Abstract

The Ebinur Lake Basin, a key ecological security barrier for windbreak and sand control in northern Xinjiang, is crucial to the ecological safety of western China and the northern sand-prevention belt. Combining the basin’s geographical characteristics, this study comprehensively evaluated ecosystem service functions from four dimensions: water conservation, soil and water conservation, windbreak and sand-fixation, and biodiversity maintenance. Simultaneously, it conducted an ecological sensitivity assessment from four aspects: soil erosion, desertification, land use, and salinization sensitivity. The assessments of the importance of ecosystem service function and ecological sensitivity results were combined to create a tiered zoning plan for the basin. The basin was divided into four first-level zones: the Ebinur Lake Water Area and Wetland Biodiversity Protection Zone, the Desert Vegetation Windbreak and Sand Fixation Ecological Restoration Zone, the Oasis Agricultural Ecological Function Protection Zone, and the Mountain Water Conservation Zone. Six second-level zones were also delineated: the Ebinur Lake Wetland National Nature Reserve, Gobi Vegetation Distribution and Soil Erosion Sensitive Zone, Desert Vegetation Restoration Zone, Jinghe-Bortala Valley Oasis Agricultural Ecological Function Zone, Mountain Water Conservation and Forest-Grass Protection Zone, and Sayram Lake Water Body. This assessment and zoning plan provide support and scientific basis for the basin’s comprehensive ecological management, integrated protection and governance of mountains, rivers, forests, farmlands, lakes, grasslands and deserts, as well as regional ecological development.

1. Introduction

Xinjiang is located in an arid inland region, distinguished by scarce precipitation and elevated rates of evaporation. In Xinjiang’s arid areas, lakes are of great significance in the water resource cycle and function as important water storage areas [1]. The lake is a key habitat for inland desert species in China and a significant indicator of ecological changes in the Junggar Basin, northern Xinjiang. Significant changes in Ebinur Lake and its surrounding wetlands over recent decades have made it a representative ecologically degraded area in northwestern China [2]. Studying the ecological restoration zoning of the Ebinur Lake Basin is essential for implementing targeted ecological regulation measures and improving the effectiveness of restoration efforts.

Research focused on identifying regional ecological issues and managing ecological spatial zoning, based on landscape ecology theory, has become a crucial approach in landscape resource conservation and territorial spatial planning [3,4]. Within this research, ecological sensitivity assessment and ecosystem service function importance assessment are fundamental evaluation indices that inform the identification of regional ecological space structure and function, spatial control zone delineation, and the preservation of ecosystem health and stability [3].

The concept of ecological sensitivity refers to how strongly an ecosystem responds to disruptions triggered by natural phenomena and human actions, embodying the possibility of latent ecological risks [5,6,7]. In contrast, the assessment of ecosystem service function importance focuses on evaluating the capacity and value of typical service functions provided by regional ecosystems, and it is specifically employed to quantify the direct and indirect benefits that humans derive from ecosystems [8].

Evaluations of ecological vulnerability and the importance of ecosystem service functions are not merely crucial instruments for ecological building, alleviating regional issues, and attaining sustainable development. They are also indispensable for pinpointing key areas for ecological conservation and restoration, as well as formulating tailored strategies [9,10,11,12].

Building on landscape ecology theory, numerous studies have developed methodologies and frameworks for evaluating ecological conservation importance, including ecosystem services [12,13,14,15,16], ecological vulnerability [17,18,19], and ecological security patterns [20]. Ever since the ecological sensitivity concept was first introduced in the 1960s, the analytical methods within this domain have advanced in tandem with the progress of science and technology [21]. Various scholars have conducted studies on evaluating watershed ecological function importance [22,23,24] and ecological sensitivity assessments [22,23,25]. There are two typical paradigms for ecological zoning in arid basins worldwide. One is represented by the Aral Sea Basin, where salinization is incorporated into the zoning system, but the adopted multi-layer visual interpretation method overlooks the complexity of ecological degradation in the same region [26]. The other paradigm is exemplified by the Lake Urmia Basin in Iran, which assesses vegetation degradation risks using ecosystem service models [27] yet fails to identify salinization as an independent stressor, potentially leading to the underestimation of degradation risks in salinization-dominated areas. Both paradigms regard salinization as a derivative issue and ignore its significant impacts and interactive effects. The method for ecological restoration zoning in the Ebinur Lake Basin can further optimize relevant studies in the aforementioned regions.

Since the 1950s, with the decrease in inflow into Ebinur Lake, intense evaporation has led to soil salt accumulation and exacerbated soil salinization. Salinization stands as one of the critical unignorable factors in the assessment of ecosystem sensitivity within this region. The environmental conditions in the Ebinur Lake Basin are characterized by intense winds, elevated salinity and alkalinity levels, frequent dust storms, and overall harshness. Research focused on high-salinity and strong-wind environments is currently limited [22,23,24,25].

Conventional frameworks for ecological restoration zoning take soil erosion, desertification, and other such issues as core indicators, which exhibit significant limitations when applied in arid and high-salinity basins. Under the dual pressures of global ecological degradation and constrained agricultural sustainable development, soil salinization has evolved into a critical environmental challenge that cannot be overlooked. It not only impairs agricultural productivity and ecosystem integrity [28], reduces plant diversity and disrupts microbial communities [29], but also further undermines the stability of wetland ecosystems [30], exacerbates ecosystem sensitivity, and poses a severe threat to regional and even global ecological security. The absence of salinization sensitivity assessment fails to match the characteristics of ecological processes in arid and high-salinity basins, which will lead to the misjudgment of ecological sensitivity in the Ebinur Lake Basin and result in a lack of targeting in basin restoration efforts. It is therefore imperative to reconstruct the indicator system to ensure the accuracy of the zoning logic.

This study introduces improved indicators for evaluating ecological function importance and sensitivity, including the addition of salinization sensitivity to the ecological sensitivity evaluation framework. Based on a thorough assessment of the importance of ecosystem service functions and ecological sensitivity within the Ebinur Lake Basin, this research puts forward ecological restoration zoning. This zoning aims to support the integrated protection and systematic governance of the basin’s various ecosystems, such as mountains, waters, forests, farmlands, lakes, grasslands, and deserts. The core logic of this study—“identifying regional dominant stressors + calibrating indicators for local conditions”—is applicable to global arid and high-salinity basins, such as the Aral Sea in Central Asia, the Great Salt Lake in the United States, and Lake Eyre in Australia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

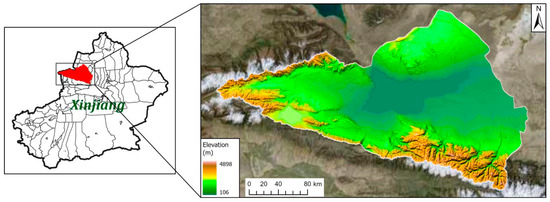

The Ebinur Lake Basin spans 43°38′–45°52′ N and 79°53′–85°15′ E, covering an area of 5.03 × 104 km2, with altitudes ranging from 183 m to 4874 m (Figure 1). Situated in a depression encircled by mountains on three sides, Ebinur Lake, which happens to be the biggest saline lake in Xinjiang. The lake area is characterized by diverse natural landscapes, including waters, swamps, tidal flats, stony deserts, sandy deserts, and loess deserts. The basin experiences low precipitation, abundant sunlight, and intense evapotranspiration, typical of a temperate continental climate. Soils in the basin are primarily composed of alluvial, lacustrine, and sandy aeolian deposits, with predominant types including gray desert soil, gray-brown desert soil, and aeolian sandy soil [31]. The imbalance between evaporation and precipitation has led to extensive soil salinization and hardening in the surface soil [32].

Figure 1.

Location of the study area and DEM.

2.2. Data Sources

This study primarily used data from the Digital Elevation Model (DEM), Fractional Vegetation Cover (FVC), Net Primary Productivity (NPP), meteorological, land use, and soil type datasets (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of Dataset Information.

The Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn) was the source from which DEM data were acquired, and these data had a spatial resolution of 30 m. The DEM was utilized to generate slope and aspect data for the study region. The Google Earth Engine cloud platform was utilized to compute FVC and NPP data, which stand for multi-year averages.

The Resource and Environmental Science Data Center (http://www.resdc.cn) was the source of meteorological and land use data. The meteorological dataset contains elements such as air temperature, precipitation, evaporation, and wind speed.

The Harmonized World Soil Database v2.0 (HWSD2) was utilized to acquire soil type data, and based on this data, the soil infiltration and erodibility factors (K) were computed.

The core data of this study followed a unified temporal benchmark (1990–2020, 5-year interval, growing season May–October), and all evaluation indices were calculated based on temporally synchronized data. DEM was used as static data, while soil type and land use type data were applied as the latest available datasets because their inherent properties precluded multi-year averaging. NPP data was derived from the MOD17A3HGF.061 product (start date: 1 January 2001), leading to incomplete temporal matching with FVC and meteorological data. Although these temporal inconsistencies may slightly affect result accuracy, they posed no critical impacts on the core findings at the watershed scale: DEM, soil type and land use type changed minimally during the study period, and the 20-year average NPP data was sufficient given that interannual variation was not analyzed in this study.

2.3. Methods

Targeting the ecological issues in the Ebinur Lake Basin, such as lake surface shrinkage [33], wetland area reduction [34], severe vegetation degradation [35], and prominent soil salinization [36,37], this study comprehensively assessed the importance of ecosystem service functions of the basin by selecting indicators from four dimensions: water conservation, soil retention, sand fixation, and biodiversity maintenance. Additionally, ecological sensitivity was evaluated using indicators for soil erosion, desertification, land use, and salinization sensitivity. All factors underwent dimensionless processing and were normalized to values between 0 and 1 before calculation.

2.3.1. The Assessment of the Significance of Ecosystem Function

The water conservation function index (WR) is calculated by multiplying the multi-year average of net primary productivity (1994–2024) (NPPmean), soil infiltration factor (Fsic), multi-year average precipitation factor (Fpre), and slope factor (1 − Fslo) (Equation (1)).

The soil and water conservation service capacity index (Spro) is calculated by multiplying the multi-year average of net primary productivity (NPPmean), soil erodibility factor (1 − K), and slope factor (1 − Fslo) (Equation (2)).

The ecosystem windbreak and sand-fixation service capacity index (Sws) is calculated by multiplying the multi-year average of net primary productivity (NPPmean), soil erodibility factor (K), multi-year average climatic erosivity factor (Fq), and surface roughness (D) (Equation (3)).

Among them: Fq can be calculated using wind speed, evaporation, and precipitation data. D can be calculated from the slope gradient.

The ecosystem biodiversity maintenance service capacity index (Sbio) is calculated by multiplying the multi-year average of net primary productivity (NPPmean), multi-year average precipitation factor (Fpre), Multi-year average temperature (Ftem), and Elevation factor (1 − Falt) (Equation (4)).

Taking the evaluation results of four individual ecosystem service function importance as factors, the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) was used to determine the weight of each factor, and the ecosystem function importance index (ECOFI) was constructed, with the calculation formula as follows (Equation (5)):

The specific process for determining weights using the AHP is as follows: Five experts with long-term research experience in desertification control were invited. For the evaluation of ecosystem function importance, a three-level indicator system was constructed: “Ecosystem Function Importance—Water Conservation, Soil and Water Conservation, Windbreak and Sand Fixation, Biodiversity Maintenance—Specific Evaluation Indicators”. Experts compared the relative importance of indicators pairwise and assigned values. The average value method was used to integrate expert opinions, and a judgment matrix was finally formed. The consistency ratio (CR) was adopted to test the rationality of the judgment matrix, with CR = 0.008, which passed the consistency test (Table 2).

Table 2.

AHP results for the ecosystem service function importance.

2.3.2. Evaluation of Ecosystem Sensitivity

Soil erosion sensitivity (A) was evaluated by integrating four factors: precipitation erosivity (R), soil erodibility (K), topographic relief (LS), and vegetation coverage (FVC) (Equation (6)) [38,39]:

Precipitation and soil erodibility, as well as topographic relief, are positively correlated with soil erosion sensitivity. However, higher vegetation coverage corresponds to lower soil erosion risk; therefore, the above formula was revised as follows (Equation (7)):

The desertification comprehensive index (DCI) based on weighted linear combination [40] was selected to represent desertification sensitivity, with the calculation formula as follows (Equation (8)):

where FVCnor is the normalized fractional vegetation coverage, TVDInor is the normalized temperature vegetation drought index, Albedonor is the normalized apparent reflectance index, LSTnor is the normalized land surface temperature index, TGSInor is the surface soil grain size index, MSAVInor is the normalized modified soil-adjusted vegetation index.

Referring to previous studies on land use sensitivity [41,42,43], the land use sensitivity (Lu) was determined. Specifically, water areas were classified as extremely sensitive, forestlands and grasslands as highly sensitive, croplands as moderately sensitive, construction lands as slightly sensitive, and unused lands as low sensitive, with assigned values of 1, 0.75, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.01, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Classification of land use sensitivity.

Given the high-salt environment of the Ebinur Lake Basin and the scarcity of existing relevant research, this study incorporated the salinization sensitivity evaluation indicator into the ecosystem sensitivity evaluation system based on regional characteristics. Referring to Wang’s [44] evaluation of the soil salinization sensitivity for various land use types in the Ebinur Lake area of Xinjiang, the salinization sensitivity indices (Lsalt) for croplands, forestlands, water regions, urban and rural construction lands, and unutilized lands were 0.0413, 0.0450, 0.0467, 0.0546, 0.0644, and 0.0771, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Salinization sensitivity indices for different land use types.

Treating the evaluation outcomes of four individual ecosystem sensitivity metrics as core factors, the weight assignment of each factor was completed using the AHP. Subsequently, an integrated evaluation index for ecosystem sensitivity was constructed, with the calculation formula as follows (Equation (9)):

The same AHP method was adopted to evaluate ecosystem sensitivity, with a consistency ratio (CR) of 0.017, which passed the consistency test (Table 5).

Table 5.

AHP results for the ecosystem sensitivity.

2.3.3. The Comprehensive Ecosystem Evaluation Index

The values of ecosystem function importance and ecosystem sensitivity were weighted and superimposed, and the expert scoring method was adopted to determine the weights. The comprehensive ecosystem evaluation index (CEEI) was then constructed, serving as the data basis for ecosystem zoning. The calculation formula is as follows (Equation (10)):

3. Results

3.1. Ecosystem Service Function Importance Assessment

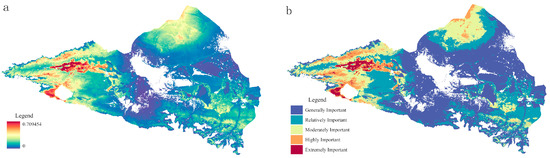

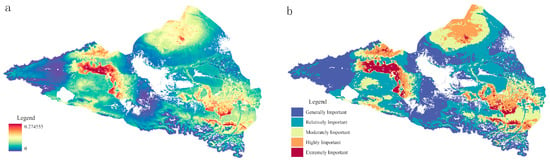

3.1.1. Results of Water Conservation Function Assessment

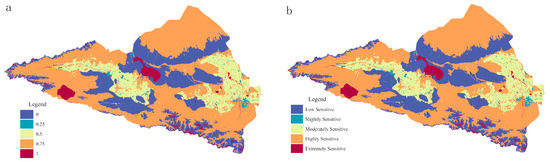

The water conservation service capacity index was calculated to assess the importance of water conservation functions in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 2a). The results were classified into five grades-Extremely Important, Highly Important, Moderately Important, Relatively Important, and Generally Important-using the natural breaks classification method in ArcGIS Pro 3.4.0 (Figure 2b). This method, based on the clustering principle, identifies natural discontinuities between samples and is commonly used in ecosystem assessments [45].

Figure 2.

(a) Water conservation function importance assessment results (b) Water conservation function importance grading.

The values of water conservation function importance in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0 to 0.709454. Specifically, values between 0.347772 and 0.709454 were categorized as Extremely Important, covering 1.98% of the basin area, primarily in the southwestern mountainous areas and the western oasis. Areas classified as Moderately Important or higher accounted for 24.31%, distributed mainly in the mountainous regions and oases in the west and north, as well as small parts of the southeast. The Generally Important grade, which dominated 48.2% of the basin area, was mainly located in the piedmont Gobi in the north and south and the sandy land to the east of Ebinur Lake.

3.1.2. Results of Soil Conservation Function Assessment

The soil conservation service capacity index was calculated to assess the importance of soil conservation functions in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 3a). The results were categorized into five grades (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Soil conservation function importance assessment results; (b) Soil conservation function importance grading.

The values of soil conservation function importance in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0 to 0.529141. Specifically, values between 0.213731 and 0.529141 were classified as Extremely Important, covering 3.84% of the basin area, mainly in the western and southern mountainous regions, as well as the western oasis. Areas categorized as Moderately Important or higher accounted for 32.92%, primarily in the mountainous regions within the basin and the oasis west of Ebinur Lake. The Generally Important grade, which covered 36.92% of the basin area, was mainly located in the piedmont Gobi within the basin and the sandy land to the east of Ebinur Lake.

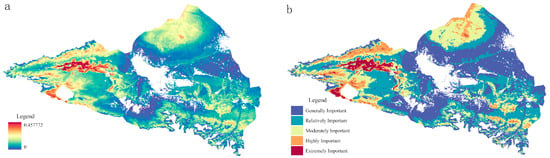

3.1.3. Results of Sand Fixation Function Assessment

The sand fixation service capacity index was calculated to assess the importance of sand fixation functions in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 4a). The results were classified into five grades (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Sand fixation function importance assessment results; (b) Sand fixation function importance grading.

The values of sand fixation function importance in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0 to 0.0131807. Specifically, values between 0.001912 and 0.0131807 were classified as Extremely Important, covering only 0.3% of the basin area, primarily in the mountainous regions. Areas categorized as Moderately Important or higher accounted for just 2.04% of the basin area, sparsely distributed in the mountainous regions. The Generally Important grade dominated the basin, covering 84% of the area, and was distributed across most parts of the basin.

3.1.4. Results of Biodiversity Conservation Function Assessment

The biodiversity maintenance service capacity index was calculated to assess the importance of biodiversity conservation functions in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 5a). The results were classified into five grades (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) Biodiversity conservation function importance assessment results; (b) Biodiversity conservation function importance grading.

The values of biodiversity conservation function importance in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0 to 0.274555. Specifically, values between 0.145352 and 0.274555 were classified as Extremely Important, covering 3.89% of the basin area, primarily in the western oasis and a small portion in the southeastern mountainous areas and oases. Areas categorized as Moderately Important or higher accounted for 33.79% of the basin area, mainly in the eastern oasis, northern mountainous regions, and the western oasis. The Relatively Important grade dominated the basin, covering 34.11% of the area, primarily in the piedmont Gobi in the north and southwest, the southern mountainous areas, and the sandy land east of Ebinur Lake.

3.1.5. Results of Ecosystem Function Importance Assessment

The comprehensive ecosystem assessment index was calculated to evaluate the importance of ecosystem functions in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 6a). The results were classified into five grades (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Ecosystem function importance assessment results; (b) Ecosystem function importance grading.

The values of ecosystem function importance in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0 to 0.457772. Specifically, values between 0.236964 and 0.457772 were classified as Extremely Important, covering 3.03% of the basin area, primarily in the western oasis and the mountainous areas west of Sayram Lake, with a small portion in the northern mountainous regions. Areas categorized as Moderately Important or higher accounted for 31.07% of the basin area, distributed mainly in the mountainous regions and oases within the basin. The Generally Important grade dominated the basin, covering 37.55% of the area, primarily in the piedmont Gobi within the basin and the oasis east of Ebinur Lake.

3.2. Ecosystem Sensitivity Assessment

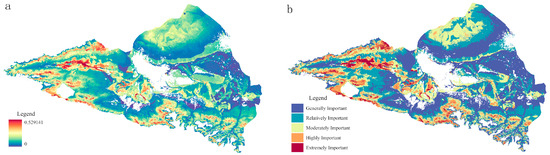

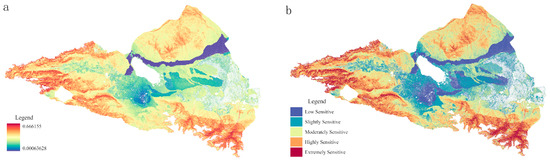

3.2.1. Results of Soil Erosion Sensitivity Assessment

The soil erosion sensitivity index was calculated to assess soil erosion sensitivity in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 7a). The results were classified into five grades [46] (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

(a) Soil erosion sensitivity assessment results; (b) Soil erosion sensitivity grading.

The values of soil erosion sensitivity in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0 to 0.666155. Specifically, values between 0.289973 and 0.666155 were classified as Extremely Sensitive, covering 12.2% of the basin area, primarily in the western and southeastern mountainous regions, with a small portion in the northern mountainous areas. Areas categorized as Moderately Sensitive or higher accounted for 68.12% of the basin area, distributed mainly in the mountainous regions, piedmont Gobi, and sandy land to the east of Ebinur Lake. The Moderately Sensitive grade dominated the basin, covering 31.22% of the area, primarily in the piedmont Gobi, the western oasis, and the sandy land to the east of Ebinur Lake.

3.2.2. Results of Desertification Sensitivity Assessment

The comprehensive desertification index was calculated to assess desertification sensitivity in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 8a). The results were categorized into five grades (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

(a) Desertification sensitivity assessment results; (b) Desertification sensitivity grading.

The values of desertification sensitivity in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0 to 0.689134. Specifically, values between 0.538286 and 0.689134 were classified as Extremely Sensitive, covering 33.97% of the basin area, the largest proportion for any sensitivity grade. This grade was primarily distributed in the Gobi areas in the north, southwest, and southeast of the basin, as well as the sandy land to the east of Ebinur Lake. Areas categorized as Moderately Sensitive or higher accounted for 74.96% of the basin area, mainly in the mountainous regions, piedmont Gobi, and the sandy land to the east of Ebinur Lake.

3.2.3. Results of Land Use Sensitivity Assessment

Land use sensitivity values were assigned to different land use types to assess land use sensitivity in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 9a). The results were classified into five grades (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

(a) Land use sensitivity assessment results; (b) Land use sensitivity grading.

The land use sensitivity values in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0 to 1. Specifically, a value of 1 corresponded to the Extremely Sensitive grade, covering 3.29% of the basin area, primarily in the water areas of Ebinur Lake, Sayram Lake, and snow-and-ice-covered regions in the mountains. Areas classified as Moderately Sensitive or higher accounted for 71.3% of the basin area, distributed mainly in regions within the basin, excluding water bodies and construction land. The Highly Sensitive grade dominated the basin, covering 53.62% of the area, primarily in the mountainous regions, piedmont Gobi, and sandy land to the east of Ebinur Lake.

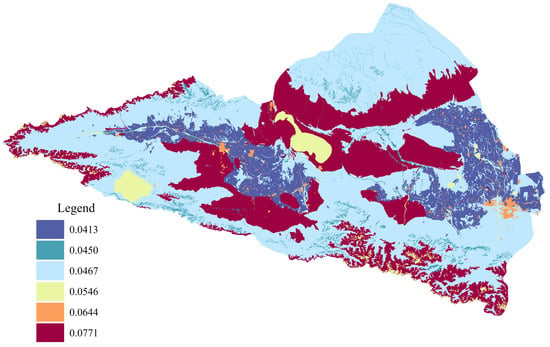

3.2.4. Results of Salinization Sensitivity Assessment

Salinization sensitivity values were assigned to different land use types to assess salinization sensitivity in the Ebinur Lake Basin. The salinization sensitivity results were categorized into six classes, with higher numerical values indicating greater sensitivity.

The salinization sensitivity values in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0.0413 to 0.0771 (Figure 10). The specific values and their corresponding area proportions are presented in Table 6.

Figure 10.

Salinization sensitivity assessment results.

Table 6.

Area proportions of different salinization sensitivity indices.

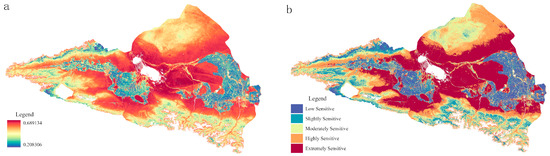

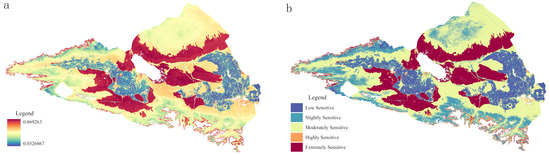

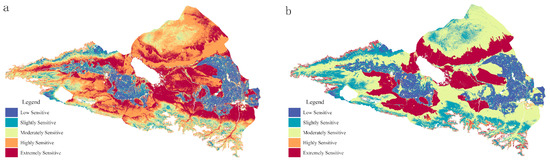

3.2.5. Results of Ecosystem Sensitivity Assessment

The comprehensive ecosystem sensitivity assessment index was calculated to evaluate ecosystem sensitivity in the Ebinur Lake Basin (Figure 11a). The results were classified into five grades (Figure 11b).

Figure 11.

(a) Ecosystem sensitivity assessment results; (b) Ecosystem sensitivity grading.

Ecosystem sensitivity values in the Ebinur Lake Basin ranged from 0.0326867 to 0.869263. Specifically, values between 0.678983 and 0.869263 were classified as Extremely Sensitive, covering 23.2% of the basin area, primarily in the piedmont Gobi in the southern and northern parts of the basin, as well as the sandy land in the central basin. Areas classified as Moderately Sensitive or higher accounted for 65.33% of the basin area, distributed mainly in the mountainous regions, piedmont Gobi, and sandy land to the east of Ebinur Lake. The Moderately Sensitive grade dominated the basin, covering 39.86% of the area, primarily in the piedmont Gobi and northern mountainous regions.

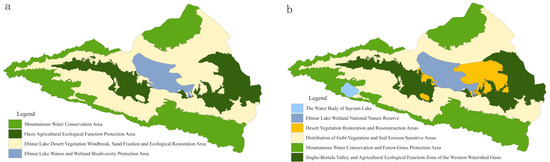

3.3. Comprehensive Evaluation Results and Zoning

Ecological protection and restoration is a dynamic optimization process that begins with a holistic approach, considering the interactive effects of various ecological elements and coordinating their spatial allocation [33]. Based on analyses of ecosystem characteristics, functions, and sensitivity, this study delineated the ecological protection and restoration zones of the Ebinur Lake Basin, incorporating physical geographical features (e.g., topography and land cover) and addressing typical ecological issues within the basin.

Given the significant ecological importance of the Ebinur Lake Wetland National Nature Reserve, whose protection and management strategies differ from those of other regions, it was designated as a separate first-level zone, without further second-level zoning. By synthesizing ecosystem function importance and sensitivity assessments, along with topographic, geomorphic, and land cover data, the Ebinur Lake Basin was divided into four first-level zones and six second-level zones. The four first-level zones are: (1) Ebinur Lake Water Area and Wetland Biodiversity Protection Zone; (2) Ebinur Lake Desert Vegetation Sand-Fixation Ecological Restoration Zone; (3) Oasis Agricultural Ecological Function Protection Zone; and (4) Mountain Water Conservation Zone. Among these, the first-level “Ebinur Lake Desert Vegetation Sand-Fixation Ecological Restoration Zone” was subdivided into two second-level zones: the “Gobi Vegetation Distribution and Soil Erosion Sensitive Zone” and the “Desert Vegetation Restoration and Reconstruction Zone.” Similarly, the first-level “Mountain Water Conservation Zone” was subdivided into two second-level zones: the “Mountain Water Conservation and Forest-Grass Protection Zone” and the “Sayram Lake Water Body.”

The Ebinur Lake Water Area and Wetland Biodiversity Protection Zone is situated around the Ebinur Lake water area and along the primary wind path of Alashankou. It serves as the primary sand source for this wind path and is a key area for biodiversity protection. Its dominant ecological functions include landscape and climate regulation, desertification control, and biodiversity conservation.

The Ebinur Lake Desert Vegetation Sand-Fixation Ecological Restoration Zone extends from the Mountain Water Conservation and Forest-Grass Protection Zone toward the oases and the eastern side of Ebinur Lake. Its primary ecological functions include vegetation protection, soil and water conservation, sand fixation, and vegetation restoration. Based on comprehensive evaluation results, it is subdivided into two second-level zones: the Gobi Vegetation Distribution and Soil Erosion Sensitive Zone, and the Desert Vegetation Restoration and Reconstruction Zone. The former is characterized by a fragile ecological environment and severe soil erosion, while the latter faces significant desertification, making vegetation restoration especially important.

The Oasis Agricultural Ecological Function Protection Zone is located in the central Ebinur Lake Basin, where economic activities are intensive and environmental development significantly impacts the basin’s ecological environment. Its key ecological functions are agricultural production and residential living. This zone includes one second-level zone: the “Jinghe-Bortala Valley and Western Basin Oasis Agricultural Ecological Function Zone.”

The Mountain Water Conservation Zone spans the southern, western, and northern parts of the basin and serves as the primary water source for the region. It features diverse ecosystems, with key ecological functions including water conservation, landscape provision, climate regulation, and tourism support. According to the comprehensive evaluation, this zone is divided into two second-level zones: the Mountain Water Conservation and Forest-Grass Protection Zone, and the Sayram Lake Water Body. The former is the basin’s primary water supply, while the latter, an alpine lake, plays a critical role in climate regulation and supports a rich variety of ecosystems in its surrounding areas.

The specific zoning results are presented in Figure 12, with area details, dominant ecological functions, and characteristics of each zone provided in Table 7.

Figure 12.

(a) First-level zones of the Ebinur lake basin; (b) Secondary-level zones of the Ebinur lake basin.

Table 7.

Zones and their characteristics in the Ebinur Lake basin.

4. Discussion

The spatial pattern of the comprehensive ecosystem evaluation in the Ebinur Lake Basin is jointly shaped by natural ecological processes and human activities. Regions with high ecosystem function importance are predominantly concentrated in the Mountainous Water Conservation and Forest-Grass Protection Area and the Jinghe-Bortala Valley and Agricultural Ecological Function Zone of the Western Watershed Oasis, which reflects the synergistic effects of precipitation distribution, topographic features, and vegetation coverage. Owing to relatively abundant precipitation and high vegetation coverage, the western mountainous regions act as critical zones for water conservation and soil erosion control. In contrast, the oasis agricultural areas have enhanced ecosystem productivity and biodiversity conservation capacity through artificial irrigation and agricultural practices. On the other hand, the Desert Vegetation Restoration and Reconstruction Areas and the Distribution of Gobi Vegetation and Soil Erosion Sensitive Areas are primarily constrained by harsh hydrological conditions and sparse vegetation cover. This spatial pattern is consistent with findings from studies on arid inland basins worldwide, such as the Aral Sea Basin in Central Asia and the Lake Urmia Basin in Iran, all highlighting the dominant role of water resource distribution in driving the spatial differentiation of ecological functions [47,48].

The Desert Vegetation Restoration and Reconstruction Areas are concentrated on the eastern side of Ebinur Lake, exhibiting high ecological sensitivity. Due to the arid and rainless climate in the Ebinur Lake Basin, intense surface evaporation often leads to the formation of several centimeters thick salt crusts, resulting in high salinization sensitivity [44]. Furthermore, this region is characterized by extremely low values of various vegetation indices and a high drought index, which contribute to a severe desertification index. Under the combined effects of these factors, the Desert Vegetation Restoration and Reconstruction Areas have become the most ecologically sensitive region within the basin.

Specific recommendations for ecological restoration include:

Ebinur Lake Wetland National Nature Reserve: Maintain wetland water conditions and strengthen biodiversity conservation.

Gobi Vegetation Distribution and Soil Erosion Sensitive Area: Implement enclosure measures, prohibit engineering projects that cause soil erosion, and prioritize soil and water conservation.

Desert Vegetation Restoration and Reconstruction Area: Strictly prohibit random logging, increase vegetation coverage, and establish windbreaks and sand-fixation forests.

Jinghe-Bortala Valley and Oasis Agricultural Ecological Function Protection Area: Promote water-saving irrigation and high-efficiency agricultural technologies to reduce agricultural water use impacts on lake recharge.

Mountainous Water Conservation and Forest-Grass Protection Area: Protect biodiversity, designate grazing-prohibited and grazing-limited areas, enhance water storage capacity, reduce water interception, and increase inflow to Ebinur Lake.

Sayram Lake Water Body: Reduce sediment, floating objects, and non-point source pollutants, and strengthen water quality and wildlife monitoring.

By implementing systematic governance aligned with the dominant functions of each zone, the overall restoration and sustainable ecological function cycle of the basin will be enhanced.

The rational regulation of water resources in the inflowing rivers of the lake can only be achieved by fully coordinating the relationships between agricultural water use, industrial water use, and ecological water use, which involves the coordination issue among the watershed water resource management departments. However, the feasibility of implementing enclosure measures and prohibiting engineering projects that cause soil erosion is constrained by pastoral and economic factors. Strictly prohibiting illegal logging and increasing vegetation coverage can enhance soil and water conservation capacity; nevertheless, under conditions of extreme aridity and high salinity-alkalinity, challenges exist in the selection of tree species and their survival rate at a controllable cost.

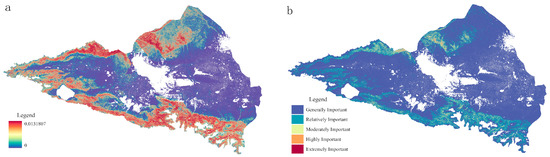

This study innovatively incorporates salinization sensitivity into the evaluation system, addressing the limitations of traditional frameworks in high-salt environments of arid regions. As a prominent ecological issue in the Ebinur Lake Basin, salinization not only directly affects soil quality and crop growth [28,29], but also impairs ecosystem stability and resilience by altering soil microbial community structures [30]. Compared with traditional evaluations that only focus on soil erosion and desertification, the introduction of the salinization sensitivity indicator makes the zoning results more consistent with the actual conditions of the basin. To compare the impact of the salinization sensitivity indicator on ecosystem sensitivity, the ecosystem sensitivity was recalculated excluding salinization sensitivity, and the resulting raster was classified, as shown in Figure 13a. The ecosystem sensitivity results including the salinization sensitivity indicator are presented in Figure 13b. Without the salinization sensitivity indicator, the areas of extremely sensitive and highly sensitive regions expand outward (accounting for 62.81% of the total area), leading to a large number of moderately sensitive regions being classified as highly sensitive, which fails to highlight the urgency of governance in the Desert Vegetation Restoration and Reconstruction Areas and the Distribution of Gobi Vegetation and Soil Erosion Sensitive Areas. The comparison indicates that for the Ebinur Lake Basin, it is more reasonable to introduce the salinization sensitivity indicator in the study of ecosystem sensitivity.

Figure 13.

(a) The ecosystem sensitivity grading without salinization factor; (b) The ecosystem sensitivity grading with salinization factor.

Compared with earlier landscape ecological zoning studies of the Ebinur Lake Basin based on 3S technology [49,50], the zoning scheme proposed in this study has achieved significant improvements in both data granularity and indicator comprehensiveness. Over the past two decades, profound changes have occurred in the basin’s land use structure, hydrological conditions, and ecological policies, rendering the earlier zoning results inadequate to meet current management needs. By leveraging cloud computing platforms such as Google Earth Engine, this study realizes rapid processing and dynamic analysis of multi-period remote sensing data, enhancing the timeliness and spatial precision of the zoning. Furthermore, the zoning results not only align with the national concept of integrated management of “mountains, rivers, forests, farmlands, lakes, grasslands, and deserts” but also provide a scientific basis for delineating ecological protection red lines and arranging ecological restoration projects at the basin scale [4]. The first-level zoning facilitates macro-strategic planning, such as designating the Mountainous Water Conservation and Forest-Grass Protection Area as a key guaranteed zone for ecological investment and the Desert Vegetation Restoration and Reconstruction Areas as a risk prevention and control zone. The second-level zoning can guide more specific engineering layouts.

However, although the weight assignment using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) in this study passed the consistency test (CR < 0.1), it is still subject to the influence of experts’ subjective judgments. When applied to semi-arid and low-salinity-alkalinity basins, the zoning scheme of this study requires reducing the weight of the salinization indicator and calibrating localized parameters. Furthermore, the evaluation results of oasis agricultural areas need to be interpreted with caution: their ecosystem function importance is highly dependent on human activities such as artificial irrigation, and their stability is susceptible to changes in water resource allocation policies and cropping structures. In contrast, due to the strong spatiotemporal heterogeneity of soil salt dynamics, insufficient density of monitoring data may introduce considerable uncertainty into the assessment of salinization sensitivity. These limitations point out directions for future research; integrating high-resolution time-series remote sensing data with fixed-point monitoring networks to construct a dynamic indicator system can further improve the adaptability and reliability of the zoning scheme.

Compared with similar domestic and international studies, the zoning scheme of this study exhibits distinct differential advantages. Domestic zoning studies either neglect the impact of salinization or fail to consider the synergistic effects of stressors, resulting in insufficient targeting of governance measures. Internationally, the “three-level zoning of upper, middle, and lower reaches” in the Aral Sea Basin [47] focuses on water resource allocation, while the zoning in the Lake Urmia Basin [48] indirectly incorporates salinization into the drought index. Neither of these approaches can accurately identify degradation areas dominated by salinization. In contrast, this study achieves precise matching between “stressor types and governance needs” through the “independent salinization indicator + refined secondary zoning”, providing a new paradigm for ecological zoning in arid and high-salinity-alkalinity basins.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the Ebinur Lake Basin, constructing a comprehensive zoning index by integrating ecosystem function importance and sensitivity evaluations. It provides critical technical support for the basin’s integrated ecological management, with the innovative inclusion of salinization sensitivity in the evaluation system—enhancing the alignment of zoning results with local realities and offering a transferable paradigm for global high-evaporation, high-salinity basins (e.g., the Aral Sea, Great Salt Lake). This methodological contribution highlights that ecological zoning requires in-depth analysis of regional dominant ecological processes rather than mechanical application of universal indicators, aiding local policymakers in formulating governance strategies.

As a typical representative of arid inland river basins, the zoning method developed for the Ebinur Lake Basin exhibits excellent transferability potential to regions with similar climatic and geomorphological conditions (e.g., arid areas in Central Asia). Firstly, prioritize dominant stressors: assign independent weights to core ecological issues in arid basins (such as salinization and desertification) within the indicator system to avoid the one-sidedness of general frameworks. Secondly, refine zoning based on multi-scale differences: clarify macro functional positioning through primary zoning and identify micro-scale stressor variations via secondary zoning, thereby improving governance precision. Thirdly, adopt lightweight data adaptation: leverage universal data sources such as Google Earth Engine (GEE) and the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD) to lower data acquisition barriers. This study can directly guide ecological zoning in similar global basins, including the Aral Sea in Central Asia, the Great Salt Lake in the United States, and Lake Eyre in Australia. It provides a complete operational paradigm of “indicator selection—weight calibration—zoning delineation” for the transformation of global arid region ecological governance from “local restoration” to “systematic governance”, contributing to the sustainable management of arid ecosystems. For instance, when applied in humid areas or alpine regions, sensitivity indicators should be adjusted according to local dominant ecological issues, such as adding flood sensitivity and freeze–thaw erosion sensitivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; methodology, L.X.; investigation, J.Z. and Z.Q.; resources, L.W.; data curation, J.Z.; project administration, Y.F.; funding acquisition, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, grant number 2024B03025.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the datasets provided by the Geospatial Data Cloud, Google Earth Engine platform, Resource and Environmental Science Data Center, and the Harmonized World Soil Database. The authors also sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, J.; Zeng, H.; Ma, L.; Bai, R. Recent Changes of Selected Lake Water Resources in Arid Xinjiang, Northwestern China. Quat. Sci. 2012, 32, 142−150. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Ding, J.; Li, G.; Liang, J.; Yu, D.; Aishan, T.; Zhang, F.; Yang, J.; Abulimiti, A.; Liu, J. Dynamic Detection of Water Surface Area of Ebinur Lake Using Multi-Source Satellite Data (Landsat and Sentinel-1A) and Its Responses to Changing Environment. CATENA 2019, 177, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.G.; Qin, C.B.; Yu, L.; Lu, L.; Guan, Y.; Wan, J.; Li, X. Methods to identify the boundary of ecological space based on ecosystem service functions and ecological sensitivity: A case study of Nanning City. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 7899−7911. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.Y.; Zhao, X.M.; Guo, X.; Jiang, Y.F.; Lai, X.H. The natural ecological spatial management zoning based on ecosystem service function and ecological sensitivity. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 1065−1076. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Yang, C.J. Sensitivity analysis of ecological environment in Dongchuan district based on GIS. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2022, 3, 7−12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhang, H.H. Ecological sensitivity of Bayingolin Mongolian Autonomous Prefecture of Xinjiang. Arid Land Geogr. 2015, 38, 1226−1233. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z.H.; Ma, Y.J.; Jia, Y.P. Integrated assessment on ecological sensitivity for Taiyuan City. Ecol. Sci. 2018, 37, 204−210. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.Q.; Shi, X.Q.; Li, Y.H.; Li, Y.M.; Huang, P. Spatio-temporal pattern and functional zoning of ecosystem services in the karst mountainous areas of southeastern Yunnan. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 736−756. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.P.; Yin, L.; Wang, X.Y. Assessment of the ecological environment sensitivity of Chishui based on GIS. Environ. Ecol. 2023, 5, 10−18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S.; Wei, L.; Xiao, L.; Zheng, X.Z.; Yin, Z.Y. Ecological Sensitivity Evaluation of County Based on GIS:Take Dongyuan County of Heyuan City as An Example. For. Environ. Sci. 2022, 38, 63−73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z.H.; Li, X.F. GIS-based Ecological Sensitivity Analysis of Sponge City Planning Area. Land Resour. Her. 2017, 14, 49−52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Tang, C.; Fu, B.; Lü, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, J. Determining Critical Thresholds of Ecological Restoration Based on Ecosystem Service Index: A Case Study in the Pingjiang Catchment in Southern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, R.; Balmford, A.; Costanza, R.; Fisher, B.; Green, R.E.; Lehner, B.; Malcolm, T.R.; Ricketts, T.H. Global Mapping of Ecosystem Services and Conservation Priorities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9495–9500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J. Landscape Sustainability Science: Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being in Changing Landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnesoeur, V.; Locatelli, B.; Guariguata, M.R.; Ochoa-Tocachi, B.F.; Vanacker, V.; Mao, Z.; Stokes, A.; Mathez-Stiefel, S.-L. Impacts of Forests and Forestation on Hydrological Services in the Andes: A Systematic Review. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 433, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, P.D.; Liu, M.; Xu, K.R.; Zhang, N.; Jiang, P.; Wang, W.J.; Jiang, Y.G. Spatial pattern of water conservation function and ecological management suggestions in the catchment area of the upper reaches of Qinhe River in the Yellow River Basin from 1990 to 2020. Geol. China 2024, 51, 1917−1929. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.; Li, X.; Xiao, R.; Wang, Y. Effects of Land Use Transition on Ecological Vulnerability in Poverty-Stricken Mountainous Areas of China: A Complex Network Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Li, Z.; Liang, Y. Tempo-Spatial Changes of Ecological Vulnerability in the Arid Area Based on Ordered Weighted Average Model. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yuan, R.; Singh, V.P.; Xu, C.-Y.; Fan, K.; Shen, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J. Dynamic Vulnerability of Ecological Systems to Climate Changes across the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 134, 108483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, S.; Dong, J.; Liu, Y.; Meersmans, J.; Li, H.; Wu, J. Applying ant colony algorithm to identify ecological security patterns in megacities. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 117, 214−222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Z. Evaluation of Ecological Sensitivity in Suihua City. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y. Study on the Zoning and Countermeasures of Ecological Protection and Restoration of Mountains, Rivers, Forests, Farmlands, Lakes and Grasses in Zoige County. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu University of Technology, Chengdu, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, C.; Luo, W.Q.; Chen, Y.Q.; Wu, Z.Y.; Hu, Z.X.; Liu, S.H.; Ma, Q.; Qin, L.T. Zoning management of karst landscape resources in Guilin based on ecosystem sensitivity and service function. Geol. China 2024, 51, 1839–1854. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Li, W.M.; Han, H.H.; Chen, X.Y.; Li, J.Q. Evaluation of the importance of ecological protection in the source area of the Yellow River for ecological function regionalization. Geol. China 2025, 1−18. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1167.P.20250303.1737.007 (accessed on 2 January 2026). (In Chinese).

- Wang, S.Y.; Zhao, M.M.; Diao, Y.J.; Ma, X.; Fu, L.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, T.; Chen, G.; Guo, P. Application and evaluation method of the importance of ecological protection in Changdu City of the east Qinghai−Xizang Plateau. Geol. China 2025, 52, 264−277. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bao, A.; Yu, T.; Xu, W.; Lei, J.; Jiapaer, G.; Chen, X.; Komiljon, T.; Khabibullo, S.; Sagidullaevich, X.B.; Kamalatdin, I. Ecological Problems and Ecological Restoration Zoning of the Aral Sea. J. Arid Land 2024, 16, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardavan, Z.; Roya, M.; Majid, R. Assessment of the Hazards of Vegetation Loss in the Eastern Basin of the Lake Urmia Based on the Ecosystem Services Modeling Approach Under the Conceptual Framework of DPSIR. Environ. Res. 2023, 14, 219–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, D.; Peng, S.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Reduced Soil Ecosystem Multifunctionality Is Associated with Altered Complexity of the Bacterial-Fungal Interkingdom Network under Salinization Pressure. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chele, K.; Tinte, M.; Piater, L.; Dubery, I.; Tugizimana, F. Soil Salinity, a Serious Environmental Issue and Plant Responses: A Metabolomics Perspective. Metabolites 2021, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Yuan, J.; Song, Y.; Ren, J.; Qi, J.; Zhu, M.; Feng, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; et al. Elevated Salinity Decreases Microbial Communities Complexity and Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Metabolism in the Songnen Plain Wetlands of China. Water Res. 2025, 276, 123285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H. Spatialandtemporalmulti-Scaleremotesensing Modeling of Soil Salinization in the Ebinur Lake Basin, Xinjiang. Ph.D. Thesis, Xinjiang University, Urumqi, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.N.; Ding, J.L.; Zhang, Z.H. Soil Salinization Mining in Xinjiang Based on Vegetation Phenology. Soil 2022, 54, 629−636. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Doulaiti, X.; Kasim, A.; Reheman, R.; Liang, H.W. Water Body Extraction of Ebinur Lake Based on Four Water Indexes and Analysis of Spatial-Temporal Changes. J. Chang. River Sci. Res. Inst. 2022, 39, 134−140. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, F.; Kung, H.; Johnson, V.C.; Bane, C.S.; Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of Land Cover and Landscape Change Patterns in Ebinur Lake Wetland National Nature Reserve, China from 1972 to 2013. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 25, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.Q. Spatiotemporal change and driving force of vegetation in Ebinur Lake Basin. Arid Land Geogr. 2022, 45, 467−477. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Ding, J.L.; Wang, J.Z.; Wang, F. Quantitative Estimation and Mapping of Soil Salinity in the Ebinur Lake Wetland Based on Vis-NIR Reflectance and Landsat 8 OLI Data. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2019, 56, 320−330. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Kung, H.; Johnson, V.C. Assessment of Land-Cover/Land-Use Change and Landscape Patterns in the Two National Nature Reserves of Ebinur Lake Watershed, Xinjiang, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.Z.; Su, W.C.; Gou, R.; Huang, F.X. Integrated evaluation of ecological sensitivity and its spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of karst mountainous cities. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 32, 276−285. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Lou, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Li, C.; Zhang, F. Impact of Lake Water Level Decline on River Evolution in Ebinur Lake Basin (an Ungauged Terminal Lake Basin). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 104, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.; Qi, Z.; Feng, Y.; Cao, X.; Cui, M.; Zou, J.; Feng, S. Construction of a Desertification Composite Index and Its Application in the Spatiotemporal Analysis of Land Desertification in the Ring-Tarim Basin over 30 Years. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Ren, T.; Li, Y.H. Ecological sensitivity analysis in typical Loess Plateau Gully Region: A case study of Qingyang, Gansu. J. Desert Res. 2025, 45, 1−10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.Q.; Luo, F.J.; Li, J.; Liu, G.Q.; Liu, C.H.; Ai, N. Spatial autocorrelation between ecological sensitivity and landscape pattern in the Yanhe River Basin. Arid Zone Res. 2025, 42, 1742−1752. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yan, T.L.; Wang, C.W.; Chen, M.X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, W.J. Implementation of ecological product value zoning based on land ecological sensitivity assessment: Using Altay City as an example. Arid Land Geogr. 2024, 47, 612−621. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.; Tiyip, T.; Xia, X.; Yahui, F.; Fei, Z.; Sawut, M. Assessment of Soil Salinization Sensitivity for Different Types of Land Use in the Ebinur Lake Region in Xinjiang. Prog. Geogr. 2011, 30, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zeng, C.; Fan, C.; Bi, H.; Gong, E.; Liu, X. Landslide susceptibility assessment based on K-means cluster information model in Wenchuan and two neighboring counties, China. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard Control 2021, 32, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.M.; Li, R.J.; Yan, X.S.; Wu, F.F.; Gao, Z.B.; Tan, Y.Z. The ecological function zoning of Qinghai Lake Basin based on ecological risk assessment. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2023, 32, 1185−1195. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.L.; Chen, X.; Qian, J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, J.; Xing, X.; Yimamaidi, D.; Zhakan, Z.; Sun, J.; Wei, S. Spatiotemporal Changes, Trade-Offs, and Synergistic Relationships in Ecosystem Services Provided by the Aral Sea Basin. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbakhsh, M.; Esmaeily, A.; Pour, A.B. Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics in Urmia Lake Basin of Iran: A Bi-Directional Approach Using Optical and Radar Data on the Google Earth Engine Platform. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 75, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Ma, J.Y.; Jin, H.L. Research on Ecological Environment Governance in the Core Area of the Ebinur Lake Basin. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 1, 63−65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.T.; Jin, J. Aibi Lake Vally Ecology Environment Dividing Area Recoverying Research. Environ. Prot. Xinjiang 2006, 2, 35−38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.