Abstract

Lifestyle blocks (LBs) are small rural holdings primarily used for residential and recreational purposes rather than commercial farming. Despite the rapid expansion of LBs over the last 25 years, which has been driven by lifestyle amenity preference and land subdivision incentives, their environmental performance remains understudied. This is the case even though their proliferation is leading to an irreversible loss of highly productive soils and accelerating land fragmentation in peri-urban areas. Through undertaking a systematic literature review of relevant studies on LBs in New Zealand and comparable international contexts, this paper aims to quantify existing knowledge and suggest future research needs and management strategies. It focuses on the environmental implications of LB activities in relation to water consumption, food production, energy use, and biodiversity protection. The results indicate that variation in land use practices and environmental awareness among LB owners leads to differing environmental outcomes. LBs offer opportunities for biodiversity conservation and small-scale food production through sustainable practices, while also presenting environmental challenges related to resource consumption, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and loss of productive land for commercial agriculture. Targeted landscape design could help mitigate the environmental pressures associated with these properties while enhancing their potential to deliver ecological and sustainability benefits. The review highlights the need for further evaluation of the environmental sustainability of LBs and emphasises the importance of property design and adaptable planning policies and strategies that balance environmental sustainability, land productivity, and lifestyle owners’ aspirations. It underscores the potential for LBs to contribute positively to environmental management while addressing associated challenges, providing valuable insights for ecological conservation and sustainable land use planning.

1. Introduction

1.1. Peri-Urban Pressure and the Rise of Lifestyle Blocks in New Zealand

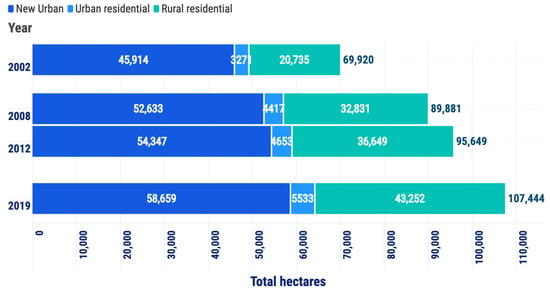

Much of New Zealand (NZ)’s highly productive land (Land Use Capability [LUC] classes 1–3) is increasingly threatened by expanding urban development. Figure 1 shows that between 2002 and 2019, the area of productive land lost to housing development rose by 54%, while the area of rural residential land increased by 109% [1,2], contributing to further fragmentation of the remaining productive land [2]. This trend threatens the spatial continuity and ecological integrity of peri-urban landscapes by converting urban–rural land into low-density residential development. It also compromises its capacity for both food production [3] and ecosystem services [4]. There is therefore a need for carefully considered strategic planning in these important peri-urban areas.

Figure 1.

Conversion of highly productive land (HPL) to residential parcels in New Zealand from 2002 to 2019. Source: Figure created by the author based on data from Stats NZ [2].

Over the past decades, a prominent characteristic of peri-urban development in New Zealand has been the conversion of rural or previously agricultural land, driven by the demand for lifestyle living and the financial gains from rural subdivision into lifestyle blocks [5,6,7].

1.2. Lifestyle Block Definitions

Lifestyle blocks (LBs), also known as hobby farms or lifestyle properties, are a subset of smallholdings—semi-rural properties not primarily used for commercial farming that typically emphasise residential and lifestyle use. In NZ, LBs have become a prominent feature in the peri-urban regions [5,6,7,8,9,10], accounting for 3.55% of the total national land base [11]. By comparison, despite having expanded rapidly in recent decades, urban land still only covers under 1% of New Zealand’s land mass [2]. Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) describes LBs as “generally in a rural area, where the predominant use is for a residence and, if vacant, there is a right to build a dwelling. The land can be of variable size but must be larger than an ordinary residential allotment. The principal use of the land is non-economic in the traditional farming sense, and the value exceeds the value of comparable farmland” [12].

LB characteristics vary by size, ownership motivation, land use, income level, and farming experience, making them difficult to describe using a standardised definition [5,8,9,13,14,15].

The main motivations for LB ownership include the desire for clean air, privacy, peace and quiet, open space, and an enhanced quality of life [9,10,16]. LB residents tend to prioritise non-commercial activities such as small-scale farming and gardening interests and self-sufficiency, alongside other recreational activities for personal enjoyment [5,7,8,10,15].

While size definitions vary slightly across regions and studies, both the Environment Canterbury Regional Council [17] and Eade [15] identify LBs as being in a size range between 1 and 20 hectares, with the majority around 5 hectares. Additionally, previous LB studies define an LB as a smallholding property between 0.4 and 30 hectares, with an average size of 5.2 hectares [9,10,16,18].

The essence concept of “lifestyle blocks”, which emphasises personal lifestyle aspirations over agricultural productivity and profit, with main income typically derived from off-farm activities, is consistently reflected across international literature from developed countries such as Australia, the United States, and Scotland [19,20,21,22].

1.3. The Challenges of Lifestyle Blocks in New Zealand

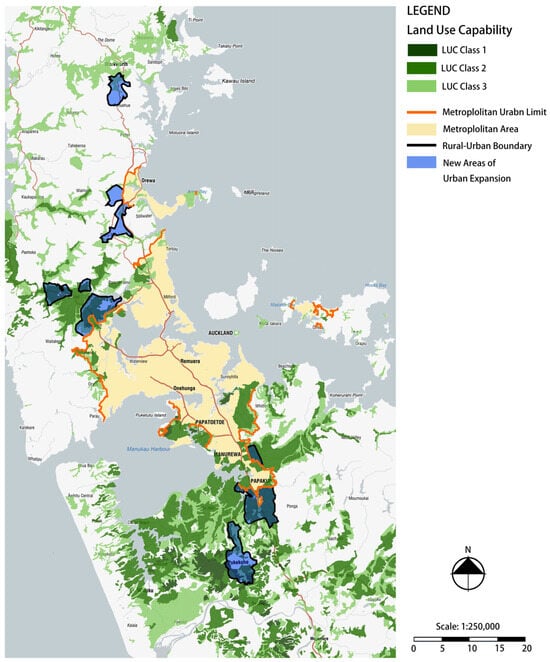

Less than 15% of NZ’s land area is considered to be highly productive land (HPL), making it a finite resource in the country [23,24,25]. By 2013, however, LBs already occupied nearly 10% of this HPL, with a significant concentration (35%) in the Auckland region alone [5] (see Figure 2). As much of NZ’s HPL is located on the urban fringes, it is particularly vulnerable to development pressure from both urban expansion and the growing demand for LBs [24,26,27]. This, combined with a historical lack of clear national direction before 2022, has contributed to the ongoing fragmentation and cumulative loss of this finite resource [24]. Figure 2 illustrates this trend in the Auckland region, where by 2019, 34% of Land Use Capability (LUC) class 1 land, 38% of class 2 land, and 19% of class 3 land had been, or had been earmarked to be, subdivided into small parcels [1].

Figure 2.

Map of HPL (LUC 1,2,3) in the proposed urban–rural boundary of Auckland. Source: Author’s own (2025) elaboration based on data from Manaaki Whenua–Landcare Research [28], Auckland Council [29], Silva [30], and Stats NZ [2].

Moreover, “Small blocks on versatile land are getting smaller from a median of 8 ha in 1970 to slightly under 4 ha in 2018” [15], indicating a continuing trend of HPL becoming more fragmented in NZ. MfE & Stats [25] further reinforced this finding by noting an increase in small-sized parcels (2–8 ha) and a decrease in larger ones (over 8 ha) on HPL during the same period. Increasing subdivision of production land has been seen as a threat to NZ’s agricultural land as it could lead to land fragmentation and decrease food security [31,32,33]. Curran-Cournane et al. [6] note that much of this fragmentation is “largely driven by the desire for rural lifestyle living or hobby farming”. Eade [15] agrees with this view and observes that it is likely to continue due to urban pressures such as residential expansion at the rural–urban fringe, competition for land near urban centres, and increasing landowner preferences for lifestyle living. However, this phenomenon has not been without criticism; some farmers have expressed discontent, arguing that the farmland subdivision policies have directly led to the loss of productive land [14,34,35].

1.4. Research Rationale and Knowledge Gaps on Lifestyle Blocks

Although the widespread and growing phenomenon and key challenges of LBs have been recognised, their environmental implications and consequences have received relatively little attention. Previous studies have often been focused on providing general descriptions of property characteristics and ownership motivations, with limited efforts to systematically explore environmental impact. Meanwhile, environmental research and related policies and regulations concentrate more on either urban residential areas or larger-scale agricultural land, leaving a noticeable gap in examining such residential–agricultural mixed land uses like LBs. However, given their “pleasure over profit” nature and increasing occupation of the HPL, LBs have the potential to balance lifestyle with production and conservation via sustainable practices. However, a detailed understanding of their resource use and land management is still insufficient.

1.5. Research Objectives

This paper aims to quantify existing knowledge on the environmental implications of LBs in peri-urban areas through a systematic literature review and highlight areas of research need and management action. It investigates studies about resource use patterns, land use allocation, land management practices, and landscape design strategies. The review also explores both the challenges LBs pose (e.g., land fragmentation, loss of HPL, biodiversity loss) and the opportunities they may offer (e.g., carbon sequestration, sustainable farming, energy efficiency, and water-saving technologies). It also aims to link potential environmental issues associated with LBs to NZ’s broader environmental sustainability agenda and provides an international context through reference to international cases in countries such as the United States (U.S.), Europe, and Australia, where LBs or similar developments are also prevalent. In addition, the review offers comparative insights for more effective and sustainable policy-making frameworks for LBs in NZ, drawn from policies and regulations, initiatives, and voluntary stewardship programs that other countries undertake in relation to similar properties.

2. Background

The term “lifestyle block” is recorded to have originated around World War II. Interest in such properties grew markedly in North America during the 1970s with the increase in urban-to-rural migration. Similar land use change trends also spread throughout some other developed countries, including the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, and NZ [19,20,36], though the key driving factors, such as demographics and institutional settings, varied across countries.

In NZ, the emergence of smallholdings and LBs was primarily driven by two factors: the rapidly rising land values under the urban expansion pressure, and the increasing interest in seeking rural lifestyle opportunities [8,10]. This trend has been further encouraged by the key drivers of liberal rural land subdivision policies and regulations, alongside an aging rural population, which has led older landowners to subdivide and sell their land for retirement purposes [8,10,16]. Additional contributing factors include superannuation reforms, declining farming profitability, limited planning policy controls, improved transportation networks, and growing lifestyle preferences for rural amenity and environmental value [8,16,37]. These combined forces have led to the fragmentation of larger agricultural parcels into smallholdings characterised by diverse land uses, including ecological restoration, small-scale farming, rural industries, and LB development [1,5,37]. Such development reflects a complex interplay of agricultural, economic, and socio-cultural changes.

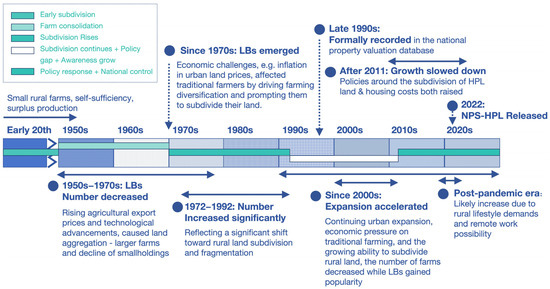

In the early 20th century, rural properties were typically small and aimed towards self-sufficiency, with surplus produce occasionally sold for income [5,15]. Rising agricultural export prices and technological advances during the 1950s to 1970s led to a doubling of rural land values and encouraged land aggregation, resulting in a decline in smaller properties as farming shifted toward larger, more efficient enterprises [5,38]. However, this trend reversed in the 1970s; the sustained inflation in urban land prices affected traditional farmers producing wool, meat, and dairy products, and forced farming diversification in response to the economic challenges, including prompting farmers to subdivide their land. At this time, smaller holdings began to emerge [5,15,19,38]; there were approximately 27,000 smallholdings covering nearly 100,000 hectares in 1976 [14,39]. Smallholdings started to increase significantly from that time on. (See Figure 3). McAloon [38] notes that between 1972 and 1992, the number of holdings below 40 hectares more than doubled, rising by over 130%, reflecting a significant shift toward rural land subdivision and fragmentation. Since the 1990s, due to continuing urban expansion, economic pressure on traditional farming, and the growing ability to subdivide rural land in response to social demand, the number of farms decreased while LBs gained in popularity [5,10,38].

Figure 3.

Timeline of the development of LBs and land subdivision in NZ. Source: Author’s own (2025).

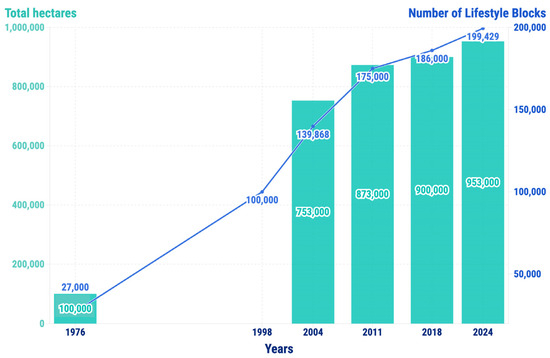

The number of LBs has been formally recorded in the national property valuation database since the late 1990s [5]. By 1998, the number had increased from an estimated 70,000 to 100,000 [14]. The expansion accelerated in the 2000s–2010s, reaching 139,868 properties (on more than 753,000 hectares) in 2004 [9,10], and growing to 175,000 properties on 873,000 hectares by 2011 [5]. After 2011, the growth rate in LBs slowed down a bit, with over 186,000 properties on nearly 900,000 hectares by 2018 [7]. By 2024, there were 199,429 LBs on 953,000 hectares [11]. This sustained growth is illustrated in Figure 4, which shows the progressive increase in the number and total area of LBs from 1976 to 2024.

Figure 4.

Growth of LBs in NZ from 1976 to 2024. Source: Jowett [39], Swaffield & Fairweather [34], Fairweather & Robertson [14], Andrew & Dymond [5], Pearson [7], and QV [11].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in the first quarter of 2025 using Scopus and Google Scholar. These two databases were selected due to their wide coverage of peer-reviewed publications in environmental science, land management, planning, and agricultural disciplines. To complement the academic literature, a separate set of NZ government and regional council documents was reviewed for contextual and policy insights related to LBs, peri-urban development, and land fragmentation. These policy documents were reviewed thematically but excluded from statistical analyses (e.g., country or year of publication) to ensure comparability across peer-reviewed academic sources. Selected doctoral dissertations and conference papers were included to capture emerging research and relevant grey literature, particularly in areas where peer-reviewed publications were limited.

3.1.1. Scopus Search

A keyword-based search was performed in Scopus using the following terms in the title, abstract, and keywords fields: (“lifestyle block*” OR “lifestyle property*” OR “hobby farm*”). This initial search yielded 163 results. A large number of these articles focused on environmental and social issues. Subject area filters were applied to include only literature related to Environmental Science, Social Sciences, Agricultural and Biological Sciences, and Earth and Planetary Sciences. To maintain contextual relevance, the review focused on studies from NZ and international cases from countries with rural residential development patterns that may offer relevant comparisons. After applying these subject filters and removing duplicates and clearly irrelevant records based on title and abstract screening, a total of 76 articles were retained for full-text review.

3.1.2. Google Scholar Search

Use of the same initial keywords in Google Scholar produced 4060 results, which was considered overly broad and not feasible for manual screening. To refine the results and enhance relevance, a more targeted search string was developed: (“lifestyle block*” OR “lifestyle property*” OR “hobby farm*”) AND (“environmental impact” OR “peri-urban”). This reduced the number of articles to 515. To ensure analytical depth in the review of national literature while situating it within a broader global perspective, the articles were organised into two categories: New Zealand-based studies and relevant international literature. To support this distinction, another targeted search string was applied to specifically identify New Zealand-focused studies: (“lifestyle block” OR “lifestyle property” OR “hobby farm*”) AND (“environmental impact” OR “peri-urban”) AND (“New Zealand”). This search yielded 215 results, forming the core dataset for the national literature review.

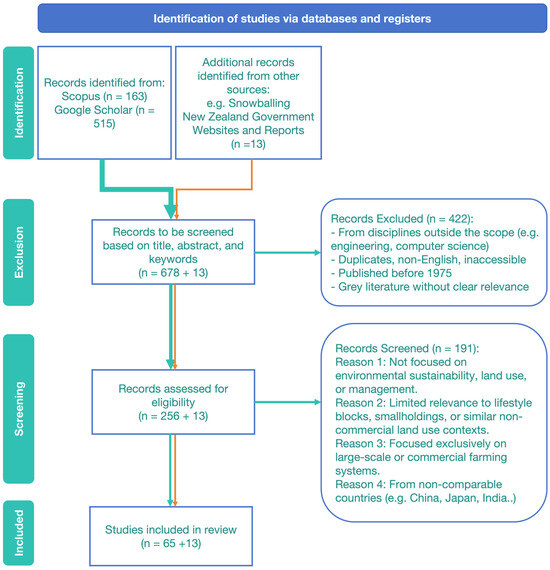

3.2. Selection Process

The selection process followed the PRISMA framework (see Figure 5) to ensure a transparent and systematic approach to identifying and evaluating relevant literature. First, a total of 619 records were identified from Scopus and Google Scholar databases (see Section 3.2). After removing duplicates, the remaining records were screened for relevance to the research objectives based on their titles and abstracts. For records with unclear relevance, a quick full-text scan was undertaken to ensure the accuracy of initial screening results. Second, a comprehensive full-text review was conducted to assess eligibility based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Section 3.4). Third, additional relevant grey literature was reviewed separately through manual methods, as described in Section 3.2. Finally, all eligible academic and policy sources were retained for thematic coding and synthesis.

Figure 5.

PRISMA model. Source: Author (2025).

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles and documents were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, or doctoral dissertations published within the past 50 years, with a primary focus on the period from 2000 to 2025. The choice of timeframe to study corresponds to a notable acceleration in LBs since the 2000s. An examination of more recent studies can also better reflect current land use changes and environmental concerns. Articles were also selected based on (b) content addressing environmental issues, land use, sustainability in the context of lifestyle blocks, lifestyle properties, hobby farms, smallholdings, or similar peri-urban rural properties such as non-commercial farms. Only studies that examined or included relevant cases from New Zealand, Australia, the United States, Canada, or the United Kingdom were considered, given the comparability of their socio-environmental and land use conditions.

The exclusion criteria included the following: (a) studies unrelated to environmental sustainability or land management (e.g., studies in computer science or engineering), as well as (b) those based in countries with significantly different socio-economic and land use conditions compared to NZ (e.g., densely urbanized or high-intensity agricultural regions in countries such as China, Japan, or India). (c) Publications that focused solely on large-scale commercial agriculture or lacked relevance to small-scale, non-commercial land use settings (e.g., lifestyle blocks or smallholdings) were excluded. (d) Duplicate records, (e) inaccessible full texts, (f) grey literature without clear relevance, (g) non-English publications, and (h) publications prior to 1975 were removed from consideration.

3.4. Output

Following the selection process, a total of 65 academic publications were retained after full-text screening. In addition, 13 national and regional policy documents and government reports were reviewed separately from academic journal articles to distinguish practical policy from scholarly research. This resulted in 78 sources for further analysis. Of these, 42 articles focused on New Zealand, while the remaining 36 represented international cases from comparable countries. A full list of the reviewed sources is provided in Appendix A.

3.5. Study Characteristics and Distribution

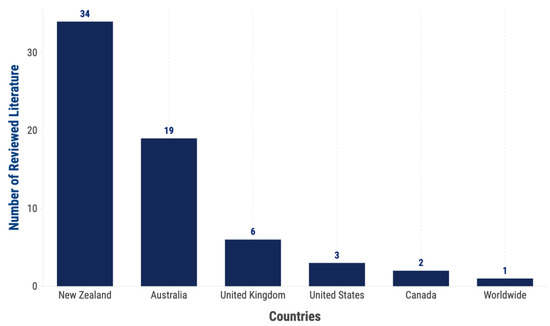

Most of the literature was focused on New Zealand and Australia, where LBs are widespread and considered significant in land use change (Figure 6). However, despite increasing attention in recent years, systematic assessments of LBs’ environmental impacts are still limited, and there is a lack of in-depth investigation. Studies from New Zealand account for over half of the total, reflecting the importance of LBs as a subject in the country’s land use and environmental research. Australian studies highlight the clearing of native bush and forests for LB development, raising concerns about habitat loss and threats to endangered species [37]. They also address related issues such as land fragmentation, natural resource management, and amenity-driven rural migration. Additional studies were mainly identified from the US, the UK, and Canada, where rural subdivision patterns, socio-environmental challenges, and hobby farming practices show notable similarities with those in NZ. Cross-country comparisons highlight shared patterns of LB development and their relevance to international policy discussions and comparative case studies. While most of the literature is country-specific, a number of articles have conducted cross-regional or comparative studies [5,20,37,40].

Figure 6.

Distribution of reviewed literature by country. Source: Author (2025). Note: The 13 NZ policy documents were excluded to ensure consistency across peer-reviewed sources and avoid inflating NZ’s representation.

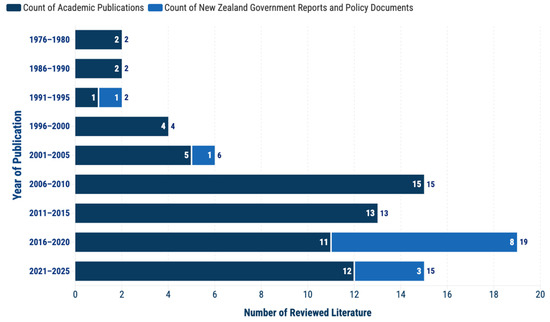

In terms of publication timeline, the reviewed literature spans from the 1980s to 2025, with a notable increase in output over the past two decades. As shown in Figure 7, academic attention to LBs began to increase in the early 2000s, coinciding with the accelerated expansion of LBs during that period. Publication output rose more markedly from the 2010s onward, reaching its peak between 2020 and 2025. This trend reflects the intensified scholarly interest in land use sustainability, ecosystem degradation, and the environmental impacts of dispersed rural living.

Figure 7.

Distribution of reviewed literature by year. Source: Author (2025). Note: The chart includes both academic publications and New Zealand government reports and policy documents.

3.6. Thematic Categorisation of Literature

To systematically capture the environmental dimensions explored across the literature, thematic coding was conducted to focus on the research objectives, scope, and the terminology used by authors. Five major themes were identified: (1) water resource use and management, (2) food production and livestock management, (3) energy consumption and carbon emissions, (4) biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services, and (5) regulation and planning policies.

These categories, further discussed in Section 4.1.1, Section 4.1.2, Section 4.1.3, Section 4.1.4, illustrate the increasingly multi-dimensional nature of LB development, underscoring both current research priorities and areas where further investigation is needed to support sustainable land management.

4. Results

4.1. Environmental Implications of Lifestyle Blocks

Over time, the focus of LB research has shifted. Early studies (1980s–early 2000s) mainly explored demographic characteristics, motivations, land use patterns, and lifestyle choices of LB owners, along with rural land fragmentation and related planning challenges. Since the 2000s, as LBs expanded, research attention has turned toward environmental concerns, particularly the occupation of HPL and pressures on food production, natural resources, and ecosystems. This shift reflects a growing recognition of LBs as not only socio-economic phenomena but also key drivers of environmental change in rural and peri-urban landscapes.

The continued expansion of LBs has resulted in a range of environmental impacts, including land fragmentation, the loss of highly productive farmland, habitat degradation, and reduced populations of indigenous species [41], with consequences for soil health, food production capacity, water systems, and biodiversity [26]. Andrew and Dymond [5] and Curran-Cournane et al. [42] also highlight the irreplaceable and irreversible impact of converting high-class agricultural land into lifestyle or urban subdivisions, noting that such conversion reduces productive capacity due to fragmentation and the loss of scale required for efficient farming. Once land is subdivided for residential use, it is rarely restored to productive agricultural purposes, especially when permanent infrastructure such as roads and buildings is in place, making the change effectively irreversible.

From an international perspective, studies such as those by Andrew and Dymond [5] and Song et al. [43] observe a significant and growing trend of LB development in peri-urban regions, particularly in developed countries like Australia, the U.S., and the UK. This expansion has raised similar concerns around land fragmentation, environmental pressures, and the loss of farmland, as subdivision disrupts contiguous agricultural land and undermines local food production capacity [20,40]. Furthermore, studies such as that by Cook and Fairweather [10] found that smallholders generally show limited engagement in chemical management, soil and water quality monitoring, native vegetation growth, and organic farming initiatives, resulting in modest contributions to environmental sustainability compared to traditional farmers.

Despite these concerns, several studies identify potential opportunities for LBs to enhance ecological and food system outcomes. For instance, Hart et al. [44] acknowledge benefits such as improved water quality from reduced intensive farming, enhanced biodiversity protection on private land, and the revitalisation of rural communities through increased population and economic activity. Positive environmental outcomes may also result from collective land management, ecological restoration, and a shift away from conventional farming practices [44,45]. Similarly, Polyakov et al. [22], Pearson [7], and Our Land and Water National Science Challenge (OWL) [46] emphasise the environmental value of planting native trees and establishing green corridors, which can address habitat fragmentation and promote ecological connectivity. Song et al. [43] argue that LB owners can play a key role in the multifunctional transition of peri-urban landscapes by preserving green space and practising sustainable land management, thereby potentially reducing the fragmentation pressures. In terms of productivity, small-scale farming on LBs can help reduce food miles and strengthen resilient local food systems. With appropriate support and flexible land use arrangements, practices such as regenerative grazing and high-value horticulture (e.g., organic kiwifruit orchards) can enable LB owners to contribute positively to both environmental and economic outcomes [15].

Beyond land use and biodiversity, the broader water–food–energy–biodiversity nexus is increasingly recognised as central to understanding the sustainability of LBs at the household level [47,48,49]. As integrated systems of living, production, and consumption, LBs influence both biophysical conditions and household resource use. These interrelated dimensions call for a holistic perspective on LB sustainability. Accordingly, the following sections examine key domains of environmental impact and opportunity, including household consumption patterns in water and energy use, food systems, and biodiversity management.

4.1.1. Water Resource Use and Management

Cook & Fairweather [10] identify water scarcity as one of the most important issues among LB communities. LBs generally have a strong dependence on natural water supplies such as rainwater, groundwater, and streams, which makes them particularly vulnerable and sensitive to water-related risks like droughts and floods [47]. However, while LB residents demonstrate a strong commitment to conserving water resources [47], their land use activities, such as fertiliser use, livestock overstocking, and poor septic tank management, can place considerable pressure on the quality of freshwater ecosystems [50]. This tension between environmental intentions and actual impacts reflects broader challenges, where technical knowledge gaps, infrastructure limitations, and lifestyle-driven reliance on local water supplies exacerbate risks, particularly in areas with weak governance [51,52]. Several studies addressing water-related issues on LBs are shown in Table 1.

As the number of LBs continues to grow, concerns have been raised over the potential for cumulative impacts. Evidence from Lake Rotorua shows that nutrient leaching and runoff from multiple lifestyle blocks have contributed to water quality degradation [50]. At the same time, Davis et al. [53] argue that the subdivision associated with the growth of LBs in peri-urban areas represents a form of land use intensification, increasing competition for limited water resources and placing additional strain on riparian and groundwater systems. While individual LBs may have relatively low production outputs, their cumulative impact on freshwater ecosystems is considerable.

Recognising these interconnected challenges, policy interventions such as NZ’s Freshwater Farm Plans (FW-FPs) have been introduced to guide better land and water management practices, including erosion control, nutrient management, and climate change adaptation [54]. Although currently paused, FFPs can still provide useful guidance for landowners. Regional councils (e.g., Environment Canterbury) also provide practical recommendations and management guidance for LB owners, including advice on regular leak checks, infrastructure planning to prevent runoff, protection of trough valves, and irrigation based on soil moisture levels.

In addition, studies highlight that access to water is becoming increasingly complex and costly for LB owners, which adds another layer of difficulty, as sustainable water use is not only influenced by individual behaviour but also shaped by broader market structures and governance capacity [55]. Furthermore, climate change has exacerbated uncertainties surrounding water availability and further compounds these issues by amplifying the risks associated with drought, flood, and changing rainfall patterns.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on water use and management on New Zealand lifestyle blocks.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on water use and management on New Zealand lifestyle blocks.

| Author | Year | Methods | Key Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lawrence & McManus [51] | 2008 | Questionnaire + Interviews (Mixed methods) | Despite strong environmental intentions, households in low-density areas saw little change in water use due to infrastructure limits—water sustainability needs systemic support beyond individual behaviour. |

| Bay of Plenty Regional Council [50] | 2018 | N/A | LBs around Lake Rotorua affect water quality through nutrient leaching and runoff, caused by overstocking, improper fertilizer use, and poorly maintained septic systems—showing that even small blocks can harm freshwater ecosystems. |

| Adeyeye et al. [52] | 2020 | Case study + Semi-structured interview + Workshop (Qualitative) | Lifestyle-driven water use and reliance on local sources can worsen water marginality where infrastructure and governance are weak. |

| Robinson & Song [55] | 2023 | Questionnaire survey + Interviews (Mixed methods) | Growing LBs have increased water demand, but rising costs and complex markets make access harder, showing the need for better water governance to balance lifestyle, farming, and sustainability. |

| Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) (Paused) [54] | 2025 | N/A | NZ freshwater farm plans aim to help farmers, including LB owners, manage risks like erosion, nutrients, and effluent with site-specific actions to improve freshwater quality and support climate change adaptation. |

| Environment Canterbury [17] | 2025 | N/A | LB owners are encouraged to manage water wisely by checking for leaks, protecting trough valves, planning infrastructure to avoid runoff, clearing debris from waterways, and irrigating only when soil moisture requires it. |

| Villamor et al. [47] | 2025 | Phone survey + Workshops (Mixed methods) | LB owners are generally more concerned about water quality than traditional farmers. They rely heavily on natural water sources like rainwater, streams, and groundwater and are vulnerable to drought. They have less technical knowledge about water systems compared to farmers. |

4.1.2. Food Production and Livestock Management

As previously discussed, the expansion of LBs onto HPL has raised concerns about long-term food production capacity and essential soil ecosystem services [5,26,42,56]. Carrick et al. [56] report a further decrease of approximately 50,000 hectares of land potentially available for primary production between 2002 and 2019, largely due to the spread of diffuse rural residential development. This substantial reduction further highlights the threat LBs may pose to regional food security.

Although the MfE and Stats NZ [26] acknowledge the difficulty of quantifying the impacts of land fragmentation and the productivity of LBs, their more recent reporting [26] highlights growing concerns that continued conversion of HPL will intensify pressure on NZ’s food production systems. Curran-Cournane et al. [42] express concern that the spread of LBs onto HPL could limit future food production capacity; however, these claims are not supported by direct empirical data, highlighting the need for more targeted research into the biophysical impacts of LB development.

Understanding the actual role of LBs in food and livestock production is therefore critical. As summarised in Table 2, studies by Millar and Roots [31] and Sanson et al. [9] show that most LBs are characterised by low-intensity, diversified production aimed at self-sufficiency rather than commercial output. Typical practices include growing fruits, vegetables, niche crops, and maintaining small numbers of livestock such as sheep, goats, chickens, and cattle, mainly for household consumption or local markets. These systems are often motivated by lifestyle preferences and environmental values rather than financial returns, limiting their contribution to the national food supply but enhancing household resilience and rural diversity. Earlier studies also underline the limited productive role of LBs; for example, Daniels [13] observed that hobby farms and lifestyle properties are generally not focused on large-scale food production and recommended that such developments be located away from prime agricultural land. Sutherland et al. [57] found that non-commercial farms maintain small amounts of livestock and minimal crop production, with some signs of land abandonment, although mixed smallholdings continue to support local food systems. Song et al. [43] and Sise [58] further highlight that while small-scale food and livestock production on LBs is often underreported, it contributes to rural landscape diversity and localised food resilience.

In the Australian context, Millar and Roots [31] noted that although peri-urban regions account for less than 3% of Australia’s total land area, they contribute nearly 25% of the country’s gross value of agricultural production. While this productivity is largely driven by intensive horticulture, these areas have also seen increasing land use change, including the rise of LBs. Meanwhile, Davis et al. [3] caution that subdivisions onto HPL can intensify land use conflicts and undermine local food systems if not managed sustainably. These findings suggest that the productive potential of LBs depends heavily on owner motivations, management practices, and supportive planning frameworks.

Despite these challenges, there is increasing recognition of the untapped potential of LBs. Eade [15] argues that with effective management, LBs could significantly enhance NZ’s local food production without compromising lifestyle aspirations. Strategies such as regenerative grazing and small-scale cropping, tailored to owners’ interests, are seen as critical pathways for realising this potential. Similarly, Our Land and Water [46] suggests that optimised use of lifestyle properties could diversify rural economies through small-scale farming, agritourism, and direct sales. Although commercial farming is seldom the primary aim [31], lifestyle properties can nonetheless strengthen localised food networks and enhance regional food system resilience when sustainably managed.

In summary, while LBs are often criticised for inefficiency and the loss of productive land, they also present opportunities to support diversified, small-scale food production models that align with broader sustainability and resilience objectives, provided that appropriate land use planning and management support is in place.

Table 2.

Summary of studies on food production and livestock on New Zealand lifestyle blocks.

Table 2.

Summary of studies on food production and livestock on New Zealand lifestyle blocks.

| Author | Year | Methods | Key Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniels [13] | 1986 | Literature review + Case study + Secondary data (Qualitative) | Hobby farms are not oriented toward food production and often keep small-scale livestock for personal or recreational purposes. LBs should be located on lower-quality land away from core agricultural zones to preserve productive farmland. |

| Sanson et al. [9] | 2004 | Questionnaire + Literature review + Case study + Secondary data (Mixed methods) | Smallholdings often grow fruit, vegetables, and keep livestock like sheep and cattle for personal use, reflecting lifestyle preferences and sustainable land stewardship. |

| Millar & Roots [31] | 2012 | Literature review (Qualitative) | LBs in Australia contribute little to national food output, but occupy high-quality farmland and support small-scale horticulture and livestock for personal or niche use. With proper planning, they may strengthen local food systems. |

| Andrew & Dymond [5] | 2013 | GIS-based spatial analysis (Quantitative) | LBs take up a large share of NZ’s high-quality farmland, contribute little to food production due to low productivity and non-commercial use, raising concerns about land use efficiency and food security. |

| Curran-Cournane et al. [42] | 2014 | GIS-based spatial analysis+ Land use measurement (Quantitative) | High-quality land for vegetables, fruit, and dairy is being lost to urban growth and LBs. While some LBs use pastoral land, few produce food or livestock commercially, posing risks to food self-sufficiency and resilience. |

| Sutherland et al. [57] | 2019 | Census data analysis + Typology building + Cluster analysis (Quantitative) | Non-commercial farms (NCFs) typically keep small numbers of livestock, with limited crop production; some show signs of abandonment, though mixed and amenity farms still contribute to food and land use. |

| Carrick et al. [56] | 2020 | Indicator analysis + GIS + Spatial overlay analysis (Quantitative) | Reduced capacity for food production on HPL. Livestock-based agriculture is declining as small subdivisions are unsuitable for large-scale livestock operations. Land fragmentation may weaken future food security and rural ecosystem services. |

| Song et al. [43] | 2022 | Survey + Semi-structured interview (Mixed methods) | Produce food and raise livestock at small, diverse scales—mainly for self-provisioning or lifestyle reasons. Activities such as fruit growing and cattle keeping support land care, local food systems, and rural landscape diversity through low-intensity, multifunctional land use. |

| Sise [58] | 2022 | GIS-based spatial analysis + Survey data (Quantitative) | LBs keep livestock for non-commercial use and now cover a large area in NZ. Though underreported in farm statistics, they may explain much of the missing livestock data. Their food output is small, but their overall impact is notable. |

| Davis et al. [3] | 2023 | Survey + Statistical analysis (Mixed methods) | LB subdivisions on HPL cause land use conflicts and threaten local food production. Some owners grow vegetables or keep animals for personal use, large-scale/commercial production is rare. Many value access to local food but raise concerns about environmental impacts and reverse sensitivity. |

4.1.3. Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions

Existing research indicates that, at a household level, electricity use, transportation, and agricultural operations, including livestock management, are among the largest contributors to overall energy consumption and associated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [48,49]. On LBs, these patterns present unique challenges and opportunities for sustainable management (Table 3).

Sise [58] finds that many LB owners keep livestock they kept for non-commercial or recreational purposes, and these animals are often not officially recorded in NZ’s GHG inventory. The author estimates that this underreporting could result in a 5–8% increase in GHG emissions from beef production and a 1–2% rise in total livestock-related emissions, largely due to unreported livestock. This hidden carbon emission is concerning given that approximately 60% of LBs have beef cattle [18], a sector known for high methane emissions and significant impacts on water and energy consumption. These findings suggest that even small-scale livestock holdings, when aggregated, can exert substantial environmental pressure.

In terms of household electricity use, Qi [59] discusses a typical example of an LB not connected to the public electricity grid, which relies on off-grid solar DC microgrids. In such cases, the use of solar PV systems is emphasised to ensure energy reliability and sustainability, reducing power conversion losses and environmental impacts compared to conventional systems. Qi [59] further emphasises that integrating renewable technologies to meet small-scale demands, such as water pumping and irrigation and animal control systems, can play an important role in reducing emissions from LBs. Transport-related emissions also form a major component of the environmental impacts of LB households. Data from Greater Auckland [60] indicate that peri-urban and rural households, including those living on LBs, typically produce higher transport emissions due to greater car dependence, longer commuting distances, and limited access to public transport. Larger property sizes further amplify electricity use, especially where water systems like rainwater harvesting depend on electric pumps.

Although these trends are increasingly recognised, there remains a significant gap in empirical research specifically examining the energy consumption profiles and carbon emissions of LB households in NZ and internationally.

Table 3.

Summary of studies on energy use and carbon emissions in New Zealand lifestyle blocks.

Table 3.

Summary of studies on energy use and carbon emissions in New Zealand lifestyle blocks.

| Author | Year | Methods | Key Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sise [58] | 2022 | GIS-based spatial analysis + Survey data (Quantitative) | Livestock on LBs, though usually excluded from national GHG reporting, could add 5–8% more beef emissions and 1–2% to total livestock emissions. |

| Qi [59] | 2023 | Case study | LBs are located in remote areas with limited infrastructure, making it difficult to connect to the public electricity grid. Therefore, the author suggests installing solar panels to address small-scale electricity demands, such as water pumping and irrigation. |

4.1.4. Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Services

Regarding biodiversity and ecosystems, in NZ, “private land hosts a quarter of the remaining native vegetation nationwide, including 17% of native forest types that are under-represented in legally protected land” [27]. As Simcock et al. [61] demonstrate, urban expansion and development involve extensive vegetation removal, which reduces the size and connectivity of habitats for indigenous species. In addition, the subdivision of former agricultural or low-intensity rural land to smaller parcels may disrupt local ecosystems, reduce wildlife corridors, threaten biodiversity, degrade soil organic matter, and reduce carbon sequestration capacity.

The research examined showed that LB owners in NZ have demonstrated a strong willingness to engage in biodiversity conservation practice (Table 4). Pearson [7], through a survey in peri-urban Palmerston North, concludes that LB owners actively engage in environmental stewardship practices, such as native planting, improving habitat connectivity, and pest and weed control. As a result, their collective management behaviours could significantly influence ecosystem services and biodiversity conservation. In an earlier case study, Moller and Moller [45], looking at the Tūmai Beach Sanctuary, explored how LB owners engage with biodiversity conservation and suggested that they are likely to support ecological restoration efforts, which can enhance local landscape ecology and increase property value.

Despite the potential for biodiversity conservation, LBs are also shown to be facing ecological challenges and barriers to effective conservation through woody weed invasion, traditional farming interference (e.g., weed dispersal, effluent pollution, land clearance), and ecosystem degradation [45]. Meurk et al. [4] also stress that without coordinated land use planning and sustainable management strategies (e.g., habitat preservation and stormwater regulation, particularly in fragmented peri-urban landscapes), the positive biodiversity contributions of LBs are easily undermined by ongoing land fragmentation, uncoordinated development, and isolated conservation efforts.

Despite these challenges, more structured support and specialised knowledge in biodiversity aspects need to be considered in LB management. Polyakov et al. [62] emphasise that LB owners in NZ are willing to participate in native forest restoration programs if supported by appropriate incentives. Strategies such as providing seedlings, offering technical support and planting guidance, implementing certification schemes, designing flexible programs, and reducing administrative barriers are particularly effective in encouraging participation. These actions contribute to enhanced ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration, erosion control, and habitat restoration.

Furthermore, according to the Interim Climate Change Committee [63], farms (including LBs) that have post-1989 forests that are at least 1 hectare in size, 5 m in height at maturity, with 30% crown cover and 30 m in width are eligible for the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) [64]. NZ has lost more small blocks of trees and vegetation (e.g., riparian planting, wetland) that could potentially be counted as carbon sequestration targets than it has gained since 1990 at the national level. The report demonstrates that although joining the NZ ETS would bring challenges to LBs, it would allow conservation and biodiversity protection actions to yield both environmental and financial benefits.

Compared to water management, biodiversity conservation on LBs presents greater challenges due to its dependence on ecological connectivity, complex ecosystem dynamics, and the need for long-term, coordinated management efforts. While water resource interventions can often be effective at the property level, effective biodiversity protection requires collective actions, professional ecological guidance, and sustained policy support to ensure habitat continuity and functional ecosystem resilience.

Research on biodiversity conservation in Australian LBs offers valuable insights and lessons that can be integrated into the NZ context. Song et al. [43] argue that LBs play a vital role in Australia’s peri-urban areas, serving as ecological buffers that maintain productivity while preserving environmental values and enabling the coexistence of farming, gardening, and conservation activities. Supporting this view, Polyakov et al. [22] further observe that the value of ecosystem services is maximised when native vegetation covers at least 40% of a property. However, they also report that the current median coverage is only 15% in Australia, highlighting a significant gap and the need for large-scale restoration efforts. In addition, Marshall et al. [65] caution that limited engagement with invasive species management undermines biodiversity goals, and they call for stronger community-based governance. Drawing on these findings, Moller and Moller [45] suggest that, similar to Australia, NZ should also consider increasing indigenous vegetation on LBs to enhance habitats for native bird species [65], improve landscape value, and potentially raise land prices.

Table 4.

Summary of studies on biodiversity and ecosystem services in New Zealand lifestyle blocks.

Table 4.

Summary of studies on biodiversity and ecosystem services in New Zealand lifestyle blocks.

| Author | Year | Methods | Key Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moller & Moller [45] | 2012 | Literature review + Field observations + Case study (Qualitative) | Conventional LBs often exacerbate biodiversity loss and ecological fragmentation, alternative models featuring collective management and ecological restoration, such as Tumai Beach Sanctuary, can enhance biodiversity and ecosystem services. |

| Meurk et al. [4] | 2013 | Literature review + Data synthesis (Qualitative) | Supporting biodiversity and delivering ecosystem services (e.g., habitat preservation, stormwater regulation). Risks from land fragmentation if not ecologically planned. |

| Polyakov et al. [22] | 2013 | GIS analysis (Quantitative) | Native vegetation on LBs offers amenity and ecosystem benefits, with around 40% cover being optimal. While too much vegetation can limit other uses, most LBs could gain biodiversity and environmental value by increasing native cover. |

| Marshall et al. [65] | 2016 | Case study+ Telephone survey + Workshop (Mixed methods) | Less engaged in invasive species control, but essential to landscape-level biodiversity and ecosystem service outcomes. Collective action and community-based governance can improve their integration into conservation and weed management. |

| Sambell et al. [66] | 2019 | Survey + Field sampling (Quantitative) | LBs, with mixed vegetation and low-intensity use, support diverse bird species and offer potential for habitat restoration, though outcomes depend on vegetation cover and management practices. |

| Pearson [7] | 2021 | Questionnaire survey (Mixed methods) | Strong environmental awareness, engaging in practices such as planting native vegetation for habitat restoration, erosion control, and protecting water quality through riparian planting, especially with community support. |

| Polyakov et al. [62] | 2024 | Choice experiment + Questionnaire survey (Quantitative) | LB owners are willing to restore native forests if supported by incentives (e.g., free seedlings, guidance, flexible programs), enhancing ecosystem services like carbon storage and erosion control. |

| MfE & Stats NZ [27] | 2024 | N/A | Unmanaged grazing, land fragmentation, and invasive species continue to limit their potential to provide ecosystem services such as habitat connectivity, erosion control, and native species protection. |

4.2. Regulation and Environmental Policies Relevant for Lifestyle Blocks

In NZ, although most recent government environmental policies have primarily focused on farmers and farm practices [7], many of these frameworks have since evolved to incorporate LBs, aiming to manage their environmental impacts while recognising their unique land use patterns. Table 5 provides an overview of key NZ policies relevant to or that may impact LBs. The Resource Management Act (RMA) 1991 [67] marked a major shift by introducing effects-based planning and granting local councils discretion over subdivision decisions. Although the Act does not explicitly promote subdivision, it enables the growing process and creates regulatory space for the expansion of LBs, particularly in peri-urban areas.

To address growing land fragmentation, regional councils introduced strategies through Regional Policy Statements (RPSs), aiming to manage unplanned development and designate rural–residential zones to reduce infrastructure costs and land use conflicts [44]. However, systematic monitoring has remained limited, with only a few councils (e.g., Waikato, Auckland, Marlborough) maintaining formal systems to track land use changes, subdivision consents, and pressures on HPL. Recognising the continued risks to HPL, the government introduced the National Policy Statement for Highly Productive Land (NPS-HPL) 2022 [68], which establishes strict land use regulations that significantly impact LBs, peri-urban development, and the management of HPL. It further restricts urban expansion into peri-urban agricultural zones, ensuring that land-based primary production remains prioritised over residential use. Additionally, the NPS-HPL mandates measures to mitigate reverse sensitivity effects, such as setbacks and buffers, to prevent conflicts between lifestyle developments and agricultural operations.

At the local level, these national objectives are reflected in plans such as the Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP) [29], which encourages LBs to be located within the designated areas such as the “Countryside Living Zone”. This zoning approach aims to maintain a low-density rural character while preventing excessive land fragmentation and land use conflict. The AUP also incorporates measures to address reverse sensitivity, such as buffers and setbacks, to manage interactions between LBs and surrounding agricultural activities. By directing LBs away from high-value production zones and into planned rural–residential areas, the policy framework balances demand for rural living with the need to safeguard productive and ecologically valuable land. Curran-Cournane et al. [42] similarly emphasise the need for stronger land use regulations to limit the encroachment of lifestyle development on versatile farmland and ensure long-term land sustainability.

In addition to regulatory planning policies and interventions, national and regional authorities have introduced farm-level environmental management tools to promote sustainable land use on both commercial farms and LBs. Farm Environment Plans (FEPs) [69] have been implemented since the early 2010s in regions like Canterbury to support landowners in identifying environmental risks and developing practices that improve soil, water, and biodiversity outcomes. Similarly, Freshwater Farm Plans (FW-FPs) [54] were introduced through 2020 amendments to the Resource Management Act and are now required under the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management [70]. These plans apply to a range of properties, including LBs, particularly those over 5–20 hectares or with intensive land uses and require landholders to assess on-farm freshwater risks and adopt practical mitigation measures [54,71].

Incentive-based approaches are also necessary for promoting land stewardship. Morrison et al. [72] highlight that government incentives can encourage LB owners to participate in conservation programs. Building on this, Polyakov et al. [62] show that both financial and non-financial incentives can effectively motivate private landowners, including farmers, livestock producers, and LB owners to engage in native afforestation, with LB owners demonstrating stronger willingness to participate than commercial farmers, as they tend to prioritize biodiversity and aesthetic values over financial returns.

Table 5.

Summary of policies relevant to lifestyle blocks in New Zealand.

Table 5.

Summary of policies relevant to lifestyle blocks in New Zealand.

| Policy/Act | Year | Scope | Relevance to Lifestyle Blocks |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Legislation Law | |||

| Resource Management Act (RMA) [67] | 1991/ Amended 2024 | An effects-based legal framework for managing land, water, and other resources; promotes sustainable management | All subdivision activities require resource consent (under Section 11 of the RMA); this has facilitated LB expansion in peri-urban areas under council discretion. |

| Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 [73] | 2019 | A legal framework for setting emissions reduction targets, carbon budgets, and adaptation plans; it created the Climate Change Commission to guide and monitor NZ’s climate action. | Promotes sustainable land use and emission reduction practices, which will indirectly influence all landowners, including LB owners. |

| National Policy Statements (under RMA) | |||

| National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FM) [70] | 2020/Amended 2024 | Sets national direction for freshwater protection and use, prioritizing ecosystem health and Te Mana o te Wai. | Influences land use rules affecting LBs; larger (over 5–20 ha) or intensive LBs may be required to manage freshwater risks through local regional plans. |

| National Policy Statement for Highly Productive Land (NPS-HPL) [68] | 2022/Amended 2024 | Protects NZ’s HPL for long-term land-based primary production. Restricts subdivision, rural lifestyle zoning, and non-agricultural land use. | Restricts LB subdivision and rezoning on HPL, only allowed in limited cases (Clause 3.10). Shapes local planning rules affecting LB development. |

| Regional and Planning Tools | |||

| Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP) [29] | 2013/Updated 2025 | Integrates regional and district planning under the RMA to manage Auckland’s land use, growth, and infrastructure over 30 years. Establishes the Rural Urban Boundary (RUB) and zoning rules for development. | Allows LBs in designated zones (e.g., Countryside Living) to manage land fragmentation and rural character, restricts subdivision, land use intensity, and infrastructure provision. |

| Regional Policy Statements (RPSs) | Ongoing (prepared by regional councils under the RMA) | Set out the overarching resource management goals and directions for each region. Guides regional and district plans. | Influences how LBs are zoned, subdivided, and managed within each region. Some regions (e.g., Waikato, Auckland) explicitly state in their RPSs the need to control lifestyle subdivision due to the pressure it places on land productivity and infrastructure. |

| Farm Environment Plans (FEPs) [69] | 2000s—Ongoing | Assists landowners identify and manage on-farm environmental risks to improve soil, water, and ecosystem outcomes. | Demonstrating good environmental stewardship. In regions (e.g., Canterbury), FEPs are mandatory for properties exceeding certain thresholds (over 20 ha). Larger or intensively managed LBs may fall within scope. |

| Freshwater Farm Plans (FW-FPs) [54] | 2023/ Paused 2024 | To identify, assess, and manage on-farm environmental risks to freshwater resources, aligning with the principles of Te Mana o te Wai. | LBs exceeding 20 ha in arable or pastoral use, or 5 ha in horticultural use, are required to develop FW-FPs. Smaller LBs may benefit from voluntary adoption to enhance environmental stewardship. |

4.3. Lifestyle Blocks in a Global Context

In Australia, Luck et al. [37] describe the rise of the “tree change” phenomenon, a demographic urban to non-coastal rural movement trend driven by desires for environmental amenities, affordable rural living, and a more nature-oriented lifestyle. This is closely associated with the development of LBs in NZ [7], where similar motivations prioritise amenity and ecological value over commercial agriculture [22,72,74,75]. While such relocation can bring new energy to rural areas, it also introduces challenges that might lead to landscape fragmentation, water quality degradation, and biodiversity loss through low-density housing in sensitive environments [37]. Tensions may also arise between long-term residents and newcomers due to differing expectations, values, and land use practices [37]. Millar and Roots [31] identify policy gaps that permit farmland conversion without addressing long-term food security, calling for land use strategies that incorporate lifestyle landowners into national climate adaptation efforts, which also align with recent policy directions emerging in NZ. Wadduwage [33] further links farm subdivision in peri-urban areas to urban expansion and rising land values. Many former commercial farms are being sold to lifestyle-oriented landowners who may not actively engage in food production activities, resulting in the loss of productive land and raising concerns about Australia’s long-term food security.

To address these challenges, Australia has implemented several initiatives to support private landowners in sustainable land stewardship. The state-run Land for Wildlife program supports landowners in conserving wildlife habitats through voluntary ecological assessments and ongoing support such as workshops, field observations, and peer networks [76]. Participants are encouraged to integrate conservation with agricultural or tourism activities, contributing to broader regional biodiversity goals across diverse ecosystems, including forests, wetlands, and other rural landscapes. Additional mechanisms, such as Conservation Covenants and tax incentives administered through organisations like Trust for Nature, also aim to promote long-term conservation on private land.

In European countries such as the UK, agricultural and rural development policies have traditionally focused on conventional commercial farming, offering limited support for lifestyle-oriented smallholdings. Similarly, Zasada [40] notes that the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and its Rural Development Programs (RDPs) often exclude peri-urban farms due to restrictions on land size and tenure. Smallholders often engage in activities shaped by ethical, ecological, and self-sufficiency values, which complicate conventional classifications and governance frameworks [77]. A notable feature of UK smallholdings is their engagement in animal husbandry and biosecurity. Holloway [78] suggests developing an “ethical identity” agricultural support system and employing relational, context-specific practices rooted in care and local knowledge to contribute to more resilient and sustainable farming systems.

Both Zasada [40] and Sutherland et al. [57] suggest that more adaptive policy approaches are needed, including regionally targeted agricultural and rural development schemes specifically adapted to peri-urban conditions, and spatial planning tools such as Green Belts (UK), SCoT (France), and the Finger Plan (Denmark), to indirectly support multifunctional land use and protect semi-agricultural and semi-residential use at the urban fringe.

In the U.S., hobby farms (LBs) have a long history dating back to the Homestead Act of 1862 and continue to balance lifestyle aspirations with agricultural productivity in rural areas [13]. Their function has evolved with industrialisation and urban sprawl. Ninety-one percent of U.S. farms are small, produce only 23% of total output, and rely heavily on off-farm external income [79]. Concentrated in peri-urban areas, the growth of hobby farms in the USA also leads to land fragmentation, rising property prices, and limiting commercial farm expansion. In Oregon’s Willamette Valley, small farms grew by 42.3% between 1978 and 1982, with farmland prices rising from USD 1700 to over USD 2600 per acre [20]. Layton [19], drawing on previous studies, links this trend to land subdivisions and changing ownership patterns, which may reduce long-term agricultural productivity. Environmental concerns such as runoff, water nutrient pollution, and erosion are also associated with those small farms.

The U.S. support for hobby and small-scale farms is evident in flexible zoning policies and tax incentives designed to encourage land ownership and retention [13]. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) also provides financial assistance, such as Farm Ownership and Operating Loans, as well as conservation programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), which promote practices that enhance productivity while protecting natural resources. Small farms collectively manage over half of U.S. farmland and account for 82% of land enrolled in conservation initiatives such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and Wetlands Reserve Program (WRP) [79]. As urbanisation has intensified, farmland preservation policies have played a role in slowing sprawl. However, their success requires effective monitoring to ensure that hobby farming does not compromise agricultural productivity [20]. In this context, sustainable land management and well-targeted incentives remain critical to supporting small farms and integrating them into resilient food systems.

NZ’s LBs share similar driving factors and challenges to those of Australia and the U.S., particularly in land fragmentation and biodiversity loss. However, NZ lacks tailored LB-specific policies and initiatives. While instruments like the Farm Environment Plans [69] and QEII National Trust support [80] land stewardship and biodiversity protection, they often rely on covenants with participation thresholds. In contrast, Australia’s Land for Wildlife program provides a more inclusive, flexible, and voluntary way of engaging private landowner communities and knowledge sharing, which could better attract LB owners. Meanwhile, the U.S. financial incentives and targeted conservation schemes also serve as valuable references. Notably, unlike other countries, NZ LBs have occupied a large proportion of its HPL; therefore, international experience can be a good reference, but it is still necessary to address more context-specific solutions that are more NZ-grounded.

5. Discussion

This review has summarised insights from the existing literature on resource use patterns, land management practices, food production, and biodiversity conservation of LBs. While the positive and negative environmental influences have been identified, the overall sustainability levels of LBs are still unknown.

Studies in NZ and Australia have consistently shown that while LB owners often demonstrate strong environmental awareness, this does not always translate into practical, sustainable land management. Barriers include limited knowledge, time, financial resources, physical ability, and a lack of tailored policy support, resulting in minimal engagement in resource management activities and programs [7,10,36,62,72,74,81]. To bridge the gap between awareness and action, broader engagement must be supported by enabling institutional conditions. Lawrence and McManus [51] argue that awareness raising and environmental education alone are not enough to drive systemic change. They emphasise the need for structural interventions, including technical guidance, financial mechanisms, and regulatory planning tools such as subsidies for wastewater management, rainwater harvesting systems, and wetland protection policies. Standard financial incentives are also inadequate; instead, due to the heterogeneity of LBs, more effective approaches include customised education, tailored policy support, and collaboration between policymakers, practitioners, and small-scale landowners [7,36,62,81]. Furthermore, environmental stewardship schemes such as QEII National Trust in NZ and Australia’s Land for Wildlife program can help connect private landowners with conservation goals. These initiatives enhance local habitats and support ecosystem services, such as water purification, flood regulation, and food production for urban and rural communities [7,22,43].

LBs can support diverse, small-scale food production through edible gardens, orchards, and livestock keeping, which contributes to self-sufficiency, local food supply, and reduced GHG emissions associated with long-distance food transport [15]. They should therefore be viewed as having a diverse set of land uses with variable implications that at least partly depend on the owners’ practices and priorities. However, there is currently no systematic framework to differentiate the diverse environmental performances of LBs. Cook and Fairweather [10] found that around 40% of respondents across lifestyle and part- and full-time farming categories identified their primary land use as LBs, suggesting limited differentiation between LBs and farming categories. They argue that this reflects shortcomings in current classification methods rather than true homogeneity and call for more refined frameworks that better capture smallholders’ production activities and income sources. Given LBs’ high variability, future research should move beyond broad typologies and develop more nuanced classifications based on factors like block size, land use intensity, owner motivations, and management strategies, to support more accurate sustainability assessments across diverse LB contexts.

To support interlinked priorities of lifestyle amenity, productivity, and sustainability, studies should assess key factors such as water consumption, food production and livestock grazing, energy use and carbon emissions, and biodiversity conservation, as well as identify how different land management approaches shape ecological outcomes and long-term land viability [43,50,51]. In parallel, research should explore how different management methods among LB owners influence ecosystem services, such as soil health, water regulation, pest control, and habitat connectivity. This requires investigating how different land management practices, such as diversified cropping, mixed livestock–forestry systems, ecological restoration, or small-scale agroecology, can optimise the use of HPL while maintaining lifestyle aspirations. Key areas of inquiry include identifying which combinations of land use activities (such as edible gardening, riparian planting, rotational grazing, and biodiversity corridors) most effectively balance environmental sustainability, land productivity, and lifestyle amenity values. This will require assessment of the trade-offs between intensification and sustainability on different block sizes and developing typologies of LB management strategies linked to measurable ecological, productive, and lifestyle outcomes. This can be supported through the development of operational models of LBs that address these potentially competing priorities, while also accounting for biophysical land capacities and local planning frameworks.

International experiences also reveal that, alongside regulatory restrictions, effective sustainability strategies for LBs include voluntary conservation programs, incentive-based programs, technical and advisory support, and stronger community engagement mechanisms. Initiatives such as Australia’s Land for Wildlife and the U.S. farm conservation demonstrate the importance of supporting small landholders through flexible, incentive-based approaches. Compared to these models, NZ’s current framework remains predominantly regulatory, with emerging but still limited voluntary and incentive-based structures. To strengthen the contribution of LBs to biodiversity conservation and climate resilience, future efforts should focus on integrating them into broader environmental strategies through stewardship programs, tailored incentives, and regional ecological networks.

Complementing program-level initiatives, broader institutional integration of LBs into national environmental governance remains limited. For example, Sise [58] highlights the need to account for LB-related emissions in national GHG emission inventories. Polyakov et al. [22] and Francis [82] both note that traditional natural resource management programs often exclude lifestyle landholders, focusing instead on commercial farmers. To address this gap, planning interventions should explicitly incorporate LBs into sustainable development strategies for peri-urban areas and land management frameworks. Understanding how LBs fit into broader land use planning and climate adaptation policies is crucial for comprehensive environmental governance. Additionally, exploring models of commercial cooperation among LB owners—as community clusters or cooperative networks—could help optimise the use of HPL while balancing environmental and economic sustainability objectives. While these strategies provide useful direction at a conceptual and policy level, their success will ultimately depend on effective implementation. Therefore, more comprehensive case studies, targeted guidance, and technical support are needed to bridge the gap between environmental awareness and sustained, practical action.

In terms of resource consumption and management, although research on water management and biodiversity conservation among LBs has increased, there is still a lack of detailed studies on energy use and transportation patterns. Given that energy consumption and mobility behaviours on LBs differ significantly from urban households due to larger property sizes, off-grid energy reliance, and greater car dependence, future studies should prioritise investigating energy flows, hotspots of consumption, and opportunities for improving efficiency and reducing emissions. Understanding these dynamics is essential for building a comprehensive picture of the environmental implications of LBs.

6. Conclusions

LBs offer both challenges and opportunities for environmental sustainability in peri-urban New Zealand. While their expansion contributes to land fragmentation, resource consumption, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions, many LB owners demonstrate strong environmental awareness and adopt sustainable land use practices such as agroforestry, permaculture, and renewable energy systems. Their non-commercial motivations allow diverse, regenerative land management approaches that can enhance ecosystem services and reduce environmental impacts. However, inefficient land management and other environmental impacts related to small-scale farming and recreational activities require greater attention. Furthermore, integrating management of LBs into environmental policy frameworks—through targeted incentives, carbon credit programs, and cooperative sustainability initiatives—could help to align LB owners’ lifestyle aspirations with regional and national environmental and food security goals. Future research should therefore investigate how this can be achieved through (a) supporting LB owners to change their practices to enhance environmental outcomes, and (b) integrating management of LBs into regional and national environmental policy.

Limitations and Future Research

The systematic review used Google Scholar and Scopus databases, and other databases, such as Web of Science, were not included. The keyword selection was primarily environment-focused and did not fully incorporate the broader social or economic viewpoint of LBs. This review mainly focuses on LBs in NZ and a few other high-income countries (e.g., Australia, the US, Canada, the UK) and does not include insights from emerging economies. However, countries like China, Japan, and India are also experiencing rapid peri-urban change and the rise of non-commercial or mixed land uses similar to LBs. While these contexts differ, they offer valuable perspectives on land fragmentation, food security, and rural–urban land governance. Future research should broaden its geographic scope to include these diverse cases and explore both local and transferable strategies for sustainable land management.

To better understand the overall sustainability of LBs, more detailed data on resource flows and both on-block and off-block activities and practices need to be collected to identify key environmental hotspots and develop more targeted assessment strategies for LB management. While improving the sustainability level, future research and planning policies should also focus on maintaining land productivity and supporting lifestyle amenity values of already subdivided land, particularly existing LBs. Additionally, attention should be paid to recent changes affecting LBs, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic and the publication of the NPS-HPL in 2022. The pandemic restrictions and increased remote work opportunities may have intensified interest in rural living [7], as individuals spend less time commuting and seek lifestyles that support teleworking, potentially increasing the demand for LBs. In contrast, the NPS-HPL has introduced stricter controls on land subdivision to protect NZ’s HPL, which may constrain LB development. These contrasting influences have not yet been systematically analysed and underscore the importance of investigating the long-term environmental, social, economic, and policy implications of LBs.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the research. H.X. conceptualized the main idea of the study and collected and analysed the literature. H.X. and D.P. designed the structure of the paper. H.X., D.P., S.J.M., and D.H. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. D.P., S.J.M., and D.H. supervised the final paper content and edited the writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Material is available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This appendix presents the final list of sources included in the systematic review (Table A1), following the screening and selection process described in the methodology. It includes academic publications as well as New Zealand government reports and policy documents. Each source is categorized by author, year, country, and key thematic focus to illustrate the breadth of literature informing this study.

Table A1.

Summary of included academic and policy documents in the systematic review.

Table A1.

Summary of included academic and policy documents in the systematic review.

| Author | Year | Country | Key Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Publications | |||

| Layton [19] | 1980 | Canada | Hobby farm; Rural–urban fringe Land fragmentation |

| Meister & Stewart [83] | 1980 | New Zealand | Smallholdings; Taranaki |

| Daniels [13] | 1986 | United States | Hobby farming; Rural development Commercial agriculture |