Abstract

Refugee settlements are often positioned around natural borders, which often have a heightened danger of environmental hazards. Here, we aim to better understand why settlements are in environmentally vulnerable land and what social and physical factors contribute to this phenomenon. To do this, we present a holistic narrative that maps climate threats among displaced populations in Cox’s Bazar district, Bangladesh, while contextualizing environmental vulnerability by incorporating historical and social constraints. Using ArcGIS, an online mapping program, we illustrate the overlap between different climatic events and how these vulnerabilities compound and intensify one another. We also discuss the history of natural migration and settlement pertaining to the physical landscape and the sociopolitical reasons refugees remain in environmentally vulnerable areas. Overall, we find an emerging trend that may be broadly applicable to instances of forced displacement; physical settlement locations near international borders demarcated by landforms may be more vulnerable to the effects of climate change and extreme climate events. However, physical, social, and political reasons often cement these locations. Recommendations include enhancing the resilience of refugee camps through infrastructure improvements, sustainable land management, and reforestation efforts, which would benefit both the environment and local and refugee communities.

1. Introduction

Climate change is a global threat, exacerbating the frequency and intensity of natural hazards such as floods, droughts, cyclones, landslides, and wildfires. These hazards, however, do not impact everyone equally; vulnerable populations, especially refugees, are disproportionately affected by extreme weather conditions [1]. To better understand why this phenomenon exists, we sought to focus on Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, which hosts over 1 million refugees as of April 2025 [2] and is one of the largest global concentrations of displaced persons [3]. The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) designates displaced persons as “Persons of Concern” (POC), including individuals who are asylum-seekers, refugees, stateless persons, the internally displaced, and returnees [4].

The forced displacement of the Rohingya people to Cox’s Bazar district is impacted by multiple social, physical, and climatic factors. Here, we seek to better understand the vulnerability to environmental changes of displaced persons in Cox’s Bazar, focusing on the physical spaces they inhabit, combined with an understanding of refugees’ historical and social constraints. Specifically, we first describe the historical roots of Cox’s Bazar as a settlement location for refugees. We next assess the risk of adverse climate events and environmental changes in liminal international river-border plains to refugees in settlements and in the refugee journey. Finally, we discuss the social factors associated with remaining in environmentally vulnerable locations. Following the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2022), we define environmental vulnerability as the degree to which an ecosystem is susceptible to natural hazards and the (in)ability to self-restore, adapt, or cope with the impacts of climate change [5].

Cox’s Bazar district is situated on the southeast peninsula of Bangladesh (the Teknaf Peninsula) in the Chittagong division, near the international border with Myanmar. Refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar are exposed to extreme weather events. In 2019, heavy rains and winds displaced over 2700 people and left two people dead [6,7]. In 2023, Cyclone Hamoon made landfall in Cox’s Bazar, impacting over 470,000 people, including almost 2500 Rohingya refugees [8]. A recent cyclone risk analysis of Cox’s Bazar implemented the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and Geographic Information System (GIS) data to identify specific camps with higher risk levels, while a recent landslide risk assessment of a Rohingya refugee settlement area in Cox’s Bazar relied on AHP and geospatial techniques [9,10]. The physical space of the Cox’s Bazar camps is also surrounded by vegetation and forests, which supply timber as a critical building and fuel resource for the refugees [11,12,13,14,15]. In Cox’s Bazar, around 750,000 kg of fuelwood is required every day, and it is estimated that over 5000 acres of dense forest have been lost [11]. Deforestation caused by the refugees’ need for firewood and land for settlements has also further degraded the environment. Reducing forest cover has led to soil erosion, loss of wildlife habitats, and increased vulnerability to landslides. This depletion of natural resources, including subsurface water supplies, has also had severe implications for both the refugees and the local population [15,16,17].

These studies demonstrate how analyzing geospatial data can provide important insights into environmental vulnerability and land use. Here, we develop a holistic climate narrative that not only maps Bangladesh’s country-wide climate threats but also contextualizes the environmental vulnerability of Cox’s Bazar. We discuss the history of natural migration and settlement pertaining to the physical landscape, along with the social and political reasons they remain in these environmentally vulnerable areas.

Historical Context

The Rohingya people have a long history of inhabiting both the Rakhine State of Myanmar (previously the Arakan state of Burma) and the Chittagong region of Bangladesh. Located on the southern tip of the Teknaf Peninsula in southeast Bangladesh, Cox’s Bazar is a small coastal town known for its long pristine beaches, shrimping and fishing in the Naf River, and its remarkable biodiversity [12].

There have been six major periods of movement from Myanmar into Bangladesh: the late 1700s, the early 1800s, the 1940s, 1978, 1991/92, and current day [18]. Initial displacements of the Rohingya into present-day Cox’s Bazar district date to 1784 when Burmese forces invaded Arakan, causing a mass exodus of the Rohingya into the Chittagong region [18,19]. The Anglo-Burmese War in 1824 further fueled migration, leading to another widespread displacement [20]. The promise of arable land under the ‘Wasteland Rules of 1838’ attracted many Rohingya people to Chittagong [20]. Francis Buchanan, a medical doctor and botanist who documented the movement and existence of Rohingya settlements in Burma during the precolonial period, found that the Rohingya settled on both banks of the Naf River, demonstrating that their history is intertwined with displacements back and forth across the Naf River [20]. The Rohingya continued to face periodic displacements throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The UNHCR repatriated many of the refugees, and by 2003, only two of the original twenty camps in Cox’s Bazar were still functioning: Nayapara camp near Teknaf and Kutupalong camp near Ukhia [21]. Within these megacamps are multiple subcamps [6]. As of April 2025, there are over 1 million refugees across the 33 subcamps in Cox’s Bazar managed by the Bangladesh Government and the United Nations [2]. Since 2021, just over 37,000 refugees have been relocated to Bhasan Char, an island in the Noakhali district, as a government project to decongest camps [2].

The Rohingya thus have deep historical roots in and around this region, and their connection to the land and people remains a potential factor for current-day migrants choosing to move. To this day, Cox’s Bazar remains a chosen settlement location for many, and while it began as an unforced settlement, the Government of Bangladesh reinforces Cox’s Bazar as a location for refugee settlements [14,18].

Informed by our analyses, we discuss potential strategies for improved climate resilience of settlements, encompassing the capacity of both natural and built environments to withstand and recover from extreme weather events. Specifically, we define climate resilience as the ability of land and infrastructure systems to adapt to, and rapidly recover from, climate-related stressors while maintaining essential functions [22]. As such, we recognize that any solutions will require international support and must consider the impracticality of simply relocating settlements; instead, solutions must work towards improving the resilience of the land and developing sustainable infrastructure to minimize deaths and damages. Such efforts can improve the climate resilience of the Teknaf Peninsula and refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar.

2. Materials and Methods

ArcGIS (Geographic Information System) Pro 3.4 was used for all figures to conduct basic quantitative spatial analysis techniques to identify climate-related threats and evaluate their potential impact on refugee settlements. The ArcGIS platform has native data sources hosted by Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri), authoritative external data sources from government agencies and scientific organizations, and the option to incorporate user-provided data. A north arrow, scale bar, and legend were incorporated into all figures for spatial reference. Full details on the data and basemap used below are provided in Table S1.

To analyze drought and flood conditions affecting refugee settlements, Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) data, obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, Tables S1 and S2), were processed in ArcGIS Pro 3.4 to classify areas into drought-prone and flood-prone zones. UNHCR Persons of Concern (POC), sourced from UNHCR and government datasets, were overlaid onto the SPI raster to assess their exposure to these climatic extremes [2]. A spatial analysis was conducted to determine the proportion of refugee sites located in extreme drought or flood conditions.

To analyze the vulnerability to flooding following tropical storms, storm surge datasets, the most recent UNHCR POC sites (2025), and flood risk metrics were extracted to cover Bangladesh. The data were arranged such that the surge data were on top, while the risk data were below to make sure that all other datasets became visible. Flood risk was categorized through the symbology option properties to categorize the level of risk it posed to the specific geographic location.

To analyze the naturally flowing geography of the Teknaf Peninsula, the cities and towns of Bangladesh, elevation changes, districts, recent cyclones, and the UNHCR POC sites were extracted, clipped by mask, and overlaid depending on whether the data were vector or raster.

3. Results

Using ArcGIS Pro 3.4 [23], we evaluated the environmental vulnerability of Cox’s Bazar. Specifically, we performed a spatial analysis of Bangladesh consisting of three interrelated maps illustrating various climate vulnerabilities (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) and determined the natural physical stressors. Each of the three maps specifically shows the international border of Bangladesh and the locations of Persons of Concern (POC), as documented by the UNHCR.

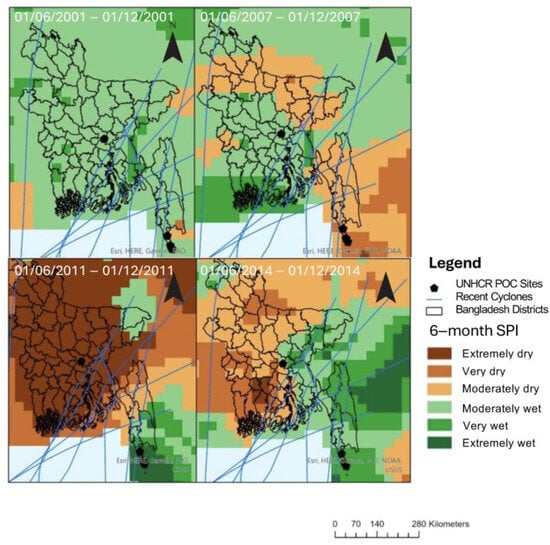

Figure 1.

SPI trends and cyclone activity in the Bangladesh region. Mapping shows a time series of the global Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and previous cyclone paths. The 6-month SPI (1981−present) illustrates rainfall through 6 various classifications ranging from extremely dry, very dry, moderately dry, moderately wet, very wet, and extremely wet, visualized by colors ranging from dark brown to dark green, respectively. Figure created with ArcGIS Pro 3.4.

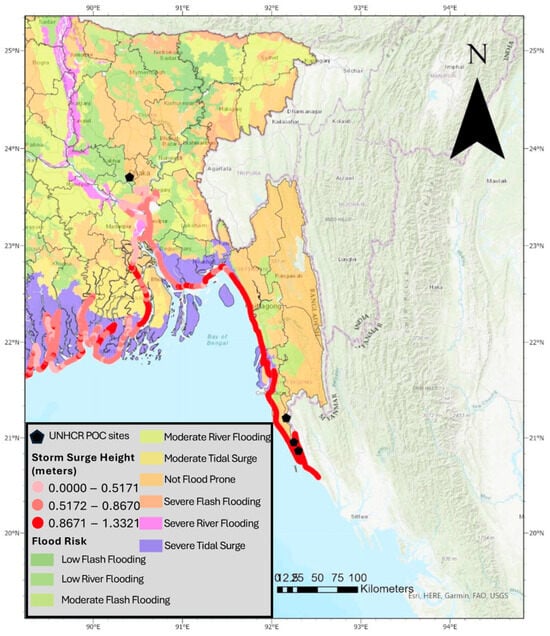

Figure 2.

Coastal flood risk of Bangladesh. This map combines storm surge index and flood risk, which gives insight into how the land is affected by storms. Figure created with ArcGIS Pro 3.4.

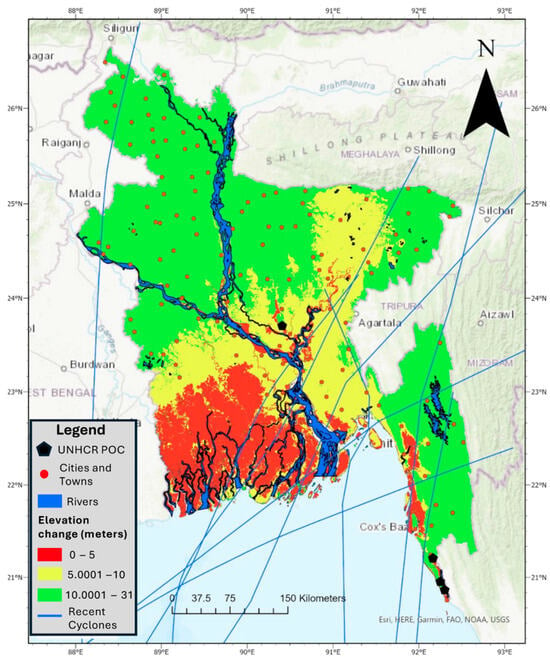

Figure 3.

Elevation changes of Bangladesh. This map highlights the river layout of Bangladesh, with pre-existing flow paths of water shown. This map includes the UNHCR POC sites, the location of major towns and cities of Bangladesh, and recent cyclones that have affected the region. Figure created with ArcGIS Pro 3.4.

3.1. Geography

The Chittagong region has a diverse topography of hills, forests, rivers, and the longest continuous natural sea beach in the world. Cox’s Bazar district extends to the southern tip of the Teknaf Peninsula, nestled between an extensive beach coastline and the Naf River, which also serves as an international border between Myanmar and Bangladesh [12]. There are currently 33 subcamps clustered throughout Cox’s Bazar, which are predominantly located on the eastern side of the peninsula against the border [2]. There are two primary clusters of camps in Cox’s Bazar, one in Ukhia and the other in Teknaf.

3.1.1. Standard Precipitation Index

Analysis of the global Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) from 1981 to present, along with previous cyclone paths and recent hurricanes, cyclones, and typhoons (Figure 1, Table S2), revealed this region undergoes ‘extremely wet’ or ‘very wet’ periods followed by ‘very dry periods’, which can cause soil degradation and increases the likelihood of flooding and landslides [10]. We also observed that cyclones are particularly impactful in this area; the Chittagong region between 2019 and 2024 has already been struck by 10 storms in the region, ranging in intensity from Category 5 storms to tropical storms [24]. Storms such as Cyclone Amphan and Mocha greatly impacted the Cox’s Bazar refugee sites; these storms obliterated the poorly made houses and infrastructure of the area and left refugees in a vulnerable state, devoid of basic human necessities at the most trying of times [25]. This problem is further exacerbated by the clear-cutting of hectares of land for camp construction and other uses, which promotes erosion, increasing the severity of landslides and vulnerability to monsoon and flood waters [16].

3.1.2. Storm Surge Index and Flood Risk

Next, we investigated storm surge index and flood risk (Figure 2). Flood risk uses Synthetic Aperture Radar data acquired by Copernicus Sentinel-1, which was analyzed by the Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS) ARIA-SG team alongside NASA-JPL and Caltech (Table S1). This shapefile shows areas that are likely to flood in Bangladesh due to heavy rains, especially during and following storms. The flood risk shown in this map represents a risk for more than just storm flooding, and when grouped with rainfall metric (Figure 1), it can be used to better track and estimate fluvial and pluvial flood risk. As storms intensify with worsening climate change, it can be expected that this storm surge model will accurately represent, or possibly under-represent, the susceptibility of refugee camps to tidal waves and coastal flooding. Just as vulnerabilities compound, flood risk compounds as well; flooding in 2021 caused over 11,000 shelters to be damaged or destroyed, displacing 24,000 refugees in the camps [26]. We found that Cox’s Bazar and Persons of Concern have a more limited risk of flash and river flooding but an increased storm surge and coastal flooding risk, which will be further worsened as clear-cutting and infrastructure development continue (Figure 2).

3.1.3. Elevation and River Runoff

Finally, we expanded our analyses to highlight elevation in Bangladesh (Figure 3) and low-lying floodplains along the River Naf. The drastic shift in elevation on the Teknaf Peninsula is visible on this map, which is critical to understanding the risk of increased runoff. As the water flows down the Chittagong Hill Tracts, it compounds and intensifies. This map also incorporates the river layout of Bangladesh, where the pre-existing flow paths of water are shown, which can intensify and exacerbate during any flooding event. This map includes the UNHCR POC sites, the location of major towns and cities of Bangladesh, and recent cyclones that have affected the region. While each mapping analysis highlights specific environmental stressors, it is the interplay of all factors that will cause further displacement and destruction in an already susceptible area.

4. Discussion

Here, we found that, in Bangladesh, UNHCR POC sites in Cox’s Bazar district are in an environmentally vulnerable location (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). Observing the SPI and waterways of Bangladesh (Figure 1 and Figure 3) revealed a feedback loop that will continue to degrade and erode the soil, ultimately leaving refugees in the direct path of storms with no natural protective barriers. Cox’s Bazar also experiences precipitation that exceeds the statistical averages by more than two standard deviations, which is considered extreme, and has a high risk of coastal flooding (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The two clusters of camps (Nayapara camp near Teknaf and Kutupalong camp near Ukhia) face similar environmental and social risks; however, the Teknaf cluster was found further south, closer to the flood plains of the Naf River. While the two areas are geographically very similar, the camps in Teknaf face heightened threats compared to the Ukhia camps because of the lower coastal elevation and proximity to waterways (Figure 3). Consequently, this increased vulnerability to extreme weather events and natural hazards also increases the risk of secondary displacement due to climatic factors.

Rohingya refugees also face adversity traveling to Bangladesh, crossing the Naf River, and finally arriving in Cox’s Bazar. Upon arrival, the refugees’ restricted movement traps them in the floodplains and environmentally vulnerable locations, which is intensified by being located directly on an international river border [27,28]. Indeed, this river border plays an important aspect not only in the vulnerability of the settlement but in the journey itself, which will also be worsened by climate change [29]. The River Naf, the width of which ranges between 1.61 and 3.22 km, begins in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and ends in the Bay of Bengal. This river forms the international border between Bangladesh and Myanmar and has been a critical crossing point for the Rohingya into Bangladesh. As Figure 2 and Figure 3 depict, the river’s basin is prone to coastal flooding, making it a hazardous route for refugees. Figure 1 illustrates the alternating cycle between dry and wet periods in the region. This climatic volatility is a primary driver of erosion risk, which is linked to fluctuations of rainfall and river activity, especially in flood-prone, low-lying coastal regions [30,31]. Riverbank erosion will also increase the length and subsequent risk of the crossing itself. Migrants arrive on the riverbank to a makeshift fleet of poorly constructed and overcrowded boats [32]. Crossing in these boats has proven deadly, and as climate change affects both the journey to the river and the river crossing itself, an unfortunate history of capsizing, sinking, and being swept away has led to an increase in fatalities. Furthermore, climate change may lead to the Naf River flowing faster, increasing the intensity and difficulty of river crossings [33].

Lack of adequate shelter and infrastructure in camps also makes refugees particularly susceptible to climate vulnerability. Because climate change is a less tangible risk, refugees cannot focus on long-term suitability and instead choose to combat the direct, more tangible threats of violence [1,26]. While the camps are nonetheless politically dangerous for the Rohingya, the presence of the community and the promise of international aid may outweigh the environmental risks.

Factors Associated with Remaining in Environmentally Vulnerable Locations

Over time, political instability and natural climate cycles have tied the Rohingya people to the floodplains of the River Naf [19]. The organization of established settlements with active NGOs providing goods and services, including healthcare, led to these locations being the only viable and practical options. The social isolation and marginalization of the Rohingya in these camps further hinder their ability to move and integrate into the local communities and access opportunities for education and employment [18,20,27,34]. Bangladesh, like other refugee-hosting countries, has become more restrictive to refugees over time [11,18,20,21,28,35,36]. There are economic sanctions in place that inhibit refugees’ ability to work outside of the camps [37]. Without economic opportunity, refugees are not able to provide for themselves and remain reliant on international aid [17,38]. There are also restrictions on movement in and out of these camps, with curfews and checkpoints that limit refugee assimilation into the local society [39].

Furthermore, the social and cultural identity of refugees is under threat. Myanmar has offered a tedious conditional reentry; however, the Rohingya people would have to relinquish their cultural claim as a Rohingya person and become citizens of Myanmar [20]. If the Rohingya people decide to abandon their homeland, their cultural heritage and history are at risk of extinction. By remaining local, the Rohingya assert their cultural identity to preserve their autonomy [14].

Specific to the migration journey itself, while the journey itself is physically taxing, the fee to cross is a major hurdle, especially for those who have been involuntarily long-term unemployed, prices can range from BDT 2000 (USD 24) and BDT 10,000 (USD 120), which, for many, is impossible to pay and requires bartering or third party assistance from offshore donors, faith-based groups, and remittances from other Rohingya people [32]. Thus, there may not be resources to travel further than the borderlands.

The Rohingya’s displacement to environmentally vulnerable areas (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3), combined with social and logistical constraints, creates another feedback loop that increases their vulnerability to climate change. Their restricted movement strains the region’s natural resources and limits the adaptive capacity. The refugees’ lack of legal status and limited access to resources hinder their ability to adapt to changing conditions, and environmental vulnerability is compounded by inadequate infrastructure and poor living conditions. Any solution must thus consider the interplay of social, physical, and environmental factors. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach that includes improving infrastructure, providing sustainable resources, and ensuring refugee legal protections.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we described the historical roots of Cox’s Bazar as a settlement location for refugees, assessed environmental vulnerability and the risk of adverse climate events of refugees in settlements and the refugee journey, and discussed the social factors associated with remaining in environmentally vulnerable locations. Overall, we found an emerging trend that may be broadly applicable to instances of conflict-driven forced displacement; physical settlement locations near international borders demarcated by rivers are vulnerable to the effects of climate change and extreme climate events (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). However, settlements naturally occur and stay near these borders for physical, social, and political reasons [29]. Thus, by using the specific example of Cox’s Bazar to view other climate-vulnerable settlements, a societal fault emerges that leads to the ostracization of stateless communities to out-of-sight borderlands with increased environmental vulnerability [27].

While relocating settlements to less vulnerable locations is—and should be—the most appropriate solution, we recognize that political realities on the ground often make that intervention unlikely (especially in the short term). Addressing the Rohingya’s environmental vulnerability requires solutions that consider the underlying social, physical, and environmental realities.

Adding ecological resilience to the land itself can provide broad protection that is not specific to refugees but encompasses overall climate change protection. Implementing an adequate drainage system could help alleviate the stress of flooding, the most prominent issue in this geographic region. Additionally, reforestation efforts and sustainable land management practices can help mitigate the environmental impact of the refugee settlements. Given that Cox’s Bazar is a popular tourist destination due to its long natural beach, increased land protection may be a solution that is more attractive to the host country. Cox’s Bazar’s coastline, once protected by 20-foot-high sand dunes, had the capacity to shield the coastal communities. However, as the dunes have eroded and shrunk over the last twenty years, protection capabilities have significantly decreased to the point where storm surges and tidal waves easily breach the shores. The dunes must be protected and restored, both to help combat storm surges and to protect biodiversity as well. For example, the local seaweed, Sagarlata, grows in abundance on the beaches of Cox’s Bazar; it provides stability and rigidity deep within the dunes and is an incredibly resilient plant [40]. Replanting Sagarlata is a bottom-up effort that will strengthen the resiliency of the land to storm surges. These small-scale efforts, while they oftentimes seem trivial when thinking of the vulnerability to natural hazards of displaced persons, are still imperative efforts that must be made [12]. In the long term, addressing the root causes of displacement is essential.

While the focus of this study is on Cox’s Bazar, we believe that our findings can be extrapolated to future migration scenarios, highlighting the need for proactive measures to address the impacts of climate change on displaced populations. As it is unlikely that entire settlements will relocate, and there is a propensity for settlements to form and remain along natural borders for multiple reasons, one potential solution is to improve the infrastructure within the refugee camps to withstand climatic events. There are overarching needs to improve the existing infrastructure, build flood-resistant shelters, improve drainage systems, and ensure access to clean water and sanitation facilities. Making sure that shelters and the infrastructure in Cox’s Bazar (or other similar high-risk locations) can withstand the intense storms, frequent rainfall, and seasonal flooding will greatly improve the resilience of camps. Currently, no sustainable housing has been constructed that can withstand the ever-present climate threats. One sample solution is shippable, portable housing; with the development of prefab homes, it is possible to quickly and relatively easily set up housing better suited to withstand the elements, providing stronger and more resilient shelters to refugees [41]. The lack of long-term infrastructure, however, only elevates current and future risks, as areas with inadequate housing in very vulnerable locations are prone to degradation and force secondary climate-driven movement [41].

Overall, this paper explores how environmental vulnerability and forced displacement are interconnected and often exacerbate one another. A comprehensive approach is needed to mitigate the impacts of the risks of climate change on displaced populations. By understanding the multifaceted challenges faced by the Rohingya, we can work towards more effective and sustainable solutions. Here, we argue that addressing the environmental vulnerability of displaced populations would require a holistic assessment by multiple stakeholders, including community members, environmental scientists, architects, urban planners, and policy makers, considering the social, physical, and environmental factors at play. Practical solutions must be developed to improve the living conditions and adaptive capacity of both refugees and the land to climate change while also addressing the root causes of displacement. Moreover, given that there is a propensity for settlements to occur and remain along natural borders for multiple reasons, similar solutions will likely apply to many instances of forced displacement. International cooperation and support are crucial to creating sustainable solutions that protect vulnerable groups and promote environmental resilience.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14071448/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D., C.C. and M.H.Z.; methodology, J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.; writing—review and editing, J.D. and C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the generous support from the Center on Forced Displacement at Boston University for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the ArcGIS Online repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| POC | Persons of Concern |

| SPI | Standardized Precipitation Index |

References

- Fransen, S.; Werntges, A.; Hunns, A.; Sirenko, M.; Comes, T. Refugee Settlements Are Highly Exposed to Extreme Weather Conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2206189120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR. Operational Data Portal: Bangladesh. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/bgd (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Marsh, J. Impact of Climate Change on the Migration and Displacement Dynamics of Rohingya Refugees; Danish Refugee Council: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Available online: https://mixedmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/334_Research-Report-Climate-Change-Rohingya.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- UNHCR. The Protection Induction Programme Handbook; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/44b4f9f42.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; Okem, A.; Officer, S.; Rama, B.; Belling, D.; Dieck, W.; Götze, S.; Kersher, T.; et al. Technical Summary Frequently Asked Questions Part of the Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-929-1691-616. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, S.; Sammonds, P.; Ahmed, B.; Rahman, T. Disaster Risk Reduction in Conflict Contexts: Lessons Learned from the Lived Experiences of Rohingya Refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thousands Displaced as Monsoon Rains Pound Rohingya Camps. Available online: https://www.iom.int/news/thousands-displaced-monsoon-rains-pound-rohingya-camps (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Bangladesh: Cyclone Hamoon Ravages Cox’s Bazar as a Severe Cyclonic Storm, Affecting over 450,000 Lives and Damaging 13 IRC Learning Centres. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/bangladesh-cyclone-hamoon-ravages-coxs-bazar-severe-cyclonic-storm-affecting-over-450000-lives-and-damaging-13-irc-learning-centres (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Sami, M.S.; Hoque, M.A.A.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Pradhan, B. Spatial Landslide Risk Assessment in a Highly Populated Rohingya Refugee Settlement Area of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Asian Geogr. 2024, 42, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Sammonds, P.; Ahmed, B. Cyclone Risk Assessment of the Cox’s Bazar District and Rohingya Refugee Camps in Southeast Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, S.K.; Saroar, M.; Chakraborty, T. Navigating Nature’s Toll: Assessing the Ecological Impact of the Refugee Crisis in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.M.; Smith, A.C.; Walker, K.; Rahman, M.K.; Southworth, J. Rohingya Refugee Crisis and Forest Cover Change in Teknaf, Bangladesh. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, R.; Karuppannan, S.; Kellett, J. Climate Migration and Urban Planning System: A Study of Bangladesh. Environ. Justice 2011, 4, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Crisis Group. A Sustainable Policy for Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh; International Crisis Group: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.T.; Sikder, S.K.; Charlesworth, M.; Rabbi, A. Spatial Transition Dynamics of Urbanization and Rohingya Refugees’ Settlements in Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 2023, 133, 106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, P. Nexus Dynamics: The Impact of Environmental Vulnerabilities and Climate Change on Refugee Camps. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 2024, 4, kgae001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Islam, M.T.; Alam, M.S.; Hussain, M.; Haque, M.M. An Assessment of the Sustainability of Living for Rohingya Displaced People in Cox’s Bazar Camps in Bangladesh. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 2022, 7, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. Burma/Bangladesh Burmese Refugees in Bangladesh: Still No Durable Solution. 2000. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2000/05/01/burmese-refugees-bangladesh/still-no-durable-solution (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Ullah, A.A. Rohingya Refugees to Bangladesh: Historical Exclusions and Contemporary Marginalization. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2011, 9, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. Myanmar’s Rohingya Genocide: Identity, History and Hate Speech; I.B. Taurus: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Medecins Sans Frontieres. Timeline: A Visual History of the Rohingya Refugee Crisis. Available online: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/latest/timeline-visual-history-rohingya-refugee-crisis (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- OECD. Infrastructure for a Climate-Resilient Future; OECD: Paris, France, 2024; ISBN 9789264421943. [Google Scholar]

- Esri ArcGIS Online 2024. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- World Data. Cyclones in Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.worlddata.info/asia/bangladesh/cyclones.php (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- ACAPS. CRISIS IMPACT OVERVIEW. 2023. Available online: https://www.acaps.org/en/countries/archives/detail/impact-of-cyclone-mocha (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Calabria, E.E.; Jaime, C.; Shenouda, B.; Haga, C. Anticipatory Action in Refugee and IDP Camps: Challenges, Opportunities, and Considerations; Climate Center: The Hague, Netherlands, 2022; Available online: https://www.climatecentre.org/wp-content/uploads/Anticipatory_Action_in_Refugee_and_IDP_Camps.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Hossain, M.; Idrish, B.; Khatun, H. Rohingya Refugees: Assimilation with Host Community and Socio-Politic al Impact on Cox’ s Bazar; Department of Geography & Environment, University of Dhaka: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Faruk Al Imran, H.; Nannu Mian, M. The Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh: A Vulnerable Group in Law and Policy. J. Stud. Soc. Sci. 2014, 8, 226–253. [Google Scholar]

- Coniglio, N.D.; Peragine, V.; Vurchio, D. The Geography of Displacement, Refugees’ Camps and Social Conflicts. World Bank. 2022. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/832121648043706062/pdf/The-Geography-of-Displacement-Refugees-Camps-and-Social-Conflicts.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Rahman, M.; Rafi, M.K.H.; Tasmim, N.; Islam, M.M.; Raju, M.R.; Karim, M.R. Unveiling the Wrath of Erosion: Assessing the Impacts of Soil Erosion on the Coastal Region of Bangladesh. IUBAT Rev. 2023, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazneen Aktar, M. Impact of Climate Change on Riverbank Erosion. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. (IJSBAR) 2013, 7, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- A Deadly Crossing. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/graphics/MYANMAR-ROHINGYA/010051JR3GY/ (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Sindall, R.; Mecrow, T.; Queiroga, A.C.; Boyer, C.; Koon, W.; Peden, A.E. Drowning Risk and Climate Change: A State-of-the-Art Review. Inj. Prev. 2022, 28, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norwegian Refugee Council. Strengthening Environmental Screening Capacity of Humanitarian Organizations Environmental Screening Report ROHINGYA REFUGEE CAMP; Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. 2023. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/environmental-screening-report-neat-sunamgonj-sylhet-bangladesh (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Mcadam, J.; Saul, B. Displacement with Dignity: International Law and Policy Responses to Climate Change Mitigation and Security in Bangladesh. In 53 German Yearbook of International Law 233 MLA; Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, K.L.; Al-haddad, R.; Ahmed, S. Considering the Shrinking Physical, Social, and Psychological Spaces of Rohingya Refugees in Southeast Asia. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2023, 4, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipski, M.J.; Rosenbach, G.; Tiburcio, E.; Dorosh, P.; Hoddinott, J. Refugees Who Mean Business: Economic Activities in and Around the Rohingya Settlements the Rohingya Settlements in Bangladesh. J. Refug. Stud. 2021, 34, 1202–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. Myanmar: Mass Detention of Rohingya in Squalid Camps. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/08/myanmar-mass-detention-rohingya-squalid-camps (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Human Rights Watch. Bangladesh: New Restrictions on Rohingya Camps. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/04/bangladesh-new-restrictions-rohingya-camps (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Zahid, H.; Sagarlata, S. Sand Dunes Disappearing from Cox’s Bazar Beaches. Available online: https://today.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/print/sagarlata-sand-dunes-disappearing-from-coxs-bazar-beaches-1654961386 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Prefabex. Prefabex Refugee Camps. Available online: https://www.prefabex.com/our_galleries/refugee-camps (accessed on 24 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).