Understanding Local Perspectives on the Trajectory and Drivers of Gazetted Forest Reserve Change in Nasarawa State, North Central Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- What are the socioeconomic characteristics of the sampled households from communities living near the gazetted forest reserves?

- (ii)

- What are the perceived direct and indirect drivers of forest change in forest-dependent communities, and how do these differ across the three forested regions in the state?

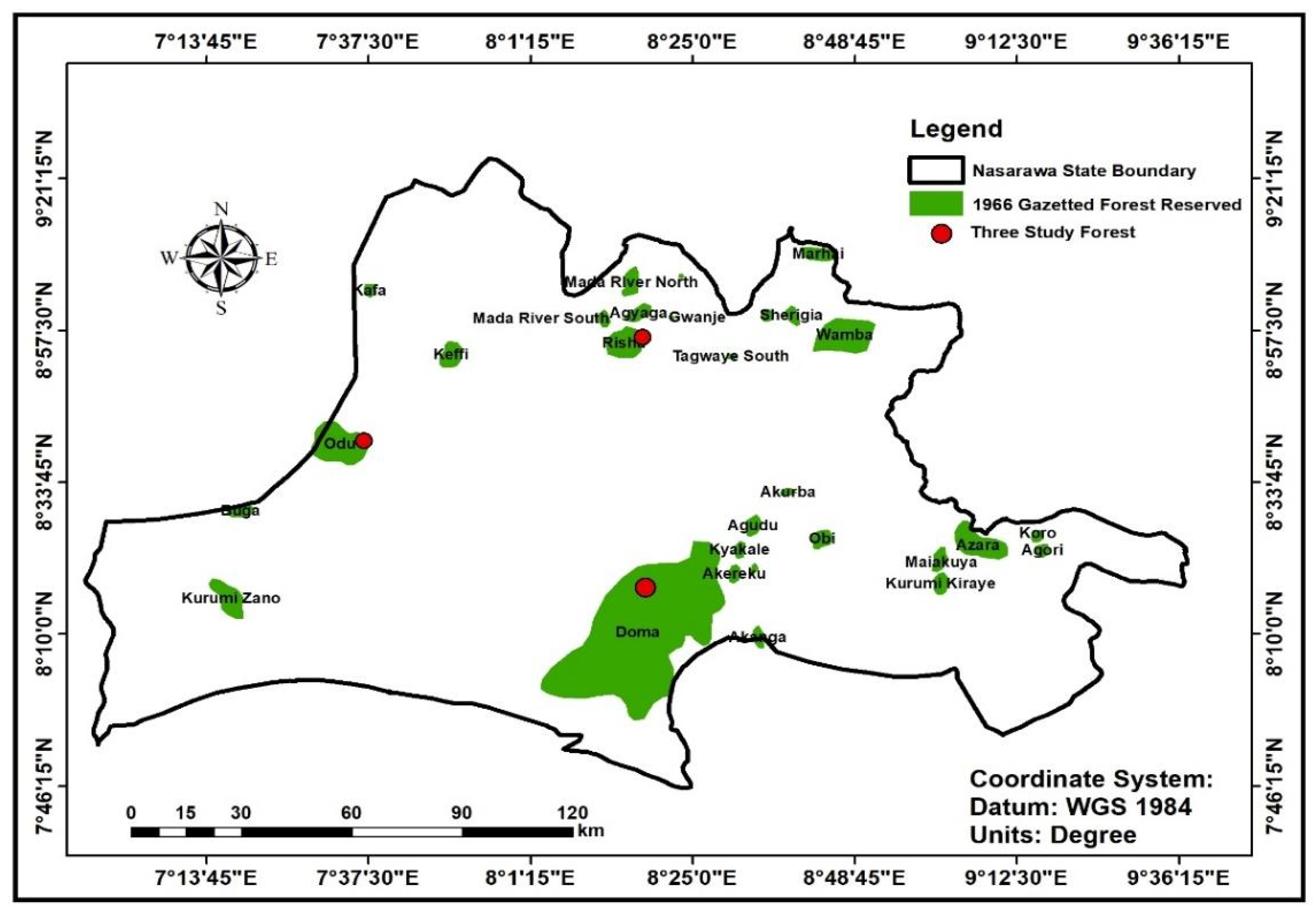

2. Research Design and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Methodology

2.1.1. Household Survey

2.1.2. Key Informant Interviews (KIIs)

2.1.3. Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

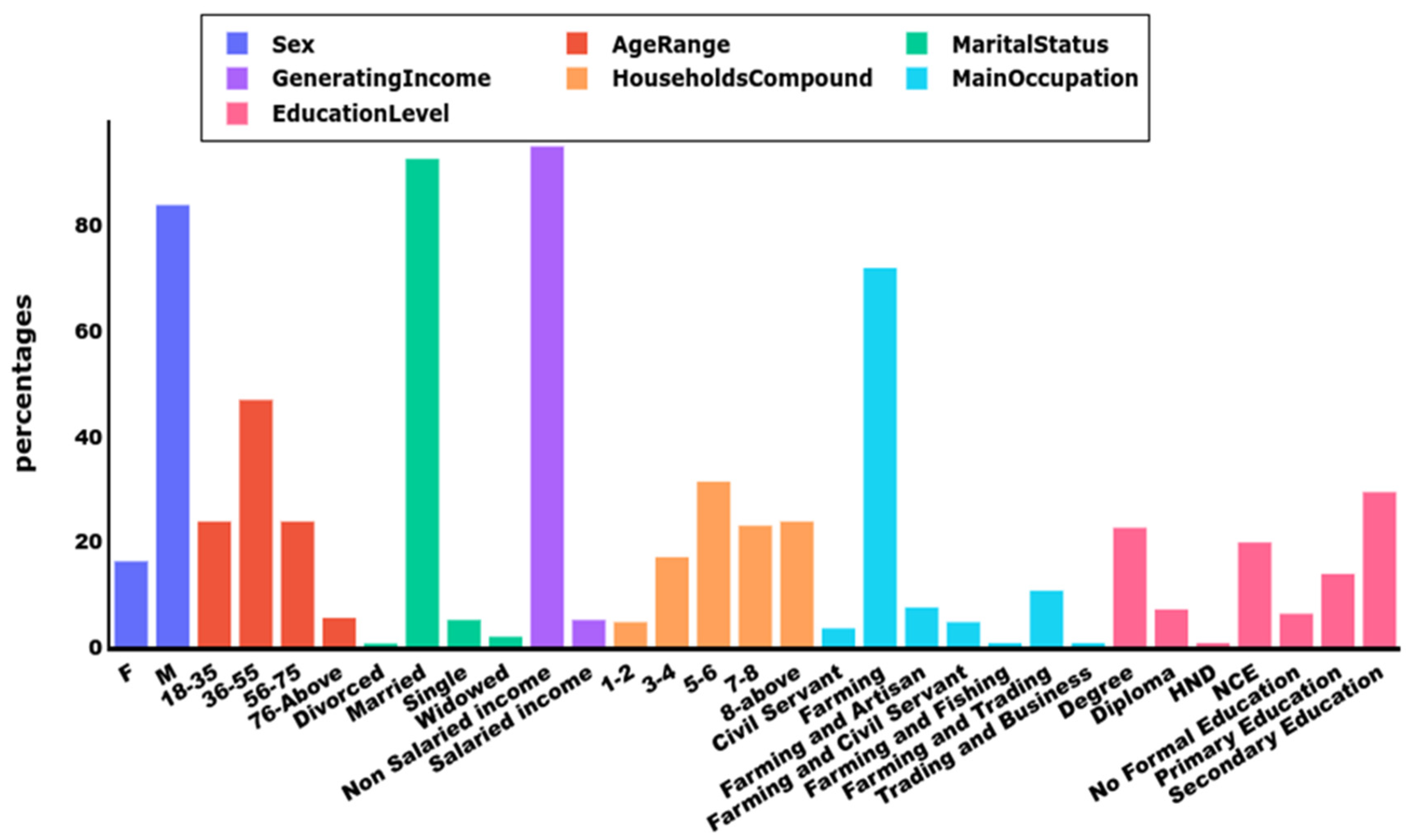

3.1. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Surveyed Respondents Across the Three Study Forests in Nasarawa State

3.2. Forest Change

3.3. Perceived Direct Drivers of Change

3.3.1. Lumbering

3.3.2. Agricultural Expansion

3.3.3. Charcoal and Firewood

3.3.4. Grazing

3.3.5. Construction and Settlement

3.4. Perceived Indirect Drivers of Change

3.4.1. Population Growth

3.4.2. Poverty

3.4.3. Poor Governance and Corruption

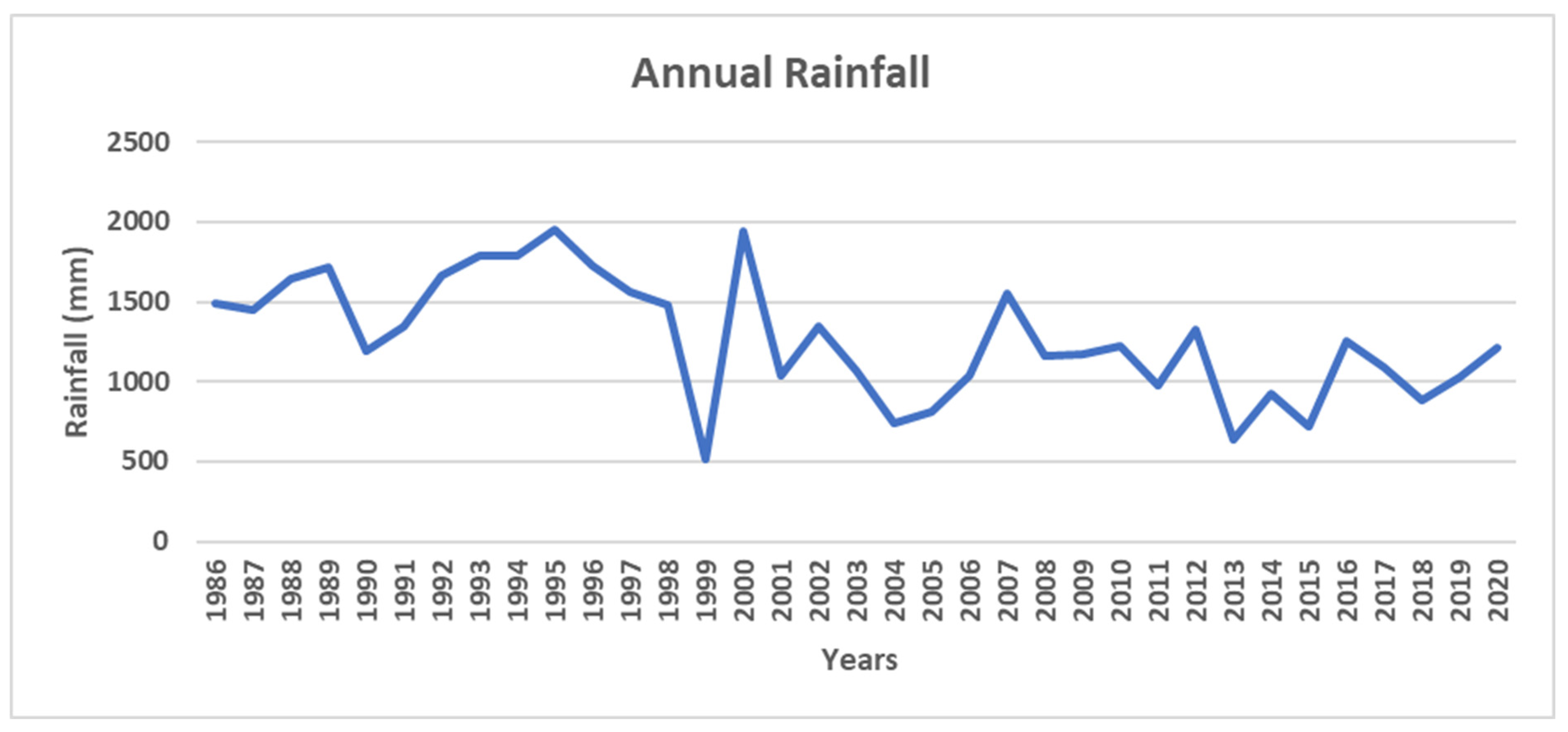

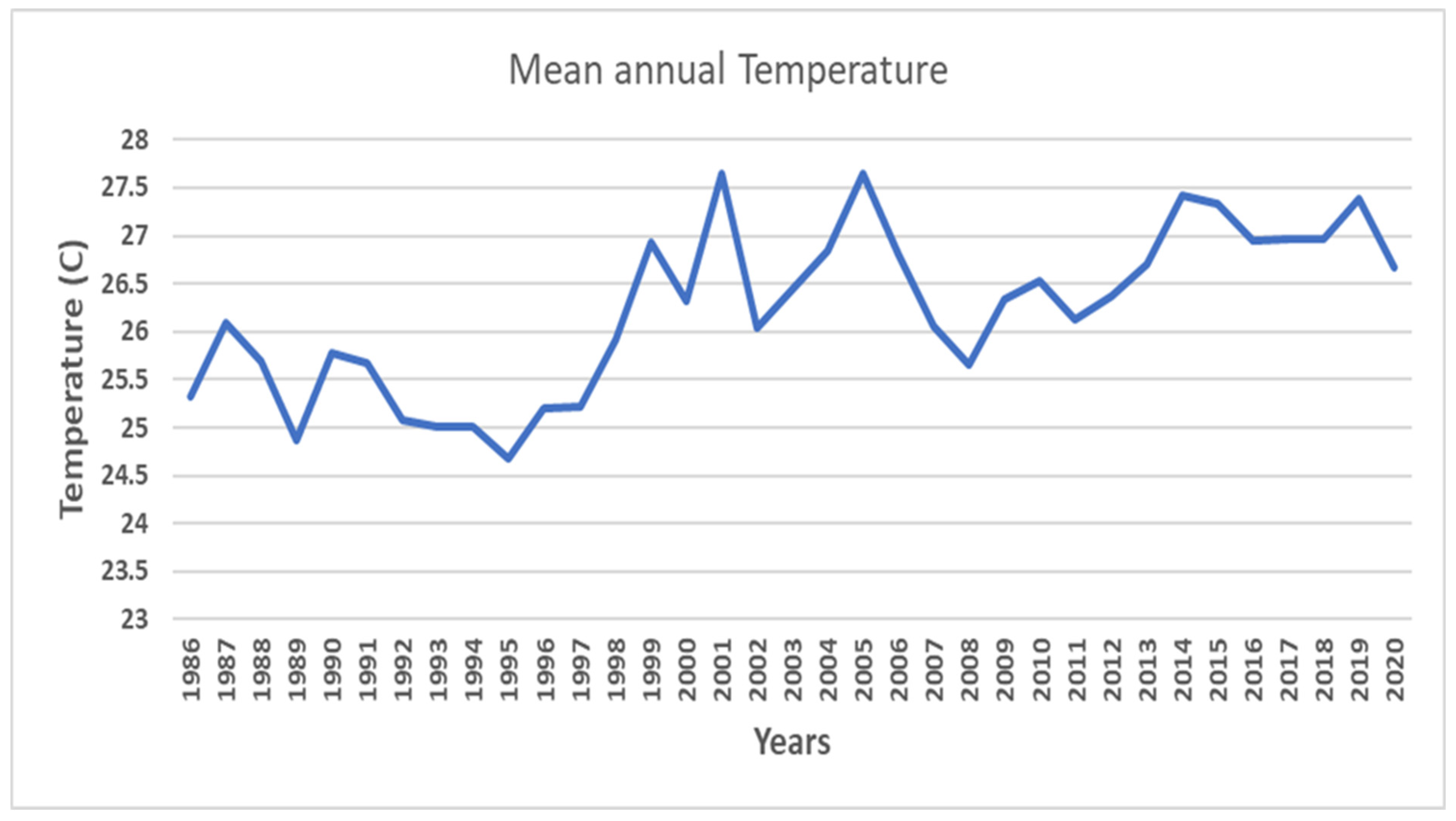

3.4.4. Climate Change

3.5. Unique Issues Within Each Forest Reserve

4. Discussion and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Participants’ Group | Key Response (s) Agriculture |

|---|---|

| Local People | “The forest reserve has undergone substantial changes primarily due to the expansion of agricultural activities, as it has become a site for farming. Local communities cultivate a variety of crops in the area, including yam, groundnut, melon, maize, guinea corn, beans, soya beans, and others. This agricultural activity has contributed to the transformation of the forest landscape, reflecting a shift in land use driven by local livelihoods and subsistence needs.” (Doma Local People KII 001, June 2022) |

| Local Leaders | “Agriculture is the major driver for the forest changes in this area because trees have been cut down to give space for farming activities since the 1960s until date; it is the source of livelihood for our communities, which is why we exploit these forest reserve resources and cultivate crops within the area. We, the community, have no alternative sources of income for our livelihoods. We depend on the forest reserve for our source of income and livelihood.” (Doma Local leaders KII 001, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) poverty | |

| Local people | “Poverty is a significant driver of changes in the forest reserve. People exploit this forest to sustain their livelihoods and meet economic needs, with community members often clearing parts of the forest to access and utilize its resources.” (KII Doma Local person 005, June 2022). |

| Key response (s) Lumbering | |

| Local people | “The practice of timber extraction has persisted for thousands of years, focusing on economically valuable tree species like Iroko, mahogany, ebeche, shea butter trees. These trees have been harvested to meet the substantial demand for timber exports, serving diverse applications abroad and within local communities. This industry includes forest-dwelling individuals and private commercial enterprises, generating revenue for governmental bodies. Consequently, these logging operations have significantly altered the designated forest reserve.” (Doma Local People KII 003, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Fuelwood/Charcoal | |

| Local Community Leaders | “Local communities frequently harvest trees, such as Vitellaria paradoxa (shea tree), Daniellia oliveri (African Copaiba balsam tree), and Prosopis africana, for firewood and high-quality charcoal due to their dense wood and high calorific value. This targeted harvesting has significantly contributed to the depletion of forest cover and resources in the reserve, driven by domestic use and economic necessities.” (Doma, local community leader K II 004, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Grazing | |

| Local people | “Grazing by herdsmen contributes to the destruction of the forest reserve; they move into the forestry area and cut down the trees and grasses to feed their animals’, this reduces the composition and size of the forest reserves.; Their activities affect forest growth and cover.” (Doma, Community members KII 003, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Population | |

| Local Community Leaders | “Population growth has significantly impacted forest cover and ecosystem change, interacting with other environmental pressures and direct drivers. For example, the demand for livelihood sources is influenced by population growth. Prior to 1960, the population that led to extraction and degradation remained low. However, since 2000, deforestation has escalated, largely driven by rapid population growth within the state and local community areas.” (Doma, local community leader KII 005, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Government policies/Governance | |

| Local people | “Before now, government do take good care of the reserves but now less attention is given, so people go into the reserves and cut down trees in the reserve any time without any taken proper permission.” (Doma local people KII 005, June 2022). |

| Key response (s) Settlement/Construction | |

| Local Leader | “Residential building is among other land uses that contribute to the change of the forest reserve because the first need of a man is shelter. Our people build within the forest reserve area before using the resources available on the reserves such as agriculture, timber and with the increasing of human population people clear forest area for more building.” (Doma local leader, 002, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Migration | |

| Local People | “People migrate from rural to rural areas for a greener pasture. For example, people migrate to our community in Doma, and we allow them to live with us, contributing to the pressure we receive on our forest cover and the forest resources for a livelihood. This help in contributing to the change in the forested area.” (Doma local person KII 002, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Corruption | |

| Local leaders | “The government forest officers assigned to monitor, manage, and enforce the forest laws against encroachments in this forest reserve encourage the community and even foreigners by collecting small bribes from them and then allowing them to enter the forest and degrade it for timber extraction, agricultural, and other uses, which leads to a high rate of cutting forest trees and a change in the forest reserves.” Doma local leader KII 003, June 2022) |

| Participants’ Group | Key Response (s) Agriculture |

|---|---|

| Local People | “Agriculture activities have been the primary driver of forest changes in this reserve. Since the 1970s, extensive tree cover has been cut down to give space for farming activities. These practices are deeply intertwined with the livelihoods of local communities, as agriculture serves as the primary source of income and sustenance for many families. The community’s reliance on forest resources is rooted in a lack of alternative economic opportunities, leading to the exploitation of the forest reserve for both agricultural cultivation and other livelihood needs.” (Risha Local people KII 001, June 2022). |

| Community Leaders | “The forest reserve has changed due to agriculture expansion because we are farming there. We farm crops like yam, groundnut, melon, maize, guinea corn, beans, and soya beans and so on.” (Risha Local leaders KII 001, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Lumbering | |

| Local people | “Lumbering is one of the key contributors to human activities that lead to the degradation of forest reserve in this area. People often felling or cut down trees in and around protected forest areas, particularly to obtain timber for construction materials such as roofing houses. Over time, this persistent practice not only depletes tree populations but also undermines efforts to maintain the ecological balance and biodiversity within this reserve.” (Risha, KII 004, June 2022) |

| “Valuable tree species, including mahogany, iroko, and others less commonly recognized, were heavily exploited by the community and the government for timber to meet housing, roofing, and construction demands. This large-scale deforestation significantly reduced forest cover, disrupting the ecological balance. The loss of these trees has had cascading effects on biodiversity, including wildlife displacement and depletion of other valuable species. As a result, these trees are now scarce around the reserve, highlighting the long-term consequences of unsustainable logging practices.” (Risha, KII 002, June 2022) | |

| Key response (s) Charcoal production | |

| Local leaders | “Most of our people “indigenes” cut down trees to produce charcoal and firewood; also, the trees provide us with construction materials which we construct our houses and also sell to generate income for ourselves and our families, and I think it could be a crucial driver for the gazetted forest reserve changes.” (Risha Community Leader KII 004, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Population growth | |

| Local People | “Due to population increase, people started claiming ownership of land for farming purposes around 1998 to date of the forest reserves area.” (Risha forest, Local person 003, (Female) KII July 2022) |

| Key response (s) Poverty | |

| Local people | “Poverty is one of the major drivers that led to changes in the forest reserves: we expand our agricultural land in the forest to get our livelihood since we have no good way of getting food or money to survive.” (KII Risha Local people 005, June 2022) |

| Local leaders | “We can say poverty serves as a key driver of changes in forest reserves, as economically disadvantaged communities often resort to clearing forests to meet immediate needs. This includes expanding agricultural land to grow crops for subsistence and income generation, as well as extracting resources from forests to support livelihoods. These activities are frequently undertaken to ensure economic survival in the face of limited alternatives.” (KII Risha Local leader 005, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Government policies/Governance | |

| Local people | “The government forest officers assigned to monitor, manage, and enforce the forest laws against encroachments in this forest reserve encourage the community and even foreigners by collecting small bribes from them and then allowing them to enter the forest and degrade it for timber extraction, agricultural, and other uses, which leads to a high rate of cutting forest trees and a change in the forest reserves.” (Risha local people KII 004, June 2022) |

| Participants’ Group | Key Response (s) Agriculture |

|---|---|

| Local People | “Agriculture has contributed to forest changes here since the 1970s, as we depend on farming and forest resources for income and survival, with no alternative livelihoods.” (Odu, Local Community members, KII 003, June 2022) |

| Community Leaders | “Agriculture is the major driver for the forest changes in this area because trees have been cut down to give space for farming activities since the 1960s until date; it is the source of livelihood for our communities, which is why we exploit these forest reserve resources and cultivate crops within the area. We, the community, have no alternative sources of income for our livelihoods. We depend on the forest reserve for our source of income and livelihood.” (Doma Local leaders KII 001, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Lumbering | |

| Local Community Members | “Trees like mahogany, iroko and so on I don’t know their names, were selected and massively cut out for timbers for houses, roofing and other constructions, affecting trees cover in the forest and even wild animals and other valuable trees, now hardly you seem them in the forest.” (Odu, Community members, KII 002, June 2022) |

| Local Community leaders | “There was an extensive exploitation of forest resources particularly trees such as mahogany, iroko, Parkia biglobosa, Gmelina, opepe and others whose names I cannot recall were selectively and extensively harvested for timber used in housing, roofing, and other construction purposes. This has significantly reduced tree cover in the forest, adversely affecting wildlife and other valuable tree species. Today, these trees are scarcely found in the forest.” (Odu, Local People, KII 002, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Fuelwood/Charcoal | |

| Local Community Members | “Some of our people cut down trees for firewood and charcoal, targeting specific trees, which has depleted forest covers and resources from this reserve. For instance, tree species such as Vitellaria paradoxa (commonly known as shea tree), Daniellia oliveri (African Copaiba balsam tree), and Prosopis africana are frequently harvested for high-quality charcoal due to their dense wood and high calorific value. The widespread cutting and burning of these trees for charcoal for domestic use and economic gain.” (Odu, Local Community members K II 005, June 2022) |

| Community leaders | “Our people cut and burn some of the tree species for charcoal; there are specific trees that we have for producing charcoal, and this may have contributed to the reduction of the forest.” (Odu, Community leader K II 003, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Grazing | |

| Local people | “Animals have been grazing around the reserve by Fulani [Herdsmen] over the parcel of land within the forest reserve area. The cattle and cows’ footsteps are overstepping the forest by feeding on the grass within the reserve area and cutting down branches of trees for their animals to feed on, and at times they even cut down the trunks for grazing purposes. Again, they cut down the trees to build their camps (houses), and now they are even going to the roots to uproot the trees.” (Odu, Local people KII 001, June 2022) |

| Local leaders |

| Participants’ Group | Key Response (s) Agriculture |

|---|---|

| Government officials | “Farmlands are expanded in the reserve areas, and even the government has allowed Tungiya farming in the reserve, which was supposed to be protected. As such, most people begin to farm again around the area. Before the farm, they clear trees by cutting off trees’ vegetation cover and even burning them, which degrades the forest cover and also destroys soil organisms on the forest lands, which affects the growth of the forest trees in this forest reserves area.” (Government official KII 003,) June 2022) |

| Experts | |

| Key response (s) Lumbering | |

| Government official | “As forest communities population increases, people are erecting structures, they fell trees to produce timber to roof their houses, so this has contributed to the decline of the forest reserve in this area.” (Government official, KII 002, June 2022) |

| Experts | “Logging activities have been there for thousands of years now, targeting some particular economic trees. They have been cut down due to high demand for these timbers’ export for different uses and for the communities’ uses. This activity involves both the individual in the forest communities and the private commercial that generate revenue for the government, which has a significant impact on the gazetted forest change in these areas.” (Expert KII 001, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Poverty | |

| Government official | “The one major activity for the forest reserve change is just poverty and that is the fact, the community members need money for livelihoods and economic means which result to clear forest around them for the resources uses.” (KII Government official 005, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Population growth | |

| Experts | “Population around this forest reserve areas has changed from 1959 till today in the forest communities. For example, the increased expansion and urbanization comes in; as a result, some of the villages that are used to be 300 square meters now will be 3000 square meters, also likely 500 people then, but today the population of the same place may be like 3500 persons, so as such, with human population increases, settlements growth is bound to occur, and settlements growth means encroaching into other land uses that were not residential, because the first need of a man is shelter, and in a shelter and then production which is within the forest reserve to extract raw material for the production of housing, timbers and leading to other activities as increasing human population results to increasing demand from people for other land use and human activities for livelihood which is the key driving forces of the forest change.” (Expert KII 004, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Government policies/Governance | |

| Government Official | “Government policies are often contributing to deforestation in forest reserves. This is because these policies are not always implemented in a manner that aligns with the needs of the people for conservation. For instance, Nigeria’s high cost of natural gas, cooking gas, and kerosene has led to a situation where poor residents in forest communities are forced to resort to forests for their energy needs. This has resulted in the degradation of the ecosystem and a change in the forest cover.” (Government official KII 002, June 2022) |

| Key response (s) Settlement/Construction | |

| Government official | “Road construction and housing development, particularly around forest reserves like Doma and Risha, has increased due to growing socio-economic activities requiring infrastructure. This has led to significant degradation of these reserves through logging and timber use, causing extensive deforestation and heavily degrading parts of the forest for settlement and infrastructure development.” (KII Government official 005, June 2022) |

| Expert | “Recently, road construction in Nasarawa State has tended to increase around some forest reserves linked to socio-economic activities that lead to the demand of facilities such as stores, houses, and built-up products to help with socio-economy activities. This utilization of wood logs and timbers for construction affects our forest reserves. For Example, Doma road opens to Yalwa, which passes through the forest reserves, and massive destruction of forest for the road construction was done. This has greatly affected some portion of the forest in this area.” (Expert KII 002, June 2022). |

| Key response (s) Insecurity thread | |

| Expert | “Some of these forests are the hiding place for criminals in the hiding zone. These people cut down vegetation cover around their communities to see their surroundings clearly for defence purposes.” (Expert KII 001 June 2022) |

References

- Makunga, J.E.; Misana, S.B. The Extent and Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Masito-Ugalla Ecosystem, Kigoma Region, Tanzania. Open J. For. 2017, 7, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibaba, W.T.; Demissie, T.A.; Miegel, K. Drivers and implications of land use/land cover dynamics in Finchaa Catchment, Northwestern Ethiopia. Land 2020, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyam, M.M.H.; Haque, M.R.; Rahman, M.M. Identifying the land use land cover (LULC) changes using remote sensing and GIS approach: A case study at Bhaluka in Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 7, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Hu, F.; Ma, W.; Yang, W.; Luan, X. Drivers and Dynamics of Forest and Grassland Ecosystems in the Altai Mountains: A Framework for National Park Conservation. Land 2024, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro Appiah, J.; Agyemang-Duah, W.; Sobeng, A.K.; Kpienbaareh, D. Analysing patterns of forest cover change and related land uses in the Tano-Offin forest reserve in Ghana: Implications for forest policy and land management. Trees For. People 2021, 5, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eludoyin, A.O.; Iyanda, O.O. Land cover change and forest management strategies in Ife nature reserve, Nigeria. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 1531–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiaco, L.; Corongiu, M. Analysis of LULC Change Dynamics That Have Occurred in Tuscany (Italy) Since 2007. Land 2025, 14, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, M.; Nyirenda, H. Assessment of land use change in the Thuma forest reserve region of Malawi, Africa. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthali, M.G.; Kindu, M.; Adeola, A.M.; Davis, N.; Botai, J.O.; Solomon, N. Variations of ecosystem service values as a response to land use and land cover dynamics in central Malawi. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 25, 9821–9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, A.; Korle, K.; Kwablah, E.; Asiama, R.K. Sustaining Protected Forests and Forest Resources in Ghana: An Empirical Evidence. J. Sustain. For. 2022, 42, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, R.J.; Reams, G.A.; Achard, F.; de Freitas, J.V.; Grainger, A.; Lindquist, E. Dynamics of global forest area: Results from the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 352, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, R.; Stacey, N.; Eddy, I.M.S.; Tomscha, S.A.; Sunderland, T.C.H. Recent trends of forest cover change and ecosystem services in the eastern upland region of Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diep, N.T.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Diem, P.K.; Nguyen, C.T. Benefits and Trade-Offs from Land Use and Land Cover Changes Under Different Scenarios in the Coastal Delta of Vietnam. Land 2025, 14, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; Abram, N.K.; Wells, J.A.; Pellier, A.S.; Ancrenaz, M.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Runting, R.K.; Mengersen, K. People’s Perceptions about the Importance of Forests on Borneo. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; Liu, W. Disentangling the complexity of regional ecosystem degradation: Uncovering the interconnected natural-social drivers of quantity and quality loss. Land 2023, 12, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutouama, F.T.; Biaou, S.S.H.; Kyereh, B.; Asante, W.A.; Natta, A.K. Factors shaping local people’s perception of ecosystem services in the Atacora Chain of Mountains, a biodiversity hotspot in northern Benin. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, D.; Benedikter, S.; Giessen, L. Rethinking Synergies and Trade-Offs at the Forest-Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Nexus A Systematic Review. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitani, C.; Van Soesbergen, A.; Mukama, K.; Malugu, I.; Mbilinyi, B.; Chamuya, N.; Kempen, B.; Malimbwi, R.; Mant, R.; Munishi, P. Scenarios of Land Use and Land Cover Change and Their Multiple Impacts on Natural Capital in Tanzania. Environ. Conserv. 2019, 46, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirov, M.; Pokorny, B.; Kleinschmit, D.; Kanowski, P. International forest governance and policy: Institutional architecture and pathways of influence in global sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scullion, J.J.; Vogt, K.A.; Drahota, B.; Winkler-Schor, S.; Lyons, M. Conserving the Last Great Forests: A Meta-Analysis Review of the Drivers of Intact Forest Loss and the Strategies and Policies to Save Them. Front. For. Glob. Change 2019, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment, M.E. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Wetlands and Water; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Dietz, T.; Kramer, D.B.; Ouyang, Z.; Liu, J. An integrated approach to understanding the linkages between ecosystem services and human well-being. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2015, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.; Peponis, J. Poverty and connectivity. J. Space Syntax 2010, 1, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cantarello, E.; Lovegrove, A.; Orozumbekov, A.; Birch, J.; Brouwers, N.; Newton, A.C. Human impacts on forest biodiversity in protected walnut-fruit forests in Kyrgyzstan. J. Sustain. For. 2014, 33, 454–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, E.K.K.; Burdekin, O.J.; Dougill, A.J.; Sallu, S.M. Rapid land use change threatens the provisioning of ecosystem services in Miombo woodlands. Nat. Resour. Forum 2019, 43, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasona, M.J.; Akintuyi, A.O.; Adeonipekun, P.A.; Akoso, T.M.; Udofia, S.K.; Agboola, O.O.; Ogunsanwo, G.E.; Ariori, A.N.; Omojola, A.S.; Soneye, A.S.; et al. Recent trends in land-use and cover change and deforestation in south–west Nigeria. GeoJournal 2020, 87, 1411–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.L.; Prescott, G.W.; De Alban, J.D.T.; Ziegler, A.D.; Webb, E.L. Untangling the proximate causes and underlying drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Myanmar. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 31, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, A.; Roque, F.d.O.; Garcia, L.C.; Ochao-Quintero, J.M.O.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Guariento, R.D.; Rosa, I.M.D. Drivers and projections of vegetation loss in the Pantanal and surrounding ecosystems. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunwate, B.T.; Yahaya, S.; Samaila, I.K.; Ja’afaru, S.W. Analysis of Urban Land Use and Land Cover Change for Sustainable Development: A Case of Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2019, 11, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheynaldi, P.K.; Endri, E.; Minanari, M.; Ferranti, P.A.; Karyatun, S. Energy price and stock return: Evidence of energy sector companies in Indonesia. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2023, 13, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehkamp, J.; Aquino, A.; Fuss, S.; Reed, E.W. Analyzing the perception of deforestation drivers by African policy makers in light of possible REDD+ policy responses. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 59, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, H.J.; Lambin, E.F. Proximate Causes and Underlying Driving Forces of Tropical Deforestation Tropical forests are disappearing as the result of many pressures, both local and regional, acting in various combinations in different geographical locations. Bio Sci. 2020, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hosonuma, N.; Herold, M.; De Sy, V.; De Fries, R.S.; Brockhaus, M.; Verchot, L.; Angelsen, A.; Romijn, E. An assessment of deforestation and forest degradation drivers in developing countries. Environ. Res. Let. 2012, 7, 044009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirwa, P.W.; Mahamane, L.; Kowero, G. Forests, people, and environment: Some African perspectives. South. For. 2017, 79, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worboys, G.L.; Lockwood, M.; Kothari, A.; Feary, S.; Pulsford, I. Protected Area Governance and Management; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 207–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Terms and Definitions (FRA 2020); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/I8661EN/i8661en.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Moussa, S. Impact of Land Use and Climate Change on Vegetation Dynamics of Doma Forest Reserve in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, WASCAL, Accra, Ghana, September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fasona, M.; Adedoyin, B.; Sobanke, I. Status and Drivers of spatial change of forest reserves and protected areas in the Selected State of Southwest Nigeria: A case study of Ogun, Osun and Oyo state Nigeria. Osun Geogr. Rev. 2020, 3, 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Olorunfemi, I.E.; Fasinmirin, J.T.; Olufayo, A.A.; Komolafe, A.A. GIS and remote sensing-based analysis of the impacts of land use/land cover change (LULCC) on the environmental sustainability of Ekiti State, southwestern Nigeria. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 661–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geidam, K.K.; Adnan, N.A.; Alhaji Umar, B. Analysis of Land Use Land Cover Changes Using Remote Sensing Data and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) at an Urban Set up of Damaturu, Nigeria. J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 12, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, O.H.; Tope-Ajayi, O.O.; Abegunde, O.L. Assessing and Predicting Changes in the Status of Gambari Forest Reserve, Nigeria Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2015, 7, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Chen, B.; Hu, T.; Liu, X.; Xu, B.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. Annual maps of global artificial impervious area (GAIA) between 1985 and 2018. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thasi, K.; Martin, T.; Gueguim, D. Spatial and temporal dynamics of anthropogenic threats on the biodiversity of Virunga National Park. Int. J. For. Anim. Fish. Res. 2021, 5, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Department of Forestry—Federal Ministry of Environment. National Forest Reference Emission Level (FREL) for the Federal Republic of Nigeria; FDF–FME: Abuja, Nigeria, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Inuwa, N.; Adamu, S.; Sani, M.B.; Modibbo, H.U. Natural resource and economic growth nexus in Nigeria: A disaggregated approach. Lett. Spat. Resour. Sci. 2022, 15, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atim, G.; Gbamwuan, A. Farmer-Herder Conflicts and the Socio-Economic Predicaments of Women in North Central Nigeria. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2022, 9, 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Chunwate, B.T.; Yerima, S.Y.S.; Samuel, A. Analysis of land-use conflict between farmers and pastoralists in Gwagwalada Area Council of Abuja, Nigeria. Glob. J. Sci. Front. Res. H Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 21, 49–55. Available online: https://journalofscience.org/index.php/GJSFR/article/view/2952 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Madu, I.A.; Nwankwo, C.F. Spatial pattern of climate change and farmer–herder conflict vulnerabilities in Nigeria. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 2691–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogu, M.I. Resurgent violent farmer-herder conflicts and ‘nightmares’ in Northern Nigeria. NILDS J. Democr. Stud. 2020, 1, 109–131. Available online: https://ir.nilds.gov.ng/handle/123456789/179 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Okoli, A.C.; Atelhe, G.A. Nomads against natives: A political ecology of herder/farmer conflicts in Nasarawa state, Nigeria. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2014, 4, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ihemezie, E.J.; Dallimer, M. Stakeholders’ perceptions on agricultural land-use change, and associated factors, in Nigeria. Environments 2021, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agidi, V.; Hassan, S.; Baleri, T.; Yilgak, J. Effect of Inter-annual Rainfall Variability on Precipitation Effectiveness in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2018, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benue Plateau State Government. Forest Law; Gazetted No. 8; Unpublished Government Document; Forestry Department Archive: Makurdi, Nigeria, 1972; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ahungwa, G.T.; Umeh, J.C.; Muktar, B.G. Empirical analysis of food security status of farming households in Benue state, Nigeria. OSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2013, 6, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fabolude, G.O.; David, O.A.; Akanmu, A.O.; Nakalembe, C.; Komolafe, R.J.; Akomolafe, G.F. Impacts of anthropogenic disturbance on forest vegetation cover, health, and diversity within Doma forest reserve, Nigeria. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buba, T. Impact of Different Types of Land Use on Pattern of Herbaceous Plant Community in the Nigerian Northern Guinea Savanna. J. Agric. Ecol. Res. Int. 2015, 4, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcourt, N.; Walters, J.; Carlson, S.; Safford, K.; Hansen, L.; Russell, D.; Tabaj, K.; Kroner, R.G. Mapping drivers of land conversion among smallholders: A global systems perspective. Agric. Agric. Syst. 2024, 218, 103986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidu, S.; Yahaya, T.I. Spatio-temporal Variations in Mean Heavy Rainfall Days over the Guinea Savanna Ecological Zone of Nigeria. Sahel J. Geogr. Environ. Dev. 2020, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulaziz, H.; Johar, F.; Majid, M.R.; Medugu, N.I. Protected area management in Nigeria: A review. J. Teknol. (Sci. Eng.) 2015, 77, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ganesha, H.R.; Aithal, P.S. How to Choose an Appropriate Research Data Collection Method and Method Choice Among Various Research Data Collection Methods and Method Choices During Ph.D. Program in India? Int. J. Manag. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2022, 7, 455–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, K.; Shakya, B.; Adhikari, B.; Nepal, M.; Yi, S. Ecosystem services valuation for conservation and development decisions: A review of valuation studies and tools in the Far Eastern Himalaya. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 61, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xiao, Y.; Van Koppen, C.S.A.; Ouyang, Z. Local perceptions of ecosystem services and protection of culturally protected forests in southeast China. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2018, 4, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhati, G.L.; Olago, D.; Olaka, L. Land use and land cover changes in a sub-humid Montane Forest in an arid setting: A case study of the Marsabit forest reserve in northern Kenya. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, e00512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. “With constructivist grounded theory you can’t hide”: Social justice research and critical inquiry in the public sphere. Qual. Inq. 2020, 26, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammides, C.; Ma, J.; Bertzky, B.; Langner, A. Global Patterns and Drivers of Forest Loss and Degradation Within Protected Areas. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 907537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahuri, S.; Fikri, S.; Fikri, D.; Armi, I. An Identification of Deforestation in Protected Forest Areas Using Land Cover mapping (A Case Study of Bukit Suligi Protected Forest). South East Asian J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 2023, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kayombo, C.J.; Ndangalasi, H.J.; Mligo, C.; Giliba, R.A. Analysis of Land Cover Changes in Afromontane Vegetation of Image Forest Reserve, Southern Highlands of Tanzania. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 7402846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, E.; Pagella, T.; Mollee, E.; van Noordwijk, M. Relational values in locally adaptive farmer-to-farmer extension: How important? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 65, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, R.; Yadav, R.; Gupta, H.; Vasure, N.; Choudhary, S.; Singh, M.N.; Rastogi, M. The role of agroforestry systems in enhancing climate resilience and sustainability—A review. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 4342–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankomah, F.; Kyereh, B.; Ansong, M.; Asante, W. Forest management regimes and drivers of forest cover loss in forest reserves in the high forest zone of Ghana. Int. J. For. Res. 2020, 2020, 8865936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimutai, D.K.; Watanabe, T. Forest-cover change and participatory forest management of the lembus forest, Kenya. Environments 2016, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimoogunje, O.O. Forest cover changes and land use dynamics in Oluwa forest reserve, Southwestern Nigeria. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 7, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeminiwa, O.R.; Jeminiwa, M.S.; Taiwo, D.M.; Dauda, M.; Olaotilaaro, S.O. Assessment of Forest Degradation Indices in Mokwa Forest Reserve, Niger State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2020, 24, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedano, F.; Silva, J.A.; Machoco, R.; Meque, C.H.; Sitoe, A.; Ribeiro, N.; Anderson, K.; Ombe, Z.A.; Baule, S.H.; Tucker, C.J. The impact of charcoal production on forest degradation: A case study in Tete, Mozambique. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpo, A.S.; Mba, E.H. Assessment of Commercial Charcoal Production Effect on Savannah Woodland of Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2020, 24, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, J.; Ofosu, A.; Iddrisu, S.; Kofi Garsonu, E. Wood fuel producers’ insight on the environmental effects of their activities in Ghana. J. Sustain. For. 2023, 42, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, M.P.; Bhatta, K.P.; Ghimire, S. Charcoal production as a means of forest management, biodiversity conservation and livelihood support in Nepal. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2017, 7, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, L.; Houet, T.; Verburg, P.H. Mapping biodiversity and ecosystem service trade-offs and synergies of agricultural change trajectories in Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, A.T.; Barau, A.S.; Carr, J.A.; Chunwate, B.T.; Jew, E.K.K.; Kirshner, J.D.; Marchant, R.A.; Tomei, J.; Stringer, L.C. The forgotten bread oven: Local bakeries, forests and energy transition in Nigeria. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Bunting, P.; Hardy, A.; Roberts, O.; Giliba, R.; Silayo, D.S. Modelling the impact of climate change on Tanzanian forests. Divers. Distrib. 2020, 26, 1663–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Socorro, L.F. Guardians of the green: An essay on the impacts of climate change on forest ecosystems and its mitigation. Davao Res. J. 2023, 14, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, R.W.; Western, D.; Willcock, S.; Marchant, R. Assessing interactions between agriculture, livestock grazing and wildlife conservation land uses: A historical example from east Africa. Land 2021, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoneli, V.; Thomaz, E.L.; Bednarz, J.A. The Faxinal System: Forest fragmentation and soil degradation on the communal grazing land. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2019, 40, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shang, X.; Fan, F.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Sun, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. Impacts of livestock grazing on blue-eared pheasants (Crossoptilon auritum) survival in subalpine forests of Southwest China. Integr. Conserv. 2023, 2, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, K.; Richardson, K.; MacKinnon, J. Protected and other conserved areas: Ensuring the future of forest biodiversity in a changing climate. Int. For. Rev. 2020, 22, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, E. The Spatiotemporal Change in Land Cover and Discrepancies within Different Countries on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau over a Recent 30-Year Period. Land 2023, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlhodi, B.; Kenabatho, P.K.; Parida, B.P.; Maphanyane, J.G. Evaluating land use and land cover change in the Gaborone dam catchment, Botswana, from 1984–2015 using GIS and remote sensing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucova, S.A.R.; Leal Filho, W.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Pereira, M.J. Assessment of land use and land cover changes from 1979 to 2017 and biodiversity & land management approach in Quirimbas National Park, Northern Mozambique, Africa. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, e00447. [Google Scholar]

- Jellason, N.P.; Robinson, E.J.Z.; Chapman, A.S.A.; Neina, D.; Devenish, A.J.M.; Po, J.Y.T.; Adolph, B. A systematic review of drivers and constraints on agricultural expansion in sub-Saharan Africa. Land 2021, 10, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojiija, F.; Swai, E.; Mwakalapa, E.B.; Mbije, N.E.J. Impacts of emerging infrastructure development on wildlife species and habitats in Tanzania. J. Wildl. Biodivers. 2024, 8, 365–384. [Google Scholar]

- Alamgir, M.; Campbell, M.J.; Sloan, S.; Suhardiman, A.; Supriatna, J.; Laurance, W.F. High-risk infrastructure projects pose imminent threats to forests in Indonesian Borneo. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojija, F.; Nicholaus, R. Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources and its Implications on Biodiversity: A Review. East Afr. J. Environ. Nat. Resour. 2023, 6, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Riechers, M.; Loos, J.; Martin-Lopez, B.; Temperton, V.M. Making the UN decade on ecosystem restoration a social-ecological endeavour. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppa, L.N.; Pfaff, A. Global protected area impacts. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 278, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.P.; Klooster, D.J. Migration and a New Landscape of Forest Use and Conservation. Environ. Conserv. 2019, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan-Hallam, M.; Bennett, N.J. Adaptive social impact management for conservation and environmental management. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Stringer, L.; Holmes, G. Changing governance, changing inequalities: Protected area co-management and access to forest ecosystem services: A Madagascar case study. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 30, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, L.; Luoma, C. Decolonising conservation policy: How colonial land and conservation ideologies persist and perpetuate indigenous injustices at the expense of the environment. Land 2020, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertzky, B.; Corrigan, C.; Kemsey, J.; Kenney, S.; Ravilious, C.; Besançon, C.; Burgess, N. Protected Planet Report 2012: Tracking progress towards global targets for protected areas. IUCN and UNEP-WCMC. 2012. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/system/comfy/cms/files/files/000/000/220/original/Protected_Planet_Report_2012.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Duguma, L.A.; Atela, J.; Ayana, A.N.; Alemagi, D.; Mpanda, M.; Nyago, M.; Minang, P.A.; Nzyoka, J.M.; Foundjem-Tita, D.; Ntamag-Ndjebet, C.N. Community forestry frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa and the impact on sustainable development. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, O.E.; Akinsorotan, O.A.; Zakaria, M.; Martins, C.O.; Adebola, S.I.; Oyelowo, O.J. Taking the edge off host communities’ dependence on protected areas in Nigeria. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 269, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plata-Rocha, W.; Monjardin-Armenta, S.A.; Pacheco-Angulo, C.E.; Rangel-Peraza, J.G.; Franco-Ochoa, C.; Mora-Felix, Z.D. Proximate and underlying deforestation causes in a tropical basin through specialized consultation and spatial logistic regression modeling. Land 2021, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, J.S.; Butsic, V.; Schwab, B.; Kuemmerle, T.; Radeloff, V.C. The relative effectiveness of protected areas, a logging ban, and sacred areas for old-growth forest protection in southwest China. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 181, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthali, M.G.; Davis, N.; Adeola, A.M.; Botai, J.O.; Kamwi, J.M.; Chisale, H.L.W.; Orimoogunje, O.O.I. Local perception of drivers of Land-Use and Land- Cover change dynamics across Dedza district, Central Malawi region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerfa, L.; Rhemtulla, J.M.; Zerriffi, H. Forest dependence is more than forest income: Development of a new index of forest product collection and livelihood resources. World Dev. 2020, 125, 104689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Hidalgo, D.; Oswalt, S.N.; Somanathan, E. Status and trends in global primary forest, protected areas, and areas designated for conservation of biodiversity from the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 352, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladan, S.I. Forests and Forest Reserves as Security Threats in Northern Nigeria. Eur. Sci. J. 2014, 10, 120–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lunstrum, E.; Ybarra, M. Deploying difference: Security threat narratives and state displacement from protected areas. Conserv. Soc. 2018, 16, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isyaku, U. What motivates communities to participate in forest conservation? A study of REDD+ pilot sites in Cross River, Nigeria. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 133, 102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, L.S.; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.L.; Giannini, T.C. Climate change impact on ecosystem functions provided by birds in southeastern Amazonia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, K.; Dudley, N.; Sandwith, T. Natural solutions: Protected areas helping people to cope with climate change. Oryx 2011, 45, 461–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranius, T.; Widenfalk, L.A.; Seedre, M.; Lindman, L.; Felton, A.; Hämäläinen, A.; Filyushkina, A.; Öckinger, E. Protected area designation and management in a world of climate change: A review of recommendations. Ambio 2023, 52, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senganimalunje, T.C.; Chirwa, P.W.; Babalola, F.D.; Graham, M.A. Does participatory forest management program lead to efficient forest resource use and improved rural livelihoods? Experiences from Mua-Livulezi Forest Reserve, Malawi. Agrofor. Syst. 2016, 90, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, R.P. Impact on Forest and vegetation due to human interventions. In Vegetation Dynamics, Changing Ecosystems and Human Responsibility; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indarto, J.; Mutaqin, D.J. An overview of theoretical and empirical studies on deforestation. J. Int. Dev. Coop. 2016, 22, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner-McAllister, S.L.; Rhodes, J.; Hockings, M. Managing for climate change on protected areas: An adaptive management decision making framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 204, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areo, O.S.; Omole, A.O.; Ayodeji, A.F.; Adewale, A.; Lukeman, O.G.F. Modern forest operation techniques in Nigeria: Challenges and solutions. Aust. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 7, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Scheren, P.; Tyrrell, P.; Brehony, P.; Allan, J.R.; Thorn, J.; Chinho, T.; Katerere, Y.; Ushie, V.; Worden, J.S.; Oliveira Cruz, C.; et al. Defining Pathways towards African Ecological Futures. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, G.; Teketay, D.; Fetene, M.; Beck, E. Regeneration of seven indigenous tree species in a dry Afromontane forest, southern Ethiopia. Flora-Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2010, 205, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veach, V.; Moilanen, A.; Di Minin, E. Threats from urban expansion, agricultural transformation and forest loss on global conservation priority areas. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Type of Respondent | Sample Size and Number of Participants | Sampling Approach | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | Four Groups’ Stakeholders | Local leaders Local people Policymakers Experts Total | 15 15 5 5 40 | Snowball sampling method |

| FGDs | Four Group Stakeholders | Local leaders Local people Policymakers Experts Total | 15 15 5 5 40 | Snowball sampling method |

| Household Questionnaire | Three Communities Local to the Selected Forest Reserves | Doma Forest Reserve Risha Forest Reserve Odu Forest Reserve Total | 84 84 84 252 | Multi-stage sample method |

| Stakeholder Groups | Description of the Stakeholder Group |

|---|---|

| Local people | These are the forest users in the communities; they interact frequently with the forest for resources to derive immediate benefits for their livelihoods within their forest communities, and include farmers, hunters, charcoal producers, and timber contractors. |

| Local leaders | These stakeholders are responsible for protecting their local environment through management of forest use, land ownership and disputes, and local regulations. This group includes Traditional Rulers, Village Heads, Youth Leaders, Women Leaders, and Market Leaders. |

| Government officials | These are government custodians who monitor and analyze forest uses, generate funds for the government, maintain forest-designated areas, record forest activities, and take legal action against forest law violations. The participants from this group were from the Nasarawa State Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources. |

| Experts | These are independent experts who advocate for forest and land use for sustainability and advise the government and the people to understand forest policy implementation strategies, considering their impact on the environment, and particularly the importance and role of forests in environmental sustainability. This group includes land-use planners, environmentalists, geographers, and foresters in academic and forestry institutions. |

| Forest Reserve | 1960–2000 | 2001–2022 | Key Drivers of Change | Processes of Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doma | Dense, biodiverse forests with tall trees and abundant wildlife. Minimal degradation. | Significant deforestation, biodiversity loss, and near disappearance of reserves. | Population growth, agricultural expansion, logging, charcoal production, bushfires, overgrazing, weak policy enforcement. | Loss of vegetation cover, economic exploitation, lack of reforestation, habitat destruction, invasive species, and inadequate enforcement. |

| Risha | Rich vegetation, wildlife, and water bodies with strong government control. | Near-total forest-cover loss, ecosystem disruption, species extinction, water body depletion. | Agricultural expansion, timber/charcoal extraction, firewood harvesting, and overgrazing. | Land clearing, hunting, changing cultural attitudes towards conservation, and economic pressures. |

| Odu | Intact forests with strong traditional laws limiting exploitation. | Accelerated degradation, habitat loss, soil erosion, reduced resilience. | Logging, agricultural expansion, urbanization, timber extraction, overgrazing, weak governance, and climate change. | Shift from traditional conservation to unsustainable exploitation, changing cultural attitudes towards conservation, population pressure, and economic reliance on forest resources. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chunwate, B.T.; Marchant, R.A.; Jew, E.K.K.; Stringer, L.C. Understanding Local Perspectives on the Trajectory and Drivers of Gazetted Forest Reserve Change in Nasarawa State, North Central Nigeria. Land 2025, 14, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071450

Chunwate BT, Marchant RA, Jew EKK, Stringer LC. Understanding Local Perspectives on the Trajectory and Drivers of Gazetted Forest Reserve Change in Nasarawa State, North Central Nigeria. Land. 2025; 14(7):1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071450

Chicago/Turabian StyleChunwate, Banki T., Robert A. Marchant, Eleanor K. K. Jew, and Lindsay C. Stringer. 2025. "Understanding Local Perspectives on the Trajectory and Drivers of Gazetted Forest Reserve Change in Nasarawa State, North Central Nigeria" Land 14, no. 7: 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071450

APA StyleChunwate, B. T., Marchant, R. A., Jew, E. K. K., & Stringer, L. C. (2025). Understanding Local Perspectives on the Trajectory and Drivers of Gazetted Forest Reserve Change in Nasarawa State, North Central Nigeria. Land, 14(7), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071450