Abstract

This article examines the initial physical models of new towns. Its aim is to identify physical models for new towns that articulate Western planning concepts, to understand the transformations in the models and their causes and trace their development and future trajectory. Israel’s new towns have been selected as a case study for two main reasons: Israel continues to plan and construct new towns, and in doing so, draws on Western planning models and values. An examination of these models, and their transformations over time reveals that since the 1960s, two key motifs can be discerned: the grid model and the linear model. The study found that similar models may in fact reflect contradictory approaches to communality and individualism, coercion and free choice, although the general trend is one of transition from communality toward individualism. It was also found that the more rigid the plan—and thus perceived by planners as “more correct”—the more it fails, as the future is inherently unpredictable. Based on an analysis of these plans and the gaps between them and the facts on the ground, the article concludes by providing physical recommendations for the planning of new towns.

1. Introduction

A “new town” is defined as a town initiated and planned by the state or by experts on its behalf. The new town is intended to encompass a comprehensive array of activities, enabling much of daily life to take place within it [1]. Nevertheless, it is born out of a schematic model, which is the focus of this article.

According to Forsyth & Peiser (2021) [1], the discourse on models for new towns—globally, and in Europe in particular—peaked in the years following World War II and continued until the late 1970s. During this period, 67 countries developed at least one new town with a population of 30,000 in 2021 (a figure drawn from the Garden City model, see below). Most were industrial towns located behind the Iron Curtain—that is, towns built around a factory to house workers, develop peripheral regions, and build scientific capacity. Many were also designed to decentralize the population. Approximately 28% of the new towns were built in Western Europe [1], primarily in countries that adopted a centralized and interventionist approach to territorial development: the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands [2].

Theoretical models developed prior to the world wars predominated the planning of the new towns. Soviet planners developed towns based on the linear city model [3]. The Western European models, which form the core of this article, were grounded in two principal theories: the Garden City and the Athens Charter. The Garden City was designed to provide a high quality of life based on a low-rise, green-rich village, combined with diverse services and employment opportunities, as befits a self-sustained town. This model endowed the new towns with zoning, restriction of the target population (in the case of the Garden City, this was specifically defined as 30,000 inhabitants) and, in particular, with low density and proximity to nature [4]. The Athens Charter of CIAM [5] contributed the principles of zoning, access to nature, and especially the free-standing building layout—the “open plan”—set on large, street-less plots, as if the buildings were placed in a park, as further developed in the model of the Radiant City [6,7].

The new towns constructed by states reflected the hegemony’s control over everyday life—both because state-appointed planners expressed the prevailing worldview of their time, and because the city itself served as the container of daily life. Meticulously planned from the ground up, the towns thus embodied the hegemonic conception of what constitutes a proper environment, a suitable home, and, above all, a desirable lifestyle [8]. Accordingly, alongside the physical response to needs—such as the provision of housing and the redistribution of populations that had concentrated in metropolitan areas in an unplanned and uncontrolled manner—the new towns also reflected worldviews: the provision of proper and just housing conditions for all (light, air, landscape), inspired by socialist values [9]; educating residents for modernization [10]; and the encouragement of communal cohesion in expansive open spaces and public institutions. It was believed that detailed planning—of streets and housing units, employment and economic frameworks—would make it possible to anticipate and address all future physical and social needs of the town and its residents [1].

However, planning is one thing, and reality another. A new town is planned in the present for a target population, and its construction unfolds over several decades. To ensure that the population continues to grow, and to prevent outmigration during the process—which may ultimately lead to the decline of the new town—it is crucial to maintain a high quality of life throughout the stages of construction. It appears that some of the new towns have failed to reach their target populations. In their early years, the new towns suffered from a lack of infrastructure and from being isolated from their surroundings [11]. Moreover, the quality-of-life promise failed to materialize, certainly not while the town was still under construction [12]. In addition, the aspiration that new neighborhoods would generate communal life remained largely on paper. It became clear that people tended to build community with those similar to themselves, rather than merely with those encouraged or coerced to be located in their physical proximity [11]. Finally, the new towns deliberately lacked an urban experience and were marked by visual monotony [13]. In other words, in many respects, they were not necessarily better than the old cities they sought to “reform”—quite the opposite.

By the 1980s, it became clear that the foundational idea of modernism—that human reason and intellect could fully control reality and plan the future in absolute terms—was no longer tenable. Regarding town planning specifically, the city’s inherently complex structure proved highly resistant to such control. In his monumental work, S, M, L, XL: Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rem Koolhaas argues that the role of “new urbanism” is no longer to pursue stable and absolute forms, but rather to enable processes that, at present, are entirely unpredictable. In other words, urban planning should serve merely as an enabling infrastructure [14]. Consequently, there is no longer any point in developing fixed physical models for new towns. Reflecting this shift, the International New Town Association has, since the early 1990s, been renamed the International Urban Development Association [11].

The values used to inform the new towns have also lost traction. The socialist value has given way to the glorification of individualism and to neoliberalism. The state now takes less responsibility for the welfare of young couples and families—once the primary target population of the new towns [15]. The aspiration for communal resilience, which had been dominant in the post–World War II era and which neighborhood planning sought to promote, has faded away. The individual and their preferences now take precedence [16]. Furthermore, decades into the postwar era, there is no longer any need to educate the population toward modernization.

Indeed, there are no national projects for the establishment of new towns in Western Europe in the 2000s. There is no longer any increase in the local population, and reality has overtaken the original utopian vision [2]. The forecast is that new towns will remain a modest component of overall development. It is possible that, as was the case following World War II, new towns would be established to resettle refugees after political upheavals or in the aftermath of major disasters such as earthquakes or floods [17]. But they would not be a significant feature.

From the 1990s, abstract values that need to be accommodated into existing towns have replaced the “total” concrete physical model. This includes Peter Hall’s Sociable City [18], subsequently developed together with Colin Ward, which was based on small, compact, walkable cities with mixed uses that include diverse housing (including public housing), employment, local commerce, green areas, community agriculture, and public services. These are located along a backbone of public transportation and together create an urban whole greater than the sum of its parts [19]. The concept of the ecological city, corresponding to the sustainability value, was expressed in the British government’s 2007 commitment to upgrade or convert towns into net-zero carbon zones [20]. The value of healthy cities is promoted based on studies showing the link between mental and physical health and access to, and use of, urban open spaces [21]. These cities are characterized by green infrastructure that includes not only green areas but also a connection to urban nature and a perception of these spaces as community anchors [22].

And yet, what are the physical principles of new towns, insofar as there is a need to build them in Western countries? According to researchers [17,23,24], such towns would be more diverse than the post–World War II new towns and would draw on the physical principles of older cities that have developed organically over time. This refers to cities structured around vibrant urban centers, compactness, walkability, and mixed land uses [17]. They would feature resilient, diverse, aesthetic, and human-centered public spaces; a reduction in road and highway infrastructure in favor of public transportation and pedestrian and bicycle networks—with particular emphasis on rail systems and well-maintained, light-filled public spaces [23]. It is also argued that new towns would be based on planning flexibility, economic diversity [24], and the use of innovative technologies for managing water, energy, and waste, in order to create ecological cities [23].

In the 2000s, new towns are rarely constructed in the Western world, and scholars now refer to desirable characteristics for new towns rather than to physical models. Physical models had lost their appeal by the 1980s. This raises several questions: What models were employed in the new towns that emerged after the 1980s? What values did these models express? What happened to urban models as they encountered reality over time? And finally, is it still possible to outline a basic physical model for an optimal new Western town? This study addresses these questions.

In light of the above, the materials and methods Section 2 describes five research methods: selecting a representative case study; a systematic content analysis of the literature; content analysis of interviews with actors involved in the planning of new towns; schematic analysis of the models derived from the town plans; and finally, a field survey of the situation on the ground in 2025.

The results in Section 3 include four subsections. The first Section 3.1 reviews plans for new towns in Israel, heavily influenced by British models. The second and third, respectively, examine the plans of two new towns that were not based on a concrete Western model adapted to local needs. Section 3.2 focuses on Modi’in, planned in the 1990s. Section 3.3 reviews the new town of Harish, from the 2010s. Finally, the fourth Section 3.4 extracts the underlying schematic models from all the plans and assesses their evolvement over time.

2. Materials and Methods

To address the research questions, several methods were employed. The first involved selecting a representative case study. The state of Israel was chosen for two main reasons. The first lies in the fact that in Israel, new towns are still being constructed by the state, under close governmental supervision of the planning process. In other words, there are physical models [25]. These new towns are established to accommodate a rapidly growing population [26] and to disperse it across the national territory. Moreover, each new town reflects—according to its time—the prevailing hegemonic values, just as the European new towns did in the postwar era. The second reason stems from Israel’s self-perception as a Western state, which draws on Western theories and values and therefore expresses them in its urban planning [27]. In other words, Israel’s new towns serve as living physical embodiments of key European theories and hegemonic values.

Specifically, the thirty years of the British Mandate over Palestine (beginning in 1917), and the close collaboration at that time between British and Jewish planners [28], oriented the gaze of the state’s planners (from 1948 onward) toward British planning. The British planning law was adopted and remained in effect until the passage of Israel’s own Planning and Building Law in 1965. Much like in postwar Britain, the state’s planning approach was centralized and interventionist, and the physical models of British urban planning were almost directly replicated in Israel. Israel was not unique in this regard—Britain was the pioneer of European new town planning in the postwar era [20].

The British models were imported to Israel with necessary adaptations due to divergent circumstances: massive immigration to Israel, which resulted in a severe housing crisis; significantly limited capacity to construct adequate dwellings after the 1948 war; and the absence of a local planning tradition. Subsequently, Israel’s new towns were constructed through an orderly process of research and lessons learned, while incorporating European planning concepts.

At this point, several qualifications are in order. First, this article focuses on the physical models of the new towns. By their very nature, models are abstract constructs that articulate a very general idea. Their implementation, however, confronts them with the specific conditions of the physical site and with the concrete contents of place. To maintain the article’s focus on models, it does not address variables specific to Israel and its geopolitical circumstances, such as the siting of towns within the territory or their designation mostly for the Jewish population, which constitutes 80% of the residents within the boundaries subject to Israeli law. It also does not address the Jewish settlements in the territories occupied in 1967: in most of these areas, Israeli law does not apply, and in any case, these territories include only two new towns with populations over 30,000. One was planned before the 1980s, while the other was not originally planned as a town, but rather as a suburb.

Second, no public participation took place in the planning processes of the new towns, just as there was no public participation in similar new towns elsewhere in the West. This stems from the fact that the initial models were too abstract, and the fact that the towns were planned for populations that had not yet arrived [29].

Third, urban models are not sensitive to the residents’ culture, since they are highly general and the future inhabitants are not yet known. At more detailed scales, and in plans specifically intended for populations whose culture is known, cultural adaptation can be observed in the fabrics and buildings of new towns [30,31].

Fourth, despite Israel’s Mediterranean location, the planning of the new towns did not draw on local traditions better suited to climate conditions, for example. Rather, it positioned Israel as an extension of Western Europe, certainly when it came to the models of new towns. This orientation was a result of the European origins of the Jewish planners, who constituted part of the Israeli elite and consolidated the local hegemonic mindset. Relatedly, the only school of architecture in Israel before 1992 was also dominated by the Eurocentric approach of its founders and leaders [32]. As previously discussed, this orientation was informed in part by the example provided by British planning.

The study’s second method employed a content analysis approach based on a systematic review of both the historical planning literature and contemporary sources.

The third method included interviews with professionals who worked on the plans for the new towns or guided their planning process in the years 2001–2025, on behalf of the Israeli Ministry of Construction and Housing. This analysis identified the theories and precedents informing this planning and their results on the ground.

The fourth method applied was analysis of urban plans based on four fundamental components present in every city and responsible for shaping its model: residential areas, community and urban centers, green spaces, and the mobility network. This analysis was conducted in two phases: at the time of initial construction and after years. This enabled us to trace both the underlying logic that generated the city and the changes it underwent as it confronted reality.

To validate the findings, a fifth method was employed: a field survey and the collection of observations. The findings are illustrated in the photographs presented following the graphic diagrams.

The content analysis of the literature review and interview findings addressed the reasoning underlying the specific planning decisions: the choice to adopt European models, the drawing of lessons from earlier models, and the values that planners sought to embed through these models regarding the balancing of communality and individualism. The analysis of the plans and of the situation on the ground employed paired schematic graphic schemes—of the original plans and of the situation in 2025—in order to identify the differences between the initial models and their subsequent evolution.

3. Results

The results section is structured as follows. The first three subsections proceed chronologically, reviewing the models prior to the 1980s (Section 3.1); the model of the 1990s (Section 3.2); and the model of the 2010s (Section 3.3). The final subsection (Section 3.4) examines the changes between the initial models and reality. The years selected for in-depth analysis—the 1990s and 2010—were chosen because they represent the post-1980s period, in which two new towns were planned, which reflects a significant evolution in planning thought.

3.1. Models of New Towns and Their Origins up to the 1990s

As previously noted, the years of the British Mandate in Palestine, along with the fact that Britain was the pioneer of new towns, provided a strong rationale for adopting the British model in the planning of new towns in the State of Israel. Israel founded its State Planning Department only weeks after declaring its independence in 1948 [33], and the planners published their plans in 1951 [34]. Israeli construction was based on apartment buildings and cooperative land ownership—where the land was collectively owned by all neighborhood residents—while the British model emphasized terraced single-family houses. Nevertheless, the British New Town model, and particularly that of Harlow (1947), was imported and adapted in Israel [27].

The British towns themselves were based on Howard’s Garden City theory and on the Neighborhood Unit concept developed by the American urban planner Clarence Perry. Perry viewed the neighborhood as a community unit, structured around central community institutions, with walking distances of approximately 400 m from the neighborhood center to the farthest house [35]. British town planning—and Israeli planning that followed—isolated low-density, green-rich neighborhoods to the point of severing them from one another by means of green belts [36]. A single road typically connects each neighborhood to the others. Thus, communality was imposed through the disconnected layout, as was proximity to nature. This was the case even though Israel itself had no industrial cities in need of “correction” through the design of rural towns, as had been the case in Europe (Figure 1).

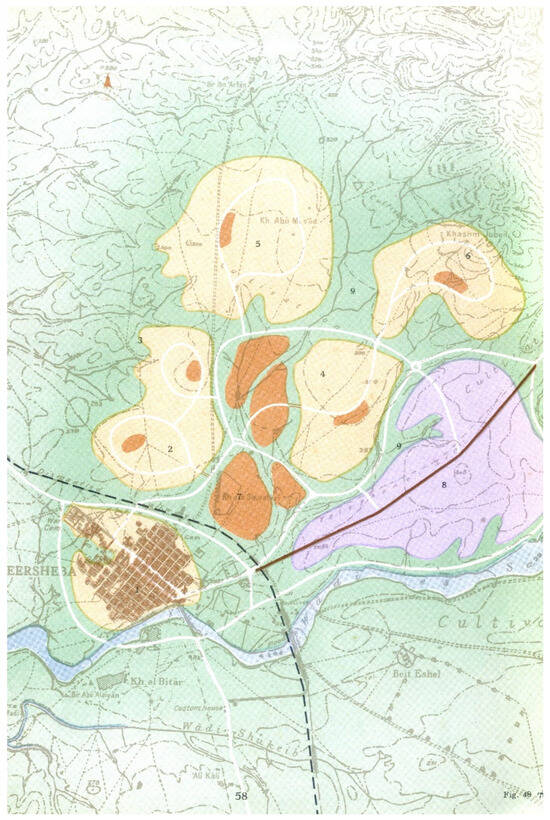

Figure 1.

Be’er Sheva, a city planned in 1951 for 55,000 residents (more than 200,000 in 2025), was designed in the shape of a flower: the urban center as the stamens, and the neighborhoods as detached petals. A neighborhood center is located within each. Neighborhoods are shown in light brown; urban and neighborhood centers in dark brown; the industrial zone is purple. Source: [34] p. 58.

The lessons learned from the initial planning phase were not long in coming. In Israel, as in Britain, the first critique addressed the absence of an urban pulse, the isolation of neighborhoods from one another, and visual monotony [37]. The second critique related to the ambiguity surrounding the proper stage at which to build the Central Business District (CBD). If constructed simultaneously with the new town, the CBD would fail to develop due to a lack of purchasing power and would wither. If not constructed, the town would be left without a CBD for many years [38]. The third critique emerged from the clash between British planning and the Israeli Mediterranean climate, characterized by a long and dry summer: the green areas in the new towns did not flourish and were often used for dumping waste [39]. Consequently, it was argued, the time came for Israel to adopt a new British model.

The second model adopted was the linear city model, exemplified by the Scottish new town of Cumbernauld (1956), planned for 70,000 residents [40], and by the new English town of Hook (1961), designed for 100,000. Although Hook was never built, the book detailing its planning rendered it highly influential. Its core was intended to be entirely walkable—from the outermost house to the CBD. Accordingly, Hook was planned such that walkable distances—approximately 500 m in each direction from the CBD—determined its width. Pedestrian pathways, lined with daily public facilities, were designed to lead safely to the CBD. The center itself was meant to develop linearly, in parallel with the two adjacent neighborhoods, thus addressing the aforementioned challenge of phased urban development. Movement within it, which was designated for pedestrians only, was to rely on public transport running beneath it, thereby allowing the CBD to extend uninterruptedly [41].

Beyond the lessons learned, a new value emerges from this model: communal urbanism [42]. The aspiration to foster a sense of community persisted and was rooted in daily encounters along the pedestrian routes leading from the residential neighborhoods to the CBD, as well as within the CBD itself. At the same time, the CBD was envisioned as a meeting point fostering meaningful human interaction for all city residents—thus marking the beginning of free choice regarding one’s desired community. This may be seen as the onset of an individualistic, democratic, and above all, pro-urban approach.

The Israeli new town of Karmiel, founded in 1964, adhered to these principles in its eastern section. In the western section, however, the outermost houses were situated farther from the CBD, and therefore, a neighborhood center was also planned. The CBD itself was intended to stretch over 1.7 km (Figure 2).

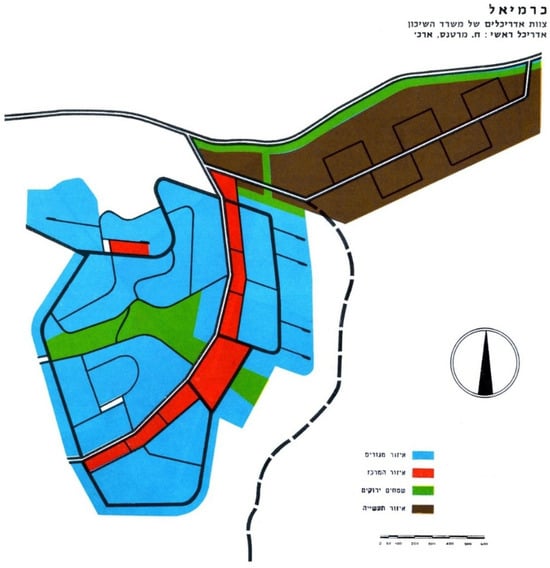

Figure 2.

The 1964 plan for the new town of Karmiel, designed for 50,000 residents (the population in 2025 is nearly as large). The CBD, designated exclusively for pedestrian use, forms the city’s spine (in red). A major vehicular axis runs parallel. Pedestrian pathways from the surrounding neighborhoods (in blue) lead into the CBD. Green areas are marked in green; the industrial zone is brown. Source: [43] p. 6.

3.2. The Urban Model of the 1990s

In the 1970s and 80s, new neighborhoods were planned in Israel, but no new towns were established. The first new town after the long hiatus was planned in the 1990s, prompted by a wave of immigration following the collapse of the Soviet Union, a housing crisis, and the enduring aspiration to regulate population distribution. However, already in the 1980s, the seeds of a fundamental shift in urban planning in Israel had been sown. A combination of lessons learned from the failures of earlier models [44] and the adoption of a new model rooted in Western urban planning gave rise to the pattern of the “return to the pre-modernist city”—referring specifically to a return to the European pre-industrial city, with its streets, boulevards, squares, and urban blocks [45,46].

In the planning of the new city, Modi’in, architect Moshe Safdie was informed by lessons learned from previous city plans, along with a significant influence of the principles of the linear city, leading him to design a hybrid plan. On the one hand, the city features sloped pedestrian routes leading toward central urban sites, reminiscent of the linear model. On the other hand, Modi’in is founded on the grid model, which is better suited to free urban development across an area, rather than along a single axis, as in the linear model. These principles, together with the city’s specific topography—comprising hills and valleys—shaped the final plan. Residential areas were placed on the hills, along streets that follow the topographic contours, while community centers were located in the valleys, incorporating green spaces, neighborhood commercial buildings, and public institutions. Main traffic arteries ran through these areas. The CBD, including commercial, cultural, and transportation functions, was planned at the point where the valleys converged, adjacent to a large park [47] (Figure 3).

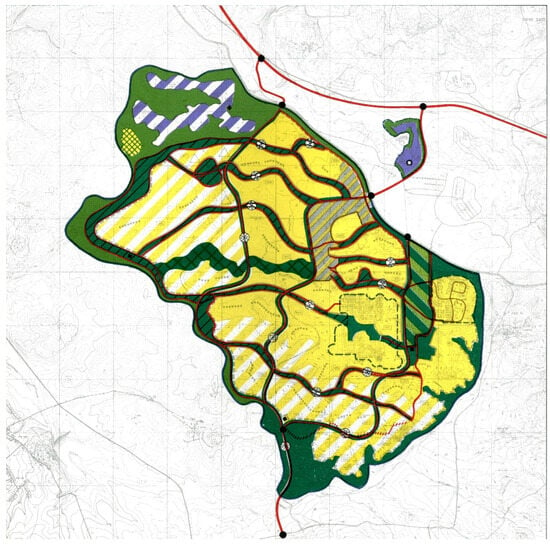

Figure 3.

The plan for the new city of Modi’in (1990), designed for 250,000 residents (about 99,000 in 2025). The externalization of public gardens and civic buildings echoes the model of the British new town of Milton Keynes (1970) [48], although this precedent was not cited by the planners. Yellow indicates residential areas; green—multi-use green spaces; red—main roads; striped gray—CBD; purple—employment and industrial zones. Source: [49] pp. 24–25.

The choice to locate public services—central open spaces, neighborhood commerce, and local public institutions—in the valleys externalizes and makes them accessible to all city residents. First, this is the landscape viewed from the residential buildings situated on the surrounding hills. Second, it reflects the overarching urban logic and is therefore legible to all residents. Third, the routing of the main traffic arteries through the valleys conveys the idea that these centers are not merely neighborhood-based but are intended for the entire urban population. In other words, every resident can choose the garden or public facility that best suits them from the citywide offerings. This reinforces the principle of free choice, it reveals one significant gap: the absence of the potential for spontaneous future development. The decision to concentrate neighborhood commerce exclusively in purpose-built structures located in the valleys (rather than along streets, designated solely for residential use) has prevented the emergence of street life—namely, shopping and lingering along mixed-use streets.

In Pisgat Ze’ev, a new neighborhood in northern Jerusalem created in the 1980s, commercial ground-floor units were built along a residential street, which led to the decision to avoid such streets in Modi’in [50]. Safdie and officials from the Ministry of Construction and Housing drew lessons from that earlier experience, where prospective residents feared that their peace and quiet would be disturbed and were reluctant to purchase apartments along the commercial street. At the same time, theories that emphasized the urban pulse of the pre-modernist city in the commercial streets were widely accepted. Hence, a dissonance arose, one that was expected to be resolved in the next new town: Harish.

3.3. The Urban Model of the 2010s

The desire to correct the main shortcoming of Modi’in—the absence of vibrant, mixed-use streets—informed the planning of Harish in 2010. This town was designed around a central urban street running its full length. As it served as the city’s main entrance, it was intended to channel all vehicular traffic, accommodate public transportation (with a dedicated lane), and host most of the city’s commercial activity, as well as some public services (such as clinics). To enable this, residential buildings were constructed above a commercial ground floor, covered by a colonnade and facing a broad sidewalk, along both sides of the main street. This street was planned as the city’s vibrant spine, adjacent to the CBD and extending beyond it for more than two kilometers, along which several anchor stores such as supermarkets were planned. Neighborhood centers and gardens were positioned along the neighborhood streets [51,52].

The planners’ vision was for a city of 100,000–200,000 residents that would serve as an urban magnet. A conceptual scheme of the original plan was based on three longitudinal residential quarters surrounding the CBD. Each was allocated a very long main street, designed to carry both private and public motorized traffic. Residential areas were to extend up to 500 m from this street, thereby ensuring reasonable walking distances between the outermost homes and the neighborhood’s central axis [51]. This scheme combined the flower model (for the city as a whole) with the linear city model (for its neighborhoods). The linear residential quarters were based on public transportation movement along a very long main street—too long to support continuous pedestrian movement.

In the first phase (2012), the plan was approved for only 50,000 residents, and the original scheme was scaled down to include only parts of two residential quarters. The city was designated for the Jewish ultra-Orthodox population, characterized by low car ownership and large families. Therefore, it featured short walking distances and relied on bicycle use and a dedicated public transportation lane running the full length of the town. The prevalence of working from home, typical of this population, led the planners to include a mechanism within the plan allowing residential units to be converted into small businesses within the neighborhoods [52]. In other words, the ecological principles of the plan and its inherent flexibility—both aligned with the values of the early 21st century and largely absent from previous new town plans—were here integrated with the specific needs of a particular population, as perceived by the planners.

Due to public protests from the general Israeli population, the plan to designate Harish exclusively for an ultra-Orthodox population was shelved, and the town was opened to all segments of the population. A decade later, an additional plan was prepared, projecting 100,000 residents. To support this, additional land was allocated for a new eastern neighborhood and for mixed-use areas combining employment and housing [53] (Figure 4).

Both plans responded to the “correct values” previously mentioned: ecological, health-oriented, and communal. In terms of ecology, the planners stipulated significant densification so that Harish would be compact and rely on walking and public transportation rather than on private vehicles. According to the plan, building heights range from six to 30 stories. Additional elements include green roofs on public buildings, ecological crossings for wildlife under roads, locating and preserving seasonal winter ponds, and the design of dedicated gardens for pollinators, wildflowers, and butterflies. To respond to the connection established in the literature (see above) between green vistas and health, numerous viewpoints were planned to overlook the open surroundings of the city [54]. A hospital and a medical school were also planned [55]. To support the communal value and freedom of choice, many public gardens were planned along city streets, as well as numerous public spaces throughout the city—principles already present in the original plan [51] (Figure 5).

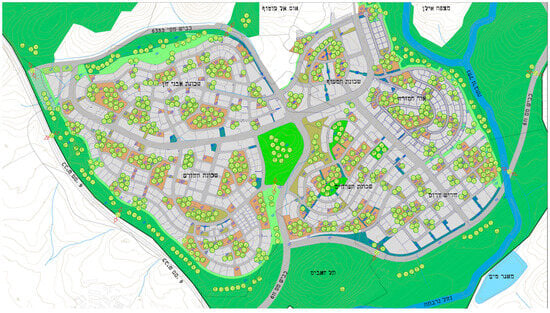

Figure 4.

The 2022 plan for Harish, for 100,000 residents (34,000 in 2025). It elaborates on the original plan and adds an employment area. Yellow indicates residential zones; gray—CBD and residential areas; pink—mixed-use employment and residential areas; green—natural landscapes and the central park. The main street runs through the city from east to west. Source: [55].

Figure 5.

Ecological plan for Harish (excluding the southern employment area), expressing the connection to nature through internal gardens and outward-facing vistas (in green). The integration of gardens with public and community spaces (in brown) is evident, as is their placement along street edges. Source: [54].

3.4. Urban Models over Time

The planning schemes of Israel’s new towns may be summarized as follows: a flower model (in Be’er Sheva); a CBD as a spine (in Karmiel); a grid integrated with green spaces and public institutions (in Modi’in); and a composition of a commercial street, CBD, and neighborhood centers (in Harish); (Figures 6, 8, 10 and 12 to the left). A retrospective analysis of these models—their implementation and outcomes—reveals that in all cases, a gap emerged between the planners’ intentions and the reality on the ground.

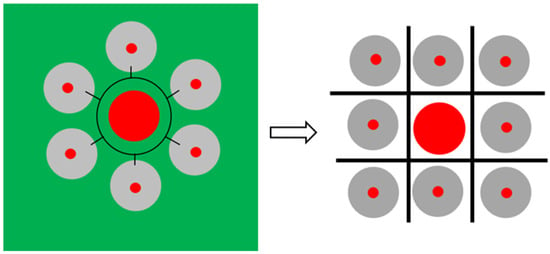

Be’er Sheva’s flower scheme (1951) failed almost immediately. The separation between neighborhoods created isolation, while the green belts did not flourish and were used for waste dumping. In 1965, a new, “corrective” plan was designed, replacing the open spaces with major roadways [56] (Figure 6). These transportation-oriented roads, with residential buildings turning their backs to them, still disconnect the city’s neighborhoods from one another to this day [57] (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Be’er Sheva, the “flower city”: The flower scheme, originally based on green spaces that failed to materialize, was transformed into a road network, yet the neighborhoods remain isolated from one another to this day. Legend: Gray—residential areas; Red—neighborhood/urban centers; Black—mobility network; Green—green spaces.

Figure 7.

The main roads in Be’er Sheva still constitute a barrier separating the neighborhoods. Photo by author.

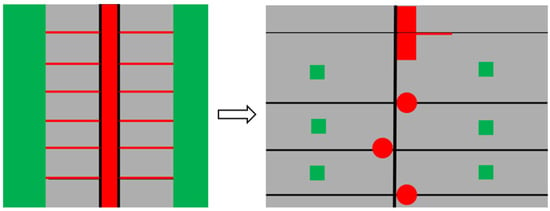

Karmiel’s linear city scheme (1964) failed as well. The notion that a new town could grow exclusively along the CBD, without expanding laterally, is unrealistic—due to variations in topography, soil quality, landscape values, and other factors. Likewise, it is not feasible for a pedestrian-only CBD to be visually disconnected from the main vehicular axis that feeds it. As a result, the portion of the CBD constructed at the time of the city’s founding—stretching just 240 m—has never been extended as originally planned. Over the years, the commercial segments in Karmiel that developed along the main road (note that Karmiel expanded in other directions as well, not only linearly) have evolved like “beads on a string”—that is, as discrete neighborhood centers located near the main road, but not as a continuous CBD as initially intended (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Karmiel, the linear city: From a model of a narrow, green-belted city to a sprawling city with internal gardens; from a continuous vertical center to a center that develops like beads on a string along the main road. Legend: Gray—residential areas; Red—neighborhood/urban centers; Black—mobility network; Green—green spaces.

Figure 9.

One of the later neighborhood centers in Karmiel, accessed from the main road. Photo by author.

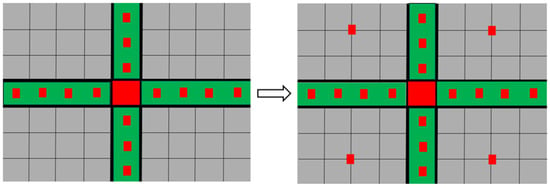

In Modi’in (1990), reality slowly began to assert itself over the original plan—though with considerable difficulty. Over the years, small-scale commercial activity emerged here and there on the ground floors of a few residential buildings [58]. The planning of relatively small apartment buildings, intended to define the city as “green” and thus to keep building heights below the treetops, helped enable such gradual changes. This is a modest indication that life in the city can evolve beyond the scope of an “omniscient” plan (Figure 10 and Figure 11). Nevertheless, isolated small-scale commerce does not suffice to create vibrant, mixed-use streets. The overall impression one receives when walking through the city—aside from the limited CBD area—is that of a dormitory town.

Figure 10.

From a grid-based city where public institutions and neighborhood commerce were integrated exclusively within designated green spaces, to a city that can accommodate changes in land use (with difficulty)—allowing commercial activity to emerge even along streets not originally planned for it. Legend: Gray—residential areas; Red—neighborhood/urban centers; Black—mobility network; Green—green spaces.

Figure 11.

(a) Green spaces between neighborhoods and roads, designed to connect residents and serve daily needs. In the distance, a supermarket is visible. (b) In practice, small shops are beginning to open on the ground floor of residential streets, at the expense of the inhabitants’ ground-floor parking spots. Photo by author.

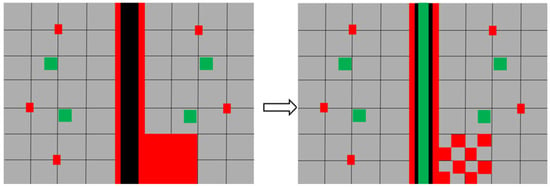

In Harish, the planners were guided by the aspiration to create a vibrant, mixed-use urban street—something that had been lacking in Modi’in. As noted, to ensure intensive use of the main street, it was designed to serve as the city’s main entrance, with a wide carriageway (two lanes in each direction for private transportation and one lane for parking, plus one dedicated lane for public transportation in each direction), and broad sidewalks separating its commercial frontage. The planners believed that in doing so, they were “making space” for lively street activity. They extended the street along the entire length of the city to ensure accessibility to the “urban pulse” throughout, and planned frequent, high-capacity public transit stops along it to overcome its otherwise unwalkable length.

In recent years, while the city is still taking shape, the result appears to be quite the opposite. The street is too wide, and therefore too disconnected, too long and largely deserted. As this is a socio-geographically peripheral town, the residents’ limited purchasing power is insufficient to support the expansive commercial frontage built from the outset. This has led to two outcomes. First, a shopping mall was constructed at the entrance to the city, concentrating purchasing power in a single location and offering a meeting point for residents. Needless to say, this further suppresses the already struggling commercial street. Second, the city engineer has decided to eliminate the dedicated public transportation lane in favor of a linear garden, with the aim of turning the street into a boulevard [59]. In other words, the aim was to emphasize Harish’s scenic rather than urban qualities, which are still far from being realized (Figure 12 and Figure 13). Regarding the CBD, absent significant purchasing power and work places, the CBD was constructed as a residential neighborhood interspaced with empty lots awaiting to be filled. In 2025, the neighborhood is unique only in terms of taller residential buildings.

Figure 12.

Harish: From a city planned with an integrated scheme of a CBD, neighborhood-community focal points along the street, and a single main urban street with intensive movement and mixed uses, to a city with a CBD (in 2025, a dense residential neighborhood interspaced with empty lots), neighborhood-community focal points, and a main urban street functioning primarily as a traffic corridor and boulevard. With only 34,000 residents in 2025, the street remains largely deserted. Legend: Gray—residential areas; Red—neighborhood/urban centers; Black—mobility network; Green—green spaces.

Figure 13.

Boulevard replacing the public transportation lane along the main street in Harish. Photo: Shalom Horesh [60].

4. Discussion

The literature review indicates that Western Europe no longer develops models for new towns, as it has become clear that cities are too complex to predict their future development [2,14,15,16], and that pre-modernist cities are superior to the planned new towns that followed [11,12,13]. It has also been understood that, instead of physical models for new towns, since the 1990s, recommendations have been advanced for improved planning [17,23,24] based on values such as communality, ecology [20], and health [21,22]. Nevertheless, since new towns are still being planned with reference to these same Western values, as demonstrated in the present findings, the question arises as to what can be learned from them.

In general, setting aside the 1950s radial flower model of the disconnected city, the Israeli new town models from the 1960s onward oscillate between two main motifs: the grid and the linear. However, one must not be misled by their visual similarity, as these models can be used for entirely different purposes.

The grid model of Be’er Sheva from the 1960s and that of Modi’in from the 1990s were designed for opposite purposes. While the wide, traffic-oriented roads of Be’er Sheva aimed at separating the neighborhoods—and succeeded—the wide roads in Modi’in, embracing gardens, public buildings, and neighborhood-level commercial centers, were intended to connect the neighborhoods—albeit without much success. The linear model of Karmiel was highly constrained: the city was planned in the 1960s around a longitudinal, pedestrian-only CBD, from which perpendicular pedestrian streets extended into the neighborhoods. Along these streets, daily-use public and commercial functions were located. In contrast, the main street forming the linear axis of Harish (planned in 2010) is only part of a more diverse urban system. Unlike Karmiel’s original design, Harish includes intra-neighborhood public spaces and gardens that are not inherently linked to the central street, as well as a separate CBD that adjoins the central axis, which extends beyond it. Unlike the earlier models, which follow a fixed and repetitive schema, Harish is a city of combinations, without a single comprehensive model. Thus, it includes an urban street, a CBD, and neighborhood centers.

The explanation for these differences lies not only in the technical lessons learned from one model to another, but also in the hegemonic values and conceptions shaping them. Over the seven decades of Israel’s existence, one can observe a shift from the imposed communality and rurality characteristic of the newly founded state toward urban individualism. The flower model of Be’er Sheva in the 1950s and the grid model that replaced it both suppressed urbanity and promoted neighborhood-scale living, reflecting a desire to create cohesive, melting pot-style immigrant communities. Karmiel’s walkable linear model in the 1960s expressed an aspiration for communal urbanity. This was manifested in planning that was based on a single pedestrian neighborhood path and a single urban path (the CBD), intended to maximize human encounters. In other words, the need for urbanism was already acknowledged, but not the value of free choice or individualism. In the 1990s, the desire for residents’ free choice was expressed in Modi’in’s navigable grid model, particularly in the externalization and accessibility of gardens and public buildings, so that all residents could select from the city’s offerings. From the 2010s onward, the aspiration for vibrant urbanity and individualism was integrated into the composite city model: Harish included a variety of elements—a mixed-use main street, a CBD, and separate community centers. These values were joined by additional Western conceptions such as flexibility of use, connectivity, and ecological awareness. These were expressed through mixed uses, compact development, a continuous public transport corridor across the city, and a wealth of ecological gardens. The value of communality was not abandoned but reflected in intra-neighborhood public spaces.

An examination of how the models have changed over time reveals that such changes in values and architectural fashions or practices are difficult to implement on the ground. The flower model of Be’er Sheva has indeed been replaced by a grid model, but its neighborhoods remain disconnected. The linear city model of Karmiel spans, in practice, only 240 m. The idea of a 1.7 km-long urban center, with movement based solely on pedestrian circulation—within both the neighborhoods and the CBD—has been superimposed on the physical and human reality and, therefore, proved unfeasible. Instead of a continuous linear center, neighborhood centers have been built adjacent to the city’s main traffic artery. Modi’in grid model, though seemingly open to change, has also proven difficult to adapt. To this day, only a handful of shops have opened along residential streets, meaning that even buying a loaf of bread requires residents to descend to the large supermarket in the valley, outside the residential neighborhoods. Finally, Harish’s composite model has also failed when seeking to impose itself on the residents. Paradoxically, the very effort to predesign a main street that would include everything to ensure success has ended up being detrimental. Too wide, too long and too monotonous, it is out of sync with the economic capacity of an emerging peripheral city. As a result, it has become a landscape asset rather than an urban one within the city’s early years. In other words, the more confident the planning is in its omniscience, the more it tends to fail over time.

5. Conclusions

This article focuses on the physical models of new towns. It should be emphasized that physical models are abstract constructs, and their success or failure is always mediated by contextual factors such as location, governance, and social composition, and the present paper deliberately restricts itself to the formal/typological dimension, leaving broader contextual analysis for future work.

In terms of the lessons to be derived from the specific cases discussed in this article, it becomes apparent that two planning motifs are clearly evident in Israel’s new town, throughout its history: grid and linear planning. Also evident from the foregoing review is the fact that these same motifs can express different, even opposing, values. Two broader approaches to planning also arise from this history: rigid and repetitive planning on the one hand, and on the other, planning that views the city as a composition—a diverse collection of spaces and related behavioral patterns. Based on both the Israeli experience and the European experience up to the 1980s, it is evident that the more rigid the planning, the more problematic it becomes. It imposes its internal logic on the residents and makes future changes more difficult to implement.

That being said, are there any operational conclusions that can inform physical modes of newer new towns, so that these become as functional as possible even along their extended process of emergence and becoming? Can physical conclusions be drawn regarding the four urban components that appeared in the graphic schemes: the mobility network (in black), urban and neighborhood centers (in red), green areas (in green), and residential zones (in gray)? Ultimately, new towns continue to be constructed—particularly in East Asia, South Asia, and Africa [1,61,62,63,64,65], and it is conceivable that they would also emerge in Western countries in response to climatic or demographic changes that are as yet unforeseeable [17]. Such towns will necessarily undergo a long and incremental process of development before reaching their intended scale and function.

Regarding mobility networks, the Israeli experience across all models suggests that the grid model is more conducive to change and is therefore preferable to its linear counterpart, which relies on a single central axis. It appears that establishing a hierarchy among the streets is advisable, as it provides perceptual clarity and makes the city more accessible. Furthermore, the denser the grid—especially in central areas—the more flexible the built environment along it can become, thus better accommodating multiple uses and enabling more vibrant urban life.

Regarding civic centers, it has been found that it is preferable not to plan a complete CBD in advance, but rather to adopt a bead-string approach, as evident in Karmiel’s case. That is, small clusters of retail, employment, and services located close to residential areas and connected by a transportation axis. These can create a fragmented yet functional whole during the early stages of urban development and may later either coalesce into a continuous center if the city grows and densifies or evolve in entirely different directions in response to unforeseen realities.

As for green spaces, they appear to contribute to urban beauty but often fail to live up to usage expectations—even when adjacent to public or commercial buildings (as evident in Modi’in). Therefore, small, visible intra-neighborhood green spaces located along the street, as in Harish, provide a better setting for community life, especially in the city’s early development phases. Note that this does not detract from the importance of designating a large green area with scenic and ecological value to serve as a central park.

Finally, regarding residential development, the long-term value of implementing the Garden City theory becomes evident. Its Israeli interpretation, as seen in Modi’in, where residential building height has been limited to treetop height, as well as in other cities that evolved from planned villages [66] was expressed early on in the construction of houses on relatively small plots, leaving part of the plot open for trees and green areas. Green spaces within the residential plots provided flexibility with regard to building density. In the initial stage of the town, when the population was still small, the buildings were modest in scale and embedded in greenery. Over time, in response to market forces and ecological values, multi-story buildings replaced the original houses, at the expense of the open and green spaces within the residential plots. In addition, changes in spatial usages were easier to implement due to the small plot sizes and relatively limited shared spaces. Therefore, the recommendation is to initially plan a new town as a green city, rich in vegetation. This greenery should be an integral part of the residential plots, so that, when the time comes, such a city can more easily develop intensive urbanism according to its evolving needs.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available. Everything is detailed in the reference list of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Forsyth, A.; Peiser, R. Introduction. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gaborit, P. European New Towns: The End of a Model? From Pilot to Sustainable Territories. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 230–249. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, G.R. Cities on the line. Archit. Rev. 1960, 761, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, E. Garden Cities of To-Morrow; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Corbusier, L. The Athens Charter; Grossman: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Corbusier, L. The City of To-Morrow and Its Planning; The Architectural Press: London, UK, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Corbusier, L. The Radiant City; The Orion Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman, R. Practicing Utopia: An Intellectual History of the New Town Movement; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benkő, M. Budapest’s large prefab housing estates: Urban values of yesterday, today and tomorrow. Hung. Stud. A J. Int. Assoc. Hung. Stud. Balassi Inst. 2015, 29, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragutinovic, A.; Pottgiesser, U.; De Vos, E.; Melenhorst, M. Modernism in Belgrade: Classification of modernist housing buildings 1919–1980. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 052075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A. The Promises and Pitfalls of New Towns. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Marans, R.W.; Xu, Y. Quality of life in New Towns: What do we know, and what do we need to know? In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J. Twentieth Century Architecture and Its Histories; Cambell, L., Ed.; Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain: London, UK, 2000; pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R.; Mau, B.; Werlemann, H. S, M, L, XL: Office for Metropolitan Architecture; Sigler, J., Ed.; The Monicelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 959–971. [Google Scholar]

- Cupers, K. The Social Project: Housing Postwar France; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shadar, H.; Shach-Pinsly, D. Toward a Methodology of Spatial Neighborhood Evaluation to Uncover the “Invisible Spaces” in Neighborhoods Built Through State Initiatives Between 1945 and 1980. Land 2025, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiser, R.; Forsyth, A. New Towns in a New Era. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 410–421. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. 1946–1996-from new town to Sustainable Social City. Town Ctry. Plan. 1996, 65, 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.; Ward, C. Sociable Cities: The 21st-Century Reinvention of the GARDEN City, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freestone, R. A Brief History of New Towns. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maller, C.; Townsend, M.; Pryor, A.; Brown, P.; St Leger, L. Healthy Nature, Healthy People: Contact with Nature as an Upstream Health Promotion Intervention for Populations. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellenberg, S. The Twenty-First-Century New Town Site Planning and Design. In New Towns for the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Planned Communities Worldwide; Peiser, R., Forsyth, A., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy, J.R. The eco-city: Ten key transport and planning dimensions for sustainable city development. Environ. Urban. 2006, 18, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J. From New Towns to Growth Areas; IPPR: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shadar, H. The Building Blocks of Public Housing in Israel: Six Decades of Urban Construction Initiated by the State; Ministry of Construction and Housing: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2014. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson, Y. Demographic Processes in the Land of Israel, 1948–2022; The Israeli Institute for National Security Studies (INSS): Tel Aviv, Israel, 2024; Volume 27, p. 37. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Shadar, H.; Oxman, R. Of Village and City: Ideology in Israeli Public Planning. J. Urban Des. 2003, 8, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H.; Maslovski, E. Pre-war design, post-war sovereignty: Four plans for one city in Israel/Palestine. J. Archit. 2021, 26, 516–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insa-Ciriza, R. Two ways of new towns development: A tale of two cities. Urban Dev. 2012, 219–242. Available online: https://books.google.co.il/books?hl=iw&lr=&id=Wi-aDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA219&dq=Two+ways+of+new+towns+development:+A+tale+of+two+cities&ots=DkaTSTrzPS&sig=ddnRE_ECslG7ZNhN2j6VEZg1X5s&redir_esc=y#v=onep-age&q=Two%20ways%20of%20new%20towns%20development%3A%20A%20tale%20of%20two%20cities&f=false (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Shadar, H. Vernacular values in public housing. ARQ Archit. Res. Q. 2004, 8, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H.; Orr, Z. The profession’s response to overt and covert threats to the ruling hegemony. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2024, 34, 240–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H.; Orr, Z.; Maizel, Y. Contested homes: Professionalism, hegemony, and architecture in times of change. Space Cult. 2011, 14, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raichman, S.; Yehudai, M. Survey of Proactive Physical Planning, 1948–1965; Ministry of the Interior, Planning Administration: Jerusalem, Israel, 1984. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sharon, A. Physical Planning in Israel; Government Publisher: Jerusalem, Israel, 1951. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Perry, A.C. The Neighborhood Unit. In Neighborhood and Community Planning: Comprising Three Monographs; Richard, C.W., Ed.; Arno Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 21–140. [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, P. New Towns: Regional Planning and Development; Methuen & Co.: London, UK, 1971; pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Glikson, A. Man, Region, World: On Environmental Planning; Ministry of Housing: Jerusalem, Israel, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, H. Karmiel: A new town in the center of the Galilee. Eng. Archit.—J. Assoc. Eng. Archit. Isr. 1967, 25, 52–66. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ben Sira, Y. Criteria for Evaluating Urban Building and Construction Plans; Ministry of Housing, Association of Engineers and Architects in Israel, Institute for Building Research and Technology: Tel Aviv, Israel, 1968. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Gold, J.R. The Experience of Modernism: Modern Architects and the Future City 1928–1953; Oxford Brooks University: London, UK, 1997; pp. 141–185. [Google Scholar]

- Greater London Council. The Planning of a New Town; Greater London Council: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Shadar, H. The linear city: Linearity without a city. J. Archit. 2011, 16, 727–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glikson, A. (Moderator) Discussion on new towns. Eng. Archit.—J. Assoc. Eng. Archit. Isr. 1964, 22, 2–23. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Paldi, O.; Wolfson, M.; in collaboration with Eldor, S. Searching for New Approaches in Neighborhood Planning; Ministry of Construction and Housing, Department of Urban Planning and Building, Monitoring Research Series: Jerusalem, Israel, 1989. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Krier, R. Urban Space; Academy Edition: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Krier, L. Leon Krier: Architecture and Urban Design 1967–1992; Economakis, R., Ed.; Academy Edition: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Safdie, M.; Cohen, M. Modi’in: The planning story of a city. In Modi’in: The City; Miron, E., Ed.; Yad Ben Zvi: Jerusalem, Israel, 2014; pp. 138–193. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, S. The City as a Rug. Archit. Des. 1994, 9–10, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Safdie Architects Ltd. Modi’in—A New City; Moshe Safdie Architects Ltd.: Jerusalem, Israel, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shinar, A. (Ministry of Construction and Housing, 1990–1991, Tel Aviv, Israel). Personal communication on urban planning concepts in the 2000s and the planning of Modi’in in particular, 2001.

- Kehat, H. (The Planner of the New City of Harish, Haifa, Israel). Personal communication on the Harish ‘s planning concepts and their sources, 2025.

- Mansfeld Kehat Architects Website. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2dctt8pk (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Davidovitz-Marton, R. Master Plan for the City of Harish: Existing Conditions Report—Mapping and Characterization; Ministry of Construction and Housing: Harish, Israel, 2022. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Feld, J.; Shpaizman, Y.; Fromkin, R. Master Plan for Ecological Infrastructure for the City of Harish; Ministry of Construction and Housing: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2020. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ein Gedi-Davidovich, L. Comprehensive Master Plan for Harish, H/3, 3071161603; Government Publisher: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2024. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Laor, M.; Rosner, M.; Raifer, R.; Macrae, M. Master Plan for Be’er Sheva—Interim Report; Government Publisher: Be’er Sheva, Israel, 1965. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Shach-Pinsly, D.; Shadar, H. The Public Open Space Quality in a Rural Village and an Urban Neighborhood: A Re-Examination after Decades. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybczynski, V. The urbanity concept of Modi’in. In Modi’in: The City; Miron, E., Ed.; Yad Ben Zvi: Jerusalem, Israel, 2014; pp. 236–258. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Israel, I. (The First City Engineer of Harish, 2015–2018, Zichron LeZion, Israel). Personal communication on the transformation of the main street into a boulevard, 2018.

- Shalom Horesh (Free Image, Wikimedia). Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%D7%A9%D7%93%D7%A8%D7%9A_%D7%93%D7%A8%D7%9A_%D7%90%D7%A8%D7%A5.jpg (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Pratomo, R.A.; Samsura, D.A.A.; van der Krabben, E. Transformation of local people’s property rights induced by new town development (case studies in Peri-Urban areas in Indonesia). Land 2020, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong WHuang, X.; White, M.; Langenheim, N. Walkability perceptions and gender differences in urban fringe new towns: A case study of Shanghai. Land 2023, 12, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S. Measurement and development of Park Green Space Supply and demand based on community units: The example of Beijing’s Daxing New Town. Land 2023, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Yin, Z.; Drianda, R.P. Living in a Chinese industrial new town: A case study of Chenglingji new port area. Land 2023, 12, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Roh, B. Characteristics of changes in residential building layouts in public rental housing complexes in new towns of Korea. Land 2025, 14, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadar, H. Preservation of Rural Characteristics in Urbanized Villages. Land 2025, 14, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).