Abstract

Against the backdrop of advancing rural revitalization and urban–rural integration, the deep integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism in megacity suburbs has become a critical pathway toward high-quality regional development. This study takes Huangpi District of Wuhan as an example to elucidate the mechanisms of such integration and propose corresponding optimization strategies. Using panel data from 2020–2023, we applied the entropy-weighted TOPSIS, coupling coordination degree, and grey relational analysis models, combined with POI data and kernel density estimation, to systematically evaluate the spatial patterns and integration level of agricultural, cultural, and tourism resources. The main findings include: (1) the coupling coordination degree of agriculture–culture–tourism integration increased from 0.49 to 0.75, progressing from near dysfunction to moderate coordination, with a robust trend; (2) cultural system indicators—particularly the scale of cultural enterprises—exert the strongest driving effect on integration, while agricultural productivity and tourism infrastructure provide essential support; (3) a spatial mismatch between resource-rich northern areas and service-concentrated southern zones constrains overall synergy efficiency. These findings offer a reference for similar regions, though limitations related to static POI data and methodological assumptions should be noted.

1. Introduction

Globally, suburban and rural areas face multiple challenges in achieving sustainable development, including environmental pressures, economic disparities, weak social governance, and homogeneous industrial structures. The integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism has emerged as a significant trend for promoting rural revitalization and regional sustainable development. However, the overall level of integration remains low with notable regional disparities, necessitating diversified approaches, collaborative governance, and innovation-driven strategies [1,2,3]. Sustainable urban–rural development is confronted with multifaceted challenges. Environmental and resource pressures arise from urban expansion [4,5,6,7]; while economic and social inequalities persist in suburban and rural regions [8,9]. Consequently, the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism has become a crucial developmental pathway. By consolidating agricultural resources, cultural heritage, and tourism assets, it enhances agricultural efficiency, preserves cultural traditions, and boosts tourism development. This approach reduces reliance on subsidies, mitigates risks associated with policy withdrawal, and fosters diversified and sustainable rural economies [10,11]. Through industrial synergy, it drives economic growth, increases farmers’ incomes, narrows regional gaps, and serves as a vital mechanism for advancing common prosperity and rural revitalization [3,12,13].

China has achieved remarkable success in rural poverty alleviation and environmental improvement through large-scale fiscal investments. However, the risks of “subsidy dependence” and “rebound effects upon policy termination” have become increasingly prominent. Consequently, the core value of integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism lies in fostering an endogenous and self-sustaining rural industrial system. This approach effectively reduces long-term reliance on external subsidies and serves as a critical mechanism for achieving sustainable rural revitalization. The Communist Party of China has explicitly called for shifting the focus of work toward rural revitalization, emphasizing the development of new business formats such as rural tourism and leisure agriculture to promote high-quality growth of the rural economy [14]. Subsequently, the State Council further highlighted in the Notice on Issuing the “14th Five-Year Plan for Tourism Development” that it is essential to strengthen the integration of cultural and tourism sectors, foster complementary advantages, and build synergistic momentum for development. This provides higher-level guidance and institutional support for the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism [15]. However, alongside rapid economic development and accelerated urbanization, rural areas face both opportunities and challenges. For instance, urban expansion and industrial transformation often lead to population decline, land degradation, and environmental deterioration in megacity suburbs and rural areas, with plains and semi-mountainous regions typically experiencing more pronounced impacts [16]. In this context, the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism stimulates consumer demand, attracts capital inflows, and optimizes industrial structures, thereby fostering deep convergence among agriculture, culture, and tourism. This process contributes to the formation of a diversified and endogenously growing industrial system [17,18]. This integration not only enhances farmers’ self-development capacity by generating employment, encouraging entrepreneurship, and increasing incomes—thus strengthening the rural “self-hematopoietic” function and reducing reliance on singular subsidy mechanisms [19,20], but also facilitates the transformation of ecological and cultural values into economic benefits. It supports green development and cultural preservation, contributing to sustainable rural revitalization [2,21]. Furthermore, the integration process attracts talent, technology, and capital back to rural areas, promoting innovation-driven development and enhancing industrial resilience [22], Overall, it provides an endogenous solution to address the multifaceted challenges in rural development.

In recent years, China has introduced multiple macro-level policies, such as the “Rural Revitalization Strategic Plan,” the “14th Five-Year Plan” for Tourism Development, and the “Opinions on Accelerating the Modernization of Agriculture and Rural Areas” [14,15,23], to vigorously support the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism. These policies aim to enhance rural self-development capabilities through industrial synergy and achieve sustainable revitalization [20,21,24]. Firstly, most existing research focuses on macro-level statistics and policy interpretation, with insufficient analysis of the dynamic mechanisms and typical cases at micro-levels such as counties and villages. This makes it difficult to fully reveal the internal heterogeneity within regions [25,26]. Secondly, academic discussions have predominantly centered on the binary integration of agriculture and tourism (agri-tourism) or culture and tourism (cultural tourism) [27,28]. Although some studies have begun to explore the ternary integration of agriculture–culture–tourism, systematic, holistic, and quantitative analyses of their coupling mechanisms remain relatively weak [27,29]. Furthermore, research focusing specifically on the suburbs of megacities as a distinct spatial unit is particularly scarce. As a frontier for the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism, these areas are characterized by urban–rural juxtaposition, diverse resources, and strong demand. However, current studies are mostly concentrated on traditional rural or ethnic regions, lacking systematic and quantitative analysis of the dynamic processes, spatial evolution, and driving mechanisms of integration in these suburban zones [30,31]. Concurrently, while some research addresses macro-level regional disparities, there is still a lack of detailed depiction and in-depth analysis of spatial pattern evolution, land-use transformation, and stakeholder interactions at micro-scales, such as towns, villages, and communities [32].

Huangpi District has leveraged its advantages as an urban suburb, its ecological strengths, and the cultural appeal of Mulan to develop a deep integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism, achieving notable progress in comprehensively advancing rural revitalization. Consequently, it has been successfully included in the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs’ 2023 list for creating national rural revitalization demonstration counties [33]. Among these factors, Mulan culture serves as the core cultural IP driving this integrated development. The spirit of loyalty, filial piety, courage, and dedication embedded in the Mulan legend, along with its local sentimental value, has been deeply integrated into local festivals, folk activities, rural landscapes, and cultural-creative products. This has fostered a cultural identity as the “Hometown of Mulan” and enhanced its tourism appeal. However, the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District still faces multiple challenges. Some projects suffer from insufficient exploration of cultural depth, homogenization of tourism products, and a weak connection between agricultural and cultural-tourism industries, which limits the benefits and sustainable development capacity of industrial integration. These issues urgently require in-depth research and resolution. Notably, Huangpi District is not an ordinary suburban area. It constitutes a “highly concentrated” sample and an ideal paradigm for observing and understanding how the suburbs of a megacity achieve deep integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism. As the “North Gateway” of Wuhan City, Huangpi possesses exceptional locational advantages and transport accessibility [34]. Simultaneously, Wuhan, a megacity with a permanent population exceeding 13 million [35]. Therefore, Huangpi District forms a ‘highly concentrated laboratory’ and an ‘ideal type’ for studying the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism in megacity suburbs. Its experience holds significant demonstrative and analytical value for understanding the development logic of similar regions.

Taking Huangpi District of Wuhan City as a typical case study, this research focuses on its locational characteristics and developmental realities as a suburb of a megacity, systematically exploring the internal mechanisms and practical pathways for the deep integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism. It aims to address the following core questions: (1) Identify and analyze the spatial distribution and agglomeration patterns of the core agricultural, cultural, and tourism elements in Huangpi District. (2) Assess the development levels of the three subsystems and measure their coupling coordination degree from 2020 to 2023. (3) Identify the key factors influencing the coupling coordination degree of the agriculture–culture–tourism integration system within this context. It innovatively integrates multi-source POI data with a combination of quantitative models to precisely quantify the process of integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism and dissect its underlying mechanisms. The specific steps are as follows: firstly, based on high-granularity POI data, the spatial agglomeration characteristics of agricultural, cultural, and tourism elements are identified and analyzed; secondly, the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method is employed to assess the development level of each subsystem from 2020 to 2023, and the coupling coordination degree model is used to quantify the synergistic state between the systems; finally, grey relational analysis is applied to identify the key driving factors influencing the coupling coordination degree of the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism. This combination of methods not only transcends traditional qualitative descriptions but also provides a replicable and scalable methodological toolkit for revealing the synergistic logic and mechanisms of complex systems. Thereby, it offers theoretical reference and practical paradigms for promoting rural revitalization and regional sustainable development in similar areas.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Research Trajectory and Theoretical Perspectives

As early as the 1960s, international academic research began with a focus on rural tourism, later expanding to encompass forms such as agritourism and cultural tourism. Through extensive fieldwork and case study analysis, a relatively mature theoretical framework was established. However, a literature review reveals that research focusing systematically on the ternary integration of “agriculture–culture–tourism” remains insufficient. Existing discussions are mostly dispersed within the two categories of “agri-tourism integration” and “cultural-tourism integration” [36,37,38,39]. In recent years, scholars both domestically and internationally have gradually turned their attention to the complex system interwoven by agriculture, culture, and tourism. Some studies have attempted to construct evaluation index systems for this ternary integration and have employed quantitative methods such as the coupling coordination model and spatial econometrics to conduct empirical analyses of the integration level and influencing factors at the county or regional scale [12,40]. Internationally, research also exists that examines the synergy between culture, tourism, and agriculture and its role in sustainable revitalization [24]. These findings provide theoretical and methodological references for understanding the internal mechanisms and spatial heterogeneity of ternary integration.

Nonetheless, research that systematically investigates the dynamic processes, spatial characteristics, and driving factors of the ternary integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism in the specific geographical unit of “megacity suburbs” using quantitative methods like the coupling coordination model remains extremely scarce. The existing literature predominantly concentrates on traditional rural areas, counties, or ethnic regions, or is limited to the binary coupling of agriculture–tourism or culture–tourism. There is a lack of holistic, dynamic, and spatially explicit quantitative analyses of ternary integration for megacity suburbs—areas characterized by urban–rural juxtaposition, unique resource endowments, and diverse market demands [41,42]. Particularly in revealing their integration evolution pathways, spatial differentiation patterns, and multifaceted driving mechanisms, a systematic theoretical and empirical framework has yet to be established.

With the implementation of China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy and the deepening of the holistic tourism concept, related research has progressed significantly by building upon international foundations. Since the proposal of the “Rural Revitalization” strategy in 2017, the ternary integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism has been explicitly identified as an important pathway for promoting rural economic transformation and high-quality development [1,18]. Driven by policy, local governments have actively introduced supporting measures to facilitate deep industrial integration [20]. Meanwhile, the academic community has systematically assessed the level of integration, its spatial patterns, and its impacts on economic growth, green productivity, and sustainable development by constructing evaluation index systems and employing methods such as the coupling coordination degree model, entropy method, and PVAR model [11,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Overall, while substantial progress has been made in current research regarding integration models, quantitative evaluation, and mechanistic analysis, systematic, dynamic, and spatially explicit quantitative studies focusing on special regions such as megacity suburbs still require further strengthening.

In the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism, culture is not a mere appendage to nature or a static backdrop for tourism; rather, it serves as a core element that shapes the uniqueness of rural tourism, deepens visitor experiences, and constructs place identity. Research indicates that cultural resources such as heritage, local knowledge, traditional crafts, and lifestyles can significantly enrich tourism content and deepen experiential engagement, offering visitors opportunities for learning, participation, and self-enrichment, thereby becoming a key driver of tourist attraction [49,50,51]. Furthermore, these cultural experiences, through emotional resonance and spiritual connection, profoundly influence tourists’ “place identity,” enhancing their sense of belonging, loyalty, and revisit intention [52,53,54]. The triple function of cultural spaces—demonstration, experience, and emotional engagement—precisely strengthens the emotional bond between visitors and the countryside [55,56]. On this basis, culture-centered branding can effectively highlight the distinctive features of rural areas, enhancing their brand recognition and market competitiveness [21,51,57]. Therefore, only by positioning culture at the forefront, through in-depth exploration, preservation, and innovative utilization of local cultural resources, can the high-quality development and branding of rural tourism be sustainably driven.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations and Analytical Framework

The theme was not incorporated into mainstream economic discourse until Rosenberg (1963) published his work on “Technological Change and Industrial Growth” [58]. Although he did not explicitly use the term “convergence,” his work established the foundational framework of “technology–market–organization” tripartite interaction for subsequent research. Over the past few decades, the theory of industrial convergence has been widely applied and expanded within the fields of rural development and tourism studies, continuously driving theoretical innovation and diversification of practical models. This theory posits that the boundaries between different industries tend to blur. Through the interactive permeation of elements such as resources, technology, and markets, new business forms and models can emerge. Consequently, it has become a key theoretical foundation for promoting the upgrading of rural industries and the high-quality development of tourism [59,60,61]. In the rural context, industrial convergence provides theoretical support for the synergistic development of agriculture, processing, and service industries, aiding in the realization of rural revitalization and common prosperity goals [62,63,64]. Specifically, by promoting the integration of primary, secondary, and tertiary industries, it not only enhances the added value of agricultural products and facilitates farmers’ income growth and rural economic diversification [63,65,66], but also, with the infusion of digital technology and financial deepening, injects new momentum into convergence. This drives the industrial chain towards intelligence and informatization, improving the efficiency of resource allocation [67,68]. Furthermore, the collaboration among multiple stakeholders, including farmers, enterprises, and cooperatives, helps promote brand building, green development, and social innovation, achieving sustainable development [64,69]. In the tourism sector, industrial convergence manifests as deep interaction with various industries such as culture, consumer goods, and the low-altitude economy. This has spurred the emergence of new formats like cultural and creative tourism, wellness tourism, and the experience economy, significantly enhancing the diversity and added value of tourism products [59,61,70]. Overall, the theory of industrial convergence, by interconnecting elements from different sectors, provides ongoing theoretical guidance and practical pathways for innovation and development in both rural and tourism domains.

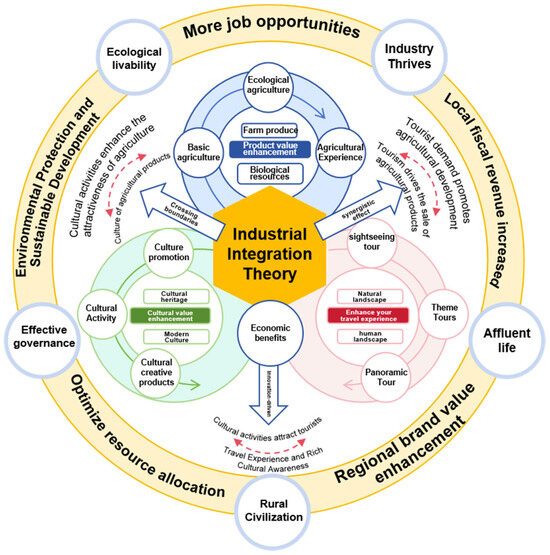

The integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism represents a significant application of industrial convergence theory in the field of rural revitalization. Within this framework, the agricultural industry centers on agricultural products and ecological resources, aiming to enhance product value. The cultural industry relies on traditional and modern cultural resources, with the goal of elevating cultural value. The tourism industry is based on natural and human landscapes, dedicated to optimizing the tourism experience. Industrial convergence theory, through cross-boundary collaboration and innovation-driven approaches, facilitates the recombination of elements from these three industries, the upgrading of value chains, and community-based collaborative governance. This systematically transforms originally discrete agricultural resources, cultural assets, and tourist flows into a driving force for rural revitalization. Against the backdrop of the Rural Revitalization Strategy, the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism can promote the optimal allocation of resources, increase employment, enhance regional brand value, and support ecological conservation and sustainable development. Consequently, it advances the achievement of comprehensive objectives such as industrial prosperity, ecological livability, cultural and ethical progress, effective governance, and prosperity in life. Its essence is a systematic project that uses integrated innovation as the engine, centers on the sustainable development of people and place, and ultimately aims for the comprehensive revitalization of the rural economy, ecology, society, and culture (Figure 1). In this study, industrial convergence theory provides the theoretical basis for explaining the interactive relationships among the agricultural, cultural, and tourism subsystems. To advance the translation from theory to empirical analysis, the research further constructs a coupling coordination degree model to assess the state of synergy between the systems, employs the TOPSIS method to measure the development level of each system, and utilizes grey relational analysis to identify key driving factors. This systematically reveals the internal mechanisms and synergistic pathways of the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism.

Figure 1.

Mechanism Diagram for Deep Integration of Agriculture, Culture, and Tourism Based on Industrial Convergence Theory. (Solid arrows indicate stage-wise changes in industrial factors driven by industrial convergence. Hollow arrows denote the propelling effect of industrial convergence between two industries. Double-headed dashed arrows signify potential interactions between two industries within the theoretical framework of industrial convergence).

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area

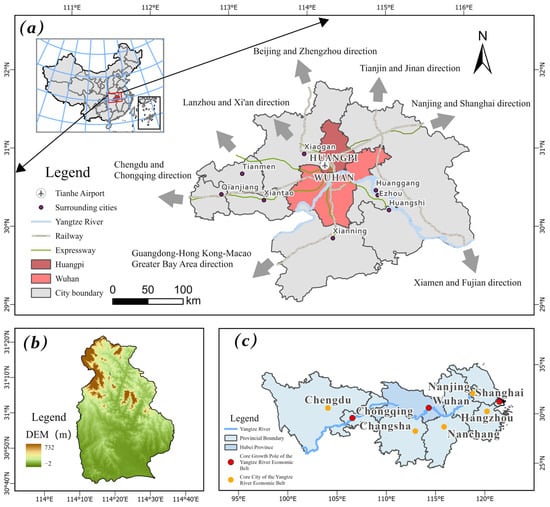

Located in the core area on the north bank of the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, Huangpi District spans geographical coordinates from 114°09′ to 114°37′ E and 30°40′ to 31°22′ N. With a total area of 2261 km2, it is the largest administrative district in Wuhan by land area [71]. The district is equipped with three national-level transportation hubs—Tianhe Airport, Wuhan New Port, and a railway freight marshalling yard—positioning it as a critical node for the flow of economic factors, industrial collaboration, and cultural exchange between Wuhan and surrounding cities (Figure 2a). Its elevation ranges from −2 m to 732 m, characterized by higher terrain in the north and lower in the south (Figure 2b). As a key radiating zone within the Yangtze River Mid-Reach Urban Agglomeration, Huangpi holds a distinctive locational advantage in regional coordinated development (Figure 2c). Its unique geographical position, well-developed transportation system, and favorable economic environment provide robust conditions for the deep integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism, while also enabling it to play an increasingly active role in regional economic development.

Figure 2.

Overview Map of the Study Area in Huangpi District. (a) Geographic and Transportation Location Map, (b) Digital Elevation Model (DEM), (c) Economic Location Map. Note: Administrative boundaries are based on the standard map with approval number GS(2020)4632, and the DEM data is sourced from NASA.

3.2. Research Framework and Data Sources

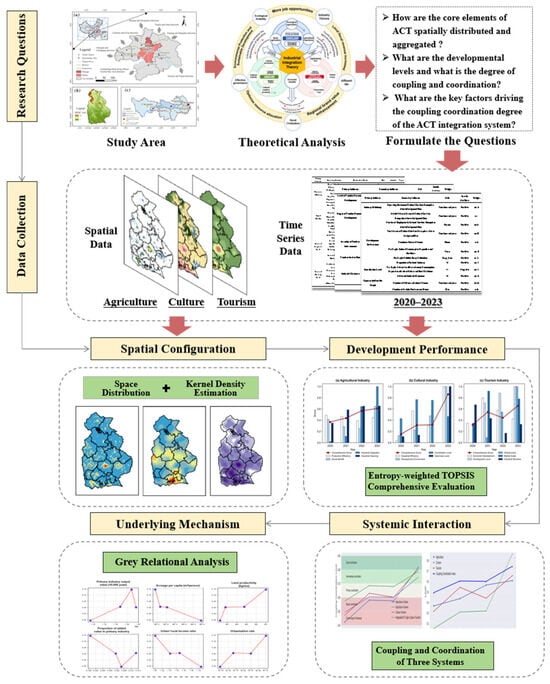

The research framework is illustrated in Figure 3. This study collects Point of Interest (POI) data related to agriculture, culture, and tourism, and analyzes their spatial agglomeration characteristics through kernel density analysis. The development levels of the subsystems are measured using the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method. The coupling coordination degree model is employed to quantify the interactive stress and synergistic state between the systems. Finally, Grey Relational Analysis is used to identify the dominant factors influencing the coupling coordination degree. This progressive analytical framework—“Spatial Configuration–Development Performance–Systemic Interaction–Underlying Mechanism”—enables a systematic diagnosis of the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and intrinsic driving mechanisms of agriculture–culture–tourism integration.

Figure 3.

The Research Framework.

Given the diversity of tourism resources across Huangpi’s townships and the strategic focus on all-for-one tourism (where the entire district is positioned as an integrated tourism destination), different townships assume distinct roles in tourism development. Consequently, existing statistical data are typically aggregated at the district level, with a notable absence of township-level granularity, making townships unsuitable as primary units of analysis for this study. Under these circumstances, the time series data primarily originate from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Rural Statistical Yearbook, Huangpi District Statistical Yearbook, and the Huangpi District National Economic and Social Development Statistical Bulletin. Due to the small scale of the study area and data availability constraints, data for Huangpi District were only obtained for the period 2020 to 2023. Although the time span of the sample is relatively short, the absence of missing values ensures the continuity of the analysis process and the internal integrity of the data, providing a relatively reliable basis for the exploratory identification of key driving factors.

The POI data used in this paper were collected from AMap (a web map service provider in China), with an extraction date of 31 August 2025. Based on the category and semantic information of the POI data, the original dataset was classified into three subsystems: agriculture, culture, and tourism. Keywords for each subsystem were selected and categorized as follows: The agriculture subsystem mainly includes agricultural production and experience sites, such as agricultural markets, farming, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery units, and fruit-picking gardens. The culture subsystem covers various cultural and public facilities, including museums, scenic spots, parks and squares, memorial halls, cultural and educational venues, temples, and libraries. The tourism subsystem focuses on tourism services and hospitality facilities, such as A-level tourist attractions, public toilets, accommodation, and dining establishments. This classification framework provides a data foundation for the subsequent spatial analysis and integration assessment of these industries.

Land use data were sourced from the CLCD provided by Wuhan University [72].

Regarding research tools, the drawing of the base map for the study area, the screening of POI data, and the kernel density analysis were all completed in ArcGIS Pro 3.1.6. The measurement of subsystem development levels (entropy-weighted TOPSIS), the analysis of the coupling coordination degree between systems, and the Grey Relational Analysis were all implemented in Python 3.9. The visualization of various analytical results was accomplished using Origin.

3.3. Research Methods and Data Processing

3.3.1. Spatial Distribution Analysis

This study employs POI data to analyze the spatial distribution of agricultural, cultural, and tourism resources in Huangpi District. POI data, which captures the category and geographic coordinates of facilities, is combined with kernel density estimation to visually delineate the spatial agglomeration patterns of these industrial resources. This approach offers a practical methodological framework for characterizing the spatial layout of regional industries related to agriculture, culture, and tourism.

Data Exclusion Criteria: POIs located outside the study area were excluded. The remaining coordinates underwent rectification and deduplication, with duplicate entries within a 10 m radius removed. POIs with overly generic names (e.g., “Company,” “Shop,” “Building”) that could not be linked to a specific function based on other information were also filtered out. Within the cultural industry category, scenic spots were further refined to focus on those associated with historical and cultural heritage, deliberately excluding natural landscape POIs to allow for a more precise analysis of cultural-industry spatial characteristics. Following this cleaning process, 252 valid samples were retained for agriculture, 192 for culture, and 666 for tourism.

3.3.2. Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS Method

The Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS method is a multi-attribute decision-making approach that integrates the entropy weight method with the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) [73]. It is commonly employed in scenarios requiring comprehensive evaluation and ranking of multiple alternatives, particularly when the determination of attribute weights is challenging through subjective means [74]. Its flexibility and broad applicability have led to its widespread use across various contexts in social science research [75], with particular effectiveness in county-level economic evaluation studies [76].

The main computational steps for determining weights using the Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS method are as follows [76]:

Construct the decision matrix:

Given decision alternatives and evaluation criteria, construct the decision matrix X:

Normalized Decision Matrix ( for the maximum value of the same indicator):

Calculate information entropy:

Define indicator weights:

Calculate the weight matrix:

3.3.3. Coupling Coordination Degree Model

A coupling coordination analysis was conducted based on data pertaining to the high-quality development levels of agriculture, culture, and tourism. The coupling coordination degree model serves as an effective tool for assessing and analyzing the interaction and coordinated development among multiple systems. When examining the integrated development of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District, this model can reveal synergistic effects among these systems. This study adopts the modified coupling coordination degree model proposed by Wang Shujia et al. The advantage of this model lies in its ability to disperse the coupling degree (C) as much as possible across the [0, 1] interval, thereby avoiding the common issue of C values clustering within a narrow high-value range. This enhances the discriminative power of C-values and demonstrates higher validity in social science research [77].

When investigating the synergistic effects between agriculture and culture, agriculture and tourism, or culture and tourism, the specific formulas are as follows:

In the formula: C represents the coupling degree; , denote the two systems under analysis. D represents the coupling coordination degree. T is the evaluation index for both systems. Since they are equally important in the coupling coordination process, , are each set to 0.5.

When studying the synergistic effects among the three major systems of agriculture, culture, and tourism, the following formula is used:

represents the coupling degree, where , and denote the agricultural, cultural, and tourism systems, respectively. represents the coupling coordination degree. is the evaluation index for these three systems. Since all three are equally important in the coupling coordination process, the weights of , and are all set to 1/3. This equal-weight assignment is a common practice in studies of multi-system coupling coordination where no prior evidence suggests a significant disparity in the subsystems’ contributions [78,79].

Drawing on relevant studies [80], the coupling coordination degree is categorized into ten distinct levels: Extreme Dysfunction (0.000–0.099), Severe Dysfunction (0.100–0.199), Moderate Dysfunction (0.200–0.299), Mild Dysfunction (0.300–0.399), On The Verge Of Dysfunction (0.400–0.499), Barely Coordinated (0.500–0.599), Primarily Coordinated (0.600–0.699), Moderately Coordinated (0.700–0.799), Well Coordinated (0.800–0.899), and Quality Coordination (0.900–1.000).

3.3.4. Grey Relational Analysis

To quantitatively identify the key factors influencing the coupling coordination degree of agriculture, culture, and tourism integration in Huangpi District and measure their respective associations, this study employs the Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) method. GRA is a multi-factor statistical technique grounded in grey system theory. Its core principle is to measure the correlation between factors by comparing the geometric similarity between sequences of various factors and a reference sequence. This method is particularly suitable for analyzing complex systems characterized by small sample sizes and incomplete information, as it imposes no strict requirements on data distribution.

Specifically, the implementation of GRA follows these steps:

Define the Reference Sequence: The coupling coordination degree of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District is designated as the reference sequence (parent sequence), X0 = {x0(k)∣k = 1, 2,…, n} representing the primary characteristic of system development.

Define the Comparative Sequences: Indicators of influencing factors, screened from dimensions such as policy and institutional frameworks, resource endowment and regional characteristics, economic foundation and market demand, social and cultural factors, infrastructure and public services, technological innovation and digital empowerment, and environmental carrying capacity and ecological protection, are selected as the comparative sequences (child sequences). Denote the comparative sequences as Xi = {xi(k)∣k = 1, 2,…, n; i = 1, 2,…, m}.

Dimensionalization of Data: Due to potential variations in the units and magnitude of different indicators, dimensionalization techniques such as mean normalization or initialization must be applied to raw data. This process eliminates the influence of units, ensuring the objectivity of results.

Common methods include initialization processing:

Mean-value processing:

represents the dimensionless data.

Calculate the difference sequence by computing the absolute difference between corresponding elements in the reference sequence and each comparison sequence:

Determine the maximum difference Δmax = maxi maxk Δi(k) and the minimum difference Δmin = mini mink Δi(k).

Calculate correlation coefficients. Based on the differences between the reference sequence and the comparison sequences at each time point, calculate the correlation coefficient for each comparison sequence relative to the reference sequence. The correlation coefficient reflects the degree of association between the comparison sequences and the reference sequence at specific points.

ρ ∈ [0, 1] is the resolution coefficient, typically set to 0.5.

Calculate Relational Degree: The correlation coefficients for each comparative sequence are aggregated through weighted averaging to obtain the Grey Relational Degree. A higher value indicates a stronger correlation between the comparative sequence and the reference sequence, signifying a greater influence of that factor on the coupling coordination degree.

Rank Relational Degrees: The influencing factors are ranked according to their calculated Grey Relational Degrees. This ranking allows for the identification of key factors that exert a significant influence on the coupling coordination degree of the agriculture, culture, and tourism integration.

3.4. Indicator System Construction

3.4.1. Construction of the Agricultural High-Quality Development Indicator System

When constructing an evaluation indicator system for high-quality agricultural development at the county level, the selection of indicators must balance scientific rigor with practical operability. Existing literature consistently emphasizes that county-level evaluations should focus on data availability and key policy implementation nodes specific to this administrative scale, selecting proxy variables that directly reflect the core characteristics of agricultural transformation at the county level [78,81,82,83,84]. The consensus is that indicators must closely align with county-level statistical frameworks. For instance, conventional official statistics such as the gross output value of farming, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery and the per capita disposable income of rural residents are used to represent foundational development and livelihood benefits. Simultaneously, elements reflecting local characteristics and policy guidance, such as the number of new agricultural business entities and investment in the agricultural and sideline food processing industry, should be incorporated to measure the practical progress of industrial integration. Regarding the resource and environment dimension, county-level data (e.g., fertilizer application per unit sown area) are typically more accessible and can directly inform the regulation of specific agricultural production practices. Therefore, the construction of this indicator system draws on the general framework for evaluation at this scale, aiming to systematically depict the quality dimensions and transition process of agricultural development in Huangpi District through a set of measurable and comparable indicators. The specific evaluation indicator system for high-quality agricultural development constructed is presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Evaluation Indicator System for Agricultural High-Quality Development.

3.4.2. Construction of the Cultural High-Quality Development Indicator System

Based on existing research foundations and theoretical analysis [41,85,86,87,88], and while considering data availability and representativeness, this paper constructs an evaluation indicator system for the high-quality development of the cultural industry, encompassing four dimensions. The Industry Efficiency dimension measures the direct output capacity, capital effectiveness, employment scale, and overall input of the industry through four core economic indicators of cultural service enterprises above the designated size: operating revenue, added value of assets, number of employees, and total assets. This reflects its economic performance and intensification level. The Development Environment dimension examines the foundational facilities, market demand, and macroeconomic standing. The number of cultural venues and per capita public library collections characterize the level of infrastructure and resource provision; per capita cultural consumption expenditure of residents reflects the intensity of core market demand; and the proportion of the cultural industry indicates its relative importance within the regional economic structure. The Coordination Level dimension focuses on the balance and sophistication of development. The per capita cultural and entertainment consumption expenditure ratio of urban and rural residents is used to assess the fairness of cultural consumption between urban and rural areas; industrial structure advancement points to the qualitative evolution of the industry’s internal upgrade towards higher value-added formats. The Open to the Outside World dimension emphasizes cultural influence and market expansion. The number of visitors to cultural venues reflects the attractiveness and reach of facility resources; the number of artistic performance events (especially those for external exchange) indicates the vibrancy of cultural products “going global” and the degree of market participation. The specific evaluation indicator system for cultural industry high-quality development is constructed as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation Indicator System for High-Quality Development of Cultural Industries.

3.4.3. Construction of the Tourism High-Quality Development Indicator System

Based on insights from county-level tourism evaluation studies and considering data availability [17,89,90,91,92,93], this paper constructs a five-dimension indicator system to assess the high-quality development level of the tourism industry, aiming to comprehensively evaluate the integrated development status of tourism in Huangpi District. The framework encompasses the following core dimensions: The Level of Tourism Economic Development is represented by total revenue and income specifically from rural leisure tourism, directly reflecting the industry’s economic contribution and the vitality of its characteristic formats. The Degree of Tourism Resources Development is measured by the number of high-grade scenic spots and demonstration sites, quantifying the endowment and quality of core attractions. Notably, A-grade scenic spots are rated according to the national standard “Rating of quality levels of tourist attractions” (GB/T 17775-2024) [94], which comprehensively assesses service quality, environmental quality, landscape quality, and visitor feedback. A higher grade generally indicates stronger resource value, management service levels, and market recognition. In the specific calculation for this study, the weight for 5A scenic spots was set to zero, as their number in Huangpi District remained constant throughout the observation period. The Maturity of Tourism Infrastructure evaluates the hardware support capacity of reception services by selecting key elements such as accommodation facilities and tourist restrooms. Tourism Market Size is gauged by the total number of tourists and the promotion of Affordable Tourism Cards, measuring the visitor base and market penetration depth. Lastly, Industrial Structure is examined through both the proportion of the tertiary industry and the intensity of fiscal support, revealing the tourism sector’s interconnected status and level of prioritization within the regional economy and public policy. These interrelated indicators collectively form a systematic assessment tool (Table 3).

Table 3.

Evaluation Indicator System for Tourism Industry High-Quality Development in Huangpi District.

4. Results

4.1. Foundations and Current Status of Agricultural-Cultural-Tourism Integration

4.1.1. Foundations and Current Status of Agricultural Industry Development

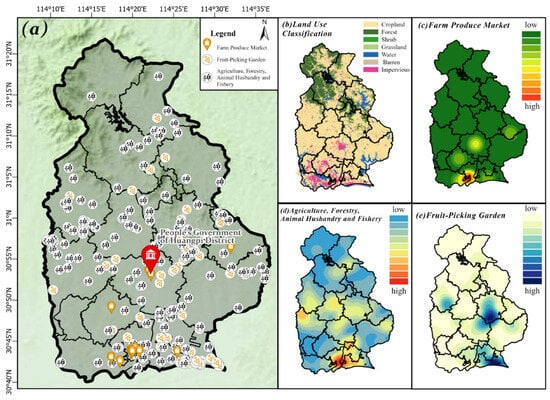

Spatial aggregation characteristics were calculated for both the total agricultural POIs and each sub-category in Huangpi District. The spatial distribution reveals a significant pattern of “clustering in the central-southern areas and dispersion in the northern regions” (Figure 4a). Agricultural resources are predominantly concentrated in the central-southern part of Huangpi District, which aligns closely with the distribution of cultivated land in the area. The central-southern region features relatively flat terrain and proximity to rivers, constituting the primary cultivated land zone of Huangpi District (Figure 4b). High kernel density values are primarily clustered in subdistricts such as Wangjiahe and Shekou, forming a continuously distributed agricultural belt. In contrast, northern subdistricts like Caidian and Yaoji exhibit lower kernel density values, presenting a scattered distribution pattern (Figure 4c–e).

Figure 4.

Spatial Distribution of Agricultural Resources, Township Boundaries, and Kernel Density Analysis in Huangpi District. (a) Spatial Distribution of Agricultural Resources; (b) Land Use Classification; (c) Kernel Density of Agricultural and Sideline Products Markets; (d) Kernel Density of Agriculture, Forestry, Animal Husbandry, and Fishery Resources; (e) Kernel Density of Picking Garden Resources.

This distribution pattern primarily stems from two key factors: location/transportation conditions and industrial foundations. (1) Location and Transportation Advantages. The central-southern area is situated within the core zone of the Wuhan Metropolitan Circle, adjacent to the main urban center. The density of the transportation network exhibits a decreasing gradient from south to north. Southern areas, such as Shekou Subdistrict, leverage the Hankou North market cluster to function as a core hub for the distribution of agricultural and sideline products. (2) Industrial Foundation and Structure. Serving as the regional “granary” and “vegetable basket,” the central-southern part boasts over 50 years of large-scale planting history. This has fostered the development of a comprehensive industrial chain spanning from breeding to sales, characterized by a high rate of processing conversion. The spatial distribution manifests the following characteristics:

Business Entities: Nearly half of the specialized farmer cooperatives are concentrated in the central Wangjiahe Subdistrict, specializing in large-scale grain cultivation.

Agritourism: Picking gardens exhibit a “dual-core” layout. The southern core capitalizes on proximity to urban centers for leisure picking, while the northern Mulan Mountain area develops an “eco-picking + tourism” model, which displays lower density due to transportation constraints.

Market Distribution: 85% of agricultural and sideline product markets are clustered along the Wuhan Metropolitan Circle Ring Road, forming a spatially efficient “market-logistics-production” synergy.

4.1.2. Development Foundation and Current Status of the Cultural Industry

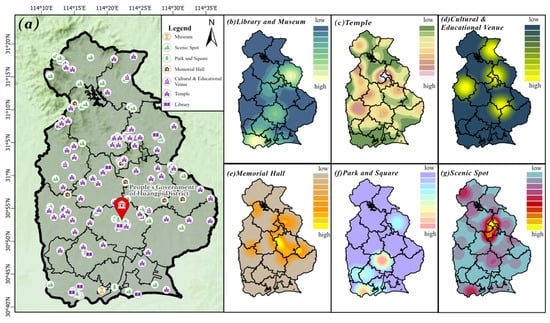

As shown in Figure 5a, Huangpi District possesses a considerable number of cultural landmarks, which are distributed relatively evenly across its various subdistricts. This distribution pattern fully demonstrates the district’s rich cultural resources and profound historical and cultural heritage. Kernel density analysis performed on the cultural industry POI points in Huangpi District reveals that the cultural industry primarily forms three major clustering cores: the Mulan Culture Agglomeration Area in the north, the Ercheng Culture Agglomeration Area in the center, and the Panlong Culture Agglomeration Area in the south. However, a comprehensive comparison of the agglomeration scope and kernel density values indicates that the Mulan Culture Agglomeration Area covers a broader area and exhibits higher kernel density values (Figure 5b–g). The formation of this pattern is closely tied to the cultural foundation of Huangpi District. The district has long been committed to developing its tourism industry around Mulan culture as the central theme. Through sustained investment and development, numerous cultural industries leveraging Mulan culture have gradually emerged in the Mulan Township and Mulan Mountain area. These industries collaborate and develop synergistically, establishing a large-scale and relatively comprehensive cultural industry system.

Figure 5.

Spatial Distribution and Kernel Density Analysis of Cultural Resources in Huangpi District. (a) Spatial Distribution of Cultural Resources; (b) Kernel Density of Libraries and Museums; (c) Kernel Density of Temples and Taoist Temples; (d) Kernel Density of Science, Education and Cultural Resources; (e) Kernel Density of Memorial Halls; (f) Kernel Density of Parks and Squares; (g) Kernel Density of Scenic and Historic Areas.

4.1.3. Development Foundation and Current Status of the Tourism Industry

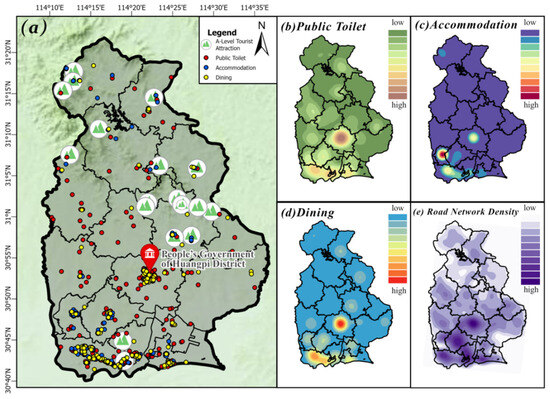

The spatial distribution of tourism resources in Huangpi District exhibits significant regional heterogeneity, which is closely related to its administrative divisions, economic development patterns, and transportation network (Figure 6a). As the administrative center of Huangpi District, Qianchuan Subdistrict’s locational advantages and transportation conditions profoundly influence the development of tourism resources and the layout of service facilities across the district. Tianhe Subdistrict is the most concentrated area for accommodation resources in Huangpi District, primarily attributable to Wuhan Tianhe International Airport, a major transportation hub that generates substantial demand for business and transit passenger lodging (Figure 6b). The distribution of catering resources shows a high degree of consistency with that of accommodation resources (Figure 6c), being primarily concentrated in areas of economic development and high population density. Public toilet facilities are also mainly clustered in highly urbanized and populous areas such as Qianchuan Subdistrict, Panlongcheng Economic Development Zone, and Wuhu Subdistrict (Figure 6d).

Figure 6.

Spatial Distribution and Kernel Density Analysis of Tourism Resources in Huangpi District. (a) Spatial Distribution of Tourism Resources; (b) Kernel Density of Public Toilets; (c) Kernel Density of Accommodation Resources; (d) Kernel Density of Catering Resources; (e) Kernel Density of Transportation Conditions.

This distribution pattern aligns with conventional urban infrastructure layout. However, the number of toilet resources shown in the POI data for subdistricts containing major tourist attractions is relatively low. This is mainly because A-grade tourist attractions typically have dedicated tourist toilets internally. Managed as part of the attraction, these facilities might not be included in general public facility POI statistics. Field investigations confirm that the major scenic spots in Huangpi District are generally equipped with an adequate number of sanitary toilet facilities meeting tourism grade standards, capable of fulfilling visitors’ basic needs within the attractions. Furthermore, the overall road network density in Huangpi District is relatively evenly distributed, providing a solid foundation for regional transportation accessibility (Figure 5e).

The spatial distribution of tourism resources in Huangpi District reveals a distinct pattern of “tourism in the north, economy in the south.” The northern area boasts abundant natural and cultural tourism resources, but its supporting services like accommodation and catering are relatively underdeveloped. This leads to leakage of tourist expenditure and limits the development of the nighttime economy. The southern region, dominated by economic development, has well-established infrastructure but lacks core tourism appeal. Although Huangpi District’s toilet facilities and road network generally meet tourism demands, the spatial mismatch of tourism service elements, particularly the disconnection between core attractions and high-quality living service facilities, constitutes a major challenge for current tourism development. This spatial misalignment adversely affects the continuity and depth of tourist experiences in Huangpi District and also restricts the comprehensive driving effect of tourism on the local economy.

4.2. Evaluation of High-Quality Development Levels in Agriculture, Cultural Industry, and Tourism

4.2.1. Evaluation of the High-Quality Development Level of the Agricultural Industry

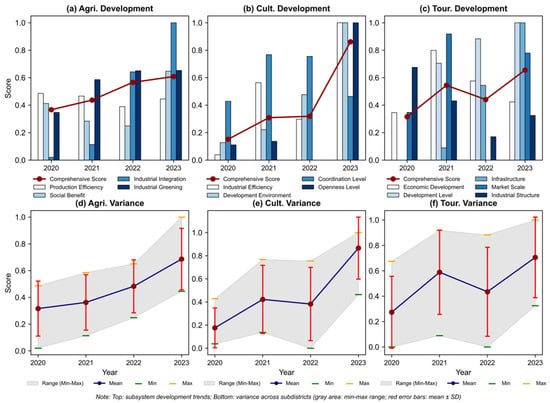

Based on the evaluation results of agricultural industry development level (Figure 7a), the high-quality development level of agriculture in Huangpi District showed a steady upward trend. The comprehensive score increased from 0.367 in 2020 to 0.609 in 2023, with an average annual growth rate of 21.98%. Overall, the high-quality development level of agriculture in Huangpi District is satisfactory, demonstrating a moderate growth rate with substantial potential for further improvement. It is noteworthy that despite the COVID-19 pandemic occurring between 2020 and 2023, the agricultural high-quality development level maintained an upward trend, indicating that the overall level was not significantly impacted by the pandemic. Analysis of scores across individual dimensions reveals different fluctuations during the pandemic period. From 2020 to 2022, production efficiency and social benefits showed declining trends, while both the greening level and industrial integration level registered substantial improvements, particularly industrial integration. Considering the actual context, this phenomenon can be attributed to the strong correlation between production efficiency and social benefits with population mobility and market consumption. Under pandemic restrictions, reduced population movement led to decreased agricultural labor input and constrained production efficiency. Simultaneously, reduced industrial investment during the pandemic contributed to the decline in overall agricultural production efficiency.

Figure 7.

Development Trends and Dimensional Balance of Agriculture, Cultural, and Tourism Industries in Huangpi District (2020–2023). (a) Agricultural Development; (b) Cultural Development; (c) Tourism Development; (d) Dimensional Variance in Agriculture; (e) Dimensional Variance in Culture; (f) Dimensional Variance in Tourism.

4.2.2. Evaluation of the Cultural Industry High-Quality Development Level

The evaluation results of the cultural industry development level in Huangpi District are shown in Figure 7b. The temporal variation in the comprehensive evaluation value indicates that from 2020 to 2022, the high-quality development level of the cultural industry remained at a relatively low stage of 0.3–0.35. Constrained by factors such as the pandemic impact, restricted consumption, and hindered flow of production factors, industrial development was severely impeded. By 2023, the comprehensive evaluation value surged to 0.861, representing an approximately 2.6-fold increase compared to the previous year and approaching the theoretical maximum of 1, indicating a rapid transition of the cultural industry to a high-level stage driven by both the end of the pandemic and a suite of targeted local interventions.

Analysis of the four core dimensions reveals:

- Industrial efficiency exhibited a V-shaped fluctuation, declining to 0.29 in 2021 before recovering to 1 in 2023 alongside market revival and productivity gains that were underpinned by government stabilization measures.

- Development environment demonstrated a J-shaped growth pattern, also reaching 1 in 2023, substantially supported by concrete policy measures. These included municipal-level stimuli such as the distribution of tourism consumption vouchers and travel benefit cards [95], as well as district-level relief efforts. Notably, Huangpi District implemented a loan interest subsidy program for key cultural and tourism enterprises in 2022 [96], a direct financial support measure guided by provincial-level recovery policies [97]. These multi-layered interventions helped sustain business operations during the downturn and primed the market for recovery.

- Coordination level displayed an inverted V-shape; although it slightly decreased to 0.46 in 2023, it overall maintained stable resilience.

- The openness level exhibited the most pronounced volatility, plummeting to 0 in 2022 before rebounding sharply to 1 in 2023, thereby becoming the indicator with the greatest magnitude of change. This dramatic shift is directly attributable to a surge in key underlying metrics: the number of visitors to cultural venues, which had remained between 100,000 and 120,000 from 2020 to 2022, skyrocketed to 1.248 million in 2023. Concurrently, the number of cultural and artistic performances doubled compared to the 2022 level.

In summary, the development of Huangpi’s cultural industry between 2020 and 2023 was closely linked to the progression of the pandemic and the government’s responsive policy suite. Core business formats—such as cultural tourism performances, exhibitions and festivals, and offline entertainment—were constrained during the pandemic due to their heavy reliance on offline consumption. Conversely, in 2023, the optimization of pandemic control policies, the concentrated release of pent-up demand, and the activation of pre-existing policy tools [96] (e.g., continued demand-side stimuli like the “Huangpi Residents Tour Huangpi” program), led to a 64.4% year-on-year increase in visitor numbers and an 83% growth in tourism revenue. This significantly boosted industrial efficiency, the development environment, and the level of openness, collectively driving a leapfrog recovery in the comprehensive development level.

4.2.3. Evaluation of the Tourism Industry High-Quality Development Level

As evidenced by the data (Figure 7c), all tourism development indicators in Huangpi District were severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, where lockdowns and travel restrictions brought the tourism economy to a near standstill. In 2021, the sector experienced a brief recovery following improved pandemic control and the release of pent-up travel demand. However, subsequent pandemic resurgences and global economic volatility led to more conservative tourism consumption, causing the tourism economy to decline again during 2022–2023. It is noteworthy that this decline was mitigated by proactive fiscal support. A key intervention was the district’s execution of a loan interest subsidy program for major tourism enterprises at the end of 2022 [96]. This measure, a direct response to provincial relief guidelines [97], provided critical liquidity to buffer against operational pressures and stabilized the core supply-side actors in the market.

Regarding resource development, Huangpi District achieved steady improvement through the upgrade of existing scenic areas and the development of new attractions. The market scale peaked in 2021 before fluctuating downward. Although the number of inbound visitors recovered in 2023, the per capita spending declined, reflecting a trend of consumption downgrading. This trend can be partially attributed to the nature of the post-pandemic recovery stimuli. Early municipal policies [95] and local benefit programs emphasized accessibility and volume recovery (e.g., through consumption vouchers and resident discounts) over short-term high-value spending. While effective in rapidly expanding the visitor base and restarting market activity, this approach temporarily diluted per capita revenue metrics.

In terms of industrial structure, the proportion of the tertiary industry continued to rise, yet the share of tourism expenditure in the fiscal budget decreased year by year. Overall, the high-quality development of the tourism industry in Huangpi District demonstrated a “fluctuating upward trajectory,” shaped not only by external shocks and market forces but also by deliberate governmental efforts to sustain and catalyze the sector through a mix of supply-side subsidies (interest relief) and demand-side incentives.

4.2.4. Dimensional Variance in Subsystem Development

Based on variance statistics (Figure 7d–f), the development across different dimensions within each of the agriculture, culture, and tourism subsystems in Huangpi District exhibited significant heterogeneity. The tourism subsystem demonstrated the highest level of internal imbalance, while the agricultural subsystem showed a convergent trend in its internal disparities. The cultural subsystem, despite its rapid development, continued to face persistent dimensional imbalances.

The tourism subsystem exhibited the greatest internal dimensional disparity among all subsystems (average CV = 0.7142, average range = 0.7657). Its standard deviation increased from 0.2835 in 2020 to 0.3508 in 2022, indicating a widening gap among its five dimensions: tourism economic development level, resource development degree, infrastructure, market scale, and industrial structure. Although the standard deviation decreased to 0.3175 in 2023, the range remained high at 0.6751, signifying that significant gaps between dimensions persisted. The coefficient of variation (CV) decreased from 1.0361 in 2020 to 0.4499 in 2023, suggesting an improvement in relative dispersion, yet it remained the highest among all subsystems. Therefore, coordinated development across the internal dimensions of the tourism subsystem requires focused attention, particularly in achieving balanced improvement between infrastructure and market scale.

The agricultural subsystem displayed a clear convergent trend in its internal dimensions (CV decreased from 0.6495 to 0.3356). Its standard deviation remained relatively stable over the four years (0.1977–0.2303) and did not expand alongside the growth in the mean value. The significant decline in the coefficient of variation indicates a reduction in the relative gaps among its four dimensions: production efficiency, social benefits, industrial integration level, and industrial greening level. While the highest dimensional score reached 1.0000 in 2023, the range was still 0.5547, suggesting room for further optimization. Consequently, current agricultural policies have effectively promoted balanced development across the subsystem’s internal dimensions, and this experience could serve as a model for promotion.

The cultural subsystem exhibited a dual characteristic of “rapid development coupled with internal dimensional imbalance.” Its mean value surged most dramatically from 0.1760 to 0.8660, an increase of 0.69. The standard deviation peaked at 0.3169 in 2022 and saw a slight decrease thereafter. The coefficient of variation improved significantly from 0.9799 to 0.3096, yet it remained higher than that of the agricultural subsystem. Thus, while maintaining rapid development, greater effort is needed to enhance the lagging dimensions.

4.3. Evaluation of the Deep Integration Development Level of Agriculture, Culture, and Tourism Based on the Coupling Coordination Degree Model

Integrating the spatial distribution analysis from Section 4.1 with the temporal evaluation results from Section 4.2, the development of agriculture–culture–tourism integration in Huangpi District exhibits distinct spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Spatially, a significant mismatch pattern of “tourism in the north, economy in the south” characterizes the distribution of industrial resources. Temporally, while the development trajectories of individual subsystems vary, an overall upward trend is evident. This composite spatiotemporal characteristic provides a multidimensional perspective for understanding the evolution of coupling coordination.

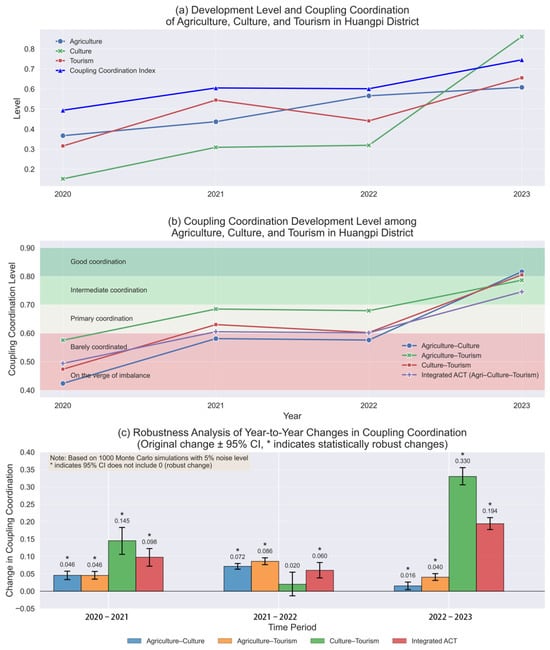

According to the tri-system coupling coordination analysis results (Figure 8a), the integrated development level of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District demonstrates a clear upward trajectory, increasing from 0.49 in 2020 to 0.75 in 2023. The coordination status progressively improved from being on the verge of dysfunction to moderate coordination. Interactions and synergies among the regional systems have gradually strengthened, although significant disparities persist in their individual development levels. It is particularly noteworthy that the current moderate coordination level (0.75) may be structurally constrained by the spatial mismatch identified in Section 4.1.3. The northern area possesses abundant tourism resources but lacks sufficient supporting service facilities, while the southern region is economically developed yet lacks core tourism appeal. This “tourism in the north, economy in the south” spatial mismatch pattern likely impedes synergistic effects among the agricultural, cultural, and tourism systems, thereby limiting further improvement of the overall coupling coordination degree.

Figure 8.

Evaluation of the Deep Integration Development Level and Robustness Analysis of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District (2020–2023). (a) Comparative Changes in Individual Industries’ Development Levels and Integrated Development Level; (b) Comparative Changes in Coupling Coordination Development Levels Between Dual Systems and the Triple System; (c) Robustness of Year-to-Year Changes in Coupling Coordination Under Data Noise Influence.

Specifically, the cultural subsystem exhibited a particularly remarkable increase, rising from 0.15 in 2020 to 0.86 in 2023, with a substantial surge occurring between 2022 and 2023. The coupling coordination index of the agricultural subsystem also showed a continuous upward trend, albeit with a relatively smaller magnitude of increase. In contrast, the performance of the tourism subsystem appeared somewhat volatile, which may be related to the discontinuous tourist experience resulting from spatial mismatch. The insufficiency of accommodation and catering facilities in the northern core tourism area may lead to leakage of tourist expenditure, while the limited tourism appeal of the southern economic zone restricts the scale effects of the tourism industry. This spatial misalignment affects the maximization of synergistic efficiency between the tourism subsystem and the others.

Based on the pairwise coupling coordination analysis results (Figure 8b), the coupling coordination development levels of the three system pairs—agriculture–culture, agriculture–tourism, and culture–tourism—all displayed upward trends in Huangpi District. Among them, the agriculture–tourism system started from a relatively higher baseline but demonstrated slower growth momentum, remaining at a moderate coordination level by 2023. In contrast, both the culture–tourism and culture–agriculture systems exhibited robust growth dynamics, successfully advancing from the verge of dysfunction to good coordination. Notably, although the pairwise coupling coordination levels among subsystems continuously improved, the overall coupling coordination level of the complete agriculture–culture–tourism system remained lower than that of any subsystem pair. This phenomenon likely reflects the compounded impact of spatial mismatch: despite favorable development within each subsystem dimension, the misalignment in regional spatial layout restricts their synergistic efficiency as an integrated system. The isolated development of tourism resources in the north and the functionally singular economic zone in the south may hinder the formation of an effective interactive network among agriculture, culture, and tourism systems in space.

Further analysis reveals that spatial mismatch may affect the coupling coordination degree through the following mechanisms: First, the spatial separation of resources and services limits tourists’ length of stay and consumption depth, reducing opportunities for agriculture–tourism crossover. Second, the regional agglomeration of cultural resources coupled with the spatial dispersion of tourism facilities may lead to the fragmentation of cultural experiences. Third, the southern concentration of agricultural production and the northern orientation of tourism consumption restrict the geographical foundation for agriculture–tourism integration. These spatial constraints collectively contribute to a situation where, despite an upward trend in coordination over time, the integration efficiency in the spatial dimension remains suboptimal in Huangpi District’s agriculture–culture–tourism system, thereby explaining the formation mechanism of the current moderate coordination level.

In summary, the development of agriculture–culture–tourism integration in Huangpi District is characterized by “temporal improvement coupled with spatial constraints.” In the temporal dimension, the coordination levels within and between systems have steadily increased, indicating a positive trend in integrated development. In the spatial dimension, however, the resource mismatch pattern of “tourism in the north, economy in the south” constitutes a structural bottleneck for further enhancement of the coupling coordination degree. This finding suggests that future policies for agriculture–culture–tourism integration should not only focus on the temporal development trajectories of individual industries but also prioritize the optimization of spatial layout. Measures such as strengthening service facility construction in northern tourism areas and enhancing tourism appeal in southern economic zones could mitigate the efficiency loss in coordination caused by spatial mismatch, thereby advancing the integrated development of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District toward a higher level.

To examine the influence of data noise, we conducted a robustness analysis employing Monte Carlo simulation (1000 iterations with 5% Gaussian noise). By calculating the 95% confidence intervals for the year-to-year changes in the coupling coordination degree, we assessed the robustness of these changes under the influence of data noise (a change was considered robust when its 95% confidence interval did not include zero). As illustrated in Figure 8c, the year-to-year changes in the coupling coordination degree of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District exhibited a high degree of robustness. Among the 12 annual changes, 11 (91.7%) were robust at the 5% data noise level, indicating that the observed synergistic development trends represent reliable statistical phenomena rather than random fluctuations. The coupling coordination degrees for agriculture–culture, agriculture–tourism, and the integrated agriculture–culture–tourism system all demonstrated 100% robustness. Particularly, the robust growth in the integrated coupling coordination degree (2022–2023 Δ = 0.1942, 95% CI [0.1772, 0.2118]) suggests a resilient growth momentum for the synergistic development of the three systems. The change in the culture–tourism coupling coordination degree for the 2021–2022 period failed the robustness test (Δ = 0.0202, 95% CI [−0.0132, 0.0547]). This finding implies that although a slight numerical increase in culture–tourism synergy was observed during this period, this change may be relatively sensitive to data noise and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

4.4. Grey Relational Analysis Results of Influencing Factors

To identify the key factors influencing the integrated development of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District, this study employed GRA to examine 38 potential influencing indicators. The calculated relational degree values between each indicator and the agriculture–culture–tourism coupling coordination degree are presented in Table 4, ranging from 0.42 to 0.95.

Table 4.

Relational Degrees between Various Indicators and the Coupling Coordination Degree of agriculture, culture, and tourism in Huangpi District.

Table 4 displays the relational degree values between all 38 influencing indicators and the agriculture–culture–tourism coupling coordination degree. The top three indicators with the highest relational degree are Total Assets of Cultural Services Enterprises Above Designated Size (0.95), Number of Employees in Cultural Services Enterprises Above Designated Size (0.93), and Proportion of the Tertiary Industry (0.92). A total of 13 indicators exhibit high relational degrees between 0.80 and 0.90, including Disposable Income of Rural Households (0.90), Effective Irrigated Area (0.87), Land Productivity (0.87), Number of A-Grade Tourist Restrooms (0.86), Urbanization Rate (0.86), and Operating Revenue of Cultural Industries (0.86). Eight indicators show medium relational degrees between 0.70 and 0.80, such as Proportion of Cultural Industry (0.81), Number of Cultural Venues (0.80), and Added Value of Cultural Assets (0.79). Fourteen indicators have relational degrees below 0.70, with the lowest being Electrification Level (0.42). The mean relational degree for all 38 indicators is 0.74, with a standard deviation of 0.15, indicating significant differences in the impact of various factors on the coupling coordination degree.

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Deep Integration Development Level of Agriculture, Culture, and Tourism

Based on the GRA results from Section 4.4, the coupling coordination degree of agriculture–culture–tourism integrated development in Huangpi District is driven by a multi-layered and complex system of factors. A thorough analysis of these influencing factors requires a comprehensive examination within a three-dimensional framework encompassing internal subsystem structure, cross-system synergistic relationships, and the unique regional spatiotemporal context. The primary finding is that cultural capital constitutes the core engine of integrated development. Indicators representing the scale and vitality of market entities in the cultural industry, such as “Total Assets of Cultural Services Enterprises Above Designated Size” and “Number of Employees in Cultural Services Enterprises Above Designated Size,” show the strongest correlation between their change trends and the coupling coordination degree. This finding aligns with classical discourse on the empowerment of regional development by the cultural industry, which posits that cultural assets and human capital are key elements for activating rural value and achieving creative grafting [98,99,100]. Notably, within the internal evaluation of the cultural subsystem, these two indicators (with weights of 0.068 and 0.061, respectively), although not the highest, exhibit the strongest driving force for inter-system synergy. This reveals a deeper logic: the expansion of cultural enterprises and the aggregation of talent are significant not only for enhancing the output of the cultural industry itself (e.g., the high-weight indicator “Number of Visitors to Cultural Venues,” weight 0.206) but, more importantly, serve as active “connectors” and “sources of creativity.” They can continuously inject cultural value into agricultural landscapes and tourism experiences, fundamentally driving the synchronous enhancement of all three systems.

Integrated development is inseparable from solid physical carriers and efficiency foundations, which is reflected in the crucial supporting role of tourism reception facilities and agricultural production efficiency. The high correlation of infrastructure indicators such as “Number of Tourist Hotels” and “A-Grade Tourist Restrooms” directly corresponds to the quality of tourist experience, the lifeline of the tourism industry. Within the tourism subsystem, the “Number of Tourist Hotels” is assigned one of the highest weights (0.158), which corroborates its high influence in the GRA. This indicates that it is both a core indicator for measuring the maturity of the tourism industry and indispensable hardware for facilitating the implementation of agriculture–culture–tourism projects and achieving consumption upgrades [101,102]. Similarly, the high correlation of indicators from the agricultural system, such as “Effective Irrigation Rate” and “Land Productivity,” illustrates the foundational significance of modern agricultural production capacity [103,104]. These indicators ensure stable and high agricultural yields and present landscapes aesthetically, providing rich product support and a beautiful environmental foundation for rural leisure tourism. Together with tourism facilities, they form the “dual wheels” of integrated development, supporting the practice and transformation of cultural creativity in rural spaces.

However, Huangpi’s practice is not a simple replication of general rural development models. Its suburban location adjacent to the megacity of Wuhan injects distinct external empowerment characteristics into the integration process. This is concentrated in the high correlation of factors such as “Disposable Income of Rural Households” and “Urbanization Rate.” The income growth stems not only from the benefits of local integrated industries but also significantly from the radiation of Wuhan’s vast consumer market, the spillover of employment opportunities, and the flow of urban–rural elements [105]. This “external” increase in income and population agglomeration, brought about by spillover from the central city, provides initial capital, consumer sources, and innovative ideas for local agriculture–culture–tourism development that far exceed those available to ordinary rural areas. This makes the increase in the “Proportion of the Tertiary Industry” not merely an internal economic transformation but an inevitable outcome of receiving radiation from the regional core functions. This locational advantage endows Huangpi’s integration with stronger market reliance and development momentum from the outset, making its developmental logic fundamentally different from that of rural areas distant from metropolitan centers.

Consideration of the study period (2020–2023) necessitates a cautious interpretation of demand-side and growth data. The relatively moderate correlation of indicators directly reflecting final market demand, such as “Per Capita Cultural Consumption Expenditure of Residents” and “Number of Tourists,” is highly related to the macroeconomic context of cautious consumption and restricted travel prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic [106,107,108]. This suggests that during this special period, the resilience of integrated development relied more heavily on the aforementioned supply-side infrastructure, industrial capital, and efficiency improvements. Particular caution is required regarding the growth trend shown in 2023, as it must be recognized that it contains a component of “rebound recovery” from the low base in 2022 [109,110]. Therefore, it should not be simply attributed to the sudden maturity of the integration model. Instead, it should be viewed as the release of potential energy accumulated by existing supply-side factors after the removal of unfavorable external constraints. This analysis suggests that the policy focus in the post-pandemic era should transition from consolidating the supply-side foundation to simultaneously stimulating and matching potential consumer demand, achieving a smooth transition towards benign interaction between both supply and demand sides.