Abstract

To investigate the spatiotemporal evolution of ecosystem health in a typical rocky desertification control demonstration zone. This study utilized land use data and remote sensing imagery from 1992, 2003, 2009, 2015, and 2021. Landscape pattern analysis was employed to quantify landscape characteristics. A Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model framework was integrated to establish an ecosystem health assessment system comprising 14 indicator factors, enabling ecosystem health evaluation from the perspective of coupling landscape patterns and ecological processes. Key findings reveal: Significant cropland expansion occurred within the study area, accompanied by mutual transitions within ecological land types, yet the overall landscape structure remained relatively stable. The regional landscape underwent substantial transformations, characterized by grassland reduction alongside increases in cropland and shrubland. These changes led to decreased landscape heterogeneity and fragmentation, an increasingly dominant landscape matrix, significantly enhanced connectivity, and reduced diversity. Ecosystem health experienced an initial deterioration phase followed by gradual recovery. By 2021, a transition trend emerged where a suboptimal state prevailed, yet localized areas exhibited improved quality. Distinct variations in ecological response mechanisms were observed across different geomorphic types. Unhealthy ecosystems were predominantly distributed in areas of intensive human activity, specifically peak-cluster platforms (I), eroded platforms (III), and V-shaped valleys (V). These results underscore the necessity of considering differential ecological carrying capacities inherent to various geomorphic types during rocky desertification control. Implementing differentiated management strategies and adaptive governance is crucial for promoting the sustainable enhancement of regional ecosystem health.

1. Introduction

Karst rocky desertification is a distinctive ecological degradation phenomenon in southwestern China, characterized by a land degradation process involving severe soil erosion, large-scale bedrock exposure, and a decline in ecosystem service functions [1,2]. This region is typified by widespread carbonate rock distribution, low soil formation rates, a significant surface-underground dual hydrological structure, and highly vulnerable ecosystems [3]. Under the dual pressures of population growth and excessive land resource exploitation, vegetation coverage has decreased and landscape fragmentation has intensified. Consequently, rocky desertification has become increasingly severe, significantly disrupting regional ecological balance and constraining sustainable development [4,5,6]. Accurately assessing the ecological health status of rocky desertification areas is therefore of great scientific significance for elucidating the evolutionary mechanisms of karst ecosystems and optimizing regional sustainable development strategies.

Ecosystem health is a comprehensive concept that reflects the structural and functional attributes of an ecosystem, used to assess its vigor, organization, and resilience [7]. Contemporary ecology further regards it as an emergent property of complex adaptive systems, whose status depends on internal network efficiency [8], functional redundancy, and the capacity to maintain homeostasis [9]. Since the 1980s, scholars like Schaeffer [10] and Rapport [11,12] pioneered quantitative frameworks, driving a paradigm shift from qualitative description to multi-dimensional indicator systems. Current ecosystem health assessment methods mainly include species index methods and indicator system methods. The former is more subjective due to reliance on researcher experience and cannot accurately reflect ecosystem health, while the latter offers better objectivity by incorporating multi-faceted indicators for comprehensive evaluation [13]. Rapport initially proposed the “Pressure-State-Response” (PSR) framework model, which holistically considers the intrinsic relationships among environmental pressure, system status, and system response [14,15]. Building on international experience and adapting to China’s context, domestic scholars have developed various ecosystem health evaluation models, such as the VOR model [16], DPSI model [17], DSR model [18], and DPSIR model [19]. Among these, the “Pressure–State–Response” (PSR) model has become a mainstream tool for global ecosystem health assessment due to its clear logic and flexible structure [20]. For instance, Yin et al. [21] applied the PSR model to evaluate the ecological health of a karst plateau wetland. Han et al. [22] constructed a PSR-based indicator system to assess the ecosystem health of the entire Yangtze River Basin and its 11 provincial units from 2004 to 2022. Yang et al. [23] used the PSR model to evaluate the ecosystem health of the Panjin section in the Liaohe River Basin and analyze its driving factors. In summary, research on ecosystem health assessment has developed a relatively comprehensive system, with most studies focusing on administrative regions, watersheds, desert grasslands, wetlands, farmlands, mining areas, etc. [24,25,26]. There is also considerable research on ecosystem health evaluation in karst regions. For example, Lü et al. [27] diagnosed the ecological health of a karst watershed and explored its spatiotemporal evolution using the VORS model. Chen [28] applied the “Vigor-Organization-Resilience-Ecosystem services” (VORE) ecological security diagnosis framework to assess the ecosystem health of Qujing, a typical karst mountainous city. Wu [29] established an ecosystem health evaluation system for grasslands in the karst mountains of Guizhou.

Rocky desertification, as a specific form of ecological degradation in karst regions, has received relatively limited research focused on ecosystem health assessment within controlled areas. Furthermore, existing evaluation systems often overlook the influence of landscape patterns on ecosystem health. Quantifying the spatial distribution characteristics and dynamic trends of different landscape elements can more accurately reveal changes in ecosystem health. However, despite extensive literature on the evolution trends and driving factors of rocky desertification, the patterns of ecosystem health change during the governance process remain incompletely understood, and certain limitations persist in related assessment research. Currently, most studies in rocky desertification areas focus on administrative or watershed scales, neglecting the uniqueness of governance units as “social-ecological system” experimental sites under high-intensity human intervention. Internal governance projects (e.g., slope terrace conversion, mountain closure for afforestation, industrial restructuring) directly and rapidly reshape landscape patterns, and their driver-response mechanisms differ fundamentally from large-scale processes dominated by natural forces. Secondly, while frameworks like PSR are commonly used, many studies still treat land use/land cover (LULC) as static classification variables, ignoring the dynamic ecological process information embedded in LULC spatial configuration (i.e., landscape patterns) [30]. For instance, forest patches of the same area may have vastly different soil-water conservation and biodiversity maintenance functions depending on whether they are highly fragmented or contiguously distributed. Additionally, although international attempts have been made to integrate landscape pattern analysis into health assessment [15,25], they often lack mechanistic explanations for “why specific indices are chosen” and “how these indices represent ecological processes” [31], leading to empirical evaluation systems with limited explanatory power.

To effectively address these research gaps, mechanistic exploration within a representative area of high-intensity intervention is urgently needed. The Guanling–Zhenfeng Huajiang Rocky Desertification Comprehensive Control Demonstration Zone (hereafter “Huajiang Demonstration Zone”) provides an ideal platform for this purpose. The selection of this zone is grounded in solid scientific and policy foundations: First, it has been a nationally supported control benchmark in China since the 9th Five-Year Plan, with nearly 30 years of continuous focus. It systematically integrates biological, engineering, agronomic, and industrial measures, forming a replicable “Huajiang Model” centered on “water storage and soil management.” Second, its vegetation coverage increased dramatically from merely 3% in the early 1990s to 47% in 2023, documenting the entire process of ecological recovery under intensive human intervention. This provides an ideal empirical sample for observing the cascading mechanism of “governance input–landscape reorganization–health response.” This model has been incorporated into national technical guidelines for rocky desertification control and widely promoted in karst regions of Southwest China, endowing the research findings with clear regional extrapolation value and policy guidance significance.

Accordingly, this study selects the typical Guanling–Zhenfeng Huajiang Rocky Desertification Comprehensive Control Demonstration Zone as the research area. It aims to construct a “pattern–process–health” coupled diagnostic framework that integrates landscape pattern analysis and the PSR model. The core innovation lies in overcoming the disconnection between indicators and mechanisms in traditional assessments by systematically embedding landscape pattern indices with clear ecological implications into the PSR logical chain. This establishes a mechanistic mapping pathway from spatial pattern characteristics to key ecological processes and ultimately to ecosystem health status. Specifically, this study uses slope, comprehensive land use degree index, and human disturbance index (HDI) to represent physical stress and human activity intensity (Pressure layer). Pattern metrics such as Number of Patches (NP), Patch Density (PD), and Shannon’s Diversity Index (SHDI) are employed to characterize the landscape structural state formed under pressure drivers, linking them to underlying ecological processes like habitat fragmentation, system diversity, and landscape connectivity (State layer). Furthermore, indices like Landscape Resilience Index (LRF), Ecosystem Service Value (ESV), and Aggregation Index (AI) are used to quantify the system’s capacity to maintain or recover its structure and function under disturbance (Response layer). Centered on this framework, the research focuses on revealing how long-term rocky desertification control interventions drive the dynamic evolution of ecosystem health by reshaping landscape patterns. It further investigates whether different geomorphic units (e.g., peak-cluster depression and V-shaped canyon) exhibit significantly divergent ecological response patterns due to differences in topographic structure and hydrological conditions. The results will not only contribute to a deeper understanding of the cascading mechanism of “human intervention–pattern reorganization–health response” in fragile karst areas but also provide a transferable theoretical paradigm and practical support for promoting Nature-based Solutions (NbS) and implementing place-based adaptive management strategies in similar ecologically degraded regions globally.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Overview

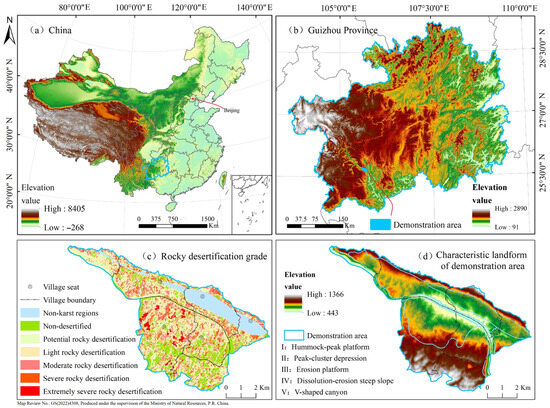

The Guanling–Zhenfeng Huajiang Rocky Desertification Comprehensive Control Demonstration Zone (hereinafter referred to as the “Huajiang Demonstration Zone”) is situated in a karst deep-cut gorge terrain along the border between Guanling County and Zhenfeng County in Guizhou Province, representing a national benchmark project for rocky desertification control. It spans geographical coordinates from 105°35′00″ E to 105°43′05″ E and 25°37′20″ N to 25°42′36″ N (Figure 1). The zone covers a total area of 51.62 km2, of which 45.38 km2 is karst terrain, accounting for 87.9% of the total area [32]. The topography descends from east to west, with elevations ranging between 450 and 1450 m above sea level, and an average annual precipitation of 1100 mm [32]. Due to well-developed vertical fissures, joints, and pores in the subsurface karst formations, rainfall rapidly infiltrates into groundwater. The soils are predominantly calcareous, characterized by thin and discontinuous layers that occur in patchy distributions. These soils are typically clay-rich, lack granular structure, exhibit low moisture content with a tendency to dry quickly, and are rich in calcium, resulting in low soil productivity and poor land quality [33]. Historically, the demonstration zone faced a severe ecological crisis, with a high proportion of moderate to severe rocky desertification. In 1996, vegetation coverage was as low as 3%, and soil erosion was extensive.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the study area.

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

This study primarily utilized Landsat series satellite remote sensing imagery, 30 m resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data, and the nationwide 30 m land cover dataset spanning 1985–2021. The Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper (TM) and Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager (OLI) remote sensing images, along with the DEM data, were sourced from the Geospatial Data Cloud platform (https://www.gscloud.cn). The land cover data were derived from the “Annual 30 m Land Cover Dataset of China and its Dynamics (1985–2019)” product published by the team led by Professor Huang Xin at Wuhan University (http://irsip.whu.edu.cn/) [34] and were extended to 2021 to align with the temporal scope of this research. Due to limitations imposed by cloud cover and data availability of historical imagery, five cloud-minimized, high-quality scenes were ultimately selected for analysis. The specific acquisition dates are 2 March 1992 (Landsat 5 TM), 18 April 2003 (Landsat 5 TM), 13 February 2009 (Landsat 5 TM), 18 March 2015 (Landsat 8 OLI), and 18 March 2021 (Landsat 8 OLI). All images were captured between February and April, corresponding to the late dry season and early growing season in the karst region of Southwest China when vegetation is in a relatively stable dormant state, thereby helping to mitigate the influence of phenological variability on vegetation index calculations.

Remote sensing image preprocessing was conducted using ENVI 5.3 software and involved the following key steps: First, radiometric calibration was performed to convert raw digital number (DN) values to top-of-atmosphere (TOA) reflectance. Subsequently, atmospheric correction was applied: the FLAASH module, based on a physical model, was employed for Landsat 5 imagery, while Landsat 8 imagery was processed by integrating the LaSRC empirical correction rationale to enhance cross-sensor consistency. Clouds and cloud shadows were identified using the Fmask algorithm and were further removed through manual inspection aided by thermal infrared and QA band information. To eliminate systematic radiometric discrepancies between Landsat 5 and 8 sensors, a radiometric normalization was performed following the method by Roy et al. [35]. This involved establishing a linear regression model using stable bare rock and dense forest areas within the study region as pseudo-invariant features (PIFs). Given the characteristic steep karst terrain of the study area, topographic correction was further applied using the C-correction method with the 30 m SRTM DEM to compensate for illumination variations caused by slope and aspect [36].

Based on the preprocessed imagery, the Fractional Vegetation Cover (FVC) for each period was calculated using the pixel dichotomy model. The NDVIsoil and NDVIveg thresholds were dynamically determined as the 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively, of the NDVI cumulative frequency distribution for each individual image date. The original land cover data classification included cropland, forest land, shrubland, grassland, water bodies, barren land, and impervious surfaces. To better align with the actual ecological and land use characteristics of the study area, “barren land” was uniformly reclassified as “unused land,” and “impervious surfaces” were reclassified as “construction land.” This resulted in a final seven-category land cover system: cropland, forest land, shrubland, grassland, water bodies, unused land, and construction land. Furthermore, based on the 30 m SRTM DEM data obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud, the study area boundary was extracted using ArcMap 10.8. A slope map was subsequently generated from the DEM for subsequent terrain factor analysis and landscape pattern zoning.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Landscape Pattern Metrics

Landscape pattern metrics serve as an effective tool for quantitatively characterizing the spatial configuration of landscapes, revealing the compositional and configurational evolution driven by land cover changes [37]. To systematically analyze the response relationship between landscape structure and ecosystem health in the study area, this research employed a regular grid of 0.3 km × 0.3 km (300 m) as the fundamental evaluation unit, based on 30 m resolution land cover and DEM data. This scale corresponds to the aggregation of 10 × 10 original pixels. It effectively preserves typical small-scale ecological patches in the karst region (such as terraces and shrub clusters) while suppressing classification noise. This approach avoids the information loss associated with overly coarse scales and the sensitivity to errors inherent in overly fine scales, adhering to the fundamental principle in landscape analysis that grain size selection must balance detail and generalization [37]. A total of 806 analysis units were generated by constructing a fishnet in ArcMap 10.8. Subsequently, the following structural landscape pattern metrics were calculated using Fragstats 4.2 software: Total Class Area (CA), Percentage of Landscape (PLAND), Number of Patches (NP), Patch Density (PD), Largest Patch Index (LPI), Landscape Shape Index (LSI), Landscape Division Index (DIVISION), Contagion (CONTAG), Aggregation Index (AI), Shannon’s Diversity Index (SHDI), and Shannon’s Evenness Index (SHEI) (see Table 1). These metrics comprehensively reflect the landscape’s compositional proportions, degree of fragmentation, complexity of patch shapes, spatial aggregation, and diversity, and have been widely employed in regional-scale land change monitoring. Given that this study did not obtain ecological process parameters such as species dispersal, habitat suitability, or resistance surfaces, functional connectivity metrics like COHESION and CONNECT were not included. As Saura & Torné [38] point out, the proper application of such metrics requires a clear ecological context; otherwise, they risk introducing subjective assumptions. Therefore, this study focuses on a structural pattern analysis that is well-supported by data and guided by clear objectives, to ensure the robustness and interpretability of the results.

Table 1.

Landscape pattern index and ecological significance.

2.3.2. Construction of the Landscape Ecological Health Diagnostic System

The ecosystem in karst rocky desertification areas is fragile and influenced by complex factors, making it difficult for a single indicator to scientifically characterize its ecological health status. Therefore, based on landscape ecology theory and drawing on existing research frameworks for ecological health assessment in mountainous landscapes [39] and karst areas [40,41,42], this study follows the principles of scientific rigor, specificity, systematicness, and feasibility. By closely integrating the environmental context of karst rocky desertification areas, a diagnostic framework suitable for the study area is constructed. The PSR (Pressure-State-Response) model framework is adopted, and 14 indicators are selected from the three dimensions of Pressure, State, and Response to establish a comprehensive evaluation system (Table 2). Among these, the “State” dimension in this study specifically refers to the spatial structure and functional attributes of the landscape ecosystem, encompassing landscape pattern indices (such as diversity, shape, fragmentation, etc.) and key ecological function indicators (such as vegetation coverage and ecosystem service value) to characterize the relatively stable structural and functional conditions of the system at present. The “Pressure” dimension focuses on indicators that directly reflect the intensity of human activity disturbance, while the “Response” dimension** reflects the system’s capacity for recovery and adaptation to external pressures. This system aims to diagnose the landscape ecological health status of karst rocky desertification areas in a systematic and comprehensive manner.

Table 2.

Indicator System for Landscape Ecosystem Health Assessment.

Stress Indicators: Field investigations establish human activity as the primary stress source. Slope gradient, the Comprehensive Land Use Intensity Index, and the Human Disturbance Index (HDI) were selected to quantify regional pressure sources. Slope gradient was derived from the SRTM DEM using the Slope Tool in ArcMap 10.8, at a 30 m resolution.

The Comprehensive Land Use Intensity Index [32] reflects the breadth and depth of land use change through the integrated outcome of multiple land use type transitions. It is calculated as:

where is the Comprehensive Land Use Intensity Index, ranging [100, 400]; is the hierarchical index for the i-th land use class: unused land = 1; forest, grassland, water bodies = 2; cropland = 3; construction land = 4; is the area proportion of the i-th land use class; is the number of land use classification levels.

The Human Disturbance Index (HDI) quantifies the intensity of anthropogenic pressure on the ecological environment, enabling further analysis of human-induced stress [43]. Based on established research, disturbance coefficients were assigned (Table 3). HDI is calculated as:

where is the human disturbance coefficient associated with the i-th land cover type; is the area of the i-th land use class; is the total study area; is the number of land use classification levels.

Table 3.

Land Landscape Types and Human Interference Intensity Coefficient.

State Indicators: These metrics reflect the current status of the natural environment and ecosystem conditions. The study selected Shannon’s Diversity Index (SHDI), Shannon’s Evenness Index (SHEI), Number of Patches (NP), Patch Density (PD), Landscape Shape Index (LSI), Contagion Index (CONTAG), Fractional Vegetation Coverage (FVC), and Landscape Division Index (DIVISION) as state indicators. Fractional Vegetation Coverage (FVC), calculated to effectively reflect regional ecological status [44], is derived as follows:

where represents the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index for a given pixel, denotes the value of pure bare soil pixels, and signifies the value of pure vegetation pixels.

Response Indicators: These metrics capture the self-regulating feedback of ecosystems following external disturbances. The study employed the Landscape Resilience Index (LRF), Landscape Aggregation Index, and Ecosystem Service Value (ESV) as response indicators.

Landscape Resilience (LRF) quantifies an ecosystem’s capacity to maintain or recover structural and functional stability after perturbation. Drawing on the methodology established by Liu Minghua et al. [45] landscape resilience coefficients specific to the study area were defined (Table 4), reflecting the differential capacity of distinct landscape types to recover or maintain ecosystem stability.

where represents the total resilience of the ecosystem; is the resilience coefficient of landscape type ; is the area of landscape type ; denotes the number of landscape types within the region; and is the total area of the study region.

Table 4.

Assignment of Landscape Resilience Values for Different Landscape Types in Karst Rocky Desertification Areas.

Ecosystem Service Value (ESV) serves as a critical metric reflecting the quality of the ecological environment. The study referenced the equivalent factor table revised by Xie Gaodi et al. [46] and existing literature on karst regions [47,48], while fully accounting for data availability, comparability, and regional representativeness. ESV coefficients for distinct landscape classes within Guizhou Province, as converted by Wang Dan et al., were adopted for regional ecological value calculation (Table 5). The ESV is calculated as follows:

Within the formula: ESV represents the total ecosystem service value; denotes the ESV coefficient per unit area for the -th landscape class; signifies the area of the -th landscape class; and n is the total number of landscape class types within the region.

Table 5.

Ecosystem service value coefficients for different landscape types (10,000 yuan/ha).

Table 5.

Ecosystem service value coefficients for different landscape types (10,000 yuan/ha).

| Primary Classification | Primary Classification | Farmland | Woodland | Grassland | Water | Construction Land | Unused Land | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provisioning services | Food production | 0.2129 | 0.0486 | 0.0449 | 0.1262 | 0 | 0 | 0.4326 |

| Raw material production | 0.0472 | 0.117 | 0.0661 | 0.0703 | 0 | 0 | 0.2954 | |

| Water supply | −0.2514 | 0.0578 | 0.03666 | 1.0479 | 0 | 0 | 0.8909 | |

| Regulating services | Gas regulation | 0.1714 | 0.3674 | 0.2324 | 0.2572 | 0 | 0.0039 | 1.0324 |

| Climate regulation | 0.0896 | 1.0995 | 0.6145 | 0.5673 | 0 | 0 | 2.3708 | |

| Environmental purification | 0.0260 | 0.3222 | 0.2029 | 0.8813 | 0 | 0.0193 | 1.4516 | |

| Hydrological regulation | 0.2880 | 0.7195 | 0.4501 | 12.1811 | 0 | 0.0058 | 13.6445 | |

| Supporting service | Soil conservation | 0.1002 | 0.4474 | 0.2832 | 0.3121 | 0 | 0.0039 | 1.1466 |

| Maintenance of nutrient cycling | 0.0299 | 0.0342 | 0.0218 | 0.0241 | 0 | 0 | 0.1100 | |

| Biodiversity | 0.0327 | 0.4074 | 0.2575 | 1.0036 | 0 | 0.0039 | 1.7051 | |

| Culture services | Aesthetic landscape | 0.0144 | 0.1787 | 0.1137 | 0.6376 | 0 | 0.0019 | 0.9463 |

| Total | 0.7609 | 3.7943 | 2.3237 | 17.1086 | 0 | 0.0385 | 24.0263 |

2.3.3. Dimensionless Normalization and Weight Determination

To eliminate dimensional differences between indicators, dimensionless normalization of the indicator values was implemented [21]. This study employed the min-max normalization method, where positive indicators were processed using Equation (7) and negative indicators using Equation (8), calculated as follows:

where is the normalized value of indicator ; is the original value of indicator ; is the minimum value of indicator ; and is the maximum value of indicator .

To ensure objective, accurate, and scientifically valid indicator weighting, the coefficient of variation method (information volume weighting) [21] was applied. This approach assigns weights objectively based on data variability: indicators exhibiting higher coefficients of variation carry greater informational significance and thus receive proportionally larger weights. Computed weights are detailed in Table 6. Weight derivation follows these formulae:

where is the mean value of indicator ; is the number of elements in ; is the -th value of indicator ; is the standard deviation of indicator ; is the coefficient of variation in indicator ; and is the weight value of indicator .

Table 6.

Weights of Indicators for Landscape Ecological Health Assessment.

2.3.4. Landscape Ecological Health Assessment Index

Based on the weights and indicator values calculated from the aforementioned formulas, the regional landscape ecological health assessment index was computed using a weighted sum comprehensive evaluation method. The health classification criteria were established with reference to relevant studies conducted by Yin et al. [21] in karst regions (Table 7). The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where is the wetland landscape ecological health evaluation index value; is the value of the -th evaluation indicator; is the number of indicators; and is the weight value of the -th evaluation indicator.

Table 7.

Ecosystem Health Level Standards.

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Change Analysis of Landscape Types

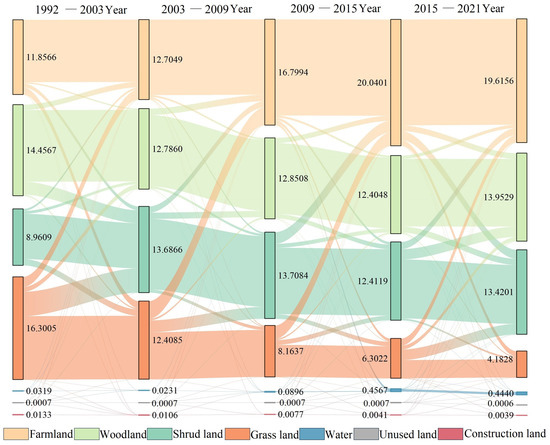

Based on the landscape type transition Sankey diagram (Figure 2) and the annual transition matrices (Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11), intense transitions between landscape types are observed within the study area. Cultivated land expanded significantly from 11.86 km2 (1992) to 19.62 km2 (2021), marking a 65.4% increase and establishing dominance. Concurrently, forest cover decreased from 14.46 km2 to 13.95 km2, while grassland experienced a severe 74.4% reduction (16.30 km2 to 4.18 km2). Unused land, water bodies, and construction land consistently comprised <1% of the total area. Transition analysis revealed distinct temporal patterns: During 1992–2003, cultivated land conversion primarily targeted grassland and shrubland, indicating farmland deintensification and ecological restoration, while mutual conversions between forest and shrubland suggested structural vegetation adjustments. From 2003 to 2009, continued agricultural expansion absorbed grassland resources, though ecological land interconversions remained stable. The 2009–2015 period saw further cultivated land encroachment onto grassland and shrubland, with minor water body expansion linked to downstream hydraulic projects. Between 2015 and 2021, cultivated land exhibited net decline through two-way transitions with forest/shrubland/grassland. Unused land remained stable in area and did not constitute a significant change category during 1992–2021. Collectively, the persistent expansion of cultivated land–predominantly through conversion of grassland and shrubland–demonstrates consolidation of agricultural production systems. Despite internal conversions among ecological land types, their aggregate stability indicates inherent ecosystem self-maintenance capacity.

Figure 2.

Temporal Sankey diagram of landscape-type transitions.

Table 8.

Landscape Type Transition Matrix from 1992 to 2003.

Table 9.

Landscape Type Transition Matrix from 2003 to 2009.

Table 10.

Landscape Type Transition Matrix from 2009 to 2015.

Table 11.

Landscape Type Transition Matrix from 2015 to 2021.

3.2. Landscape Pattern Changes from a Type-Based Perspective

To investigate the scale, connectivity, heterogeneity, and composition characteristics of regional landscape types, landscape pattern indices such as Total Class Area (CA), Largest Patch Index (LPI), Number of Patches (NP), and Percentage of Landscape (PLAND) were selected for analysis.

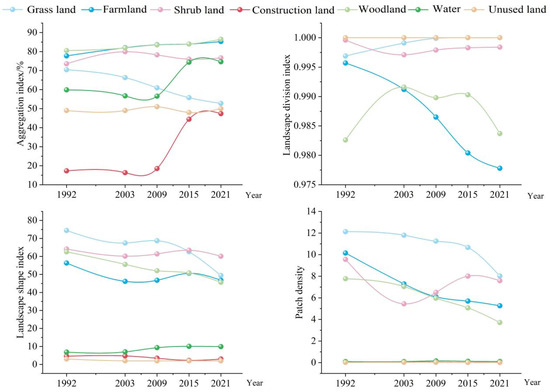

As shown in Figure 3, the total area and percentage of grassland have exhibited a significant declining trend since 1992. Combined with Figure 1, a substantial amount of grassland has been converted to shrubland, cropland, and forestland, indicating simultaneous agricultural expansion and ecological engineering efforts in the region, aimed at seeking rational allocation of land resources. In contrast, the patch area of cropland and forestland has shown an upward trend, particularly after 2003, where the increase in cropland and forestland area has been especially pronounced. This reflects the impacts of agricultural policy adjustments and ecological projects such as the Grain-for-Green Program. The patch area of shrubland has fluctuated considerably over the study period but remained relatively stable overall. Changes in the Largest Patch Index reveal the relative importance of the largest patch within each land use type. The results show that the LPI of forestland exhibited a “W”-shaped variation pattern with an overall declining trend, indicating weakened landscape connectivity. In contrast, the LPI of shrubland increased significantly, suggesting enhanced landscape connectivity. The LPI of cropland also showed an upward trend, reflecting an increasingly prominent trend toward large-scale concentration and improved connectivity of cropland. The LPI of grassland declined notably, indicating reduced landscape connectivity. Changes in the LPI of construction land were minor, while water bodies remained largely stable, and unused land experienced a slight increase. Variations in the Number of Patches reflect landscape heterogeneity and fragmentation. The data reveal that the NP of cropland, grassland, and forestland all decreased over the study period, with cropland showing the most significant reduction, reflecting adjustments and optimization in agricultural production models. In comparison, the NP of shrubland first decreased and then increased around 2015, due to the large-scale conversion of grassland to shrubland. Changes in water bodies, construction land, and unused land were relatively minor, showing slight increases.

Figure 3.

Dominance indices of landscape patterns at the type level.

In summary, the landscape pattern of the region has undergone significant changes over the past three decades, mainly characterized by a reduction in grassland, an increase in cropland and shrubland/forestland, and a decrease in landscape heterogeneity. These changes are influenced not only by natural factors but are also closely related to human activities, such as urbanization, agricultural development, and ecological conservation policies.

To further investigate the aggregation level, fragmentation degree, shape complexity, and patch distribution characteristics of the regional landscape, four landscape pattern indices were analyzed: the Aggregation Index (AI), Landscape Division Index (DIVISION), Landscape Shape Index (LSI), and Patch Density (PD).

Analysis of Figure 4 reveals a declining trend in the Aggregation Index of grassland throughout the study period, indicating progressive dispersion of grassland patches and weakened connectivity. In contrast, the AI of cropland, shrub land, woodland, water bodies, and construction land exhibited an overall increasing trend, reflecting a shift towards more concentrated and rationally allocated functional zoning of land within the study area. The AI of unused land remained relatively stable, suggesting a more uniform distribution of these land use patches. Changes in the Landscape Division Index (DIVISION) reveal the degree of landscape fragmentation. The results show a continuous decline in the DIVISION of cropland over the study period, signifying a reduction in patch numbers and a trend towards greater landscape integrity. The DIVISION of grassland, water bodies, unused land, and construction land approached 1, indicating high fragmentation and spatial dispersion. Woodland DIVISION displayed an initial increase followed by a decrease, while shrub land DIVISION decreased overall, suggesting some success in ecological restoration efforts. Variations in the Landscape Shape Index (LSI) reflect the shape complexity of landscape patches. Data indicate a decreasing trend in LSI for grassland, cropland, shrub land, woodland, and construction land, signifying a simplification in patch shapes for these land types. The LSI of water bodies increased overall, likely associated with downstream reservoir construction. Changes in Patch Density (PD) reflect the number and distribution characteristics of landscape patches. Data demonstrate declining PD for grassland, cropland, woodland, and shrub land, indicating a reduction in patch numbers, a trend towards greater landscape integrity, diminished internal ecosystem disturbance, and enhanced ecological function. The PD of construction land, unused land, and water bodies remained relatively stable with minor fluctuations.

Figure 4.

Fragmentation index of landscape patterns at the type level.

3.3. Changes in Landscape Pattern Characteristics at the Landscape Level

To systematically analyze the evolution characteristics and ecological implications of the landscape pattern in the study area from 1992 to 2021 (Table 12), this study employed a suite of landscape metrics, including CA, NP, PD, LPI, LSI, CONTAG, DIVISION, SHDI, SHEI, and AI, from three dimensions: patch characteristics, landscape heterogeneity, and spatial configuration. This integrated approach aimed to reveal the underlying logic of regional landscape restructuring within the context of rocky desertification control. At the patch scale, NP decreased from 10,148 in 1992 to 6308 in 2021, and PD synchronously dropped from 39.79 to 24.73, indicating a significant alleviation of landscape fragmentation. This trend primarily occurred between 2003 and 2009, coinciding with the deepening phase of the national Grain-for-Green Program and the intensive implementation period of local policies on “sloping farmland remediation + promotion of economic forests.” A large number of scattered, inefficient rocky desertification Farmland were consolidated into centralized management units, leading to a sharp reduction in patch numbers. However, CA remained highly stable (25,506.45–25,507.62 ha), indicating no net land loss but only internal reorganization. Meanwhile, LPI increased from 11.76 to 12.37, reflecting that economic orchards (dominated by pitaya and citrus) and Shrub land formed through enclosure are gradually becoming the dominant patches in the region. Their spatial expansion directly enhances the connectivity potential of core habitats. In terms of shape complexity, LSI decreased from 64.51 to 47.91, indicating significant regularization of patch boundaries. This is not a result of natural succession but a direct manifestation of human intervention: the construction of terraces, land leveling, and standardized orchard planting greatly reduced the tortuosity of patch edges, making agricultural and restorative vegetation patches more geometrically regular. Although such simplification may reduce edge habitat diversity, under the severe background of soil and water loss in this area, the regularized layout instead helps reduce runoff erosion and improve water retention efficiency. At the landscape heterogeneity level, the synchronous decline of SHDI and SHEI superficially reflects a trend towards type simplification. This change primarily stems from the consolidation of large areas of fragmented rocky desertification Farmland into structurally uniform but ecologically more functional economic orchards or restoration Woodland. Against the backdrop of severe degradation in this study area, although such transformation reduces landscape diversity, it significantly enhances key ecosystem functions such as vegetation coverage and soil and water conservation. It should not be simplistically equated with an overall degradation of biodiversity or ecological quality. In the dimension of spatial configuration, the continuous increase in CONTAG and AI, along with a slight decrease in DIVISION, collectively indicates enhanced landscape aggregation and weakened patch isolation. This pattern shift is highly synchronized with the launch of the “Comprehensive Rocky Desertification Control Demonstration Area” construction after 2008—through ecological corridor connectivity, contiguous development of high-standard Farmland, and mountain closure for afforestation projects, previously isolated restoration patches gradually formed spatial continuums. It is noteworthy that although the main aggregating bodies are human-managed agricultural lands, their predecessors were fragmented bare lands with extremely weak ecological functions. Therefore, this spatial integration fundamentally represents a synergistic advancement in both structural organization and functional enhancement, distinct from the ecological homogenization resulting from monocultural expansion in plains.

Table 12.

Characteristics index of landscape patterns at the landscape level.

3.4. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Landscape Ecosystem Health

3.4.1. Temporal Evolution of Landscape Ecosystem Health

This study evaluated the overall health status of the landscape ecosystem within the study area by statistically analyzing the mean values of ecological health diagnoses across individual grid cells. As shown in Table 13, the comprehensive ecosystem health assessment value exhibited a fluctuating downward trend, declining from 0.60 in 1992 to 0.57 in 2021. Consequently, the health status transitioned from “Healthy” (1992–2003) to “Sub-healthy” (2009–2021). Notably, the 2021 value (0.57) showed a slight increase compared to 2009 (0.55), suggesting potential transient positive effects of management interventions; however, it remained below the healthy threshold (≥0.6). According to the health grade classification for the Rocky Desertification Control Demonstration Area presented in Table 14, the proportion of areas classified as “Critically Impaired” (0–0.2) remained at 0% throughout the study period, indicating the absence of extremely degraded ecosystem states. The proportion classified as “Unfavorable” (0.2–0.4) was 0.37% in 1992, rose to 4.59% by 2003, and subsequently declined gradually to 1.24% by 2021, reflecting a period of transient ecosystem deterioration around 2003 followed by gradual recovery. The proportion classified as “Sub-healthy” (0.4–0.6) decreased from 50.62% in 1992 to 30.77% in 2003, then increased continuously, reaching 61.66% by 2021. This indicates that the sub-healthy state became the dominant condition in the study area, exhibiting an increasing trend since 2009. Conversely, the proportion classified as “Healthy” (0.6–0.8) declined from 48.76% in 1992 to 53.10% in 2003, followed by a continuous decrease to 36.10% by 2021, demonstrating an overall downward trend in the proportion of ecosystems exhibiting healthy conditions. The proportion classified as “Highly Healthy” (0.8–1.0) was 0.37% in 1992, increased to 4.59% in 2003, and subsequently declined year by year to 1.24% by 2021, indicating that ecosystems of high health status consistently constituted a low proportion and exhibited a declining trend.

Table 13.

Comprehensive Ecosystem Health Assessment Results for the Rocky Desertification Control Demonstration Area.

Table 14.

Classification of Comprehensive Ecosystem Health Assessment Grades for the Rocky Desertification Control Demonstration Area.

In summary, the ecosystem health status during the study period underwent a phase of initial transient deterioration followed by gradual recovery. While management measures yielded some effect, their efficacy was characterized by periodic fluctuations, potentially constrained by implementation intensity or insufficient adaptive management. Despite the decline in the “Healthy” proportion and the dominance of the “Sub-healthy” state, the absence of critically impaired conditions indicates that the overall ecosystem retained a degree of stability and resilience.

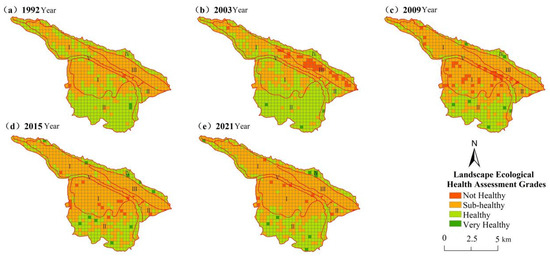

3.4.2. Spatial Evolution of Landscape Ecosystem Health

Based on the spatial distribution of the ecosystem health assessment results (Figure 5), the spatial pattern of different health grades underwent significant changes during the study period (1992–2021). Since 1992, the landscape has been dominated by sub-healthy areas, with locally distributed healthy patches, while unhealthy areas were primarily concentrated in the central and southwestern parts. By 2003, unhealthy areas had expanded and were mainly clustered in regions with dense cropland distribution. During this period, human activity intensity was high, showing clear spatial overlap between the two. In 2009, unhealthy areas gradually shifted towards the central part of the study area; this spatial shift temporally coincided with rising water levels due to reservoir impoundment downstream, potentially linked to the degradation of local vegetation from inundation. Meanwhile, healthy and near-healthy areas began to emerge and showed a trend of continuous expansion in the southern and northern fringe zones.

Figure 5.

Distribution of landscape ecological health diagnosis across grid cells under different geomorphic types in the rocky desertification control demonstration area.

By 2015, unhealthy areas had further receded, primarily persisting in the central study area. This region is characterized by relatively severe rocky desertification and quarrying activities, contributing to its lower ecological health status in the short term. By 2021, unhealthy areas had substantially decreased, and the proportion of areas in healthy grades had significantly increased. The overall pattern gradually evolved from the earlier phase of “sub-healthy dominance with local degradation” to one characterized by “sub-healthy as the primary state with local optimization” (Note: According to Table 10 data for 2021, sub-healthy areas accounted for 61.66%, while healthy areas were 36.10%; therefore, describing it as “healthy-dominant” would be inaccurate).

Further analysis integrated with geomorphological types revealed that hummocky peak valleys (I) and peak cluster depressions (II) mostly exhibited sub-healthy to healthy states. Vegetation cover recovery was better in these areas, soil and water conservation functions were stronger, and the ecosystems demonstrated relative stability. Erosion platforms (III) were primarily sub-healthy, with localized unhealthy patches. This reflects the natural vulnerability of this terrain type, characterized by fragmented topography and soil prone to erosion, which, coupled with a certain degree of anthropogenic disturbance, likely constrained the ecological recovery process. The dissolution-erosion steep slope zone (IV) showed generally good ecological health, consistent with its spatial characteristics of steeper slopes and less human disturbance. The V-shaped canyon (V) area exhibited relatively lower ecological health levels, primarily due to its more homogeneous land cover dominated by water bodies, resulting in lower landscape heterogeneity.

In summary, distinct geomorphological units exhibited clear differentiation in ecosystem health status and its evolutionary trends. Natural attributes such as topographic relief, slope, and soil water-holding capacity, combined with socioeconomic factors like human activity intensity and land use patterns, collectively form the contextual conditions for regional ecological responses. These factors likely influence vegetation recovery processes and ecosystem stability to varying degrees, thereby shaping the spatial pattern of health grades. Therefore, in comprehensive rocky desertification control, it is recommended to fully consider the inherent ecological differences and carrying capacities of different geomorphological types. Exploring differentiated management pathways and adaptive management strategies could more effectively enhance the overall health level of the regional ecosystem.

4. Discussion

Based on multi-temporal remote sensing data from 1992 to 2021, this study integrates landscape pattern analysis with the Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model to construct a coupled “Pattern-Process-Health” diagnostic framework. This framework systematically elucidates the spatiotemporal evolution of ecosystem health in the Guanling-Zhenfeng Huajiang Rocky Desertification Control Demonstration Zone. The results indicate that while regional ecological health overall exhibited a trend of “initial degradation followed by recovery,” culminating in a pattern characterized by “sub-health dominance with localized improvement” by 2021, the underlying ecological restoration pathways reveal structural contradictions and spatial heterogeneity worthy of in-depth exploration.

4.1. Deciphering the Apparent Paradox Between Landscape Structural Ordering and Ecosystem Functional Improvement

The study identified significant expansion of cultivated land alongside a substantial reduction in natural grassland. This land use/cover change (LUCC) is closely linked to human activities, including urban expansion, agricultural restructuring, and the implementation of ecological engineering policies [49]. For instance, research in Pakistan’s Deosai National Park noted that infrastructure expansion and grazing policies jointly reshape habitat patterns, significantly affecting landscape connectivity for endangered species [50]. Ecological compensation measures such as converting farmland to forest/grassland and constructing terraced fields have effectively increased vegetation coverage. However, they have also driven the large-scale cultivation of economic fruit trees, leading to the replacement of natural grassland with artificial vegetation. Concurrently, landscape fragmentation has decreased, aggregation has increased, and certain ecosystem service values (e.g., water conservation, soil retention) have improved. This phenomenon appears to contradict established ecological understanding, where agricultural intensification typically leads to landscape homogenization, habitat loss, and biodiversity decline [51,52]. This apparent paradox can be explained by the specific regional degradation context and the nature of the interventions. In the 1990s, the study area was dominated by scattered, low-yield, or abandoned steep-slope farmlands, compounded by severe rocky desertification, resulting in high surface exposure rates, sparse vegetation, and a severely threatened ecosystem. Initiated in the 2000s, comprehensive measures like “slope-to-terrace conversion” and “converting farmland to orchards” were not traditional agricultural intensification but ecological restoration-oriented land rehabilitation practices. Their core objective was to curb soil erosion and restore baseline productivity through engineering and vegetation reconstruction. Promoted economic forests (e.g., pitaya, citrus) offer both economic benefits and soil-water conservation functions, significantly reducing exposed rock area and enhancing vegetation continuity and soil stability in the short term. Therefore, the observed “ordering” of landscape structure and partial functional improvement essentially reflect a transition from a highly degraded, disordered cultivation system to a preliminarily restored, managed landscape unit. This transition yields positive effects on physio-hydrological processes, but its long-term impacts on complex ecological processes like biodiversity maintenance and nutrient cycling remain uncertain. As Tscharntke et al. [52] emphasize, monoculture-dominated agricultural landscapes, even with high vegetation cover, may weaken ecosystem multifunctionality due to low structural heterogeneity. Thus, the observed “functional improvements” are stage-specific, scale-dependent, and service-selective, and should not be equated with comprehensive recovery of overall ecosystem health. Future governance must avoid misinterpreting short-term engineering successes as ecological steady states. Proactive integration of ecological redundancy—such as retaining or reconstructing semi-natural habitats like field margin strips and forest buffers—is essential to enhance landscape heterogeneity and species coexistence potential.

Furthermore, responses to governance varied significantly across geomorphological units. Due to gentler terrain and thicker soils, hill-platform (I) and peak-cluster depression (II) areas showed significant recovery. In contrast, erosion platform (III) and V-shaped gorge (V) areas, constrained by fragmented terrain, unique hydrology, or human disturbance, maintained low health levels. This finding corroborates the “geomorphology dictates ecology” principle in karst regions, underscoring the need for tailored strategies. For instance, micro-topography modification and soil stabilization should be prioritized in erosion platforms, while optimizing aquatic ecosystem structure is crucial in V-shaped gorges to prevent habitat homogenization from water projects. Using geomorphological types as basic management units can enhance policy precision and ecological benefits.

4.2. The Phased Characteristics of Ecosystem Health Recovery and Directions for Optimizing Governance Pathways

Notably, although the comprehensive ecosystem health evaluation score improved to 0.57 in 2021 from 0.55 in 2009, it remained within the “sub-health” range, with less than 40% of the area classified as “healthy” or above. This indicates that nearly three decades of governance have yielded phased results, but the system has not yet reached an ideal steady state. Underlying reasons may include an over-reliance on engineering measures neglecting natural succession, long-term pressure from industrial models on ecological carrying capacity, and a lack of adaptive management mechanisms. Future efforts should promote a transition from “engineering-dominated” approaches to “Nature-based Solutions (NbS) + community co-governance,” strengthening the “monitoring-assessment-feedback-adjustment” cycle to achieve sustainable improvements in ecosystem health.

4.3. Methodological Basis and Applicability Boundaries of Selected Landscape Pattern Metrics

Methodologically, this study selected landscape metrics including CA, PLAND, NP, PD, LSI, DIVISION, CONTAG, AI, SHDI, and SHEI to systematically characterize structural changes in LUCC composition, fragmentation, shape complexity, aggregation, and diversity. These are standard structural metrics widely used in the FRAGSTATS platform [31], validated for applicability and interpretability in numerous regional-scale studies. It is important to note that while functional connectivity metrics (e.g., COHESION, CONNECT, CLUMPY, IJI, PROXIMITY) are valuable for assessing habitat network connectivity [38], their application typically relies on prior ecological parameters (e.g., species dispersal, landscape resistance). In the absence of local species data or validated resistance models, introducing such metrics may introduce subjectivity, weakening scientific robustness. Furthermore, using 30 m resolution data across 806 grid units (300 m × 300 m), some connectivity metrics are highly sensitive to classification noise or edge effects, potentially obscuring regional trends. In contrast, the selected structural metrics exhibit stronger robustness to data errors, more stably reflecting macro-scale pattern evolution, which aligns with the core objective of assessing landscape structural dynamics and their link to ecosystem health under rocky desertification control. Future work will incorporate functional connectivity through field surveys or species distribution models to deepen understanding of ecological processes.

4.4. Regional Adaptability of Evaluation Coefficients and Their Impact on Result Interpretation

Regarding the key coefficients in the evaluation system, the construction of the Human Disturbance Index (HDI), Landscape Resilience Factor (LRF), and Ecosystem Service Value (ESV) equivalents primarily referenced published peer-reviewed studies focusing on the karst regions of Southwest China [43,45,46,47,48]. These studies targeted areas highly similar in ecosystem type, geological setting, climate, and anthropogenic pressures. Their coefficient systems represent the most feasible approximation under current conditions lacking local empirical calibration. It must be emphasized that the core objective is not to precisely quantify absolute ESV or disturbance intensity, but to reveal the relative trends and spatial patterns of ecosystem health from 1992 to 2021. Under a unified coefficient system, such relative comparisons retain clear indicative and policy-reference value. Nonetheless, inherent karst characteristics like shallow soil and weak water retention may cause general ESV coefficients to overestimate actual service provision. This limitation highlights the urgent need for future parameter calibration through field observations, household surveys, or localized models like InVEST.

5. Conclusions

Based on multi-temporal landscape pattern analysis and ecosystem health assessment, this study elucidates the driving mechanisms and ecological effects of landscape evolution in a typical rocky desertification control area from 1992 to 2021. The conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- During the study period (1992–2021), cultivated land area increased significantly, primarily through the conversion of grassland and shrubland. This trend underscores the consolidation or reinforcement of agricultural production’s priority in regional land-use strategies. Despite internal transitions among ecological land types, the overall landscape structure remained relatively stable, demonstrating the ecosystem’s self-sustaining capacity.

- (2)

- The region underwent pronounced landscape transformations, characterized by grassland reduction, expansion of cultivated land and shrubland, and declining landscape heterogeneity. These changes were closely linked to human activities—including urbanization, agricultural intensification, and ecological conservation policies. Concurrently, the Largest Patch Index (LPI) of cultivated land rose, indicating its spatial aggregation, while grassland LPI decreased, reflecting reduced connectivity.

- (3)

- Ecosystem health exhibited a trajectory of initial deterioration followed by gradual recovery. Although governance measures were implemented, their effectiveness fluctuated temporally. By 2021, the proportion of unhealthy areas further declined, while healthy-grade zones increased significantly. This shift reveals a transition from a “sub-health-dominant, locally degraded” state toward a “health-dominant, locally optimized” pattern.

- (4)

- Ecological response mechanisms varied distinctly across geomorphic types: Peak-cluster tablelands and peak-depression landforms predominantly maintained sub-healthy to healthy states, whereas eroded platforms struggled to recover due to topographic fragmentation and anthropogenic pressures. Dissolution-erosion steep slopes retained better ecological conditions, while V-shaped valleys exhibited lower ecosystem health levels due to homogeneous land use. Consequently, rocky desertification control strategies should account for geomorphology-specific ecological carrying capacities, implementing differentiated governance and adaptive management to enhance holistic ecosystem health.

This study reveals a critical paradox in rocky desertification control: agricultural intensification enhances landscape connectivity while accelerating biodiversity decline. To reconcile production and conservation goals, we propose constructing ecological corridors in croplands and optimizing ecological dispatch mechanisms of water conservancy projects. Geomorphology-specific priorities include restoring degraded patches in eroded platforms, regulating aquatic ecosystems in V-shaped valleys, and incorporating adaptive management into policy frameworks to sustainably advance regional ecosystem health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and Z.Z.; methodology, J.Z.; software, Y.L.; validation, D.H. and J.Z.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Z.Z.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and Z.Z.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, Z.Z.; project administration, Z.Z.; funding acquisition, Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by various projects, including the Guizhou Provincial 2025 Central Government–Guided Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project, “Construction of a Deep–Time Digital Earth Evolution and Cloud–Computing Platform in Karst Mountainous Areas” (Qian Ke He Zhong Yin Di [2025] 031); Supported by Guizhou Provincial Key Laboratory Construction Project, “Guizhou Provincial Key Laboratory of Remote Sensing Big Data Intelligent Processing and Application” (Qian Ke He Ping Tai [2025] 014);and Guizhou Academy of Sciences Youth Science Fund Project: Research on the Construction of a Dynamic Monitoring and Evaluation Index System for Wetland Ecological Health in Caohai Nature Reserve (Contract No. Qianke Yuan J [2024] 18).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the data providers for all the data used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Li, Y.B. Analysis of the transformation and evolution of rocky desertification in karst mountainous areas of southwestern China. Carsolog. Sin. 2021, 40, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.K. Karst desertification is a geo-ecological disaster. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 1995, 15, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Li, S.S.; Xu, Q.; Luo, G.J. Evolution of rocky desertification in karst mountains of southwest China over the past 50 years: A case study of five sites. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 8526–8538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.L. Study on Forest Change, Vegetation Restoration and Rocky Desertification Control in Guizhou Karst Mountains. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, M.P.; Bosso, L.; Smeraldo, S.; Chiusano, M.L.; Pasta, S.; Di Pasquale, G. Shedding light on the effects of climate and anthropogenic pressures on the disappearance of Fagus sylvatica in the Italian lowlands: Evidence from archaeo-anthracology and spatial analyses. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Chen, J.; Yang, G.; Xie, H.; Li, M.; Sun, J. Dynamic evolution of rocky desertification and vegetation restoration and analysis of driving forces in Southwest Karst Region from 2000 to 2020. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0332644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, P.; Tan, C.F.; Qi, T.T. Ecosystem health assessment and prediction of the Gansu section of the Yellow River Basin based on PSR model. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 44, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulanowicz, R.E. The balance between adaptability and adaptation. Biosystems 2002, 64, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, S.E.; Fath, B.D. Fundamentals of Ecological Modelling, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D.J.; Herricks, E.E.; Kerster, H.W. Ecosystem health: I. Measuring ecosystem health. Environ. Manag. 1988, 12, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport, D.J. What constitutes ecosystem health? Perspect. Biol. Med. 1989, 33, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport, D.J.; Costanza, R.; McMichael, A.J. Assessing ecosystem health. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1998, 13, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.J.; Tao, Y.R.; Pang, Y.; Xu, Q.J.; Yu, X.M. Ecological health assessment and main influencing factors of Taihu Lake Basin based on PSR model. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2024, 14, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport, D.J.; Singh, A. An EcoHealth-based framework for State of Environment Reporting. Ecol. Indic. 2006, 6, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazbavi, Z.; Sadeghi, S.H.; Gholamalifard, M.; Davudirad, A.A. Watershed health assessment using the pressure–state–response (PSR) framework. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohibul, S.; Sarif, N.; Parveen, N.; Khanam, N.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Naqvi, H.R.; Nasrin, T.; Siddiqui, L. Wetland health assessment using DPSI framework: A case study in Kolkata Metropolitan Area. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 107158–107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.Q.; Wu, R.N.; Ma, Q.; Yang, J. Ecosystem health assessment based on DPSIRM framework and health distance model in Nansi Lake, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2016, 30, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Das, A.; Mandal, A. Research note: Ecosystem Health (EH) assessment of a rapidly urbanizing metropolitan city region of eastern India—A study on Kolkata Metropolitan Area. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, S.Z.; Xu, S.J.; Pan, Y.J. Application of PSR model in wetland ecosystem health assessment. Trop. Geogr. 2005, 25, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhao, W.; Liao, Y.; Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, L. Ecological Health Assessment of Karst Plateau Wetlands Based on Landscape Pattern Analysis. Water 2025, 17, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.X.; Wang, Y.C.; Bao, Y.F.; Wen, J.; Li, S.Z.; Chen, M.; Jia, Z.Y.; Sun, M.; Kang, J.X.; Liu, X.X. Ecosystem health assessment of the Yangtze River Basin based on PSR model. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2025, 45, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Q.; Hu, H.Q.; Zhang, Q.X.; Qin, M.E.; Zhang, M.L.; Hou, J. Ecosystem health assessment and driving factors analysis of Panjin section of Liaohe River Basin based on PSR model. Pearl River 2023, 44, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.C.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution of ecosystem health in Anhui Province from 1980 to 2015. Remote Sens. Nat. Resour. 2023, 35, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; He, M.; Meng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yun, H.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Mo, X.; Hu, B.; Liu, B.; et al. Temporal-spatial change of China’s coastal ecosystems health and driving factors analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.Q.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Z.J.; He, J.L.; He, C. Application of VOR and CVOR indices in health assessment of desert steppe in arid and windy sandy area of Ningxia: A case study of Yanchi County. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2018, 26, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, S.S.; Li, W.; Zhao, W.Q.; Huang, L.F. Ecological health diagnosis and spatiotemporal evolution of karst watershed based on VORS. J. Wuhan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 71, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Ecological Health Diagnosis and Ecological Security Pattern Construction of Typical Karst Mountainous City. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S. Study on grassland ecosystem health evaluation system in Guizhou karst mountainous area. In Proceedings of the 2015 China Grassland Forum, Inner Mongolia, China, 26 August 2015; Guizhou University: Guiyang, China, 2015; pp. 70–100. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.G. Landscape ecology: What is the state of the science? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2005, 36, 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K. FRAGSTATS Help; University of Massachusetts: Amherst, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, L.J.; Zhou, Z.F.; Zhu, C.L.; Shang, M.J. Geomorphic differentiation characteristics of karst rocky desertification and land use change: A case study of the Guanling-Zhenfeng Huajiang rocky desertification comprehensive demonstration area in Guizhou Province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 40, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.; Liang, Y.H.; Fan, Y.L.; Zhang, F.T.; Luo, X.Q. Structural characteristics of soil algal communities in Huajiang karst area of Guizhou. Guizhou Agric. Sci. 2013, 41, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Wulder, M.A.; Loveland, T.R.; Woodcock, C.E.; Allen, R.G.; Anderson, M.C.; Helder, D.; Irons, J.R.; Johnson, D.M.; Kennedy, R.; et al. Landsat-8: Science and product vision for terrestrial global change research. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 185, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teillet, P.M.; Guindon, B.; Santer, D. An assessment of terrain correction methods for Landsat MSS data. Can. J. Remote Sens. 1982, 8, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Effects of changing scale on landscape pattern analysis: Scaling relations. Landsc. Ecol. 2004, 19, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, S.; Torné, J. Conefor Sensinode 2.2: A software package for quantifying the importance of habitat patches for landscape connectivity. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Hu, J.L.; Liu, C.S.; Wang, X.Y. Remote sensing-based health diagnosis and pattern evolution of mountain landscapes: A case study of Karajun-Kurdening in Xinjiang Tianshan Natural Heritage Site. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 6451–6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; An, Y.L.; Yang, G.B. Dynamic assessment of ecosystem health in karst areas based on PSR model: A case study of Guizhou Province. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2015, 22, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, O.; Li, Y.Q.; Yang, G.B.; Li, R.S. Evaluation of ecosystem health in the national key ecological function areas for rocky desertification control in Guizhou karst region. Carsologica Sin. 2020, 39, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.P. Study on Landscape Pattern Change and Its Influencing Factors in Rocky Desertification Comprehensive Control Area. Master’s Thesis, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.G.; Peng, C.H.; Liu, X.W.; Xiang, Y.F.; Zhou, L. Ecosystem health assessment of the water-level fluctuation zone in the Three Gorges Reservoir area from 2010 to 2020 based on VOR model. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 29, 310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, K.; Yao, Y.J.; Wei, X.Q.; Gao, S.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, X. Advances in fractional vegetation cover estimation by remote sensing. Adv. Earth Sci. 2013, 28, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H.; Dong, G.H. Ecosystem health assessment of Qinhuangdao area supported by RS and GIS. Geogr. Res. 2006, 25, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.D.; Lu, C.X.; Xiao, Y.; Zheng, D. The value of ecosystem services on the alpine grassland in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2003, 21, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lan, A.J.; Fan, Z.M.; Zou, Y.C.; Li, W.Y.; Wang, R.R. Response scenario simulation of ecosystem service value to land use change in typical karst region. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 31, 308–315+325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, X.; Wu, L.H. Dynamic simulation of land use and response of ecosystem service value in Puding County from 1973 to 2030. Carsologica Sin. 2025, 44, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, N.; Hao, Z.; Sun, B.; Gao, B.; Gou, M.; Wang, P.; Pei, N. Urbanization intensifies the imbalance between human development and biodiversity conservation: Insights from the coupling analysis of human activities and habitat quality. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 3606–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, T.; Mohammadi, A.; Almasieh, K.; Bosso, L.; Ud Din, S.; Shamas, U.; Nawaz, M.A.; Kabir, M. Species distribution modelling and landscape connectivity as tools to inform management and conservation for the critically endangered Himalayan brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus) in the Deosai National Park, Pakistan. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 12, 1477480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Klein, A.M.; Kruess, A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Thies, C. Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity—Ecosystem service management. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 8, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.