Abstract

Against the backdrop of rising farm household incomes alongside a widening internal income gap in rural China, investigating the impact of peer effects in ecological assistance (PEEA) on farmers’ policy satisfaction is crucial for formulating more targeted support policies and mitigating rural income inequality. Utilizing 2023 survey data from designated assistance counties of the National Forestry and Grassland Administration (NFGA) of China, this study employs methods such as Oprobit and moderation effects to examine the factors and mechanisms through which peer effects in ecological assistance affect farmers’ policy satisfaction. The results indicate that PEEA exert a negative influence on farmers’ policy satisfaction, a finding that remains robust after endogeneity checks using the conditional mixed process (CMP) model and residual analysis. The information transmission mechanism can strengthen the suppressive effect of these peer effects on satisfaction, whereas the social interaction mechanism exhibits a substitution effect with the peer effects. The peer effects are asymmetric, with a more pronounced negative impact on policy satisfaction among farmers over 50 years old and those with lower human capital. Furthermore, the peer effect is most significant for forestry property income, followed by forestry wage income and forestry operating income. Farmer groups with low-to-medium forestry income are more significantly affected by PEEA. Furthermore, among these, the medium forestry income cohort demonstrates the highest sensitivity to the influence of PEEA on policy satisfaction. Therefore, ecological assistance policies should be further optimized, and forestry income should be distributed equitably to enhance the sense of policy benefit and well-being among farmers. Meanwhile, information channels should be improved to guide rational interpersonal expenditure, target groups with strong peer demonstration effects, explore diversified forestry management projects, and broaden income-increasing channels through ecological assistance.

1. Introduction

Effectively managing the intricate interplay between environmental protection and livelihood improvement has become a central challenge for the global Sustainable Development Goals, particularly in rural areas of developing countries [1,2]. Mexico’s Forest Hydrological Services Compensation Program, which provides financial compensation to rural communities and farmers for protecting critical hydrological zones, Costa Rica’s Compensation Program for Environmental Services delivers payments by recognizing and rewarding landowners for their ecological conservation practices. The Novella Project in Ghana and Tanzania clearly designates specific land parcels to incentivize farmers to cultivate economically valuable tree species.

As the world’s largest developing country, China has pioneered the implementation of large-scale ecological assistance policies (e.g., Grain for Green, eco-compensation), which aim to synergistically promote ecological restoration and income growth through transformations in land use practices. Specifically, as a crucial measure for preventing a return to poverty in the post-decisive victory against poverty transition period, ecological assistance policies are a key component of China’s rural revitalization and common prosperity goals. These policies, led by the Chinese government, organically integrate ecological conservation with targeted support. They emphasize, within a sustainable development framework, the leveraging of local, land-based ecological resource endowments, such as forest land and water resources. Systematically, through various green development instruments, including ecological compensation, ecological engineering, and ecological industries, they continually increase the incomes of households lifted out of poverty while improving or protecting the ecological environment, thereby achieving sustainable land use (see Appendix A for details). Although the ecological and economic effectiveness of these practices has been extensively validated [3,4,5], a critical social dimension—farmers’ policy satisfaction—remains relatively understudied, despite being a key indicator of policy legitimacy and long-term sustainability.

Policy satisfaction serves not only as a key metric for evaluating policy success [6] but also as a core factor influencing policy sustainability and farmers’ willingness to participate [7]. A high level of satisfaction can foster farmers’ long-term support for a policy and reduce implementation costs [8]. Conversely, low satisfaction may lead to policy failure. Existing research on farmers’ policy satisfaction has primarily focused on direct individual factors. In Europe, perceived fairness and policy transparency are key measures to enhance farmers’ participation in and support for ecological compensation policies, thereby promoting a sense of social equity [9]. Satisfaction with grassland ecological compensation policies. Those who place greater importance on livelihood income and ecological quality—demonstrating higher rationality as “eco-economic men”—tend to have higher policy satisfaction [10,11]. Similarly, comparative research on agricultural and environmental subsidies in developed countries like the United States shows that policies are more likely to gain sustained support from farmers and the public when they aim to increase farm income while also addressing public goals such as environmental protection [12,13]. In contrast, in India, Africa, and other developing countries, poverty and economic vulnerability have been identified as significant constraints influencing policy satisfaction and support; groups with lower incomes and a stronger subjective sense of poverty are more concerned that policies may increase their burdens, thus exhibiting lower support or higher dissatisfaction [14,15]. Compared to the influence of livelihood capital, farmers’ value perceptions of a policy’s reasonableness, efficiency, fairness, and benefits have a greater impact on their policy satisfaction [16]. Furthermore, some scholars, distinguishing between pre- and post-policy implementation, propose that farmers’ demand perception, process perception, and service perception all positively influence policy satisfaction, with service perception having the strongest effect [17]. It can be observed that existing studies have overlooked the profound influence of the social networks in which farmers are embedded. There is a lack of analysis from the perspective of social interaction regarding the factors and mechanisms affecting farmers’ satisfaction with ecological assistance policies.

In fact, to gain a deep understanding of the formation mechanism of farmers’ policy satisfaction, it is essential to situate it within the specific context of current socio-economic development in rural China. A particularly critical trend is that, with the deepening implementation of assistance policies, the income gap within rural China has been gradually widening, even showing a tendency to surpass that in urban areas, while the income distribution structure has become increasingly complex [18,19,20]. According to calculations based on data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the income gap between the bottom 20% and the top 20% in terms of average annual per capita disposable income in rural areas reached 1:9.17 in 2022, highlighting a striking internal income imbalance. This income differentiation implies that even under the same inclusive policy, significant variations may exist in the actual benefits farmers receive and their perceptions, due to differences in their resource endowments and social capital. Excessively high income disparities can induce a sense of relative deprivation among farmers, leading to a decline in their satisfaction due to perceived unfairness, which further impedes the effectiveness of policy implementation and exacerbates social conflicts [21,22]. Simultaneously, farmers are not isolated individuals; their behaviors and decisions are profoundly influenced by other members within their social networks. In China’s village-based acquaintance society, shaped by the differential mode of association centered on kinship and locality, farmers tend to acquire decision-making information from their own social networks to minimize losses caused by information asymmetry. Consequently, their individual behaviors and decisions converge with those of their proximate groups, manifesting as a peer effect.

According to behavioral economics theory, peer effects posit that within a group sharing similar preferences or characteristics and under certain constraints, an individual’s behavioral decisions are influenced by social interactions within the group [23]. The concept can be traced back to the “Relative Income Hypothesis” proposed by Duesenberry, which indicates that the “demonstration effect” driven by external habits is a significant factor in the formation of peer effects. The psychology of keeping up with or imitating other consumers, along with the consumption patterns of one’s social stratum, not only influences individual behavioral decisions but also generates a social multiplier effect, impacting social behavior and decision-making psychology [24,25]. This implies that farmers’ satisfaction with ecological assistance policies likely stems not only from an assessment of the objective benefits delivered by the policy itself but is also significantly influenced by factors such as the degree of benefit received by other farmers in the same village and relative disparities. Although peer effects have been extensively studied in areas such as new technology adoption [26], climate change response [27], and the use of digital inclusive finance [28], research that introduces this concept into the evaluation of ecological assistance policies and systematically investigates its impact mechanism on farmers’ policy satisfaction remains scarce.

Therefore, based on 2023 survey data from households lifted out of poverty in designated assistance counties of China’s NFGA, this study incorporates peer effects into the theoretical framework for analyzing farmers’ satisfaction with ecological assistance policies. Furthermore, it constructs a theoretical model of the impact mechanism of ecological assistance on farmers’ policy satisfaction from the perspective of peer effects, grounded in the dual moderating mechanisms of information transmission and social interaction. Specifically, by analyzing the specific impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction, it seeks to reveal the key variables through which PEEA influences farmers’ policy satisfaction. Simultaneously, it investigates the heterogeneous effects of PEEA among farmers with different resource endowments and refines the analysis by examining the impacts of peer effects related to specific types of forestry income, which represent different ecological assistance policy instruments on farmers’ policy satisfaction.

Based on this, the marginal contributions of this study are as follows: First, it breaks through the limitation of existing literature that focuses on individual characteristics by innovatively introducing a peer effects perspective. It places ecological assistance policies within the realistic context of a widening rural internal income gap and the relative deprivation among groups that shapes farmers’ policy satisfaction, systematically examines the impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction, and provides a new analytical framework for understanding the socio-economic consequences of policies. Second, it meticulously delineates the transmission pathways of PEEA, conducting an in-depth analysis and empirical testing of its mechanism affecting farmers’ policy satisfaction. This provides a more specific micro-level mechanistic explanation for understanding the evaluation motivations and behavioral decisions underlying farmers’ policy satisfaction. Third, it reveals the asymmetric impact of PEEA on different farmer groups, clarifies the boundary conditions under which it functions, and provides a theoretical basis and policy implications for formulating and optimizing more targeted ecological assistance measures in the future.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Impact of PEEA on Farmers’ Policy Satisfaction

Peer effect theory suggests that an individual’s behavioral decisions are influenced by the social network relationships of their group. The structural familiarity and differential mode of association in Chinese rural society result in group classifications and social ties among village households based on kinship, geographical proximity, and even production relations. Consequently, when making independent decisions to mitigate potential losses under conditions of high external environmental risk and information asymmetry, farmers tend to emulate the behavioral choices of their village peers, demonstrating group conformity [29].

Specifically, on one hand, social learning theory argues that in uncertain decision-making contexts, individuals form expectations and guide their own actions by observing the behaviors and outcomes of others [30]. Owing to the technical complexity and delayed effects of ecological assistance policies, farmers frequently rely on observing and imitating fellow villagers’ behaviors when evaluating such policies, which constitutes a low-cost and highly credible mode of learning. If farmers witness instances of biased or unfair policy outcomes, it generates negative signals that adversely affect their own satisfaction judgments.

On the other hand, social comparison serves as a critical pathway through which relative deprivation emerges within peer effects [31]. Farmers’ evaluations of policies are determined not merely by their absolute gains but, more significantly, by comparisons with their reference group. While ecological assistance policies may boost income for some farmers, they can simultaneously exacerbate income disparities among households [32,33]. Furthermore, insufficient long-term policy stability poses risks of livelihood transformation and income reduction for certain farmers [34]. If farmers perceive their benefits to be inferior to those of their peers, even when absolute income has improved, intense feelings of relative deprivation will diminish their policy satisfaction.

Meanwhile, from the perspective of social norms theory, group identity is deeply rooted in the reality of China’s rural acquaintance society. Through daily interactions, farmers develop a strong sense of group identity and moral pressure, which fosters a social behavioral norm during policy evaluation, thereby influencing the satisfaction appraisal of every household within the village peer group. In short, farmers’ policy satisfaction is influenced not only by their individual characteristics but also significantly by the evaluations of other villagers in the same community.

2.2. The Moderating Effect of PEEA on Farmers’ Policy Satisfaction

2.2.1. Information Transmission Mechanism

The information transmission mechanism of peer effects refers to the influence of information resources contained within an individual’s group network on their behavior and decision-making [28,35]. From the perspective of social learning, constrained by information asymmetry and group identity pressure, and driven by risk minimization, farmers observe and learn from the behavioral decisions of other farmers around them to guide and adjust their own evaluations and perceptions of policies. On one hand, with the gradual penetration of digital technologies in rural areas, farmers no longer rely solely on traditional, limited face-to-face communication to gather information about other households in the same village. Instead, they are turning to more convenient and faster internet platforms to access a wider range of policy-related information. On the other hand, information technology has reduced the cost of searching for information, facilitating more frequent information exchange among villagers. This enables potential issues arising from policy implementation to spread rapidly within the community. Furthermore, underpinned by kinship and geographical ties, the policy satisfaction evaluations among villagers act as an “amplifier,” thereby intensifying the impact of the peer effect.

2.2.2. Social Interaction Mechanism

Within the social networks of rural China, social interactions grounded in kinship, geographical proximity, and even production relations compel farmers to consider the behaviors and decisions of their peers when making their own choices. This fosters a paradigm of social interaction centered on reciprocal exchanges of favors among households, thereby establishing a foundation within a customary society for the formation and reinforcement of the peer effect. On one hand, social interaction can generate a sense of group identity and group pressure. Furthermore, in traditional villages where clans sharing the same surname are predominant, clan culture often engenders strong internal social norms, resulting in non-mandatory social pressure and lineage-based initiatives [36]. These factors amplify the peer effect in the policy satisfaction evaluations of farmers within the same village. On the other hand, social interaction acts as an emotional bond within informal institutions that sustains relationships among farmers. When formal channels for policy information are opaque or dysfunctional, intensive social interaction itself can constitute an alternative system for information gathering and judgment. Farmers may consequently rely on the experiences of acquaintances gleaned from this network to formulate their policy evaluations. In such contexts, social interaction may functionally assume a substitutive role. Hence, social interaction can act both as an amplifier of the peer effect and, under specific circumstances, as an alternative channel for it.

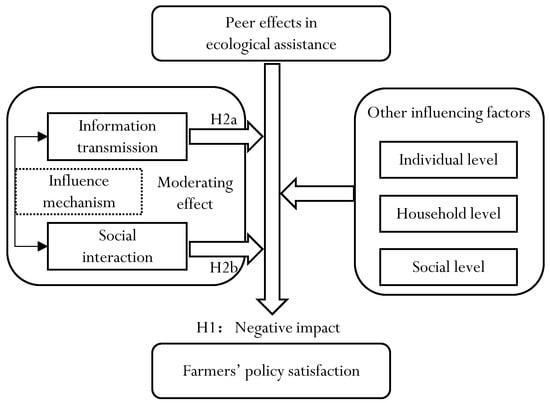

Therefore, this study proposes the following research hypotheses and constructs a theoretical analytical framework (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Theoretical analysis framework.

H1.

PEEA have a negative impact on farmers’ policy satisfaction.

H2a.

The information transmission mechanism plays a moderating role in the influence of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction.

H2b.

The social interaction mechanism plays a moderating role in the influence of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source

3.1.1. Study Area

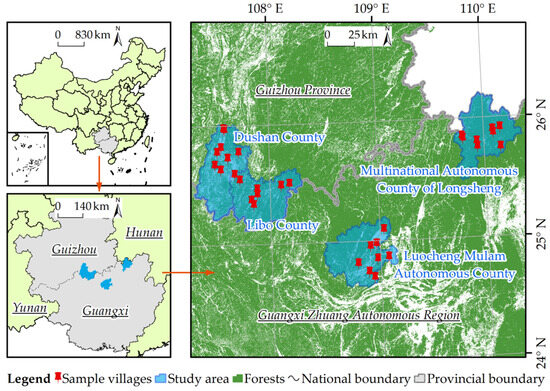

The data used in this study are derived from field surveys conducted by the research team in 2023. These surveys targeted households that had been lifted out of poverty in four counties designated for assistance by the NFGA of China: Longsheng, Luocheng, Libo, and Dushan. As shown in Figure 21, these four counties are located in ecologically vulnerable areas of Southern China and are home to numerous ethnic minority groups. The area is predominantly characterized by karst landforms, ranking among China’s most severe cases of soil erosion. The high degree of overlap between ecological vulnerability and poverty vulnerability, exacerbated by the fragile environment and adverse topographic conditions, has significantly shaped the local poverty landscape [37,38]. Furthermore, since the late 1990s, this region has been a priority area for implementing ecological assistance policies, with Guangxi and Guizhou provinces demonstrating the most notable outcomes [39]. Over the past few years, with targeted support from the NFGA, these four counties have actively leveraged forestry ecological assistance policies to promote a structural transformation of regional land use patterns. Through measures such as grain for green, developing ecotourism, and fostering understory economies, they have revitalized land resources, achieved multifunctional land use. Among these achievements, Longsheng County was designated a national “Lucid Waters and Lush Mountains Are Invaluable Assets” practice and innovation base; Luocheng County gained recognition as one of China’s climate-livable counties; Libo County was honored as a Forest City in Guizhou Province; and Dushan County was approved as a pilot unit for the “National Forest Wellness Base Construction” initiative. Collectively, these four counties have established a relatively mature forestry ecological assistance system grounded in sustainable land management. They serve as representative areas for researching ecological assistance policies and constitute critical case studies for understanding the implementation effects of such policies.

Figure 2.

Sample location map.

3.1.2. Data Sampling Process

Since the target beneficiaries of the ecological assistance policies are households that have been lifted out of poverty, the research team employed a stratified random sampling method based on the official monitoring lists of such households provided by the four county governments. This approach ensured that all survey respondents were indeed beneficiaries of the policies and represented a range of economic conditions and livelihood strategies. Following the monitoring lists, the team randomly selected 4 townships (or sub-districts) within each county. Subsequently, 2 to 3 villages were randomly chosen within each selected township, and finally, 10 to 12 households were randomly selected within each village. Furthermore, to ensure a consistent understanding of the term “ecological assistance policies” among all respondents, an operational definition was provided during the questionnaire design phase2. Investigators received centralized training before the surveys. They provided uniform and clear explanations during the interviews to standardize the conceptual communication, ensuring that respondents recalled and evaluated the policies within a specific, well-defined framework, thereby enhancing data accuracy and reliability. The survey was conducted through face-to-face, in-home interviews with the head of the household. The interview content covered basic household information, asset ownership and perceptions, policy implementation details, and subjective cognitions regarding the policies. The survey covered 16 townships (sub-districts) and 32 villages, resulting in 330 initially collected questionnaires. After post-survey screening, which removed questionnaires with critical missing data or internal inconsistencies, 326 valid questionnaires were retained, yielding a validity rate of 98.79%.

3.2. Variables and Description

3.2.1. Explained Variable

Policy satisfaction refers to farmers’ subjective evaluation of the implementation status of ecological assistance policies, reflecting their personal perceptions of how these policies are carried out. This study adopts the single global evaluation item method, consistent with the approach used in large-scale nationally representative surveys such as the China General Social Survey (CGSS) and the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). This measurement approach possesses high acceptability and comparability in the Chinese context, enabling it to effectively capture farmers’ holistic and generalized assessment of the ecological assistance policies. It demonstrates good efficiency and cost-effectiveness, representing a common and accepted methodology [40,41]. Therefore, informed by this established practice and tailored to the specific conditions of our survey, policy satisfaction is measured via farmers’ subjective evaluation of the local ecological assistance policies. This aims to effectively capture farmers’ policy perceptions at an aggregate level. The specific survey question was: “Do you agree that the local ecological assistance policies have been well implemented?” Responses were coded as follows: Agree” was assigned a value of 3, “Neutral” a value of 2, and “Disagree” a value of 1.

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

The core explanatory variable in this study is the PEEA, defined as the average forestry income of other farm households within the same village, excluding the sample household itself3. Within the acquaintance society of rural China, household income serves as the most concerning, readily observable, and comparable objective indicator for farmers. The income disparity arising therefrom will trigger a sense of relative deprivation through social comparison, revealing the social learning channels for generating income from land and the pressures associated with group identity. Given that the ecological assistance efforts in the four designated counties primarily focus on forestry, forestry income has become a significant component of local farmers’ income [42]. Therefore, in measuring and evaluating the local ecological assistance, and aligning with the policy’s primary goal of expanding farmers’ income channels, forestry income, which is most closely and directly related to the households, is selected as the quantitative indicator [43].

Simultaneously, a prerequisite for identifying peer effects is the selection of an appropriate reference group. The proximity of residing in the same village fosters close social networks, meeting the conditions for a certain population size and in-group social interaction due to geographical closeness. Following the approach of Nie et al. [44] and Xu et al. [28], this study uses other households in the same village, excluding the sample household, as the reference group. The average forestry income for different households is calculated separately to measure the PEEA for each household. The specific calculation is as follows:

In Equation (1), represents the PEEA for the sample farmer in village , denotes the total number of farm households in the village , and signifies the forestry income related to ecological assistance for all other farmers in the village , excluding the sample farmer .

3.2.3. Control Variables

Drawing on the studies of Hu et al. [45], Zhou [46], and Qiu & Jin [47], and integrating the survey data, this study incorporates a series of variables into the empirical analysis at the individual, household, and social levels. Specifically, at the individual level, variables such as gender, age, education level, and health status are selected. Furthermore, a squared term of age is included to test for potential non-linear effects of age on farmers’ policy satisfaction. At the household level, controls include the number of laborers, social organization participation, per capita forestland area of the household, income level, and subjective poverty. At the social level, variables consist of the respondents’ perceptions and evaluations of social human capital, recreational facilities, and public services. Additionally, considering potential regional disparities among the farm households, regional dummy variables are employed for control purposes.

3.2.4. Moderating Variables

This study categorizes the moderating mechanisms into the information transmission mechanism and the social interaction mechanism. Among these, the information transmission mechanism selects “Internet use” as a proxy variable for farmers’ information acquisition. With the comprehensive penetration of information technology into rural areas, farmers’ evaluations of ecological assistance policies are increasingly driven and influenced by external online information. Consequently, the magnitude of peer effects is correspondingly affected by policy-related network dissemination and digital information flow. The social interaction mechanism is defined as farmers’ “interpersonal spending”. Interpersonal spending, manifested as cash gifts or the monetary equivalent of material gifts given by rural households to maintain social relationships with non-cohabiting relatives, friends, and neighbors within the same village, serves as a metric for gauging the intensity of interactions within social networks and the cost of relationship maintenance among villagers. It reflects the influence of clan culture on kinship and friendship ties, as well as the fundamental norms governing social interactions in rural settings. The more frequent the reciprocal gift-giving among village households, the more extensive their mutual information acquisition and social interaction become. Consequently, this process contributes to shaping farmers’ self-perception and understanding of the ecological assistance policies.

Since the conventional transformation Method may introduce interference information for village households with lower incomes, this study uniformly applies the inverse hyperbolic sine (HIS) transformation to variables involving monetary values, denoted as ).

Table 1 provides the detailed descriptions of all variables. The mean value of policy satisfaction is 1.83. The mean value of the PEEA is 8.83. At the individual level, the average age of the sample farmers is 51.18 years, with males comprising 78.22%. The average education level falls between primary school and junior high school. At the household level, the average number of family laborers is 2.44. Approximately 70% of the households have joined cooperatives, and the per capita forestland area is 4.66 mu. At the social level, farmers’ average ratings for human capital and recreational facilities are around 3 points, while the average rating for public services is 3.98 points, indicating that farmers’ evaluation and recognition of local public services are not particularly high.

Table 1.

Variables, definitions and descriptive statistics.

3.3. Model Setting

3.3.1. Ordered Probit Model

This study employs the ordered Probit model (Oprobit) as the baseline regression model to analyze the impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction. The model is specified as follows:

In Equation (2), denotes the policy satisfaction evaluation of the -th farmer household, is the intercept term, and are the coefficients to be estimated, represents the control variables, and signifies the random disturbance term. The relationship between the observable variable of sample farmers’ policy satisfaction, , and the unobservable latent variable, , is defined as follows:

In Equation (3), , , and represent the unknown threshold parameters (cutoff points) for policy satisfaction. The probabilities for each policy satisfaction rating are given as follows:

In Equations (4) and (5), sequentially takes values from 1 to 3, represents the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution, and the Maximum Likelihood Estimation method is employed to jointly estimate the parameters in the aforementioned equations.

3.3.2. Moderating Effect Model

Building upon the baseline regression, this study further examines the impact of PEEA on policy satisfaction by incorporating internet use and interpersonal spending as moderating variables. The specific model is specified as follows:

In Equation (6), is the intercept term, and are the coefficients to be estimated, represents the variable for information transmission and social interaction, and denotes the random disturbance term. If the coefficients to be estimated (, , ) are all statistically significant, and if both and are positive, it indicates the presence of a positive moderating effect. When is positive and is negative, it suggests a negative moderating effect. If, under this condition, coefficient is positive, it implies a distinct substitution relationship exists between the variable and the moderating variable . When both and are negative, it also indicates a positive moderating effect. If is negative and is positive, it means the moderating variable weakens the effect of on . Should coefficient B be negative in this case, it reveals a clear substitution relationship between F and the moderating variable .

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

This study employs StataMP 17 to perform the Oprobit model estimation. Regression (1) does not include control variables or regional dummy variables. Regression (2) incorporates the control variables and accounts for potential heteroskedasticity by clustering standard errors at the regional level. The detailed regression results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction.

The results in Table 2 show that in Regression (1), the coefficient for the PEEA is significantly negative, indicating a negative impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction. Results from Regression (2) reveal that PEEA continues to exert a significantly negative influence on farmers’ policy satisfaction at the 1% significance level, confirming a negative correlation between PEEA and policy satisfaction, thus supporting Hypothesis H1 proposed in this study. The results also indicate that farmers do not evaluate policies in isolation; rather, they compare their own benefits with those of their neighbors. When they perceive themselves to be at a relative disadvantage, it triggers a stronger sense of relative deprivation, consequently leading to a decline in policy satisfaction. Therefore, during the implementation of ecological assistance policies, if the social comparisons arising from disparities in resource allocation are not properly managed, the resulting negative psychological effects may offset or even surpass the absolute economic benefits provided by the policies. This can become a significant factor constraining the enhancement of the sense of benefit derived from the policies.

Regarding the control variables, the squared term of age is statistically significant at the 10% level with a positive coefficient, whereas the linear age term itself is not significant. Membership in social organizations is significant at the 1% level with a positive coefficient, indicating that joining cooperatives or other social organizations can help mitigate the socio-psychological disparity caused by forestry income gaps, thereby enhancing farmers’ subjective perception and evaluation of the policies. The coefficient for subjective poverty is significantly positive, showing a positive correlation between farmers’ self-identification with a poverty status and their policy evaluation. The variables for human capital, recreational facilities, and public services are all statistically significant and positive. This implies that improvements in local employment levels, better cultural and recreational infrastructure, and enhanced public services can significantly boost farmers’ positive cognition of the local ecological assistance policies and increase their policy satisfaction.

4.2. Moderating Effects

The baseline regression results confirm that the PEEA exert a significant negative influence on farmers’ policy satisfaction. However, what are the specific mechanisms through which this effect operates? In other words, which key variables mediate the impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction? As suggested by the prior theoretical analysis, this study posits that a plausible explanation is that PEEA influences farmers’ evaluation of policy satisfaction through the moderating mechanisms of information transmission and social interaction.

4.2.1. The Moderating Effect of Information Transmission Mechanism

The results from Regression (1) in Table 3 indicate that the interaction term between the PEEA and internet use is significantly negative at the 1% level. This demonstrates that farmers’ use of the internet can strengthen the suppressive effect of PEEA on policy satisfaction, thus validating Hypothesis H2a. A plausible explanation is that internet use expands farmers’ social networks and mitigates information barriers caused by geographical isolation and distance. Consequently, social issues such as regional income disparities and class differentiation, which foster a sense of relative deprivation, are made more visible to farmers through the information disseminated online. This, in turn, intensifies the negative impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction.

Table 3.

The moderating effect of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction.

4.2.2. The Moderating Effect of Social Interaction Mechanism

As shown in the results of Regression (2) in Table 3, the interaction term between the PEEA and interpersonal spending exhibits a significantly negative regression coefficient. The coefficient for interpersonal spending itself is also negative, and both are statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates the existence of a substitution effect between PEEA and interpersonal spending in influencing farmers’ satisfaction. Specifically, when the PEEA is relatively weak, interpersonal spending within the same village makes farmers’ perception of the income gap more pronounced, thereby negatively impacting their policy satisfaction. Thus, Hypothesis H2b is supported. A plausible explanation is that, influenced by clan ethics and nepotism, interpersonal spending in rural society serves multiple social interactive functions, such as emotional communication and mutual assistance. When the PEEA is strong, the role of interpersonal spending diminishes relatively, and farmers are more inclined to obtain opinions and evaluations about the policy from other villagers through more formal channels. However, when the PEEA is weak, interpersonal spending becomes the primary means by which farmers learn about the benefits other villagers have gained from the implementation of the ecological assistance policy. This further deepens their perception of the income gap within the village, consequently suppressing their views and evaluations of the ecological assistance policies.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Group Heterogeneity

When individual behavioral decisions within a group influence each other, manifesting peer effects, “leaders” in behavioral decision-making may emerge within the group. The actions or decisions of these leaders exert a strong demonstration effect on other individuals in the group [48,49], resulting in the asymmetry of peer effects. Therefore, regarding farmers’ satisfaction with local ecological assistance policies, which subgroup generates a stronger peer demonstration effect? To address this question, this study categorizes farmers into different subgroups based on their age and human capital, and separately examines the peer demonstration effects on policy satisfaction among farmers with different characteristics.

In terms of age heterogeneity, the sample is divided into two groups: farmers aged 50 and below, and those over 50 years old. The regression results in Regressions (1) and (2) of Table 4 indicate that farmers over the age of 50 exhibit a stronger peer demonstration effect concerning policy satisfaction, and the coefficient is significantly negative. This suggests that the PEEA has a greater impact on the farmer group over 50, who play a “leadership” role in demonstrating how to perceive and evaluate the implementation of local assistance policies. Specifically, a larger forestry income gap among villagers leads older farmers to evaluate the ecological assistance policies more negatively, which is more likely to influence the perceptions and evaluations of younger farmers. This phenomenon may originate from the distinctive lifestyle and information acquisition patterns of older farmers. On one hand, the social networks of older farmers are more localized and stable, and their method of obtaining information relies heavily on interpersonal communication and observational learning within the village. On the other hand, when confronted with the complex and detailed information of ecological assistance policies, the cost for older farmers to independently search for, screen, and comprehend the original policy documents is relatively high. Consequently, the behaviors and evaluations of fellow villagers, particularly those in similar circumstances, become the most direct and reliable reference for them to form their own policy perceptions, thereby amplifying the effect of peer comparison.

Table 4.

Heterogeneity analysis.

Concerning human capital, farmers are classified into a higher human capital group (junior high school education and above) and a lower human capital group (primary school education and below) based on their educational attainment. The regression results in Regressions (3) and (4) of Table 4 show that PEEA has a negative impact on the policy satisfaction of farmers in the lower human capital group, and this impact is statistically significant at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively. The underlying reason may be that farmers with lower educational attainment often face higher cognitive barriers and judgment costs when processing complex information, such as policy-related knowledge. When unable to independently assess the merits of a policy based solely on their own knowledge, observing and conforming to the prevailing opinions within their village becomes an efficient decision-making strategy. This approach helps mitigate the risk of social isolation and, consequently, renders them more sensitive to shifts in peer attitudes. This implies that farmers with lower human capital are more susceptible to the negative influence of PEEA. They perceive the forestry income gap among fellow villagers more acutely, which subsequently leads to their lower satisfaction with the local policies. Therefore, in the context of a widening forestry income gap within the same village, attempting to influence the policy evaluations of the lower human capital group through the higher human capital group may be an inefficient strategy.

4.3.2. Heterogeneity of Different Forestry Income Types

To investigate which type of forestry income-enhancing measure within the ecological assistance policy has a stronger influence on farmers’ policy satisfaction through peer effects, this study disaggregates forestry income into four major categories based on source and nature: forestry operating income, forestry wage income, forestry property income, and forestry transfer income.

Specifically, forestry operating income encompasses revenue from forestry industries such as timber forests and understory economy activities. Forestry wage income primarily consists of wages from public welfare positions, like ecological forest rangers. Forestry property income includes dividends and earnings from farmers’ forestland shares in cooperatives or from land transfers. Forestry transfer income mainly derives from subsidy programs like the Grain for Green Program and ecological public welfare forest compensation.

Following Equation (1), these four types of forestry income are formulated as peer effects. The regression results in Regressions (1) to (4) of Table 5 indicate that among the four categories, the peer effect associated with forestry property income is the largest, followed by forestry operating income and wage income. This suggests that practices which liberalize forestland contract and management rights—such as large-scale collective forest management, developing the understory economy, and collective forestland transfer or shareholding in cooperatives—can significantly boost household forestry income. However, variations in the scale of forestland owned by different households and their willingness to transfer or contribute shares may lead to increased income differentiation among villagers, thereby affecting their evaluation of the ecological assistance policy’s implementation. Conversely, due to the long production cycles inherent in forestry, its short-term impact on household income is relatively limited, resulting in farmers having a weaker perception of operating income. Forestry wage income, largely reliant on small subsidies from systems like the ecological ranger program, often constitutes a small and relatively fixed portion of total forestry income due to wage rigidity. Consequently, the effect of PEEA related to forestry wage income on farmers’ policy satisfaction is comparatively minor. The peer effect associated with forestry transfer income is not significant, which may stem from its inherent linkage to specific ecological conservation actions. The eligibility criteria, subsidy standards, and distribution procedures are largely uniformly stipulated by higher-level governments based on explicit policy provisions, endowing this income stream with a high degree of standardization and predictability. This creates a relatively fixed “top-down” allocation model. This model diminishes the scope for significant comparison among farmers based on their subjective efforts or disparities in social capital, thereby weakening the psychological impetus for social comparison among them.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity of different types of forestry income.

4.3.3. Quantile Regression Based on Forestry Income

To further investigate whether the impact of PEEA varies depending on the relative position of farmers within the village economic structure, this study employs quantile regression, categorizing the sample into three subgroups based on forestry income levels at the 20th, 50th, and 80th percentiles, labeled as “Low Forestry Income,” “Medium Forestry Income,” and “High Forestry Income,” respectively. Grouped regression was then conducted. The results are presented in Table 6. In both the low and medium forestry income groups, the coefficients for PEEA are significantly negative at the 10% level, with the absolute value of the coefficient being largest in the medium forestry income group. This indicates that for the vast majority of farmers in the middle to lower echelons of the village economic hierarchy, the relative deprivation triggered by PEEA is more intense, serving as a key mechanism that suppresses their policy satisfaction. Furthermore, medium forestry income farmers appear to be the most sensitive to social comparisons, experiencing the greatest negative impact on their satisfaction from peer effects. In contrast, the coefficient for PEEA in the high forestry income group is positive but statistically insignificant. A plausible explanation is that, as the top earners from forestry within the village, this group has likely benefited substantially from the policies already and possesses greater social capital and alternative information channels. Consequently, their satisfaction evaluations are formed more independently and are less subject to relative comparisons with their neighbors.

Table 6.

Forestry income quantile regression.

4.4. Endogeneity Tests

By explaining the impact on farmers’ policy satisfaction through the village-level PEEA, this study mitigates, to a certain extent, the endogeneity bias caused by reverse causality. However, potential endogeneity issues, such as omitted variables and measurement errors, may persist, potentially leading to biased regression results. Therefore, this study employs the CMP method to obtain corrected estimates for the Oprobit model. Following the approach of Copiello, Maturana & Nickerson [50,51], the proportion of non-agricultural employment among villagers is selected as the instrumental variable. On one hand, this proportion reflects the allocation of agricultural labor resources and the structure of income among village households. As forestry constitutes a significant component of local agricultural income, a higher proportion of non-agricultural employment indicates a greater shift in labor from forestry to secondary and tertiary industries. This directly affects the share of forestry income in total household earnings, thereby establishing a close correlation with PEEA, which satisfies the relevance requirement for an instrumental variable. On the other hand, this proportion merely reflects the employment structure and trends within the village; it does not directly influence individual farmers’ policy satisfaction. The non-agricultural employment ratio primarily influences households’ economic activities and income distribution. In contrast, policy satisfaction is predominantly determined by the perceived effectiveness and personal understanding of the policy implementation. Since the employment ratio does not directly shape farmers’ subjective perceptions and evaluations of the ecological assistance policies, the exogeneity condition is satisfied.

Table 7 presents the CMP estimation results. Regressions (1) and (2) show the two-stage estimation results for policy satisfaction. It can be observed that the coefficients in both stages of the policy satisfaction estimation are statistically significant. The model passes the Wald test, and the parameter lnsig_2 is significantly positive. Furthermore, Regression (2) passes the atanhrho_12 test, providing additional evidence that using the CMP method in the above model helps mitigate regression bias. The results show that after instrumenting, the impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction remains significantly negative. This finding is consistent with the baseline regression results in terms of both the sign and significance of the coefficient, indicating the robustness of the result and providing further validation for Hypothesis H1.

Table 7.

Endogeneity tests.

4.5. Robustness Tests

4.5.1. Validity Test

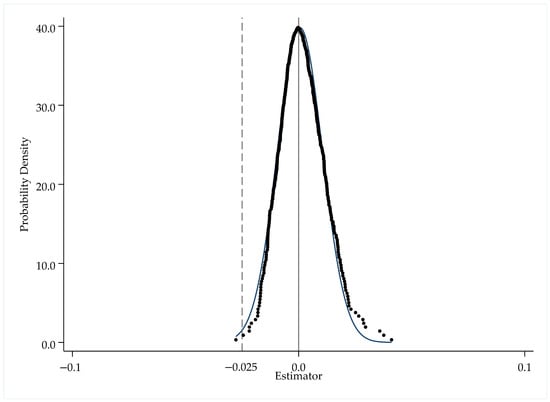

Although the baseline regression has controlled for individual, household, and social characteristics of the farmers, with clustering at the regional level, there may still be unobserved variables that are difficult to account for in the model. Therefore, following the approach of Ferrara & Chong [52] and Zhang & Luo [53], a placebo test is conducted by constructing the estimated coefficients for the PEEA. To enhance the accuracy of the placebo test, 500 random sampling iterations are performed. The model specification in Figure 3 corresponds to Regression (2) in Table 2. It can be observed that the coefficients from the placebo test for policy satisfaction approximately follow a normal distribution, with a mean close to zero and statistical insignificance, indicating that the pseudo-intervention does not affect the estimation of the policy satisfaction variable. The estimates from the random assignments are concentrated around zero (with a standard deviation of −0.025). Furthermore, when comparing the placebo test coefficients with those from Regression (2) in Table 2, the values from the placebo test all lie outside the distribution of the “pseudo-treatment group” coefficients and are far from the true baseline estimate. Thus, the placebo test once again demonstrates the validity of identifying the impact of PEEA on policy satisfaction and the robustness of the regression estimation results.

Figure 3.

Benchmark regression stochastic simulation results of policy satisfaction. Note: The black dots in the figure represent randomly generated estimators, the dashed line indicates the true value from the baseline regression estimation mentioned earlier, and the solid line shows that the randomly generated estimators approximately follow a normal distribution.

4.5.2. Robustness Test of Variables and Model Replacement

To ensure the robustness of the aforementioned test results, this study employs three methods for robustness testing: replacing the explained variable, replacing the explanatory variable, and replacing the estimation model (see Table 8). First, the explained variable is replaced. This study selects the survey item “Do you agree that the local social, political, and economic environment is sound? (1 = Disagree, 2 = Neutral, 3 = Agree)” as an alternative measure for farmers’ policy satisfaction. This item measures farmers’ evaluation of the overall governance performance of the local ecological assistance policies from a broader perspective of perceived governance outcomes, which is conceptually highly consistent with policy satisfaction. The results from Specification (1) in Table 8 show that the impact of PEEA remains statistically significant and consistent in direction. Second, the explanatory variable is replaced. The original core explanatory variable is substituted with the average evaluation score from other villagers in the same community regarding the extent of benefits their households received from the ecological assistance policies. Farmers not only observe the income changes in their neighbors but also pay attention to and internalize the signals conveyed by their peers’ subjective evaluations of policy benefits. This variable reflects the assessment of policy utility by farmers under the influence of peer effects related to non-income social comparisons. The regression results in Specification (2) of Table 4 indicate that the coefficient for the peer effect variable (“average peer benefit evaluation”) is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. Finally, the model is replaced. The original model is substituted with an Ordered Logit (Ologit) model. After re-estimation, the results from Specification (3) in Table 8 show that policy satisfaction remains negatively influenced by PEEA, and this effect is statistically significant at the 1% level. It can be observed that the results from all three methods demonstrate the robustness of the empirical findings in this study.

Table 8.

Results from replacing variables and model.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Negative Impact of PEEA on Farmers’ Policy Satisfaction

Diverging from previous studies that primarily assessed policy impact on farmer satisfaction from the perspective of individual factors, this study innovatively adopts a peer effect perspective. It reveals that within the context of complex social networks and interpersonal interactions, PEEA significantly reduces farmers’ policy satisfaction, a finding that also corroborates conclusions from related studies such as Albizua et al. and Hong and Chang [54,55]. Although ecological assistance policies are designed to enhance farmers’ livelihood and well-being, given that the turning point for narrowing the internal rural income gap in China has not yet been materialized [56], farmers’ policy evaluations are not merely based on the absolute benefits they receive. Instead, these evaluations are significantly influenced by the relative gains perceived through comparisons with their village peers. For farmers who do not receive equal benefits, when they observe that neighbors, whom they regard as reference points, obtain better forestry-related jobs or higher ecological compensation through these policies, even if their own income increases, they may experience a strong sense of relative deprivation due to perceived distributional inequity. This feeling, in turn, erodes their satisfaction with the policies. Furthermore, social comparison among farmers is not only concerned with the current situation but also shapes their expectations regarding policies. When farmers observe significant benefits gained by fellow villagers from the ecological assistance policies, they naturally raise their own expectations regarding the potential gains from these policies. However, due to resource constraints, disparities in individual capabilities, or deviations in policy implementation, not all farmers can achieve the same level of income increase. When the actual outcome falls short of their adjusted policy expectations, a psychological gap emerges between the heightened expectations, amplified by peer effects, and the reality of their gains. This psychological disparity leads to strong disappointment. Consequently, the peer effect implicitly sets a higher benchmark for evaluating policy satisfaction. This makes it more difficult for the average farmer to meet the ideal policy expectations, thereby depressing the level of policy satisfaction.

In fact, ecological assistance policies often involve core livelihood endowments such as land tenure, asset monetization, and ecological compensation for farmers, topics that are closely linked to the sensitive issue of income redistribution. If issues like information asymmetry, lack of policy transparency, or implementation deviations occur during the distribution process, they can lead to adverse selection and moral hazard [57], resulting in policy inefficiency [58]. This further exacerbates the gap between expectations and reality among farmers, fueling dissatisfaction. Similarly to the research in this paper, ecological assistance policies in Costa Rica and forestry projects in Vietnam also face the potential for declining policy satisfaction. Issues such as unfair payment methods and high transaction costs arising from information asymmetry, coupled with the frequent lack of genuine voluntariness in such policies, force vulnerable farmers to participate involuntarily. This engenders a strong sense of relative deprivation and makes them more prone to dissatisfaction [59,60]. Furthermore, land policy information management schemes in Costa Rica that exclude smallholder farmers and carry a tone of group discrimination lead farmers who wish to participate to rely more on social connections to seek policy benefits. This results in disorder, long-term neglect of degraded land, and accentuates negative issues such as concerns about policy fairness [61]. Therefore, when negative policy information spreads through neighborly communication, the peer effect becomes a breeding ground that consolidates and amplifies these negative perceptions. This phenomenon partly explains why farmer satisfaction at the micro-level may remain low due to expectation gaps and value perception discrepancies [62], even when certain policies demonstrate success in macro-level data. Consequently, the implementation of future ecological assistance policies must account for the influence of peer effects within grassroots social networks. Managing social expectations, promoting equitable distribution, and alleviating social comparison pressures should be integral components of policy design.

5.2. The Moderating Mechanisms of Information Transmission and Social Interaction

Another key finding of this study is that the moderating effects of the information transmission mechanism and the social interaction mechanism on farmers’ policy satisfaction exhibit significant differences, and each follows a distinct influential pathway.

The information transmission mechanism can significantly amplify the inhibitory effect of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction. The amplification effect of information transmission primarily stems from the accelerated speed and depth of information diffusion via Internet technology. This enables farmers to more quickly and broadly access information about the benefits that villagers or neighboring groups gain from participating in ecological assistance policies, thereby intensifying the sense of relative deprivation arising from horizontal social comparisons among farmers. Internet platforms not only broaden the information sources for farmers but also amplify the perception of minor inequities in policy implementation, significantly heightening individuals’ sensitivity to distributional fairness [63]. Ecological assistance policies involve complex and specialized information, such as forestland transfer and economic subsidies. When official channels fail to effectively meet farmers’ information needs, they turn to quicker alternative channels to obtain policy-related information. Simultaneously, negative information, being more “newsworthy” than positive news, spreads faster and reaches a wider audience [64]. Consequently, when negative information concerning the policies, such as unfair land compensation or unequal forestland distribution, is disseminated and amplified through the information transmission mechanism, it further reinforces the negative peer effects triggered by social comparison and relative deprivation, leading to a greater decline in farmers’ policy satisfaction.

In contrast, a substitution relationship exists between the social interaction mechanism and PEEA. The social interaction mechanism, represented by interpersonal spending, serves as an informal channel for farmers to perceive income disparities, demonstrating the irreplaceable role of informal institutions in mediating policy-induced social tensions. In both Western and Eastern traditional societies, interpersonal spending is semi-public or public [65,66]. This allows farmers to directly experience the economic differences among neighbors through their gift-giving expenditures, which amplifies the impact on the economic well-being of the poor and subsequently influences their subjective judgment of the fairness of ecological assistance policies. This finding is also supported by studies from Bulte et al. and Itao & Kaneko [67,68]. In fact, within acquaintance societies, interpersonal exchanges provide an informal yet efficient channel for farmers to share information, particularly when formal information channels are limited or perceived as opaque. When farmers learn through social interactions about the support others receive, such as land resources or ecological compensation, the clear disparity in benefits creates an expectation gap and generates a sense of relative deprivation. This feeling, compounded by social identity and group pressure, further impacts their policy satisfaction. The distinct roles of these two mechanisms clarify that, within rural areas based on acquaintance societies, enhancing farmers’ satisfaction requires not only strengthening multi-channel information dissemination and promoting the positive guidance of social interactions but also placing greater emphasis on building trust and accumulating social capital to alleviate the negative emotions stemming from information asymmetry and social comparison.

5.3. Heterogeneity of the PEEA

The heterogeneity analysis in this study reveals that PEEA is asymmetric, with its intensity of impact varying significantly across different farmer groups and types of forestry income. The policy satisfaction of farmer groups over 50 years old and with lower human capital is more substantially affected by PEEA, and the scope of influence within their village peer groups is also wider. Forestry property income, forestry wage income, and forestry operating income all demonstrate significant PEEA, with the effect being the most pronounced for forestry property income.

Firstly, disparities in age and human capital shape farmers’ information-processing capabilities and their degree of reliance on peer groups. Older farmers with lower education levels often face higher cognitive barriers when encountering complex ecological assistance policy information related to land tenure changes, compensation standard calculations, and subsequent industry development. Their channels for obtaining information are also relatively limited [69,70]. Consequently, this demographic exhibits a stronger propensity to rely on highly localized social networks within their villages, composed of acquaintances, for information acquisition, judgment formation, and decision-making. In rural Chinese society, “social comparison” grounded in geographical proximity and kinship ties serves as a crucial benchmark for evaluating policy fairness and the extent of personal benefits received. Given their limited capacity to discern information, they exhibit particular sensitivity to behavioral changes and income disparities among their peer farmers. Close-range observation, facilitated by shared location and kinship, more readily triggers a strong sense of relative deprivation. This, in turn, exerts a significant negative impact on their ultimate level of satisfaction with the policies, thereby diminishing their policy satisfaction.

Secondly, the variation in peer effects across different types of forestry income reflects the degree of farmers’ dependence on resources and the intensity of benefits derived from specific policy instruments. The effect is strongest for forestry property income because it stems directly from the redistribution of asset attributes centered on land, which is closely tied to the forestland resources owned by farmers. Disparities in distribution during policy implementation are more easily noticed and compared, thereby amplifying the peer effect. In contrast, although forestry wage income and operating income are also influenced by ecological assistance policies, they incorporate individual labor and management effort to varying degrees. The former is linked to specific job positions, while the latter directly reflects farmers’ management decisions and labor input. In social comparisons, these are more readily attributed to individual effort rather than inequality of opportunity or resources, thus triggering a weaker sense of relative deprivation than property income, which arises purely from property rights. The peer effect associated with forestry transfer income did not exert a significant impact on farmers’ policy satisfaction. This is primarily because this type of income is closely tied to explicit policy stipulations and involves a relatively fixed distribution model. This structure fosters a strong perception among farmers of the benefits’ legitimacy and fairness, thereby weakening the intensity of relative deprivation and envy that might otherwise arise. Consequently, it avoids exerting an excessively negative influence on farmers’ policy satisfaction.

Finally, the suppressive effect of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction is strongly and predominantly directed towards the low and medium forestry income groups within the village, while it exhibits no significant impact on the high forestry income group. Farmers with medium forestry income are the most sensitive to the peer effect, experiencing the greatest negative impact on their policy satisfaction. This heightened sensitivity is closely related to their specific scale of land management and resource endowment. Compared to low forestry income farmers, those with medium income possess certain means of production, leading to stronger expectations for livelihood improvement. However, when compared to the high-income group that has already established economies of scale, they are more prone to developing a sense of relative deprivation through horizontal comparisons. This stems from perceived disparities in land resource allocation, inconsistencies in policy implementation, and other factors, consequently reducing their policy satisfaction. The satisfaction of high-income farmers, conversely, is not significantly influenced by peer effects. As primary beneficiaries of the ecological assistance policies, they have optimized their land management structures through means such as land transfer and consolidation facilitated by the policies. Consequently, they derive substantial benefits that are not easily comparable in a straightforward manner. Their satisfaction stems from the consolidation of pre-existing interests [71] and is therefore less affected by comparisons with their peers.

Therefore, future ecological assistance policies should shift towards more refined and differentiated implementation pathways, providing targeted guidance based on the cognitive characteristics and resource endowments of different farmer groups. Simultaneously, efforts should expand diversified livelihood strategies and scientifically design reasonable benefit redistribution mechanisms to holistically enhance the inclusivity and satisfaction derived from the policies.

5.4. Limitations of the Study

Although this study innovatively incorporates peer effects into the analytical framework for assessing farmers’ satisfaction with ecological assistance policies, revealing the specific impact and mechanisms through which PEEA operate within rural social networks on policy satisfaction, it nevertheless has several research limitations. Firstly, ecological assistance policies constitute a long-term systematic endeavor; however, the data employed in this study are cross-sectional, capturing only the static impact of the policies at a specific point in time. Future research could acquire longer time-series data to conduct a more comprehensive evaluation of the long-term dynamic influences and sustained effects of these policies on farmers’ policy satisfaction. Secondly, the data primarily originate from households that have been lifted out of poverty in key support counties designated by NFGA. While this reflects policy outcomes in a region typified by the overlap of ethnic minority concentration and ecological fragility, it imposes limitations on the geographical generalizability of the sample. Future studies could expand the research population to encompass the whole of China or other similar developing nations, exploring the commonalities and differences in ecological assistance policies under varying socioeconomic and policy contexts. Thirdly, this study utilizes a single-item measure to gauge farmers’ policy satisfaction. This approach is common and efficient in large-scale social surveys like the CGSS and CFPS, effectively capturing policy perception at an aggregate level. Furthermore, a series of robustness checks were conducted to ensure the reliability of the results. Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that a single-item measure has inherent limitations in uncovering the multidimensional nuances of policy satisfaction. Future research could develop and employ more refined, multidimensional scales of policy satisfaction to provide more detailed insights for policy optimization. Fourthly, this study primarily employs forestry income to measure the peer effect. While this approach captures the core of social comparison, it does not fully encompass all dimensions of social interaction. Future research could aim to develop a composite indicator for PEEA, enabling a more nuanced analysis of the multidimensional mechanisms underlying the peer effect. Fifthly, constrained by the survey data, this study was unable to deconstruct the heterogeneous patterns of internet usage. Subsequent studies could leverage richer data on internet usage patterns to examine differential effects of PEEA across various user groups, thereby achieving a more comprehensive understanding of the internet’s influence on social behavior and attitudes.

Despite these limitations, the theoretical foundation and research methodology of this study are scientifically sound. It systematically elucidates the critical role of peer effects in policy evaluation, offering novel theoretical perspectives and empirical support for understanding the factors and mechanisms that shape farmers’ policy perceptions within rural social networks.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Utilizing 2023 survey data on forestry income from households in key support counties designated by the NFGA, this study investigates the impact and mechanisms of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction. The empirical findings reveal that:

- (1)

- PEEA exerts a significant negative influence on farmers’ policy satisfaction. This conclusion remains robust after addressing potential endogeneity concerns using the CMP estimator and undergoing a battery of robustness checks.

- (2)

- Further analysis indicates that the information transmission mechanism amplifies the suppressive effect of PEEA on policy satisfaction, whereas a substitution relationship exists between the social interaction mechanism and PEEA in shaping farmers’ policy satisfaction.

- (3)

- Heterogeneity analysis demonstrates that the impact of PEEA on farmers’ policy satisfaction is asymmetric. Specifically, farmer groups over the age of 50 exhibit a stronger peer demonstration effect regarding policy satisfaction. Farmers with lower human capital are more susceptible to peer effects in their policy satisfaction assessments, and the influence radiates across a wider range of fellow villagers. Regarding different types of forestry income, forestry property income, forestry wage income, and forestry operating income all significantly negatively affect farmers’ policy satisfaction and demonstrate substantial PEEA. Among these, the PEEA associated with forestry property income exerts the most pronounced influence. The low and medium forestry income groups are more significantly affected by PEEA. Furthermore, among these, the medium forestry income households demonstrate the highest sensitivity to the peer effect, experiencing the most substantial negative impact on their policy satisfaction.

6.2. Policy Implications

This study yields the following significant policy implications:

- (1)

- Optimize the top-level design of ecological assistance to promote the rational distribution of forestry income. Enhance the effective integration of ecological assistance, rural revitalization, and common prosperity. While facilitating income increases for farmers in ecologically fragile ethnic regions through forestry support measures, it is crucial to prevent income inequality from further widening disparities within villages. This approach aims to enhance farmers’ sense of benefit and well-being derived from the ecological assistance policies.

- (2)

- Establish policy release platforms and improve information dissemination channels. Strengthen the digital infrastructure in rural areas and set up online community information centers to promptly deliver policy information and development updates to farmers, thereby enhancing their awareness and participation. Conduct digital skills training for farmers and regularly organize online and offline events that interpret ecological assistance policies, improving their understanding and ability to utilize this information.

- (3)

- Guide rational interpersonal spending and improve rural governance systems. Fully acknowledge the objective importance of such spending in rural governance and introduce context-specific initiatives to promote rational consumption related to social gifts. Promote the gradual improvement of informal institutions, properly guiding farmers to establish positive social norms within their reciprocal exchanges, which can enhance their enthusiasm for participating in ecological assistance policies.

- (4)

- Fully consider the “demonstration effect” of group behavior and implement differentiated policies for specific groups. Introduce forestry ecological assistance policies tailored to the needs of different age cohorts. For groups with lower human capital, provide targeted employment guidance and technical training for modern forestry production, encouraging them to play a more active role in ecological protection and rural revitalization.

- (5)

- Explore diversified forestry management projects to broaden income-increasing channels under ecological assistance. Promote the diversified transformation of land use patterns in ecologically fragile ethnic regions, facilitate the rational transfer of collective forestland rights, and encourage appropriately scaled forest management. Within the existing ecological assistance policy framework, rationally develop diverse forestry industries such as understory economy and forest health tourism, expand households’ diversified income sources from forestry, improve land use efficiency, and strengthen the long-term livelihood stability of farmers and their support for policy implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z. and X.Z.; methodology, R.Z. and X.Z.; software, R.Z. and X.Z.; formal analysis, R.Z. and X.Z.; resources, R.Z.; investigation, R.Z. and X.Z.; data curation, R.Z. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z. and X.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.Z. and X.Z.; validation R.Z.; visualization R.Z.; funding acquisition, R.Z. and X.Z.; supervision X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Central Public Research Institutes Fundamental Research Funds for the Project of Chinese Academy of Forestry (grant number CAFYBB2021QC002) and the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number 22BGL313).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PEEA | Peer effects in ecological assistance |

| NFGA | National Forestry and Grassland Administration |

| CMP | Conditional Mixed Process |

| CGSS | China General Social Survey |

| CFPS | China Family Panel Studies |

Appendix A

China’s ecological assistance policy aims to synergistically promote ecological protection and rural revitalization. Its core mechanism involves translating ecological conservation actions into substantive income for farmers through various pathways. It is not a single policy but rather a multi-dimensional, comprehensive policy framework. This framework encompasses ecological engineering projects, the creation of ecological public welfare positions, support for ecological industries, and ecological protection compensation. The specific policies and corresponding subsidy standards are summarized in Table A1.

Table A1.

Types of ecological assistance policies, target beneficiaries, and subsidy standards.

Table A1.

Types of ecological assistance policies, target beneficiaries, and subsidy standards.

| Policy Type | Specific Policy | Target Beneficiaries | Subsidy Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological engineering projects | Work-relief special projects | Local laborers participating in project construction shall prioritize the recruitment of households lifted out of poverty. | The total labor remuneration for the project must account for no less than 30% of the central government funds. Individual labor remuneration is approximately 150–300 RMB per person per month. |

| Ecological poverty-alleviation afforestation cooperatives/village self-build | A certain percentage of laborers with capacity from households that have been lifted out of poverty must be engaged to participate in ecological engineering projects such as afforestation and desertification control. | Remuneration is obtained through participation in project construction, with specific standards varying by project. | |

| Ecological public welfare positions | Ecological forest and grassland ranger positions | Recruited from households that have been lifted out of poverty, they participate in the management and protection of resources such as forests, grasslands, wetlands, and desertified land. | The per capita annual stewardship subsidy is no less than 8000 RMB. |

| Other rural ecological public welfare positions | Targets populations residing near ecological protection zones who are at risk of falling back into or into poverty, meet the job requirements, and have the capacity to work. | The subsidy is determined by local specific standards, approximately 500 RMB per person per month. | |