Abstract

Exploring the impact of national park construction on county-level livelihood and well-being holds significant implications for enhancing social livelihood. This study treats Wuyishan National Park Construction (WNPC) as a quasi-natural experiment, utilizing panel data from 138 counties (2011–2023) to construct a county-level livelihood and well-being index through the CRITIC weighting method. Kernel density estimation and the Theil index are applied to depict the spatiotemporal dynamics of WNPC. Moreover, the difference-in-differences model and mediating effect model are employed to assess the impact and mechanisms of WNPC on livelihood and well-being. The results reveal that, in the period 2011–2023, livelihood and well-being scores ranged from 0.1329 to 0.4565, indicating considerable scope for improvement. Over time, inter-county disparities narrowed, displaying a spatial pattern of “higher in the east and west, lower in the middle.” Overall disparities remained pronounced, driven chiefly by within-region variation, and Jiangxi displayed notably larger internal gaps than Fujian and Zhejiang. Benchmark regressions confirm that WNPC significantly improved livelihood and well-being, with robust results according to multiple tests. Mechanism analysis indicates that WNPC enhances livelihood and well-being by promoting population mobility and improving infrastructure. Heterogeneity analysis suggests that compared to industrial counties, WNPC has a stronger positive effect on the livelihood and well-being of agricultural counties. Based on this, it is suggested that WNPC promotes population mobility and improves infrastructure construction. This study provides a scientific basis and decision-making reference for achieving high-quality construction of national parks and enhancing livelihood and well-being.

1. Introduction

Livelihood and well-being constitute the foundation of individual happiness and the cornerstone of social harmony []. The report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) clearly emphasizes the imperative to safeguard fundamental interests, enhance public well-being, and pursue development that is by, for, and of the people, thereby ensuring that the fruits of modernization are shared equitably []. Against this backdrop, continuously improving county-level livelihood and well-being is not only essential for fulfilling the fundamental objective of “pursuing happiness for the people” but also represents a pressing and multifaceted challenge in public welfare.

This concept of livelihood and well-being is unique to China. This specific term is not explicitly mentioned in foreign research. Similar concepts include “well-being []”, “social vulnerability []” and “life quality” [], which primarily assess individual happiness, social resilience, or overall quality of life. In the Chinese context, livelihood and well-being comprises two components. The term “livelihood” first appears in Zuo Zhuan: “When the people work diligently, scarcity will not arise.” Its original meaning pertains to the means by which people sustain their lives. In Western societies, livelihood is often measured by employment status [,], embodying the notion of “how one makes a living.” Thus, both Chinese and Western academia understand livelihood as the populace’s means of subsistence. Well-being refers to happiness and welfare, denoting a favorable life condition. The term stems from the translation of the Western concepts “well-being” and “welfare,” the former emphasizing individuals’ subjective psychological experiences of happiness and satisfaction [,], and the latter focusing on objective benefits and social security derived from material conditions such as national income []. Consequently, in the Chinese context, livelihood and well-being not only relate to the assurance of fundamental survival rights but also stress the continual improvement of social rights, reflecting the holistic pursuit of a happy and fulfilling life [].

Livelihood and well-being, as a multi-dimensional concept for measuring an individual’s quality of life, has mainly been studied by scholars from the following three aspects. The first is the conceptual definition of livelihood and well-being. With the rapid development of the economy and society, as well as residents’ yearning for a better life, scholars’ understanding of the concept of well-being has shifted from initially taking GDP or GNP as a single indicator to a multi-dimensional vision of a better life that encompasses economy, society, environment, and culture []. Smith et al. proposed that well-being is a concept used to assess the state of individual happiness, encompassing multiple dimensions such as material living conditions, health status, and interpersonal relationships []. The second aspect is the measurement of the level of livelihood and well-being. According to different measurement methods, livelihood and well-being are categorized into subjective and objective well-being. Subjective well-being emphasizes psychological experiences such as an individual’s sense of happiness [], life satisfaction [], and perceived fairness []. Relatively speaking, objective well-being can be measured by a single or multiple objective indicators, such as the Human Development Index (HDI) [], the Comprehensive Human Development Index [], and the Gross National Happiness Index [], with studies conducted at various spatial scales including the provincial [], municipal [], county [], and river basin []. Both subjective and objective well-being indices focus primarily on individuals and do not fully capture the multi-dimensional connotations of livelihood and well-being that are closely related to the people’s situation. The third aspect includes research on regional disparities in livelihood and well-being and their spatial distribution characteristics. With the continuous development of China’s economy and society, levels of livelihood and well-being exhibit marked regional variations. Some scholars have utilized the HDI to examine the development gaps among different regions in China and to analyze the temporal evolution of their spatial patterns [,].

The concept of “national park” was first proposed in 1832 by American artist George Catlin. During his explorations of the American West, he witnessed the destruction of indigenous cultures and natural landscapes and conceived the idea of establishing protected reserves to safeguard local communities’ living environments. Although his proposal received little attention at the time, it laid the essential groundwork for future national parks. In 1872, the United States formally established Yellowstone National Park as the world’s first national park, defining a national park as “a large natural area, rich in natural resources, sometimes including historical sites, where hunting, mining, and other exploitative activities are prohibited.” From that point onward, the national park concept spread globally, and countries such as Australia, Japan, and the United Kingdom adapted it according to their own national contexts. In 1879, Australia established the world’s second national park, the Royal National Park, with the purpose of promoting “public health, recreation, comfort, and enjoyment” by providing urban residents with leisure spaces. In 1934, Japan designated the Setonaikai, Unzen, and Kirishima areas as its first three national parks, defining them as regions aimed at “protecting significant natural landscapes and ecosystems while promoting environmental education, recreation, and cultural tourism.” These protections extended beyond natural features such as volcanoes, coastlines, and hot springs to include landscapes and customs associated with traditional culture. Unlike the American model, which prioritizes wilderness protection, the United Kingdom’s national parks emphasize harmonious coexistence between people and nature. In 1949, England and Wales established their national park system under the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act, defining a national park as “an area designated to conserve natural beauty and promote public recreation and enjoyment, while respecting and sustaining the lifestyles of local communities.” In 1994, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) introduced its “Protected Area Categories System,” classifying protected areas into six categories based on global conservation practices. National parks were placed in Category II, second only to strict nature reserves and wilderness areas, being defined as large natural or near-natural areas designated to protect large-scale ecological processes, species, and ecosystems, while also providing spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational, and visitor opportunities in harmony with environmental and cultural contexts [].

Although China has successively established various types of protected areas such as nature reserves and forest parks, classified according to conservation targets under the nature reserve system, the absence of unified classification standards and technical specifications has resulted in fragmented administration and haphazard development []. To address these challenges, in November 2013, China formally proposed establishing a national park system as a key institutional innovation to promote ecological civilization. In 2015, China launched the first batch of ten national park system pilot sites, including Sanjiangyuan and Wuyishan. In 2017, China promulgated the Overall Plan for Establishing a National Park System (the “Plan”), which stipulated that the pilot phase should be substantially completed by 2020. The Plan states that a national park is a specific terrestrial or marine area approved and managed by the state, with clearly defined boundaries, aimed primarily at protecting representative large-scale natural ecosystems and ensuring the scientific conservation and rational use of natural resources []. The two definitions differ in their applicable standards. International national parks (IUCN Category II protected areas) maintain large-scale ecological processes and biodiversity through clear boundaries and strict management, offering low-intensity recreational activities within this framework. In contrast, China’s national parks maintain these conservation and recreation functions and further emphasize the scientific protection and rational utilization of nationally representative ecosystems, while also incorporating research, education, and community development. Therefore, in this study, we define “national park construction” as a systematic project initiated upon policy approval, grounded in natural resource property rights and systematic conservation theory, and implemented through spatial planning, institutional design, resource control, and supporting measures to achieve effective protection and sustainable use of natural ecosystems via integrated management and tiered operational mechanisms. The Plan further emphasizes that national parks bear significant responsibilities for nature conservation. The term “national” not only denotes public ownership but also reflects the intrinsic public-interest character of national park []. According to the different protected objects, national parks can be divided into two major types. One of these types is represented by flagship-species conservation parks, which have mainly been established to protect rare and endangered species [], such as the Giant Panda National Park and the Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Park. The second type is the geographic-unit conservation parks, whose aim is to maintain the authenticity and integrity of the natural ecosystems within a given area [], such as Sanjiangyuan National Park, Wuyishan National Park, and Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park. Research has shown that approximately 60% of ecosystems are being severely damaged by human activities [], making it difficult to meet the demands of human production and life.

As global ecological governance advances, the construction of national parks has emerged as a critical strategy for reconciling ecological protection with social development and fostering harmonious human–nature coexistence. At the societal level, national park construction can enhance overall social well-being by strengthening environmental awareness among residents and encouraging broad community participation, thereby improving both interpersonal relationships and human–nature interactions [,]. Influenced by early absolute protectionism, many parks initially adopted the “isolation protection” model, cutting off close connections with the surrounding communities, resulting in the contradiction between ecological protection and community development becoming increasingly prominent. With the rise of the concept of development cooperation, management strategies have gradually shifted to a new model that emphasizes both protection and utilization, paying more attention to the development of surrounding communities and respecting local traditional culture.

Against this backdrop, a growing body of scholarship has examined the social impacts of national park construction, focusing on three main areas. First, studies have investigated the effects of national park construction on farmers’ livelihood capitals and strategies. For example, Kumar et al. conducted semi-structured interviews with 150 households around Jim Corbett National Park, India, and applied the range-equalization method to derive livelihood capital scores including human and natural capital, revealing that tourism development and forest resource use significantly bolster local livelihood security []. Li et al. surveyed 329 farmers and herders in Qilian Mountain National Park, China, and used one-way ANOVA and ordinary least squares regression to assess how livelihood strategies at different stages of park development influence well-being, finding that diversified strategies significantly improved subjective well-being following park construction []. However, due to limitations in research timeframes and data availability, most of these studies are case-based and lack systematic theoretical summaries and generalizations. The second area of research considers the impact of national park construction on the sustainable livelihoods of community residents. Unlike earlier studies that focused solely on farmers’ livelihood strategies, Karki systematically examined the combined impact of national parks and conservation incentives on the livelihood capital and livelihood strategies of residents in surrounding communities, using a sustainable livelihood approach (SLA) []. The third area of research refers to the behavioral intentions of community residents. Jia et al. conducted field investigations and combined planned behavior theory and structural equation models to analyze the impact of behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control on the willingness of community residents to participate in park construction []. Building on this, Dong introduced a livelihood capital perspective and used structural equation modeling to demonstrate that both attitudes and subjective norms among farmers near Nanling National Park significantly drive conservation intentions, with financial and social capital exerting direct positive effects []. Furthermore, Puhakka et al. used questionnaire surveys to show that national park initiatives, by offering ecological experiences and environmental education, effectively enhance public awareness and participation in conservation, thereby generating broader social benefits [].

The literature review reveals that although the above-mentioned studies [,,,,,] have explored the livelihood well-being and social impacts of national park construction, there are still three deficiencies. Firstly, the research perspectives are relatively narrow. The existing research on national parks mainly focuses on the impact of residents’ livelihoods and behavioral intentions, while the systematic exploration of multi-dimensional livelihood and well-being in county areas is still insufficient. Secondly, there is a lack of long-term research. The aforementioned studies [,] are based on short-term survey data and lack a dynamic assessment of the long-term social impact of national park construction. Thirdly, the mechanisms of action remain inadequately understood. The internal mechanisms by which the construction of national parks affects county-level livelihood and well-being through different paths still need further research.

National parks bear not only the responsibility of conserving natural ecosystems and preserving biodiversity, but also the mission of safeguarding livelihood and well-being. Wuyishan National Park—China’s only national park that is both a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and a UNESCO World Cultural and Natural Heritage site—contains the most intact, most representative, and largest mid-subtropical forest ecosystem at its latitude in the world. In 2016, the National Development and Reform Commission officially approved the Pilot Implementation Plan for the Wuyishan National Park System, thereby initiating its full-scale pilot phase. However, as a typical southern collective forest region with a high proportion of collectively owned forest land, the park’s tea, bamboo, and tourism sectors heavily depend on natural resources. The diversity and complexity of forest management regimes, coupled with a heterogeneous stakeholder landscape, have exacerbated tensions between ecological conservation objectives and the development needs of adjacent communities [], mainly manifested as problems such as restricted land use, restricted traditional livelihood methods, and insufficient community participation. Consequently, striking a balance between conservation and development while ensuring the stability and enhancement of livelihoods and achieving harmonious coexistence between humans and nature has become a critical issue that must be addressed. In this context, whether Wuyishan National Park construction (WNPC) generates enhancement effects on county-level livelihood and well-being has not yet been empirically verified. What temporal and spatial characteristics and disparities do county-level livelihood and well-being exhibit? What impact does WNPC exert on these dynamics? What underlying mechanisms drive such effects? And how can we maximize the livelihood and well-being benefits conferred by Wuyishan National Park? The above-mentioned problems urgently need further research and discussion.

On this basis, grounded in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment’s human well-being framework, this study develops a comprehensive evaluation index system for county-level livelihood and well-being from three dimensions: basic material well-being, security and health well-being, and socio-cultural well-being. Treating national park construction as a quasi-natural experiment, this study utilizes panel data from 138 counties in Fujian, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang provinces from the period 2011–2023, and employs the difference-in-differences (DID) model to assess its impact on county-level livelihood and well-being. This study is of great theoretical and practical significance for scientifically evaluating the implementation effectiveness of the national park system and promoting the coordinated development and improvement of ecological conservation and livelihood.

2. Materials and Methods

This part of the current study adopts a quasi-natural experiment framework to systematically develop a comprehensive research design, thereby laying a solid foundation for the empirical analysis in Section 3. Section 2.1 develops a theoretical framework of national park construction’s impact on county-level livelihood and well-being, based on growth pole theory and new economic geography theory. Section 2.2 describes the study area, emphasizing the principles and methods for selecting and classifying the treatment and control groups. Section 2.3 details the model construction, first applying the CRITIC weighting method to measure the county-level livelihood and well-being evaluation index system, then employing the Theil index to depict spatial disparities in well-being, and finally, constructing the DID model to examine the impact mechanism of national park construction with regard to livelihood and well-being. Section 2.4 outlines the selection of relevant variables and provides a description of the datas, and Section 2.5 specifies the data sources.

2.1. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

As an integral component of China’s ecological civilization strategy, national park construction contributes to the improvement of county-level livelihood and well-being from the following three aspects. First, national park construction helps improve residents’ basic material well-being. By promoting the development and sustainable utilization of ecological resources, it expands employment opportunities and facilitates the efficient flow and optimal allocation of production factors within the region. This, in turn, alleviates resource misallocation, enhances productivity, and provides local residents with stable income sources and social security, thereby fostering income growth and social wealth accumulation. Second, national park construction contributes to the improvement of residents’ security and health well-being. Through the implementation of strict ecological protection measures, it effectively improves regional environmental quality, including cleaner air, purer water, and healthier soils, thereby creating a safer and healthier living environment that supports residents’ social integration []. Meanwhile, national parks advocate healthy lifestyles. By integrating their unique environmental education functions and organizing ecological science popularization activities, environmental protection lectures and nature experience courses, they further enhance residents’ environmental awareness and health literacy, ultimately improving overall quality of life []. Third, national park construction enhances residents’ socio-cultural well-being. As vital platforms for cultural inheritance and social interaction, national parks foster a stronger sense of social identity and cultural pride among residents by preserving local cultural heritage, promoting ecological and cultural tourism, and encouraging broad-based community participation. Based on the above, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

The construction of national parks significantly enhances county-level livelihood and well-being, generating multiple dividend effects.

Based on growth pole theory, during the initial stage of national park construction, governments typically deploy fiscal subsidies such as ecological compensation and industrial support to cultivate green industrial clusters (e.g., ecotourism and under-forest economy). This strategy generates numerous employment opportunities in tourism, services, research, and environmental protection, thereby attracting in-migration to areas surrounding the park. Population agglomeration not only expands the local labor market and raises employment rates and income levels [] but also increases fiscal revenue and subsidy allocations, providing a financial foundation for upgrading public services in education, healthcare, and culture. Additionally, ancillary sectors such as catering, accommodation, and transportation flourish, creating new consumption growth points. Collectively, these pathways significantly enhance county-level livelihood and well-being. However, as national park construction advances, the ecological carrying capacity of the core protection zone gradually approaches saturation, potentially leading to diseconomies of scale. In response, park authorities have implemented measures such as ecological resettlement to stimulate the diffusion of production factors [], encouraging segments of the population to migrate from the core zone to peripheral areas. This strategy not only alleviates demographic pressure within the core but also fosters optimized resource allocation and balanced development in adjacent regions, thereby enhancing county-level livelihood and well-being. Specifically, following the orderly relocation of residents from the core protection zone, park management agencies planned and constructed visitor reception centers, ecological monitoring stations, and supporting service facilities in the general control zone, effectively extending infrastructure and management functions previously confined to the core. This approach guides broader spatial flows of labor and capital, optimizes intra-county factor distribution, and reduces well-being disparities between central and peripheral communities. Based on the above, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

By altering county-level population mobility patterns and harnessing both agglomeration and dispersion effects, national park construction significantly enhances county-level livelihood and well-being.

National parks provide non-excludable and non-rival public ecological services, with the overarching aim of achieving high-level conservation and high-quality development. Infrastructure construction constitutes essential material support for realizing these goals. The theory of new economic geography posits that infrastructure construction can effectively reduce spatial barriers, enhance the mobility of factors, and promote economic connections and market integration both within and outside the region, thereby improving the quality of life of residents and enhancing county-level livelihood and well-being []. Before the pilot phase, the park region and its surrounding counties consisted of remote mountainous areas with predominantly unpaved roads, severely restricting local residents’ daily mobility and living standards, as well as hindering ecological monitoring and scientific research. After the pilot launch, areas with well-developed infrastructure can leverage existing transport and communication networks to rapidly expand tourism and related service industries. This not only generates additional employment opportunities and elevates the provision of public services but also materially improves residents’ living conditions. Moreover, optimized infrastructure enhances regional accessibility and attractiveness, lowers travel costs, and facilitates the convenience of daily life and work, thereby promoting population mobility and efficient resource allocation, which further drives gains in livelihood and well-being. Based on the above, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

National park construction significantly enhances county-level livelihood and well-being by improving regional infrastructure, facilitating factor mobility, and elevating the level of public service.

Due to the differences in the functional positioning of counties, the implementation effects of national parks exhibit significant heterogeneity among different types of counties. Agricultural counties are characterized by agriculture as the primary industry. The construction of national parks has significantly improved the local ecological environment quality by strengthening ecological protection and restoring the natural environment, providing sustainable resource guarantees for agricultural production and driving the increase of farmland productivity, thereby raising farmers’ incomes and livelihood standards. In contrast, industrial counties depend on secondary industry for economic development. Their industrial activities often exacerbate environmental issues such as soil erosion and air pollution and can temporarily undermine residents’ quality of life. Moreover, industrial counties are under considerable ecological pressure and the difficulty of environmental governance is relatively high. Therefore, the effect of national park construction on the livelihood and well-being in such areas may be difficult to manifest. Based on above, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

The effect of national park construction on enhancing county-level livelihood and well-being exhibits heterogeneity across counties with different functional positioning.

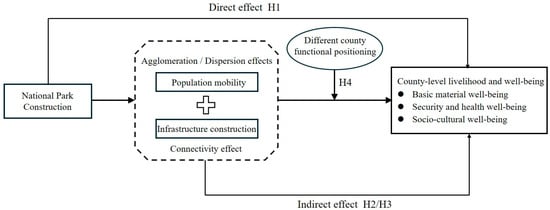

To sum up, the theoretical framework depicting the impact of national park construction on county-level livelihood and well-being is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of the impact of national park construction on county-level livelihood and well-being.

Following the theoretical analysis and hypothesis development, this study delineates its research area and clarifies the criteria for classifying the treatment and control groups.

2.2. Study Area

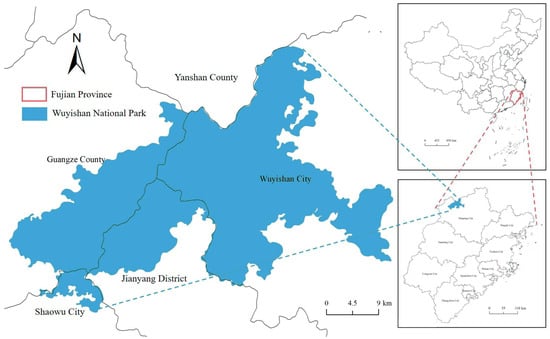

Situated in northern Fujian Province and adjacent to Yanshan County in southern Jiangxi, Wuyishan National Park spans four administrative divisions of Nanping City—Jianyang District, Shaowu City, Wuyishan City, and Guangze County—covering a total area of approximately 1001.41 km2 (Figure 2). The park operates under a management model where the central government entrusts provincial governments. Through the institutional arrangement of personnel coordination and cross-appointment, a multi-level collaborative governance system has been established involving provincial, municipal, and township government departments as well as the National Park Administration.

Figure 2.

Location Map of Wuyishan National Park.

In 2021, the State Council approved the formal establishment of Wuyishan National Park. Building on the pilot initiative, the Jiangxi Wuyishan National Nature Reserve and Ehu Mountain National Forest Park in Yanshan County were integrated into the park system. Therefore, the policy implementation is considered to have commenced in 2016. Given the later inclusion of the Jiangxi region (Yanshan County), the treatment group comprises Jianyang District, Shaowu City, Wuyishan City, and Guangze County. Following Yang et al. [], this study used ArcGIS 10.7 to identify counties within a 300-km radius from Nanping City as the sample. After excluding areas already included in other national park construction and accounting for county-level data availability, 134 non-pilot counties were selected as the control group.

After determining the sample scope, this study presents a comprehensive and detailed description of the model construction process.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. CRITIC Weighting Method

The Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC) method is an objective weighting approach first proposed by Diakoulaki et al. []. It assigns weights to indicators by evaluating both the degree of conflict among them and the amount of information each conveys. Specifically, a high correlation coefficient between two indicators implies a lower level of conflict, while a larger standard deviation of a single indicator indicates that it contains more information. The CRITIC method simultaneously takes into account both the dimensions of correlation and information volume, with strong scientificity and rationality determining the weight distribution []. The calculation steps are as follows:

- (1)

- Data Standardization

Suppose there are evaluation objects and evaluation indicators, forming an original data matrix .

For positive indicators, the standardized value is calculated as follows:

For negative indicators, the standardized value is calculated as follows:

- (2)

- Calculation of Information Content

Step 1: Calculate the contrast intensity of indicator , as follows:

Step 2: Calculate the conflict between indicators. Let denote the conflict degree of indicator with all other indicators, defined as follows:

where represents the Pearson correlation coefficient between indicator and indicator .

Step 3: Calculate the information content, as follows:

- (3)

- Calculation of Weights and Scores

The calculation of weights uses the following formula:

The calculation of scores is as follows:

2.3.2. Theil Index

The Theil index is commonly used to assess income disparities between individuals or regions. Recently, it has been widely applied in the research of regional development differences [,]. In this study, the Theil index was employed to analyze disparities in livelihood and well-being across three major regions—Fujian, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang—as well as among the 138 counties within these provinces. The objective was to characterize the spatial distribution and variation of livelihood and well-being across these regions. The calculation formula is as follows:

where represents the total number of counties; represents the number of regional groups, that is, the study area is partitioned into three regions according to provincial boundaries. denotes the livelihood and well-being index in the -th county. indicates the average value of livelihood and well-being index across all counties; is the proportion of counties in that region; is the ratio of the average level of livelihood and well-being within each area to the average level of livelihood and well-being in the study area; stands for Theil index; is the intra-group Theil index; is the inter-group Theil index; denotes the Theil index measuring disparities in county-level well-being within a specific region.

2.3.3. DID Model

The DID model is commonly used to evaluate the intertemporal effects of policy interventions. Its basic principle is to infer the actual impact of the policy by comparing changes in dependent variables when the policy is implemented and not implemented, through a counterfactual framework [,]. To overcome the endogeneity problems caused by omitted variables in traditional regression analysis, this study adopts the DID model to systematically evaluate the impact of WNPC on county-level livelihood and well-being. The specific model is constructed as follows:

where and denote the county and the year, respectively, and represents county-level livelihood and well-being; represents the interaction term between the grouping dummy variable and the staging dummy variable for implementing the national park policy; is the treatment effect that represents the difference in county-level livelihood and well-being between the treatment group and the control group following policy introduction. represents a group of control variables that affect county-level livelihood and well-being; represents the regional fixed effect; is the time fixed effect; is the random error term.

Having completed the model construction, the definitions and measurement standards of the relevant variables are introduced.

2.4. Variable Definitions

- (1)

- Dependent variable (): Livelihood and well-being refer to the various conditions and facilities provided by society to improve the quality of human life. As societies evolve, the connotation of livelihood and well-being has expanded from merely ensuring basic survival rights such as food and clothing to pursuing multiple aspects including social security, medical care and health, education, freedom, and spiritual enrichment []. Drawing on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the SDGs, and the human well-being framework of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, and considering regional characteristics and data availability, this study constructs a county-level composite evaluation index system for livelihood and well-being from three dimensions: basic material well-being, security and health well-being, and socio-cultural well-being (Table 1). Basic material well-being, classified as a low-level need, measures the extent to which individuals can meet the essential conditions for survival, including income level, consumption level, productive capacity, and living capability. Security and health well-being, also considered a lower-order need, reflects the degree to which individuals’ needs for stability, safety, and freedom from long-term anxiety are met; this dimension includes indicators such as food security, healthcare, and ecological safety. Socio-cultural well-being, as a higher-level need, relates to interpersonal relationships, self-esteem, and social recognition; its assessment thus evaluates the realization of individual potential. It includes indicators such as social welfare, education level, employment level, and spiritual culture. The specific variables and definitions are detailed in Table 1. As a critical dimension of regional ecological security, water pollution directly affects community health and livelihood security through pathways such as drinking water and agricultural irrigation []. Given the lack of water pollution emission data in China County Statistical Yearbooks, this study follows the approach of Yang et al. [] by constructing a proportional coefficient based on the ratio of county-level GDP to that of the corresponding prefecture-level city. This coefficient is then applied to disaggregate prefecture-level industrial wastewater discharge data to the county level, thereby estimating county-level industrial wastewater emissions. Furthermore, to enhance the reliability of the results, the CRITIC method is employed to calculate livelihood and well-being indices for 138 counties from 2011 to 2023.

Table 1. Variable settings and descriptions.

Table 1. Variable settings and descriptions. - (2)

- Independent variable (): This is the interaction term between the grouping dummy variable and the staging dummy variable for the policy. The grouping dummy variable equals 1 for counties within the Wuyishan National Park pilot (Jianyang District, Shaowu City, Wuyishan City, and Guangze County) and 0 for all other counties. The staging dummy variable equals 0 for years before pilot implementation (pre-2016) and 1 for 2016 and subsequent years.

- (3)

- Mediating variables: a. population mobility rate ()): This study considers population mobility across districts and counties. Drawing on the research of Guo and Yu [], it adopts (the resident population at the year-end − the registered population)/the registered population as the measurement index. A negative indicates population outflow, whereas a positive indicates population inflow. Moderate population mobility optimizes urban–rural integration and resource allocation and enhances social cohesion and residents’ sense of belonging.b. Infrastructure construction (): The logarithm of the domestic highway mileage is adopted as the measurement indicator. A well-developed highway infrastructure can shorten the spatial distance between urban and rural areas, improve residents’ travel convenience, and ultimately enhance their quality of life and overall well-being.

- (4)

- Control variables: To avoid endogeneity arising from omitted variables, this study incorporates control variables informed by relevant literature [,]. Economic development level () is depicted by the natural logarithm of GDP. The degree of government intervention () is defined as the ratio of local government budgetary expenditure to GDP. Openness level () is depicted by the ratio of foreign capital actually utilized to GDP. Urbanization rate () is expressed by the ratio of the urban population to the resident population at the year-end. Descriptive statistics for these variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive statistical analysis of variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistical analysis of variables.

Following measurement of the variables, this study provides a detailed account of data sources to ensure the reliability of the empirical analysis.

2.5. Data Sources

This study analyzes a panel of 138 counties in Fujian, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang provinces from 2011 to 2023. The data were primarily obtained from the China County Statistical Yearbook, China City Statistical Yearbook, as well as the statistical yearbooks of the respective provinces, prefecture-level cities, and district, statistical bulletins on the national economic and social development of districts and counties, and government work reports. The PM2.5 concentration data were derived from the China High Air Pollutants (CHAP) dataset, a high-resolution, high-quality near-surface air pollutant dataset released by the team led by Dr. Wei Jing and Professor Li Zhanqing at the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. Missing observations were imputed using linear interpolation.

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Patterns of County-Level Livelihood and Well-Being

3.1.1. Temporal Evolution of County-Level Livelihood and Well-Being

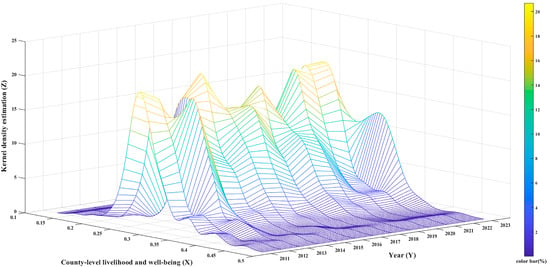

This study employed kernel density estimation to examine the temporal evolution of county-level livelihood and well-being (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3, the overall kernel density curves exhibit a rightward shift with a noticeable “long-tail” effect. The peak of the distribution occurs on the left, indicating that the majority of counties have medium-to-low levels of livelihood and well-being. However, the overall trend demonstrates gradual improvement over the study period. From 2011 to 2021, the kernel density curves displayed an increasingly pronounced and rising main peak, indicating a progressive reduction in the dispersion of regional livelihood-well-being levels and, consequently, a narrowing of absolute disparities among counties. However, in 2022–2023 the main peak’s height receded from its earlier high and its profile transitioned from sharp to more flattened, suggesting that absolute differences in county-level livelihood and well-being experienced a modest widening during this latter period.

Figure 3.

Temporal characteristics of livelihood and well-being in 138 districts and counties.

X denotes the composite county-level livelihood and well-being score, ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 (unitless). Y represents the temporal dimension, ranging from 2011 to 2023 (unit: year). Z indicates the kernel density estimation, characterizing the relative density of observations at different well-being levels (unitless).

3.1.2. Spatial Evolution of County-Level Livelihood and Well-Being

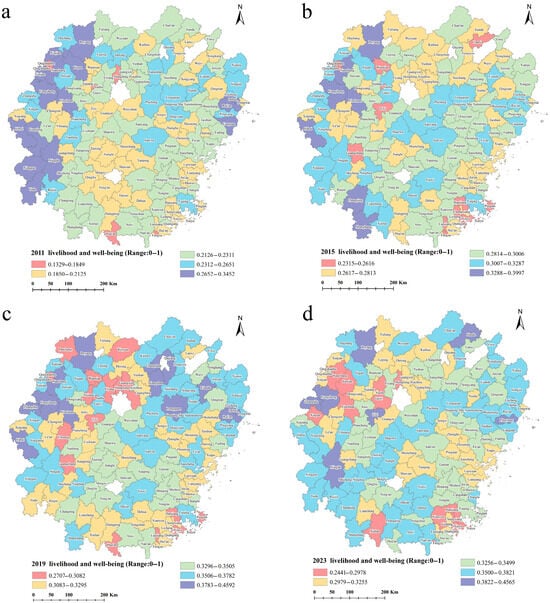

To illustrate spatial distribution patterns of livelihood and well-being, we used ArcGIS 10.7 and the natural breaks method to categorize 138 counties into five levels—low, relatively low, moderate, relatively high, and high. Four representative years—2011, 2015, 2019, and 2023—were selected for spatial visualization and analysis (Figure 4). The results reveal significant spatial disparities in county-level livelihood and well-being, with a clear pattern of “higher in the east and west, lower in the center.” From a spatial perspective, in 2011, the overall level of livelihood and well-being in the study area was relatively low, with only 36 counties classified as “relatively high” or “high,” accounting for 26.09% of the total. Most areas fell into the “relatively low” and “moderate” categories, particularly in parts of the northern and southeastern regions, where well-being levels were noticeably low. By 2015, the region’s overall livelihood and well-being had risen markedly, with counties exhibiting relatively high and high well-being levels progressively spreading eastward and southward; although the rate of increase remained pronounced, it began to decelerate overall. In 2019, livelihood and well-being continued its upward trajectory, with counties at relatively high and high levels shifting from a dispersed pattern toward concentration in central locations; the number of high-well-being counties rose to 50, markedly increasing their share. By 2023, the study area exhibited a widespread advancement in livelihood and well-being, resulting in a spatial structure characterized by “central agglomeration and peripheral lag.”

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution characteristics of livelihood and well-being in 138 districts and counties. (a) Spatial distribution of livelihood and well-being in 2011; (b) Spatial distribution of livelihood and well-being in 2015; (c) Spatial distribution of livelihood and well-being in 2019; (d) Spatial distribution of livelihood and well-being in 2023.

3.1.3. Spatial Disparities of County-Level Livelihood and Well-Being

To examine regional disparities and temporal dynamics in livelihood and well-being, we computed the Theil index for 138 counties from 2011 to 2023 (Table 3). Table 3 shows that the Theil index values remained low and declined steadily from 0.0091 in 2011 to 0.0024 in 2022. This trend indicates that disparities in livelihood and well-being among counties have been gradually narrowing over time. However, in 2023, the index rebounded to 0.0043, suggesting a modest widening of inter-county well-being differences during this period.

Table 3.

Theil index and contribution rates of county-level livelihood and well-being.

Building on the overall Theil index calculation for livelihood and well-being, we further examined intra-regional disparities. To achieve this, the 138 counties were grouped into three sub-regions—Fujian, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang—and the overall Theil index was decomposed to obtain the contribution rate of each sub-region’s internal disparities. Table 3 indicates that the overall inter-county disparities in livelihood and well-being are mainly attributed to intra-regional differences within the three provinces. The contribution of internal disparities consistently exceeds 82%, peaking at 99.58% in 2022. This demonstrates that significant internal disparities exist in livelihood and well-being levels within the study area. Notably, Jiangxi exhibits markedly higher internal disparities than Fujian and Zhejiang, indicating a more pronounced imbalance in county-level livelihood and well-being within Jiangxi.

3.2. Parallel Trend Test

When using the DID model to evaluate policy effect, a key prerequisite is that the treatment and control groups satisfy the parallel trends assumption; that is, prior to the implementation of the national park policy, there should be no significant differences in the trajectory of changes in livelihood well-being between the two groups. To this end, this study follows the approach of Jacobson et al. [], adopting an event-study framework to test for parallel trends and taking the year before the policy shock as the baseline (2015). We selected the time window from five years before the approval of WNPC to four years after it, and constructed the following model:

where denotes the approval year for WNPC, namely 2016. ranges from −5 to 4, representing five years before through four years after approval. Other variable definitions are identical to those in Model (12).

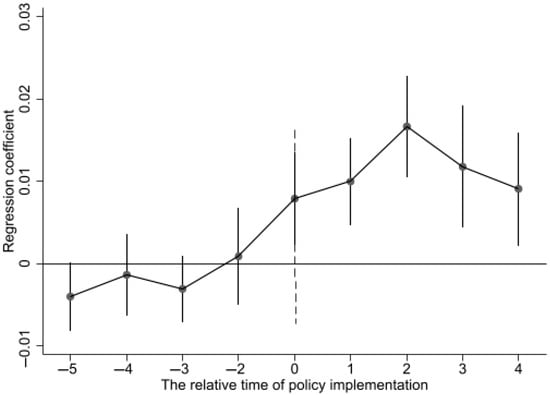

Figure 5 presents the parallel trends test results, with the horizontal axis denoting policy timing () and the vertical axis showing the estimated treatment effect coefficients. Prior to implementation, all estimated coefficients had 95% confidence intervals that included zero, indicating that the trends in livelihood and well-being levels between the treatment and control groups were generally consistent before WNPC, thereby satisfying the parallel trends assumption. Following the 2016 policy shock, coefficients become significantly positive at several time points, indicating that WNPC has yielded a significant and sustained positive impact on regional livelihood and well-being.

Figure 5.

Parallel trend test. Note: The solid line represents the estimated coefficients for each year relative to policy implementation, with the vertical bars denoting the 95% confidence intervals. The dashed vertical line at time = 0 marks the point of policy implementation.

3.3. Benchmark Regression Results

Table 4 presents the benchmark regression results of the impact of WNPC on the county-level livelihood well-being. The independent variable is significantly positive in both columns of regression, indicating that WNPC has a significant promoting effect on the well-being. Specifically, in Column (1), which omits control variables, the coefficient on is 0.0066 and significant at the 1% level. In Column (2), after including controls (, , , ), the coefficient declines marginally to 0.0061 and remains significant at 1%, demonstrating the robustness of the result. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported. In this process, WNPC has improved the ecological environment and enhanced residents’ quality of life and sense of security through implementing stringent forest protection and ecological restoration measures. Simultaneously, green industries such as ecotourism and under-forest economy have been vigorously developed, thereby creating additional employment opportunities and income sources for local residents, further enhancing county-level livelihood and well-being.

Table 4.

Benchmark regression results.

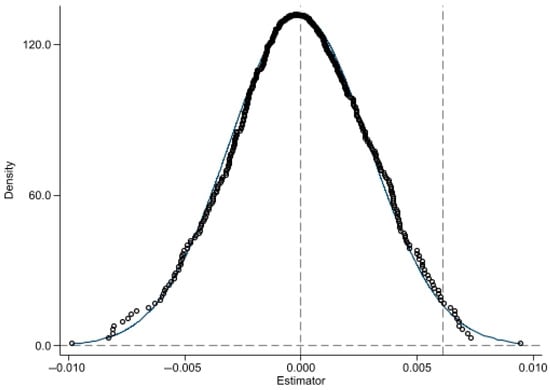

3.4. Placebo Test

To address potential bias from omitted variables, we followed La Ferrara et al. [] and Li et al. [] by conducting placebo tests through randomized experiments. Specifically, some areas were randomly selected as the construction locations of Wuyishan National Park, and their construction times were immediately set. Based on this, a two-layer (time–region) random trial of virtual policy implementation was constructed. Subsequently, regression was conducted based on Column (2) of Table 4, and the probability of the occurrence of the benchmark regression estimation coefficient was calculated through false experiments to verify the reliability of the conclusion. To enhance robustness, this study repeated the above process 500 times, finally obtaining the placebo test results shown in Figure 6. Figure 6 shows that the kernel density distribution map of the coefficients is symmetrically distributed with the vertical axis as the center. Furthermore, the values of the coefficients are mainly concentrated around 0, and most of the p-values are higher than 10%, indicating that the estimation results of the random samples are not significant. The value corresponding to the dotted line in the figure is 0.0061, which is the coefficient of the actual policy dummy variable. However, few placebo coefficients exceed 0.0061, and the probability of their occurrence is very low. These findings suggest that the possibility of the research conclusion being affected by unobservable factors is relatively small, thereby confirming the robustness of the estimation results.

Figure 6.

Placebo test results. Note: Open circles denote the p-values of the virtual estimation coefficient; the solid line shows the probability density curve of these coefficients; the horizontal line marks the 10% significance level; the vertical dotted line indicates the actual estimated coefficient.

3.5. Robustness Tests

3.5.1. PSM-DID

The selection of national park construction is not a completely random process, but is carried out based on the basic principle of “national representativeness, ecological importance and management feasibility”, which may introduce selection bias. To avoid the endogeneity problem caused by the possible non-random selection of the policy itself, this study draws on the approach of Heckman et al. [] to re-estimate the benchmark regression model using propensity score matching difference-in-differences (PSM-DID). The specific steps are as follows. The first step was to calculate the propensity scores of each region using the Logit model to estimate the probability of policy implementation. The second step was to select control variables such as , , , and from the benchmark regression model as covariants to control the initial characteristic differences among samples. The nearest-neighbor matching method and the Mahalanobis-distance matching method, respectively, were adopted for matching to ensure that the treatment group and the control group had a high similarity before the policy implementation. The third step was to conduct DID estimation on the matched sample data to identify the causal effect of WNPC on the county-level livelihood well-being. The results are shown in Table 5. In both matching specifications, the coefficient on remained significantly positive. This finding confirms that, even after controlling for selection bias, park construction exerts a robust positive effect on county-level livelihood and well-being.

Table 5.

Estimated results of PSM-DID.

3.5.2. Exclude Interference from Other Policies

To avoid the impact of WNPC on county-level livelihood and well-being being disturbed by other policies during the same period resulting in incorrect estimation results, and considering that the opening of the high-speed railway (HSR) may have had a positive impact on the economic development, tourism, employment opportunities and other aspects of the areas along the line [], thereby improving the well-being of the residents, this part of the current study focuses on the potential impact of the Hefei–Fuzhou HSR. As an important part of China’s “Eight Verticals and Eight Horizontals” HSR network, the Hefei–Fuzhou HSR plays a crucial role in connecting the East China region with the southeast coast. It was officially put into operation on 28 June 2015. In this context, in this study, the districts (counties, cities) along the Hefei–Fuzhou HSR were assigned a value of 1, and the rest were assigned a value of 0. The dummy variable () of the HSR’s opening was added to the benchmark model for re-regression to evaluate the impact of WNPC on county-level livelihood and well-being. Column (1) of Table 6 shows that after adding the , the regression coefficient of is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating the positive impact of WNPC on county-level livelihood and well-being persists after controlling for the effects of the Hefei–Fuzhou HSR.

Table 6.

Robustness tests.

3.5.3. Eliminate Interference from Special Events

China experienced the COVID-19 outbreak with corresponding containment measures from 2020 to 2022, which may have influenced county-level livelihood and well-being and introduced bias [,]. This study excluded the samples from 2020, 2021, and 2022, and re-regressed the benchmark model. Column (2) of Table 6 show that, after omitting the pandemic period, the coefficient on remains positive and significant at the 1% level, with only a negligible difference of 0.0003 compared with the full-sample estimate. This result confirms that WNPC continues to significantly enhance county-level livelihood and well-being, further validating the robustness of our findings.

3.5.4. Lagged One-Period Test of Control Variables

In regression analysis, there may be a reverse causal relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable, thereby triggering potential endogeneity problems. To effectively solve this problem and enhance the credibility of the estimation results, we introduced a one-period lag for all control variables and re-estimated the model. Column (3) of Table 6 shows that, with controls lagged by one period, the positive effect of WNPC on county-level livelihood and well-being remains statistically significant, further corroborating the robustness of our benchmark regression results.

3.6. Mediating Mechanism Analysis

To validate the mechanisms outlined above and to investigate whether WNPC enhances county-level livelihood and well-being through population mobility and infrastructure construction while addressing the limitations of stepwise mediation tests, this study adopts the approach of Jiang [] and building on Equation (12), specifies the mediating effect model presented in Equation (14):

where represents the mediating variables, namely population mobility and infrastructure construction, respectively. The remaining variables are consistent with the definitions in the previous text.

Table 7 presents the mediation analysis results. Column (1) reports the benchmark regression, while Columns (2) and (3) estimate the effects of park construction on population mobility and infrastructure construction, respectively. In Column (2), the coefficient for is positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that WNPC, by improving the ecological environment and creating employment opportunities, has strengthened regional attractiveness and encouraged net in-migration. The existing literature shows a positive association between population mobility and livelihood and well-being []. Therefore, our findings further demonstrate that WNPC significantly enhances county-level livelihood and well-being through its promotion of population mobility, thereby validating Hypothesis 2. In Column (3), the coefficient for is also positive and statistically significant, indicating that WNPC has actively contributed to local infrastructure construction. Since enhanced infrastructure is known to significantly improve regional livelihood and well-being, we infer that WNPC optimizes public services and elevates residents’ quality of life by upgrading infrastructure conditions, thereby markedly boosting county-level well-being. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is confirmed.

Table 7.

Mechanism test results.

3.7. Heterogeneity Analysis of County Positioning

The impact of WNPC differs between county-level cities and counties; in other words, under different administrative classifications, its effect on county-level livelihood and well-being varies. Drawing on the approach of Sun et al. [], we divided the full sample into an agricultural group (county-level units, coded 0) and an industrial group (districts and county-level cities, coded 1). Table 8 presents the heterogeneity regression results of different county positioning. In agricultural counties, the coefficient of is 0.0116 and significant at the 1% level, indicating that WNPC has a positive and significant effect on livelihood and well-being in these areas. This result probably reflects the superior ecological endowments and rich natural resources of agricultural counties, which under an ecological protection mandate can develop green industries such as eco-agriculture, forest-based wellness services, and ecological tourism to diversify farmers’ income streams and thereby enhance well-being. By contrast, in industrial counties, the coefficient is 0.0020 and not statistically significant, suggesting a negligible impact on well-being. Industrial counties typically have mature industrial systems, and the development and emission constraints associated with WNPC may introduce structural bottlenecks that curb economic performance, resulting in limited welfare gains. Hence, Hypothesis 4 is confirmed.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity analysis results of county positioning.

4. Discussion

Grounded in econometrics and new economic geography, this study employs a DID model and the mediating effect model to examine the impact of national park construction on county-level livelihood and well-being. In recent years, DID models have been widely applied to evaluate the actual impacts of various environmental policies, such as the Ecological Compensation Policy [], the National Key Ecological Functional Areas Policy [], and Transfer Payment of Ecological Functional Areas Policy []. By comparing changes in the treatment and control groups before and after policy implementation, the DID model effectively addresses endogeneity arising from omitted variables and precisely identify causal effects. Regarding the weighting of evaluation indices, many scholars primarily employ subjective or objective weighting methods to assign indicator weights. Subjective approaches, chiefly including the analytic hierarchy process [], rely heavily on expert judgment and carry a high degree of subjectivity. Objective methods such as the entropy weighting method [], principal component analysis [], and others derive weights from the statistical relationships among variables, taking inter-indicator correlations into account but neglecting the influence of individual indicator variability on the assigned weights. This study employs the CRITIC weighting method to quantify the objective material foundations of county-level livelihood and well-being. The CRITIC weighting method, employed to determine indicator weights, is widely used in multi-criteria evaluations for economic decision-making. Its advantage lies in capturing both within-indicator variability and conflicts between indicators, providing scientific rigor and broad applicability that enhance the accuracy and interpretability of evaluation results []. However, this study does not account for individuals’ subjective experiences. Future research should retain objective quantitative assessments while integrating questionnaire or social survey data to introduce subjective perception indicators such as self-reported happiness and life satisfaction, to construct a comprehensive evaluation index system that more holistically and accurately captures the evolution of county-level livelihood and well-being. At the theoretical level, the existing literature has predominantly examined the institutional mechanisms of national park construction, with limited attention paid to its effects on regional livelihood and well-being. This study innovatively adopts a county-level perspective to construct an analytical framework for assessing the impact of national park construction on county-level livelihood and well-being, thereby expanding the research domain on the relationship between these two concepts. Prior studies have demonstrated that ecological compensation policies significantly enhance farmers’ livelihoods, thereby improving regional livelihood and well-being []. Our analysis further reveals that, as a distinct form of ecological conservation policy, national park construction similarly exerts a positive effect on county-level livelihood and well-being that is consistent with the outcomes of existing conservation policies, thus corroborating the accuracy and credibility of our results. At the practical level, with the in-depth transformation of the principal contradiction in Chinese society, the construction of national parks is an important component of ecological civilization. Assessment of its social impact effect is of great practical significance for promoting the high-quality construction of national parks, empowering regional coordinated development and improving people’s livelihoods and well-being.

Nevertheless, this study also has the following deficiencies. Firstly, although a theoretical framework linking national park construction to improvements in county-level livelihood and well-being has been established, further refinement is needed to elucidate the precise nature of this relationship and its underlying mechanisms. Secondly, this study does not account for individuals’ subjective experiences. Future research should retain objective quantitative assessments while integrating questionnaire or social survey data to introduce subjective perception indicators such as self-reported happiness and life satisfaction and to construct a comprehensive evaluation index system that more holistically and accurately captures the evolution of county-level livelihood and well-being. Finally, considering the limitations of the research scale and data availability, the universality of the research conclusions drawn in this study needs to be further verified. Although Wuyishan National Park, as a World Cultural and Natural Heritage Site, has a profound impact on enhancing regional social cohesion, promoting social harmony and improving well-being, due to the limitations of the spatial scale and time span of the research, the research conclusions of this study might not fully reflect the social impact of the construction of other types of national parks. Future research can compare different types of national parks such as geographical unit conservation and flagship-species conservation and deeply explore the heterogeneous changes in the levels of livelihood and well-being in counties under different conservation models.

Based on the foregoing analysis, this study proposes the following policy recommendations:

First, strengthen fiscal transfers and public service provision to areas in the central parts of Fujian, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang provinces where livelihood and well-being levels remain relatively weak. Prioritize increased investment in key basic livelihood sectors such as education, healthcare, and social security, to advance equalization of essential public services and narrow inter-regional development gaps. Meanwhile, to address the internal imbalances within the Jiangxi subregion, a performance evaluation mechanism integrating provincial coordination with county-level linkages should be implemented to enable differentiated resource allocation, prioritizing funds and services for counties with lower well-being levels and dynamically adjusting resource inputs according to evaluation outcomes. Through targeted measures, a spatial linkage mechanism of “stronger counties supporting weaker ones” can be established to enhance coordinated development across the entire region.

Second, when designing the institutional framework for Wuyishan National Park, improving livelihood and well-being should be established as a core objective to ensure that ecological dividends accrue to surrounding communities—for example, by creating ecological employment opportunities and implementing compensation schemes—thus integrating ecological protection with social development. Simultaneously, a rigorous, standardized monitoring and evaluation framework should be implemented to dynamically track how park construction affects residents’ well-being and to create a data-driven policy feedback loop. It is recommended to incorporate this evaluation system into the Wuyishan National Park Management Regulations, enabling continuous assessment and timely adjustment of implementation outcomes, and further enhancing the effectiveness of this system design.

Third, the ecological and cultural assets of Wuyishan National Park’s dual World Heritage status should be harnessed to cultivate emerging industries such as eco-guiding services, tea-culture experiences, and rural folk tourism, to attract young talent back to their hometowns for entrepreneurship and employment, thereby improving the demographic structure. Implementing the “Wuyishan Ecological Expert Introduction Policy” to provide benefits such as household registration, children’s education, and tax reductions for professionals in eco-guiding, tea-culture preservation, and environmental monitoring, can enhance the willingness of talent to flow in. Meanwhile, increased investment in infrastructure construction should focus on upgrading transportation roads and improving rural tourism facilities. In the process of infrastructure construction such as Provincial Highway S303, the concept of ecological protection should be integrated to promote the development of green infrastructure such as road landscaping and rain gardens. In addition, administrative barriers can be broken down by establishing cross-county infrastructure co-construction mechanisms, such as regional comprehensive transportation networks, to promote the transformation of infrastructure construction from a “scattered distribution” to a “networked distribution”.

Finally, tailored policy measures for the regions encompassing Wuyishan National Park should be formulated based on a thorough consideration of their locational attributes, resource endowments, and industrial foundation. For agricultural counties such as Guangze County, ecological compensation and financial support should be intensified by establishing dedicated ecological compensation funds to promote the development of eco-agriculture, Wuyishan tea, and other environmentally friendly industries, thereby raising farmers’ income levels and improving regional livelihood and well-being. For industrial counties such as Jianyang District, Shaowu City, and Wuyishan City, they should be guided to gradually phase out high-pollution and high-energy-consuming industries, and support should be given to the cultivation and development of green manufacturing, clean energy industries, and eco-tourism industries, to promote the green transformation of industries and facilitate sustainable regional development. Meanwhile, efforts should be made to enhance coordinated development among different counties, promote the interaction and collaboration between agricultural counties and industrial counties, establish a cross-regional ecological collaboration mechanism, achieve resource sharing, and ensure common benefits for the entire region.

5. Conclusions

This study constructs a comprehensive evaluation index system of county-level livelihood and well-being from three dimensions—basic material well-being, safety and health well-being, and socio-cultural well-being—using panel data for 138 counties (cities and districts) in Fujian, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang provinces over 2011–2023. The CRITIC weighting method was applied to assign weights and compute the composite well-being score, while kernel density estimation and the Theil index were employed to characterize the spatio-temporal patterns of county-level livelihood and well-being. On this basis, the DID model was used to analyze the impact of WNPC on county-level livelihood and well-being, with further exploration of the underlying mechanisms. Our results show that from 2011 to 2023, county-level livelihood and well-being scores ranged from 0.1329 to 0.4565, indicating substantial room for improvement. Over time, disparities among counties have gradually narrowed, exhibiting a “higher in the east and west, lower in the center” spatial pattern. Overall differences are pronounced and mainly driven by within-region variation, with internal disparity in the Jiangxi subregion markedly exceeding that of Fujian and Zhejiang. Benchmark regressions confirm that WNPC significantly enhances county-level livelihood and well-being, a finding robust to multiple robustness tests. Mechanism analysis indicates that WNPC promotes population mobility and improves infrastructure construction, thereby substantially boosting county-level livelihood and well-being. Heterogeneity analysis suggests that the livelihood and well-being effects of WNPC exhibit pronounced heterogeneity across county administrative types; agricultural counties experience significantly greater improvements than industrial counties.

Author Contributions

S.L. contributed to conceptualization, data collection, methodology, writing—original draft, formal analysis, and visualization. J.Y. contributed to conceptualization, visualization, editing, and supervision. R.W. contributed to data collection, software, and methodology. M.Q. contributed to conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the National Social Science Fund of China (grant number 20BGL171).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WNPC | Wuyishan National Park Contruction |

References

- Tan, Y.F.; Zhu, C.X. The well-being effect of digital inclusive finance: “Dividend” and “gap”. Northwest Popul. J. 2024, 45, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, X.C.; Huan, Q.Z. The discourses of green modernization and eco-civilizational progress in contemporary China: Convergence, tension and mutual learning. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Ostergaard, S.D.; Sondergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davino, C.; Gherghi, M.; Sorana, S.; Vistocco, D. Measuring social vulnerability in an urban space through multivariate methods and models. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 157, 1179–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, R.; Zia, U. Multidimensional well-being: An index of quality of life in a developing economy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, K.A.; Tafere, K.; Berhane, G.; Chamberlin, J.; Abay, M.H. Near-real-time welfare and livelihood impacts of an active war: Evidence from Ethiopia. Food Policy 2023, 119, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, A.P.B.; Gutiérrez-Montes, I.; Hernández-Núñez, H.E.; Gutiérrez-Suárez, D.R.; Gutiérrez García, G.A.; Suárez, J.C.; Casanoves, F.; Flora, C.; Sibelet, N. Diverse farmer livelihoods increase resilience to climate variability in southern Colombia. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Wang, P.H.; Wu, L. Well-being Through Transformation: An Integrative Framework of Transformative Tourism Experiences and Hedonic Versus Eudaimonic Well-being. J. Travel Res. 2024, 63, 974–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, B.P.H.; Ng, J.C.K.; Berzaghi, E.; Cunningham-Amos, L.A.; Kogan, A. Rewards of Kindness? A Meta-Analysis of the Link Between Prosociality and Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 1084–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arouri, M.; Nguyen, C.; Ben Youssef, A. Natural Disasters, Household Welfare, and Resilience: Evidence from Rural Vietnam. World Dev. 2015, 70, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, Y.L. The enhancement effect of regional integration policy implementation on people’s well-being—A study based on the development strategy of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Acad. Mon. 2023, 55, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhao, L.; Guo, J.M.; Du, M.H.; Hao, C.X.; Hu, R. Analysis of coordinated development of “society-ecology-policy” and spatio-temporal variation of people’s livelihoods and well-being in the Yellow River basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 109675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Clay, P. Measuring subjective and objective well-being: Analyses from five marine commercial fisheries. Hum. Organ. 2010, 69, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Lu, C.; Sun, R. The Impact of Livelihood Capital on Subjective Well-Being of New Professional Farmers: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.L.; Phillips, A. How Does the Life Satisfaction of the Poor, Least Educated, and Least Satisfied Change as Average Life Satisfaction Increases? J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 2389–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre-Andres, S.; Drews, S.; Van Den Bergh, J. Perceived fairness and public acceptability of carbon pricing: A review of the literature. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 1186–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Danish; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. Renewable energy consumption, economic growth and human development index in Pakistan: Evidence from a simultaneous equation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, J.E.; Sachs, J.D. The SDGs and human well-being: A global analysis of synergies, trade-offs, and regional differences. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, Q.S.; Yu, D.Y.; Li, X.Y. Coupling characteristics of China’s food-energy-water nexus and its implications for regional livelihood well-being. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 395, 136385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.T.; Gong, Y.L.; Jiang, C.J. Spatio-temporal differentiation and policy optimization of ecological well-being in the Yellow River Delta high-efficiency eco-economic zone. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, P.L.; Wang, X.; Mo, J.X.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.Y. Impact of the Grain for Green Project on the Well-Being of Farmer Households: A Case Study of the Mountainous Areas of Northern Hebei Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Dong, X.B.; Liu, H.M.; Wei, H.J.; Fan, W.G.; Lu, N.C.; Xu, Z.H.; Ren, J.H.; Xing, K.X. Linking land use change, ecosystem services and human well-being: A case study of the Manas River Basin of Xinjiang, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyn, C.; Musa, K.; Castanho, R.A. Can Digitalization Bridge the Gap? Exploring Human Development and Inequality in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.D.; Tang, X. Exploring the New Era: An Empirical Analysis of China’s Regional HDI Development. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.Z. National parks in China: Parks for people or for the nation? Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.J.; Fan, J.; Xing, S.H.; Cui, G.F. Overview and classification outlook of natural protected areas in mainland China. Biodivers. Sci. 2018, 26, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.D.; Long, Y.; Shi, L.F. Stakeholders’ evolutionary relationship analysis of China’s national park ecotourism development. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.L.; Wang, X.Q.; Mao, Y.; Wang, K.; Yu, Y. An analysis of the awareness and attitudes of community residents and visitors to national parks: Taking Shennongjia National Park as an example. Environ. Prot. 2019, 47, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhong, X.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, Y.H.; Ran, J.H.; Zhang, J.D.; Yang, N.; Yang, B.; Zhou, C.Q. Optimizing the Giant Panda National Park’s zoning designations as an example for extending conservation from flagship species to regional biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 281, 10996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhong, L.S.; Zeng, Y.X. Research on Identification of Potential Regions of National Parks in China. J. Nat. Resour. 2018, 33, 1766–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, O.; Sanderson, E.W.; Magrach, A.; Allan, J.R.; Beher, J.; Jones, K.R.; Possingham, H.P.; Laurance, W.F.; Wood, P.; Fekete, B.M.; et al. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Y.Q.; Wu, C.H.; He, Y.J. Public Concern and Awareness of National Parks in China: Evidence from Social Media Big Data and Questionnaire Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.R.; Xu, M.M.; Pang, G.F.; Ji, H.; Li, M. Has national park construction enhanced the well-being of neighboring farmers? Taking the Giant Panda National Park as an example. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 10560–10572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]