Abstract

Green Public Procurement (GPP) is a key tool in European strategies to promote sustainability in public procurement. This study examines the integration of GPP criteria in the National Action Plans (NAPs) of the European Union Member States, with a focus on the construction and urbanizing fields. Through a comparative analysis of policies and regulatory instruments, the main differences in terms of mandatory application between countries in the monitoring and implementation of GPP are highlighted. The comparative analysis of 27 countries reveals significant variation in mandatory execution, regulatory frameworks and monitoring mechanisms. This study proposes an integrated set of indicators that align GPP performance with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda, providing an holistic framework for the evaluation of policy and strategic planning. The research also explores the role of environmental performance indicators—such as energy efficiency, CO2 emissions reduction and the use of sustainable construction materials—highlighting how these criteria support the ecological transition and contribute to the achievement of the EU climate objectives. The findings offer insights to strengthen the strategic role of GPP in sustainable environmental and territorial planning.

1. Introduction

Sustainability is predicated on the principle that present generations should fulfil their demands without jeopardizing the capacity of future generations to satisfy theirs [1]. This approach has directed national and subsequently worldwide policies and practices since the early 2000s, focussing on achieving a balance between economic development, social fairness and environmental conservation.

With the Paris Agreement of 2015 [2] and the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [3], many countries around the world, including European ones, committed to developing policies and actions in multiple sectors by adopting directives from a circular economy perspective. This is to strengthen the response to climate change through financial flows consistent with low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient growth. At the European level, these commitments are reinforced by the European Green Deal, introduced by the European Commission in 2019 and updated in July 2021, which aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030, aspiring to establish the first climate-neutral continent by 2050 [4].

This ambitious plan integrates measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote the circular economy and protect biodiversity. In the light of these international and European directives, sustainability has acquired relevance not only in environmental terms but in terms of complementary aspects, such as the economic and social inequalities of the community and the behavior of operators in markets.

European attention to these issues began in 2008 with the introduction of Green Public Procurement (GPP), which serves as a key instrument in the European strategy for “Sustainable Consumption and Production” [5]. This initiative aims to foster a market for products and services with a reduced environmental impact by regulating public administration procurement processes to prioritize the acquisition of goods or services according to their environmental effects across their entire life cycle [6].

The GPP framework aims to establish clear, verifiable, justifiable and ambitious environmental criteria for products and services. This is grounded in a life-cycle approach and supported by scientific evidence regarding products’ conformity, such as Ecolabels [7]. This approach seeks to foster a comprehensive understanding of the landscape, advocating for practices that minimize environmental impacts throughout the entire life cycle of goods and services, thereby aiding the ecological transition of regions.

Numerous studies have analysed the evolution and application of green procurement strategies in the public and private sectors, highlighting their potential to drive markets towards greater sustainability [8,9]. In particular, the development of procurement criteria from a strategic sustainability perspective has been identified as a key factor in enhancing the effectiveness of such policies [10]. Recent OECD findings confirm this trend: results from the 2022 survey on Green Public Procurement (GPP), carried out in 38 countries, clearly show that GPP is increasingly recognized as a major driver for innovation and sustainability [11] However, more recent research highlights how, despite regulatory progress, operational and cultural obstacles persist that limit their full implementation at the European level [12]. In this context, the role of digitalization as an enabling factor for the greater effectiveness of sustainable procurement policies is emerging. In particular, a systematic review of the literature analyzed 68 articles published between 2001 and 2017 in peer-reviewed scientific journals. The results confirm that the use by governments of electronic and digital tools can significantly contribute to the promotion of sustainability practices, especially in developing countries, facilitating the sharing of environmental requirements, access to markets and performance monitoring in a way that is consistent with Sustainable Development Goal 12.7 [13].

The European Union (EU) has developed several tools, including the European GPP criteria, to facilitate the inclusion of green aspects in public procurement by Member States. Each one can define, on a voluntary basis, through the formulation of its own National Action Plan (NAP GPP) [14,15], the criteria to be adopted to make public procurement green. Italy is currently the only EU country where the adoption of Minimum Environmental Criteria (MEC) has been made mandatory in public procurement relating to services, supplies and works [16].

Paying attention to the field of construction and urban transformation processes, as they are representative of one of the main sources of environmental impact, it is important to highlight EU Directive 2024/1275, also known as the “Green Homes Directive” (or energy performance of building directive—EPBD), which came into force on 28 May 2024; this represents a key pillar of the “Fit for 55” reform package, with the aim of drastically reducing CO2 emissions from buildings in Europe and achieving complete decarbonization by 2050 [17]. The EDF’s Enforcement Toolkit, a 2024 guidance document created by the European Disability Forum, provides a pragmatic interpretation of the EPBD, emphasizing critical implications for accessibility, inclusive renovation strategies and the significance of public procurement in achieving energy-efficient and socially sustainable building stock [18].

These measures support sustainable urban regeneration and the promotion of a resilient built environment, integrated into the landscape’s context and consistent with the principles of climate mitigation and adaptation.

Through a comparative analysis, we intend to highlight how the adoption of specific criteria is effective in achieving European objectives and contributing to the transition to a more sustainable society within the timeframe set by the EU. This analysis aims to contribute to the strategic role of environmental and territorial design in the implementation of sustainable public policies.

2. Materials

2.1. GPP Objectives

Since 1996, the EU has systematically tackled the issue of green procurement through initiatives such as the Green Paper on Integrated Product Policy and the Sixth Environment Action Programme, formulating a targeted strategy for green procurement [19].

Communication COM(2001) 274 [20], entitled “Community public procurement law and the possibility of integrating environmental considerations into procurement”, outlined the actions to be taken by Member States for the implementation of GPP. The guiding principles contained in this Communication have been incorporated into Directives 2004/17/EC [21] and 2004/18/EC [22], which allow contracting authorities to consider non-economic variables but also environmental ones in public procurement procedures. These directives have set out specific objectives, including increasing the use of green procurement, creating demand for products with high environmental standards and implementing innovative technologies in the public sector.

In 2003, the European Commission (EC) called on Member States to develop National Action Plans (NAPs) to integrate environmental aspects into public procurement in COM(2003) 302 [23]. The subsequent Communication (COM(2008) 400) [5] identified ways to integrate environmental considerations into public procurement, making available the Green Public Procurement Training Toolkit, which contains an operational guide for the inclusion of environmental criteria in tenders. Directives 2014/24/EC and 2014/25/EC have further promoted innovation, including environmental protection, social responsibility and the fight against climate change [24].

National Action Plans (NAPs), although not obligatory, offer considerable political motivation for public administrations to adopt greener purchasing practices, tailoring strategies to the unique political and social contexts of each Member State [25].

These plans must contain an assessment of the current state of public procurement by

- Identifying areas where environmental impact can be improved;

- Setting ambitious targets to be achieved in the next three years;

- Specifying the concrete measures that will be taken to achieve these objectives.

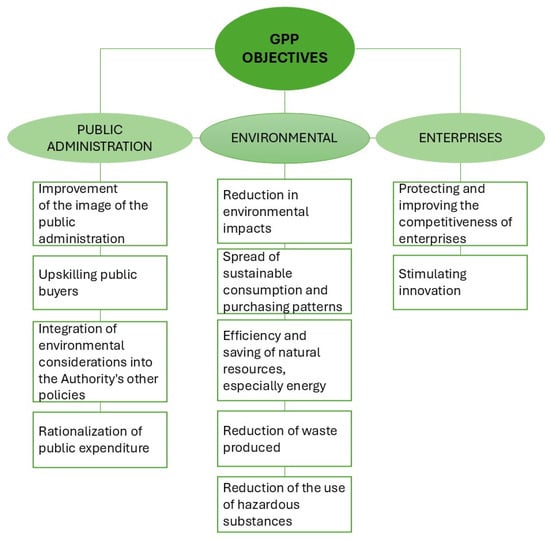

Public authorities implementing GPP practices focus not only on optimizing procurement and consumption but also on enhancing the environmental quality of the goods and services they procure. Their commitment aims to achieve specific objectives, such as integrating Minimum Environmental Criteria into public policies designed to promote a systemic transformation of regions, effectively harmonizing environmental quality, collective well-being and social innovation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

GPP objectives (Source: Own elaboration starting from https://gpp.mase.gov.it/Home/CosaEGPP, accessed on 15 May 2025).

2.2. National Action Plans (NAPs)

NAPs are key strategic tools for the implementation of GPP in the various EU Member States. Their objective is to advance sustainable procurement practices within public administrations by including environmental criteria into purchase choices, so fostering a more responsible management of public resources.

NAPs have several key objectives, including

- Integration of Environmental Criteria: Establishing clear guidelines for the integration of GPP criteria into purchasing procedures, encouraging public administrations to consider the environmental impact of purchased goods and services;

- Promotion of Sustainability: Encouraging the purchase of products and services that reduce environmental impacts, thus contributing to long-term sustainability;

- Awareness and Training: Providing training and resources for staff involved in purchasing processes, ensuring that they are informed about GPP criteria and their implications.

NAPs consist of several components: an initial analysis of the current territorial condition, the status of public procurement and existing sustainable practices within the country; a section focused on defining short- and long-term objectives for the integration of GPP criteria; another detailing the measures and actions intended to achieve the established objectives; and finally, a section dedicated to monitoring progress [26].

The adoption of NAPs can be characterized as a circular process comprising several interconnected steps, as illustrated in Figure 2. This process involves the formulation of policy strategies at the national level, aimed at integrating environmental criteria into public procurement. National and priority criteria are established based on an analysis of the specific context and needs of the country, identifying sectors where the implementation of GPP can yield significant environmental and economic benefits. Subsequently, the monitoring of the actions undertaken and the objectives set by the member state through the NAP is anticipated, enabling the review and updating of plans to incorporate improvements in contract selection criteria and overarching strategies, while considering advancements in technology, market developments and regulatory changes.

Figure 2.

NAP adoption (Source: Own elaboration).

The EC provides multiple tools to support Member States in implementing effective GPP practices [27].

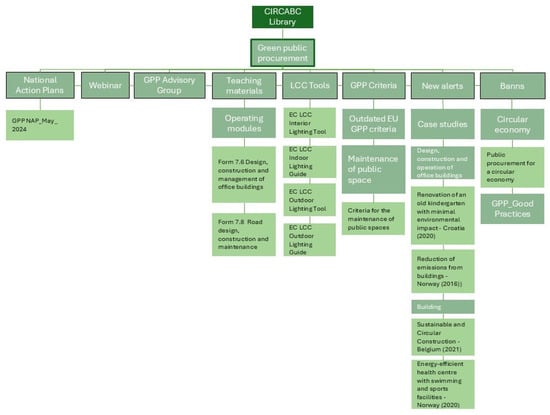

The EC has established an open-source collaborative online platform named CIRCABC, which stands for “Communication and Information Resource Centre for Administrations, Businesses and Citizens” [28]. In the context of green procurement, in the CIRCABC library it is possible to identify several sections in which case studies, guidelines and good practices between administrations, businesses and citizens are published (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

CIRCABC Library (Source: Own elaboration).

These tools were used to carry out a study and a subsequent analysis on the adoption of NAPs at the European level, analyzing the level of mandatory GPP policies and practices, with particular attention to the construction and urban transformation sector. This study made it possible to assess the state of implementation of the different national GPP strategies and identify best practices in the construction and urban redevelopment sector.

2.3. European GPP Criteria

A critical element in GPP strategies is the criteria and their connection with NAPs, enabling EU Member States to establish specific strategies for advancing green procurement.

The EC has developed voluntary criteria for GPP, specific to various product categories, with the aim of providing practical support to public administrations interested in adopting more sustainable purchasing practices. A significant policy shift occurred with the adoption of the Circular Economy Action Plan in 2020 [29], which marked a gradual transition from voluntary guidelines to mandatory minimum GPP criteria within sectoral regulations. This process was accompanied by the introduction of reporting obligations, intended to monitor and strengthen the commitment of Member States to sustainable procurement.

Within this evolving framework, as early as 2013, Bratt et al. [10] made a valuable contribution in the literature by proposing a strategic approach to the development of procurement criteria. Their work highlights the importance of integrating long-term sustainability objectives into procurement processes using systems thinking. This approach reinforces the role of public procurement as a driver of systemic transformation, aligning operational decisions with broader environmental and policy goals.

Complementing this perspective, Górecki (2020) [30] underscores the synergy between GPP and circular economy strategies, emphasizing that integrating green procurement into such strategies not only improves resource efficiency but also fosters innovation by promoting sustainable design and life-cycle thinking.

Manta et al. [31] provided a comprehensive systematization of current concerns surrounding sustainable public procurement, highlighting the importance of integrating all sustainability dimensions—particularly the social one—into public procurement legislation and practice.

Ortega et al. [32] conducted a systematic literature review and analysis of GPP research from 2003 to 2023, identifying the main research gaps and emphasizing the need for qualitative insights and contextual understanding in developing countries.

The GPP criteria established by the European Union serve as a crucial instrument for incorporating sustainability into public processes. The criteria are formulated with a comprehensive view of the product’s life cycle, focussing on minimizing greenhouse gas emissions, optimizing the utilization of natural resources, enhancing energy efficiency and encouraging the use of sustainable materials and production methods [33,34].

The criteria are formulated for seamless integration into procurement documents, enabling public authorities to adopt them with minimal administrative challenges. This flexibility enables the adaptation of GPP to various local contexts across Member States, promoting a gradual shift towards more sustainable consumption and production practices. The NAPs establish specific targets and identify priority areas for focus, including buildings, energy, transport and utilities. In the construction and urban transformation sector, GPP criteria can inform the utilization of sustainable materials, enhance energy efficiency, reduce emissions and facilitate the development of green infrastructure.

Each NAP reflects the needs and priorities of the national context, while maintaining consistency with broader European objectives.

These developments are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Voluntary GPP criteria at European level.

Many voluntary GPP criteria developed by the EC are aligned with the requirements of the EU Ecolabel [35] and the EMAS (Eco-Management and Audit Scheme) [36]. The EU Ecolabel labels and EMAS certifications play a key role in the framework of GPP criteria, contributing significantly to the integration of environmental considerations into public procurement processes. These criteria are designed in line with the requirements of the Ecolabel labels and with the principles of the EMAS, thus facilitating the adoption of environmental standards in calls for tenders. The link between the GPP criteria, Ecolabel and EMAS ensures not only the simplification of procedures, but also a Europe-wide harmonization of sustainable procurement practices. The EU Ecolabel represents an official guarantee, recognized at European level, certifying that certified products or services comply with high environmental standards throughout their entire life cycle, from production to disposal. The EMAS, on the other hand, is a voluntary environmental management system for organizations that want to assess, improve and communicate their environmental performance. Both facilitate the integration of GPP criteria into calls for tenders, contributing to the achievement of environmental sustainability objectives, and can be used to define award criteria, rewarding bids with superior environmental performance; moreover, in the verification phase, the Ecolabel and EMAS save time and resources, as they represent an official certification that automatically attests compliance with the required requirements.

This approach is fully supported by European legislation. In particular, Article 43 of Directive 2014/24/EU [37] regulates the use of labels in public procurement, authorizing administrations to apply for certified products or EMAS registration, provided that the requirements of the labels and EMAS are relevant to the subject matter of the contract, based on scientific criteria and developed in a transparent and accessible manner.

3. Methods

3.1. Methodological Pathway

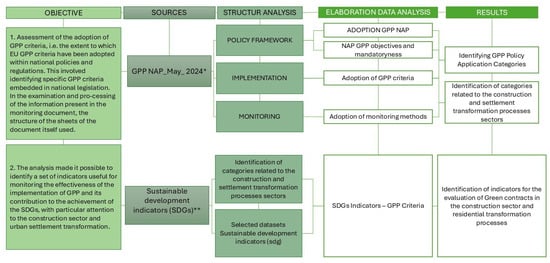

This study aims to evaluate the integration of GPP criteria within the NAPs of the Member States of the European Union, with particular attention to the application of these criteria in construction and urban settlement transformation projects, underlining how the adoption of design strategies compliant with the principles of GPP not only contributes to reducing the environmental impact of public works but also offers significant economic benefits for contracting authorities, improving efficiency in the use of resources and promoting a more sustainable development model. The importance of integrated strategic actions capable of directing urban transformation towards outcomes of environmental quality, resilience and territorial regeneration is highlighted, promoting intersectoral approaches involving policies, design and governance. Figure 4 illustrates the methodological pathway undertaken to attain the study’s objective; it outlines two main objectives, the sources consulted, the structure of the documents analyzed, the categories of data extracted and the results derived from this process. Objective n.1 was to evaluate the extent to which GPP criteria have been adopted, specifically by assessing the integration of EU GPP criteria into national policies and regulatory frameworks. This required the identification of concrete criteria embedded in national legislation. The analysis was carried out by examining and interpreting the content of official monitoring documents, using their internal structure as a methodological reference. Objective n.2 aimed to identify a set of indicators suitable for monitoring the effectiveness of GPP’s implementation and its contribution to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with a particular focus on the construction sector and the transformation of urban environments.

Figure 4.

Methodology utilization (Source: Own elaboration; Legend: * [31], ** [36]).

To carry out the analysis of the NAPs adopted by EU Member States, the monitoring document published in May 2024 in the CIRCABC Library by the GPP Advisory Group was used as a source [38,39].

The group set up in 2008 by the EC as part of the strategy outlined in the Communication “Public Procurement for a Better Environment” (COM(2008) 400 final) is composed of experts from the Member States of the European Union and representatives of key stakeholders, including Business Europe, UEAPME (European Association of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) [40,41], the European Environment Bureau/BEUC (European Consumer Organization) and ICLEI (Local Governments for Sustainability) [42].

The monitoring document in Table 2 consolidates the three forms at European country level. The structure of the factsheets made it possible to carry out a comparative analysis of the NAPs of the different EU Member States. The analysis assessed the level of integration of environmental criteria into public procurement procedures, the presence of specific and measurable objectives for the implementation of GPP, the definition of priority sectors (in particular construction and urban regeneration) and the monitoring mechanisms used to track progress in GPP’s implementation.

Table 2.

GPP NAP structure adopted at European level.

The analysis took into account the general structure of the NAPs, in line with the circular process illustrated in Figure 2.

A key component of the technique involved evaluating the implementation of GPP criteria, namely the degree to which EU GPP requirements have been integrated into national policies and regulations. This entailed recognizing particular GPP criteria integrated within national legislation. The analysis and processing of the information in the monitoring document utilized the document’s sheet structure (Table 2) and identified the indicators adopted by the European Union for tracking progress towards sustainability goals, aiming to adapt and employ them as a tool to assess the efficacy of Green Public Procurement (e.g., Sustainable Development Goals indicators) [43,44].

Analysis Policy Framework

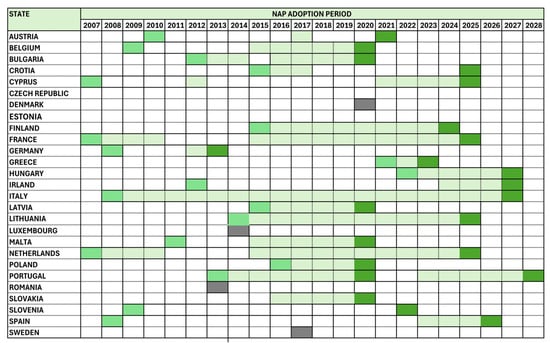

The “Policy Framework” sheet examines the adoption of GPP by the 27 EU Member States over the years, providing an overview of the implementation of GPP NAPs (Figure 5), as well as the associated objectives and mandatory GPP NAPs (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Adoption of NAP GPP in EU States. (Source: Own elaboration. Legend: Light Green: First NAP GPP adoption, Medium Green: NAP GPP update, Dark Green: Year up to which the last NAP update is valid, Gray: First and last NAP update coincide, Empty Cell: No NAP adopted that year).

Table 3.

Objectives and mandatory NAP GPP (own elaboration).

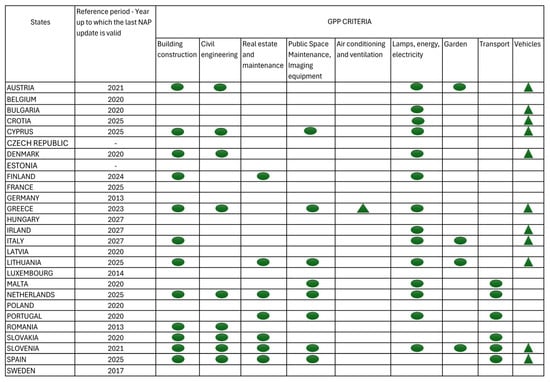

Analysis Implementation

The “Implementation” inspects the information provided by authorities in the monitoring plans, focussing on the mandatory application of GPP criteria and the objectives established by each Member State. This analysis aims to identify and differentiate the adoption of GPP criteria (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Adoption of GPP criteria referring to the latest PAN GPP update of each State. (Source: Own elaboration. Legend: Green triangle: criteria with a direct link to building interventions and urban transformation processes; Green ellipse: criteria with an indirect link, i.e., relevant to urban sustainability but not directly related to building activity).

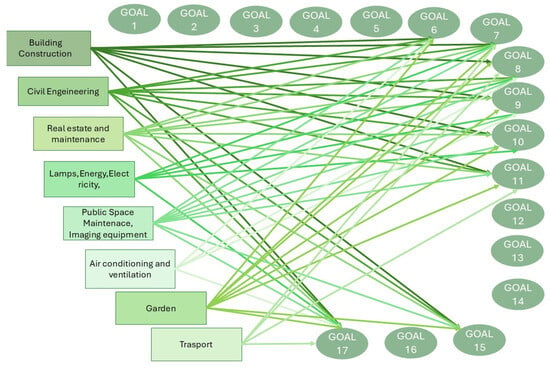

Analysis Monitoring

In the “Monitoring” section, relevant information was selected to summarize the monitoring process (Figure 7) employed by the participating countries in the project. The findings reveal prevalent and consistent patterns across various national contexts.

Figure 7.

GPP criteria with SDGs (Source: Own elaboration).

3.2. Selected Datasets on the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Indicators

The next phase of the methodology involved a further analysis aimed at achieving the GPP objectives illustrated in Figure 1, through the use of the indicators proposed at European level, with the aim of systematically assessing the effectiveness of the green policies adopted by the Member States.

Currently (2025), EUROSTAT foresees, within the section dedicated to monitoring GPP, an indicator aimed at measuring the share of public procurement procedures above EU thresholds (both in terms of number and value) that include environmental criteria. This indicator is relevant for the achievement of Sustainable Development target 12.7: “Promote sustainable public procurement practices, in accordance with national policies and priorities” [45]. However, the indicator is not currently in use as yet.

Although specific indicators for monitoring green procurement have not yet been activated, the European Union monitors the progress made towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda through a set of thematic indicators, each of which corresponds to one of the 17 SDGs [46,47,48].

The utilization of these indicators is essential for the monitoring and evaluation of GPP policies, thereby fostering more sustainable purchasing practices. Consequently, at the conclusion of the synthesis phase, a methodological process was initiated to identify and integrate the GPP objectives established by Member States and the SDGs advocated by the European Union, based on the results derived from the analysis of GPP criteria’s adoption at both national and European levels.

In addition, research was developed considering the results of recent studies that have contributed to carrying out a systematic analysis of the existing literature of GPP as a way to achieve sustainability goals [31,32].

The analysis involved the identification and evaluation of the most relevant GPP criteria for the construction and urban transformation sector, with the aim of identifying thematic categories to which the reference SDGs should be associated. For each category, the relevant indicators were then selected, in order to map the strategic connections between the objectives expressed in the NAPs for green procurement and the overall sustainability targets. The aim was to identify a series of shared indicators, capable of measuring in an integrated way both the level of implementation of GPP policies and the actual contribution of these policies to the achievement of the SDGs, with a specific focus on the construction sector and the transformation of urban settlements.

Overall, the methodology aimed to provide a complete and in-depth view of the implementation of GPP at the European level, identifying strengths and weaknesses and offering useful assessment tools for a more sustainable future. This comprehensive analysis provides an understanding of the current state of GPP policies in Europe and provides indications for improving the effectiveness and consistency of the strategies adopted by Member States for the evaluation of green procurement, with particular attention to the construction sector and urban settlement transformation processes

This is crucial, as the building sector accounts for 40% of energy consumption and 36% of greenhouse gas emissions, making it a major source of environmental impacts.

4. Results

4.1. Presentation of the Results

This study has facilitated a comprehensive overview, at the EU level, of the

- Analysis Policy Framework regarding the adoption of GPP NAPs

This analysis has elucidated the timeline for the adoption and revision of GPP NAPs throughout various EU Member States, as in Figure 5. Some countries have consistently initiated and revised their NAPs to align with emerging environmental and technological requirements, whereas others have retained outdated versions, so constraining the potential efficacy of Green GPP.

- National Analysis Policy Framework—NAP Objectives and requirements of GPP

The analysis indicated that certain nations, like Italy, have adopted a more rigid approach by mandating GPP standards, whereas others have enacted flexible policies that are not grounded in strict legislation (Table 3).

- Implementation Analysis—Adoption of GPP criteria

This analysis enabled the identification of states that have embraced European GPP criteria, those that have formulated their own national GPP criteria and specifically, the number of Member States that have implemented criteria pertaining to the construction category, at both building and urban levels, as in Figure 6.

- Analysis Monitoring—Implementation of monitoring techniques

The final segment of the analysis focused on the evaluation of GPP policies, emphasizing how Member States gauge the efficacy of the implemented methods and the instruments they employ.

- Curated Datasets—Identification of SDG indicators for green contract assessments

The research facilitated the identification of a series of indicators essential for assessing the efficacy of GPP’s implementation and its role in advancing the SDGs, particularly concerning the construction industry and urban development transformation.

4.2. Analysis Policy Framework—GPP NAP Adoption

This study conducted on the GPP policies implemented in the 27 Member States of the European Union has made it possible to elaborate a first comparative summary on the NAPs, considering the timing of implementation, the regulatory updates and any revisions that have occurred over time, graphically represented in Figure 5. This analysis shows that the Czech Republic and Estonia have never adopted an instrument for the implementation of GPP policies and that countries such as Hungary, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain have long-term plans, many of which are being adopted until 2027.

In some countries, such as Austria, Denmark and Luxembourg, when compiling the monitoring document, they did not indicate the period of adoption of the plans, which makes it difficult to have a complete picture of the planning. To ensure a complete view, it would be necessary to identify the validity period for the adopted plans (whether three-year, five-year or valid until a future update). The analysis also revealed that some states, such as Germany and Romania, which had adopted NAPs in the past, subsequently implemented policy strategies related to the circular economy, without, however, drafting National GPP Action Plans.

4.3. Analysis Policy Framework—NAP GPP Objectives and Mandatoriness

Table 3 provides a comparative overview of the objectives and levels of compulsoriness set by the 27 Member States in relation to the implementation of GPP in their respective Member States. The analysis shows that some states, such as Italy, Sweden and Germany, stand out for having adopted stringent measures and binding obligations. Italy has provided for the obligation of 100% of public procurement in accordance with the Minimum Environmental Criteria (MEC) [49], enshrined in art. 34 of Legislative Decree 36/2023 [50] as amended, expressing a clear political orientation towards the systematic adoption of GPP in all sectors of the public administration [51]. Sweden has made MEC mandatory for the car category, while Germany has introduced the use of Life Cycle Costing (LCC) [52] as a criterion for assessing the environmental impact and overall costs over the life cycle of purchased goods and services. Other countries, such as France, the Netherlands, Portugal, Ireland and Latvia, have set progressive numerical targets; these objectives, although not always associated with legal obligations, represent an important operational reference for the monitoring of GPP policies. France, for example, expects 100% of public procurement to include environmental considerations by 2025, while the Netherlands has differentiated application percentages based on administrative levels. Finally, in the case of Belgium, Austria and Slovenia, a more flexible or decentralized approach is adopted, entrusting the definition of objectives to regional authorities or focusing on specific sectors or commodity groups, where GPP measures are referred to as guidelines or recommendations, rather than as binding obligations [53,54].

It is therefore clear that the commitment to GPP is strongly influenced by the national regulatory context, the institutional structure and the strategic priorities of each country. The variety of approaches adopted reflects both the opportunities and challenges in building a common European framework for sustainable procurement, in line with the objectives of the Green Deal and the 2030 Agenda. Table 3 compares the goals and levels of mandatoriness established by the 27 Member States with regard to the incorporation of GPP within their NAPs.

It is worth highlighting that the promotion of sustainable public procurement practices in developing countries plays a crucial role in improving reporting, monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, thus contributing to the achievement of global sustainability goals.

4.4. Analysis Implementation—Adoption of GPP Criteria

This study identified and analyzed the GPP criteria at European level and the national criteria adopted by the Member States. Figure 5 shows the mapping of the GPP criteria adopted at national level by the Member States of the European Union, with particular attention to those relevant for settlement and urban transformation. The analysis was based on the identification and evaluation of GPP criteria both at European and national levels, selecting those most relevant to the construction sector on an urban scale.

The selection was made by identifying, for each Member State, the product categories to which GPP criteria were applied. Taking Italy as an example, GPP criteria have been defined for the following categories: interior furnishings, incontinence aids, work shoes and accessories in leather, paper, cartridges, construction, cultural events, public lighting, heating and cooling of buildings, industrial washing and rental of textiles and mattresses, urban waste and street sweeping, collective catering, disinfection, printers, textiles, vehicles, public green spaces and street furniture.

Those not pertinent to the construction sector and settlement transformation processes have been excluded from these categories. In this way, it was possible to identify macro-categories common to all Member States, including only the products relevant to the construction and settlement transformation sector. The categories identified are building construction, civil engineering, real estate and maintenance, public space maintenance, air conditioning, lamps, energy, electricity, garden, transport and vehicles. For each of these, the application by countries with different levels of relevance was investigated (Figure 6).

The symbology adopted allows us to distinguish two levels of relevance:

- Green triangle: Indicates the criteria with a direct link to building interventions and urban transformation processes (e.g., building materials, transport, vehicles, air conditioning systems).

- Green ellipse: Represents criteria with an indirect link, i.e., relevant to urban sustainability but not directly related to building activity (e.g., green management, maintenance, energy, etc.).

The analysis shows, in Figure 6, considerable heterogeneity between Member States in terms of the adoption of GPP criteria.

In general, the map shows that some countries (e.g., Italy, Romania, Cyprus) have integrated a wide range of GPP criteria into their public procurement systems, while others have a more limited or selective application.

4.5. Analysis Monitoring—Adoption of Monitoring Methods

The monitoring of the implementation of GPP in European countries presents considerable heterogeneity in terms of the tools, methodologies and areas observed. In most cases, monitoring is carried out through electronic procurement platforms, online forms, periodic questionnaires and statistical analyses of public contracts. Some countries, such as Poland, Portugal and Malta, have implemented automated and standardized systems, with mandatory annual reports that include specific indicators on the inclusion of environmental criteria in tenders and contracts.

Monitoring activities generally involve central, regional and local public authorities and concern both calls for tenders and contracts as well as organizational and strategic practices within the entities. The criteria monitored vary between European GPP criteria and national criteria, and they affect a plurality of product groups, including ICT products, paper, transport, construction and cleaning and catering services.

Some countries, such as Norway, France and Germany, are adopting multi-level monitoring models, which not only verify the application of green criteria but also assess the environmental, economic and social effects of sustainable procurement. In others, such as Italy or Austria, the monitoring systems are still being consolidated or show critical issues related to data collection and quality.

In particular, in Italy, the monitoring of Green Public Procurement is regulated by the Public Procurement Code (Legislative Decree 36/2023), which entrusts the ANAC (National Anti-Corruption Authority) with the task of collecting and managing data relating to the inclusion of Minimum Environmental Criteria (MEC) in tenders. Contracting authorities are required to communicate this data through the SIMOG system and the National Database of Public Contracts, tools that allow a first level of tracking and verification.

However, in practice, monitoring is often used almost exclusively to detect the amount of green procurement carried out, neglecting the assessment of the impacts generated in different sectors. This approach limits the strategic potential of monitoring, which should instead be understood as a fundamental tool not only to verify the effective implementation of MEC or GPP criteria but also to direct corrective strategies, assess the effectiveness of public policies and measure the environmental, economic and social effects produced by sustainable procurement on the economic and production system.

4.6. Identification of SDG Indicators for the Evaluation of Green Contracts

From the comparative analysis of the NAPs of the Member States, a relevant element concerned the possibility of integrating the GPP objectives with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda. In the final phase of the elaboration, a process of the recognition and mapping of the GPP objectives already adopted at national level was conducted, with the aim of assessing their consistency and alignment with the targets set out in the SDGs, with a view to regulatory and strategic integration. This comparison has made it possible to identify common areas of action, particularly in the construction and urban settlement transformation sector, where the interconnection between environmental criteria applied to public procurement and global objectives such as the fight against climate change (SDG 13), responsible consumption (SDG 12), urban resilience (SDG 11) and energy efficiency (SDG 7) is more evident (Figure 7).

Based on this analysis, the first set of integrated indicators has been developed (Table 4), with the aim of simultaneously monitoring the degree of implementation of the GPP policies and their contribution to the achievement of the SDGs. These indicators are configured as a strategic evaluation tool, useful for strengthening the coordination between public environmental sustainability policies, the application of green purchasing criteria and the measurement of the impact of the actions taken. This activity made it possible to highlight the potential of GPP as an operational tool to translate strategic objectives into concrete actions, promoting a systemic approach to sustainability that considers the entire life cycle of buildings, the efficient use of resources, the reduction in climate-changing emissions and social inclusion. In particular, the integration between GPP and SDGs represents, from this point of view, a fundamental lever for harmonizing environmental legislation with the international goals of sustainable development, offering public administrations an evaluation framework capable of guiding purchasing decisions, monitoring progress and guiding future policies.

Table 4.

SDG indicators–GPP criteria (source: own elaboration).

In particular, Table 4 shows how the GPP criteria adopted by EU Member States relate to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and related EUROSTAT indicators, distributing these links across different public procurement sectors (buildings, transport, energy, etc.). The most involved goals are as follows: GOAL 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and GOAL 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) are strongly present in all sectors, thanks to energy and raw material consumption indicators. GOAL 15 (Life on Earth) has a strong impact, especially in sectors related to construction, environmental maintenance and urban greenery. Finally, GOAL 17 (Partnership for the Goals) is also very transversal, suggesting a desire for international cooperation and sustainable financing. In addition, GPPs are used in a targeted way to promote environmental, energy and social objectives, with particular emphasis on energy efficiency, protection of the territory and the environment, social inclusion and gender equality. However, there are areas such as the protection of marine biodiversity or global equity that remain outside the perimeter of Green Public Procurement, probably due to the structural nature of the sectors.

From this analysis it was possible to observe that some indicators are repeated within different goals (highlighted in orange in Table 4), although they are associated with different categories depending on the specific theme of each goal. This phenomenon highlights how some indicators have a transversal nature and can be relevant for several thematic areas. This consideration suggests the opportunity to develop a single and integrated database of indicators, capable of measuring green procurement in a more efficient and consistent way in the context of construction and settlement transformation processes (Table 5).

Table 5.

Identification of indicators for the evaluation of green contracts.

5. Discussion

Recent research on GPP as a strategic instrument for promoting sustainability objectives within public administrations has been confirmed and expanded upon by the findings of this study, which corroborate and build upon that previous research. Previous publications have placed an emphasis on the role that GPP plays in fostering environmental innovation, market change and sustainable consumption habits. The findings of our comparative analysis lend credence to these conclusions. It demonstrates that although there is a heterogeneous implementation of GPP across EU Member States, countries that have mandatory GPP criteria, such as Italy and Germany, exhibit a more robust alignment with sustainability targets, particularly in the construction and urban transformation sectors.

When the indicators of the GPP criteria are combined with the SDGs, it becomes evident that GPP has the potential to serve as a vehicle that can transform global strategic goals into actions that can be measured and quantified. Our findings both verify and build upon the reasoning that Manta et al. (2022) [32] presented, which said that public procurement, when properly monitored, has the potential to significantly contribute to the achievement of the SDGs. In the construction sector, which is known for its high levels of carbon dioxide emissions and consumption of resources, it is evident that GPP standards have the potential to have a major beneficial impact on both the environment and the economy during the construction process. Previous studies on the circular economy and publications from the European Commission are consistent with this conclusion, which is in accord with these findings.

This study helps to bridge a methodological vacuum in the evaluation of sustainable procurement strategies by presenting a standardized framework of indicators that relate the implementation of GPP to the progress made towards SDGs. The OECD has called for more systematic monitoring methods, and this is in line with their request.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights significant variations among EU Member States in the adoption, scope, and enforcement of GPP. According to the findings, there is a significant amount of variation among European countries with regard to the date of the implementation of their National Action Plan (NAP), the obligatory nature of environmental standards, the demarcation of priority sectors and the effectiveness of monitoring mechanisms. The mandatory adoption of Minimum Environmental Criteria (MEC) in all public procurement is one of the ways in which Italy differentiates itself from other countries in Europe. This serves as a baseline for the systematic execution of GPP. Despite this, there are still considerable challenges, with a lack of coherence among plans and, in many cases, the absence of a modern regulatory framework.

As a result of the examination of the correlation matrix between GPP criteria and SDG indicators, it was discovered that there is a strong association between the categories of GPP targets that have been established by nations and the Sustainable Development Goals. This is especially true regarding energy efficiency (SDG 7), responsible consumption (SDG 12), urban resilience (SDG 11), and climate change mitigation (SDG 13). Because of this, it is necessary to improve the instruments that are used for evaluating and monitoring the environmental impact of public procurement to guarantee that the laws that have been adopted are effective. In order to facilitate an increase in green procurement, it is essential to establish a system of integrated and harmonized indicators that can simultaneously evaluate the implementation of GPP criteria and their impact on the attainment of the SDGs. It is stressed how important it is to use a cross-sectoral strategy, which can combine procurement regulations with urban planning, attempts to achieve climate neutrality and the principles of the circular economy. In this context, the Global Partnership Program is designed not only as a technical–administrative instrument but also as a catalyst for the ecological transformation of regions, urban regeneration and the advancement of models of development that are equitable and sustainable through the advancement of sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.G. and G.G.; methodology, M.R.G. and G.G.; software, G.G.; validation, M.R.G. and F.S.; formal analysis, G.G. and M.R.G.; investigation, G.G. and M.R.G.; resources, G.G. and F.S.; data curation, G.G. and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.G. and G.G.; writing—review and editing, M.R.G., G.G. and F.S.; visualization, M.R.G. and F.S.; supervision, M.R.G. and F.S.; project administration, M.R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This contribution was created in the context of the ongoing research project “Minimum environmental criteria in public procurement for an eco-friendly urban landscape: limits, potential and strategies—n. prot. RP124190D950E6F4”, Sapienza University of Rome.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Secretary-General. In Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/139811?v=pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; COM(2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Commission of the European Communities. Public Procurement for a Better Environment; COM(2008) 400 Final; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2008:0400:FIN:EN:pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Commission of the European Communities. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Action Plan on Sustainable Consumption and Production and a Sustainable Industrial Policy; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52008DC0397 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Commission of the European Communities. Green Paper on Integrated Product Policy; COM(2001) 68 Final; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. Available online: https://aei.pitt.edu/42997/1/com2001_0068.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Walker, H.; Brammer, S. Sustainable procurement in the United Kingdom public sector. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2009, 14, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appolloni, A.; Sun, H.; Jia, F.; Li, X. Green Procurement in the private sector: A state of the art review between 1996 and 2013. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C.; Hallstedt, S.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Broman, G.; Oldmark, J. Assessment of criteria development for public procurement from a strategic sustainability perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Harnessing Public Procurement for the Green Transition: Good Practices in OECD Countries; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Annunziata, E.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. Drawbacks and opportunities of green public procurement: An effective tool for sustainable production. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei-Bamfo, P.; Maloreh-Nyamekye, T.; Ahenkan, A. The role of e-government in sustainable public procurement in developing countries: A systematic literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 142, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Public Procurement Procuring Goods, Services and Works with a Reduced Environmental Impact Throughout Their Life cycle. Available online: https://green-forum.ec.europa.eu/green-public-procurement_en (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Che Cosa è il GPP. Available online: https://gpp.mase.gov.it/Home/CosaEGPP (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Repubblica Italiana. Decreto Legislativo 18 Aprile 2016, n. 50—Codice dei Contratti Pubblici. Available online: https://www.bosettiegatti.eu/info/norme/statali/2016_0050.htm (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD); Directive (EU) 2024/1275; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L_202401275 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Disability Forum. EDF Toolkit on the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive; European Disability Forum: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://www.edf-feph.org/content/uploads/2024/09/EDF-Toolkit-on-the-Energy-Performance-of-Buildings-Directive-August-2024.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Green Paper on Integrated Product Policy; (COM(2001)68 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52001DC0068 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Community Public Procurement Law and the Possibility of Integrating Environmental Considerations into Public Procurement; (COM(2001)274 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52001DC0274 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Union. Directive 2004/17/EC coordinating the procurement procedures of entities operating in the water, energy, transport and postal services sectors. Off. J. Eur. Union 2004, L134, 1–113. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32004L0017 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Union. Directive 2004/18/EC on the coordination of procedures for the award of public works contracts, public supply contracts and public service contracts. Off. J. Eur. Union 2004, L134, 114–240. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32004L0018 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Integrated Product Policy—Building on Environmental Life-Cycle Thinking; (COM(2003) 302 final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52003DC0302 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Directives 2014/24/EU and 2014/25/EU on public procurement and procurement by entities operating in the water, energy, transport and postal services sectors. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, L94, 1–135. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L:2014:094:FULL (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Review of Sustainable Public Procurement; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/2017-global-review-sustainable-public-procurement (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M.; Daddi, T. What factors influence the uptake of GPP (Green Public Procurement) practices? Ecol. Econ. 2012, 82, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Public Procurement Training Toolkit. Available online: https://green-business.ec.europa.eu/green-public-procurement/gpp-training-toolkit_en (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- CIRCABC. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/welcome (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Permanent Representation of Italy to the OECD. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20160813180100/http://www.rappocse.esteri.it/Rapp_OCSE/Menu/OCSE/Cos_OCSE (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Górecki, J. Circular economy and green public procurement in the European Union. In Sustainable Sewage Sludge Management and Resource Efficiency (Working Title); IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Carrasco, P.; Iannone, F.; Ferrón Vílchez, V.; Testa, F. Green public procurement as an effective way for sustainable development: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 126, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, O.P.; Panait, M.; Hysa, E.; Rusu, E.; Cojocaru, M. Public procurement, a tool for achieving the goals of sustainable development. Amfiteatru Econ. 2022, 24, 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Green Public Procurement Criteria and Requirements. Available online: https://green-forum.ec.europa.eu/green-public-procurement/gpp-criteria-and-requirements_en (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. A New Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; COM(2020) 98 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0098 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- How Governments Can Leverage Public Procurement for a Greener Future. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/how-governments-can-leverage-public-procurement-for-a-greener-future/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- European Commission. EU Ecolabel the Official European Union Voluntary Label for Environmental Excellence. Available online: http://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/eu-ecolabel_en (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS). Available online: https://green-forum.ec.europa.eu/emas_en (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Directive 2014/24/EU on Public Procurement; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32014L0024 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- CIRCABC. GPP NAPs_May_2024. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/44278090-3fae-4515-bcc2-44fd57c1d0d1/library/c23dd7e0-3f7e-4983-a964-bd9d98a0bbf4/details (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Green Public Procurement Advisory Group & National Action Plans. Available online: https://green-forum.ec.europa.eu/green-public-procurement/advisory-group-national-action-plans_en (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- UEAPME. Available online: https://eulacfoundation.org/en/european-association-craft-and-smes-ueapme (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Smeunited. Available online: https://www.smeunited.eu/about-us (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability. In Buying Green!—A Handbook on Green Public Procurement; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2016. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/837689 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. The EU and the United Nations—Common Goals for a Sustainable Future. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/sustainable-development-goals/eu-and-united-nations-common-goals-sustainable-future_it (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- United Nations. SDG Indicators. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/ (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- EUROSTAT, Circular Economy. Monitoring Framework. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/circular-economy/monitoring-framework (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- EUROSTAT. Selected Datasets. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/sdi/database (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- European Commission. Guidance on Life Cycle Costing; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017.

- Repubblica Italiana, Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica (MASE). Criteri Ambientali Minimi (CAM): Guida e Aggiornamenti Normativi; MASE: Rome, Italy, 2023. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Repubblica Italiana. Decreto Legislativo 31 Marzo 2023, n. 36—Codice dei Contratti Pubblici; Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, Serie Generale n. 77 del 31 marzo 2023; Repubblica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 2023.

- Maltoni, A. Contratti pubblici e sostenibilità ambientale: Da un approccio “mandatory-rigido” ad uno di tipo “funzionale”? Public procurement and environmental sustainability: From a “rigid-mandatory” to a “functional” approach? CERIDAP 2023, 3, 64–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Environment Agency (UBA). Life Cycle Costing and Procurement—Practical Examples from Germany; UBA: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Climate and Enterprise, Sweden. National Public Procurement Strategy: Implementation of Environmental Criteria; Government Offices of Sweden: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022.

- République Française, Ministère de la Transition écologique et de la Cohésion des territoires. Plan National Pour des Achats Durables (PNAD) 2022–2025; République Française: Paris, France, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).