Abstract

As urbanization intensifies, high-density communities have become a dominant urban form, making Child-Friendly Community (CFC) development crucial for sustainable urban growth. However, transforming these communities poses challenges, particularly regarding residents’ risk perceptions—an area largely overlooked in existing research. To address this gap, this study introduces “Risk Tolerance (RT)” as a key variable and constructs a multidimensional model of Child-Friendly Community Transformation Risk Tolerance (CFCTRT) to examine its structure and influencing factors. Based on survey data from residents in high-density communities in China’s first- and second-tier cities, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is used for empirical analysis. The results show that residents exhibit lower tolerance toward changes in safety, economy, and daily life, but higher tolerance in resource and aesthetic dimensions. Expectations for CFCs and satisfaction with current communities both positively influence CFCTRT, with satisfaction also mediating the relationship between expectations and tolerance. These findings provide a novel perspective on residents’ psychological responses to CFC transformations and offer empirical support for more inclusive and adaptive urban planning strategies.

1. Introduction

The accelerated global urbanization process has gradually made high-density communities one of the primary forms of urban living [1]. High-density communities have increased land utilization to a certain extent and improved living conditions; however, they have also led to insufficient activity space for children [2], intensified community conflicts, weak community awareness [3], and a series of issues such as low resident participation [4]. It has severely affected the growth environment and quality of life for children. However, the community environment is crucial for the growth and development of urban children, as it affects their ability to travel independently [5] and profoundly impacts children’s motor skills, cognitive development, interpersonal attitudes, and emotional development [6]. The United Nations has also repeatedly emphasized the importance of children’s rights [7]. The construction of Child-Friendly Communities (CFC) has been recognized as a critical component of the global sustainable development goals [8]. Therefore, how to transform existing high-density communities to meet the requirements of Child-Friendly Communities has become an essential topic of recent research.

In China, the development of child-friendly communities occurs within a unique and complex social and policy framework. The country’s birth rate has been steadily declining over the years. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the birth rate fell from 1.809% in 1993 to 0.677% in 2022, representing a decrease of nearly two-thirds [9]. The seventh national census in 2020 confirmed that China has entered a low fertility rate stage [10]. In response to these demographic challenges, the government has gradually relaxed birth restrictions, moving from the “one-child policy with exceptions” in 2013 to the “comprehensive three-child policy” in 2021. However, these measures have not succeeded in reversing the trend. Within this context, the development of child-friendly communities assumes significant strategic importance.

The core objective of community child-friendly renovation is to create a safe, healthy, and inclusive growing environment for children [11]. Although this renovation goal has been widely recognized [12], it faces serious conflicts during implementation in high-density community environments due to the diverse needs of residents and the scarcity of resources [13]. Traditional Chinese culture embraces the notion of “sacrificing for one’s children,” where parents frequently make concessions and adjustments in the interest of their offspring [14]. However, in high-density communities with severely limited resources, this cultural inclusivity becomes constrained by practical realities. When residents perceive that their rights and interests are being undermined, their tolerance diminishes, creating a pronounced contradiction that is particularly evident in high-density settings.

Therefore, child-friendly renovation is a spatial planning issue and involves deeper moral and social equity concerns. In high-density urban renewal projects, stakeholders have significant disagreements and conflicting interests across economic, environmental, and social dimensions [15,16]. Among them, residents, as direct stakeholders and end-users of community renewal projects, play a decisive role in the success or failure of the renovation projects through their attitudes and behaviors [17].

Risk tolerance (RT) refers to individuals’ or groups’ acceptance and adaptive capacity when facing unknown risks or uncertainties [18]. This concept originates from the field of economics [19,20] and is innovatively applied in this study to community planning research. During the transformation process of child-friendly communities, residents may develop negative attitudes toward the risks associated with the implementation of the changes due to inconveniences during the renovation, concerns about the outcomes, priority disputes [21], or resistance to the content of the changes, which directly affects the final results of the transformation. Therefore, this study introduces RT into the research on CFC renovation, defining it as, in the context of child-friendly environmental transformation, the risk control ability and risk attitude tendencies exhibited by residents in response to the potential negative impacts brought about by the transformation process and outcomes, based on their perception levels. As a key indicator for assessing residents’ risk acceptance levels, RT can help researchers better understand residents’ attitudes and behaviors while providing practical guidance for policymakers. Previous research has shown that factors such as satisfaction [22], loyalty [23], personal willingness to use, perceived performance [24], and expectations [25] affect RT. After referencing relevant model structures and considering the characteristics of child-friendly communities, this study constructs a theoretical model encompassing three core variables: “residents’ satisfaction with their current community”, “residents’ expectations for the child-friendly community transformation”, and “Child-Friendly Community Transformation Risk Tolerance (CFCTRT)” aiming to systematically explore the risk tolerance mechanisms of residents and provide a scientific basis for promoting the smooth implementation and sustainable development of child-friendly community construction.

This study aims to investigate the expected risk tolerance mechanisms for transforming child-friendly environments in high-density communities. To achieve this goal, this research (1) proposes the concept of CFCTRT and develops a conceptual framework and measurement methods to determine the performance of RT across different dimensions; (2) summarizes the CFCTRT mechanism to explore the manifestations of residents’ tolerance and influencing factors; and (3) based on the research findings, suggests targeted measures to enhance residents’ tolerance for child-friendly construction to optimize community planning and policy design.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Space and Resident Needs in High-Density Communities in Urbanization Contexts

In recent years, the concept of family-oriented urbanization has attracted significant attention in the realm of international urban planning [26]. Within this context, the role of the family is both affected by and contributes to the outcomes of urban planning efforts [27]. This concept emphasizes the integration of the family unit as a crucial dimension in urban design, to enhance overall family well-being by improving housing conditions, community facilities, and public services [28]. Designing child-friendly environments should prioritize balancing intergenerational needs throughout the urbanization process [29], thus fostering parent–child interaction and supporting children’s independent development through “family-friendly space design.” The unique family structures in China, such as three-generation households, add practical significance to this concept. In high-density communities, families must often coordinate the activity needs of multiple generations within limited space. Therefore, it is essential to thoroughly understand the social and physical environmental characteristics of high-density communities.

The characteristics of the social and physical environments in high-density communities significantly influence residents’ quality of life and the developmental contexts for children. From a social perspective, while high-density communities can foster community connections and social interactions, thereby enhancing community cohesion [30], the living conditions within high-rise buildings may also provide greater privacy at the expense of intimate social exchanges and mutual care among residents [31]. Public spaces in high-rise apartments often fail to meet the daily activity needs of the residents [32]. Moreover, high population density can generate stress, particularly when individuals perceive the available space as insufficient; such pressure may impede social interactions and activities [33]. Additionally, high-density communities can exacerbate social issues, including heightened insecurity [34], further diminishing residents’ sense of community belonging, and overall residential satisfaction.

Regarding the physical environment, high-density communities typically contend with challenges such as inadequate public spaces, overcrowding, limited transportation options, compromised privacy [35], and various safety hazards [36]. The existing literature suggests that families with young children often view residing in high-rise buildings as inconvenient and undesirable [31,37,38], primarily due to the scarcity of indoor and outdoor play spaces [39]. Residents express significant concerns regarding the safety of children in such environments [40].

High-density communities exhibit distinct social and physical environmental characteristics that require the careful consideration of various interests when implementing renovation measures. As a result, more studies are investigating how design factors can influence the relationship between community density and social dynamics [41], community resource allocation [42], and community equity [43]. These studies also examine the effects of environmental design on community social relationships [44]. Environment design is no longer perceived solely as a spatial issue [45]; instead, it is recognized as a multifaceted social system problem encompassing the interconnections among people, resources, and space.

2.2. Research on Transforming Environments to Become Child-Friendly

Child-friendly environments are rooted in a series of advocacy documents issued by the United Nations [46]. Since its inception, this concept has gained significant recognition and has become a crucial focus of discourse concerning children’s welfare in urban development. Current research on child-friendly environments primarily emphasizes the creation of conditions that effectively address children’s needs and rights [47]. Studies in this field often investigate the impact of community environments on children, exploring how these surroundings promote outdoor physical activities [48] and examining the effects of built environments, population density, transportation systems, and nature on child development [49]. In addition to physical influences, research has highlighted the importance of social networks and community cohesion as essential factors contributing to children’s holistic development [50]. Furthermore, exploring strategies to enhance a community’s child-friendliness is among the most critical aspects of this research domain. For high-density communities, scholars have proposed various macro-level approaches concentrating on planning systems, understanding children’s needs, establishing collaborative platforms, and implementing health monitoring mechanisms [51]. Conversely, from a micro-level perspective, strategies such as improving traffic route design, planning natural environments, and renovating communal outdoor spaces have been suggested to facilitate positive changes in urban spatial attributes [52]. From the standpoint of participatory interaction, methods for involving children in community design and construction have been introduced. Additionally, quantitative assessment models for evaluating child-friendliness and developing updating strategies have emerged from a psychological angle [53]. Collectively, it is evident that contemporary research on transforming communities into child-friendly spaces predominantly centers on understanding the influence of environmental factors on children and identifying specific renovation strategies [54].

It is important to emphasize that, despite the widespread acknowledgment of the CFC concept and extensive research on transformative theories and strategies, implementing child-friendly environmental changes within communities currently encounters significant obstacles. Studies have identified challenges in developing child-friendly cities and communities, including intricate governance structures, intergenerational tensions [55], and conflicts among diverse stakeholders [56]. The CFC, grounded in caring for vulnerable groups, necessitates that the general population forgo certain benefits. This requirement exacerbates resource allocation conflicts, particularly in densely populated areas with limited resources. Discrepancies in resource distribution and transformation methods frequently lead to resident dissatisfaction, which diminishes support for these initiatives and may intensify social conflicts, complicating social equity issues during the transformation process [57]. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) asserts that child-friendly cities should be suitable for all [58]; however, existing research predominantly focuses on children as the primary subjects, often overlooking other stakeholders’ perspectives in the practical implementation. This narrow focus may adversely affect such initiatives’ acceptability, feasibility, and long-term sustainability.

Similar urban renewal studies have revealed that various stakeholders often hold differing opinions regarding formulating urban renewal strategies and implementing development plans [59]. Urban renewal significantly impacts diverse residential groups and their social networks [60], fluctuates housing prices in surrounding communities [61], and can enhance infrastructure, among other effects. Studies employing a multi-stakeholder perspective indicate that if conflicts arising during urban renewal are not effectively managed, they may result in detrimental outcomes, such as challenges to public participation [62], diminished social cohesion [63], social exclusion [64], gentrification [65,66], and social injustice [67,68]. These represent the negative social consequences associated with the urban renewal process. Consequently, in the context of complex urban demands and constrained resources, the study of urban renewal must be integrated with the “human-society-space” framework to address spatial renewal issues effectively.

In conclusion, although the significance of CFC modification and the accompanying theoretical research and specific modification strategies are well-articulated, a notable deficiency exists in examining CFC environmental modifications in complex social systems. This oversight contributes to the persistence of complex challenges in implementing modification practices, despite their potential to yield positive social outcomes.

2.3. Research on Tolerance for Expected Risks in Child-Friendly Environment Transformations

RT refers to the degree of risk an individual accepts to achieve specific goals [69]. This concept originated primarily in finance and investment, where it plays a crucial role in shaping the decision-making processes of investment entities [19]. As interdisciplinary research has evolved, exploring RT has expanded into various domains, including medicine [70], psychology [71], tourism [72], consumer behavior [73,74], public health [75], and food safety [76]. In these areas, RT is utilized to evaluate factors that influence decision-making and the practicality of certain practices. Notable patterns have emerged across different contexts: individuals with higher RT tend to make decisions more readily and report greater satisfaction with their choices [77,78]. Investigating the mechanisms contributing to RT among specific groups or within particular environments is essential for a deeper understanding of behavioral decision-making and accepting varying circumstances.

In the CFC environmental transformation, which has recently attracted considerable attention from policymakers and practitioners, a notable deficiency exists in systematic research that evaluates residents’ acceptance of transformative behaviors through resident RT. This gap hinders a comprehensive understanding of the diverse psychological responses exhibited by community residents when confronted with child-friendly transformations, particularly regarding the complex attitudes that may encompass skepticism, resistance, or compromise. Consequently, this limitation further constrains the effective implementation and scientific application of child-friendly policies.

Introducing RT into the transformation of child-friendly environments in high-density community contexts not only elucidates the acceptance boundaries of residents in the face of potential risks but also establishes a quantifiable and interpretable framework for assessing behavioral and psychological factors integral to constructing child-friendly communities. This approach provides novel perspectives and tools for the transformation practices of child-friendly communities, thereby offering substantial theoretical value and practical significance. It enhances the social acceptability of transformative actions, mitigates resident resistance, and optimizes decision-making processes.

3. Research Method

The research methodology employed in this study is delineated in the following steps: First, informed by preliminary theoretical analysis and a comprehensive review of the relevant literature, we designed and developed a scale for measuring CFCTRT. Subsequently, a research model was constructed, incorporating three core variables: expectations, satisfaction, and tolerance. Empirical data were collected via a questionnaire survey. Second, we performed descriptive statistical analysis on the fundamental characteristics of the collected data and each variable. This analysis systematically described residents’ expectations concerning developing child-friendly communities, their satisfaction with living conditions, and their tolerance for potential transformation risks. Third, we employed structural equation modeling (SEM) to construct a pathway model in which expectations serve as the independent variable, satisfaction acts as the mediating variable, and tolerance functions as the dependent variable. This model elucidates the causal relationships and mechanisms connecting the three variables. Finally, based on the findings from the model analysis, we propose a set of recommendations for child-friendly environmental transformations to enhance residents’ tolerance within high-density community contexts. This framework provides both theoretical foundations and empirical support for future policy formulation and community practice.

3.1. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1.1. Measurement Tool for CFCTRT

To scientifically evaluate residents’ risk tolerance while transforming communities into child-friendly spaces, this article aims to develop a systematic tool for measuring residents’ acceptance of potential risks associated with renovations. This endeavor is predicated on the premise that “any community renovation may elicit varying degrees of negative emotional responses from residents, and such negative attitudes can inhibit their participation in renewal activities [79].” While the planning and renovation of child-friendly communities are often intended to enhance the quality of life for children and families [80], they can inadvertently lead to issues such as disruption of daily life, economic burden, conflicts over resource allocation, safety hazards, and environmental changes, particularly in high-density settings. These challenges can engender dissatisfaction and shape residents’ perceptions of risk. To identify these potential risks thoroughly, this paper synthesizes five key dimensions that significantly influence residents’ subjective experiences, derived from a systematic review of various child-friendly community renovation initiatives: daily life, economy, resources, safety, and aesthetics. The inclusion of these dimensions not only highlights the principal forms of disruption to residents’ lives resulting from community renovations and aligns with the foundational principles of the child-friendly concept, which emphasizes “all-age inclusivity [80], diverse participation, shared spaces [29], and accessible safety [81].”

Daily Life Risk Tolerance (DLRT) assessment and transformation significantly affect residents’ daily behavior patterns and overall quality of life. Efforts to create child-friendly communities often entail modifications to public spaces, traffic patterns, and activity hubs [82], which can disrupt the established rhythms of residents’ lives. In high-density communities, repurposing spaces and integrating various functions are common; consequently, any adjustments may be exacerbated, potentially leading to resident dissatisfaction. For instance, noise from children’s activities [83], traffic disruptions during construction, and barriers to access can all undermine residents’ satisfaction and adaptability to their living environments. Furthermore, while children’s participation in public affairs, such as community governance [84] and event planning [85,86], reveals the community’s commitment to becoming more child-friendly, it may raise concerns among some residents regarding the practicality of such inclusiveness. Factors influencing these concerns include the methods and extent of children’s involvement and the perceived impact of their decisions, which may be viewed as disrupting the existing order of daily life.

The introduction of Financial Risk Tolerance (FRT) at the economic level is based on practical considerations. Any community renovation project involves financial investments and subsequent maintenance [87]; child-friendly facilities are frequently used and require substantial maintenance, often making residents more sensitive to the economic costs associated with their upkeep. Community renovations may trigger chain reactions, such as increased property fees, rental fluctuations, or rising living costs. These can place a noticeable strain, particularly on older communities, rental tenants, or low-income groups. This sense of economic burden may be more pronounced in densely populated, resource-constrained high-density communities.

Child-friendly communities prioritize spatial design conducive to children’s needs and encourage the equitable sharing of public resources [88]. However, in densely populated areas with limited resources [81], any reallocation may lead to competitive perceptions among different demographic groups. When community resources such as green spaces and activity areas are predominantly allocated for children’s use, adults without children or other residents might feel deprived and question whether an undue advantage is given to a particular group. The Resource Risk Tolerance (RRT) dimension evaluates residents’ perceptions of the fairness of resource allocation. Key indicators include the willingness to repurpose unused spaces, acceptance of renovations to existing facilities, and views on prioritizing infrastructure for children’s activities.

Safety constitutes the most fundamental need for residents, particularly in high-density living environments where limited space and frequent movement can amplify potential safety risks. Safety issues emerge in the construction and usage phases during the transformation of child-friendly communities. In the construction phase, inadequate management of barriers, traffic organization, and placement of construction facilities can heighten residents’ concerns regarding the risk of accidents, thereby increasing their psychological burden. In the subsequent usage phase, the safety of facilities, maintenance frequency, and adherence to management standards become primary long-term concerns for residents. Consequently, Safe Risk Tolerance (SRT) plays a pivotal role in transforming high-density communities into child-friendly environments. It greatly influences residents’ acceptance of the changes and determines the overall success of the renovation efforts.

Though frequently overlooked, Aesthetic Risk Tolerance (ART) is a significant component of residents’ risk perception. Child-friendly renovations often introduce visual elements, such as cartoons and graffiti [89], and involve modifying existing architectural landscapes’ color and style. While these alterations may enhance children’s experiences, they may not be universally appreciated by all residents. The aesthetic dimension evaluates residents’ acceptance of modifications to the community’s visual landscape, particularly concerning the preservation of cultural characteristics, the consistency of architectural styles, and the diversity of artistic expression.

3.1.2. Model Mechanism Construction

In the research on RT, numerous studies have shown that it is influenced by a combination of factors, particularly individual characteristics, current satisfaction, and future expectations, which are the core driving variables. Factors such as gender, age, education level, income level, personality traits, and homeownership have been proven to have significant correlations with RT [90,91]. Chebotareva’s research indicates that individuals with higher life satisfaction, across different cultural backgrounds, typically have better control over negative emotions, exhibiting greater tolerance in intercultural exchanges [22]. Korol’s empirical analysis also reveals that life satisfaction, through political satisfaction and social trust, influences young Swedes’ attitudes of tolerance towards immigrants [92]. Furthermore, in electronic services, Valvi and colleagues, using structural equation modeling (SEM) and variance analysis, found that enhancing user satisfaction and loyalty is a prerequisite for shaping a positive attitude and tolerance towards websites [93]. Many studies on the willingness to relocate have pointed out that community satisfaction is crucial in determining an individual’s intention to move [94]. At the same time, the expectations of living standards influence residential satisfaction [95].

These studies collectively underscore a significant insight: an individual’s willingness and tolerance are not formed in isolation but are influenced by the interaction between their satisfaction with the current environment and their expectations for future changes [96,97] and established psychological theories, such as Psychological Construct Theory [25] and Expectation–Confirmation Theory (ECT) [24,98], further support this perspective. The ECT, in particular, highlights the crucial role of the disparity between expectations and perceived performance in shaping both satisfaction and behavioral intentions. It is frequently employed to predict user willingness, migration intentions, and acceptance of services.

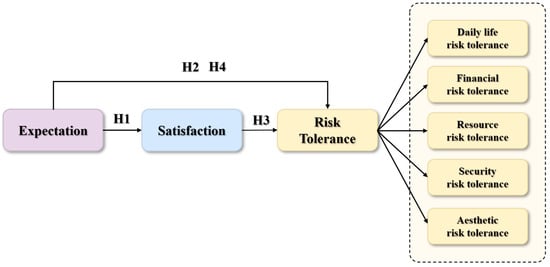

In this study, we integrate the proposed theoretical framework into the research on risk tolerance concerning the transformation of child-friendly communities in high-density urban areas. We have developed a model incorporating “Expectation, Satisfaction, and Risk Tolerance” to investigate how residents accept risks associated with these transformations. Consequently, we propose the following hypotheses, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed models and hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1.

Expectations have a significant impact on Satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2.

Expectations have a significant impact on RT.

Hypothesis 3.

Satisfaction has a significant impact on RT.

Hypothesis 4.

Expectations have an indirect effect on RT through the mediating role of Satisfaction.

In terms of methodology, this study employs Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) as the primary analytical tool. Its capability to manage complex path relationships among multiple potential variables requires construction through measurement models. SEM is a robust quantitative method, particularly effective in exploring intricate relationships between interacting variables within the social sciences [99]. Its ability to estimate and test abstract concepts makes it well-suited for the causal validation needs of this study [100], specifically about the mechanisms underlying residents’ tolerance.

3.2. Variable Definition and Questionnaire Design

Residents’ expectations, satisfaction, and RT are latent variables within the previously discussed research model, rendering them challenging to measure directly. Consequently, it is essential to choose relevant observed variables for indirect measurement, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of observation variables.

The residents’ expectations seek to gauge their anticipations and aspirations regarding developing CFC, specifically concerning the potential enhancements in community characteristics that contribute to child-friendliness. This variable is assessed using a single-item question: “Do you anticipate creating a more child-friendly community environment?” Responses are recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “not at all anticipated” and 5 denotes “very much anticipated.” This approach captures residents’ expectations regarding CFC development and provides essential data for further analysis of the factors influencing resident satisfaction and risk tolerance.

The objective of assessing resident satisfaction is to evaluate their perceptions and evaluations of the child-friendly attributes of their residential community. Satisfaction is quantified using three observed variables: service facilities (Sat1), activity spaces (Sat2), and the travel environment (Sat3). This scale is derived from the “Guidelines for Constructing Child-Friendly Urban Spaces (Trial) [101],” which details standards for creating child-friendly community areas. Residents provide ratings for each item on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“Very dissatisfied”) to 5 (“Very satisfied”). The composite score derived from these ratings is employed to gauge residents’ overall satisfaction regarding the child-friendliness of their community, with higher scores depicting higher levels of satisfaction.

RT is measured across five dimensions: DLRT, FRT, RRT, SRT, and ART. Specifically, the observation variables for DLRT include children’s activity noise (DL1), construction noise (DL2), travel convenience (DL3), children’s participation in decision-making (DL4), and parent–child activities (DL5). For FRT, the observation variables are the sharing of construction and maintenance costs (E1), fluctuations in housing prices and rent (F2), and changes in the cost of living (F3). RRT is observed through the utilization of idle land (R1), child-friendly adaptation of existing spaces (R2), and prioritized allocation of resources (R3). SRT has observation variables such as potential risks during construction (S1), management and maintenance of the community post-renovation (S2), and the safety of spaces, facilities, and traffic routes (S3). ART includes variables like artistic expression (A1), changes in cultural style (A2), and the uniformity of architectural styles (A3). Each item is measured using a five-point Likert scale (1 = “Very Unacceptable,” 5 = “Very Acceptable”). A higher total tolerance score indicates a higher level of acceptance by the residents.

3.3. Data Source

This study examines the residents of China’s first-tier cities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, and selects new first-tier and second-tier cities. The research focuses on communities in these cities with relatively high population densities. The primary aim is to investigate the formation mechanisms and influencing factors of residents’ risk tolerance concerning the construction and transformation of Child-Friendly Communities (CFC) in high-density urban environments. Within the current Chinese urban governance framework, a “community” is a social living unit comprising individuals residing within a specific geographic area. These communities fall under the jurisdiction of residents’ committees whose scales have been adjusted following recent restructuring [102]. Hence, in this study, “community” refers to grassroots management units in urban and rural areas, established according to government department planning.

Given the absence of a universally recognized definition for high-density communities in the sample selection process, this study draws on established urban planning and residential research standards. The criteria utilized include communities predominantly composed of mid- to high-rise buildings with a floor area ratio greater than 2.0. The research team conducted site visits and surveys, and corroborated community physical characteristics with publicly accessible data, to ensure that the samples are representative and pertinent to this study.

Data collection employed a combination of online and offline methods, utilizing random sampling techniques to ensure the diversity and socioeconomic representativeness of the sample. Online questionnaires were distributed via social media platforms and community WeChat groups, while offline questionnaires were randomly disseminated at local community service centers and public spaces. A total of 682 questionnaires were initially distributed. However, responses from non-first and second-tier cities and those with abnormal completion times or highly consistent answers were identified as invalid and excluded. Consequently, 554 valid questionnaires were retained, with 70% of responses collected online and 30% offline. The effective response rate was 81%.

3.3.1. Characteristics of the Sample Population

The socio-demographic data comprise six variables: gender, age, educational level, marital status, employment status, and current housing type. The distribution characteristics of this survey data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of sample characteristics.

3.3.2. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Variables

The descriptive statistical analysis results in Table 3 reveal that 93.7% of respondents rated their expectations as “average” or higher, demonstrating a substantial anticipation among community residents for developing a child-friendly environment. The mean satisfaction scores for various aspects of the current community environment are approximately 3.55, indicating that most residents are moderately content with the existing community service facilities, living environment, and activity spaces. The residents’ tolerance for various variables ranges between 3 and 4. Among the average scores for each indicator, ART had the highest score (mean = 3.89), followed by RRT (mean = 3.83) and DLRT (mean = 3.61), while FRT and SRT had relatively lower scores, at 3.41 and 3.31, respectively.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of observed variables.

3.3.3. The Influence of Residents’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics on Tolerance

The normality test for each measurement item was conducted using kurtosis and skewness. According to the standard proposed by Kline [103], if the absolute value of the skewness coefficient is within 3 and the absolute value of the kurtosis coefficient is within 8, the data can be considered to meet the requirements of an approximately normal distribution. Based on the analysis results (Table 3), it can be seen that the data meet the requirements of an approximately normal distribution.

After passing the normality test, a parametric test method was used to analyze the differences in tolerance for the transformation of child-friendly environments among different groups. Specifically, independent samples t-tests were employed for binary variables (such as gender and childbearing status), while one-way ANOVA was used for categorical variables with multiple categories (such as age, education level, marital status, and type of residence). Before analysis, a test for homogeneity of variances was conducted, and in cases where the homogeneity of variances assumption was not met, the Welch correction was applied [104]. All analytical results are summarized in Table 4, systematically comparing the differences in tolerance for the transformation of child-friendly environments among various social groups. Due to space limitations, this study only presents the variables that showed significant differences.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results of tolerance levels among residents with different social attributes.

Research suggests substantial gender-based differences in residents’ tolerance levels for DLRT and SRT, with males displaying higher tolerance compared to females. Age groups also show significant variance in tolerance for DLRT and FRT; notably, tolerance generally increases with age except for residents over 60 years. Educational background contributes to significant differences in tolerance for DLRT and SRT, with individuals holding an associate degree demonstrating the highest tolerance, followed by those with bachelor’s and postgraduate degrees, among whom tolerance increases incrementally. Marital and parental statuses also play crucial roles in shaping tolerance levels for DLRT, FRT, RRT, and ART, with married residents exhibiting the highest tolerance levels compared to unmarried or divorced individuals. Moreover, the presence of children significantly influences tolerance for RRT and ART; married and divorced residents with children display higher tolerance than those without. Lastly, housing arrangements markedly impact tolerance for DLRT, FRT, RRT, SRT, and ART. However, in the case of SRT, homeowners tend to show the highest tolerance across most categories.

4. Results

This section employs the methodology outlined by Anderson and Gerbing [105] to analyze both the measurement model and the structural model of structural equation modeling in a two-stage process. The first-order measurement model is initially tested to ensure its reliability and validity. Following this, the second-order measurement model is assessed to determine the fit of its five dimensions. Finally, the structural model is evaluated to investigate the strength of the relationships among “expectation-satisfaction-tolerance,” thus validating its mechanistic model.

4.1. Measurement Model

4.1.1. Reliability and Validity Testing

The first-order measurement model primarily evaluates the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. SPSS 27.0 software was used to conduct reliability and validity tests and correlation coefficient analysis of the constructs (Table 5 and Table 6). The reliability (Cronbach’s α) coefficients for each dimension ranged between 0.808 and 0.879, and the composite reliability (CR) ranged between 0.808 and 0.855, indicating a relatively high reliability of the questionnaire. Each dimension’s Average Variances Extracted (AVE) was greater than 0.50, demonstrating good convergent validity of the scale. Additionally, the square root of the average variance extracted for each latent variable exceeded the correlation coefficients with other latent variables [106], indicating good discriminant validity of the scale.

Table 5.

Reliability and convergent validity of the scale.

Table 6.

Tolerance latent variable correlation coefficients and AVE.

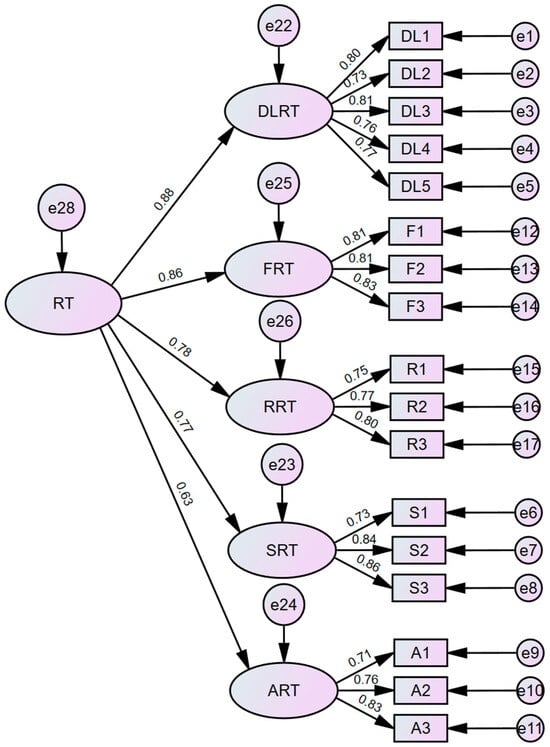

4.1.2. CFCTRT Confirmatory Second-Order Factor Analysis

This article examines CFCTRT through five dimensions: DLRT, FRT, RRT, SRT, and ART, thereby necessitating a confirmatory second-order factor analysis. As indicated in Table 6, the correlation coefficients among these five dimensions range from 0.45 to 0.77, signifying moderate to high correlation. Each dimension includes at least three observed variables, fulfilling the prerequisites for executing a second-order model confirmatory factor analysis [107]. Thereafter, the path analysis of the tolerance second-order model, presented in Table 7, reveals that the standardized loadings of each first-order factor on the second-order factor range from 0.628 to 0.883, all statistically significant at the p < 0.001 level, indicating a robust relationship between the second-order factor and the first-order factors. Table 8 showcases the goodness-of-fit indices for the second-order model specific to the CFCTRT second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Based on the values suggested for the fit [108], it can be found that the model fits well. Utilizing the standardized factor loadings, the CR of the second-order factor is determined to be 0.89, with an AVE of 0.62, reflecting sound reliability and validity. Consequently, the structure of the tolerance second-order model is affirmed as reasonable. RT, representing a second-order factor, encompasses DLRT, SRT, ART, FRT, and RRT as first-order factors, thus confirming Hypothesis 1. The outcomes of the second-order model are illustrated in Figure 2. The path coefficients between RT and its five dimensions reveal the influence order as follows: DLRT (0.88), FRT (0.86), RRT (0.78), SRT (0.77), and ART (0.63), indicating that daily life and financial factors primarily influence residents’ tolerance.

Table 7.

Path coefficients of the second-order model for tolerance.

Table 8.

Fit test for the second-order tolerance model.

Figure 2.

Second-order model of residents’ tolerance.

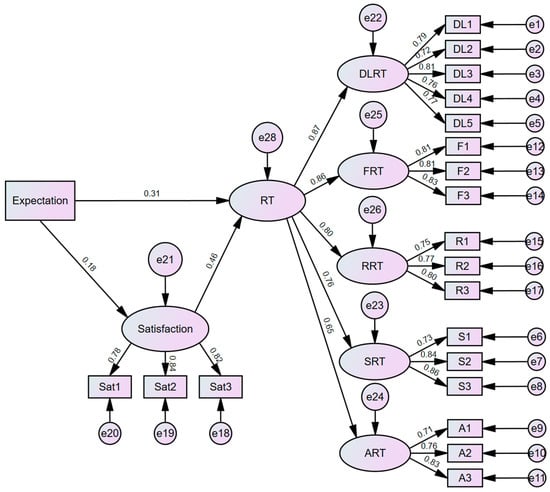

4.2. Construction of a Model for the Mechanism of Tolerance

This study utilizes Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the relationships among residents’ expectations, satisfaction, and tolerance in the context of CFC reformation. Additionally, it explores the mediating role of satisfaction between residents’ expectations and tolerance. The SEM analysis and fit index computations were performed using AMOS 26 software. The model fit was determined by various fit indices, including the Chi-Square, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and Normed Fit Index (NFI). As shown in Table 9, all the aforementioned fit indices met the fitting standards, indicating that the model fits well and the constructed structural equation model is ideal. The overall model is illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 9.

Overall model fit test.

Figure 3.

Output results of the SEM of CFCRT.

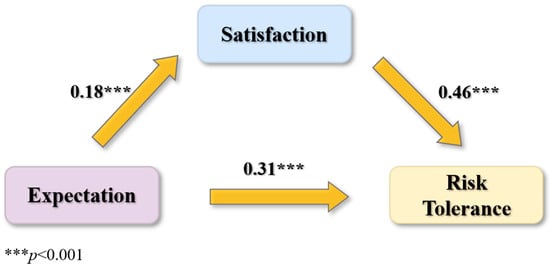

To more intuitively describe the relationship between satisfaction, expectation, and tolerance, the empirical results of the variable path relationships are presented in Figure 4. Residents’ expectations have a positive impact on tolerance, and satisfaction also has a positive impact on tolerance. Therefore, it confirms the validity of H1: expectations have a significant impact on satisfaction; H2: expectations have a significant impact on RT; and H3: satisfaction has a significant impact on RT.

Figure 4.

Relationships among Expectation, Satisfaction, and Risk Tolerance.

The results of the mediation effect test calculated using the bootstrap method are shown in Table 10. The total effect of expectations on tolerance is 0.389, with an indirect effect of 0.083 and a direct effect of 0.306. All results are significant at the 0.001 level, indicating a significant impact of expectations on tolerance. The proportion of the mediation effect is 21.34%, meaning the mediation effect of satisfaction accounts for more than one-fifth of the total effect of expectations on tolerance. Therefore, H4 can be validated: the indirect influence of expectancies on RT through the mediating role of satisfaction is also established.

Table 10.

Mediation effect test.

5. Discussion

5.1. The CFCTRT Mechanism: Dual Drivers of Expectation and Satisfaction

This study examines CFCTRT as a second-order factor, comprising five dimensions: SRT, DLRT, FRT, RRT, and ART. Statistical analyses of the model’s goodness of fit reveal a strong alignment with the data, confirming that these dimensions effectively represent CFCTRT. The DLRT exhibits the highest predictive capability of these dimensions, followed by FRT, RRT, SRT, and ART.

We also examined the relationship between satisfaction, expectations, and tolerance. The results indicate that the greater the residents’ expectations for developing a child-friendly community, the more they can tolerate certain risks during construction. High expectations reflect residents’ positive attitudes and strong demand for child-friendly transformations, making them more willing to accept the inconveniences and risks that may arise during the transformation process. High expectations are often accompanied by emotional identification with the vision of transformation, and this emotional bond can buffer the impact of negative experiences. When residents have high expectations for the transformed community, such as believing that the transformation can provide a safer play space for children and create a better living environment, they are more willing to endure the negative impacts brought by the transformation. Previous studies have also pointed out that the higher the level of residents’ expectations, the lower the complaint rate [109], which aligns with the conclusion of this study that high tolerance is also compatible.

The greater the satisfaction with the current residential community, the more tolerant individuals become of certain risks associated with the construction process. High satisfaction may indicate a resident’s strong sense of belonging and responsibility toward the community, which psychologically predisposes them to view reformation as a process of self-improvement rather than an externally imposed intervention. Previous studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between residents’ satisfaction with their community and their support for community affairs [110]. These findings suggest that enhancing community satisfaction improves the community environment and significantly enhances the impact of the transformation, thereby creating favorable socio-psychological conditions for the successful advancement of child-friendly community development initiatives.

This study further investigates the mediating role of satisfaction between expectations and tolerance. Specifically, high expectations do not directly and proportionally translate into high tolerance. The positive influence of expectations more reliably transforms into a willingness to tolerate only when residents already possess a certain level of satisfaction with their current living conditions. This mechanism is essential for narrowing expectation gaps and effectively managing public psychological expectations. In high-density urban communities, unreasonable expectations can lead to disappointment or even opposition during renovation if not correctly managed. Thus, establishing a connection between “reality and vision” through satisfaction management is crucial for enhancing residents’ tolerance and fostering public cooperation.

5.2. Risk Tolerance and Individual Differences Among Residents

In practical applications, examining the tolerance mechanisms in reforming child-friendly communities involves more than merely assessing the strength of these mechanisms across various dimensions and predicting overall tolerance. It also requires a comprehensive understanding of tolerance’s unique characteristics and interrelationships within each dimension. This paper is conducted from two distinct perspectives. It systematically examines the levels of risk acceptance and the degree of impact on residents during the transformation process by integrating structural equation modeling with statistical analysis. The following discussion addresses explicitly the factors of safety, daily life, economy, resources, and aesthetics.

The tolerance level in the safety dimension exhibits a “low tolerance-medium impact” characteristic. Data show that tolerance concerning safety issues is the lowest, particularly with females demonstrating significantly lower tolerance than males. Research indicates that safety is considered the most fundamental right of children [111]. Safety issues are typically the focal point of public concern; the public’s risk perception becomes significantly heightened when involving children’s safety. However, secondary models indicate a moderate association with CFCTRT, possibly because basic safety measures are generally established in most communities [112]. Such safety issues can also be addressed through specific technical means, such as enhanced monitoring [113] and optimized design. Furthermore, as safety is fundamental, public attention shifts to other higher-level needs once fulfilled.

Daily life’s dimension exhibits “moderate tolerance—high impact.” DLRT is at a moderate level, indicating that modifications are somewhat accepted. Notably, this dimension has the strongest correlation with the overall CFCTRT. This high correlation suggests that residents are acutely perceiving changes in daily life. Child-friendly modifications often involve public spaces, transportation, mobility convenience, and child participation, directly impacting residents’ routines and behaviors. As such, more significant changes tend to impact residents’ tolerance levels more. Tolerance of daily life is differentially associated with various social groups. Women, younger individuals, those with lower education levels, the unmarried, and renters generally demonstrate lower tolerance. This phenomenon may be attributed to the specific range of daily activities these groups engage in and their ability to adapt to environmental changes.

The financial dimension is characterized by “low tolerance-high impact”, significantly lower than most other dimensions, though slightly higher than the safety dimension. This behavior is evident in economic indicators such as housing prices and fiscal expenditures, particularly the fluctuations in the cost of living, which often capture immediate attention. Furthermore, this dimension exhibits the second-strongest connection to the CFCTRT, surpassed only by the daily life dimension. This connection may be attributed to the fact that costs related to renovations, maintenance expenses, and housing prices are acutely perceived in residents’ daily lives. Such costs influence residents’ vital interests directly and visibly, substantially affecting their overall attitudes. Notably, younger individuals, those who are unmarried, and renters display significantly lower tolerance levels. These groups typically face limited disposable income, reduced housing stability, and diminished expectations of long-term economic returns.

The resource dimension exhibits characteristics of “high tolerance-medium impact.” Residents tend to have a relatively high tolerance towards resource allocation issues, indicating a generally favorable acceptance. Although resource allocation is important, its impact on overall attitudes is less significant than that of daily life and economic aspects. This may be due to the partial mitigation of resource allocation issues through public space optimization and the transformation of existing idle spaces. Meanwhile, unmarried individuals and renters show significantly lower tolerance, possibly because they depend more heavily on public resources.

The aesthetic dimension exhibits characteristics of “high tolerance-low impact.” The ART is the highest among all dimensions, and its correlation strength with overall transformation tolerance is the weakest. It could be because residents have a “function-first” cognition, meaning aesthetics are not a key consideration. The unique environment of high-density communities also leads residents to focus more on functionality and practicality of space, while their sensitivity to aesthetic issues is relatively lowered. Additionally, it indicates that people find the modifications involving appearance, color, and landscape in child-friendly environment transformations generally aligned with their expectations. Aesthetic transformations typically do not involve the core interests of residents. Therefore, their impact on CFCTRT is minimal. Meanwhile, unmarried, childless individuals and renters demonstrate significantly lower tolerance, potentially due to diverse aesthetic preferences and weaker community identification.

5.3. Optimization Strategy for CFC Renovation Based on Resident Tolerance

Through analysis of the CFCRTR mechanism, this study reveals that residents’ support or opposition to renovation projects is influenced by their current community satisfaction and future expectations. It is closely related to their perception of risks across different dimensions and individual social attributes. Therefore, to ensure the prudent advancement of community renovation and broad-based acceptance, it is necessary to use tolerance as an entry point to develop more targeted and practical intervention strategies. Based on the empirical conclusions above, this study proposes four optimization paths: guiding expectations, enhancing satisfaction, implementing risk stratification management, and targeting key demographic responses. These paths provide more inclusive and precise strategies for renovating child-friendly communities.

5.3.1. Constructing a Tolerance-Based Policy Evaluation and Optimization Mechanism

Integrating RT into the policy evaluation framework for child-friendly communities serves as a vital socio-psychological indicator. This measure not only quantifies residents’ subjective acceptance but also underpins the refined and personalized implementation of community renovations. Practically, it is advisable to establish a dynamic mechanism encompassing tolerance surveys, intervention optimization, and reassessment within pilot projects. This approach will scientifically identify sensitive areas and acceptable thresholds for community residents, thereby creating a data-driven risk profile. Consequently, more inclusive design strategies and communication mechanisms should be implemented, particularly for groups or areas exhibiting low risk tolerance.

5.3.2. Strengthening Expectations to Stimulate Willingness for Transformation

Research has found that the higher the residents’ expectations, the greater their tolerance for the community renovation process and overall satisfaction with the community. High expectations reflect residents’ recognition of the renovation concept and serve as an important psychological impetus for the completion of the project. Therefore, before the initiation of renovation, it is crucial to help residents form a clear, reasonable, and achievable vision through diversified publicity, visualization of results, and public participation. This approach can prevent the resistance caused by cognitive discrepancies, enhancing their tolerance for the renovation.

5.3.3. Enhancing Satisfaction to Strengthen the Psychological Foundation

Satisfaction directly increases residents’ tolerance for redevelopment and is a crucial mediator between “expectation and tolerance.” Residents can only perceive future changes more positively if they are satisfied with their community’s current quality of life. To foster child-friendly community redevelopment, priority should be placed on enhancing the existing infrastructure, public services, and social networks. These improvements aim to increase residents’ convenience and sense of belonging. A particular emphasis should be on addressing residents’ satisfaction with their daily lives. This foundational satisfaction is a buffer against the uncertainty and anxiety associated with redevelopment, mitigates the perceived risks arising from expectation gaps, and ultimately promotes a stronger willingness to cooperate and a deeper emotional connection with the community.

5.3.4. Hierarchical Management Based on Risk Level

To address the “low tolerance” dimensions of safety and economy, it is crucial to enhance risk assessments and ensure information transparency before the commencement of any project. This approach ensures that during the construction phase, safety remains manageable and expenses are delineated, thereby reducing uncertainty and anxiety among residents, which often stems from insufficient knowledge. Specifically, for vulnerable groups such as women, low-income individuals, and renters, it is imperative to bolster safety plans and offer necessary economic compensation and life security. Given the significant impact of daily life dimensions on CFCTRT, the primary goal during the renovation process should be to preserve residents’ essential living functions, including maintaining ease of travel, access to recreational spaces, and uninterrupted use of daily activity venues. These objectives can be met by implementing staggered construction schedules, offering temporary alternative spaces, announcing construction plans in advance, and actively seeking residents’ feedback. Such measures are designed to minimize disruptions to everyday life while enhancing residents’ understanding of, engagement with, and support for the renovation project.

5.3.5. Focus on the Needs of Key Groups

The influence of attributes on the tolerance of residents shows significant differences. Differentiated communication plans should be devised during the implementation process, focusing on the core demands of residents with low tolerance. Female residents’ needs can be addressed by inviting female representatives to participate in the renovation design and prioritizing safety facilities. The benefits of child-friendly renovations should be emphasized for childless groups, such as greening enhancements and universal improvements in infrastructure, allowing them to perceive personal gains directly. A decision-making mechanism involving the joint participation of tenants and owners should be established for tenant groups, which could involve renovating shared spaces and implementing short-term welfare projects to enhance their sense of belonging.

5.4. Limitations and Prospects

This study explores the expected risk tolerance mechanisms in transforming child-friendly environments in high-density communities. Although some achievements have been made in theoretical construction and empirical analysis, several limitations warrant reflection and improvement in future research. Firstly, there is a lack of standardized measures and authoritative scales specifically for “resident risk tolerance,” particularly in transforming child-friendly communities. The questionnaire scale used in this study is mainly adapted from integrating and summarizing the existing literature. Although it has been validated regarding reliability and validity, it might still have incomplete measurement dimensions or insufficient capture of specific psychological mechanisms, thus lacking a certain level of authority.

Additionally, the sample selection primarily focuses on high-density communities in first- and second-tier cities. While these areas have strong representativeness and research value, differences in regional culture, economic development levels, and policy environments pose challenges in controlling sample variables, which may limit the sample’s representativeness and require further verification of the generalizability of the results. Again, this study employs cross-sectional data, which makes it challenging to reveal the dynamic changes in residents’ tolerance across different stages of renovation, such as preliminary design, construction implementation, and completion. This limitation restricts a deeper understanding of the mechanisms behind the evolution of residents’ attitudes.

Given the limitations, future research could be expanded and deepened in several areas. First, qualitative research methods could be incorporated to explore further factors influencing residents’ attitudes. For example, interviews could be conducted to ascertain specific reasons for residents’ low tolerance of particular dimensions, or case studies could be utilized to identify the key factors of successful renovation projects. Second, longitudinal studies should be conducted to analyze changes in residents’ attitudes at different stages of the renovation process. Additionally, individual-level tolerance could be examined in terms of physical environmental characteristics of communities, such as greening rates and the surrounding community environment. Moreover, a deeper theoretical framework could be developed by integrating multi-disciplinary perspectives from social psychology and policy studies to expand the research framework and contribute to building a more systematic and universally applicable risk assessment model for child-friendly community development. Ultimately, this research will offer robust theoretical support and practical guidance for future urban renewal policy-making.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically reveals residents’ risk tolerance and influencing mechanisms in CFC transformation through multidimensional exploration and empirical analysis of CFCTRT. The research findings indicate significant differences in residents’ risk tolerance across various demographic and social characteristics, such as gender, age, marital and parental status, and housing attributes. In particular, women, young people, individuals who are unmarried and childless, and renters generally exhibit lower tolerance levels. It is important to pay special attention to the perspectives of these groups during the renovation design process to enhance overall acceptance and fairness.

Residents exhibit varying tolerance levels and influences across five dimensions: safety, daily life, economy, resources, and aesthetics. Among these, safety tolerance is the lowest, yet its impact on overall tolerance is moderate. The daily life dimension shows moderate tolerance but has the highest influence. Economic tolerance is relatively low, but its influence remains quite significant. Resource-related tolerance is higher, with a medium level of influence. Aesthetic tolerance is the highest among all dimensions, yet its influence is the lowest.

This study also reveals that residents’ expectations and satisfaction regarding constructing CFC significantly affect their risk tolerance. Satisfaction enhances residents’ willingness to tolerate and mediates the relationship between expectations and tolerance, thus adjusting the transmission pathway. This finding suggests that merely promoting the vision for improvement is insufficient to increase tolerance; enhancing residents’ satisfaction with their current community environment is crucial. This enhancement builds a robust psychological foundation that adjusts expectations, thereby avoiding the pitfalls of high expectations leading to significant deviations.

In summary, this research theoretically advances the understanding of public acceptance mechanisms within community renewal studies by introducing the concept of “resident tolerance” into the evaluation system of CFC transformations for the first time, thus providing a novel analytical framework for urban renewal. Practically, the study offers targeted recommendations for CFC transformations, emphasizing the need to focus on core influencing dimensions, consider vulnerable groups, and optimize the linkage between expectations and satisfaction. These recommendations aim to ensure that community renewal progresses steadily on a fair, inclusive, and sustainable basis, achieving a harmonious integration of community renewal initiatives with residents’ needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and Y.S.; Methodology, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L., X.W. and Y.S.; resources, Y.S.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., X.W. and Y.S.; visualization, Y.L.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Beijing Forestry University Science and Technology Innovation Program Project, grant number BLX201732.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this research article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Beijing Forestry University (Grant No. BLX201732). We also extend our sincere thanks to the students who assisted in data collection and fieldwork, both online and offline, and to Tian for his valuable insights and helpful guidance during the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yao, M.; Yao, B.; Cenci, J.; Liao, C.; Zhang, J. Visualisation of High-Density City Research Evolution, Trends, and Outlook in the 21st Century. Land 2023, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Van Ameijde, J. The Impact of High-Density Urban Environments on Children’s Play, a Systematic Review of Current Insights. Cities Health 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, M. Community Life Regression Under the Background of Rapid Urbanization. In Building Resilient Cities in China: The Nexus Between Planning and Science; Chen, X., Pan, Q., Eds.; GeoJournal Library; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 113, pp. 63–73. ISBN 978-3-319-14144-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Yung, E.; Chan, E. Towards Sustainable Neighborhoods: Challenges and Opportunities for Neighborhood Planning in Transitional Urban China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S.B.; Bennetts, S.K.; Hackworth, N.J.; Green, J.; Graesser, H.; Cooklin, A.R.; Matthews, J.; Strazdins, L.; Zubrick, S.R.; D’Esposito, F. Worries, ‘Weirdos’, Neighborhoods and Knowing People: A Qualitative Study with Children and Parents Regarding Children’s Independent Mobility. Health Place 2017, 45, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, N.F.; Said, I. The Trends and Influential Factors of Children’s Use of Outdoor Environments: A Review. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. State of the World’s Children: Celebrating 20 Years of the Convention on the Rights of the Child; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-92-806-4442-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.; De Lannoy, A.; McCracken, D.; Gill, T.; Grant, M.; Wright, H.; Williams, S. Special Issue: Child-Friendly Cities. Cities Health 2019, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Pan, S. Policy Combinations, High-Quality Population Development, and China’s Economic Growth: An Endogenous Fertility Model. Econ. Model. 2025, 151, 107206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Declining Number of Births in China: A Decomposition Analysis. China Popul. Dev. Stud. 2021, 5, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabadi, M.T.; García, E.H.; Pourzakarya, M. Let Children Plan Neighborhoods for a Sustainable Future: A Sustainable Child-Friendly City Approach. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pia, N.A.; Bezboruah, K. Urban Design Strategies for Creating Child-Friendly Neighborhoods: A Systematic Literature Review. Cities 2025, 162, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Qian, Y. Collaborative Governance for Participatory Regeneration Practices in Old Residential Communities within the Chinese Context: Cases from Beijing. Land 2023, 12, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L. Parental Sacrifice, Filial Piety and Adolescent Life Satisfaction in Chinese Families Experiencing Economic Disadvantage. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, G. Key Variables for Decision-Making on Urban Renewal in China: A Case Study of Chongqing. Sustainability 2017, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.; Visscher, H.; Elsinga, M. Stakeholders’ Expectations in Urban Renewal Projects in China: A Key Step towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Fu, X.; Zhuang, T.; Wu, W. Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect Framework of Residents’ Responses to Urban Neighborhood Regeneration: The Case of Shanghai, China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 100, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweny, T.; Namusonge, G.S.; Onyango, S. Financial Attributes and Investor Risk Tolerance at the Nairobi Securities Exchange—A Kenyan Perspective. ASS 2013, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, J.W. Risk Aversion in the Small and in the Large. In Uncertainty in Economics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Grable, J.E.; Lytton, R.H. Investor Risk Tolerance: Testing the Efficacy of Demographics as Differentiating and Classifying Factors. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 1998, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Wang, S. Renovation Priorities for Old Residential Districts Based on Resident Satisfaction: An Application of Asymmetric Impact-Performance Analysis in Xi’an, China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebotareva, E. Life Satisfaction and Intercultural Tolerance Interrelations in Different Cultures. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 2015, 5, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tuu, H.H.; Olsen, S.O. Food Risk and Knowledge in the Satisfaction—Repurchase Loyalty Relationship. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2009, 21, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Effect of Expectation and Disconfirmation on Postexposure Product Evaluations: An Alternative Interpretation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1977, 62, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.C. Evaluating Indicators for Housing Policy: Residential Satisfaction vs. Marginal Improvement Priorities. Soc. Indic. Res. 1985, 16, 415–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Huang, Y. A Framework for Analyzing the Family Urbanization of China from a “Culture–Institution” Perspective. Land 2022, 11, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaube, V.; Remesch, A. Impact of Urban Planning on Household’s Residential Decisions: An Agent-Based Simulation Model for Vienna. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 45, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, E.; Warner, M. Planning for Family Friendly Communities. PAS Memo. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252196311_Planning_for_Family_Friendly_Communities (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Biggs, S.; Carr, A. Age- and Child-Friendly Cities and the Promise of Intergenerational Space. J. Soc. Work Pract. 2015, 29, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.S. Fostering Community Bonding in High—Density Habitations. In Future Urban Habitation; Heckmann, O., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 149–163. ISBN 978-1-119-73485-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. The Consequences of Living in High-Rise Buildings. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2007, 50, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S. Improving the Social Sustainability of High-Rises. CTBUH J. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Ghazzeh, T.M. Housing Layout, Social Interaction, and the Place of Contact in Abu-Nuseir, Jordan. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 41–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G.; Dempsey, N.; Power, S.; Brown, C. What Is ‘Social Sustainability’, and How Do Our Existing Urban Forms Perform in Nurturing It? Plan. Res. Conf. 2006, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, P.W.G.; Kenworthy, J.R. Gasoline Consumption and Cities: A Comparison of U.S. Cities with a Global Survey. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1989, 55, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Jiao, S.; Zhang, R. High-Density Communities and Infectious Disease Vulnerability: A Built Environment Perspective for Sustainable Health Development. Buildings 2024, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugera, S. Gezin Op Hoogte—High-living Families. Unpublished Bachelor’s Dissertation, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari, S.; Shepley, M. Psychological and Social Impacts of High-Rise Buildings: A Review of the Post-Occupancy Evaluation Literature. Hous. Stud. 2021, 36, 1147–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Explore Children’s Outdoor Play Spaces of Community Areas in High-Density Cities in China: Wuhan as an Example. Procedia Eng. 2017, 198, 654–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Witten, K.; Kearns, R. Housing Intensification in Auckland, New Zealand: Implications for Children and Families. Hous. Stud. 2011, 26, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Gu, N.; Paniagua, J.O.; Sivam, A.; McGinley, T. Investigating the Social Impacts of High-Density Neighbourhoods Through Spatial Analysis. In Computer-Aided Architectural Design. “Hello, Culture”; Lee, J.-H., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 264–278. [Google Scholar]

- Maritan, C.A.; Lee, G.K. Resource Allocation and Strategy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 2411–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Liu, C.; Ma, X. How Does Geographical Environment Affect Residents′ Perception of Social Justice: An Empirical Study from Low-Income Communities in Beijing. Cities 2025, 156, 105531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricios, N.N. The Neighborhood Concept: A Retrospective of Physical Design and Social Interaction. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2002, 19, 70–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space and Spatiality: What the Built Environment Needs from Social Theory. Build. Res. Inf. 2008, 36, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, K. Children’s Rights and the Crisis of Rapid Urbanisation. Int. J. Child. Rights 2015, 23, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P. Assessment of Child-Friendly Spatial Environment in Urban Communities Based on Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Eng. Res. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.B.; Brown, B.B. Walkable New Urban LEED_Neighborhood-Development (LEED-ND) Community Design and Children’s Physical Activity: Selection, Environmental, or Catalyst Effects? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, K.; Badland, H.; Kvalsvig, A.; O’Connor, M.; Christian, H.; Woolcock, G.; Giles-Corti, B.; Goldfeld, S. Can the Neighborhood Built Environment Make a Difference in Children’s Development? Building the Research Agenda to Create Evidence for Place-Based Children’s Policy. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D. Becoming Child-Friendly: A Participatory and Post-Qualitative Study of a Child and Youth Friendly Community Strategy. Doctoral Dissertation, University of British Columbia, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.T.; He, X.; Cheng, L.Y. Children’s Recreational Space Planning and Construction in High-density Cities. Planners 2022, 38, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, S.I.; Bakker, I.; van Mechelen, W.; Hopman-Rock, M. Determinants of Activity-Friendly Neighborhoods for Children: Results from the SPACE Study. Am. J. Health Promot. 2007, 21, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Dong, C.; Zhao, L. Research on Child-Friendly Renewal Strategy of Community Public Space from the Perspective of Inclusive Development. IRSPSD Int. 2024, 12, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, K.E.; Wood, L.J. “We Live Here Too” What Makes a Child-Friendly Neighborhood? In Wellbeing; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-1-118-53941-5. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, R. Child-Friendly Cities and Communities: Opportunities and Challenges. Child. Geogr. 2024, 22, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Huang, R.; Liu, G.; Shrestha, A.; Fu, X. Social Capital in Neighbourhood Renewal: A Holistic and State of the Art Literature Review. Land 2022, 11, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, H.; Thomas, S.; Sellstrom, E.; Petticrew, M. The Health Impacts of Housing Improvement: A Systematic Review of Intervention Studies From 1887 to 2007. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, S681–S692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Advantage or Paradox? The Challenge for Children and Young People of Growing Up Urban; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-92-806-4977-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, X.; Gao, B. Collaborative Decision-Making for Urban Regeneration: A Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Fertner, C.; Jiang, W.; Andersen, L.M.; Vejre, H. Understanding the Change in the Social Networks of Residential Groups Affected by Urban Renewal. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 98, 106970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.M.; Lee, C.C.; Yong, L.R. Impacts of Urban Renewal on Neighborhood Housing Prices: Predicting Response to Psychological Effects. J. Hous. Built Env. 2020, 35, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lu, X.; Hu, X.; Li, L.; Li, Y. What’s Wrong with the Public Participation of Urban Regeneration Project in China: A Study from Multiple Stakeholders’ Perspectives. ECAM 2022, 29, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Changing Neighbourhood Cohesion under the Impact of Urban Redevelopment: A Case Study of Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.S. Can Deprived Housing Areas Be Revitalised? Efforts against Segregation and Neighbourhood Decay in Denmark and Europe. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ye, C. Urban Renewal without Gentrification: Toward Dual Goals of Neighborhood Revitalization and Community Preservation? Urban Geogr. 2024, 45, 201–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. Gentrification in Changing Cities: Immigration, New Diversity, and Racial Inequality in Neighborhood Renewal. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2015, 660, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]