Abstract

Enhancing the psychological well-being of college students through campus environment design is crucial, particularly in multi-ethnic regions where students’ restoration perceptions may be shaped by their cultural backgrounds. This study investigated the impact of four types of campus outdoor spaces on students’ restorative perceptions in Xinjiang, China’s multi-ethnic region, employing interviews and questionnaires. The results indicated that green and blue spaces had the highest restorative potential. Ethnicity significantly influenced perceived restoration, with Uyghur students exhibiting higher restorative perceptions in gray and green spaces compared to Han students. Uyghur students’ restoration perceptions were more closely associated with cultural displays and social support, and they were more sensitive to spatial types and environmental details. Furthermore, Uyghur students demonstrated higher restorative perceptions during social and reading activities, while Han students benefited more from contemplative activities. In conclusion, campus environment design should take into account ethnic cultural differences and behavioral habits to meet diverse psychological needs. This study offers targeted guidance for optimizing campus environments in Xinjiang, emphasizing the integration of ethnic cultural elements to create a multicultural and supportive campus landscape atmosphere.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

In the current fast-paced lifestyle, college students are confronted with escalating academic pressures, intricate social challenges, and anxieties regarding the future, which significantly impact their physical and mental health, as well as academic progress [1,2]. Attention restoration theory (ART), initially proposed by Kaplan S. (1995) [3,4], emphasizes how environments conducive to psychological detachment from stressors facilitate cognitive and emotional restoration. Herzog et al. (2003) [5] further highlighted ’Being Away’ as a critical dimension of restorative environments, underscoring its significance in reducing mental fatigue. Biophilic Design, introduced by Wilson (2003) [6], suggests that integrating natural elements into built environments strengthens human connections to nature, thereby improving psychological well-being, creativity, and stress reduction. This theoretical framework supports the development of restorative campus environments tailored to students’ diverse psychological needs.

Restorative perception, defined as an individual’s subjective experience and cognition of the environment’s restorative attributes, reflects the relaxation degree, stress alleviation, and psychological resource replenishment that students experience in specific campus settings. By delving into restorative perceptions, campus environment design can be refined to bolster its restorative function, which is of great significance for easing students’ psychological pressures and promoting their overall psychological health [7,8].

Xinjiang is historically characterized by cultural diversity, with distinct traditions shaping the spatial practices and environmental interactions among its ethnic groups [9]. Uyghurs, primarily residing in Southern Xinjiang, traditionally prefer ‘Aywang’ courtyard dwellings deeply rooted in oasis civilization, emphasizing communal spaces designed for collective social activities such as traditional dance gatherings, underpinned by strong intra-community social ties [10]. In contrast, the Han community generally exhibits dispersed social networks with comparatively weaker interpersonal bonds [11,12]. These socio-cultural differences influence spatial preferences significantly; Uyghurs show a strong affinity towards oasis-related symbols, including grape trellises and pomegranate trees [13], whereas Han populations typically prefer winding garden landscapes reflective of agrarian aesthetics [14,15,16]. These culturally rooted preferences likely influence students’ restorative perceptions of campus environments. Furthermore, Uyghur students from Southern Xinjiang may face greater adaptation challenges in university settings due to disparities in educational resources [17,18], making them potentially more sensitive to the psychological restorative functions offered by campus environments [19].

Colleges and universities in Xinjiang serve as vital platforms for cultural exchange and talent development across diverse ethnic communities. Designing restorative environments sensitive to cultural diversity is thus crucial for reducing psychological stress and ensuring comprehensive physical and mental health development among students.

1.2. Literature Reviews

Research has demonstrated that individuals from different cultural backgrounds exhibit varying emotional responses to similar environments. For instance, European tourists tend to derive mental health benefits from tranquil and natural green spaces [20], while Asians often view parks as venues for social and family gatherings [21]. Cross-cultural studies have also shown that the walkability of parks is more likely to evoke positive emotions among Shanghai visitors, whereas London tourists place greater emphasis on the imaginability of the environment [22]. Furthermore, studies focusing on the same environment have found differences in thermal perception and adaptation behaviors between Pakistani and Chinese students [23]. This phenomenon, known as effect heterogeneity, highlights the diverse responses of different groups to the same factor [24].

In Xinjiang, the unique cultural traditions, living customs, and values formed by various ethnic groups over a long historical development have profoundly shaped the psychological cognitive patterns and behavioral habits of college students from different ethnic backgrounds. This may lead to significant differences in their perceptions and needs of the campus environment [25,26,27]. However, most current studies on campus environments fail to fully consider the diversity of ethnic cultures. When examining the impact of the campus environment on students, the student population is often treated as a homogeneous whole, with a lack of in-depth analysis of the specific needs of students from different ethnic groups. This research gap makes it difficult to accurately meet the psychological needs of students from diverse ethnic backgrounds in campus planning and design and hinders the full realization of the campus environment’s potential to alleviate psychological pressure and promote mental health among all students. Therefore, exploring the campus restorative environment from the perspective of ethnic differences can not only provide targeted and effective guidance strategies for campus environment optimization but also promote the steady progress of the higher education on the path of multicultural symbiosis and common prosperity [28].

At present, most scholars primarily focus on the plant landscape or water features on campus and their impact on the psychological and physical conditions of college students [29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. The restorative value of open spaces such as plaza spaces and sports spaces has not received adequate attention. As a result, the perspective of campus restorative landscape design is relatively narrow, and the restorative function of campus spaces has not been fully explored. Each type of space in the campus plan has unique functions and characteristics to meet the diverse needs of college students [36,37]. For example, playgrounds are suitable for sports, helping to unleash students’ passion for sports and relieve stress [38]; plazas can serve as places for gathering, leisure, and socializing, promoting communication and interaction among people [39]. Therefore, incorporating squares and sports fields into the scope of restorative campus environment design can meet the diverse needs and preferences of college students, promote the effective use of campus space resources, and provide more comprehensive physical and mental health support for students.

The environmental characteristics of outdoor spaces on campus are crucial for promoting the physical and mental health of college students. Not only do plants and water features affect physical and mental health [40,41,42,43,44,45,46], but also, factors such as the comfort of seating, shading conditions, and the number of recreational facilities can influence the use of outdoor spaces and facilitate social interaction [47]. Additionally, spatial characteristics related to environmental quality, such as safety, culture, and sociality, together with the physical characteristics of the environment, affect people’s perception of outdoor spaces on campus [48,49]. These perceptions, in turn, impact an individual’s physical and mental health by influencing their emotions and behaviors [50].

In terms of space use preferences, some ethnic groups favor open and shared public spaces to promote group communication and interaction, while others pay more attention to relatively private and quiet spaces to meet the needs of individual introspection and thinking [51]. Regarding the psychological perception of color and decorative elements, different ethnic groups have different emotional connotations of various colors and patterns due to their unique cultural symbolism [52,53]. If these differences are not considered in campus environment design, they may fail to elicit positive psychological responses from students. Some ethnic groups have deep cultural and emotional ties with specific natural landscapes or ecological environments, leading to distinct ethnic characteristics in their expectations and needs for natural elements on campus [54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Therefore, understanding the spatial perception of students from different ethnic groups can aid in developing more informed campus planning.

Measurement of spatial perceptions commonly employs semi-structured interviews and structured questionnaires, wherein visitor satisfaction serves as a critical subjective indicator closely linked to environmental attributes [61]. Recent studies have expanded satisfaction measures into assessments of cultural ecosystem services, reflecting perceptions of environmental quality [62,63]. Satisfaction evaluation, grounded firmly in social science methodologies [64], enables a comprehensive assessment of students’ subjective feelings, attitudes, and overall responses to campus environments [65]. Questionnaires, being flexible, cost-effective, and capable of rapidly accumulating extensive data, can be tailored to address diverse dimensions of perceived environmental quality. Crucially, satisfaction measures capture subjective experiences rather than solely physical environmental attributes, effectively reflecting psychological states and behaviors [65]. Thus, satisfaction evaluation is an ideal tool for assessing the restorative potential of campus outdoor spaces, enabling rapid identification of deficiencies and revealing differences in environmental perceptions across ethnic groups through quantitative analyses.

Engagement in activities within a space is essential for experiencing its restorative benefits. Despite the presence of restorative features in the campus environment, the potential for restoration remains unrealized without interaction between individuals and the surroundings. Empirical research indicates that the type of activity significantly influences individual restorative perceptions [66,67]. Therefore, it is essential to investigate whether the nature of activity engagement differentially influences the restorative perceptions of students from distinct ethnic backgrounds.

The Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) is a psychometric tool designed to quantitatively measure individuals’ subjective evaluations of an environment’s restorative capacity [68]. Grounded in ART, the PRS assesses four key dimensions: Being Away (psychological detachment from routine demands), Fascination (effortless engagement with environmental stimuli), Compatibility (alignment between environmental affordances and personal goals), and Extent (coherence and scope of the setting) [4]. The Chinese version of the PRS, developed and validated by Ye et al. [69], consists of 22 items across these four dimensions, demonstrating robust reliability and validity in multiple studies.

1.3. Research Objectives

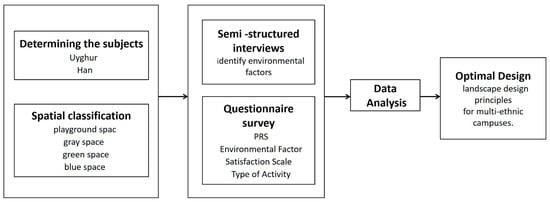

Based on the characteristics of campus outdoor spaces and land cover types [70], we categorized campus outdoor spaces into four types: green space, blue space, gray space, and sports space. We selected the Han nationality (42.24%) and Uyghur ethnic group (44.96%), which constitute the largest proportions in Xinjiang, as our research subjects [71]. Relevant data were obtained through questionnaire surveys to explore differences in their perception of campus outdoor spaces, aiming to better meet the restorative needs of students from different ethnic groups through campus planning (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research framework illustrating the study design and methodology.

It is important to emphasize that the choice of Han and Uyghur students as the initial subjects of this study does not imply exclusion of other ethnic groups. Rather, these two major groups provide an effective and representative starting point to initiate an in-depth analysis. Future research will progressively expand attention toward all ethnic groups, fostering broader inclusivity, cultural exchange, and integration across all student populations.

Based on the reviewed literature and the identified research gaps, the study formulated the following hypotheses: (1) Ethnic differences significantly influence the perceived restorative potential of campus outdoor environments. (2) Uyghur students require more diverse environmental attributes to achieve restorative effects compared to Han students. (3) Activities have different restorative effectiveness for Han and Uyghur students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

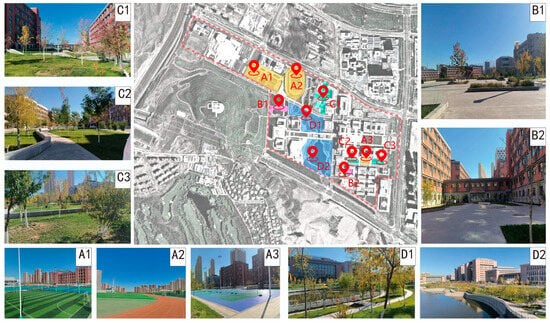

The present study was conducted on a university campus located in Xinjiang, a multi-ethnic region in Northwest China. The campus features a variety of botanical landscapes and activity spaces, such as woodlands, squares, lakes, and various types of sports fields. Additionally, the proportion of ethnic minority students is high, which provides a wide range of research samples for the study. Therefore, it is an ideal location to investigate the restorative perception of Han and Uyghur students in different campus outdoor spaces. After a site visit, 10 sample plots with high student traffic were selected for this study, representing playground space, gray space, green space, and blue space, respectively (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2.

Distribution of the sample points and real photos (A—Playground Space; B—Gray Space; C—Green Space; D—Blue Space).

Table 1.

Research site characteristics.

2.2. Interview Setting

A literature review was conducted to identify environmental factors related to psychological health and stress relief in campus environments. These factors were then combined with the characteristics of restorative environments from the restoration theory.

In this study, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 66 students (36 Han and 30 Uyghur) chosen by random sampling, averaging 43 min per interview. The process involved four steps: (1) getting full student lists of Han and Uyghur ethnic groups from university administration to form separate sampling frames, (2) performing equal probability random sampling for both groups using a random number generator, (3) checking participation willingness through phone interviews, and (4) successfully enrolling 30 participants from each ethnic group.

Interviews were structured around questions exploring students’ preferences and perceptions, including:

- “What kind of space do you like to rest in?”

- “What are the environmental factors in this space that influence your stress recovery?”

- “When you are tired or stressed, what activities would you like to do on campus to ease the discomfort?”

By synthesizing the results of the interviews and the literature review, 9 factors related to outdoor spaces on campus were ultimately selected, including noise, color, forms of plant, cultural displays, recreational facilities, seating materials, social support, thermal comfort, and spatial privacy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Restorative effects of the factors in campus outdoor spaces.

Activities that occur in campus outdoor spaces encompass reading, talking, walking, exercising, relaxing and reflecting, enjoying the scenery, listening to music, etc. The categories adopted: (a) reading or socializing, (b) walking/exercising, and (c) contemplating the setting exhibited relatively weak, moderate, and strong environmental interactions, respectively [66].

2.3. Questionnaire Survey

We identified environmental factors that may influence campus outdoor spaces through interviews and a literature review and subsequently developed a questionnaire comprising four sections: (1) Personal Information: This section includes questions on ethnicity, gender, age, home location, and type of activity. (2) Environmental Factor Satisfaction Scale: Respondents rate their level of satisfaction with each environmental factor in their space on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “very dissatisfied” to 5 = “very satisfied”). (3) PRS, utilizing the validated Chinese version containing 22 items assessing four dimensions: Being Away, Fascination, Compatibility, and Extent, rated from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 7 (“completely agree”). (4) Type of Activity: Respondents record the activities they engaged in within the space during the last 20 min.

The survey was administered in September 2024 under sunny and windless conditions. Considering the two-hour time difference between Xinjiang and Beijing, the survey was conducted from 16:00 to 19:00 Beijing time, a period when students are highly active outdoors and is conducive to data collection.

We enlisted 20 volunteers (10 Han and 10 Uyghurs) to assist with the survey. Each pair of volunteers was assigned to specific tasks at the designated site: (1) randomly selecting university students who were freely moving around the study area as survey participants, explaining the purpose and content of the study to them, and instructing respondents to sign the informed consent form and (2) assisting participants in completing and collecting the questionnaires while ensuring the quality of the questionnaires (a process that typically takes 5 min). A total of 2525 valid questionnaires were collected, of which 1257 were Han and 1268 were Uyghurs (Supplementary Materials Tables S1 and S2).

2.4. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed to compare the participants’ personal information. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to extract factor categories for the spatial environmental factors. The environmental factor satisfaction for the Han and Uyghur groups was determined based on the comprehensive percentage of satisfaction.

The study initially conducted analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the changes in restorative perception across the four types of spatial environments, aiming to identify the spatial environments with better restorative perceptions. Subsequently, participants were grouped by ethnicity, and the following analyses were conducted: (1) t-tests were utilized to compare the differences between the two ethnic groups in terms of the four dimensions and restorative perception scores in the four types of spaces, and (2) ANOVA was employed to compare the perceived restorativeness of the four types of spaces, with this comparison conducted separately for the two ethnic groups. Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation analysis was carried out between restorative perception and satisfaction votes for different environments to identify the environmental factors and categories related to restorativeness. The data collected in this survey were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The figures in this paper were plotted using Origin software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

The reliability of the PRS and the environmental factor satisfaction scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α), with all scales and their subscales having values exceeding 0.8, indicating excellent consistency. For PRS, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results showed that the average variance extracted (AVE) for all four factors exceeded 0.5, and the composite reliability (CR) values were all above 0.7, demonstrating strong convergent validity. For the satisfaction report, the KMO measure for the scale data was 0.803, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.05). Principal component analysis identified three main factors from the nine items: Sense, Facility, and Perception. Each factor had a value greater than 1. After rotation, the three factors explained variances of 25.945%, 25.730%, and 25.400%, respectively, with a cumulative variance explanation of 77.075%, exceeding 70%. This indicates strong structural validity of the items.

3.2. Ethnic Differences in Perceived Restorativeness

Significant differences in the overall PRS scores ( = 0.077, medium effect size) were found among the four space categories (Table 3). Green space had the highest PRS score (4.438), with Compatibility ( = 0.062, medium effect size) being the most influential factor. Among the environmental space categories, the playground had the lowest PRS score (3.865). Green spaces had the highest score (4.438), indicating that they were perceived to be more conducive to restoration than the other three spaces. Being away ( = 0.029, medium effect size), a core indicator of perceived restoration, received the highest score in blue space, while Extent ( = 0.010, small effect size) showed the lowest variability. Green spaces (p < 0.001) showed the most significant difference in restorative perception, and gray spaces (p < 0.001) also exhibited some differences. There was no significant difference in restorative perception of playground and blue space (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Differences in the means and standard deviations in four space categories.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations for different groups’ perceived restoration.

Regarding the Being away factor, there were no significant differences between the Han and Uyghur ethnic groups across most space types, except in gray and green spaces, where Uyghurs rated significantly higher than Han (gray spaces: p = 0.008 **; green spaces: p = 0.032 *). This indicates that Uyghurs felt a stronger sense of detachment from their usual environment in these spaces.

For the Fascination factor, Uyghurs were higher than Han across all space types, with statistically significant differences in gray, green, and blue spaces (gray space: p = 0.000 ***, green space: p = 0.000 ***, and blue space: p = 0.000 ***). This suggests that Uyghurs might find these spaces more captivating.

In terms of Compatibility, Uyghurs also rated significantly higher than Han in gray and green spaces (gray space: p = 0.000 ***; green space: p = 0.000 ***), while there was no significant difference in blue spaces (blue space: p = 0.626). This indicates that Uyghurs might perceive these spaces as more suitable or aligned with their needs or expectations.

As for the Extent, Han showed significantly higher than Uyghurs in playgrounds and blue spaces (playground: p = 0.000 ***; blue spaces: p = 0.000 ***), suggesting that Han perceive these spaces as offering more possibilities for activities or experiences.

For PRS, Uyghurs rated significantly higher than Han in gray and green spaces (gray space: p = 0.000 ***; green space: p = 0.000 ***), while there was no significant difference in blue spaces (blue space: p = 0.832). This suggests that Uyghurs perceive these spaces as having more positive impacts on mental health and recovery.

Overall, Uyghurs rated Fascination, Compatibility, and Perceived Restorativeness higher than Han, especially in gray and green spaces. This likely reflects a more positive evaluation and higher expectations of these spaces from the Uyghur perspective. Han, on the other hand, rated Extent higher in playgrounds and blue spaces, indicating they might value the diversity and activity possibilities these spaces offer more. These findings underscore the importance of considering different cultural backgrounds when designing spaces to ensure they meet the needs and preferences of diverse user groups.

Spatial types have statistically significant impacts on perceived restoration for both Han and Uyghur groups (Table 5). The F-value plays a crucial role in assessing these impacts, with higher values indicating more pronounced effects. Significant spatial type effects were observed for the Han ethnic group for the indicators of Being away (F = 15.672), Fascination (F = 10.283), Compatibility (F = 26.679), Extent (F = 5.118), and PRS score (F = 30.376). The Uyghur group also exhibited significant effects across these indicators, with larger effect sizes noted in Fascination (F = 31.084), Compatibility (F = 38.612), and the total PRS score (F = 52.644), suggesting a more substantial impact of spatial types on the Uyghur group. The Extent showed similar impacts between the two ethnic groups (Uyghur F = 5.218). The results confirmed that the Uyghur group was more significantly affected by environmental changes in their subjective restorative perception than the Han group.

Table 5.

The respective perceived restoration differences of four space categories.

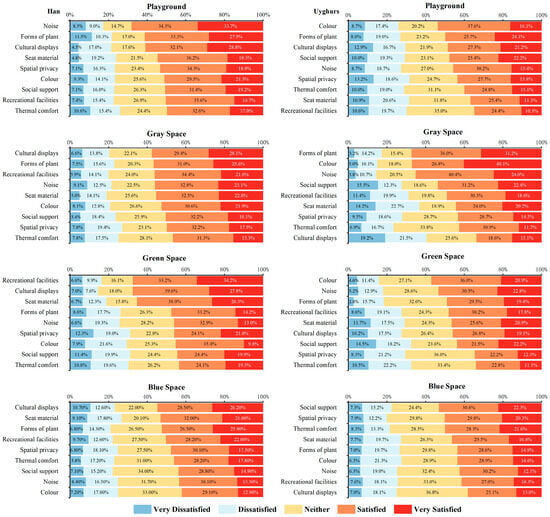

3.3. Satisfaction with Environmental Factors by Ethnicity

In playground, noise is the most satisfactory factor for the Han group, with nearly 70% satisfaction, while Uyghurs favor color, with over half satisfied. However, both groups show dissatisfaction with spatial privacy, thermal comfort, and seat material—24%, 26%, and 24% for Han and 32%, 29%, and 32% for Uyghurs, respectively. Both groups appreciate plant forms, with Han at 61% and Uyghurs at 50% satisfaction. Thermal comfort is a common concern, with about 50% Han and 40% Uyghurs satisfied against 26% and 29% dissatisfied, respectively. These results highlight the need for better temperature management in playgrounds (Figure 2).

In gray spaces, the Han group shows higher satisfaction with cultural displays (57.5%), plant forms (56.6%), and recreational facilities (56.0%). In contrast, the Uyghur group prefers plant forms (67.2%) and color (66.9%). The Han group’s satisfaction is fairly consistent, ranging from 46.0% to 57.0%. The Uyghur group has more varied satisfaction levels, with lower satisfaction in cultural displays (33.7%). Dissatisfaction is higher among Uyghurs for cultural displays (40.7%), seat materials (36.9%), and recreational facilities (31.3%), indicating a need for optimization in these areas. The Han group’s dissatisfaction is more pronounced with noise (21.6%) and spatial privacy (27.2%).

In green spaces, the Han group is most satisfied with cultural displays (67.4%) and recreational facilities (67.4%), while the Uyghur group prefers color (56.9%) and noise levels (53.3%). However, thermal comfort satisfaction is notably lower for both groups, at 43.4% for the Han and 33.9% for the Uyghur, with corresponding dissatisfaction rates of 30.4% and 32.7%, respectively. These findings highlight a need for enhanced temperature control in green space design. Overall, elements like cultural displays and recreational facilities are particularly appreciated, suggesting a focus on improving visual appeal in these areas.

In blue spaces, a key difference is seen in cultural displays: the Han group has a satisfaction rate of 54.7% with a dissatisfaction rate of 23.3%, while Uyghurs show 38.1% satisfaction and 25.1% dissatisfaction, indicating a need for more culturally tailored content. Both groups are satisfied with seating (Han 53.0%; Uyghur 46.3%) and plant forms (Han 52.4%; Uyghur 43.5%). However, color design and thermal comfort need improvement for both, highlighting the need for design adjustments to meet diverse preferences (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Statistical environmental factor indicators for four categories between Han and Uyghurs. The factors are arranged from highest satisfaction (top) to lowest satisfaction (bottom), reporting the percentage of satisfaction (red) and dissatisfaction (blue) for each factor.

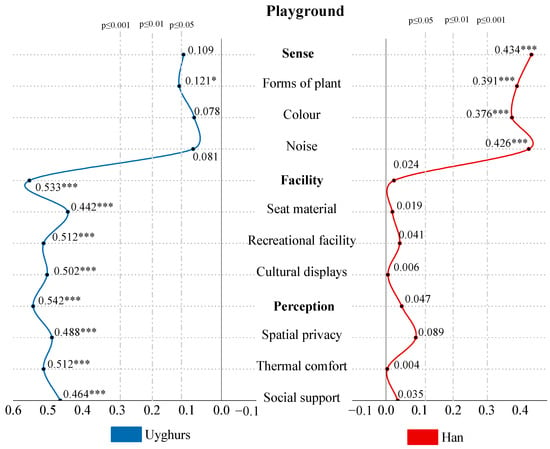

3.4. Correlations Between Environmental Satisfaction and Restorative Perceptions

In the playground, for the Han group, noise (r = 0.426), color (r = 0.376), and plant forms (r = 0.391) had the highest correlations with restorative perception, all significant at p < 0.001. Uyghurs showed a lower but significant correlation with plant forms (r = 0.121, p < 0.05). However, they had higher correlations with cultural displays (r = 0.502), recreational facilities (r = 0.512), and seat materials (r = 0.442) in the Facility dimension and social support (r = 0.464), thermal comfort (r = 0.512), and spatial privacy (r = 0.488) in the Perception dimension, all significant at p < 0.001. Overall, Uyghurs demonstrated a wider range of significant correlations, indicating greater cultural variation in environmental perception and satisfaction within the playground setting (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Statistical of the correlation between perceived restoration votes and environmental factor satisfaction in playgrounds. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. The width of the point to the vertical axis reflects the strength of the correlation.

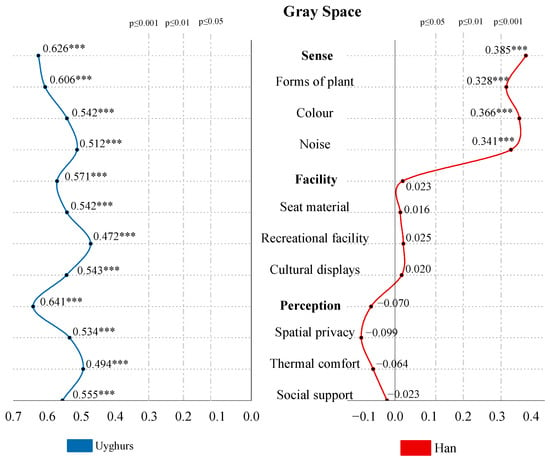

In gray spaces, the Uyghur group demonstrates significant positive correlations across all dimensions of sensory, facilities, and perception. The correlation coefficient for the sensory dimension is r = 0.626 (p < 0.001), indicating a higher sensitivity and demand for design elements within the plaza. In contrast, the Han ethnic group shows significant correlations only in the sensory dimension (r = 0.385, p < 0.001) and its sub-dimensions, such as noise (r = 0.341, p < 0.001), color (r = 0.366, p < 0.001), and forms of plant (r = 0.328, p < 0.001). No significant correlations were found in the dimensions of facilities and perception. This suggests that the Han ethnic group may have different expectations and needs regarding plaza spaces compared to the Uyghur group, or they may be less sensitive to these elements.

The Uyghur group exhibits a notably strong positive correlation (r = 0.641, p < 0.001) between the perception dimension and PRS, emphasizing the impact of their overall perception of gray spaces on their restorative experience. This includes factors like social support, thermal comfort, and spatial privacy. In contrast, the Han ethnic group lacks a significant correlation in this dimension, hinting at differing expectations or needs for restorative experiences in plaza spaces.

Both groups show positive correlations in the sensory dimension, with the Uyghur group particularly affected (r = 0.626, p < 0.001). This underscores the importance of sensory elements such as noise (r = 0.512, p < 0.001), color (r = 0.542, p < 0.001), and plant forms (r = 0.606, p < 0.001) for their restorative experiences. The Uyghur group also exhibits significant correlations with the facility dimension, particularly with cultural displays, recreational facilities, and seating materials, indicating these elements’ substantial influence on their restorative experience. In contrast, the Han group does not show significant correlations in the facility dimension, suggesting lower sensitivity to these aspects (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Statistical of the correlation between perceived restoration votes and environmental factor satisfaction in gray spaces. *** p < 0.001. The width of the point to the vertical axis reflects the strength of the correlation.

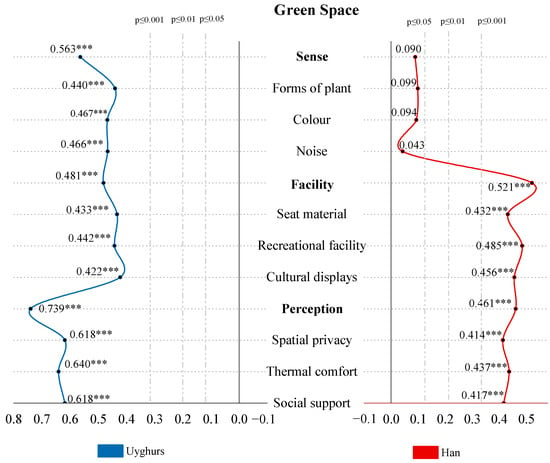

In green spaces, the Uyghur group exhibits a notably strong positive correlation with PRS in the perception dimension (r = 0.739, p < 0.001), indicating that their overall perception of the space significantly influences their restorative experience. Conversely, the Han group shows a weaker, yet still significant, positive correlation (r = 0.461, p < 0.001), suggesting varying expectations and needs for restorative experiences. The Uyghur group also demonstrates significant positive correlations with the sensory dimension (r = 0.563, p < 0.001) and its sub-dimensions, such as noise (r = 0.466, p < 0.001), color (r = 0.467, p < 0.001), and plant forms (r = 0.440, p < 0.001), whereas the Han group does not exhibit significant correlations. This suggests that the Uyghur group is more sensitive to visual and auditory elements in green spaces. Both groups show significant correlations with the facility dimension, with the Uyghur group having slightly higher correlations in cultural displays (r = 0.422, p < 0.001), recreational facilities (r = 0.442, p < 0.001), and seating materials (r = 0.433, p < 0.001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Statistical of the correlation between perceived restoration votes and environmental factor satisfaction in green spaces. *** p < 0.001. The width of the point to the vertical axis reflects the strength of the correlation.

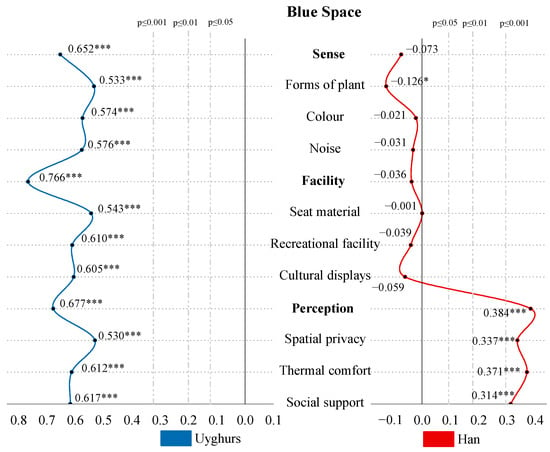

In blue spaces, the Uyghur ethnic group shows strong positive correlations with the PRS in the sense (r = 0.652, p < 0.001), facility (r = 0.766, p < 0.001), and perception (r = 0.677, p < 0.001) dimensions. This indicates a high sensitivity to design elements that significantly influence their restorative experiences. In contrast, the Han ethnic group shows a weaker but still significant correlation in the perception dimension (r = 0.384, p < 0.001), suggesting a less pronounced sensitivity compared to the Uyghur group.

Notably, the Uyghur group has high correlations in sub-dimensions such as noise (r = 0.576, p < 0.001), color (r = 0.574, p < 0.001), plant forms (r = 0.533, p < 0.001), cultural displays (r = 0.605, p < 0.001), recreational facilities (r = 0.610, p < 0.001), and seating materials (r = 0.543, p < 0.001). These correlations reflect greater expectations for the cultural and aesthetic aspects of the environment (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Statistical of the correlation between perceived restoration votes and environmental factor satisfaction in blue spaces. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. The width of the point to the vertical axis reflects the strength of the correlation.

3.5. Activity Effects on Perceived Restorativeness Between Han and Uighur

The Uyghur group had the highest scores for reading or socializing activities (M = 4.474), indicating a preference for obtaining restorative experiences through social interactions, which may be closely related to their cultural traditions and social structure. In contrast, the Han group scored the highest for contemplating the setting (M = 4.367), likely reflecting an appreciation for the restorative value of natural environments, influenced by their cultural emphasis on natural beauty and traditional garden art (Table 6 and Table 7).

Table 6.

Differences in restorative perception among different activity types for Han.

Table 7.

Differences in restorative perception among different activity types for Uyghurs.

Both groups had relatively lower PRS scores for physical activities, with the Han group M = 3.807 and the Uyghur group M = 4.022, suggesting that such activities may not be as effective in providing restorative experiences compared to appreciating the environment or engaging in social activities. This could be associated with the nature of physical activities, which might be perceived more as a form of physical exercise rather than a means of psychological recovery.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Spatial Types on Restorative Perception

The findings confirm that different spatial types significantly influence the restorative perception of college students, manifesting in various aspects. Green spaces stand out in terms of restorative perception, with the highest PRS score (4.438) and compatibility (ηp2 = 0.062, medium effect size) significantly affecting this perception. This aligns with previous research on the positive impact of natural elements on psychological restoration. The quiet atmosphere created by woodlands and vegetation in green spaces allows students to distance themselves from academic stress and achieve psychological relaxation.

Playgrounds have a relatively low restorative perception score (3.865), likely due to their functional orientation. While sports activities can help release students’ enthusiasm and relieve stress [87], the low restorative perception in this study might be because students focus on the sports behavior itself during exercise and pay less attention to the psychological restoration provided by the environment. Additionally, factors such as noise and frequent human activities in playgrounds can interfere with the restorative experience, as Stigsdotter noted in their research on the impact of environmental factors like noise on spatial perception and restorative experience [88].

Blue spaces score the highest in the “Being away” dimension ( = 0.029, medium effect size). The open water area and surrounding green belt make students feel a sense of detachment from their daily environment, which is consistent with Herzog et al.’s (2003) view that “Being away” is a crucial feature of restorative environments [5], helping students escape daily distractions and achieve psychological relief.

In gray spaces, the combination of hard surfaces and minimal greenery, as well as the layout of water bodies and surrounding vegetation in blue spaces, can lead to different satisfaction levels due to individual preferences for spatial functions and landscape aesthetics [89]. The similar satisfaction levels among students regarding sports fields and green spaces suggest that these areas effectively meet the basic needs of the majority. Specifically, the natural characteristics of green spaces align with the general preference for environments that promote relaxation.

4.2. Effects of Ethnicity on Perceived Restoration

Our study posits that ethnicity influences the restorative properties of campus outdoor space design. The findings reveal significant variations in the overall perceived restoration scores between Han and Uyghur groups across various campus outdoor spaces. Specifically, in green and gray spaces, Uyghur students consistently report higher restoration scores than Han students.

Uyghur students exhibit significantly higher values in gray, green, and blue spaces compared to Han students in terms of fascination scores. This can be attributed to the unique aesthetic preferences of Uyghur culture regarding colors and patterns, which make Uyghur students more likely to be attracted by the rich colors and diverse visual elements on campus, thereby enhancing their sense of restoration [90]. Additionally, studies on environmental perception in multi-ethnic areas have shown that color preferences in ethnic cultures are closely related to spatial attractiveness [91], further supporting the differences in perceived restoration among Uyghur students due to their distinct color aesthetics.

Han students tend to score higher on the “Extent” dimension in playgrounds and blue spaces. This preference can be explained by the Han culture’s emphasis on “harmony between humans and nature” and the importance placed on the practicality and functionality of spaces [92]. The diverse sports activities in playgrounds and the rich landscape elements in blue spaces likely meet these needs, resulting in higher scores. A deeper cultural explanation for these score differences among Han students in specific spaces can be found in historical and cultural analyses of traditional Han spatial concepts, which highlight the importance of practicality and harmony with nature [93].

Uyghur students exhibit a broader range of satisfaction in gray and blue spaces compared to Han students. This suggests that Uyghur students are more sensitive to spatial characteristics, and changes in the environment are more likely to influence their level of satisfaction. In contrast, Han students tend to prioritize the functionality of the space. Previous research has highlighted the role of cultural background in shaping individuals’ spatial perception, providing a theoretical basis for understanding these differences [94]. Additionally, empirical studies on the satisfaction of urban public spaces among people with diverse cultural backgrounds have shown that cultural factors play a crucial role in evaluating spatial satisfaction [95], further supporting the observed differences in campus space satisfaction between the two ethnic groups in this study.

Uyghur students report higher perceived recovery and attractiveness compared to Han students in gray spaces. This difference may stem from cultural, functional, and social differences between the two groups. Uyghur culture, which emphasizes collectivism and sociability [96,97], encourages students to use gray spaces for group interactions, providing emotional support and a sense of belonging that enhances their recovery perception. In contrast, Han students, influenced by the “harmony between humans and nature” concept, focus more on natural elements and experiential diversity—features that gray spaces may not fully provide, thus limiting their recovery perception. The social functions of gray spaces align well with Uyghur students’ needs, as their openness and inclusiveness facilitate group activities and enhance satisfaction and recovery potential. However, Han students may feel less supported due to the lack of natural integration and diverse experiences in gray spaces. Additionally, cultural differences lead to distinct preferences: Uyghur students value the social and cultural exchange functions of gray spaces, while Han students prioritize natural attributes and activity possibilities. This preference gap may reduce the recovery effect of gray spaces for Han students.

4.3. Ethnic Differences in Restorative Needs

Uyghur and Han groups exhibit significant differences in their restorative needs, reflected in their environmental perceptions and behavioral patterns across various types of spaces. Data indicate that the restorative perception of the Uyghur group is closely associated with multiple environmental factors, demonstrating considerable diversity. In contrast, the restorative perception of the Han group is primarily linked to sensory elements. However, in green and blue spaces, restorative needs are not solely driven by sensory elements, likely because natural spaces tend to emphasize the overall atmosphere rather than individual sensory stimuli.

Cultural displays exhibit significant ethnic differences, particularly in the restorative experiences of the Uyghur group. Specifically, cultural displays are highly correlated with the restorative experiences of Uyghurs in gray, green, and blue spaces. This correlation may stem from the key role that cultural displays play in enhancing cultural identity and psychological belonging among Uyghurs [98,99], which, in turn, influences their restorative perception. In contrast, the Han group does not show a significant correlation with cultural displays in these spaces. This may be attributed to the Han ethnic group’s majority status at the national level in China, coupled with their distinct cultural and psychological traits. The Han’s numerical dominance and cultural–social influence, combined with their unique characteristics, may influence the disparities in the relationship between cultural displays and restorative experiences observed in our study. For the Han group, restorative experiences are more influenced by other factors, such as sensory experiences or functional facilities. For the Uyghur group, heightened sensitivity to cultural displays may be related to their emphasis on cultural uniqueness, with cultural identity playing a vital role in shaping their restorative experiences [100,101]. This finding aligns with studies that highlight the role of cultural identity in influencing environmental preferences and psychological well-being [102,103].

4.4. Interactions of Activities and Spatial Features on Restorative Perception

Our results showed Han students exhibited higher restorative perception during contemplative activities, likely because the “sensory experience” in natural environments effectively restores attention and reduces mental fatigue. In contrast, Uyghur students showed higher restorative perception during reading/social activities, probably due to the strong social support provided by social interactions, which helps relieve stress and restore psychological resources. Contemplating the setting restores psychological resources by providing a sense of tranquility and relaxation, while reading/social activities relieve stress through emotional support and a sense of group belonging. In comparison, sports activities, although capable of relieving stress, primarily serve as physical exercise rather than direct psychological restoration. This intrinsic difference in activity types may explain why sports activities scored lower in restorative perception among both ethnic groups.

Cultural background may further strengthen the impact of activity types on restorative perception by influencing individuals’ psychological expectations and behavioral habits. Uyghur students are accustomed to obtaining psychological support through group interactions, while Han students are more likely to restore their sense of calm in natural environments. These cultural differences not only affect activity choices but may also influence their psychological expectations and satisfaction, thereby affecting their restorative perception.

The match between activities and spatial characteristics may significantly influence individual restorative perception. When the match is high, restorative perception is enhanced; otherwise, it may decrease. For example, social activities are better suited for open gray spaces, while nature watching activities are more appropriate for green or blue spaces. Spatial characteristics can guide the choice of activities, and the activities, in turn, affect individuals’ perception of spatial features, further strengthening or weakening restorative perception. Therefore, in campus space design, it is crucial to consider the match between activities and spatial characteristics.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the research sample focuses on Han and Uyghur students, without involving the restorative perceptions of students from other ethnic groups. Future research can expand the scope of the samples to cover more regions and ethnic groups to further validate the conclusions of this study. Second, the study primarily employs questionnaires and satisfaction assessments. Future research can combine field observations and behavioral experiments to more comprehensively reveal the impact mechanisms of campus spaces on college students’ restorative perceptions. Third, the sample size and the number of landscape plots may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should expand these results with larger, more diverse cohorts. Finally, our study primarily focused on self-reported perceived restoration through psychological scales but did not assess physiological indicators of actual restoration, such as cortisol levels and heart rate variability. This methodological gap should be addressed in future interdisciplinary studies that combine psychological and biometric approaches. Nonetheless, our findings provide empirical evidence to guide ethnoculturally inclusive campus landscape planning aiming to improve psychological restoration and well-being for students from all ethnic backgrounds.

5. Conclusions

Our findings underscore that ethnic differences significantly affect restorative perceptions and preferences in campus outdoor spaces. The results highlight that Han students typically prefer environments that facilitate contemplative engagement with nature and prioritize the functional integration of diverse landscape elements. In contrast, Uyghur students demonstrate heightened sensitivity to detailed spatial features, environmental aesthetics, and culturally resonant elements, with a particular preference for spaces supporting social interactions.

Accordingly, we propose culturally responsive design principles to guide multi-ethnic campus landscapes: (1) incorporating culturally significant Uyghur symbols, such as installations and narrative walls reflecting ethnic history and heritage, to foster psychological restoration rooted in cultural identity; (2) prioritizing multi-layered vegetation and tranquil natural soundscapes to cater to Han students’ appreciation of harmony between humans and nature while integrating culturally symbolic non-botanical elements to meet Uyghur students’ needs; (3) deploying flexible facilities (e.g., adaptable seating arrangements) and spatial designs (e.g., adjustable boundaries or varied topographies) to support diverse student activities and restorative experiences; (4) encouraging collaborative maintenance practices across ethnic groups to facilitate mutual understanding and cultural appreciation through active participation in landscape management, thereby fostering intercultural dialogue and community integration on campuses.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14040679/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D. and T.G.; formal analysis, C.D. and J.J.; methodology, T.G. and L.Q.; resources, T.G.; data curation, C.D.; writing—original draft, C.D.; writing—review and editing, T.G. and L.Q; visualization, J.J.; supervision, T.G. and L.Q. Investigation, W.Y., T.X. and F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 31971720 and 31971722.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Xinjiang Medical University for their assistance in the survey work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ahuvia, I.L.; Schleider, J.L.; Kneeland, E.T.; Moser, J.S.; Schroder, H.S. Depression self-labeling in U.S. college students: Associations with perceived control and coping strategies. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 351, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Luo, C.; Liu, L.; Huang, A.; Ma, Z.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, J. Depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms among Chinese college students: A network analysis across pandemic stages. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 356, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative Experience and Self-Regulation in Favorite Places. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 572–589. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Colleen Maguire, P.; Nebel, M.B. Assessing the restorative components of environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia: The human Bond with Other Species (1984); Harvard UP: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Hong, B. Effects of outdoor activity intensities on college students’ indoor thermal perception and cognitive performance. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S. Application of psychological elements in landscape design of public gardens. Rev. Argent. De ClínicaPsicológica 2020, 29, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, R. Social Development and Ethnic Relations in Chinese Minority Regions; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Niyazi, A.; Hang, S. A socio—cultural analysis of the spatial structure of the Uyghur traditional residential space in the Old City of Kashgar. J. Yunnan Minzu Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2017, 34, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties1. In Leinhardt S. Social Networks; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; pp. 347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, X. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, A.; Chen, X. Research on the Traditional Settlement Landscape based on Genetic Information—Turpan Mazar Village as Example. J. Xinjiang Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 33, 235–240, 252. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K. The Ideal Landscape-The Meaning of Feng-Shui; The Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K. Cultural variations in landscape preference: Comparisons among Chinese sub-groups and Western design experts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 32, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K. Landscape: Culture, Ecology and Perception: Volume 1; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Implements Major People-Oriented Policies to Promote Fair Higher Education AdmissionOpportunities. 2010. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s6192/s222/moe_1763/201008/t20100825_96553.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Simayi, Z. The Practice and Development of Policy in Ethnic Education of Xinjiang, 1st ed.; China Social Sciences Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, Y.; Li, Y. Chinese students’ science-related experiences: Comparison of the rose study in Xinjiang and Shanghai. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2015, 33, 218–236. [Google Scholar]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar]

- Ozguner, H. Cultural Differences in Attitudes towards Urban Parks and Green Spaces. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 599–620. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.; Chung, W. The impact of park environmental characteristics and visitor perceptions on visitor emotions from a cross-cultural perspective. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 102, 128575. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; An, L.; Hong, B.; Huang, B.; Cui, X. Cross-cultural differences in thermal comfort in campus open spaces: A longitudinal field survey in China’s cold region. Build. Environ. 2020, 172, 106739. [Google Scholar]

- Kley, S.; Dovbischuk, T. The equigenic potential of green window views for city dwellers’ well-being. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 108, 105511. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. Respecting Differences and Diversity and the Cultural Identity of Chinese Nation. J. Dalian Natl. Univ. 2011, 13, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R. Research on the Cultural Modernization of the Minority Nationality in Xinjiang. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2016, 37, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- He, X. On the Diversity and Unity of Chinese National Culture. 2010. Available online: http://www.hprc.org.cn/gsyj/whs/jiswmh/201003/t20100331_3981703.html (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Gulwadi, G.B.; Mishchenko, E.D.; Hallowell, G.; Alves, S.; Kennedy, M. The restorative potential of a university campus: Objective greenness and student perceptions in Turkey and the United States. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 187, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Meitner, M.J.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X. Characteristics of urban green spaces in relation to aesthetic preference and stress recovery. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tost, H.; Reichert, M.; Braun, U.; Reinhard, I.; Peters, R.; Lautenbach, S.; Hoell, A.; Schwarz, E.; Ebner-Priemer, U.; Zipf, A. Neural correlates of individual differences in affective benefit of real-life urban green space exposure. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1389–1393. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogerd, N.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Koole, S.L.; Koole, S.L.; Seidell J., C.; Maas, J. Greening the room: A quasi-experimental study on the presence of potted plants in study rooms on mood, cognitive performance, and perceived environmental quality among university students. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, J.A.; Gulwadi, G.B.; Alves, S.; Sequeira, S. The Relationship Between Perceived Greenness and Perceived Restorativeness of University Campuses and Student-Reported Quality of Life. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 1292–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Hartig, T.; Tilov, B.; Atanasova, V.; Makakova, D.R.; Dimitrova, D.D. Residential greenspace is associated with mental health via intertwined capacity-building and capacity-restoring pathways. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, C.W.; Quilliam, R.S.; Hanley, N.; Oliver, D.M. Freshwater blue space and population health: An emerging research agenda. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 140196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Huang, J.; Xiao, L. Research on Environmental Restorative Benefits of Planting Scenes in College Campus Living Quarters Based on Virtual Reality Technology. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein, D.E.; Troupin, D.; Segal, E.; Holzer, J.M.; Hakima-Koniak, G. Integrating ecological objectives in university campus strategic and spatial planning: A case study. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 190–213. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wu, S.; Qiu, J.; Wei, T. Sustainable University Campuses: Temporal and Spatial Characteristics of Lightscapes in Outdoor Spaces. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jae-Hyung, K. The relationship among perceived restorative environment, leisure satisfaction, resilience and psychological happiness in university students’ outdoor sports participation. J. Korean Soc. Sports Sci. 2016, 25, 425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, A. Demographic Groups’ Differences in Restorative Perception of Urban Public Spaces in COVID-19. Buildings 2022, 12, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xu, S.; Shi, R.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J. Exploring the impact of university green spaces on Students’ perceived restoration and emotional states through audio-visual perception. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, S. Impact of rural soundscape on environmental restoration: An empirical study based on the Taohuayuan Scenic Area in Changde, China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer-Grandbastien, A.; Burel, F.; Hellier, E.; Bergerot, B. A step towards understanding the relationship between species diversity and psychological restoration of visitors in urban green spaces using landscape heterogeneity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 195, 103728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.C.; Li, D.; Jane, H.A. Wild or tended nature? The effects of landscape location and vegetation density on physiological and psychological responses. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Gao, T.; Qiu, L. How do species richness and colour diversity of plants affect public perception, preference and sense of restoration in urban green spaces? Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 100, 128487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balai Kerishnan, P.; Maruthaveeran, S. Factors contributing to the usage of pocket parks―A review of the evidence. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Evaluating the Effect of Natural Soundscape on Attention Restoration and Pro-Environmental Behavior. Master Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nordh, H.; Østby, K. Pocket parks for people—A study of park design and use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Refshauge, A.D.; Grahn, P. Forest design for mental health promotion-Using perceived sensory dimensions to elicit restorative responses. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 160, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memari, S.; Pazhouhanfar, M.; Nourtaghani, A. Relationship between perceived sensory dimensions and stress restoration in care settings. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 26, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschardt, K.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Associations between park characteristics and perceived restorativeness of small public urban green spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 112, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Song, W.; Li, X. Coupling and Mutual Feedback of Urban Spatial Cognition-Preference-Behavior— Based on the Follow-up Survey of Graduate Students from the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. Trop. Geogr. 2021, 41, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. The Extension of Symbolic Meaning in the Era with the Integration of Design Aesthetics —Research and Design Application of Mongolian Decorative Patterns Based on Semiotics. Design 2024, 09, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, T. To Explore the Application of Traditional Color Aesthetics in Indoor Living Environment Design; Chinese national Expo: Shanghai, China, 2024; pp. 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Abulimiti, M. Environmental awareness and ecological concepts in Uyghur folk literature. Folk. Stud. 2015, 04, 98–102. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. Study on the Natural Ecology in Traditional Dwellings and Settlements of Ethnic Minorities in Yunnan. Urban. Archit. 2021, 18, 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y. People and Land: A New Perspective on Frontier History and Geography: A Review of Environmental Adaptation in the Process of Human-Land Relations in Zhuang Nationality. China’s Borderl. Hist. Geogr. Stud. 2014, 24, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.; Li, X. Ethnic Culture and Nature: Interactions in the Hani Terrace Landscape. In Landscape Ecology in Asian Cultures; Hong, S.K., Kim, J.E., Wu, J., Nakagoshi, N., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeill, T. Indigenous Cultures and Sustainable Development in Latin America; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotto, C.; Skounti, A. Intangible Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development: Inside a UNESCO Convention, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F.; Krettenauer, T. Editorial: Environmental Engagement and Cultural Value: Global Perspectives for Protecting the Natural World. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2853. [Google Scholar]

- Kothencz, G.; Kolcsár, R.; Cabrera-Barona, P.; Szilassi, P. Urban Green Space Perception and Its Contribution to Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, G.S.; Maciejewski, K. Reconciling community ecology and ecosystem services: Cultural services and benefits from birds in South African National Parks. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- McGinlay, J.; Parsons, D.J.; Morris, J.; Hubatova, M.; Graves, A.; Bradbury, R.B.; Bullock, J.M. Do charismatic species groups generate more cultural ecosystem service benefits? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.L.M. Customer Satisfaction, Service Quality and Perceived Value: An Integrative Model. J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 897–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The American Customer Satisfaction Index: Nature, Purpose, and Findings. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carrus, G. Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting urban and peri-urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Gao, T.; Qiu, L. Influence of Campus Environment on Psychological Restoration of College Students in the Post-Epidemic Era. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 30, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W.; Gärling, T. A measure of restorative quality in environments. Scand. Hous. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J. Developing the Restoration Environment Scale. China J. Health Psychol. 2010, 18, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, L.; Gao, T.; Gunnarsson, A.; Hammer, M.; von Bothmer, R. A methodological study of biotope mapping in nature conservation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistic Bureau of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Key Data from the Seventh National Population Census of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. 2021. Available online: https://tjj.xinjiang.gov.cn/tjj/tjgn/202106/4311411b68d343bbaa694e923c2c6be0.shtml (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Liang, Q.; Lin, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, F.; Yang, Y. The Impact of Campus Soundscape on Enhancing Student Emotional Well-Being: A Case Study of Fuzhou University. Buildings 2024, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Y. High or low? Exploring the restorative effects of visual levels on campus spaces using machine learning and street view imagery. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 88, 128087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Tokuhiro, K.; Ikeuchi, A.; Ito, M.; Kaji, H. Visual properties and perceived restorativeness in green offices: A photographic evaluation of office environments with various degrees of greening. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1443540. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, J.; Kim, H.J. The restorative effects of campus landscape biodiversity: Assessing visual and auditory perceptions among university students. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; He, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Ma, J. An Empirical Study on the Promotion of Students’ Physiological and Psychological Recovery in Green Space on Campuses in the Post-Epidemic Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oye, D.J. Assessment and Impact of Outdoor Seating Area in Campus Environment: A Case Study of Faculty of Environmental Sciences; University of Benin: Benin, West Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.M. Benchmarks: Sensing Therapeutic Landscape Qualities Associated with Seating Choice on Terrell Mall on the Washington State University Campus. Doctoral Dissertation, Washington State University, Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.F.; Wachs, S. Cyberbullying Involvement and Depression among Elementary School, Middle School, High School, and University Students: The Role of Social Support and Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathakrishnan, B.; Bikar Singh, S.S.; Yahaya, A. Perceived Social Support, Coping Strategies and Psychological Distress among University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Exploration Study for Social Sustainability in Sabah, Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Zeng, P.; Lei, L. Social support and cyberbullying for university students: The mediating role of internet addiction and the moderating role of stress. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 2014–2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Qiu, X.; Yang, X.; Qiao, Z.; Song, X.; Zhao, E. Social Support and Suicide Risk Among Chinese University Students: A Mental Health Perspective. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 566993. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Hong, B.; Du, M.; Yuan, T.; Wang, Y. Combined effects of visual-acoustic-thermal comfort in campus open spaces: A pilot study in China’s cold region. Build. Environ. 2022, 209, 108658. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Suo, J.; Zhao, J.R. Impact of building morphology and outdoor environment on light and thermal environment in campus buildings in cold region during winter. Build. Environ. 2021, 204, 108074. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Ye, S.; Wang, R.; Dong, F.; Feng, Y. Real-time indoor thermal comfort prediction in campus buildings driven by deep learning algorithms. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107603. [Google Scholar]

- Foellmer, J.; Kistemann, T.; Anthonj, C. Academic Greenspace and Well-Being—Can Campus Landscape be Therapeutic? Evidence from a German University. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Shi, B.; Gao, X. The way to relieve college students’ academic stress: The influence mechanism of sports interest and sports atmosphere. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Ekholm, O.; Schipperijn, J.; Toftager, M.; Kamper-Jørgensen, F.; Randrup, T.B. Health promoting outdoor environments—Associations between green space, and health, health-related quality of life and stress based on a Danish national representative survey. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38, 411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Nordh, H.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Holmqvist, K. Tracking Restorative Components: Patterns in Eye Movements as a Consequence of a Restorative Rating Task. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, R. Analysis of Uyghur traditional patterns and their application in textile design. J. Silk 2020, 57, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Li RY, M.; Li, R. Chromaticity Analysis on Ethnic Minority Color Landscape Culture in Tibetan Area: A Semantic Differential Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, J.; Ji, K. Harmony Between Humans and Nature—Natural and Practical Function. In A Study on the Concepts of Harmony Embodied in the Ancient Chinese Architecture; Li, L., Li, J., Ji, K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 55–114. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Cao, H. Historical Evolution and Reflections on “Harmony between Man and Nature”. Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2022, 12, 605–612. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, J. Research on the design and image perception of cultural landscapes based on digital roaming technology. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Huang, Y.; Guo, R. Visitors’ Behaviors and Perceptions of Spatial Factors of Uncultivated Internet-Famous Sites in Urban Riverfront Public Spaces: Case Study in Changsha, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdukeram, Z.; Mamat, M.; Luo, W.; Wu, Y. Influence of Culture on Tripartite Self-Concept Development in Adolescence: A Comparison between Han and Uyghur Cultures. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 116, 292–310. [Google Scholar]

- Mamat, M.; Huang, W.; Shang, R.; Zhang, T.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Luo, W.; Wu, Y. Relational Self Versus Collective Self: A Cross-Cultural Study in Interdependent Self-Construal Between Han and Uyghur in China. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 959–970. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J.S. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 499–514. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Soc. Psychol. Intergroup Relat. 1979, 33, 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Clothey, R.; McCommons, B. Uyghur students in higher education in the USA: Trauma and adaptation challenges. Diaspora Indig. Minor. Educ. 2022, 16, 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Clothey, R. Equity and Access to Higher Education for Rural Uyghur Students in China: A Consideration of Policy and Structural Barriers. Chin. Educ. Soc. 2024, 57, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; English, A.S.; Zheng, L.; Bender, M.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, J.; Ma, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, W. Longitudinal examination of perceived cultural distance, psychological and sociocultural adaptation: A study of postgraduate student adaptation in Shanghai. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2024, 103, 102084. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, H. Individuals’ Social Identity and Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Cross-Cultural Evidence from 48 Regions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).