oke, T.R. The Energetic Basis of the Urban Heat Island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.M.; Dennis, L.Y.C.; Liu, C. A Review on the Generation, Determination and Mitigation of Urban Heat Island. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamouris, M. Cooling the Cities—A Review of Reflective and Green Roof Mitigation Technologies to Fight Heat Island and Improve Comfort in Urban Environments. Sol. Energy 2014, 103, 682–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Analyzing the Heat Island Magnitude and Characteristics in One Hundred Asian and Australian Cities and Regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 512–513, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouladi, N.; Møller, A.B.; Tabatabai, S.; Greve, M.H. Mapping Soil Organic Matter Contents at Field Level with Cubist, Random Forest and Kriging. Geoderma 2019, 342, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, P.; Kumar, M.; Panwar, N. Digital Soil Mapping of Sand Content in Arid Western India through Geostatistical Approaches. Geoderma Reg. 2017, 9, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçay, T.; Alaboz, P.; Dengiz, O.; Başkan, O. Application of Regression Kriging and Machine Learning Methods to Estimate Soil Moisture Constants in a Semi-Arid Terrestrial Area. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, W.; Saurette, D.D.; Easher, T.H.; Li, H.; Shi, Z.; Adamchuk, V.I.; Biswas, A. Three-Dimensional Digital Soil Mapping of Multiple Soil Properties at a Field-Scale Using Regression Kriging. Geoderma 2020, 366, 114253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, F.; Lu, W.; Fang, Z.; Li, Z.; Pan, J. Digital Mapping of Soil Organic Carbon Based on Machine Learning and Regression Kriging. Sensors 2022, 22, 8997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Ren, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Assessment of Multi-Wavelength SAR and Multispectral Instrument Data for Forest Aboveground Biomass Mapping Using Random Forest Kriging. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 447, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan Erten, G.; Yavuz, M.; Deutsch, C.V. Combination of Machine Learning and Kriging for Spatial Estimation of Geological Attributes. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.; Berger, H.; Henriksen, H.J.; Sonnenborg, T.O. Modelling of the Shallow Water Table at High Spatial Resolution Using Random Forests. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 4603–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdouri, A.; Murayama, Y. A Comparative Study of Land Price Estimation and Mapping Using Regression Kriging and Machine Learning Algorithms across Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 794–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Farías, F.; García-Valdecasas Ojeda, M.; Donaire-Montaño, D.; Rosa-Cánovas, J.J.; Castro-Díez, Y.; Esteban-Parra, M.J.; Gámiz-Fortis, S.R. Assessment of physical schemes for WRF Model in convection-permitting mode over southern Iberian Peninsula. Atmos. Atmos. Res. 2024, 299, 107175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martilli, J.; Clappier, A.; Rotach, M.W. An urban boundary layer scheme for a mesoscale model. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2002, 104, 261–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca, F.; Martilli, A.; Tewari, M.; Chen, F. A Study of the Urban Boundary Layer Using Different Urban Parameterizations and High-Resolution Urban Canopy Parameters with WRF. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2011, 50, 1107–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, M.; Resler, J.; Geletič, J.; Krč, P.; Maronga, B.; Sühring, M.; Kurppa, M.; Kanani-Sühring, F.; Fuka, V.; Eben, K.; et al. Sensitivity analysis of the PALM model system 6.0 in the urban environment. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 4443–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Caballero Arciénega, N.A.; Alabdallah, T.; Vogt, U. Application of the urban climate model PALM-4U to investigate the effects of the diesel traffic ban on air quality in Stuttgart. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.H.; Schlünzen, K.H.; Grawe, D.; Boettcher, M.; Gierisch, A.M.U.; Fock, B.H. The microscale obstacle-resolving meteorological model MITRAS v2.0: Model theory. Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 3427–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoka, S.; Tsikaloudaki, A.; Theodosiou, T. Analyzing the ENVI-met microclimate model’s performance and assessing cool materials and urban vegetation applications—A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, P.; Varentsov, M.; Malinina, E. Modeling of thermal comfort conditions inside the urban boundary layer during Moscow’s 2010 summer heat wave (case-study). Urban Clim. 2014, 10, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessami, M.; Gachon, P.; Ouarda, T.B.; St-Hilaire, A. Automated regression-based statistical downscaling tool. Environ. Model. Softw. 2007, 23, 813–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilby, R.; Wigley, T. Downscaling general circulation model output: A review of methods and limitations. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 1997, 21, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benestad, R.E. Empirical-statistical downscaling in climate modeling. Eos 2004, 85, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baño-Medina, J.; Manzanas, R.; Gutiérrez, J.M. On the suitability of deep convolutional neural networks for continental-wide downscaling of climate change projections. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 57, 2941–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukawa, G.Y.; Krecl, P.; Targino, A.C. Fine-scale modeling of the urban heat island: A comparison of multiple linear regression and random forest approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yim, S.H.; Heo, Y. Interpreting complex relationships between urban and meteorological factors and street-level urban heat islands: Application of random forest and SHAP method. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 126, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Deng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, C.; Gao, Z. A High-Resolution Monitoring Approach of Canopy Urban Heat Island Using Random Forest Model and Multi-Platform Observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardes, T.; Schoetter, R.; Hidalgo, J.; Long, N.; Marquès, E.; Masson, V. Statistical Prediction of the Nocturnal Urban Heat Island Intensity Based on Urban Morphology and Geographical Factors—An Investigation Based on Numerical Model Results for a Large Ensemble of French Cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Ge, J. Machine Learning-Assisted Mapping of City-Scale Air Temperature: Using Sparse Meteorological Data for Urban Climate Modeling and Adaptation. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holobâcă, I.H.; Alexe, M.; Temerdek-Ivan, K. Les premiers résultats de la surveillance de l’îlot de chaleur à Cluj-Napoca à l’aide du réseau automatique MICCRO (Monitorizarea Insulei de Căldura în Cluj—România). In Proceedings of the 35eme Colloque Annuel de l’AIC, Toulouse, France, 6–9 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R. Local Climate Zones for Urban Temperature Studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 93, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, B.; Alexander, P.; Böhner, J.; Ching, J.; Conrad, O.; Feddema, J.; Mills, G.; See, L.; Stewart, I. Mapping Local Climate Zones for a Worldwide Database of the Form and Function of Cities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2015, 4, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holobâcă, I.H. Le monitoring de l’ilot de chaleur urbain de Cluj-Napoca, Roumanie. In Proceedings of the 30eme Colloque Annuel de l’AIC, Sfax, Tunisia, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin, L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Webster, R. A Tutorial Guide to Geostatistics: Computing and Modelling Variograms and Kriging. Catena 2014, 113, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Rossiter, D.G. About Regression-Kriging: From Equations to Case Studies. Comput. Geosci. 2007, 33, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, N.R. Applied Regression Analysis, 1st ed.; New York Academy of Sciences Series; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Newark, NJ, USA, 1998; ISBN 9780471170822. [Google Scholar]

- De Raedt, L.; Flach, P. (Eds.) Machine Learning: ECML 2001: 12th European Conference on Machine Learning, Freiburg, Germany, 5–7 September 2001 Proceedings; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2167, ISBN 9783540425366. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Oleson, K.; Bou-Zeid, E.; Krayenhoff, E.S.; Bray, A.; Zhu, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, C.; Oppenheimer, M. Global Multi-Model Projections of Local Urban Climates. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Du, C.; Xie, Y.; Xian, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, B.; Chen, Y. A 3D Perspective for Understanding the Mechanisms of Urban Heat Island and Urban Morphology Using Multi-Modal Geospatial Data and Interpretable Machine Learning. Build. Environ. 2025, 282, 113184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.