Abstract

Landscape fragmentation as a process of landscape transformation affects the structure and composition of plant communities; however, relationships between fragmentation metrics and vegetation characteristics often remain weakly expressed and difficult to interpret, especially under conditions of multiple natural (wildfires, windstorms, pest outbreaks) and anthropogenic stressors (construction, forest management, agriculture). The aim of this study was to identify the sensitivity of forest community characteristics to landscape fragmentation metrics using methods that are effective at low correlation coefficients. The study analyzed 1694 vegetation relevés of forest communities in the center of the Russian Plain in the territory of the Moscow region. Seven uncorrelated metrics were calculated using the moving window method (2000 m) in Fragstats 4.3. The relationships between selected metrics and 20 community characteristics were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation method, assessment of statistically significant differences between classes, and testing for non-linear interactions. The species richness and Shannon index showed no correlation with fragmentation for tree and herb layers; however, the composition of ecological–coenotic groups demonstrated high sensitivity. The proportion of boreal and oligotrophic species, as well as the moss layer abundance, increased with increasing patch size, while nemoral and adventive species dominated in small-contrast patches. Results showed that fragmentation leads to asynchronous responses from ecosystem components, reducing correlations between structure and functioning. The conservation of large connected forest patches is critical for preserving the boreal–oligotrophic complex and moss layer, and is a priority task for climate adaptation. The robustness of the findings is supported by the extensive number of analyzed vegetation relevés. The multi-method approach demonstrated effectiveness in identifying significant ecological patterns under conditions of high multifactorial impact, emphasizing the need for a functionally oriented approach to managing fragmented temperate forests.

1. Introduction

Landscape ecology studies how the spatial organization of habitats affects living organisms and ecosystem processes [1,2,3,4,5]. This approach is critical for understanding how fragmentation—the division of continuous forests into separate patches—affects biodiversity and ecosystem functioning [6]. This question is especially relevant for temperate forests, which have experienced intensive anthropogenic impact for centuries. Landscape ecology is oriented toward the application of spatial geographic analysis to living environment objects, primarily at the metapopulation level, with the main goal being the scientific justification of nature management decisions. The foundation of landscape ecology is based on island biogeography theory, and its significant application is, in most cases, realized through the design of ecological networks [7]. At the same time, the landscape ecology approach to modeling spatial structures complements and often contrasts with the classical traditions of Russian landscape science, which considers processes as factors of spatial differentiation.

Since the late twentieth century, methods for the quantitative assessment of the fragmentation of minimally disturbed forest ecosystems undergoing anthropogenic impact have been actively developed. The application of fragmentation metrics—such as area, perimeter, degree of adjacency, and contrast—allows for the identification of features of morphological structure and mosaics of land cover. Fragmentation metrics are quantitative parameters that measure how strongly a landscape is divided into separate patches. For example, edge density (ED) shows the number of ecotones between a forest and open territory (more edges = more external influence), and edge contrast (ECON) characterizes how strongly these edges differ from neighboring territories. Research on fragmentation in Russia remains limited. For example, for the Valdai National Park territory, a general landscape fragmentation index (0.18–0.24) was calculated, and it was established that the average area of a homogeneous contour is 1.9 hectares. The study demonstrates the application of fragmentation metrics for reconstructing historical changes in forest cover and assessing the sustainability of anthropogenic mosaics in forest–field–meadow landscapes [8]. Another study analyzed the dynamics of forest fragmentation around Moscow for the period 1991–2001 using Landsat data. Forest cover losses ranging from 14 to 35% were identified by district, with the fragmentation process documented as a result of post-Soviet urbanization. The study demonstrates the application of remote sensing and landscape metrics for analyzing fragmentation under conditions of rapid urban development [9].

Numerous studies have confirmed fragmentation parameters’ relationships with species [9,10,11] and phylogenetic diversity [12,13], as well as with forest management characteristics [14,15,16] and the conservation value of territories [17]. A meta-review shows that for 70% of remaining forests, the edge effect is 1 km, and fragmentation can reduce biodiversity by 13–75% and seriously disrupt key ecosystem functions [18], including animal behavior [19,20,21] and resilience to hazardous natural events [22]. On the one hand, metrics of natural systems may indicate different geneses, conditioned by soil–geomorphological or hydrological processes. On the other hand, they may indicate the degree and character of anthropogenic transformation and the state of ecological and supporting functions—ecological cores and corridors [23]. At the same time, the use of landscape–ecological metrics is associated with a number of limitations—sensitivity to spatial resolution and scale, mutual correlation, and ambiguous interpretation [24,25,26,27,28]. Based on this, we planned our study to further search for adequate metrics of vegetation structure to be used together with fragmentation analysis.

Landscape fragmentation is not limited to its impact on natural communities—it also significantly disrupts critical ecosystem services necessary for human life [29]. Why is this important? The boreal forest stores one-third of all C in terrestrial biomes [30,31,32]. When a forest becomes fragmented, this capacity is lost. Research shows that forest degradation led to a loss of carbon storage of 7.4–102.68 Pg [33]. Beyond carbon cycling, hydrological functions and biogeochemical flows are also affected. Forest landscape connectivity, by contrast, promotes the preservation of ecosystem services, including the regulation of hydrological regimes, the accumulation of carbon in living biomass and soils, the maintenance of pollination, and pest control [34]. For the most fragmented ecosystems located within the zone of various levels of anthropogenic impact—such as the forests of the Moscow region—there is still a need to develop methodological approaches that can identify relationships between landscape spatial structure and qualitative composition of plant communities under conditions of high ecological complexity [35].

The Moscow region serves as a classic example of a fragmented temperate landscape. Over 500 years, intensive logging and the expansion of settlements and agricultural lands have led to the division of forests into hundreds of small patches. In contrast to pristine forests, young secondary forests with altered species composition now dominate [36]. Widely distributed forestry practices have significantly altered the ecological–coenotic range of zonal coniferous and broad-leaved coniferous forests [37,38]. This makes the Moscow region an ideal laboratory for studying how long-term fragmentation affects forest ecosystems.

Aim of the study: To identify which characteristics of forest communities are most sensitive to fragmentation, using methods that are effective under conditions of high complexity (when multiple factors act simultaneously). We hypothesize that the species richness (number of species) may remain relatively stable, but the specific species composition will change depending on the size and shape of forest patches.

The study results suggest that the conservation of large, connected forest patches is critical for maintaining the boreal–oligotrophic complex. The obtained data confirm the need for a functionally oriented approach to assessing fragmentation and managing temperate forests in the context of climate adaptation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

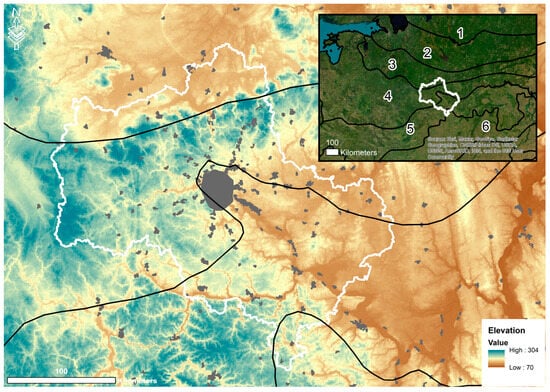

The Moscow region is located in the central part of the Eastern European (Russian) Plain—54°12′–56°55′ N, 35°10′–40°15′ E—covering an area of 4.43 million ha (excluding Moscow) (Figure 1). By its natural conditions, the Moscow region is crossed by several important natural and botanical–geographical boundaries that pass through the territory, caused by climate gradients and the heterogeneity of glacial and fluvioglacial deposits formed during Quaternary glaciations [39]. According to the Köppen climate classification, the territory belongs to the Dfb—Cold, no dry season, warm summer [40]. According to a schematic map of climate regions, the Moscow region is classified as a moderately continental area [41,42]. The mean annual air temperature is 2.7–3.8° C, and precipitation is 479–644 mm according to our regional averaging of Worldclim [43]. The terrain is gently rolling, with heights varying from 90 to 320, with an average of 174 m above sea level, and the mean slope is 2.06° (0–30.9°).

Figure 1.

Study area: white line—Moscow region borders; black line—forest zones according to [44]: 1—middle taiga, 2—south taiga, 3—mixed forests (coniferous), 4—mixed forests (coniferous/broadleaf), 5—broadleaf, 6—forest-steppe; light gray—important urban areas.

The main part of the Moscow region lies within the zone of broad-leaved coniferous forests. In the south of the region is the boundary with the broad-leaved zone [45,46,47]. The change in zonal boundaries is related to the changes in geomorphological conditions caused by the position of the region with respect to the Moscow glaciation boundary: weakly drained loamy plateaus in the west are replaced toward the east by well-drained, eroded interfluve areas. The Moscow region is characterized by both broad-leaved coniferous forests and spruce subnemoral and boreal forests [48]. On watersheds, complex spruce forests and small-leaved forests dominate. Broad-leaved forests—oak (Quercus robur) and lime (Tilia cordata), genetically linked with complex spruce forests—occur on elevated surfaces under more favorable forest-growing conditions, as well as fragmentarily on slopes of hills and river terraces. Almost everywhere under spruce canopies, typical coniferous forest species combine with nemoral broad herbs. Boreal types of spruce forests are distributed insignificantly. Pine stands on water divides, as a rule, have artificial origins. The dominant vegetation species are provided in Supplementary Materials.

2.2. Methods

Field phytosociological data collection was carried out in 2006–2019 on forest patches without obvious signs of logging and other anthropogenic disturbances. Relevés were compiled according to the standard methodology on an area of 400 m2 [49]. Total number of relevés was 1694. On each plot, complete species composition and vertical structure were recorded. Species cover is given in percentages. When distinguishing layers, the following designation is accepted: A—tree layer; B—regeneration and shrub layer; C—herb–shrub layer; and D—moss layer. In analyzing relationships between fragmentation metrics and structural–functional characteristics of communities, both parameters directly measured in the field (phytocoenotic and forest management characteristics) and calculated indicators derived from them were considered: diversity indices and representation of ecological–coenotic groups of species:

- Height (m) and diameter (cm) of layer A;

- Projective cover (%) of layers A, B, C, D;

- Species diversity indices (species richness and Shannon index) for vegetation of layers A, B, C, D;

- Representation of ecological–coenotic groups for vegetation of layers A, B, C, D (%): boreal, nemoral, wet herb, nitrophilous wet herb, oligotrophic, edge, adventive, meadow.

For the calculation of species diversity indices, we used data on all species’ projective cover and the following approach. Species richness (V): The total number of species within each layer or across the entire community. Shannon index (H′):

where pi is the relative projective cover of the ith species (pi = ni/N), ni is the cover of species i, and N is the total projective cover for all species in the community.

For the calculation of fragmentation metrics, a map of forest formations obtained in an earlier study was used [38]. Forest formations were aggregated into a single “forest” layer with 60 m resolution. Fragmentation metrics at the class level were calculated using the moving window method (round, size 2000 m) in the Fragstats 4.3 software application [50]. All available class metrics were calculated. Based on the correlation matrix of metrics, only metrics correlating less than 0.8 by absolute value were retained (Spearman correlations).

Points from relevés where structural–functional characteristics of forest communities were measured and calculated were overlaid with fragmentation rasters, from which the values of corresponding metrics were extracted. Based on the obtained integrated table, a Spearman correlation matrix was formed, and restructuring was performed using two-way joining, allowing the grouping of similar correlation patterns. Correlations with significance levels of p < 0.005 were considered reliable. Identified relationships were additionally checked for statistically significant differences between classes and their quantitative representation (at a 0.95 confidence interval), and the possibility of non-linear (quadratic) dependence between fragmentation metrics and structural–functional characteristics of forest communities was clarified. Listed characteristics were coded for assessing integral relationship score: presence of significant correlation (p < 0.005)—1 score; presence of two significantly different classes—1 score; presence of more than 2 different classes—2 scores; possible manifestation of non-linear interaction—1 score. The final correlation matrix between fragmentation metrics and structural–functional characteristics of forest communities was optimized according to interaction patterns and relationship scores.

3. Results

A total of 106 fragmentation metrics were calculated. Correlations less than 0.8 by absolute value are observed for 7 fragmentation metrics—area, edge density (ED), edge contrast (ECON), normalized landscape shape index (NLSI), number of patches (NP), Euclidean nearest neighbor (ENN), and proximity (PROX) (Table 1, Supplementary Materials).

Table 1.

Fragmentation metrics with correlations less than 0.7 by absolute value (Spearman correlations).

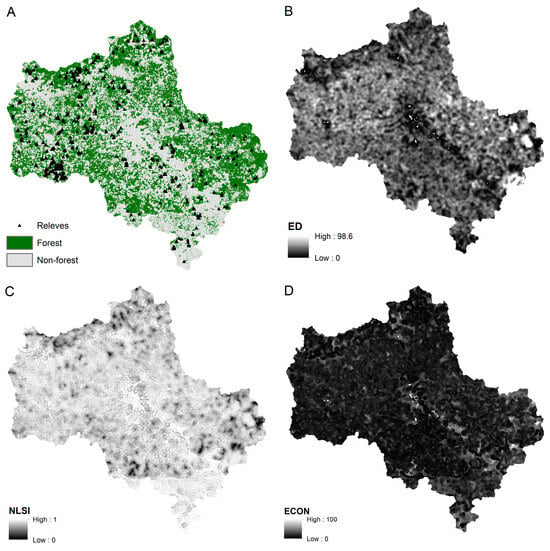

The physical meanings of these metrics are described in detail in a number of studies, i.e., ref. [51]. It is important to note that the ED and ECON metrics are directly related to the nature of forest community boundaries and show the number and contrast of ecotone habitats. NLSI is the number of ecotone habitats normalized to the area of forest within the moving window, in other words, the complexity of community shape. PROX is the homogeneity of the environment in which the forest community is located. Some fragmentation metrics are shown in Figure 2. High-detail figures are provided in Supplementary Materials.

Figure 2.

(A)—Forest and non-forest land cover; triangles indicate vegetation relevés locations. Fragmentation metrics of forest patches: (B)—Edge density (ED) metric, (C)—Edge contrast (ECON) metric, (D)—Normalized landscape shape index (NLSI) metric. Scale 1: 3,000,000.

In Table 2, an optimized correlation matrix between the fragmentation metrics and structural–functional characteristics of forest communities is presented. A full correlation matrix is provided in Supplementary Materials. Some community characteristics showed no significant correlations with fragmentation metrics at a p < 0.005 significance level—specifically, the species richness and Shannon index for the tree (layer A) and herb (layer C) layers, as well as the Shannon index for regeneration layer B. This absence of relationships was consistent across all seven fragmentation metrics examined.

Table 2.

Optimized correlation matrix between fragmentation metrics and structural–functional characteristics of forest communities.

Based on the correlations, the fragmentation metrics divide into three recognizable groups: 1. size metric (AREA), 2. dissection metrics (ED, ECON, NP, PROX), and 3. aggregation or shape metric (NLSI). The community characteristics divide into three distinct groups based on their correlation patterns with the fragmentation metrics. First, the site quality of the tree layer combined with the projective cover of the herb layer showed weak but significant correlations with certain metrics. Second, the proportion of boreal and oligotrophic species, along with the richness and diversity indices of the moss layer (D), demonstrated the strongest and most consistent sensitivity to fragmentation. Third, nemoral species dominance, along with that of nitrophilous wet herb and adventive species, showed inverse correlation patterns to the boreal complex, with corresponding relationships to the projective cover of the understory layer B.

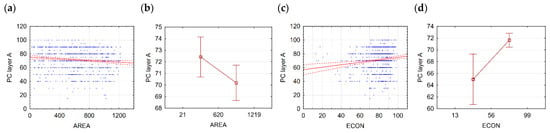

Relationships between the site quality of layer A and fragmentation metrics are generally weak but significant. For example, the correlation between AREA and the projective cover of layer A equals −0.11, while no significantly different classes are formed. But the correlation between ECON and the projective cover of layer A equals 0.14, while two significantly different classes of forest communities are formed (Table 2, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PC Layer A and AREA: (a)—scatterplot; (b)—means plot. PC Layer A and ECON: (c)—scatterplot; (d)—means plot; scatterplot explanations: blue dots—observations, solid red line—linear or quadratic fit, dashed red line—confidence interval 0.95; means plot explanations: middle point—mean, whiskers confidence interval 0.95.

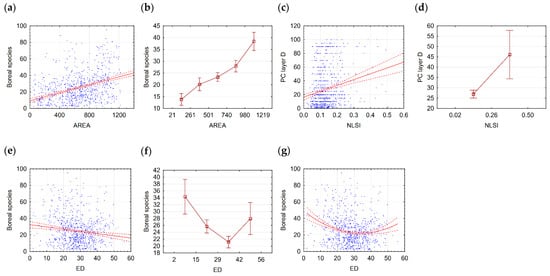

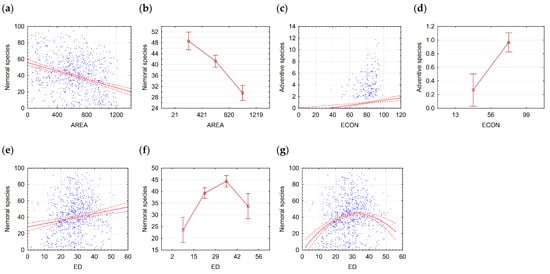

The proportion of boreal and oligotrophic species and the moss layer characteristics have the best correlations with fragmentation metrics. Correlations with the AREA metric were the strongest, ranging from 0.23 to 0.38 for species proportions. For the relationship between the boreal species proportion and AREA, the analysis identified five significantly different patch-size classes, demonstrating a robust gradient response (Table 2, Figure 4a,b). Notably, the relationship between the boreal species proportion and ED metric demonstrated pronounced signs of non-linear (quadratic) interaction (Figure 4e–g), suggesting a threshold response pattern where boreal species initially decrease with increasing edge density before stabilizing at high fragmentation levels.

Figure 4.

Boreal species and AREA: (a)—scatterplot; (b)—means plot. PC Layer D and NLSI: (c)—scatterplot; (d)—means plot. Boreal species and ED: (e)—scatterplot; (f)—means plot; (g)—scatterplot (quadratic); scatterplot explanations: blue dots—observations, solid red line—linear or quadratic fit, dashed red line—confidence interval 0.95; means plot explanations: middle point—mean, whiskers confidence interval 0.95.

The moss layer D exhibited similarly strong responses to fragmentation, with richness and projective cover increasing significantly with patch size (r = 0.23–0.28 with AREA). Four significantly different classes were distinguished for moss layer richness in relation to the AREA fragmentation metric. The Shannon index for the moss layer also showed a positive correlation with AREA (r = 0.22), indicating both higher species diversity and greater representation of multiple moss species in large, consolidated patches. The oligotrophic species proportion showed identical correlation patterns to boreal species, with a particularly strong relationship to AREA (r = 0.23) and significant quadratic interactions with the ED metric.

The nemoral species complex exhibited opposite response patterns to fragmentation compared to the boreal–oligotrophic complex. The nemoral species proportion was inversely correlated with AREA (r = −0.29) and positively correlated with ED (r = 0.17) and ECON (r = 0.29). Three significantly different classes were identified in the AREA relationship (Table 2, Figure 5a,b), with nemoral species increasing in small, fragmented patches. The non-linear relationship with ED showed the opposite sign compared to the boreal species dependence (Figure 5e–g), suggesting fundamentally different habitat requirements for these competing ecological complexes.

Figure 5.

Nemoral species and AREA: (a)—scatterplot; (b)—means plot. Adventive species and ECON: (c)—scatterplot; (d)—means plot. Nemoral species and ED: (e)—scatterplot; (f)—means plot; (g)—scatterplot (quadratic); scatterplot explanations: blue dots—observations, solid red line—linear or quadratic fit, dashed red line—confidence interval 0.95; means plot explanations: middle point —mean, whiskers confidence interval 0.95.

Adventive (invasive) species demonstrated similarly strong sensitivity to fragmentation (overall relationship score of 1.8), with a particularly strong inverse correlation to AREA (r = −0.32) and positive correlation to ECON (r = 0.28) and NP (r = 0.27). Notably, adventive species were more abundant in small, contrast-rich, edge-dominated patches. Nitrophilous wet herb species showed intermediate response patterns (relationship score 1.3), correlating negatively with AREA (r = −0.20) but showing variable relationships with other metrics.

The pattern of correlations revealed that the fragmentation metrics naturally cluster into three functional groups based on ecological meaning. Size metrics (AREA) primarily capture effects of patch size on species composition. Dissection metrics (ED, ECON, NP, PROX) measure landscape complexity and edge influence. Shape metrics (NLSI) characterize configuration complexity. Correspondingly, community characteristics showed differentiated responses to these metric groups, with the greatest sensitivity concentrated in the ecological–coenotic group composition and moss layer characteristics.

Overall relationship scores (calculated from correlation strength, class differentiation, and non-linearity indicators) were highest for the metrics AREA (score 2.3), ED (1.9), and ECON (1.8), and for the community characteristics boreal species proportion (2.5), nemoral species (2.3), richness and projective cover of moss layer (1.8 each), and oligotrophic species (1.2). These relationship scores confirm that the ecological–coenotic group composition and moss layer properties are the most effective indicators of landscape fragmentation effects in temperate forests.

4. Discussion

The low correlation coefficients we obtained (|r| < 0.30) despite high statistical significance reflect the multidirectional action of multiple stressor factors, as shown in several studies. For example, aboveground and belowground ecosystem components often demonstrate decoupled responses to global changes [52]; ecosystem degradation leads to the weakening of relationships between components, acting as “noise” when attempting to predict ecosystem functioning [53]. Among other examples of stressors’ impact on ecosystem relationships are connectance and the availability of water resources [54], pesticides [55], and habitat loss [56]. Moreover, fragmentation as a process and as a result itself is such a stress factor and leads to an intensification of the decoupling between the functioning of different ecosystem components: with decreasing patch size, correlations between biodiversity, carbon storage, aesthetic value, and forest management value decrease [57]. This clearly demonstrates how fragmentation generates contradictory signals when attempting to assess the relationship between ecosystem structure and functioning. Finally, the most notable result of fragmentation—the increase in ecotone proportion—leads to decreased explained variation—at ecosystem boundaries (ecotones), spatial structure becomes independent from the surrounding environment, disrupting correlations between ecosystem components [58].

Our research does not contradict the critically important principle: when fragmentation, degradation, climate change, and other disturbances occur, ecosystem components (soil, vegetation, microbial communities, and aboveground and belowground biota) respond asynchronously and independently of each other. This decoupling reduces correlations between structure and functioning, introducing significant “noise” when attempting to measure ecosystem processes and predict ecosystem responses to external impacts. Certainly, the planning of field studies should take greater account of the significance of this factor, and the transport accessibility of ecosystems should not generate a large volume of ecotone relevés.

The most pronounced relationship with fragmentation metrics was found for the proportion of boreal and oligotrophic species, as well as the characteristics of the moss layer (D). These components of forest communities are critical for the carbon cycle, since boreal forests and raised bogs represent some of the most important terrestrial carbon storage areas [59,60]. Our results show that the conservation of large, connected forest patches (high AREA values, low ECON values) promotes the preservation of the boreal–oligotrophic complex and, consequently, carbon sequestration potential of ecosystems.

At the global level, it has been shown that the loss of biodiversity from forest fragmentation can lead to a reduction in carbon storage by 7.4–103 Pg, depending on the scale of degradation [33]. For temperate forests, including forests of the Moscow region, an additional risk factor is the long history of anthropogenic impact on ecosystems [36]. The moss layer, which demonstrates increasing richness and projective cover with increasing patch size in our study, is the primary accumulator of carbon in the soils of boreal and subarctic forests [61]. Furthermore, the moss layer, due to its physiology, is an indicator of the long-term sustainable existence of boreal forests and even serves as a driver of ecosystem services—the regulation of soil climate and control of nutrient cycling (especially nitrogen) determine the successful germination of coniferous plants, and regulate the water cycle [62]. Despite their high capacity for spore dispersal, mosses lag behind climate change. By 2050, models predict the loss of ~40% of the range for arctic–alpine species with a simultaneous colonization of only 9% of new suitable habitats. In this context, integrated approaches are necessary: the conservation of current moss ecosystems and improvement of landscape connectivity in the face of rapid climate shifts [63]. Thus, our research results support the need for the conservation of large forest patches as an element of climate adaptation strategy [18].

An important finding was the absence of relationships between the fragmentation metrics and species richness indicators, as well as the Shannon index for the tree and herb layers. However, the composition of the ecological–coenotic groups demonstrates the greatest sensitivity to fragmentation among all measured characteristics. A global study combining data on the distribution of 4006 plant and animal species from 37 ecosystems worldwide showed that although fragmentation reduces alpha-diversity (−13.6%), the increase in beta-diversity is insufficient to compensate for losses at the landscape level [64]. Our results are consistent with this conclusion: species composition is sensitive to fragmentation, while overall richness remains relatively stable. Another important aspect is that fragmentation creates edge effects affecting microclimate, hydrology, and nutrient accumulation. Adventive (invasive) species more successfully colonize disturbed, fragmented habitats. Study results are consistent with the finding that multifactorial impacts in fragmented landscapes change not so much the number of species as their functional composition [29,65].

The sensitivity of ecological–coenotic groups to fragmentation has important practical significance for forest management and nature conservation policy. The division of plant communities into boreal–oligotrophic and nemoral complexes allows considering them as indicators of the state of ecosystem functions and services [37]. Boreal communities, with a developed moss layer and low soil nitrogen content, serve as markers for carbon conservation and the preservation of the natural hydrological regime and nutrient circulation regime. Conversely, an increased proportion of nemoral, nitrophilous, and adventive species indicates actively occurring processes of community transformation related to fragmentation, anthropogenic changes in the nutrient cycling regime, and climate change. In the temperate zone, where forest landscapes have historically undergone intensive anthropogenic pressure, adaptive management should be directed toward maintaining ecosystem functionality and supporting its services, rather than only maximizing species richness. We believe that the manifestation of quadratic relationships between the structural–functional characteristics of communities may correspond to the law of the optimum or ecological niche theory. Quadratic dependencies reflect the balance between stochastic and deterministic processes in species niches, confirming the central principle of ecological theory regarding non-linear relationships in community structuring [66,67].

These results contrast with the classical study [68], which demonstrated the existence of clear fragmentation threshold values at 30% and 70% forest cover for maximizing biodiversity in tropical landscapes in Brazil. In contrast to tropical ecosystems, where a sharp decline in alpha-diversity is observed at forest cover below 30%, the temperate forests of Central Russia demonstrate more gradual and complex response patterns. Our data show that species richness does not correlate with fragmentation metrics, while ecological–coenotic group composition shows maximum sensitivity—boreal species and the moss layer increase in large patches (high AREA), while nemoral and adventive species dominate in small-contrast patches (high ED, ECON). This partially confirms the conclusions [69] that fragmentation per se increases gamma-diversity but reduces the abundance of specialized species. The critical difference in our research is that we found no universal optimal fragmentation levels applicable to all ecosystem components simultaneously—each ecological–coenotic group demonstrates a unique response pattern, confirming the need for a functionally oriented approach to managing fragmented temperate forests under the conditions of their long anthropogenic history.

The study employed a combination of correlation analysis (Spearman correlation), testing for statistically significant differences between classes, and examination of non-linear interactions. Despite the effectiveness of this approach, such a methodology may have certain limitations. Synthesizing results from different methods presents a significant challenge. If methods yield contradictory or incompatible results, it is difficult for researchers to create a single coherent interpretation. Many so-called “mixed methods” studies actually represent separate quantitative and qualitative investigations that are scarcely integrated with one another [70]. Interpretation of the qualitative components of the multi-method approach can be subjective, particularly if qualitative data disproportionately influences the final conclusions, potentially skewing overall research results in favor of particular perspectives [71,72]. Assessment of the validity of multi-method research remains a subject of debate.

5. Conclusions

This study established that the structure of plant communities retains high sensitivity to fragmentation even under multifactorial landscape impacts. Based on an analysis of 1694 vegetation relevés, the following main results were obtained.

Fragmentation affects primarily the composition of plant communities, rather than overall species richness. The species richness and Shannon index showed no relationship with fragmentation metrics for tree and herb layers; however, the composition of ecological–coenotic groups demonstrated maximum sensitivity to fragmentation impact. Boreal and oligotrophic species, as well as well-developed moss layers, increase their proportion in large, low-contrast forest patches (high AREA values, low ECON values). Conversely, nemoral and adventive species dominate in small and contrast patches (high ED, ECON), indicating the process of the nemoralization of communities with the participation of alien species.

The obtained results confirm a critically important principle: during fragmentation, ecosystem components respond asynchronously, leading to reduced correlations between ecosystem structure and functioning. This decoupling, acting as “noise,” complicates the prediction of ecosystem processes. However, identified non-linear interactions and the differentiated responses of ecological–coenotic groups indicate the possibility of conditional optimal fragmentation levels for individual ecosystem components.

The conservation of large forest patches is a priority task for climate adaptation. The moss layer, serving as the primary accumulator of carbon in boreal forest soils and an indicator of their long-term sustainability, is preserved primarily in large, connected forest patches. The boreal–oligotrophic species complex serves as a marker for carbon conservation and natural hydrological regime, while an increase in the proportion of nemoral, nitrophilous, and adventive species indicates the transformation of communities caused by fragmentation and anthropogenic impact.

The multi-method approach applied (rank correlation, analysis of differences between classes, testing for non-linear interactions) demonstrated high effectiveness in identifying significant ecological patterns under conditions of high multifactorial impact, even at low correlation coefficients. This underscores the need for a functionally oriented approach to the assessment of fragmentation in temperate forests.

The monitoring of ecological–coenotic group composition is recommended as an early indicator of fragmentation impacts on ecosystem functions and services. Further research should integrate data on soils, land-use history, and climate to clarify mechanisms of fragmentation impact and quantify the influence of multiple stressors under conditions of the long anthropogenic history of temperate forest ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122441/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K.; methodology, I.K., T.C. and N.B.; validation, T.C.; formal analysis, I.K.; investigation, I.K., T.C. and N.B.; resources, T.C.; data curation, I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.; writing—review and editing, I.K. and T.C.; visualization, I.K.; supervision, T.C.; project administration, T.C.; funding acquisition, T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The core of this research was conducted as part of the RSF project (No 24-17-00120) (field research, analytical work, statistical data analysis). Methodological research was supported by the state research task (theme No. 1022033100172-2-1.6.19) of the A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution RAS.

Data Availability Statement

The research data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Forman, R.T.T.; Godron, M. Landscape Ecology; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 619, ISBN 978-0-471-87037-1. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, R. Land Mosaics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-521-47980-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, S.T.; Cadenasso, M.L. The Ecosystem as a Multidimensional Concept: Meaning, Model, and Metaphor. Ecosystems 2002, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, M.R. Fostering Academic and Institutional Activities in Landscape Ecology. In Issues in Landscape Ecology; Wiens, J.A., Moss, M.R., Eds.; International Association for Landscape Ecology (IALE), University of Guelph: Guelph, ON, Canada, 1999; pp. 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, A. Principles and Methods in Landscape Ecology; Ecological Sciences; Chapman & Hall: London, UK; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; Volume 21, ISBN 0-412-73040-5. [Google Scholar]

- Хoрoшев, А.В. Пoлимасштабная Организация Геoграфическoгo Ландшафта; Toвариществo научных изданий KMK: Moscow, Russia, 2016; ISBN 978-5-7707838-1-2. [Google Scholar]

- Macarthur, R.H.; Wilson, E.O. The Theory of Island Biogeography; REV-Revised; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-691-08836-5. [Google Scholar]

- Belonovskaya, Y.A.; Krenke, A.N.; Tishkov, A.A.; Tsarevskaya, N.G. Natural and Anthropogenic Fragmentation of Vegetation of Valday Lake Area. Izv. Ross. Akad. Nauk. Seriya Geogr. 2014, 5, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boentje, J.P.; Blinnikov, M.S. Post-Soviet Forest Fragmentation and Loss in the Green Belt around Moscow, Russia (1991–2001): A Remote Sensing Perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 82, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munguía-Rosas, M.A.; Montiel, S. Patch Size and Isolation Predict Plant Species Density in a Naturally Fragmented Forest. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrášová-Šibíková, M.; Bacigál, T.; Jarolímek, I. Fragmentation of Hardwood Floodplain Forests—How Does It Affect Species Composition? Community Ecol. 2017, 18, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Feeley, K.J.; Wu, J.; Xu, G.; Yu, M. Determinants of Plant Species Richness and Patterns of Nestedness in Fragmented Landscapes: Evidence from Land-Bridge Islands. Landsc. Ecol. 2011, 26, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Rivas, A.; Munguía-Rosas, M.A.; De-Nova, J.A.; Montiel, S. Effects of Spatial Patch Characteristics and Landscape Context on Plant Phylogenetic Diversity in a Naturally Fragmented Forest. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 10, 1940082917717050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, F.A.R.; Magnago, L.F.S.; Gastauer, M.; Carreiras, J.M.; Simonelli, M.; Meira-Neto, J.A.A.; Edwards, D.P. Effects of Landscape Configuration and Composition on Phylogenetic Diversity of Trees in a Highly Fragmented Tropical Forest. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.R.; Martin, A.; Drake, F.; Martín, L.M.; Herrera, M.Á. Fragmentation of Araucaria Araucana Forests in Chile: Quantification and Correlation with Structural Variables. iForest-Biogeosci. For. 2015, 9, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangen, S.R.; Webster, C.R.; Griggs, J.A. Spatial Characteristics of the Invasion of Acer Platanoides on a Temperate Forested Island. Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzeilles, R.; Curran, M. Which Landscape Size Best Predicts the Influence of Forest Cover on Restoration Success? A Global Meta-Analysis on the Scale of Effect. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintle, B.A.; Kujala, H.; Whitehead, A.; Cameron, A.; Veloz, S.; Kukkala, A.; Moilanen, A.; Gordon, A.; Lentini, P.E.; Cadenhead, N.C.; et al. Global Synthesis of Conservation Studies Reveals the Importance of Small Habitat Patches for Biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat Fragmentation and Its Lasting Impact on Earth’s Ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petitpas, R.; Ibarra, J.T.; Miranda, M.; Bonacic, C. Spatial Patterns over a 24-Year Period Show an Increase in Native Vegetation Cover and Decreased Fragmentation in Andean Temperate Landscapes, Chile. Cienc. Investig. Agrar. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Agric. 2016, 43, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochungo, P.; Veldtman, R.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Muli, E.; Ng’ang’a, J.; Tonnang, H.E.; Landmann, T. Fragmented Landscapes Affect Honey Bee Colony Strength at Diverse Spatial Scales in Agroecological Landscapes in Kenya. Ecol. Appl. 2022, 32, e02483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duengkae, P.; Srikhunmuang, P.; Chaiyes, A.; Suksavate, W.; Pongpattananurak, N.; Wacharapluesadee, S.; Hemachudha, T. Patch Metrics of Roosting Site Selection by Lyle’s Flying Fox (Pteropus lylei Andersen, 1908) in a Human-Dominated Landscape in Thailand. Folia Oecol. 2019, 46, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Song, K.; Chon, J. Key Coastal Landscape Patterns for Reducing Flood Vulnerability. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 759, 143454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Araújo, E.; Barros, Q.; Fernandes, M.; Moura, M.; Moreira, T.; Barbosa, K.; Silva, E.; Silva, J.; Santos, J.; et al. Fuzzy Concept Applied in Determining Potential Forest Fragments for Deployment of a Network of Ecological Corridors in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gao, W.; Tueller, P.T. Effects of Changing Spatial Scale on the Results of Statistical Analysis with Landscape Data: A Case Study. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1997, 3, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N.E.; Wiens, J.A. A Novel Use of the Lacunarity Index to Discern Landscape Function. Landsc. Ecol. 2000, 15, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, J.A. Landscape Division, Splitting Index, and Effective Mesh Size: New Measures of Landscape Fragmentation. Landsc. Ecol. 2000, 15, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischendorf, L.; Fahrig, L. How Should We Measure Landscape Connectivity? Landsc. Ecol. 2000, 15, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdam, P.; Verboom, J.; Pouwels, R. Landscape Cohesion: An Index for the Conservation Potential of Landscapes for Biodiversity. Landsc. Ecol. 2003, 18, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, G.; Sengupta, A.; Alfaisal, F.M.; Alam, S.; Alharbi, R.S.; Jeon, B.-H. Evaluating the Effects of Landscape Fragmentation on Ecosystem Services: A Three-Decade Perspective. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrup, R.; Bernier, P.Y.; Genet, H.; Lutz, D.A.; Bright, R.M. A Sensible Climate Solution for the Boreal Forest. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.J.; Warkentin, I.G. Global Estimates of Boreal Forest Carbon Stocks and Flux. Glob. Planet. Change 2015, 128, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskopf, S.R.; Isbell, F.; Arce-Plata, M.I.; Di Marco, M.; Harfoot, M.; Johnson, J.; Lerman, S.B.; Miller, B.W.; Morelli, T.L.; Mori, A.S. Biodiversity Loss Reduces Global Terrestrial Carbon Storage. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, F.; Lippe, M.; Eguiguren, P.; Günter, S. Forest Ecosystem Services at Landscape Level–Why Forest Transition Matters? For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 534, 120782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, F.; Tagesson, T.; Fang, Z.; Svenning, J.-C. Transforming Forest Management through Rewilding: Enhancing Biodiversity, Resilience, and Biosphere Sustainability under Global Change. One Earth 2025, 8, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Низoвцев, В.А.; Кoчурoв, Б.И.; Эрман, Н.М.; Мирoненкo, И.В.; Лoгунoва, Ю.В.; Кoстoвска, С.К.; Ивашкина, И.В.; Алексеева, В.О. Ландшафтнo-экoлoгические исследoвания Мoсквы для oбoснoвания территoриальнoгo планирoвания гoрoда (Landscape-Ecological Studies of Moscow for Justifying Territorial Planning of the City); Дьякoнoв, К.Н., Ed.; Прoметей (Prometey): Moscow, Russia, 2021; ISBN 978-5-907244-82-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chernenkova, T.V.; Kotlov, I.P.; Belyaeva, N.G.; Suslova, E.G.; Morozova, O.V.; Pesterova, O.; Arkhipova, M.V. Role of Silviculture in the Formation of Norway Spruce Forests along the Southern Edge of Their Range in the Central Russian Plain. Forests 2020, 11, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlov, I.P.; Chernenkova, T.V. Modeling of Forest Communities Spatial Structure at the Regional Level through Remote Sensing and Field Sampling: Constraints and Solutions. Forests 2020, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Анненская, Г.; Жучкoва, В.; Калинина, В.; Низoвцев, В.; Хрусталева, М.; Цесельчук, Ю. Ландшафты Мoскoвскoй Области и Их Сoвременнoе Сoстoяние (Landscapes of Moscow Region and Their Current State); Мамай, И., Ed.; Смoленский гoсударственный университет (Smolensk State University Press): Smolensk, Russia, 1997; ISBN 5-88984-011-8. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, H.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Lutsko, N.J.; Dufour, A.; Zeng, Z.; Jiang, X.; van Dijk, A.I.; Miralles, D.G. High-Resolution (1 Km) Köppen-Geiger Maps for 1901–2099 Based on Constrained CMIP6 Projections. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koppen, W. Klassifikation Der Klimate Nach Temperatur, Niederschlag Und Jahresablauf (Classification of Climates According to Temperature, Precipitation and Seasonal Cycle). Petermanns Geogr. Mitteilungen 1918, 64, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Penas, A.; Díaz, T. Bioclimatic & Biogeographic Maps of Europe (Mapas Bioclimáticos y Biogeográficos de Europa); Cartographic Service University of León: León, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-Km Spatial Resolution Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnaev, S.F. Main Forest Types of Russian Plain Middle Part (Osnovnye Tipy Lesa Srednej Chasti Russkoj Ravniny); Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Петрoв, В. Нoвая Схема Геoбoтаническoгo Райoнирoвания Мoскoвскoй Области (New Scheme of Geobotanical Zoning of Moscow Region). In Вестник Мoскoвскoгo гoсударственнoгo университета, Серия 6: Биoлoгия, пoчвoведение (Bulletin of Moscow State University, Series 6: Biology, Soil Science); Moscow State University: Moscow, Russia, 1968; pp. 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Курнаев, С.Ф. Лесoрастительнoе Райoнирoвание СССР (Forest-Biogeographic Zoning of the USSR); Наука (Science Publishers, Russian Academy of Sciences): Moscow, Russia, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Грибoва, С.А.; Исаченкo, Т.И.; Лавренкo, Е.М. Растительнoсть Еврoпейскoй Части СССР (Vegetation of the European Part of the USSR); Наука, Ленинградскoе oтделение (Science Publishers, Leningrad Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences): Leningrad, Russia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Огуреева, Г.; Булдакoва, Е. Разнooбразие Лесoв Клинскo-Дмитрoвскoй Гряды в Связи с Ландшафтнoй Структурoй Территoрии (Forest Diversity of the Klinsko-Dmitrovskaya Ridge in Relation to the Landscape Structure of the Territory). Лесoведение (Lesovedenie) 2006, 1, 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chernenkova, T.V.; Morozova, O.V. Classification and Mapping of Coenotic Diversity of Forests. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2017, 10, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K.; Cushman, S.A.; Ene, E. FRAGSTATS v4: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Categorical Maps. Computer Software Program Produced by the Authors. 2023. Available online: https://fragstats.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Walz, U. Landscape Structure, Landscape Metrics and Biodiversity. Living Rev. Landsc. Res. 2011, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; He, C.; Anthony, M.A.; Schmid, B.; Gessler, A.; Yang, C.; Zhang, D.; Ni, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, J. Decoupled Responses of Plants and Soil Biota to Global Change across the World’s Land Ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhong, X.; Chen, J.; Nielsen, U.N.; Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Qu, Y.; Sui, Y.; Gao, W.; Sun, W. Ecosystem-level Decoupling in Response to Reduced Precipitation Frequency and Degradation in Steppe Grassland. Funct. Ecol. 2023, 37, 2910–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, N.G.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.; Biederman, J.A.; Breshears, D.D.; Fang, Y.; Fernandez-de-Una, L.; Graham, E.B.; Mackay, D.S.; McDonnell, J.J.; Moore, G.W. Ecohydrological Decoupling under Changing Disturbances and Climate. One Earth 2023, 6, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polazzo, F.; Rico, A. Effects of Multiple Stressors on the Dimensionality of Ecological Stability. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 1594–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, L.J.; Newbold, T.; Purves, D.W.; Tittensor, D.P.; Harfoot, M.B. Synergistic Impacts of Habitat Loss and Fragmentation on Model Ecosystems. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20161027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordingley, J.E.; Newton, A.C.; Rose, R.J.; Clarke, R.T.; Bullock, J.M. Habitat Fragmentation Intensifies Trade-Offs between Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in a Heathland Ecosystem in Southern England. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, C.B.; Smemo, K.A.; Kershner, M.W.; Feinstein, L.M.; Valverde-Barrantes, O.J. Decay of Ecosystem Differences and Decoupling of Tree Community–Soil Environment Relationships at Ecotones. Ecol. Monogr. 2013, 83, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulne, J.; Garneau, M.; Magnan, G.; Boucher, É. Peat Deposits Store More Carbon than Trees in Forested Peatlands of the Boreal Biome. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, B. How Do Boreal Forest Soils Store Carbon? BioEssays 2021, 43, 2100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Zhuang, Q. Quantifying the Role of Moss in Terrestrial Ecosystem Carbon Dynamics in Northern High Latitudes. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 6245–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turetsky, M.R.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Euskirchen, E.; Talbot, J.; Frolking, S.; McGuire, A.D.; Tuittila, E.-S. The Resilience and Functional Role of Moss in Boreal and Arctic Ecosystems. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanatta, F.; Engler, R.; Collart, F.; Broennimann, O.; Mateo, R.G.; Papp, B.; Muñoz, J.; Baurain, D.; Guisan, A.; Vanderpoorten, A. Bryophytes are Predicted to Lag behind Future Climate Change despite Their High Dispersal Capacities. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-Souza, T.; Chase, J.M.; Haddad, N.M.; Vancine, M.H.; Didham, R.K.; Melo, F.L.P.; Aizen, M.A.; Bernard, E.; Chiarello, A.G.; Faria, D.; et al. Species Turnover does not Rescue Biodiversity in Fragmented Landscapes. Nature 2025, 640, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, J.; Wu, W.; Liu, J. Global Forest Fragmentation Change from 2000 to 2020. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allouche, O.; Kalyuzhny, M.; Moreno-Rueda, G.; Pizarro, M.; Kadmon, R. Area–Heterogeneity Tradeoff and the Diversity of Ecological Communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17495–17500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marsland, R., III; Cui, W.; Mehta, P. The Minimum Environmental Perturbation Principle: A New Perspective on Niche Theory. Am. Nat. 2020, 196, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, R.; Bueno, A.d.A.; Gardner, T.A.; Prado, P.I.; Metzger, J.P. Beyond the Fragmentation Threshold Hypothesis: Regime Shifts in Biodiversity across Fragmented Landscapes. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetcuti, J.; Kunin, W.E.; Bullock, J.M. Habitat Fragmentation Increases Overall Richness, but Not of Habitat-Dependent Species. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 607619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Gauthier, O. Statistical Methods for Temporal and Space–Time Analysis of Community Composition Data. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20132728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierus, B.; Du, T.; Maduforo, A.N.; Gilbert, B.; Koh, K. Prevalence and Quality of Mixed Methods Research in Educational Subdisciplines: A Systematic Review. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 21582440251335171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).