Abstract

Tourism learning resources refer to tourism attractions that carry learning content or stimulate learning behaviors for tourists, thereby determining the quality and effectiveness of tourists’ learning experiences. Actively developing tourism learning resources and manifesting tourism learning functions serves as an innovative practical path for cultivating new quality productivity in tourism and bears the contemporary mission of constructing a national lifelong learning system in the context of Chinese-style modernization. However, at the present stage, Chinese tourists, tourism enterprises, and government functional departments still lack a clear and systematic understanding of the connotations and characteristics of tourism learning resources. This knowledge gap restricts the depth and breadth of resource development. To address the identified gaps, this study begins by exploring the relationship between tourism and learning. Through a systematic literature review, it aims to develop a conceptual framework for tourism learning resources to promote lifelong learning and support sustainable tourism development. Taking this framework as a tool, this paper first explains the connotation and characteristics of tourism learning resources; secondly, classifies them into knowledge popularization, natural observation, skill experience, inspirational development, and cultural recreation types; thirdly, identifies their functional manifestations as acquiring experience, knowledge, skills, and wisdom; and finally, proposes development strategies for tourism learning resources. The most critical strategies identified are (1) enhancing tourism learning literacy, (2) optimizing learning-oriented products, and (3) constructing regionally integrated learning destinations.

1. Introduction

In the paradigm of a “learning society,” tourism transcends traditional leisure by functioning as a multifaceted “learning scenario” [1] that facilitates knowledge acquisition, skill development, and cultural internalization through experiential, interactive, and reflective processes [2]. The Chinese Domestic Tourism Enhancement Plan (2023–2025), issued by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, emphasizes promoting tourism as an important learning and growth method [3]. Unlike conventional education, which is often structured and institution-bound, tourism enables ubiquitous learning—encompassing formal, non-formal, and informal modalities—by embedding educational opportunities within authentic, immersive environments. For instance, tourism learning resources (TLRs), such as heritage sites, museums, or ecotourism destinations, provide spatial and cultural contexts where tourists engage in cognitive, affective, and behavioral learning outcomes. TLRs are the spatial carriers for tourists’ learning activities. Unlike the immutability of traditional tourism resources, tourism learning resources can, driven by market demand incentives and integration with regional functions, industrial foundations, and cultural heritage, create new learning-oriented tourism formats such as museum tourism, research travel, and summer camp study tours. The creation of these new formats promotes the value chain extension of backpacking tourism, wildlife tourism, ecotourism, scientific tourism, and heritage tourism, satisfying tourists’ needs for both relaxation and learning while providing strong support for advocating and creating lifelong learning concepts and practical scenarios [4,5,6].

However, the development of TLRs is hindered by significant research and practical gaps. Academically, studies on TLRs lack a unified theoretical framework to define their scope, characteristics, and operational mechanisms, resulting in fragmented insights that fail to address industry needs. Practically, the relationship between tourism and lifelong learning remains underexplored, particularly in how TLRs can systematically facilitate diverse learning outcomes (e.g., cognitive, affective, and behavioral) across varied tourism contexts. This dual gap limits the ability to design innovative tourism formats that effectively integrate education and experiential learning, constraining alignment with China’s strategic goals of building an “educational power” and a “tourism power.” The study addresses these challenges by (1) systematically defining the theoretical connotations and characteristics of TLRs, (2) proposing a conceptual framework for TLRs and integration to bridge tourism and lifelong learning, and (3) identifying operational strategies to cultivate new tourism formats that advance both lifelong learning and high-quality tourism growth.

To address the above research gaps, a review is employed to systematically clarify the concept of TLRs, which follows the framework of “conceptual deconstruction–typology construction–functional analysis–practical strategies” to develop a systematic analytical framework. By bridging these theoretical and practical gaps, this research makes original contributions, providing a solid foundation for aligning tourism development with national strategic goals and promoting sustainable industry innovation.

2. Materials and Methods

The objective of this study was to explore the research landscape related to the intersection of travel/tourism and education/study/learning. A systematic approach was employed to identify and select relevant literature. Searches were carried out using a variety of electronic databases, including EBSCO, ScienceDirect (Elsevier), and ISI Web of Knowledge.

Specifically, a deductive approach was adopted to gather evidence. The process began with using the combined keyword “Travel/Tourism + Education/Study/Learning” to conduct a comprehensive search of available journal articles and monographs within the selected databases.

The literature search process relied on the precise keyword combination to ensure coverage of relevant research. As is common in the literature retrieval, the keyword served as the core to connect and filter the literature. After the initial search, screening was performed through abstracts and research findings. Publications that did not align with the “Travel/Tourism + Education/Study/Learning” theme were excluded step-by-step. Eventually, 76 research outputs were selected as the research objects.

The inclusion criteria for the literature in this study were as follows: (1) English-language publications, (2) journal articles and monographs retrieved from the designated databases, (3) publications that clearly focused on the intersection of travel/tourism and education/study/learning, and (4) research outputs with accessible abstracts and findings for effective screening.

The findings of this literature selection process were used to form the basis for subsequent research analysis, laying a foundation for in-depth exploration of the research field.

3. Results

3.1. Connotation of TLRs

3.1.1. Definition of TLRs

TLRs refer to tourism attractions that carry learning content or stimulate learning behaviors for tourists. This definition integrates three core dimensions: spatial carriers (physical venues like museums, digital platforms such as AR tour apps, or interpersonal interactions with local hosts), learning facilitation mechanisms (task-based challenges, reflective tools, or collaborative activities), and cognitive outcomes (knowledge acquisition, skill mastery, or value formation).

The definition of TLRs extends and refines related concepts like educational tourism and study tours, which have been explored in prior research but remain limited in scope and theoretical integration. Educational tourism refers to travel primarily motivated by learning, such as university study-abroad programs or professional training tours, often targeting specific groups like students or professionals. Study tours, particularly prominent in the Chinese context, involve structured, curriculum-based travel experiences, such as school-organized visits to historical sites, designed to achieve predefined educational goals. While these concepts recognize tourism’s educational potential, they are constrained by their focus on intentional, structured learning and niche markets, often overlooking the informal, ubiquitous learning opportunities embedded in mainstream tourism activities. TLRs address these gaps by encompassing both intentional and incidental learning across diverse tourism contexts, catering to a broader range of tourists—from casual visitors to dedicated learners—and integrating cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes, including the reflective dimension of wisdom, which is rarely addressed in prior frameworks.

3.1.2. Theoretical Foundations of TLRs

Tourism as a form of learning has attracted attention from academic circles [7]. Tourism, as an interdisciplinary learning paradigm, is reconstructing the informal learning value in the lifelong education system through a three-dimensional path of knowledge acquisition, skill development, and cultural experience. Research on tourism learning originated early in the field of education, primarily examining the structured learning pattern and outcome in study tourism activities from the perspective of education [8]. With the increasing demand for lifelong learning, the ubiquitous educational value of tourism has been continuously recognized and explored. As an informal learning method for cultural capital accumulation, tourism is growing in importance. Disciplines such as management, sociology, anthropology, and geography have conducted related research from different perspectives, focusing on knowledge-based learning tourism (e.g., study tours, camp education, museum visits), skill-based learning tourism (e.g., scuba diving, skiing), and experience-based learning tourism (e.g., cultural experiences, ecological adventures, rural life experiences) [9,10,11,12]. Based on theories such as free-choice learning theory, transformative learning theory, and liminality theory, these studies introduce concepts of constructivist learning and situational learning, emphasizing the process of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral changes in tourists under the dual influence of subjective motivation and environmental guidance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Theories of learning in tourism activities.

The interplay between tourism activities and learning is illuminated by a range of complementary theories, including free-choice learning, transformative learning, liminality, constructivist learning, and situational learning, which collectively elucidate how tourism fosters cognitive, emotional, and behavioral growth. Free-choice learning theory posits that tourists, driven by intrinsic motivation, actively pursue knowledge and skills in unstructured, voluntary settings such as museums or heritage sites, where personal interests guide the learning process. This aligns with constructivist learning theory, which emphasizes that tourists construct knowledge through experiential interactions with tourism environments, integrating new information with prior understanding. Situational learning theory further contextualizes this process, highlighting how specific tourism settings—such as cultural festivals or ecotourism destinations—provide situated cues that shape learning outcomes through environmental guidance and social interactions. Transformative learning theory extends these ideas, explaining how tourism experiences, often involving profound emotional and cognitive shifts, catalyze long-term personal growth and value-level changes, such as enhanced cultural awareness or self-identity. Liminality theory complements this framework by viewing tourism as a transitional space where tourists, temporarily detached from everyday norms, engage in reflective and transformative experiences that foster self-discovery and learning. Together, these theories reveal the constituent elements and generative mechanisms of learning in diverse tourism activities, from heritage tourism to research travel, by illustrating how subjective motivations (e.g., curiosity, personal goals) and environmental factors (e.g., site-specific stimuli, cultural narratives) converge to create meaningful learning experiences. However, despite their critical role in tourism industry development, TLRs lack a systematically integrated analytical framework. Current theoretical explorations are fragmented, limiting the ability to fully understand and operationalize TLRs to support innovative tourism formats and lifelong learning objectives.

These studies introduce the concept of transformative learning to highlight tourists’ post-trip growth and development at the value level. They reveal the constituent elements and generative mechanisms of learning experiences in different forms of tourism phenomena and activities, providing valuable insights into why and how tourism activities can offer learning experiences and promote self-growth for tourists. Given that they serve as the foundation and critical carrier for tourism industry development, the theoretical development of tourism learning resources remains in the exploratory stage, with no systematically integrated analytical framework established yet.

Social cognitive theory, proposed by social cognitive scientist Bandura, expounds the triadic dialectical relationship among “subject-behavior-environment,” emphasizing that “behavior” itself is deeply influenced by “subject” and “environment.” [13]. It provides a comprehensive perspective and analytical framework for analyzing the relationship between tourism and learning. Based on the “subject-behavior-environment” analytical framework, tourism learning resources, as a link connecting the subject to the environment, refer to tourism attractions that carry learning content or stimulate learning behaviors for tourists with learning agency. Their value realization depends on the synergistic interaction and dynamic adaptation between the subject, behavior, and environment. That is, tourism learning resources construct a value realization path that dynamically adapts tourists’ cognitive development and tourism experience through the tripartite interaction mechanism of ‘subject behavior environment’.

The subject of tourism learning, in a narrow sense, refers to tourists with learning agency [14]. In a broad sense, it may also include tourism industry employees, tour guides, local residents, and travel companions who can interact in tourism practices [15]. From the perspective of general and special relationships, tourists’ learning agency encompasses both general human subjectivity and the particularity derived from their identity as tourists. This agency is characterized by the characteristics that distinguish tourists as learning subjects from formal learning when tourists experience non-habitual environments or understand authentic worlds during tourism [16]. These characteristics include independently choosing learning content, actively reflecting on the learning process, generating experiential knowledge, and engaging in mutual learning with a “seeking common ground while reserving differences” attitude.

Tourism learning behavior is a composite cognitive and behavioral phenomenon. It emerges from the multidimensional interaction between tourists and tourism environments during travel decision-making and the tourism process [17]. This behavior encompasses explicit reactions (e.g., behavioral manners, skill acquisition) and implicit cognitive reconstruction (e.g., emotional attitudes, thinking paradigms), demonstrating dynamic interactions across three sequential stages: During the pre-trip stage, tourists leverage memory reserves to screen information, verify knowledge, and plan itineraries. Key learning methods include autonomous learning, online research, and communicative learning. For example, travelers often use review platforms to validate destination authenticity before departure. For the during-trip stage, embodied learning drives sensory engagement with real-world scenarios. Tourists integrate receptive learning (e.g., guided tours) and gamified learning (e.g., scavenger hunts) to enhance on-site comprehension [18]. This stage highlights the interplay between physical experience and cognitive absorption. Post-trip reflection relies on deep learning and transformative learning. Tourists synthesize experiences through writing or social media sharing, facilitating knowledge recreation and social dissemination. Cognitive iteration across stages forms an organic cycle, distinguishing tourism learning from formal educational processes.

The tourism learning environment, an unconventional learning context, refers to tangible physical and intangible virtual spaces created and centered on tourists. Specifically, these spaces integrate recognizable elements like travel guide platforms, landscapes, and local communities through digital and physical carriers [19]. This construction occurs during pre-, during-, and post-trip stages, particularly when tourists encounter cognitive ambiguity or minimal physical interaction with their surroundings. As the spatial carrier for tourism learning resources, this environment shapes how resources are presented and experienced. For instance, natural landscapes in national parks require tourists to engage with physical environments for perception, while cultural narratives on platforms like TripAdvisor rely on virtual spaces for dissemination. Tourism learning resources are thus formed by screening and optimizing traditional tourism assets. This process transforms latent educational elements into usable content, endows environments with pedagogical functions, and establishes them as the core value of tourism learning ecosystems.

3.1.3. Intrinsic Characteristics of TLRs

Tourism learning resources combine the recreational appeal of tourism activities with the educational inspiration of educational resources, thereby representing a special type of resource that embodies rich travel experiences while effectively promoting learners’ all-round development. Through the dual attributes of integrating education with tourism, tourism learning resources have constructed a distinctive resource system that integrates experiential value and developmental functions. Its multidimensional characteristics provide a theoretical support for the integrated development of tourism education. Drawing on educational resource typology, this section analyzes the intrinsic characteristics of tourism learning resources from the perspectives of value, form, and scope.

From the perspectives of value, tourism learning resources emphasize their attractiveness to tourists and learning value. As the core of tourism resources, attractiveness to tourists represents the essential attribute and core value of tourism learning resources. According to Rogers’ theory of free learning, learning is ubiquitous, autonomous, and practical, emphasizing that individuals spontaneously engage in learning behaviors through interaction with their environment [20]. This type of learning is permeative, capable of infiltrating tourists’ daily lives and ways of thinking. During tourism activities, tourists immerse themselves in non-habitual life scenarios, such as natural landscapes with exotic charm, time-honored cultural heritage, and unique regional customs [21]. The uncertainty and unknown elements in non-habitual environments drive tourists to actively seek information, triggering strong curiosity and a desire to explore, and stimulating individuals’ intrinsic motivation for in-depth inquiry and continuous learning. With their unique attractiveness, ubiquity, autonomy, and practicality, tourism learning resources provide tourists with an open, contextualized, learning-oriented field, which significantly awakens and strengthens individuals’ intellectual curiosity.

From a morphological perspective, tourism learning resources have both subjective and objective attributes, which are both objectively existing entities and products of tourists’ subjective construction [22], creating highly personalized characteristics of the tourism learning experience. On the one hand, tourism learning resources are objective entities independent of individual consciousness, attracting tourists through their unique forms, colors, stories, etc., and providing rich materials and backgrounds for learning [23]. On the other hand, according to Vygotsky’s theory, knowledge is not simply transmitted to individuals from the external world but is actively constructed by individuals through social interaction, cultural participation, and practical activities during their engagement with the environment. Tourism learning resources possess inherent constructiveness, situationality, and sociality [24]. Influenced by tourists’ own interests, experiences, values, etc., they are endowed with personalized characteristics of deconstruction and meaning-making through the interaction between subjects and objects. The dual attributes of objective existence and subjective construction of tourism learning resources make tourism learning a highly personalized process, allowing each tourist to acquire different knowledge and experiences according to their own needs and preferences [25].

From a categorical perspective, tourism learning resources exhibit geographical extensibility and spatial interactivity. Geographical extensibility means that tourism learning resources are not confined to a specific location or region but are widely distributed across different geographic spaces, encompassing natural landscapes, historical cultures, social customs, and other aspects [26]. This extensibility provides tourists with diverse learning experiences, enabling them to explore, learn, and grow in different regional environments. Meanwhile, spatial interactivity emphasizes the interactive relationship between tourism learning resources and tourists. During tourism, people expand their knowledge and horizons, which not only helps improve physical and mental health, restore productivity, and enhance creativity and aesthetic ability, but also enables deep interaction with the objective environment through communication and observation of cross-regional, cross-cultural, and cross-class groups [27]. Through this process, tourists achieve deeper self-awareness, a richer emotional world, and the reconstruction of values.

3.2. Types and Characteristics of TLRs

The classification system of tourism learning resources consists of multiple concepts and relationships, where concepts form “categories” and relationships establish the framework. Accurately grasping concepts is the foundation for constructing a classification system, and ontology—the science of studying “existence”—provides theoretical support for understanding the concept of tourism learning resources. Ontology posits that concepts, instances, and relationships are the three core elements of an ontology: instances are the real-world manifestations of concepts (each instance belongs to at least one concept), while relationships exist between instances, between concepts, and between instances and concepts. Based on this, starting from core concepts, we can mine and integrate a priori knowledge to explore and construct a new knowledge system for the classification framework, achieving a scientific construction of the classification framework for tourism learning resources.

Specifically: (1) The conceptual structure model is a process of acquiring a priori knowledge through in-depth analysis of core concepts and meticulous combing of relationships between concepts. Guided by ontology, the model specifically involves two core steps: first, extracting type concepts by drawing core concepts with classification value from extensive knowledge sources to establish an a priori foundation for classification; second, identifying relationships between concepts through analyzing and organizing their internal connections to reveal the conceptual network. This dual-step approach ensures systematic integration of theoretical foundations and practical classification needs. (2) The knowledge structure model constructs hierarchical and associative relationships between type concepts by integrating the a priori classification knowledge and conceptual relationship knowledge obtained from the conceptual structure model with advanced information classification methods. This process not only provides a specific and feasible path for constructing the classification framework of tourism learning resources but also ensures the scientific validity and practical applicability of the framework.

At present, there is no unified classification method for tourism learning resources. The current classification, investigation, and evaluation of tourism resources is a relatively mature and widely used classification system. Based on the actual situation of tourism resources and development in China, and combined with the basic connotation of learning content in pedagogy, Chinese tourism learning resources can be divided into 5 main categories, 11 subcategories, and 50 basic types, including knowledge popularization, natural sightseeing, experience investigation, inspirational development, and cultural recreation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification system of tourism learning resources in China.

3.2.1. Knowledge Popularization Type of TLRs

This type of tourism learning resource refers to those that can popularize scientific knowledge and historical and cultural knowledge to tourists. Main carriers include museums, science and technology museums, theme exhibitions, zoos, botanical gardens, historical and cultural heritage sites, industrial projects, and scientific research venues. Through various means such as physical displays, interactive experiences, and guided explanations, learners acquire knowledge and enhance their literacy during tourism [28]. These resources cover multiple fields, including natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities [29], while integrating multiple elements such as tradition and modernity, theory and practice, and knowledge and fun, thus constructing a comprehensive and multi-layered knowledge learning system for learners [30].

Knowledge popularization-type learning resources exhibit distinct characteristics. First is intuitiveness and vividness: these resources translate abstract scientific and historical knowledge into tangible experiences through physical exhibits and interactive displays, enabling learners to observe and engage directly, thereby enhancing long-term memory retention [31,32]. Second, they emphasize entertainment and interactivity, incorporating gamified activities and collaborative tasks to foster knowledge acquisition in relaxed settings [33]. Such interactions not only stimulate interest but also develop teamwork skills through peer collaboration. Third, accessibility is a key attribute: these resources are open to all audiences, irrespective of age or educational background, leveraging tourism’s mass appeal to disseminate scientific literacy broadly [34]. For example, science museums often design programs for both children and adults, ensuring inclusive learning opportunities. Finally, innovation drives their evolution: integrating advanced technologies like virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), these resources offer immersive experiences that align with cutting-edge trends in AI and digital education, providing learners with timely insights into emerging scientific frontiers [35,36,37].

3.2.2. Natural Sightseeing Type of TLRs

Natural sightseeing-type tourism learning resources refer to those taking natural landscapes as the primary carrier, aiming to expand visitors’ knowledge, enhance their literacy, and strengthen environmental awareness through organized on-site observation, experience, and learning. Widely distributed across natural ecosystems such as mountains, rivers, lakes, oceans, grasslands, deserts, forests, and wetlands [38], these resources attract countless visitors with their unique natural scenery, rich biodiversity, and profound cultural heritage [39,40]. Such resources are characterized by the following:

Natural sightseeing tourism learning resources are renowned for their rich variety of natural landscapes [41]. From majestic mountains to vast grasslands, and from rippling lakes to turbulent oceans, each natural scene captivates visitors with its unique charm. This diversity not only satisfies visitors’ pursuit of beauty but also provides extensive learning spaces for exploring geological structures, ecological systems, and climatic phenomena [42].

In the context of natural sightseeing resources, visitors can engage in hands-on ecological protection practices. Through outdoor activities like hiking, rock climbing, and camping, they not only observe natural ecosystems up close but also acquire knowledge and skills in ecological conservation through practical experience [43,44]. This experiential learning approach reinforces visitors’ environmental awareness and promotes harmonious coexistence between humans and nature [45].

Natural sightseeing resources are often closely integrated with scientific disciplines such as geology, ecology, and meteorology. During tours, visitors can understand the practical applications and significance of these sciences through guided explanations, science exhibition boards, and personal interactions [46]. This accessible educational model bridges theoretical knowledge with real-world observations, helping to improve visitors’ scientific literacy and cognitive abilities [47].

Engaging in tourism activities within natural environments significantly enhances visitors’ physical and mental well-being. Fresh air, scenic landscapes, and a tranquil atmosphere help alleviate stress, soothe emotions, and elevate quality of life [48]. Meanwhile, outdoor activities strengthen physical fitness, boost immunity, and foster holistic physical and mental healing [49].

3.2.3. Experiential Investigation Type of TLRs

This category of tourism learning resources refers to those utilizing farms, practice bases, summer camp sites, and team development bases as primary carriers. Through organized activities such as on-site investigations, hands-on experiences, and practical operations, these resources aim to achieve multiple educational objectives, including knowledge expansion, skill enhancement, emotional cultivation, and willpower training [50,51]. Emphasizing learners’ subjectivity and participation, they encourage learning through practice and growth through experience [52], thereby facilitating deep comprehension of knowledge and comprehensive improvement of skills [53]. Experiential investigation-type tourism learning resources are characterized by the following:

The core feature of experiential investigation tourism learning resources lies in their practicality. Learners directly grasp the essence of practice by engaging in farming activities, handicraft production, and team collaboration, transforming theoretical knowledge into practical operational capabilities [54]. This hands-on approach not only enhances the fun of learning but also improves its effectiveness, bridging the gap between academic knowledge and real-world application.

These resources often integrate knowledge education, skill training, emotional education, and willpower development [55]. During the experiential process, learners not only acquire practical knowledge and skills but also cultivate a teamwork spirit and problem-solving abilities and achieve overall enhancement of comprehensive qualities [56]. For instance, a farm-based learning program might combine agricultural science education with collaborative tasks to develop both technical proficiency and social competencies.

Experiential investigation tourism learning resources are typically situated in specific contexts, such as farm fields, summer camp sites, or development training grounds. These settings provide authentic learning backdrops, enabling learners to study and practice in simulated or real environments [57]. This situational immersion strengthens the sense of engagement and practical efficacy of learning, as learners apply knowledge in context-specific scenarios rather than abstract theoretical frameworks [58].

3.2.4. Inspirational Development Type of TLRs

This type of tourism learning resource primarily uses red education bases, university campuses, national defense education bases, and military camps as carriers. Through organized activities such as on-site visits, hands-on experiences, and interactive participation, these resources aim to cultivate learners’ patriotic sentiments, social responsibility, teamwork spirit, and tenacious willpower [59,60]. With their unique educational value and experiential nature, they have become an indispensable part of modern education systems, playing a significant role in promoting learners’ all-round development [61,62]. Inspirational development-type tourism learning resources exhibit the following characteristics:

The core characteristic of inspirational development tourism learning resources lies in their educational value. By enabling learners to participate in and experience firsthand, these resources transform abstract historical knowledge, moral concepts, and teamwork principles into concrete, perceptible practices, allowing learners to deepen their understanding and enhance their cognition through practice [63,64]. For example, visitors to red education bases may engage in reenactments of historical events to internalize revolutionary ideals [65].

To foster learners’ willpower and teamwork capabilities, these resources often design a series of challenging activities [66]. Examples include hiking through revolutionary routes in red education bases, military-style training in defense bases, and academic debates or team projects on university campuses. These activities require learners to maintain perseverance in the face of difficulties and overcome challenges through collective collaboration [67], thereby strengthening mental resilience and collaborative skills.

3.2.5. Cultural Recreation Type of TLRs

This type of tourism learning resource uses theme parks, entertainment film studios, and cultural festival events as carriers. By integrating cultural resources, designing recreational activities, and providing artistic performances, it offers learners multiple functions, including cultural learning, entertainment and leisure, and aesthetic experiences [68]. These resources emphasize learners’ subjectivity and participation [69], encouraging them to appreciate the charm of culture in a relaxed and joyful atmosphere, broaden their horizons, and enhance their aesthetic taste. The core concept lies in integrating education with tourism to achieve “learning through travel and traveling through learning,” allowing learners to gain intellectual nourishment and spiritual elevation while enjoying the pleasures of tourism. Cultural recreation-type tourism learning resources exhibit the following characteristics:

The core characteristic of cultural recreation tourism learning resources lies in their profound cultural heritage [70]. Whether the cultural theme zones in theme parks or the film and television works in entertainment studios, they embody rich cultural connotations and historical information. These cultural resources provide learners with broad learning spaces, enabling them to appreciate the charm of different cultures and experience cultural diversity and inclusivity while having fun.

These resources focus on learners’ entertainment experiences. Through highly interactive and fun activities such as amusement rides, performance viewing, and interactive games, they allow learners to engage with culture in a relaxed and pleasant atmosphere [71]. This entertainment-oriented design not only enhances the fun of learning but also boosts learners’ enthusiasm and participation.

The educational function of cultural recreation tourism learning resources is reflected in their edutainment capabilities. Through participating in various cultural activities, learners can imperceptibly be influenced by culture, expand their knowledge, and improve their aesthetic taste. Meanwhile, these resources often incorporate elements of history, culture, and folk customs to provide learners with rich historical knowledge and cultural insights.

3.3. Theoretical Analysis of the Functions of TLRs

According to Bandura’s social cognitive theory, tourism learning resources constitute the learning objects and cognitive environments for tourists during tourism activities, carrying the content of their learning. They play a fundamental role in the “subject-behavior-environment” system of tourist learning, being either inherent in or attached to the learning environment and representing an objective existence at a higher level [72]. Based on the connotation and structure of learning content, combined with the conditions for tourist learning behaviors, and according to the cognitive levels of learners (e.g., perceptual, intellectual, and rational), the functions of tourism learning resources can be summarized as acquiring experience, knowledge, skills, and wisdom [73]. Table 3 further illustrates how these functions are theoretically supported by different academic perspectives and exemplified in practical tourism learning scenarios.

Table 3.

TLRs’ multidimensional functions.

3.3.1. Tourists’ Acquisition of Experience

From a philosophical perspective, “experience” refers to the pursuit of the origin of the world. After the Renaissance, as a response to the “people-oriented” ideology, epistemology began to replace ontology as the mainstream. Berkeley (1709) divided sensations into touch and vision based on sensory perception, arguing that knowledge is a collection of various sensory impressions [74]. Hume (1889) further categorized impressions into simple touch and visual impressions and complex ideational impressions, positing that the arbitrary combination of simple impressions constitutes the starting point of knowledge [75]. Marx introduced dialectics, linking simple and complex impressions through human practice, scientifically asserting that human knowledge originates from practice and that experience is the product of practice.

Psychology defines “experience” as a process of subjective consciousness and environmental adaptation. Dewey viewed experience as the interactive process between the subject and the environment, categorizing it into direct experience (knowledge gained through the subject’s own practice) and indirect experience (knowledge acquired through observing other subjects). These two forms can be mutually transformed: when the content of knowledge matches the subject’s cognitive level, direct experience gained from individual practice expands into indirect experience; when the content exceeds this level, collective indirect experience is internalized into individual direct experience through practice. Through this iterative process, direct and indirect experiences together constitute human experience.

In the context of tourism, these philosophical and psychological perspectives on experience are directly relevant to how tourists engage with TLRs. Tourism activities, such as visiting heritage sites, participating in cultural festivals, or exploring natural landscapes, provide rich environments for both direct and indirect experiences. For instance, a tourist’s direct experience of engaging in a traditional craft workshop (practice-based learning) or hiking a geologically significant trail (sensory interaction) aligns with Dewey’s notion of direct experience, fostering immediate, personal connections with the environment. Conversely, observing a cultural performance or listening to a guided tour narrative constitutes indirect experience, allowing tourists to internalize collective knowledge. TLRs, as cognitive and spatial carriers, facilitate this experiential learning by offering structured yet flexible settings where sensory impressions (per Berkeley and Hume) and practical engagement (per Marx and Dewey) converge. These experiences contribute to tourists’ cognitive and emotional growth, enabling them to acquire not only factual knowledge but also cultural insights and personal meaning. By bridging philosophical and psychological understandings of experience with tourism contexts, TLRs support the broader objectives of lifelong learning and personal development, aligning with the transformative potential of tourism activities.

3.3.2. Tourists’ Knowledge Enhancement

Regarding “knowledge,” the Great Dictionary of Education defines it as a reflection of the essential attributes of things or their external relationships, namely organized information acquired through the interaction between a subject and its environment, manifested in the form of concepts and rules. Kant, synthesizing rationalism and empiricism, proposed that “knowledge” is the result of rational thinking based on sensory experience. Psychological pragmatist thinkers represented by James, Dewey, and Piaget argue that “knowledge” serves as a tool for human behavior, existing not in static and isolated forms but in dynamic and systematic ones, with its development occurring through continuous inquiry, problem-solving, and reflection in daily life [76]. Postmodernist trends of thought represented by Wittgenstein, Foucault, Lyotard, and Doll contend that “knowledge” is actively constructed through interactions between individuals and sociocultural contexts, characterized by uncertainty, plurality, and heterogeneity under different cultural value systems, following nonlinear development laws. For example, in education, knowledge can be categorized into declarative and procedural, explicit and tacit [77].

In the context of tourism, these philosophical, psychological, and postmodernist conceptions of knowledge are highly relevant to how tourists engage with TLRs. Tourism activities, such as guided tours, cultural immersion programs, or scientific expeditions, serve as dynamic environments where tourists acquire and construct knowledge through sensory, cognitive, and sociocultural interactions. For instance, Kant’s notion of knowledge as sensory-based rational thinking is evident when tourists interpret historical narratives at heritage sites, blending sensory stimuli (e.g., visual artifacts) with cognitive reflection. Dewey’s pragmatic view of knowledge as a tool for problem-solving manifests in activities like ecotourism, where tourists learn sustainable practices through hands-on engagement with environmental challenges. Postmodernist perspectives resonate in culturally diverse tourism settings, such as indigenous cultural festivals, where tourists encounter pluralistic knowledge systems that challenge their preconceptions and foster tacit, context-specific understanding. TLRs, as cognitive and spatial carriers, facilitate these processes by providing structured opportunities for both declarative knowledge (e.g., facts about a destination’s history) and procedural knowledge (e.g., skills learned in a cooking class). By enabling tourists to actively construct knowledge through inquiry, reflection, and sociocultural interaction, TLRs align with the nonlinear, heterogeneous nature of knowledge described by postmodernists, contributing to tourists’ intellectual growth and supporting the broader objectives of lifelong learning. Thus, the multifaceted nature of knowledge acquisition in tourism underscores the transformative potential of TLRs in fostering meaningful learning experiences across diverse contexts.

3.3.3. Tourists’ Acquisition of Skills

Regarding “skills,” the New Dictionary of Contemporary Western Psychology defines them as a systematic set of actions coherently integrated by an individual through practice or task completion, utilizing personal experience and knowledge. With the development of science and technology and the evolution of the times, human understanding of the connotation of “skills” has continuously deepened and expanded. From a philosophical perspective, skills are interpreted as the application of technology in productive activities [78]. Psychology views them as automated mental activities performed according to specific rules and procedures [79]. Economics emphasizes that “skills” refer to the potential of knowledge and experience necessary to complete a task, constituting a component of human capital, which can be divided into general and vocational types based on social division of labor [80]. Management science defines skills as the understanding or familiarity with specific management activities and the ability to coordinate organizations and control the whole [81]. In this context, grassroots positions primarily require technical capabilities, middle-level positions emphasize interpersonal skills, and senior positions demand conceptualization abilities. Pedagogy holds that “skills” are capabilities acquired through extensive practice, involving processes such as unordered trial, directional imitation, ordered connection, and assimilation refinement, which can be classified into perceptual, cognitive, and motor types [82].

In the context of tourism, these multifaceted conceptions of skills are directly applicable to how tourists engage with TLRs across diverse activities, such as cultural workshops, adventure tourism, or guided scientific expeditions. For instance, the philosophical view of skills as applied technology is evident when tourists learn traditional crafts (e.g., pottery) in cultural tourism settings, transforming raw materials into tangible products. Psychologically, the automation of mental activities manifests in adventure tourism, where tourists develop navigational skills through repeated practice in challenging environments. Economically, tourism fosters both general skills, such as cross-cultural communication during immersive travel, and vocational skills, like wildlife tracking in ecotourism, enhancing tourists’ human capital. From a management perspective, group-based tourism activities, such as team-building retreats, cultivate interpersonal skills (e.g., collaboration) and, at advanced levels, conceptualization skills (e.g., strategic planning in community-based tourism projects). Pedagogically, the staged process of skills acquisition is reflected in activities like cooking classes, where tourists progress from trial (initial attempts) to assimilation refinement (mastery of recipes), developing perceptual (tasting ingredients), cognitive (understanding culinary techniques), and motor (chopping, stirring) skills. TLRs, as structured cognitive and spatial carriers, facilitate these processes by providing environments that integrate practice, guidance, and reflection, enabling tourists to acquire transferable skills that enhance personal and professional growth. By aligning with lifelong learning objectives, the skills cultivated through TLRs underscore their transformative potential in tourism. Yet, the lack of a unified theoretical framework for skills development in tourism limits their systematic integration into innovative tourism formats, highlighting the need for further research to optimize TLRs’ role in fostering capability-building experiences.

3.3.4. Tourists’ Wisdom Enhancement

Wisdom refers to the process of self-improvement through practice, inner reflection, and transcending universal cognition, guiding human survival, production, and lifestyle. Compared with knowledge and skills, wisdom is more characterized by practicality, explorativeness, subjectivity, and value-leadenness. Unlike knowledge, which is primarily informational, wisdom integrates values and ethical considerations, enabling tourists to discern broader implications or form personal principles. The key distinction lies in their scope and depth: knowledge enhancement builds foundational understanding, while wisdom enhancement transforms this understanding into reflective, value-driven insights that guide behavior and decision-making.

In tourism, this manifests when visitors to red heritage sites use historical knowledge to reflect on contemporary social values, ecotourists derive wisdom about sustainable coexistence from ecological knowledge, or travelers to ethnic villages develop cross-cultural empathy through introspection. These examples show how tourism learning resources act as catalysts for transforming knowledge into wisdom, enabling tourists to bridge theoretical understanding and practical virtue in real-world contexts.

Based on tourism social practices, through various tourism practices such as sightseeing, traveling, and experiencing, tourists receive, process, generate, integrate, and apply information from diverse tourism resources to acquire experiences, new knowledge, and new skills, forming tourism learning behaviors that influence changes in individual cognition, capabilities, or behaviors, ultimately achieving individual wisdom upgrading. A deeper analysis reveals that the content of tourist learning includes direct and indirect tourism experiences, self-directed knowledge, experiential skills, and wisdom gradually developed through tourism practices. Among them, tourists’ “experience” serves as the foundation for knowledge and skill learning, “knowledge” is the core of wisdom enhancement, and “skills” act as the intermediary linking knowledge and wisdom. Meanwhile, experiences and wisdom exist in implicit forms, while knowledge and skills can be explicit, of which are the much-needed tourism learning functions for tourists in the new era. Actively developing and expanding the functions of tourism learning resources, empowering high-quality tourism development, and cultivating “tourist learning-oriented” tourism formats, new functions, and social learning models can provide decision-making foundations and theoretical references for formulating regional tourism development and learning society policies in the new era.

3.4. Development Strategies for TLRs

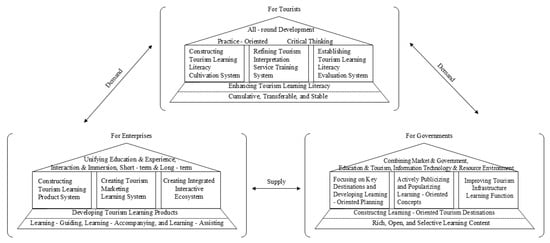

Based on the logical relationship of “subject-behavior-environment” in tourists’ learning behaviors, combined with tourism realities and social practices, and addressing the universality and generality of tourist learning, different strategies and models can be adopted for developing tourism learning resources from the perspectives of tourists, enterprises, and governments (Figure 1). These include enhancing tourism learning literacy, developing tourism learning products, and constructing learning-oriented tourism destinations so as to promote the rapid development of “tourist learning-oriented” new tourism formats and educational functions in China.

Figure 1.

Development strategies and models for tourism learning resources. (Source: the author).

3.4.1. Strategies for Enhancing Tourism Learning Literacy

Tourism learning literacy, defined as tourists’ ability to autonomously acquire knowledge, skills, and psychosocial competencies through experiential tourism activities, is pivotal to maximizing the educational potential of TLRs. The learning subjectivity of tourists encompasses both the general human subjectivity and the particularity inherent in their tourist identity. During tourism, as learning subjects, tourists exhibit characteristics distinct from formal learning when experiencing non-habitual environments or engaging with authentic worlds, including autonomous selection of learning content, active reflection on learning processes, creation of experiential knowledge, and a state of “seeking common ground while reserving differences” in mutual learning. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines the core competencies for 21st-century citizens as the ability to flexibly apply knowledge and skills and proactively deploy psychosocial resources to meet relatively complex needs in specific contexts, characterized by evident autonomy, cross-disciplinarity, and multifunctionality [83,84]. The learning subjectivity of tourists combines universality and particularity, and their autonomous construction characteristics in unconventional environments are in line with the core literacy requirements of the 21st century.

To promote the development of tourism learning resources, it is necessary to build an innovative system that integrates multiple elements and fields. Therefore, the development of tourism learning resources must comprehensively consider factors influencing learning behaviors such as tourists’ learning motivation, cognitive abilities, subject nature, and learning styles. To awaken tourists’ learning subjectivity, the following targeted strategies are proposed: First, develop personalized digital learning tools by deploying mobile applications or augmented reality (AR) platforms. These tools should enable tourists to customize learning experiences based on individual interests and cognitive preferences. For example, an AR-guided museum tour could offer interactive modules on art history or cultural symbolism, allowing tourists to select content that matches their motivations and fostering autonomous learning. Second, integrate reflective learning prompts into tourism activities. This includes post-experience journals or guided discussions led by interpretive guides at cultural sites, which encourage tourists to actively process and internalize experiences—thereby stimulating critical thinking and the creation of experiential knowledge. Third, adapt international “national credit” systems to implement learning outcome recognition mechanisms. This involves awarding digital badges or micro-credentials for skills gained through tourism (e.g., cultural competence, environmental literacy), which incentivizes sustained engagement and validates tourists’ learning efforts.

3.4.2. Strategies for Optimizing Tourism Learning Products

Tourism learning resources carry learning activities, content, and processes, playing a decisive role in shaping tourist learning behaviors and efficiency. Tourism learning products, derived from the development of these resources, serve as the most critical material carriers and foundational learning environments for forming tourists’ learning behaviors [85]. Unlike general tourism products, they can be understood as services provided by tourism operators to meet learning needs through effective utilization of tourism learning content. Alternatively, they represent various experiences that connect hosts and guests through tourism learning activities, stimulating pre-trip learning interest, in-trip learning inclination, and post-trip knowledge acquisition and sharing. Beyond general tourism consumption functions, these products are characterized by learning activities as the main thread, focusing on presenting diverse learning content through learning guidance, learning companionship, and learning support. Specifically, they guide tourists to freely select interesting learning content, subconsciously alleviate the tedium of learning through companionship, and help tourists gain direct learning experiences in authentic environments—thereby influencing the effectiveness and efficiency of tourism learning. This forms a product system centered on knowledge, experience, wisdom, or skills, encompassing in-depth mass tourism, niche tourism, cultural tourism, or study tourism [86]. Tourism enterprises must scientifically develop various tourism learning resources to create rich learning products and provide corresponding learning content and environments for tourists.

In fact, the development of TLRs faces significant constraints, including limited stakeholder collaboration, insufficient technological infrastructure, and tourists’ varying levels of learning motivation. To address these constraints, the following strategies outline how tourism enterprises can develop TLRs by leveraging available resources, adapting to limitations, and prioritizing tourists’ learning needs within authentic tourism contexts. First, under the constraint of limited stakeholder collaboration, co-designed micro-learning modules can be developed through small-scale partnerships with local educational providers or cultural organizations, rather than relying on large, resource-intensive collaborations. For instance, a heritage site could partner with a local museum to create short, interactive learning guides (e.g., audio tours or QR-code-based content) that highlight cultural narratives, enabling tourists to engage with TLRs autonomously even without extensive cross-sector coordination. Second, in the context of insufficient technological infrastructure, particularly in rural or underdeveloped destinations, low-tech, scalable TLR solutions can be prioritized, such as printed learning booklets or community-led interpretive sessions that deliver knowledge without requiring advanced digital tools. For example, ecotourism sites could offer guided nature walks with trained local hosts who share environmental insights, ensuring equitable access to learning content. Third, to address tourists’ varying levels of learning motivation, flexible, interest-driven learning pathways can be embedded within TLRs, allowing tourists to select activities based on their preferences, such as cultural workshops (e.g., cooking classes) or adventure-based tasks (e.g., navigation challenges). These pathways can incorporate motivational incentives, like digital badges for completing activities, to sustain engagement among less motivated tourists. Additionally, community-integrated TLRs can be developed by training local residents to serve as knowledge facilitators, leveraging their cultural expertise to create authentic experiences (e.g., storytelling or craft demonstrations) that compensate for limited external resources.

3.4.3. Strategies for Constructing Learning-Oriented Tourism Destinations

The development of tourism learning resources urgently needs to establish a government-led regional coordination mechanism, which can achieve the symbiotic development of educational value and industrial value through the dual wheel drive of element integration and functional integration and provide systematic support for the construction of a tourism education powerhouse. Currently, tourism learning resources and their functions have not attracted sufficient attention from tourists, enterprises, and governments. As tourist learning behaviors are directly influenced by factors such as learning subjects, resources, and environments, and indirectly affected by regional development policies, educational systems, tourism systems, and socioeconomic-technological development levels, regional integration has become critical for developing tourism learning resources [87]. The core of this integration lies in rational spatial organization: by organically integrating various tourism learning elements within a region, synergistic effects and complementary advantages can be achieved, thereby enhancing the quality and value of tourism learning resources. Governments play an irreplaceable leading role in regional integration. Through policy and financial support, strict regulation and organization, they can guide interactive regional integration, foster a harmonious and orderly tourism market environment, standardize the operational behaviors of tourism enterprises, protect tourists’ legitimate rights and interests, and improve the efficiency of tourism learning resource development [88,89]. Only governments can closely integrate the social education function of tourism with its industrial economic function, vigorously promote the universalization of tourist learning, construct a modern knowledge system for tourism learning, continuously enhance its social effects, and strive to advance the construction of a strong Chinese tourism education nation.

It is worth noting that the construction of learning-oriented tourism destinations faces several challenges, including fragmented governance structures, limited funding, low stakeholder awareness of TLRs’ educational value, and uneven regional development. To develop TLRs within these constraints, the following strategies are proposed. First, decentralized coordination hubs can address fragmented governance by establishing local task forces, comprising regional tourism boards, educational authorities, and community representatives, to oversee TLR integration without requiring centralized overhauls. For example, a rural region could create a hub to link local cultural sites with schools, offering low-cost study tours. Second, prioritized resource allocation can mitigate funding shortages by channeling limited budgets into high-impact TLRs, such as community-led heritage trails, which require minimal investment but deliver authentic learning experiences. Third, awareness-building initiatives can counter low stakeholder engagement by launching targeted campaigns through social media or educational networks to highlight TLRs’ lifelong learning benefits, encouraging tourist and enterprise participation. For instance, a campaign could promote ecotourism sites as platforms for environmental literacy.

4. Discussion

This study advances the understanding of TLRs by systematically defining their connotations, characteristics, and functional manifestations while proposing a novel analytical framework and development strategies to bridge theoretical and practical gaps in tourism learning. Through a systematic review, guided by the interplay between tourism and learning, several key insights emerge.

First, TLRs, as tourism attractions that carry learning content or stimulate learning behaviors for tourists, integrate spatial carriers, learning facilitation mechanisms, and cognitive outcomes. The definition of TLRs extends prior concepts like educational tourism and study tours, which focus on structured learning for niche groups, by encompassing both intentional and incidental learning across diverse tourism contexts for all tourists, integrating cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes, including reflective wisdom, thus addressing gaps in informal tourism learning and holistic frameworks.

Second, the classification of TLRs into five categories (knowledge popularization, natural sightseeing, experiential investigation, inspirational development, and cultural recreation) reveals their multidimensional potential to cater to tourists’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral needs, aligning with the principles of lifelong learning. Unlike earlier studies that often focused on singular tourism learning formats, such as museum-based education or adventure tourism skill development, this categorization provides a comprehensive framework that captures the diverse ways TLRs facilitate learning across varied spatial and cultural contexts. This holistic approach fills a critical gap by offering a unified typology that supports the design of inclusive, learner-centered tourism experiences.

Third, the application of the “subject-behavior-environment” analytical framework provides a foundation for understanding how TLRs facilitate learning through subjective motivation and environmental interaction. By positioning TLRs as the critical link between tourists’ agency (subject), their learning activities (behavior), and context-specific stimuli (environment), the framework extends the scope of social cognitive theory beyond traditional educational settings, addressing a gap in tourism research where comprehensive models for informal learning were lacking.

Despite being defined as spatial carriers, TLRs suffer from an underexplored spatial dimension in current research, limiting their theoretical and practical potential. Studies neglect spatial distribution characteristics, failing to analyze how TLRs’ geographic spread impacts accessibility and equity. The diversity of spatial types, such as museums or digital platforms, lacks examination of how they shape learning outcomes. Spatial density and connectivity, crucial for integrated learning ecosystems, are rarely addressed. Spatial scale, place identity, and socio-spatial dynamics are also overlooked, restricting insights into TLRs’ relational and cultural roles. These gaps hinder comprehensive frameworks, necessitating interdisciplinary, spatially informed research to unlock TLRs’ transformative capacity for lifelong learning and sustainable tourism.

Future studies should harness big data analytics to develop a comprehensive framework for identifying TLRs. Employing text mining and spatial analysis algorithms, studies can identify TLRs by extracting learning-related terms (e.g., “cognition,” “skill-building”) from millions of user reviews, categorize them into experience, knowledge, skills, and wisdom-based outcomes, and align them with standardized tourism resource typologies to construct a robust classification system. On this basis, analyze the spatial layout, spatial correlation, spatial agglomeration, etc., of tourism learning resources to deepen the understanding of the spatial attributes of TLRs.

5. Conclusions

This study makes significant contributions to the field of TLRs. By systematically exploring the relationship between tourism and learning, it defines the connotations and characteristics of TLRs, proposes a comprehensive classification, and applies the “subject–behavior–environment” framework to explain the learning facilitation mechanisms of TLRs.

The research reveals that TLRs are not only tourism attractions but also important carriers for promoting lifelong learning. They have the potential to meet the diverse learning needs of tourists in cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects. The proposed development strategies, including enhancing tourism learning literacy, optimizing learning-oriented products, and constructing regionally integrated learning destinations, provide practical guidance for the development and utilization of TLRs.

However, the underexplored spatial dimension of TLRs points out directions for future research. By filling these gaps through interdisciplinary and data-driven research, researchers can further unlock the potential of TLRs in promoting lifelong learning and sustainable tourism development. Overall, this study lays a solid foundation for future research and practice in the field of tourism learning resources, and it is expected to inspire more in-depth exploration and innovative practices in this area.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, S.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Y.L.; Visualization, Y.L.; Supervision, J.L.; Funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 42271247).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.F.; Chen, H.L. Regional research on leisure consumption preferences: Empirical analysis based on geographic big data. Geogr. Res. 2025, 44, 861–875. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, S.X.; Cai, X.M. Rural Tourism and Reconstruction of Rural Residents’ Mentality and Order. Tour. Trib. 2025, 40, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China. The Domestic Tourism Enhancement Plan (2023–2025). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202311/content_6914996.htm (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Bai, C.H.; Wang, H.Y. Touristic Learning: Theoretical Review and Research Agenda. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2018, 21, 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Q.W. Agricultural Cultural Heritage Tourism: A New Field. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, R.; Yang, Q. Tourism Imagination and Local Production: A New Anthropological Exploration of Ethnic Tourism Research. J. Guangxi Univ. Natl. 2024, 46, 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.Y. The Innovation and Establishment of Fundamental Theories of Tourism in the Context of Chinese Path to Modernization. Tour. Hosp. Prospect. 2024, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pitman, T.; Broomhall, S.; Majocha, E. Teaching Ethics beyond the Academy: Educational Tourism, Lifelong Learning and Phronesis. Stud. Educ. Adults 2011, 43, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Falk, J. Visitors’ Learning for Environmental Sustainability: Testing Short- and Long-Term Impacts of Wildlife Tourism Experiences Using Structural Equation Modelling. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Figueroa, F.; Vanneste, D.; Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Farfán-Pacheco, K.; Rodriguez-Giron, S. Research-Based Learning (RBL): Added-Value in Tourism Education. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 28, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueddefeld, J.; Duerden, M.D. The Transformative Tourism Learning Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 94, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.A.M.; Shelley, B.; Ooi, C.S. Uses of Tourism Resources for Educational and Community Development: A Systematic Literature Review and Lessons. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.Y.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Tao, R.Y.; Kong, X. Constructing Pastoral Songs: Research on Local Promotion and Rural Consumption in the Context of Tourism Development. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1956–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.Y.; Zhang, X.C.; Gao, N.; Song, H.; Wang, L. Research on the Measurement and Impact Path of Diversified Interaction Among Tourists in Immersive Tourism Scenarios. Geogr. Sci. 2025, 45, 732–743. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.S.; Lv, R.X. Family Tourism and the Formation of Human Capital among Young People: Facts, Mechanisms, and Policy Implications. Tour. Trib. 2025, 40, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, K.; Wang, X. Review and Research Prospects for the Update of the National Standard for Classification, Survey, and Evaluation of Tourism Resources. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 1525–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Gao, X.Y.; Zhang, S.R.; Zhang, T.Y. Regional Combination of Tourism Resources: Connotation, Identification Technology, and Key Issues. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 1493–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.C.; Huang, S.H.; Zhang, L.Y. Digital Humanities: A New Path for the Development of Red Tourism. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H. The Practical Application and Contemporary Reflection of Rogers’ Free Learning Theory. Res. Technol. Manag. 2021, 41, 240. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.F.; Huang, M.L. Anti-Customer as the ‘Main’? Research on Tourist Performance Behavior and Influencing Factors in Dehang Miao Village, Xiangxi. Tour. Trib. 2025, 40, 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Du, T.; Bai, K.; Huang, Q.Y.; Wang, X. The Social Construction and Core Value of Red Tourism Resources. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.S.; Lu, L.; Han, Y.G. Research Framework of Tourism Resources from the Perspective of New Tourism Resource Concept. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 551–567. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.J.; Zeng, B.W.; Zhang, H.; Song, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ma, B.; Sun, J.; Ye, C.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, S.; et al. New Quality Productive Forces and High-Quality Development in Tourism: Problems, Cognition and Optimization Direction. Tour. Trib. 2019, 39, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.L.; Song, R.; Jin, C.; Li, G.; Lu, L.; Wang, Z.; Lu, S.; Wang, H.; Zou, T. Innovative Development of Tourism Resources in the Construction of China’s Modern Tourism Industry System. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 855–875. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.H.; Kong, Y.Y.; Li, X.G.; Li, J. The Spatial Mismatch and Driving Mechanism between the Abundance of Tourism Resources and Online Attention under the Background of Traffic Economy. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 934–953. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.Y.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y. The Mountain Is There: The Intrinsic Motivation of Mountain Adventurers and the Influence Mechanism of Their Adventure Behavior Intentions. Tour. Trib. 2024, 39, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.H.; Huang, S.H.; Zhong, L.N.; Xie, Y.F. Phases, Patterns and Impacts of Youli (Experoutination) Development: Building a Research Framework. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 50–67. [Google Scholar]

- An, C.G.; Mogh, P.; Xiao, Z.Q. Study on the Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Educational Tourism Resources in China. J. Northwest Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 58, 99–105+112. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, M. Learning from Museums: Resource Scarcity in Museum Interpretations and Sustainable Consumption Intention. Ann. Tour. Res. 2025, 112, 103955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.C.; Meng, F.Q. A Study on the Teaching Mechanism in Museum Research Tourism from the Perspective of Situated Cognition and Learning Theory. Chin. J. EcoTour. 2023, 13, 494–509. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.M.; Wu, E. A Study on the Recreational and Educational Functions of Botanical Gardens Based on Tourists’ Perceived Value: Taking Beijing National Botanical Garden and Kew Gardens in the UK as Examples. J. Beijing For. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 23, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.X.; Huang, J.Y.; Chen, Q.Y.; Meng, W. The Impact of Nature Games on Children’s Tourism Communication Behaviors: A Case Study of Research Tourism Practices. Tour. Forum 2025, 18, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, L.; He, J.J.; Li, P.T.; Song, Y.; Wu, X. Political Context and Heritage Representation: The Historical Changes of the Representation Texts of the Liu Family Manor Museum in Sichuan. J. Tour. Stud. 2017, 32, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Mao, R.; Wang, C. Digitally Enriched Exhibitions: Perspectives from Museum Professionals. Tour. Manag. 2024, 105, 104970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.J.; Yang, Z.D.; Shu, J.P. Exploring the High-Quality Development of Cultural, Sports, and Tourism Consumption Scenarios Empowered by New Quality Productivity. Sports Cult. Guide 2025, 4, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Lin, D.; Xiao, H. The Collision of Tradition and Fashion: How Anthropomorphizing Museum Exhibits Influences Cultural Inheritance. Tour. Manag. 2025, 109, 105133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yang, X.X.; Du, M.T. Study on the Spatial Distribution Characteristics of National Ecotourism Demonstration Areas in China. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 34, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Normann, Ø. The Link between Travel Motives and Activities in Nature-Based Tourism. Tour. Rev. 2013, 68, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.X.; He, H.; Guo, L. Nature Connectedness: A Study on the Experience of Nature-Based Educational Tourism. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 49, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.R.; Zhang, C.Z. Knowledge-Based Governance of Heritage Tourism Destinations: A Case Study of Danxia Mountain. Hum. Geogr. 2024, 39, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C.Q.; Yang, X.Z. Research Progress and Implications on the Relationship between Natural Value and Human Well-being from a Tourism Perspective. Tour. Trib. 2025, 40, 134–149. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.F.; Ming, Q.Z. Research Progress and Prospects of Mountain Tourism Experience. Tour. Sci. 2024, 38, 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.W.; Huang, Z.F.; Wang, Z.F.; Ming, Q.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Su, M.; Xu, D.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, K. New Quality Productivity Empowers the Deep Integration of Culture and Tourism from the Perspective of Rural Revitalization. Resour. Sci. 2024, 46, 2335–2354. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Yang, X.; Xie, H. The Impacts of Mountain Campsite Attributes on Tourists’ Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions: The Mediating Role of Experience Quality. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2024, 32, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Liang, L.K. Construction and Empirical Study of Evaluation Index System for Science Popularization Tourism in Geopark Scenic Areas: A Case Study of Yuntai Mountain Global Geopark in Henan. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 36, 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, N.; Rong, Y. A Study on the Development Model of Ecological Research Tourism in Ethnic Areas: Taking Four World Natural Heritage Sites in Guizhou as Examples. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2022, 43, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.J. Tourism Experience and Aesthetic Education: The Aesthetic Connotation and Aesthetic Education Characteristics of Study Travel. J. Aesthetic Educ. 2019, 10, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, N.; Dai, X.; Ding, C.B.; Wu, B.H. Therapeutic Attributes of the Recreational Belt around Metropolis (ReBAM) and Their Impacts on Recreationists’ Perceived Health Benefits. Tour. Trib. 2025, 40, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.R.; Chen, Y.X.; Chen, L. Theoretical Reflection and Practical Exploration on the Development of Sports Tourism Complexes in China under the Background of Rural Revitalization. J. Sports Stud. 2022, 36, 33–42+62. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.L.; Song, X.H.; Liu, X.Q.; Li, D. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Online Attention to Camping Activities in China. Tour. Sci. 2024, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- McGladdery, C.A.; Lubbe, B.A. International Educational Tourism: Does It Foster Global Learning? A Survey of South African High School Learners. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Li, L. Curriculum Design of Rural Geographic Study Travel: Era Implication and Practical Appeal. Teach. Ref. Middle Sch. Geogr. 2023, 28, 72–75+80. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.C.; Chen, G. A Study on the Construction of Heritage Identity in Study Travel at Heritage Sites From an Embodied Perspective. World Reg. Stud. 2023, 32, 166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Svobodová, H.; Mísaová, D.; Durna, R.; Hofmann, E. Geography Outdoor Education from the Perspective of Czech Teachers, Pupils and Parents. J. Geogr. 2019, 119, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.; Carvalhinho, L.; Baptista, A.V. Experiential Learning in Sport Tourism Curriculum: A Case Study at the University of the Algarve. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2024, 35, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pung, J.M.; Gnoth, J.; Del Chiappa, G. Tourist Transformation: Towards a Conceptual Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 81, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhu, H. Educational Tourism: Integration of Tourism Context and Education under the Guidance of Authenticity. Tour. Trib. 2020, 35, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Teng, J.L. The Driving Mechanism of Awe and Pride on Tourists’ Civilized Tourism Behavior Intentions in the Development of Red Tourism Resources. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 1760–1776. [Google Scholar]